An American Seduction: Portrait of a Prison Town

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Two more walk in. I should feel safe, but I don't. These uniforms are about keeping people in line. It feels more like a Central American border crossing than a gas station convenience store in rural America. The young man with the ponytail apparently doesn't like the scene either; he walks in, then pivots coolly right back out.

Later, I learn this is shift change for Susanville's two prisons, when hundreds of correctional officers (COs) switch places and traffic triples in this town, population 7800. With 10,000 inmates already, a federal prison on the way, and talk of a women's prison and a sex offender jail still to come, this is Prison County USA, where everyone and his brother works in some way for the prison, where there are more people behind bars than outside of them.

Now, when I hear of other small towns campaigning for the panacea of a prison, I want to say, listen to this story first. I think: let me tell you about Susanville.

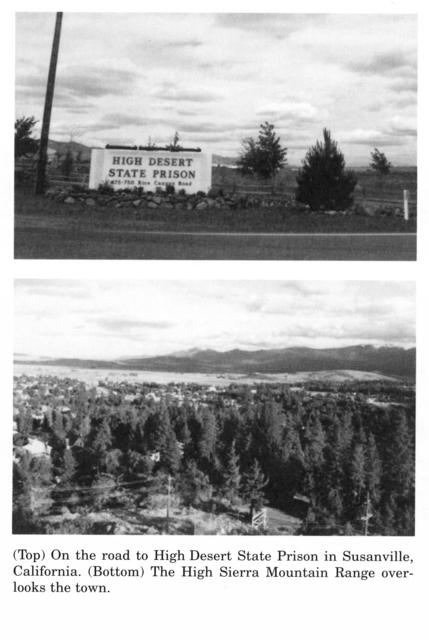

People told me the prison came to town just in time. The closing of two mines and an army depot, the shrinking logging industry, and a general feeling that the town was collapsing in on itself—all led Susanville to open its arms for High Desert State Prison, a 4500-inmate maximum security facility to be built just eight miles from Main Street, where it would sit beside the California Correctional Center (CCC), a smaller prison built in 1963. With the new high-tech prison and plans for more, Susanville could one day quite possibly contain the largest penitentiary complex on the planet.

But such notoriety didn't concern the townspeople in 1992, when 57 percent of the voters said yes to the ballot proposal for another prison, mainly due to the public relations campaigns of the Chamber of Commerce and the Save Our Jobs Committee. A few months later, like a family preparing for the arrival of an important guest, the town readied itself for the prison.

And appropriately, this guest would bring gifts: a $57-70 million payroll, 1200 new jobs, and anywhere from 3500 to 4000 new residents: the families of inmates and prison personnel who would buy their groceries, their gas, their meals, who would pay their rent and mortgages in this town. Annexing the prison into the city limits would mean more grant dollars for the city as the population total, now including inmates, more than doubled to 16,000. The state Department of Corrections, eager to build another prison to stem the flow of a system already operating at 201 percent capacity, offered $2 million to compensate for impacts on schools, courts, and roads. It was the largest sum ever given to a community in which a prison was constructed, although it would be argued later that it was not nearly enough.

The people spread a banner across Main Street (WELCOME PRISON EMPLOYEES AND INMATES), builders drew up plans for new condominiums and homes, motels advertised special rates for prison employees and inmate families. Sierra Video offered coupons for one free rental with a prison employee ID card. Uptown Uniforms displayed khaki jumpers and shiny black boots in its windows—a smart move considering $200,000 would be spent annually on uniforms. People lined up at the karate school for self-defense classes. Susanville Supermarket hired four new people and structured work schedules around the state's first of the month paydays. Carpet cleaners, hired out by real estate firms and landlords of rental property, were swamped.

News of the prison found its way to companies like Wal-Mart, Taco Bell, Country Kitchen, Blockbuster Video, all of whom came and set up shop in advance. During prison construction in 1995, every motel in town put up "no vacancy" signs as new prison employees and construction workers camped in trailers and filled parking lots for weeks.

Four years later, after the strip lengthened and the stoplights multiplied and many small businesses, unable to compete with Wal-Mart, quietly boarded their doors, Susanville is reminiscent of so many towns that have outgrown themselves and lost something in the process. But it is also unlike many small towns—there is the overwhelming presence of men with military haircuts and trim mustaches, the constant talk of prison scandals and violence (eleven inmates have been killed or committed suicide since High Desert's opening), the clear division between locals and prison employees and inmate families. People complain about anonymity, about long lines at the bank, about traffic, about the rise in prices. The police department faces rising domestic violence, a 50 percent jump in juvenile delinquency and trade in hardcore drugs like heroin from gang members associated with the prison. The real estate community holds a glut of property because the new prison employees are a transient lot, eager for promotion and transfer, and they're not settling in like they were supposed to.

