The Black Muse: Polish Hip-Hop as the Voice of “New Others” in the Post-Socialist Transition

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Polish hip-hop, with its origins and evolution, confirms the link between hip-hop and social exclusion. Its history coincides with the transition from socialism to democracy and the free-market economy. The changes in hip-hop forms, functions, formal and informal distribution, and in its reception, reflect a rapidly changing socio-economic situation, and illustrate the importance of the specific social context for this genre. Without it, the elements of hip-hop (DJing, MCing, breakdancing and graffiti) functioned as separate entities, not as constituent parts of a whole. Mainstreaming amplified the voice of the “new others” of post-socialism, but at the price of its distortion and of hip-hopolo as its ineluctable destiny.

In Poland, fans of hip-hop call their genre czarna muza (“black muse”), applying this name to African American as well as to Polish hip-hop. Muza (“muse”) functions in this context both as a word for “an inspiration” and as an abbreviated form of muzyka (“music”). Asking about one’s musical preferences, people say “Jakiej słuchasz muzy?” (“What muse do you listen to?”). The term “black muse” can be interpreted as recognition of the genre’s African American origin and of its Polish appropriation; on the other hand it indicates that Polish hip-hop is conceived of as a fully-fledged musical genre with its own ethnic and linguistic specificity.

In his study of rap and hip-hop outside the USA, Tony Michell draws attention to the fact that although hip-hop has become a global phenomenon with distinctive local manifestations that combine models and idioms derived from U.S. hip-hop with indigenous elements, U.S. academic commentaries continue to emphasize the socially marginal and politically oppositional aspects of U.S. hip-hop, regarding it as a coherent, cohesive and unproblematic expression of an emancipatory African American culture of resistance.[1] Polish hip-hop is a phenomenon that cannot be considered simply as an extension of African American culture. While it would not have come into being without the prior emergence of African American hip-hop, its history demonstrates that the existence of hip-hop in the USA was not on its own enough to transplant the genre into Poland.

The beginnings of Polish hip-hop in the late 1980s coincide with the country’s transition from socialism to democracy and a free-market economy. This paper is an attempt to demonstrate that Polish hip-hop cannot be fully understood outside this context. Looking at hip-hop in Poland in a society perceived largely as homogeneous, in which race (at least as it is understood in America) is not central to societal discourses, the article will provide an opportunity to illuminate some aspects of the genre that might be overshadowed in studies of U.S. hip-hop.

Polish hip-hop creates an opportunity to include a grass-roots perspective within the conceptual scheme of post-socialism, an angle that is rarely explored. Most studies of regime transition in Poland and other countries from the former Soviet bloc are regularly focused on themes of institutional politics or economic transformations and adopt an elite-centered point of view. The intensity of socio-economic changes in Central and Eastern Europe in turn highlights processes that would otherwise be much harder to identify. The changes in hip-hop’s forms, functions, formal and informal distribution, and reception, reflect a rapidly changing socio-economic situation and illustrate the importance of a specific social context for this musical genre.

“Solidarity” victorious: the historical context

In the 1980s, as hip-hop in the USA experienced its most creative period, the Solidarity movement in Poland was eroding the dominance of the Communist Party. An extremely strong wave of strikes in June and August 1980 resulted in the emergence of an independent trade union organization headed by Lech Wałęsa, which quickly became a widespread social movement involving over nine million people (a quarter of the entire population of Poland) and including workers, intellectual dissidents, people associated with the Roman Catholic Church, and even members of the ruling Communist Party. Although Solidarity called for the rationalization of the existing system and not for a political revolution and adhered to a policy of nonviolent resistance, it became a major political force in opposition to the regime.[2]

The communist government led by General Wojciech Jaruzelski sought a solution for the growing economic crisis and intensified social tensions through martial law (imposed on December 13, 1981) and the de-legalization of Solidarity. Martial law, however, did not resolve Poland’s problems and amidst the deepening crisis the so-called Round Table Talks (February 6—April 4, 1989) between party leaders and representatives of the then unofficial opposition led to partially free parliamentary elections in June 1989, in which Solidarity triumphed and, as the first non-communist government in Central and Eastern Europe, initiated the difficult process of reform.[3]

The founding of Solidarity can be seen as the culmination of a long process of struggle for authority and legitimacy.[4] Under State socialism, with the political monopoly of the communist party and State control over the means of production, social cleavages developed around different moral visions and value systems. As Grzegorz Ekiert and Jan Kubik have argued, “the fundamental distinction was drawn between those who controlled political and economic resources and attempted to legitimize their authority, and those who had little power but struggled to make ‘their’ discourse visible, audible, and, eventually, hegemonic.”[5] Thus, on the road to post-communism, cultural revolution preceded political revolution.[6]

Hip-hop was a misfit in the culture politics of the socialist state in Poland in the 1980s and also could not fulfill the specific needs of the oppositional counter-culture. The heroic Solidarity ethos of a noble struggle found its musical expression primarily through protest songs, growing out of the tradition of the bards, which criticized the regime and appealed to traditions of patriotic resistance against the oppression of the Polish people. Jacek Kaczmarski became a symbol of Polish guitar poetry, and his song Mury (“Walls”) functioned as an unofficial Solidarity anthem. Przemysław Gintrowski and Paweł Orkisz were also among the respected bards of that time. Their lyrics frequently employed metaphors such as walls (that will fall down one day), captured white eagles,[7] sieges, wounds, stones that can initiate an avalanche, a coming dawn, etc. They referred to different forms of oppression and to the hope that the oppressed would rise one day. These songs were not commercial (written to be sung and not to be sold) and circulated outside official distribution channels (usually on homemade cassettes). They were closely related to a specifically Polish genre called poezja śpiewana (“sung poetry”).[8] Although most of these songs did not lose their meaning with the collapse of socialism, they did lose their significance.

The transfer of power was followed by comprehensive reforms in the economy, political institutions, and local administrations. State-controlled industry began to be privatized, prices were freed, subsidies were reduced, and Poland's currency (the złoty) was made convertible as the country began the difficult transition towards democracy and a free-market economy. The price for such radical reforms (referred to as the “shock therapy” or “Balcerowicz plan”) was very high and has been the subject of many controversies.[9] Industrial output and real wages declined dramatically, the poverty rate increased, and a gap opened between the rich and the poor, but the most painful and undesired by-product of the reforms was rapidly and constantly growing unemployment, the highest among all the countries of Central and Eastern Europe.[10]

Although the cost of reform was immense, the early 1990s was a time of optimism and great expectations from the new system. In popular imagery, Western democracy and capitalism were simply identified with an affluent lifestyle. People believed that the drop in living standards was only temporary, especially if they could see some positive results of the “shock therapy.” Inflation was reduced, firms came up against hard budget constraints for the first time, the black market was eliminated, and the universal shortage of consumer goods abated.[11] In a society tired of social unrest and the deep economic crisis of the previous decade, these signs of stabilization and prospects of economic growth were perceived as promises of a bright future.

