Maro Drom: Music and Mnemonic Imagination in the Commemoration of German Sinti Victims during WWII

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Based on my ongoing ethnographic fieldwork, this article interrogates the role of cultural performances in the process of memory making between minority and majority groups in Germany. The article focuses especially on musical commemorations of the Sinti minority. It follows the musician Markus Reinhardt and Maro Drom, a minority-led grassroots organization in Cologne, and their efforts to organize three consecutive music festivals in 2018. I argue that the festival serves as transferential space in which family memories, cultural identities and social positionalities are mediated and negotiated. Drawing on memory studies-derived concepts that are firmly based on phenomenological understandings of socially shared memories, the article also pays close attention to aspects of social and spatial orderings as they pertain to memory. Key to this is an exploration of the role of imagination in processes of memory mediation and an examination of three levels of mnemonic imagination (selection, composition, and connection) as they play a pivotal part in not only communicating memories but also identities. The article investigates how the victims' and the survivors' experiences are represented and shared through music and how memories are re-enacted, re-owned and re-interpreted by German Sinti of the second and third generations.

Introduction: Maro Drom—Our Way

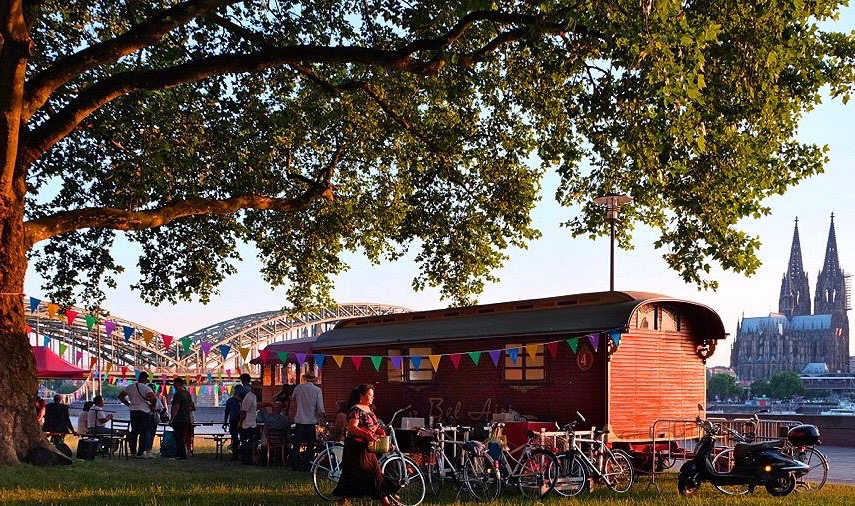

At the beginning of June 2018, the Cologne “Zigeunerwagenfestival” (Gypsy wagon festival) invited guests and passers-by who walked along the Rhine promenade in Deutz[1] to sit in the cool shade under old trees, to listen to a variety of live music, to enjoy food and drink, and to gain insights into the history and culture of German Sinti. The centerpiece of this four-day festival was a large, wooden-clad circus wagon. It stood in a semicircle with a couple of tents in which hot and cold drinks, cakes, and freshly cooked hot meals were served. Festooned with colorful garlands, with views of the Rhine and the iconic skyline of Cologne in the background, the festival attracted hundreds of people who talked of a Pariser Flair am Rheinufer (a Parisian flair on the banks of the Rhine). Over the course of four days, the festival provided a varied program of different musical acts, film screenings, public discussions, and readings, as well as a commemoration ceremony for the predominantly Sinti victims who had been deported to various concentration camps in May 1940.[2] The festival was organized by the “Zigeunerfestkommitee” (Gypsy festival committee)[3] and Maro Drom, a grassroots association newly founded by members of the Sinti community in Cologne and their affiliates. Two other installations in Worringen and Ehrenfeld followed in the same year.[4] All three festivals featured a similar program, including Sinti-led interactive workshops and presentations, music, discussions, and film screenings.

Figure 1: The wagon at the festival in Deutz, June 2018. Photo taken by and used with permission fromJan Krauthäuser.

Figure 1: The wagon at the festival in Deutz, June 2018. Photo taken by and used with permission fromJan Krauthäuser.Markus Reinhardt, born in 1958, is a prolific violinist and figurehead of the Maro Drom association. I first met him in 2016, and I have continued to work closely with him in the context of my fieldwork with European Sinti and Roma.[5] He introduced me to the other members of Maro Drom, his family, and the musicians who participated in the festival. I have since then worked intensively with Markus Reinhardt, conducted interviews with musicians, and held individual and group discussions with members of the Reinhardt family. I participated regularly in the festivals and concerts organized by Markus and Maro Drom. My fieldwork between 2016 and 2020, complemented by my continued exchange with the people of Maro Drom and their affiliates, form the empirical basis for this article.

This article explores the junctures between musical performances and social memory making through the prism of the three festivals held in 2018 in Cologne. In so doing, it draws on memory studies-derived concepts that are firmly based on phenomenological understandings of socially shared memories,[6] with a keen eye on aspects of social and spatial orderings as they pertain to memory and music. Key to this is a close examination of the role of imagination in processes of memory mediation.[7] On the basis of three ethnographic vignettes describing distinct moments of the festival, this article looks further into the role of cultural performances in the process of memory making between minority and majority groups in Germany. “Sounding Memories”[8] is a conceptual lens that focuses on the role of music in public memory performances such as the festival. It further pays close attention to the political and social valence of these memory making processes which is key to my analysis of the festival and its significance in Germany’s memory landscape today.

Historical Continuities and the Struggle for Memory

The discrimination and violence against Sinti and Roma in Germany as well as in other parts of Europe had a long history even before the Nazi regime;[9] however, the horror of the Nazi regime marked a moment of unprecedented magnitude and extremism in the history of antigypsyism. People who had been categorized as “Zigeuner” were stripped of their rights and homes, pushed into forced labor, or abused as human subjects in pseudo-scientific experiments, deported, and killed.[10]

Historians Karola Fings and Frank Sparing have compiled a comprehensive study of the Nazi persecution of “Sinti and Roma” in Cologne. In 1935, the city’s administration had established a so-called “Gypsy camp” at the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz in Bickendorf,[11] where between 1935 and 1940 at least 50 families had been forced to settle. The camp had only one entrance which was constantly guarded by an SS guard who conducted regular inspections and at times locked the gate to the camp overnight, effectively imprisoning them. They were discouraged from practicing their occupations and in many cases were forced into labor. Musicians, in particular, who since 1933 were required to be members of the Reichsmusikkammer (Reich Chamber of Music) which excluded non-Aryan musicians, were prohibited to work in their profession.[12]

They were subjected to examinations and registration by the “Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle” (research center for racial hygiene), led by Robert Ritter.[13] Members of the research center included his assistant Eva Justin and the anthropologist Adolf Würth. The role of Justin in the persecution of Roma and Sinti remains central in the memories of Sinti. She had learned their language and established rapport with many Sinti families, which ultimately led to their deportation.[14] On May 16,1940, the police conducted raids in several German cities. The camp at the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz was terminated and its inhabitants brought to the train station in Deutz, from whence they were deported to the concentration camps.[15]

Although it is frequently stated that the Sinti and Roma are an understudied group of victims of Nazism,[16] the corpus of historiographic literature that deals with the annihilation of Roma and Sinti in the concentration camps has steadily grown over the years.[17] Among these are studies with a regional or micro-historical approach,[18] as well as broader studies that inquire into the persecution of Roma and Sinti during WWII in general.[19] A growing number of (auto)biographies and academic literature by Sinti and Roma has greatly expanded the historiography of the so-called “forgotten holocaust.”[20] As Slavomir Kapralski states, the “process of gradually including the Roma” in memory narratives and histories of the Holocaust began only in the 1960s.[21] In Germany, the year 1982 marks a milestone in this respect, when chancellor Helmut Schmidt formally acknowledged the atrocities committed against Roma and Sinti during WWII as genocide.[22]

In the immediate postwar years, the climate for survivors was not only marked by the end of the war and the liberation from Nazi oppression, but was also in many cases still characterized by the continuation of racial stereotypification and discrimination. The presence of Nazi perpetrators in administrative positions after the war[23] and the continuation of racial profiling and discrimination by the police and other state jurisdictions, combined with a nation-wide “coalition of silence,”[24] forced Sinti and Roma to organize themselves in civil rights movements.[25] To this day, they form the backbone of the Sinti and Roma minority’s political representation and the public remembrance of the genocide.

