“Bailo Desafiando al Hombre”[1]:

Isnavi Cardoso Díaz Performing the Politics of Culture in Cuban Columbia

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

During the 1990s and 2000s, public folkloric performances in Havana provided a site for performing the politics of culture in a changing nation. This article presents a close reading of a gender-bending performance of the style of rumba known as columbia, an icon of national culture in the socialist era and a staple of public folkloric shows to this day. Taking alterations of the standard style and performance interactions as evidence, I examine how Isnavi Cardoso Díaz negotiates her identity as a professional folkloric dancer and legitimate performer of rumba by dancing columbia. The concepts of discourse and embodiment frame an analysis to show how the subjective significance of performance emerges through the collective enactment of the dance-music event among a set of subject positions that parallel verbal discourse. With Cardoso as the main performer, the event may be parsed in terms of how her movements and dyadic interactions with other performers locate her among a community of interpreters within the broader discursive system of public folkloric shows in Havana. With Cardoso at the center, this multi-modal form of communication encompasses musical sound, movement, language, and emotion and comprises part of an ongoing critical conversation on national culture in Cuba.

In August 2009, while conducting field work in Havana, I witnessed a woman’s gender-bending performance of a style of folkloric dance-music that has typically been performed by men. That night, Isnavi Cardoso Díaz danced columbia as part of a folkloric show staged by the group Oba Ilú at the Yoruba Cultural Association of Cuba.[2] A sub-style of the secular rumba genre and an icon of national culture during the socialist era, columbia is performed by a percussion ensemble, solo singer, chorus, and dancers; it is distinguished from other styles of rumba by its rhythms and solo dance. Although several women have been known for dancing columbia, when it is presented as a form of national culture in public folkloric shows in Havana, it has typically been performed only by men. This is despite the fact that all professionally trained folkloric dancers learn the dance and that many Cuban dancers in the diaspora teach columbia to both men and women.[3] Nevertheless, it is still somewhat rare to see women in Cuba perform the solo dance in the context of public folkloric shows (espectáculos folklóricos).[4] So, while Oba Ilú presented a program that conforms with expectations in terms of format and repertoire, Cardoso’s performance departs from the standard style and the way that folklore as national culture represents Cuban identity.

While Cardoso’s dancing was supported by some members of the ensemble, most notably by the group’s director, Gregorio Hernández (1936–2012), the performance provoked controversy. Her transgression of gender roles not only challenges a central mode of social power, it alters the way public folkloric shows characterize national culture and its subjects. Analyzing Cardoso’s dancing in the context of the collective enactment of the dance-music event, I argue that it locates her among a community of musicians and dancers who subtly re-frame folkloric performances of rumba as part of an ongoing critical conversation on national culture, identity, and belonging within the Cuban nation. In this article, I present a close reading of Cardoso’s dancing using the concepts of discourse and embodiment to explore how she uses folkloric performance to negotiate her identity as a professional dancer through alterations of the standard style and interactions with her fellow performers and show how these alterations challenge standard notions of national culture. In my exploration of these issues, I demonstrate how public folkloric shows operate as a site for performing the politics of culture in contemporary Cuba.

With a dual mission of education and entertainment, public folkloric shows (espectáculos folklóricos) present narratives of the nation through the dramatic staging of folkloric dance-music and characterizations of its subjects.[5] The shows project a view of national culture rooted in the work of Fernando Ortiz (1888–1969) and shaped by the institutional processes and ideologies of socialist Cuba. Described by Katherine J. Hagedorn as a secular genre of public performance developed shortly after the revolution, folkloric shows demonstrate a blend of ethnographic methods, modern dance technique, and dramatic staging.[6] The shows follow a predictable sequence, draw on a familiar repertoire, and have a standard style of performance that emerged from the pedagogy and performances of the CFNC (Conjunto Folklórico Nacional de Cuba). One dancer called their style the “gold standard.”[7] Reinforced by the planilla or employment and payroll system, the standard style of the CFNC became so definitive of Afro-Cuban folklore that religious communities who were originally its models have adopted its styles of dance.[8] The embodiment of these standards reinforces not only ways of dancing but also ways of interpreting and explaining the meanings of the dance and the ways it expresses identity.

Ideas and vocabulary reminiscent of Ortiz’s writings were part of how performers explained the music and dance.[9] From details about the origins of rumba in Congo culture to the idea that characteristic dance movements were in their blood, dancers expressed a variety of ideas related to the Ortizian view and used these understandings to inform their performance choices.[10] By contrast, some musicians, including Hernández, disputed some ideas and warned of errors and misunderstandings in the canonical interpretations of rumba and Afro-Cuban religious music and dance. While Ortiz’s scholarship has been reevaluated and updated in recent years, disputes reflect the use of folklore as a site of cultural politics and alteration a potential mode of self-definition in the face of some of the more painful contradictions of national culture.

Despite the expanded public presence of Afro-Cuban folklore after the revolution, the drive for national unity framed use of the term “Afro-Cuban” as redundant or divisive.[11] To say “Cuban” implies the inclusion of people of color within the nation, without the implication of a marked category. In line with this stance on national identity, public discourse excluded vocabulary that expressed historical and social specificity of black people’s experiences. In light of this, the term Afro-Cuban can bring to light unacknowledged aspects of history and identity, which some would argue exist within the Cuban nation and its history. In this sense, as a matter of self-definition, it might be desirable to highlight the particularity of Afro-Cuban identity. In fact, a movement addressing structural racism in the Cuban system has emerged over the past decades. Furthermore, scholars have observed that folkloric performances tend to reproduce racializing discourse while drawing on Afro-Cuban expressive traditions to create a politically legitimate identity.[12] This has led some to reject Afro-Cuban folklore in its public and official expressions as politically anodyne, if not mercenary.[13] By equating folkloric performance with either the reproduction of racializing discourse or the reinforcement of an official national culture, important sources of musical meaning are overlooked. On the one hand, these perspectives neglect the gendered dynamics of racialized identities in performance. On the other, they ignore the power and meaning of dance-music performance for participants in their immediate social and institutional contexts.

While themes of Ortizian scholarship inform the details of performance, a prime tenet of this view uses Afro-Cuban folklore to express a mixed but homogenous national culture, referred to by some musicologists in Cuba as “mono-ethnic and multi-racial.”[14] While this creates important roles for Afro-Cuban men as “carriers of culture,” Jossianna Arroyo and others observe that racial hierarchies remain tacit and subordinate men of color to white counterparts through a discourse of brotherhood.[15] This gendered view of national culture has been perpetuated in the context of histories of anti-black political violence and taboos against Afro-Cuban political mobilization and social autonomy. In this way, gender alliances and hierarchies contribute to silencing the lived experience of race and disenfranchise women of color in distinct ways. Writing about the textuality of Ortiz’s works on folklore, Arroyo explains how this symbolic system locates the black mother outside of the social order.[16] Considered to be the origin of mixture, the black woman is thus powerful but dangerously destabilizing of identity.[17] However preoccupied with sexual reproduction and morality, such a social order fails to hold white men accountable for sexual and other forms of violence against women of color, both historically and in the present day, and instead portrays the women as sexually aggressive or fearsome.

Popular and folkloric dance reinforce explicitly sexualized and heteronormative roles that reproduce notions of gender rooted in the colonial era.[18] Common dances such as salsa and rumba-guaguancó confine women to a role based on that of a romantic partner, with most partner dances considered “erotic” in their basic mood or orientation. While Afro-Cuban religious folklore, such as the dances of the Orishas and Congo folklore, arguably provide a wider repertoire of possible femininities, the commonly performed roles of Oshun and Yemayá are within the purview of normative female roles.[19] In rumba-guaguancó (as in the dances of the Orishas) performance roles use fluid movement based on the “Cuban technique,” consisting of an undulating spine, flexible torso, and bent knees.[20] While this technique succeeds in differentiating modern Cuban and folkloric dance from classical ballet in a variety of ways, it also amplifies the display of women’s hips and suppleness of body in the performance of rumba. In popular styles such as salsa, women also use sinuous body styling, emphasizing waist and hip movement, accompanying it with delicate wrist movements, small steps, and a narrow stance. Furthermore, women often dance as partners to men; in salsa, using the loose embrace of social dance position, women follow a man’s lead. In guaguancó, although the man and woman dance independently of one another, the woman responds to a male partner’s gestures and movements. While these two genres represent racial imaginaries of women’s roles, they also reinforce a singular notion of gender that casts women’s agency in terms of the expression of sexual or romantic desirability. By contrast, men’s roles embody an emotional attitude of daring and power and enact independence and self-direction.[21] Men’s dance movements emphasize their arms and legs; body styling tends to be more segmented as they demonstrate physical strength and independence. One dancer explained the difference between men’s and women’s body movement as related to “different goals” in the social world.[22] Although gender norms change, such dance roles tend to reinforce heteronormative ideals in the kinetic patterns of folkloric and popular dance.

