Acoustic Palimpsests and the Politics of Listening

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

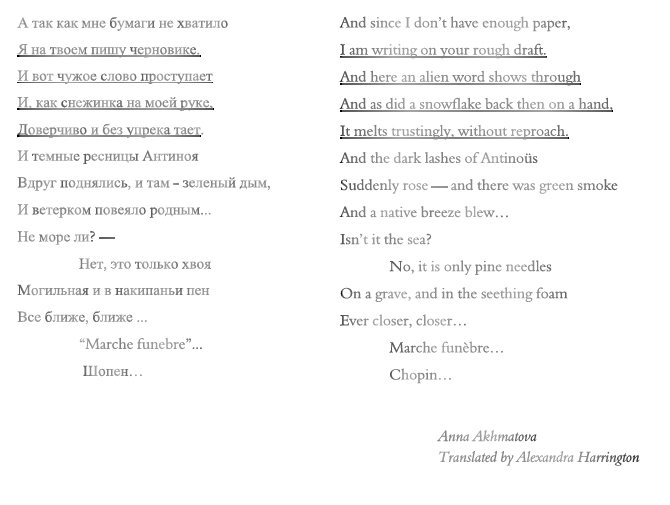

Layer 1: Oldest Substrate

(the poem that inspired this essay)

Layer 2: Substrate

(draft introduction, scratched out in favor of more formal introduction below)[1]

Layer 3: Substrate

(introduction, written October 2009 for oral presentation at the annual meeting of the Society for Ethnomusicology, before work on article commenced)

The word “theory,” it is often noted, derives from the Greek theorein, meaning to look at or see. The convention is to say that theories give us new ways of seeing the world. Given the academy’s current interest in intersensoriality and synaesthesia, I’m sure no one will object to us extending theory’s purview further into the sensorium: theories, we can comfortably say, give us new ways of seeing, hearing, sensing the world. If this is so, then metaphors, I would like to argue, are theories in miniature, in utero even—and as such operate on a less expansive, tactical plane, opening small, ephemeral, but at times valuable, discursive spaces in which we can think and sense the world anew. Of course, we could also define the downside of theory and metaphor by rendering explicit the obvious corollary: in providing a new way of sensing the world, a theory simultaneously occludes, if only temporarily, alternative ways of sensing the world. Metaphors, it would stand to reason, do the same thing, but less expansively, less violently. In this presentation, I’m interested in focusing on a metaphor that lays bare the layered nature of sonorous objects and auditory experience. No, that’s not quite right, scratch that: I’m interested in using a metaphor to help us imagine sonorous objects and auditory experience as layered. This thought experiment asks if the palimpsest—a venerable (although some might say threadbare) source for metaphorical play—can be recalibrated (or “wired for sound”) in order to point us toward a politics of listening that is both hermeneutically rich and deeply complementary to the ethnographic project. It proposes the palimpsest as a platform for undertaking a kind of reverse engineering of musical texts and listening activities. It positions the palimpsest as a structured micromethodology for thick description—a way to achieve interpretive thickness by uncovering the moments of inscription and erasure that lie beneath acoustic phenomena and auditory practices. Unlike the music philologist peering through editorial layers in search of the musical urtext, the “palimpsestuous” scholar is enthralled equally by each layer and each accretion, and by the gestalt effect of layeredness as well.[2]

I begin by dwelling briefly on palimpsests proper and then experiment with several ways of translating the concept of the palimpsest into auditory terms. Before I commence, though, let me say this: I am aware that this project may strike some of you as paradoxical, anachronistic, or even slightly perverse. In the early twenty-first century, many of us are more inclined to think of sound as always-in-motion than we are to think of it as a stationary object (which is, one might argue, what a textual palimpsest is at its base). Decades after the decline of structuralism, the notion that sound is layered, and therefore in some general sense, fixed, feels less intuitive than the notion that sound is a dynamic force, a vibration that can “penetrate and permeate, so effortlessly becom[ing] the soft catastrophe of space” (Connor [2005] 2011, 133). Indeed, my own intellectual proclivities have tended to bend in the direction of flux. So why then am I tethering sound to a metaphor that appears to privilege textuality, and with it, stasis? In defense of this humble thought experiment, I’ll say two things. First, as I hope to demonstrate, palimpsests are less like stable objects and more like fluid processes than other texts. Second, and more fundamentally, while I am conscious of its drawbacks (several of which I discuss at the conclusion of this article), I find that the metaphor of the acoustic palimpsest simply works for me. By this I mean that it is performing some work for me; it works within the context of my work—which is, in the end, all one can ask of a metaphor.

You may know that the original palimpsests were previously inscribed sheets of vellum or other types of parchment that were reinscribed after the original writing had been erased. In the early medieval period, the original text was washed away with a mixture of milk and oat bran or scraped clean by medieval scribes using pumice dust. This practice was largely the result of the economics of the period: the value of vellum as a commodity often exceeded the economic or symbolic value of what was written upon it. With a large manuscript such as the bible requiring the skins of 250 sheep, it is not at all surprising that trade in used pages was brisk throughout the literate world in the centuries preceding the industrial production of paper (Mathisen 2008, 148). At the same time, some have suggested that “another motive may have been directed by the desire of Church officials to ‘convert’ pagan Greek script by overlaying it with the word of God.”[3] I would like to keep both of these potential justifications—the pragmatic and the ideological—hovering in the background as we move forward.

Over the centuries, as the result of oxidation and other natural processes, the original texts often began to reappear beneath the newer writing. This fact made it possible for scholars of the palimpsest to engage in a kind of textual archaeology: ignoring the most recent layer, they peered back into the past, straining to read the words that had been effectively buried. In Latin these faint textual ghosts were called the scriptio inferior (underwriting) or scriptio anterior (former writing). The palimpsest is thus the result of successive acts of partial erasure and inscription, acts that turn it into a “multilayered record,” (Oxford English Dictionary) a trace of multiple histories and multiple authors.

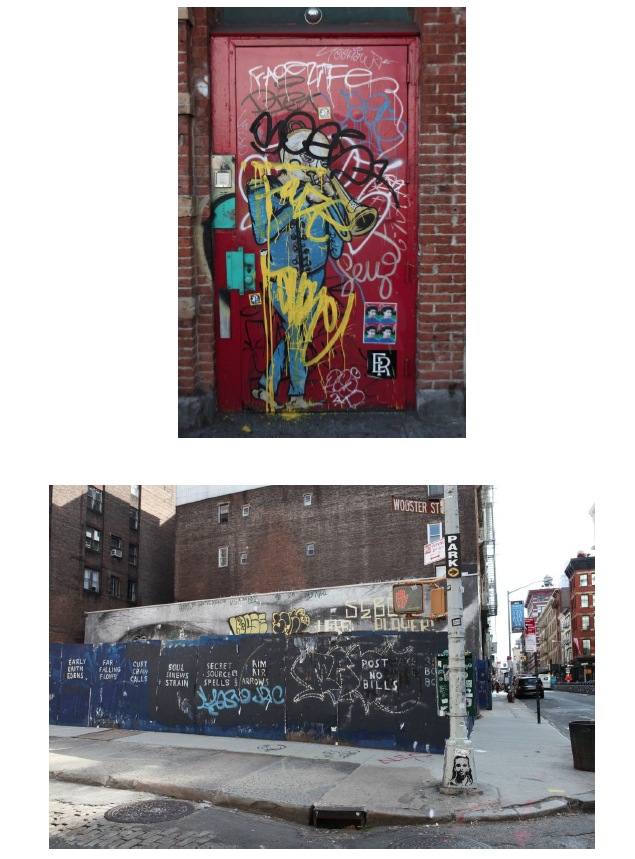

In the late nineteenth and twentieth centuries, along with the development of new chemical techniques for uncovering the scriptio inferior and the widely publicized recovery of a number of historically important “lost” texts (McDonagh 1987, 210), the palimpsest emerged as a rich, interdisciplinary metaphor for the fundamentally interconnected, multiply situated, discursive nature of human experience. The acts of partial erasure and writing-upon-writing that the palimpsest presumes have inspired a vast tropology revolving around themes of temporality, memory, intertextuality, and power. For English author Thomas De Quincey (1845), the palimpsest was a textual model of human consciousness, which he imagined as a multilayered neural archive of experiences.[4] (“Such a palimpsest is my brain; such a palimpsest, O reader! is yours.”) For Freud (1925), the palimpsest, or at least its structural equivalent, provides a model for the mechanism of memory, and the relationship between conscious perception and the unconscious.[5] For Russian poet Anna Akhmatova (1941–66), the author of this essay’s epigraph, the palimpsest represents the anxiety and intimacy of poetic influence.[6] For Andreas Huyssen (2003), architectural palimpsests—the visible residue of buildings that have since been razed—provide a theoretical model for reading urban spaces intertextually and recovering “present pasts” from the abyss of cultural amnesia. And for scores of street artists in my New York neighborhood, the palimpsest is the model for a radically democratic method of collaborative artistic creation, in which one artist’s work becomes a colorful canvas for someone else the next day.