Hip-hop did not fit into this optimistic context either. Although restrictions limiting travel and exchange of information were lifted and Polish youth could have become acquainted with hip-hop, the genre did not gain popularity in Poland.[12] At the beginning of the period of transformation hip-hop seemed destined to share the fate of other musical genres that were not well suited to Polish culture. Hip-hop’s journey to its present form and position within mass culture was long and convoluted.

Disco polo, a uniquely Polish genre, was the first to come to prominence and experience commercialization when the political struggle was over and state monopoly of recording industry came to an end.[13] Played and sung in the country and at provincial fun fairs, discos, wedding parties or other events, disco polo gave people enjoyment, fun, and temporary relief from their everyday troubles. It had developed spontaneously in the 1980s and circulated outside official channels of distribution, having been denied access to the mainstream media or the state-controlled recording industry. When the Socialist system dissolved, newly-emerging private labels turned to music that was widely popular among the people, but hardly accessible for sale. Disco polo, previously restricted to homemade recordings and available almost exclusively through private exchange, became the basis of a cassette industry and flourished throughout the country.[14] Newly-recorded cassettes were sold in hundreds of thousands of copies despite the genre’s exclusion from the airwaves, from record stores and from formal concert venues for three years (1989–92).

The power of the disco polo industry was finally recognized by media decision-making bodies and catchy songs about love began to have exposure on the private television station Polsat, which broadcast Disco Relax. Although public radio and television tried to keep the genre from the airwaves, it dominated the popular music domain in Poland for the next few years (until 1997). No other aspect of mass culture underwent more severe criticism, especially from the intelligentsia, and the suffix “–polo” entered the Polish language, signifying bad music, poor taste, and business-inspired esthetic compromise.

Are the elements of hip-hop enough to have a “hip-hop culture”?

At the earliest stage of its development the elements of hip-hop—MCing, DJing, breakdancing and graffiti—functioned in isolation in Poland, albeit reinvented from different angles. While breakdancing and MCing were imported phenomena, graffiti and DJing evolved from local practices.

I. Graffiti, DJing – Local Practices

There is a long tradition in Poland of using graffiti as a symbol of protest and resistance. The famous “Solidarność” (the Polish word for “solidarity”) logo, which laid the foundations of the international visual legacy of the 1980s in Poland, is a particularly potent example. (See Figure 1.)

Unmistakably a graffiti tag, this symbol of the movement that initiated civil awakening all over Central and Eastern Europe appeared on walls in all Polish cities during the 1980s. Painted secretly and usually anonymously, it was diligently covered over by administrators of public buildings, and eagerly suppressed by communist authorities, especially during the harsh time of martial law (from December 13, 1981 to July 22, 1983). The letters, written in a red color and subversive-looking font with a white and red flag above the letter “N,” appeared during the last week of the legendary time of August 1980, and spread from the Gdansk Shipyard throughout the country as a symbol of the civil disobedience that was paralyzing the communist regime. According to an urban legend, it was first painted in red paint on the shipyard wall at night and was later copied onto paper. In fact, the logo was created by Jerzy Janiszewski, a renowned graphic designer and creator of many acclaimed posters, who supported the workers on strike from the very beginning and wanted to provide them with something that would give them a group identity.[15] He intended it to resemble people leaning on each other as if giving each other support. The “Solidarity” tag became a model of a specific lettering style called solidaryca, which was perceived as spontaneous, vivid, and somewhat indocile. Being so different from the grayish atmosphere of the Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa (PRL)[16] it gained immediate popular appeal, and became a standard type of lettering for bold political graffiti during the 1980s.

Another example is the symbol of “Fighting Poland”:

The letters P (for “Poland”) and W (for “Walcząca,” which translates as “fighting”) are combined to make a stylized anchor. This symbol of hope was drawn on walls as a manifestation of resistance. Such a use of graffiti was socially acceptable and even supported as an act of disobedience towards an establishment collectively disapproved of by the people. Because of the shortage of goods, the graffiti of the 1980s were painted exclusively with simple tools such as brushes, rollers, and stencils.

All this changed in post-communist Poland. Spray paints became easily available (although expensive), but the socially-sanctioned rationale for graffiti disappeared with freedom of speech and the emergence of an independent media. Painting on walls came to be regarded as an act of vandalism. From the mid-1990s, graffiti became more colorful and came to be practiced by young people from urban areas not only on walls but also—as in other countries—on trains. It took almost a decade for graffiti to receive public recognition as a visual art.[17]

DJs were part of the disco landscape for decades. They were also an element of so-called prywatka, i.e., unofficial parties hosted in private houses, an essential part of youth life in urban areas. The DJ’s role at a party would be to respond to the mood of audiences, choosing mixes, often pre-created, that would keep the audience interested. Early DJs were often friends of party hosts who just happened to have the needed equipment or recordings. The practice of pre-creating mixes resulted from a very practical necessity: a cassette player was the most widely used audio equipment, often being the only one available.

Pre-created mixes and DJing were connected with various musical genres. For example, such mixes marked the most popular program on music in Poland in the 1980s, Lista Przebojów Programu Trzeciego (“The Hit List of Channel 3 of Polish Radio”). Its author, Marek Niedźwiecki, promoted mostly rock music, both Polish and Western, and the public could vote for any song aired on this channel.

The status of DJs as artists is still a matter of controversy in Poland. For many people DJs are artisans rather than artists as their work is considered to be of a technical rather than musical nature. Moreover, due to their limited access to professional audio equipment (multiple turn-tables have only been in use for the last few years), Polish DJs could not for a long time display many of the skills that built the reputations of American DJs. Those against the idea of DJs as artists emphasize that DJs only play music created by others; according to this opinion, even the most successful and sophisticated blending of tracks by others remains essentially re-creative. Those in favor claim that DJs make a new sound quality from their blends, so their work must be creative. Those who provide beats for hip-hop pieces call themselves simply producers.[18]

II. Breakdancing, MCing – Imported Phenomena

What we know as breakdancing reached Poland for the first time in the mid-1980s. Its appearance is usually attributed to Stan Lathan’s movie Beat Street, which circulated widely in Europe after its success at the Cannes Film Festival in 1984. Be-Bop, founded in 1986, is considered to be the first breakdancing group in Poland. Among other early hip-hop groups there were Broken Steps (from Szczecin) and Scrap Beat (from Włocławek). Breakdancing, however, did not become popular until the 1990s, when it functioned, in post-communist Poland, as an acrobatic dance for teenagers.

It is significant that the name “breakdancing” took on a different connotation in Poland. Still today, the “break” in breakdancing is associated not with the idea of “the cut,” or interlude, but is specifically linked to the act of breaking one’s joints when dancing. Such misinterpretation resulted not only from an unawareness of the origins of breakdancing, but also from its initial functioning outside hip-hop culture.

