A Symposium on Secret Spaces

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

As part of this year's special issue of MQR devoted to "Secret Spaces of Childhood," a letter went out to authors inviting them to contribute a brief commentary to a forum on the general topic. Along with the memoirs, essays, fiction, poetry, graphic artwork, and book reviews in the double issue, this symposium is intended to help provide an iconography or conceptual map of the regions of childhood. The general commission posed to authors was the following:

The commission was not meant to be prescriptive, but suggestive, and what follows provides a striking variety of places and behaviors, in a variety of prose styles, all of the commentaries sharing the condition of being intensely memorable vignettes. From them readers can make some conclusions about the situations and spaces that need preserving and extending because of the salutary influence they exert upon the human imagination and the human spirit.

A two-line identification tag precedes each commentary: a book, or two, an institutional affiliation, an award. Most of these authors have published books directly relevant to the general topic of this issue of MQR.

Wayne Booth

A Rhetoric of Fiction

George M. Pullman Professor of English Emeritus, University of Chicago

I can remember so many secret spaces, starting about age four, that it's hard to resist doing a whole book on them. When I was six, my father died suddenly of Addison's disease, and memory says that life with my mother and my two-year-old sister was overturned in ways that no written record could reveal. Somehow from then on I led what seems to me now not just a double but a multiple life:

And so on.

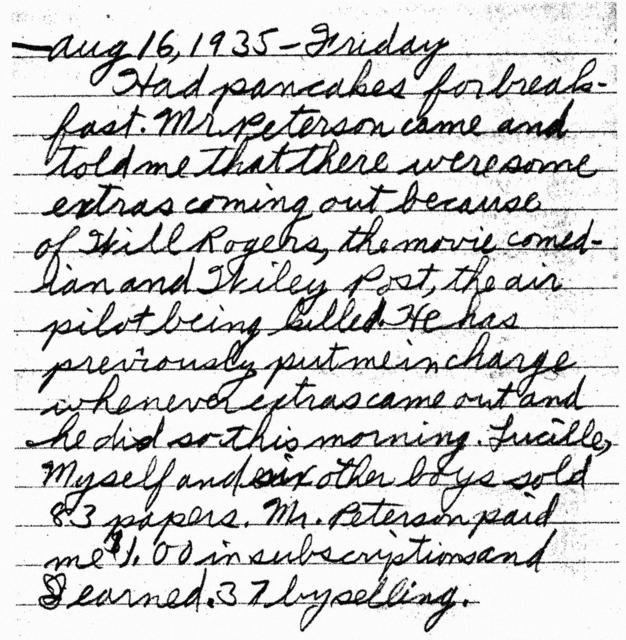

When I turn from memory to my early diaries, begun at age fourteen, I don't find anything about the weeping sissy or my mother's nagging or my occasional thievery. Rather I find three sharply contrasting "Wayne C.'s" (my official name had been "Clayson" until my father, Wayne C., died). Perhaps most prominent is the would-be hero, the egoist aspiring to be honored as "at the top," in every direction. He's the one who proudly records, a year or so later, "Have been accepted for membership in the Book of the Month Club." Then there is the poverty-driven pursuer of cash, willing to work hard delivering and selling newspapers, or working for twenty-five cents an hour on a farm, proud about being able to save money by gluing rubber soles to worn-out shoes; his mother takes in less than $100 a month as an overworked elementary school teacher, and she is always short of cash (I wonder why the diary never records that he would occasionally pick her purse). Often overridding these two and all the others, there is the self revealed in frequent expressions of anguished guilt: the would-be saint, a pious, devout Mormon, struggling with an insurmountable awareness of character flaws, including self-reproach about pride and ambition (and implicit awareness of more serious misdeeds). The most striking—and most secret—moment of conflict among the diverse "Wayne C.'s" is only half-revealed in separate diary entries. The conflict was discovered, accidentally, by only two people: his mother and his newspaper boss. He began delivering newspapers shortly before starting the diary, and he soon found his boss insisting that he sell subscriptions.

For quite a while he failed to sell any subscriptions at all, and he never became very good at it. Yet the diary makes him sound successful from the beginning, and often boasts about increasing sales totals. What he is willing to boast about is amusingly revealed by the following entry, written after selling "extras" on the main street of a town with 3000 inhabitants.That inept salesman soon got captured by the excitement of sales contests. The egoist wanted to win, to be "honored" as number one, honor being seen as reducible to whatever prize was offered.

The company gave every delivery boy a small cash gift for each subscription sold. Naturally the money-grubber self wanted to earn a lot of money, while the honors-seeker figured out that since the cash gift for each subscription was almost large enough to pay for a full month of deliveries, he could chalk up a fake subscription at very small cost. So his divided selves faced a dilemma: if he entered fake subscriptions, his chance of winning the contest went up fast, while his income went down only a small amount for each subscription. Which was more important, fame or cash income? The egoist won, hands down, and his subscription rate went up and up, finally leading to his winning a contest.

No hint there of any guilt about cheating. A few pages later he boasts that he has been chosen by the bishop (the head of the congregation) to become "the supervisor of one of the Deacon's quorums. I consider this quite an honor." Again there's no hint of any conflict between that pious achievement and what he is doing each month as he records fake subscriptions.

Suddenly the whole episode, with its fame-winning facade, crashes: he contracts Bright's disease and hears a doctor speculate about possible death. He has to turn over his routes and records to the boss, and they reveal a total jumble of dishonest subscriptions and careless juggling of data: a huge cash debt (actually quite small, as I consider it now), and incontrovertible evidence of non-existent subscriptions.

His boss turns out to be a generous man: he waits until the boy is back on his feet and attending school again, after two months at home, before he shocks the mother by revealing his discoveries. He did not turn Wayne C. in to any authorities; all he insisted on was some more work, without pay, until the losses had been paid off. Does the diary reveal the truth of any of this? Not at all. It talks as if Wayne C. were now simply working a few hours again for his old boss but in a different job. Does it confess to any guilt about it? Not at all. While confessing guilt about masturbating and about being egotistical and about being "too critical" and about "boasting too much," it never acknowledges that the crazy desire to be number one had produced an atrocious hypocrite reveling in being a winner.

Occasionally the later entries do, like this report, reproach the boy strongly for his ego-driven aspirations. But they seldom reveal openly what memory records: many other moments when the would-be saint conceals his struggle with desire for fame and desire for money.I'm naturally tempted to conclude by boasting a bit (oh, yes, I still have to deal with such temptations: I hope, for example, that this account will appeal to many readers) by celebrating the boy's grappling with the very theme of this collection: secrecy, and its limits. Aware that he has many faults, and that he has revealed many faults in his diary entries, he wonders about just who should read what. In the middle of his sixteenth year, he concludes his first volume with a twelve-page confessional about his many faults, including the "sinful" fact of having "periodical sexual excretions," some of them by "violent physical agitation producing the flow of liquid." (He apparently does not yet know the word "semen.") Then he says, "I still don't know whether I should write this or not. I wish that I had a more adequate brain to be able to know what to do. . . . I cannot blame this sin on not knowing of its being a sin, because I knew it was so. . . . I have heartily repented and have tried & succeeded to keep from repeating." Which of course could not have been true. But then, still to my astonishment, he addresses directly—and in a sense honestly—the question of silence. He turns to the frontispiece of what he labels Volume I, and writes the following:

So the sixteen-year old has decided that at least one of his secret spaces should no longer be kept secret—provided readers are at least six months older than he is as he writes!Paul Brodeur

The Stunt Man

Staff writer, The New Yorker, 1958-1996

It was the summer of 1942, and our family had made its annual migration from Boston to a rented cottage on Duxbury Beach, some forty miles south of the city. My father came down on weekends; my mother spent her days at the cottage tending my infant sister; and my brother and I, clad in bathing suits that had faded and dwindled into ragged loincloths, roamed freely from morning until night. The beach was a sandbar peninsula seven miles long, with the ocean on one side and Duxbury Bay on the other, and, except for a few summer people like us, who lived in cottages near the mainland, and some Coast Guardsmen out at Gurnet Point, it was uninhabited. A dirt road that ended at the cottage colony and a wooden bridge that rambled across the bay on piles, a mile farther along the peninsula, were the only routes of access. On Saturdays and Sundays picnickers came over the bridge and spread themselves upon the sand, but during the week the beach was deserted.

