The Beauty and the Freak

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact [email protected] for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

The central goal of what might be called the New Disability Studies is to transfigure disability within the cultural imagination. This new critical perspective conceptualizes disability as a representational system rather than a medical problem, a discursive construction rather than a personal misfortune or a bodily flaw, and a subject appropriate for wide-ranging cultural analysis within the humanities instead of an applied field within medicine, rehabilitation, or social work. From this perspective, the body that we think of as disabled becomes a cultural artifact produced by material, discursive, and aesthetic practices that interpret bodily variation. Similar to ethnic or gender studies, disability studies is part of a larger critical methodology sometimes termed "body criticism," which excavates the meanings of embodied differences and explores how the body has been understood over time.[1] Such an approach focuses its analysis, then, on how disability is imagined, specifically on the figures and narratives that comprise the cultural context in which we know ourselves and one another.

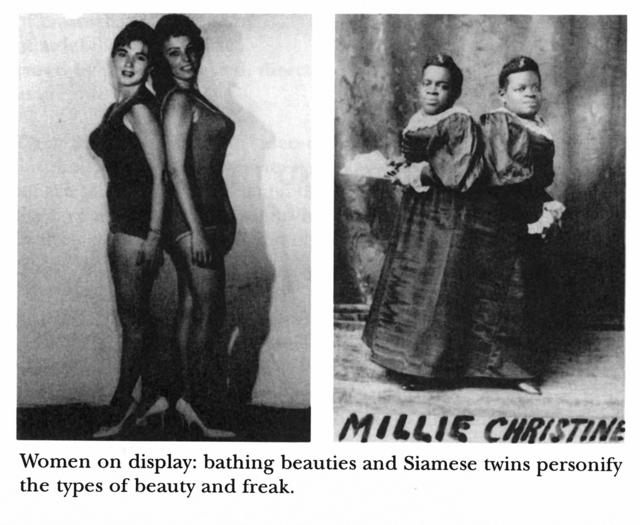

The figures and narratives of any representational system are often clearly apparent in the public rituals or ceremonies that produce them. Exaggerated scale, stylized gestures, and intensified signification make such public rituals highly readable.[2] By analyzing the conventions of display and the narratives of embodiment that the beauty pageant and the freak show employ, I will suggest here that the cultural work of these two public spectacles is to ritually mark the bodies on view, rendering them into icons that verify the social status quo. Although one traffics in the ideal and the other in the anomalous, both the beauty pageant and the freak show produce figures—the beauty and the freak—whose contrasting visual presence gives shape and definition to the figure of the normative citizen of a democratic order. The highly mediated versions of the feminine body and the disabled body these rituals fashion are elements of an aggregate of rhetorical figures arrayed in opposition to the fiction of the common man, a normative subject position available to the viewers of either the beauty pageant or the freak show.What I want to suggest, then, is that the dynamics of display and the narrative strategies I discuss here create not only the visually vivid beauties and freaks at the rituals' centers, but that they work at the same time to create an ideal—indeed, an ideological spectator.[3] So, rather than focusing on the actual exhibited bodies or on the responses of actual viewers—who as individuals may indeed resist the assumptions of the exhibitions—I am interested here in examining the beauty pageant and freak show as rhetorical cultural texts that employ narratives, props, staging, costuming, choreography, and technologies to fabricate the cultural figures of the beauty, the freak, and the spectator. In other words, I seek to explicate the dynamics and strategies these theatrical spaces engage to explore how representational systems such as gender, race, and disability operate hyperbolically to create an illusory position of authoritative normativity into which a viewer can enter for a price.

Let me begin by briefly outlining the historical roots of both social rituals. Both the freak show and the beauty pageant were institutionalized in the late nineteenth century as distinctly modern, commercial manifestations of traditional social ceremonies that dated from antiquity. The earliest beauty contests recorded are the fateful judgement of Paris that launched the Trojan War and the Biblical account of a contest that Xerxes held to choose Esther as his queen. Beauty contests descend from pagan Twelfth Night and May Day festivals, which both featured queens, although the criterion for selection was usually not beauty but status. Deriving from Roman spring festivals, these ceremonies persisted in such forms as medieval tournaments, early America's Merrymount settlement, Mardi Gras, the revivals of tournaments in the antebellum South, winter carnivals, and contemporary pageants such as the Pasadena Tournament of Roses Parade—replete with its annual Rose Queen.[4]Freak shows are a modern manifestation of the ancient practice of displaying and interpreting monsters, what we would today call people with congenital disabilities, as ominous and wondrous portents. Reading the bodies of monsters as an index of the divine or natural order can be traced from Homer's Polyphemous through Aristotle, Cicero, Augustine, and Montaigne, through medieval Fools and court dwarfs, early science's cabinets of curiosities, the commercial exhibitions of monsters at London's Bartholomew Fair, Barnum's museums and circuses, and the French scientist Geoffrey Saint Hilaire, who in 1832 coined the term "teratology" to name the science of monsters.[5] Both of these often celebratory, ever astonishing, traditional rituals of bodily exhibition culminate for us today in the familiar, slick spectacle of the televised beauty pageant and the remembered, tawdry sideshow we often furtively visited at the fairs, circuses, or boardwalks of our youth.