Critical scholarship on Afro-Cuban folklore has examined a range of issues related to race, ethnicity, and national culture critiquing histories of appropriation, criminalization, and ambivalence towards Afro-Cuban religious communities.[23] While some scholars have noted the gendered dynamics that permeate the social fields of folkloric performance and Afro-Cuban religion, gender and sexuality have not been central to musical ethnography of folklore in Cuba. As such, these issues currently comprise an expanding area of ethnomusicological research.[24] In literary and cultural studies, however, scholars have given attention to intersections of gender, sex, and race in the construction and representation of folklore and national culture in Cuba.[25] Insights from Paul Gilroy and Jossianna Arroyo about the gendering of racial discourses and national culture prompts an examination of how performers negotiate the intersections and slippages between lived experience of identity and constructions of folklore as national culture.[26]

For individual performers, dance-music can operate as a “technology of self” and can have political significance as performers use the terms of performance to define self-identity.[27] That is to say, musicians and dancers can use folkloric shows to pursue identity agendas and contest official identity discourses through the reflexive and communicative dimensions of performance.[28] Particularly powerful in expressing these subjective meanings are the ways individuals alter the norms of a style, both intentionally and unintentionally. Alterations violate the expectations that organize a listener’s sense of self (“listeners” here includes both performers and audiences) and in so doing produce emotional and other affective responses.[29] Building on the idea that music communicates through affect and not propositional statements, this basic conception of musical meaning can be applied to performance as a process of embodied discourse.[30]

Like verbal discourse, performance can be understood to organize a set of relationships and interactions around three subject positions. These positions may be mapped from verbal discourse to dance-music event. The three positions include a speaker or protagonist, an interlocutor or interactive dyad, and a community of interpreters in which the protagonist establishes themselves as a subject.[31]

| Discourse | Kinetic Conversation | |

| The speaker | → | the protagonist |

| The interlocutor | → | the interactive dyad |

| The people who read/write... | → | the community of interpreters |

Individual experience, dyadic interaction, and the coordination of the collective all contribute to the significance of a dance-music event producing layers of constitutive meaning. That is to say, the sense of self and identity that emerge in performance arises from feelings of self, interactions with other selves among a community of interpreters, and the verbal interpretations given to performance. Individuals can use a type of dance-music performance as a discursive system in which alterations reflect identity negotiations, which I have described elsewhere as kinetic conversation.[32] This approach treats music and dance as integrated elements of a discursive system that coordinates performer interactions and that, by their interactions, allows participants to enter a world of shared significance.[33] It combines musical sound, language, movement, and emotion, accounting for music and dance as cross-modal communication.[34] This approach underscores the importance of understanding how Cardoso’s performance fits together with the music and song to create a coherent and powerfully moving dance-music event. Her identity negotiation plays on a criticism of essentialized gender identities, but it relies on the mutual collaboration of her fellow performers and succeeds by reinforcing a dialect of style shared by a community musicians and dancers within the world of folkloric performance. In taking up and altering the terms of national culture to express folklore as a specifically Afro-Cuban tradition, I argue that the musicians and dancers engage in a critical conversation on national culture through the process of performance. On a personal level, Cardoso’s gender transgressive dancing gives her access to a domain of professional performance through which she asserts a different vision of legitimacy and belonging.[35]

Of the three sub-styles of rumba recognized in Cuba, columbia contrasts with the choreographic depictions of flirtatious and combative interactions of a heterosexual couple that characterize the rumba styles of guaguancó and yambú. In columbia, the solo male dancer, referred to as the columbiano, performs masculine honor in a solo dance, embodying values such as elegance and bravery, among others. The choreography, although improvised, includes a basic set of steps and gestures. The dance often follows a narrative structure that climaxes in a confrontation with an unseen challenger. In this way, performances enact the mythology of a heroic individual and locate the masculine subject at the center of a network of homosocial relationships forged in competition and camaraderie. Dancers and musicians earn “real life” reputation and honor by performing columbia. As Miguel from Oba Ilú states, “Columbia is a brotherhood,”[36] and Ivan, who trained with the CFNC, explains that “Columbia is something serious,” because it is “something between men,” contrasting it with the partner dance guaguancó, which is “just for fun and entertainment.”[37]

While the dance expresses the personal experience of a gendered sense of self, it also conveys that value given to rumba in socialist Cuba as an exemplar of working-class artistry and ultimately as an expression of Cubanness.[38] Francisco from Oba Ilú explains:

Columbia was born from the people . . . it is a popular Cuban dance and because of that it cries. The singer sings “Oh God! Oh God!” because he had suffered. He was from people on the margins. . . .

It is an expression of respect, of feeling. [The point is] to express through this dance that you are a man, a gentleman of respect. What makes the columbiano a man of respect. . . [is expressing that] feeling towards life, towards being Cuban.[39]

Thus, the figure of the columbiano embodies not only depth of feeling and suffering born of hard work and material deprivation, but also maps the value of patriotism onto the social processes that produce men’s honor. It underscores the character of the nation and definitions of belonging as organized around men’s homosocial relationships. In choosing columbia to establish her identity as a professional dancer and legitimate interpreter of rumba, Cardoso appropriates a powerful trope of masculinity and Cubanness to redefine belonging around her own experience of identity.

Sitting in the kitchen of her sparsely furnished and freshly tiled apartment in the neighborhood of Jesús María, I ask Cardoso what she seeks to express through her dancing. First, she says, “strength,” and pauses. Then, she goes on to state with the confidence of a skilled debater, “In reality, I dance in defiance of men. I enjoy doing it because I want to put women in the place they deserve.”[40] While Cardoso expresses her own intent with clarity, music and dance do not communicate in the same way language does—that is to say, using propositional statements. In one sense, her explanation obscures embodied aspects of musical meaning. One of the more expressive and controversial aspects of Cardoso’s dancing is her powerful body styling. A concept borrowed from salsa dancers, body styling refers to the quality of body movement, rather than to the steps or gestures she performs. Also described as “dance accent” or “dance dialect,” body styling speaks tacitly to the social positioning of a dancer or the lived experience of identity. [41] In Cardoso’s case, her style of movement distinguishes her from professionally trained dancers. This creates an easy target for criticism in a field that has been dominated and regulated by official institutions of culture. For many observers familiar with the standard style, this places her dancing on a continuum from socially inappropriate to aesthetically invalid. One dancer who trained with the CFNC observes that her “movements look unnatural on a woman’s body” indicating how Cardoso’s dancing violates the aesthetics of gender in folkloric and popular dance.[42] Folkloric dance in Cuba tends to stylize movement in ways that naturalize social roles.[43] With such expectations, the power of Cardoso’s movement and disregard for the choreographic tropes of feminine/female bodies (common usage tended to collapse gender and sex) creates a kind of dissonance. Another professional dancer responds to her performance by saying, “It is possible to dance columbia without ceasing to be a woman,” indicating the extent to which her movements defy expectations of how women’s bodies move.[44]

Not everyone, however, rejects Cardoso’s performance; some even laud it. Amauris, the man who composed and sang the verses in that evening’s columbia, explains the merits of her dancing, saying that, “She captures the true feeling of the music.” He continues, “Which some of the men fail to do because they dance too beautifully.”[45] Touching on the visible division between artistic renditions of folklore and folklore as a living tradition, the singer’s comments highlight the tension between conservatory technique and those that develop in quotidian spaces. Although Cardoso’s style appears rougher and technically unpolished, he defends her dancing as emotionally and musically expressive. Furthermore, focusing on how dance movement corresponds closely with the music, the singer invokes a characteristic of Afro-Cuban religious dance-music performances, which commonly map between words, rhythms, and dance movement, as in the dances of the Orishas. In addition to the differences between artistic renditions and living traditions, performers express awareness that the dances have been changed in the process of staging them as folklore, including columbia itself.[46] So, references to an alternative style implicitly invoke a tradition that pre-dates the use of columbia as national culture. Pedro, an older rumbero (performer of rumba) comments on Cardoso’s dancing by saying, “In the old days, women danced columbia. . .” but then abruptly turns away from this line of reasoning.[47] He goes on, instead, to criticize the performance from a heteronormative and, frankly, homophobic perspective saying, “. . .but not in public. Precisely because of the movements, which are strong, you can understand that a woman shouldn’t do it. They will think she is a lesbian.”[48] His comments underscore how sex and gender are collapsed in the context of folkloric performance and how conformity to heterosexist norms becomes a dividing line in the expression of national culture. By contrast, some authors point out that Afro-Cuban and Afro-Caribbean religions make space for homosexual and queer identities and performances.[49]

Although the two men disagree about Cardoso’s right to dance in the show, they both invoke an alternate style of columbia that implicitly situates rumba in a broadly Afro-Cuban expressive tradition. This contrasts the discourse of folklore as national culture which interprets rumba as a creole or Cuban genre in contrast to the Africanness of Afro-Cuban religions. While this interpretative stance is not absolute, I argue that its distinction, which is subtle and situational, is significant because it shows how some musicians and dancers use performance to distinguish themselves within the broader world of folklore. Negotiating identities of gender and sex, Cardoso allies herself with a community of performers who reframe national folklore as a particularly Afro-Cuban expressive tradition that accommodates her non-standard performance and locates her within the world of professional folkloric performance.[50]

Born in Havana in 1974, Isnavi Cardoso Díaz grew up in the suburban neighborhood of Santo Suarez, where she trained as an athlete from a young age. Talented in track and field, Cardoso competed at many levels and won prizes at national meets. Later, she was selected to play volleyball at a time when the Cuban women’s team dominated Olympic competition. Cardoso attended high school for sports at the Emilio Núñez Polytechnic Institute where she trained as the principal outside hitter. Citing personal problems, however, she explained that she did not finish there, but instead completed her degree in the unrelated field of railroad signal technology. Although she maintains an interest in women’s volleyball and other sports, she never returned to athletic training.