Like all boys at the seashore, my brother and I were beachcombers. We poached quahogs, collected driftwood, captured minnows trapped in tidal pools, and filled gunny sacks with pop bottles left behind by picnickers. But, above all else, we considered ourselves patriots. We salvaged tinfoil for the war effort from discarded cigarette packages, helped local residents dry sea moss to collect nitrates for munitions makers, and used the pop-bottle refunds to buy Victory stamps at the Post Office.

The war affected us in many ways that summer. There was a strict blackout every night, and when we went outside before bedtime, the unaccustomed darkness and the profound sea made us feel close and vulnerable to the conflict. Wreckage washed ashore from ships sunk by U-boats, and each day we poked through fresh piles of debris, vaguely aware that we were examining the flotsam of catastrophe. The grownups talked incessantly of a submarine that had surfaced off the shore during World War I and lobbed a few shells into the marshland behind the beach. Had the Germans been aiming at the old Cable Station? Would they try again? The speculation of our elders filled us with delicious tension. The tin cans my brother and I were forever tossing into the waves became submarines, and the rocks we threw at them depth charges, and the constant vigil we maintained for flotsam, pop bottles, and marine life took on a new dimension. For now we were patrolling a stretch of the coast—a strategic flank of the republic.

As it happened, our favorite place to play—indeed, our secret position of defense—was an abandoned duck-hunting camp that lay hidden in the dunes several miles beyond the old bridge and almost halfway out to Gurnet Point. The camp was a rambling frame-and-tarpaper affair, upon which time and the elements had wrought a deceptive camouflage. Winds and winter storms had so shifted the dunes that it was nearly buried. Foxtail and beach-plum bushes had taken root in sand covering the rooftop, and only in a hollow on the leeward side was any part of the building visible. Here my brother and I had torn away some rotted boards and fashioned an entrance.

The interior of the camp was cavernous and dank. It consisted of four rooms, three of which were half-filled with sand that had sifted down through cracks in the roof. In the largest room, there were several bunks with mildewed mattresses, a rusted iron stove, some overturned chairs, and a long table. For us, these were the furnishings of a bunker from which we operated against the foe.

A typical day found us lying on the summit of a nearby dune, waiting to ambush enemy saboteurs who were disembarking from their rubber boats. When they came into range, we unleashed a volley of shots at them from toy wooden rifles. Then we retreated to the invisible fastness of our fort and hid until they stumbled, with Teutonic stupidity, into our line of fire, giving us an opportunity to decimate them with additional volleys fired through apertures in the rotting planks. Fierce struggles took place as the last fanatic attackers breached our bastion. It was hand-to-hand for more than an hour, as we backed slowly into a corner, each forefinger a revolver that barked incessantly, firing at Nazis who were climbing through holes in the roof and dropping grotesquely dead at our feet.

On one of these days, reality intruded upon our game in the form of an explosion that sent a shower of sand upon us from the sagging roof above our heads. The beach, it turned out, was being bombed and mock-strafed by low-flying Army airplanes taking part in a training exercise being conducted by a National Guard regiment that had rumbled out across the planks of the old bridge that connected the peninsula to the mainland. The officers whom we encountered as we tried to run home seemed almost as badly frightened as we when they realized that they had failed to clear the beach properly, which is how (after being sworn to secrecy) my brother and I came to be adopted for one whole week as regimental mascots, and, to the envy of all our friends, were allowed to eat with the soldiers in their mess tent, help them dig foxholes, wave signal flags, stand inspections, and walk guard.

The saddest day of my life till then was the day my brother and I stood at attention, after the last tents had been struck and a long line of soldiers had given the beach a final policing, and watched a column of trucks and jeeps rattle back over the old wooden bridge and on to God only knows how many other beaches.

Seventeen years later, not long after I began what would become a thirty-eight-year career as a staff writer at The New Yorker, the magazine published a short story of mine entitled "A War Story." It was a first-person account of the events of the summer I have just described, and it began with a sentence that reads, "This is one of those stories that, for reasons of honor, have had to be suppressed."

That wasn't true, of course, but merely a literary conceit to explain tongue in cheek why I hadn't written the story before. At the time—it was 1959—I had no idea that I would spend most of my tenure at The New Yorker unraveling the dark secrets of the manufacturers of asbestos products, and those of other captains of industry, who were inflicting disease upon their workers and poisoning the land, as well as those of government officials, who fostered the climate of secrecy that cloaked so much of our national life during the Cold War.

It may be revealing that in a 1997 memoir, Secrets: A Writer in the Cold War, which gives an account of my experiences as an investigative journalist, I include a few sentences about the adventure that befell my brother and me on Duxbury Beach in the summer of 1942, and a longer section about a family secret that my parents kept from me. Having been sworn to secrecy about what had happened on the beach by officers of the National Guard regiment, we never breathed a word of it to our parents. Nor did they ever tell me about my father's previous marriage and a half brother to whom I had been given almost the same name, even though I must have suspected something about it and him at an early age.

Like everyone else, I have been touched as a child by secrets.

Today, a pair of carved decoys from the old duck hunting camp sit on a shelf in the living room of my home on Cape Cod. They remind me of the secret place in which my brother and I waged our fantasy war, of how lucky we were to have been so young, and of the power of secrets kept and those revealed.

Frederick Buechner

A Long Day's Dying

The Eyes of the Heart: A Memoir of the Lost and Found

I can think of two "secret spaces" which, looking back, I recognize were really one and the same. When I was a small child my family spent summers in Quogue, Long Island, and on the beach there; especially toward the end of the afternoon when the sun was starting to think about setting, I would lay a beach umbrella down on its side and lie curled up in the shelter of it with a wonderful feeling of snugness, safety, warmth, as the chill sea breeze whipped the sand around the edges of the ribbed canvas. After my father's death in 1936, when I was ten, we lived for a couple of years in Bermuda, where our pink house, The Moorings, was directly on the harbor across from Hamilton. When it rained, I loved to sit outside on the lawn in a canvas deck chair with a blanket of some sort draped over the sunshade to keep me snug, safe, dry, as I watched the downpour advance in sheets across the grey water and listened to its drumming above my head. To this day, age seventy-three, I can still conjure up in much of its original richness—especially at night in bed—what it felt like to experience both the wildness, wetness, windiness of things, and at the same time my utter protection from it.

Peggy Ellsberg

The Language of Gerard Manley Hopkins

Senior Lecturer in English, Barnard College

In the final daylight hours of the last century, with no particular plans for celebrating New Year's Eve, I went to a Victorian dollhouse museum in Santa Monica called Angels' Attic. I brought with me my daughters, Catherine and Nini, ages seven and five, dressed in matching red pinafores. The two other people in the museum mistook them for twins. I have grown accustomed to the pleasure observers take in spotting twins, like the brief thrill of sighting a rare bird. "Yes, twins," I lied, not wanting to disappoint anyone.

Like a snow owl or a set of small twins, a scale model or even something simply small—an electric locomotive train, a mocked-up cathedral, a hummingbird's tiny nest, a marshmallow peep yellow chicken in a basket—all rehearse for some grander but somehow diminished version of themselves. And replicas of homes, in particular, are especially pleasing. Creating altars dedicated to food and eating and coziness and sleeping in dollhouses strangely affirms what we do in our real homes. Entering the metonymic world of the dollhouse, we sense ourselves hidden and protected, empowered with a control that in real life escapes us. The message the miniature delivers contains both depth and delight.