After the war, the survivors returning to Cologne found that their barracks had been burned and their wagons dismantled or sold. Starting to rebuild their community and settling in barracks and ruins throughout the city, they were once again forced to move to designated places like the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz. This indicates that the majority population did not treat the returned Sinti as people in need of protection, but as a suspect group that needed to be controlled for the sake of public safety.[26] The forced evacuation of the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz began in 1958, and fifty-one Sinti families had to settle in trailers in Roggendorf at the very outskirts of Cologne.[27] In a public discussion, Markus Reinhardt drew explicit parallels between the Nazi regime and Cologne’s postwar administration by saying: “They forced my family to live in Roggendorf, in old wagons, the same that they had used to deport them to Auschwitz. The people who decided this were the same Nazis that had deported them. Think about that.”[28]

It was only in the 1980s that the inclusion of Sinti and Roma in the memorialization processes slowly began. The civil rights movement that later formed the basis for the Central Council of German Sinti and Roma—whose main objective was the public and governmental acknowledgement of the genocide and the legal support for Sinti and Roma in their fight for reparations—was mainly responsible for the inclusion of Sinti and Roma in public narratives of WWII. While the formal acknowledgment of the genocide was achieved, it took another thirty years until the inauguration of the “Memorial to the Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism”.[29]

Still, public remembrance of these victims largely remains a task for a few cultural activists, academics, and politicians. Remembrance ceremonies and other forms of performances of public memory that are initiated and held by minority members themselves are still an exception. It is in this historical and political context that the festival and the commemorations organized by Maro Drom gain their significance as a grassroots movement whose attitude towards sharing family memories is new to both the general public and the Sinti community.

Vignette 1: A Waltz to Remember

A few meters behind the wagon, Markus Reinhardt, accompanied by his fellow musicians Rudi Rumstajn (guitar), Elemèr Balogh (cimbalom), and Janko Mettbach (guitar), held the commemoration ceremony for the Sinti and Roma victims who been deported by the Nazis in May 1940. The ceremony was held on May 31, 2018, as the first activity of the Zigeunerwagenfestival. It was announced that the expected guest Philomena Franz, an author and a Sintezza[30] who survived Auschwitz, would not participate due to her health. Instead, Jan Krauthäuser, co-organizer of the festival, and Werner Jung, director of the NS Documentation Center in Cologne, gave short speeches in which they highlighted the importance of remembrance in times of a resurgent far right in Germany and Europe. Both recognized the efforts of the Maro Drom association in organizing the festival and the contributions of the Sinti to a collective commemoration of the victims from minority groups. Meanwhile, a crowd consisting of all sorts of music enthusiasts, flaneurs, cultural activists, as well as parents and children had formed a semicircle around them. Then Markus Reinhardt stepped up to the microphone and shared his family’s history and the idea behind the Zigeunerwagenfestival:

We had been living in Bickendorf on the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz. And they had all been living in wagons. Then, during the war and the Nazi regime they were all deported and brought to Auschwitz and other concentration camps. My grandfather said to the others: “Whoever makes it out, we will meet back in Cologne.” Of course, Cologne. And they did. And when they came back, their caravans were gone. For a very long time, years in fact, I have had the idea to get one wagon back, so that we would get something back. Something that the Nazis had taken from us. And we finally succeeded. We got a wagon back, but we do not want to keep it just for ourselves, we want to bring it back into society and do something with it. We are planning different projects with kids, concerts, and readings, the same as we are doing now during these four days. Because this too is part of our culture, to contribute something to society. The Gadje mostly hear the bad things, that Gypsies steal, they are filthy, and they exploit the system. This is not true. But they don’t hear anything else, because we don’t go out into public. But we have now arrived at the point where we feel we have to go out, we have to go public to inform the Gadje, the non-Gypsies. And when they learn from us, we will be able to overcome these prejudices.[31]

The wagon presented at the festival is on loan from a collector and is used as a stand-in for the actual wagon that the association seeks to buy for their future projects. As Markus further explained, the association has planned a festival tour along the routes that the survivors took from Auschwitz back to Cologne, for which they still need to raise money. The musicians then proceeded to play two pieces—one was a csárdás,[32] and the other a waltz. Markus introduced the csárdás as a piece that is often played at parties and family feasts. “It has three parts: the first is slow and sad. Everybody cries. The second is more upbeat and a little faster. And then comes the last part. It is fast and everybody dances.”[33] The quartet started the piece in a slow tempo. While the guitars played the chords of the opening cadences with dramatical tremolo picking, Markus played his violin with an expression of gravitas using a repertoire of different techniques and bursts of melody. Then, the band segued into a second part with a pronounced beat and a fixed melody. Encouraged by the band’s change in posture and Markus’s rhythmic whistles, the audience joined in clapping. The band steadily increased the tempo, becoming ever more rapid before ending in a final cadence after which the audience burst into cheers. After the applause had died down, Markus took the microphone again and introduced the second piece that they were going to play. He told the audience the circumstances under which he had come to know the waltz and why he was going to play it. Markus first told the story of how he met the composer, a Rom who was a Holocaust survivor, on a journey to Hungary. He had told Markus that he had written the waltz while being imprisoned in a concentration camp, as a sign of hope. Markus had learned to play the waltz, which since then has become a staple in his musical repertoire. He continued telling the audience that members of his family, too, had been musicians in the concentration camps and that they had been required to play for the Nazis. They had been used to calm the newly arriving deportees and to lure them into a false sense of security. Markus ended his story by telling the audience that he had to promise the Hungarian composer to play this waltz whenever possible to honor the memory of the victims who died in the concentration camps.

Figure 2: Musical commemoration during the festival in Deutz 2018. From left to right: Rudi Rumstajn, Elemèr Balogh, Markus Reinhardt, and Janko Mettbach. Picture taken by the author.

While Markus and the other musicians were playing, two of Markus’s cousins went to the train station memorial further in the back and privately laid down flowers. Markus ended the ceremony with the sentence: “Those who join us during these four days will know more about Gypsies than most people.” Indeed, there have been plenty of instances during the festivals in which people came up to Markus and members of his family to ask them about their family’s history. Non-Sinti had particular interest in the wagon itself, asking questions such as whether the family had really lived in there, where they were living now, and how long they had been in Cologne.

The program of the festival featured musical acts such as the Maurice Peter Trio, who played jazz standards including songs by Django Reinhardt; Mikks Balkan Band, which—as the flyer to the festival stated—played a mixture of “Roma Folk and Balkan Funk”; and the Drago Riter family, who played a “world music” set with songs of the Gypsy Kings, Kaoma, and others. The Markus Reinhardt quartet played a set that focused on older German schlager, chansons, and operettas. Daily film screenings and public discussions between Sinti, Roma, and Gadje inside the wagon alternated with the concerts that were held outside. This general course of events—a commemoration ceremony where Markus explained the idea behind the wagon, the songs, and their contexts, followed by a festival with a diverse musical program featuring Sinti, Roma, and mixed musical acts, as well as film screenings and discussions—was retained over the course of the following festivals in 2018 and 2019.

