Exilic Suffering: Music, Nation, and Protestantism in Cold War South Korea

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

In Cold War South Korea, the unmarked term “music” (eumak) came to signify Western classical music, and a host of ambiguous terms, including “folk music” (minsogeumak), “traditional music” (jeontongeumak), “indigenous music” (hyangtoeumak), and “national music” (gugak), emerged to categorize traditional practices that were rapidly disappearing from everyday cultural terrain. This West-centric development in musical culture has been euphemistically called “cosmopolitanism,” and in some cases, considered an index of national progress in the “race to modernization.” This paper attempts a critical reckoning of a specifically Cold-War form of cosmopolitanism by examining musicians who were at the center of this mid-century development: Christian Korean composers who left the North to flee the persecution of Christians by communist officials between 1945 (Korea’s independence from Japan) and 1953 (the end of the Korean War). I argue that the exiled composers were strategically positioned to construct secular and sacred music practices that reinforced the official cultural policy of the nascent U.S.-South Korea coalition. This exilic cultural work involved not just reconciling anticommunist nationalism with Western music idioms but also a related project of discouraging alternative conceptions of national (and nationally important) music. I first investigate how Christian exiles became the poetic voice of Cold War official culture through their elevated status in this culture’s institutions and narratives. Secondly, I consider the politics of this official culture, examining the music styles, genres, and compositions that were promoted or repressed. As I will show, Cold War music culture in South Korea was shaped by a confluence of mid-century international and intra-national politics, and Christian exiled composers were situated at the convergence of these mid-century concerns.

Kim Tu-wan’s choral work “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane” (Heading for the Homeland) portrays the suffering and the eventual redemption of “sulleja”—a pilgrim.[1] Composed in South Korea after the Korean War (1950–1953), this choral piece relies on conventions of Western common practice music to convey the narrative components of an idealized pilgrimage: the pilgrim’s dispossession, crisis, suffering, and redemption. In the beginning of the piece, a subdued choral texture in a minor key evokes the pilgrim’s lonely journey; a chromatic contrapuntal passage in the middle depicts a “violent storm” inflicted upon the despondent subject; and finally, a declamatory style in a major key proclaims the divine intervention that delivers the subject from distress. “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane” was a noteworthy addition to a mid-century South Korean Protestant choral repertory preoccupied with pilgrimage and the related themes of religious exile, persecution, and martyrdom. Many of these pieces, which predominantly emerged after the period of the Korean War, were written by composers who were themselves exiles of a kind in South Korea. They were new settlers who left the northern part of Korea (formally referred to as the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea or North Korea after 1948) sometime between 1945 and 1953 to avoid or flee persecution of Christians and landowners by communist officials. By dramatizing the suffering and the subsequent redemption of a displaced person, the Protestant choral repertory in the 1960s and 1970s directed the imagination of the congregations in the southern part of the Korean peninsula toward the violence inflicted on legions of religious-political refugees who had recently crossed the north-south border. The mid-century clergy in the south, who would deliver their sermons alongside performances of pieces like “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane,” reinforced this imagination as they communicated their admiration for the exiles and advertised their grievances from the pulpit. Christians’ suffering in North Korea, they argued, was an exemplar of authentic Christian faith.[2]

Through theological liturgy and staged performances of choral pieces like “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane,” Protestant churches established themselves as some of the most compelling Cold War institutions in South Korea during the 1950s and 1960s. Critical studies of Cold War South Korea have tended to gloss over the role of mid-century Protestant cultural practices, including staged vocal music practice, in enabling the state’s cultural politics. Yet, a closer examination demonstrates intimate connections between this religious music practice and the state’s two-pronged cultural agenda of Western-centrism and anticommunism. Exiled Christian composers, as both victims of Cold War tragedy and trained practitioners of Western music, facilitated these connections more effectively than any other cultural figures. Exiled Christian composers were front-line casualties of the Cold War drama that began to consume all aspects of life in Korea in the months after Korea gained independence from Japan in August 1945. Beginning in the winter of 1945, it was becoming clear to Christians in the northern part of Korea that Christianity would not be tolerated by the rising communist regime in the north: People’s committees soon began to harass Christians locally, and Workers’ Party officials initiated large-scale persecutions, including the Soviet-aided siege of five thousand Christian youths in Sinŭiju in November 1945.[3] Alarmed by these incidents, Christian Koreans began to leave P‘yŏngyang, a city that had been touted as “the Jerusalem of Asia” during the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945) by U.S. missionaries in Korea, and other areas in what is now North Korea.[4] Estimates of the number of southbound (wŏllam) refugees vary considerably, ranging from two to three hundred thousand people on the low end to as many as six hundred thousand or even two million people on the high end.[5] Galvanized by direct and indirect experiences of the communists’ hostilities, wŏllam Christians helped the emerging political elites in the south to precipitate the “hot” events of the Cold War after settling in the south between 1945 and 1953. These events include the southern elites’ aggressive alignment with the U.S. upon Korea’s liberation from Japanese occupation (1945); their early push for the establishment of separate governments in 1948 (an action disapproved by centrists across Korea at the time); the disappearance of centrists through ideological re-education or assassination; the persecution of socialists and dissidents, which led to their deaths or northbound exile between 1945 and 1953; militarization of society before and during the Korean War; and the reinforcement of an anticommunist public culture during the post-Korean War decades (see Table 1 for a summary of key Cold War events in Korea).[6]

In this article, I examine the politics and works of exiled Christian composers in South Korea during the high Cold War years (1945–1960s), tracing their alignment with the emerging alliance of pro-U.S. South Korean political elites and the U.S. military government in Korea. I argue that the exiled composers were strategically positioned to construct secular and sacred music practices that reinforced the official culture of this nascent alliance. This exilic cultural work involved not just reconciling anticommunist nationalism with Western music idioms but also a related project of discouraging alternative conceptions of national and nationally important music. I first investigate how Christian exiles became the poetic voice of official Cold War culture through their elevated status in this culture’s institutions and narratives. Secondly, I consider the politics of this official culture, examining the music styles, genres, and compositions that were promoted or repressed.

| Year | Key events |

|---|---|

| August, 1945 |

|

| September, 1945 |

|

| 1946 – 1948 |

|

| August, 1948 |

|

| August, 1948 – June, 1950 |

|

| June, 1950 – July, 1953 |

|

| 1953 – ate 1980s |

|

In exploring the materiality of Cold War culture in South Korea through a critical examination of exiled religious composers, this article highlights and builds on the works of South Korean musicologists associated with a post-Cold War project of reconsidering the musical life of Korea from 1945 through the anticommunist decades of the 1950s, 1960s, and 1970s. Their works may be considered an intellectual project that, since the late-1980s, advocated for critical reflections on hegemonic Cold War formations in South Korea, which were largely unrecognizable as such during the previous decades. Generally speaking, post-Cold War approaches in South Korean musicology have been inspired by the concerned musicologists’ rediscovery of composers, critics, and musicians associated with the Korea Musicians’ Coalition (hereafter KMC), a socialist music organization founded in Seoul upon independence from Japan (1945) and blacklisted by the rising pro-U.S. political elites in 1947.[7] The works of KMC figures, after more than thirty years of being declared off limits, were made available in 1988 through the July 7 Presidential Declaration, in turn prompted by the democratization movement that swept South Korea in the 1980s.[8] The newly recovered sources involving the KMC figures, some of whom fled to the north sometime between 1945 and 1950, reveal cultural visions that proliferated in the southern part of post-liberation Korea but that were soon repressed through mechanisms of anticommunist purge. Most importantly, some of the KMC and KMC-aligned musicians considered the question of what it is to be “Korean” in and through music an urgently important one in the postcolony and linked this question to a larger contemporary debate on the relationship between music, ideology, and politics. For instance, No Kwang-uk, a lyricist and a KMC member, stated in 1949 that for the purpose of building a Korean music culture, “it is not necessary to eliminate what is Western but ... to reflect on the fact that no one found it paradoxical that Western music could be inherited as Korean people’s music.”[9] Kim Sun-nam, a leading composer of the KMC, recommended to the readers of his 1945 article that they remain skeptical toward “those artists who privilege ideology to the exclusion of musical techniques as well as those who have withdrawn from ideology” and maintained that “music cannot be separated from ideology, ethnic people [minjok], and class.”[10] Such views distinguished the KMC musicians from many of the pro-establishment ones, who supported (and were expected to support) art’s autonomy from ideology and politics.

