Gender, Politics, and the Fighting Soldier’s Song in America during World War I

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This article discusses how singing played an integral role in the training of US soldiers during World War I. President Wilson established the Commission on Training Camp Activities (CTCA) to build an army in 1917, and among its most valued activities was singing. As a military tool, some organizers even explicitly linked singing to the ability to fight and shoot well. The political rhetoric of the American war effort and the government’s plans to train soldiers intersected closely with a boom in war song publication. Societal ideas of masculinity find redefinition during this period, and Julia Kristeva’s idea of the political subject frames a discussion of rhetorical and musical impact on the masculinity of the soldier. In the context of the military and gender discourse of the time, “Over There,” “Good-bye Broadway, Hello France,” “Joan of Arc,” and “My Belgian Rose” find detailed analysis.

The social role of music in violent conflicts is multifaceted. Both a vehicle for propaganda and an agent of comfort, music in wartime produces a complex web of pleasure, power, and identity. Here, I explore how the military propaganda about song’s integral role in training practices formed the American soldier and how the publication of war songs in America in 1917 shaped public opinion. The comparatively high number of popular songs published in America during the few years of its involvement (surpassing the number of songs published in any other nation involved) suggests that singing played an important role in the American perception and experience of the conflict. Music’s social function during wartime presents an intersection between two significant social experiences: musicality and conflict. As a meeting of two seemingly disparate practices that nonetheless work powerfully to promote political goals, I explore the significant national and gendered signifiers that drove the success of these songs in America during the First World War.

The politics of the American war effort and the government’s plans to train soldiers intersected closely with a boom in war song publication. The training practices of the military also incorporated strong rhetoric about singing, and this rhetoric, combined with propaganda posters approved by the Committee on Public Information, contextualizes the four popular songs that I address here, from the highly popular “Over There” to the relatively less known, “My Belgian Rose.” And in order to investigate singing as a socially and politically meaningful practice, I employ Julia Kristeva’s idea of the “speaking subject” to understand singing’s ability to shape the political subject’s social, gendered, and military experience.[1] The singing of war songs influenced the public’s conceptual negotiation of the violence of the war, or as one writer describes it, the “concentrated bloodletting” on European soil.[2] I emphasize the devastation of the war, not for effect, but to underline the disjunction between the war’s modern violence and the pleasures of singing in a sheet music tradition that had developed in the 19th century. Singing war songs helped allay soldiers’ fears and comforted families by painting a positive image of the war experience; but as could be expected, the songs also redefined and obscured some realities.

First, a brief discussion of a recording from 1916 of a British soldier singing situates my study of song, musical style, and the subject. Sergeant Edward Dwyer received the Victoria Cross in 1915 for bravery on the battlefields of France. Here, in a 1916 speech, he talks about his experiences in the war and gives a demonstration of singing on the front. And while this paper specifically examines American soldiers and songs, Dwyer’s style—his melodic invention, repetition of words, and vocal breaks—should remain fully present throughout, as a reminder of how soldiers sang on the march and in the trenches.

. . . There was only one thing that could cheer us up on the march and that was singing. We used to sing Tipperar . . . Tippy choruses, invented by some of the chaps. Tipperary was in full swing then and they’d always go on to something they’d invented themselves. It used to buck us up and we would march all the better for it. Sometimes we’d sing some of T.H. Elliot’s songs. You know, the stuff they taught at school, but we’d always go into something we’d invented. I don’t think I’ve got much of a voice for singing, but I’ll try and sing one or two of the choruses we used to sing [singing to “Auld Lang Syne”]. We’re here because, we’re here because, we’re here because, we’re here! . . . [changing tune] We’d be far better off, far better off, far better off in a hu . . . [last word unclear; changing tune] Here we are, here we are, here we are again. How long! How long?! Helow, How— lo, how long, oh oo! Here we are, here we are, here we are again. How long, How long, Hel-lo, Hel-lo, Hel-lo Hel-lo, He-lo! Whoo!![3]

To hear a recording of this excerpt spoken and sung by Sgt. Edward Dwyer, listen below:

Dwyer’s words evince a strikingly repetitive and monothematic tone, but his vocal production breaks and strains with significance. “Tipperary,” of course, was the popular British tune “It’s a long, long way to Tipperary,” but as he indicates, the soldiers “always” moved to a song that they had invented. To snippets of “Auld Lang Syne,” Dwyer’s repeated “we’re here because, we’re here . . .” captures a sense of inescapability, and the repeated, degenerating “how long” that breaks into a cry, calls out for normality. This recording raises the question: What do the details of his emotive performance reveal about the intersection of singing, military life, and this first modern war? To begin, I discuss the role of song and music in the military.

After President Wilson’s declaration of war in April 1917, the government established the War Department, under which the Commission on Training Camp Activities (CTCA) operated. Their charge was to coordinate the building of the American army (which until then had been a relatively small organization) into a force of a million men. Among its other programs, the CTCA officially incorporated “mass singing” into its training. The organizers integrated singing’s perceived benefits into their progressive agenda to form moral and upstanding, fighting men. In a special presidential preface to the Commission’s book entitled Keeping our Fighters Fit from 1918, Wilson wrote, “No army ever before assembled has had more conscientious and painstaking thought given to the protection and stimulation of its mental, moral and physical manhood.”[4] These three linked components of masculinity found direct attention in the training manuals, and the CTCA believed that singing promoted all three.

The culture of song in the army developed in close tandem with the already successful sheet music industry, and as the momentum of the war effort grew, publishing firms produced numerous war songs. Through song, the military and commercial markets wielded an impressive discursive power to mold the very subjectivities of the people who fought and suffered in the war. In the training of new, inexperienced soldiers (many from families of recent immigrants and many from rural farms), I trace a productive dialectic in the way the subjectivities of the soldiers changed with the gendered identities the military and market promulgated through music, images, words and practices, both pleasurable and painful, constructed and enforced.