After high school, wanting neither a career in the railroad industry nor the confinement of domestic life, Cardoso began taking dance classes at the local cultural center. Despite her lack of experience, she excelled in the amateur classes and was quickly invited to participate in various groups. Cardoso joined a newly forming dance ensemble, where the director, a graduate in commercial productions, recognized her ability for folkloric dance. She recounted:

I joined a group that was just forming, Grupo Guasamba. That is where I really began to learn folkloric dance. I was happy to join because I really didn’t know very much. . . I danced a lot of Congo [folklore]. [The director] said that I was skilled at it. Since I came from sports, I was strong.[51]

Congo folklore entails powerful, frenetic movements, at times imitating spirit possession. Not long after she began dancing professionally, Cardoso won recognition as a soloist in Congo folklore with prizes from the Wemilere festival in Guanabacoa and the University of Havana. Together with the role of the orisha Oyá, which Cardoso performed regularly with the group Oba Ilú, these dances make up her preferred repertoire.[52]

Figure 2: Isnavi Cardoso Díaz dancing in the role of Oyá. She is holding horsetail fly whisks, which are one of the oricha’s attributes. August 13, 2008 show by Oba Ilú at the Yoruba Cultural Association of Cuba.

Figure 2: Isnavi Cardoso Díaz dancing in the role of Oyá. She is holding horsetail fly whisks, which are one of the oricha’s attributes. August 13, 2008 show by Oba Ilú at the Yoruba Cultural Association of Cuba.Evident across the genres she performs, physical power is a hallmark of Cardoso’s style. Not just a holdover from her athletic training, physically powerful movement is something Cardoso finds pleasurable about dancing. She made a point of saying that “I dance this way because I enjoy it.”[53] Far from a trivial preference, emotional responses can reflect evaluative attitudes.[54] It may be that for Cardoso, the so-called strong dances create a felt sense of self and belonging. In short, she feels at home in a physically powerful style of movement. Cardoso’s training in sports gave her not only the ability to endure the rigorous technical workouts of professional dance companies but also a way of being-in-the-world in which physical strength is part of her sense of self-identity despite the social norms of gender.[55]

Her talent and strength notwithstanding, Cardoso faced stiff competition in a world of performance where professional status was defined almost exclusively by conservatory training. The planilla (government payroll system) which began in 1968, managed performing ensembles and typically hired graduates of the national art schools.[56] An effect of the planilla system was to discourage professionalization of amateur performers.[57] During the nineties, however, the music industry underwent reform; the government cultivated a tourism sector that relied heavily on cultural performance including folkloric dance and rumba. Reforms also included the dismantling of the centralized bureaucracy responsible for artist management, which was split up into smaller agencies. Around 1994, the government licensed new performance venues and several ensembles that specialized in playing rumba. These changes seem to have created opportunities for amateur dancers and musicians to join the ranks of folkloric performers. Soon, Cardoso joined one of the new rumba groups called Agüiri Yo. Eventually an agency was formed to represent independent artists (La Agencia D´Arte, a division of ArtEx S.A.) and Cardoso was one of its early members. She was thus among a generation who gained professional status at least partially outside of government institutions.

Despite decentralization of the music industry, a hierarchy related to training and individual reputation persists among folkloric dancers. Performers refer to those who come from conservatory backgrounds as being de la escuela or “from school” and those who are self-taught, come from amateur classes, or have informal training being de la calle or “from the street.” Observable differences in style and other knowledge anchor these identities in different social spaces and speak to lines of belonging and exclusion. Like other dancers, Cardoso expresses her awareness of these distinctions. She describes her trepidation in joining Yoruba Andabo, one of the long-established, top-line rumba groups in Havana:

. . . [one of the members of the group] told me to come to [the audition]. I went but was afraid because I always thought of Yoruba Andabo as one of the best rumba groups and that I couldn’t, well, that my way of dancing would not appeal to them, because I’m from the street [de la calle]. I saw them as the best.[58]

Although she had been rehearsing and working in professional companies for several years by this point, she expressed anxiety about not belonging due to her lack of professional training. She continued to explain how this group became her “school of rumba” and that she began to shape her career as a rumbera, or performer of rumba.[59]

The distinctions between amateurs who came “from the street” as opposed to professionally trained performers “from the schools” took on new moral connotations during the nineties and aughts. The amateur movement, which gave Cardoso her start, had been part of the government’s cultural policy following the revolution, supporting the goals of development and sovereignty by involving the general population in artistic production across a variety of media.[60] During the nineties, as the nation underwent crisis and transformation, public spaces became highly charged and morally ambiguous, as new economic activity developed under conditions of a dual economy.[61] Dance music venues were closely associated with the dual economy and distinctions between professional and amateur performers became intertwined with the racializing discourse surrounding a kind of sex work and tourist hustling called jineterismo.[62] Perna notes that such venues became known as “zones of social contamination” due to the mixture of Cuban patrons and foreign visitors.[63] Defined in official discourse as a kind of sex work pursued by women of color seeking foreign partners for access to luxury goods and entertainment, the official discourse on jineterismo mobilizes racialized notions of gender that go back to the colonial era.[64] Conceptions of white sexual purity and black sexual dishonor frame women of color as “dangerous others” and imperil their status as citizens.[65] In this context, public space and dance-music venues, in particular, created moral hazard for women of color alongside the rewards of pursuing a career in the performing arts.

Around 2001, Cardoso began dancing columbia asserting her claim to honor and professional status. Although it was difficult to get a start and Cardoso recounted how the musicians would stop the music when she got up to take a turn, she persisted and eventually incorporated her columbia into a professional folkloric show. Working with the renowned folklorist Gregorio Hernández, Cardoso helped re-establish the group Oba Ilú in 2005 and worked in the ensemble until 2010. Under Hernández’s direction, the group developed folkloric shows that engaged the shifting discourses of national culture until his death in 2012.[66] Cardoso continues to work professionally in folklore while expanding her professional reach, occasionally appearing with the hip-hop group Obsesión.[67] She nevertheless remains part of the Havana rumba scene and currently works with the theater troupe Cimarrón. To illustrate how her performance of columbia engages other performers, alters the standard style, and expresses an interpretative stance that distinguishes her and other performers within the broader world of folkloric performance, the next section presents a description of rumba-columbia followed by a close reading of one of Cardoso’s performances with Oba Ilú.

Columbia developed during the nineteenth century in rural areas of Matanzas province and small towns surrounding the sugar mills. Musicologists trace its origins to Congo/Bantu musical culture.[68] This ethnic categorization recognizes connections between Cuban musical traditions and African language and culture areas. It also locates columbia within in a system of meanings and values specific to the field of Afro-Cuban studies founded by Ortiz that focuses on musical features and linguistic elements in the construction of a homogenous Cuban ethnicity.[69] After the revolution, the government upheld rumba as an exemplar of working-class artistry and cultivated it as a secular artform that expressed a similar vision of a homogenous national culture.[70] Rumba flourished as an artistic form during the height of the socialist era as the state’s drive for modernization and development framed Afro-Cuban religious expressions as relics of a primitive past that would inevitably fade away. As folkloric shows emerged as a powerful new performance genre, columbia became an important sphere within the world of folklore for relationships and identity in the everyday life of its performers. It operated by some accounts as a gateway to reputation and renown in the Havana world of folkloric performance.