Released into the exhibit at Angels' Attic, Catherine pressed herself close to the plexiglass covering an ingenious curiosity, a larger-than-a-seven-year-old-child-sized model of the Woman with So Many Children Who Lived in a Shoe. Frozen in time and receptive to poetic projection, like the figures on John Keats's Grecian urn, doll children spilled out of every room and over the thumb-sized furniture. Catherine wanted no one to bother her. She whispered to the harried mini-mother who, surrounded by a handful of doll children, slaved over a cook stove. Nini meanwhile stepped up on a bench and studied an exceptionally intricate workshop and dormitory for thimble-sized Christmas elves, themselves miniatures within the miniature. Nini, too, her cheek pressed to the plexiglass, began to whisper, answering secret questions. Immersed in their identical experiences of deep looking, I too stood there, gazing at them gazing at interior versions of interiors. Like receding mirrors or Chinese boxes, the miniature students of miniatures in the little Victorian museum absorbed by even littler museums embodied for me the muse of museums.

When I was six, I received a pink and grey tin dollhouse. It was nothing like a museum-quality dollhouse, Queen Mary's electrified plaything at Windsor Court, for example, not like the opulent mimicries of the haute bourgeois domestic environments available on E-bay or in the Nutshell News. Mine was an undecorated bread-box of a house, a 1950s Sears pre-fab. One just like it, plain as a potato, recently appeared on the Antiques Road Show with a price tag of $2000. In 1956, I furnished my tin house with pinecones and round stones and tables made of bottle caps and bobbie pins. I built altars into every room; some cotton batting served as bedding for a capped acorn, my she-baby. I was practicing for something. Kneeling in front of it, I entered a secret museum.

Plato says in his Laws that "the man who is to make a good builder must play at building toy houses, and to make a good farmer, he must play at tilling land." I realized, as Angels' Attic was closing, that my children were entering the psychic homes, practicing for a future of indwelling. But the museum really was closing. In a few hours it would be Y2K and outside the twilit streets were filling up with noise and adult visions of glitter and champagne.

"Are you sure they're twins?" asked the kindly lady, eager to lock up and go home. "What a question!" I answered, stalling. Persuading the girls to leave took some strategy, but actually, there was also a twin wonder outside, a double rainbow arching into the blue-grey sky. And as the girls looked up their faces were lit from within by a secret. One for each.

Noël Riley Fitch

Biographies of Sylvia Beach, Julia Child, Anaïs Nin

Teaches at USC and American University of Paris

A formal prayer, its denouement always blessing "the hands" that had prepared the overdone roast beef, was followed by formal conversation at our Sunday afternoon dinners. Social decorum reigned for the three Riley girls. When for once no one was looking in my direction and the family discussion picked up at the end of the meal, I would slide silently off the front edge of the chair, pass carefully under the tablecloth without disturbing it, and settle beneath the center of the family dining-room table. The conversation continued up there, but I knew I was safely on my "Moonie."

The legs of my two sisters and parents, and occasionally those of visiting dignitaries, were draped with the generous linen tablecloth and surrounded my secret space—protecting me. I was in a private and magical spot. No eyes. No prayers, challenges, or decisions. In charge of my own domain. Sitting with a grin on my face, I was secure in my cave, imaginatively holding my secret surprise.

A Moonie was what those couples went on after my father, The Right Reverend Dr. John Riley, married them and they walked up the aisle and out of the church. We had heard whispered talk of "honeymoons" for years and understood them to be secret and private places. No prying eyes. My innocent imagination wanted such a space for myself.

When I was older and had stopped my flights underground, my little sister began taking her own Moonie. Now we would playfully call out "where is Gail?" "Where has Gail gone?" But, unlike me, she could not contain her giggles and crawled out to confess that she had been on her Moonie. She never could keep a secret, never seemed to need one. By then I had accepted the truth that my secret place had been discovered. My escapes had always been observed. At any time my cave could have been invaded, though it never was.

Today, placemats have replaced long linen tablecloths, and there are few secrets. I have been married twice, and after each ceremony I did not, for one reason or another, take a honeymoon. But I remember the innocence and excitement, the warm semi-darkness of my childhood Moonies. What has remained of my childhood Moonie is a sense of being in control of my own privacy and a need for having a room of my own. I grasped this truth under the family table long before reading Virginia Woolf. Montaigne was right in comparing life to a shop, in which the keeper needs a "back room."

I need my own study and, preferably, my own toilet. My husband, who stirs humor into every secret place of my life, likes to raise my toilet seat to show he has invaded my space.

More important than this exaggerated sense of space is another lesson I learned in the public scrutiny of busy parsonage life: I learned to savor the pleasure of my own company. As a biographer I spend months, indeed years, at the table of communal history, interviewing persons and travelling to distant libraries. But when the full-time writing begins, I slip under the public cloth to give myself over to my own company and the solitary battle with facts and words. Indeed, I spend my time invading other peoples' secret places.

Mark Jonathan Harris

Academy Award-winning filmmaker

Professor of Cinema-Television, University of Southern California

When I was a child novels gave me the chance to participate in a wider, less circumscribed world than my own, one in which others shared my own fears and resentments, my desires and my unhappiness. I could cry over the death of Dora in David Copperfield, exult in the rebellion of Tom Sawyer and Huck Finn, relish the revenge of the Count of Monte Cristo. Reading helped assuage the loneliness I felt growing up, reassured me that I was not as strange or bad a person as I secretly feared.

By high school the authors I read had completely changed—Twain giving way to Salinger, Dickens to Lawrence, Dumas to Hemingway—but books continued to be a refuge for me, a place where I felt safe to explore roles and emotions I wouldn't consider elsewhere. When I got to Harvard, it seemed natural to major in English, but after only a few months of Humanities 6, I developed a fierce and implacable hatred for the so-called New Criticism. I didn't want to deconstruct the imaginary worlds in which I had spent so much of my emotional energy. I wanted to believe in their reality. Like certain emotions in my family, novels were best left unexamined. I still read them as religiously as before—I discovered Russian literature at Harvard—but most of the fiction I read was for myself rather than for classes. Books were still a private retreat, a hideaway I could visit whenever I needed, where I could respond more freely and openly than I often did with other people.

Perhaps because so much of my emotional experience came from books, after college I sought a job that would provide me more direct contact with life. I found one as a crime reporter for the City News Bureau in Chicago. The South Side police beat, from five in the evening until two in the morning, was a different world from any I had ever encountered. All the passions that were repressed or hidden in the sheltered community in which I had been raised exploded every night on the South Side. I would read the crimes on the teletype, diligently gather the facts from the police who investigated them, but found it very difficult to understand or identify with the stories I was reporting. After the first few weeks of hanging out at South Side police stations, I started bringing a book to work each night. For months I carried Crime andPunishment around with me the way the cops carried their riot gear, as a shield against the violence, the brutality, the senselessness I was encountering. For a long time Raskolnikov was far more real than any of the people I wrote about.

Daily immersion in violence cannot help but alter you. Often it hardens people, but in my case it pierced the bookish armor I had used to defend myself against the harsher emotions of life. After several months I was transferred to days and assigned to Family Court. I found the stories I covered—most of which never made the papers—heartbreaking. Day after day I watched children brutalized by poverty, neglect, abuse. Their pain and anguish began to affect me as strongly as the characters I read about.

In time print journalism led me to documentary filmmaking. In retrospect it's easy to see the unconscious attractions of this medium. The camera served as my new Crime and Punishment, providing me both access to strong emotional experiences and distance from them. As a filmmaker I could participate directly rather than vicariously in important social and political events, but, at the same time, I had the luxury of the editing room to process and interpret my experiences and to form judgments about them.

In my late thirties, although I continued making documentary films, I also started writing children's books—for some of the same reasons I think parents have children—to get a second chance to experience what I had missed in childhood (like throwing a full-blown, dish-breaking tantrum) or to redeem earlier failures and humiliations (finally standing up to the school bully). Writing books from a child's perspective gave me the opportunity to explore the world in a way I had been too emotionally constrained and restricted to do when I was young.

In the last year my work as a filmmaker, my interest in children, and my own history have all converged in a documentary I have written and directed about the Kindertransports. In the nine months from December 1938 until Hitler invaded Poland in September 1939, Britain rescued over 10,000 children, 90% of them Jewish, from Germany, Austria, and Czechoslovakia. Into the Arms of Strang ers (Fall 2000) chronicles the dramatic stories of these children, who were forced to give up their families, homes, even language, as they fled Nazi persecution to England.

