The Camera of Sally Mann and the Spaces of Childhood

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

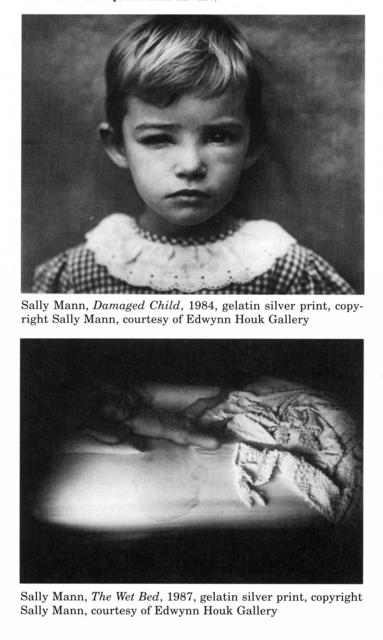

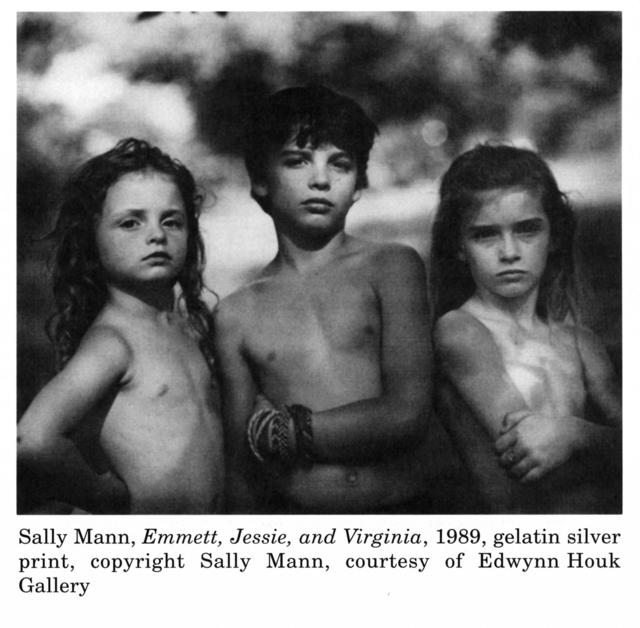

While photographer Sally Mann's work covers a wide range of territory, including exquisite and nostalgic landscape photographs taken with a large format nineteenth-century view camera, it is her black-and-white photographs of children—most frequently her own children—that have struck a vein. First exhibited collectively in the exhibition "Immediate Family" that opened at the Houk Friedman Gallery in New York in 1992, these photographs chronicle the growing up of the Mann children, including wet beds, insect bites, nap times, rural escapades, playacting at adulthood and what the New York Times writer Richard Woodward has called "their innocent savagery."[1] Most notably the Mann children are commonly photographed nude, in rural idylls and in their beds. While the series found almost immediate commercial success, not all of the scrutiny the photographs have received has been positive; even the most liberal art periodicals in the 1990s have often refused to publish unedited photographs of the nude Mann children. Other photographs, notably one entitled DamagedChild of her daughter Jessie with a swollen eye that was the result of an insect bite but somehow suggests battering, or another called Flour Paste in which Jessie's legs appear to have been burned (but were not), have led some critics to make accusations of child abuse or of improper intent surrounding the photographs. The San Diego Tribune, for example, ran a headline asking, "It May Be Art, But What About the Kids?"[2]