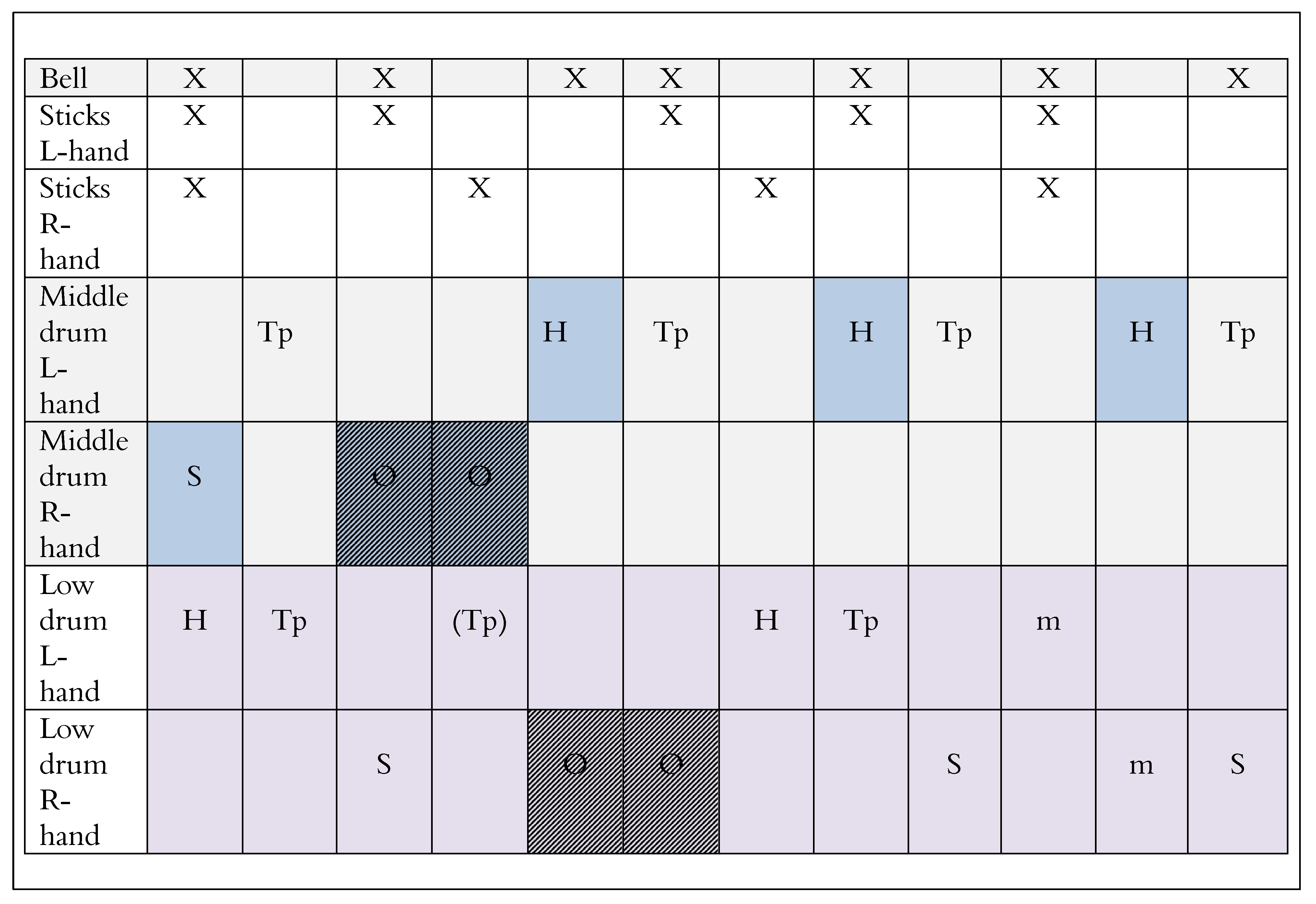

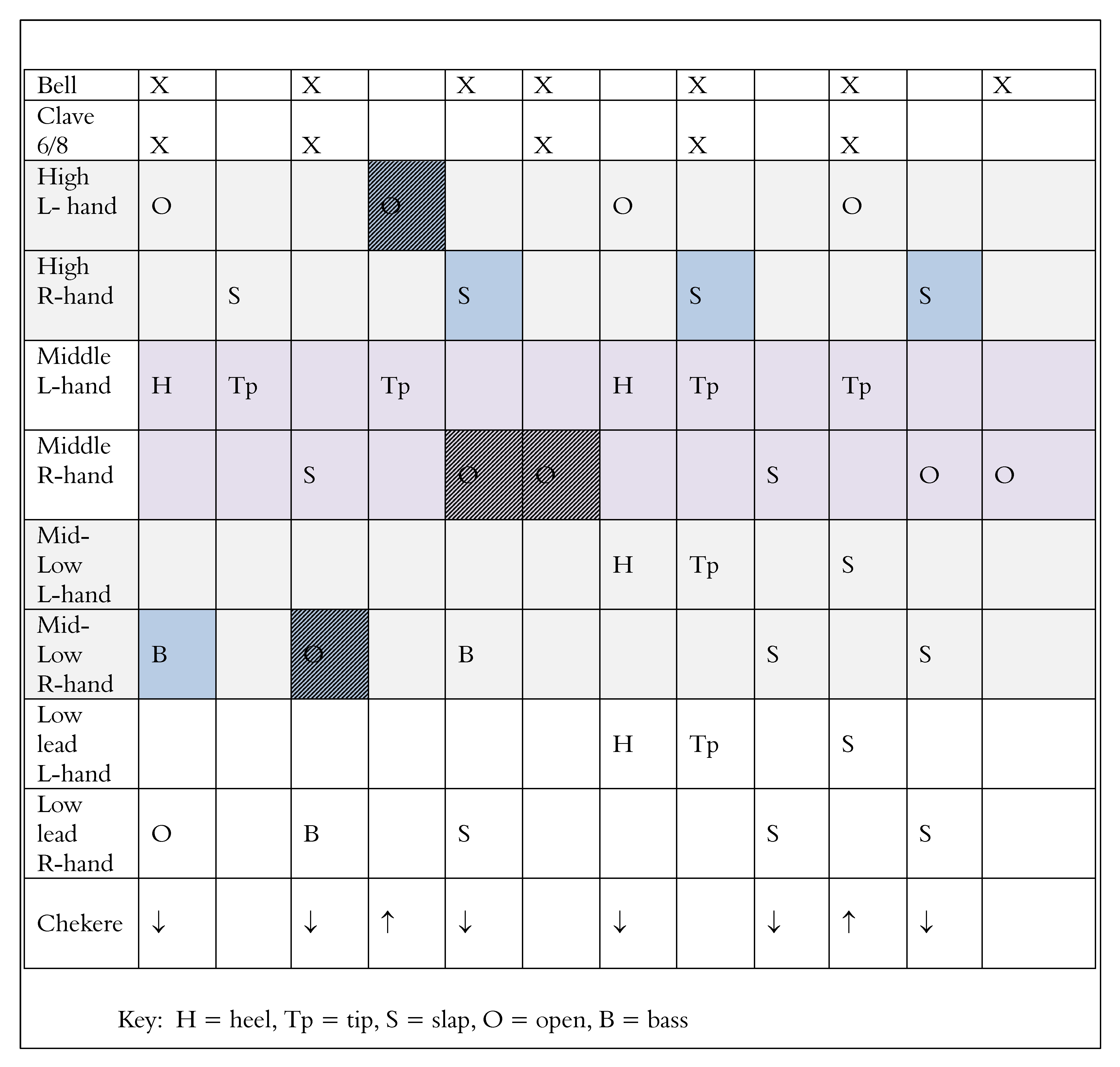

Folkloric ensembles perform columbia (and other styles of music) with a five-part percussion ensemble, a lead singer, a chorus, and dancers.[71] The percussion accompaniment consists of three conga drums (high-, medium-, low-pitched), wooden claves or a metal bell, and a pair of sticks used on a woodblock or piece of bamboo. A time-line pattern called clave, played with wooden claves or on a metal bell, coordinates all of the other parts. Oba Ilú used a metal bell to distinguish columbia as a rural style.

Figure 3: Time-line pattern (clave) and stick part (guagua). The time-line pattern consists of two phrases of six beats each. It is often notated in 12/8. Dancers tend to follow the guagua because it is often easier to hear, and it clearly outlines the downbeats.

Figure 3: Time-line pattern (clave) and stick part (guagua). The time-line pattern consists of two phrases of six beats each. It is often notated in 12/8. Dancers tend to follow the guagua because it is often easier to hear, and it clearly outlines the downbeats.The low and middle drum parts are interlocking rhythms, each with a two-part phrase structure like that of the time-line pattern. The drummers may vary and or ornament the basic parts. The part assigned to the high-pitched drum or quinto is improvised. During the verses the quintero (quinto player) interjects rhythmic phrases between the sung lines of text and during the call and response, the quintero sounds the dancer’s movements with drum strokes.

Figure 4: Basic drum parts of columbia. Each part is composed of two phrases of six beats each, following the structure of the time-line pattern. This chart highlights the interlocking open tones. I refer to this as the “classic” or folkloric style, to differentiate it from the contemporary guarapachangueo style of playing which tends to be more densely polyrhythmic.