One example of breakdancing from outside hip-hop culture comes from the video Jesteś Szalona (“You are [a] crazy [girl]”) by the group Boys. This classic of disco polo features five young men dancing on a beach in matching shirts, pants, and shoes. The video presents the whole crew in coordinated moves in a standing position with a soloist doing power moves. A dancing episode also comes back later in the clip.

Video Example 1: Jesteś Szalona (“You are [a] crazy [girl]”)

Performed by the group Boys; lyrics and music by Janusz Konopla from the group Mirage (1992); a cover by Maricn Miller with the group Boys from the album O.K. (1997) became one of the greatest disco polo hits. Used by permission of the group.

Some other disco polo groups (for example Toples[19]) also employ elements of breakdancing at their concerts. Skateboarding became a physical activity associated, alongside breakdancing, with hip-hop culture in Poland.

MCing presents a different case. Called “rapping,” it too is an imported phenomenon, involving rhythmically-delivered rhyming. This very distinguishing feature of hip-hop music was neither confined to hip-hop in Poland, nor was it linked directly to hip-hop themes. Improvised rhythmic melo-recitation became popular among young people in the 1990s, but it was done simply for fun, and was usually not engaged with any profound topics.

A particularly striking example of Polish rap comes from the group T-Raperzy znad Wisły (“TV Rappers from the Vistula River”). Its members were well-known in Poland as cabaret entertainers providing satirical commentary on Polish life. Their most famous rap album, Poczet królów polskich (“The Gallery of Polish Kings”) from 1995, contains thematic songs which summarize and comment on the reigns of particular Kings of Poland. While their accounts of past events are historically accurate, their highly colloquial language stands in contrast to the seriousness of the topic and the accuracy of the historical data, contributing to the overall comic effect of the show.

The following video example features the song Mieszko, named for the first historical ruler of Poland (reign c. 963? – 992), who converted to Christianity in 966 and was the father of Bolesław Chrobry, the first crowned king. As in all other songs from the series, the two artists (Grzegorz Wasowski and Sławomir Szczęśniak), dressed in historical costume and sitting in front of a background featuring a current map of Poland, remove historical layers of their clothes as the song progresses. The four-measure refrain of Mieszko is “Mieszko, Mieszko, nasz koleżko” (“Mieszko, Mieszko, our buddy”).

Video Example 2: Mieszko

From the album Poczet królów polskich (“The Gallery of Polish Kings”) by the group T-Raperzy znad Wisły (1995), a parody of rap. The entire series was broadcast by Polish public television as a part of a cabaret show KOC: Komiczny Odcinek Cykliczny. All reasonable efforts have been made to secure permission.

The group’s next rap album, Lektury literatury (“Literature Set Books”) from 1997, was devoted to the most important books of Polish literature,[20] providing skillful summaries of their plots combined with insightful interpretations. All these songs were featured on KOC: Komiczny Odcinek Cykliczny (“A Comic Cyclic Episode”), a very popular cabaret show on public television in the 1990s.

“New others”: new contexts that brought the elements of hip-hop together

As the preceding discussion has shown, the elements defining American hip-hop existed in Poland in the 1980s and at the beginning of the 1990s, but as separate entities, and there was no genre corresponding to African American hip-hop. Such a genre came into being in Poland in the late 1990s. The reason for this, I believe, was the significant change in the socio-economic context. Tricia Rose, in her widely acclaimed study Black Noise, calls hip-hop a voice from the margins.[21] Indeed, what became the catalyst that brought the elements of hip-hop together and created the conditions enabling the emergence of Polish hip-hop was a “new margin” that appeared as a result of the transition to capitalism.

Since the 1990s the exclusion of people from the mainstream of society dominated the discourse of disadvantage, which had previously centered on the issues of poverty and inequality. However, there is no uniform way of approaching social exclusion in contemporary social studies, and the differences in emphasis that appear, depending on the context in which exclusion is discussed, are rather significant.[22] While cultural alienation can be related to race, sex/gender, religion or ethnicity in other countries, in Poland, as sociologist Alicja Sadownik points out, it affects people who are socially marginalized.[23] Ethnicity and religion are not factors of primary importance for determining social cleavages in post-socialist Poland which, with its post-Second World War ethnic-religious composition, is perceived as a homogeneous country. In consequence of the shift westwards of Poland’s borders after the Second World War, accompanied as it was by massive population movement involving both voluntary and forced migrations between 1946 and 1949, Poland became over 98 percent Polish and over 95 percent Roman Catholic.[24] Although this ethnic-religious composition is gradually evolving and current assessments of the size of various minority groups vary,[25] Poland can hardly be considered multicultural, especially in comparison to other countries of the EU or to its pre-war composition.[26] Significantly, despite the Church’s efforts, religion was not an important factor during political elections. For example, the parties marketing themselves as Catholic (or Christian) failed to receive significant support from the voters, and among post-communist prime ministers there have been Catholics as well as atheists and a Protestant.

The nature of social exclusion in contemporary Poland is well captured in Janusz Czapiński’s study Social Diagnosis. Czapiński defines social exclusion as a multidimensional phenomenon of non-participation in various aspects of social life that can result from poverty, cultural conditions, or health problems. He identifies three types of social exclusion caused by different factors: structural exclusion (depending primarily on location/address, father’s education and income), physical exclusion (correlated with age and disability) and normative exclusion (linked with lifestyle choices and associated with drug and alcohol abuse, criminal histories, loneliness, or being a victim of discrimination).[27] Czapiński’s analyses indicate that, in contrast to normative exclusion, structural exclusion tends to be permanent, and is directly linked to poverty resulting from unemployment.

Under late socialism, social exclusion was in general related to normative rather than structural factors.[28] Disproportions of wealth were insignificant and by the 1980s Polish society was polarized primarily into “us” (society) and “them” (the state).[29] The social stratification into the peasantry, the working class, and the intelligentsia allowed for transfers between these classes, and belonging to the social margin was more a matter of a personal lifestyle choice than a predetermined situation of an individual. This situation altered after 1989 and the new division between the winners and losers of the regime change became visible as a cleavage between the rich/powerful and the poor/powerless.

In Poland, hip-hop is linked to a particular type of settlement called blokowisko (agglomerations of blocks of flats). Such agglomerations of apartment buildings are not exclusive to large industrial cities but are to be found all through the urban-rural continuum. They were often connected to a specific industrial enterprise, housing the workers and their families. In villages, smaller apartment buildings accompanied state farms. A collapse of all state farms and most of the state-owned industrial enterprises (which often supplied the vast majority of jobs in the area) at the beginning of the transformation resulted in the dramatic degradation of the socio-economic status of the inhabitants of blokowisko and a lack of prospects for their children. Soon blokowisko came to symbolize the habitat of the new system’s losers.