The photographs are pointedly attached to place, and specifically to the area in and around Lexington, Virginia, where the Mann children have grown up. As Mann herself has said, "Even though I take pictures of my children, they're still about here. It exerts a hold on me that I can't define."[5] The photographs are particularly idyllic for capturing the children in the sticky, moisture-laden world of Virginia in summer, a byproduct of the fact that Mann has traditionally photographed only in the summer, devoting the rest of the year to printing the photographs herself. Mann's photographs are also rooted in her past, for she was herself photographed nude by her father, Robert Munger, a Lexington doctor and amateur photographer. Mann has commented, "I don't remember the things that other people remember from their childhood. Sometimes I think the only memories I have are those that I've created around photographs of me as a child. Maybe I'm creating my own life. I distrust any memories I do have. They may be fictions, too."[6] Mann's own work, including that of children, is frequently tinged with a sense of nostalgia, hints of a separate world of childhood that is long distant and beyond retrieving. Of Mann's more recent return to landscape photography, taken in Mississippi, Georgia, and Virginia, she has written that Southerners "embrace the Proustian concept that the only true paradise is a lost paradise"[7]—a comment that certainly characterizes much of Mann's photography, including the images of her children, who are now, in 2000, no longer children. In all of Mann's work, such effects of nostalgia and ambiguity are often achieved or at least enhanced by light effects, using light as the great Victorian photographers such as Julia Margaret Cameron did to draw our attention to several points at once. The nuances of light—where the slightest shift can turn a sky from promising to threatening—further play on issues of memory, so that the images of children at play look like the dreamlike recall of subjects looking back toward an earlier time.

Most of the photographs of Mann's own children were taken on a 400-acre farm that Mann owns with her brothers, deep in the woods and miles from electricity. Mann cites this setting as evidence that she has merely captured the "Edenic" quality of her children's lives. Indeed, she describes the work of Immediate Family as "the story of three remarkably sentient children, very aware and—immodestly—very beautiful children, who have a pretty good life—a very free, very open, very natural life. At least certainly in the summer; the rest of the time they get up and go to school like every other kid. Make their bed, get bad grades, get their allowance. But in the summer they're allowed a measure of freedom that I don't think very many children enjoy."[8]