Although the pains of my childhood do not begin to approach the traumas these children faced, I strongly identified with them—particularly the loneliness of these refugees living in other people's houses, in a foreign land where they did not speak the language and whose country was at war with their own. In researching and filming their story, I have been asking the Kinder, as they call themselves, a question central to my own childhood: In your unhappiness, where did you turn for solace? To my surprise, for many it was books.

One man, who came to England from Vienna as a seven-year-old, and who constantly feared being sent back if he upset his foster parents, remembers two favorite places in their home—one under the grand piano and the other in front of the open hearth coal fire, where he could spread out his books and comics and read "for hours on end." Always on his guard, desperate not to offend, he loved adventure stories most of all, stories where heroes could act boldly and decisively and never worry about the consequences.

Another woman, an avid reader as a young girl, turned to books for relief from the isolation and segregation she suffered as a Jew in Nazi Germany. When her parents decided to send her to England at the age of fifteen, what grieved her most was abandoning her collection of books. "I couldn't bear to leave them behind," she remembers. "I just burned them in the oven. It was wintertime. We had an old-fashioned oven that you fed with coal, and I fed my books into it, one by one."

When she arrived at the foster family in Coventry that offered her a home, her first shock was the absence of books. "It was absolutely traumatic. Can you imagine a house without one book in it? Nothing. Nothing to read. Nothing to learn English from." Her second shock was that the family had taken her in to be a maid for them and wouldn't allow her to continue school.

In making this film, I have been touched by the often desperate loneliness of these refugee children but also by the resilience and courage that sustained them through their trials in Britain, where, as Eva Figes writes, "the fact that I had arrived as a foreign child was never forgotten or forgiven, and with the rise of anti-German feeling after the outbreak of war my nationality was always good for abuse."

For Figes, too, books played a critical role in her ability to survive her uprooting. "Real books, that was perhaps the most important of many discoveries," she writes in Little Eden, a wonderful memoir about her wartime sojourn at an unconventional boarding school in a country town in Gloucester. A corollary of this discovery was the realization of her need for separateness, a place where she could be alone—to read, to think: "Perhaps it was because, even as a very small child, I had been conscious of a secret, solitary nucleus inside which nobody could reach. It held pain, but also dreams, and I needed to be withdrawn to allow it to grow."

The hiding place she chose for retreat, "where I would bolt myself in when I wanted to get away from everybody and everything," was the basement lavatory, cold and damp on winter mornings, but the one place she could brood undisturbed, work through her miseries and loneliness, let slip the mask she wore with other children. "By now I had begun to understand that my life involved playing a role, in the dormitory, in the classroom, even at play. It was necessary to appear happy, cheerful and integrated within the group, and in a situation where one was eating, sleeping, working and playing together it was necessary to find a bolt hole in order to give way to one's inner feelings."

For many children books continue to provide this bolt hole, allowing them to shut the door, however briefly, on the pain and confusion of their lives, and open a window into a world of dreams, of fantasy, of hope. If books can sustain children during the upheavals of wartime, as they did me under different circumstances, surely they can still be meaningful, even to today's Nintendo generation. Television, movies, internet chat rooms also offer children a chance to explore other roles and lifestyles, to expand their vision of themselves, but the experiences these media provide are essentially communal, rather than private. Books provide a private psychic space—the core of any secret hideaway—a haven where you are free to feel, to think, to imagine, and to dream.

Jim Harrison

The Road Home

Just Before Dark: Collected Nonfiction

As a poet and novelist I've grown rather inured to my own peculiarities but have long openly accepted my penchant for secret places, mostly thickets, that I depend on almost daily for solace. I can think of specific locations in Michigan, including the Upper Peninsula, but also in Arizona and New Mexico, a single place in New York City, one in Paris, and another near a friend's house down in western Burgundy.

The original, the ur-thicket, was near the porch of our childhood home in a dense collection of shrubs. I often retreated there for hours with my dog after I was blinded in one eye by a playmate. Soon after this accident (intentional) I also lost the dog because she was over-defensive but kept the thicket for years.

The prerequisite of a first-rate thicket is that you can see out but it is unlikely indeed that you'll be noticed by others. It is helpful to have a dog with me, even if it is a friend's dog, which is the case in Burgundy. Birds often visit. Once in a prized thicket in Arizona during a violent rainsquall I shared my thicket with dozens of rare vermilion flycatchers. They treated me as an equal.

I don't care for the idea of bullfighting but there is a Spanish word, "querencia," which refers to the place in the ring a particular bull feels the strongest, most at home, most able to deal with his impending doom. I'm sure that my thickets offer me peace in a life that is permanently inconsolable but reasonably vital and productive. Thickets quickly draw off the poison. After a few minutes of sitting you hear your own tentative heartbeat. What people clumsily call the "inner child" gracefully rises to the surface without much coaxing. Your normally watchful dog takes a snooze and occasionally you doze off yourself within these few yards of earth where you feel no dislocation and are totally at home.

Jerry Herron

AfterCulture: Detroit and the Humiliation of History

Professor of English, Wayne State University

I used to think about the room where I learned to read, for no better reason than it seemed to belong just to me, the way childhood things always do, when we grow up, with the portrait of George Washington, and the cheap, nylon flag, "I pledge allegiance . . ." each morning first thing, hand over heart, staring at the alphabet taped across the top of the blackboard (that really was black not green). And the radiators that when you'd put a Crayola on them, the hot wax would melt down and pool on the hard wood floor that creaked each step you took across it, and how that smell became the smell I always thought about first when I thought about the first day of school with the scents of pencil shavings and paper and paste made of wheat that if you wanted to you could eat it. (Bobbie Bentley did.)

And the cloak room in back, with doors you could close from inside, so all you could see were the patterns of light across your shoes that came through the air holes at the bottom, and how that's where the teacher would find William, balled up in a nest of coats, his face smeared with tears because he always got upset when we practiced writing in our Big Chief tablets with the cigar-fat pencils and he would make mistakes and when he tried to erase he would tear the page and start to cry with snot running down his lip and when his parents came home from their trip they found out his grandmother who they had left in charge had just gotten tired of him one day and decided she'd enroll him in first grade even though he was only three and a half, big for his age probably, so they came to take him home. And we all felt sad not because we would miss William, since none of us had really talked to him, but because we knew that nobody was going to find out a secret about us that would set us free.

I decided to look for the room where I learned to read, back for a visit, when I was forty and got stopped by a guard who made me wait until a teacher could come and hear what I wanted who was—the teacher—young enough to be my daughter, if I had one, but not beautiful like Miss Creer, my teacher, had been when I learned to read, in the Bluebird group (we were the best), and the young woman listened almost patiently and said sure take a look around, which I did, not being certain what room it was, but pretending I knew, they all looked the same now so what difference did it make, with the giant windows blocked out except for little gun slits at the bottom, and the ceiling dropped, with fluorescent lights and the cloak rooms gone where nobody would ever get to see how Kathy McNaren didn't have a belly button because it had been surgically removed and she would show you if you asked (even if you didn't). I wish I'd asked her why. And a little boy was sitting in the dark with the lights turned off so he could see the computer screen better and he looked up at me with the blue glow reflecting off his glasses so his eyes disappeared, like I was an intruder, which I was, bothering him while he was working, after school. Learning to read. Will he remember this room as if it had belonged just to him?I hope not.

