Like a Fable, Not a Pretty Picture: Holocaust Representation in Robert Benigni and Anita Lobel

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Why, more than fifty years after the end of the Second World War, are we so fascinated with narratives (memoir, fiction, film) that explore questions of Holocaust survival with child protagonists who are far younger than the adolescent survivors (Elie Wiesel's Night) and adolescent victims (Anne Frank, The Diary of a Young Girl) whose narratives published closer to the war have become canonical Holocaust texts? Why are we increasingly drawn to stories about much younger survivors even as our historical knowledge about the unlikelihood of such survival makes such narratives less credible? The context for my questions lies in statistics cited by Debórah Dwork's Children With a Star:Jewish Youth in Nazi Europe, statistics that tell just how rare young child survival was. Dwork relies on the figures in Jacques Bloch's 1946 report to the Geneva Council of the International Save the Children Union: of the 1.6 million European Jews under age sixteen in 1939, only 175,000 survived. This survival rate of just under 11% is a generalized rate for all the countries that were invaded by the Nazis; thus in some countries the survival rate was much higher, but in others, much lower. Dwork, for example, refers to a study by Lucjan Dobroszycki that concludes that of the close to one million Polish Jewish children age fourteen and under in 1939, approximately 5000 survived, i.e., only .5%.

In her introduction, Dwork argues that the reluctance of historians to examine child life under the Nazis is partly derived from the different way we respond to the murder of children: "Our unwillingness to accept the murder of children is emotionally different from our incomprehension of the genocide of adults." Dwork then positions her research as central to an understanding of the Holocaust. She insists that it is only by confronting the persecution and murder of children that we will be driven to ask the "right" questions about the Holocaust, questions that do not blame the victim and reveal their unfairness as soon as we apply them to infants and young children.[1] Perhaps our increasing fascination with the narratives of young children surviving demonstrates not only a reluctance to ask the "right" questions, but evidence of a deeper resistance. For we seem unable to confront the murder of young children except by celebrating the exceptional—and the more we know, even more incredible—narratives of very young children surviving not just the European scene of war, but the death and slave labor camps. Again, Dwork's analysis illustrates how our desire for such exceptional narratives conflicts with our awareness that nearly all the "children" who were likely to survive were either adolescents or children pretending to be so. Dwork points out that children who survived the initial selection at Auschwitz were in effect no longer children; they were passing as adults: "There were no young children and there was no child life." For such children, death was a matter of time, but through luck, most often just the temporal accident of when the camps were liberated, some of those adult-like children did survive. Dwork cites figures we need to keep in mind: "180 children under the age of fourteen were found alive at the liberation of Auschwitz, about 500 in Bergen-Belsen, 500 in Ravensbrück and 1,000 in Buchenwald."

If so few survived, and if we remember that at least some of these survivors were barely alive at liberation and died soon after, and many of them have died since, is this sufficient to account for our current fascination with the exceptional young child survivor? And are we more willing to listen now not just because there are so few of these child survivors left, but because those few survivors are now elderly? Do we in effect trust and tolerate their voices because they are no longer children, because their postwar survival and lengthy lives provide the safety of distance as well as the authority granted their present age?[2] Or does our eagerness now to imagine such next-to-impossible stories simply reflect the shift to a culture intrigued by narratives of childhood trauma and more accepting of childhood memory, more willing to believe in what children say? In acknowledging how unusual her focus on child survivors is in mainstream Holocaust history, Dwork notes specific cultural reasons for ignoring child survivors immediately after the war, when many people, traumatized by what they learned had occurred in the camps, preferred to forget events that seemed unbelievable, particularly when the survivor was a child. If Holocaust narratives told by adults made us uncomfortable and incredulous, narratives told by children were even more disturbing and unbearable. It was hard to believe that young children could survive, let alone want or be able to narrate their stories. Narratives of young children hidden outside the camps, or fictional accounts that began once the young child was outside the camp (e.g., the excessively vague I Am David) seemed barely tolerable. Thus for many years, child survivors of the camps who were compelled to narrate seemingly impossible stories were heard mainly by medical professionals interested in the psychological makeup of children who survive extreme situations; the general North American public remained indifferent, content if they thought about Holocaust survivors at all to imagine such survivors only as broken-down adults.