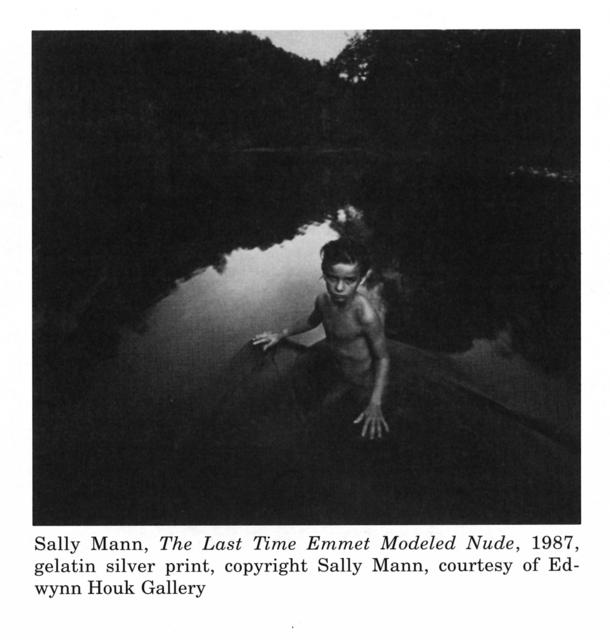

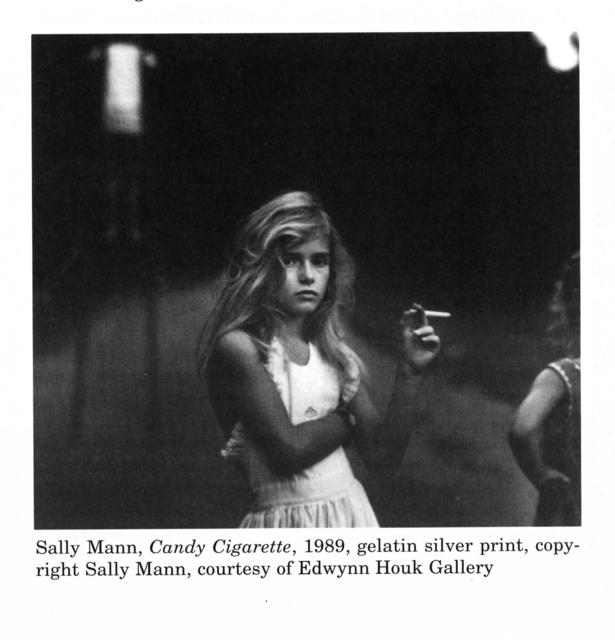

Mann began photographing her children not long after she began to have children in 1979, with three children coming in five years and thus limiting her ability to work in distant landscape settings. Photographing her own children thus became a part of her active parenting. The family portraits themselves began in 1984 with the photograph Damaged Child, showing Jessie with her face swollen from insect bites, an image that in Mann's words "made me aware of the potential right under my nose."[9] From the beginning, the works have combined factual observation and contrived fiction, nature and artifice, putting her in the camp of postmodernist photographers such as Cindy Sherman. Mann admits to the artifice in some photographs; in Jessie Bites (1985), the sets of tooth marks on the arm of the adult were made by Mann herself, long after those made by her daughter had faded, while Jessie's face still conveys a sense of anger that seems to authenticate the image. In Popsicle Drips (1985), the artifice is art historical, clearly referencing Edward Weston's photograph of his son's prepubescent torso (Neil, 1925), but updating Weston's detached formalism with actual childhood in the form of dark popsicle drips on Emmet's groin.[10] Moreover, the image demands examination: what is this liquid that outlines the boy's penis? Is he wounded? Some images are ambiguous on the point of artifice: in The Wet Bed, for example, it is not clear whether the young Virginia is asleep or posing, coloring our view of the circles of urine that stain the sheet around her. Many observers of Mann's work feel manipulated by this sense of artifice, yet Mann argues for its use, stating that "You learn something about yourself and your own fears. Everyone surely has all those fears that I have for my children."[11] And again she connects this to her own intent in the work: " . . . the more I look at the life of the children, the more enigmatic and fraught with danger and loss their lives become. That's what taking any picture is about. At some point, you just weigh the risks."[12] Mann argues that such ambiguity has a further purpose in attempting to broaden the resonance of the images, avoiding specificity of location or of class signifiers in favor of more metaphorical meanings. The images are thus not about the "things" of childhood but about, in Mann's words, "the idea of being a child and a family member, the complexity of it."[13]

Mann's photographs of her own children are not the only images in her body of work to elicit concerns about the sexuality of children or their sexualized representation—even though Mann objects that "childhood sexuality is an oxymoron."[14] Certainly the popularity of Mann's work from the late 1980s and 1990s rests in part on her transgression of taboos concerning the nudity of young children. Her series published in book form in 1988 as At Twelve examined the world of young girls in and around Lexington, capturing the sense of confused tension in their eyes and bodies as they pass from the state of girlhood into that of womanhood. Even as these images suggest the burgeoning of adolescent sexuality, they also imply for some viewers the more forbidden topics of incest and child abuse. For Anne Bernays, "The photographs seem to out-Freud Freud in acknowledging the pervasiveness of childhood sexuality."[15] Bernays argues that the sexuality in these photographs is allowed to operate freely while also being manipulated (even exploited) by the artist. Yet Bernays also suggests—wrongly, I think—that the point of the photographs is to deny the reality of childhood innocence as a sham. This innocence is still present in Mann's work—sometimes oddly accentuated by a sense of unknowing knowingness of the sitters—but it is a more complex issue than has been incorporated into the notion of the "Romantic" child. For these photographs and for Immediate Family, Mann has been attacked for approaching the world of child abuse—however unintentionally—with the eye of an aesthete, without imposing a political view. As Anne Higonnet writes, "precisely because everyone agrees that Mann is a superb technician and formalist, her photographs have been perceived as estheticizations and eroticizations of violence against children."[16] Mann even plays with the possibility of death, and was for years moved by a picture she took of Virginia with a black eye because "you couldn't tell if she was living or dead. It looked like one of those Victorian post-mortem photographs."[17] Even after Emmet was struck by a car and thrown fifty feet in 1987, Mann couldn't resist such ambiguous and, at least for many viewers, troubling images: Immediate Family contains a picture of a nude Virginia in which she appears to have hanged herself by a rope from a tree. Bernays sees these images, which she compares to corpses, as the "conscious imitation of nineteenth-century photographs taken of dead children for grieving parents just before the coffins were closed, as mementos of the departed."[18] Often it is the viewer who brings misreadings to the images, colored by a larger societal paranoia about our conduct toward our children. In Last Light (1990), for example, the man's fingers rest gently on the side of the child's neck, perhaps gently testing her pulse and reminding us (like the watchband on the man's wrist) of the fragility of life, of the preciousness of all children, especially such an achingly beautiful one. Yet how often in my own experience have viewers remembered this as a threatening image of strangulation?[19]