Closer to home for scholars of aurality, Tom Porcello’s influential (1998) discussion of social phenomenology in and around the recording studio draws upon the palimpsest’s twentieth-century equivalent, the reel-to-reel tape, to provide new and complementary language for questioning the nature of the musical text and discussing the varied ways in which we experience temporality in music. His discussion focuses on the phenomenon of “print-through,” the ghostly pre- or post-echo of musical material that has been inadvertently “transferred through adjacent layers when [analog audio] tape is wound on a reel” (485). As a recording engineer, Porcello recognized print-through as a technical problem to be avoided by winding the reel “tails-out,” so that “the worst print-through comes as a post-echo and stands the greatest possibility of being masked by the program itself” (Woram 1982; quoted in Porcello 1998, 485). At the same time, as a music listener, Porcello often appreciated print-through for its ability to generate a Barthian “plaisir du texte,” an erotic “striptease” or partial presentation of the musical gesture that is to come. Drawing on these and other experiences, Porcello deploys print-through as a metaphor (1) to question the status of the musical text; (2) to “elasticiz[e] the boundaries drawn around standard conceptions of encounters with music”; and (3) to illuminate “cumulative listening experiences engendered in the mediated social spaces of musical encounter” (485–6). He also regards the act of multitrack recording more generally as structurally similar to the layering of discourses, subject positions, and identities that occurs in social interactions (488).

In a different but complementary vein, Nina Eidsheim deploys the palimpsest trope in describing the ways in which the embodied practice of singing inscribes “narratives of the body, race, class, vocal genres and practices” into “the musculature of the body” (209–10), as well as the ways that listeners hear voices—and vocal timbre specifically—in relation to all of the voices they have previously heard (212). Following the logic of Derrida’s (1976, 158) maxim that “there is nothing outside the text,” she asks her readers to consider the activity of singing as itself a type of inscription, a type of writing, and therefore, “a palimpsest, a constant re-writing over a prior document that may never be entirely erased . . . a struggle for power”:

If the activity of singing is conceived as inscription on an imperfectly erased canvas, writing in the midst of narratives of the body, race, class, vocal genres and practices, then the sound of singing becomes the sound, and the echo, of that fragmented palimpsest. In the case of the voice, those narratives are also inscribed into the musculature of the body, and thus the fragments are sounded as a coherent whole. (209)

Eidsheim’s corporeal palimpsest provides a model for listening to voices as the result of complex histories, for hearing history—and therefore politics—within the voice’s grain. It asks us to imagine the totality of the voice as comprised of multiple fragments, multiple layers.

Indeed, within music scholarship, as within the humanities more broadly, the palimpsest has come to figure as a capacious metaphor for all types of intertextuality, intermediality, layered history and embodiment. Thus does Richard Leppert (1995, xxvi) refer to “the body as a palimpsest in musical practices”; or Donald Grieg (2003) examine “Ars Subtilior repertory as performance palimpsest”; or Eliot Bates (2004, 284-6) present “an alternative history [of electronic music] structured like a palimpsest, where elements never disappear but are constantly overlaid.” More expansively, Serge Lacasse (2003) has adapted Gérard Genette’s model for discussing intertextuality (found in Genette’s seminal volume Palimpsests) to the purposes of popular music analysis. Lacasse’s “recorded palimpsest” points to the various relationships between recordings and other previous or co-present texts that can be found within the seemingly autonomous object of the record. From the cover to the sample to the parody to the pastiche, these implicit or explicit intertextual relationships are so fundamental to popular music as to constitute one of its enabling conditions.

In this essay I draw upon—in the palimpsestic sense of that phrase—the aforementioned work in an attempt to flesh out a general concept of “acoustic palimpsest.” I use this neologism to foreground the multiple acts of erasure, effacement, occupation, displacement, collaboration, and reinscription that are embedded in music composition, performance, and recording, as well as in acoustic experience more broadly. Like the hidden scriptio anterior that is revealed by ultraviolet imaging and confocal microscopy, these acts can be recovered—partially, imperfectly, but valuably—by critical listening, research, and occasional leaps of the imagination. The importance of the imaginative leap as a research method and rhetorical strategy has gone largely unacknowledged within the social sciences until recently. But as Avery Gordon reminds us:

It is essential to see the things and the people who are primarily unseen and banished to the periphery of our social graciousness. At a minimum it is essential because they see you and address you. They have, as Gayatri Spivak remarked, a strategy towards you. Absent, neglected, ghostly: it is essential to imagine their life worlds because you have no other choice but to make things up in the interstices of the factual and the fabulous, the place where the shadow and the act converge. (2008, 196–7)

I want to perform a similar operation—not “to see things . . . unseen” but to hear things unheard, and barely heard. To imagine the unheard as the barely heard and strain to listen past the acoustic foreground down to the ghostly echo, the faint trace of obscured selves that lie on or just beyond the periphery of audibility.

Layer 4: Substrate

(Body, expanded version of oral presentation, written June 2010, revised 2013 for Music and Politics)

What exactly is an acoustic palimpsest, other than an oxymoron? How can a mutely layered text be twisted into a sound-centered metaphor? My hope is that, like a palimpsest itself, my metaphor will emerge through a slow process of layering, an accrual of stories that I initiate and that, if it is to be remotely successful, others will continue. I present below three stories, each of which describes a situation in which the acoustic palimpsest metaphor strikes me as apt. The first two are quite brief; the third, which builds upon details discussed in the first two, is somewhat longer. These examples come directly from research projects that I’m actively working on. My suspicion is that, if I worked on other projects, other equally powerful examples would be brought to my attention.

1. Layered listening

In all but the most clinical of circumstances, we are confronted by sounds that emanate from multiple sources. Most music scholarship resolutely ignores the scrim of ambient sounds that accompanies the vast majority of music listening experiences. A rare exception is the work of David Beer, who, in a recent article on iPods and the “urban mise-en-scène,” argues that the increasingly common practice of listening to MP3 players in noisy urban spaces does not result in the creation of a “privatized auditory bubble” as scholars such as Michael Bull (2007) have claimed. Rather, many, if not all, of our mobile music listening practices are fundamentally layered. Beer states the obvious fact that

sound generated in [the ears of users] by the mobile music device is not the only sound they hear: they are still exposed to soundscapes of the urban territories through which they pass, and in fact, if the earphones are loud enough, may also be contributing to other people’s experiences through sound leakage. (2007, 858)

Indeed, anyone who listens to an iPod in an urban area knows that music coming through headphones cannot fully drown out the sounds of a bus engine or passing police siren. And anyone who has encountered an iPod user in an elevator knows that mobile music listening can frequently become an (inadvertently) shared experience. These moments of layered listening are easy to disregard because they are ubiquitous, ephemeral, largely unconscious and relatively benign. In other situations, however, the layering of sonic material is a phenomenon of far greater consequence. In my ongoing research on the sonic dimension of the Iraq war,[7] for example, I frequently encounter talk about the layers of sound through which military service members deployed in urban areas learned to listen for the all-important sounds of shots being fired. As an Air Force Major who was stationed in Iraq once described it to me, beneath the “engine sounds, transmission sounds, road noise, static over the radio . . . and ambient noises [over headphones] . . . everybody is very much in tune, listening for gunfire or rocket fire.”[8] The focal point of their aural acuity floated from one sound source to another as they scanned the acoustic environment for signs of danger and dis-ease.

While a number of military regulations prohibited listening to music on missions, these regulations were only sporadically enforced. During the early stage of the war, before the danger from improvised explosive devices became acute, service members frequently listened to music to alleviate boredom while driving from one place to another or to “amp [themselves] up” to a state of heightened readiness, hyperawareness, and aggression. When music was deployed in these situations, it was often deeply buried beneath many layers of ambient sound. Rumbling along the road in an up-armored Humvee that gave off ninety-five decibels of engine noise, bantering back and forth with one’s comrades, keeping one ear on the radio and another tuned for the possibility of gunfire or other signs of “action,” music listening could take on a kind of ethereal quality, with the tinny strains of a jury-rigged sound system providing just enough sonic cues of a familiar song for listeners to fill in the blanks in their imaginations. Frequently it would be necessary to tune out or turn off the music altogether, as a communication from the radio, or the soft sound of a ricochet against the hull of their vehicle, or another sound related to their mission commanded their attention. These were listening skills that they didn’t have when they first deployed to Iraq. It was only over time that they learned to distinguish the often-soft significant sounds from the often-loud noises that obscured them. They became, in this sense, good analogues to the historian trying to discern a discrete text from within the palimpsest: they became experts at layered listening.