Public Memory and Mnemonic Imagination

In my opinion, this moment of the festival’s inauguration reveals much about Cologne’s past that is virtually unknown to most people living in the city. When I asked Markus if he thought that the festivals had been a success, he summed up his impressions by telling me:

I think yes, there have been people who did not know about us. They did not know that we have been here for more than 600 years. They did not know that we were also deported and sent to the gas chambers. And we talked with many people. So yes, it was good.[34]

Furthermore, the vignette provides ethnographic details to a nexus of problems, which on their own already pose several theoretical challenges to the study of socially shared memory. In connection with the festival, these problems appear in a new context. The nexus of problems I am talking about revolves around the relationship between memory and imagination, specifically this relationship in the context of social mediation between group constellations. Here this concerns the Sinti and the Gadje, separated through their historic positionalities and narratives as well as the unequal power relationships. In the following, I will interrogate the theoretical approaches provided by studies of socially shared memories in hope of gaining a deeper understanding of the significance of such events as the Zigeunerwagenfestival with respect to the memory of WWII, imagination, and processes of social mediation across ethnic boundaries.

At the beginning of this endeavor, I am faced with a fundamental problem that results from the seeming incongruities between imagination and memory. While the “defining feature of remembering is taken as a sense of fidelity to the past,”[35] imagination is “directed towards the fantastic, the fictional, the unreal, the possible, the utopian.”[36] Imagination therefore appears suspect in the context of remembering, as it seemingly undermines memory’s fidelity in its connection to the past.

A second difference between memory and imagination that seems to further impede their coalescence is imagination’s directionality toward the present and future, while memory is directed towards the past. In their seminal publication Mnemonic Imagination: Remembering as Creative Practice, Emily Keightley and Michael Pickering contend that

memory and imagination are closely akin, though significantly distinct, and can only be considered as suspect or not in relation to the context in which their relationship becomes manifest. On the one hand this means that memory is a vital resource for imagining, and imagining is a vital process in making coherent sense of the past and connecting it to the present and the future. The remembering subject is faced with far more vacant spaces than spaces filled with available memories, yet it is out of what remains or can be recollected at will that we construct the story of ourselves and our lives. Such narrative is not built purely and simply out of memory. Life stories are constructed just as much out of how we imagine our memories as fitting together in retrospect. On the other hand of course, distortion, exaggeration, falsification, even outright invention may exist and these may derive from the imagination as well as from various ideological forms and frames. What we imagine may not necessarily be rooted in any verifiable memory, but the possibility of this does not in itself deny the positive role which imagination plays in narrative development of a life-story or the reconstruction of past experiences. Our memories are not imaginary, but they are acted upon imaginatively. [37]

It is precisely in the necessary combination of both memory and imagination in processes of remembering that Keightley and Pickering challenge and recalibrate the separation between the two, consolidating both into their concept of mnemonic imagination. If we accept their contention that remembering is more about construction than reproduction, and that memory and imagination are “mutually reliant and always inform each other’s activities,”[38] then imagination works at different levels of remembering. For the purposes of this article, I especially focus on three fundamental levels derived from Keightly and Pickering’s conceptualization: (1) the selection of memories (what is remembered), (2) the composition of memories (how they are set in relation to each other), and (3) the connection of oneself to memory. Building on this, we might set forth to consider the possibilities of mnemonic imagination not only in the context of individual memories but also in socially shared public memory. While selection and composition are integral parts of the memories in the context of the Zigeunerwagenfestival, it is the process of connection specifically that I will explore in this article.

Before doing so, it appears useful to add a qualification about the term public memory. Keightley and Pickering stress that memory is always situated and actualized within individuals. Postulating a social entity in possession of memory akin to the individual's at worst may obstruct an understanding of performances and practices in which public memory is created, shared, and mediated:

Memory does not exist in some sort of group mind or consciousness. Remembering is ordered and patterned by particular cultural practices, and these contribute to the social communication and exchange of memories, but at the same time there are aspects of remembering which can only be experienced on an individual basis.[39]

“Media of memory”[40] allow individuals to expand their personal memories with the knowledge of things past that they themselves did not live through. By participating in the festival, second- and third-generation postwar Sinti and Gadje are able to form meaningful, experiential bonds to this past. The waltz played by Markus, the wagon in the background, and the personal encounters during commemoration provide an experiential foundation on which the mnemonic imagination spins the connections of the self to these memories. Therein also lies the potential to expand one’s personal memory with those attributed to others across social or cultural boundaries.

Ricoeur proposes a threefold attribution of memory: (1) to oneself, the personal memory; (2) to one’s close relations, memories usually conceived of as family memories, intergenerational narratives, or accounts pertaining to particular social groups; and (3) to others, memories to which we do not have a direct social connection but which can become part of our second-hand experiences via memory media.[41] Connecting to Ricoeur’s third category, Alison Landsberg in her 2004 study on mass media and public memory introduced the term “prosthetic memory” to describe the personal and affective bonds that individuals form to the pasts of others. Mass media, Landsberg contends, create “transferential spaces”[42] where people are invited to form experiential bonds to memories, “outside a person’s lived experience, creating a portable, fluid, and nonessentialist form of memory.”[43]

Public memory, then, can be understood as “the interspace of dialogue activated by the mnemonic imagination, between the three attributions of memory identified by Ricoeur: ourselves, our close relations, and distant others.”[44] In the process of sharing lies the possibility, as Ricoeur emphasized, of change in categorical positionings,[45] meaning that the attribution of “our” memories and “their” memories are not fixed but rather fluid. This can be seen in Maro Drom’s attitude towards sharing family memories with outsiders, namely Gadje. It emerged in Markus’s speech that Maro Drom’s attitude towards sharing family memories with outsiders is rather uncommon. The festival acts as a catalyst for multiple transformations in memory constellations: exclusive family memories are transformed into inclusive memories that are also shared with strangers. Therein also lies the possibility of strangers becoming close relations. I argue that this is a crucial feature of the festival, as the transferential space in which the formulation and negotiation of “my,” “our,” and “their” memories enables “historical critique, and action in the present based upon it.”[46] Understood this way, musical performances of public memory provide a window into other pertinent fields such as identity formations and social orderings.

The Festival as Transferential Space

Ethnomusicology has long inquired into the role of music in processes of knowledge transmission and identity formations in relation to the past.[47] More recently, inquiries into sounding memories emerged that highlight the role of musical performances in processes of social remembering and public commemorations. For instance, Gregory Barz has shown how music was used in the Ugandan war against HIV/AIDS as a form of public pedagogy, but also how lost modes of traditional memory transmission may be regained through music.[48] Recent ethnomusicological studies addressing issues and theories of memory studies often focus on the “embodied, affective, and emotional aspects of practices of musical memorialization.”[49] Music is understood as providing an experiential dimension to the process of remembering, thereby allowing the formation of experiential bonds to the past on an affective level. For example, Federico Spinetti highlighted how music, in the context of the memorialization of Italian partisans, does not serve as a mere conduit of memory, but rather is used in the reformulation and recontextualization of such memories, setting them in dialogue with broader socio-political processes of memorialization.[50] Inquiring specifically into the role of music in commemorative music festivals, Monika Schoop applied Landsberg’s concept of prosthetic memory to the Edelweißpiratenfestival in Cologne.[51] Schoop sees the festival as a temporal and temporary mnemonic space which sets out to make the Edelweißpiraten “approachable” for later generations, making it a transferential space akin to other media of memory.[52]

Building on these studies, I contend that the Zigeunerwagenfestival as a transferential space enables the performance and exchange of (counter-)memories between different social groups. In this, the different levels of mnemonic imagination (selection, composition, and connection) play a pivotal part in communicating not only memories but also identities. Music, through its polyvalent character, its connections to and significance for German Sinti culture, provides a vast vocabulary for the mnemonic imagination. In the commemoration ceremony in which Markus Reinhardt told the audience about his family’s history, after which he played two songs that the Sinti considered to be their own music, we see how mnemonic imagination operates at several levels. Playing the waltz not only builds a direct musical connection to the Holocaust via the narrative of its origin, but it also channels pre-established tropes that provide Sinti and non-Sinti with a template to envisage a past that they only know from other memorial media. For the non-Sinti, these include first and foremost the movies about the Holocaust, many of which employ the violin as a representation for lament and sorrow. For the Sinti, the memorial media also include the stories of their elders. This in turn also serves as a vehicle for Markus to connect his family’s history to a larger narrative.

