Death of a Salesman: A Playwrights’ Forum

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Running for 742 Broadway performances, Salesman entered the canon of American theater with glory. Eugene O'Neill gave the play his imprimatur: "Miller's bolder than I have been . . . I'm not so sure he hasn't written a great American play."[2] Brooks Atkinson proclaimed in the New York Times that "Miller has written a superb drama. . . . It is so simple in style and so inevitable in theme that it scarcely seems like a thing that has been written and acted. For Mr. Miller has looked with compassion into the hearts of some ordinary Americans and quietly transferred their hope and anguish to the theater."[3] Twenty-five years after the premiere, London critic Harold Hobson pronounced Salesman, along with A Streetcar Named Desire and Long Day'sJourneyinto Night, "one of America's three greatest plays."[4] This trinity of plays represented the best American theater offered to an admiring audience of world theatergoers. As Miller himself noted, "I think it is true that wherever there is theater in the world, it has been played."[5]

Miller's accomplishments in Salesman were revolutionary for 1949, fundamental for 1999, the play's golden anniversary. His use of time—not flashbacks or interruptions, he is quick and right to point out—was highly experimental, proleptic. According to Miller again, Salesman "is one continuous poem."[6] Equally controversial in 1949 was Miller's idea that Salesman was a tragedy of the common man. Salesman proved that essential tragic ingredients—moral choice, conflict, disruption in family and state, intense loss—were no less viable in the twentieth century than in Sophocles' or Shakespeare's eras. The grumblings of Joseph Wood Krutch over this issue of genre seem short-sighted today in light of the way time has endorsed Miller's views.[7] Perhaps one of the most profound insights on the common man's tragedy came from Miller himself in a 1969 interview: Willy's "uniqueness was bypassed in favor of his total obedience to social stimuli, and he ends up as he does in the play, believing in what he is forced to rebel against."[8] This is as close to hamartia, peripeteia, and tragic fate as it gets. Miller knew full well that "Man is in society but the society is in the man and every individual."[9] Willy's tragedy continues today each time a promised golden parachute fails to open, a job or department is phased out, or a technological advance leads to a personal retrenchment. The tragedy of the Family Loman is replayed as cities decay and their residents' dreams with them.

As the above comments from Miller prove, the playwright is also a perceptive critic—of society and of art, which for Miller are inseparable. Miller's acuity is shared by many of his fellow playwrights as well. To honor the 50th anniversary of Salesman on Broadway, I gathered the following encomia, interpretations, reappraisals, and memoirs from some of America's most distinguished playwrights. I encouraged these playwrights to reveal how Salesman may have influenced them (Ari Roth contends, "For what writer is immune to the shadow of Salesman?"), the American theater, American audiences, and why Miller's play continues to enlighten, to disturb, and to inspire us. Not only are these playwrights' views a valuable text on Salesman but, in many instances, they form miniature essays that rightfully take their place in the playwrights' own canon.

Edward Albee

All American playwrights who have been around for a long time seem to have one play above all their others that they're identified with—part of a quick and, very often, superficial journalistic check-list. Say Tennessee Williams and you get A StreetcarNamed Desire; say Thornton Wilder and you get Our Town; say William Inge and you get Bus Stop; say Eugene O'Neill and you get Long Day's Journey into Night; say me and you get Who's Afraid of Virginia Woolf?; say Arthur Miller and you get Death of aSalesman.

These "signature" plays are usually very good examples of the playwright's work; certainly they are very popular examples, which may be why they become "signature"; and, sometimes, are the playwright's best, though sometimes it is simply the popularity which tips the balance, leaving in the lurch subtler, quieter, or tougher plays.

No one would question, however, that Death of a Salesman is a very fine play—I leave for a hundred years that injured term "great"—and it is certainly one of Arthur Miller's two or three finest, and may well be his finest—unless he writes a better one.

Like all of Arthur's plays, Death of A Salesman forces us to observe much that we would rather not, consider much that we are less than comfortable with, holds up to us a clear reflection of both our potentialities and our avoidances.

It is a powerful, sad, brutal play, and it has "conscience" written all over it, and probably set a standard for that unpopular word.

Robert Anderson

It makes me feel very old that we are celebrating the fiftieth anniversary of Death of aSalesman . . . but also very young, knowing that something that was created fifty years ago has withstood all the "new waves" which have washed over the theater in that time. I remember being at the opening, where strong men wept, bent over in their seats with their heads in their hands, or standing, applauding wildly.

The critic Louis Kronenberger wrote, "The play is so simple, central and terrible, that the run of playwrights will never dare nor care to attempt it." Brooks Atkinson wrote, "Salesman is one of the finest dramas in the whole range of American theatre."

So it remains.

What Salesman meant to me personally as a fledgling playwright just back from World War II was that it was "there," Arthur Miller was "there" among us, large in stature, large in aspirations. Standing tall.

The night before I was commissioned in the Navy in 1942, I had passed my oral exams for my Ph.D. I think I was passed on the assumption that I would not be coming back. For years I had wanted to be a playwright, but I had studied for my Ph.D. because I am a "belt and suspenders" man and knew that it would be difficult to support myself and my wife as a beginning playwright.

But, miraculously, I had come marching home a playwright. I had won a prize sponsored by the Army and the Navy and The National Theatre conference for the best play written by a serviceman overseas. I had been awarded a Rockefeller Grant, and before my return I had landed one of the great agents, Audrey Wood.

Among the plays I saw soon after my return was Miller's All My Sons. It held me riveted. I had studied my Ibsen. So had Miller. His subject was "responsibility," his method the so-called well-made play.

Then, two years later came Salesman. As John Gassner wrote, "Miller still has a firm hand on the sequence of events . . ." but he had achieved a poetry, a theater poetry, the whole work magnificently realized in the Elia Kazan production with setting and lighting by Jo Mielziner.

Miller was again writing about family, a subject always close to my heart and concerns. Someone once wrote, "drama should provide the opportunity for the most intense, basic human interrelationships. Is there an arena more intense than the family?"

Though Benedict Nightingale, the English critic, has always expressed his contempt for the American playwright's absorption with family and has wondered when we are going to "cut the umbilical cord," still, with Death of a Salesman, Long Day'sJourney into Night, The Glass Menagerie, Awake and Sing and others, we have done very well with the "family play."

Salesman struck yet another sensitive area for me. In my teens I had been deeply moved by Charles Lamb's essay, The Superannuated Man. The man out of work, diminished, out of the job which had provided the meaningful routine of his life. I had first read this essay during the Depression, when men were throwing themselves out of windows in despair.

My father, at twelve, had found himself an orphan on the streets of New York (1889) working in lumber yards, dressed in cast-off clothes provided by the church. He had then come across an advertisement for free courses in shorthand and typing provided by the Underwood Typewriter Company. He started as a stenographer at five dollars a day and rose to become vice-president of a large copper company. Then in that most terrible year of the stock market crash, 1929, he had been "retired." The only work he could get was as a salesman (insurance), and he found himself waiting in the outer offices of company presidents who, only months before, had been his fellow directors, sitting on boards of prestigious firms.

How contemporary Salesman is in this age of downsizing on all levels from laborers to vice presidents (without golden parachutes). The despair, the loss of the feeling of self-worth which overcomes us when we are fired or "retired" from work which has provided us with not only "food on the table" but also a sense of dignity.

This despair, this feeling of worthlessness, is surely a universal experience and will continue to be. And probably fifty years from now, men will be seeing Salesman, and, remembering their father or experiencing the shock of recognition of their own lives, will be sitting in some theater, bent over weeping or standing and applauding. For Miller, in portraying the life and death of Willy Loman, has obeyed his own admonition . . . attention has to be paid.

