“It was never a Nazi Orchestra”: The American Re-education of the Berlin Philharmonic[1]

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

By the conclusion of World War II, Germany had been reduced to a premodern society. The brutality of the Nazi Regime, in conjunction with the aerial bombing of the Allies, exacted an inconceivable material and human toll.[2] Berlin, the former Hauptstadt of the Third Reich, was little more than a crater whose ruins provided an eerie, phantasmagorical landscape through which survivors could wander. But while rubble could be cleared away and cities rebuilt, how would the Allies monitor German cultural reconstruction to ensure there would not be a revival of Nazism?

American occupation authorities firmly believed that the Nazis had manipulated German high culture, and especially music, to serve as a propaganda tool. Consequently, the American Military Government made special provisions for the treatment of culture in the postwar era by creating the Information Control Division (ICD), an organization with branches designed to monitor German radio, literature, film, theater, and music. The Americans, more than any other ally, considered the German musical establishment’s relationship to fascism a dangerous problem and designed their cultural re-education programs with this in mind. As Chief of the Theater and Music section, Benno Frank, contended even two years after Germany’s surrender:

Only a few people outside of Germany were familiar with political leaders like Hess, Ley, Ribbentrop, etc., but artists like Richard Strauss, Gerhard Hauptmann, and Wilhelm Furtwängler were internationally known and recognized. Today it may be said that Hitler’s success in using these prominent cultural figures has decisively contributed to the prestige of the Nazi Regime.[3]

The American occupiers were well aware of the regime’s former “prestige”. By using classical music as a re-education tool, American authorities hoped to prove that American high culture was as refined as Germany’s and set about constructing fairly elaborate guidelines for classical rather than popular music. [4]

Ultimately, how would the American occupiers perceive their role as re-educators in Berlin, a city whose classical music culture had been the most highly politicized in all of the Third Reich? At the center of American cultural reconstruction efforts was the Berlin Philharmonic, the most illustrious ensemble residing in the American sector. Beginning in July of 1945, military government authorities regulated the ensemble’s repertoire, musicians, and management in accordance with denazification procedures, as the Philharmonic’s former role as the Reich’s chosen orchestra (Reichsorchester) made the orchestra particularly symbolic for American efforts in postwar Germany.

Still, American authorities would use the Philharmonic in much the same way the National Socialists had: as an orchestra for the re-education of audiences. Just as the Philharmonic had once concertized in support of the Nazi war effort, giving lengthy tours throughout occupied Europe, the ensemble was also the sound of the Allied occupation. Of the seventy concerts the Philharmonic played from May until December of 1945, more than one third (twenty-eight concerts) were performed especially for Allied soldiers.[5] Whereas the National Socialists had controlled the Philharmonic’s personnel on the basis of race, dismissing the orchestra’s four Jewish members in 1935, by 1945 the Americans had blacklisted six players who were former Nazi Party members.[6] The Berlin Philharmonic’s music was as highly politicized during the war as after, as musicians were subjected to the restrictions of the reigning regime in order to maintain their positions.

In order to investigate why American occupation authorities were so invested in the Philharmonic’s rehabilitation, it is essential to understand the orchestra’s cultural context in pre-World War II Germany. The ensemble was created in 1882 as a private corporation, with each musician buying into the orchestra at 600 Reichsmarks, giving the Philharmonic complete autonomy. Unfortunately, the orchestra’s business model was unsustainable and the Philharmonic began to have financial difficulties as early as 1912. The orchestra’s dire economic hardships continued throughout the 1920s as conductor Wilhelm Furtwängler and the ensemble’s management fiercely campaigned to have the Prussian, Reich, and Berlin city governments become the Philharmonic’s primary shareholders to save the orchestra from financial ruin. The proposed reorganization ultimately fell through, however, and the Philharmonic’s finances remained precarious.[7]

By 1933, as the National Socialists rose to power, the Philharmonic was 74,000 Reichsmarks in debt. But with the creation of the Propaganda Ministry in 1933, the Philharmonic had found a valuable financial ally, albeit at the price of the orchestra’s artistic autonomy. In January of 1934 Furtwängler made a Faustian bargain with Propaganda Minister Joseph Goebbels, agreeing to turn the ownership of the Philharmonic solely over to the Reich.[8] Philharmonic members were subsequently required to join the Reichsmusikkammer (Reich Chamber of Music), the organization that coordinated the Third Reich’s musical culture, then headed by President Richard Strauss and Vice President Wilhelm Furtwängler.[9]

But with governmental funding came an increasingly politicized framework in which the Philharmonic had to perform. The National Socialists wanted to exploit the orchestra’s reputation to lend a patina of respectability to the regime. Between 1934 and 1945, the orchestra played at Reichsparteitage (Nazi Party rallies), Hitler’s birthday celebrations, the Reichsmusiktage, and Hitler Youth gatherings. During the war, when it was nearly impossible to obtain travel papers to leave Germany, the musicians toured throughout Nazi-occupied Europe, including Belgium, Bulgaria, Croatia, Denmark, France, Holland, Italy, Poland, Romania, Serbia, and Spain.[10] At the close of each concert tour, orchestra members could bring back food and other materials that had grown scarce in Germany.[11] Not only were they the highest paid musicians in Germany, Philharmonic musicians were also exempt from military service because Goebbels considered concert tours just as vital as armed combat.[12]

But there were, of course, more sinister undercurrents within the Philharmonic during the 1930s and 40s.[13] The four Jewish members of the orchestra—concertmaster Szymon Goldberg, first violinist Gilbert Back, and cellists Nicolai Graudan and Joseph Schuster—left Germany by 1935 under mounting pressure from Nazi authorities.[14] Three more Philharmonic players with Jewish wives immigrated to ensure their safety.[15] By the close of 1935, “Aryanization cards” were required of all Philharmonic players in order to keep their positions.[16] Furtwängler’s long-time secretary, Berta Giessmar, also Jewish, left Germany to work with Sir Thomas Beecham and the London Philharmonic.[17]