In less violent situations, music listeners strive to keep the figure-ground relations intact, focusing on music and disregarding noise. As scholars of auditory experience, however, we can invoke the palimpsest metaphor to flip figure and ground, if only temporarily, in order to situate music listening within the sonorous matrix that accompanies and complicates it, and to take this matrix seriously as a rich cultural artifact in its own right. The effect of this move is to blur the line between the musical object and the sonorous world; to allow the cacophony of the world to rush into the study of music; and to place the politics of navigating through this complex and noisy world at the center of discussions of listening.

2. Music on bones

In addition to the ambient world, recording and playback technologies create their own layers of sound that inscribe themselves on top of the music they deliver. Print-through, distortion, the pops and hiss of vinyl, and the skips and clips of digital recording constitute an acoustic layer through which we have trained ourselves to listen to music. However, not all of the palimpsestic dimensions of recording technologies can be apprehended with the ears alone. I have in mind a recording practice that resulted in a musical artifact whose layers were notable for being not aurally but visually arresting: the practice in question marked the beginning of the underground recording scene in the post-war Soviet Union.

This story—as told by one of its protagonists, Boris Taigin (1999) and others (Belyi 2008; Ivanov 2008)—begins in 1946.[9] That year, a young Soviet engineer named Stanislav Filon brought a German record-cutting machine (made by the Telefunken Company) back from the front as a war trophy. Filon used the machine to start a business in Leningrad. His shop, called “Sonic Correspondence” (zvukovye pis’ma, literally “sound letters”) recorded the voices of customers onto discs made out of an industrial plastic called Detselit. However, according to Taigin, these pieces of “sonic correspondence” were not the primary product of Filon’s shop:

This was all a shell, an official cover. The main purpose for which the studio was built was to illegally produce what we called “fast-selling goods” [i.e., contraband] . . . After the end of the workday, when the studio was closed, that’s when the real work would start! Past midnight, and often all the way through till dawn, they dubbed . . . jazz music played by popular foreign orchestras, and, most importantly, tangos, foxtrots, and romances sung in Russian by emigrants of the first and second-wave emigration from Russia. (Taigin 1999, my translation)

Since Detselit phonographic blanks were relatively expensive and hard to come by, Filon and his comrades turned to other media: first to large-format photographic film, and somewhat later to used medical X-rays. Both were soft enough to allow for inscription and durable enough to withstand the stylus on Soviet record players, but the X-rays had the extra advantage of being virtually free. The archives of the city’s hospitals were always drowning in old X-rays, which they were required to burn periodically to make room for new ones. Some hospital staff members gave away the film; others sold it to Filon & Co. in bulk. And so, working with an abundant supply of recycled media that would have caused a medieval scribe, perpetually short of vellum, to salivate, the entrepreneurial Filon began to distribute recordings that looked like this:

It should come as no surprise that these musical artifacts came to be known as muzyka na rëbrakh—music on ribs—muzyka na cherepakh—music on skulls, or, most popularly, muzyka na kost’iakh—music on bones.

After a young engineer named Ruslan Bogoslovskii successfully reverse-engineered Filon’s Telefunken and started producing record-cutters of his own, the practice of music on bones began to spread rapidly. Not surprisingly, the proliferation of homemade records on the black market attracted the attention of the government. On a single day in 1950, approximately sixty underground dubbers and distributors were rounded up for questioning, and their equipment was confiscated. Bogoslovskii received a jail sentence of three years, while Taigin and one of his associates were given five years each.[10] But periodic arrests such as these, while disruptive, did not completely halt the spread of music on bones in the Soviet Union. What eventually did was the advent of new technology: the widespread availability of reel-to-reel tape recorders in the 1960s rendered the record-cutting business redundant, and X-ray records disappeared from view.

One of the striking things about these acoustic palimpsests—and one of the things that distinguishes them from the original, textual palimpsests—is that the X-ray’s visual inscription in no way impeded the reception of the phonographic track carved into it. Unlike the vellum sheet, which was initially washed clean in order to make room for new writing, these hauntingly beautiful artifacts profit from the lack of interference between the two modes of inscription layered upon them. After even a cursory glance at these records, it appears clear that the underground record cutters were at least occasionally focused on the visually ironic, palimpsestic dimension of music on bones. Take this as exhibit A: a record of Elvis Presley’s “Heartbreak Hotel” with the hole in the middle directly over the place where the heart would be in a chest X-ray:

Or look at this somewhat more obscure and mischievous pairing of sound and image: a recording labeled “Cheek to Cheek” inscribed onto a pelvic X-ray.[11]

Or this track, of Valdir Azevedo’s “Delicado,” carved into a particularly fragile-looking set of ribs:

In short, it appears that the palimpsestic dimension of music on bones was not lost on its practitioners. In the end, how could those who made or purchased these records not take delight in the fact that the music of the nascent Soviet “underground”[12] was written on images of the human skeleton, denizen of the literal Soviet underground? How could they not smile at the notion that the songs of artists who were actively censored in the Soviet Union were circulating upon official images of Soviet bodies?

I should mention at this point that these remarkable photographs were recently made by a gifted Russian musician named Igor’ Belyi, from a rare private collection passed on to the amateur archivist Piotr Trubetskoi, who is, in my opinion, Russia’s most valuable and unsung hero of music preservation. Together, Belyi and Trubetskoi documented not only the “look” of music on bones but also its sound, making mp3 recordings of each record on a 1950s-vintage Soviet turntable. As I write this, I am listening to their mp3 of a scratchy recording of Bill Haley’s 1953 classic, “Farewell, So Long, Goodbye,” inscribed onto a particularly gruesome X-ray of a broken femur.

The scraping sound of the record player’s stylus, like the scraping sound of the palimpsestic scribe’s knife, compels me to remember the means of production, the hidden actors (in recording studios, equipment shops, record stores, distribution plants—and, in this instance, X-ray labs, underground dubbing facilities, and black marketers—along with the vast networks of labor and capital exchange, and the material histories that lay beneath any modern, multiply mediated musical moment. As we listen to the record, the palimpsest metaphor calls upon us to listen to its history as well. That flimsy bootleg of Bill Haley emerged due to the prior participation of, minimally, a composer, a lyricist, performers, recording staff and technologies, studio and commercial spaces, a record consumer—and then, later, a record smuggler, Soviet X-ray film manufacturers, an X-ray technician, a patient with a broken leg, a hospital archivist, record dubbers, and an underground music market. Similarly, the CD gathering dust in your collection involves the participation of untold numbers of people, technologies, and resources (Latour 2007). In this sense, we can understand all musical materials—scores, recordings, even live performances—to be the residue of complex networks of human and nonhuman actors, of untold dialectics between far-flung people and technologies, structures and agencies. These networks are the accretions of intentional moves and historical accidents that hide beneath the musical artifact, which we are now in a position to see for what it really is: a fiction. There is no “there” there—only a spectral gestalt, an illusory projection of the artifact created by the layering effect.

3. Listening for barely audible and inaudible voices.

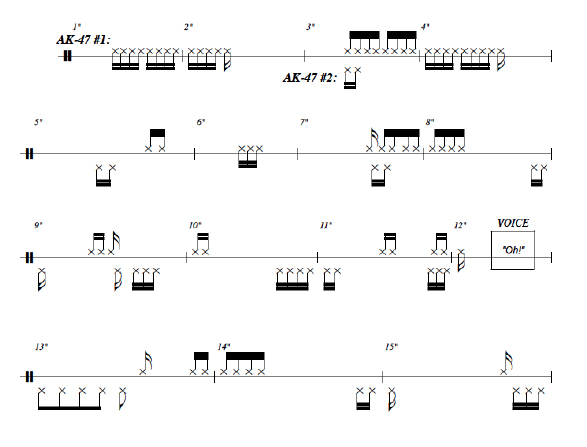

Some acoustic palimpsests, like those of the urban and wartime music listeners mentioned in my first story, are the unintentional byproducts of music listening technologies (iPods, earphones, ears) being deployed in noisy environments. Others, like music on bones, are the more-or-less random consequence of ad hoc solutions to logistical problems of supply and demand. Others still are the intentional products of creative effort: some acoustic palimpsests are, in other words, composed. I offer as an example of this last type a recording made by a man named Iurii Kirsanov, who in 1981 was a 29-year-old officer in a KGB regiment in Afghanistan, as the Soviet Union ramped up its military presence in what would emerge as their most devastating military engagement since World War II.[13] Early in their first deployment, Kirsanov and his friend Sergei Smirnov began carrying a portable cassette recorder with them when they left their base on missions. Their objective was to create a record of the ambient sounds that were most salient in their daily life, the sounds that would later remind them of their tour of duty in Afghanistan. They recorded hours of tape, capturing the call to prayer at the local mosque, the wind whipping through the Afghan mountains, and the cacophonous sounds of military action: AK-47s, helicopters, jet aircraft, rockets.