It would be easy to apply literary allusions to this collision of frustrated expectations—the prison was a Trojan horse, a Faustian bargain, a Pyrrhic victory, but that would deny the fact that some of the promises have come true, to a certain extent. The town does have more money, and graduating seniors, with job opportunities at the new prison, no longer have to flee to Portland and Sacramento and other faraway cities. People can make fewer shopping trips to Reno and choose from six movies instead of two. There's a health food store, and at Safeway people can buy goat cheese and focaccia bread. As one woman said, "Who knows, maybe we'll get a Mervyn's."

In a place where the economy is dying and the young people are leaving for places where it is not, the new prison was about money, about security and progress and hope for a better life. But as Susanville has discovered, a new prison requires that the community adapt to a rapid leap in a specific kind of population—those drawn to and associated with the work of corrections, an industry for whom the raw material is the systematic incapacitation of hostile, despairing human beings, in this case over 10,000 of them.

In the end, this is a town in which everyone was seduced in one way or another, and because a seduction is ultimately a mutual act, there was no one to blame the morning after. In this town everyone held out for a promise that, when kept, turned out to be less—or more—than bargained for.

Bruce Springsteen never lived in Susanville, but if he had, he would have written a song about it, about the mills that closed, and the mines, the army depot, about how everything the town relied on had slipped away like a woman who'd seen something better on the other side of the road.

But damn, if the place had nothing else, it sure claimed gorgeous country—the high desert of northeast California, on the edge of the state that overlooks the arid sands of Nevada. Through this land of sage and scrub brush to the east and dense forests to the west, the Diamond Mountains rise unevenly above the town and beyond until they join the Sierras ninety miles to the south, where the water of Lake Tahoe pools clear and still.

And the place had good people to work the land. For a century and a half folks have been coming to this town looking for gold or some form of it in timber or ranching, full of hope and grit and then the scratch to survive when the dream is gone, a search so definitively American that I began to see that Susanville was not just a small town but The American Small Town, and that it, like the Washo and Maidu Indians who lived here in the beginning, like the wolves who wandered this basin, is an endangered species.

As the biggest town in Lassen County, Susanville sits in the middle of prime ranching country, about 100 miles from any good-sized city—Reno, Chico, Redding, and Red Bluff. Heading south toward Reno, drivers are treated to a comforting view of cattle scattered over ranchlands with high hills beyond like the warm backs of sleeping dogs. Here 4H is as important as church, and the Lassen County Cattlewomen hold an annual Mother's Day Beef Recipe Contest. Poems about beef are published in the local, weekly paper, Lassen Times ("Yum Beef Yum! / Put it in the crock pot, place it on the grill / Invite some friends, give them a tasty thrill!"). Youth compete in rodeos, experts in barrel racing, goat tying, and break away roping.

For these reasons it's often called cowboy country (or "redneck country" by the less generous). The weather is harsh—with its 4500-foot elevation, in the summer it tops 105 degrees and in the winter, snow can bury the town for weeks. It's a man's town, where fishing and hunting are part of every good boy's education, where the local community college offers more classes in auto mechanics and welding than English or History. A place where gunsmiths and well drillers receive the kind of recognition reserved for professors and doctors in other parts of the country; where gun racks are as ubiquitous as cowboy hats and at the gas station convenience store on Highway 395 you can buy bullet key chains. The women, too, are tough, as adept at changing car parts or chopping wood or rolling a cigarette as the men; this is not a delicate place, and they grow old fast in the dry desert air, their faces lined and set.

But with the toughness of these people comes a respect for life and an enormous capacity for love. Ten years ago, lured by the gorgeous country and the promise of a small town life, my mother fled the Bay Area with my little brother and bought twenty-two acres of land covered with waist-high rye and the tracks of mule deer, coyotes, and jackrabbits. Over those years I've spent summers and holidays here; I've tutored at the vocational ed. office and taught at the community college. I've made good friends and loved men and helped nurse my stepfather through a summer of chemotherapy.

In this way I've come to know and admire the people of the town, but it is also as an observer and visitor that I have seen the changes. When I walk down Main Street, I am simply another stranger, now. And I began to ask questions because in the space of several years I have seen Susanville change into another kind of place, and the change is one that is neither altogether good nor altogether inevitable. These changes seem important, and though they are cropping up all over the country, no one is talking about prison towns.