The Golden Ages of American freak shows and beauty pageants were more contiguous than overlapping. Freak shows burgeoned from about 1850 to 1920, while beauty pageants flourished from about 1920 to 1970. While both performances exist residually today, neither commands the cultural authority it did in an earlier era. The heyday of the freak show begins in 1841, when P. T. Barnum acquired the American Museum on New York's Broadway, which institutionalized the previously itinerant exhibitions of monsters—or freaks of nature—that had long gone on at taverns, halls, and fairs.[6] As the nation secularized in the eighteenth century, the interest in extraordinary bodies shifted from religious augury to curiosity, what Constance Rourke calls a "devouring passion for the morbidly strange," that sought fulfillment in the growing entertainment industry and in the ascending discourse of science.[7] Freak shows proliferated in a chaotic, mid-nineteenth-century America that was newly urbanized, geographically as well as socially mobile, increasingly literate, market-driven, and socially stratifying. General rootlessness, a taste for the novel, and changes in work patterns kindled a vibrant entertainment and leisure industry fueled by the ambitions of eager entrepreneurs. The enormously popular nineteenth-century urban dime museums, rural travelling circuses, and the later grand exhibition fairs of the early twentieth century circulated and publicized freaks.[8] Most prevalent at century's end, the freak show began to fade by 1940 as anomalous bodies moved from the discourse of the marvelous into the discourse of medicine, shifting them from prodigy to specimen, from stage to asylum.

Apparently recognizing the affinity between freaks and beauties, P. T. Barnum organized America's first real beauty contest in 1854. Always striving for a middle-class clientele, Barnum tried to mount a genteel beauty contest in the wake of his successful dog and baby contests, but no respectable women submitted entries so he converted it into a photographic beauty contest to avoid displaying actual female bodies to his proper audiences. Although his plan never materialized, a genre of photographic beauty contests emerged that prepared entrepreneurs to marry the beauty pageant with the beach resort industry that developed with the popularity of seaside bathing toward the century's end. Like freak shows, beauty pageants were commercial performances which flourished as leisure, entertainment, and amusement arose from mobility, urbanization, and wage labor. The lifting of restrictions on displays of female bodies, heralded in 1907 by the invention of the swimsuit, authorized the widely popular, cross-class beauty contests of today. By 1925, the female body was exposed, and beauty queens wore suits that resemble our contemporary ones. The Miss America Pageant, established in 1921, institutionalized and fully commercialized beauty contests. As freak shows began to wane, shrinking into the county fair sideshows and tawdry museums, modern, national beauty pageants began to wax and formalize.

The freak show and the beauty pageant thrived within a general culture of exhibition as America modernized and redefined itself.[9] What Mark Selzer terms emergent consumer culture's "excited love of seeing" drove Americans in huge numbers to orchestrated public displays such as Barnum's 1850 tour of singer Jenny Lind, the 1853 art and science exhibits in New York's Crystal Palace, and the 1876 Philadelphia Centennial Exhibition—spectacles that visually sanctified the American political, economic, or ideological status quo.[10]

Spectacles such as beauty pageants and freak shows entail structured seeing. Unlike participatory rites such as Carnival, these visual spectacles enact what Susan Stewart calls "the pornography of distance," by founding a triangle composed of the viewer, the object viewed, and the mediating forces that regulate the encounter.[11] The display's particularly intense capacity to signify facilitates a kind of cultural didacticism where an array of scripts, roles, and positions can be writ large. Although political, ideological, and economic forces ultimately determine the relationship between spectator and spectacle, the mediators appropriate the power of the ritual by choreographing the relationship and manipulating its conventions for their own ends, which were almost always commercial. For example, Barnum—America's master of spectacle—staged the 1863 extravaganza of General Tom Thumb's wedding to Lavinia Warren in New York's Grace Church. This spectacle of what one critic identifies as "the cute" enlisted sentimental ideology, disguised sexual voyeurism, bourgeois attraction to celebrities, public appetite for novelty, and entrepreneurial skills.[12] Barnum profited from this immensely popular and respectable freak show by framing the way the public—which of course extended far beyond those in the church—looked at this notorious ceremony. Similarly, the first Miss America Pageants in the early 1920s exploited the participatory conventions of Carnival and pagan festivals to stage a commercial spectacle that capitalized on the sexual voyeurism of the newly popular seaside bathing culture in an attempt to extend the Atlantic City tourist season beyond Labor Day.