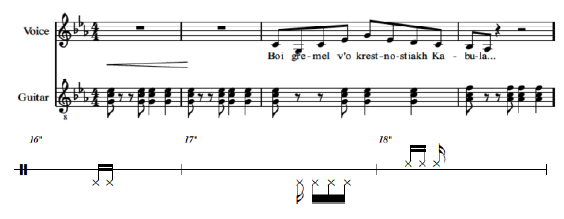

Late one night in May 1981, Kirsanov and several friends carried his guitar and three cassette recorders into the dressing room of the battalion’s steam bath. There, in the quiet, from midnight to 5:00 a.m. on two consecutive nights, they recorded an hour-length cassette of Kirsanov’s compositions. Two of the tape players were used to record identical copies of the performance; the operator of the third player held Kirsanov’s written scenario, which told him when to press “play” and “stop” on a tape of his ambient field recordings. The resultant trio—for guitar, voice, and tape recorder—amounted to an idiosyncratic evocation of Kirsanov’s personal soundscape—not to mention a composition that unwittingly replicated the techniques of musique concrète—performed and recorded in the middle of a war zone.

The recording begins abruptly with several loud bursts of AK-47 fire, which slowly fade out as Kirsanov’s guitar enters, playing a martial tango of the sort that gained popularity in the Soviet Union through the illicit post-war “music on bones” recordings discussed above. These imbricated introductory gestures, played on two very different “instruments,” precede the entrance of Kirsanov’s voice, singing a song that references the grim violence of the Afghan war:

Audio Example 1: Kirsanov: “Here, Beneath a Foreign Sky”

The introductory verse of “Here, Beneath a Foreign Sky” powerfully evokes the wartime sense of alienation, frustration, and aggression that has been common among soldiers throughout history. Interestingly for the discussion at hand, it does so in language that foregrounds sound: the audible cries of the narrator’s departing comrades fuel his desire to “drown out” (glushit’, also “silence,” “kill”) his longing with a loud and deadly burst of gunfire. Even in the absence of the ambient machine-gun track, we could begin to read the lyrics of this song as a palimpsest of sorts, one that involves an act of acoustic inscription and erasure: sound silencing sadness. But the presence of an actual recording of machine-gun fire renders this palimpsest thicker, more complicated, and significantly more chilling than it would be otherwise. To my ear, the combined effect of the song text and the ambient track, of the poetics and the ballistics that underwrite this recording, is to lend an aura of immediacy, authority, aggression, and realism to it that words and music alone could scarcely accomplish.

Kirsanov recorded the gunfire in 1980 outside Shindand, Afghanistan, and between each burst you can hear the echo of the report as it bounces off a mountain in the distance. A sense of space is embedded in that echo, and that sense follows me throughout the recording. On successive listenings, I find myself focusing less on the words, the melody, or even the gunfire—less on the phenomenal surface, if you will—and more on the stark contrast between the wide-open acoustic space of the ambient recordings and the claustrophobic, tin-can-like space of the steam bath in which Kirsanov’s voice and guitar were recorded. The different sets of echo and decay that characterize the two recording venues bespeak two different arrangements of wartime bodies: one, nestled within the relative protection of a military base; another, exposed to the vertiginous chaos of the battlefield. This audible difference, this sonic residue of resonant spaces, constitutes another layer that one can tease out of this palimpsestic recording.

I first encountered Kirsanov’s recording several years ago, around the same time that I began thinking about palimpsests. The lyrics I quoted above, combined with the rudimentary multitracking undertaken in the recording, were more than enough to prompt me to think of it in the palimpsestic terms of overwriting. More recently, however, I played Kirsanov’s tape to my friend Madina Goldberg, a professor of Russian history who grew up in the USSR. Her immediate reaction, on hearing one verse of Kirsanov’s tango, was to ask if the song was written in the 1930s or 1940s. Rather triumphantly—because I so seldom know something that she doesn’t know—I revealed that it was written in 1980. Undaunted, Goldberg insisted that she had heard the same song in a much older recording. After doing a series of online searches together, we realized that she was right: Kirsanov’s tango is indeed a version of an earlier piece. Unwittingly, I had selected as my subject a song that was significantly more multilayered than I had thought!

According to a Russian-language article written by V.M. Soldatov (2004), the most widespread version of this tango was attributed to the famous émigré singer Piotr Leshchenko (1898–1954). One of the most popular underground pieces in the 1950s, this song, titled “The Cranes” (“zhuravli”), narrates the profound yearning of an emigrant for his native Russia. I have emphasized the lines that are duplicated in Kirsanov’s version:

The first verse of Kirsanov’s Afghan tango attains an additional measure of clarity when we listen to it within the context of this earlier piece. Kirsanov clearly used the earlier verse as a template for his version, retaining its melody (roughly), fifty percent of the words from the first line, and eighty percent of the words from the second. But the changes he makes to these lines are just as striking. He discards the second half of line one (“I am like an unwanted guest”) reinscribing it with a phrase that situates the tango in Afghanistan (“beneath Kabul’s azure blue”). More ominously, Kirsanov transforms “I hear the cry of the cranes flying off into the distance” to “One can hear the cries of my friends flying off into the distance.”

| Slyshu | krik | zhuravlei, | uletaiushchikh | vdal’ |

| I hear | [the] cry | of the cran | flying off | into the distance |

| Slyshny | kriki | druzei, | uletaiushchikh | vdal’ |

| Are audible | [the] cries | of [my] friends | flying off | into the distance |

If the image in the first version is relatively clear—the cranes are flying off to the emigrant’s homeland, returning to the place from which he is banned—the image in the second is strange. The phrase “friends flying off into the distance” would generally conjure up the image of people on an airplane, but if his friends were on a plane, he wouldn’t be able to hear their cries. Were they side-gunners shouting to him from a helicopter? Perhaps. Or could the cries be the kind of theatrical screams that we have grown accustomed to in B-grade war and action films, as bodies struck by explosions fly through the air? Or are the “friends, flying into the distance” actually those who have already shuffled off this mortal coil, and the “cries” the imagined voices of the dead ascending into heaven, as cranes lift off into the sky? For me, all of these scenarios remain latently present in the recording. But knowing that this line is inherited from an earlier version of the song provides an explanation for the ambiguity embedded within it. At the same time, like the palimpsestic poem that serves as my epigraph, Kirsanov’s adaptation opens up an intertextual relationship with the earlier lyric: by imagining the older song text as hazily visible (or better, audible) beneath the newer one, we can muse upon the structural similarities that soldiers in the Afghan war share with émigrés longing for their homeland. More specifically, we can acknowledge the faint presence of the effaced image of cranes, an image that would likely be on the minds of Kirsanov’s intended listeners, who would be acquainted with the older tango. If I were to describe my own reaction to the palimpsestic penetration of the cranes into the description of Kirsanov’s comrades-in-arms, I would probably point out the inadequacy of language in these circumstances, but then venture that it left me with a vaguely poignant feeling and an inchoate image of human bodies, elongated, gracefully floating away, like the cranes themselves.

There are still more layers to peel back: in particular, two details about the earlier tango are worth mentioning. First, émigré songs such as this were not distributed by the state-owned Soviet music industry in the 1950s. While the tango had been popular in Russia throughout the first half of the twentieth century, more than one generation of Soviet censors saw it as the crystallization of western decadence, a tortured “music for impotents” (Edmunds 2004, 24).[14] Thus, it is not at all surprising that “The Cranes” was not mass-produced on detselit at the government-owned Melodiya studios but rather on X-rays, utilizing the underground “music on bones” format that I discussed above. Once again, we must add another layer of inscription and erasure to our archaeology of Kirsanov’s song.

Second, you will recall that I originally described “The Cranes” as being attributed to the famous émigré singer Piotr Leshchenko. It turns out that the version of the song that was so widely distributed on used X-rays was actually sung not by Leshchenko himself but by another vocalist who worked as a Leshchenko impersonator. In a recent (2004) reminiscence, V.M. Soldatov explains that he “first heard [“The Cranes”] in 1955, on a ‘music on ribs’ disk. . . . The name ‘Leshchenko’ was hand-written on the record.” Only later did he discover that Leshchenko had never recorded “The Cranes.” The version he owned, it turns out, was likely produced by an ensemble called Jazz Tabachnikov, which released forty pieces sung by a man named Nikolai Markov, “whose voice was almost identical to the voice of the famous singer” (Savchenko 1996, 220; quoted in Soldatov 2004). Markov’s name, symbolically overwritten by Leshchenko’s, had been effectively erased from this recording. Erased, but only temporarily: with time, scholars and aficionados succeeded in discerning the identity of the singer despite the layer of false advertising that covered it.

