Matters of Empathy and Nuclear Colonialism: Marshallese Voices Marked in Story, Song, and Illustration

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

The United States detonated 67 nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands from 1946 through 1958. During this period, the archipelago was part of the U.N. Strategic Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI), which was administered by the United States. The tests and scientific and medical programs were shrouded in secrecy; information about the tests conducted on Marshallese bodies and their lands remains largely classified. I conducted ethnographic work from 2008 through 2010 in what is now the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), politically autonomous from the United States since 1986, and in northwest Arkansas and southwest Missouri from 2011 onwards. Marshallese will often note that they do not have a written history; rather, they rely on their voices to interactively share their oral histories in story and song. My Marshallese interlocutors living in the RMI and US stress the value of collecting these dynamic oral histories as well as utilizing them for pedagogical purposes and in platforms for social justice at events like the annual Nuclear Remembrance Day ceremonies. In 2013, I co-founded the Marshallese Educational Initiative (MEI), an Arkansas-based nonprofit to develop intercultural pedagogy and outreach through projects such as the Marshallese Oral History Project and Digital Music Archive (MOHP), Nuclear Remembrance Day, and collaborative work with Marshallese college student members of the Manit Club (Culture Club).

In this article, I define Marshallese voices in terms of material and political representations. The word for voice and sound are the same in the Marshallese language (ainikien). Voice is its sonorous materiality, but it also represents the throat, where various physiological and emotional processes coalesce. Marshallese body perception of the throat as the center of the emotions also speaks to larger notions of connectivity, communication, and social values. Marshallese social organization is based on land and lineage, specifically, land is inherited through matrilineal orientation. Unlike western notions of property, every Marshallese is born with land and thus rights on and from that land. Decolonization, as a form of nation building, depends on a Marshallese politics of the voice. These voices mark colonial encounters and two political ontologies.

The United States detonated 67 nuclear weapons in the Marshall Islands from 1946 through 1958. During this period, the archipelago was part of the U.N. Strategic Trust Territory of the Pacific Islands (TTPI), which was administered by the United States. The tests and scientific and medical programs were shrouded in secrecy; information about the tests conducted on Marshallese bodies and their lands remains largely classified. I conducted ethnographic work from 2008 through 2010 in what is now the Republic of the Marshall Islands (RMI), politically autonomous from the United States since 1986, and in northwest Arkansas and southwest Missouri from 2011 onwards. Marshallese will often note that they do not have a written history; rather, they rely on their voices to interactively share their oral histories in story and song. My Marshallese interlocutors living in the RMI and US stress the value of collecting these dynamic oral histories as well as utilizing them for pedagogical purposes and in platforms for social justice at events like the annual Nuclear Remembrance Day ceremonies. In 2013, I co-founded the Marshallese Educational Initiative (MEI), an Arkansas-based nonprofit to develop intercultural pedagogy and outreach through projects such as the Marshallese Oral History Project and Digital Music Archive (MOHP), Nuclear Remembrance Day, and collaborative work with Marshallese college student members of the Manit Club (Culture Club).

In this article, I define Marshallese voices in terms of material and political representations. The word for voice and sound are the same in the Marshallese language (ainikien). Voice is its sonorous materiality, but it also represents the throat, where various physiological and emotional processes coalesce. Marshallese body perception of the throat as the center of the emotions also speaks to larger notions of connectivity, communication, and social values. Marshallese social organization is based on land and lineage, specifically, land is inherited through matrilineal orientation. Unlike western notions of property, every Marshallese is born with land and thus rights on and from that land. Decolonization, as a form of nation building, depends on a Marshallese politics of the voice. These voices mark colonial encounters and two political ontologies.[1]

Drawing from Adriana Cavarero and Jacques Rancière, among others, who have explored the politics of voice as first and foremost a question of the sensible (and its distribution), and anthropologists Amanda Weidman and Laura Kunreuther who have considered the postcolonial associations of voice in terms of subjectivity and co-constitutive realms of private and public expressivity, I extend discussions of the voice and politics, and the politics of voice, to offer a contemplation on how vocal materiality can afford productive conversations around the relationship between empathy and nuclear colonialism.[2] I work through the ways in which some Marshallese voices are heard as marking the nuclear legacy. By marking the claims for nuclear remediation, Marshallese voices, compromised, ask us to listen beyond nuclear spectacle and within the realm of the silent possible where we might hear social justice as a matter, the matter, of land, soul/body, and genealogical claims (claims against damages and to restorative justice).[3] Moreover, humans’ bodies are often erased from the iconic images and sound symbolism that bolstered nuclear weapons testing following the wartime usage of atomic weaponry in Hiroshima and Nagasaki. When we listen to Marshallese voices on Marshallese terms of the throat (bōro), we can better think through the reaches of US sounds of Marshallese and US nuclear hegemony as part of colonial relations founded on bipower and bioproductivity, that push and expose the transcorporeal limits and connections of human and environmental bodies.[4] It is here that we begin to work against what Walter Benjamin has termed the “double silence of history,” which is the silence of history from the standpoint of those subjugated as well as their traditions and culture.[5]

To consider the intersections of advocacy, education, and cultural constructs of voice, orality, and history, I open with an overview of the Marshallese Educational Initiative and our Marshallese Oral History Project. In doing so, I open a point of critical investigation to consider the ways in which voice and its material bases can provoke notions of voice as unmediated access—not so much in terms of identity and interiority but rather to empathy as an activating force for social change—and the attendant political consequences. Framed by the need to take seriously interlocking notions of voice and social systems of diasporic communities, I pose interpretive challenges to existing models of oral history collection, musical transcription, analysis, and pedagogy by proposing a systematic engagement of graphic representation, anthropology of the senses, and musical ethnography.[6] Working with Marshallese diasporic communities in Arkansas and Missouri, I share collaborative Marshallese representations of a repertoire I have termed “radiation songs” to consider the potential impact of decisions concerning listening multimodally—to graphic representation and voices talking stories— on intergenerational transmission and in intercultural outreach efforts.