Kenneth Bernard

Nick Carraway in The Great Gatsby says, "I see now that this has been a story of the West, after all. . . ." By this he means that Gatsby is a story of innocence corrupted, of Westerners possessing "some deficiency in common which made us subtly unadaptable to Eastern life." As Wilson, the desiccated man of the ash heaps, says, "I'm sick . . . I'm all run down . . . I've been here too long. I want to get away. My wife and I want to go West." Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman is of the same paradigmatic order. The opening stage direction makes this clear:

The play ends with the same image:

The grass, trees, music, and horizon are, of course, the elements of the West, the Territory, a locus amoenus, imbued with the magical and mythic qualities of virtue, truth, hope, beauty, freedom, and a horizon co-relative with heaven itself, as so many nineteenth-century landscapes give testimony to. "It's beautiful up there," Willy says vaguely to his wife Linda about his life on the road: "the trees are so thick and the sun is warm." Where, exactly, has he been? To what is he referring? Clearly it is the Territory, not the road on which he sells his line.

Willy Loman, the (not a) Salesman, is another archetypal "Westerner," but in a much abused and debased form, who is unadaptable to eastern life. Instead of a pistol and a horse, he has a sample case and an untrustworthy car. His "territory" is not the open spaces, where a man is a man and his word is better than law, but a series of ash heap settings with layers of corruption, by which Willy has already been compromised (as in his marital infidelities), although he stubbornly clings to other values. His road never goes west. In the East, Willy is "always in a race with the junkyard," both materially and morally. When, as his wife says proudly, he opens up "unheard of territories," it is for trademark products. He is no explorer of pristine wilderness, engaged in heroic and mythic feats, as was the grandfather in Steinbeck's "A Leader of the People," another defeated "Western" type, or his own heroic older brother Ben, who is associated with epic deeds in Africa and Alaska. In Act II, the hallucinatory Ben says to Willy, "Get out of these cities, they're full of talk and time payments and courts of law." Willy himself says to his son Biff, "Go back to the West! Be a carpenter, a cowboy, enjoy yourself!"

The loss of joy in Willy's world is scarifying, mutilating. Willy's fragile "house" in Brooklyn is a virtual last outpost, "boxed in" as a burial vault, dwarfed and deprived of light and horizon by the towering apartment buildings, which represent the new, angular, and cold urban/commercial order. It is Loman's last stand. The street is lined with cars, there is no fresh air, the grass won't grow, and Willy cannot even grow a carrot in his own back yard, which is what the Territory has been ridiculously reduced to, a place where you "gotta break your neck to see a star. . . ." The builders of the apartment buildings have cut down the beautiful elm trees and "massacred the neighborhood." He remembers when there were lilacs, wisteria, peonies, and daffodils. This downward-spiraling litany continues throughout the play. As Willy puts it more than once, "The woods are burning!" That is to say, the transcendental space within which virtue can be naturally constituted and in which happiness and ideal family are attainable is being destroyed, and what is left are the wizened and morally anemic creatures of the ash heaps, the virtual wasteland that is the estate of modern America, where selling, anything, anything at all, is a confirmation of being.

Willy's son Biff, in particular, has absorbed his father's ambivalence. On the one hand, he adores the West, horses, the out-of-doors, working with his hands, and so on. He has also absorbed the common man's Ben Franklin ideal of do-it-yourself expedience, as shown by his numerous correspondence courses. But, on the other hand, he lies, he cheats, and he steals. And just as Willy is regularly called "kid" by his boss, his son Biff, who is thirty-four, says, "I'm mixed up very bad. . . . I'm like a boy." In another incarnation, Biff will be a new type, like Nathanael West's Earl Shoop in The Day of the Locust, a displaced urban cowboy, a sometime hustler and pimp, stranded on cement with a far-away look and maybe a barbershop Indian or dying consumptive for a companion, just as Willy, in a later, less tragic, incarnation might well be, say, an Archie Bunker. In total exasperation at one point, Willy's neighbor and friend Charley says to Willy, "When the hell are you going to grow up?" But neither Willy nor Biff can grow up in the only world they have. Willy's "massive dreams" will not allow them to grow up. They are ambiguously and delusionally enmeshed in a moral universe that has no currency in their world. Willy's concern with growing carrots, which are good for vision, is a desire somehow to see better, to understand the nature of things, to repair the loss of vision in his old glasses, to stay on the road from which he strays suicidally or on which he absent-mindedly comes close to vehicular homicide. But he does not grow carrots or anything else, although he tries with a flashlight in the dark. He just dies, lamenting a broken life and a broken world.

Whether he is his own victim or society's is something to consider. Most likely he is both. So much of American literature is obsessed with what we have supposedly lost in our transition from wilderness and Territory to a city and suburb, from a pastoral-agricultural society to an industrial-commercial one. The two most produced and studied plays in America, Death of a Salesman and Tennessee Williams's A StreetcarNamed Desire, are both about traveling salesmen, no doubt a telling sign. One of them fails and one succeeds. Williams's Stanley Kowalski is the ultimate mercantile man, with no illusions about America's past, as his "rape" of Blanche reveals. And, as his name implies, he is (like Angelo, the mechanic who doesn't understand Willy's Studebaker) part of the out-of-control population in the stinking apartment houses (read tenements, projects) that Willy complains about. He doesn't worry about things like whipped cheese. He has a firm grip on the corruptions of America, and he will succeed (his child by Stella, Blanche's sister, will unite both an old and new America, for better or worse—for example, a mongrel child comparable to the horrible cultural birthing in Hemingway"Indian Camp"). The choice between Willy Loman and Stanley Kowalski for national character is not much of a choice. One is a willing victim, the other an unwilling victim, of a fallen world, although there must be reservations in both cases. Even were Willy less corrupt and Stanley more "sensitive," it still would not be much of a choice, although Stanley is far better than Faulkner's equally mercantile Snopses, who similarly represent the new order's "rape" of the old. (The protagonist of Henry James's The Princess Casamassima, in a different context, reflects a similar problem of old and new and can only kill himself as a solution.) What is clear is that both Stanley and Willy represent a continuing conflict deep in the American psyche, animating much of our debate about how America and Americans (past, present, and future) should be constituted. It is a debate not likely to be concluded soon, although perhaps temporarily occluded by other concerns.

Miller has a lot of sympathy for Willy. Through Willy's wife he proclaims that "attention must be paid. He's not to be allowed to fall into his grave like an old dog," because he is a "human being." Later, through Willy, he says, "a man is not a piece of fruit!" (read "shit"), and again, "a man has got to add up to something." But how much attention, and why? What does Willy add up to? These are important questions. Willy and his sons contribute to the very decline Willy bemoans ("personality always wins the day"). And others, like Charley and his son Bernard, who between them can't hammer a nail but who adapt to a corrupting and dehumanizing system ("When a deposit bottle is broken you don't get your nickel back."), are decent and caring people. What, we can ask, does this mean? At this nexus, Miller does not seem quite clear. A more contemporary political paradigm about the value of Everyman, about Willy as representative of the downtrodden in an unfair and evil economic system, seems to be imposed on another paradigm, one about the conflict between the values of the West and the East, the Territory and the Community. The latter is historically enduring, reflected in much of our history, politics, and literature. The former, although very likely edifying to many, is a point of view, a parti pris, that has little to do with most of the imagery set in motion in the play. A weakness of the preacher-reformer artist is that she lures us to transfer the virtue of her cause to the work at hand. Part of Miller's (and our) moral endorsement of and conferral of tragic status on Willy is the quasi-sanctity of Miller's ideological position—despite the facts he is laying before us of Willy's huge derelictions of character. There is no question that America has come upon hard times, that America, never in a state of grace, has surely fallen away from any possibility of it in its current morass. It is doubtful that paying attention to Willy Loman, in Miller's imposed sense, will help us understand this fall and these hard times. But paying attention to the tragedy of Willy's divided and confused loyalties, his misconceptions and compromises, his pernicious electioneering for false gods, will, I think, help us to understand.