At this point, I almost wish I could say that that was it, that we have reached the bottom, the urtext upon which all the (equally interesting) others were written. But we are not there yet: for I must tell you that there were actually over ten different versions of “The Cranes,” including a well-known one that dates from the 1930s, and a satiric remake set in Stalin’s GULAG (“Pesennik Anarkhista-podpol’shchika”—“Songbook of an underground anarchist,” n.d.). Moreover, all of these different versions were preceded by a poem written by Aleksei Zhemchuzhnikov in 1871, the first quatrain of which reads:

Kirsanov’s “cry of my friends” (kriki druzei) thus rests atop well over a century of “cries of the cranes” (krik zhuravlei). To make matters even more complicated, Zhemchuzhnikov did not originate the “cry of the cranes” trope around which the poem was built. The symbolically loaded cry of the cranes is likely to have been in oral circulation for hundreds of years before it became memorialized in written verse. As a result, rather than ending our archaeological investigation of Kirsanov’s palimpsestic text with a definitive original, we must simply watch, and listen, as the “cry of the cranes” recedes into the mists of the Russian oral poetic tradition. As Clifford Geertz would surely have said, there is no end to the palimpsest of intertextuality: when it comes to language, “it’s turtles all the way down.”[15]

Returning to Kirsanov’s recording, I want to relate a few final palimpsestic moments before moving on. At one point in the tape, Kirsanov performs a song that narrates the experience of a side-gunner on a helicopter. This track begins, predictably, with a recording of a helicopter in flight. Toward the end of this ambient recording, beneath the percussive wash of the rotors, a muffled shout is clearly audible. The exact words are impossible to decipher, but it seems clear that they are in Russian, and so should belong to one of the Soviet troops fighting in Afghanistan in 1980. (My Russian friends agree, but cannot identify the words either...) Listening again, I begin to have my doubts: the echo of the voice sounds too clear and drawn out to have been recorded at the same time as the helicopter. Is this a recording that Kirsanov lifted from a Soviet war film? Possibly. Regardless of its provenance, this voice screaming beneath the white noise of a helicopter in the war zone is arresting.

In the end, though, it is another much more subtle voice that haunts me. Relatively recently, after having reviewed the tape over two dozen times, I was surprised to discover a second voice hidden within the ambient recordings that are woven into Kirsanov’s songs. A song titled “A battle thundered away on the outskirts of Kabul” (“Boi gremel v okrestnostiakh Kabula”) begins with another recording of gunfire, this time with two automatic weapons firing. Buried deep in the mix, in the middle of this gun battle—or is it merely target practice?—one can barely detect the sound of a human voice. The voice appears for a single instant, as a single undecipherable syllable wedged in the silence between two bursts of gunfire:

Audio Example 2: Kirsanov: “A Battle Thundered Away on the Outskirts of Kabul”

Who was the owner of this voice? A fellow Soviet soldier? A member of the Mujahideen? An innocent bystander? We will never know. But this short vocal pip adds yet another layer of complexity to what is already a maddeningly complex musical artifact. Kirsanov presents us with a song about wartime, composed and performed in wartime, which includes the actual mechanized sounds of wartime, along with the faint trace of a human voice amidst the violent noise of war. Like the phenomenological palimpsest in my first example, this recording, composed from multiple sounds emanating from multiple sources, offers us the possibility to listen through the most obvious signals, recovering from the background partially effaced inscriptions that normally go unnoticed. By performing the palimpsestic operation—by bringing the anonymous voice into the foreground—we can open up a consideration of the many humans who were enmeshed in the Afghan war.

To my ears, Kirsanov’s multitracking powerfully evokes the layers of “precarious lives” (Butler 2004) that are both the subject and the context of his compositions, as well as the objects of the kind of fundamental erasure that only organized violence can accomplish. At the same time, his lyrics describe and endorse multiple acts of violent overwriting that have both sonic and corporeal consequences: “akh, how I want . . . to drown out, with a machine gun, my longing for Russia,” for example. Similarly, in another song:

Kirsanov’s protagonists, slicing through the silence of the dawn, certainly don’t want us to hear the voices of the enemy. They prefer to erase them, along with their own sadness, with the deafening cascade of the guns. And yet, on the tape, the literal voice of someone on the battlefield escapes the gun’s roar and presents itself, in Horton-Hears-a-Who fashion: softly, unnoticed by all but the most attentive, but nonetheless powerfully asserting the humanity of its owner. Of course, as I suggested earlier, it is precisely this paradox—the existence of multiple layers inscribed by multiple authors, and the repeated (albeit unsuccessful) attempts to erase that which came before you—that is the defining characteristic of the palimpsest. From this standpoint, we might say that the task of the palimpsestuous listener is to discern both the things that a recording encourages us to remember and the things it urges us to forget, the things that are insistently audible and the things that have long been silenced.

And it is here, on the shifting hermeneutic ground of this weird accretion of inscriptions and erasures, that my imagination takes its leap. Inspired by Kirsanov’s multilayered recording, I imagine a palimpsestic tape that fully captures the Afghan war in all of its troubling acoustic richness, the parts of the war that Kirsanov heard and the parts he was unable to hear.

In a story cowritten with a friend in the same year Stanislav Filon brought his Telefunken home from the German front, Jose Louis Borges described an ancient empire whose obsessive cartographers produced a 1:1 map of the empire itself. Here is the story in its entirety (the opening ellipsis is his conceit):

. . . In that Empire, the craft of Cartography attained such Perfection that the Map of a Single province covered the space of an entire City, and the Map of the Empire itself an entire Province. In the course of Time, these Extensive maps were found somehow wanting, and so the College of Cartographers evolved a Map of the Empire that was of the same Scale as the Empire and that coincided with it point for point. Less attentive to the Study of Cartography, succeeding Generations came to judge a map of such Magnitude cumbersome, and, not without Irreverence, they abandoned it to the Rigours of sun and Rain. In the western Deserts, tattered Fragments of the Map are still to be found, Sheltering an occasional Beast or beggar; in the whole Nation, no other relic is left of the Discipline of Geography.[16] (my emphasis)

What would a Borgesian acoustic palimpsest of Kirsanov’s Afghanistan sound like? In order to attain the absolute, exhaustive, one-to-one fidelity of the map in the story, we could imagine such a recording beginning with the multitrack layering of Kirsanov’s tape, but pushing past the current threshold of audibility, allowing us to hear the sounds of everyone who was ever involved in the Afghan war. Just as the map would show us every pebble, every grave, every blade of grass in the empire, this impossible recording would capture every breath of wind and every whistled melody within the Afghan theater of operations. We would hear all of the sounds of vehicles and weapons, mountains and cities, the sounds of soldiers and civilians, perpetrators and victims, and bystanders. We would hear the sounds of the displaced, of the dying, and of the dead. We would hear the voices of those represented in Kirsanov’s song, and the voices of those whom Kirsanov’s song passively ignores or actively effaces. This ultimate acoustic palimpsest would capture the scriptio superior of representation—that is, the fusion of instrumental music and sung text that we call “song”—but it would also reveal a scriptio inferior consisting of the multiple contexts and complicated networks that precede, surround, and are brought into being by a song’s performance. It would be an infinitely layered recording that would allow us to listen to history itself. It would enable a panacoustic politics of listening, with all the granularity and dynamism that term implies. Borges’s impossible mapping project is precisely the quixotic goal to which I am striving when I incorporate the imagination into my acoustic palimpsest metaphor. This activity creates its own pitfalls, including the structurally important fact that it is destined to failure. In the end, of course, this reading of Borges is a misreading.[17] But as a thought experiment, I find it sharpens my appetite for unearthing unheard and barely heard presences—Avery’s “ghostly matters”—that would otherwise go unnoticed.

Returning from my imagined recording to the actual cassette tape that Kirsanov made in 1981, I conclude with a final moment of palimpsestic irony. At the conclusion of the late-night recording session, Kirsanov’s tape was circulated among his friends in his detachment. With time, dubbed copies were passed along to neighboring military garrisons. According to one account, officers who were nearing the ends of their tours of duty would play Kirsanov’s tape to newly arrived troops in order to prepare them for “the reality of Afghanistan” (Ogryzko 2000, 26). Copies of Kirsanov’s tape found their way to the nearby military hospital, and its patients, once released, were likely to be carrying a copy in their duffle bags as they returned to their posts in Afghanistan or their homes in Soviet cities. Many of these copies were confiscated, however, by customs officers at the Soviet-Afghan border. As Kirsanov tells the story:

There was some unpleasantness with a certain person in the political section of the detachment’s Command [Headquarters] in Kabul. I heard through the grapevine that some of my songs had received unfavorable (nelitsepriiatnyi) reviews, and [had prompted] threats to “settle the score with that crooner” (razobrat’sia s etim pevunom).[18]

Kirsanov suspected that a line in the dirge-like song “Remote Kabul” had generated the unfavorable attention:

His lyrics transparently refer to the young Soviet conscripts who were sent to Afghanistan and, it is clear from the previous verse, died there. Were Kirsanov’s superiors offended by the frank statement that the Communist Party had sent its sons to their inevitable death? Or were they disturbed that the lugubrious tone of the song stood in stark contrast to the marshal grandeur of official songs about the Afghan war? In a reminiscence recently published on an Internet forum devoted to his Afghan song cycle, Kirsanov attempted to convey the tenor of the complaints leveled against him:

“How could he?! An officer in the KGB looks ironically upon our most sacred [Party]! What kind of ideas is he planting in the minds of our politically vulnerable soldiers?!” (This was the general tone of the panegyrics I was receiving.) (“Iurii Kirsanov,” n.d.)