The Marshallese Educational Initiative: In Terms of Voice, Orality and History

The RMI is an autonomous country that, given US nuclear violence and economic as well as militaristic control over the nation, continues to struggle for self-determination. Centuries of colonial involvement have disrupted the social organization of the islanders living on the central Pacific archipelago, and decolonization efforts have continued since the 1970s. Approximately 55,000 Marshallese live on the islands, but due to high unemployment and a lack of adequate healthcare and educational opportunities in the country, Marshallese have been migrating to the United States in increasing numbers. As part of the 1986 Compact of Free Association with the United States, Marshallese are allowed to travel and work in the United States without a visa. Migrating first to Hawaii, Guam, and the coast of California, the majority of Marshallese now reside in the Midwestern and Southern United States, where many relocated to work in the poultry industry in Springdale, Arkansas. According to the 2010 US Census, more than 22,400 Marshallese reside in the United States. By 2016 the region-wide Marshallese population in northwest Arkansas was estimated between 12,000-15,000.[7]

The centrality of educational regimes to conversion and colonialism cannot be overstated. Schools were first brought in the 19th century by missionaries and after World War II public education was put into place by Americans. Self-determined education is also important in decolonization. RMI government official Jibā Kabua writes, in “We are the Land, the Land is Us: The Moral Responsibility of Our Education and Sustainability,” that education must belong to the Marshallese, traditionally a subsistence-based culture, and that is a question of survival. Kabua demands that Marshallese adapt to the changes that are brought about by modernization and development rather than feel paralyzed, and this must be done, he stresses, through education that takes into consideration “Pacific cultures and identities” and directed at “economic growth aimed at a new level of economic productivity.”[8] The author closes with a call: “Education for survival is a call to duty for every Pacific person. Land, culture, and education are the only tools available for the Pacific family to brace itself against the powerful forces of globalization that now threaten the very survival of the average Pacific person.”[9]

This increasingly popular sentiment contributed to the founding of the Marshallese Educational Initiative in 2013. I co-founded MEI with Dr. April L. Brown, but the organization came together because of Marshallese interest and governmental officials facilitating connections. Brown, a history professor at NorthWest Arkansas Community College (NWACC), was concerned about the decreasing Marshallese enrollment, and she decided to host a Marshall Islands themed semester. Following my ethnographic work in the RMI from 2008–2010, I had made repeat visits to northwest Arkansas. Members of the RMI Consulate in Springdale, Arkansas knew of the themed semester and wanted my input on hosting a cultural event. The planning committee invited me to speak at a January 2013 event at NWACC with an audience of Marshallese and non-Marshallese residents, students, and faculty. As hoped, the event generated much dialogue between the Marshallese community and us educators about events, workshops, and other projects that would facilitate American understanding of Marshallese experiences and help Marshallese living in America learn about their culture (language, lineage, land, history). Brown and I compiled the ideas in a dossier and sought funding. Although we had garnered local media attention and Marshallese interest, financial support for an un-organized collective proved difficult, and we founded MEI.

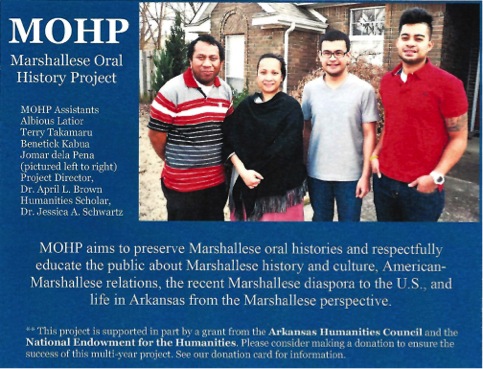

MEI began with two main projects: Nuclear Remembrance Day planned for 2014 and a Marshallese Oral History Project (MOHP) (Fig. 1). In 2013, MEI received support from the Arkansas Humanities Council/National Endowment for the Humanities to develop MOHP. We worked with young Marshallese who were involved in their community, Albious Latior, Terry Takamaru, Jomar dela Pena, and Benetick Kabua Maddison. All were bilingual and had experience as interpreters and translators. They also wanted to share their culture with others and archive their elders’ stories, which they feared were being lost. Brown served as the project director, and I was the humanities scholar for the project. Drawing from various ethnographic and oral history instructional methods, I developed a collaborative method with the MOHP staff to plan, collect, and process Marshallese stories and Brown followed the best practices established by the Oral History Association in terms of the physical process of collection. The goal was to interview fifty community members selected by the Marshallese team members for their specialized knowledge and experiences and position within the community. The interviews, which were videoed, were conducted primarily in Marshallese.

As the project commenced the two major difficulties resulted from what constituted the oral history and what was considered “talking story” (bwebwenato). Oral histories were assumed to be more focused and more formal as well as individualized in comparison with bwebwenato, which was more dialogic and dynamic. Marshallese intergenerational sharing would better approximate our conceptual model for why oral histories are necessary in terms of cultural and epistemological activation. However, the practical models for acquisition, collection, archiving, and dissemination did not line up. While the oral histories seemed to privilege stories around an event (historical), bwebwenato often interwove place names, legends, and other stories from which a highly textured and referentially dense production emerged. We needed a dynamic way of organizing the material, and, from the second major difficulty, it became clear that neither history nor orality would provide that for us. The second point of contention had to do with transcription and translation, which are interrelated. Marshallese working on the project became protective of the sounds of the Marshallese language given that they represent and are inherited from the material and conceptual bases of the culture: land (environment) and lineage (ancestors). Some prefer the Marshallese-English Dictionary’s orthography because it emphasizes etymology and allows a voiced enactment of the land-based genealogy through the unique and meaningful sounds of the Marshallese language.