Horton Foote

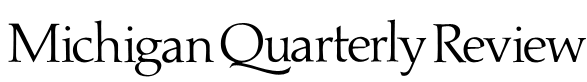

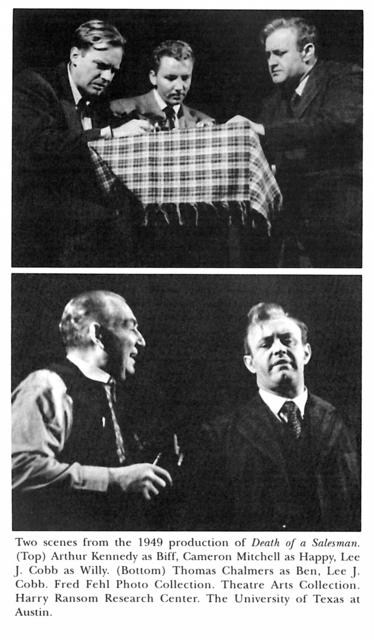

So much has been written of Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman that it is now as familiar to us as an old and valued friend and seems to have been with us forever. I remember a time though when there was no Death of a Salesman, and the year it opened in New York to its dazzling recognition. I saw this celebrated production with Lee J. Cobb and Mildred Dunnock, and later the revival with Dustin Hoffman, and I've read it a number of times as well as read many essays and criticisms of the play.

The real power of the play itself was revealed to me when I was asked by a friend to go and see a production in a small regional theatre in Portsmouth, New Hampshire. Frankly I dreaded going. Hadn't I seen Lee Cobb and Mildred Dunnock both on the stage and television? Did I want my memory of a wonderful evening in the theater spoiled? Reluctantly, I went. None of the actors were celebrated, but from the very beginning all my reservations about going vanished as the power of the play itself took hold of me and the audience, and made clear to me that the play is graced with an elemental power, with the strength and the enduring truth of a parable, and I was as moved at the end of the play as if I had never seen it or read it before. It's a remarkable piece of work and has deservedly stood the test of time.

John Guare

In 1952, my father and I went to the movies. Nothing special in that. He and my mother and I, the three of us, our entire family, loved the movies and went a lot. But this night was different. After dinner, out of the blue, my father stood up and said, "Johnny and I are going to the movies. Just the two of us." Where? To the movie version of that play Death of a Salesman playing down the street from us at the Colony movie theater on 82nd Street in Jackson Heights in Queens. My mother wasn't invited, which didn't bother her because who wants to see some depressing thing anyway with death in the title especially after seeing Singin' in the Rain at the Music Hall earlier in the year which would be our all-time favorite plus we had the new Dumont twelve inch TV so who wanted to go out?

Now I knew all about Death of a Salesman because I knew all about the American theater. I was fourteen. We went to Broadway plays all the time like Annie Get Your Gun, Where's Charley?, Gentlemen Prefer Blondes, Wish You Were Here which had a real live actual swimming pool right on the stage plus a number one hit song sung by Eddie Fisher. I also knew all about Arthur Miller from Life magazine, my main source of information about the world, because I, like Miller, was going to be a playwright, although a funny playwright. That night was really strange because one of the things I knew about him, thanks to all this exciting House UnAmerican Activities Committee McCarthy stuff, was that for all his success Arthur Miller was probably a Commie, and not only that, so was Frederic March, the star of this movie. I knew everyone who was a Commie in show business not only from the priests and nuns at our church, St. Joan of Arc, who would tell us who to watch out for from Red Channels, but also because my father was no less a dignitary than Vice Commander in Charge of Americanism at his American Legion Post: The Elmjack Post #298 which had saluted Hollywood that year for making the kind of movie that should be made, My Son John, directed by Leo McCarey. What a story! A wonderful Irish Catholic mother played by Helen Hayes discovered that her beloved Irish Catholic son had become a Communist. After some—but not that much—hand wringing, Helen did the only thing and turned him in to the FBI. Would my family do that to me if I became a Communist? They'd have to. But luckily I would never become a Communist. So why were we going tonight to this leftie Death of a Salesman? Hadn'tThe American Legion in Boston already tried to shut down this movie as Commie propaganda? The Elmjack Post #298 had decided to let the picture open in New York without protest because why give it the attention. The Commies would like that. So why then were the two of us going? Suppose anybody saw us going into the Colony? How would the Vice Commander in Charge of Americanism explain this one—and taking a kid who could be brainwashed. Wait! Had my father secretly become a Communist? Would I have to turn him in? The night became weirdly illicit. My father bought the two tickets. We went in.

Death of a Salesman was kind of boring. The story kept jumping back and forth in time which confused me. Frederic March drove his car back from Boston the way my father drove—all over the road and panicky. Was it March's rotten driving that made my father need to see this movie? March played a guy named Willy who fought with his sons. I didn't have any brothers. Willy had a girlfriend in Boston. Then Willy killed himself to get insurance and everybody went to his funeral. My father had suffered a heart attack two years earlier. I didn't like this movie one bit. We didn't wait for the double feature. We walked home but this time we didn't talk over the jokes from the picture or re-enact our favorite bits. "I want to tell you something." My father said that in a low tone of voice you use when you're going to break a secret. I liked being told secrets but not from him. Did he have a girlfriend in Boston?

"I once was a salesman."

"Like the salesman in the movie?"

"No, for Procter & Gamble."

"Ivory soap!" I was very impressed.

This is what he told me.

When World War One, the war to end all wars, was over, my father came back not to New York but to L. A. to start a new life working as a soap salesman in a section called Angel's Flight which was a street on a hill so steep you had to take a cable car to go up and down it.

"You worked for Ivory soap and we could live in L. A. in a place called Angel's Flight. Why aren't we there now?"

My father who worked down at Wall Street and hated it said this in a low slow voice. He tended to mumble anyway so you always had to get close to hear him. "It hadn't worked out." That was it. We walked home in silence.

My mother asked how was the movie? My father said in his bright chipper voice, "The usual Commie propaganda." While he brushed his teeth, I whispered to my mother what my father had told me. "He lived in L. A.?" she said. "He was a salesman for Ivory soap? Then you know more about him than I do."

One thing I did know was that the secret he had just told me was directly connected to the story we had just seen. And seeing that story had somehow made it possible for him to say to me those four terrible words: It. Hadn't. Worked. Out. That night on the walk back from that movie was the only time he ever mentioned that part of his life. If I brought it up later, he'd laugh it off with a song or a joke or a drink. By the time I could've brought it up and pushed it, he had died. But something happened that night. I saw for the first time that a play, a movie that had been a play, something with actors in it, could touch a man as familiar as my father with such mysterious power that it made him a stranger to me and gave him strength to reveal—not a secret—What was it he had told me? Something deeper than a secret. But the play had given him courage to say the most horrible words he could imagine: It. Hadn't. Worked. Out.

T. S. Eliot in his great essay "Tradition and the Individual Talent" writes about the last time the artist was a full-fledged member of the establishment society. In Shakespeare's day, people went to the theater for the same reasons you'd go to the doctor today. Audiences went to the Globe Theater to see their problems acted out. Seeing emotions carried to the extreme helped audiences find the proper limits for their own lives.