In part inspired by the recovered artists’ writings on the ineluctably social dimensions of music, post-Cold War developments in South Korean music scholarship have called for a degree of self-reflexivity in understanding the cultivation of Western classical music in twentieth-century South Korea.[11] Scholars including Yi Kang-suk, Yi Kŏn-yong, No Tong-ŭn, Cho Sŏn-u, and Min Kyŏng-ch‘an have highlighted the need for interrogating the universalist embrace of Western music as well as the notion of “purity of art music” [sunsu yesul juŭi] underlying this universalism.[12] For instance, No Tong-ŭn stated in the foreword to his 1992 book that a theory of (Korean) ethnic music [minjok ŭmak ron] should ask “why it is that the way we [South Koreans] see, listen to, and think has been articulated through the texts of the West.”[13] Similarly, in a 2006 monograph, Min Kyung-ch‘an asks “why school education [in South Korea] has been Western-centric, why the music that everyday people were exposed to has been Western music, and why [South Koreans] came to love and excel at Western music even more than people in the West.”[14] Min contends that such Western-centric cultural developments have all too often assumed a depoliticized, nonhistoricized perspective—for example, explaining these trends as an “index” of South Korea’s progress in the “race to modernization”—and states that it is necessary to acknowledge South Korean musical “cosmopolitanism” as a specifically Cold War form of cosmopolitanism.[15]

Indeed, terminologies used in the official discourses of Cold War South Korea have trafficked in the universalist cultural aspirations rooted in Cold War cosmopolitanism: the unmarked word “music” (ŭmak) came to signify Western music, and a host of ambiguous terms emerged to denote precolonial shamanist and Neo-Confucian performance cultures whose presence was declining in the everyday life of many South Koreans. These terms include “folk music” (minsok ŭmak), “Korean music” (han’guk ŭmak), “traditional music” (chŏnt‘ong ŭmak), “indigenous music” (hyangt‘o ŭmak), “our music” (uri ŭmak), “national music” (kugak), and “past music” (yet ŭmak). To be sure, traditional music of Korea did not “disappear,” but rather it withdrew from quotidian life via a number of mechanisms. Notably, identification with Western and Western-style music came to be one of the terms of cultural acceptability for the growing South Korean middle class in an urbanizing context.[16] Just as important was the South Korean state’s efforts to preserve traditional Korean music through the Intangible Cultural Properties system (since 1962), which contributed to the museumization of traditional music.[17] As Namhee Lee, historian of modern South Korea, suggests, the objective of the state-directed project of preservation may have never been to reassert traditional music in a living context but rather to affirm Koreans as moderns by folding certain cultural practices into a temporal space called “the past”: “the official designation of folk culture as national tradition formalized and displaced the lived experience of the past as an artifact and at the same time highlighted contemporary Korea’s transformation from the past.”[18]

This article seeks to contribute to the critical literature on South Korea’s Cold War cultural politics by looking at Christian exiled composers, who were instrumental in establishing the foundation of South Korea’s secular music culture in the wake of Cold War tensions. Some of these religious composers are discussed in the aforementioned works published in Seoul given their prominence in secular music scenes. Yet, to date, there have been no critical studies, either in Korean- or English-language scholarship, that situate these composers as a group with shared experiences, views, and politics in the context of midcentury Korea, in part because of the distance between religious and secular scholarship.[19] A critical examination of the exiled Christian composers highlights the political conditions that shaped South Korea’s Western-centric cultural orientation at the moment of its formation, demonstrating its instrumentality in (re)aligning Third World elites with the First World. This article therefore emphasizes the neocolonial nature of midcentury music production in South Korea without losing sight of the humanity of the composers whose poetic compositions were shaped by their lived experiences of Cold War tragedies. As I will show, Cold War music culture in South Korea was shaped by a confluence of midcentury international and intra-national politics, and exiled Christian composers were situated at the convergence of these midcentury concerns.

Cold War Institutions and Narratives

A number of recent works on South Korea’s Cold War culture have shed new light on the cultural agenda of the pro-U.S. political faction that emerged as a ruling group in Seoul a few weeks after Korea’s national independence from Japan in September 1945. In particular, they have shown that a specific set of cultural objectives was implemented to reinforce a pro-West, pro-U.S. stance against the backdrop of intensifying ideological conflicts between pro-capitalist, U.S.-aligned groups (concentrated in the south) and pro-communist, Soviet-aligned factions (concentrated in the north). The pronounced role of Korean Christians—and increasingly, exiled Christians—in this cultural reinvention is rarely recognized in these recent studies, yet their prominence is not surprising when we consider the trajectory of Syngman Rhee (1875–1965), the first South Korean president who played an instrumental role in reshaping official cultures according to Cold War imperatives. The U.S.-appointed head of the Korean government in 1945, Rhee exemplified the strand of elite Christian nationalism that had looked to the West—in particular, the U.S.—as the moral, cultural, and political savior of Korea during the Japanese colonial period (1910–1945).[20] Indeed, no other Korean national touted more religious and political connections to the U.S. than Rhee at the time when the United States Army Military Government in Korea (1945–1948, USAMGIK) was actively searching for a leader of an allied Korean government in 1945; and crucially, Rhee had been able to build these connections via transnational Protestant networks that extended back to the late nineteenth century. Rhee had been a prominent member of the Independence Club, a turn-of-the-century anti-Japan, pro-U.S. organization that a number of U.S. Protestant missionaries helped found in Seoul; was a graduate of a missionary-established school in Seoul (Pai Chai School, 1895); worked as an active translator for U.S. missionaries stationed in Seoul; was the first Korean national to obtain a doctoral degree from Princeton University (1910); and served as the missionary-appointed Korean representative to the World Methodist Council held in the U.S. in 1912.[21] For most of Korea’s colonial period (1910–1945), he lived in the U.S., devoted to the cause of uniting the U.S. and colonial Korea against Japanese imperialism. To further this aim, in 1919 he founded a “West/U.S. Committee” (Kumi wiwŏnhoe) in Washington, D.C., through which he lobbied the State Department for Korea’s independence from Japan.[22]

The targeted U.S. politicians did not always welcome such efforts, but this work brought Rhee to the State Department’s attention and identified him as the best candidate to act as the figurehead of a U.S.–Korea alliance in 1945: a Korean national who had been vetted by U.S. missionaries and proved himself to be passionately pro-U.S.[23] To top it off, Rhee was known to harbor staunchly anticommunist sentiments; for example, he had worked tirelessly to jettison communist elements from the Korean nationalist movement in the Korean community in San Francisco (1910s–1920s).[24] And his personal history of anti-Japanese endeavors would have been perceived as an advantage as well: one of the first lessons that the U.S. military government learned in Seoul in the winter of 1945 was that Korean elites who had formerly collaborated with the Japanese colonial government were unpopular with the masses.[25] This did not stop the U.S. authorities from reinstating a large number of colonial-period collaborators in power, but it seems that they knew better than to place one as the state’s figurehead.

The kinds of music projects that were allowed to thrive under the joint leadership of Syngman Rhee and the U.S. military government demonstrate a desire to fill the cultural vacuum created by the end of colonial rule with a depoliticized Western-centric music. Christian Koreans were able to capitalize upon this vulnerable cultural environment not only because Rhee and the U.S. military government were favorably disposed to Christians, but also because most of the Korean musicians who were experienced in Western music in 1945 were Christians. Generally speaking, church music activities during the colonial period (1910–1945) were not limited to faith-oriented music such as hymns and choral singing but also involved advanced music lessons in keyboard performance, conducting, and music theory.[26] In fact, churches and church-affiliated organizations, especially those located in P‘yŏngyang and Seoul, were the centers of Western music. As recent studies of colonial-period Korean Christianity show, the appeal of American Protestant missionizing (1880s–1930s) for many Korean converts was in its role in transmitting components of Western culture, including music, English language education, Western medicine, and technology.[27] In this context, many female missionaries and male missionaries’ wives provided keyboard lessons in the churches, and missionary-led youth associations held concerts of Western classical music. Typically, Korean church musicians studied keyboard playing with missionaries’ wives as children, listened to performances of pieces like Haydn’s Creation and Handel’s Messiah as teenagers, and had their first public experiences of conducting and performing as they reached adulthood.[28] Sometimes they also used the network of churches, Christian schools, and missionary associations as a springboard towards music studies outside Korea. They consulted missionaries for advice on this subject, and a few managed to obtain sponsorship from American Protestant groups for music studies in the U.S. Reflecting this history, most Koreans who attained bachelor’s or master’s degrees in Western music in Japan or the U.S. (or in rare cases Germany) before 1945 were first trained within a network of Protestant institutions either in P‘yŏngyang or Seoul.[29]

Thus, in 1945 the U.S. military government and Koreans associated with it called upon distinguished Christian musicians to establish the official Korean music culture, in addition to maintaining the musical life of Protestant churches. Before the north-to-south exile began in earnest during the winter of 1945, Christian musicians in Seoul were placed in charge of major music projects. The most important among these was the foundation of the Koryŏ Kyohyang-ak Hyŏphoe (Korea Symphonic Association; hereafter KSA). It was founded in September of 1946 with the support of the U.S. military government in Korea and under the direction of Hyŏn Che-myŏng (1902–1960). Hyŏn, a Seoul-based Christian and the first Korean to study theology and music in Chicago (1920s), was an ideal candidate for an organization whose membership was predicated on personal avowals of right-of-center positions or political neutrality. Indeed, ideological affiliation was how Hyŏn was able to enlist the regime’s endorsement despite his lack of popularity with many Koreans. His infamously prominent roles within colonial music organizations during the Japanese occupation—for example, his leadership role in the pro-Japanese music association Chosŏn Ŭmaka Hyŏphoe (Chosŏn Musicians’ Association)—subjected him to public recrimination in the wake of independence next to other public figures with a similar personal history, yet he was able to associate himself with the emerging U.S.–South Korea regime by exploiting his pro-U.S. credentials—credentials that the U.S. military government welcomed over all others—and by playing a role in the campaigns for the temporary U.S. occupation of Korea.[30] In addition to directing the KSA, Hyŏn Che-myŏng founded an affiliate organization called the Taehan Ŭmaka Hyŏphoe (Korea Musicians’ Association; hereafter KMA), using more or less the same resources and personnel of the colonial-period Chosŏn Musicians’ Association.[31]