The Marshallese-English Dictionary (1976) was written during the period that saw the beginning of Marshallese active nuclear decolonization. Not only were Marshallese voices marking their de/colonial subjectivities through the concept of having (or not having) political voices, they were stressing the material bases of these voices in a wealth of land-based and textual domains. They were also creating their own material bases from which voices could be routed and rooted back through the land. In 1994, the RMI government opted to standardize Marshallese orthography along the lines of the dictionary. With the further incorporation of voice into the project of nation building, all materials teaching the Marshallese language in schools were expected to use the standard orthography. The task proved unrealistic since the government did not have (or allocate) the funds to replace the texts. Moreover, there is other print material in the Marshallese language that continue to use the missionaries’ orthography or a combination of different alphabets. In the United States, Marshallese community leaders with whom we consulted felt the dictionary orthography would be of most benefit to those researching or utilizing the MOHP, which has plans to include a Digital Music Archive.[10] This is based on the projection that the dictionary will become increasingly utilized in future years, especially with outmigration increasing. For now, Marshallese prefer to listen to the oral histories.

Others working on the MOHP value the orthographic models established by the nineteenth-century missionaries because they feel that writing is the language of the Bible and the hymns. They also feel that the dictionary is written for an American audience and oversimplifies the meanings of the words, many of which are considered to be untranslatable or reduced to a written language, and lacks expressive vocabulary. Alfred Capelle, who co-wrote the first and only Marshallese-English Dictionary with Tony deBrum and Byron Bender, took pause when we discussed the missionaries’ orthography. The missionaries, Alfred suggested, were not equipped to perform such “reductions” because they came to the islands and listened to Marshallese speakers with “foreign ears.”[11] “Foreign ears” were not attuned to the nuanced sounds of the Marshallese voice and what the voiced sounds represented. Even when missionaries became sensitized to such sounds, the English alphabet could not accommodate the sounds in or outside of language, such as meaningful sounds in the environment. Still, the missionaries commenced a thorough “disciplining of the senses,” and they taught the Marshallese how to listen for languages shaped by the written symbols—the “incomplete” English alphabet and western music notes—printed in books.[12]

The missionary encounter paved the way for US military involvement in the RMI. As The National Geographic Magazine September 1945 edition comments:

Missionaries made friends for America ... Americans have had more influence [in the Marshalls] than any other people ... In the 1850s, the American Board of Foreign Missions in Boston spread its activities into Micronesia from Hawaii. Subsequently, they reduced the Marshallese language to writing; gave the people schools, medicines, a new religion; and brought conflicting clans to peace.[13]

Both the missionaries and military emphasized their pursuits for a larger, universal “good.” As with any relationship, a mutual good requires understanding and attention to the perspectives of both parties. In other words, it requires empathic responsiveness on various levels. What we see in the above block quote is less about collective understanding and more about a disciplinary mode based on western terms of education, science, and sociality. And, if these western terms were based on a universal good, then Marshallese terms that were unintelligible to western terms were parsed and excised. In terms of history, we can understand the production of Marshallese oral history as a larger project of abstracting Marshallese from their social organization, the land. Oral history, as the spoken form of written history, is not a Marshallese concept. Marshallese practice storytelling and song stories that are journeys. Both have momentum that connect the past through the present and a directedness into the future so that the near-present is realized by ancestors and through the land. The voice is one way to realize this spatio-temporal relation. The Marshallese-English Dictionary includes place names and a story about navigation with translations and etymologies. There are also illustrations. Together, the dictionary teaches the ways in which the voiced sounds of the Marshallese language are in the materiality of land and lineage. Interestingly, in terms of contact with Americans, the missionary orthography also speaks to the ways in which lineage is marked and land can be marked with words. Marshallese will often say that it doesn’t matter which orthography one uses, the sounds of Marshallese words will be the same when spoken or sung. Their comments emphasize the belief that Marshallese sounds have a certain fidelity to their cultural coordinates that western modes of representation (writing does not).

One of the MOHP community organizers, Benetick Kabua Maddison, served as the principal translator and transcriber for the MOHP and was an advocate for the usage of the dictionary for precisely this reason. Maddison is fluent in Marshallese and knowledgeable about Marshallese customary vocal practices. He stressed the need to utilize the dictionary orthography at a panel at the annual meeting of the Pacific Coast Branch of the American Historical Association that Brown and I were also a part. He explained the particular sonorous morphemes of the Marshallese term for atoll that when sounded together signify an atoll as well as its formation and connective importance to the islands. He stressed that only the dictionary’s orthography can approximate and thus preserve, in practical terms, the relational components of the atoll or “aelōñ” (ae-currents, lōn-that which is above). The currents, in Marshallese communications networks, form the basis for their gathering on the land.[14] In contrast to this written representation, the missionaries’ spelling is “ailin,” which is pronounced incorrectly as 1) a whole without parts and 2) a mishearing of the English word for “island.” Maddison also stressed that even if Marshallese pronounce “aelōñ” correctly, the circulation of “ailin” will obfuscate the Marshallese origins of the term and its connective meaningingfulness based on wave navigation (which is not understood by westerners). While there are many words like this that come to resound the matrilineal ties, cultural orientation, and strengths of Marshallese customary practices through morpheme groupings, Maddison’s choice to exemplify this point with the word that speaks to the foundational material of Marshallese culture—atoll (as environment rather than atoll or island)—shares the importance of vocal practices in caring for that which westerners have continually reduced through writing or other imperial violence, such as wars. Maddison’s presentation was part of a panel that addressed the ways in which MEI aimed to utilize MOHP as a type of advocacy-based pedagogy. We hoped that highlighting those disparate translations could generate a conversation about how oral histories often work against self-determination when couched in colonial terms.