Many prominent writers argued that the development of soldiers’ musical skills was crucial to America’s success. Even before America entered the war, music and war was a topic of interest. Fullerton L. Waldo’s 1916 essay “Music and the War” in the weekly news journal The Outlook, writes about the significance of music for all the combatants, including the Germans, in the war. He mentions a U.S. government recruiting poster (before the official declaration of war) that emphasized the importance of music by stating “Men wanted for the United States Army; Special inducements offered to Pharmacists, MUSICIANS, . . and OTHER MECHANICS (sic).”[5] Once soldiers were on the ground in Europe, Walter Spalding, who was then chair of the Harvard music department and also worked with the National Committee on Army and Navy Camp Music, pronounced in The Outlook in June 1918, “Our Government . . . wisely holds that music should be just as much a part of the equipment [of war] as weapons, uniforms and rations.”[6] The CTCA’s idea of music’s functional value resonated with both Waldo and Spalding, and Edward T. Allen, the author of Keeping our Fighters Fit, contradicts doubters of music’s military value when he writes,

A well-known officer said that music is a gratuity, a luxury; practically, it has proved itself to be a necessity . . . Patriotism is no hollow, empty thing. It wins battles. And the music, be it instrumental or vocal that awakens it and feels it is scarcely less potent than high explosives . . . A singing army is invincible.[7]

Given this powerful rhetoric, organizers used songs and band music with serious intent and for constructive purposes only, as the following exchange illustrates. In July 1917, the music company J.C. Deagan Musical Bells, Inc., wrote to the CTCA to advertise the “amusement and entertainment” value of its machine the “Musical Entertainer” for Army camps. The “electric una-fon” was priced at $400 and could be played like a piano. Within days, the CTCA responded that there was “very little prospect that the Musical Bells” would be useful for the military’s purposes; novel musical entertainment was a waste of military resources.[8] Instead, music was to be employed with a specific military rationale, and songs and bands would prove to be better preparation for soldiering. In his chapter entitled “The Fighters who Sing,” Allen writes “the war is gradually bringing about a true realization of the value of music as a factor in increasing a man’s fighting efficiency.”[9]

The sheet music industry responded to Wilson’s call to war. As Frederick Vogel reports, “By midsummer 1917. . . American battle song production had surpassed that of the British and French. . . .”[10] Many songs were not published by major firms, but rather by independent song writers outside of major cities, generated directly by public enthusiasm. In his book, Vogel includes a selection of 35,600 war and patriotic song titles that were copyrighted in the period from 1914 to 1919, only 7,300 of which were published by major firms.[11] My research shows that the published number is even higher. However, the songs published by major publishing houses and featured by popular singers of the day draw my attention in this article because of their visibility and widespread sales.

Gender and War in the Military and Market

The CTCA organized the soldiers’ singing and published the official songbook for the army entitled Songs of the Soldiers and Sailors that contained both American standards, such as “The Battle Hymn of the Republic” and “Dixie,” as well as songs newly popularized by the market, such as “Over There” and “Joan of Arc” (both from 1917). In fact, a third of the songs derive from early twentieth-century Tin Pan Alley and vaudeville hits, such as “Yaaka Hula” (1916) and “Send me a curl” (1917). But the selection also offered a distinct blend of American 19th century ballads (such as “Old Oaken Bucket”), patriotic standards (such as “America”), and British, Irish, and Scottish ballads (such as “Annie Laurie”). The book even presented words to sing with the army trumpet calls, as well as a selection of Union songs, such as the aforementioned “Battle Hymn” and “When Johnny comes marching home,” as well as southern folk songs, including Stephan Foster’s “Old Kentucky Home,” and minstrel songs, such as “Li’l Liza Jane.” Northern and southern, urban and rural, immigrant and non-immigrant songs created the conglomerate image of one type of man: the American soldier. Letters to the CTCA indicate that the general public enthusiastically ordered thousands of copies of this book for local singing groups. And in the fifty-four training camps across the nation, official CTCA song leaders used this book to direct regimental singing on a daily basis and competitive singing among regiments. Official “songleaders” were hired to train the regiments, and they published a monthly newsletter called “Music in the Camps,” where each songleader detailed their activities: from regimental singing to community “sings” and from song competitions to singing for “gassed men.”

Along with this daily regimen of singing, we also find a specific songleader discourse about the military purpose of singing and its detailed physical and mental benefits. In Keeping Our Fighters Fit, Allen cites a song leader from the Great Lakes Naval Training Station who describes “what singing does for fighting men.” As his outline suggests, singing would both improve the body and mind of the individual soldier and enhance the group.

- The Unit

- Teamwork

- Concerted action

- Mental discipline

- Memory

- Observation

- Initiative

- Definiteness

- Concentration

- Accuracy

- Punctual attack in action

- Physical Benefits

- A strong chest, back and lungs

- A throat less liable to infection

- Increased circulation helps to clear nasal cavities

- Strengthens and preserves the voice[12]

While the benefits to unit cohesion are probable and the physical enhancements are somewhat exaggerated, the role of singing in a man’s mental control are of interest here because they become increasingly specific to soldiering, in particular with respect to the attack—singing would literally form the fighting man. The songleader’s outline seems to explicitly demonstrate Michel Foucault’s idea of bodily inscription: through repeated practice, singing would train and improve the actions required of the soldier, while the songs’ lyrics reinforced the values of the war and fighting in his mind.

In the camps, military regimens and strict patterns of behavior formed the very subjectivity of the men, as soldiers. By conformity to these modalities, gestures, and actions, the soldiers’ bodies were shaped or inscribed, in Foucault’s terms, with the military’s masculine ideal.[13] As Foucault writes, “Discipline makes ‘individuals’ . . . [as such,] it is the specific technique of a power that regards individuals both as objects and as instruments of its exercise.”[14] A particularly potent aspect of the American military training in 1917 appears to have been their approach to emotion (or, the “mental” of Wilson’s idea of manhood). Singing offered a subtle yet effective form of inscription, one where the pleasurable act of performing songs incorporated meaningful signifiers of propaganda, while simultaneously being something fun for the man to do. Diligent and repeated practice not only normalized group-singing habits, but also instilled identification with all the modalities and ideologies of war. As Foucault suggests, the military powers “deployed [the] discourses” of song through soldiers’ bodies in practice, and through singing and training, the individual became the soldier the government needed.[15] As such, the organization of singing can be understood as one of the army’s training tools that worked precisely because of repeated practice and the emotional pleasures of singing. Songs did not simply “reflect” patriotic feelings about the new “crusade” (Wilson’s term), but rather through performance they produced emotion, and thereby profoundly influenced the subject’s experience of training and battle.