In reaction to the unvarnished critical edge of a few songs within a repertoire that was generally sympathetic to the Soviet cause, the KGB leadership in Moscow stripped Kirsanov of one of his medals, placed him on a list of “untrustworthy” individuals, and, Kirsanov and his friends surmise, ordered the Customs officers to confiscate any Kirsanov tapes that they found in the possession of soldiers crossing the borders. A member of the KGB forces who fought in Afghanistan in the mid-1980s recalls:

I remember returning from my first tours of Afghanistan, when the Customs officers opened and listened to even the cassettes of mine that were in their original wrappers, to see if there were any “Afghan” (i.e., Kirsanov) songs on them. I remember how a nurse in Shindand showed some soldiers who were traveling with her a clever trick for outwitting Customs: she unwound the cassettes and rewound them backwards, so that when they listened to it they would hear something muffled and indistinct. (“Iurii Kirsanov,” n.d.)

Often, when Customs officers did find “Afghan” songs written by Kirsanov or other amateur composers who were deemed suspicious, they erased them by bringing them into contact with a powerful magnet. Like the palimpsestic scribes who scraped off pagan Greek writing for religious reasons, these tapes were wiped clean in order to destroy ideologically suspect texts. Having passed through the censor’s machine, all that remained of Kirsanov’s Afghan soundscapes and lightly subversive songs was the loud metallic buzz of demagnetized tape.[19]

The literal and figurative attempt to erase Kirsanov’s tape from the aural history of the period was initially successful. With no official distributor and only limited bootleg copies reaching the USSR, most Soviet citizens never learned of the tape’s existence. Other more politically acceptable recordings articulated the tenor of the time, at least until the advent of Perestroika and the gradual reduction of the state’s desire and ability to censor. But, like a persistent scriptio inferior, Kirsanov’s cassette eventually emerged as a text ready to be read by those who were willing. After it was scraped away by propagandistic accounts of the Soviet incursion in Afghanistan, and overwritten by the polished tones of official music that elided the war altogether, his amateur recording survived to embody a powerful counterhistory of the war, one that emphasized the toll of the war on all of its participants, its perpetrators and victims, including those the author himself sought to erase.

Palimpsestic listening brings all of these hidden layers to the surface. The palimpsest metaphor urges us to seek out and recover the hidden layers of agency and history and creativity and politics that underwrite and overwrite all sound experiences, and to understand that the acts of making and listening to music always involve both inscription and erasure, inscription and erasure, inscription and erasure, inscription and erasure, inscription and erasure...

Layer 5: surface

(In place of a conclusion, some final thoughts that occurred to the author after writing the body)

By this point, I have stretched the palimpsest metaphor to encompass a truly broad and somewhat bewildering range of phenomena. As I look back on my text, I see that a taxonomy of palimpsest categories would have been helpful to bring order to the conceptual disarray. Without attempting an exhaustive list, and somewhat late in the game, let me suggest that acoustic palimpsests may be:

Textual: when words (or notes) are erased and reinscribed with other words (or notes). Kirsanov’s rewriting of “The Cranes” would be an example of this, as would multiple musical settings of a single poem, or the composerly revisions that are the subject of musicological sketch studies.

Auditory: when sounds from multiple sources occur simultaneously. Masking effects, or the complete drowning out of one sound by another, are possible here. My example of the layers of noise through which soldiers listen for significant sounds during wartime employs the palimpsest metaphor in purely auditory terms.

Intermedial: when a work is translated into a different medium (e.g., poems reinscribed as song texts; novels reinscribed as operas or films), and the new version obscures the existence of the original. Zhemchuzhnikov’s poem disappearing amidst the rhythm of Markov’s tango is an example of this type of intermedial reinscription and erasure. Ravel’s orchestral “Pictures at an Exhibition” obscuring Mussorgsky’s pianistic original is another.

Technological: when a work is inscribed onto a recording medium, and the trace of a former work is still discernable. The ghostly sound of the original track on a rerecorded tape, the X-ray visible beneath the grooves of a “music on bones” record, and the common technique of multitrack recording all qualify.

Authorial/performative: when the original author or performer is obscured by another. Markov’s voice being marketed as Leshchenko’s is an example of this, as would be the Milli Vanilli scandal of the early 1990s or, I suppose, the transformation of Israel Isadore Baline into Irving Berlin.

Symbolic: when an act of erasure and reinscription is described within a work. Kirsanov’s lyric “akh, how I want to drown out, with a machine gun, my longing for Russia” is a symbolic representation of palimpsestic erasure and reinscription.

Ideological: when an act of erasure is the result of a political decision. Censorship of music, and, more broadly, silencing of voices (by killing, imprisonment, or marginalization) can be understood palimpsestically. Musical nationalism can be framed as an attempt to inscribe an ideological orientation on a populace through sound.

Corporeal: when history (in the form of genetics or lived experience) is inscribed into the body. Nina Eidsheim imagines the voice as a corporeal palimpsest.

Memorial: when a sonic event is absorbed into one’s memory, a memory that is itself an accrual of remembered experiences, some of which are ineluctably erased by others. When this happens, the event becomes embedded in the existential palimpsest that is the listener’s consciousness.

If we were to compile all of the layers that we have discerned in Kirsanov's recording, beginning with the oldest and proceeding more or less forward in time, and label them according to these categories, this is the kind of multilayered record we would find:

Layer 1: [textual]:

A poem is written [drawing on folk motifs] by Aleksei Zhemchuzhnikov.

Layer 2: [textual/intermedial/authorial]

The poem is changed [partially erased, partially overwritten] and put to music [inscribed into a new medium]. It begins circulating in live performance. The authorship of the poem and the music is effectively erased.

Layer 3: [textual]

Multiple variations [partial erasures and reinscriptions] of text and melody begin appearing.

Layer 4: [technological/authorial]

A recorded version appears in “music on bones” format, inscribed on used X-rays. This version is sung by Nikolai Markov, whose identity is effectively erased and reinscribed as Piotr Leshchenko. The music on bones version circulates widely.

Layer 5: [textual/authorial]

During the first years of the Afghan war, the text is changed [partially erased, partially reinscribed] several times, by several people, including Kirsanov. Kirsanov emerges as “author” of his variation.

Layer 6: [symbolic]

His lyrics describe an act of erasure and overwriting: drowning out his longing for Russia with the sound of his machine gun.

Layer 7: [auditory/technological]

Kirsanov’s tape involves layering ambient sounds from the Afghan theater of operations underneath his recorded performance.

Layer 8: [auditory]

The ambient recordings all but completely erase the voices of those with and against whom he is fighting. Occasionally, the voices of local Afghans and anonymous others can be discerned beneath Kirsanov’s voice and guitar.

Layer 9: [corporeal]

All of the voices that are layered in this recording are themselves layered artifacts, bespeaking the unique genetics and histories of their owners.

Layer 10: [ideological/technological]

Kirsanov’s recording is partially “erased” by censors, who confiscate and erase copies of his tape at the Soviet border.

Layer 11: [ideological]

His song, and the entire genre of Afghan war songs, are “overwritten” by other musical works describing the Cold War in politically acceptable terms. These works occupy the airwaves, and reduce the possibility that Kirsanov’s songs will influence the public perception of the war.

Layer 12: [memorial]

Everyone who comes in contact with this song (including, most recently, you who are reading this essay) writes it onto his or her memory, if only temporarily. This kind of inscription involves the potential for overwriting other memories; it is also itself constantly vulnerable to erasure.

Layer 6: superstrate

(marginalia, scattered throughout manuscript)

Allow me to pull the curtain aside for a moment: as I look back on this palimpsestic operation, with the various layers of Kirsanov’s song splayed out and pinned back like a frog’s innards on a dissection table, I must admit that I feel a strange sense of incompletion, even dejection. As exhaustive as I’ve tried to be, my acoustic palimpsest of “here, beneath a foreign sky” lacks many of the elements and practices that I, as an ethnographer, have tended to find most important: testimonies from those who found this song valuable; fine-grained analysis of musical moments, notice paid to participatory discrepancies, groove, etc.; broader reflections on cultural resonance—I could go on and on. And here’s something that I find really shocking: I actually corresponded with Kirsanov a few years ago, and I couldn’t really find space within the palimpsest model to write about our conversation. This leaves me with the suspicion that the palimpsest might be best employed as a research methodology, rather than a mode of representation. Might it make sense to imagine the object of investigation as a palimpsest, see how many layers can be discerned within it . . . And then imagine it as something else, and something else again, before the writing process begins?