The three constituent elements of the beauty pageant and freak show—viewer, viewed, and mediator—are not equally visible, of course. The viewed object is overwhelmingly conspicuous while the viewer and intermediaries remain obscured. Whether the spectacle is Atlantic City's Miss America in her swim suit and high heels, or the dime museum's Krao, the "Missing Link," or Chauncey Morley, the "Fat Boy," all eyes and all attention rest upon the displayed body so that the complex relationship of looking contracts, seeming to consist of only the exhibited body itself. This visual and spatial choreography between a disembodied spectator and an embodied spectacle enlists cultural norms and exploits embodied differences for commercial ends, creating a rhetorical opposition between supposedly extraordinary figures and putatively ordinary citizens. The beauty pageant and freak show do this by decontextualizing bodies from their lived environments and recontextualizing them within the stylized frame of the particular exhibition, rendering the viewed body a highly embellished representation of itself that reconstitutes its identity. Thus, someone's sister becomes the Queen on her float; black children with vitiligo become "Spotted Boys" in a sideshow; and a woman with a congenital disability becomes "The Armless Wonder" in a dime museum. But the conventions and narratives of presentation make them so. The crown, gown, sash, and float; or the grass hut, spears, and loincloth; or the platform, showman's pitch, and spotlight accomplish this transformation of life into spectacle.

The beauty pageant and freak show differ from many other cultural spectacles because the displayed object is a human body. While sporting events, operas, and political inaugurations, for instance, also involve viewing the body, in those performances the body's actions rather than the body itself carry the significance. Even though beauty pageants and freak shows almost always feature an ancillary performance to enhance the exhibited bodies, the spectacle is the body itself rather than what it does. Cultural resonances lodge in the very bodies of the beauty queen and the freak. So while the Miss America Pageant has included a mandatory talent competition since 1935 and has recently even added a question/answer component allowing the women to demonstrate opinions and intelligence, it is the Swimsuit and the Evening Gown Competitions that nevertheless are the pageant's essence, the vehicles securing its cultural work. In the Swimsuit Competition especially, the generic female body, rather than any particular woman, invites literally and symbolically the scrutiny of an evaluating male gaze, hyperbolically reenacting traditional gender relations as well as confirming masculinity and its privileges. In the freak show, the anomalous body functions similarly to the standard body of the beauty queen by working to establish the borders of the canonical body. Both exhibitions unify a disparate audience into the fantasy of an egalitarian community of citizens and assure them of their status as ordinary and normal.

The dynamic of these performances thus converts private bodies into public exhibitions whose cultural work is to constitute mutually the identities of viewer and viewed by enacting existing power relations. Both the beauty pageant and the freak show traffic in otherness by fetishizing the bodies of people from groups traditionally associated with the body's processes, maintenance, and limitations: women, the disabled, people of color.[13] The presentation exaggerates, stylizes, and saturates every detail of the exhibited body with social meaning. Public stage names, for instance, supplant private family names so that Charles Stratton becomes General Tom Thumb; Fedor Jeftichew becomes Jo-Jo, the Dog-Faced Boy; and Eli Bowen becomes The Legless Acrobat. On the runways and under the lights, Marys, Elizabeths, and Barbaras become Miss Washington, Little Miss Albany, or even The National Potato Chip Queen. Beauties and freaks become tableaux vivants orchestrated to make them hyperlegible texts from which the onlookers can pay to read their own desires, anxieties, and destinies. Although words are certainly part of the textual creation of beauties and freaks, I want to explicate the visual grammar of these exhibitions because that is what generates their primary ideological language. Costuming, props, and staging compose this fundamental visual rhetoric of beauty pageants and freak shows.