During another commemoration ceremony in 2019, Markus not only told the audience about how the musicians of his family had played for the Nazis in the concentration camps, but also added another episode in which his father saved one of Markus’s uncles by including him in his group even though the uncle did not play an instrument. This episode signifies another fundamental affordance of mnemonic imagination to imagine it otherwise. With the festival, as Markus told me in a conversation, they challenge their sole role as victims: “I can’t stand this, I never thought of us as victims, this cult of victims. I don’t want to be pitied. I want to show what we can do, to do something positive.”[53] With the selection of different memories, Markus provides an alternative to the victim narrative by emphasizing the agency of his family rather than their suffering.[54] The same sentiment was expressed by Markus at the end of his short speech, when he said that they are now at a point where they want to reach out. This signals a radical change in his attitude towards public commemoration. When I first met Markus, he told me that he did not like the idea of public commemoration. In fact, the yearly commemoration ceremony for the deported Sinti at the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz was and still is organized by non-minority members. Only in recent years has the participation of Sinti as well as Roma become more frequent. When I talked with Markus about this change, he replied:

This [the Zigeunerwagenfestival] is different. We have never been asked. Nobody included us. They always thought that they know what is best for us. But now, we are doing something, we know what is best for us and this is why our people are coming to the festival.[55]

We see that this form of commemoration is intimately connected to the formation and postulation of identities and social belonging. As the following demonstrates in greater detail, the mnemonic imagination not only provides Sinti and non-Sinti with connections to the past, but also reshapes and reframes questions pertaining to the present and the future along the lines of this is who we are, and this is where we are going.

Vignette 2: “Where Does the Journey Take Us?”—Discussing Sinti Cultural Politics

From June 7–9, the Zigeunerwagenfestival was held in Worringen, a more rural district of Cologne that is home to the majority of Sinti involved in the festival. “You will see,” Markus said to me, “it is going to be great; this is our place.” In Worringen, as with the other festival locations, musical acts, as Markus put it, presented “Gypsy culture in all its varieties.” This time, the wagon stood in the shadow of the communal church, with the stage and the food stands forming a U shape. The program included, among others, the Smiley Adler Quartet, who played instrumental jazz and swing, Tabor, who played a mixed set featuring their own compositions as well as more traditional pieces that they called Roma music, Dizzy Bone, who performed two rap songs in German and Romani, and the band Rumba Gitana, which played modernized flamenco pieces with elements of Latin music. On the second day, I was asked to participate in a group discussion inside the wagon in front of a small audience of about twenty people.

Co-organizer Jan Krauthäuser moderated the discussion in which Nina Reinhardt, a journalist and Markus’s sister, Roger Moreno Rathgeb, a composer and leader of the band Tabor, and two Sinti youths who represented the “next generation” took part. I, as the second non-Sinto next to Krauthäuser, was also included amongst the discussants. The discussion had the title “Wohin geht die Reise?” (Where does the journey take us?). We sat on antique wooden stools and a sofa around a living room table with a table runner and a candle on it. A large cabinet made of dark wood was placed at the head side. Other antique furniture, like a small side desk and decorated shelving, added to the feeling of actually being in someone’s home. On the walls hung reproductions of photographs depicting the Schwartz-Weiß-Platz and the exteriors and interiors of the wagons that had occupied the former “Gypsy camp” in the north of Cologne. It was in this ambience that we discussed the importance of language, music, and the maintenance of tradition for the future of minorities within Germany.

Nina told the participants about the life of her family, who used to live in such a wagon. From the very beginning, she made clear that they had not been living in the camps in Bickendorf and Roggendorf by choice, but that they had been forced into such a lifestyle. Nina, the youngest of the three siblings, did not grow up living in a wagon herself. Nevertheless, Nina shared mostly fond memories of her elder brothers, who spent their childhood in the wagon community. The discussion went on freely and passed from one subject to another. The pressing issue of losing one’s culture was brought forth by the moderator and then aroused lively participation from the audience. “The elders are our libraries,” said Nina, “and when the Nazis murdered them, they also burned our books and our knowledge.” When it came to discussing the possibility of formal schooling materials to educate children who spoke less and less Romani, two older Sintezze left the wagon in protest. As I was told later, they took offense at the discussion of such sensitive matters with Gadje, saying that they already had lost their culture and were not “real Gypsies.”

Despite this short interruption, the discussion went on and focused on the fine line between opening up to outsiders and safeguarding their culture. I was asked about my opinions and tried to point to other Roma and Sinti activists’ projects that involved both minority and majority members, such as the digital RomArchive, whose purpose is to promote self-representations of Roma and Sinti cultures and histories.[56] A Sintezza in the audience reminded participants that they had once trusted people like Eva Justin, who had learned their language and subsequently used her knowledge against them. While this was not disputed and the general concerns were not resolved, Nina nonetheless argued for a more open attitude. She emphasized the importance of seeking allies in and common goals with Gadje, saying that their culture not only bears value for Sinti, but that certain aspects of Sinti culture, including the cultural values that govern social interactions and the handling of children, the family, and elders, may also be relevant for society as a whole.

Various participants nodded their heads in agreement and stayed afterwards to tell Nina that they had no idea about the Sinti’s history and that they greatly appreciated their efforts. After one and a half hours, the discussion was brought to an end, and while the musical program outside continued with the band Tabor, I remained inside with my notebook, trying to make sense of the different issues and opinions I had just heard.

Inside the “Gypsy Wagon”: Mnemonic Imagination and Social Orderings

There had been several complaints via social media about this specific part of the festival program. For instance, one Sintezza, who criticized the festival for its name and its symbols that reinforce stereotypes, wrote that they should not discuss and share “minority interna” like language, culture, and beliefs with Gadje. Considering the critical literature about Romani culture that focuses on stereotypes, romanticism, and exoticisms as vehicles for repression and marginalization, it seems sensible to address at least some of these issues with regard to the festival’s centerpiece: the “Gypsy wagon.” From a critical point of view, the wagon can be interpreted as a complex sign in which several stereotypes converge. It signifies a cultural and a temporal distinction between minority and majority.[57] It invokes images of nomadism and romanticized freedom. In ethnomusicology, we find a multitude of similar phenomena analyzed in terms of strategic otherness and essentialism or self-exoticization,[58] a strategy usually employed by musicians navigating between self-expression and fulfillment of customers’ fantasies in a global market.[59] In short, the wagon initially evokes similar problems as the conceptual integration of imagination in memory: it is as such met with distrust, because it is supposed to belong to the realm of fantasy instead of facts.

During another discussion inside the wagon, Nina Reinhardt was confronted with a question from the audience. Coming from a non-minority member, the question was how the majority should approach stereotypes when dealing with Sinti. The man mentioned well-known examples such as Carmen, the “Gypsy” in fairy tales, and the idea of Roma and Sinti as nomads, which he, as he implied, had learned to be problematic. Nina replied that the wagon in itself is not a merely manufactured stereotype. She emphasized that her family had indeed lived in a wagon such as the one we were sitting in. Her brothers had been brought up in a wagon, as many others of their generation, especially those Sinti who lived in Cologne. Instead of meeting the expectation of this man, who like many other non-minority members used these opportunities in the festival to find answers to the question of “how to interact with them the right way,” Nina refused to give an easy answer that would resolve the various ambivalences surrounding the wagon. Rather, she encouraged the audience to accept these ambiguities. I later talked with her and Markus about the pitfalls of romanticizing life in the wagon. Markus said to me that of course it was not all good. The camp in Roggendorf was right next to a waste dump. They had been forced outside the city and lacked the infrastructure and living standards of the majority. But this did not change the fact that he remembers his youth fondly and experienced a strong communal cohesion and independence from the outside world.