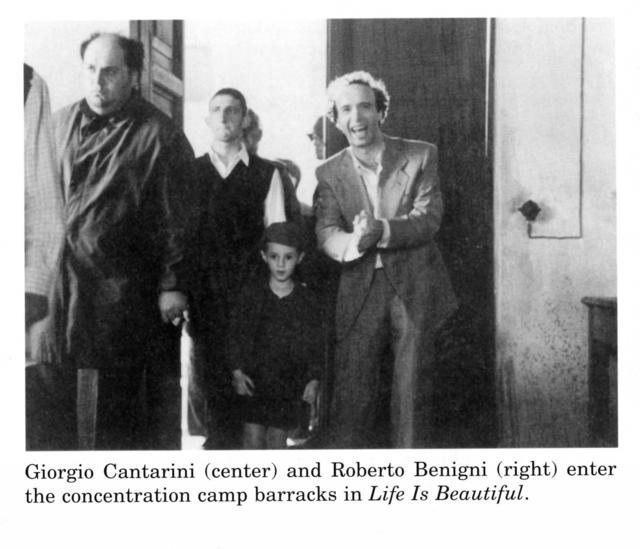

Three recent and very different works speak to our increasing desire for child survivor narratives that resist Dwork's analysis. Both Roberto Benigni's Life is Beautiful (1997), a film about a father's determination to protect his four-year-old son, Giosuè, in a concentration camp, and Binjamin Wilkomirski's Fragments:Memories of a Wartime Childhood (1995, English translation 1996), a memoir about a toddler's amazing survival in a series of camps, have received numerous international awards; Anita Lobel's No Pretty Pictures:A Child of War (1998) made the New York Times Notable Book List and has already appeared on recommended children's booklists, a predictable development given her established reputation as a children's book illustrator. Benigni and Wilkomirski have created works that are highly contentious: Benigni because of his audacious willingness to apply comedy to the Holocaust, Wilkomirski because of an article published in Die Weltwoche in late August 1998 by a Swiss journalist, Daniel Ganzfried, who alleges that Wilkomirski is an imposter, and his memoir of Holocaust survival, a complete fabrication.[3] Such controversies indicate not only how the Holocaust continues to be for many the defining trauma of the twentieth century, but also how problematic we still find the question of aesthetic response to historical atrocity, particularly as such atrocity affects young children. So long as we believe in its status as memoir, we are willing to accept that Fragments tells an amazing truth; as soon as we regard it as fiction, our response changes as we question fiction's right to construct such an unbelievable story.[4] Similarly the very title of Lobel's memoir, No Pretty Pictures, confirms her determination to separate her Holocaust memories from the aesthetic work of her adult life. Whether such separation is possible, Lobel's determination accords with our own desire to protect the child viewer, to construct her as the one who does not know.

But maybe it is adults who do not want to know what some children already know. Although I hesitate to speak about Life is Beautiful, so excessive and misplaced is the outrage that I have heard since its appearance—it is genocide that should provoke our outrage surely, not the aesthetic question of the limitations of comedy—the outrage cannot be divorced from this question of the viewer's knowledge. Is the film's viewer constructed as a child, the one who does not know, and therefore believes that what she sees on screen is the historically real, or is the viewer constructed as the adult, the one who already in some sense knows, and can therefore imagine what is not shown? My analysis tends to presume the latter; opponents of the film, I would argue, assume the former. I think that the tension in the film, and over the film, relates to the ambiguity of Benigni's response,[5] and the refusal by critics to even acknowledge the possibilities of a children's literature on the Holocaust, and what such a literature might tell us about aesthetic response to atrocity and the related question of the child's knowledge.

Even though Benigni has himself suggested that one significant impulse behind Life is Beautiful is the childhood memory of his father magically transforming war experience into reassuring and comic narrative for his children, reviewers of the film have chosen to disregard both the perspective offered by this particular anecdote and the insights offered if the film is situated in the context of the representational strategies familiar in children's literature. Yet such contexts offer a different way of understanding the limitations and strengths of Benigni's film, i.e., that it makes a difference to our understanding of how the film works if we situate it not beside Schindler's List, but in the context of the representational strategies that it openly asserts that it is using. In this context, I similarly set aside the claim that Benigni adapts his title, Life is Beautiful, from Trotsky's words just before he was murdered, for I find a different lineage far more provocative and useful. It is one in which the title rewrites a statement that appears in the final chapter of Primo Levi's memoir, Survival in Auschwitz:The Nazi Assault on Humanity, a memoir published initially in Italian with the far less hopeful title of Se questo è un uomo. In Levi's final chapter, "The Story of Ten Days," Levi describes how, ill with scarlet fever, left behind when the Nazis evacuate Auschwitz in January 1945, he and all the others who have been abandoned to die reach a stage where, despite the armies battling nearby, they are "too tired to be really worried." In this state of exhaustion, Levi makes a surprising statement: "I was thinking that life was beautiful and would be beautiful again, and that it would really be a pity to let ourselves be overcome now." The contrast between Levi's careful use of tenses, "life was beautiful and would be beautiful again," a use that excludes the possibility of beauty in the present time and in the Auschwitz location, and Benigni's insistence on the present tense points to how the practice of a children's literature on the Holocaust is deeply implicated in what is most controversial in the film. Although the second half of Benigni's film ironically repeats incidents from the first half as though to demonstrate how insane and desperate is Guido's attempt to persuade Giosuè that life remains the same even when they are in the camp, Benigni's title insists that the passage of time cannot alter eternal truths. The child who becomes the grown-up narrator of the film may possess a deeper understanding of how his father protected him, but it is one in which the essential loving and trusting relationship to the father remains the same. As in a children's folktale, life is beautiful.

The film thus carefully situates its perspective with the opening voiceover spoken by the grown-up Giosuè in which he twice compares his "simple story,"[6] to a fable. At the film's end, still believing in his father's story that the point of their incarceration is to obey the rules, play the game, and win a prize, Giosuè greets the arrival of the American liberators as the evidence that he has indeed won the promised tank. Giosuè's ride in the tank is interrupted by a reunion with his mother, Dora, and immediately afterwards the adult Giosuè in a voiceover provides the fable's requisite and apparently unambiguous lesson, "This is my story. This is the sacrifice my father made for me." This structural dependence on a fable, with its promise of a lesson, like the film's parodic reliance on folk tale elements, games, and riddles, suggests that much of the success of the film (and its controversy) lies in applying to the Holocaust strategies of representation familiar in children's literature but more problematic in adult Holocaust narratives, particularly films, where we assume that documentary realism alone is appropriate to the subject.[7]

It is striking how similar the film's strategies are to those found in Jane Yolen's young adult novel Briar Rose: "I know of no woman who escaped from Chelmno alive," Yolen writes after completing a fairy tale novel in which she imagines one such survivor. As in a fairy tale, Dora, the heroine of Life is Beautiful, lies in bed like Sleeping Beauty, longing to be rescued by her hero, the man who introduces himself as Prince Guido, and whose last name, Orefice, means goldsmith. Of course, parody demands that this prince does not climb up the tower, but meets his principessa when she falls out of a barn silo into his arms. Nevertheless, Guido clearly does rescue Dora from the miseries of a wealthy marriage, as they ride away from the engagement banquet on the horse appropriately named Robin Hood.