This discourse about song and soldiering comes at a time in 1917 when the reality of this modern war was not a secret in America: the stagnant battle, fought in thousands of miles of muddy and bloody trenches, had cost millions of soldiers their lives. Many American men had volunteered to fight with the British or the French Foreign Legion in the early years of the war, and thousands of women had already been active behind the lines as nurses.[16] Nurses and soldiers returned to tell the American public what they had experienced. In 1916, Ellen La Motte, an American volunteer nurse stationed in France, had published a startling portrayal of the war in The Backwash of War. Her book gives a graphic account of the death and dying she witnessed and elaborates on the decidedly “unheroic” details of war in a sympathetic, but sometimes sadly ironic manner. In describing daily life in a hospital near the front, she writes of tragic suffering,

. . . So all night Rochard screamed in agony, and turned and twisted, first on the hip that was there and then on the hip that was gone, and on neither side, even with many ampoules of morphia, he could find no relief. Which shows that morphia as good as it is, is not as good as death . . . Thus the science of healing stood baffled before the science of destroying.[17]

The French and British governments censored La Motte’s book immediately. However, it was published and sold in the U.S. until after April 1917, when it was finally banned. Margaret Higonnet comments that because nurses’ writings from World War I, like La Motte’s, “hoped to enable the reader’s resistance to propaganda and [improve her] understanding of the war as a social trauma, the issue of truth is central to their work.”[18] By 1917, reports of the true horror of the front were silenced in favor of stories of bravery, excitement, and heroism.

La Motte’s book, which engages her audience with the abject nature of war—its indescribable pain, its collapse of meaning—was at odds with the needs of the government. La Motte’s novelistic verité, in contrast to Spalding’s confidence, illustrates how the discourse of the meaning of the violence changed as Americans prepared to enter the war. In essays and sheet music, horror is kept a secret and marked as “untruth,” in order to maintain the idea of the heroic battle. And if true suffering is acknowledged, it is marked, in anthropologist Allen Feldman’s words, as “an aberrant cultural difference,” the experience of a barbaric or innocent Europe, one which the U.S. was going to save.[19] President Wilson framed the American entry into the European battlefield as “a war against militarism, a war to redeem a barbarous Europe, a crusade.”[20] The metaphor of a “crusade” crystallized a moral ideal that appealed to conservatives and progressives alike as a way to define the difference of the American fight. Crucial to this new nationalistic drive and the successful recruitment of men was the re-definition of a masculinity for the soldier that was morally righteous and pure, particularly after complaints from the public about the moral indiscretions of soldiers in the Mexican conflict of 1916.

Song writers and music publishers responded enthusiastically to Wilson’s call for a crusade, and they produced numerous new and old patriotic songs as sheet music, rolls for the player piano, and discs for the talking machine. The New York publisher Leo Feist dominated the home market with hit tunes such as “Over There” and “Good-Bye Broadway, Hello France.” Patriotism was Feist’s business, as revealed by an ad for Feist songs printed on the back of one edition of “Good-Bye Broadway” that calls out to the reader in bold letters: “MUSIC WILL HELP WIN THE WAR!” Also included is an enthusiastic essay by “A. Patriot” on the meaning of song to the new soldier and the American war effort. It states,

Songs are to the nation’s spirit what ammunition is to a nation’s army. The producer of songs is an ‘ammunition’ maker. The nation calls upon him for ‘ammunition’ to fight off fatigue and worry . . .

As would be expected, the advertisement refers to the battle itself only through the metonymic markers of “fatigue” and “worry.” Suffering from this modern war’s unprecedented violence (coded here as “exhaustion”) can be relieved through an invigorating dose of musical optimism. Feist also sold a collection of his company’s songs in a book entitled Songs the Soldiers and Sailors Sing for 15 cents. And the advertisement, in glorifying his publication of so many musical favorites, quotes a soldier who had used this songbook. “Zwingli” the soldier writes “from the trenches” about how much “he and his pals appreciated and enjoyed this book” because, he claims, “Nothing makes a man, more of a man, than music.”

While certainly many soldiers enjoyed singing a song from this book, what is more interesting is the point made about masculinity. By publishing this soldier’s comment, whether actual or fictitious, Feist’s ad illuminates the changing status of music for masculinity in American culture after 1900. Music, in these terms, is foundational to “the stimulation of manhood” (to use Wilson’s words). Notably around 1917, song frequently finds definition as a producer of manliness and power, in contrast to the more common perception of music as a female activity in the domestic sphere. As Gail Bederman writes, in the Victorian discourse of “manliness,” the term had invoked a distinctly, white middle-class and “unemotional” idea of “sexual restraint, a powerful will and a strong character.” In the 1890s, white men now cultivated more of the attributes of what was then coming to be known as “masculinity,” such as traits of aggression and physical strength, which earlier in the 19th century had distinguished working–class men from the moneyed middle-class.[21] Now given the need for enthusiastic recruits and brave soldiers, the government, with the help of the market, redefined “manliness” in order to produce a manly and masculine soldier, whose upstanding character fused with the brute force of his maleness.

In many songs, representations of femininity act as a foil, which, as I show, helped to produce this new idea of a soldier’s masculinity. I look first at a selection of two Feist songs included in the CTCA’s Songs of the Soldiers and Sailors, “Over There” and “Good-Bye Broadway,” because both had great popular success, and thus we can assume that most soldier recruits would have been familiar with the sheet music. The third song, “Joan of Arc,” also in the CTCA songbook, was published by Waterson, Snyder, and Berlin, and a fourth song, a Feist song called “My Belgian Rose,” was probably aimed at the home market because of its sentimentality.[22] Like many other songs from the time, all four songs paint an image of America’s role on the European front through a distinctly gendered lens. The first two focus on soldiers’ relationships to the nation and motherland (articulated by references to mothers and sweethearts); and the second two concern the individual’s identification with Europe, through the icon of Joan of Arc and the idea of Europe as “sweetheart” in “My Belgian Rose.”