The beauty queen's costuming constitutes a sexualized discourse. Consider, for example, her traditional insignia: the satin sash—emblazoned with her public designation and extending across her body—accentuates breasts, waist, and hips as it claims her torso and rehearses the quantification of her body to 36-24-36. Compare this with masculine military insignia, for instance, which rest decorously on the sleeve, the shoulder, the hat. A striking illustration of this literal embodiment of language occurred in the 1964 Miss Antifreeze Contest, which explicitly transformed the women's bodies into an advertisement for the sponsor's product by spelling out the brand name of the antifreeze one letter at a time on each contestant's hip so that as they stood on stage, "Xerex" appeared across the bodies, making them a living billboard.[14] The beauty queen's conventional costume of the familiar swimsuit and high heels signifies potently as well. This contradictory combination of apparel that would never be worn together in everyday life appears on the pageant stage for its symbolic rather than its use value. The suit is not for swimming nor are the shoes for walking. Rather, such costuming affirms the constructed nature of beauty as a form of passive feminine fleshliness. Such costuming is augmented by the beauty's eroticized poses, which instruct viewers on the social position for which she is the icon: a corporeal other for male consumption.

Costuming and props inflect the freak's body, as well. "Armless" and "Legless Wonders," for example, always wear conventional clothing and are featured with quotidian objects such as tea cups, chairs, needlework, or family members. Such staging juxtaposes ordinary trappings with extraordinary bodies to heighten the differences between typical bodies and singular ones. Enhancement of differences is always the major strategy in presenting freaks. For instance, "Human Skeletons" and "Fat Men" often appeared together wearing tights to accentuate their forms. Giants, whose costumes frequently alluded to mythological characters, such as Wagnerian Giantesses, almost always were shown next to people of typical size and ordinary dress. In these juxtapositions, the freak was always individualized by highly marked costumes, such as elaborate military uniforms, while the ordinary person wore a standard, undistinguishing outfit. In another variation of these oppositional images, "Bearded Ladies" in standard feminine garb posed with their husbands to invite the subtle sexual titillation of gender trespasses. Freak shows thus presented people with what we would today call congenital disabilities in order to accentuate their role as what I call corporeal freaks.

The other major category of freaks can be thought of as cultural freaks, who in contrast were usually nondisabled, but were people of color exoticized by costuming and props.[15] "Wild Men," "Zulu Warriors," "Cannibals," and "Missing Links" always appear in generic jungle settings, brandishing spears, loincloths, and the uninhibited hair characteristic of the eroticized "Circassian Slave," a kind of exotic fusion of the beauty queen and the cultural freak.[16] Such props and costumes suggest alienness, transgressive appetites, or forbidden sexuality, and helped legitimate imperialism by depicting cultural others as uncivilized savages needing subjugation or benevolent paternalism.

Costuming establishes a distinction between the highly distinctive beauty and freak and the inconspicuous emcee, judge, managers, and audience. Beauties and freaks appear in ornate, visually provocative costumes that reveal the contours and details of the body, underlining its particularity. The elaborate accouterments and apparel worn by both freaks and beauties embellish difference by marking the body with its own singularity. Similarly, the garish feathers and spears of the exotic freaks highlight bodily specificity, assuring that the exhibited figure cannot assume the universal subject position of the democratic common citizen. Indeed, status and privilege remain unmarked, costumed in the universal gentleman's suit of the judge, the emcee, the showman—the normative male. It is these visually undistinguished figures who signify power now, while the extravagant costumes of the beauties and freaks parody the highly marked bodies of the distinguished aristocrat in a premodern era.[17]

Enhancing the costuming and props, staging explicates the relationships beauty pageants and freak shows try to establish between viewers and viewed. Both freaks and beauties occupy a viewing platform which literalizes their decontextualization, fashions their display, and enforces the objectifying distance essential to the spectacle's cultural work. The beauty pageant's runway typically extends into the audience so viewers and judges can gaze at the bodies from all angles; in addition, the runway's elevation and edges maintain an absolute border between the audience and the displayed figures. The use of floats in modern beauty parades accomplishes similar spatial cultural work by implanting the beauty in a mythical, literally artificial setting that emphasizes her role as icon and removes her from the world of agency and subjectivity. Like the pageant's runway, the freak platform isolates the exceptional, particularized freak from the undifferentiated community of onlookers whose normalcy the freak's presence validates with a body visibly marked by irrefutable difference.