Exiled composers, conductors, and musicians began to share key institutional positions with Seoul-based Christians and, to some degree, replace these early partners of the U.S. military government and Syngman Rhee as they gradually reached the south after 1945 (this pattern would continue into Syngman Rhee’s presidency, 1948–1960).[32] In part, the émigré composers were able to emerge as dominant players in the secular and religious music scenes because they were some of the most skilled Korean musicians of Western music in Korea. P‘yŏngyang had been the capital of Korean Christian conductors and composers during the colonial period. Christian men went to P‘yŏngyang’s theology schools beginning in the 1910s if they wished to study Western music seriously, as there were very few other options in Korea.[33] Missionary teachers had established a college-level music department in Seoul in 1925, but this was part of a women’s school that did not accept male students and that focused on keyboard lessons, following the typically gendered conventions of Western music practice. In P‘yŏngyang, young Christian men could study with American teachers who specialized in this music and with members of a small group of Koreans who began returning from music studies in the U.S. in the 1930s.[34] Thus, P‘yŏngyang-educated male musicians, due to their strong training in Western music, limited records of their colonial-period affiliations, and their prior social ties to U.S. nationals, were perceived as ideal candidates to populate the official music culture in the south.

Reflecting this transfer of power, the leadership of the KMA was transferred from Hyŏn Che-myŏng to Yi Yu-sŏn (1911–2005), an exile, when the association’s identity was refashioned in 1962.[35] The exiled composers also established new music associations to advance their shared interests, mirroring a widespread trend among the broader exiled community during this time of displacement and resettlement. These included the Han’guk Kyohoe Ŭmaka Hyŏphoe (Korea Church Music Association, 1952), which quickly became the backbone of the official music culture, along with the KMA.

In addition to having the requisite musical skills and social connections, the émigré composers shared a hostile disposition towards communism, an attitude that characterized the Christian exiles at large. As discussed briefly in the introduction, the exiles’ firsthand experience of the communists’ hostilities made them ideal candidates for enforcing the administration’s anticommunist cultural politics. Indeed, anticommunism was a point of convergence for South Korea’s political elites and Christian exiles throughout the post-1945 period. As the Christian theologian and sociologist Kang In-ch‘ŏl shows in a comprehensive study of Protestant political activism in Cold War Korea, the exiles breathed life into the elites’ official doctrine of anticommunism because they were considered “living proof” of communist violence. In exchange, exiles were able to secure important positions in and outside the churches, alleviating their personal displacement.[36] Often, the exiles’ political activism in the south involved leadership roles in military and paramilitary organizations that terrorized socialists and other dissidents of the administration. One such organization in which Christian exiles constituted an overrepresented group was the Sŏbuk yŏnmaeng (West–North Alliance), a rightist group notorious for attacking socialist groups in the south beginning in 1947.[37]

A more subtle form of exile-centric political activism involved the reproduction of a discourse of victimization that was based upon narratives of communist persecution and testimonies of Christian martyrdom. As Kang documents in his 600-page monograph, such narratives shaped and inspired music, sermons, radio shows, plays, and commemorative Christian services for an ever-increasing canon of Christian martyrs in the North that was avowed and constructed by the exiles. This politico-religious discourse of victimization, one that came to be identified as the “authentic Korean Protestant experience,” was promoted in national secular media as well as churches, enacting a messy interpenetration of nationalism, anticommunism, and religion.[38] Narratives of Christians’ suffering fueled the idea that it was communist aggression that “forced” the establishment of South Korea. Conversely, civil conflicts were interpreted as religious events. In particular, the Korean War (1950–1953) was likened to “stigmata through which God assigned a special calling to the Korean people,” and the exiles were idealized as “individuals with a special calling.”[39] Throughout the 1950s and the 1960s, exiles thus became popular figures in the secular and sacred cultures, with political and religious organizations competing to recruit (to “claim,” in Kang In-chŏl’s expression) exiled clergymen and musicians.

Indeed, reading sources on the émigré composers is a fraught exercise because the composers are often represented through the hagiographic terms associated with Cold War narratives. This difficulty is particularly true of exiles’ biographies in Christian literature, much of which continues to privilege these narratives. Kim Kyu-hyŏn’s Kyohoe ŭmak chakgokka ŭi segye (The World of Korean Church Music Composers), an anthology published in Seoul in 2006 based on extensive interviews of seventeen male Christian composers in South Korea, exemplifies the protracted afterlife of exilic Cold War discourse.[40] The selection of composers itself indexes and reinscribes the focus on exiles in South Korean Protestant culture—that is, its tendency to consider Christian exiles from the North and their experiences as the authentic voices and experiences of this culture: of the seventeen composers, twelve are self-identified exiles from the North. Reflecting this selection, the text of the anthology is suffused with portrayals of exilic experiences, including life in P‘yŏngyang and other parts of North Korea before 1945, personal encounters with North Korean communists’ hostilities towards Christians, and dramatic arrivals in the South. Indeed, chapters on exiled composers follow a general narrative structure that commences with a poignant account of their pre-exile experiences of victimization and ends with a celebratory description of their successful careers in various domains of sacred and secular music in South Korea.

The paths of the émigré composers leading up to their settlement in the south are usually narrated as formative, distressing, and religious experiences, unfolding as either a detailed documentation of dreadful historical incidents or a more nebulous, tender recollection. At one end of the spectrum are composers like Kim Kuk-jin (1930–), who recounts his run-in with the communist officials in P‘yŏngyang in striking detail. Based on the interview with this composer, Kim Kyu-hyŏn writes:

As soon as Kim received his diploma from the soon-to-be-disbanded Sŏnghwa Theology School [in P‘yŏngyang] in January 1950, he fled to Kungnyŏng Mountain, which was close to his family’s house. He shut himself up in the depth of the mountain, and composed there ... This hiding had to end soon: Kim’s father wanted him to come home. His father ordered Kim to take refuge in an underground tunnel that he dug beneath the cowshed. Kim was nineteen at this time. Inside the tunnel, he spent every day composing Christmas cantatas and hymns. One day, feeling stifled by the stale air, he ventured outside and tried composing on his desk, only to find [the Workers’ Party] officials raiding his house. Kim was sure that he was going to die, but one of them saw that he was a composer. The official invited him to join the People’s Committee, saying that the People’s Republic needs people like Kim. As soon as the officials left, Kim ran to Kungnyŏng Mountain. Everyone who was taken into the officials’ custody was killed, but because he composed, he was able to survive. He still believes that it was God who protected and saved him.[41]

Most of the other narrations of persecution in the anthology are less vivid than Kim Kuk-jin’s, but they communicate a similar traumatic ethos and Christian interpretations of personally experienced political events. For example, the chapter on Pak Chae-hun (1922–) states that Pak fled P‘yŏngyang “during Easter week of 1946 because conditions proved to be impossible.”[42] Another composer, Ku Tu-hoe (1921–) decided not to return to P‘yŏngyang while visiting his family in Seoul in 1945 because his brother “entreated him not to go, in tears”; and at the end of a long journey involving a series of southbound migrations, he “received the good fortune of a scholarship given by the Crusade Foundation of the U.S. Methodist Church.”[43]

Another emotional cornerstone of the exilic narrative is the experience of deprivation caused by the Cold War tragedies. For Paek T‘ae-hyŏn (1927–), a pastor’s son who left behind an active conducting career in P‘yŏngyang in 1946, the civil conflicts resulted in the loss of contact with his father. Kim Kyu-hyŏn recounts that when the Korean War broke out soon after his family’s arrival in the South, “Paek T‘ae-hyŏn was not able to find his father, who was kidnapped by the North Korean communists.”[44] In the lives of most exiled composers, however, the experience of loss involved the loss of the Christian north, especially music life in Christian north, which is conveyed through recollections of musical encounters in churches in P‘yŏngyang or other northern areas. For example, the chapter on Yi Chung-hwa (1940–) opens with the portrayal of a happy, Christian, and affluent family in Hwanghae-do, a northwestern province, and Yi’s childhood experience of learning music in churches by “listening to his sister’s performance on the organ” and “listening to children’s songs and art songs through the gramophone.”[45] Similarly, the chapter on Ku Tu-hoe begins with an exposition of his musical encounter in Namsanhyŏn Church, a church that has long been commemorated by the exiles as one of the spiritual centers of P‘yŏngyang. This chapter’s first sentence states, “Ku Tu-hoe confessed to me that he could not fall asleep the day he listened to F. J. Haydn’s The Creation, conducted by Yi Yu-sun [another soon-to-be exiled musician] at Namsanhyŏn Church, for he was moved and shocked uncontrollably.”[46] Such poignant commemoration projects a sense of loss onto the once thriving (but now forsaken) Christian music life in the North and casts the act of leaving this scene as a haunting experience.