Four songs in wartime

Through the excitement and fun of its music and lyrics, the song “Over There” captured an image of the war as a game, which appealed particularly to young middle-class white men, whose enthusiasm for sporting events had grown since the 1890s.[23] The song was so popular that it became a defining emblem of the American war effort (gaining almost mythic stature), and George M. Cohan, the writer and lyricist, contributed to its mythology. As Vogel notes, however, Cohan’s “ultraconfidence” (sic) was not misplaced, considering that in 1917 the U.S. had yet to experience defeat in any international or national conflict.[24] Through popular stage performances, sheet music sales, and recordings, the song acquired meaningful wartime sentiment with its specifically gendered discourse.[25]

To underscore the potency of the musical propaganda and gendered significance of these relatively simple songs, I adapt Kristeva’s psychoanalytic and semiotic concept of the signifying processes of speech to illuminate the role of gender representations. For Kristeva, a pre-verbal semiotic “motility” of the subject’s body inflects signification in speech, and through the act of speaking, it helps produce the subject’s emotional experience and knowledge.[26] I hold that singing, shaped by this gestural motion, embodies this current of semiotic motility, and as such, the “play” of the singing voice operates in dialectic with the symbolic forms that govern language. Kristeva’s situated semiotic lens and her ideas about the Western meanings of motherhood and femininity allow me to frame and analyze these songs as social practice and to underline the power of propaganda in a song.

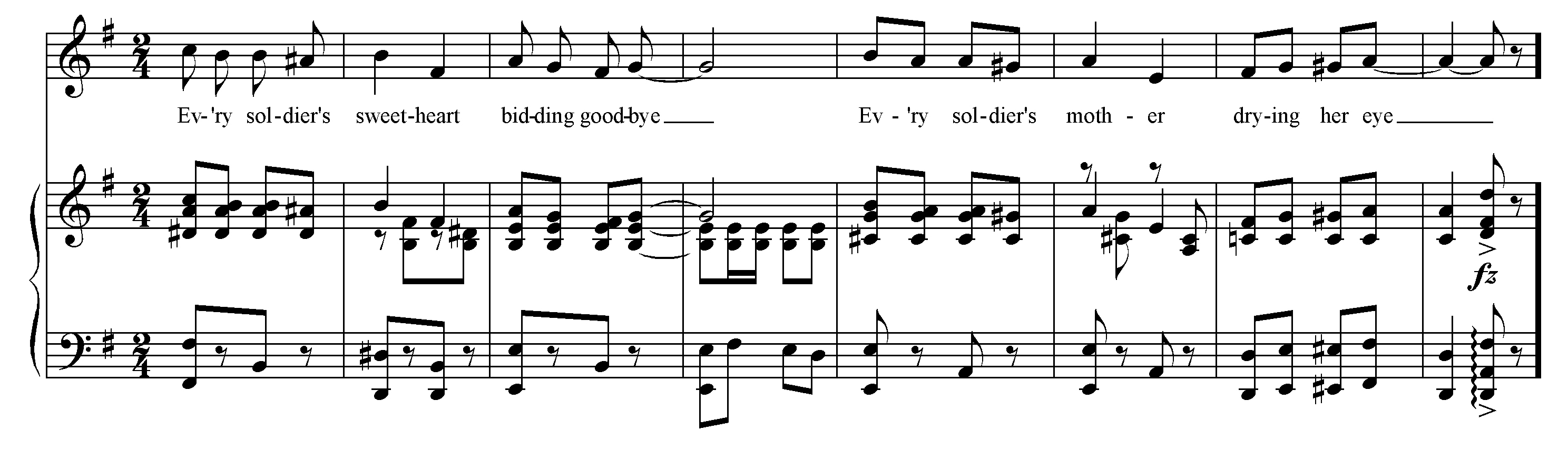

Set in a jaunty march, “Over There” offers the fun and “play” of the participation in war, as eighth-note melodic patterns carry the rhyme and repetition of the lyrics: “Johnnie get your gun, get your gun, etc.” (see Example 1).[27] The opening line is playful; it de-emphasizes the semantic and foregrounds the phonic such that the play of the voice is a pivotal experience in producing the emotion of the singer. The fun of “the game of war” is produced by an energetic motility in the syllabic and rhythmic singing, which then infuse the gendered icons embedded in the lyrical passage with great emotive potential. After the running eighth notes break into an arching melodic line, the singer moves in a steady quarter-note pulse on “Hear them calling you and me” and resolutely down an accented passage of fifths on “Every son of Liberty.” Of course, the icon of “liberty” metaphorically refers to not only the American ideal, but also indexes the relatively recent construction of the Statue of Liberty, whose gendered identity configures her as Mother and Nation in one. Furthermore, the first chromatic chord of the song colors the word “Hear” (with a G# passing tone creating a diminished VII of VII) and adds the motility of the bending pitch to the vocal experience (See Example 1). This phrase returns eight bars later: “Tell your sweetheart not to pine; To be proud her boy’s in line,” which leaves a sense of pride resounding. Indeed, the broader quarter-note values here invite the singer to improvise on the line’s affective quality while on the march or in the trenches (and here I am thinking of singers like Dwyer who would have repeated melodic phrases and used full vocal production while on the march). Finally, the catchy chorus echoes the rising fourths of the U.S. army’s bugle assembly call as it was played at the time.[28]

These detailed emotive effects highlight the psychological consequences of the government’s use of singing. When Sergeant Dwyer tells us that “[Singing] used to buck us up and we would march all the better for it,” he speaks about a very basic joy. For the army, this joy is precisely the practice that deploys the symbols of mother, nation, and sweetheart, which are merged into the militaristic aim, one tightly linked to the other. Through the emotive references to femininity and to the protection of feminized symbols, the soldier’s masculinity emerges as a composite of both the aggressive and morally upstanding man. The words impart a normative discourse, which in psychoanalytic terms embody the voice of the Father/the Law. In the dialectic of symbol and motility, the singing reinterprets and obscures the abject nature of war with its familial significance and the pleasures of the game.