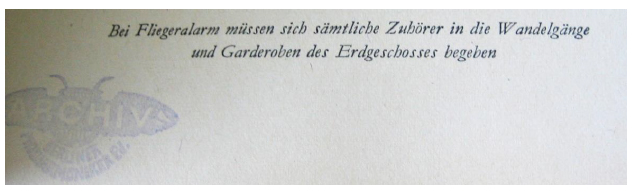

Apart from an increasingly hostile political environment, the remaining Philharmonic musicians also witnessed the destruction of their city. From 1943 until 1945, Berlin became the most heavily bombarded city in all of World War II, enduring 363 aerial attacks.[18] To avoid American and British nighttime bombing raids, Philharmonic evening concerts were rescheduled for 3 p.m. As attacks became more frequent, all programs were printed with instructions on how to proceed in the event of an air raid, urging audience members to take shelter in the coatrooms and hallways of the first floor. Lastly, as a special privilege, members of the Philharmonic and their families received Bunker Identification Cards that ensured them a place below ground.[19]

Precautions aside, however, the Philharmonic’s hall was hit by British phosphorus bombs on January 29, 1944, and burned to the ground within a few hours.[21] Even without a home to concertize in, the orchestra kept performing throughout Germany. The image of Nero fiddling while Rome burned seemed remarkably apt; even as military defeat became imminent, the Philharmonic’s resilience made German cultural achievement appear unflagging.[22] The Philharmonic’s final concerts under the Third Reich took place on April 15 and 16, 1945, in the Beethovensaal next to the ruins of the Philharmonic.[23] Robert Heger and George Schumann conducted the ensemble; Furtwängler had already left for refuge in Switzerland several months earlier.[24] The orchestra performed Carl Maria von Weber’s Oberon Overture, Brahms’s Double Concerto for Violin, Cello and Orchestra, and appropriately enough, Strauss’s Tod und Verklärung (Death and Transfiguration).[25] The last work was an apt choice; Strauss had written the tone poem to depict an artist on his deathbed contemplating his impending demise.

The first postwar Philharmonic concert was given on May 26, 1945, less than one month after Germany’s surrender. Hardly any concert venues remained intact, and the Philharmonic’s performance was given at the Titania Palast movie theater in Steglitz, a western suburb of Berlin. Leo Borchard, an extremely capable musician whom the Soviets had found hiding in a cellar during the Battle of Berlin, conducted the ensemble. (In the eyes of the Russians, it did not hurt that Borchard spoke fluent Russian from his childhood spent in Moscow, nor that he had been marginally active in Onkel Emil, a small, underground communist resistance group that hid Jews and provided them with falsified documents.)[26] At the inaugural postwar performance, Soviet officers entered with pistols brandished in the middle of Mendelssohn’s Midsummer Night’s Dream Overture, conversed loudly during Mozart’s Violin Concerto in A Major, and left during the final movement of Tchaikovsky’s Fourth Symphony. The German audience was powerless to protest.[27] The repertoire was undoubtedly chosen to reflect the orchestra’s and the nation’s break with National Socialism; Mendelssohn to reintroduce a work by a formerly entartet (degenerate) Jewish composer, and Tchaikovsky to please the Russians. While the German nation may have been defeated militarily, as one postwar critic noted, “In the midst of such shambles, only the Germans could produce a magnificent full orchestra and a crowded house of music lovers.”[28]

For just over two months, the Philharmonic was under Russian jurisdiction before the Americans arrived in Berlin on July 7.[29] The Philharmonic’s temporary concert hall was then taken over by the American Second Panzer Division, which intended to use the Titania Palast for troop variety shows.[30] The American Military’s Information Control Division (ICD) was staffed with civilian experts tasked with re-educating the German people through music, theater, film, radio, and literature. Although the pairing of Kultur and military rule would seem to be an odd one, at the height of the re-education project, the ICD employed 35 cultural officers and 150 German employees to monitor culture in Berlin.[31] Although massively understaffed, the klein, aber fein (small but fine) music officers were entrusted with an ambitious plan: to re-educate and reorient the local population by altering the performative context around German classical music. Effectively, this meant that there would no longer be musical performances to commemorate former Nazi holidays and that no marches or songs with patriotic themes would be performed at any time. “Horst Wessel Lied,” the Nazi party anthem, would no longer open concerts; and music that had been particularly favored by the regime would be carefully monitored to ensure it was not misappropriated.

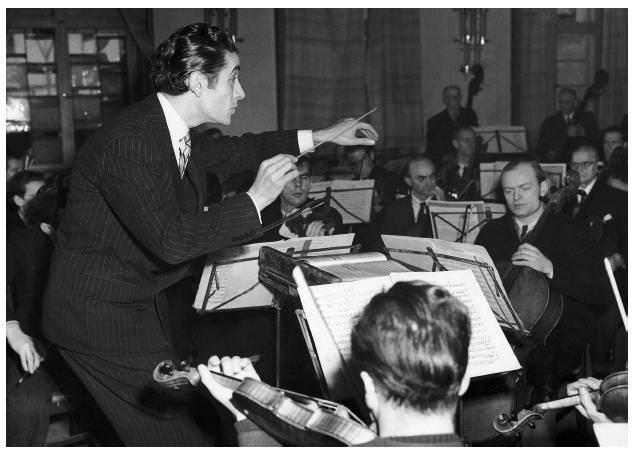

The officer most instrumental in the city’s cultural Wiederaufbau was John Bitter, head of Berlin’s Theater and Music section from 1945 to 1948. After graduating from the Curtis Institute in the 1930s with a degree in conducting, he lived for a year in Vienna, freelancing as a saxophonist and learning German. He led various Florida orchestras before becoming an Intelligence Officer with the Ninth Army in 1942,[32] and at the war’s conclusion, he decided to remain in postwar Germany as a music officer. His first and last assignment was in Berlin. Music officers took music control seriously because the ICD’s perception in 1945 was that musical life in Germany from 1933 to 1945 had been culturally barren, its very essence tainted and manipulated by Nazism.[33]

On July 31, British and American cultural officers met to discuss an eight-week plan for the Philharmonic with Borchard and the orchestra’s business managers. The Americans and British decided that Philharmonic concerts would take place every weekend, at the very least, and would alternate between the American sector’s Titania Palast and the British’s Theater des Westens. The Philharmonic would also be expected to give separate concerts for British and American troops, and as late as January 6, 1947, fortnightly Monday night concerts were open only to Allied soldiers.[34] Now that the Philharmonic was the resident ensemble of the American sector, it concertized in an exhausting number of venues—including Zinnowald Saal in Zehlendorf, Cosmos-Kino in Tegel, Quick Theater in Neukölln, Theatre des Westens, Titania Palast, and the Deutsches Opernhaus on Kantstrasse—while rehearsing primarily in Dahlem’s Jesus-Christus-Gemeinde.