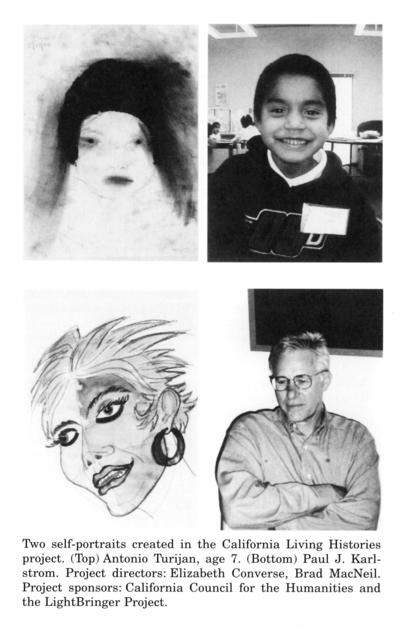

Paul Karlstrom

On the Edge of America:California Modernist Art, 1900-1920

West Coast Regional Director of the Smithsonian Institution's Archives of American Art

Image-making is fundamental to the journey of self-discovery. Writing and illustrating my own stories played an important role in my childhood. Having an imaginary world that I could populate and control as I wished was reassuring and helped me better understand the larger world in which I was obliged to operate. No doubt my own professional life, including studying and writing about images as cultural documents, began then. Art and image-making arise out of a fundamental human need to bring order to a difficult and often unpredictable reality. Recently I was inspired to look again at these childhood creative efforts carefully preserved by my mother. And as I studied them I understood for perhaps the first time their true meaning in my life: the creation of a world that helped me find personal continuity in a somewhat dislocated childhood characterized by the insecurity of frequent moves. Art provided a means, one that I deployed constantly (as evidenced by the number of early picture stories that remain), to enter a refuge of my own imaginative devising, a place to repair to after experiencing rebuffs (actual or perceived) in my efforts to make friends in a series of new neighborhoods and schools. It even provided an outlet for early teenage fantasies associated with the discomforting but thoroughly irresistible stirrings of sexual awareness. I learned at an early age that you could have at least some of what you long for by creating images with pencil, pen, and watercolor.

The thinking and understanding that goes into creating pictures may well provide a sense of at least a degree of control (the term "agency" is often used to describe this phenomenon) of one's world. As I drew my own self-portrait with my young colleagues at the Learning Center, I realized the advantage they had in being less self-conscious about art than adults are. The process that the children have embarked upon at the Learning Center is something akin to discovering oneself in an invented "secret space" and drawing from it the courage to step out and engage the world as more self-aware individuals. My own practice continues in the personal realm as I craft collages that are basically visual manifestations of my interior life. Slowly these personal and frequently quite revealing images are entering into a more public realm, either as gifts to friends and sympathetic associates or, more recently, in artist-organized "underground" exhibitions. It occurs to me that as I share these small pictorial "confessions" with an audience, however limited, I am acknowledging who I am as an individual or at least how I understand myself.

As a grownup I find myself an employee of the Smithsonian Institution, directing the West Coast activities of the Archives of American Art. In that capacity it has been my charge to locate and acquire for the national collections letters, photographs, diaries, and related historical documents. The focus of the Archives has been preservation of historic records for use by scholars and writers, a "high end" educational constituency. However, the official Smithsonian motto is the "increase and diffusion of knowledge." Broadly interpreted, this would seem to encompass the purposes and goals of the California Living Histories project. And it seems most appropriate for us to pay attention to the young people who may well grow up to use our scholarly collections. But far more important, it seems to me, is to be involved in the seeking of (self) knowledge, the ultimate humanist goal and reason for studying history in the first place. And it further occurs to me that many of the more personal documents (the intimate letter or personal sketchbook, for example) I collect for study by historians are, when all is said and done, nothing other than adult versions of what children—myself or those at the Leaning Center—have carried back from individual "secret spaces." I suspect that we never outgrow the need for and ability to learn from these comforting and refreshing alternative worlds of our own imaginative invention.

Nan Knighton

Book and lyrics for the musical The Scarlet Pimpernel (Tony nomination)

Stage adaptation for Saturday Night Fever

I suppose I was afraid all the time. I remember living in a constantly vibrant state, jangling inside, ever-vigilant, looking over my shoulder. I didn't talk about my fears to anyone—children usually don't. I lived in a leafy neighborhood in Baltimore, Maryland, and my life, by any standards, was idyllic. From ages five to nine, I appear in each photograph as a smiling child with golden curls. But I look back on these years and see quite clearly that the pulse of my every day was fear.

Fear of what? Well, you could make your list. Here's a partial list of mine: 1) Mrs. Bellows, across the street, was referred to as "the crazy woman" and my friends and I would dare each other to run up on her lawn. Invariably, she came hurtling out of the house in a nightgown, screaming at us that we were terrible children and were going straight to Hell. We'd tear away, breathless, just as her nurse emerged to yank her back inside. 2) A friend of my brother's died when his sled hit a metal pole sticking out of the snow. 3) My friend Sally drowned at age seven when her parents were foolish enough to go boating on the Chesapeake Bay during a storm. 4) Catherine, the lady who lived next door and was a surrogate grandmother to me, had a husband who was a doctor, a man with no patience for children. One day when I was touching some of his prized glass figurines, the doctor slapped me across the face. In order to retain diplomatic relations with the neighbors, my parents did not confront the doctor about this incident—it was glossed over and dropped. 5) Catherine died a year later. She drowned in the bathtub. People said it was an accident. I overheard my parents whisper that it might be "suicide." (When I was a teenager, my father confided his belief that the doctor had murdered Catherine.) 6) My brother told me he belonged to a club of eagles. He hinted they might let me join the club. The eagles would come to my window every night, he said, and watch me. If I moved even an inch, they would fly in and kill me. I was five years old. How many nights did I lie paralyzed, sweating and terrified? 7) When my brother was eleven and I was eight, he suffered an anomalous stroke and lay in a coma for two days. For me, the worst part was being alone in the house with him when he first collapsed, stumbling through the neighborhood to get help, hearing the howl of the ambulance. And then my mother came home and shook my shoulders, screaming at me, "What happened? What happened?!"

Those were some of my terrors, but every child has them—bedtime illusions of creatures perched in the dark on that corner chair, nightmares of monsters, fears of kidnapping, abandonment, or that great mystery—death. And, of course, the unluckiest children deal directly with abuse. In a way, fear is the biggest revelation of childhood, the worst surprise: "Oh. Bad things do happen." And yet somehow it's kept secret. It's all held tight to the chest. Why don't children talk about it? Wouldn't it be infinitely logical for a child to go to her parents and say, "I'm a wreck. I think eagles are going to peck my eyes out and the crazy lady across the street is going to eat me alive and how the hell could you let that doctor slap me?" Why do children keep their fears secret? Are they trying to be little adults, imitating their apparently stoic parents? Are they doubly afraid to disclose the horror lest somehow they are at fault? One thing I do know is that children have an amazing ability to dissociate, to simply block it all out. ("Hmm. My friend just drowned. Guess I'll go out and jump rope. Now I'm jumping rope. I'm fine.") Maybe the only way a child can cope with the newly discovered terrors of the world is simply to disable them and substitute a preferred reality. In my case, I wrote. I taught myself to read and write at the kitchen table. I did it regularly and assiduously, with a child's picture dictionary beside me, copying words, sounding them out. I think when I wrote, I must have entered a safe zone.

In this poem, life's about as rotten as it gets, but there's that happy ending. As I read through the folders of my old stories and poems, over and over the little girls or boys I created were surrounded with horrendous dangers and sorrows, but I always made them end up "happily ever after." I suppose part of this may have been a by-product of growing up in the 50s, but my gut feeling is that happy endings simply quelled my fears. If I wrote them, then, on some level of reality, they existed. Following is something I wrote at age nine. I have no idea what it is, but I copy it here exactly:

And terrors dissolve, over and over. Perhaps the core of fear is helplessness: something awful stands in my doorway and I can't do a damn thing about it. A child has to do something about it, and I think writing made me strong, gave me armor. As a little girl, I would acknowledge that scary, jangling world out there and then proceed to surmount it. With a pencil and paper, I could call the shots, I could make justice prevail. Fear may be a secret space where children dwell, but in order to survive, don't all children create an ancillary secret space for mastering that fear? Lord, there are a million scary things out there, all quite real—a child could spend 24 hours a day trembling with that discovery. Or he could find a safe zone, a space where he's got the power. It's like a key clicking in a lock, a silent voice whispering, "This is you. This is your territory. This is how you take command." I found it with writing. Other children build complex Legos, or play basketball or paint or ice skate, tell jokes, play the piano. (And, of course, today there are the inevitable computer games, where God knows it's easy enough to pulverize the bad guys). Ideally, though, a child finds a space where his or her unique gift reigns and empowers: suddenly your head's high, you've found your niche, that thing that makes you the cowboy on his horse, the soldier planting his flag at the top of the hill. The happy secret space is the one where you're in charge.

