On "In a Siberian Town" and Its Author

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Rasputin is also well known in the West and in the United States. In addition to being standard fare in any university curriculum dealing with modern Soviet classics, Rasputin's novellas and short stories, as well as a number of sketches about his native Siberia, have appeared in English translation. They have also received critical acclaim; in fact, after the 1987 publication of You Live and Love, a newly translated anthology of Rasputin's stories, the Siberian writer was hailed by the New York Times as nothing less than "a major literary phenomenon."[2] At the same time, pieces on Rasputin have surfaced in a wide range of American publications, from People magazine, which featured a special issue titled "People . . . Goes to Russia" in April 1987; to National Geographic, which published a lengthy essay called "Siberia in from the Cold" in March 1990; to the New York Times Magazine, which offered its readers an extremely controversial interview with the author in a January 1990 article entitled "Russian Nationalists: Yearning for an Iron Hand" by Bill Keller, a 1989 Pulitzer Prize recipient for foreign reporting who at the time was Moscow Bureau Chief of the Times; and to a rebuttal of Keller's piece in The New York Review of Books in a February 1991 article by Peter Matthiessen called "The Blue Pearl of Siberia."

Insofar as Rasputin was so closely identified with the village prose movement of the 1960s and 1970s, it is useful to discuss, however briefly, the following question: what is "village prose" and what are its most salient features?

In the Stalinist years, peasants were featured in most novels, but they were usually depicted "as people whose way of life was still backward, degrading and needing to be modernized."[3] After Stalin's death, though, the approach became altogether different. Instead of seeking to change the peasantry, the derevenshchiki, or ruralist authors, now turned to them in search of purity, simplicity, and precious moral and ethical values; and it was this, perhaps more than anything else, that Rasputin shared with the derevenshchiki. Like his contemporaries, he was nostalgic for the "wholeness" of rural existence and preoccupied with humanity's moral health.

Why this search for enduring values? As was often the case with Soviet literature, the explanation could be found in contemporary reality. With the accelerated development of the scientific and technological revolution and the waning of Marxist-Leninist ideology, such features as apathy, duplicity, greed, and philistinism became widespread in modern Soviet society, while "solemn dreams" and hope for the future were replaced by spiritual emptiness and a kind of hedonistic "live for today" creed.[4] So, seeking refuge elsewhere, Rasputin, along with other Soviet writers, looked to his roots—to the countryside and the spiritual and moral wealth intrinsic to the age-old peasant culture—as an alternative to modern technological civilization.

Their pilgrimage from the city to the country, though, was a journey less of distance than of time. As village writers themselves have acknowledged, the Soviet village in the 1960s and 1970s—and the values that it had come to typify in recent decades—did not afford a cure to the nation's ills. On the contrary, villagers had become as self-interested and callous as their city counterparts. What was particularly striking about them was their complete disregard for the countryside and their sharp dismissal of the notion of "roots." Craving the accoutrements of modern society, villagers were only too happy to migrate to the city for a higher standard of living, only too eager to see the old village disappear altogether. Motorcycles, sewing machines, and telephones everywhere; forests razed to the ground for profit; factory chimneys pouring smoke over villages—all these became common images in rural literature. So, with a decay as rampant in the country as in the city, village writers turned wistfully to an earlier era—to the time represented by traditional rural Russia—and sought to revive its spirit and its precious moral and ethical values, hoping to regenerate a corrupt and jaded Soviet society.

All this is not to suggest, however, that Rasputin and other village writers wished to preserve the village life of the past, or to turn the clock back. Recognizing that the old peasant culture had many backward and primitive features, most of them regarded progress as unavoidable and necessary. Rather, their pleas on behalf of the old bucolic way of life stemmed from a desire to turn what is most essential and viable in the moral experience of the Russian peasantry into an imperishable element of present-day culture. As one Russian critic has observed, "We want to return to our sources, not in order to remain there, but, proceeding from their morality and ideals, to move further along, to build something new."5

Another way of assessing village prose is in terms of its nationalistic features. Besides sharing a profound love for some aspects of Russia's prerevolutionary past, the derevenshchiki and the Russian nationalists were united on a score of other issues as well. Both regarded excesses of technology as a threat to precious cultural and moral values; both encouraged patriotic sentiment and love for the Motherland; both advocated religious freedom and a revival of Christian morality; both struggled against the ruin and wanton destruction of ancient Russian churches and historical monuments and encouraged environmental preservation; and, finally, both extolled the peasantry, who are the repository of values intrinsic to their heritage and the bucolic countryside in which they reside. It is only logical, then, that Rasputin became, in subsequent years, a self-proclaimed "cultural nationalist."