Having the most prestigious ensemble in all of Hitler’s Reich under American control was a boon to cultural and intelligence officers; what the cultural re-education program lacked in terms of numbers of ensembles could be tempered by the Philharmonic’s worldwide renown.[35] According to regulations set forth by the ICD, each West Berlin ensemble was required to have a license supervised by an American cultural officer. The license was jointly issued in the name of the officer and principal conductor, who were also responsible for the ensemble’s artistic integrity. All musicians had to be registered with the ICD in order to ensure they had passed the denazification screening, and repertoire had to be approved ten days in advance by cultural officers, a policy stringently enforced from September 6, 1945, until May 31, 1947.[36]

John Bitter, as the supervisor and military license holder for the Berlin Philharmonic, was involved in everything from locating scores and practice venues to conducting the orchestra himself on more than thirty occasions, blurring his professional relationship to the ensemble even as he worked tirelessly to ensure the Philharmonic’s survival.[37] Bitter understood that the orchestra was a valuable asset in the game of cultural diplomacy, not only between the Americans and the Germans but also in relation to the other Allies. By mid-August, with the help of Bitter and cultural officer Frederic Mellinger, the Philharmonic had already amassed one hundred musicians, and was short by only ten members.[38]

Apart from shortages of musicians, however, musical scores were also difficult to find. Not only had countless scores been destroyed in the city’s firebombing, but it was nearly impossible to print new music due to a paper shortage that persisted until 1947. (The American Military Government even resorted to reusing certain Nazi Party office supplies for interoffice communication.)[39] Although some of the Philharmonic’s music had been moved from Berlin to a basement in Bayreuth, it would take American cultural officers over a year to arrange for its return. Significantly, American Military documents make note only of the music’s weight (250 pounds), rather than what scores were actually in the cache. According to one music officer, the re-acquisition was especially fortunate for the Philharmonic, as their programs were “increasingly cramped”[40] due to the absence of the scores. Furthermore, many of the Berlin Philharmonic’s instruments were gone, having either been stolen from their hiding place in the Plassenburg, a Renaissance fortress outside Bayreuth, or looted from the Philharmonic’s basement and bunker. Erich Hartmann writes, “Likewise, the instruments that had survived the firebombing in the basement of the alte Philharmonie fell into the enemies’ hands as booty and were taken east.”[41] Note that Hartmann makes certain to use “Feinden” or enemies, when referring to the Russians.

Although the Americans may have been victorious militarily, cultural re-education was still an arena in which they were at a decided disadvantage. Especially when compared to the Soviet occupiers, who well understood the value of music, art, and theater in promoting a political agenda, the Americans had difficulty implementing consistent policies in regard to denazification and re-education. While cultural officers were generally specialists in their respective fields, their superiors, like Military Governor Lucius Clay, were career military men who had difficulty grasping that high culture could provide anything more than mere entertainment. Consequently, the denazification and re-education agendas often pitted cultural officers against their military superiors.

Bitter did not appreciate his inferiors’ lax attitudes toward the Philharmonic; he was fully aware that the Orchestra could choose to move to the British, or worse yet, Russian zone. Infuriated that other military branches could not see the benefits of the ICD’s German re-education program, Bitter complained that military personnel would use the Titania Palast for mere variety shows, as he felt these trivial offerings had “a disastrous effect” on the reorientation program. “It is of the utmost importance,” he explained, “that we get the ear of a high authority in this matter so that the Titania, our best US sector theatre, is not used for second-rate variety shows.”[42] Bitter was not the only person annoyed by the variety shows; when violinist Yehudi Menuhin came to Berlin to perform with the Philharmonic in 1947, he had to plead with the military police on duty to allow the rehearsal to continue a few minutes past five o’clock. In the photographs, Furtwängler, leaning on the podium railing, is silently and uneasily observing the exchange.[43]

But the gravest error made by the American Military, in terms of cultural re-education, was the accidental shooting of the Philharmonic’s conductor. Around midnight on August 23, 1945, Leo Borchard was killed immediately when a young American solider opened fire on the car in which Borchard was traveling after the vehicle’s driver had failed to stop at a mandatory checkpoint. According to eyewitness testimony, Borchard’s final words, uttered moments before the accident, were simply, “Next time I will play Bach for you.”[44] As one might imagine, Borchard’s death, only six weeks after the American arrival, did little to endear the occupiers to German musicians. An untimely four days after his death, Newsweek ran an article on Borchard that made no mention of his death. Instead of his shooting, the magazine cheerily reported:

The problem of German music involves not only what to play—but who can be trusted to play it . . . Leo Borchard, 46-year-old conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic is the only man, according to many critics, around whom the orchestra can hope to rebuild.[45]

The story continued that Borchard couldn’t leave Berlin because the Nazis had prevented his wife from fleeing; the entire article was a fabrication—doubly so now that the article’s protagonist was dead. (It was not until 1955, ten years after the shooting, that the American military government declared Borchard’s death a Besatzungsschaden, or an occupation casualty, placing the blame on the British.)[46]

For the first time in its history, the Philharmonic was now without a clear successor for its conductorship. On August 25, two days after Borchard’s death, Robert Heger led the Philharmonic in a performance that opened with the Funeral March of Beethoven’s Eroica Symphony, dedicated to Borchard.[47] Only three months earlier, the same movement had been used to mourn Hitler’s death. But American authorities refused to consider Heger, who had been an active Nazi Party member, to be a legitimate replacement for Borchard.[48] Cultural officers wanted desperately to find a new director who was free from the political trappings of Nazi Party membership when an unexpected solution appeared in the form of a twenty-eight-year-old Romanian musician with dapper good looks and excellent timing.