Did my father go to see Death of a Salesman in this instinctual primal Elizabethan way—although he wouldn't know what the hell that meant if you woke him out of his grave today with all the knowledge in the world. He knew if he saw this story the psychic pain of his life would be—what? forget about healed. Eased. Settle for eased.

Is this what accounts for the universality of Miller's work? His ability to get into people's dreams, to touch their disappointment, to give voice to the American shame of failure, to make that which is most human in us also the very same thing we can least bear to acknowledge? To say Yes, I have been heard. I am not alone. No matter where we are on this planet. Did what my father tell me that night heal him in some way? Did he pay some debt to his only child in this meager confession which haunted him for a lifetime? He never got to that place again. But some debt was paid that night, some dent made that night in the fragile armor we invent to survive, walking home that night in 1952.

A. R. Gurney

What most intrigues me about Death of a Salesman, and indeed about many of Arthur Miller's other plays, is the thematic ambiguities at the core of his work. We all value his solid architecture, his driving moral energy, his sardonic wit, and his ability to seize on subjects which manage to forge disparate audiences into responsive communities all over the world. Yet it would be a mistake to view the playwright simply as a passionate polemicist.

Death of a Salesman, for example, is generally acknowledged to be a major indictment of American capitalism and consumerism. Willy Loman's story dramatizes the heartlessness of a system which seduces and exploits and then casts aside its most devoted supporters. Yet the Bernard subplot embodies almost the opposite position. Here the point would seem to be that if you work hard and play by the rules you can end up arguing a case in front of the Supreme Court, and enjoy a good tennis game on the side. Obviously both plot strands work with and against each other. Willy Loman's story, standing by itself, would be a grim and limited distortion of the American experience; Bernard alone would seem as false as Horatio Alger. Woven together, however, each strand informs and modifies the other, so that at the end we embrace a much more complicated vision of our country and ourselves.

This ability to defy the laws of physics and occupy two places at the same time is what good art can do so compellingly. And it's what makes Miller a major artist. In TheCrucible, for example, he manages to chronicle the horrors of what happens to a community when pent-up feelings are expressed publicly, while at the same time exploring how unexpressed feelings can undermine a marriage. In The Price, he looks at the price we pay when we cut ourselves off from our roots, juxtaposed with the price we pay when we elect to stay home. In an underestimated recent play of Miller's called The Ride Down Mount Morgan, the central character is a bigamist, whose two wives show up in his hospital room after an automobile accident. Talk about two opposing positions occupying the same place at the same time!

In any case, Death of a Salesman, for all the power and passion of its politics, and the groundedness of its domestic detail, has at its center this complex sense of ambiguity, which, I believe, will intrigue and move audiences far removed from the particular concerns of this country or century.

David Henry Hwang

Death of a Salesman is the best play yet written about an American immigrant family. Granted, the Lomans never reveal specifically the country in which Willy was born; they don't speak English with an accent or revel in colorful old-country customs. Nonetheless, the moment I first read the play, I recognized in my bones an immigrant household, for in Willy's desperate quest to hold onto the American Dream, I heard the voice of my own father. Immigrant patriarchs often embrace American sloganism in order to justify the radical choice they have made, for the pain of uprooting must surely be rewarded with a better life or else it is a fool's choice. Note also the play's obsession with travel: not only is Willy himself a virtual road map of American territories, but his role model Ben ends up in Africa, where he makes his fortune. Ben's advice to Willy is the slogan that has inspired American immigrants for generations: "There's a new continent on your doorstep, William. You could walk out rich. Rich!"

The Loman boys also represent familiar responses of second- and third-generation Americans, who, burdened with a more intimate knowledge of this country, must choose to endorse or reject immigrant romanticism. Happy's need to prove that "Willy Loman did not die in vain" suggests all second-generation Asian Americans currently becoming doctors, lawyers, engineers, and other upwardly-mobile citizens, in part to fulfill the dreams of their parents. On the other hand, Biff's conclusion that "He [Willy] never knew who he was" tells of the loss of identity and cultural confusion often brought on by rapid assimilation.

Though I am virtually certain Willy is an immigrant, I do concede a potential contradiction in the play, when he and Ben discuss their childhoods . . . in South Dakota. Could this be Willy's delusion, his need to be accepted as an American so great that it forces him to invent a false past? Possibly. Or perhaps immigration is so intrinsic a part of the American character, has so shaped the dreams and slogans of this land, that no true examination of the national spirit can escape its pull. All evidence to the contrary, I will always remain convinced that Arthur Miller has written the great American immigrant play. That the Lomans are a typical Asian American household. That Death of a Salesman captures, of course, my own family.

Adrienne Kennedy

When I saw Death of a Salesman in 1949 I was most struck by the fact that Willy Loman could assess his life and through reflection and memory he could arrive at insights and great conclusions. And in his car after doing this he could die.

He wasn't a character in Shakespeare or Shaw but an ordinary man who nevertheless possessed the right to make such a monumental decision.

I believe it was then I decided, if my memory one day ever presented me with agonizing insights, that I too possessed that right. I found this thought a comfort. And it's why I still love Willy Loman fifty years after.

Tony Kushner

I sat behind Arthur Miller at the 1994 Tony Awards, and I stared at the back of his head—far more interesting than anything transpiring on stage. Inside this impressive cranium, inside this dome, I thought to myself, Willy Loman was conceived: for an American playwright, a place comparable in sacrosanctity to the Ark of the Covenant or the Bhodi Tree or the Manger in Bethlehem. I wanted to touch it but I thought its owner might object. The ceremonies ended, and I'd missed my opportunity to make contact with the cradle whence came one of the three postwar pillars—the other two being of course A Streetcar Named Desire and Long Day's Journey Into Night—upon which the stature of serious American playwriting rests. All the wonderful writers who followed the Triad—realists, naturalists, and experimentalists—have at least these three plays in common. Nothing that American theater can point to with pride since the decade which produced these works was not shaped, in some degree, by their influence, in homage or in opposition or, more frequently, both. A salesman, a streetcar, and a journey: three ambient testaments to rootlessness, to American wanderlust and the hazards of nomadism. Death, Desire and Night: tragedies all, downers embraced by a country of people who like to imagine themselves, perversely, as relentlessly upbeat. Bertolt Brecht in his journal wrote that American theater is written "for people on the move by people who are lost." And that insight before the Big Three had been written or staged!

We think American drama apolitical because the Big Three are family plays. Except of course Streetcar is about a family in which a woman who cannot operate within conventional economies is raped. Journey is about a family of immigrants haunted by poverty and class. And the Lomans are compelled by the tide of history to return East from a paradisaic pioneer frontier past; the motion of Manifest Destiny has reversed itself, an acid reflux which had carried Gatsby from Chicago to Long Island twenty years before, brings the Lomans to a doomed pursuit of happiness in the place whence happiness, in the previous century, had fled—Happiness having Gone West and never returned, drowned perhaps in the grips of some Pacific undertow.

We think American drama mired in naturalism, lacking formal inventiveness and playfulness, but Journey is an extremely artificial play about the theater, full of actors playing actors and the victims of actors. Streetcar is great verse drama, as close as we'll ever get, close enough, its characters unforgettable because they speak a language that's as "natural" as any great poetry is—which is to say, not in the least. And Salesman has Uncle Ben, whose wealth has made him as alien to the Lomans' struggles and disappointments as the character is, formalistically, to the rest of the play.