The first communities in Poland attracted to hip-hop as a culture were those young people from blokowisko who were among the first to suffer economic and social deprivation as a result of the move to capitalism and who became, together with former state farm employees and many workers and peasants, the “new others” of the transition. They were labeled blokersi (a name that refers to the blocks of flats in which they live) or dresiarze (a name that refers to the tracksuits they typically wear). These communities abandoned disco polo, of which they were previously big fans, in favor of a musical genre that was seen as a very radical one. They were responsible for igniting the first hip-hop genre, uliczny hip-hop, which translates literally as “street hip-hop.” It was modeled around perceived traits in gangsta rap, such as drugs, crime, and hopelessness. Its earliest reception was not positive. The first years of Poland’s transformation to capitalism were a time of enthusiasm and hope. “Street hip-hop” did not fit this social context, unlike the light-hearted, cheerful, and optimistic disco polo.

Moreover, the difference between the new margin (that resulted from structural exclusion unknown in the previous system) and the old margin (that resulted from normative exclusion and was typical for the previous system) was not yet widely recognized in Polish society. Blokersi, caught in a structural framework which they could not influence, were viewed not as people with problems but as the problem itself. From the perspective of liberal economists and the new elite (coming from the intelligentsia) that dominated the mainstream ideology and grand narratives in the new system, division into winners and losers ultimately translated into those who were wise and able to adapt and those who were half-witted and unable to adapt; [30] in other words, blokersi were deemed to be victims of their own fate. In this binary opposition, it is the first group that defines what people should adapt to and how they should do it, and if individuals and groups cannot adapt they have by definition proven themselves to be “civilizationally incompetent.”[31] Their ineptitude was attributed to old mental habits that were characterized in the famous figure of homo sovieticus, whose attitude was shaped by egalitarianism and a demand for state support, by “disinterested envy,” anti-intellectualism and an aversion towards the elite, by double standards for public and private life and an acceptance of inadequate performance.[32] As Buchowski noticed,[33] this view ignored the paradox that it was the Communists who, as members of the nomenklatura,[34] should have been most profoundly imbued with the old system’s habitus but proved to be one of the quickest in switching to a new symbolic system, in mastering “civilizational competence.”

In Polish post-socialist popular culture, young hooligans and criminals were typically portrayed as having gym-fit bodies, very short hair, sports shoes and tracksuits—also attributes of dresiarze. This association resulted in an initially negative perception of the communities associated with hip-hop. The links to gangsta rap, with its controversial poetics and topics, reproduced and amplified the derogatory stereotypes about the phenomenon and its public. Hip-hop’s narratives on drugs and crime associated the genre with these issues, which grew after 1989 but which had not been considered to be a major problem until that time.[35] As a result, early Polish hip-hop existed primarily as an underground phenomenon, centering around three cities: Kielce, Katowice, and Warsaw.

All this changed in the late 1990s. Disillusionment with capitalism, a significant slowing of the economy, and a growing unemployment rate that reached almost 20 percent at the beginning of the new century, created a new social context. With it hip-hop finally gained a popular appeal, particularly among recent college graduates (born in the 1980s and thus hardly coming under the definition of homo sovieticus), who found themselves suddenly representing a “generation of unemployed masters.” Hip-hop became the voice of a generation of which even the most gifted and energetic were not able to make their mark due to the prolonged economic recession. Artists such as Hemp Gru, Molesta, Pezet, Warszafski Deszcz (with Tede), WWO, ZIP Skład, DJ 600 V (all from Warsaw), Slums Attack with its leader Peja, Nagły Atak Spawacza, Gural (all from Poznań), became nationally recognized. Great national success was achieved by the album Księga Tajemnicza. Prolog (“A Mysterious Book. Prologue”) by the Silesian group Kaliber 44 (Magik, Joka and Abradab) that exemplified hardcore-psycho rap (a psychedelic type of Polish rap), but the genre did not attract prominent followers.

A new stream in Polish hip-hop emerged that was labeled by journalists inteligentny hip-hop (“intelligent hip-hop”), and stood in clear opposition to uliczny hip-hop (“street hip-hop”). Whereas the latter was modeled on gangsta rap and often borrowed directly from American hits,[36] inteligentny hip-hop turned towards local production and lyrics rooted in Polish culture and local reality. Linguistically very creative, it drew inspiration from three sources: grypsera (language developed by criminals), American hip-hop (however, Americanisms were often deformed), and the old-Polish language (words that had dropped out of common usage long ago).[37] This new wave created new-found respect for hip-hop, igniting the careers of Paktofonika, Eldo (with his group Grammatik), Fisz (also his brother Emade, sons of renowned Polish musician Wojciech Waglewski), and Łona, or O.S.T.R. Since 1998, local hip-hop productions have prevailed over foreign hits, and most fans listen to Polish hip-hop exclusively.[38]

In the late 1990s, hip-hop also became visible in the media. Hip-hop magazines (Klan and Hip-hop Magazine) were published, professional websites were launched, a radio station—Radiostacja—began a large-scale promotion of hip-hop culture, and VIVA Polska! began broadcasting and sponsoring hip-hop videos. By 2000, hip-hop had earned a place in mainstream music in Poland. The album Kinematorgrafia (“Cinematography”) by the group Paktofonika, was the first to reach the hit lists, though the group’s career was cut short by the death of its leader, Magik, a legendary Polish MC widely considered to be unsurpassed.

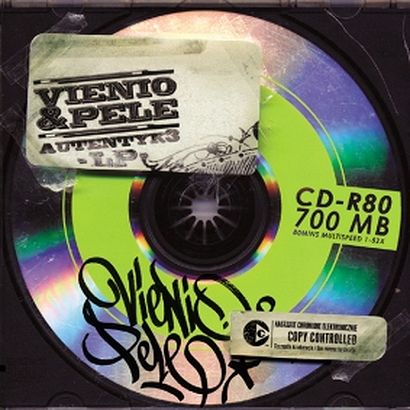

In addition to those groups for whom wide recognition was followed by financial success, there is also a large underground hip-hop movement—groups involved in the genre for their own satisfaction, looking (or not) for a record label and known usually only to local fans. Although most of the people engaged in the underground scene hope for a future mainstream career, some deliberately choose the underground networks as the only platform for their creative activities, regarding popularity and financial success as a betrayal of hip-hop ideals. Some underground artists, such as Tetris (recognized especially for his freestyle[39] skills), Jimson, Reno, Smarki, Zkiboj, CeHa, or Klimat, have built up considerable reputations among hip-hop fans. These artists release homemade albums that are called nielegal in hip-hop slang (nielegal [“illegal” in English], a noun derived from the adjective nielegalny, literally translates as “an illegal,” but in this context means an album that is perfectly legal but issued without a label and circulated “unofficially” via copies burned on PCs and passed from hand to hand or made available for downloading from the internet).[40] The cover of the album Autentyk 3 by Vienio&Pele, designed by Forin (a graphic designer and recognized graffiti artist), is stylized as such an underground issue.