As all this would seem to suggest, there was much in village prose that was discordant with—or even hostile to—official Soviet precepts and ideology: tacit approval of religion, preoccupation with the past, and critical treatment of technology and material progress. Paradoxically, though, writers of village prose remained relatively free from harassment and were even applauded among official circles for their literary achievements. One might call it a concession of sorts: while the rural authors "erred" on some issues, their stance on others very nicely suited the needs of the government at that moment. Divorce was on the rise, alcoholism was rampant, the birth rate was dangerously low, and spiritual and moral depravity was prevalent. Since these problems seriously threatened the well-being of the Soviet state, it is hardly surprising that village writers, by insisting on the need for moral values, reproduction, and family stability in their works, managed to ingratiate themselves with Party officials. So although Rasputin and other derevenshchiki could not be regarded as "establishment types," neither did their creative output lie entirely outside the domain of the Party's values.

As the "darling" of village prose, Rasputin was attentive to ethnographic detail, made extensive use of nature description, and depicted the daily rounds and customs of the contemporary Siberian village with precision and authenticity. Ultimately, though, the village was not a matter of central interest for Rasputin; instead of focusing on problems that were topical in nature and exclusive to a village setting, he preferred to pose questions for discussion that went far beyond the confines of peasant byt, or way of life—eternal, philosophical questions, such as life and death and good and evil. Nor was he as vocal as his contemporaries on current social problems. While most ruralist authors used their writings as a vehicle for social protest, this element was more or less absent from Rasputin's writings in the 1960s and 1970s. The exception was his 1976 novella Farewell to Matyora, which exposes the callous excesses of the technological revolution at the expense of the Russian people (the flooding of a Siberian village in order to build a hydroelectric dam); this work is also widely regarded as the culminating point of the village prose movement in general. Yet another obvious exception, of course, is "In a Siberian Town," which is, perhaps above all else, a work of sharp political protest.

I first became interested in Rasputin's writings as a graduate student at the University of Michigan in the early 1980s. It was in a seminar on contemporary Soviet literature that I was introduced to Andrei Bitov's Life in Windy Weather, Yury Trifonov's The Exchange, Sasha Sokolov's A School for Fools, Vasily Shukshin's Snowball Berry Red—and Valentin Rasputin's Live and Remember. My professor was the late Carl Proffer, who taught Russian literature at Indiana University before returning to the University of Michigan, where he had received his undergraduate and graduate education; he and his wife, Ellendea, were also the founders and publishers of Ardis Press. Impressed by the image of Live and Remember's heroine, Nastyona, I started reading other stories by Rasputin, and this eventually led to my choice for a dissertation topic: Women in the Prose of Valentin Rasputin.

As luck would have it, I was able to meet Rasputin for the first time in Ann Arbor, as I was working through the last lap of my dissertation. My dissertation chairman, the late Deming Brown, one of the foremost specialists in the United States on contemporary Russian literature, called me excitedly with the news early in the morning: Rasputin had come to Ann Arbor, and we were to meet him for lunch in a restaurant located across the street from campus. I was seated next to Rasputin, and although I had a million questions on the tip of my tongue, I opted instead for a few simple, if not trivial and mundane, questions like "How do you like American food?" I mention this detail for good reason: standing in front of the restaurant after lunch, the incredibly shy and reticent Rasputin turned to me and thanked me for keeping our conversation on the light side; although he was extremely adept at expressing his views with a pen, oral questions, he told me, made him uncomfortable. It was this incident that became the foundation of our subsequent friendship.