“Celi” and the Philharmonic

In May of 1945, Sergiu Celibidache turned down the chance to flee Berlin as it fell to the Russians. When a group of fellow Romanians offered him a spot in their car heading west, Celibidache declined, reluctant to leave his composition manuscripts behind in Berlin.[49] His fortuitous decision to remain in the city would shape his future career path as a conductor, rather than as a composer. On August 29, the very day of Borchard’s funeral, Celibidache conducted the Philharmonic for the first time. While Bitter is usually credited with finding Celibidache to lead the Philharmonic, it was actually violinist Hermann Bethmann, who had studied with Celibidache at the Hochschule für Musik, who recommended “Celi” (as he would quickly be nicknamed) to lead the orchestra.[50] To the Americans, Celibidache appeared to be the perfect fit for the Philharmonic: he had lived in Berlin since 1936, but had not been a Nazi Party member nor had he served in the Wehrmacht. Apart from these qualifications, he was young, energetic, and non-German. By installing a foreigner as principal conductor of the Philharmonic, American authorities hoped to dispel any lingering Nazi claims of German cultural superiority once and for all.[51]

Ultimately, one might wonder why Philharmonic musicians and management accepted American occupation policies within Germany’s cultural sphere. Undoubtedly, the lengthy denazification process that lasted from 1945 until 1947 was one indisputable reason why German musicians acquiesced to American restrictions. Although Nazi Party membership had not been rampant within the Berlin Philharmonic, each musician still needed to obtain American approval to continuing working in or obtain ration cards for the American sector. It is estimated that around 10 of the 110 musicians in the Berlin Philharmonic were members of the Nazi Party. By comparison, 45 of the Vienna Philharmonic’s 117 musicians had been party members.[52] This disparity did not go unnoticed, as Bitter admitted in an April 1947 report, “In contrast to the Berlin Philharmonic, the Vienna Philharmonic has always gotten away with murder in its prodigal use of Nazi members.”[53] Party members in the Vienna Philharmonic faced few consequences as Austria had already been declared the “first victim” of National Socialism.

The ICD did fire six Berlin Philharmonic musicians for their Nazi Party membership, most notably violinist Joseph Stöhr and violist Lorenz Höber in December of 1945. Höber had been responsible for many of the Philharmonic’s administrative tasks and was particularly reluctant to relinquish his position. As Music and Theater officer Edward Hogan wrote in May of 1946: “We are told that Höber, the former business manager whom we fired on order of Public Safety, still can’t get it through his head that the Americans can get rid of him even though he was hired by the city of Berlin.”[54] Both Höber and Stöhr were hired by the Russian-controlled Staatsoper in the Spring of 1946.[55] Höber, however, remained devastated over his dismissal from the Philharmonic, an ensemble to which he had dedicated half of his life; he died shortly thereafter on December 1, 1947.[56] Several other musicians fired by the Americans for their party membership found work elsewhere: cellist Wolfram Kleber moved to the British-controlled Städtisches Oper Orchestra, and horn player George Hedler joined the RIAS orchestra in 1947. (This is particularly surprising as the RIAS Orchestra was founded and funded by the Americans.)[57] Violinist Alfred Graupner and double bassist Arno Burkhardt were also fired by American authorities for their Nazi Party memberships, but were rehired in 1947 when denazification was halted.[58]

The subtext of the American denazification efforts revolved around one question: When would the Philharmonic’s former conductor, Wilhelm Furtwängler, be allowed to return? Since February of 1945, Furtwängler had been living in self-imposed exile in Clarens, Switzerland. As the conductor of the Berlin Philharmonic since 1922, he led the orchestra at countless Nazi Party functions throughout the 1930s and 40s, although he was not a Nazi Party member. Despite Furtwängler’s insistence that his music could be separate from Nazi politics, his postwar reputation was severely compromised, and in February of 1946, ICD Chief Robert McClure announced Furtwängler’s blacklisting to be enforced across all zones and sectors of Germany:

It is an indisputable fact that through his activities, Furtwängler was prominently identified with Nazi Germany. By allowing himself to become a tool of the party, he lent an aura of respectability to the circle of men who are now on trial at Nuremberg for crimes against humanity. He not only held office under the Nazis, but also was an advisor to the Propaganda Ministry and lent his name to tours abroad sponsored by Goebbels. It is inconceivable that he should be allowed to occupy a leading position in Germany at a time when we are attempting to wipe out every trace of Nazism.[59]

The conductor had indeed served as Vice President of the Reichsmusikkammer, although he resigned the position in 1934 in support of Paul Hindemith, whose Mathis der Maler was deemed unfit by the National Socialists. (Apart from his RMK Vice Presidency, he also temporarily gave up his conductorship of the Berlin Philharmonic and musical directorship of the Staatsoper.)[60] But his resistance to the Nazis only lasted so long, and in the spring of 1935 Furtwängler issued a letter of apology to the regime. Although he did not resume his position as Vice President, he returned to conducting the Philharmonic at the close of April.[61] Still, contrary to McClure’s claim that Furtwängler had “lent his name to tours abroad,” it was Hans Knappertsbusch who led most of the Philharmonic’s concert tours in occupied countries,[62] although Furtwängler had toured with the Vienna Philharmonic in occupied Hungary and Czechoslovakia. He also conducted in neutral Switzerland at a concert sponsored by the National Socialists.[63]

Furtwängler’s denazification process dragged on for nearly two years, as American authorities vacillated between wanting to punish National Socialism’s most decorated conductor and still retaining his services in West Berlin. Meanwhile, the Soviets openly campaigned for Furtwängler’s return, tempting him with offers to conduct at the Staatsoper rather than waiting for American clearance to return to the Philharmonic.[64] The Russians were more than willing to overlook Furtwängler’s recent past for a chance to have him working in their sector. But Furtwängler remained steadfast; he only wanted to be reinstated to conduct his beloved Philharmonic. He knew it would be a symbolic victory if he could resume his former post rather than accepting the Soviets’ offer. So he decided to wait.

His denazification trial date was finally arranged for December of 1946. As Bitter wrote in an October 1946 report, “Furtwängler will be permitted the use of a lawyer, but for advice only. He must do all the talking himself.”[65] The conductor’s trial took place on December 11 and 17, 1946, in front of a packed hall and was led by intelligence officer Alex Vogel. Various witnesses were called, including Philharmonic clarinetist Ernst Fischer, who claimed the conductor saved his Jewish wife from deportation.[66] After four months of deliberation, on April 29, 1947, the American Military Government classified Furtwängler as a Mitläufer (follower) and placed him in Category IV, which meant he could still hold a leadership position and return to the Philharmonic.[67]

Ultimately, Furtwängler’s crime was not that he was a fascist, but rather that he failed to or did not want to recognize the dangerously politicized role the Philharmonic had taken on during the Third Reich. Although Furtwängler claimed to have found the Nazis’ cultural politics distasteful, they still provided a platform from which he could conduct in front of packed concert halls. And he was duly compensated for his work under the Third Reich; in 1939 alone, he made 200,000 Reichsmarks.[68]