Today I write for a living. The Scarlet Pimpernel, a musical for which I wrote book and lyrics, opened on Broadway in the Fall of 1997. And, oh yes, TheScarlet Pimpernel has a classic happy ending where good triumphs, the villain is foiled, and the hero and heroine quite literally sail off into the sunset. Am I still then just a child smacking back the danger? Recently I was sent a copy of a letter from the Scarlet Pimpernel website. The letter was from one Pimpernel fan to another, and the last line read, "Remember—the good guy always wins in the end!" Not only am I still insisting on the happy endings, but apparently lots of other adults out there are still needing them. Those secret spaces of childhood never really go away. We just tend to tackle them with a bit more sophistication.

As I write this, I'm in Arizona on a ranch. There is much about this place that is "a secret space." I came here by myself for a week's vacation. I'm about to go into a dining room full of families and couples where I won't know a soul. I ride horses every day. Their hooves stumble on the rocks, and the wranglers warn us how easily a horse can spook and buck. When I lope, it's a challenge to stay in the saddle. I've now heard several anecdotes about the bite of the Black Widow spider, and how you should shake your boots out each morning. Believe me, in the mornings I am shaking out every stitch of clothing I own. I also listen carefully to the snake instructions, "Ya meet a rattlesnake on the path, ya just back up, reeeal slow. . . ." All of this is very very very very scary. And I sit here, looking out on the desert, writing.

Philip Levine

The Simple Truth (Pulitzer Prize, 1995)

Professor of English, New York University

*Alberti died shortly after this commentary was composed—Ed.

Rafael Alberti, for me the greatest living poet,* tells us in his memoir of a secret grove in which he could with perfect ease become the person no one else saw, the amazingly imaginative child we now know as Rafael Alberti. No Jesuit priest ever entered the grove, nor did those pious aunts and uncles who savaged his childhood, nor did his parents or his brothers and sisters, nor even the "real authority figure in those days," the family servant, Paca Moy. He calls it his "lost grove" because when he was fifteen he left it behind forever, along with his dog Centella with whom he had shared those childhood years and those places of refuge. For financial reasons the family was forced to leave the small town of Puerto de Santa Maria at the mouth of "the River of Forgetfulness" overlooking the Gulf of Cadiz and move to a small, dark apartment near the Atocha station in Madrid. When I was thirteen my family also made a dramatic move. We had been living in the center of Detroit—then a city of two million souls, as Alberti would put it; my mother, who had for years harbored the desire to own her own home, seized the opportunity to purchase an inexpensive house on the still undeveloped outskirts of the city. Within a few months I too found a secret grove which soon became the heart of my childhood. It was, of course, not Alberti's grove, and yet in one central way it was, for like his grove it represented peace and gave me the privacy I needed to conduct my secret conversations with the known and unknown worlds and with myself. If I were this moment suddenly transported to Detroit I could lead you to the very spot, but I would not. I am sure the gigantic copper beech that was its exact center is no longer there, nor are the clustered maples and elms, nor is the thick underbrush, the heaped leaves, and the gnarled fallen trunks of dead trees. I'm sure everything has been replaced by a row of small, modest, lower-middle class homes with tended lawns and fenced yards, homes very much like ours. Could a living child find his or her secret heart in what is there now? Perhaps in an attic room or behind the furnace in the basement or in a dry fruit cellar, its windows papered over. Children are both resourceful and driven, and each requires a secret place of contemplation and invention. I tried those places before I found my grove, before it became the site of my first poems and largely the subject of those poems. Although I'm known largely as an urban poet, one obsessed with the cities I've called home—Detroit, Barcelona, New York—in my early poems I addressed the natural world certain that the natural world was waiting to hear me. At thirteen I sang to the listening stars, the unseen wind, the trees that caught the wind and turned it to music, the rain, and especially the rich perfumes of the earth that received the rain. There in the secret heart of childhood—seemingly isolated and lonely—my words commanded the largest and most extraordinary audience they would ever delight: the whole of creation.

William Meezan

Marion Elizabeth Blue Professor of Children and Families, University of Michigan School of Social Work

Outstanding Research Award, Society for Social Work and Research

Most people think of children's secret spaces as safe sanctuaries—places to get away from the stress of childhood. But for some children, being alone in a secluded space is lonely, scary and unsafe. They are gay and lesbian children who are confused and feel isolated. They are children who have been abused or demeaned in other ways by their parents, and have had their sense of self scarred. They are children of color or of unusual heritages who have not been taught pride. Because they have internalized negative images, these children don't like themselves and are therefore denied the ability to enjoy solitude.

I was such a child. Being alone, even for short periods of time, was frightening. Being alone meant living with my demons that told me I didn't belong, that I was less worthy, and that I was damaged. It was not just that I was different—that could be celebrated. It was that I was bad, or at least that's what I thought then. My demons made me agitated and hyperactive, secretive in the presence of adults for fear of being "discovered," hypersensitive, and easily brought to tears when criticized for the most minimal indiscretions. They made me afraid of being alone.

And so, safe places—my secret places during childhood—were public spaces. They were places where demons could not come out, or at least where I could control them. They were places where activities were organized and supervised, environments where group activities were structured, where I could be engaged with others and not with myself—Scouts, summer camp, and Hebrew day school—places where I could fit in, or at least pretend to fit in. Because they provided a sense of normalcy, I remained in the Scouts until the troop dissolved, attended day school until after my Bar Mitzvah, and went to summer camp, in one role or another, until I began graduate school.

High school—a "special" public school in Manhattan called the High School of Music and Art—gave me ways not just to contain the demons but to accept them, which was a first step toward conquering them. I got to go there not because I was a brilliant musician but because I was born with a musical ear. Going to M&A meant I had to leave the Bronx, which opened new geographic, experiential, and interpersonal vistas. My classmates were rich and poor, white and non-white, worldly and sheltered, conservative and radical, troubled and undisturbed, fun and somber. Each was unique, and what bound us together were our various talents and shared interests, not our backgrounds. And, because we were talented, we were respected by our teachers and treated with dignity. We were told we were worthy, and because I began to feel worthy being alone became less frightening.

In high school I also discovered that I could be protected by music, and learned that I could be happy and alone simultaneously. I realized this when, as part of an assignment, I had to listen to the Bach Mass in B minor. When I put it on my phonograph, my parents were appalled—nice Jewish boys didn't listen to church music or for that matter any choral music written in Latin or German. I was told to close the door to my room so the "noise" wouldn't penetrate the house. At that moment, something amazing happened. The great choruses of Bach simultaneously enthralled and protected me. From that day on, when I needed to feel safe, I shut myself away with Bach or Haydn or Handel or Mozart or Beethoven or Wagner—not their symphonies (unless they had choral movements) but their masses and their oratorios, their requiems and their cantatas, and later, their operas. And just to make sure I would be safe, I developed a love of Gregorian chant.

In college I learned to combine my two secret places. The fraternity house, the public space, meant I did not have to be alone when I did not want to be, and music (some of which I now owned) kept people out of my room when I wanted to be alone. I didn't study much, for that meant being alone and vulnerable. But it was here that I decided, very late in my college career (and having almost flunked out), that my calling was to work with troubled children, something that I knew I could be good at because of my various experiences. As I entered Social Work graduate school, learning became meaningful for the first time, for I had no wish to do harm to those I wanted to help. Not surprisingly, I started to do well academically.

My first job after graduate school was in a residential treatment center for emotionally disturbed latency-aged boys. I loved that work until the system got in the way. It all happened around a child named Luis, an eight-year-old who had been abandoned to the streets of New York at the age of six and had managed to live on his own for a year before coming to the treatment center. A charming child, he had survival skills but little educational or emotional resources. His projective tests said he was deeply troubled.