In contrast, albums issued by record companies are called legal (literally translated as “a legal”). The terms legal and nielegal are also used with reference to graffiti. The former means an official burner painted in a space specifically reserved for it, while the latter refers to a graffito painted without permission.

Hip-hop as a patriotic genre

References to established Polish culture, present in both mainstream and underground hip-hop, call for a reconsideration of the widely accepted view that samples in hip-hop are chosen solely for their sonic qualities. A compelling example is provided by the song Portret (“Portrait”) from nielegal Pandemonium by Klimat. Its very powerful story is a tribute to a girl from a good family who becomes pregnant in high school and decides not to have an abortion. Abandoned by her boyfriend, and not supported at home, she literally landed on the street. However, she did not give up and withstood all hardships. She finally found a man who loved and respected her, but she died in a car accident soon after they were married.

The piece starts with a quotation from Chopin’s Funeral March (from the Sonata No. 2 Op. 35) that becomes the basis for the beat of the entire piece. Chopin’s work, recognized immediately by Polish people regardless of their age and social status, effectively signals a tragic and heroic theme and determines the solemn character of the song. As a refrain the song uses a sample from Could It Be Magic by Take That.

Audio Example 1: Portret (“Portrait”)

From the album Pandemonium (2004) by the group Klimat; Polish hip-hop, an example of nielegal. Used by permission of the group.

Whereas the music of Chopin, Poland’s national composer, is affiliated in Poland with symbols of Polishness, heroism and struggle and Polish hip-hop amplifies this association, classical music in general gained a new signification in the post-socialist world. In the piece List Otwarty (“An Open Letter”) by the group Nagły Atak Spawacza (“Welder’s Sudden Attack”) Carl Orff’s Carmina Burana is used as background to an interview with a representative of the intelligentsia who compares Polish hip-hop to the products of people who are mentally ill or under the influence of drugs. The interviewee protests against referring to hip-hop as if it were an artistic production and advocates ignoring it in the media. Here, classical music, representing high culture (but not specifically Polish culture), signifies the new elite and contributes to building the binary opposition between the world of the elite—personified by the eloquent intellectual speaking polished language—and the world and language of the “new others,” symbolized by harsh hip-hop beats and full of swear words, rapping about the hard reality in which they have to live.

Audio Example 2: List Otwarty (“An Open Letter”) (excerpt)

By the group Nagły Atak Spawacza (“Welder’s Sudden Attack”) from the album Psychedryna (1997); Polish hip-hop. Used by permission of the group.

It is significant that hip-hop artists in Poland identify themselves not only with their local space but also with their country, negotiating a wide national space within the global genre. The Gallery of Polish Kings was not a unique phenomenon, but rather a sign that the genre can benefit from utilizing the potential offered by Polish history and culture. The video clip Patriota (“A Patriot”) by Zipera (2004) well characterizes this tendency in Polish hip-hop from the years 2002-2005. Juxtaposing pictures from Polish history that became symbols of the heroic struggle for national independence[41] with pictures of contemporary Poland, it asks the question: what does it mean nowadays to be a Polish patriot? It presents Polish hip-hop as a unifying force that tells the cleansing truth, calling us to look into the future (which is now in our hands) while simultaneously remembering the painful past:

Video Example 3: Patriota (“A Patriot”) (2004). By Zipera.

This explicit declaration of love for country had a very positive reception in Poland. Even in productions less openly patriotic than Patriota or Kochana Polsko (“Beloved Poland”) by O.S.T.R., artists manifest their sense of belonging to the nation by rapping in Polish, by frequent allusions to Polish history or culture, by wearing clothing in the white and red colors of the national flag, and by the self-identification claimed in narratives such as “I, a Pole” as opposed to “them,” who are usually “government pigs,” or elites. “I represent myself, the family, a local space, respect, pride, faith, and good intentions” declares a rapper in the longest Polish hip-hop video, Reprezentuję siebie (“I represent myself”) featuring the group Bez cenzury (“Uncensored”) with the most prominent Warsaw rappers as its guests.

No other genre of contemporary popular music in Poland demonstrates such a strong patriotic tendency, often combined with severe criticism of the political and economic establishment, because of which “Poles are poor and the Polish family oppressed,” in the words of the WuHae group’s song Po co ja się męczę (“For what do I take pains”). Frustration with the real world is usually accompanied by exhortations to take responsibility for one’s life despite the situation. Hip-hop also reflects the importance of family values in Poland, which are typically put before personal fulfillment and professional success.

At first sight such strong national self-identification in Polish hip-hop may seem surprising. The collapse of the Soviet-imposed communist regime was interpreted as a trigger for full sovereignty, manifested in the change of official state symbols. National/patriotic issues seemed to be no longer relevant and disappeared from the mainstream media and public discourse at the beginning of the 1990s. Moreover, as Poland, after the collapse of the Soviet Block, aspired to play an active role within the sphere of Western civilization and become a member of the European Union,[42] the nationalist topic was de-emphasized in official discourses. Against the strong cosmopolitan tendency, hip-hop emphasized domestic values and brought Polishness back to public attention.

However, when we look at Polish hip-hop as an anti-elitist genre, its nationalist inclination becomes fully understandable. Bart Reszuta sees Polish hip-hop as a new cultural form that “emerged to challenge whatever bad came to be associated with liberalism, and to awaken morally wrong enthusiasts and beneficiaries of the transformation.”[43] Standing in opposition to the pro-European and pro-market intelligentsia, hip-hop gave voice to various fears and anxieties that accompanied regime transition and Poland’s entry into the EU. It adapted values and symbols that were deeply rooted in Polish tradition but were questioned by the new, liberal elites as burdens rather than assets in the ongoing transformations.

Neither the functioning of nationalism as a form of counter-culture nor the linking of social and moral justice with the national agenda was unique to hip-hop in Poland. The nationalistic/patriotic attitude has been perceived as a manifestation of protest and resistance from the time of the partitions of the country in the last decade of the eighteenth century until the Solidarity movement of the 1990s. The idea of nationalism as a solution to problems generated by capitalism can already be observed in the 1920s and the 1930s (when sovereign Poland first encountered capitalism). According to Joanna Kurczewska’s studies on national concepts in Polish sociology, national principles and national solidarity were, at that time, often seen as factors that could reduce the moral and social consequences of industrialization in general and the costs of the free-market economy in particular. Identification with a national community functioned to restrict individualism, injustice in the distribution of goods, the feeling of hierarchical dependency as well as regional, class, and more particular local interests.[44] When, as the result of parliamentary elections in 2005 (a year after the admission of Poland to the European community), power was transferred to right-wing populist and anti-European parties, political hip-hop suddenly lost its credibility as a counter-culture and “was caught chanting pro-government songs.”[45]

Hip-hopolo – the Beginning of the End?