Technologies of reproduction disseminate the choreographed images of both beauty and freak, expanding the arena of their cultural work and commercial potential. Analogous to the platform and runway are the technological choreographies of photography and television, which isolate and project these figures far beyond the spatial and temporal limits of the dime museum stage, circus sideshow stand, boardwalk parade, or gala pageant ball. But where the modern beauty of the later twentieth century is multiple and infinitely iterable as an icon of mass culture, the nineteenth- and early twentieth-century freak who gestures to an earlier tradition of marvelous monsters emblematizes the singular, the anomalously unique.[18] Both on stage and in reproductions, the grammar of freaks appears in the singular, whereas beauties appear in the plural. Such technologies double the effect of representation by literally reframing the freak and beauty already staged by the performance. At the same time, these forms of mechanical reproduction multiply reiterate the messages in the presentations. In the antebellum era, the popular, inexpensive photographic portraits called cartes d'visites and cabinet photographs transferred freak images from the stage to the parlor, nestling them comfortably by the thousands in leather-bound albums alongside familiar family members.[19] Similarly, television shifted the Miss America Pageants in 1954 from local to national communal spectacle, making them universally available by transcending all barriers to seeing the actual shows. In response to technologies' demands, the pageants became even more deliberately structured and began to be staged for television rather than for live audiences. So the camera eroded even the context of live performance from around the exhibited bodies of beauties and freaks, eliminating audience participation, spontaneity, and direct apprehension even as it increasingly circulated the figures of beauties and freaks.

Another aspect of staging is the physical presence of mediators who act as the audience's representatives by directing the action of the performance and providing the verbal narrative which situates the freak or beauty in relation to the viewers. Whether it is the freak show's pitchman, the circus ringmaster, the showman hawking sensationalized pamphlets, the manager arranging the show, the pageant's tuxedoed emcee, or the judge, the mediator is always of the audience rather than of those exhibited. No dialogue transpires between spectator and spectacle; instead, the mediator, who possesses voice, agency, and power, conducts the drama both for the viewers and before the viewers by explicating the intensely visible, mostly silenced spectacle. In beauty contests, judges are, of course, the most authoritative mediators.[20] The relation between judge and beauty institutionalizes the cultural right of all men to evaluate the bodies of all women and recapitulates the competition among women for male favor that unequal power begets. In freak shows, the showmen's role was often augmented by life story pamphlets. These ephemera combined the discourses of both wonder and science by providing elaborate stories that cast freaks as marvels while at the same time enhancing the freaks' credibility by including reports of doctors' examinations or testimonies of scientists about the freaks' remarkable singularity.

Together, these highly theatrical conventions constitute a field of hyper-representation that at once domesticates and exoticizes the freak's and the beauty's exhibited bodies. Even though these practices colonize private bodies by fashioning them into objects of public scrutiny, exhibition does not render them wholly other. Indeed, the freak's and the beauty's cultural function depends upon their being seen as simultaneously self and other, as at once comfortable and strange, as both alluring and repelling.[21] Capitalizing on and amplifying the viewer's potential ambivalence, beauty pageants and freak shows encourage simultaneous identification and differentiation. For example, the "Armless" or "Legless Wonders" who performed mundane tasks like sewing, writing, riding a bicycle, or drinking tea were at once routine and amazing, both assuringly domestic and threateningly alien. "Fat Ladies" and "Human Skeletons" alike dressed like Victorian ladies. Beauty queens at once represent the girl-next-door and the apotheosis of femininity; they are simultaneously highly eroticized and emblems of virginal purity, confusingly familiar and yet teasingly unattainable.

Audiences nevertheless adore beauties and freaks even as they appropriate them, or perhaps because they appropriate them. Spectators pay willingly, watch raptly, display their images in their own living rooms, grant them near celebrity status, encourage their daughters to compete. Moreover, freaks were the most highly paid performers in early dime museums, and Miss Americas of the 1980s could reap $35,000 in scholarships and $125,000 in appearance fees. Distanced yet familiar, freaks and beauties are like pets, existing for the enjoyment, satisfaction, or instruction of audiences who have paid for that privilege.[22] The shows and pageants produce figures that are novel scenery for the arousal or gratification of their onlookers. Through hyperbolized sexual role performances, the figure of the beauty offers to make her viewers into men. By parading exaggerated bodily lack or excess, corporeal freaks invite their viewers to imagine themselves whole. By flaunting savagery, cultural freaks extend the illusion of civilization to their audiences.

We can convey the artifactuality of freaks and beauties by naming these processes of iconography enfreakment and beautification. As an older cultural form, enfreakment uses the grammar of singularity, highlighting the uniqueness of the exhibited body in its difference from the norm.[23] Beautification, by contrast, operates in the plural, suggesting the infinite reproducibility of otherness as a commodity within mass culture. Freak discourse attempts to evoke wonder, what Stephen Greenblatt has called "an exalted attention," which is premodernity's characteristic response to the extraordinary.[24] Pageant discourse, on the other hand, traffics in what Anne Balsamo calls "assembly-line beauty," which is characteristic of late capitalism's effort to standardize, infinitely reproduce, and mass market both subjects and objects.[25]