Furtwängler was, of course, not the only famous musician to undergo postwar scrutiny; Herbert von Karajan, Eugen Jochum, Hans Knappertsbusch, Richard Strauss, Heinz Tietjen, and countless others faced denazification proceedings conducted by the Allies. Conductor Herbert von Karajan had joined the Nazi Party in 1933 while living in Salzburg, where he quickly became a rising star. (Just to make sure, he joined the Party again in 1935 when he relocated to Ulm.) Karajan, like Furtwängler, had been blacklisted by the ICD in 1945 but was reinstated in October of 1947.[69] Music officer Henry Alter, stationed in Vienna after his initial months in Berlin, admitted of the denazification of both Karajan and Furtwängler:

It was an unsolvable problem. Every person who had heard Karajan once make music knew that if one did not allow such a person to make music, one would be punishing oneself and not him. Under these conditions it was really not possible to handle Karajan in any way fairly or justly. Actually, it was similar with Furtwängler.[70]

Alter’s comments underscore the seemingly contradictory manner in which the ICD handled these denazification proceedings, as both men returned to the stage within two years of the war’s end. Ultimately, the Americans did not want to lose Karajan or Furtwängler from their zone. The ICD recognized that two of the most famous musicians in Germany would make better allies than enemies.

Despite Furtwängler’s reinstatement, the Philharmonic’s working conditions were still dire. As Bitter wrote in an August 1947 report:

The Phil is in a bad way. Five of its best first violinists have left the orchestra. In fact it is about 20 players shy of full strength. The morale is low and because of low wage scale, the coming winter, the political situation, etc. the prospects for the future are poor. However, the plans for the next season are ambitious and energetic steps are being taken to right the situation.[71]

But the situation in 1948 would prove to be even more difficult, as the Americans barred the Philharmonic from concertizing in the Soviet sector. Residing in the American sector not only required that the orchestra would be at the disposal of American and British authorities; it also meant that as the Cold War became increasingly hot, the ensemble could not openly support the Soviet’s Sozialistische Einheitspartei Deutschlands (Socialist Unity Party of Germany).[72]

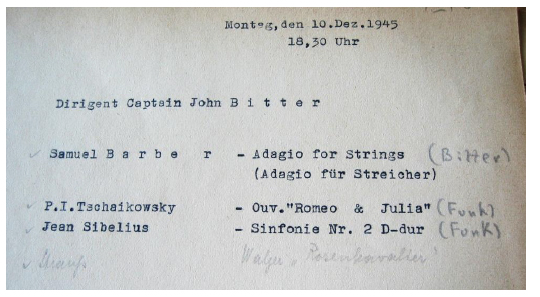

In a later interview Bitter recalled his impetus to work in postwar Germany: “I said to myself, now the war is over, now I would like to help rebuild the good Germany; that of Beethoven, Schiller, Goethe, and Brahms. One cannot always continue to conduct war.”[73] So instead he conducted the Berlin Philharmonic some thirty times during his tenure (1945–48). Bitter’s statement was somewhat disingenuous: rather than simply working with the ensemble, he was also interested in using his military connections to further his musical career by gaining valuable experience for his return to civilian life. For his first performance for American troops on December 10, 1945, he opened with John Phillip Sousa’s The Stars and Stripes Forever in a program that also included the German premiere of Samuel Barber’s Adagio for Strings (Figure 3).[74]

Note that a waltz from Strauss’s Der Rosenkavalier is penciled in at the bottom of the program, serving as the encore. Strauss, of course, was one of the very composers the ICD had planned to downplay in postwar Germany.[76]

Ultimately, the Philharmonic’s music in German postwar society was repoliticized, with the primary difference being the regime for whom they performed. Near the end of his memoir about the Berlin Philharmonic in the early postwar years, double bassist Erich Hartmann contends that the ensemble “belonged to the privileged in the Nazi era, though it was never a Nazi Orchestra.”[77] Hartmann’s observations raise far more questions than they answer, highlighting the contradictory and uncomfortable cultural politics of the postwar period. Although American authorities viewed the Philharmonic’s survival a success for American re-education efforts, the orchestra’s own role during National Socialism went unmentioned. After all, the ensemble was already in the service of another patron.

Bibliography

- Andreas-Friedrich, Ruth. Der Schattenmann: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen von Ruth Andreas-Friedrich. Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2000.

- Aster, Misha. Das Reichsorchester: Die Berliner Philharmoniker und der Nationalsozialismus. Munich: Siedler, 2007.

- Chamberlain, Brewster. Kultur auf Trümmern: Berliner Berichte der amerikanischen Information Control Section Juli-Dezember 1945. Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1979. http://dx.doi.org/10.1524/9783486703412

- Eickhoff, Thomas. Politische Dimensionen einer Komponisten – Biographie im 20. Jahrhundert – Gottfried von Einem. Stuttgart: Steiner, 1998.

- Forck, Gerhard, ed. Variationen mit Orchester: 125 Jahre Berliner Philharmoniker. 2 vols. Berlin: Henschel, 2007.

- Giessmar, Berta. The Baton and the Jackboot. London: H. Hamilton, 1946.

- ———. Two Worlds of Music. New York: Da Capo Press, 1975.

- Gilliam, Bryan, ed. Richard Strauss: New Perspectives on the Composer and His Work. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1992.

- Hanke, Jan-Holger. “Doch Nikolai schaut weg.” Interview with John Bitter. Junge Welt, December 17, 1990.

- Hartmann, Erich. Die Berliner Philharmoniker in der Stunde Null: Erinnerungen an die Zeit des Untergangs der alten Philharmonie vor 50 Jahren. Berlin: Werner Feja, 1996.

- Hell, Julia, and Andreas Schönle, eds. Ruins of Modernity. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010. http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9780822390749

- Janik, Elizabeth. Recomposing German Music: Political and Musical Tradition in Cold War Berlin. Leiden: Brill, 2005.

- Judt, Tony. Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945. New York: Penguin Books, 2005.

- Kater, Michael. The Twisted Muse: Musicians and Their Music in the Third Reich. New York: Oxford University Press, 1997. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195096200.001.0001

- Lang, Klaus. Celibidache und Furtwängler: Der große philharmonische Konflikt in der Berliner Nachkriegszeit, Celibidachiana II. Augsburg: Wissner, 2010.

- Lansch, Enrique Sánchez. Das Reichsorchester. Leipzig: Arthaus Musik, 2008. DVD.