The transition from underground to mainstream in Polish hip-hop—as in American hip-hop itself—involved commercialization, with young teenagers (13–15 year olds) now a targeted audience. Hip-hop became fashionable. Paradoxically, however, the hip-hop presence in mainstream media coincided with a fall in hip-hop record sales. This resulted in part from the increasing popularity of MP3s, and in part from the fact that attention soon shifted from music to clothing and accessories. Style was emphasized. In fact, in Warsaw in 2005 there were twenty-seven stores that specialized in hip-hop clothing, yet their clients were not hard-core hip-hop fans but kids buying what was currently in fashion.

Mainstream music based on street hip-hop is thought of as a second-hand style which, like disco polo, is said to attract youth hoping for an instant career who did not have anything original to say. Recently, especially since 2004, Polish hip-hop has been criticized for repeating itself, for duplicating the same old rhymes, the same complaints, and the same negative images modeled on MTV hits. The derogatory term hip-hopolo is being used for this corrupted genre, in which the suffix “-polo” again indicates something commercialized and in bad taste.

Although there is no agreement as to what actually constitutes hip-hopolo, hip-hop fans often describe it as “mainstream (s)hit”[46] or “pseudo hip-hop.” The term hip-hopolo is commonly associated with the label UMC Records and its artists—18L, Ascetoholix, 52 Dębiec, Owal, or Mezo—who grew out of street hip-hop, and whose albums became immediately successful with the support of TV VIVA, radio ESKA, or the magazine hip-hop.pl. Pieces such as Aniele (“Angel”) and Żeby Nie Było (by Mezo), Suczki (“Little Bitches”) and Na spidzie (by Ascetoholix), To my! (“It’s us!”) (by 52 Dębiec), or Jak zapomnieć (“How to forget”) (by 18L) stirred the hip-hop community and provoked a devastating critique of artists who, in search of commercial success, turn away from social problems to party-oriented productions that lean towards mainstream commercial popular music.

Respected hip-hop artists try to distinguish themselves from this trend and reproach it in their pieces for its highly derivative character and emphasis on the overblown stereotypes of MTV hits. Such pieces as Inny niż wy (“Different from you”) by Eldo (Grammatik), Odzyskamy hip-hop (“We’ll get hip-hop back”) by O.S.T.R. and multiple songs by Peja (for example Nie-kocham hip-hop [“No – I love hip-hop”] or Seks dragi rap [“Sex, drugs, rap”]) mock pseudo-street hip-hop, accusing it of being self-serving, and claim their authority over the genre. The attitude towards women in hip-hopolo, especially calling them “little bitches” (as adopted secondhand from American hip-hop), is among the most criticized issues. However, the challenging and complex gender aspect of Polish hip-hop goes beyond the scope of this paper and deserves a detailed, separate study.

According to the vast majority of hip-hop communities in Poland, hip-hop can be competently judged only from within, and they blame the ignorance of media decision-making bodies for hip-hopolo and the falsified picture of Polish hip-hop among the general public.[47] Music journalists in the mainstream media mostly did not hear of hip-hop until it became a part of popular culture, and even then their understanding of the phenomenon was only superficial. Such mainstream attention resulted in self-perpetuating media over-exposure of artists associated with hip-hopolo, generating a distorted picture of the genre among both music critics and audiences, who were unaware of the existence of a different hip-hop, regarded by its fans as true, non-commercial, good and worthwhile.

Those accused of serving up low quality hip-hopolo as “real” hip-hop consider such a critique to be a childish approach to competition in the music business and reply that if authorities in music, such as programming music directors (who never played disco polo), consider their music to be “real” hip-hop, then it is hip-hop.[48] Mezo says, in his song Rapuj (“Rap”):

There seems to be an intrinsic contradiction in the notion of a commercially successful hip-hop of street origin. On the one hand the value and authenticity of the genre relies on the first-hand experience of harsh reality; on the other, the financial prosperity that follows commercial success takes artists out of the world they are supposed to represent. In Polish hip-hop this contradiction can already be observed in the career of Liroy (actually Piotr Marzec), in retrospect often considered the first Polish rapper,[49] and the founder of Polish gangsta rap. After achieving financial success, Liroy left Kielce and moved to the seaside (to Gdynia), becoming a capitalist through his business investments and part of the bourgeoisie he criticized in his productions. Soon he also became a target of attacks from the hip-hop community (both artists and fans).

Liroy’s case shows that the metaphorical “blackness” claimed by Polish hip-hop does not mean that Polish artists copy African American artists by singing about the black ghetto in the USA. Moreover, the approval of African American artists, although highly desired and actively sought after by Polish hip-hop artists, is neither sufficient nor necessary for a good reputation among the Polish hip-hop community. The power of Liroy’s first bestselling album Alboom is attributed to its ghetto sound, but it appealed as something exotic, both fascinating and unreal, and, as such, was denied authenticity.[50] Liroy was not acclaimed as a prophet of the genre even though he was called “the real O.G. [“Original Gangsta”] by Ice-T.[51] The most famous product of the anti-Liroy campaign, Antyliroy by Nagły Atak Spawacza, contains seventy to eighty swear words and samples taken directly from Bodycount, House of Pain, and Snoop Doggy Dog to demonstrate that “Liroy’s gangsta is easy to fake and definitely not the answer to local needs.”[52] Equaling African Americans in production quality and singing sincerely about local reality as it affected a significant part of young generation became the standards by which Polish hip-hop was to be measured. The album Skandal by Molesta (1997) was considered an indicator that the best Polish hip-hop groups met these standards and generated increased interest in local productions.[53]

The questionable authenticity of hip-hopolo resulted in hip-hop’s retreat from the pop music domain and its return to a primarily underground existence. A gradual decline in hip-hop’s presence in the mainstream media has been observable since 2005. MTV and VIVA Polska have ceased broadcasting programs hosted by rappers, some hip-hop magazines and web pages disappeared, and artists—even very prominent ones—are turning back to the nielegals that are available on the internet for free downloading or through paid services.

Another change of social context further contributed to hip hop’s decline. After Poland’s admission to the European Union in May 2004, the country’s economy became stronger, instigating a more optimistic outlook. Rapid economic growth combined with the large wave of work-based emigration to the so-called “old” EU member states resulted in a significant decline in unemployment. With these altered conditions, a comeback of ludic music including disco polo can be observed.

