Latter-Day Bergman: Autumn Sonata as Paradigm

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Ingmar Bergman began his film career with a paranoid invention salvaged by Alf Sjöberg, who, from the sketch submitted by Bergman, put the Swedish cinema on the map in 1944 with the film known in the United States as Torment. The germ of this movie was Bergman's fear that he would be flunked on his university entrance examination; his revenge in advance was his creation of a tyrannical schoolmaster whom he aptly named Caligula. (Sjöberg added a political implication by having the actor made up to resemble Himmler, chief of the Reichsführer SS.) Over the years, Bergman's compulsion to nourish every slight, every adverse criticism, grew into his now familiar, never subdued war against Father, who once punished him by locking him into a closet. We are at liberty to wonder if this ever happened and simply to credit Bergman with singular tenacity for inventing an image that gratified him, and for extrapolating from it one of his twin obsessions (the other being the fatality of the couple): the despotism of the Father and hence the fallibility of God. (If there has always been something shopworn about Bergman's conception, it's because Dostoyevsky got there first, with the most.)

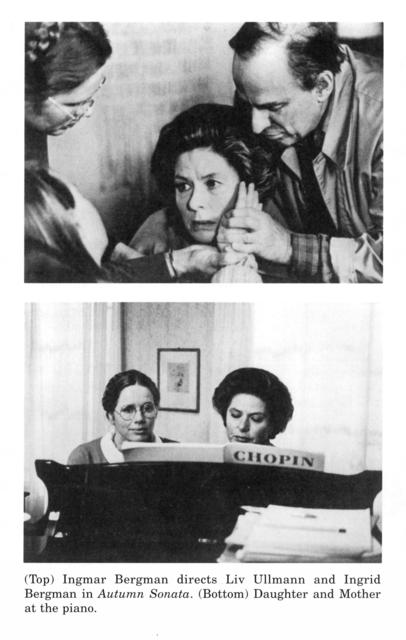

Thus Autumn Sonata (1978) is characterized by the same kind of ambivalence that undermined the artistic veracity of Wild Strawberries in 1957. In the earlier film, Bergman's portrait of an old professor, whose egoistic frigidity lost him an idyllic sweetheart and produced an impotent son, was at odds with the visibly sympathetic performance of Victor Sjöström. Just as Bergman was reluctant in Wild Strawberries to follow the implications of his own scenario by destroying the professor-figure entirely, so in Autumn Sonata he sets up Ingrid Bergman (in her final theatrical film) as a concert pianist-mother who is supposed to have crippled her two daughters (one child being insufficient for the force of his accusation); then the auteur becomes so enamored of the personality he has given his character that he is hard put to convince us she could possibly be either as indifferent or as ruthless as her articulate daughter maintains.

To synopsize this picture accurately for anyone who has not seen it is almost impossible, since what takes place in Autumn Sonata beyond the severely limited action is completely a matter of individual interpretation. Every statement made by the characters is open to question, and the whole moral issue on which the film hinges is never depicted. The damaging relationship of which this mother-daughter confrontation is supposed to be the climax is not visualized in flashbacks, so that the viewer can judge for himself; it is, rather, wholly summarized in verbal terms through the daughter Eva's accusatory retrospect.

At the beginning, reading her diary while she awaits the visit of her celebrated mother, Liv Ullmann as Eva seems pretty clearly, in her spinsterish appearance and manner, to be a manic-depressive type, melancholy and retentive but prone to fitfulness as well. We glimpse her husband hovering in the background, from which he scarcely emerges during the subsequent encounter; and we learn that since her son, aged fourteen, drowned some years ago, Eva has kept his room as it was when he died and moons over photographs of him. This morbid devotion to the irretrievable contradicts the leading statement she reads from her diary: "One must learn how to live. I work at it every day." We further discover that, before her marriage, Eva had lived with a doctor, and that she had once had tuberculosis. Not until later in the film do we become aware that she is looking after her bedridden sister, who suffers from a degenerative disease that has affected her speech and movement, and whom her mother believes to be in a nursing home.