On my mother's dining room table lies a polished cedar bowl, so smooth it seems lit from within, the kind of glow that requires an attention both precise and time-consuming. On the bottom of the bowl a typewritten note with a prison ID number is glued in place: For Victims of Crime. She bought it from the annual Prison Craft Fair, a charity event benefiting the Lassen Family Services Domestic Abuse Program, where you can buy everything from an oak coffee table to an embroidered leather belt.

"That place sells out in an hour," she tells me. "The craftsmanship is amazing."

The inmates aren't there, of course, just their handiwork. For many of the townspeople, the fair is the closest they will get to the prison or its occupants. It is an example of the ways in which a town will ultimately co-exist with a prison, in partnerships that range from fundraisers to community work, where inmates groom baseball diamonds, plant trees on county property, paint governmental buildings—even dry-clean school band uniforms. As the California Department of Corrections boasts in a brochure, "While the inmates are paid only cents per hour, the benefit to the community is far greater."

Those benefits are the icing on the economic cake that is offered to isolated communities like Susanville, far from any major port or city, who often try in vain to attract new industry. The town then relies on logging, mining, ranching—and government. Here, with more than half the town working for a government agency, acronyms spill out easily from daily conversations: BLM (Bureau of Land Management), CDF (California Department of Forestry), USFS (United States Forestry Service), DFG (Department of Fish and Game) and of course, CDC (California Department of Corrections).

In 1963, the first prison, the 1,120-acre California Correction Center ("The Center"), was built to further conservation efforts. Inmates lived at the boarding-school-style center, spending their time helping to reduce fire hazard, managing forests and watersheds, clearing streams, and improving fish and game habitat. In the cyclical nature of prison policy, this was the rehabilitation era, the time of liberal reform. One local man told me it wasn't unusual to get a work crew of inmates to come out to help on someone's ranch. The Center, which began with only 1,200 inmates, more than doubled in 1987 to accommodate the more than 2,000 rapists, kidnappers, and other violent offenders, who would be held behind razor wire in two-man cells with rifles trained on them twenty-four hours a day. It was a sign of the times—the "tough on crime" policies. Despite misgivings—there was no vote and hardly a public forum—the town adjusted to the expansion; after all, Susanville relied on CCC for 20 percent of its economy.

Over the past ten years, as logging shrank and the mines and army depot downsized and then eventually closed, the idea of another prison seemed quite logical. After all, the state already owned the land, and it needed another prison to help with the dangerously overcrowded system. Even with High Desert, in mid-1998 the state's thirty-three facilities weren't enough to contain the state's criminals, whose number rises about seven percent annually, the highest rate in the nation. (The state's punitive trends, the legacy of two tough-on-crime governors, included 1994's "three strikes" legislation which sentenced three-time losers to twenty-five years to life, doubled terms for many second-time felons and slashed time off for good behavior. The CDC's master plan predicts that inmate population will exceed maximum operating prison capacity of 200,000 by the year 2001—sites are under discussion or planned for California City, Delano, Sacramento, San Diego County, and Taft.) But if CCC was a trickle that became a stream in Susanville, the $272 million High Desert State Prison was a river that became a flood.

Part of the problem was the state's bait-and-switch halfway through the process. Four months after voters approved a low to medium security facility, High Desert became a Level III and IV facility, housing the most violent offenders and those with twenty-five-year to life terms. This required more staff, high security lights and other requirements. The implications of this newer security level were far-reaching but hard to nail down. It meant, for example, that more inmate families would move to Susanville to be near the incarcerated family member, stressing the social services more than anticipated.

County officials were furious, but there was little they could do. The state's mitigation money helped, and the city receives about fifty dollars a year for each inmate, but it doesn't help enough with the cost of building roads, increasing law enforcement, and expanding schools for an estimated 1,180 additional schoolchildren. The ranchers were against the prison from the start, claiming it exchanged open space and crop land for housing and infrastructure, and would siphon ground water now used for growing crops.

Perhaps the biggest problem with the prison is that unlike private industry, which generates as much as $600 per job in property taxes, a government industry produces no direct county taxes, the money counties need to supply health care and police protection. And about half of Lassen County's existing industry is local, state, or federal government already.

When word of the new prison got out, former warden Bill Merkle saw 500 transfer requests for Susanville. "Lassen County is a good place to raise kids, has clean air and a nice environment," he said, a quote that began to take on a kind of mantra-like status, as every correctional officer I talked to repeated it in turn. In all, nearly 1800 correctional officers (COs), some veterans but most new on the job, made their way to Susanville from Southern California and the nearby larger cities of Sacramento, Reno, and Vacaville, a good number bringing families with them. For many of these men and their families, they might as well have crossed the border into another country.