What Yolen accomplishes through the contrast produced by her concluding "Author's Note," Benigni achieves through the visualizing of absence, what the screen does and does not show us. The tension of the film lies in its playing between two registers that always threaten to collapse: a children's fable of rescue; an adult narrative of what cannot be said (at one point a character even says that silence is the greatest cry). Certainly existence in the death camps is governed by rules as ludicrous and insane as those involved in the game Guido invents to protect Giosuè from knowledge of the camps, but when Guido tells Giosuè that Schwanz, the other child seen earlier hiding in the sentry box, has been "eliminated," for a second we are not sure which game is being played. Similarly Giosuè tells his father about the other children whose absence no comedy can hide: they took the children to the showers he says; they make buttons and soap from us. Guido mocks his son's gullibility; what kind of game is that? Who can imagine burning people in ovens? But not even Guido, the one who can answer nearly all of the Nazi doctor's riddles (including one about Snow White), can answer the riddle of Nazi categories, the riddle whose answer we know as the Final Solution. Cautioned by his uncle to heed the warning when Robin Hood is painted with anti-Semitic symbols, Guido jokes that he didn't even know that the horse was Jewish. Like many Italian Jews, Guido is unwilling to imagine himself as vulnerable, and jokes that the worst the Nazis can do is paint him yellow and white.[8] Guido's words are echoed in the unanswered and ultimate riddle that later torments the Nazi doctor and prevents him, a believer in the Final Solution, from seeing Guido as human. The riddle describes something that looks and acts like a duck. If it looks like a duck, maybe it is a duck, but if the riddle's answer is Guido, then the doctor's loyalty to a Nazi ideology that sees Jews as inhuman vermin in need of extermination, prevents him from recognizing the man in front of him. For if many riddles are based on faulty categories,[9] the Nazi desire for a Final Solution demonstrates not only the horrific consequences of riddles based on faulty categories, but also how genocide can be regarded as merely the solution to a challenging riddle. Yet the film has little interest in philosophical analysis. Guido may think himself indebted to Schopenhauer for his belief in will power, but when Guido desperately turns to that will power as a magic spell to prevent the SS dog from discovering his son's hiding place, few adult viewers are likely to forget the Nazi fondness for the rhetoric of will power (a rhetoric inscribed in the title of Leni Riefenstahl's 1936 film, The Triumph of the Will), or to accept that Giosuè's subsequent survival is proof of Schopenhauer's theories.

Presumably it is Giosuè's adult voice that makes Life is Beautiful an adult film. Yet it is worth observing both the abruptness of the film's happy ending and its dependence on an adult voice that is remarkably faithful to the presumed perspective of childhood. Although it is the adult Giosuè who narrates the film, his adult perspective at the film's conclusion is perfectly consistent with the fable that structures his childhood memories, "This is my story. This is the sacrifice my father made for me." Yet this insistence on an unproblematic, coherent narrative is only possible if the film concludes at the moment of liberation, the moment when the fable proves to be both true and impossible to continue. For if the fable is true, and the father saved his life, how does a child live with that knowledge? And does Giosuè really survive because of the father's sacrifice? What then is the sacrifice: Guido's silence about the genocidal purpose of the camps, or Guido's death? Accounting for his survival through the father's sacrificial death seems appropriate to a fairy tale, yet it contradicts the evidence of the film, for it is just as likely that Giosuè might have died because of his ignorance of the camps' purpose, and just as likely that Guido might have survived if he hadn't searched for Dora that final night. The logic that the father sacrificed himself in order that his son might live does not fit the camp universe where if any logic applies, it is the logic of death by which any Jews saved for work have only been given a temporary reprieve. And any logic, let alone the patterns of fairy-tale justice and the good luck of being the special child of the prince and princess, always comes up against the role of accident: the accident that the next morning the camp is liberated; the accident that Dora survives; the accident that riding on the American tank, Giosuè finds his mother. The adult Giosuè's belief in his simple story that begins with his first words as a child, "I lost my tank," and ends with his cry of victory at the film's conclusion, "We won, we won," means that the film must end when it does. It cannot afford to proceed further without confuting its own logic.

A "simple story," Life is Beautiful demonstrates that in speaking of the Holocaust it is not just children who long for consolatory fairy tales. Yet the film also illustrates how questions of intended audience in Holocaust representation often blur the distinction we draw between child and adult. For the controversy over the appropriateness of telling a fable about the Holocaust seems directly consequent to a binary view of Holocaust representation in which adult representation of the Holocaust, precisely because it is adult, is to be judged only in terms of a kind of full (meaning realistic) representation. In contrast, we expect Holocaust representation in children's literature to work with limits, by employing narrative structures that protect the child reader even as the narrative instructs that reader about the Holocaust and attempts to make meaning of what is too easily dismissed as incomprehensible. While some might object that these very limits make the idea of any children's literature on the Holocaust itself incomprehensible and trivial, children's books may simply be more honest about their limitations than adult works. For the objection to limits of representation in children's books implies that there may be another kind of literature, i.e., adult literature, that is somehow free of such limits, and can therefore provide the reader with a full knowledge. Such belief in an ideal literature on the Holocaust necessitates setting aside general theoretical objections to the ability of any language to mirror any reality, objections that are further complicated by the oft-cited survivor perspective that whoever was not there cannot know what it was like, that there may well be words to represent this reality but only survivors speaking to other survivors can possess and understand them. And this survivor perspective has been taken even further, by Primo Levi, when he says that those who survived by virtue of their survival, are themselves an exception and cannot tell the stories of the majority who did not survive.