With such exilic narratives densely written into its text, Kyohoe ŭmak chakgokka ŭi segye (The World of Korean Church Music Composers)—like other Christian literature commemorating similar narratives—is both a testament and tribute to personally experienced Cold War tragedies. In other words, if read critically, the anthology unveils not only Korean Cold War history but also the emotional fabric of Cold War-period Protestantism in South Korea, which has informed the way many South Koreans have affectively understood their place in the world. Acknowledging the distinction between exile experience and exile-centricity allows us to see the émigré composers as both victims of the Cold War and enablers of the post-1945 cultural politics in the South. It is outside the scope of this article to explore how their status as exiles helped to link all of the twelve émigré composers featured in Kim’s anthology with the official institutions of the Cold War South. But a brief look at the similarities between their post-exile career trajectories—trajectories that are not shared with non-exile composers in the anthology—illustrates the dynamics of the convergences between these composers and the official culture.[47]

To begin, almost all émigré composers came to be involved in the music organizations that formed at the intersection of transnational Protestantism and Cold War militarization either as choir conductors or advanced music students. Such organizations included military bands, Christian choirs associated with the U.S.-South Korea armed forces, and orphaned children’s choirs that performed “appreciation concerts” for U.S. military servicemen.[48] All of these organizations emerged as the South Korean state armed itself in the immediate prewar years and as it waged the Korean War, and they were the only places in South Korea where men could learn Western music from 1948 to 1953.[49] Some émigré composers also became conductors of prestigious churches that were aligned with such military-musical organizations. One example was the multi-branch Yŏng’nak Church, which became a leading religious organization in South Korea and for the (South) Korean diaspora due to the popularity of its clergyman, Kyung-Chik Han (1902–2000), who had experienced persecution at the hands of the Workers’ Party officials in P‘yŏngyang and reached the South against extraordinary odds.[50] Churches like Yŏng’nak Presbyterian Church often served as the contact points of exiled Christian musicians, U.S. military personnel stationed in South Korea, U.S. relief medical workers, and U.S. missionaries who were returning to Korea after a brief residence on the eastern side of the Pacific during the Second World War. For an account of the dramatic yet seamless convergence of the exiled composers and these institutions, we can turn again to Kim Kuk-jin’s experience:

Kim moved to the South with the guidance of Reverend Kim Chae-gyŏng during the January Fourth Retreat [1951]. Although he was suffering from tuberculosis, he was recruited into the army. Thankfully, this unit was part of the U.S. armed forces, and so he was able to recover his health. Life after this service was a turning point: he met his composition teacher Malsberry, an American of German ancestry ... This happened during the period when he was conducting the choir of Onch‘ŏnjang Church in Pusan [a southern city in Korea] and living with the director of the Public Relief Hospital. Kim had his church choir perform his own Christmas cantata during the church’s Christmas service, and his work impressed the reverend. The reverend took Kim’s cantata to Malsberry, who was working in Pusan as a missionary. This initiated a teacher-student relationship. Malsberry was previously a music professor at P‘yŏngyang’s Sungsil School, but he returned to the U.S. when the Pacific War broke out. In his home country, he studied theology and came back to Pusan [after the war] as a missionary.[51]

As this passage suggests, Kim Kuk-jin’s position as an exiled Protestant placed him on a path that led to the U.S. armed forces, healthcare, a conductorship in a church, and eventually, an American composition teacher. Similar stories throughout the anthology show that militarized Protestant music institutions were the very routes through which the exiled composers “arrived” in the South. For example, Pak Chae-hun (1922–) was able to meet his artistic collaborators and improve his composition skills through his simultaneous involvement in the Yŏng’nak Church choir, the Marine choir, and the Korea Church Music Association.[52] For a younger exiled composer like Kim Sun-se (1931–), serving as a French horn player in the Republic of Korea Symphonic Band (which later became the National Symphonic Band) during the Korean War gave him the opportunity to play music in six countries in Southeast Asia and to “experience musical professionalism and mysterious music cultures ... that laid down the foundation of his career as a composer.”[53]

Based on the networks that developed in these military-religious music organizations, the exiled composers followed a similar career path that included obtaining an advanced degree in music and/or theology in South Korea or the U.S., becoming music professors in secular or Christian universities in major South Korean cities, conducting choirs of prestigious churches, and composing secular and Protestant music (see Appendix). Several of them (for example, Yi Yu-sŏn and Ku Tu-hoe) also received national accolades from the government for secular symphonic and vocal compositions. Temporary or permanent migration to Los Angeles beginning around the 1970s is another path shared by the exiled composers (six out of the twelve). Ku Tu-hoe and Kim Tu-wan studied music and theology in Christian seminaries in schools in the Los Angeles area, such as Linda Vista Seminary, Yuin University, and Bethesda University, all of which have been popular destinations for Protestant students of Korean nationality. Yi Yu-sŏn, Kim Sun-se, Paek Kyŏng-hwan, and Pak Chae-hun chose to live in Los Angeles in addition to pursuing advanced studies at such schools. This common path demonstrates the specific U.S.-centric orientation common to the exiles and locates Los Angeles itself as part of South Korea’s Cold War culture.[54] Already during the colonial period, migration to the U.S. West Coast had intrigued the Korean Protestant imagination as American missionaries sponsored the immigrations of Koreans to this area in the broader context of the rising U.S. hegemony in the Pacific. In particular, the exiled community of anti-Japanese Korean Christians in Los Angeles and San Francisco (1920s–1930s) had a somewhat legendary reputation among colonial-period Christians, who had close contacts with American missionaries. The Cold War relationship of dependence between the U.S. and South Korea further heightened the colonial-period Christian idealization of the U.S. West Coast and the U.S. in general. The volume of U.S. aid reportedly given to South Korea is truly revealing in this regard: the U.S. spent $600 for every Korean per year from 1945 to 1976, all because South Korea sat at the fault line of the Cold War.[55] The perceived stature of the U.S. during the 1950s and 1960s fueled the already prominent perception of the U.S. as a place of peace and prosperity.[56]

The U.S.-centrism that underwrote many exiles’ migration to Los Angeles seems to reflect the émigré composers’ shared tendency to idealize Western music as the legitimate musical “language” of South Korea. Indeed, this was the key quality that distinguished them from the non-exiled Christian composers. As the chapters on the non-exiled Christian composers in Kim’s anthology make evident, non-exiled Christian composers were more open to assimilating elements of Korean music into the Western framework of secular and religious compositions, and if they left South Korea to study music in the West after 1945, it was to explore what is musically “Korean” and to mediate it within this framework (comparable to other twentieth-century composers from Asia and Latin America who used their studies in Europe, especially Western or Central Europe, to create a “national style”). In contrast, when the exiled composers went to the West, most commonly to Los Angeles but also to other American cities, it was usually to learn about what is musically “Western.” As I will show in the next section, this version of cosmopolitanism, one that privileged Western classical music style in its “pure” manifestation, had far-reaching consequences for the musical life of the post-1945 South.

Music Styles and Narrations of Nation

Broadly speaking, the musical culture surrounding Protestant exiles promoted a Western classical music idiom, especially common-practice music, as the official musical “language” of Cold War South Korea. Records and archives of this official culture (for instance, program notes of concerts, enrollment records of university music departments, music textbooks, and so on) trace the ascendancy of this “language,” and recent studies based on these records outline this development. For example, Chŏng Chŏng-yŏn’s study based on the early concerts of the KSA documents lists Beethoven, Schubert, Strauss, and Tchaikovsky as the Association’s canonical composers;[57] similarly, Min Kyŏng-ch‘an states that more than a hundred university departments of Western music were established in Korea from 1950 to 1970—compare this with fewer than a dozen bachelor-level programs teaching traditional Korean music during the same time.[58]

Yet, to consider only what exists in the records is to miss the other half of the story. Christian exiled composers were welcomed by pro-U.S. elites because they could be positioned structurally to eclipse other candidates seeking to contribute to the musical life of the newly independent nation. When official sources are read against the grain of elite narratives and when new bodies of historical sources are consulted, marginalized musicians begin to come into view. In what follows, I discuss music practices that were masked and others that became normative. This discussion will show that the economy of replacement aimed at controlling the musical representation of the South Korean nation and the official discourse concerning the relationship between the nation and musical style.