Deconstructing Oral Histories through a Vocal Ontology of Connections

If Marshallese maintain that their voiced language and other expressive sounds cannot be reduced to written representation, are their ways to realize Marshallese interests in preservation (or, if we look at it in another way, cultural activation) that are less reductive? How are new voiced sounds that speak to the changes brought by colonial encounters and imperial violence, such as nuclear weapons testing, and now anthropogenic climate change, to be archived in meaningful ways? Part of colonial violence has been the disruption of indigenous agencies, which are routed in and through their expressive means. How can bringing voice, and its material bases, to the fore help in decolonial projects as well as reach across epistemological and cosmological divides to create a common sense of shared responsibility for decolonization?

Oral history projects, especially those that are geared at humanitarian and justice-based efforts on behalf of marginalized and subjugated communities, often assume that the documentation of personal stories takes on a politicized tenor through the activation of readers’ or listeners’ empathy. Empathy is the ability to understand and respond appropriately to another persons’ emotional state and perspective. Stories do create bonds, care, and concern. They generate powerful emotions, but many times, and in our hyper-mobile culture, it is difficult to sustain any momentum from feelings of concern or kinship. Larger projects would take stories, and their innerworkings, and focus on the meaning and values of people speaking, directing listening to the consequences of the violence that unfold slowly.

This is the intent of MOHP’s critical thrust. We understand the study of voice in decolonial educational projects to be crucial to the projects themselves. When understanding that Marshallese language (through the sounds) enables voices to activate the throats and the lineage and land, we understood that we needed to have a layered tool for dissemination that would enable us to simulate these material aspects and different genealogies. The Digital Music Archive, then, will present oral histories that are neither primarily oral nor historical in the western sense. We begin with the sounds of Marshallese and the musical composition of these sounds, but we also aim to layer familial voices, drawings, stories, and travels through the land and back through the throat, as a site where listening to specific political voices is an empathetic resonant gesture. This educational tool emerges from exploring the voice as a physical manifestation of the throat, which is the seat of the soul and emotions in Marshallese body perception. Metaphorically and literally, attention to the throat decolonizes the voice from its nuclear confines that link voice to politics through an abstraction from speech. Language, voiced, becomes the mechanism to show the limits of voice (detached from its generative materiality) rather than limit the voice to a bounded language (be it nuclear-centered or otherwise). This is a common misconception. For example, in Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self (2010), Stacy Alaimo explores the movement between bodies, human and those of the environmental surroundings, citing, for example, the speech of trees that could not be reduced to human language or representation.[15] Alaimo is writing from a perspective that imagines human language or representation as textually based, or word-based, and not as based on sounds of the voice that index sounds of ancestral bodies, which could be rocks and trees, and lands.

MOHP is an active deconstruction of oral history. It is not marked by events and orality. Rather, it draws from voices sounding environmental marks to create alternative island-based and diasporic genealogies. Marshallese songs, stories, and illustrations have become central to this endeavor. We began speaking with influential musicians as they came through Springdale for family gatherings, musical tours, or both. We also began collecting commentaries from Marshallese that focused on aural perceptions since voices pick up the sounds of the environment and persons retain their environment and lineage by voicing Marshallese sounds properly. What are Marshallese in Arkansas voicing or what do they feel is absent from their acoustical worlds in diaspora? Many Marshallese in Arkansas are interested in MEI creating a nuclear educational course that is based on historical facts of nuclear colonialism and also offers students a way to address the testing on a human level, through empathetic means. We have endeavored this in a number of ways.

In 2014, MEI hosted a Nuclear Remembrance Day ceremony at the William Jefferson Clinton Presidential Center in Little Rock, Arkansas. The audience was comprised of Marshallese from neighboring Springdale, Arkansas, non-Marshallese from northwest and central Arkansas, and guest speakers from the Marshall Islands, such as Rongelapese Senator Kenneth Kedi and RMI Ambassador to the US Charles Paul. I shared with the audience an excerpt of the video of “Kajjitok in aō nan kwe kiio” (These are my questions for you now, still) that was written by Lijon, an energetic and creative composer, anti-nuclear activist, and advocate for responsible solutions to climate change. Lijon wrote the song in 2008 for the Department of Energy, which, like the Atomic Energy Commission, would not answer the questions of her community, specifically her older and younger sisters, as she explained.

The Rongelapese remained on their contaminated homeland from 1957 until 1985. Over the course of twenty-eight years, the islanders were part of Project 4.1, which was a top-secret study that documented the effects of radiation on human beings. They became increasingly ill. Both men and women suffered from thyroid problems and cancers, necessitating multiple surgeries and removals. The thyroid examinations and removals that were Project 4.1 were devastating on a number of registers. Many Marshallese have visible scars on their necks as reminders of the surgeries that caused many of them issues with their voices and communication. Rongelapese women, hearing their lowered, altered voices would hear themselves as ribaam (bomb people). The throat is agency, in its materiality, taking in sustenance and producing voice, and a damaged throat shares through vocal pathology resulting from thyroid problems, disrupted agency. Women would explain that they would not speak or sing for periods of time after the surgeries in fear of hearing their altered voices and enduring a gendered stigmatization.