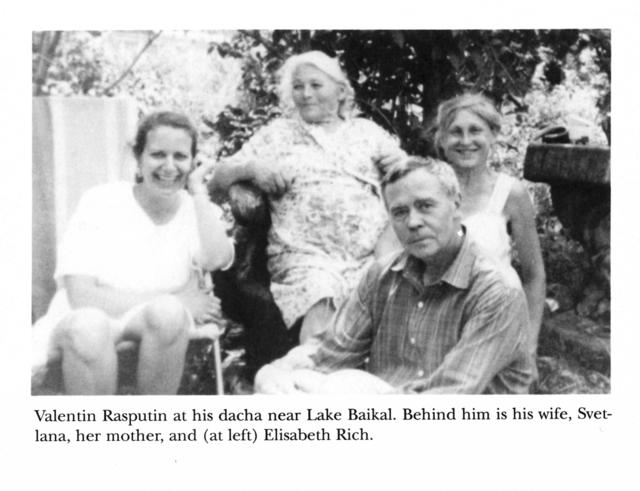

Since the mid 1980s I have visited with Rasputin on a number of occasions in Moscow; sometimes we have met at a mutual acquaintance's, sometimes at the spacious apartment he acquired in 1990 when he became a member of Gorbachev's Presidential Council. Our relationship became even warmer when I traveled to Rasputin's home city—Irkutsk, one of the oldest cities in Siberia—in July of 1994; the trip was funded by a Short-Term Travel Grant from the International Research and Exchanges Board (IREX).

The primary reason for this trip was to meet with Rasputin himself, who resides in his native Irkutsk in the summer. In this respect I could not have been more fortunate. Although Rasputin had only just returned from Moscow and had pressing obligations, he dismissed these concerns to give me over a week of his time. In fact, I practically became a member of his family, spending time with him, his wife, Svetlana, and their daughter, Maria, at their dacha near Lake Baikal; eating meals with them that were so intimate and informal that I felt I could gently berate Rasputin for his unhealthy, yet typically Russian, love for butter; taking family outings that included an excursion to the architectural-ethnographical museum of wooden art of Siberia, which is situated under the open sky on the forty-seventh kilometer of the Baikal Highway; and playing Scrabble with them in the evening. (Maria, a student at the Moscow Conservatory at the time, came in first; Rasputin—second place; while I, who was teamed with Rasputin's then-seven-year-old granddaughter, Tonya, came in a distant loser.) It goes without saying that these informal meetings enabled me to get a more intimate picture of Rasputin the man; they also allowed me to observe firsthand many details of Rasputin's immediate surroundings, which the author depicts in his writings—things like stopping on the way to his dacha to buy milk from an old woman who still owned her own cow. Most important, though, were our lengthy conversations that Rasputin allowed me to record on audiotape and that produced over eighty typed pages when transcribed. It was also during this trip that Rasputin provided me with a letter giving me the rights to translate his three new short stories—among them, "In a Siberian Town"—and to place them wherever I liked in the United States; in this letter he also gave me permission to receive copyright in his name. I was delighted, since these stories came on the heels of his controversial four-year political career and represented his first artistic writings in nine years.

It was with the 1985 publication of Pozhar (The Fire), a novella that reads like a "sequel" to Farewell to Matyora, that Rasputin abandoned his creative Muse. At the time this seemed odd, since The Fire was hailed by John B. Dunlop, in a 1989 review in the New York Times Book Review, as "the first major cultural event of the thaw begun by Mikhail Gorbachev";6 it also received the prestigious Soviet State Prize in 1987. Instead, having become in the early 1980s more deeply involved in the Soviet environmental movement, especially in the crusade to save Lake Baikal from the pollution caused by industrial waste, Rasputin limited the bulk of his literary activity to a series of essays on the past and present of his native Siberia; and it was Rasputin's environmental stance that led, at least in part, to Gorbachev's decision in 1990 to appoint him to the Presidential Council as an advisor on Russian culture and the environment.

It might seem peculiar that Rasputin should abandon creative prose at the very height of his popularity in Russia, but in fact it was not, especially in view of Russia's unusual political and literary circumstances in the mid to late 1980s. Like many of Russia's other leading writers, Rasputin was experiencing a creative crisis. How, after all, can a writer capture aesthetically a reality that is in a perpetual state of flux and uncertainty, in a state of instability, upheaval, and political turmoil, when things change drastically from week to week? For realistic fiction, which requires time for interpretation, the lines of this new world must become more distinct before a writer can describe it in fictional terms. This explains why many writers became silent at this time, or turned to publicistika, public-affairs writing, which allowed them to focus on specific aspects of a phenomenon and transmit informative and critical reports about Soviet history and contemporary life in the most direct and quick way possible. Making a generalization that applies as much to himself as to any other Russian writer, Rasputin told me in 1994, "The writer got lost in this situation, and for a long time did not know what he should do, how it would be with him, what to write about."