What is even more apparent is that if Life is Beautiful is ultimately and paradoxically an adult film that is dependent upon the techniques of children's literature, it is also a film whose foregrounding of Guido's need to protect the child distracts us from its equally urgent need to protect the adult viewer who wants to believe not only that the power of parental love will persist even in the death camps,[11] but more wistfully, that the child survivor recognizes and remains ever grateful to the memory of that love. Those who object to the film's comic approach are understandably reluctant to address this as central to the film's comic vision, and I do not wish to generalize that all child survivors are not eternally grateful. Certainly memoirs by children whose parents were murdered are intensely loyal, guilt-ridden at any lapse in that loyalty, as in Night when Elie Wiesel confesses his relief at his father's death. But if the parents survive, the postwar relationship described in the memoirs is often far more troubled, and particularly so if the child survivor was very young.[12]

Guido must die therefore, not to save his son, but to save his son's fabulous memory of him, and the audience's belief in the integrity of parent-child relationships under all circumstances. Listen to the collapse of this belief in No Pretty Pictures as Lobel recalls her feelings regarding her uncle and aunt the night in January 1945 when she and her young brother arrive in "yet another concentration camp": "They didn't matter to me anymore. First they had pretended to take care of us. And then they had lied. They had tried to trick us. The failures of the grown-ups around us had landed us in this place." Lobel will later learn that her uncle and aunt do die before the end of the war, but that night, having lost trust in all adults, she has just refused their well-intended advice to escape during a forced march from Plaszów to Auschwitz. Lobel's "Epilogue" even considers, then dismisses, the question of how her lack of trust may have contributed to her uncle and aunt's death.[13] That Lobel's parents not only survive (the father in Russia, the mother in hiding) but also avoid imprisonment in a camp, makes her memoir far more complex than Benigni's film in its analysis of child-adult relations in the Holocaust and the possibility of happy endings.

For the contrast between Lobel's memoir and Benigni's film lies not in Giosuè's amazing survival, but in the filmic depiction of that survival as the narrative's redemptive ending. Lobel rejects the neatness of Benigni's happy ending, even as she insists in the voice of the American citizen/illustrator/grandmother who writes the memoir that, "My life has been good." The audacity of Guido's hiding Giosuè in the camp barracks seems more credible to those familiar with Lobel's account, which is just as astonishing as Giosuè's, for she and her brother do not have a parent protecting them in the camps even if Lobel does learn years later that the likely reason she was not killed upon arrival in Plaszów was because her uncle pleaded successfully with the Nazi commandant who still needed his services. But no special pleading explains Lobel's survival in the women's camp, Ravensbrück, for several months, when no one cared that a ten-year-old girl was accompanied by an eight-year-old brother, a brother no longer disguised as a girl.

Unlike the triumphant ending of Life is Beautiful, therefore, Lobel's liberation from Ravensbrück is a complex moment that represents only one part of her story and one which she misunderstands, not knowing either who her rescuers are or where she is going. Initially "walking in a halo of light," she feels that a miracle has occurred, a miracle she attributes to her wearing of the "holy medals" that her Catholic nanny had given her and that she has managed to retain despite the stripping and shaving that she has been subject to. Yet she also feels shame at being photographed as she steps off the ferry in Sweden wearing the "same layers of rags" that she wore in the camp. Sweden represents a new world; the rags she wears belong to a different world. As a memoirist, Lobel places this photograph of arrival in Sweden on the cover of her book, as if writing the memoir demands confronting that shame, and all the other moments of bodily humiliation that are part of her experience. A reluctant memoirist, Lobel views with suspicion the current fashion for celebrating Holocaust survivors: "it is . . . wearisome as well as dangerous to cloak and sanctify oneself with the pride of victimhood."

In an era so fascinated with trauma narratives, in which we look for stories about younger and younger victims, Lobel is ambivalent about her own claim to trauma, and she refuses our expectations that as a child she suffered more than the adults around her. "Mine is only another story" is the final line in the memoir, a line that occurs immediately after Lobel tries and fails to imagine the feelings her grandmother must have experienced when she was transported. This attempt may be Lobel's adult gesture countering her childhood memory of refusing any recognition to a "large, shapeless woman" thrown in the truck when they are transported. When her brother guesses that the woman is their grandmother, Lobel is terrified that he is right: "'Don't be stupid,' I whispered. 'And keep quiet.'. . . I didn't want us to be connected to a Jewish relative."

The ambivalence that the child feels regarding her parents' behavior (her father's disappearance, her mother's powerlessness) thus produces a memoir in which a child separated from her parents learns to prefer that separation: the parents who find her two years after liberation in a Swedish shelter for Polish refugees embarrass, shame, and anger her. Lobel is outraged when her mother wants immediately to cut her hair as though oblivious to how the trauma of having her head shaved would produce a child unwilling to ever cut her hair again. The memoir structurally enacts Lobel's sense of separation: the years in Poland are but one chapter of her life; "Sweden" follows; and then there are her years in the USA, far longer, she keeps reminding the reader, than she lived as a child in Poland. If she concludes that hers is a happy story, happiness exists only through her ability to block out a "time from which I have very few pretty pictures to remember."