Carol Jeldness, a licensed clinical social worker who contracted with the prison to provide counseling under the prison's Employee Assistance Plan, built her practice on CO relocation trauma. "A town like this, it doesn't welcome you much," she says.

The new COs needed not only to adjust to working in a brand new maximum security prison—with all of its start-up problems—but they had wives and children who'd come to a place with little to do, or at least it seemed so to many of them. There is no indoor mall in Susanville, no factory outlet stores, no roller rink, no Boys & Girls Club—to find any of these requires a 160-mile round trip. The weather only exacerbates the isolation. It doesn't snow much in Orange or Sacramento counties, but in Susanville, for a good part of the winter people need chains to get down Main Street. Cabin fever quickly became a popular topic. The new residents left often for Reno, for relief. Other prison towns, like the city of Corcoran in central California, see something similar.

"We were told a lot of guards were going to be living in town, that the tule fog was going to be the big thing to keep them living here, that no one was going to want to commute," says Police Corporal Victor Castillo, 34, a lifelong Corcoran resident.

Instead, guards and much of the staff "just blow through town. I don't think more than a handful of them actually live here."

Compounding the adjustment problem was the financial one. To be a correctional officer, all you need is an AA degree and successful completion of a six-week training course—until recently it was only a high school diploma. As a result, many of the COs at High Desert are, say, 22-30 years old, making $40,000 a year with overtime. A stroll down "CO Row," the neighborhoods of Howard Court, South Mesa, and Fairfield Streets, offers a pretty good look at the lifestyle these new officers thought they could afford: fishing boats, ski jets, new American trucks and sport utility vehicles all sitting in front of brand-new ranch style houses with two-car garages and manicured lawns.

The irony is that many of the younger COs are filing for bankruptcy, and those that aren't are struggling to make minimum payments on purchases that were bought too fast and in too many numbers. Even the Iron Horse Gym—a favorite of COs for its ample free weights—has many delinquent CO accounts; the monthly payment is about thirty dollars.

"It's a mess, and it spills over onto the family," Jeldness says. "They start pulling double shifts, working sixty, seventy hours a week out there. Even those without financial problems have to pull the bad shifts in order to get seniority."

To make matters worse, California leads the nation in inmate shooting deaths (twelve from 1994-1999, compared with six state prisoners shot across the entire nation during the same time period); High Desert accounts for three of those deaths over the past three years. Many of California's prisons, including High Desert, have recently been accused of scandalous activity on the part of the COs, everything from drug trafficking and torture (such as forcing inmates to play "barefoot handball" on scorching asphalt) to pitting inmates against one another like roosters in a cockfight, complete with spectators and wagering—and then shooting those who won't stop fighting. Two High Desert COs were charged early this year with filing a false crime report. Many of the COs I talked to were scornful of these activities, and some denied the existence of inmate abuse, claiming that the shooting of an inmate is an easy thing to twist in the media.

Regardless, the current spotlight on COs has made work even more difficult: for most of their waking hours, these men (and a few women) are immersed in one of the most oppressive, stressful environments imaginable. As one shopowner commented about High Desert, "That place rock 'n' rolls."

"What kind of husband and father do you think they can be after what they've been around for fourteen hours?" asks Jeldness. "The issues are complicated, but all seem to stem from men not talking."

"The CO would say to me, 'my wife expects me to leave it at the door and be compassionate. It doesn't work like that.' It was awful," she says. "I had no authority to require time off. And the COs were always averse to that anyway. They're pressured to hide the counseling. It's all about being strong. And Lord, there's a lot of alcoholism. Many of my clients came home to a cleaned out house—the wife just couldn't take it."

Jerry Sandahl, a CO at High Desert with fourteen years of experience, says it took him years to adjust.

"I spent eight to sixteen hours a day in solid bullshit," he says, looking out the window as a logging truck passes by. On the street, I would have guessed him for a salesman, an accountant maybe. "You hear cursing all day, and you come home and that's all you think about. It did tragedy on my family. When you come in there, they tell you family values are the most important thing, but it's not true. The state was. We're like a store, a warehouse. You bring in the merchandise—when someone wants to parole it, we send it back out."

Sandahl chuckles as he talks about the new guys, whom he calls "hyper."

"I drive out toward the prison and fifteen cars pass me, all new staff. I think, God's country will prevail. I keep telling them—look at the alfalfa growing in the fields. This thing will be here tomorrow. The problem is that they think they're cops twenty-four hours a day. I tell you what: if he doesn't have over eight years, the guy don't know anything. He's still in his mind glory days."