Rasputin's political involvement was also consistent with his beliefs about the writer's role in society. Schooled in the classical canons of Russian literature, which called upon writers to become involved in current social questions, Rasputin believes in what he calls the writer's "civic duty" to society: his obligation to educate his readers and to raise their level of social and ethical awareness, and his obligation to take a moral and social stand. Thus, for Rasputin, the leap from literature into the political arena was not only a relatively easy one, but in fact a virtual necessity given the political and social urgency of the times.

Rasputin's political career, though, was shrouded in turbulence and controversy. Indeed, many Westerners feared that the self-proclaimed cultural nationalist might encourage anti-Semitic sentiment and thwart Gorbachev, defeating democracy.

In July 1994 Rasputin repeatedly stressed to me that he is not anti-Semitic and never has been, saying that "the main thing is what I think about myself and I know that I am not anti-Semitic, that I have never taken part in any propaganda against any kind of people, and that I, as a nationalist, do only things that will enable the Russian people to become better than they are." Vexed and angered by the endless accusations and charges that he is anti-Semitic—a controversy to which I perhaps tactlessly referred—Rasputin answered me with a question: "Can you explain to me," he blurted out, "why journalists continually ask this question, why there are no other questions? This is not the most burning question in the world, and it is not the most burning question now in Russia." Later, when I asked him what he considers to be indeed the most painful question now in Russia, he responded: "The most painful place—this is Russia's situation, what will happen to Russia, where the leaders are pulling her, what they are trying to make from her, whether or not they are trying to make her one of the banana republics—that is, a third world country, a territory of raw materials—or an independent country. This is the main thing today. And in this the Jews are also taking part, some on one side, others on the other side. It is not a problem of nationalities, but a question about Russia."

It should be mentioned that although Rasputin is a nationalist who pines for Russia's prerevolutionary past, he is not opposed to democracy. On the contrary, he supports democratic reform, but believes that the transition to democracy should have been a gradual one. In Rasputin's opinion, the people have not properly assimilated the transition, and this has led in turn to a mutilated form of democracy, bringing the most dire consequences for the country: confusion, social and cultural disintegration, erosion of moral and ethical values, lawlessness, chaos, and anarchy. "This is madness," he told me in 1994. "We have no democracy, as it is meant in the very understanding of the word. Nor, for the most part, was there ever democracy in this country, insofar as we had a different tradition, in the beginning monarchical, then Communist, if it is possible to call the Communist tradition a tradition. Therefore, democracy crashing down on Russia all at once . . . that is, we should not have thrown down democracy, like the free market, on Russia, as if to say, 'Please go ahead and profit from it.' Democracy here has turned into something contrary to democracy; there is no democracy, only freedom of the word, freedom of the press, and even this is a deformed freedom." At that time, many articles in American newspapers and magazines corroborated Rasputin's point of view. Even the Boston Globe, a liberal newspaper, had this to say in an August 1994 editorial on Russia's "troubled evolution":

It is not difficult to understand why Rasputin, who loves his country and wants the best for it, bristles when he hears or says Boris Yeltsin's name and is waging a campaign against what he perceives as all the evils that have floated to the surface under Yeltsin's leadership.

Rasputin's brief tenure on the Presidential Council not only was steeped in controversy, but was pathetically unrewarding as well. Well intentioned, with relatively modest goals, Rasputin sought no more than to preserve Russian culture and to secure resolutions that might help save his beloved Lake Baikal from pollution and human despoilment. Yet, none of his agenda was ever carried out. With an edge of bitterness in his voice, Rasputin described to me his role on the Presidential Council as being almost pointless and rendering no beneficial results for either him or the country. "At this time," he explained, "destructive events were already escalating, and, basically, I succeeded in achieving nothing. I went to see Gorbachev several times and said, 'Let's talk about Baikal,' and he would say, 'What are you thinking; don't you see what is going on in Lithuania?' and so on. Actually, there were more pressing questions than Lake Baikal at that time."

Even after the disbandment of the Presidential Council on Christmas Day, 1990, nine months after Rasputin's initial appointment, he continued to play a political role as a chosen member of the Congress of People's Deputies until the breakup of the Soviet Union and the subsquent dispersal of the deputy body. Rasputin then turned to publicistika, but abandoned this activity too, since he believes that the conditions of Russian life no longer need to be brought to the attention of the Russian people through publicistika; they are all too painfully and strikingly visible without it. "It seems to me," he told me in 1994, "that publicistika is now running on idle. It has done its deed. Perhaps it was not necessary to be so actively involved, but still it seemed that words could help people to gain an understanding of that turmoil of events, opinions, parties, and organizations that at that time had cropped up. I don't know whether or not it helped, but I did succeed in championing some things. Now it is no longer necessary to watch television, to read publicistika. Everything is taking place before our very eyes; everything is visible . . . what we have come to, what kind of politicians are leading us, where things will go from here. . . . In general, a person with a mind can figure things out himself."