I saw Salesman when I was six years old, and I never forgot Uncle Ben and his line, "When I went into the jungle I was eighteen years old and when I came out, by God, I was rich!" I don't think I understood the entire story, but in the kaleidoscopic version I subsequently constructed for myself I thought Uncle Ben some sort of great clown who blows open the Loman quotidian bearing tidings of fun, spontaneity, adventure, life,—of which, apparently, menace and real danger were constitutive elements. I didn't, at six, know much about the quotidian. No six year old should know anything about the quotidian. But I think perhaps watching the Loman family love and wound one another, and love and be wounded by the world without, was the first indelible inkling I'd consciously had (lucky child!) of what the Everyday was, that such a monstrous thing existed; and how important it is to despise the Everyday, to live one's life, to the extent one can, resisting it.

Salesman is not only a play about death, though its sadness is overwhelming. It is also about resistance, even unto death. I have never believed that the issue of inexorability ought to be resolved in tragedy. A tragedy in which suffering and death are truly inexorable lacks drama; there needs to be a what if, a possible escape, or else the whole thing becomes grimly mechanical, pathetic, not exhilarating, grotesque rather than cathartic. "We're free," Linda keens over her husband's grave. The words in their mortal/mortuary context are heartbreaking, horrible, ironic and deeply true of human beings even in inhuman circumstances. We are free, and that fact is both insufficient, as freedom in isolation always is (which I think is a point of the play), but terribly important and true.

Linda Loman's graveside lament, from that Lake Charles, Louisiana, production in 1962, is what made the biggest impression on my six-year-old sensibilities. This is not surprising, given that my mother, Sylvia Kushner, was playing Linda. She was a wonderful actor, a tragedienne. A professional bassoonist, she was drawn to and felt entirely at home in dark, somber tones, in elegy and minor keys, in sorrow. She was honest on stage, she saved a good deal of her truthfulness, the things she couldn't say in the course of the quotidian, for her music and for the roles she played. She kept the lid on a lot of unhappiness, into which she could tap when she needed to. On stage, grief and rage and pain added years to her looks. As Linda Loman she changed from my beautiful young mother (dressed more dowdily than she ever did in real life) to an old woman in the course of the evening. It was terrifying and wonderful; I was anxious to see her afterwards, to see what she'd look like, if she'd become my mother again. She did change back, but I don't think I ever saw her the same way again. Perhaps having spent several weeks being married to Willy Loman, she never was the same.

This was the first time Lake Charles had seen theater-in-the-round, a spatial innovation the advocacy of which caused the more progressive members of the local community theater to split off from the more established Little Theater, to form a company committed to producing plays as controversial as Salesman then was. I remember being amazed that I could watch the action and the audience opposite me, all of us watching my mother play Linda Loman, seeing Brenda Bachrack, one of my mother's best friends, crying at the play's genuinely devastating, lonely, cemetery ending. I was very impressed.

The actress who played Willy's floozy in Boston had broken her arm two days before opening and sported a big plaster cast. I thought the cast somehow connected to what made the hotel room scene so sleazy, had something to do with why Biff and Willy were so angry with each other. I didn't know the meaning of the hose the boys find at the beginning of the play but I knew that it was incredibly ominous, and I certainly knew—had I ever really considered death before?—that when Willy leaves at the end of the play, it's a final exit; I knew it broke my mother's heart.

I saw her play several other parts when I was very young, all of them involving the shedding of tears and the venting of rage, none of them Linda, none of the plays Death of a Salesman. Since then I've seen maybe half-a-dozen Linda Lomans, only Mildred Dunnock as good as my mother; I've seen Lee J. Cobb's beaten titan and Dustin Hoffman's indestructible rat-terrier. But how do I know Salesman is a very great play? Because I knew it when I was six. I didn't know precisely what I'd just seen, but I knew I was in the presence of a great mystery: the sorrow experience brings to innocence, the anger injustice brings to the just. Reading Salesman today, I'm still in its presence, I know it still.

Karen Malpede

"Everybody's Father"

The first, and come to think of it, only time I ever saw Death of a Salesman was in a college production at the University of Wisconsin. I remember straining forward in my seat, my knuckles white, gripping the armrests on both sides. The play is so much a part of the American ethos that whether or not one has seen it or read it ever or dozens of times, Miller's sensibility is as if implanted in our heart/brains. My own father was not a salesman, but a certified public accountant. Not a Loman, but the son of Italian immigrants, who had worked his way out of a reactionary Catholic ghetto, married a Jewish woman, moved to fancy suburbs and died at the age of forty-four. He was, I always thought, like Willy, a victim of the American Dream. "Attention must be paid." Miller was a young playwright on the Federal Theater Project. He is the direct descendant of a time in American history when theater felt it had both a right and a duty to speak to the citizens of a democracy about our role as the makers and safe-guards of the society in which we live. Miller wants the middle classes to be responsible. He knew that upward mobility and assimilation might sap something finer in the nature of a people of immigrants who suddenly, because they had defeated fascism, could become globally rich and powerful. Rightly so, in All My Sons he critiqued the isolationism of the nuclear family. I like the fact that he intertwines personal sexual longings with public ethical dilemmas. I appreciate Miller's honesty, his courage, and his sense of citizenship; his secular Jewish belief that through human action the social world might become a better place, and his conviction that dramatic fiction has a role to play in this worthwhile endeavor. If, as a playwright, I claim Susan Glaspell and Gertrude Stein as mothers, I also lay claim to Miller as one of the great and good fathers of us all.

Emily Mann

I heard about Death of a Salesman when I was a child, eight or nine years old, before I had ever seen a play. My Uncle Phil, my father's oldest brother, was a businessman in what we used to call the "shmatte business," in New York City. He manufactured knit shirts. He was a gruff, perpetually angry man educated only through high school, a man who grew up tough on the streets of Brooklyn. We children were often scared of him.

One night at dinner he told the family about a play he'd seen. This play was called Death of a Salesman and he told us it had hit him so hard he couldn't drive home that night to Long Island. He and his wife, Claire, had to take a room in a hotel. I asked my aunt about this years later, and she said, "Oh, yes. Phillie could barely walk out of the theater, so we had to stay over in New York."

Two things hit me as a young girl:

1) My uncle wasn't as tough as I thought he was.

and

2) Theater must be a pretty powerful thing.

Mark Medoff

Reading Death of a Salesman in my Introduction to Theater class, freshman year, University of Miami, 1958, ranks as a seminal moment in my life. In terms of what the aspiring eighteen-year-old writer learned about the possibilities of structure, it ranks with The Sound and the Fury, Wuthering Heights, "The Waste Land," and Waiting for Godot. In terms of the emotional impact of Mr. Miller's play—simple: nothing—nothing!—since has hit me so hard.

Jason Milligan

Arthur Miller's plays have been a major influence on me since the first moment I discovered them. Not just his most famous works, but also his newer, lesser-known plays continue to amaze, fascinate, and challenge me both as an individual and as an artist.

The first Miller play I ever saw was a college production of Death of a Salesman, and even though the play was glaringly miscast (a strapping young Hispanic graduate student as Willy Loman), the poetry, power, and passion of Miller's work still shone through, hit me hard, and have stayed with me ever since. Thankfully, I was later able to see Broadway revivals of Salesman and many other Miller plays—and I continue to be astounded by the depth of humanity in his writing.

Personally, I have always been fascinated by The Big Moral Questions in life and drama—and that, I believe, is one reason Miller's plays have always resonated so strongly for me. So few writers bother to contemplate the nation's (or world's) moral barometer in their plays anymore, and I believe one reason Miller's plays continue to remain so timely is because they serve a primal function of the theater: to hold a mirror up to our souls, to be the moral conscience of our times. On top of that, Miller has crafted some of the most original, fully-developed characters in American drama. What more could one ask for in a play? You can't. Arthur Miller has already given you everything.