Jeldness, who is also a mediator for Lassen County Family Court, saw her caseload, mainly child custody and divorce, jump from 167 to 320 in one year. During the two years after the prison opened, domestic violence as well skyrocketed in Susanville. Linda McAndrews, head of Lassen Family Services, says she got 3000 crisis calls from women in 1996. She went to the warden and told him "he had to do something." He did—the number of crisis calls has decreased during the past year—but many believe that's due to the new law that states if you've been convicted of domestic abuse, you're not allowed to carry a gun. If you can't carry a gun, you won't go far in the prison system. Consequently, women are much more reluctant to report abuse, fearing their husbands will lose their jobs, and then whatever problems they're facing will only spiral into something worse.

I think about these interviews as I walk down Mesa Street, along the homes of the new CO families. I am struck by the emptiness—no children on bikes, no dads tinkering in the garage; it is as if the sterility of the newness has not worn off, and isn't about to any time soon.

Susanville, like most small towns, rests many of its hopes on its children, and so the jump in juvenile problems seems especially poignant. One afternoon I meet with Jason Jones, a juvenile probation officer, at Denny's, one of the most popular restaurants in town. While I wait for him, it strikes me that many of the men in the restaurant, in particular the young ranchers and truckers, look not unlike the inmates I have seen in prisons: jean-clad, sporting tattoos, talking easily with their companions. The comparison makes me uncomfortable, and I am glad when Jones arrives.

Over the past three years he's observed the changes in Susanville's youth, and the bottom line: juvenile delinquency has steadily increased, in both the number and scope of incidents, including truancy, petty theft, vandalism, fighting and problems associated with drugs and alcohol. There are gangs as well, especially the Hispanic North and South gangs; the Roman numerals XIV and XV are painted and scrawled on random walls, signifying affiliation with one group or the other. In one month alone, January 1998, juvenile gang violence was responsible for the beating of a student in the Safeway parking lot, the stoning of another, and the breaking of still another student's leg in three places in front of the high school. All three incidents led to hospitalizations. In December 1998, a sixteen-year-old honor student was severely beaten by a group of teens who call themselves the X-13s and wear gang colors. After weeks of terrorizing and death threats—the gang allegedly would park in front of the student's home and yell "we're gonna cap your ass"—the mother of the victim is leaving town with her family.

The town has responded. Recently, the juvenile hall more than tripled its capacity to fifty beds. Jones has had to take two guns, one a loaded .357, off kids in the past few months. He's seen the drugs get harder—from crank and the "blunt," a Philly cigar emptied and filled with pot, which is best, apparently, dipped in honey and microwaved for 3-5 seconds—to heroin, smuggled in and out of the prison.

None of this surprised Jones or his colleagues much. What surprised them was the origin of most of the problems.

"We expected trouble with the inmate families," he says. "But what we got were problems with the CO families."

Very often, a facility with so many Level 3 and 4 inmates, many of them twenty-five-year to lifers, will draw families who relocate to be near their husband, father, brother, son. The repercussions of this—several hundred people, many on welfare, many of them Hispanic and African-American—could feasibly flood an insular, small town with social service problems, from juvenile delinquency to racial strife. The high school administration had these kids "red-flagged" and were prepared for trouble, Jones says, but while he has handled only about five inmate family cases, he's dealt with more than fifty CO family cases.

"We weren't prepared," Jones acknowledges.

The CO kids, coming from urban centers, are more sophisticated, more impatient, and more noticeable in their urban-hip outfits, says Jones.

"These kids live in a paramilitary household. But really they don't have much supervision. They've got nothing to do."

For small prison towns, such as Susanville and Corcoran and Avenal, the additional inmate population—about half of each town's listed population is behind bars—means another $200,000 to $500,000 annually without any corresponding demand on most city services. Inmates don't drive—they don't call the cops.

And when cities in the early 1990s complained about the prison impact on court and sewer systems, for example, the state agreed to kick in additional cash to cover both. In other words, when an inmate has a court date for a crime in prison, the state, not the county, picks up the tab.

The money has widened roads in Corcoran, built sidewalks in Avenal and purchased a few police cruisers. But it hasn't led to significant economic development near the prisons. It appears that only larger Valley cities such as Hanford, Visalia, and Tulare saw a slight surge in new homes and stores. The prison towns did not.

At sunset, I walk down Riverside, the street that cuts through the mill district, where most of the inmate families live. It's a far cry from CO Row on the other side of town, where correctional officers live in brand-new houses with driveways full of brand-new American trucks and SUVs, boats and jet skis, courtesy of a job that pays over $40,000 in a town where the median income is about $27,500.