It is again an empowering and agency-emphasizing interpretation that is put forth by Markus and the people from Maro Drom. To analyze the Zigeunerwagenfestival solely in terms of strategic or market-oriented self-exoticization overlooks the importance of such ambiguous symbols for cultural emancipation and identity constructions. In a group discussion I held with several family members, Carmen, herself a founding member of Maro Drom and married to Markus’s brother, discussed the significance of the wagon from her perspective. Addressing Nina, she said:

I don’t have the same memories as you do. My family has always been living in houses. But we had a caravan. During the school holidays in summer, we would always go on a journey. It was only for a couple of weeks but during that time I always felt like this was the way of life. I understand what life must have been like.[60]

Again, this could easily be put forth as another instance of romanticism or nostalgia towards an imagined past or an imagined “Gypsy life.” Rather than discrediting these sentiments, I want to highlight their importance in creating a “prosthetic memory.” The wagon functions as a powerful symbol that can be understood by both Sinti who had to or still do live in wagons and those who did not, providing a medium for a sense of belonging and the enactment of cultural identities. The festival featured a wide variety of musical acts, including music that is perceived as an expression of “Gypsyness.” This attribution to the music is felt rather than grounded in similarities in any musical parameters. In a conversation with Markus Reinhardt, he told me his understanding of what he calls “Gypsy music”:

There is no such thing as Gypsy music. We have always played the music of the countries we were living in and mixed it with what we already had. It is how the music is played that defines it. I can always hear when it is a Gypsy playing.[61]

In similar fashion, Markus’s niece Regina perceived the festival’s mixture of musical styles as an iconic expression of “Gypsyness” when she said to me: “Of course, all this is not exactly our music. But it has the same intensity. It is different but it has the same history, it comes from the same place. It is all linked, it fits together.”[62] In her article on Alsatian jazz manouche,[63] Siv B. Lie explores similar sentiments by Manouche jazz musicians and vividly demonstrates how sound is perceived as an icon of “ethnoracial difference.”[64] Lie uses the notion of “feeling” employed by her interlocutors as something that “confirms the emotional sincerity of the person performing.” Manouche listeners identity feeling in certain musical aspects, for instance in how the guitar is played. Chiefly among these aspects, Lie mentions timbre, playing techniques, and “tensions” built up during improvisations that are understood as icons of Manoucheness. She argues that the focus on “feeling,” or as Markus Reinhardt has put it, “the how the music is played,” reveals a naturalized understanding of “sonic manoucheness,”[65] which to them “is both enduringly embodied and sonically perceptible.”[66] For Markus, an interplay of virtuosity and emotional expressivity in playing conveys a sense of “Gypsyness.” By telling me that he knows “when it is a Gypsy playing,” he also conveys to me that I, as a Gadjo, do not. Claims such as these, Lie emphasizes, “should not be dismissed as delusion but rather assessed as a component of an ethnoracial aesthetic discourse that has real material effects.”[67]

It is a strategic and often ambiguous play in which the people of Maro Drom employ music as a way to signify a belonging to a larger, culturally rich and diverse Romani culture, while at the same time emphasizing their distinctiveness as German Sinti in conversations. The music as well as the other parts of the festival taken together form the transferential space, in which family memories are framed and shared with outsiders. At the same time, cultural—or, as Lie has it, “ethnoracial”—constellations are re-negotiated and re-enforced, which grounds the mnemonic imagination in an emergent field of social belonging.

Following this line of thought, a qualification of the concept of prosthetic memory seems in order. Landsberg developed her ideas through the analysis of mass media, especially movies that provide accounts of traumatic historical events such as the Holocaust. As commodities, these movies circulate rather freely across societies and may be consumed and incorporated across social boundaries. Landsberg contends therefore that prosthetic memories do not “naturally belong to anyone” but are “portable, fluid and nonessentialist” forms of memory.[68] In the context of the festival, we can already detect crucial differences: while movies, as analyzed by Landsberg, may be consumed by nearly anyone without regard for or connection to their ‘authors,’ the festival poses a transferential space where the authors are very much alive and provide their own interpretations and frameworks. As family memories provide “formative material for the mnemonic quest for identity,”[69] they are transformed through processes that work on the same levels as the mnemonic imagination. Considering the music and the festival’s program, selection, composition, and connection not only appear as relevant processes of mnemonic imagination, but they are also key in terms of cultural identity and social ordering, laying open the close connections between performances of social memory and performances of cultural identity.

So far, I have discussed music as well as the festival as a “transferential space” in a more metaphorical sense. We have already ventured into the field of materiality by considering the special significance of the wagon, which allows festival participants to imagine a time that might have been.[70] The third and final vignette follows this trajectory and sheds light on aspects of spatiality and the importance of emplaced remembering in conjunction with mnemonic imagination.

Vignette 3: A Guided Tour through Cologne

The third installment of the festival took place from October 3–7 in Ehrenfeld.[71] In contrast to the previous two festivals in Deutz and Worringen, the wagon now occupied a central place in Cologne. In a way, the Ehrenfeld festival was seen also as a homecoming. Compared to Deutz, where the place was chosen for its proximity to the memorial at the train station, or Worringen, which was still the home of many Sinti, Ehrenfeld and the neighboring district Bickendorf had once been the home of many Sinti families before they were deported. This is why Markus said during the introductory speech to the festival in Ehrenfeld: “We are back.” In its third installment, the festival went louder and bigger. It featured more musicians and more workshops. Instead of a discussion, the festival included a guided tour through Bickendorf and Ehrenfeld. The tour guides were Nina Reinhardt and Markus’s partner Krystiane Vajda, who led a group of about twenty-five people to significant places in the districts. Starting from the festival space on the Neptunplatz in Ehrenfeld, they first brought the group to the memorial at the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz in Bickendorf. Today, the former square has been replaced by a number of smaller businesses, supermarkets, and storage facilities. Nothing but a memorial plaque on a wall between the sidewalk and a railway bridge evidences its history. Standing on the sidewalk in front of the plaque, Nina and Krystiane explained the history of this place and its significance for the Sinti. They provided the group with photographs which showed the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz as it had been eighty years ago. Some showed rows of wagons similar to the one standing in Ehrenfeld, and some showed people posing in front of their homes. Many of these pictures are reprints of photos made by the Rassenhygienische Forschungsstelle. Other photos, taken after the war, showed for instance older relatives of Nina and Markus as young boys, as members of a soccer team. The group went on, moving back towards Ehrenfeld, and made a stop at a bar-restaurant where Markus and members of his band awaited them. Nina and Krystiane introduced Sinti witnesses who shared their memories of the Schwarz-Weiß-Platz while Markus and the other musicians recreated a crucial element in a Sinti musician’s life before and after the war. Markus explained that his father and his uncles made their living by playing in different restaurants and bars each night. As radios and record players had been rare and expensive, live music was a welcome amusement for many people who could afford to eat out. This practice was called “Ständeln” and Markus himself remembered how he had accompanied his father’s group in the 1970s, before this practice slowly died out. The group then set out to play well-known German songs such as “In dieser Stadt” or “Für mich soll’s rote Rosen regnen” by the German chanson singer Hildegard Knef.[72] In between these songs, Markus told the audience “These are the songs that they [our elders] always performed for the Gadje. But they also loved these songs because they are great. They loved to play and to listen to them.” As they continued to play, the audience swayed along and every now and then joined in to sing the refrain of a song. In between the songs, Markus told smaller anecdotes that highlighted the significance of “Ständeln” for the Sinti community as a whole. “We, as musicians, we had been going out. We were not simply musicians, but we also brought news from outside into our community. We were some kind of messengers.” After about 40 minutes they finished their set, and people applauded and gave some donations for the planned tour with the wagon from Auschwitz to Cologne. The tour group, accompanied by the musicians, then went back to the festival space where the evening program ensued.

Claiming the Memoryscape: Mnemonic Imagination and Emplacement

This last vignette adds another facet to the festival’s role as transferential space. It was not limited to the different festival grounds in Cologne, which carry special significance to the Sinti; with the guided tour, participants were also brought outside the actual festival space to other important places in the city. Therefore, this last section of the article is dedicated to the significance of places in public memory practices. Drawing on a large corpus of (ethno-)musicological literature that inquires into the relationships between music and social spaces,[73] this last part examines how the festival’s mnemonic performances speak to both spatialization processes and social formations.