Questions concerning nuclear weapons exposure increased as the population commemorated the sixtieth anniversary of the Castle Bravo test without much change or responsiveness from the United States government. To impress these questions within the fabric of the MOHP, we also sought out musicians from affected communities and asked their input on best practices of transcription of what has been described by interlocutors as “thyroid,” which is the breaking of voices due to radiogenic thyroid problems. I shared many examples from previous and forthcoming scholarship, including an example from a previous essay I wrote for this journal in 2012, “‘A Voice to Sing’: Rongelapese Musical Activism and the Production of Nuclear Knowledge” that emphasized the role of Rongelapese women’s musical activism (vocality and musicality) in marking the nuclear legacy, which has often played out in secrecy and silence on various levels and in various domains, “felt” and “thought.” The example was of a performance of the song, “Kajjitok in Ao Nan Kwe Kiio” from 2009. As they sang the song, their voices fell silent and emerged with an unsteady acoustic dissonance. The conductor, Betty, pointed to her throat and said “Ah, tyroit” to clarify that what had happened was the physical manifestation of, song’s lyrical content. This particular performance took place at the Nuclear Victims’ and Survivors’ Remembrance Day ceremony on Majuro Atoll, the capitol of the Republic of the Marshall Islands.[16]

Thyroid: Song in the Absence of Voice

I met Faith Laukon Jibas in Springfield, Missouri prior to the founding of MEI. While in the RMI, I had worked with her family members and sought her out during my first visit to Springfield. Jibas, who is Rongelapese, drew two graphic representations of the performance. She explained of her drawings,

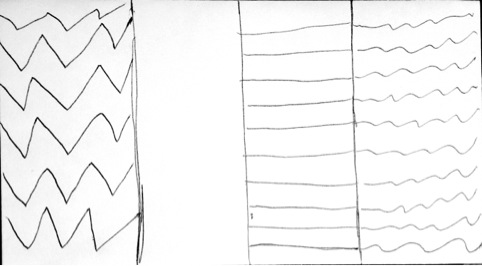

“It’s a break in your melody in your throat. We’re flat, and low, and there’s a breakage. Flat, and sharp, and inconsistency. They can’t reach the note because it’s like they are hoarse. They can’t sing because it is like they are in a constant state of puberty.... Their voice is not stable. We are often teased about being flat or sharp or not being in tune. If you are not sounding good, they say, oh, she’s super flat, whenever you don’t sing good. The Rongelapese women...they sing super low.”[17]

The illustration (Fig. 2) shows the movement of the voices, albeit with a lack of vocal control and unpredictability, prior to the moment of silence. The jagged movements precipitate the stark silence that then flattens out to one tone and then a wobble or warble that might approximate a roughness, or a sensory dissonance, similar to microtonal beating, perhaps.

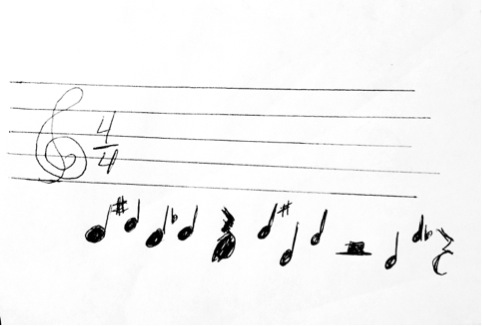

The second drawing (Fig. 3) shows both the “lowness” registrally – as in the women’s voices do not even map onto the treble clef – and it also shows the chaotic “noisiness” of the melody. Faith uses notes because of her training as a music educator and the Marshallese training in church.

Neisen Laukon, Faith’s mother, grew up on Rongelap Atoll. She was not there when Bravo was detonated, but moved back with her family in 1957 when the Rongelapese were relocated to their atoll. She recalls eating food from the land that would blister her lips and make them swell. She also has been subject to countless medical tests and different medication regimes. The Department of Energy (DOE) would fly her to places such as Hawaii, provide accommodation, and give her “a box full” of new medications. She developed growths under her arms and frequent nose bleeds, but the DOE doctors refused any causality between the radiation and her ailments. Neisen is not sure she agrees with the medical assessment, or the public assessment. She is sure of the pain her family has experienced during the surgical operations on their thyroids. As Neisen spoke during Nuclear Remembrance Day 2014 in Little Rock, she invited her cousin, Jonitha, to the stage. Her cousin was silent, but Neisen spoke on her behalf and has subsequently spoken at a handful of national venues since her 2014 appearance. When Neisen was asked to illustrate the sound of “thyroid,” she also offered a drawing where there is a very large heart outside of the woman, who is presented only as a throat and face (Fig. 4).

“My cousin was really scared whenever they said they were going to cut her throat. She said I may never talk ... mute, you know. Sing. They can’t sing and she was scared. The woman is down and out, depressed. Tears. How do you draw, or write in, that emotion? It’s like a knife, or a stick through the heart. The woman—she has a sad face. She is crying, and this represents the emotion. Scared, hurt, angry. It’s like a knife through your heart.”[18]

The throat is cut all the way across, and the knife connects the throat to the heart. The woman is crying, another impediment to vocal communication (when someone is “choked up” with a lump in her throat). This is a permanent “lump” in the throat, causing the voice to sound permanently different and have the Rognelapese imagine their hearts and Americans’ hearts as something outside of them. This speaks to the feeling that outsiders cannot understand Marshallese ways of loving, caring, and being, and thus they cannot feel empathy for Marshallese.