- Lepenies, Wolf. “Eine (fast) alltägliche deutsche Geschichte.” Foreword to Das Reichsorchester: Die Berliner Philharmoniker und der Nationalsozialismus, by Misha Aster, 9–26. Munich: Siedler, 2007.

- Levi, Erik. Music in the Third Reich. Basingstoke: St. Martin’s Press, 1994.

- Monod, David. Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans 1945–1954. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005.

- Muck, Peter. Einhundert Jahre Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester: Zweiter Band: 1922–1982. Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1982.

- Painter, Karen. Symphonic Aspirations: German Music and Politics, 1900–1945. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

- Potter, Pamela. “The Nazi ‘Seizure’ of the Berlin Philharmonic or the Decline of a Bourgeois Musical Institution.” In National Socialist Cultural Policy, edited by Glenn R. Cuomo. New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1995.

- ———. “Strauss and the National Socialists: The Debate and Its Relevance.” In Richard Strauss: New Perspectives on the Composer and His Work, edited by Bryan Gilliam, 93–113. Durham: Duke University Press, 1992.

- ––––––. “What is ‘Nazi Music’?.” Musical Quarterly 88, no. 3 (2005): 428–55.

- Rentschler, Eric. “The Place of Rubble in the Trümmerfilm.” In The Ruins of Modernity, edited by Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle, 418–38. Durham: Duke University Press, 2010.

- Ross, Alex. The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century. New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2007.

- Schivelbusch, Wolfgang. In a Cold Crater: Cultural and Intellectual Life in Berlin 1945–1948. Translated by Kelly Barry. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

- Steege, Paul. Black Market, Cold War: Everyday Life in Berlin 1946–1949. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007.

- Stähr, Susanne. “Die Ära Furtwängler, das Dritte Reich und der Krieg.” In Gerhard Forck, Variationen mit Orchester: 125 Jahre Berliner Philharmoniker, vol. 1, 156. Berlin: Henschel, 2007.

- Steinweis, Alan. Art, Ideology, and Economics: The Reich Chambers of Music, Theater and the Visual Arts. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993.

- Strässner, Matthias. Der Dirigent Leo Borchard: Eine unvollendete Karriere. Berlin: Transit Buchverlag, 1999.

- Thacker, Toby. Music after Hitler, 1945–1955. Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2007.

- ———. “Playing Beethoven like an Indian.” In The Postwar Challenge: Cultural, Social, and Political Change in Western Europe, 1945–58, edited by Dominick Geppert. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003.

- Trümpi, Fritz. Politisierte Orchester: Die Wiener Philharmoniker und das Berliner Philharmonische Orchester im Nationalsozialismus. Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2011.

- Zuckermann, Solly. From Apes to Warlords: The Autobiography of Solly Zuckermann, 1904–1946. New York: Harper & Row, 1978.

Archival Resources

- Berlin Philharmonic Archive, Staatliches Institut für Musikforschung. Berlin, Germany.

- Landesarchiv, B Rep. 036-038. Eichborndamm 115. Berlin, Germany.

- National Archives and Records Administration II (NARA II). RG 260: Records of the Office of Military Government, United States (OMGUS), National Archives II at College Park, MD.

Notes

The quotation is taken from Erich Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker in der Stunde Null: Erinnerungen an die Zeit des Untergangs der alten Philharmonie vor 50 Jahren (Berlin: Werner Feja, 1996), 49–50.

For more on the destruction wrought by Allied bombing, see Paul Steege, Black Market, Cold War: Everyday Life in Berlin, 1946–1949 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 20; Tony Judt, Postwar: A History of Europe since 1945 (New York: Penguin Books, 2005), 13–40; Eric Rentschler, “The Place of Rubble in the Trümmerfilm,” in The Ruins of Modernity, eds. Julia Hell and Andreas Schönle (Durham: Duke University Press, 2010), 418–38, http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/9780822390749-024; Brewster Chamberlain, Kultur auf Trümmern: Berliner Berichte der amerikanischen Information Control Section, Juli–Dezember 1945 (Stuttgart: Deutsche Verlags-Anstalt, 1979), 1–20, http://dx.doi.org/10.1524/9783486703412.fm; and Wolfgang Schivelbusch, In a Cold Crater: Cultural and Intellectual Life in Berlin 1945–1948, trans. Kelly Barry (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998), 20–48.

Benno Frank, “Theater and Music as a Principle Part of Re-orientation in Germany,” September 16, 1947,

RG 260, Box 241, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division (E&CR): Records Relating to Music and Theater, National Archives and Records Administration II. Hereafter abbreviated NARA II.

Early military government documents outlining cultural re-education plans made no secret of the fact that American authorities hoped to wage a kind of cultural warfare by promoting American cultural achievements. Music and theater officer John Bitter admitted, “The reorientation of German cultural life is an important part of the War Department’s policy towards present day Germany. No factor can be healthier or more stabilizing than a vital readjustment of the theatre and music world enabling new plays and music, particularly American, to be presented freely and according to the finest tradition.” In “Travel Orders for Prominent Artists,” April 8, 1947, RG 260, Box 238, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division: Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

I am grateful to Berlin Philharmonic archivists Franziska Gulde-Druet and Claudia Mohr for sharing this unpublished list of concerts.

Gerhard Forck, ed., Variationen mit Orchester: 125 Jahre Berliner Philharmoniker (Berlin: Henschel, 2007), 2:20, 43.

In 1931, the city even merged the Berlin Symphony Orchestra with the Philharmonic in order to reallocate additional funds. Unfortunately, the additional funds were not enough to sustain the Philharmonic. Pamela Potter, “The Nazi ‘Seizure’ of the Berlin Philharmonic,” in National Socialist Cultural Policy, ed. Glenn Cuomo (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 2005), 42–47.

Although Strauss’s relationship to the Nazi Regime has long been maligned, he was also greatly concerned with protecting his Jewish daughter-in-law and his two grandsons. Goebbels eventually fired him in 1935 when the Gestapo intercepted Strauss’s letter to his librettist, Stephan Zweig, in which Strauss wrote he was merely “play-acting” as Reichsmusikkammer president. For more, see Michael Kater, The Twisted Muse: Musicians and Their Music in the Third Reich (New York: Oxford University Press, 1997), 18–21, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/acprof:oso/9780195096200.001.0001; Erik Levi, Music in the Third Reich (Basingstoke: St. Martin’s Press, 1994), 30–31; and Pamela Potter, “Strauss and the National Socialists: The Debate and Its Relevance,” in Richard Strauss: New Perspectives on the Composer and His Work, ed. Bryan Gilliam (Durham: Duke University Press, 1992), 93–113.