Period recordings of “Over There” from the Cylinder Preservation and Digitization Project:

- Billy Murray, 1917 (Edison Blue Amberol 3275): http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder4470

- Peerless Quartette, 1917 (Indestructible Record 1556): http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder4074

- Indestructible Male Quartet, 1917? (Indestructible Record 3412): http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder4137

While the personal experience of singing songs like “Over There” certainly recalled soldiers’ own mothers and sweethearts, I would like to examine the societal implications of motherhood in a Christian nation that grounds the ideological implications of these songs. The chromatically produced symbols of woman index the idea of the suffering Mother, which has historically played the role of bearer of pain. With deep roots in the story of the Virgin Mary, the Christian trope of woman works as an icon for the grief of war. Mary’s identity is unique for this purpose. While Christ is only “human” through his mother, Mary, because she is Christ’s mother, is purged of sin, and therefore she is neither fully human, nor truly divine. As one of the most powerful ideological constructs in Western civilization, the weeping Virgin Mary defies both sex and a human death and is thus a powerful icon in the face of war. As Kristeva points out in her essay Stabat Mater, Mary represents not only the archaic mother, but more accurately the individual’s relationship to the idea of motherhood.[29] The trope of woman works as an icon of love, an emblem of piety and as an image of power in the semiotic discourse of these songs.

The Committee on Public Information (also called the Creel Committee for the dominant leadership of George Creel) established the Department of Pictorial Publicity in order to generate war propaganda posters for display and distribution in magazines. To parallel the importance of the Mother icon in these songs, I examine briefly one of the most successful American war posters that employs the Marian metaphor to great effect. The Boston Committee on Public Safety printed the poster “Enlist” in 1915 in response to the sinking of the Lusitania (See Figure 1).[30] While its origins in Boston, given the city’s Catholic population, perhaps explains the Marian symbolism, the popularity and longevity of this poster, as indicated by its revision and reuse during the Second World War, makes its symbolism noteworthy. With a child cradled in her arms, the ghostly figure of motherhood descends, suspended in dying. She hovers in a sacred space that embodies both the viewer’s anguish and defiance. As Kristeva suggests, the Marian figure is equally a “shield against death” and “the surge of anguish” at its oblivion, and here it functions as a potent call to join the fight.[31] In this respect, the specific icon of femininity in the “Enlist” poster spoke to the emotional needs of the nation and appealed to the idea of a cherished motherhood, which was also found in sheet music, such as “That wonderful mother of mine,” “So Long Mother” (also popularized as “Al Jolson’s Mother Song”), and “I am fighting for country, for you and little Nell,” which address both mother and sweetheart. Interestingly in the 1910s, these images of womanhood replaced the famed “Gibson Girl” from the turn of the century, as suffering was now the necessary marker for a woman’s gender, no matter how youthful.[32] As songs published during 1917-1918, they contrast sharply with the 1915 song “Don’t’ take my Darling Boy Away” that expressed the sentiment of pacifist non-engagement more prevalent then.

In the song “Good-bye Broadway,” gendered sacrifice again frames the camaraderie of war. Referring to “Miss Liberty” in the lyrics, the song introduces the first chromatic passing chord before “sweetheart,” paralleled by the “weeping mother” in the next phrase; and in both cases, the words “sweetheart” and “mother” are broken over a lamenting descending-fourth. As icons of womanhood, their suffering delineates the limits of the public discourse on pain and violence, while the exuberant excitement reinforces the “play” of warfare. In keeping with the gender ideology, the emotional weight of war is figuratively born by woman, and the trope of the suffering woman, while not misplaced or unusual in the history of warfare, is significant here for its commercialism and its military use in song.

The chorus carries a stately main tune with words that encompass the multitude of “ten million men,” as the mass identity of the individual soldier. The lyrics go on to “explain” the fighting: “Good-bye sweethearts, wives and mothers, It won’t take us long/ Don’t you worry while we’re there, It’s for you we’re fighting for/ So Good-bye Broadway, Hello France, We’re going to square our debt to you.” Chromatic passing chords again color the affect on the soldier’s relationship to femininity, with the words “sweetheart” and “mother” in the first verse and in the line “It’s for you we’re fighting too,” which moves to a suspended resolution on B major (the mediant of the tonic G major) (See Example 2). While the second verse does not contain lyrics about femininity, this fact does not counter the significance of the chromaticism used when women are mentioned. Notably, in the second repeat of the chorus the singer is instructed to “ad lib” on a new syllabic setting: “It’s you we’re fighting for.” The attention encouraged here underscores the gendered “reason” for the war with particular emphasis. In immediate contrast, the syncopated rhythm of “Hel-lo France” puts the “fun” back into the song and into going off to fight. Here, the emotional weight of war is born by woman, as she is figuratively called upon to bear the burden of war’s pain.

Period recordings of “Good-bye Broadway, Hello France”:

- Arthur Fields and Chorus, 1917 (Edison Blue Amberol 3321): http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder5627

- Peerless Quartette, 1917 (Indestructible Record 3418): http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder4138

- Jaudas’ Society Orchestra, 1918 (Edison Blue Amberol 3363): http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder5600

In the discourse of war, the soldier himself was a small and replaceable factor within the larger plans of battle. In fact, the First World War has been called “a war of generals,” where the soldier, while hailed as a hero, was often treated as a peon, an expendable body, who was less than a subject. And even while the song “Good-bye Broadway” produces excitement about coming to help France, the sheet music cover symbolically reveals the true nature of the army, with generals depicted as giants and the machinery of war displayed as toys; the men are no where to be seen. We can compare this to a Red Cross poster, adopted from the British Red Cross and used in America, where the depiction of the wartime nurse emphasizes her devotion to the succor and aid of the soldier. Her posture exemplifies the Virgin Mary in Michelangelo’s Pietá, as the Western emblem of feminine piety and sorrow. But in contrast to the collapsed pose of Michelangelo’s Mary, the British nurse gazes resolutely forward, with the invalid soldier as the child in her arms (See Figure 2). In the discourse of these posters and songs, woman mediates the soldier’s suffering and operates as a symbol of strength in the face of utter weakness. As Kristeva tells us, traditional femininity is “consecrated as motherhood,” as the “fantasy” of the relationship to the primary self in an “idealized...narcissism.”[33]