This principle of separation seems apparent as well if we turn to Lobel's picture books. For much of her career, the biographical notes on the dust jackets of her books are silent about her Holocaust childhood. Lobel is presented as a decorative artist, capable of pretty pictures, but not much else; typical are the notes to her illustrations of Three Rolls and One Doughnut:Fables from Russia Retold by Mirra Ginsburg: "Having lived close to peasant art as a child, Mrs. Lobel has always been interested in the decorative arts. She embroiders clothes whenever she can and designs needlepoint tapestries." What is missing in this description is the political aspect to this aesthetic decision, the politics that makes of Lobel not simply a female artist who has time on her hands to do needlepoint, but a child survivor who knows what it is like to live without beauty, and who defies that childhood every time she makes a pretty picture. For just as the powerful effect of Life is Beautiful lies in the scenic representation of Giosuè's fabulous survival in the context of the significant absence of the other children, a different story of Lobel's art is told if we position the picture books and what they suppress in the context of the memoir.

Despite the way the title, No Pretty Pictures, draws a line between Lobel's later life as an American illustrator and her Polish childhood, the line is not only less solid than Lobel claims, but is itself a marker of the survival strategies she found necessary. What is the relationship, for example, between Niania, Lobel's Polish nanny to whose memory Lobel dedicates her memoir, and the many babushka-wearing women who populate her art? The memoirist concludes that Niania was her "demented angel," undoubtedly anti-Semitic yet just as clearly devoted, loving, and determined to protect her two charges. Lobel begins her memoir with the memory of her five-year-old self watching the arrival of the German soldiers in September 1939; holding tightly to her nanny's hands, she records how Niania categorizes and identifies the world for her, first saying, "'Niemcy, Niemcy' ('Germans, Germans')" and then just as contemptuously muttering whenever she sees the neighbor Hasid "Jews!" In hiding Lobel and her brother, the latter dressed as a girl, and with his curly blond hair more easily disguised as a Christian than the dark-skinned Lobel, Niania seems to have regarded the children as somehow not quite as Jewish as the Jews she disliked. Gradually Lobel too absorbs Niania's attitudes and sees herself as more Catholic than Jewish. She longs for blond hair, worries that her dark skin betrays her, and shuns association with other Jews. In the Polish village where they first hide, Lobel feels threatened when her own mother comes to visit, yet the Polish countryside is no paradise: exchanging tablecloths for food, Niania and the two children have excrement thrown on them.

Such ambiguous memories of Poland contest the biographical notes in which Lobel admits to only positive images, e.g., "As a little girl in Poland, I remember weaving chains of flowers and wreaths for my hair" (Alison's Zinnia). Three picture books that span her career, Sven's Bridge (1965), Potatoes, Potatoes (1967), and Away from Home (1994), further indicate not only that Lobel's separation of her Holocaust childhood from her adult art is less tidy than the memoir claims, but that Lobel's need to separate hints at a more complex narrative about child survivors than the one celebrated by the neat happy ending of Benigni's film. Initially the illustrations seem to exist in isolation from Lobel's wartime memories, as though Lobel with her pictures were returning the beauty that was taken away from her by creating a separate utopian world. This is a relationship of replacement, covering over, like the incident she records in the memoir when the Nazi visit to her parents' apartment is marked by the theft of a beautiful rug. When Lobel later sees her mother crying over the transport of her parents and sister, the first time that she ever sees an adult so vulnerable, she recalls her mother standing "in the middle of the empty spot where the kilim rug had been" (No Pretty Pictures). What is covered over in Lobel's first picture book, Sven's Bridge, what cannot be said in 1965, is the memory of that humiliation. The biographical notes to Sven's Bridge carefully avoid any reference to the Holocaust and we read only that "Anita Lobel was born in Krakow, Poland, where she spent much of her early childhood."

Yet like Benigni's viewer who imagines what is not represented on the screen, the reader of the memoir notices in the utopian world of Sven's Bridge, where even kings can be fooled by loyal gatekeepers, that the only colors are yellow and blue, the colors of the Swedish flag, and of the pajamas that Lobel and her brother are given in the Swedish sanatorium when they are rescued from Ravensbrück.[14] Surely the book is a tribute to the land where Lobel first learned to do embroidery and watercolors, the land that returned her to a world of life and color, the land where when a foolish king blows up a bridge, it is replaced with a more beautiful, ornate design. It is not simply a matter of colors. For the narrative itself seems a tribute to Sweden, where Lobel could recover from the terror of sneaking out of the Kraków ghetto by crossing a stone bridge that "felt like a tightrope," aware that any moment Nazi soldiers might turn around and discover her. In order to cross the bridge, Lobel forced herself to remember a painting that hung over her bed before the war of a "beautiful angel . . . [with] giant wings hovering over, almost enveloping two children crossing a bridge over a ravine," a memory with which she controls her fears of Niania's lack of power. Better a utopia in which Sven, the gatekeeper, protects the wooden bridge and all those who need to cross it; in place of Niania with her string bag to fool onlookers into thinking that she is a "lady . . . going to market" (No Pretty Pictures), are the men and women whose fishing nets are not disturbed when Sven raises the bridge. In Sven's Bridge, bridges are safe places.[15]