Keightley and Pickering, Landsberg, and others have argued that through social mediation, second-hand memories can, to varying degrees, become first-hand memories. The festival provides numerous opportunities in which the mnemonic imagination of individuals may select from as well as compose and connect to the publicly shared memories. Following Landsberg, Monika Schoop highlights the importance of experiences in creating prosthetic memories. Music shapes these experiences and impacts, on an affective level, individual memory.[74] This first-hand experience is necessarily tied to a specific place in a specific time. Considering the spatial aspects of the festival and the guided tour, it becomes apparent that not only music but also the first-hand experience of being in a place and connecting memories to it form profoundly affective bonds to the past. To stand “where they had once lived” enables individuals “to make sense of their lives in relation to the lives of others and to their surroundings, situating themselves in time and place.”[75] It makes memory tangible.

Not only do places shape memories, but they are also shaped by them, as Steven Feld and Keith Basso have demonstrated in their seminal volume Senses of Space. The guided tour provided the participants with new memories which have the potential to transform these places. By showing pictures and sharing family memories, Nina and Krystiane formed a connection between the actual place and its history. To be clear, the tour wove together not only one place but multiple places. As anthropologist Tim Ingold argues, places are like knots of entwined trails.[76] As more and more people cross, visit, or inhabit these knots, they are connected and endowed with different meanings, making the knots denser. The festivals and the guided tours tied together the various meaningful places that spread across Cologne into a new network, or rather, a new memoryscape.[77]

While the trails and knots in this map represent the (temporary) reconfiguration of urban space, the memoryscape described by these lines is not purely spatial but also extends into the temporal and the social sphere. The festivals lay open the otherwise invisible histories and significances of places, creating connections between the past and the present. However, they also connect various social spheres which would normally not intersect, by bringing together minority and non-minority members, musicians, politicians, educators, artists, historians, and ethnomusicologists, thereby extending the memory network far beyond the city’s boundaries. In doing so, the Sinti families of Maro Drom inscribe themselves and their history into the city and its memoryscape, thus claiming their own space while simultaneously reaffirming their distinct cultural and social position within German society.

Conclusion

The ethnographic exploration of festivals as transferential spaces of public memory has unveiled the complex intersections of family memories, social orderings of space, and cultural belonging. By focusing on mnemonic imagination, the article has also highlighted the entanglement between the formation of socially shared memories and public representations of Sinti cultural identity. The festival’s program, especially during the discussions and the commemorative ceremonies, underlines memory’s directedness not only towards the past, but also towards the present and the future. It is geared towards change and development, which was best explained by Markus during the first commemoration ceremony in Deutz. The festival provided an intersectional transferential space in which, through processes of selection, composition, and connection, Sinti and non-Sinti created sounding memories of an otherwise marginalized and silenced past. As WWII and the persecution by the Nazis has left many Sinti disconnected from their culture and their past, the festival provided points of references to fill in the gaps. The selection of memories, as we have seen, not only determines the contents of public memory of WWII but is also directly tied to the representation of cultural identity. During the festival, the frequent statements of Markus Reinhardt and the members of Maro Drom that “this is our history” and “this is who we are” are both realized and tied together.

Early civil rights activists had to fight for the minority group’s recognition as victims of genocide, which was formally achieved only in 1982. By emphasizing agency rather than victimhood, the festival also exemplifies a comparably new attitude towards WWII memory and social activism. This attitude employs mnemonic imagination in new and sometimes challenging ways. In this, I argue, also lies the potential for reconfigurations in the German memory culture. Performances of public memory such as the festival provide a space in which sounding memories of different minorities reveal their capability in forming and establishing new connections between minority and majority members.

Bibliography

- Barz, Gregory. Singing for Life: HIV/AIDS and Music in Uganda. New York: Routledge, 2006.

- Bastian, Till. Sinti und Roma im Dritten Reich. Geschichte einer Verfolgung. Munich: C. H. Beck, 2001.

- Bhatia, Lieselotte, and Stephan Stracke, eds. Vergessene Opfer. Die NS-Vergangenheit der Wuppertaler Kriminalpolizei. Bremen: De Noantri, 2018.

- Blumer, Nadine. “From Victim Hierarchies to Memorial Networks: Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial to Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism.” PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2011.

- Bohlman, Philip V. “Fieldwork in the Ethnomusicological Past.” In Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, edited by Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley, 139–62. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997.

- Constantine, Simon. Sinti and Roma in Germany (1871–1933): Gypsy Policy in the Second Empire and Weimar Republic. New York: Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351185516.

- Engbring-Romang, Udo. Fulda. Auschwitz. Zur Verfolgung der Sinti in Fulda und Umgebung. Seeheim, Germany: i-Verb.de, 2006.

- Erll, Astrid. Memory in Culture. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230321670.

- Fabian, Johannes. Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object. New York: Columbia University Press, 1983.

- Feld, Steven, and Keith H. Basso, eds. Senses of Place. Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 1996.

- Fings, Karola. “Nationalsozialistische Zwangslager für Sinti und Roma.” In vol. 9 of Der Ort des Terrors. Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, edited by Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel, 192–217. Munich: C. H. Beck, 2009.

- Fings, Karola. Sinti und Roma. Geschichte einer Minderheit. Munich: C. H. Beck, 2016. https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406698491.

- Fings, Karola, and Frank Sparing. Rassismus, Lager, Völkermord: Die nationalsozialistische Zigeunerverfolgung in Köln. Cologne: Emons, 2005.

- Frishkopf, Michael, and Federico Spinetti, eds. Music, Sound, and Architecture in Islam. Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018.

- Giesen, Bernhard. “The Trauma of Perpetrators. The Holocaust as the Traumatic Reference of German National Identity.” In Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, edited by Jeffrey Alexander, Ron Eyerman, Bernhard Giesen, Neil Smelser, and Piotr Sztompka, 112–154. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004. https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520235946.003.0004.

- Hofman, Ana. “‘We are the Partisans of Our Time’: Antifascism and Post-Yugoslav Singing Memory Activism.” Popular Music and Society 44, no. 2 (2021): 157–174. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2020.1820782.

- High, Steven. “Mapping Memories of Displacement: Oral History, Memoryscapes, and Mobile Methodologies.” In Place, Writing and Voice in Oral History, edited by Shelley Trower, 217–231. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230339774_11.

- Ingold, Tim. “Against Space: Place, Movement, Knowledge.” In Boundless Worlds: An Anthropological Approach to Movement, edited by Peter W. Kirby, 29–44. Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2008.

- Kapralski, Slawomir. “Introduction.” In Beyond the Roma Holocaust: From Resistance to Mobilisation, edited by Thomas M. Buchsbaum and Slawomir Kapralski, 11–17. Krakow: Universitas, 2017.

- Keightley, Emily, and Michael Pickering. The Mnemonic Imagination: Remembering as Creative Practice. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137271549.

- Kenrick, Donald, and Grattan Puxon. Sinti und Roma. Die Vernichtung eines Volkes im NS-Staat. Göttingen: Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker, 1981.

- Landsberg, Alison. Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture. New York: Columbia University Press, 2004.

- Lie, Siv B. “The Politics of “Understanding”: Secrecy, Language, and Manouche Song.” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40, no. 1 (2017): 96–113. https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1213404.

- __________. “Music That Tears You Apart: Jazz Manouche and the Qualia of Ethnorace.” Ethnomusicology 64, no. 3 (2020): 369–393. https://doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.64.3.0369.

- MacMillen, Ian. “Affective Block and the Musical Racialisation of Romani Sincerity.” Ethnomusicology Forum 29, no. 1 (2020): 81–106. https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2020.1815551.

- Malvinni, David. The Gypsy Caravan: From Real Roma to Imaginary Gypsies in Western Music and Film. New York: Routledge, 2004. https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203490068.

- Markovic, Alexander. “’So That We Look More Gypsy’: Strategic Performances and Ambivalent Discourses of Romani Brass for the World Music Scene.” Ethnomusicology Forum 24, no. 2 (2020): 260–285. https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2015.1048266.