Enfreakment and beautification illustrate the paradox of social objectification. These processes create a spectacle that renders the lived body's humanity and subjectivity invisible at the same time that it makes the exhibited body into a wholly visible cultural text. The shows and pageants accentuate freaks' and beauties' bodily particularity, while their watchers function as an undifferentiated aggregate. The spectacle positions the viewers in the realm of the universal while it sentences the viewed to the world of the particular. Because spectators only look, do not touch, or interact, or reveal themselves to the spectacles, these are one-way encounters controlled to guarantee the privilege of anonymity for the viewer and to highlight the visibility of the viewed. These are rites of power distribution which license spectators as readers and certify the readability of spectacles. Such a relationship grants viewers a fantasy of disembodiment and forces upon the freak and beauty an illusion of intense embodiment.[26] The figures of the beauty and the freak enter into culture not as agents or subjects but as ultravisible icons, contrived figures whose cultural work is to ritually verify the prevailing sociopolitical arrangements arising from representational systems such as gender, race, and physical ability.

Beauty pageants and freak shows thus ritually enact a kind of symbolic transference of embodiment within a cultural tradition which deeply, anxiously distrusts the body and its vulnerabilities. The dynamics of enfreakment and beautification aim to construct and affirm a normative, generic subject of democracy who possesses the entitlements of agency, volition, voice, mobility, rationality, sameness, and cultural literacy, but who is released from the restrictions and limitations of embodiment. Rendered by the conventions and narratives, the figure of such a normative democratic self haunts the shows and pageants, regardless of whether the actual audience members identify with such an image. Entitled by the dime or ticket and the accompanying leisure his hard work has yielded, as well as informed by the alluring narratives he has read, the figure constructed by the exhibits can freely assume the egalitarian, anonymous position of the "common man." Coming and going at will, this universal subject looks without being seen, judges without being judged, enjoys without being enjoyed, knows without being known. The object of unassimilable bodily difference before him eradicates any felt distinctions from the other democrats who gaze together with him in a communal act of ritualized viewing that unites them as citizens in a social contract validated by the presence of that embodied other. The beauty's ultra-feminine fleshliness, the cultural freak's alien physiognomy, and the corporeal freak's atypical form confer upon them an embodied particularity against which the citizen's body seems to fade into a generality. The intense focus on the body on view offers the citizen the promise of disembodied abstraction, rendering him a kind of Emersonian transparent eyeball. Ritually banishing embodiment in this way soothes suspicions that the body's demands and restrictions threaten unfettered self-determination, freedom, autonomy, and equality—democratic ideals upon which American individualism depends.

NOTES

1. Rosemarie Garland Thomson, "Body Criticism," Disability Studies Quarterly 17, 4 (Fall 1997) 284-6; examples of body criticism include Barbara Maria Stafford, Body Criticism: Imagining the Unseen in Enlightenment Art and Medicine (Cambridge, MA: MIT University Press, 1991); Susan Bordo, Unbearable Weight: Feminism, Western Culture, and the Body (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1993).

2. For example, see Mary Ryan, "The American Parade: Representations of the Nineteenth-Century Social Order," in Lynn Hunt, ed., The New Cultural History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1989), 131-53.

3. The production of this ideal viewer is similar to the process theorized by reader-response critics through which texts train readers to apprehend the texts they read. Particular readers—or viewers, in the case of beauty pageants and freak shows—might either participate in or resist this shaping. The point, however, is to uncover the practices and strategies that the text employs to produce such a reader. See, for example, Wayne C. Booth, The Rhetoric of Fiction, Second Edition (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1983); Wolfgang Iser, The Implied Reader: Patterns of Communication in Prose Fiction from Bunyan to Beckett (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1974); and Judith Fetterley, The Resisting Reader: A Feminist Approach to American Fiction (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1978).

4. For discussions of beauty contests and their history, see Lois W. Banner, American Beauty (New York: Alfred A. Knopf, 1983); Frank Deford, There She Is: The Life and Times of Miss America, revised edition (New York: Penguin, 1978); William Goldman, Hype and Glory (New York: Villiard Books, 1990); Henry Pang, "Miss America: An American Ideal, 1921-1969," Journal of Popular Culture 2 (Spring 1969), 687-96; R. A. Riverol, Live from Atlantic City: The History of the Miss America Pageant Before, After and in Spite of Television (Bowling Green: Bowling Green University Popular Press, 1992); and Sharon Romm, The Changing Face of Beauty (St. Louis: Mosby-Year Book, 1992).

5. Mark V. Barrow, "A Brief History of Teratology," in Problems of Birth Defects, ed. T. V. N. Persaud (Baltimore: University Park Press, 1977), 18-28. For a history of teratology, see J. Warkany, "Congenital Malformations in the Past," in Problems of Birth Defects, 5-17.