In contrast, Poland is the place of death: "In Poland everybody ended up laid out, with noses and feet pointing to the ceiling" (No Pretty Pictures). This image of death occurs repeatedly in the memoir, and is established initially when Lobel recounts hiding during a Nazi roundup in the Kraków ghetto. Lying beside her mother, she notes her resemblance to

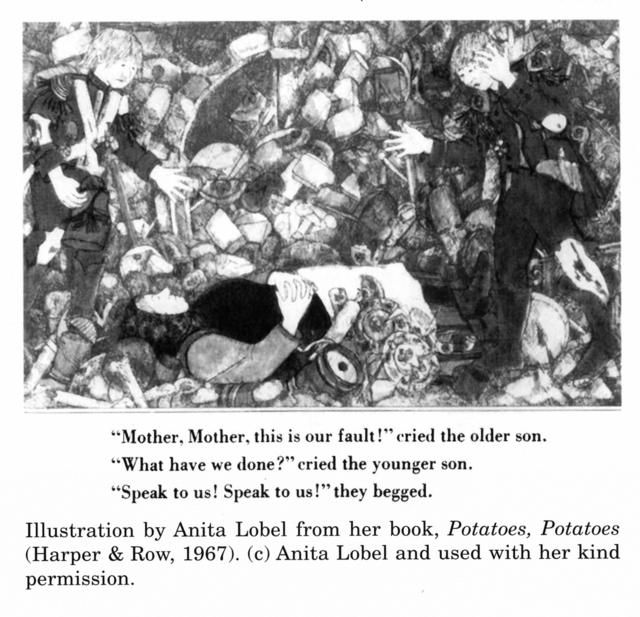

Given the circumstances, it is not surprising that the child imagines the mother as a corpse, and it is easy to understand why, when Lobel later acknowledges the contribution of her wartime memories to her fable Potatoes, Potatoes, she gently belittles reviewers who take the book seriously (Hopkins). Although Lobel resists constructing herself as a child survivor, she nevertheless demonstrates the perspective of a survivor who knows too well the difference between fables and the grim historical reality of Holocaust survival where, as Primo Levi tells us, "it needs more than potatoes to give back strength to a man." By ridiculing reviewers who take the book seriously, Lobel maintains her principle of separation and distances herself from the dust jacket reference to the "timeless lesson" hidden in Potatoes, Potatoes. Memoir writers rarely offer such clear lessons, and the dust jacket biography remains silent on her wartime experience.

Yet in Potatoes, Potatoes, Lobel does draw on her memory of the mother as corpse. The image of the dead mother becomes the comic turning point of the fable, for the two brothers who left home captivated by the attractive uniforms and swords of the opposing armies have become military leaders battling for the potatoes their mother has hidden behind her walls. When the two armies break through the walls and destroy everything, they discover what appears to be the dead body of the boys' mother, a body that Lobel draws as the image she will describe more than thirty years later in the memoir.[16] Just as Lobel's mother only appeared dead, the brothers' mother is also pretending; a critical difference between the fable and the memoir, however, is that in the world of fables the mother has what all mothers lacked during the Holocaust, the power to teach a lesson, and make a difference.[17] The picture book mother lets everyone cry until the lesson sinks in, and then offers the soldiers potatoes only if they "promise to stop all the fighting / and clean up this mess, / and go home to [their] mothers." Yet a further difference is significant, for the boys' mother is dressed not as the fashionable urban woman who appears in the photographs of Lobel's mother that are included in the memoir, but as Niania, the babushka-wearing nanny whose meals of potatoes come to represent the safety in Polish identity that Lobel longs for and misses as soon as she is separated from her. Niania also resembles the mother in Potatoes, Potatoes who learns the impossibility of building "a wall around everything she owned." For like the "woman who did not bother with the war" (Potatoes, Potatoes), Niania learns the futility of advising the children to ignore the fights and hide among the potatoes.

Given the representation of Kraków as a "beautiful painting," perhaps it is not surprising to see how the memory of this picture enables Lobel to risk crossing the bridge between her Holocaust childhood and her pretty pictures. For the memory of "my Kraków" also constitutes the background to the illustration of the letter C in a recent alphabet book, Away from Home, and the image shocks, not only because it is so unusual in Lobel's work, but because its aesthetics are so contradictory.

Away from Home is structured (according to the dust jacket) as "a whirlwind tour of some of the world's wonders," in which young boys visit "exotic places in alliterative fashion" (Library of Congress publication data). The dust jacket assures the reader that in the book's pages she can "start with A and go anywhere [she] want[s]!" The book is clearly autobiographical; on the dust jacket, Lobel identifies herself as a woman who travels in three different (and presumably equivalent) ways: "I have been a refugee. I have been an immigrant. I have been a tourist." Dedicated to Lobel's son Adam, the dedication page shows the Lobels receiving a letter from their son, and the text for the letter A says "Adam arrived in Amsterdam."[18] In the background notes for the letter C, we learn that "Cracow is the city in Poland where I was born. This is its central square." What startles me is the illustration's implied narrative, for the letter C shows a child, obviously Jewish since he wears a Jewish star on his cap and presumably a partisan since he carries a rifle, caught in the stage lights. When "Craig crawl[s] in Cracow" and is caught by the stage lights, I cannot help but see a Jewish child caught by other, more terrifying searchlights, and even find myself worrying about the intentions of the two men holding the stage set. (See page [278]) The image is so haunted by my reading of the memoir that the stage itself starts to look as narrow as a bridge.