Not long ago, when my brother was still in high school, we had a house on Pardee Street, off Riverside, and we'd walk down to the river in the summer and spend our days swimming and sunning on the rocks. Back then, this was a town where you could recognize kids by the resemblance to their parents, where dogs would take naps in the middle of the road, where you never had to lock your doors.

Today the town's a modern version of the Wild West, only the cowboys are the guards and the Indians are the inmates and the inmate families. Here in the mill district, the asphalt's crumbling and a swath of dirt subs for a sidewalk; skinny cats slink through tall grass. Many of these residents have a father or son at one of the prisons, and sometimes it's not just the family that moves here, but the friends and "business acquaintances" from Fresno, Vacaville, L.A. High Desert is gang-infested and it doesn't stay inside the walls.

Already used to the mill stink after a block, I notice a young Hispanic boy sitting on the steps in front of a small house. From inside, an Aerosmith song is blasting with a fist-like beat. The boy holds a blue water pistol on his knees. As I pass he looks at me with a cool intelligence, as if he knows all the trouble that could descend on me and is deciding whether to initiate it.

I risk a smile and he waves absently at me—it is unclear whether in greeting or dismissal.

One afternoon I meet with Misty, a pretty seventeen-year-old "inmate kid," who lives in a group home and attends a community school whose windows offer views of the county jail, the juvenile detention center, and the Susanville Cemetery. She says the community school exists for "fuck-ups," though it's clear that despite a mother addicted to crank and a father with an address at High Desert State Prison, she is most definitely not a fuck-up. In fact, she's active in dance (ballet), a responsible worker (part of the Taco Bell crew) and in the past three weeks she's tripled her credits and is now eligible to be a senior at Lassen High, from which she was expelled last fall for beating up a female CO student.

"We were friends, but then she started messing with the group home girls. A glass bottle was thrown and then I just went at it," says Misty, who looks young for her age and is probably the last person you'd expect to blacken a classmate's eye and, when the girl drops to the ground, knee her in the face.

"I'm not proud of it," she says, looking off to the west, where her father will serve eighteen more months of a two-year sentence for parole violation. Her thirty-six-year-old father, unable to kick the drug habit, has also lived in San Quentin and Vacaville prisons. Misty and he correspond through letters and she is trying to work her schedule so that she can visit him. She admits she's nervous about going to High Desert.

"I've heard a lot about that place," she says. "It would be better to visit him at a drug treatment center. Isn't that where he belongs anyway?"

Misty hangs out with the "inmate and jail kids," a clique, along with the "CO kids," that one finds only in prison towns. The lines are clearly segregated, she explains.

"They're spoiled brats. The CO kids flaunt their parents' money and wear Tommy Hilfiger, DKNY, Calvin, cell phones and pagers. They party and spin out but they're also the ones who get straight A's. I don't know how they do it."

The CO kids aren't the only partiers; in fact, Misty informs me, only the band members are clean.

"There's nothing to do except party—that's why there are so many drugs," she says. Misty moved here two years ago from Vacaville, which she misses.

I ask her if she ever worries about following in her father's footsteps.

"I've seen him live and learn and fall. I don't want to be that person," she says.

Ironically, the increase in domestic abuse and juvenile strife didn't surprise many people. Susanville, like many country towns, is a place where violence is just part of the natural order. Last summer I leaned on our fence and watched our neighbor brand and castrate his herd. Several times he had to stop and bring back his weeping, frightened grandson; the boy, perhaps four or five, clapped his hands over his ears as his grandfather sliced the testicles off the bellowing, rolled-eyed calves and then seared their flanks with his brand, the smoke rising like campfires. The lessons are learned early around here; toughness is bred into you.

Once my brother told me about an incident from his sophomore year in high school. He and a friend were playing cards in his family's garage, and after a slight argument the friend picked up his father's nail gun and calmly aimed and shot nails at my brother.

"You have to be hard in Susanville," he told me. As a new student he was given an unofficial initiation when a group of boys took him four-wheeling out in the desert. Alone in the back of the pick-up, he clung to whatever he could as they ran and skid over dips and bumps, the object being to bounce him out. For days he couldn't walk for the bruises.

The acceptance of violence in a place like Lassen County, where the living has always been hard and the soft rarely survive, makes its own kind of sense. A certain comfort with violence is necessary where the main sources of income come from the natural world—from felling timber, clearing land, digging for gold, breeding and slaughtering cattle. But when the second prison came in under the political wave of "get tough on crime," the colliding of the sense of violence arising from necessity, of survival, with the violence associated with a maximum security prison, produced a pervasive sense of antagonism.

"You can feel it in the air," Tony Esparza, who teaches landscaping skills at the prison, tells me. "It's not just out at the prison, it's right here."