See Potter, “Nazi ‘Seizure,’” 58; and Misha Aster, Das Reichsorchester: Die Berliner Philharmoniker und der Nationalsozialismus (Munich: Siedler, 2007), 181–234. Aster writes that at the August 1936 Parteitage in Nuremburg, in one day alone, the Philharmonic managed to play for a larger audience than had comprised their entire previous season.

Wolf Lepenies, “Eine (fast) alltägliche deutsche Geschichte,” foreword to Das Reichsorchester: Die Berliner Philharmoniker und der Nationalsozialismus, by Misha Aster (Munich: Siedler, 2007), 19. Philharmonic members earned ten percent more than any other musicians in Germany. See also Potter, “Nazi ‘Seizure,’” 58.

Approximately ten Philharmonic musicians were casualties of the war, killed either by bombing raids or during voluntary military service. Aster, Das Reichsorchester, 327.

Although the musicians were not openly dismissed, the Propaganda Ministry placed increasing pressure on the Philharmonic management and Furtwängler to “aryanize” the orchestra. In a 1985 interview, Elizabeth Furtwängler, the conductor’s second wife, vehemently denied that it was the orchestra’s decision to force out its Jewish members. Ultimately, none of the Jewish musicians who had left the Berlin Philharmonic would resume their positions in the postwar period, although Joseph Schuster did return as a guest artist for Dvořák’s Cello Concerto in 1963. For more information, see Aster, Das Reichsorchester, 95, 99–104; Klaus Lang, Celibidache und Furtwängler: Der groβe philharmonische Konflikt in der Berliner Nachkriegszeit (Augsburg: Wissner, 2010), 53; Enrique Sánchez Lansch, Das Reichsorchester, DVD. Lepizig: Arthaus Musik, 2008; and Boris Schwarz, “Goldberg, Szymon,” in Grove Music Online. Oxford Music Online, accessed August 1, 2011, http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.

Berta Giessmar, Two Worlds of Music (New York: Da Capo Press, 1975); and Giessmar, The Baton and the Jackboot (London: H. Hamilton, 1946).

“In an air raid, all listeners must adjourn to the coat rooms and breezeways located on the ground floor.” Concert Program from June 27, 1943, B 30 1942/43, Courtesy of the Berlin Philharmonic Archive.

Prior to the hall’s destruction, the ensemble concertized in a converted roller-skating rink located at 21 Bernburger Strasse, not far from the Philharmonic’s home today at Potsdamer Platz. Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker, 16–17.

German concert life continued even as opera houses in Berlin, Munich, Dresden, Leipzig, Frankfurt, and Hamburg were destroyed; the frequency of performances began to slow only with Goebbels’ August 1944 declaration of “total war.” See Kater, Twisted Muse, 1–42, 200; Levi, Music in the Third Reich; 130–82; and Alan Steinweis, Art, Ideology, and Economics: The Reich Chambers of Music, Theater and the Visual Arts (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1993), 32–69.

Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker, 27–28, and Aster, Das Reichsorchester, 326. There are some discrepancies concerning when the last concert before the Zusammenbruch (“Collapse”) took place; a 1956 pamphlet produced by the Philharmonic, “Das Berliner Philharmonische Orchester nach dem zweiten Weltkrieg” gives April 8, 1945 as the date of the final concert. The Philharmonic Online Archive does not list the concert at all, and shows only a concert on March 19 as the final performance (http://www.berliner-philharmoniker.de/konzerte/kalender/von/1944-08/). Potter (“Nazi ‘Seizure,’” 58) lists the final performance, “a concert for Mr. Speer,” as occurring on April 11.

David Monod, Settling Scores: German Music, Denazification, and the Americans 1945–1954 (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2005), 128.

The soloists that evening were violinist Siegfried Borries and cellist Tibor de Machula.

Thomas Eickhoff, Politischen Dimensionen einer Komponisten-Biographie im 20.Jahrhundert-Gottfried von Einem (Stuttgart: Steiner, 1998), 76. See also Matthias Strässner, Der Dirigent Leo Borchard: Eine unvollendete Karriere (Berlin: Transit Buchverlag, 1999), 213. Although the Philharmonic would become an American-licensed ensemble, the Soviets had control of the entire city until early July.

For an eyewitness account of the first postwar concert, see Peter Muck, Einhundert Jahre Berliner Philharmonisches Orchester, Zweiter Band: 1922–1982 (Tutzing: Hans Schneider, 1982), 190.

Solly Zuckermann, From Apes to Warlords: The Autobiography (1904–1946) of Solly Zuckerman (London: Hamish Hamilton, 1978), 192.

Berlin was divided according to the agreement made at the Yalta Conference in February 1945, and once the other Allies arrived, the Soviets receded to their own sector of the city.

It was standard practice for the Americans to seize theaters throughout occupied Germany; according to Circular 120, Headquarters, U.S. Forces, European Theater, “In localities where only one such facility exists in useful condition, a sharing of time between troops and civilians will be arranged.” Quoted in J.H. Hills, “Use of Deutsches Theater, Wiesbaden,” January 4, 1946, RG 260, Box 134, Records of the Information Control Division (ICD): Central Decimal File of the Executive Office, 1944-49, NARA II.

“Application for Employment, John Bitter,” June 25, 1949, RG 260, Box 18, Records of the Education and Cultural Relations Division, NARA II.

Monod, Settling Scores, 13, 38. In the 1930s, Bitter conducted the Jacksonville Orchestra, the Florida Federal Orchestra, and the Miami Symphony Orchestra.

For more on this misconception, see Pamela Potter, “What is ‘Nazi Music’?,” Musical Quarterly 88, no. 3 (2005): 428–55, http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/musqtl/gdi019.

John Bitter, “Theater and Music Weekly Report,” RG 260, Box 239, Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch, Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

The matter of where the Philharmonic would reside was not decided until 1946; the British also hoped to woo the orchestra into making Charlottenburg’s Theater des Westens their home. Strässner, Der Dirigent Leo Borchard, 230.

“Discontinuance of Information Control Registration of Actors, Performers, Musicians, and Certain Other Persons,” May 27, 1947, RG 260, Box 238, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division: Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

Jan-Holger Hanke, “Doch Nikolai schaut weg.” Interview with John Bitter, Junge Welt, December 17, 1990.