When mother arrives at this outpost of Ibsenism (Bergman's setting, during this period of his self-exile from Sweden, is among the Norwegian fjords), it is not too surprising that, after the first affectionate exchanges are over, as Eva listens obediently to her parent's necessarily self-absorbed chatter (she has come, after all, from the world of professional music as practiced in European capitals), the daughter all the while regards the mother with mingled amusement and suspicion. In no time at all, suspicion has become hostility; and step by step Eva rebukes her mother's self-secured authority in a crescendo of bitter reproaches that mounts steadily into the realm of hysteria. The younger woman makes the distressed elder responsible for all the ills of her life and blames her, besides, for the condition of the drooling sister upstairs, whose presence in the house is an unwelcome shock to the fastidious visitor.

Following a long sequence of passionate denunciation by her daughter, which she stems only at momentary intervals, the mother, inwardly shaken but outwardly collected, leaves to fulfill another musical engagement. Then after a few solicitous suggestions from her husband—who, again, has passively remained on the sidelines of this internecine struggle being waged under his roof—Eva writes a letter to the departed woman in which she retracts the burden of the accusation she had hurled and makes a pathetic bid for love. This letter is in part read over the image of the mother, traveling south for her next concert.

Critics have generally received this film as if it were indeed a straightforward indictment by the neglected daughter of a selfish parent, which means that they accept at face value the allegations of the girl and pay no attention either to the personality or the remonstrance of the mother. In fact we have only the daughter's word that her mother's inattention drove her into a messy relationship with that "doctor" who is briefly mentioned. What part any of this played in her contracting of tuberculosis is never clarified. How satisfactory or unsatisfactory her present marriage is, one is left to infer. Whether her mother had an affair with someone named Marten without telling her husband, Josef, depends on which of the two women you believe, and what bearing this has on anything else is never made clear. One is also left to decide whether or not the mother's absence at a crucial hour was the impelling cause of the sister's disabling condition.

It is possible to take the other view, that Bergman intended the Liv Ullmann character to reveal herself unmistakably as a self-pitying neurotic, whose charges are patently cancelled by the clearly delineated superiority of the mother. (One of the most telling moments in the film would then be Ingrid Bergman's correction, at the piano, of her daughter's playing of a Chopin sonata: if the girl is to give the piece an authentic interpretation, declares the mother, she must avoid sentimentality and understand that the music should express "pain,not reverie.") However, even this view of Bergman's strategy may be ingenuous; it is much more in his line to establish an impeccably distinguished persona, poised against an unattractive spinster who is nonetheless married, in order to make the latter's accusations appear at first unlikely, then the more convincing, precisely because the accused has the more sovereign air. (This mechanism was invented by Strindberg in his play The Stronger from 1889.)

In truth, near the end of Autumn Sonata, Bergman loses confidence in his own gambit. He cuts, in the most excruciatingly obvious way, from the sick daughter writhing helplessly on the floor, to the entrained mother coolly informing her agent that her visit home had been "most unpleasant": in other words, she shrugs it off. Unless we are to suppose she is acting, this is outrageously unbelievable; it totally contradicts the character of the woman we have witnessed, in merciless close-up, for the preceding hour. Evasive or hesitant she may have been when justifying a given response or action recounted by the vindictive Eva, but never for a moment did one feel that she was radically false. Equally unacceptable, as the film ends, is the abrupt change of heart that dictates Eva's remorse for the vehemence with which she has been arraigning her mother—thereby cancelling, at the last minute, the substance of the movie's unrelenting inquisition.

There is small point in trying to weigh truth in the antithesis Bergman has contrived for Autumn Sonata. At any latter-day movie of his, including the slightly earlier Serpent's Egg (1977) and the subsequent, appositely titled From the Life of the Marionettes (1980), one cannot be sure whether this director-screenwriter is unaware of the dramatic incongruities that he creates through poor motivation or whether he doesn't really care. He seems indifferent to plot because a plot is an action consistent with the revealed nature of its characters, and Bergman seems unable to perceive consistency; his characters say what he wants them to say, to an end he alone has chosen, as opposed to what they would say if allowed to speak for themselves.