Figure 4: Basic drum parts of columbia. Each part is composed of two phrases of six beats each, following the structure of the time-line pattern. This chart highlights the interlocking open tones. I refer to this as the “classic” or folkloric style, to differentiate it from the contemporary guarapachangueo style of playing which tends to be more densely polyrhythmic.The music unfolds in a flexible, two-part song form, led by the solo singer. The first section begins with a brief vocal introduction, referred to as the diana (as in guaguancó) or the llanto, meaning cry or lament. The vocal introduction typically includes the phrase, “Oh! God!” (Ay! Dios!) and uses downward melodic phrases. The mood is intense but not necessarily sad. Like other styles of rumba, the introduction includes characteristic vocables.

| [0:09] bell begins, percussion instruments follow |

| Soloist: [0:15] Orororo [0:22] Awe mama aaa [0:31] Ay dios, ay dios, ay, dios |

Following the introduction, the solo verses may be improvised, pre-composed, or a combination of the two. Verses typically describe lived experiences, contain bragging and boasting, and may mock or challenge a rival singer. The second section of the song consists of a call and response between the solo singer and a chorus. Dancing occurs only during the call and response. In this section, the soloist leads a chorus of singers through a selection of short couplets or phrases drawn from a repertoire of choruses or coros. The soloist uses aural cues to indicate when a change of chorus will occur. This section includes both sustained repetition and subtle changes in timing and text. The purpose of the call and response is to animate the crowd and inspire the dancers, raising the energy of the entire event.

The characteristic movements of the dance emphasize the musculature of men’s working bodies with shoulder shimmies, jumps, kicks, and slashing arm movements. Body styling tends to be segmented and angular; the quality of movement is sharp and strong. The dancing uses rapid footwork and may include spectacular feats and acts of daring, including acrobatic maneuvers and sometimes stunts with knives and bottles. Facial expressions match the intense concentration and deep emotions that can border on fury and abandon. Like the music, the dancing is intense, competitive, and expressive of deep feelings. The CFNC developed a standard set of steps that can be observed in their contemporary performances and in the ways knowledgeable performers describe and teach the dance. Dancers noted that columbia allows the dancer freedom to create their own choreography and display their personal character.

In the following analysis, I consider how the dance-music event produces subjective significance in terms of the three positions outlined by the model of discourse mentioned above. First, I examine how the dance-music event organizes a first-person experience, with emphasis on the role of movement in a felt sense of self. Next, I consider how the standard style of performance defines the social space or world of folkloric performance, as a landscape of overlapping and intersecting communities of interpreters. Finally, I examine how Cardoso’s alterations of the standard style catalyze interactions with particular members of the group. In these dyadic interactions, other performers respond mutually to her performance giving shape to the broader coherence of the event. These interactions locate Cardoso among a community of musicians and lend legitimacy to her as a professional dancer and interpreter of rumba, but it also allows the individual performers to enter a world of shared significance that varies in some ways from standard interpretations.

The performance discussed below was part of a folkloric show by the group Oba Ilú that took place on August 13, 2009, at the Yoruba Cultural Association of Cuba, where the group had a regular gig for several years. The show followed a standard format used by many contemporary ensembles, presenting a program in two halves, in which the first half consists of stylized dances of Afro-Cuban religions, and the second half consists of rumba. Typical of such shows, there was only one columbia on the program. Cardoso performs last in a line-up of three dancers. Both the figure and the description below include timestamps corresponding to the video.

Figure 6a: Video: Oba Ilú at the Yoruba Cultural Association of Cuba, August 13, 2009. [72]

| [0:09] The performance begins with the bell pattern. |

| [0:15] Diana or introduction. |

| [0:47] Verse 1 Mixture of Spanish and vocabulary from Palo. |

| [1:41] Verse 2 Mixture of Spanish and Yoruba praising Oyá. |

| [2:55] Verse 3 All Yoruba verses praising Oyá. |

| [3:41] Dancer 1 |

| [5:49] Dancer 2 |

| [6:42] Cardoso steps forward during another dancer’s solo requesting a turn. |

| [7:04] As Cardoso begins dancing, Hernández changes the guide song to one that praises Oyá, a female ancestor deity. |

| [8:39] She moves into position for the closing phrase, but the other dancers cue the phrase before she can coordinate with them. |

| [8:47] The three dancers bow to an enthusiastic crowd. |

| [8:53] Cardoso then turns to a woman who had approached from the audience and ushers her graciously onto the stage and signals the band to continue playing, which they do. |

| [9:54] The woman finishes and exits, and the band finishes the song. |

Stepping forward during another dancer’s solo [6:42], Cardoso breaks etiquette and begins her performance with a dramatic gesture that seemingly disrupts the expected flow of the event, but in reality, was planned. She dances slowly at first, demonstrating intense concentration [7:04]. Then suddenly, with a shoulder shake characteristic of columbia, she jumps down and finally seems to begin in earnest [7:16]. After rising up, her arms jab at the air and her legs pump furiously. Forceful and angular, the movements of her dancing express physical power and emotional abandon uncharacteristic women’s roles, social or choreographic [7:28]. Her dancing ebbs and flows spontaneously, building erratically to a climactic moment when Cardoso somersaults down the center of the stage and finishes her approximately two-minute long solo with an upward leap [8:27]. Dancing for a moment in place, she then bows gallantly. Gesturing to the two men who danced earlier, she moves into position for the unison closing phrase [8:33, 8:39]. Behind her, the two men glance at one another and cue the phrase just before Cardoso can synchronize her movements with theirs [8:41]. Intentionally or unintentionally, they effectively shut her out.[73] She recovers but remains out of sync with them. The three dancers bow to an enthusiastic crowd [8:47]. Cardoso then turns to a woman who had approached from the audience moments before seeking a turn; she ushers her graciously onto the stage and signals the band to continue playing [8:53]. After the woman, who is a professionally trained dancer, finishes and exits, the band ends the song [9:54]. Although rejected by some, Cardoso’s dancing succeeds in opening up space for other performers, both from fellow band members and from the dancer who volunteers from the audience. The event reveals the plurality of style and lived experience that exists within national culture. For her part, Cardoso demonstrates her status as a professional dancer and aligns herself with a community of musicians linked with Afro-Cuban musical repertories.

A Felt Sense of Self

Situating herself at the center of the performance and displacing the male subject of the dance, Cardoso alters the standard style with her gender-transgressive dancing. Moving in a style reserved for men, she challenges expectations about who dances columbia and what it means. While Cardoso’s movements may refer symbolically to qualities such as masculinity, honor, or strength, her dancing creates meaning that takes shape as a felt sense of self. Although the prime site of this is her own first-person experience, it can be understood to extend to or resonate through the set of relationships that emerge in the performance event. Since expectations about dance-music events can be understood as embodied dispositions, they shape how individuals interpret also how they experience a sense of self through the event.[74] Violating these expectations, Cardoso destabilizes the ground of interpretation, opening up space for new interpretations of columbia. While doing this she exposes the slippage between ideological constructions and the lived experience of identity.

Cardoso’s powerful body styling plays a key role in this process. The strong connection between movement and subjectivity proves important for our understanding of both music and human consciousness.[75] Here Cardoso’s dancing allows her to experience herself at the center of the relationships of the performing event, the significance of columbia reshaped to her experience and identity at the level of a felt sense of self. As Damasio explains the emergence of consciousness or subjectivity in stages, the first of these stages comprises the “primordial feelings” of the brain monitoring the body and its sense precepts, including proprioception.[76] From the perspective of embodiment, Cardoso’s powerful body styling does not, in its primary significance, point to a concept or express an idea, but rather, drawing on her training as an athlete, allows her to experience a familiar sense of self, in terms of the culturally valuable medium of columbia.

Cardoso also makes clear that that her dancing is not an expression of her sexuality or gender identity per se (these terns tended to overlap in common usage), but rather, explains that it is an expression of independence and equality with men. While her style of movement may appear “masculine” to some outside observers, for Cardoso the performance does not contradict her identity as a heterosexual woman. Rather, it enacts an experience of self that is fundamental to her personal life history. She describes a sense of continuity between her formative training in sports and the way she is recognized as a dancer for her powerful body styling. In this way, she draws on her formative training as an athlete to cultivate a personal dance style marked by physically powerful movement. By expressing awareness of this continuity, Cardoso indicates that there is a common thread in how this sense of physically powerful embodiment catalyzes a familiarity sense of self.[77] This familiar sense of self may account (at least in part) for the positive emotions Cardoso experiences from this style of movement, saying that “I dance this way because I enjoy it.”

Observers, however, understand her performance quite differently. Their comments focus on how her powerful style of movement contrasts women’s roles in both popular and folkloric dance. Cuban scholar Elena Díaz summarizes la sexualidad femenina (female sexuality) as:

While Díaz’s description of female sexuality as gender identity does not expressly include kinetic expressions of gender, it outlines many principles that can be observed in women’s dance roles. Expectations of women as lesser than men is illustrated by roles that limits women’s ability to initiate movement, as they often respond to men, limits the breadth of her movement as the woman’s stance is narrow, emphasizes romantic roles, sexualized attractiveness, and requires body styling that is soft and supple, even if dancers are strong from the rigors of training. Furthermore, in comparison to this list of characteristics, Cardoso situates herself as independent, expresses interest in her public persona and professional career, and demands equality in the professional realm. Also, as a former athlete, she is implicitly knowledgeable of her body. Finally, her dancing demonstrates disregard for demure feminine modesty.