6. For discussions of premodern freak shows and monsters, see Richard D. Altick, The Shows of London (Cambridge: Belknap Press, 1978); Arnold I. Davidson, "The Horror of Monsters," in The Boundaries of Humanity: Humans, Animals, Machines, ed. James J. Sheehan and Morton Sosna (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1991); Leslie Fiedler, Freaks: Myths and Images of the Secret Self (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1978); John Block Friedman, The Monstrous Races in Medieval Art and Thought (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1981); Katharine Park and Lorraine J. Daston, "Unnatural Conceptions: The Study of Monsters in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century France and England, Past and Present: A Journal of Historical Studies 92 (August 1981), 20-54; and Dudley Wilson, Signs and Portents: Monstrous Births from the Middle Ages to the Enlightenment (London: Routledge, 1993). For discussions of the role curiosity cabinets, early forms of freak shows, played in museum culture, see Edward Miller, That Noble Cabinet: A History of the British Museum (Athens: Ohio University Press, 1974); and Arthur MacGregor and Oliver Impey, eds., The Origins of Museums: The Cabinet of Curiosities in Sixteenth- and Seventeenth-Century Europe (New York: Oxford University Press, 1984). For discussions of modern freak shows, see Robert Bogdan, Freak Show: Presenting Human Oddities for Amusement and Profit (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1988); Frederick Drimmer, Very Special People: The Struggles, Loves, and Triumphs of Human Oddities (Amjon Press, 1983); Howard Martin, Victorian Grotesque (London: Jupiter Books, 1977); and Rosemarie Garland Thomson, ed., Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York: New York University Press, 1996). For histories of Barnum see Neil Harris, Humbug: The Art of P. T. Barnum (Boston: Little Brown, 1973); A. R. Saxon, P.T. Barnum: The Legend and the Man (New York: Columbia University Press, 1989).

7. Constance Rourke, Trumpets of Jubilee (New York: Harcourt, Brace, 1927), 389.

8. For a thorough discussion of the fairs to which freak shows were attached, see World of Fairs: The Century-of-Progress Exhibitions (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1993). For a brief overview of circuses, see Marcello Truzzi, "Circus and Sideshows," in American Popular Entertainment, ed. Myron Matlaw (Westport, CN: Greenwood Press, 1979). For discussions of dime museums and the rise of popular entertainment in general, see Andrea Stulman Dennett, Weird and Wonderful: The Dime Museum in America (New York: New York University Press, 1997); and David Nasaw, Going Out: The Rise and Fall of Public Amusements (New York: Basic Books, 1993). For analyses of the medicalization of freaks in the twentieth century, see Bogdan, Freak Show; and Park and Daston, "Unnatural Conceptions."

9. The notion that performance and spectacle characterize what Jameson calls the postmodern "cultural dominant," which is informed by consumer culture and its attendant commodification, is explored widely in critical thought, especially the new cultural studies. Surely those theories apply to the period and genre I am speculating about here as they coincided with the emergence of western consumer culture that thrived in America, unchecked by previous traditions and nurtured by the ideology of democracy . While I generally am influenced by and draw upon those critical insights and perspectives, I wish here to mount more of a close textual reading, as it were, of the freak show and beauty contest as they function in American ideology than to show how these institutions exemplify incipient postmodernity. See Fredric Jameson,"Postmodernism, or the Cultural Logic of Postmodernism," New Left Review 146 (July-August 1984), 53-92; Guy Debord, The Society of the Spectacle (Detroit: Black and Red Press, 1977); Hal Foster, Recodings: Art, Spectacle, Cultural Politics (Port Townsend, WA: Bay Press, 1985); Janelle G. Reinelt and Joseph R. Roach, Critical Theory and Performance (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1992); Erving Goffman, The Presentation of Self in Everyday Life (New York: Penguin, 1971).

10. Mark Seltzer, Bodies and Machines (New York: Routledge, 1992), 97.

11. Susan Stewart, On Longing: Narratives of the Miniature, the Gigantic, the Souvenir, the Collection (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1984), 110. In The Society of the Spectacle, Guy Debord asserts rightly that "the spectacle is not a collection of images, but a social relation among people." However, the limitation of Debord's analysis is his relentless demonization of the spectacle as the totalizing instrument of false consciousness in a hopelessly fallen capitalist modern society. For other analyses of the spectacle in modern society see John J. MacAloon, ed., Rite, Drama, Festival, Spectacle (Philadelphia: Institute for the Study of Human Issues, 1984); Rachel Bowlby, Just Looking: Consumer Culture in Dreiser, Gissing, and Zola (New York: Methuen, 1985); John Berger, Ways of Seeing (London: The British Broadcasting Corporation, 1972); and Kristin Boudreau, "'A Barnum Monstrosity:' Alice James and the Spectacle of Sympathy," American Literature 65,1 (March 1993), 53-67.