Fifty years and still going strong . . . congratulations to you, Mr. Miller! And thank you for inspiring several generations of playwrights with your vision.

Joyce Carol Oates

Was it our comforting belief that Willy Loman was "only" a salesman? That Death of aSalesman was about—well, an American salesman? And not about all of us?

It's probable that, when I first read this haunting and mysterious play at the age of fourteen or fifteen, I may have thought that Willy Loman was sufficiently "other"—"old." He hardly resembled the men in my family, my father or grandfathers, for he was sales" and not a factory worker or small-time farmer, he wasn't a manual laborer but a man of words, speech—what his son Biff bluntly calls "hot air." His occupation, for all its adversities, was "white collar," and his class not the one into which I'd been born; I could not recognize anyone I knew intimately in him, and certainly I could not have recognized myself, nor foreseen a time decades later when it would strike me forcibly that, for all his delusions and intellectual limitations, about which Arthur Miller is unromantically clear-eyed, Willy Loman is all of us. Or, rather, we are Willy Loman, particularly those of us who are writers, poets, dreamers; the yearning soul "way out there in the blue." Dreaming is required of us, even if our dreams are very possibly self-willed delusions. And we recognize our desperate child's voice assuring us, like Willy Loman pep-talking himself at the edge of a lighted stage as at the edge of eternity— "God Almighty, [I'll] be great yet! A star like that, magnificent, can never really fade away!"

Except of course, it can.

It would have been in the early 1950s that I first read Death of a Salesman, only a few years after its Broadway premiere and enormous critical and popular success. I would have read it in an anthology of Best Plays of the Year. As a young teenager I'd begun avidly devouring drama; apart from Shakespeare, no plays were taught in the schools I attended in upstate New York (in the small city of Lockport and the village of Williamsville, a suburb of Buffalo), and so I read plays with no sense of chronology, in no historic context, no doubt often without much comprehension. Reading late at night when the rest of the household was asleep was an intense activity for me, imbued with mystery, and reading drama was far more enigmatic than reading prose fiction. It seemed to me a challenge that so little was explained in the stage directions; there was no helpful narrative voice; you were obliged to visualize, to "see" the stage in your imagination, the play's characters always in present tense, vividly alive. In drama, people presented themselves primarily in speech, as they do in life. Yet there was an eerie, dreamlike melding of past and present in Death of a Salesman, Willy Loman's "present-action" dialogue and his conversations with the ghosts of his past like his revered brother Ben; there was a melting of the barriers between inner and outer worlds that gave to the play its disturbing, poetic quality. (Years later I would learn that Arthur Miller had originally conceived of the play as a monodrama with the title The Inside of His Head.)

In the intervening years, Willy Loman has become our quintessential American tragic hero, our domestic Lear, spiraling toward suicide as toward an act of selfless grace, his mad scene on the heath a frantic seed-planting episode by flashlight in the midst of which the once-proud, now disintegrating man confesses, "I've got nobody to talk to." His salesmanship, his family relations, his very life—all have been talk, optimistic and inflated sales-rhetoric; yet, suddenly, the powerful Willy Loman realizes he has nobody to talk to; nobody to listen. Perhaps the most memorable single remark in the play is the quiet observation that Willy Loman is "liked . . . but not well-liked." In America, this is only B+. It will not be enough.

Nearly fifty years after its composition, Death of a Salesman strikes us as the most achingly contemporary of our classic American plays. It has proved to have been a brilliant strategy on the part of the thirty-four-year-old playwright to temper his gifts for social realism with the Expressionistic techniques of experimental drama like Eugene O'Neill's Strange Interlude and The Hairy Ape, Elmer Rice's The Adding Machine, Thornton Wilder's Our Town, work by Chekhov, the later Ibsen, Strindberg and Pirandello, for by these methods Willy Loman is raised from the parameters of regionalism and ethnic specificity to the level of the more purely, symbolically "American." Even the claustrophobia of his private familial and sexual obsessions has a universal quality, in the plaintive-poetic language Miller has chosen for him. As we near the twenty-first century, it seems evident that America has become an ever more frantic, self-mesmerized world of salesmanship, image without substance, empty advertising rhetoric and that peculiar product of our consumer culture, "public relations"—a synonym for hypocrisy, deceit, fraud. Where Willy Loman is a salesman, his son Biff is a thief. Yet these are fellow Americans to whom attention must be paid. Arthur Miller has written the tragedy that illuminates the dark side of American success—which is to say, the dark side of us.

Oyamo

On what Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman means to me, an enraged 21st Century Africamerican male:

Salesman means that American theater intellectuals and their scholarly counterparts should rid themselves of their insufferable inferiority complex toward European theater. Enough of this subliminal colonialism! Enough of this snide, elitist derision and aesthetic conformism that attends discussions of American Theater! Had it been left to those blustery, nattering organizers of aesthetic bureaucracies that are clogged with semantic semiotics, we Americans never would have invented jazz. Miller teaches me that the American "Revolution" is not over yet; we won only the military victory; otherwise we are yet colonized. Miller makes me remember that being "black" in America is to be in a state of constant rebellion, and, as such, I exempt myself from the notion of American cultural inferiority.

Salesman is a great 20th century play about universal human suffering which is caused by the pervasive malady of "moral ignorance." Miller had no ancient American (Caucasian) legends and myths upon which to draw when he wrote Salesman; he invented his own, as Americans are wont to do. In Salesman he gave us an in-depth glimpse at the highly infectious "disease of unrelatedness," American-style alienation and despair in the common man, the Everyman who faces the limitless possibilities of America and dares to dream and fail.

Willy Loman finally failed because he couldn't escape the self-invented myths of his idealized past. Miller purposefully blurred the lines between expressionism, as he learned it from the Germans, and realism. He did this because he wanted us to see the confused "process" of Willy's mind and to reflect perhaps on the confusion of moral values in the modern industrialized Western world. Nations also invent myths about their pasts.

Miller is inventing the American Theater. Salesman is an exceptionally strong foundation stone. We can be proud to call him our own. We needn't look overseas for approval of what we do in our American Theater. We needn't aesthetically measure ourselves by 2500 years of someone else's history. Why shoulder Europe's calamity-ridden baggage? America is the world now. Everyone in the world comes here to settle, and they export our culture to their homelands. I think those Europeans who condescend toward us are fearful that we Americans will culturally obliterate them. Well, that may be a justifiable fear, but that's their problem, not ours.

Ari Roth

"So Many Memories"

In the contemplative stages of writing this homage, I lost my job. I lost it at Arthur Miller's alma mater which, as it so happens, is my alma mater too. It was a modern-day mugging—no police reports to be filed—a paper decision; a corporate farewell. Following nine years of service, the pro forma phone call—"Thanks for the labor; we've completed our search; you came in second; we'll keep your program; oh, we can help pack your office." I was scheduled to speak at a high school awards ceremony the next week. I'd planned to talk about Miller anyway. For the confluence of an awards ceremony with a 50th anniversary had recalled an earlier commemoration—this one marking the half-century birthday of the University of Michigan's Avery Hopwood Awards, when I received my first literary prize from Mr. Miller himself back in 1981. My dad had taken the Amtrak up from Chicago to watch the ceremony, to bear witness to the leave-taking; this Oedipal movement from one influence to another. I told the high school students of the thrill of meeting Miller that day; of his presenting me with a $400 check for a 13 page play; and then—welcome to the world of Art, kids—of the sting upon reading the contradictory comments from the two national judges; the acerbic dismissal made by playwright-historian Martin Duberman who disagreed with the praise of the other judge (whose name, naturally, escapes me), that my one-act was "imitative of Miller's The Price," which, of course, I had yet to read, but which, in turn, of course, I would. And so a connection had been forged; a connection born of common heritage and total coincidence. I embraced and imbibed Miller's influence, bought The Price for my mother on her birthday and announced that I was no longer going to be a lawyer but a playwright.