Toby Thacker, “Playing Beethoven like an Indian,” in The Postwar Challenge: Cultural, Social, and Political Change in Western Europe, 1945–58, ed. Dominick Geppert (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2003), 369–71; and Alex Ross, The Rest is Noise: Listening to the Twentieth Century (New York: Farrar, Straus, and Giroux, 2007), 349.

“Weekly Reports,” Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch. Records Relating to Music and Theater. RG 260, Box 239, and “Music Material of the Berlin Philharmonic,” April 10, 1946, Records of the Education and Cultural Relations Division. Bavaria: The Music Section, 1945-49. RG 260, Box 19. In his May 23, 1946, report, Berlin music officer Edward Hogan remarks of the Philharmonic’s busy schedule, not without a touch of sarcasm: “It was a particularly strenuous weekend for the band.”

“Ebenso fielen die Instrumente, die in den Kellern der alten Philharmonie das Bombenfeuer überstanden hatten, den Feinden als Beute in die Hände und wurden nach Osten mitgenommen.” Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker, 34.

John Bitter, “16–30 November 1947,” National Archives Records: Shipment 4, Box 8-1, Folder 2, May 1946 to November 1948, B Rep. 036 Nr. 4/8-1/2, Landesarchiv, Berlin.

Ruth Andreas-Friedrich, Der Schattenmann: Tagebuchaufzeichnungen von Ruth Andreas–Friedrich (Berlin: Suhrkamp, 2000), 291.

According to initial American denazification policies, Berlin’s orchestral conductors, soloists, and managers were not considered “ordinary labor,” and were therefore held to a higher denazification standard. In practice, however, the Americans would soon realize that it was precisely the leaders of these organizations who were the most compromised. Eric Clarke, “Military Government Regulation 23.331-Section 2-d, Ordinary Labor,” May 21, 1946, RG 260, Box 237, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division: Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II. See also Toby Thacker, Music after Hitler, 1945–1955 (Hampshire: Ashgate Publishing, 2007), 51–63.

See Monod, Settling Scores, 38; and Hartmann, Die Berliner Philharmoniker, 42–45.

One of the primary goals of the reorientation program in Germany was to broaden the range of musical activity, and “to increase respect for cultural attainments of other nations.” In “Directive on United States Objectives and Basic Policy in Germany,” July 15, 1947, RG 260, Box 133, Records of the Information Control Division, Central Decimal File of the Executive Office, NARA II.

Fritz Trümpi, Politisierte Orchester: Die Wiener Philharmoniker und das Berliner Philharmonische Orchester im Nationalsozialismus (Vienna: Böhlau Verlag, 2011), 113; Judt, Postwar, 52; and Lepenies, “Eine (fast) alltägliche deutsche Geschichte,” 18.

John Bitter, “Weekly Theater and Music Report, 30 April 1947,” RG 260, Box 241, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division (E&CR): Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

Edward Hogan, “Weekly Report,” May 23, 1946, RG 260, Box 239, Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch, Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

Walter Hinrichsen, “Members of the Philharmonic Orchestra Berlin being discharged in Accordance with Denazification Policy in the U.S. Zone,” June 25, 1946, RG 260, Box 237, Records of the Education and Cultural Affairs Division: Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II.

Forck, Variationen mit Orchester, 2:54. The Americans then appointed Paul Schrör and Ernst Fuhr as the new managers or Geschäftsführung of the Philharmonic. The following year, the Philharmonic decided to replace Schrör with Richard Wolff, as Wolff was a senior orchestra member. John Bitter, “Theater and Music Weekly Report,” November 20, 1946, RG 260, Box 239, Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch, Records Relating to Music and Theater, NARA II. See also Lang, Celibidache und Furtwängler, 77; and Muck, Einhundert Jahre, 205.

Robert McClure, “For Release February 21, 1946,” RG 260, Box 43, Records of the Information Control Division (ICD): Records of Division Headquarters, 1945-49, NARA II.

Susanne Stähr, “Die Ära Furtwängler, das Dritte Reich und der Krieg,” in Forck, Variationen mit Orchester, 1:156. Stähr claims Hitler forbade Furtwängler to travel outside of Germany (Ausreiseverbot) shortly before Christmas in 1934.

Karen Painter, Symphonic Aspirations: German Music and Politics, 1900–1945 (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007), 209–220; Levi, Music in the Third Reich, 112–13; Stähr, “Die Ära Furtwängler,” 1:159.

Elizabeth Janik, Recomposing German Music: Political and Musical Tradition in Cold War Berlin (Leiden: Brill, 2005), 134–39.

John Bitter, “Theater and Munich Report,” October 24, 1946, RG 260, Box 239, Records of the Education and Cultural Resources Branch, NARA II.

Interview with Henry Alter conducted by Brewster Chamberlain and Jürgen Wetzel, May 11, 1981. B Rep. 037, Nr. 79-82, Landesarchiv, Berlin.

John Bitter, “August 15–31, 1947 Report,” National Archives Records: Shipment 4, Box 8-1, Folder 2, May 1946 to November 1948, B Rep. 036, Nr. 4/8-1/2, Landesarchiv, Berlin.

John Bitter, interview by Brewster Chamberlain and Jürgen Wetzel, November 6, 1981, B Rep. 037, Nr. 79-82, Landesarchiv, Berlin.

Henry Alter, interview by Brewster Chamberlain and Jürgen Wetzel, May 11, 1981, B Rep. 037, Nr. 79-82, Landesarchiv, Berlin. I am grateful to Professor Steven Whiting for pointing out the elegiac connotations of Barber’s Adagio in relation to Toscanini’s radio broadcast marking Franklin Delano Roosevelt’s death. Whether Bitter had this performance in mind when he selected Adagio is unknown.

P 1945 XII 10, Berlin Philharmonic Archive. The Tchaikovsky and Sibelius selections were broadcast by Soviet-controlled Berlin Radio, as indicated by the marginal annotations “Funk” (Radio).

In the earliest American music control document from June of 1945, the ICD admitted, “We cannot ban performances containing works by Richard Strauss or Hans Pfitzner. We should, however, not allow such composers to be ‘built up’ by special concerts devoted entirely to their works or conducted by them.” In “Draft Guidance on the Control of Music,” June 8, 1945, RG 260, Box 134, Records of the Information Control Division (ICD): Central Decimal File of the Executive Office, 1944-49, NARA II.