In any event, as I prepare to step away from this essay, I want to sketch out a few final thoughts about the acoustic palimpsest metaphor. Consider these to be the most important of the marginalia that proliferated on the pages of my latest draft. They consist of several overlapping generalizations about palimpsests, and a rudimentary list of the costs of deploying the metaphor:

- There is something violent about palimpsests. The twin acts of erasure and reinscription that are the palimpsest’s minimal condition can easily be construed as an aggressive move with respect to the past. The desire to erase the past and start afresh is one of the hallmarks of modernism, and the palimpsest metaphor retains some of the violent energy of this movement. While the persistence of the scriptio inferior points toward the impossibility of fully erasing history, the palimpsest is nonetheless infused with the desire to do so. Thus, one of the images that the metaphor is capable of conjuring is that of a text that has been ruined, violated, or even “murdered.”[20]

- There is something intimate about palimpsests. One can choose to ignore the atmosphere of violence I just described, and instead imagine the palimpsest as a congenial relation between two or more texts. Just as the narrator of Anna Akhmatova’s poem experiences a feeling of intimate communication by writing upon her friend’s rough draft, so can we experience a closeness, a sensual proximity even, when we encounter the multiple layers of a palimpsest. The music on bones records represent one kind of felicitous marriage of visual inscription and sonic inscription. Kirsanov’s multitracked recording—with the layers consciously interacting with one another rather than attempting to drown each other out—would be another. Philippe Lejeune's term "palimpsestuous” emphasizes the carnal closeness of palimpsestic layers.

- There is something uncanny about palimpsests. As Sarah Dillon says of Thomas De Quincey’s palimpsests: “the resurrective activity of palimpsest editors always involves uncannily bringing the dead back to life: the footprints of the hunted wolf or stag are traced backwards, back to the start of the hunt, before the game was killed...” (26). The acoustic palimpsest metaphor thus encourages us to think of audible phenomena as complexly layered and to imagine the traces of human activities that have been silenced. Imagining these silences as faint but legible presences rather than absences or nonentities is akin to resurrecting the dead.

- There is something transgressive about palimpsests. The original textual palimpsests involved texts that we weren’t supposed to see, but that pushed through, that crossed back over the threshold of visibility. Acoustic palimpsests often involve sounds that we weren’t supposed to hear: sounds related to the body, to technological mediation, to the neutral background, to the inaudible politics that undergird all sonic situations. These sounds, with all the discomfort that their acknowledgment engenders, are classically queer. The palimpsest metaphor encourages us to listen for the quietest of sounds, and to imagine erased sounds stubbornly pushing back through the threshold of audibility as well.

- The palimpsest metaphor is far from perfect. For all that it brings into focus, the acoustic palimpsest produces a number of distortions and omissions, each of which deserves consideration. Here, briefly, are a few of the more serious limitations that I have noticed:

- It deals with temporality in a problematic way. Textual palimpsests involve layers of writing that were put on one after another, with the most recent one always dominating. The palimpsests that inspired this metaphor thus encourage a unidirectional historical perspective: palimpsestic texts acquire their layers one after another, as time marches forward. You will have noticed by now that the audible and inaudible layers of which I speak have no such temporal unity joining them together. This lack of correspondence weakens the vitality of the metaphor.

- It fails to deal with motion convincingly. Sound is experienced as vibration, as motion, as something subject to attack and decay. The palimpsest metaphor attempts to freeze what is in essence an evanescent experience and presents it as a more or less stable, layered object. At times, such as in the music on bones example, this aura of stability is justified. At others, such as the layered listening example, it is obfuscatory.

- It presumes a privileged vantage point from which all sounds can be heard. To imagine an acoustic palimpsest is to adopt something akin to an omniscient stance. While this stance is relatively common in music scholarship, it obscures the radical situatedness of sounds and of listening. “Listening to the palimpsest” is an imagined activity, and thus is not representative of any individual’s actual listening experience.

- It treats the world as a text. The palimpsest, a metaphor derived from the hyperliterate west, shamelessly treats aurality as a subgenre of textuality, denying it an epistemology of its own. While this position may be in alignment with the critics of phonocentrism, the scriptist bias of the palimpsest metaphor is certainly a problem, and this problem is rendered all the more acute when the object of investigation is not a literary text but sounds.

So there you have it, a number of the pros and cons surrounding this thought experiment, this theory-in-utero. I hope there are more of the former and am certain there are more of the latter that haven’t yet occurred to me. I would like to think that, used a bit more judiciously and less expansively than I have here, the acoustic palimpsest’s greatest utility lies in its ability to encourage a politics of listening that embraces complexity, values history, and draws attention to the hidden dialectics of inscription and erasure that lie beneath all musical moments.

“I would like to think that . . .” Indeed, I would like to think that. But I find in the end that my metaphor’s inherent limitations prevent me from arguing this concluding point more emphatically. As I read back over this text, doubts proliferate: is the acoustic palimpsest really a sound way to write about sound? Is it sound or unsound sound writing? Having reached the end of this essay, I find myself wishing I could start over again, in the hopes that the next time I might get it right. (Tell the truth, colleagues: how many of you have never felt this perverse desire?) But wait: perhaps my palimpsest metaphor can rescue me from the very predicament in which it has placed me:

“ . . . The original text was washed away with a mixture of milk and oat bran or scraped clean by medieval scribes using pumice dust . . .”

Having inscribed this layered text, this meditation on erasure, can I erase what I’ve written so far? Can I wipe out my treatment of Kirsanov, and Filon, and soldiers in Iraq, and iPod users, only to try again to capture their essence tomorrow? Like a medieval scribe with a scraping knife, can I unwrite this text? In doing so, can I compel you, dear reader, to unread it?

Of course I cannot.

[Delete all.]

[Restart.]

Layer 7: superstrate

(epigraph, written in pencil on the back of the last page, with several words erased and rewritten in a different hand)

Works Cited

- Akhmatova, Anna. 2006 [1943]. “Poem without a Hero [excerpt].” In The Poetry of Anna Akhmatova: Living in Different Mirrors, by Alexandra Harrington, translated by Alexandra Harrington, 226–7. London: Anthem Press.

- Avtomat i Gitara. Accessed July 12, 2009. [formerly http://avtomat2000.narod.ru/Verstakov.html].

- Balas, Costas, Vassilis Papadakis, Nicolas Papadakis, Antonis Papadakis, Eleftheria Vazgiouraki, and George Themelis. 2003. “A Novel Hyper-spectral Imaging Apparatus for the Non-destructive Analysis of Objects of Artistic and Historic Value.” Journal of Cultural Heritage 4, Supplement 1: 330–37. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/S1296-2074(02)01216-5

- Bates, Eliot. 2004. “Glitches, Bugs, and Hisses: The Degeneration of Musical Recordings and the Contemporary Musical Work.” In Bad Music: The Music We Love to Hate, edited by Christopher J. Washburne and Maiken Derno, 275–293. New York: Routledge. http://dx.doi.org/10.4324/9780203309049

- Beer, David. 2007. “Tune Out: Music, Soundscapes and the Urban Mise-en-scène.” Information, Communication & Society 10, no. 6: 846–66. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13691180701751031

- Belyi, Igor’. 2008. “Plastinki na rëbrakh” (Records on ribs). Accessed July 12, 2009. http://bujhm.livejournal.com/381660.html.

- Borges, Jorge Luis. 1975. A Universal History of Infamy. London: Penguin.

- Bull, Michael. 2007. Sound Moves: iPod Culture and Urban Experience. London: Routledge.

- Butler, Judith. 2004. Precarious Life: The Powers of Mourning and Violence. London: Verso.

- Connor, Steven. (2005) 2011. “Ears Have Walls: On Hearing Art.” In Sound: Documents of Contemporary Art, edited by Caleb Kelly, 29–39. London: Whitechapel Gallery/MIT Press. Originally published in FO(A)RM no. 4 (2005): 48–57.

- Daughtry, J. Martin. 2009. “‘Sonic Samizdat’: Situating Unofficial Recording in the Post-Stalinist Soviet Union.” Poetics Today 30, no. 1: 27-65.http://dx.doi.org/10.1215/03335372-2008-002

- _______. 2012. “Belliphonic Sounds and Indoctrinated Ears: The Dynamics of Military Listening in Wartime Iraq.” In Pop When the World Falls Apart: Music in the Shadow of Doubt, edited by Eric Weisbard, 111–44. Durham: Duke University Press.

- ———. Forthcoming. “Aural Armor: Charting the Militarization of the iPod in Operation Iraqi Freedom.” In The Oxford Handbook of Mobile Music Studies, edited by Jason Stanyek and Sumanth Gopinath. New York: Oxford.