He used to be a master of comedy, as in his gloss on Renoir's Rules of the Game (1939), Smiles of a Summer Night (1955), for in secular, and even more so divine, comedy you can give full rein to the improbable. You can also do so in a religious allegory like Bergman's Seventh Seal (1957), if not in existential meditations of the kind exemplified by his "faith" trilogy of Through a Glass Darkly (1961), Winter Light (1962), and The Silence (1963), which, along with the earlier Naked Night (1953) and The Magician (1958) and the subsequent Persona (1966), justly secured the reputation of Ingmar Bergman in America. Even he seems to agree, however, that the enigmas of Autumn Sonata represent a parody of his earlier, better work: "Has Bergman begun to make Bergman films? I find that, yes, my Autumn Sonata is an annoying example . . . of creative exhaustion" (Images: My Life in Film, 1990).

It may be worth remarking here that while Autumn Sonata postulates the destructive consequences of perfectionism in life as in art, Bergman the recreant preacher has, in his own way, been aesthetically and obsessively pursuing the absolute or the ideal: by not so coincidentally choosing a central character with the primal name of Eva; and, most importantly, by creating immaculate cinematic compositions that achieve their immaculateness at the expense of worldly or natural conception. (Almost all of this film was shot inside a studio.) With this in mind, we should not expect the mundane inventions of Autumn Sonata to have objective credibility; the characters' motives are flimsily explored, the actualities of their lives not dramatized but reported after the fact. If Eva knew so much about her mother's devices of evasion, for example, as well as about her own victimization at her parent's hands, she would long since have ceased to be a victim—or at the very least she would have remedied those absurd outer signs of her condition thrust upon her by Bergman via his wardrobe department: I mean the old-maid's provincial hair bun and the disfiguring eyeglasses. Women's faces, preferably under stress, are what Ingmar Bergman likes to photograph; objective coherence he no longer cares to cultivate. Like many other films in his canon, Autumn Sonata is a private tribunal. Bergman himself is the confessor, prosecutor, plaintiff, and as neutral or uncommitted a judge as he can risk being.

Critics in America consistently underrate this Swedish inability of Bergman's to commit himself to the terms of a moral choice he has ostensibly initiated—unless, that is, he knows for certain he has a target to which absolutely no one will object. The sympathetic link between this Swede and Americans is the fundamental puritanism we culturally share; Bergman's Nordic damnations, like Strindberg's, are taken far less seriously, for example, by the Italians, the French, or even the English. Strindberg himself was the artistic stepfather of Eugene O'Neill, who successfully transplanted the Swedish dramatist's suffocating (Lutheran) ethos into Irish-American (Catholic) settings, and who, for his part, like the Bergman of Smiles of a Summer Night, managed to write only one comedy (Ah, Wilderness! [1932]) among his many works for the theatre. The Swedes flattered O'Neill and his solemn sensibility back by staging all his plays at Stockholm's Dramaten in addition to awarding him the Nobel Prize in 1932 (before he had written his great naturalistic dramas, I might add). Strindberg is also the single most influential figure behind all Bergman's work—he is perhaps the only authentic father to whose authority Bergman has consented—although the filmmaker seems to substitute excessive love for women for the dramatist's extreme antipathy toward them.

Indeed, the "rehearsal" in After the Rehearsal (1984) is of one of Strindberg's plays (A Dream Play, 1902), a number of which Bergman himself has directed for the theater. And Autumn Sonata may derive its inspiration from that mad master's chamber drama-cum-dream play titled The Ghost Sonata (1907), not least because Bergman says he initially conceived his film like a dream in three acts, with "no cumbersome sets, two faces, and three kinds of lighting: one evening light, one night light, and one morning light" (Images). For all its avant-garde theatrical devices, this early twentieth-century dramatic work is not unrelated in theme to its Bergmanian namesake, for Strindberg attempts in his autumnal Ghost Sonata to penetrate the naturally deceptive or mediating façade of verbal language, as well as of bourgeois exteriors—not only through the visual eloquence of scenic design, but also through the abstract purity of musical form.