Indeed, the new discourse of war encouraged the soldier’s appropriation of some tropes of femininity in order to become the fighting American man. The song “Joan of Arc,” written by Jack Wells, was printed as lyrics in the CTCA’s Songs for Soldiers and Sailors. Joan of Arc presented a unique symbol for the soldier’s endurance in this war, and photographs from the time show American and French soldiers visiting Le Bois Chenu, or the “Oak Wood,” where she is said to have had her visions. Joan of Arc, as symbol, evokes similar tropes of power to the Virgin. As a young woman, she is weak, but both her piety and her virginity make her strong. In her submission to duty, she offered soldiers a model in her abjection of self, in her willingness to sacrifice her life for the nation as the “ultimate proof of [her] humility before God.”[34] Motivated by their duty to France, the soldiers’ identification with Joan helped make sense of their own fears of warfare and very real potential for death.

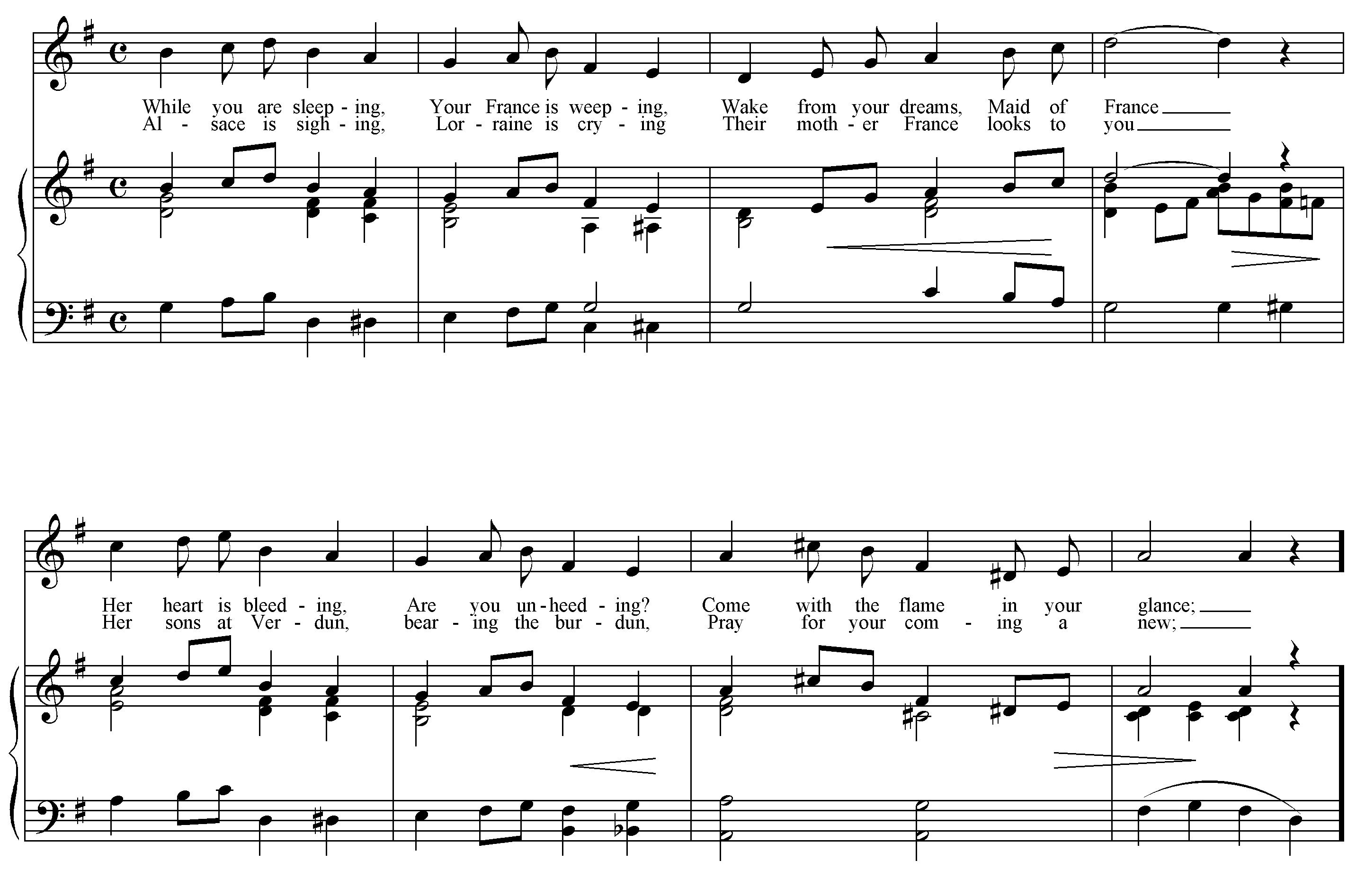

Despite this symbolic weight, the popular song “Joan of Arc” particularly evinces the “kitsch,” to which many of these war songs seem to aspire. Its producers appear to have been hasty in building its musical formulas, down to a brief quotation of “La Marseillaise” stuck in at the end, and formulaic harmonies carry the singer through trite rhyme schemes, such as “bleeding” and “unheeding,” and “Verdun” and “bur-dun” (See Example 3). As Adorno writes, “kitsch is essentially ideology . . . [it] is used to deceive people about their true situation . . . to allow intentions that suit some powers . . . to appear . . . in a fairy-tale glow.”[35] These songs operated through a collective American subconscious familiar with its sentimental musical tropes—tropes that now modulated their religious and even romantic understanding of war, as the next song reveals.