Small wonder, then, that Rasputin has started writing imaginative prose again. What other viable options does he have? His political career was unrewarding—indeed, his efforts were in vain—and certainly quashed any future political ambitions that he might conceivably have had. Nor can he be useful or make a difference today through publicistika, a genre that has practically expended any authority it once wielded. Undoubtedly, he hopes to reach the public through his new stories, to have his voice heard over what he considers to be the din of lawlessness and chaos in post-Soviet Russia.

In some respects, "In a Siberian Town" is predictable and reads like the logical offshoot of Rasputin's last novella, The Fire, a work of strong social protest, highly topical in form and content; it also reads like an offshoot of his post-1985 political involvement and publicistika. Like The Fire, "In a Siberian Town" is a good example of publicisticheskaia proza, or "publicistic prose," dealing with issues of current public urgency in which the author's attitudes are clearly revealed. Compared with that of his earlier stories, however, the source of political ills has changed. Before perestroika, Rasputin targeted Communism and the excesses of the Technical Revolution as the facilitators of social and moral degradation in Russian society; now he is challenging the post-Soviet political order, Yeltsin, and the lawlessness and moral depravity that Yeltsin's so-called reforms have unleashed. It is in this context that "In a Siberian Town," a story portraying the government's illegal, dictatorial takeover of a regional administration building, should be read.

Politically, "In a Siberian Town" is a strong story. Serving as an inspiration for all the other citizens in this Siberian town, Verzhutsky, a chudak, or eccentric, who is from a family of exiled Poles, is the first to wave the flag of democracy and to protest actively the government's illegal takeover of the town administration building. We are repeatedly told that guards with rifles have surrounded its entrance and threaten to shoot on sight anyone who dares to approach it. Still, Verzhutsky, who only wants to find out what is going on, moves toward the entrance, waving a handkerchief as a sign of peace. What follows is a highly dramatic moment: although the guards threaten to shoot him on the count of three if he does not retreat, we do not really believe that they will gun this old man down, yet, shockingly, they do. Nonetheless, Verzhutsky has set a bold precedent for the rest of the community to follow.

Others, in fact, do follow his example. When the guards ask a Cossack to show himself, which is an obvious provocation on their part, he walks through the crowd with a disregard for his own person, and is gunned down. Others follow suit. When the guards ask if any other people wish to step forward, an elderly woman with gray hair crosses herself and defiantly takes a step. The most poignant symbol of courage, though, comes when two children—a boy and a girl with their hands joined together—step forward; and it is their courage that prompts another character, Timosha Tepljakov, a twenty-eight-year-old engineer from the radio factory, to step forward too. Although in spirit he had wanted to make that courageous step forward earlier as an act of defiance and protest, concern for his small son had prevented him. "This is foolish," he thinks. "I have a son growing up, they won't be able to raise him without me. . . ." When he sees the two children stepping forward, he realizes that it is precisely because of his son that he too must take that step. Of course, it is not difficult to guess what kinds of questions are floating through his mind: is this government takeover not a form of lawlessness and tyranny? How will his son have a life free of oppression, if he and the rest of the community do not protest this lawlessness? Nor is it surprising that he feels free when he takes that first step, and even freer with each subsequent step. In short, all these characters are heroes, for each literally and symbolically takes a step forward toward true democracy.

"In a Siberian Town" is a transitional piece of sorts; it marks Rasputin's first attempt at artistic writing after a nine-year hiatus. "It is not as simple to return to prose as it seemed," he told me in 1994. "When I begin a new story, I involuntarily resort to the language of publicistika; I involuntarily slide down there. I understand this danger; I see the slope, this inclined plane that is pulling me. I understand all this, but still it drags you there, because the language and methods of persuasion that I used for publicistika have already firmly established themselves as my creative organism." Gradually, though, Rasputin is finding it easier to move away from it and to overcome its influence; in fact, as recently as 1996 he was awarded the International Literary Prize Moscow-Penne for two of his newest short stories, "V ty zhe zemliu . . ." ("In That Very Land. . . .") and "V bol'nitse" ("In the Hospital"), both of which appeared in the Moscow journal Nash sovremennik (Our Contemporary) in 1995. Nor is it especially surprising that Rasputin, who is most acclaimed for his povesti should choose the short story for renewing his literary career. "It is like in the beginning of a journey," he explained to me. "It is necessary in the beginning to become a practiced hand, and then I will set to work on a novella."