Conclusion

As Michał Buchowski has observed,[54] the powerless and the poor need to resort to radical methods if they want to articulate their interests. When they do, however, they are described as uncouth and ignorant of the new socio-economic reality. Polish hip-hop, the new radical musical genre, was one means by which the “new others” of the post-socialist transformation could find their voice. At the same time its radicalness provoked attacks on “street hip-hop.” Its audiences, trapped in a structural framework which they could not influence, were regarded not as people with a problem but as the problem itself. Mainstreaming of the genre offered amplification of their voice, but at the price of its distortion, the dilution of its message, with hip-hopolo as its ineluctable destiny.

The case of Polish hip-hop, with its origins and evolution, confirms the link between hip-hop and social exclusion. Hip-hop indeed seems to be the voice of a margin, but of a specific margin that resulted from structural exclusion, which is imposed by society rather than deriving from individual choice. Without this social context, elements of hip-hop (MCing, DJing, breakdancing and graffiti) functioned in Poland as separate entities, not as constituent parts of a whole. It was the specific context that enabled the emergence of Polish hip-hop as a genre and determined its uniqueness. The transition to the mainstream resulted in a corruption of the genre, while still further change in the social context, resulting from shifting political-economic circumstances, led to its decline.

The sobriquet “black muse” does not mean singing about the black ghetto in America. American hip-hop was a condition necessary to but not sufficient for the emergence of Polish hip-hop. Import and imitation alone cannot account for the widespread popularity of a genre as long as it is irrelevant in the local context. Only when its seeds found favorable conditions in the local environment could this musical genre grow, not merely as an exotic plant but in all its local variety.

Notes

Tony Mitchell, ed., Global Noise: Rap and Hip-Hop Outside the USA (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 2001), 3.

In Poland, communist rule has always been resisted because it was Russian (thus foreign) and not just because it was Marxist. See Stephen White, Communism and its Collapse (London: Routledge, 2001), 53.

For further information regarding “the most paradoxical of European revolutions that began in the Lenin Shipyard (in Gdansk),” see Timothy Garton Ash, The Polish Revolution, 3rd ed. (New Haven: Yale University Press, 2002).

Grzegorz Ekiert and Jan Kubik, Rebellious Civil Society: Popular Protest and Democratic Consolidation in Poland, 1989–1993 (Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 1999), 4–5.

See Jan Kubik, The Power of Symbols Against the Symbols of Power: The Rise of Solidarity and the Fall of State Socialism in Poland (University Park: Penn State University Press, 1994).

A white eagle is a symbol of Poland. A White Eagle (“Orzeł Biały” written always in capital letters) on a red shield is Poland’s Coat of Arms.

The genre poezja śpiewana refers to songs consisting of a poem and music written especially for that text, with emphasis always on the text. Such songs are often referred to as “gentle music,” and are typically accompanied by guitar or piano, although other acoustic instruments (for example flute or violin) can also be used. The performers (a soloist or a group) are either singer-songwriters or write their own music to texts by renowned poets. The primary audiences for this genre were students. This is also a commerce-free genre, though occasionally some artists (for example, Ewa Demarczyk, Marek Grechuta, Wolna Grupa Bukowina, and Grzegorz Turnau) have achieved wider popularity.

See Leszek Balcerowicz, Socialism, Capitalism, Transformation (Budapest: CEU Press, 1995); George Blazyca and Ryszard Rapacki, eds. Poland into the 1990s: Economy and Society in Transition (New York: St. Martin’s Press, 1991); Grzegorz Kołodko, “Transition from Socialism and Stabilization Policies: The Polish Experience,” in Trials of Transition: Economic Reform in the Former Communist Block, ed. Michael Karen and Gur Ofer (Boulder: Westview, 1992), 129–50; Kazimierz Poznanski, ed., Stabilization and Privatization in Poland: An Economic Evaluation of the Shock Therapy Program (Boston: Kluwer Academic Press, 1993); Jeffrey Sachs, Poland's Jump to the Market Economy (Cambridge: The MIT Press, 1993); Ben Slay, The Polish Economy: Crisis, Reform, and Transformation (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1994).

The unemployment rates during the first years of transformation in Poland were 6.1 percent in 1990, 11.8 percent in 1991, 13.6 percent in 1992, and 15.7 percent in 1993. Quoted after Ekiert and Kubik, 66.

In the early 1990s hip-hop could only be heard on “Yo! Raps,” a program broadcast by MTV at midnight on Saturdays through satellite TV, which was not yet widely available in Poland.

Video 1 featuring Jesteś Szalona (“You are [a] crazy [girl]”) by the group Boys exemplifies this genre.

The original name of the genre, muzyka chodnikowa (“sidewalk music”), that referred to cassettes sales from temporary stands on the sidewalks, was changed to the “nobler-sounding” disco polo as a reference to Italo-disco. The name change was the inspiration of Sławomir Skręta, the owner of Blue Star, the first label established to record such music.

Wladyslaw Serwatowski, “Exhibition ‘Images of “Solidarity.” Solid Art’.” Instytut Adama Mickiewicza Polish culture over the world, available from http://www.culture.pl/en/culture/artykuly/wy_in_wy_solid_art_bruksela_barcelona

PRL—Polska Rzeczpospolita Ludowa (“The People’s Republic of Poland” or “Polish People’s Republic”)—was the official name of Poland from 1952 to 1989.

It is also worth recognizing the close link that exists between graffiti and comics, another graphic medium with a long tradition in Poland and a controversial status in the realm of visual arts. Elaborate graffiti pieces are often inspired by styles developed in comics; on the other hand, mini “throw-ups” and other signs modeled on graffiti lettering can be found in personal notebooks containing graphic expressions by young people. A “throw-up” in hip-hop graffiti is a large two- or three-color tag, painted quickly, usually in bubble or block letters, typically outlined in one color and filled in with another (a “fill-in” is another name for a “throw-up”).

See, for example, an interview with O.S.T.R., one of the most respected artists of Polish hip-hop, Radek Nałęcz. “O.S.T.R. – Rozmowa.” Mobilizacja. Magazyn Rapowy, available from http://mobilizacja.pl/index.php?akcja=teksty&podstrona=4&id_nr=5

Marcin Siegieńczuk, the leader of the group, recently started a new project with the same dancers; called Tsoonami, it is inspired by European techno.

Tracklist: 01. Potop, 02. Pan Tadeusz, 03. Chłopi, 04. Balladyna, 05. Lalka, 06. Nad Niemnem, 07. Zemsta, 08. Krzyżacy, 09. Popioły.

Tricia Rose, Black Noise: Rap Music and Black Culture in Contemporary America (Middletown: Wesleyan University Press, 1994).