Sources made available to the South Korean public in 1988, which I discussed briefly in the introduction, uncover a number of socialist composers and/or musicians who thrived in post-liberation Seoul (1945–46) but were terrorized beginning in late 1947 by paramilitary rightist groups and consequently fled to the North, roughly between 1947 and 1950.[59] A number of concerts and festivals staged by leftist organizations were terrorized beginning in 1947, including a festival on January 8, 1947, organized by the KMC and other socialist art organizations, as well as a KMC concert on June 30, 1947.[60] A warrant was released for a number of KMC composers by Seoul’s police chief in August 1947, on the grounds that they were engaging in “acts of disturbing the public order by replacing leisure with politics and propaganda.”[61] Many of these self-identified socialists came to the post-liberation music scene with a strong background in Western music, reflecting their privileged status during the colonial period: they tended to belong to elite and/or Christian families in Seoul.[62] The formerly classified documents indicate that although they were not opposed to the continuation of Western music or cultural dialogues with the West, they campaigned for a decolonialized national culture as a condition for music making. By writing cultural manifestoes and hybrid compositions, they demanded that Koreans take ownership of their music, reflect on the musical legacies of colonialism, and plan for balanced ways of importing foreign music (see introduction).

It seems that this set of goals was generally uncontroversial, but these socialist composers’ national liberation anthems posed a clear threat to the political elites in the South. Short, celebratory songs based on Korean folk music and Western-style military anthems, national liberation anthems were taught and sung in mass rallies in the South: these rallies were assembled spontaneously from late 1945 to 1947—the two-year window before the formal division of Korea in 1948—to celebrate Korea’s independence from Japanese rule, and beginning in 1948 they took the form of massive rebellions organized by local people’s committees, concentrated in the southwestern parts of Korea (for example, the Yŏsu Rebellion of 1948 and the Cheju Rebellion of 1950).[63] If the self-identified socialists’ compositions in prestigious Western music genres were decolonial in aspiration, their national liberation songs were anticolonial and sounded the composers’ affiliation with the masses. Their texts featured terms like “blood of the people,” “the enemy,” and “imperialists,” narrating a national story that began with the liberation of the people from an exploitative empire. Although the precise number of these songs is unknown, one study states that in 1946 alone at least seventy-five liberation songs were presented to the public at music events called Haebang kayo sinjak palp‘yohoe (New Liberation Songs Presentation).[64] “Haebang ŭi norae” (Liberation Song, 1945–46?), written by a leading socialist composer of the time, Kim Sun-nam, is an early example that influenced this short-lived genre (fig. 1). [65]

According to Min Kyŏng-ch‘an, a few national liberation anthems were included in the first edition of the U.S.-funded music textbook for use in Korean secondary schools (1946), but they were replaced by Lied-style songs (see below) in the second edition (1948).[66] It is not difficult to see why the conception of the nation articulated by the liberation anthems would have alarmed the elites and the U.S. military government. As Bruce Cumings examined in detail in Korea’s Place in the Sun, many of Seoul’s elites, who had histories of collaboration with the Japanese colonial government, feared the anticolonialist sentiments pervading the mass liberation rallies because these assemblies tended to include public denunciations of colonial-period collaborators. Similarly, the anticolonial ethos of the rallies worried the U.S. military government and their Korean allies because it tended to converge with socialism, as the second verse of Sun-nam Kim’s “Haebang ŭi norae” demonstrates. In evoking class conflict and condemning Koreans who worked for the benefit of the colonial ruling class (the Japanese colonialists), the rallies seemed to echo the rhetoric of the People’s Committees, which, according to revisionist histories, were spreading throughout the southern part of Korea from 1945 to 1950 much more rapidly than the official Cold War narratives have suggested.[67] Fear of the mutually reinforcing relationship between populism, anticolonialism, and socialism precipitated the alliance between the exiled Christians, southern elites, and the U.S. military government, giving them a reason to transcend their internal differences. One notable difference involved colonial-period loyalty between Seoul-based composers and exiled composers from the North: the former tended to face tremendous pressure to collaborate with the colonial government in Seoul as a condition for participating in colonial-period Western music organizations, and for the most part, the latter did not face the same dilemma due to their residence away from the colonial capital.[68]

Other musical practices that became stigmatized in midcentury South Korea concern shamanist and shamanist-influenced music practices. Several studies demonstrate that during its formative years the South Korean state reclaimed the genealogy of court music as “national music” (kugak) over and against performances rooted in shamanist-influenced traditions, such as itinerant theater, rural festivals, and shamans’ rituals, which were central to the life of the lower classes in the late Chosŏn period (sixteenth century to 1910). In her 2014 study, Hyejin Choi documents two groups of traditional musicians competing for state sponsorship in the South from 1945 to 1948 and argues that what was at the stake in this competition was the question of what should count as “national music.” Members of a group called Taehan Kugagwon (Korean National Music Institute) proposed a concept of national music that included not just aak (precolonial Korean court music) but also nongak (farmers’ music) and ch‘anggŭk (popular opera); in contrast, Yi Wangjik Aakpu (Yi Royal Music Institute) put forth a court music-centered definition of national music, with one of its members arguing that common people’s music is “laughable but also something to be feared.”[69] The South Korean state chose to nationalize aak in 1948 following Yi Wangjik Aakpu’s active lobby of the budding national assembly. This led to the establishment of the Kungnip Kugagwon (National Classical Music Institute) in 1950, decreed by Presidential Order No. 271.[70] At least seven members of the Taehan Kukagwon were exiled to the North between 1945 and 1950,[71] and the head of this institute, Ham Hwa-jin, was arrested in 1947, the year that the pro-U.S. and U.S. forces in the South began to purge individuals thought to be connected with the South Korean Labor Party (Namrodang) and/or leftist organizations.[72]

To be sure, the incrimination and exile of certain musicians practicing and advocating folk traditions did not mean the disappearance of these traditions from the midcentury South Korean cultural landscape: ch‘angguk, for instance, remained popular well into the 1950s as scholars such as Andrew Killick and Man-young Hahn have documented, and the South Korean state mobilized folk musicians for its anticommunist, anti-North campaigns in the rural areas during the Korean War (1950–1953) even as it sponsored court music at the official level.[73] What I highlight is the delegitimation of folk musicians within the terrain of official Cold War discourse. This is in fact a process with a long history: in precolonial Korea, court musicians, who saw themselves as the guardians of the state-sponsored neo-Confucian tradition, often held shamanist practitioners in contempt; and beginning in the late nineteenth century, shamanist practices were significantly marginalized partly due to a far-reaching North American Christian missionization project in Korea.[74] In addition to these factors, new forms and of leisure and entertainment that emerged in the context of postwar urbanization, along with their accompanying infrastructures, exacerbated the decline of the status and visibility of folk musicians—kisaeng (female courtesan entertainers), acrobats, rural percussion groups, popular theater vocalists, and shamans, among others. As Man-young Hahn summarizes: “... singers who had established good reputations found that they could no longer make a living from music. Only a few continued to devote themselves to singing and teaching.”[75]

An official music culture began to fill the void created by the suppression of socialist musicians’ compositions and indigenous performing practices, especially in the cities that were growing at an explosive rate since the 1950s. Kagok (歌曲) stands out as a secular genre of official nationalism beloved by the exiled Christian composers.[76] Modeled on the characteristics of the Germanic Lied and influenced by North American Protestant hymnody, kagok had its roots in the Christian-affiliated networks in colonial P‘yŏngyang and, to a lesser extent, colonial Seoul. During the colonial period, this art song genre served as an important pedagogic medium through which the first-generation Korean Christian students of Western music practiced the art of setting a melody to harmonic progressions, informed by the Lied as well as North American Protestant hymns.[77] In addition to continuing this pedagogic function, the Cold War kagok served as a site of exilic imagination. Many kagok songs romanticized the South Korean nation by remembering North Korea as a lost but beautiful land in the context of the massive southward migration, the Korean War, and the ensuing national division. Representative kagok compositions spoke sadly and romantically about the natural landscapes that symbolized the northern part of Korea, for example, Mount Paektu and Mount Kŭmgang. This way, the genre of kagok enabled the singers to personify a suffering subject longing for a “forsaken” home and thus resonated with anticommunist imagery of loss that tended to vacillate between sentimental self-defeat and retribution.[78] As historical subjects who could claim nostalgia for the North based on their own lived experience, the émigré composers bestowed the ethos of longing upon the broader composition scene in the South via exemplary compositions. In turn, their kagok inspired hundreds of new kagok pieces throughout the 1950s and 1960s that articulated a vague but profound feeling of longing or sang of specific landscapes in the North. The titles of some of the most popular Cold War-era kagok illustrate this orientation: “Kohyang saenggak” (Thoughts of the Homeland), “Kohyang ŭi norae” (A Song from the Homeland), “Kohyang kŭriwŏ” (Longing for the Homeland), “Kŭriwŏ” (Longing), “Kŭrium” (Nostalgia), “Kwihyang ŭi nal” (The Day of Return), “Paektusan ŭn sotsa itta” (The Soaring Mount Paektu), and “Kŭriun kŭmgangsan” (Longing for Mount Kŭmgang).