Translating this short story was at times fraught with difficulties. Still, it is an easier task to translate stories by Rasputin than to translate those of his ruralist contemporaries—writers such as Viktor Astafyev, whose use of words and expressions could send a present-day Muscovite scrambling for his or her dictionary. Avoiding excessive use of regional peasant dialect and provincialisms, Rasputin uses a narrator whose language tends to be literary, lean, and in the classical tradition, while dialogue among characters—aside from a healthy sprinkling of colorful and expressive Siberian dialect—is intelligible even to non-Russian readers. There are also occasional lapses into journalese, as happens to be the case with "In a Siberian Town."

The central question behind one's approach to translation is the inevitable "Should I translate literally or freely?" As a stickler for truth and accuracy, much like Rasputin himself, I believe in complete fidelity to the text; only when it was completely necessary—when there were sound and pragmatic reasons for doing so—did I take "poetic license" and indulge in what is commonly referred to in the profession as "free translation." Since I was translating a story brimming over with political nuances and references to Russian history, especially in its opening pages, the need for creating internal footnotes, or supplying historical and political glosses within the text, became unavoidable. The literal translation of Rasputin's "drevnij Kiev s varyazhskoj druzhinoj," in the first paragraph, did not seem sufficiently intelligible as "medieval Kiev with its Varangian voluntary brigade"; "medieval Kiev with its voluntary brigade of Varangian warriors" seemed to convey a better semantic sense of this phrase. There were other ambiguities in the text that required elucidation, such as the sentence "Velikikh sobytij v nekogda velikoj strane teper' tak mnogo—kazhdyj den' velikoe tseloe drobitsya na velikie oskolki. K nim ponevole privykaesh'. I oni, v svoyu ochered', slovno boyas' zashibit' nas, opadayut bezgrokhotno i vyazko, kak pesok, i tol'ko posle uzh ponimaesh', chto kazhdoe iz nikh s soboj uneslo" which literally translates as: "There are now so many great events in this once-great country, that every day this great whole crumbles into great splinters, and, little by little, you get accustomed to this. And as if afraid of bruising us, these splinters fall away without a rumble, in a muddy way, like sand, and only afterward do you really understand what each of them has carried away." "Great splinters" as a metaphor for the republics that have seceded from Russia in the post-Soviet era would be obvious to a Russian audience; for an American audience, the meaning would be far more obscure. Therefore, I felt compelled to add the words "our great republics" as a semantic qualifier. I also made other minor concessions on behalf of the reader, sometimes allowing for what is called the "creative exception." For example, in the hopes of conveying a little local color, I transcribed words, such as myzhik and voskresniki, and then followed them with their English translation "peasant" and "volunteer work on Sundays."

Finally, I close with the question that confronts every translator at some point: was this story really worth translating? And will it have an impact on an audience that is distant from the social, political, and cultural milieu for which it was originally intended? I firmly believe it will, and I hope my readership concurs.

NOTES

1. Portions of this essay originally appeared in my Ph.D. dissertation, Women in the Prose of Valentin Rasputin (University of Michigan, 1985).

2. James H. Billington, "The Other Siberia," review of Valentin Rasputin's You Live and Love, New York Times Book Review (10 May 1987), 22.

3. Geoffrey Hosking, Beyond Socialist Realism: Soviet Fiction Since Ivan Denisovich (New York: Holmes & Meier Publishers, Inc., 1980), 50.

4. See David K. Shipler's Russia: Broken Idols, Solemn Dreams (New York: Times Books, 1983), 1-390; and Geoffrey Hosking's Beyond Socialist Realism: Soviet Fiction Since Ivan Denisovich, 82. My personal observation based on lengthy stays in the former Soviet Union confirms these authors' accounts.

5. John B. Dunlop, The Faces of Contemporary Russian Nationalism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1983), 110.

6. John B. Dunlop, review of Siberia on Fire, New York Times Book Review (17 December 1989), 1.

7. "Russia's Troubled Evolution,"Boston Globe (19 August 1994), 18.