12. Lori Merish, "Cuteness and Commodity Aesthetics: Tom Thumb and Shirley Temple," in Rosemarie Garland Thomson, ed., Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York: New York University Press, 1996), 185-206.

13. In a nuanced analysis of the grotesque body, Peter Stallybrass and Allon White in The Politics and Poetics of Transgression (Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1986) observe this paradox of simultaneous marginality and centrality in the representation of the corporeal other; they note that "What is socially peripheral may be symbolically central" (23).

14. New York World Sun and Telegram archive photograph, Library of Congress.

15. A further explication of corporeal and cultural freaks is found in Bogdan, Freak Show; and Rosemarie Garland Thomson, Extraordinary Bodies: Figuring Physical Disability in American Culture and Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), Chapter Three.

16. See Linda Frost, "The Circassian Beauty and the Circassian Slave: Gender, Imperialism, and American Popular Entertainment," in Rosemarie Garland Thomson, ed., Freakery: Cultural Spectacles of the Extraordinary Body (New York: New York University Press, 1996), 248-263.

17. For a discussion of premodern costuming of power, see Harold M. Solomon, "Stigma and Western Culture: A Historical Approach," in The Dilemma of Difference: A Multidisciplinary View of Stigma, ed., Stephen Ainlay, et al. (New York: Plenum Press, 1986), 59-76; see Thorstein Veblen, The Theory of the Leisure Class, 1899 (Boston: Houghton Mifflin Co., 1973); and Fred Davis, Fashion, Culture, and Identity (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1992) for discussions of the signification of dress after the eighteenth century.

18. For discussions of the iterable image in mass culture, see Walter Benjamin, "Art in the Age of Mechanical Reproduction," in Illuminations, trans. Harry Zohn (New York: Schocken Books, 1969) and Siegfried Kraucauer, The Mass Ornament: Weimar Essays, trans. and ed., Thomas Y. Levin (Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1995).

19. For a complete and insightful discussion of freak photography, see Michael Mitchell, Monsters of the Gilded Age: The Photographs of Charles Eisenmann (Toronto: Gage Publishing, 1979). The famous American photographer Matthew Brady, whose portrait of Lincoln was used during his presidential campaign and who photographically documented the Civil War, also made many freak portraits at his New York studio near Barnum's American Museum.

20. Michael B. Prince, "The Eighteenth-Century Beauty Contest," Modern Language Quarterly 55,3 (September 1994), 251-79, argues that the ideal beauty that such contests seem to celebrate is not rewarding to the bearer of the beauty but rather validates the good taste of the judges. My analysis of the beauty contest owes much to Prince's insightful analysis of how aesthetic theory laid the groundwork for the modern beauty contest.

21. For a discussion of this ambivalence in the process of creating otherness, see Leonard Cassuto, The Inhuman Race: The Racial Grotesque in American Literature (New York: Columbia University Press, 1997), especially Chapter One.

22. Characterizing the relation between pets and owners as one of dominance and affection, rather than dominance and cruelty, Yi-Fu Tuan, Dominance and Affection: The Making of Pets (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1984), says "A pet is a diminished being. . . . It serves not so much the essential needs as the vanity and pleasure of its possessor" (139).

23. I take the term "enfreakment" from David Hevey, The Creatures Time Forgot: Photography and Disability Imagery (London: Routledge, 1992), 53.

24. Stephen Greenblatt, "Resonance and Wonder," in Ivan Karp and Steven D. Lavine, eds., Exhibiting Cultures: The Poetics and Politics of Museum Display (Washington D.C.: Smithsonian Press, 1991), 42.

25. Anne Balsamo, "On the Cutting Edge: Cosmetic Surgery and the Technological Production of the Gendered Body," Camera Obscura: A Journal of Feminism and Film Theory 28 (January 1992), 209.

26. In his discussion of the construction of "typical Americans" in realist and naturalist texts, Mark Selzer in Bodies and Machines argues that consumer culture—which was, of course, developing during the period under consideration here—is characterized by "the simultaneous solicitation and disavowal of the natural body" so that some bodies, such as women and blacks, are seen as carrying more embodiment, while others are perceived as being relatively free of the body (50, 61). This is precisely the ideology I am suggesting that the freak show and beauty contest manifest.