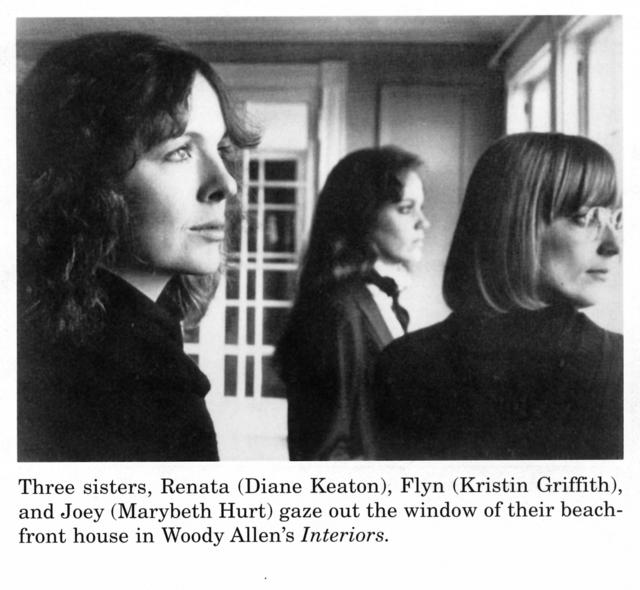

Moreover, Strindberg composed The Ghost Sonata not long after the five psychotic episodes of his "inferno crisis," even as Bergman wrote Autumn Sonata immediately upon recovering from a nervous breakdown that resulted from his arrest in Sweden on charges of tax evasion. A major difference between these two artists, however, is that Strindberg's psychiatric crisis restored his religious faith, and that faith gave much of his post-inferno work a mystical cast in which benevolent or judicious transcendental powers were operative—expressing themselves even during the most everyday of occurrences. Bergman's breakdown, by contrast, had no such effect either on the director or his films, which from The Seventh Seal to The Virgin Spring (1960) to The Silence had already led progressively not only to the rejection of all religious belief, but also to the conviction that human life is haunted by a virulent, active evil. It has been said that the smothering family atmosphere, if not the religious pall, in certain Bergman films, even as in Strindberg's naturalistic The Father (1887) and O'Neill's Long Day's Journeyinto Night (1941), appealed to our own Woody Allen by reason of his special Jewish vulnerability to comparably oppressive parents in his Brooklyn environment. I would not wish to pronounce on this probability, if probability it is, but I suspect that the driving force behind Allen's oft-expressed Bergman-worship is rather an aspiring intellectual's love of conceptual perfection and a confusion of it with the less-is-more aesthetic of Scandinavian reductionism, together with the snobbish misgiving that comedy is an inferior art and an obsessive love for women that Allen seems to confuse with a desperate need to validate his narcissistic love for himself. In any event, if without knowing anything whatsoever about the work of either director, one had seen Bergman's Autumn Sonata right after Allen's Interiors (1978), one might easily have concluded that the Swedish filmmaker had attempted to imitate the American.

As for the Bergmanian cultural puritanism or hunger for the High Serious that O'Neill shares in such plays as Desire Under the Elms (1924), Strange Interlude (1928), Long Day's Journey into Night, and A Moon for the Misbegotten (1943), and of which Allen unsuccessfully attempts to partake in films like September (1987), Another Woman (1988), and Alice (1990) in addition to Interiors, such aspirations toward spiritual austerity and moral rigor are not particularly evident in American cinema. (One possible exception that comes to mind is Five Easy Pieces [1970], but even this work—about a promising pianist who turns his back on classical music and the concert/recording world—has more in common with the movies I'm about to name than with Autumn Sonata.) In American movies, more than in our other arts, popular entertainment is the major enterprise, and it is rarely austere, seldom rigorous, and insufficiently moral—except, that is, insofar as it is at the same time sentimental.

But the truth be known, it takes more independent imagination, greater cinematic scope, and a richer sense of life's poetry to make "popular entertainment" like Bonnie and Clyde (1967), Mean Streets (1973), Badlands (1973), Midnight Cowboy (1969), The Wild Bunch (1969), Chinatown (1974), Raging Bull (1980), Tender Mercies (1983), or House of Games (1987), than it does to make Interiors, or even Allen's oft-noted attempts at striking a balance between the solemn and the funny such as Annie Hall (1977), Manhattan (1979), Hannah and Her Sisters (1986), and especially Crimes and Misdemeanors (1989). The aforementioned variations on the boxing, gangster, western, and detective genres may not be shot through with the subtle values of living to be found in European films—the wisdom, refinement, and tendresse at which Autumn Sonata doubtless aims—but they are nonetheless vital in their consideration of the harsh characteristics of so much of American life: baseness, greed, callowness, and brutal ambition if not brutality itself. We may have our puritanical strain, then, but, where movies are concerned, apparently we prefer to indulge it through the avenue of European cinema—in other words, by going back to its source.