I mythologized Miller way out of proportion, perhaps due to the uniqueness of the man himself: the beguiling convergence of physical attribute, moral authority, and private proclivity. For here was a man whose face, as etched in that 50th Anniversary Hopwood poster lithograph, half-turned, half obscured by shadow, with stern jaw, craggy frown and endlessly sloping forehead, summoned images of a literary Mt. Rushmore. As he strode to the Rackham Auditorium podium that afternoon, I was reminded of his carriage—a tall Jewish man—and how often did one see a tall Jewish man in the Midwest? A lanky Yankee Bronx Jew with the wing span of a Phil Jackson and the rough-hewn hands of a working stiff—the kind of laborer he once had been and would always remain—a maker of things—a builder of furniture; of houses in which actors could live. The texture of work seemed to permeate his being and was one he would lovingly celebrate in A Memory of Two Mondays—his tenure as a shipping clerk, where he spent two summers as a teenager during the Depression before taking off in the fall for the University of Michigan. Inspired (and in a hurry) to emulate, I too found work as a shipping clerk in a steel pipe manufacturing plant that very same summer, and then wrote about it, and then submitted it to "the Hopwoods" my senior year.

Miller's work—with its fierce critique of the ravages of a brutally competitive, market-driven economy, his call for a more expansive consciousness imploring that we be responsible not just to ourselves and our families but to our community, to our nation, to the soldiers who fight overseas to defend us and who are just as much blood relation as our own sons—moved me to see him as a kind of theatrical rabbi (albeit, Reform, in the classical sense). Or better yet, a fusion figure, uniting the pulpit, the bench, the lectern, and the spotlight. He had been married to Marilyn after all. And John Proctor had had an affair. A hero could have sin on his hands, lust in his heart, and still wage a moral war. One could indict and not be above the fray but part of the muck. It was, and remains, a populist critique, never a priest's sanctimony.

And so I rally (defensively, perhaps?) whenever Miller is assailed as a moralizing scold, out of step or date. And there are plenty of snipers out there, make no mistake. When our most ambitious playwrights of the moment rush to dismiss, in print, any suggestions of influence that Salesman might have on their own grandiose structural designs, I take it as a personal affront. (Does Miller even care? Yet still I scold, "Attention. Attention and respect! Pay up!") For what writer is immune to the shadow of Salesman? The personal downfall as social indictment; the elegant movement from objective to subjective; from present to past. Only the cold, ideologically driven could turn his back on the pain of a father and son separated by disappointment.

What I know to be true is this: That Salesman was the first play to ever move me to tears. That it was the only show that's caused me to touch a perfect stranger on the arm during intermission. And that it's still the play that comes most readily to mind—to the heart—whenever one fears for one's place; when one loses one's way, or one's job. Salesman is there for us in manifold moments. Whenever we falter, when we feel the earthquake, when we bluster or pose or plant seeds in the moonlight. The achievement of Salesman is one of exposing vulnerability at every stage of life.

Even as a twelve year old, I knew this in my bones. I wasn't much of a reader growing up, but I bawled when I read my homework assignment in seventh grade. I was at Camp Chi in the Wisconsin Dells with my family for an American Jewish Congress retreat. I went out in a rowboat and began to read the gray and yellow covered paper-back with the picture of a man in a raincoat and a suitcase full of samples under a streetlamp. Floating in a lily-pad covered lagoon, I cried for a man who said to his Uncle Ben, "I have a fine position here, but—well, Dad left when I was such a baby and I never had a chance to talk to him and I still feel kind of temporary about myself." The line rings with the shock of recognition even still. This unfillable void that Willy seeks to stuff with ephemera—this son who can't reach his father, his unutterable longing, expressing love through car wax, despair in a broken fan belt, guilt in a flute that leads a man backwards, forever backwards, to the point of his undoing—to the moment where son unmasks the father and is not made free by the discovery. Somehow I understood all that, floating in a pond in Wisconsin all those years ago. Even though my dad's not in retail, I still saw tons of him in Willy. And now I see much more that is me. With a spot on my hat, I've felt alone in the blue riding on little more than a wing and a prayer, the people not always smiling back.

Remarkable how Miller's lines keep coming back. "A man is not a piece of fruit," I told the high-school assembly, and the weight of that moment in the hall was of a concern not just for one itinerant lecturer, but for a class of humanity that, at least for a moment in time, becomes dispossessed. I told the students of Miller's cautionary words; and of the caution in his example. And that despite the romantic figure he cut, how he went out of his way that Hopwood afternoon in 1981 to urge us not to go into theater ("Your lives will only be filled with pain and misery!"). It was a warning that came with a wink. He knew of the great good to come from work that is difficult, of the catharsis to come from crisis. In Death of a Salesman, Miller pays attention and respect to the ways in which we founder, and we are made wiser and more aware for the showing. So moved, we touch a perfect stranger on the arm at intermission; we cry in rowboats in the middle of Wisconsin; we know what links us each to each: a kindred sense of longing and pain. With spots on our hat, our fathers stumbling on the path before us, we, like Biff, are able to find our footing. We regain the road. Thanks to Miller's towering, humble play. Happy birthday, Salesman.

Joan M. Schenkar

Death of a Salesman, along with Karel Capek's R.U.R. and Eugene O'Neill's The HairyApe, is centrally lodged in my earliest memory of theater. And that is because I was able to read it—that is, to speak it to myself—in an anthology of literature that must have come down to me from a college-going cousin. Because fewer plays are now being published, fewer children will have the experience of making their own relationship with a play before it is interpreted for them on a stage. I remember Death of a Salesman much better for having read it before I saw it.

I was very young when I first looked at the play—perhaps eight or nine years old—and my father was still a kind of traveling salesman himself—so of course the work struck me with the force of a blow, as it continues to do when I read it now. I think it is the only complete tragedy—in loosely classical terms—in the American language and certainly the only one to put a kind of Lear and a kind of Fool in the same body. And it is the only play I can think of to turn a stock figure like "Linda the maltreated wife" into an immensely dignified and personalized chorus of praise for her husband—"attention must be paid"—and get away with it.

Death of a Salesman gives full expression to the dreams and disillusionments of my grandparents' and parents' generation—a purchasable democracy in which being "well-liked" meant, inevitably, being "well-fixed" and success always seemed possible in the antipodes. Because itsuch a good play, written to the rhythms of its subject in language that lasts, it also perfectly exposes What Troubles Us Now—and Willy Loman's obsession with surface instead of substance seems particularly apropos.

Death of a Salesman may be middle-aged, but it is still large-hearted and full-bodied and will, I think, continue to play on the world stage as long as American dreams do.

Neil Simon

I was a young man when Death of a Salesman first appeared on Broadway, and as yet had no aspirations to be a playwright. My parents first saw the play and since my father was a salesman himself, one can understand why he was so anxious to see this event that all New York was talking about. My parents were not really theatergoers except for an occasional breezy musical that my father thought a prospective buyer for his garment center wares might get a kick out of. The costly tickets didn't always guarantee a sale for my father, but since his jokes were wearing thin, he could always use some help from professionals.