Over the next eighteen months his progress was nothing short of amazing. He endeared himself to a volunteer who applied to become his foster parent. While his discharge at this point may have been slightly premature, I pushed for it fearing he was becoming "institutionalized." The cottage parents were against it because he was not yet "neat" and the psychiatrist speculated that he still needed structure. So, despite what his teacher, the psychologist, the consultant, and I said, they decided that he should stay another year. I knew this was a disastrous decision (I learned after leaving that within five months he had been psychiatrically hospitalized after being physically and sexually brutalized by older children in the institution; Lord knows what happened to him after that), and vowed that I was going to work to change systems that destroyed children like him.

Wounded and battered by an uncaring bureaucracy, and feeling helpless again, I turned to the one place that gave me solace and rewards. Doctoral education allowed me to concentrate on learning what had become my passion—damaged children and what it takes to make them whole. The freedom of doctoral education gave me another truly private, secret space, where I felt complete and competent: a cubicle (now an office) where all of my energies could be devoted to learning and writing about kids and their families and what we need to do to support them.

And so, I have come to consider academic institutions my "secret space." So watch out for college professors wearing maroon and baby-blue sweat shirts, who have spent 21 years partnered to a church musician, walk on campus singing Handel oratorios, and stop to smile at children who don't seem to belong. They may be in a space as private as a tree house or a fort made out of an old cardboard box. And be equally aware of those who write in silence about something they are passionate about, for their offices may hold secrets few people understand.

Valerie Miner

Rumors from the Cauldron: Selected Essays, Reviews, and Reportage

Professor of English, University of Minnesota

1955/New Jersey

She is gone. Off with Lily or Gerry or someone who has a car. Grandma is taking care of us, or we are taking care of her. It's fine. I am eight years old already and I understand.

My brothers watch cartoons. Grandma is cooking. I am playing dress-up in Mom's bedroom. It's really my parents' bedroom, but when Daddy is at sea, it becomes her bedroom. A big, light, airy place at the back of the house, separated by a floor from the upstairs bedrooms. It's not a very private room and I feel easy about entering while she's gone. I do close the door because I'll be changing clothes.

First I try on the hats, those close-fitting, feathered hats. Mom has two—yellow and green. The green looks better with my eyes and skin. Then I put on one of her fancy slips and suddenly I am draped in a luxurious ballgown. These satin and lace slips are so pretty, I wish my mother would wear them out—to the theatre or a night club—but Mom doesn't go out. And in the bottom drawer, that fabric Dad sent from Argentina, as if he forgot she couldn't sew. The bright blue and red and green—same color as the hatis a little scratchy, but it will work handsomely as a shawl. Now a pair of red shoes from the closet.

There, I stand admiring myself in her mirror and seeing—as I look closely—myself reflected a hundred times (although I stop counting after five) in my father's mirror on the taller bureau across the room. This double reflection is dizzying, so I try to ignore it, concentrating on the angle of my hat and a detail in the lace bodice. Closer, I lean into her mirror.

Minutes pass. I must wait for the right moment. Finally, the cameras start rolling. Local stations across the country have tuned in and I modestly introduce myself. Valerie Miner, child star, here to testify to the beauty aid of Ivory Soap. It really is 99 and 44/100 percent pure. So pure it floats.

On Tuesdays I endorse Pond's Cold Cream.

John Hanson Mitchell

Trespassing

The 2000 New England Booksellers' Association Award for a body of work

The place, even at this distance in time, looms as a metaphor, a half-remembered country of ruined estates, with canted terraces, broken balustrades and toppled pillars, and the whole of it overgrown with greeny, twisting vines.

There was once money in the town in which I grew up, but by my time all the old families had grown eccentric and were living out their days on dwindling trust funds. Some became collectors of birds' eggs, some kept donkeys in the old estate carriage houses and quoted Spencerian couplets to them at night. Some were totally undone by the Depression and walked off the cliffs that ran along the west bank of the Hudson River. The land here was in decline, it was a nation of decaying gardens, huge trees, brick walls, horse barns, and carriage houses, which by my time were deserted and accessible by means of broken windows and crooked backdoors and cellars.

High above the town, overlooking the Hudson River, corporate magnates of the nineteen twenties had constructed larger estates, most of which had been torn down or deserted after the Crash. Here you could find the overgrown ruins of formal Italian gardens, collapsed pergolas, fallen pillars, and cracked swimming pools half filled with green waters and golden-eyed frogs who eyed you from the detritus of sodden leaves and then ducked into the obscurity of the depths when you went to grab them.

Here, amidst the ruins, in the six miles of second-growth woods that ran along the cliff there was rich picking for the adventurous youths who lived otherwise normal lives in the lower sections of the town. And to this spot on any given Saturday morning in warm weather, we, the nomadic tribes of our neighborhood, would ascend to fight. We recapitulated history in this mythic landscape. From the battlements of the terrace balconies we defended our land against the attacking hordes of imaginary enemies with sticks and showers of stones and great clods of mud. We fought day-long battles here and only at the requisite hour—sundown—would we give up and return to our boring, albeit safe homes.

There was only one estate in the entire six mile stretch of woodland that had yet to be conquered by nature, let alone by our militant armies. The house was owned by a man we used to call Old King Cole and was a vast brownstone place with spired turrets and a mean-looking iron fence surrounding it, the type of fence with spear-pointed tips. The grounds, which purportedly had been laid out by the firm of Frederick Law Olmstead, were extensive and unmanaged, with two immense copper beech trees framing a briar-strewn entrance, a small orchard just west of the house, a sunken garden with a frog pond, and many species of exotic trees, including, I was later told, a rare Franklinia.

Of all the properties in the community, of all the woodlots, overgrown backyards, gardens, and frog-haunted swimming pools, King Cole's place held the greatest attraction. For one thing there was a deserted carriage house at the back of the grounds to which we had gained access and used as a hide-out. But the other thing is that, unlike other landholders in the community, Old King Cole did not seem to appreciate trespassers, even though his property was at a remove from the other holdings in the town. Periodically, sensing an invasion, Old King Cole would emerge from the darkened interior of his house to reprimand us—a tottering old man with an ebony cane and a palsied hand. We were too fast for him. We always broke through various escape routes we had established and headed for other territory. Once or twice he called the police, but they too were disinclined to leave their vehicles and scramble through the tangle of briar and bittersweet and ivy strewn pillars to catch us.

One afternoon Old King Cole surprised two of us and drove us into a walled corner of his sunken garden. Once we were trapped, he approached us, shuffling, his cane raised ominously above his head, his green eyes burning under his brushsmoke eyebrows. We thought we were done for. We would be thrashed, perhaps murdered, at very least bloodied from the full strike of his cane. But instead the old man halted in front of us, and there, amidst the wild briars and ivies, delivered a resounding lecture on the nature of title.

"My property," he intoned, "My holdings. My kingdom. My nation." Then, advancing a few steps he pointed southwards with his cane to the town below the cliffs. "Your property, your nation. Return to your country. Respect the national boundaries."

It was a good lecture, but it had the wrong effect. Up to that time, I had no concept of the nature of trespass. Forbidden passage consisted of Old King Cole's land, and an even more ominous place in the south of the town called the Baron's that was surrounded with a high stucco wall and reportedly guarded by Great Danes. With King Cole's proclamation, the world, which up to that time had seemed to me a wide collective space that invited exploration, was divided and quartered, and guarded by owners of private property. But on the heels of this revelation there came an epiphany. I understood then the lure of trespass, the freedom of open space, and the sublime possibility inherent in wilderness.

Kathleen Dean Moore

Riverwalking: Reflections on Moving Water

Chair, Department of Philosophy at Oregon State University

Do you remember the sound a mother makes, knocking on the door of a damp cardboard box in the morning? She sticks her finger in the hole that serves as a doorknob and pulls. The cut edge of cardboard sticks to the box, so when she tugs hard, the door pops open all at once, and the box sways. All the squares turn to parallelograms and the window-shutters flap open, swinging out over the crayoned window boxes, the red and purple daisies, the pasted-on picket fence, the twining vines. She reaches in the door and leaves three hard-boiled eggs.