We find that the CTCA not only standardized soldiers’ emotions about suffering and duty, they also attempted to regulate the most personal experience of love: sexuality. On one hand, this regulation had a serious and pragmatic purpose. According to reports from Europe, the spread of venereal disease forced Allied authorities to decommission hundreds of thousands of troops. Furthermore, in response to letters from parents, who worried about army life “ruining of their [sons’] bodies and ideals with alcohol and illicit sexual relations,” Wilson charged the Commission with the major task of monitoring soldiers’ sexual lives.[36] Thus, the CTCA needed to boost men’s masculinity, without enhancing the sexual prowess associated with its force. As historian Alan Brandt puts it, the reformers in the CTCA defined the new masculinity as “powerful yet pure, virile yet virginal.”[37] Another edition of “Over There” captures this masculine but virginal man quite directly, and it is apparent that this idea of masculine sexuality had spread into the commercial sector. His hairless aspect, and rosy lips and cheeks heightened the de-sexualized image of this “common” soldier, whose virginal appearance appealed to parents and superiors alike (see Figure 3).

Period recordings of “Joan of Arc, They Are Calling You”:

- Vernon Dalhart, 1917 (Edison Blue Amberol 3323): http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder5569

- Irving Gillette, 1917? (Indestructible Record 1560): http://www.library.ucsb.edu/OBJID/Cylinder4076

An official CTCA pamphlet for soldiers extols the virtues of a fighting “virile” abstinence:

[...] You are going to fight for the spirit of young girlhood raped and ravished in Belgium by a brutal soldiery. You are going to fight for it in this country too, where you yourselves are its protectors, so that it may never need to submit to the same insults and injuries.

But in order to fight for so sacred a cause you must be worthy champions. You must keep your bodies clean and your hearts pure.

It would never do for the avengers of women’s wrongs to profit by the degradation and debasement of womanhood.

Every hardened prostitute who offers herself to you was a young girl once till some man ruined her. If you accept her, you are shaming all girlhood.

Above all you are shaming and insulting the girl you hope to marry some day, and who is waiting for you here at home, whether you have found her yet or not.

... Put this picture in you knapsack so that it may make you think at all time of the girls, like your sisters, who have suffered in this war, and of THE GIRL YOU LEAVE BEHIND YOU [sic].[38]

Their words tie the “clean [sexual] body” directly to the “fight,” such that the rhetoric illustrates a striking conflation of purity with aggression, connecting to the trope of Joan of Arc and linking pure violence with a pure sexuality.

Some popular songs resonated with this message about fighting “cleanly.” For example, the song “My Belgian Rose” moralized the soldier through a sentimentalized love for the beautiful and the innocent. As noted above, this song was not listed in the CTCA’s songbook; however, the participation of men in singing at home offers a place for them to have engaged with the feelings expressed here. In the cover image of “My Belgian Rose,” the sweet and smiling “Yvette” (the singer who popularized the song) becomes the object of adoration. When the piano announces the affect of sentimentality with the VI7 chord (in measure 2 of the introduction), the singer prepares for the song’s pathos. Musical details construct the emotion: the voice sings a rising appoggiatura to C on “drooping so low” over a momentary harmonic disjunction in the piano (G major implied in the bass, with an F major chord above), and this produces the subjective feeling of “drooping” for the singer. The next phrase then identifies the CTCA’s “young girlhood raped and ravished in Belgium” with the line: “robbed of your sunshine, you’re fading away.” The Marian symbol of the Rose as nation evokes a feminine ideal, which directly contrasts to the prostitute of the CTCA pamphlet. “Fighting cleanly” means chivalrously loving your “girl” as you would the Virgin. And in the second verse, a passing augmented dominant chord (at the end of the third measure) tugs at the frightening line: “Then came the tyrant with sword in hand.” It is the young virgin who droops and suffers, as there is no discourse on the brutality men experience as soldiers; instead, it is replaced and reinterpreted by the more common trope of brutality to women.

Music’s value in wartime

The emotive practice of singing formed the subjectivity of soldiers and cemented the necessary and exaggerated “truths” about the war in the soldier’s mind. But music’s value was defined differently by the government and the soldiers. As we may expect and as some records suggest, not all soldiers fell in line with the required vocal participation in joyous propaganda. In the summer of 1918, Charles Washburn, a Y.M.C.A. song leader stationed in France wired this message back to the United States. Along with reports from other song leaders, it was published in “Music in the Camps.”[39] He writes,

Our rest camps here hold the boys for only a short time, less than a day sometimes, so that the hours are filled with stocking up on smokes and sweets[,] and it is only the groups that have been trained to sing back home that respond quickly to the call to sing. Yesterday, we had some men from Camp Dix and wonderfully did they show the results of their training there. Keep up the intensive song singing at home. It is too late to take it up here.[40]

Washburn’s warning “it is too late” acknowledges the reality of preparations on the eve of battle. But it also suggests a lack of adherence, perceived in some soldiers, to the desired soldier identity, that is, a man who would participate just as enthusiastically in song as he did war. In Foucault’s terms, this military assumption underscores the “docility-utility” function of military discipline, here the discipline of singing.[41]

Washburn’s report reveals a tension between the individual’s perception of song and the “rationalization” of music as a tool of power. As Adorno writes on similar popular songs, “such music is constructed on the foundation of a romantic concept of primitive musical immediacy . . . [such that it] might be taken as . . . a music [that is] the property of free men.”[42] And as my discussion and analyses show, the most effective means to manipulate the soldier through song was to deploy musical affect and potent symbols of woman to construct the masculinity of the enlisted man. These symbols negotiated and deferred suffering; they produced obedience and self-sacrifice; and they shaped the male subject’s experience of aggression, sexuality, and love. Many soldiers were enthusiastic about popular song, but for some the “illusion” of a song’s personal meaning and the discourse of its power to build him into the fighter would have eventually produced a severe disjunction between, on the one hand, actual experience on the battlefield and, on the other, the “empirical consciousness” (to quote Adorno) that such songs fostered.