By joining the performance of columbia, she pursues and experiences a felt sense of self based in a powerful style of movement, and which reflects for her the values of professionalism and equality. It demonstrates her agenda of being recognized as a professional dancer and legitimate interpreter of rumba. Cardoso’s sense of self is built, in part, on the gestures and movements of the dance, and the verbal meaning attributed to them through Cardoso’s reinterpretation of the tradition. In joining the performance, not only does she resolve paradoxes of her own identity by experiencing a felt sense of self that aligns with the values of the dance, she also alters the set of relationships built around the solo dancer. Here the dancer, as protagonist of a discursive event, establishes herself as the subject of the performance and engages the audience and other performers (addressed below).

The World of Folkloric Performance and a Standard Style

Beyond the disruptive entrance and gender-transgressive quality of her body styling, Cardoso’s performance demonstrates familiarity with the standard style used by professional dancers in Havana to perform columbia. She draws on a lexicon of steps developed by the CFNC and sequences her solo in accord with the standard practice, from slower and simpler to faster and more complex, including a climactic and daring movement typically taken as a mark of individuality, which in her case is a somersault. A comparison of video stills from Cardoso’s performance with those of a performance by members of the CFNC that same year shows the use of the same basic steps. Video, however, shows differences in technique between Cardoso and dancers from the CFNC. In another hallmark of the CFNC’s standardization of columbia, Cardoso participates in a unison closing phrase, although uncooperative colleagues complicate this part of her performance. Using or imitating, these elements of the standard style, Cardoso situates herself within the world of folkloric performance, by participating in a shared set of standards and expectations that define professional performance. She demonstrates her belonging through competence in these standards, even if some colleagues contest that belonging.

Cardoso’s imitation of the standard style illustrates how we can understand the world of folkloric performance as a discursive system which coordinates interaction among a variety of individuals. The body movement or styling associated with the techniques, steps, and procedures of the standard style defines a domain or landscape of social relationships. Within this domain, different communities coalesce around interpretative stances or different uses of the discursive system and body styling reflects social spaces and their histories of interaction. Initially blending the work of modern dance choreographers with the practical knowledge of “performer-informants” and scholarly interpretations, the CFNC developed and proliferated a way of teaching and performing Cuban national folklore.

Figure 7: Cardoso uses basic steps reflecting competence in the standard style. These screen shots show three steps from a larger variety of steps and gestures codified by the CFNC in its pedagogy and performance of columbia. A comparison of Cardoso (left) with dancers from CFNC (right) shows that she uses the same basic repertoire of steps and movements.

Figure 7: Cardoso uses basic steps reflecting competence in the standard style. These screen shots show three steps from a larger variety of steps and gestures codified by the CFNC in its pedagogy and performance of columbia. A comparison of Cardoso (left) with dancers from CFNC (right) shows that she uses the same basic repertoire of steps and movements. The ensemble cultivated an approach that rejected commercialized styles of performance and actively engaged ethnographic methods, linking their secular public style of performance with ritual and quotidian expressions of folklore. The ensemble hired musicians and dancers from traditional communities of practice, referred to as “performer-informants” and “carriers of culture,” to contribute vocal, musical, and choreographic repertoires. The company then shaped and adapted these repertories to theatrical presentation. A jury system, in which government representatives certify and rank performers for the planilla or government payroll system, regulates interpretative and technical parameters and contributes to reinforcing the standard style. In turn, that style represents and naturalizes national culture. The codification of steps, systematic rehearsal processes, and the jury system all contribute to consistency of technique and interpretation, despite modifications over the years. The resulting standard style coordinates interaction among individuals in different roles and social spaces. These include dance students from conservatories, musicians from religious communities, assessors, amateurs, audiences, academics, and others who participate in the discursive domain.[79]

Within the social landscape of public folkloric performance, interaction over time links individuals into overlapping and intersecting communities. As mutual performance interactions form social bonds, stylistic elements which organize mutual performance interactions reflect a shared interpretative stance, like those “from school” or “from the street” and between public performance and ritual uses of music and dance. These conditions include the institutional spaces of training, public spaces of performance, and bureaucratic processes that regulate them. As a result, style tends to reflect the social landscape of folkloric performance by expressing proximity or distance from those institutions. By altering the standard style, performers use the terms of folkloric performance to comment reflexively on that domain. Subtle variations reflect the understanding that the social landscape of folkloric performance is not monolithic.

In this case, the unison closing phrase demonstrates how dancers in the show use performance to differentiate themselves and express dissent regarding Cardoso’s participation. Her fellow dancers highlight the distance between Cardoso and the standard style by coordinating the timing of the closing phrase to cut her out. The two men wait on either side of the stage as Cardoso finishes but start moving before she is in position. The men cue the phrase quite literally behind her back and take off ahead of her. She follows but lags behind. Out of sync, Cardoso no longer appears to belong seamlessly to the performance or to the community of dancers known as columbianos.

Traveling step (image on left shows diagonal movement, image on right shows horizontal movement) the feet are brought together on accented beat.

Traveling step (image on left shows diagonal movement, image on right shows horizontal movement) the feet are brought together on accented beat.  Miliano calls this step “kick and a comma.”[80] Photos illustrate the idea that dancers from the CFNC perform standardized set of steps with consistency of technique.

Miliano calls this step “kick and a comma.”[80] Photos illustrate the idea that dancers from the CFNC perform standardized set of steps with consistency of technique. Figure 8: Columbia by the CFNC, 2011. These screen shots illustrate consistency of technique and standard style that characterizes CFNC performances of columbia. Each pair of images illustrate the same step by two different dancers. Each dancer composes his own choreography, but the basic steps and gestures are similar and consistency between dancers is apparent.

Communities of Interpreters and a Dialect of Style

Despite the dancers who reject Cardoso’s presence, her dancing does fit into this performance in a way that is crucial for its overall effect and especially its expression of an alternate interpretative stance. Correspondences between Cardoso’s dancing and choices made by some of the musicians suggest that the performance builds towards her intervention. Cardoso’s alterations of the standard style intensify the event in part by catalyzing mutual interactions with key members of the ensemble. Responding “in kind” to Cardoso’s presence, these performers contribute their own alterations. From song texts and rhythms to the etiquette of performance, members of the group draw on specialized knowledge of Afro-Cuban religious music evoking an earlier style columbia. These mutual interactions create a musically coherent context for Cardoso’s dancing and the identity that results. Over time such altered performances coalesce into a dialect of style by which performers distinguish and locate themselves as a community of interpreters within the world of folkloric performance. This community draws legitimacy from connections with Afro-Cuban religious traditions and in some instances can distinguish themselves from the secular folkloric style of public presentations. Within the professional world of folkloric performance, this community develops out of and manifests in the dyadic interactions of individual performers.[81] Through these mutual interactions, musicians and dancers enter a world of shared significance.

From subtle changes like using a hand signal to request a turn, to conversing with the solo drummer in an exchange of dance steps and drum strokes, Cardoso’s alterations invoke an earlier tradition and catalyze mutual interactions with key members of the ensemble.[82] When reviewing video of the performance, Cardoso points out that she “asks for the conversation with the quinto,” which, she emphasizes, “hardly anyone does anymore.”[83] The drummer responds by attending to her every movement, translating her steps, shoulder shimmies, kicks, and hand wringing into rhythms on the drum. His exchange with her expresses his implicit acceptance of her presence and affirms her belonging. Their interactions give him the opportunity to demonstrate his skill and knowledge of the classic style of columbia. Not only audible and integral to the texture of the music, their dyadic interactions, as in a moment of verbal conversation, allow them to enter a world of shared significance. Such interactions are mutually affirming even if structured by roles that compel a relationship of competition.

Among the mutual interactions that reinforce Cardoso’s presence in this performance, the ensemble’s two lead singers play key roles. They each respond to her dancing by making alterations to the standard style that comment on her presence. First, the group’s director, Gregorio Hernández, who passed away in January 2012, was a great rumbero and powerful figure in the world of folklore. Having been part of the founding generation of the CFNC, Hernández gained stature, first as a performer-informant and soloist and later as a teacher and assessor in the planilla system. He was eventually licensed to form and direct the ensemble Oba Ilú. Within the group, he cultivated a style of performance that reflected the older classic style and advocated for corrections to some of the dogmas of national culture.

Figure 9: Ángel the Quintero of Oba Ilú interacts with Cardoso in the traditional conversation between the quinto and the dancer. He follows Cardoso's dancing with his drumming. She is in the foreground. Oba Ilú, August 13, 2009.