In the summer of 2012, I showed Neisen the 2009 performance of “Kajjitok in Aō Nan Kwe Kiio,” and she laughed; Betty, the conductor, was staying in a house in Springfield, Missouri just ten minutes away from where we were. When I met with Betty at the house, she recounted the stories of the men in operating suits leading her in corridors and then to surgery to have her thyroid operated. She spoke of the women with thyroid problems and the nuclear damages faced by her community. Betty, however, was more excited to share stories of the Rongelapese noniep (spirit gnome) who taught a man drumming in a dream. The man then taught the women drumming, which helped protect their land. Women customarily participated in battle over land by providing the rhythmic accompaniment to war. They would also throw themselves in the middle of a fight if it became too heated or too many people would be killed or injured. With nothing else but my iPhone, I quickly began to record the kinesthetic display that included hand-clapping games set in motion through chanted legends in song. The stories of forcible movement Betty recounted that were indicative of the nuclear weapons testing.

Radiation: Voice in the Absence of Movement

Valentina, a Bikinian woman living on Ejit, an island the size of a football field in Majuro Atoll, composed “Radiation.” The song is a lament that details incommensurable losses and incurable problems caused by nuclear testing. In July 1946, the US began testing atomic weaponry on Bikini Atoll, and the community remain displaced because of the lingering radiation. The first verse of the song tells of the singer mourning her homeland—the place she grew up. The second verse tells of the appearance of radiation and the resulting problems, and the third verse shares her suffering and dislocation. The song includes questions, such as how to “solve problems of” the throat and “getting rid of suffering.” A disturbed throat causes problems and suffering, and, from the outset of the song, Valentina laments that she is būromōj. Būromōj literally translates to “dead throat” or “deactivated throat” (burō – throat and mōj – dead, numb). The voice sounds the immobile throat, apathy.

Bikinians feel that singing songs like “Radiation” help attract attention of Americans. Some allude to legendary figures in Marshallese mythology: the female lōrrọ and the male būroṃōj who suffer from the grief caused by the loss of their male or female counterpart, respectively. Today, the figures are representative of the nuclear exiles away from their land that sing their severed land-based genealogy and sociality as lament. The throat and the conception of the healthy throat are inextricably connected to this important animating force in Marshallese culture. The ability or inability to express emotions depends on an entire social network, knowledge of a lineage, and a “healthy throat,” which comes from communality. Without personal and collective vocal delivery of the material-discursive inheritance, jitdaṃ kapeel (a Marshallese proverb, seeking knowledge guarantees wisdom, that is also a practice of asking about one’s ancestry) cannot function properly either, and this creates an impediment in customary pedagogical practices and inquiry. There are also periodic rests in the middle of phrases. Prominent among these is the aforementioned moment following the first iteration of “Radiation” as well as the pause within the text setting of the song’s final cadence. Another affective pause occurs in the first line of the third section, and it prefigures the most rhythmically dense and stilted conveyance in the entire song. The vocal performance of the words, “on an island that is not mine,” is akin to a recitation, displaced, and recalls Marshallese roro, which, in excited performance, literally brings in air to the sails (oxygen to the lungs through the “throat”/windpipe) of a person and her community. With a “dead” throat, the ability to bring air into the sails is diminished, and Marshallese immediately notice this performed depressed respiratory and spiritual performance as a matter of the community in pain. Even prior to nuclear testing, Marshallese based their evidence of apathetic outsiders (explorers and ethnologists) on their inability to hear or see the figure of the lōrrọ, singing out her loss.

I played “Radiation” for Faith’s parents and many other Marshallese and they would exclaim - “She is singing like a man!” I decided to call a Marshallese friend and colleague who lives in Arkansas and works occasionally with MEI to ask her how she would imagine writing the song. Sharlynn is from Ebon Atoll (the southernmost atoll in the RMI) but her father-in-law, with whom she was very close, was a respected Bikinian elder. She feels the nuclear testing on a very personal level, but I wondered if she would be familiar with the song “Radiation,” since she had been living in the United States since 1993. Whether or not she knew the song would be helpful in understanding limits and connections across sound-based and musical domains of the diasporic network. I played her the recording over the phone and, without even getting to my question concerning transcription, she immediately responded and with rapid pace, “I know that song. It’s a Bikinian song. She is singing like a man to imitate all the elder men—those leaders who were men, such as King Juda. The leaders would compose the songs, not the women. Most of our history is not written, it is passed down by our voices and movements.”[19]

After listening to this song, Sharlynn stated, “there is no movement. She is sitting by herself, and because there is no movement, the voice must convey the meaning. She is not with us. She looks to the past and the future, but not now. Where can she survive? She is lost without her land, and it is like she is crying. This situation is beyond slavery.” That the voice must convey the meaning seems an obvious statement, but let’s recall vocal ontology as a journey through time and space. Without the ability to journey, Valentina must use her voice to convey meaning rather than have meaningful experiences based in person-land interaction to convey (or sound) the voice. Furthermore, Marshallese society is customarily matrilineal. The removal of women from their homeland is one form of gendered violence, then, assumed by the throat as a marker of a severed society, which we heard with the Rongelapese performances. Sharlynn refused to draw a representation, and she was physically uneasy and anxious, stressing that she could not imagine it as a drawing. After it was suggested that a blank page could be her representation, she nodded.[20] Sharlynn would not begin to consider how the song would be represented visually because, she noted, there is no way of relating to that spatiotemporal experience and the extreme despair of knowing your land and your heritage, so unique to your animation as a human, are forever destroyed. Without a journey, there is nothing to convey but the abstracted voice.