For an example of a particularly charged kagok song, we can take a brief look at “Kŭriun kŭmgangsan” (Longing for Mount Kŭmgang, 1961), composed by the Seoul-born composer Choe Yŏng-sŏp (1928–).[79] Like Kim Sun-nam’s “Liberation Song” quoted above, this song articulates an enemy—consider the use of the word “tainted” to describe the now-forsaken mountain in the North and the ending phrase “Mount Kŭmgang is calling me” (see Fig. 2). Yet this exilic song uses a very different expressive framework to create a sense of emotional urgency. Instead of the military ethos of the liberation anthems, “Kŭriun kŭmgangsan” fuses an anticommunist text with the theatrics of suffering, encoded by the juxtaposition of drawn out notes (half or dotted half notes) with agitated gestures conveyed by mordents and descending sixteenth-note figures, the dramatic arpeggiation of the piano accompaniment, the slow tempo, and the explicit direction in the score to “sing with a deep-rooted nostalgia.” This set of techniques, shared widely across kagok songs, enabled the singing subjects to wallow in the real or imagined experience of victimization and nostalgia and to convey a sense of galvanization in the process of singing.[80]

| Who presides over it, the pure and beautiful Mountain? | Nugu ŭi chujaerŏn’ga malkko koun san |

| The twelve thousand peaks that I long for stand silently, | Kŭriun manich‘unbong marŭn ŏpsŏdo |

| But finally, the free people, struck with reverence, | Ijeya chayumanmin otkit yŏmimyŏ |

| Will call that name again, Mount Kŭmgang. | Kŭ irŭm tasiburŭl uri kŭmgangsan |

| Its beautiful shape, for more than ten thousand years | Susumannyŏn arŭmdaun san |

| For some years, it has been tainted. | Tŏrŏphinji myŏthae |

| Is today a good day to seek it? | Onŭreya ch‘ajŭl nal watna |

| Mount Kŭmgang is calling me. | Kŭmgangsan ŭn purŭnda |

Arguably, midcentury Protestant vocal music was even more effective than kagok songs in administering Cold War nationalism for a number of reasons. First, while kagok’s subject enacted a sentimental suffering, the suffering subject in this religious genre demanded absolute redemption from dispossession in an environment in which religious redemption was easily conflated with political redemption. Second, midcentury Protestant vocal music reached a much larger audience than kagok. While kagok had associations with the elite concert-going audience, Protestant vocal music was staged for a rapidly increasing number of Koreans of all social classes who filled the pews of churches in the aftermath of the Korean War. Indeed, the number of South Koreans who would have seen and listened to the performances of these vocal compositions may be quite significant: the number of Protestant converts grew at an exceptionally high rate in South Korea during the high Cold War decades, with some studies conservatively estimating them at twenty-five to thirty percent of the entire population.[81] The Cold War-era church choirs, then, may even be reconsidered as a thriving site of music pedagogy for the emerging middle class. These choirs were the only musical bodies in which nonelite Koreans could obtain amateur training in a musical language that was becoming remarkably prestigious—compare this with the burgeoning community choirs in Japan, which were created around this period to satisfy the Japanese middle class’s fascination with European classical music.[82] A third point to consider is that midcentury Protestant vocal music dovetailed with the musical ideals of the official culture because it was invested in jettisoning traditional Korean music styles from the pool of legitimate music. The statements of a number of émigré composers who were active in the Cold War years illustrate the anxiety about musical indigenization and stylistic hybridity that troubled the project of Protestant composition during the of Cold War years. For instance, Ku Tu-hoe (1921–), a prominent exiled composer, responded to some musicians’ efforts to repurpose the melodies of Korean folk songs as Protestant hymns in 1976 with an argument that appealed to the musical monogenealogy of Christianity. He wrote: “In Korea, there was music for the pursuit of pleasure but there was no music for religion. It is a sophistry to try to convert a tradition that is so fundamentally different [from Christianity]. It is like trying to make Christianity absurd.”[83] Kim Kyu-hyŏn’s interview with Ku also communicates a similar orientation. Commenting on the issue of “indigenization” (t‘och‘akhwa), Ku stated, “When there are so many good rhythms in church music, it is ludicrous to consider rhythmic cycles like kutkŏri and semach‘i [rhythms used across shamanist-influenced music] to make a comment on Koreanness ... It is a very dangerous idea to consider materials for evil spirits [chapsin] for church music.” [84] Kim Tu-wan, an exiled composer and the most beloved choral music composer in South Korea after the Korean War, was not as vocal as Ku Tu-hoe, but he was also guided by notions of “correct” music style for Christian musical worship in South Korea. Kim Kyu-hyŏn explains: “in his early career, Kim Tu-wan studied national music [kugak] in order to write Korean church music and even composed a few pieces in this style, but he realized that this was not the right form [chŏnghyŏng] of church music. Since then, he has combined the Western tonal style with church modes.”[85]