In a town where high school football takes on a kind of religious fervor ("If you don't play football you ain't nothin'," one young boy remarked), the pitting of "us against them" is an easy sell. There are the locals against the CO families, the COs against the inmate families, the bitter and random battles of the gangs. The most prevalent "them" is the inmates, and the feeling is manifested in random and curious ways. Take this example: on a wall at the Iron Horse Gym hangs a large, color poster—a blown up photograph actually. It depicts a group of about ten muscled, stone-faced inmates, shirtless or wearing tank tops, all staring defiantly into the camera. The text, in a form of Darwinian psychology, reads: "THEY WORKED OUT TODAY: DID YOU?"

For the prison tour, I dress carefully. No perfume, hair pulled back, flat shoes—something you can run in. I've been to prisons before, on tours, as a writing teacher, and this is my second to High Desert. I forego breakfast; I'm too tense to eat. Spending time at a prison is not something one gets used to, any more than one might get used to a dangerous and unpredictable animal. The tension in the air at a prison—and particularly in maximum security facilities—is one gesture away from violence, felt rather than understood, a tension that will stay with me long after I leave the gates behind.

Driving north on Johnstonville Road, I'm always struck by this shadowless land, bleached and empty save for the sage and wheat grass, dwarfing everything that has the nerve to make this place home: a juniper tree, a shack, the few houses, a horse. The land swallows up whatever's set upon it. High Desert and CCC come into view on the right. Together, the prisons occupy nearly 1000 acres of desert, set on a terrain that rolls and spreads like an unnamed planet for the mad and the lonely. A flower here seems an alien and wondrous thing. The institutions not only confirm but seem to incorporate the surrounding desolation, blending into the distant desert hills, where on clear days the U.S. Army detonates bombs that explode in great flashes of orange seen long before heard.

At first glance, the scattered houses close to the prison seem abandoned. A rusted car lies belly up in the dirt, and everywhere boards, boxes, broken furniture. But then you see a small girl in green overalls, picking her way through a yard. If she had a ball, she would not have to walk far to throw it against the prison fence. You wonder what she thinks of her neighbors.

You might also wonder about her safety. CCC has had many escapes over the years (in a two-year period, from August 1995 to August 1997, thirty-three to be exact). But High Desert hasn't had any, and doesn't expect to. Everyone in town knows about the state-of-the-art measures, the elaborate alarm system, the electronic display screens with schematic maps, the constant ID checking, the six-time a day head count, the thirteen gun towers with a 360-degree overlook of every foot of prison yard. These measures were, in fact, part of the sales package for the town. Escape, as the townspeople were reassured, is nearly impossible—an inmate would have to be flown or smuggled out. No one can get by the sixteen-strand lethal voltage fence with enough electricity (85,000 kw) to kill a man eight times over. The "death fence" is, nevertheless, monitored twenty-four hours a day by a guard in a truck who circles it at a lazy five m.p.h., gathering the charred ravens, rabbits, lizards and the occasional snake who get too close.

Like most prisons, High Desert spends more than half of its $81,533,000 budget on custody costs ($12,000 per inmate, per year). The bulk of the $60,000,000 payroll goes to the COs. Lieutenant Paul Edwards escorts me through the series of gates and corridors that lead to one of the Level III yards. I show my driver's license and gate clearance form five times during the tour. Around us, COs are on their way to various areas, cell blocks, yards, the administrative offices. Most of the time they're quiet, but at other times there is the comradely feel of factory workers on their way to the line.

"Randy, you seen my new truck?" one CO asks another, who says no.

"You will!" and they both laugh, not as rare a sound in prison as one might think (in fact, as one CO told me, "I've heard inmates sing").

The staff oversee inmates' movements every minute, including when they sleep. During my tour, as I observe the "free hour" in the day room, in which the inmates shower, play cards, watch TV, or stare at the walls, I am embarrassed to see a man, not fifteen feet away, slip out of his clothes and begin showering with only a glass wall between us. Another inmate shaves a friend's head with an electric razor. Others sit around in their underwear.

"This is their house," the CO remarks when he sees my surprise.

The lack of privacy is startling. Even the toilets are wide open to view via a picture window. Most unnerving are the halls with see-through ceilings, over which an armed guard strolls back and forth. The inmates eye me and saunter around and hang out at the tables. Racially and according to gang affiliation, they're segregated: blacks on the east end, Aryans and Southerns on the west. The day room feels very much like a recreation hall stripped of its foosball, pool tables, and vending machines. But it is much more sterile than any rec room—no posters, no rugs, no cushions, no color—just bolted down steel tables, chairs, and benches on gray cement floors. And then there is the smell, the smell of an institution: that unpleasant mix of metal and disinfectant which almost covers the human scents of sweat, breath, and the faint trace of urine.