- Matras, Yaron, and Gilad Margalit. “Gypsies in Germany—German Gypsies? Identity and politics of Sinti and Roma in Germany.” In The Roma: A Minority in Europe, edited by Roni Stauber and Raphael Vago, 103–116. Budapest: Central European University Press. 2007.

- von Mengersen, Oliver. “The impact of the Holocaust on the Sinti communities in post-war Germany.” In Beyond the Roma Holocaust: From Resistance to Mobilisation, edited by Thomas M. Buchsbaum and Slawomir Kapralski, 59–72. Krakow: Universitas, 2017.

- Michaelsen, René. “‘Meine Lieder sind anders’: Hildegard Knef and the Idea(l) of German Chanson.” In Made in Germany: Studies in Popular Music, edited by Oliver Seibt, Martin Ringsmut, and David-Emil Wickström, 165–174. New York: Routledge, 2020. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351200790-21.

- Ricoeur, Paul. Memory, History, Forgetting. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004. https://doi.org/10.7208/chicago/9780226713465.001.0001.

- Romero, Raúl R. Debating the Past: Music, Memory and Identity in the Andes. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Rose, Romani. Bürgerrechte für Sinti und Roma: das Buch zum Rassismus in Deutschland: Heidelberg: Zentralrat Deutscher Sinti und Roma, 1987.

- Schoop, Monika E. ““A Living Memorial for the Edelweißpiraten”: Musical Memories of Cologne’s Anti-Hitler Youth,” Popular Music and Society 44, no. 2 (2021). https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2020.1820785.

- Shapiro, Paul A., and Robert M. Ehrenreich, eds. Roma and Sinti: Understudied Victims of Nazism, Symposium Proceedings, Washington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2002.

- Shelemay, Kay Kaufman. Let Jasmine Rain Down: Song and Remembrance among Syrian Jews. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998.

- Silverman, Carol. “Music, Emotion, and the “Other”. Balkan Roma and the Negotiation of Exoticism. In Interpreting Emotions in Russia and Eastern Europe, edited by Mark D. Steinberg and Valeria Sobol, 410–453. DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2021.

- ———. Romani Routes: Cultural Politics and Balkan Music in Diaspora. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012.

- Simon, Roger. The Touch of the Past: Remembrance, Learning and Ethics. Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave MacMillan, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-137-11524-9.

- Spinetti, Federico. “Punk Rock on the Gothic Line: Resounding the World War II Antifascist Resistenza in Contemporary Italy.” Popular Music and Society 44, no. 2 (2021): 212–232. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2020.1820785.

- Spinetti, Federico, Monika E. Schoop, and Ana Hofman. “Introduction to Music and the Politics of Memory: Resounding Antifascism across Borders.” In Popular Music and Society 44, no. 2 (2021): 119–138. https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2020.1820780.

- Tyrnauer, Gabrielle. “‘Mastering the Past’: Germans and Gypsies.” In Gypsies: An Interdisciplinary Reader, edited by Diane Tong, 99–112. New York: Garland Publishing, 1998 [1982].

- Weisz, Zoni. Der vergessene Holocaust: Mein Leben als Sinto, Unternehmer und Überlebender. Munich: dtv, 2018.

- Weiß-Wendt, Anton, ed. The Nazi Genocide of the Roma: Reassessment and Commemoration. Berlin: De Gruyter, 2013.

- Whiteley, Sheila, Andy Bennett, and Stan Hawkins, eds. Music, Space and Place: Popular Music and Cultural Identity. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2004.

- Wippermann, Wolfgang. “Auserwählte Opfer?” Shoah und Porrajmos im Vergleich. Eine Kontroverse. Leipzig: Frank und Timme, 2012.

- Zimmermann, Michael. “The Berlin Memorial for the Murdered Sinti and Roma: Problems and Points for Discussion.” Romani Studies 17, no. 1 (2007): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.3828/rs.2007.1.

Deutz is a district in Cologne to the east of the Rhine. The locale is significant to the festival in the way that it follows in the footsteps of precursor festivals featuring music by Sinti and Roma that were also held in Deutz. Even more significant is the proximity of the festival space to the Deutz railroad station from whence many members of the Sinti minority had been deported to concentration camps during the Nazi regime.

Karola Fings and Frank Sparing state that 938 Gypsies had been deported from Cologne in May 1940 alone. The total number of persecuted and deported Sinti is significantly higher. See Rassismus, Lager, Völkermord (Cologne: Emons, 2005), 345.

The committee understands itself as a group of cultural activists of both minority and non-minority members.

The other installations took place in Worringen and Ehrenfeld. Both districts bear further significance for the Sinti community in Cologne. While today, a majority of the older Sinti families from Cologne live in the outer districts Worringen and Roggendorf, many remember their families having lived and worked in Ehrenfeld before they had been evicted from their homes under the Nazis. In 2019, the festival returned to Ehrenfeld and branched out beyond the city of Cologne to Dortmund, where the wagon was part of the “Gypsy Festival.”

The members of Maro Drom regularly encourage Gadje (non-minority members) to use the term “Zigeuner” (Gypsy) in both public contexts such as the festival, as well as in private conversations. This, as well as the fact that they used this potentially derogatory term, has given rise to criticism from various German Sinti and Roma organizations. In academic literature, Sinti are usually categorized as a sub-group of the Roma. As the German term “Sinti and Roma”—which is the preferred term in political contexts—suggests, many Sinti are critical of this subordination and argue for the recognition of their cultural and historical distinctiveness. See Yaron Matras and Gilad Margalit, “Gypsies in Germany—German Gypsies? Identity and Politics of Sinti and Roma in Germany,” in The Roma: A Minority in Europe, ed. Roni Stauber and Raphael Vago (Budapest: Central European University Press, 2007), 105–8. Markus Reinhardt justifies his usage by echoing arguments from a larger discussion about inclusion and the scale of the different terms. In his eyes, the term “Zigeuner” means all Romani people, whereas “Sinti and Roma” only includes two specific groups. Similar arguments also emerged in the debates concerning the Memorial to Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism in Berlin; see for instance Nadine Blumer, “From Victim Hierarchies to Memorial Networks: Berlin’s Holocaust Memorial to Sinti and Roma Victims of National Socialism” (PhD diss., University of Toronto, 2011); and Michael Zimmermann, “The Berlin Memorial for the Murdered Sinti and Roma: Problems and Points for Discussion,” Romani Studies 17, no. 1 (2007): 1–30, https://doi.org/10.3828/rs.2007.1.

Especially: Paul Ricoeur, Memory, History, Forgetting (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2004); Emily Keightley and Michael Pickering, The Mnemonic Imagination: Remembering as Creative Practice (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137271549; Alison Landsberg, Prosthetic Memory: The Transformation of American Remembrance in the Age of Mass Culture (New York: Columbia University Press, 2004).

Astrid Erll, Memory in Culture (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 113–31, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230321670.

See Simon Constantine, Sinti and Roma in Germany (1871–1933): Gypsy Policy in the Second Empire and Weimar Republic (New York: Routledge, 2020), https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351185516; Karola Fings, Sinti und Roma. Geschichte einer Minderheit (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2016), 40–59, https://doi.org/10.17104/9783406698491; Donald Kenrick and Grattan Puxon. Sinti und Roma. Die Vernichtung eines Volkes im NS-Staat, (Göttingen: Gesellschaft für bedrohte Völker, 1981), 19–39.

See Till Bastian, Sinti und Roma im Dritten Reich. Geschichte einer Verfolgung (Munich: C. H. Beck, 2001), 33–76; Fings “Sinti und Roma,” 62–91; Kenrick and Puxon “Sinti und Roma,” 106–36.

See for instance Paul A. Shapiro and Robert M. Ehrenreich, Roma and Sinti: Understudied Victims of Nazism (Washington: United States Holocaust Memorial Museum, 2002); and Wolfgang Wippermann, “Auserwählte Opfer?” Shoah und Porrajmos im Vergleich. Eine Kontroverse (Leipzig: Frank und Timme, 2012).