The box has grown weak-kneed and mottled overnight, wicking moisture from the lawn. By the mail slot, smooth paper has begun to curl away from the corrugation. But with morning sun shining through gaps along the front door, the air in the box is warm and smells like new books. My sisters and I sit cross-legged, nightgowns taut across our knees, and eat the eggs for breakfast. We call ourselves The Three Flowers, and this is our clubhouse.

It takes a lot of sawing with a steak knife to make a refrigerator carton into a house. The first cut is the dangerous one, stabbing the blade through the cardboard thickness. But once the knife is embedded in the box, you can saw out a window or a door or an escape hatch or a chimney hole. Then you can color the curtains with crayons and paste pictures on the walls.

We didn't use sleeping bags back in those days. We slept on rugs woven from old fabric—every outgrown dress and stained tablecloth torn into inch-wide strips, then the strips sewn end-to-end and woven into rugs by a neighbor who wore house-slippers all day. If we used blankets, I don't remember them. We probably had no use for blankets during Ohio summer nights, nights so hot that we would lie on our backs, spit in the air, and let the spray settle cool on our faces.

This time, I have my goose-down sleeping bag and a high-tech foam pad. The weather has changed in the fifty years since I was a child; it's the difference between Ohio and Oregon, where a sea-wind slides between the mountains at dusk and the temperature drops twenty degrees. Refrigerator cartons don't seem to have changed though, and after the workers dollied our new refrigerator into place, they left the box unceremoniously by the street for the trash-men, just the way I remember. Back then, we would roll boxes home, end over end over end, sometimes for blocks. Today, I hauled the box up the driveway in my Suburban.

I'm embarrassed to be stabbing a good Sheffield steak knife into this cardboard box, sawing windows and doors, and my husband doesn't even ask. But I know that memories live in specific places, and sometimes you can find the entrance to the past, if you can just find the right place. This has happened to me: I will walk into an opening in a juniper hedge, or onto a landing where a stairway turns toward the attic, and it's as if I had dropped down a dark tunnel that opens into light-flooded childhood memories. So I wonder if this cardboard box will take me back to a particular kind of joy I haven't felt for a long, long time. There's nothing wrong with trying, I tell my husband, but he says, hey, nobody's arguing with you.

He and I share a silent beer, watching the moon speckle the lawn under the Douglas firs, until it's time for bed. Then he gives me a quick hug, and I climb into the box to spend the night alone. In the past, my sisters and I worried about neighborhood boys, skinny scab-kneed buzz-headed boys who lied to their mothers and snuck out barefoot at night to kick the box over and run away snickering. Better to stay awake all night than to have your world convulse and turn on its side, spilling you into the laughing dark. There are no boys to worry about now, but I lie awake anyway, shifting in my sleeping bag, wondering how three little girls ever fit in one box. A car door slams. The neighbor's clothes-dryer shuffles and clinks. I hear a slurry whistle from the barn owl that nests in the cedars at the end of the street. Then the neighborhood grows quiet.

I wake up suddenly in darkness so engulfing I don't know if my eyes are open or shut. When I raise a hand to touch my eyes, my fingers collide with the top of the box, only a few inches from my face. The lid is soft and sagging. I reach out for my husband, but my hands touch cold walls instead. Why am I alone? The air is dank, damper than a cardboard box should be on its first night in the backyard. I can't hear anything at all. And never have I felt such darkness—not just the absence of light, but a darkness thick and real and smelling of turned earth.

If this box is a tunnel through time, it's taking me in altogether the wrong direction. In one movement, I lift both legs and batter them through the door, roll onto my knees, and crawl out of the sleeping bag and the box. Climbing to my feet, I kick the box until it collapses on one side and sinks flat on the lawn. Suddenly out of breath, I find myself standing in the backyard, in a long nightgown, in darkly falling rain. The rain has plastered oak leaves against the white siding of the house and knocked the last petals from the wind anemones, scattering them across the grass. As I walk into the porch light, petals stick to my feet.

Robin C. Moore

Childhood's Domain: Play and Place in Child Development

Professor of Landscape Architecture, North Carolina State University

What is going on when a small child fondles the fringe on the edge of a rug? What is happening when a tiny hand pulls a blade of grass from a shadowy lawn? Would the life of the child be different if the rug had no fringe, if the lawn were replaced by asphalt?The natural world offers a special place for children to discover themselves, to learn to distinguish "me" from "not me." I grew up on the edge of a small town south of London's greenbelt. From an early age we roamed freely, except when Battle of Britain dogfights raged overhead.

A track made long ago by wheeled vehicles ran along one side of the bracken places in Britains Woods. Just off the track grew a sweet chestnut tree, medium age with branches close to the ground, great for climbing. A stand of foxgloves in late spring thrust pink, chest-high columns through the bracken. The fresh flowerlets open sequentially as the top of the column continues to grow. We used to pick flowerlets, examine their delicate interior markings, sucking the ends to taste nectar, gently holding them between pursed lips, pretending they were fairy trumpets. Note: this plant now routinely appears on lists of "toxic" or "poisonous plants" because of the heart-stimulating chemistry of digitalis. Maybe if we had boiled pounds of the plant to drink, some harm would have resulted. Fortunately there were no adults around to intervene and no paranoia about child safety and this "potentially" hazardous plant. I live as proof, along with surely thousands of kids, that this potential has not been realized!

"Secret" is the special meaning children give to a place when they possess it deeply. Possession, which persists like love in long-term memory, comes from the hands—from interaction or a kind of making, or the creaturely ways animals define territorial boundaries. Nature is really the only medium that allows repeatable rewriting or remarking by the same children over time as they elaborate the place-relationship. Such informal, natural spaces are rapidly disappearing by the blade and under the rationally directed bulldozers of our technologically driven political economy. "We have to teach people to be more flexible," the radio commentator suggests, "in order to be able to change careers and jobs as globalization grows." But can you teach flexibility? Play gives a child a sense of a natural relationship that has no particular limits.

For a group of children playing together, nature is a unique medium that can be continuously and instantaneously used for an infinite range of expression. We must have been around thirteen when we started to spend most of our free time in the small wood next to Hugh's house. There Hugh and I found an old electric motor which we took back to his Dad's garage workbench, hooked it up to a main power supply, and got it to work—a secret fragment of a secret place. Our visits to the wood then led to imagining other ways it could be used. We needed a place to ride our bikes. No longer satisfied with racing around and around the landscaped island at the bottom of Croft Way, we wanted a more challenging track. Over several weeks we built with pickaxe and shovel a ride twisting and turning around the trees in a circular loop 100 feet across.

One day we had the idea of building an underground "camp," the final adventure of our neighborhood childhood. We had the tools to dig the hole, and our ambition was limitless. One of us brought a bow saw from home to cut down a tall slender tree, which we cut into logs to span the hole as a roof. With four or five of us sharing a saw that had not been sharpened in years, it took many hours of very hard work. I can't recall if there was an image or story that motivated our energy. I think it was just the idea of living underground—secretly.

All the camp lacked was heat. Hence, the "stove adventure." Our plan was to move one of the cast-iron wood-burning stoves from an abandoned row of Nissen huts, where barrage balloon crews had been billeted during the war, two miles to our camp in the woods. The stove must have weighed at least 100 pounds. How to move it? About that time, I had constructed a wooden cart with two old bicycle wheels that could be towed behind my bicycle. Unhitched, it became the stove transport: somehow we managed to trundle uphill and down, yard by yard, on the public roads between the RAF camp and our underground hideaway. The last thirty yards we had to drag the stove through the woods to its final location. We lowered it into place with a rope, added a length of metal stovepipe, completed the roof around it and lit it up. It worked! Soon our earthy abode was deliciously warm and comfortable. I still recall sitting on "benches" fashioned out of the solid earth around the base of the excavations, the mixed aroma of freshly exposed dirt and woodsmoke in the air.