In another block we wait for yard time, when the second tier goes out to the yard to exercise and the first tier stays for day room, an arrangement that alternates daily. But something has happened, and so we wait. The men, locked in their cells during the delay, stare out the narrow slits of their cell windows. The frustration and confusion is almost palpable. Some pace by their windows, the passing is swift because of the tight space; they might as well be turning in circles. Three or four inmates are out of their cells, and a CO addresses one, a slight Latino.

"Jorge, get me that push broom."

The inmate says "okay" and heads for the broom. Such a simple exchange, holding within it the entire prison dynamic of authority, obedience, and order. The lieutenant, who will be promoted soon to Sacramento, tells me the men are quieter because I'm here. Anytime I look around, at least two dozen pairs of eyes are pinned on me. He says they're not used to attractive young women, and the words are not a compliment but a statement of fact—and a warning.

As I drive away, it occurs to me not for the first time that it is only when I leave a prison that I most fully appreciate the meaning of the word "freedom," and I wonder what the prison employees think when they leave toward what is, for now, their home.

On my way to Rumors Sports Bar & Grill—I need a beer—I come to a stoplight next to a van full of prisoners, in glaring orange uniform. They look down at me from their windows like overgrown schoolchildren. They're smiling because this is fun for them. I flash a grin and drive on, only a little unnerved.

Rumors is empty except for a sad sack of a guy at the bar and two women downing shots of Jack Daniels at a corner table. Phantoms swirl in the smoke and dust-filled air, figures shaped from the late sun slicing through the blinds. On the radio, John Cougar mourns his little pink houses.

I flip through my notes and think about a conversation with my friend—that you can't escape the prisons' presence. We had talked of souls, of whether souls have a voice. If so, what happens when 10,000 miserable souls are confined in one small place? What kind of voice do you hear then? Of course there is no measuring, but it provokes the underlying question: can any economy based on human punishment be good in the end? And the employees who spend eight, sometimes sixteen hours a day in that environment—how much can a small town bear?

When I go home it's different now, and of course that's the paradox; you can't go home again because you've changed, but in this case it's home that's changed. And I can no longer ignore a discomfiting idea: the profound truth of a prison town is that its future is sentenced as surely as the inmates'. Most of the inmates, though, can leave when their time is done, but the town will never leave the prison. Or more precisely: the prison will never leave this town.

No escape. The sad sack sidles over and sloshes over his words, "what are you writing?"

A letter.

"Is he in jail?"

It is ironic that the most concrete example of the change in Susanville—the prison itself—takes on its own abstract symbolism. During the day, no one could mistake the prison for anything but what it is, with its gray cement structures, high fencing with spiraling razor wire, guard towers with tinted glass—and silence.

But it is at night that the prison seems to take on a life of its own. At night, the proximity of the town to the prison is most evident because of the lights. Since more than half the inmates are Level III and IV, the prison is surrounded by thirty-foot-high poles topped with glaring amber lights. The resulting glow changes the night sky, affects the entire county—the yellow glow can be seen from fifty miles away, and even planes flying over Sacramento, 200 miles to the south, can see the prison. On overcast nights, the clouds reflect the prison's light, casting the sky into an eerie, hellish spectacle, like embers from a tremendous firestorm, fallout from a war.

The town was furious: the lights illuminated not just the irrevocable change to their environment, but their powerlessness as well. If the state had stuck with the original plan of a low security prison, which voters approved, fewer lights would have been needed. The Committee to Restore the Night Skies formed a lobby to shield the lights or to reduce their number. But after three years of outcry and meetings and petitions, for security reasons the lights remain.

Despite the problems with the prison—the gangs and domestic violence, the increasing prices and strip-mall growth, the transience of the prison employees, the vacant housing, the would-be developers who scorn penal towns—what most people complain about are the lights. They have come to represent the ultimate, and intangible, cost of High Desert State Prison.

"When I first came to Susanville about ten years ago," my mother told me, "it was at night and your brother and I drove over Highway 36 and saw the town below us like a little constellation of stars. It was so dark all around and the town seemed to just hang there in mid-air, like some fairy village. Now you see this tremendous area rimmed with horrible yellow lights—and it's all you can see."

My brother, returning after a year at college, said he will never forget the change.

"I came around the Bass Hill corner and I couldn't believe it. There was the prison, bright as day. It looked futuristic, unnatural, something out of a science fiction movie. Like some giant alien mother ship had landed."