While it may be that Lobel can only incorporate the Holocaust into her pretty pictures by repressing her own memories and replacing them with the imagined heroic resistance of a partisan, I am struck by the contradiction between Lobel's attempt to allude to the Holocaust in a children's travel book, and her insistence in No Pretty Pictures of the stark contrast between two kinds of travel: that of a tourist, and her memory of a very different kind of travel: "the furtive ride in a hay wagon, the escape from Niania's village on the old train, and the few steps of a frightening walk across a bridge that then loomed as a dangerous enormous distance." Lobel has refused to return to Poland, to be a tourist in "Auschwitz or Plaszów or Ravensbrück." Her refusal is understandable, far more so than the aesthetics produced by an alliterative alphabet book in which the statement, "Craig crawled in Cracow," is no more frightening or meaningful than "Frederick fiddled in Florence," or "Henry hoped in Hollywood." Lobel ends her biographical statement on the dust jacket with a very clear pedagogical impulse: "I hope this theatrical picture-postcard journey is an invitation to learning more about places far away from home." But how does the invitation to learning work here? Making of the Holocaust an alphabetical entry like any other in a child's tour of the world's wonders, Lobel attempts an aesthetics that is deeply disturbing, one that makes me question the impossible demands we make upon Holocaust representations for and about young children. For what is the point to a Holocaust image that is so determined to give pleasure to young children that it is silent about its own implicit terror? Benigni's fable demands an adult viewer whose aesthetic pleasure is produced and affected by her awareness of a genocide that Benigni refuses to show; thus when Guido is caught in the searchlights, the viewer knows, even if she does not see, what happens next. In contrast, Lobel's pretty picture requires a child reader whose ability to take pleasure in the image of a Jewish child caught in the searchlights is dependent on an ignorance of the history that produces it, and a refusal to imagine what happens next.

NOTES

1. Dwork is thinking of the absurdity, for example, of asking an infant why she didn't resist being taken to the gas chambers.

2. A comparable example of the authority and safety provided by age is operative in the Canadian children's book, Uncle Ronald, by Brian Doyle. The narrator, Old Mickey, is one hundred and twelve years old, old enough apparently to tell a narrative of child abuse that is both painful and comic.

3. I refer to this text as a memoir and the author as Wilkomirski since the text's critical success was determined by readers who accepted its presentation as memoir and never questioned the identity of the author. Wilkomirski has given few interviews since the publication of the allegations; in an interview that was part of a 60 Minutes documentary broadcast February 7, 1999, he still insists that Fragments is a true account of his past. See Elena Lappin, "The Man with Two Heads," Granta 66 (Summer 1999), 7-65, and Philip Gourevitch, "The Memory Thief," New Yorker, 14 June 1999, 48-62 and 64-8, for articles that contest and explore this self-presentation. At the Frankfurt Book Fair, October 1999, Suhrkamp Verlag, Wilkomirski's original publisher, acting on a preliminary report by a Swiss historian that concluded that the author of Fragments was not Binjamin Wilkomirski, a Holocaust survivor, announced that it was withdrawing all hardcover copies of Fragments.

4. For an example of such questioning, see Blake Eskin, "Lawyer Demands Probe of Wilkomirski," Forward, 19 November 1999, 15.

5. Critics of the film seem both inconsistent and indifferent to the question of a child's knowledge; they typically condemn the film because they assume that adult viewers are ignorant of the Holocaust and so will naively believe that what they see on the screen is historically accurate. Yet such critics routinely base this aesthetic objection on their own historical awareness of the Holocaust. And they ignore how the film itself problematizes the child's limited knowledge; i.e., Giosuè hears more than what his father tells him. In addition, such critics do not consider how Holocaust representation in children's literature always works within limits. For example, in David Denby's second and extremely negative review of the film in the New Yorker, he concludes that "Benigni protects the audience as much as Guido protects his son; we are all treated like children" (99). In response, Eric McHenry chastises Denby for treating the film's viewers "like children" when he ignores how the film "depends upon the audience's remembrance of the Holocaust" (Letter, New Yorker, 10). My attention to the question of the child's knowledge is also indebted to a colleague who concluded his contemptuous dismissal of Life is Beautiful by asking me if I knew that the concentration camps were dirty and that people vomited in them. My astonishment about his assumptions regarding my knowledge or lack thereof prompted me to think more clearly about the question of knowledge and the construction of the child.

6. All quotations from Life is Beautiful are from the English version.

7. This faulty assumption has led some reviewers to praise Benigni's film while advising viewers that if they want the truth of the Holocaust, they turn to Steven Spielberg. It may also account for how some viewers of Claude Lanzmann's Shoah celebrate the documentary's "truth" without considering how Lanzmann pushes the survivor, e.g., the barber, to communicate only the traumatic truth that Lanzmann is interested in; Lanzmann is simply not interested in post-Holocaust narratives that tell other kinds of truth.

8. For an analysis of why Italian Jews generally did not believe that they were threatened by the Nazis, see Susan Zuccotti, The Italians and the Holocaust: Persecution, Rescue, and Survival.

9. When is a door not a door? When it's ajar.

10. That some adult viewers are shocked when Guido is killed (the hero is not supposed to die) indicates how my analysis presumes an adult viewer, familiar with the history of the death camps and the chances of survival. Like much of the fiction of Aharon Appelfeld, Benigni's ability not to show us atrocities is dependent on our awareness of what is not shown. (See the discussion of Appelfeld in Michael André Bernstein's Foregone Conclusions: Against Apocalyptic History.) If the viewer is ignorant of the history of the death camps, then Guido's death works very differently, in fact more like the educational plot of children's narrative, and the viewer is then responding as adults imagine a child would.