Anne Bernays has pointed to what is perhaps the most telling issue in Mann's photographs of her children: "the pictures' very power works against them by implying a moral connection between the models and their parent. This connection is as false as it is seductive."[25] The false seductiveness of the images is in the viewer's too frequent desire to confuse the artist and the art, when we need to remind ourselves that fundamentally all art is fiction. Even a photograph never says anything unequivocally, even when it most appears to do so. Certainly it can be argued that the most shocking aspect of Mann's photographs of children is the possibility of our own sexual response to them; we see these beautiful children, feel desire, and immediately repress it. Mann's art plays on this tension, between the extremes of childhood and sexuality or childhood and death, and keeps them in extraordinarily skillful balance. This balance and tension in Mann's art seeks to suggest that childhood is a more complicated state than our society has historically accepted. The photographs point to spaces of childhood that are anything but innocent and that many viewers would prefer not to see or talk about—and yet we talk about abuse and molestation almost obsessively, as if these were the only sensory experiences available to children. Mann's images do not corrupt childhood innocence, for it is there as well. But there is something more going on, beyond the romping of sprites in Edenic fields that is gentle and vertiginous and frightening all at once. These children are knowing and wounded as well; childhood is seen both from within and without. Mann's work suggests that a redefinition of the worlds of childhood and adulthood, and the artificial lines drawn between them, is in order, that the much-discussed crisis of the American family is among other things a crisis of representation. And surely all of this is what Mann had in mind. The epigraph for her book At Twelve is taken from Anne Frank, age 12: "Who would ever think that so much can go on in the soul of a young girl?"

NOTES

1. Richard Woodward in The New York Times, September 27, 1992, Section 6, 29.

2. For a useful summary of critical responses to Mann's work, see Janet Malcolm, "The Family of Mann," in The New York Review of Books, February 3, 1994. For a larger and richly informed discussion of the problematics of contemporary visual representations of childhood, see Anne Higonnet, Pictures of Innocence: The Historyand Crisis of Ideal Childhood (London: Thames & Hudson, 1998).

3. Vince Aletti, "Child World," in The Village Voice, May 26, 1992, Vol. 37, No. 21, 106.

4. For a useful summary of the Christian Right's crusade against "child pornography" in the visual arts, see Richard Goldstein, "The Eye of the Beholder," in The Village Voice, March 10, 1998, Vol. 43, No. 10, 31-6.

5. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

6. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

7. Quoted in Carol Squiers, "Sally Mann," in American Photo, March/April 1998, Vol. 9, No. 2, 70.

8. Quoted in Aletti, op. cit., 106.

9. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

10. For a full discussion of Mann's debt to Weston, and to other photographers of children such as Julia Margaret Cameron and Dorothea Lange, see Shannah Ehrhart, "Sally Mann's Looking-Glass House," in Tracing Cultures: Art History, Criticism, CriticalFiction (New York: Whitney Museum of American Art, 1994), 52-69.

11. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

12. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

13. Quoted in Aletti, op. cit., 106.

14. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

15. Anne Bernays, "Art and the Morality of the Artist," in The Chronicle of HigherEducation, January 20, 1993, Vol. 39, No. 20, B2.

17. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

18. Bernays, The Chronicle of Higher Education, op. cit., B2.

19. Higonnet notes the same propensity of viewers to misread this image, op. cit., 202.

20. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

21. Quoted in Aletti, op. cit., 106.

22. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

23. Luc Santé in Katalog, December 1995, 54.

24. Quoted in Woodward, op. cit.

25. Bernays, in The Chronicle of Higher Education, op. cit., B2.