- De Quincey, Thomas. (1845) 1998. Suspiria de Profundis. In Thomas De Quincey: Confessions of an English Opium Eater and Other Writings edited by Grevel Lindop, 87–181. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

- Derrida, Jacques, and Jeffrey Mehlman. 1972. “Freud and the Scene of Writing.” Yale French Studies 48: 74–117. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/2929625

- Derrida, Jacques. 1976. Of Grammatology. Translated by Gayatri Chakravorty Spivak. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

- Dillon, Sarah. 2005. “Reinscribing De Quincey’s Palimpsest: The Significance of the Palimpsest in Contemporary Literary and Cultural Studies.” Textual Practice 19, no 3: 243–63. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09502360500196227

- ———. 2007. The Palimpsest: Literature, Criticism, Theory. London: Continuum.

- Edmunds, Neil. 2004. Soviet Music and Society under Lenin and Stalin: The Baton and the Sickle. New York: Routledge.

- Eidsheim, Nina. 2008. “Voice as a Technology of Selfhood: Towards an Analysis of Racialized Timbre and Vocal Performance.” Ph.D. diss., University of California, San Diego.

- Elsaesser, Thomas. 2009. “Freud as Media Theorist: Mystic Writing-Pads and the Matter of Memory. Screen 50: 100–113. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/screen/hjn078

- Freud, Sigmund. (1925) 1991. “A Note upon the Mystic Writing-Pad.” In On Metapsychology: The Theories of Psychoanalysis, Penguin Freud Library, vol. 11, edited and translated by James Strachey, 427–34. London: Penguin.

- Geertz, Clifford. 1973. The Interpretation of Cultures. New York: Basic Books.

- Genette, Gérard. 1997. Palimpsests: Literature in the Second Degree, translated by Channa Newman and Claude Doubinsky. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press.

- Gordon, Avery. 2008. Ghostly Matters: Haunting and the Sociological Imagination. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press.

- Grieg, Donald. 2003. “Ars Subtilior Repertory as Performance Palimpsest.” Early Music 31, no. 2: 196-209. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/earlyj/xxxi.2.196

- Huyssen, Andreas. 2003. Present Pasts: Urban Palimpsests and the Politics of Memory. Stanford: Stanford University Press.

- “Iurii Kirsanov.” n.d. Accessed June 4, 2009. http://salambacha.com/index.php?newsid=110.

- Ivanov, Boris. 2008. “Mesto v istorii” (A place in history). Novoe Literaturnoe Obozrenie 6: 295–305.

- Kirsanov, Iurii. n.d. [untitled description of underground album.] Accessed August 20, 2009. http://tomi.net.ru/forum/viewtopic.php?t=322885.

- Lacasse, Serge. 2003. “Intertextuality as a Tool for the Analysis of Popular Muisc: Gérard Genette and the Recorded Palimpsest.” In Practising Popular Music: 12th Biennial IASPM-International Conference Proceedings, edited by Alex Gyde and Geoff Stahl, 494-503. Berlin: IASPM.

- Latour, Bruno. 2007. Reassembling the Social: An Introduction to Actor-Network-Theory. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Leppert, Richard. 1995. The Sight of Sound: Music, Representation, and the History of the Body. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Mathisen, Ralph W. 2008. “Palaeography and Codicology.” In The Oxford Handbook of Early Christian Studies, edited by Susan Ashbrook Harvey and David G. Hunter, 140–68. Oxford: Oxford University Press. http://dx.doi.org/10.1093/oxfordhb/9780199271566.003.0008

- McDonagh, Josephine. 1987. “Writings on the Mind: Thomas De Quincey and the Importance of the Palimpsest in Nineteenth-Century Thought.” Prose Studies 10: 207–24. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/01440358708586308

- Nelson, Amy. 2004. Music for the Revolution: Musicians and Power in Early Soviet Russia. University Park, PA: Pennsylvania State Press.

- Nethersole, Reingard. 2005. “Reading in the In-Between: Pre-Scripting the ‘Postscript’ to Elizabeth Costello.” Journal of Literary Studies 21, nos. 3–4: 254–76. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/02564710508530379

- Ogryzko, Viacheslav. 2000. Pesni Afganskogo Pokhoda. Moscow: Kontsern “Literaturnaia Rossiia.”

- Ortner, Sherry. 1997. Making Gender: The Politics and Erotics of Culture. Boston: Beacon Press.

- “Pesennik anarkhista-podpol’shchika.” N.d. [formerly http://www.a-pesni.golosa.info/dvor/zuravlinadkolymoj.htm].

- Peters, John Durham. 2008. “Resemblance Made Absolutely Exact: Borges and Royce on Maps and Media.” Variaciones Borges 25: 1–24.

- Porcello, Thomas. 1998. “‘Tails Out’: Social Phenomenology and the Ethnographic Representation of Technology in Music-Making.” Ethnomusicology 42, no. 3: 485–510. http://dx.doi.org/10.2307/852851

- Rapantzikos, Konstantinos. 2005. “Hyperspectral Imaging: Potential in Non-destructive Analysis of Palimpsests.” Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Image Processing (ICIP), Genova, Italy. Accessed January 4, 2010. http://ieeexplore.ieee.org/stamp/stamp.jsp?tp=&arnumber=1530131.

- Savchenko, Boris. 1996. Estrada retro (The retro stage). Moscow: Iskusstvo.

- Soldatov, V.M. 2004. “Zhuravli v ispolnenii Nikolaia Markova i ‘Dzhaza Tabachnikov’” (The cranes in the performance of Nikolai Markov and ‘Dzhaz Tabachnikov’”). http://www.blatata.com/2007/09/01/zhuravli-v-ispolnenii-nikolaja-markova.html.

- Taigin, Boris. 1999. “Rastsvet i krakh ‘Zolotoi sobaki’” (“The Rise and fall of the ‘Golden dog’”). Pchela no. 20 (May–June). http://www.pchela.ru/podshiv/20/goldendog.htm.

- Verstakov, Viktor. 1991. Afganskii dnevnik (Afghan diary). Moscow: Voennoe Izdatel’stvo.

- ———. 1992. “S chego nachinalas’ afganskaia pesnia?” (“From what did Afghan songs emerge?”). Gazeta Moskovskogo okruga PVO “Na boevom postu” no. 77 (May 7).

- Zhemchuzhnikov, Aleksei. (1871) 1987. “Osennie zhuravli” (“Autumn cranes”). In Russkaia poeziia XIX – nachala XX v. (Russian poetry of the 19th and early 20th centuries), edited by N. Nikushkina. Moscow: Khudozhestvennaia Literatura.

Notes

This article had an unusually long gestation, and has benefited from many readers over the years. I am grateful to Deborah Kapchan for encouraging me to write it and patiently reading through several revisions. I would also like to thank the Walters Art Museum; Patricia Hall, the readers, and Edmond Johnson at Music and Politics; Emily Daughtry; and the organizers and participants in a series of “Theorizing Sound Writing” events at NYU and the Society for Ethnomusicology in 2008 and 2009. Particular thanks go to Piotr Trubetskoi and Igor’ Belyi for their work as archivists and scholars of music on bones. My most emphatic thanks go to Iurii Kirsanov, and to the Iraq and Afghan war veterans whose perspectives inform this article. Any light shed on the layeredness of listening is our corporate achievement. All of the article’s deficiencies, however, are my own.

According to Gérard Genette (1997), the term “palimpsestuous” was coined by Phillippe Lejeune.

See for example the palimpsest article in the 2010 Encyclopaedia Britannica Online, http://www.britannica.com/EBchecked/topic/439840/palimpsest. Strangely, I have found this exact quote in several publications, including peer-reviewed journals, without quotation marks or proper attribution (e.g., Rapantzikos 2005; Nethersole 2005; Balas et al. 2003). Without endorsing this behavior, I will only note that the irony created by scholars of palimpsests plagiarizing a text about palimpsests is of a decidedly postmodern (not to mention palimpsestic) flavor.

In a section of De Quincey’s autobiography (Suspiria de Profundis, 1845) titled “The Palimpsest,” the author metaphorically links the reinscribed parchment with human cognition, memory, and history—and this eighty years before Freud’s “mystic writing pad” (see the next footnote)! As Josephine McDonagh (1987) writes of De Quincey’s text,

[His] initial account of the palimpsest as a literal agent of history tells how it contains texts from different historical periods in a single parchment: in De Quincey’s example these are a Greek tragedy, an early Christian “monkish legend,” and a twelfth century romance. The palimpsest is the “library” or “archive” through which “the secrets of ages remote from each other have been exorcised.” It then becomes a model for the human mind in general: “What else than a natural and mighty palimpsest is the human brain?” De Quincey asks, linking historical and psychological models (208).