Figure 9: Ángel the Quintero of Oba Ilú interacts with Cardoso in the traditional conversation between the quinto and the dancer. He follows Cardoso's dancing with his drumming. She is in the foreground. Oba Ilú, August 13, 2009.While Hernández does not sing lead on this song, he momentarily takes that role when Cardoso dances, in a musical expression of his support for her participation. Entering unobtrusively into the performance while the second dancer completes his turn, Hernández sings “Moilé, moilé!” maintaining the guide song chosen by the main soloist [5:57]. Shortly after he changes to another chorus typical of columbia, “E maluanda e!” but does so without a vocal call to announce the change [6:07]. Just as Cardoso begins dancing, he changes the chorus yet again. This time, however, Hernández uses a vocal call to underscore the change marking her entrance musically [7:04]. The chorus he chooses to accompany Cardoso’s dancing, “Bembe Chango Oyá!” celebrates the female orisha Oyá. Oyá is a role that Cardoso performs regularly with the group and had performed earlier that evening (see figure 1). In short, he ends a chorus typically used in columbia (E maluanda e) and replaces it with one from Yoruba liturgy to accompany Cardoso’s dancing. In terms of the way discourse traces a set of relationships, this interaction points back to Cardoso as the protagonist of the conversation. Here, Hernández invokes a parallel between the dancer and the deity, as in rituals involving spirit possession where music is used to call upon the ancestor deities or orishas who manifest through dance. By invoking ritual, Hernández shifts away from the standard style. Rituals invoke orishas through a series of parallel expressive modes, namely: music or rhythm, song text, and dance steps or movements. Hernández’s alteration of the standard style invokes a different interpretative stance that emphasizes columbia as part of a broadly conceived and living Afro-Cuban expressive tradition.

| Hernández: Guide: Como tata moilé! Chorus: Moilé, Moilé! |

| [5:50 Hernández takes the microphone, continues the same guide song] Hernández: Como tata moilé! Chorus: Moilé, Moilé! Etc. |

| [6:07 Hernández changes the guide song without a call to alert the chorus. He chooses another chorus typical of columbia.] Hernández: E maluanda e! Chorus: Maluanda! |

| [6:44 Cardoso beings moving forward] [6:50 Cardoso uses hand signal to request a turn] |

| Hernández: E maluanda e! Chorus: Maluanda! Etc. |

| [7:04 Cardoso begins dancing, as previous dancer exits. Hernández changes the chorus using a call “Eee!” underscoring the change and her entrance. His singing and her dancing are closely coordinated.] |

| Hernández: Eee! Bembe Chango Oya! Chango Oya Chorus: Bembe Chango Oya Etc. |

While not unheard of in rumba, Hernández’s use of a Yoruba religious song contravenes two features of the standard style of columbia. First, rumba as national culture is considered secular and its lyrics typically treat secular themes.[84] Second, the school of research established by Ortiz identifies rumba in general and columbia in particular with Congo/Bantu musical culture and by custom would demand the use of language and texts that reflect that connection. The choruses used in columbia draw on a Congo lexicon, exemplified by words such as “moilé” and “maluanda” used in the earlier choruses. By selecting a song from a Yoruba repertoire, the singer deviates from the standard interpretation and invokes different aesthetic criteria through his choice of the guide song. In one sense, he uses his choice of the chorus (Bembe Chango Oyá) to comment on the event at hand underscoring Cardoso’s presence. In another sense, he flouts the interpretative parameters of folklore as national culture, which takes rumba as strictly secular and invokes what I am calling an aesthetic of correspondences that is characteristic of Afro-Cuban religious contexts.

In religious rituals, such as those of regla de ocha and the abakuá brotherhood, the aesthetic force and efficaciousness of the music derives in part from correspondences between sung text, percussion accompaniment, and dance movement. While Hernández’s invocation of Oyá likely expresses support for Cardoso’s dancing, which she acknowledges was important, it also gives clues to the larger performance. Hernández selects the song from the repertoire of bembé, a rural expression of Yoruba religion associated with Matanzas and the eastern provinces. Interpreting the performance as a variety of bembé suggests a series of correspondences that create a coherent musical context for Cardoso’s dancing. It creates a perspective from which to hear the performance as dissenting against the dogma of national culture by highlighting connections between rumba, a popular tradition, and Afro-Cuban religious music. In this way, Hernández and the other musicians put the knowledge of Afro-Cuban religious traditions at the center of their rendering of national culture. Of course, observers unaware of such references can enjoy the performance anyway as the song for Oyá fits into the musical structure of the call and response. As one dancer commented regarding the expression religious or esoteric knowledge in public performances, “some know, and some can only watch.”[85] Such expressions play on the existence of multiple communities within the landscape of folkloric performance and treat musical elements, not as mere aesthetic objects, but as modes of interaction with those communities.

As artistic director of Oba Ilú, Hernández made choices that shaped the group’s repertoire and style of performance. Here, the percussionists eschew the densely polyrhythmic texture of the contemporary style of rumba performance called guarapachangueo. Hernández expressed distaste for this style and discouraged its use in Oba Ilú’s performances. In fact, throughout the last decade of his life, Hernández’s sought to illuminate and emphasize the Afro-Cuban roots of Cuban popular music through lecture-demonstrations in institutional settings throughout Havana. Here, the percussionists follow his direction and play in a sparser style making columbia sound closer to its folkloric roots. More specifically, they highlight the musical similarities between columbia and bembé.[86]

When asked about this similarity, Fernández commented that columbia and bembé are “the same.”[87] A comparison of the rhythms of this version of columbia with those of a four-drum version of bembé illustrates this.[88] First, the low drum part in columbia exactly replicates the upper-middle drum part in this version of bembé.

Figure 11a: Columbia as Performed by Percussionists of Oba Ilú, 08/13/09. The parts include two variations. First, both drummers play the open strokes only in the first half of the phrase, marking the direction of the time-line or bell pattern. Second, the middle drum part is syncopated in the second half of the phrase, paralleling the off-beat accents of the high drum part in bembé. (compare with figure 11b.)

Figure 11a: Columbia as Performed by Percussionists of Oba Ilú, 08/13/09. The parts include two variations. First, both drummers play the open strokes only in the first half of the phrase, marking the direction of the time-line or bell pattern. Second, the middle drum part is syncopated in the second half of the phrase, paralleling the off-beat accents of the high drum part in bembé. (compare with figure 11b.)The middle drum part in this version of columbia also resembles bembé, but in a slightly more abstract manner. The part is a composite of the middle-low drum and the high drum parts, highlighted in blue in figure 11b. The first phrase of the columbia middle-drum part combines the bass and open strokes of the lower middle drum part with the open stroke of the high drum in bembé. In this performance, the drummer does not repeat the first phrase (as in the basic part) but fills out the second phrase with a rhythm similar to the high drum part of bembé, although he does this with a different type of stoke. I am not arguing that the percussionists use this particular version of bembé as a reference. Instead, I want to point out the audible relationships between the two types of music. In combination with textual references and a powerful female dancer as an image of Oyá, the parallel between columbia and bembé contributes to the coherence of the performance. Here Oba Ilú performs columbia, even if indirectly as bembé, invoking a religious event and the orisha it celebrates.

Figure 11b: Four-drum version of bembé with highlighting illustrates how low and middle drum parts of columbia can be extracted from bembé. Yellow highlighting indicates low drum part of columbia borrowed directly.

Figure 11b: Four-drum version of bembé with highlighting illustrates how low and middle drum parts of columbia can be extracted from bembé. Yellow highlighting indicates low drum part of columbia borrowed directly. Finally, Hernández’s reference to Oyá is not the first mention of the female warrior deity. In retrospect, Fernández, the main soloist on this song, invokes Oyá in the second and third verses of the song. Like the performances by Hernández and the percussionists, his performance contributes to the series of musical correspondences focused on the similarity of columbia and bembé. The younger singer begins the first section of the song with textual and melodic tropes typical of columbia, including solo introduction or llanto (see figure 4). In the first verse, he narrates a personal experience and brags about his personal power but frames it as experience with the Afro-Cuban religion of Palo. While bragging is typical of columbia, as mentioned above, the standard style uses secular themes in its lyrics. In this first verse, he maintains an association with the Congo/Bantú lexicon, which is used in Palo and from which columbia draws some vocabulary. Fernández, who works outside of Oba Ilú as a song leader and drummer for religious ceremonies, draws on repertoires of religious music invoking the aesthetic of correspondences of ritual music to intensify the performance at hand. His composition bridges the two contexts (ritual and public folkloric show) to create an aesthetically and emotionally powerful performance. In the second and third verses, he contributes specifically to the coherence of context built around Cardoso’s dancing.