See David C. Thorns, The Transformation of Cities: Urban Theory and Urban Life (New York: Palgrave Macmillan, 2002), 151. Ruth Levitas identifies three discourses of exclusion recently prominent in Europe: the “re-distributional discourse” (which focuses upon poverty and inequality, and the distribution and re-distribution of wealth), the “moral underclass discourse” (which focuses upon the moral and behavioral delinquency of the excluded), and “the social integrationist discourse” (which focuses on integration rather than exclusion and is particularly popular in the EU). Emphasis is placed on the last two with a tendency towards replacing the questions “who is excluded and why” with the question “how they become excluded.” Ruth Levitas, Inclusive Society?: Social Exclusion and New Labour (Basingstoke: Macmillan, 1998).

Anna Zawadzka, “Elita nie spotka Downa. Rozmowa z Alicją Sadownik o wykluczonych i elicie,” [“The Elite will not meet a Down (an informal word for a child with Down syndrome). An Interview with Alicja Sadownik about the excluded and the elite”] in Gazeta Wyborcza: Duży Format (11 April 2008).

David Lane and George Kolankiewicz, Social Groups in Polish Society (New York: Columbia University Press, 1973), 7.

According to statistics published in The Warsaw Voice, 15 September 1991, there were c. 350,000 Germans in Poland at that time, together with 350,000 Ukrainians, 200,000–250,000 Byelorussians, 30,000 Slovaks and Czechs, 25,000 Lithuanians, 25,000 Gypsies, and 15,000 Jews, totaling about 1 million or about 2.5 percent of Poland’s population. According to the minority associations, there were 250,000 Byelorussians, 250–300,000 Ukrainians, 700,000 Germans, 25,000–30,000 Slovaks, 15,000–20,000 Lithuanians, and about 10,000 Gypsies. See Krystyna Kłosińska, "Mniejszosci narodowe w Polsce," in Barometr Kultury, ed. Miroslawa Grabowska (Warszawa: Instytut Kultury, 1992), 54; cited in Ekiert and Kubik, 236.

Poland’s borders had been subject to considerable changes in previous centuries, resulting in a mixed population. Of the pre-war population of 32 million in 1931, only 22 million were Poles; the balance comprised 3.2 million Ukrainians, 2.7 million Jews, 1.2 million Ruthenians, nearly a million Byelorussians, some three-quarters of a million Germans and 138,000 Russians. See Lane and Kolankiewicz, 3–4.

Janusz Czapiński and Tomasz Panek, Diagnoza Społeczna 2003: Warunki i Jakość Życia Polaków [Social Diagnosis 2003. Conditions and Quality of Life of the Polish People] (Warszawa: Wyższa Szkoła Bankowości, Finansów i Zarządzania, 2004).

Although ethnicity and religion played important roles in the early stages of the regime (to mention only Operation “Wisła” against the Ukrainian, Boyko and Lemko populations, the “anti-Zionist campaign,” and the campaign against the Church), they lost their importance when the system became well established.

Michał Buchowski, Rethinking Transformation: An Anthropological Perspective on Post-Socialism (Poznan: Humaniora, 2001), 15–16.

See Piotr Sztompka, The Sociology of Social Change (Oxford: Blackwell, 1993).

See Piotr Sztompka, Trauma wielkiej zmiany. Społeczne koszty transformacji [Big Change Trauma. Social Costs of the Transformation] (Warszawa: ISP PAN, 2000), 55.

The Russian term nomenklatura (номенклату́ра), deriving from the Latin nomenclatura meaning a list of names, was originally the list of powerful positions or jobs whose occupants needed to be approved by the Party; later it was also applied to the people who occupied these positions.

See Emil W. Pływaczewski, “The Russian and Polish Mafia in Central Europe,” in Global Organized Crime: Trends and Developments, ed. Dina Siegel, Henk van de Bunt, and Damian Zaitch (Dordrecht: Kluwer Academic Publishers, 2003), 63–72.

For specific examples of such borrowings from and covers of well-known American hits, see Bart Reszuta, “Global Identities—Local Choices; A Case Study of Hip-hop, Poland,” paper presented at the Internationalen Kongressens der Deutschen Gesellschaft für Semiotik (DGS) (Frankfurt an der Oder, 2006), 8, available from [formerly http://www.sw2.euv-frankfurt-o.de/downloads/dgs11/pdf/Reszuta.pdf]. The paper is in English.

Examples of Polish hip-hop slang can be found in Reszuta, 10.

According to Klan magazine’s survey from 2000, 89 percent of its readers listened to Polish hip-hop only. See Andrzej Buda, Historia kultury hip hop w Polsce 1977-2002 [The History of Hip-Hop Culture in Poland 1977-2002] (Głogów, Andrzej Buda Wydawnictwo Niezależne, 2001), 3; cited in Reszuta, 9.

“Freestyle” in hip-hop is usually defined as lyrical improvisation (over any random beats or a cappella) and is an important element in building an MC’s reputation. Freestyle rap is essential to MCs’ battles, in which the contestants “diss” their opponents through clever lyrics.

Underground Polish hip-hop can be found at the following websites: Polskie Podziemie! www.polskie-podziemie.com/; Metropolia. Niezależna Scena Hip-Hop [formerly http://www.metropolia.net]; Hip-Hop.pl http://www.hip-hop.pl/podziemie/

The vast majority of the material was shot in The Warsaw Rising Museum. For further information about the uprising see The Warsaw Rising Museum, http://www.1944.pl/.

Bart Reszuta, “The Eclipse of Christian Socialist Utopia in Polish Rap,” a paper presented at the Conference Jugend und Musik: Politik, Geschichte(n) und Utopie(n), Essen, July 2007, 3.

Joanna Kurczewska, “Naród w Socjologii Polskiej” [Nation in Polish Sociology] in Dusza społeczeństwa. Naród w polskiej myśli socjologicznej [The Soul of a Society. Nation in Polish Sociological Reflection] (Warszawa: Narodowe Centrum Kultury, 2002), 22-23.

This spelling was found on Internet discussion forums. The pun can be found also in spoken language. In Polish pronunciation “hit” sounds more like the English “heat.” When it is accented and pronounced like the English “hit,” it suggests “shit.”

Tomasz Gezela, “Hip-hopolo,” Doza kultury, 6 May 2005, available from http://doza.o2.pl/?s=4108&t=3060.

See, for example, interviews with Remik (the head of the UMC label) or Doniu (Ascetoholix) by the editors of Hip-hop.pl www.hip-hop.pl.

Actually the first hip-hop production that gained wider popularity was the album “Wzgorze Ya-Pa 3” (1995) by the group Wzgorze Ya-Pa 3 from Kielce, but Liroy was the first nationally recognized hip-hop artist. Unlike other early rappers, such as Kaliber 44, Wzgorze Ya-Pa 3, Trials X, 1kHz or SA Prize, who debuted with a small independent label SP Records, Liroy published his albums with BMG Ariola Poland.

During the Marlborough Rock Festival in Sopot 1995; Reszuta, “Global Identities,” 8.

Reszuta, “Eclipse,” 4. Liroy was renowned for using thirty-three swear words in one song and for direct borrowings from American productions.