See for instance Bastian, “Sinti und Roma im Dritten Reich”; Karola Fings, “Nationalsozialistische Zwangslager für Sinti und Roma,” in Der Ort des Terrors: Geschichte der nationalsozialistischen Konzentrationslager, vol. 9, ed. Wolfgang Benz and Barbara Distel (München: Beck, 2009), 192–217; Romani Rose, Bürgerrechte für Sinti und Roma: das Buch zum Rassismus in Deutschland (Heidelberg: Zentralrat Deutscher Sinti und Roma, 1987); Anton Weiß-Wendt, The Nazi Genocide of the Roma: Reassessment and Commemoration (Berlin: de Gruyter, 2013).

See for instance: Lieselotte Bhatia and Stephan Stracke, Vergessene Opfer. Die NS-Vergangenheit der Wuppertaler Kriminalpolizei, (Bremen: De Noantri, 2018); Udo Engbring-Romang, Fulda. Auschwitz. Zur Verfolgung der Sinti in Fulda und Umgebung (Seeheim, Germany: i-Verb.de, 2006).

See for instance: Bastian, “Sinti und Roma im Dritten Reich”; Kenrick and Puxon, “Sinti und Roma.”

Zoni Weisz, Der vergessene Holocaust. Mein Leben als Sinto, Unternehmer und Überlebender (Munich: dtv, 2018).

Slawomir Kapralski, “Introduction,” in Beyond the Roma Holocaust: From Resistance to Mobilisation, ed. Thomas M. Buchsbaum and Slawomir Kapralski (Krakow: Universitas, 2017), 11.

Oliver von Mengersen, “The Impact of the Holocaust on the Sinti Communities in Post-war Germany,” in Beyond the Roma Holocaust: From Resistance to Mobilisation, ed. Thomas M. Buchsbaum and Slawomir Kapralski (Krakow: Universitas, 2017), 65.

Bernhard Giesen, “The Trauma of Perpetrators: The Holocaust as the Traumatic Reference of German National Identity,” in Cultural Trauma and Collective Identity, ed. Jeffrey Alexander, Ron Eyerman, Bernhard Giesen, Neil Smelser, and Piotr Sztompka (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2004), 117, https://doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520235946.003.0004. The term aptly characterizes postwar Germany’s attitude towards its immediate past; see also König, this volume.

Von Mengersen, “The impact of the Holocaust,” 67; Rose, “Bürgerrechte für Sinti und Roma.”

Fings and Sparing make it clear not only that the continued discrimination and marginalization was promoted by former Nazi-politicians and administrators who were still in office but also that the general public strongly recommended and supported their actions (Rassismus, Lager, Völkermord, 347–72).

My translation. Unless stated otherwise, all translations are my own.

For a concise portrayal and analysis of this period, see for instance Blumer, “From Victim Hierarchies to Memorial Network,” 98–129.

A type of folk dance from Hungary often associated with Roma.

See for instance: Raúl Romero, Debating the Past: Music, Memory and Identity in the Andes (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2001); Philip Bohlman, “Fieldwork in the Ethnomusicological Past,” in Shadows in the Field: New Perspectives for Fieldwork in Ethnomusicology, ed. Gregory F. Barz and Timothy J. Cooley (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1997), 139–62; Kay Kaufman Shelemay, Let Jasmine Rain Down: Song and Remembrance among Syrian Jews (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1998).

Gregory Barz, Singing for Life: HIV/AIDS and Music in Uganda (New York: Routledge, 2006).

Federico Spinetti, Monika E. Schoop, and Ana Hofman, “Introduction to Music and the Politics of Memory: Resounding Antifascism across Borders,” Popular Music and Society 44, no. 2 (2021): 119–138, https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2020.1820780.

Federico Spinetti, “Punk Rock on the Gothic Line: Resounding the World War II Antifascist Resistenza in Contemporary Italy,” Popular Music and Society (2020): 212–232, https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2020.1820785.

The annual festival is performed as a “living memorial” to a German youth resistance group under the Nazi regime, called Edelweißpiraten.

Monika E. Schoop, “‘A Living Memorial for the Edelweißpiraten’: Musical Memories of Cologne’s Anti-Hitler Youth,” Popular Music and Society 44, no. 2 (2021): 193–211, https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2020.1820785.

Johannes Fabian wrote extensively on this “denial of coevalness.” See especially Time and the Other: How Anthropology Makes Its Object (New York: Columbia University Press, 1983), 25–35.

See for instance David Malvinni, The Gypsy Caravan: From Real Roma to Imaginary Gypsies in Western Music and Film (New York: Routledge, 2004), 43–70, https://doi.org/10.4324/9780203490068; Alexander Markovic, “‘So That We Look More Gypsy’: Strategic Performances and Ambivalent Discourses of Romani Brass for the World Music Scene” Ethnomusicology Forum 24, no. 2 (2020): 260–285, https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2015.1048266; and Siv B. Lie “Music That Tears You Apart: Jazz Manouche and the Qualia of Ethnorace,” Ethnomusicology 64, no. 3 (2020): 369–393, https://doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.64.3.0369. Gayatri Spivak’s notion of “strategic essentialism” has been adopted as a salient concept in ethnomusicology. Regarding Roma, music, and strategic essentialism/self-exoticization, see especially Carol Silverman. Romani Routes: Cultural Politics and Balkan Music in Diaspora (Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press, 2012); and Carol Silverman, “Music, Emotion, and the ‘Other’: Balkan Roma and the Negotiation of Exoticism,” in Interpreting Emotions in Russia and Eastern Europe, ed. Mark D. Steinberg and Valeria Sobol (DeKalb: Northern Illinois University Press, 2021), 410–453.

Manouche is the most common term for and self-appellation of French Sinti.

Siv B. Lie, “The Politics of “Understanding”: Secrecy, Language, and Manouche Song,” Ethnic and Racial Studies 40, no. 1 (2017): 104, https://doi.org/10.1080/01419870.2016.1213404.

Siv B. Lie, “Music That Tears You Apart,” 384. Similar arguments can be found with reference to intersubjective assessments of “primal emotionality” in Alexander Markovic, “So That We Look More Gypsy,” 276; the “capturing of emotion in music” in Carol Silverman, “Romani Routes,” 23; and the combination of virtuosity and improvisation creating emotion in David Malvinni, “The Gypsy Caravan,”10. For an excellent overview, see Ian MacMillen, “Affective Block and the Musical Racialisation of Romani Sincerity,” Ethnomusicology Forum 29, no. 1 (2020): 81–106, https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2020.1815551.

For the special significance of Hildegard Knef, see René Michaelsen, “‘Meine Lieder sind anders’: Hildegard Knef and the Idea(l) of German Chanson,” in Made in Germany: Studies in Popular Music, ed. Oliver Seibt, Martin Ringsmut, and David-Emil Wickström (New York: Routledge, 2020), 165–174, https://doi.org/10.4324/9781351200790-21.

See for example: Steven Feld and Keith Basso, Senses of Place (Santa Fe, NM: School of American Research Press, 1996); Sheila Whiteley, Andy Bennett, and Stan Hawkins, Music, Space and Place: Popular Music and Cultural Identity (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2004); Michael Frishkopf and Federico Spinetti, Music, Sound, and Architecture in Islam (Austin: University of Texas Press, 2018).

Schoop, “A Living Memorial for the Edelweißpiraten”; Ana Hofman, “‘We are the Partisans of our Time’: Antifascism and Post-Yugoslav Singing Memory Activism,” Popular Music and Society 44, no. 2 (2021): 157–174, https://doi.org/10.1080/03007766.2020.1820782.

Tim Ingold, “Against Space: Place, Movement, Knowledge,” in Boundless Worlds: An Anthropological Approach to Movement, ed. Peter W. Kirby, (Oxford: Berghahn Books, 2008), 33.

High, Steven, “Mapping Memories of Displacement: Oral History, Memoryscapes, and Mobile Methodologies,” in Place, Writing and Voice in Oral History, ed. Shelley Trower (Basingstoke, UK: Palgrave Macmillan, 2011), 217, https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230339774_11.