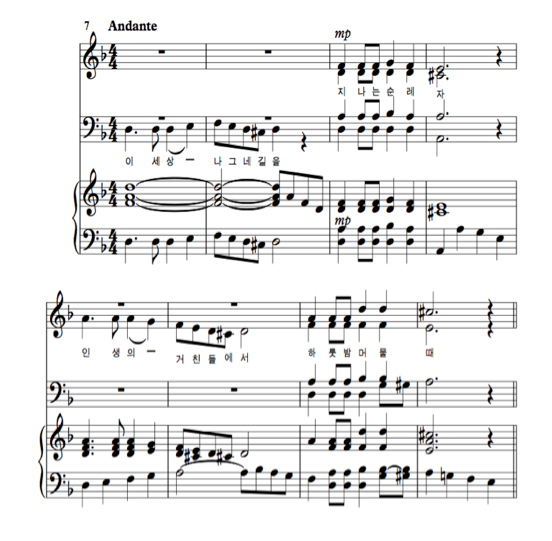

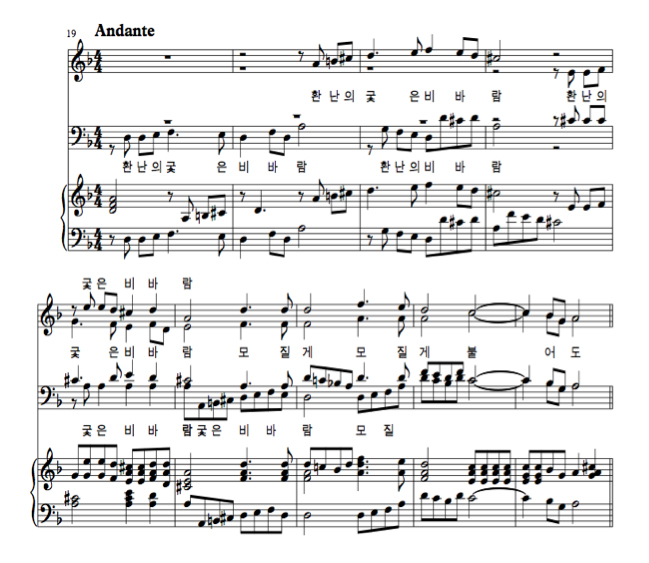

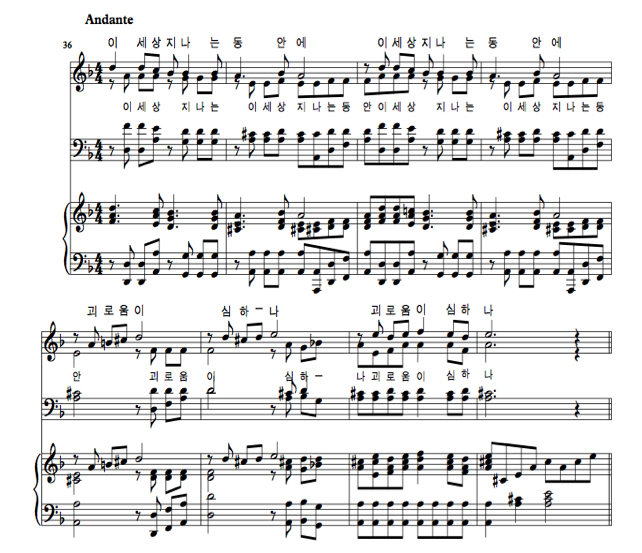

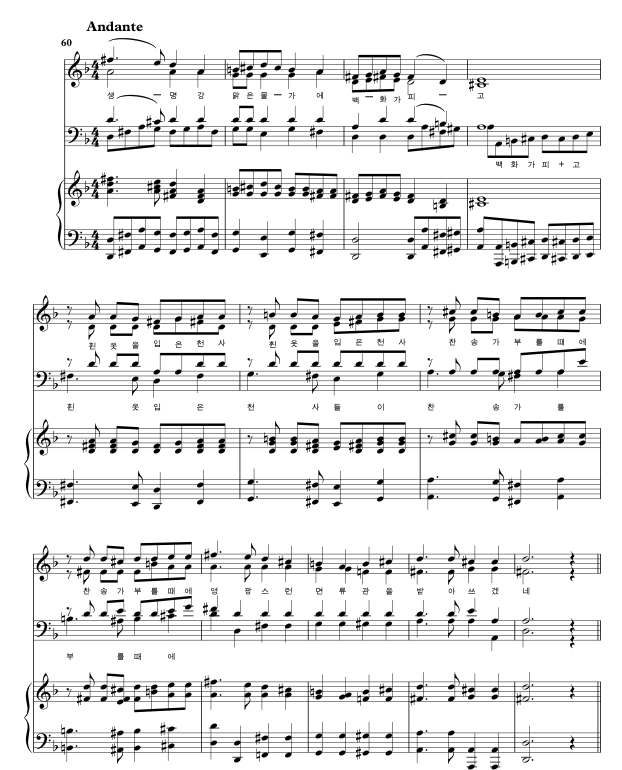

For a prototype of Cold War Protestant choral music, we can return to Kim Tu-wan’s “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane” (Heading for the Homeland, late 1950s–60s), a piece that, according to Kim Kyu-hyŏn, “searched for the root of Korean Christian music.”[86] Indeed, it seems to articulate an ethos of suffering that came to be known as particularly (South) Korean by using a compelling diatonic language directed at amateur choristers. “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane” is built on four discrete, repeating sections that make up the narrative parts of a pilgrim’s experiences: desolation, crisis, suffering, and redemption. The piece starts in a hushed D minor setting in order to narrate the despondent beginning of a pilgrimage. A sense of dejection is conveyed by the juxtaposition of the bare bass and alto melodies with subdued choral responses and the harrowing endings of the two-measure phrases.[87]

The second section uses a chromatically inflected counterpoint to dramatize “the ordeal of the violent storm.” The voices’ staggered entrances and their contrapuntal engagement serve as the musical codes of the storm depicted in the lyrics.

The third section uses a combination of contrapuntal and homophonic textures to stage a collective declamation of suffering. The soprano singers’ dramatic phrases are answered by an impassioned subchoir of alto, tenor, and bass parts, all of which navigate dynamic melodic contours while also moving together in a homophonic fashion.

The fourth section depicts divine deliverance from the crisis. Fittingly, it begins with an unexpected cadence onto a D major triad on the word “life.” The use of the key of D major, not heard until this point, evokes an imagery of triumph. This section’s middle phrase, “the angels cloaked in white garb sing praises,” is set to a rising sequence that culminates in an authentic cadence on the phrase “the pilgrim will wear the honorable crown.”

The piece then returns to the very first section, leaving the audience with the haunting imagery of a forlorn pilgrim who, as the final words have it, “is headed for the homeland.”

In my own experience as the piano accompanist of diasporic Korean church choirs spanning ten years (1993–2000, 2008–2010), I encountered the remarkable popularity of “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane” among the conductors and choristers, most of whom were first-generation immigrants who came of age in South Korea during the high Cold War years. Whenever the conductors announced this piece as the upcoming assignment, they did so in the manner of giving a tribute to the composer and with an introductory description of the piece as “a symbolic Korean Protestant piece” or “a uniquely Korean piece.” The choristers demonstrated a unanimous enthusiasm during each and every rehearsal of this piece—a response rarely given to other pieces in the repertory. Importantly, I have noticed an intimate relationship between such a reception and the piece’s pedagogic instrumentality. Not only is “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane” an effective lesson in diatonic harmony in general but it also expands the singers’ experience of Western choral music by introducing them to contrapuntal part writing, which is relatively absent in the wider South Korean Protestant choral repertory. During each rehearsal of this piece, the choristers (especially basses and tenors) practiced with an unusual rigor to learn their parts and to understand how their respective parts related to the rest of the choir. It seemed that the level of challenge entailed in the piece is what kept them engaged: the polyphony in “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane” tracks the harmonic progression closely, and thus, if the choristers put in the effort, it is possible for them to make sense of the part writing in the context of their accumulated knowledge of diatonic music. These moments of musical revelation seemed to reinforce the inner experience of suffering elicited by the piece. The choristers carried such compelling experiences into the Sunday services: each time they performed this piece, they commanded the music compellingly, and the congregation’s positive feedback (such as, nods, applause, enunciations of “amen” immediately after the piece, and personal acknowledgement to the singers after the service) reaffirmed the authenticity of performance.

Conclusion: The Politics and Poetics of the Cold War

In her study of Cold War-period Asian and Asian American fiction, Jodi Kim uses the term “fraught hermeneutics” to encapsulate the challenges entailed in analyzing Cold War-era literature in Korea, East Asia, and Asian America. Kim argues that to critically analyze this literature is to be sensitive to its conditions of possibility rather than opting for interpretations that resist simple narratives of transcendence or opposition, which would reproduce the very Manichean analytics enabled by the Cold War.[88] Pieces like “Ponhyang ŭl hyanghane,” then, are valuable to music historians not just because they allow us to listen to some of the most compelling representations of the Korean Cold War experiences, but also because they draw our attention to the complex relationship between Cold War politics, trauma, victimization, and poetics. Still widely sung across Christian churches in South Korea and the Korean diaspora, it also allows us to reflect on the protracted nature of the Cold War poetics. As Bruce Cumings noted, “The political and ideological divisions that we associate with the Cold War ... came early to Korea, before the onset of the global Cold War, and today they outlast the end of the Cold War everywhere else.”[89]

It is with this view of the fraught nature of Cold War cultural production in South Korea that I return to the discussion of South Korean musical cosmopolitanism and consider its meanings for notions of postcoloniality. As I have suggested throughout this article, it is important to consider that what has been widely celebrated as musical cosmopolitanism in South Korea also implicated a foreclosure of conversations about postcolonial music culture and cultural legacies of colonialism in the name of the Cold War, especially the project of integrating South Korea with the Cold War West. Indeed, tensions over the issue of what really counts as “Korean” have cropped up in cultural representations as a haunting problematic, beginning as early as the 1960s—a phenomenon that I explore elsewhere.[90] Further ethno/musicological studies on twentieth-century music practices in South Korea and, more broadly, the Asian Pacific and Asian America, would benefit from their conceptualization as sites of locally meaningful yet transnationally inflected cultural formations that grapple with the problems of national identity, modernity, and postcoloniality. This perspective, in my view, would transform our perspective on music cultures in (post)colonial centers and peripheries—from past events recorded in the archives to social formations that continue to reconstitute our emotions, memories, and knowledge.

Appendix: Information on Christian exiled composers, based on Kim Kyu-hyŏn’s 2006 anthology

| Composer | Before 1945 (during the colonial period) | 1945–1970s | 1970s– | Secular music |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Pak, T‘ae-jun (1900–1986) |

|

|

|

|

| Yi, Yu-sŏn (1911–2005) |

|

|

|

|

| Ku, Tu-hoe (1921–) |

|

|

|

|

| Pak, Chae-hun (1922–) |

|

|

|

|

| Kim, Tu-wan (1926–2008) |

|

|

| |

| Paek, T‘ae-hyŏn (1927–) |

|

|

|

|

| Han, T‘ae-gŭn (1928–) |

|

|

|

|

| Kim, Kuk-jin (1930–) |

|

|

|

|

| Kim, Sun-se (1931–) |

|

|

| |

| Yi, Chung-hwa (1940–) |

|

|

|

|

| Paek, Kyŏng-hwan (1942–) |

|

|

|

|

| Kim, Jŏng-il (1943–) |

|

|

|

References

- Chang, Hyun Kyong. “Musical Encounters in Korean Christianity: A Trans-Pacific Narrative.” PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2014.

- Choi, Hyaeweol. Gender and Mission Encounters in Korea: New Women, Old Ways. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2009.

- Choi, Hyejin. “The Incipient Republic of Korea and the Invention of Kugak.” Paper presented at the Annual Meeting of the Association of Asian Studies, Philadelphia, PA, March 2014.

- Cumings, Bruce. Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History. Updated ed. New York: W. W. Norton, 2005.

- Fosier-Lussier, Danielle. Music in America’s Cold War Cultural Diplomacy. Berkeley: University of California Press, forthcoming.

- Hahn, Man-Young. Kugak: Studies in Korean Traditional Music. Translated by Inok Paek and Keith Howard. Seoul: Tamgu Dang, 1990.

- Harkness, Nicholas. “Culture and Interdiscursivity in Korean Fricative Voice Gestures.” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 21, no. 1 (2011): 99–123. http://dx.doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1395.2011.01084.x

- Kane, Danielle, and Jung Mee Park. “The Puzzle of Korea Christianity: Geopolitical Networks and Religious Conversions in Early 20th-Century East Asia.” American Journal of Sociology 115, no. 2 (2009): 365–404. http://dx.doi.org/10.1086/599246

- Lee, Katherine In-Young. “The Drumming of Dissent During South Korea’s Democratization Movement.” Ethnomusicology 56, no. 2 (2012): 179–205. http://dx.doi.org/10.5406/ethnomusicology.56.2.0179

- Howard, Keith. Creating Korean Music: Tradition, Innovation and the Discourse of Identity. Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2006.