The second verse shifts from a focus on the singer’s own religious experience with Palo to lines of poetry praising the orisha Oyá. Like Hernández’s choice of “Bembe Chango Oyá,” he uses texts from Yoruba religious songs to comment on Cardoso’s presence and interweaves religious songs into the secular columbia genre. First, he describes Oyá in Spanish as a beautiful woman and a “female warrior among male warriors,” then quotes a song praising Oyá in the linguistically mixed style of bembé. Then he sings: “Oyá, Oyá ambero, Oyá morere la oyansa, acama laroye, bembé nuco,” a song text borrowed from bembé. His composition anticipates her appearance and shows how performers reinforce one another’s alterations to collectively build an exciting and aesthetically coherent performance. Using texts from the Afro-Cuban Yoruba religion, he opens space for and affirms Cardoso’s presence by invoking Oyá. Like Hernández and Cardoso, the singer’s alterations of the standard style contribute to an interpretation of columbia as part of a broader and living Afro-Cuban expressive tradition.

In summary, the approach of embodied discourse traces how the dance-music event produces subjective significance across all three senses of the term embodiment. Cardoso’s body styling produces subjective significance through first-person experience, interactive dyads, and among a community of interpreters producing identity through layers of constitutive meaning. Her physically powerful style of movement creates a felt sense of self based on the continuity with her early training as an athlete. Her non-standard technique locates her at a distance to the CFNC’s standard style and decenters it by suggesting that a plurality of subjects exist within the space of national culture. Mutual dyadic interactions bear this out, as performers invoke a style that predates institutions of national culture to create a coherent and affective performance that links columbia to living religious repertoires of a broad and inclusive Afro-Cuban expressive tradition. The analysis suggests that the dance-music event produces constitutive meanings at individual, dyadic, and the collective levels, which can be parsed and explored through an analogy with verbal discourse. The model provides as a set of limiting factors regarding how performance communicates and produces shared knowledge, operating as a process of negotiation rather than one of decoding referential or symbolic meanings of musical events.

Cardoso’s performance of columbia can be understood as an expression of the lived experience of identity through which she negotiates her identity as a professional dancer and legitimate interpreter of rumba during a period of social and political transformations. Dancing in a physically powerful manner, Cardoso transgresses the heteronormatively gendered dance roles and finds acceptance among a community of musicians and dancers with whom she comes to share a dialect of the standard style of folkloric performance. Through alterations, which draw an association with bembé, performance interactions, and imitations of the standard style, the performers re-frame columbia as a uniquely Afro-Cuban music in contrast to narratives of folklore as an element of a homogenous national culture. Using the concepts of embodiment and discourse, I have shown how subtle alterations of the standard style reveal a communicative process through which performers comment reflexively on the domain of folklore and its subjective significance.

List of Interviews

- Anonymous. [Professional folkloric dancer.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. May 2011.

- Francisco. [Dancer employed with Oba Ilú.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. August 22 and August 25, 2011.

- Cardoso Díaz, Isnavi. [Dancer employed with Oba Ilú.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. February 4, 2011, and June 26, 2012.

- Jenny. [Dancer and singer employed with Oba Ilú.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. June 2011.

- Eva. [Dancer and director of Obini Batá.]. Interview, Havana, Cuba. August 2011.

- Fernández, Amauris. [Singer and Percussionist employed with Oba Ilú.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. March 21, 2011, and June 2012.

- Hernández Ríos, Gregorio. [Singer and artistic director of Oba Ilú.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. February 17, 2011.

- Pedro. [Retired dancer, percussionist.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. February 14, 2011, and June 2012.

- Miguel. [Dancer employed with Oba Ilú.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. April 3, April 5, and April 26, 2011.

- Iván. [Dancer trained with CFNC; employed with Ban Rará.] Interview, Havana, Cuba. August 25, 2009, and February 2011.

Bibliography

- Abreu Babi, Yanelys, and Anette Jiménez Marata. “Un análisis léxico-semántico del discurso sobre la mujer en el rap cubano.” In Afrocubanas: Historia, pensamiento y prácticas culturales, edited by Daisy Rubiera Castillo and Inés María Martiatu Terry. Havana: Editorial de Ciencias Sociales, 2011.

- Arroyo, Jossianna. Travestismos culturales: literatura y etnografía en Cuba y Brasil. Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh, 2003.

- Ayorinde, Christine. Afro-Cuban Religiosity, Revolution, and National Identity. Gainesville: University Press of Florida, 2004.

- Bharucha, Jamshed J. “Musical Cognition and Perceptual Facilitation: A Connectionist Framework.” Music Perception 5, no. 1 (1987): 1–30. https://doi.org/10.2307/40285384.

- Bharucha, Jamshed J., Meagan Curtis, and Kaivon Paroo. “Varieties of Musical Experience.” Cognition 100, no. 1 (2006): 131–172. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.cognition.2005.11.008.

- Batiuk, Elizabeth Kimzey. “Kinetic Conversations: Creative Dance-music Performance and the Negotiation of Identity in Contemporary Havana, Cuba.” Ph.D. diss., University of Michigan, 2015.

- Becker, Judith. “Anthropological Perspectives on Music and Emotion.” In Handbook of Music and Emotion, edited by Patrik Juslin and John A. Sloboda. New York: Oxford University Press, 2001.

- Benveniste, Emile. “Subjectivity in Language.” In Problems in General Linguistics, translated by M. E. Meek, 223–30. Coral Gables, FL: University of Miami Press, 1971.

- Berger, Harris. Stance: Ideas About Emotion, Style, and Meaning for the Study of Expressive Culture. Middletown, CT.: Wesleyan University Press, 2009.

- Berger, Harris, and Giovanna Del Negro. Identity and Everyday Life: Essays in the Study of Folklore, Music and Popular Culture. Middletown, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2004.

- Berthoz, Alain. The Brain’s Sense of Movement. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2000.

- Blommaert, Jan. Discourse. New York: Cambridge University Press, 2005.

- Blue, Sarah A. “The Erosion of Racial Equity in the Context of Cuba’s Dual Economy.” Latin American Politics and Society 49, no. 2 (2007): 35–68. https://doi.org/10.1353/lap.2007.0028.

- Bodenheimer, Rebecca M. “Localizing Hybridity: The Politics of Place in Contemporary Cuban Rumba Performance.” Ph.D. diss., University of Berkeley, 2010.

- ———. “National Symbol or ‘a Black Thing’? Rumba and Racial Politics in the Era of Cultural Tourism.” Black Music Research Journal 33, no. 2 (2013): 177–205. https://doi.org/10.5406/blacmusiresej.33.2.0177.

- Bosse, Joanna. “Salsa Dance and the Transformation of Style: An Ethnographic Study of Movement and Meaning in a Cross-Cultural Context.” Dance Research Journal 40, no. 1 (2008): 45–64. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0149767700001364.

- ———. “Salsa Dance as Cosmopolitan Formation: Cooperation, Conflict and Commerce in the Midwest United States.” Ethnomusicology Forum 22, no. 2 (2013): 210–231. https://doi.org/10.1080/17411912.2013.809256.

- Cabezas, Amalia Lucía. “Discourses of Prostitution: The Case of Cuba” In Global Sex Workers: Rights, Resistance, and Redefinition, edited by Kamala Kempado and Jo Doezema. New York: Routledge (1998): 79–86. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315865768-7.

- Caram Léon, Tania. “Un Estudio Sobre El Empoderamiento Femenino En Cuba.” Ciencias Sociales 90–91 (IV-2000, no. I-2000): 43–63.

- Cashion, Susan V. “Educating the Dancer in Cuba.” In Dance: Current Selected Research, Vol. 1, edited by Lynette Y. Overby and James H. Humphrey. New York: AMS Press, 1989.

- Centeno, Miguel Angel, and Mauricio Font, eds. Toward a New Cuba? Legacies of a Revolution. London: Lynne Rienner Publishers, 1997.

- Chaguaceda Noriega, Armando. “Cuba, Citizen Participation and Associational Space: Some Notes.” Change in Cuba. SSRC, last updated May 14, 2008. http://essays.ssrc.org/changeincuba/2008/05/14/cuba-citizen-participation-and-associational-space-some-notes/.

- Chao Carbonero, Graciela, and Sara Lamerán. Folklore Cubano I, II, III, IV. Havana: Editorial Pueblo y Educación, 1982.

- Childs, Matt D. “Pathways to African Ethnicity in the Americas: African National Associations in Cuba During Slavery.” In Sources and Methods in African History: Spoken, Written and Unearthed, edited by Toyin Falola and Christian Jennings. Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2004.

- Clarke, Eric. “Expression in performance: generativity, perception, and semiosis.” In The Practice of Performance: Studies on Musical Interpretation, edited by John Rink. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press, 1995. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511552366.003.

- ———. “Meaning and the Specification of Motion in Music.” Musicae Scientiae 5, no. 2 (2001): 213–234. https://doi.org/10.1177/102986490100500205.

- ———. Ways of Listening: An Ecological Approach to the Perception of Musical Meaning. New York: Oxford University Press, 2005. https://doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195151947.001.0001.