11. I am thinking also of newspaper advertisements for Life is Beautiful that tell us that the film demonstrates how love and imagination conquer all.

12. In children's Holocaust novels such as Hide and Seek and Anna is Still Here, Ida Vos narrates the postwar trauma of family relations for the child reader.

13. A question that Dwork might say is another example of the wrong kind of question.

14. In discussing Sven's Bridge, I am responding to the original edition, not the revised full color edition published by Greenwillow in 1992. In the revision, the words remain the same. Despite the full color, the flags are still painted in the original yellow and blue. The new edition is larger than the original; what adds to its size is the white space that now frames the illustrations and becomes the new location for the words. Marketed for parents "who loved it when it first appeared," the new edition restricts its dust jacket authorial information to a listing of Lobel's "well-known" books. Since the dust jacket also asserts that Lobel is "well known" to the purchasers who presumably read Sven's Bridge when they were children, there is no need to provide any biographical information. Yet it is worth observing that the original dust jacket identity of an artist "born in Krakow, Poland" has been replaced by the less specific identity of the artist as celebrity.

15. In e-mail correspondence, Maria Nikolajeva has pointed out that the illustrations to Sven's Bridge combine the colors of the Swedish flag and some aspects of Swedish folk art with other details that seem closer to central European art.

16. The relationship of life and art is unclear here. What comes first, the child's memory of the mother as corpse, or the illustration of the picture book mother as corpse?

17. The most traumatic incident in Lobel's memoir, one that demonstrates the general reality of maternal lack of power, is when a woman whose son has just been shot begins to scream and demands from the guards why they have not shot Lobel's brother who is so much younger. Lobel admits that she is more afraid of the woman than of the Nazis and loses her own ability to speak, for fear that the woman's appeal will be heard.

18. Lobel's notes for the letter A tell the reader that in Amsterdam there are "houses that look like these." That Anne Frank, the most famous Holocaust victim in children's literature, lived and hid in such a house, only comes to mind because of the problematic inscribing and erasing of Holocaust history in the letter C, i.e., the lack of such information is not problematic in the notes to the letter A.

Works Cited

Bernstein, Michael André. Foregone Conclusions:Against Apocalyptic History. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1994.

Denby, David. "In the Eye of the Beholder: Another Look at Roberto Benigni's Holocaust Fantasy." New Yorker, 15 March 1999: 96-9.

Doyle, Brian. Uncle Ronald. Vancouver: A Groundwood Book, Douglas and McIntyre, 1996.

Dwork, Debórah. Children With a Star:Jewish Youth in Nazi Europe. New Haven: Yale University Press, 1991.

Epstein, Eric Joseph and Philip Rosen. Dictionary of the Holocaust:Biography, Geography, and Terminology. Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1997.

Eskin, Blake. "Lawyer Demands Probe of Wilkomirski." Forward, 19 November 1999: 15.

Frank, Anne. The Diary of a Young Girl:The Definitive Edition, ed. Otto H. Frank and Mirjam Pressler. Trans. Susan Massotty. New York: Bantam, 1997.

Ginsburg, Mirra. Three Rolls and One Doughnut:Fables from Russia Retold by Mirra Ginsburg. Illus. Anita Lobel. New York: Dial Press, 1970.

Gourevitch, Philip. "The Memory Thief." New Yorker, 14 June 1999, 48-62 and 64-8.

Holm, Anne. I Am David. Trans. L. W. Kingsland. Harmondsworth: Puffin, 1969.

Hopkins, Lee Bennett. "Anita and Arnold Lobel." Books are by People: Interviews with 104 Authors and Illustrators of Books for Young Children. New York: Citation Press, 1969, 156-9.

Lappin, Elena. "The Man with Two Heads." Granta66 (Summer 1999): 7-65.

Levi, Primo. Survival in Auschwitz:The Nazi Assault on Humanity. Trans. Stuart Woolf. New York: Collier-Macmillan, 1961. Trans. of Se questo è un uomo (1958).

Life is Beautiful (La Vita è Bella). Dir. Roberto Benigni. Alliance, Miramax, 1997.

Lobel, Anita. Alison's Zinnia. New York: Greenwillow, 1990.

———Away from Home. New York: Greenwillow, 1994.

———No Pretty Pictures: A Child of War. New York: Greenwillow, 1998.

———Potatoes, Potatoes. New York: Harper and Row, 1967.

———Sven's Bridge. New York: Harper and Row, 1965.

———Sven's Bridge. Rev. New York: Greenwillow, 1992.

McHenry, Eric. Letter. New Yorker, 29 March 1999: 10.

Nikolajeva, Maria. "Sven's Bridge." E-mail to the author. 11 Aug. 1999.

Vos, Ida. Anna is Still Here. Trans. Terese Edelstein and Inez Smidt. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1993. Trans. of Anna is er nog (1986).

———Hide and Seek. Trans. Terese Edelstein and Inez Smidt. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 1991. Trans. of Wie nieht weg is wordt gezien (1981).

Wiesel, Elie. Night. Trans. Stella Rodway. New York: Discus-Avon, 1969. Trans. of La Nuit (1958).

Wilkomirski, Binjamin. Fragments:Memories of a Wartime Childhood. Trans. Carol Brown Janeway. New York: Schocken, 1996. Trans. of Bruchstücke (1995).

Yolen, Jane. Briar Rose. The Fairy Tale Series. New York: Tom Doherty, 1992.

Zuccotti, Susan. The Italians and the Holocaust: Persecution, Rescue, and Survival. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 1987.