- Kendall, Laurel. Shamans, Nostalgia, and the IMF: South Korean Popular Religion in Motion. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i, 2009.

- Killick, Andrew. In Search of Korean Traditional Opera: Discourses of Ch‘anggŭk. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 2010.

- Kim, Illsoo. New Urban Immigrants: the Korean Community in New York. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 1981.

- Kim, Jodi. Ends of Empire: Asian American Critique and the Cold War. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

- Lee, Namhee. The Making of Minjung: Democracy and the Politics of Representation in South Korea. Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2007.

- Lee, Timothy Sanghoon. “Born Again in Korea: The Rise and Character of Revivalism in (South) Korea, 1885–1988.” PhD diss., University of Chicago Divinity School, 1996.

- Underwood, Elizabeth. Challenged Identities: North American Missionaries in Korea, 1884–1934. Seoul: Royal Asiatic Society, Korea Branch, 2003.

- Wade, Bonnie. Composing Japanese Musical Modernity. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2014.

- Wells, Kenneth M. New God, New Nation: Protestants and Self-Reconstruction Nationalism in Korea, 1896–1937. Honolulu: University of Hawai‘i Press, 1990.

Works in Korean

- Chŏng, Chŏng-yŏn. “Haebang konggan ŭl chudo haettŏn ŭmak ka.” [The Leading Musician of the Liberation Period] Minjok ŭmak 1 (1990): 162–207.

- Chŏng, Su-jin. “Chosŏn ŭmak, chosŏn ŭmakka ŭi kollan.” [The Predicament of Korean Music and Korean Musicians] Han‘guk minsogak 41, no. 1 (2005): 387–418.

- Hong, Chŏng-su. Han’guk kyohoe ŭmak sasang sa [The History of Ideology of Korean Church Music]. Seoul: Changnohoe sinhaktaehakkyo chu‘lp‘anbu, 2000.

- Kang, In-ch‘ŏl. Han’guk ŭi kidokkyo wa pan’gong chuŭi [Korean Protestantism and Anticommunism]. Seoul: Chungsim, 2007.

- Kim, Kyu-hyŏn. Kyohoe ŭmak chakgokka ŭi segye [The World of Korean Church Music Composers]. Seoul: Yesol, 2006.

- Kim, Tong-sŏk. Ppurŭjoa ŭi ingansang [Portrait of the Bourgeoisie]. Seoul: T‘amgudang, 1949.

- Min, Kyŏng-ch‘an. Han’guk ŭmaksa [History of Music in Korea]. Seoul: Turi midia, 2006.

- ———. “P‘iano ŭi yuip kwa p‘ianisŭtŭ ŭi t‘ansaeng.” [The Introduction of the Piano and the Birth of the Pianist] P‘iano ŭmak 127 (2007): 126–131.

- ———. “Wŏlbuk ŭmak in ŏttŏn chakp‘um namgyŏtna.” [What Kinds of Work Did Northbound Composers Leave?] Ŭmak tong-a 6 (1988): 99–103.

- No, Kwang-uk. “Minjok ŭmak ŭi tugaji choryu.” [Two Currents in Korean Ethnic Music] Minsŏng 5, no. 1 (1949): 62–63.

- No, Tong-ŭn. Kim sun nam kŭ ŭi samgwa yesul [Kim Sun-nam, His Life and Work]. Seoul: Nangman ŭmaksa, 1992.

- Pak, Yong-gu. Ŭmak kwa hyŏnsil [Music and Reality]. Seoul: Mingyosa, 1949.

- Yi, Kang-suk. Ŭmakchŏk mogugŏ rŭl wihayŏ [Toward an Understanding of Musical Mother Tongue]. Seoul: Hyŏnŭmsa, 1985.

- ———. Yŏllin ŭmak ŭi segye [An Open World of Music]. Seoul: Hyŏnŭm sŏnsŏ, 1980.

Notes

A note on romanization: Korean names and terms in Korean (e.g., musical works, genres, and organizations) are romanized according to the McCune-Reischauer system. Surname is placed before given name. Exceptions are Korean authors who have published in English and well-known historical names (e.g., Syngman Rhee). All translations are mine.

In-ch‘ŏl Kang, Han’guk ŭi kidokkyo wa pan’gong chuŭi [Korean Protestantism and Anticommunism] (Seoul: Chungsim, 2007), 173–80.

Timothy Sanghoon Lee, “Born Again in Korea: The Rise and Character of Revivalism in (South) Korea, 1885–1988” (PhD diss., University of Chicago Divinity School, 1996), 129.

The remarkable growth of Protestant churches in P‘yŏngyang and the surrounding areas in the North in early twentieth century is recorded in contemporary North American Protestant mission literature as well as Japanese imperial reports. For instance, a Methodist missionary in P‘yŏngyang (William Noble) reported that in 1906 each of the Methodist churches in P‘yŏngyang attracted 700 people every Sunday, with Changdaehyŏn Church attracting 1,400 Koreans. The Japanese Residency-General in Korea noted in 1909 that the Christian churches in the northern provinces of Korea were replacing traditional status-based institutions. See Hyun Kyong Chang, “Musical Encounters in Korean Christianity: A Trans-Pacific Narrative” (PhD diss., University of California, Los Angeles, 2014), 48–49.

The estimates tend to vary according to the ideological leaning of each study. The higher of these two estimates is from Timothy Sanghoon Lee’s monograph (128) and the lower one, from Kang In-ch‘ŏl’s monograph (409).

See Bruce Cumings, Korea’s Place in the Sun: A Modern History, updated ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2005), 185–298.

Since 1988 at least twenty Korean-language articles have examined KMC artists in the context of Seoul’s music scenes between 1945 and 1948. Here I cite two: Kyŏng-ch‘an Min, “Wŏlbuk ŭmak in ŏttŏn chakp‘um namgyŏtna,” [What Kinds of Work Did Northbound Composers Leave?] Ŭmak tong-a 6 (1988): 99-103; Chŏng-yŏn Chŏng, “Haebang konggan ŭl chudo haettŏn ŭmak ka,” [The Leading Musician of the Liberation Space] Minjok ŭmak 1 (1990): 162–83. Critical post-Cold War approaches in South Korean musicology have also been reinforced by the so-called Cold War revisionist historiography. See, for a representative example, Cumings, Korea’s Place. First edition published in 1997.

The July 7 Presidential Declaration meant the partial abolition of anti-North Korea, anticommunist propaganda. A leading newspaper in Seoul stated that it reversed a 1954 legislation that banned the works by southern artists who “lived north of the division line at the conclusion of the Korean War” and whose migration was assumed to be due to “voluntary exile rather than abduction.” It mentions that the works of 120 writers became available to the South Korean citizens at select public libraries. See “‘Wŏlbuk chakp‘um,’ chalp‘ulŏtta,” [Ban on Northern Exiles’ Works, Successfully Lifted] Han‘guk ilbo, September 4, 1988. South Korean musicologist Min Kyŏng-ch‘an lists fifty-three south-to-north music critics and composers whose works were banned prior to 1988. Kyŏng-ch‘an Min, Han’guk ŭmaksa [History of Music in Korea] (Seoul: Turi midia, 2006), 198–99.

Kwang-uk No, “Minjok ŭmak ŭi tugaji choryu,” [Two Currents in Korean Ethnic Music] Minsŏng 5, no. 1 (1949), 63. Also consider poet and KMC member Kim Tong-sŏk’s critique of Western classical music written in same year: “I have always loved German classical music and know what it feels to be intoxicated by the music of Bach and Mozart. But I have also felt that this music makes us feel as if we are not living in today’s time and sometimes even despise the present ... It is a trap that goes in the name of innocence.” Tong-sŏk Kim, Ppurŭjoa ŭi ingansang [Portrait of the Bourgeoisie] (Seoul: T‘amgudang, 1949), 262–63.

By most accounts, the adoption of Western classical music in Korea began in the late nineteenth century as part of the North American Protestant missionization.

See, among others, Kang-suk Yi, Ŭmakchŏk mogugŏ rŭl wihayŏ [Toward an Understanding of Musical Mother Tongue] (Seoul: Hyŏnŭmsa, 1985); Tong-ŭn No, Kim sun nam kŭ ŭi samgwa yesul [Kim Sun-nam, His Life and Work] (Seoul: Nangman ŭmaksa, 1992); Min, Han’guk ŭmaksa, 2006.

No, Kim sun-nam, 7. Also noteworthy is the journal Minjok ŭmak [People’s Music], founded in 1990 as a venue for Cold War revisionist studies. One of the stated goals of the journal is “to re-examine the uncritical, anti-democratic fascination of Koreans for Western music.” Inaugural statement, Minjok ŭmak [People’s Music] 1, no. 1 (1990): 9.

See Nicholas Harkness, “Culture and Interdiscursivity in Korean Fricative Voice Gestures,” Journal of Linguistic Anthropology 21, no. 1 (2011): 99–123.

See Keith Howard, Preserving Korean Music: Intangible Cultural Properties as Icons of Identity (Aldershot, UK: Ashgate, 2006).