“Radiation” is part of a repertoire of songs I have earlier called “radiation songs” that document the consequences of nuclear weapons testing, use a nuclear-centered language and also often include appeals for help and understanding. The songs include questions with silent spaces for ethical response, for answers, and for empathy. It was composed around 1985/6, which is the beginning of this style of music and activism, both of which are part of obtaining a political voice in self-determination. The years mark a turning point in the politics of sound/music/voice for Marshallese populations, such as the Rongelapese, that had been exposed to lethal doses of radiation. In 1986, the Marshall Islands received political autonomy from the United States with the Compact of Free Association, for which neither the Rongelapese nor the Bikinians voted. They were concerned their ability to negotiate with the United States and their resources for health and relocation would be taken out of their purview. Part of this decolonial move was to bring outside assessment of radioactive levels to the islands. While they had previously been isolated and sequestered on camps and, as we read, listless and drifting on their island, new tests from Japanese scientists that revealed contamination in the soil and new political agency inspired musical activism. Obtaining a political voice while still being būromōj (having a dead throat) shows that decolonization remains incomplete.

Conclusion

Voice, as discipline, concept, compass, barometer, sound, and so forth, must be critically assessed in any educational project. In terms of the present-day Marshall Islanders’ fight for nuclear justice, which is central to decolonization, the figures of the irradiated and immobile voice predominate. These nuclear affected voices are amplified by voice as a political tool but are anathema to the other metaphors of voice and projects concerning voice that Marshallese have deployed in their decolonial process, such as the dictionary. Working with the Marshallese Educational Initiative, I have begun to consider and implement new modes of voicing that mark connections across Pacific space-time through (but not defined by) the terms of oral history. The MOHP and Digital Music Archive offer ways of asking how voice, as educational, exists as part of power aggregations and can be used in reconfigurations. These questions are all the more pressing, perhaps, in diaspora since some Marshallese never see their land and are unable to speak the language. This has created a good deal of tension and lapses in intergenerational communication.

In terms of political voicings that mark nuclear damages and the need for empathy (by connecting the voice to the throat and not to the page/law), the central research questions need to move beyond documentary parametric conventions as they relate specifically to western culture. To move beyond these research questions while working within and respecting their value to scholars as communicative, collaborative work with interlocutors within the medium of representation offers a way of tangibly accessing beyond the coordinates the researcher’s “foreign ear” defines. Sharlynn’s refusal to think about the Bikinian song as represented in notes, like those of the hymnbook with which she is familiar, or as a drawing that would to her be utterly reductive, is telling. It speaks to the unthinkable magnitude of the bomb and its existence as a “hyperobject,” with human-environmental (transcorporeal) ramifications beyond our lifetimes.[21] The bomb in this way is coupled with the environment and ancestors, making them immobile as well, since they are outside the span of an individual’s lifetime. Coupled with Neisen and Faith’s illustrations, we can read the breadth of nuclear colonialism on the expressivity, physiology, and emotional connectivity of the Marshallese. Their bodies have been mined, with parts extracted in pursuit of other nuclear knowledge (lymph material from around the thyroid, for example). There is not one aspect of life left untouched by the colonial intrusion of radiation. Together, the representations push at each other’s limitations, highlighting new intelligibilities and interventions to hear the unsaid, unheard-of empathy and justice.

Bibliography

- Alaimo, Stacy. Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self. Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010.

- Capelle, Alfred. Interview with author. Majuro, Marshall Islands. May 2010.

- Cavarero, Adriana. For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, trans. Paul A. Kottman. Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005.

- ———. For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, trans. Paul Kottman. Stanford, CA: Stanford University Press, 2005.

- Constable, Marianne. Just Silences: The Limits and Possibilities of Modern Law. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007.

- Hanks, William F. Converting Worlds: Maya in the Age of the Cross. Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1525/california/9780520257702.001.0001.

- Kabua, Jibā B. “We are the Land, the Land is Us: The Moral Responsibility of Our Education and Sustainability,” in Life in the Republic of the Marshall Islands: Mour ilo republic eo an majõl, ed. Anono Lieom Loeak, Veronica C. Kiluwe, and Linda Crowl. Majuro, Marshall Islands: University of the South Pacific Centre and Suva, Fiji: Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific, 2004), 180-191.

- Kelin II, Daniel A., ed. Marshall Islands: Legends and Stories. Honolulu: Bess Press, 2003.

- Kunreuther, Laura. Voicing Subjects: Public Intimacy and Mediation in Kathmandu. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014.

- Lang, Sharlynn. Telephone interview with the author. February 2014.

- ———. Telephone interview with the author. Drawings facilitated by April Brown. Springdale, Arkansas, October 28, 2014.

- Laukon Jibas, Faith. Interview with the author. Springdale, Arkansas, September 21, 2013.

- ———. Interview with April Brown. Springdale, Arkansas, October 29, 2014.

- Laukon, Neisen. Interview with the author. Springdale, Arkansas, October 8, 2014.

- Leslie, Esther. Walter Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism. London and Sterling, Virginia: Pluto Press, 2000.

- Marshallese Oral History Project and Digital Music Archive. Marshallese Educational Initiative. www.meius.org

- McArthur, Phillip H. “Narrative, Cosmos, and Nation: Intertextuality and Power in the Marshall Islands,” Journal of American Folklore, vol. 117, no. 463 (2004): 55-80. http://dx.doi.org/10.1353/jaf.2004.0018.

- Moore, W. Robert. “Our New Military Wards, the Marshalls,” National Geographic Magazine, September 1945.

- Morton, Timothy. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013.

- Ochoa Gautier, Ana María. Aurality: Listening in Nineteenth-Century Colombia. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014.

- Rancière, Jacques. The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill. New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004.

- “The RMI 2011 Census of Population and Housing Summary and Highlights Only,” Majuro: RMI Office of the President, 2012.