I remember vividly the night my parents came home from Mr. Miller's play. I never saw my father so excited, so animated, far more stimulated than he had ever been as seen through my teenage view.

"It was so real," he began. "So honest, so truthful. I knew everything this salesman was going through. It felt so much like my own life."

"Well, what was it about?" I asked with enormous curiosity.

"It's about this hard-working salesman and his two lazy sons."

Since my father had two sons, me and my brother, the impact of his insult took a few moments for me to feel the weight of it. I was a teenager in school and my marks did not indicate any reason to be lazy. My brother was in his early twenties and had ideas for his future other than following my father's footsteps into the garment center. He wanted to be a writer and go to Hollywood, an occupation no loftier in my father's mind than becoming a gangster. My brother had girls on his mind which qualified him as being a "bum" in my father's narrow-minded estimation.

When I finally saw Salesman, a year or so later, I saw how my father had twisted the story in his mind to fit his own personal scenario, making my brother into the two brothers he saw in the play, and laying the blame for his own lack of accomplishment on his two wastrel sons. Not exactly Willy Loman, who perhaps put too much faith in his older son's ability to become a huge success, thus bailing out Willy's failed dreams by moving the spotlight of responsibility on to his reluctant offspring.

I think many people who saw the play saw it through their own subjective view, that Mr. Miller was telling their story and not necessarily the one Mr. Miller had in mind. It made no difference. The play's purpose, as all plays' purpose should be, is to make an impact on the audience's emotions, their psyches, their own sense of being, whether failed or otherwise. No play in my memory ever left such an impact on those who saw it.

I have never gotten Death of a Salesman out of my mind and probably never will. In fact, it's the one play that almost kept me from becoming a playwright. It's this play that I measured my own young capabilities against and I knew that that was one mountain too high to climb. Instead, I used it to my own advantage as I made it the one play to aspire to. If I only made it two thirds to the summit, I would have achieved more than I ever dreamed of.

Jean-Claude Van Itallie

Arthur Miller, benevolent patriarch of American playwrights, deserves our homage. His Death of a Salesman opened ways to write many of the plays which followed it, both mainstream and experimental.

Salesman was, for its era, radical in form—time shifts back and forth, place changes continually—yet the spirit of Aristotle's unities is preserved. No matter the many unusual theatrical paths we are led down during the action of the play, we feel secure in the hands of the writer. To playwrights experimenting with form, Salesman teaches that if you're clear and confident in intention and know how to express that intention, the audience will follow, whatever the shape of your play.

Salesman is classic, however, in its themes, and in the subtle, thorough way Miller explores them. Irreconcilable conflicts between fathers and sons, questions of right and wrong, are raised also in Greek tragedy. But Willy Loman (Low man) is not, like, say Agamemnon in Aeschylus, larger than life.

From Salesman we learn that titanic conflicts may be embodied in finely etched contemporary characters somewhat like our imperfect selves, much smaller than gods yet living, in the deepest sense of the word, tragic lives.

Ultimately, as in Chekhov's major plays, I am moved in Death of a Salesman by the characters in their hopeless situations, by the playwright's depth of feeling for them, and by the unflagging quality of his attention and his craft.

Lanford Wilson

This brief tribute was given at the presentation of the Last Frontier Playwright Award to Arthur Miller during the Fourth Annual Theater Conference of the Prince William Sound Community College in Valdez, Alaska, on August 18, 1996.

I can pinpoint exactly the moment I fell under the spell of the theater. Not "In love with the theater," anyone can fall in love. You have to witness the potential of something to fall under its spell.

Each year the high school freshmen of Ozark, Missouri, travel north the twelve short miles to Springfield to attend a production of Southwest Missouri State University's theater department.

S.M.S.U. is famous for its excellent drama department. In 1951 their major production was Arthur Miller's Death of a Salesman.

The curtain rose on Miller's play, the first adult play I had ever seen. The set was stunning. The second story roof of the house was outlined, a thin black line indicating the pitch of the gable, above the room where two brothers slept. Below that was the kitchen of the ground floor.

But the house was dwarfed by giant brick apartment buildings that had arisen on either side. I had lived in Springfield, Missouri, in such an apartment house. My bedroom window looked down on just such an anachronism of a house.

As the Salesman talked (the most natural talk I had ever heard on stage, yet something elevated into speech that was way beyond natural), he remembered when he had moved his family to his house—when the house was new and in a neighborhood of such houses. And as he remembered, I gasped as the sooty apartment buildings faded away, faded into the towering maples of the Salesman's memory. The neighborhood as it had been years ago.

In that moment I realized that in films this effect is merely a cross-fade. But on stage, in this moment, it was a miracle. It was magic. In films it merely takes us to another place. On stage it takes us into the Salesman's mind. It took me to a place where I had never been. I wanted from that moment to be a part of this miraculous medium.

But something else was happening, something larger, and to a fourteen year old, something much more disturbing. Yes: While the Salesman was spinning his beautiful dream, I knew that this clarity and beauty were not going to materialize. This was his idealized dream from the past. The ugly apartment building looming over his house was the reality. There was something in the Salesman that was going to prevent his dream from happening.

I had learned that this was the basis of tragedy, and was thrilled to see that such a story could be told about people, common people, today. But this wasn't all the author was doing. He seemed to be saying that there was something flawed also in thedream.

This was something a kid from a middle-class Missouri Republican household had never heard. And I had certainly never known that social criticism and a tragic personal history could be told, simultaneously and compellingly, in a mere story.

I came away from the play with my mind reeling. This wasn't the way stories were supposed to work out. Even if something in this guy propelled the Salesman into screwing-up, no author was supposed to say, in the same breath, that the system also had failed the Salesman.

This was my first intimation that the American Dream was—what? An implant, a hoax, an illusion. No mere Night in the Theater was supposed to make me nervous about the ground I stood on.

I realized in that moment that the theater was the only public place where truth could be spoken aloud. No wonder plays, evenings in the theater, entertainments, were censored. No wonder they were banned, no wonder governments were uncertain about this medium above all others. No wonder they wanted to suppress this stuff. No wonder they still want to.

This was the magic of story telling. This was the provocation, the sly galvanization, to political action. No other medium has this power. No wonder I was shocked and compelled by the witchcraft of that night.

And it was all caused, it was all started, by a sleight of hand. It was the first time I had realized that a sleight of hand could tell me something rather than hide something from me. The next time I saw this phenomenon was four years later when I saw a regional theater production of The Crucible. I wouldn't see it again until I moved to New York City and saw the Off Broadway smash hit production of A View from theBridge.

It is a great privilege to be able to acknowledge, before The Man, my generation's debt to Arthur Miller. And to thank him (I think I thank him, 'cause this stuff ain't easy) for thrilling us, and for showing us the way.

And for setting the standards so high that it will take us all a lifetime to try, in our own way, to repay him for the lesson.

NOTES

Quoted in Brenda Murphy, Miller: Death of a Salesman (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 66.

"Death of a Salesman, A New Drama by Arthur Miller, has premiere at Morosco," New York Times, 11 February 1949.

"Streetcar Bolsters Broadway's British Name," Christian Science Monitor, 27 March 1974, F6.

Murray Schumach, "Miller Still a 'Salesman' for a Changing Theatre," New YorkTimes,26 June 1975, 32.

Christian-Albrecht Gollub, "Interview with Arthur Miller," Michigan QuarterlyReview 16 (1977), 123.

Richard I. Evans, Psychology and Arthur Miller (New York: Dutton, 1969), 91.

Robert W. Corrigan, "Interview with Arthur Miller," Michigan Quarterly Review, 13; 4 (Fall 1974), 402.