- Spennemann, Dirk H. R., Downing, Jane, and Bennett, Margaret. eds. Bwebwenattoon Etto: A Collection of Marshallese Legends and Traditions. Majuro, Marshall Islands: Historic Preservation Office, 1992.

- Tobin, Jack A. Stories from the Marshall Islands: Bwebwenato Jān Aelōn̄ Kein. Honolulu: University of Hawai’i Press, 2002.

- US Census Bureau, Census 2000 Gateway. www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html. Accessed December 16, 2014.

- Weidman, Amanda. Singing the Classical, Voicing the Modern: The Postcolonial Politics of Music in South India. Durham: Duke University Press, 2006. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9780822388050.

- Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation. A Profile of Immigrants in Arkansas. Little Rock, AR: Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, 2007.

Notes

I explore the biopolitical and terrapolitical vocalic dissonances in Radiation Sounds: Marshallese Music and Nuclear Silences (in progress).

Adriana Cavarero, For More than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression, trans. Paul A. Kottman (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 2005); Jacques Rancière, The Politics of Aesthetics: The Distribution of the Sensible, trans. Gabriel Rockhill (New York: Continuum International Publishing Group, 2004); Laura Kunreuther, Voicing Subjects: Public Intimacy and Mediation in Kathmandu (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2014); Amanda Weidman, Singing the Classical, Voicing the Modern: The Postcolonial Politics of Music in South India (Durham: Duke University Press, 2006).

My work is inspired by rhetorician Marianne Constable’s work on reading between the lines of positivist modern law and trying to hear the unsaid (justice). I am interested in the multimodal, musico-representational readings that help us bring disciplinary limitations to the fore. See Marianne Constable, Just Silences: The Limits and Possibilities of Modern Law (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2007). Also, Ana María Ochoa Gautier, Aurality: Listening in Nineteenth-Century Colombia (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2014) offers modes of intertextual reading against the silence of the colonial archive. The text presents a critique of “oral tradition” as the depreciated “other” of the written tradition. I aim to keep this beneficial critique in mind as I explore non-literary ways of understanding the pursuit of nuclear justice and restoration.

In For More Than One Voice: Toward a Philosophy of Vocal Expression (2005), Cavarero discusses a "vocal ontology of uniqueness" where voice sounds "singular beings who invoke one another contextually" (173). I want to extend this notion of the vocal ontology to think politics in and of the land/lineage, that voice connects mouths and “ears,” as Cavarero writes, and also the transcorporeality of the social individual. I use the term “transcorporeal” following Stacy Alaimo in Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self (Bloomington, IN: Indiana University Press, 2010).

Esther Leslie, Walter Benjamin: Overpowering Conformism (London and Sterling, Virginia: Pluto Press, 2000), 41.

Oral histories and modern political narratives have been discussed by Philip H. McArthur in his article, “Narrative, Cosmos, and Nation: Intertextuality and Power in the Marshall Islands,” in the Journal of American Folklore (2004). Others, like Jack Tobin in Stories from the Marshall Islands: Bwebwenato Jān Aelō Kein (2002), Daniel Kelin’s edited collection, Marshall Islands: Legends and Stories (2003), and Dirk H. R. Spennemann’s Bwebwenattoon Etto: A Collection of Marshallese Legends and Traditions (1992) discuss folklore and oral history, but not within the context of the role of voice and pedagogy.

Accurate statistical data for the number of Marshallese who reside in northwest Arkansas (and likely the US as a whole) is elusive. US Census figures in 2010 placed the number of Marshallese in Springdale at 4,300, but that number is widely believed to be underreported by RMI officials and local NGOs. See Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, A Profile of Immigrants in Arkansas (Little Rock, AR: Winthrop Rockefeller Foundation, 2007); US Census Bureau, Census 2000 Gateway, December 16, 2014, www.census.gov/main/www/cen2000.html. RMI figures are from “The RMI 2011 Census of Population and Housing Summary and Highlights Only,” Majuro: RMI Office of the President, 2012.

Jibā B. Kabua, “We are the Land, the Land is Us: The Moral Responsibility of Our Education and Sustainability,” in Life in the Republic of the Marshall Islands: Mour ilo republic eo an majõl, ed. Anono Lieom Loeak, Veronica C. Kiluwe, and Linda Crowl (Majuro, Marshall Islands: University of the South Pacific Centre and Institute of Pacific Studies, University of the South Pacific , 2004), 190.

Collection for the MOHP and Digital Music Archive is ongoing. To view content visit http://www.meius.org.

William F. Hanks, Converting Worlds: Maya in the Age of the Cross (Berkeley, Los Angeles, London: University of California Press, 2010).

Robert. W. Moore, “Our New Military Wards, the Marshalls,” The National Geographic Magazine, (September 1945): 334.

Benetick Kabua Maddison, “Oral Histories of the Marshallese Diaspora: Translation as Cultural Conversation,” August 2015.

Stacy Alaimo, Bodily Natures: Science, Environment, and the Material Self (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2010).

The memorial event is held every year on March 1, which is the anniversary of the largest thermonuclear test the United States ever conducted, Castle Bravo (“Bravo”). Bravo, which at 15 megatons was 1,000 times the force of the bomb dropped on Hiromshima, unleashed radioactive fallout throughout the atolls, and its debris was most concentrated on Bikini Atoll and the populated atolls of Rongelap, Utrōk, and Ailingnae.

Faith Laukon Jibas, September 21, 2013, Springdale, Arkansas.

Sharlynn Lang, telephone interview with the author, February 2014.

Sharlynn Lang, telephone interview with the author, drawings facilitated by April Brown, October 28, 2014.

Timothy Morton. Hyperobjects: Philosophy and Ecology after the End of the World (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2013).