When the Armistice finally came, singing also provided the means of celebration for those returning and comfort for the millions of families whose loved ones did not return. As CTCA reports indicate, the practice of singing quickly adapted to the more pressing needs of healing. The issue of “Music in the Camps” from November 16, 1918 focused on singing Christmas music “for men in the camps” and for those “who are now in our hospitals.” Not surprisingly, the discourse about singing’s virtues continued, as is evident from “Music in the Camps” issues from late 1918 and early 1919. The February 22 bulletin from 1919 outlined the “Plan for military singing in demobilization camps,” which still involved “singing by company battalion or regiment at least two times a week.” Even into the summer of 1919, singing provided succor for the wounded, as Robert Lloyd reports from Camp Lewis, Washington, “This week has been mostly devoted to tone lectures at the Base Hospital . . . My audience have been gassed men . . . The interest is the keenest yet accorded me.” An essay entitled “The Military Value of Singing” from “Music in the Camps” July 1919 provides a retrospective on singing in the war, and the author comments on the surprise young recruits first felt when they found “singing . . . would be included in the intensive war making schedule [with] a song for every occasion ready to pack in his ‘old kit bag.’” He notes the songleaders’ formative influence: “The Army Songleader [sic] is a product of the war—he did not exist before, and it is due largely to his initiative and perseverance that singing has come to be recognized as the super-discipline [sic] of the army. . . .”[43]

My discussion illustrates how musical practices in social conflicts become a highly gendered means to reinforce difference and delineate violence, molding both subjective and social perception. Before the war, many Americans considered music at the piano at home a means to produce moral behavior.[44] During the war, that same idea of music’s moral force shaped the subject’s understanding and experience of war’s violence. This is one reason why song practices offer us such a powerful and incisive lens into American discourses of identity at this time.

In conclusion

As Simon Frith argues about contemporary popular song, “Pop love songs do not ‘reflect’ emotions . . . but give people the romantic terms in which to articulate and so experience their emotions.”[45] The artifice and melodrama in these and other American songs from the First World War gave people the gendered and emotional (if not always rational) terms with which to negotiate stories of pain and valor from the far off battlefield. But, as with love songs, serious problems arose when reality turned out to be shockingly different. For soldiers, the songs obscured the anarchic space of the European battlefield with the “cultural anesthesia” of their musical style and imaginary game of war.[46] Later, popular war songs, once a part of the U.S. regimen of war, appeared in retrospect to soldiers and historians as a sign of naiveté. As R. Jackson Marshall writes, “World War I was perhaps the last American war in which the soldiers went into the fight with a song on their lips.”[47] And anecdotal evidence suggests that once on the battlefield, soldiers revised the songs and created their own lyrics about the reality of war. In one rare story about what the soldiers actually sang on the front, American soldiers, trained in the expressive tool of song, changed the refrain of “Over There,” the Doughboys’ favorite marching tune, from “we won’t come back ‘til it’s over, over there” to “we won’t come back, we’ll be buried over there,” and it is easy to imagine, given Dwyer’s style, what greater modifications the song underwent.[48]

Notes

Glenn Watkins provides an in-depth study of musical culture, both art music and some popular music, during the First World War in America and the European countries involved. However, he does not address subjective experience or discursive production of meaning in this context. See Glenn Watkins, Proof through the Night: Music and the Great War (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2003). My research on popular song and the military more closely compliments works such as Regina Sweeney, Singing Our Way to Victory: French Cultural Politics and Music During the Great War (Middleton, CT: Wesleyan University Press, 2001). I also take inspiration from ethnomusicological studies of music and violent conflict, which develop a deeper understanding of discursive context and subjective experience. See, for example, Louise Meintjes, Sound of Africa! Making Music Zulu in a South African Recording Studio (Durham: Duke University Press, 2003).

William E. Matsen, The Great War and the American Novel (New York: Peter Lang, 1993), 2.

Sgt. Edward Dwyer. Recorded in 1916. Victoria Cross winner, 1st Bn. The East Surrey Regiment. Excerpt from The Great War: An evocation in music and drama through recordings made at the time, Gemm, 9355, compact disc, track 8.

See Wilson’s “Special Statement” in the opening of Edward Frank Allen, Keeping Our Fighters Fit for War and After (New York: The Century Co., 1918).

Fullerton L. Waldo, "Music and War," The Outlook 112 (1916): 151.

Walter Spalding, "Music as a Necessary Part of the Soldier's Equipment," The Outlook (June 5, 1918): 223.

Edward Frank Allen, Keeping Our Fighters Fit for War and After (New York: The Century Co., 1918), 82-83.

These letters are in the National Archives, “Music in the Camps,” RG 165, Box 56, Entry 399.

Frederick G. Vogel, World War I Songs: A History and Dictionary of Popular American Patriotic Tunes with over 300 Complete Lyrics (Jefferson, NC and London: McFarland and Company, Inc., 1995), 41.

Michel Foucault, Discipline and Punish: The Birth of the Prison, trans. Alan Sheridan (New York: Vintage Books, 1977), 135-69.

For a further discussion of Foucault’s idea of deployment in relation to gender, see Elizabeth Grosz, Volatile Bodies: Towards a Corporeal Feminism (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1994), 149.

On American men who volunteered for France, see Robert B. Bruce, A Fraternity of Arms: America and France in the Great War, Modern War Series, ed. Theodore A. Wilson (Lawrence: University of Kansas Press, 2003). Also, an estimated 25,000 women volunteered in the early years of the war to help in France. For more on these nurse volunteers, see Gail Collins, America's Women: Four Hundred Years of Doll, Drudges, Helpmates and Heroines (New York: Harper Collins Publishers, Inc., 2003), 299-303.

Ellen N. La Motte, The Backwash of War: The Wreckage If the Battlefield as Witnessed by an American Nurse (New York: G.P. Putnam's Sons, 1916), 53. She writes of the nurse on duty in the third person and captures the deep irony of the “general’s war,” describing the work as “months of boredom punctuated by intense fights.”

Margaret R. Higonnet, ed., Nurses at the Front: Writing the Wounds of the Great War (Boston: Northeastern University Press, 2001), xxi.

While Feldman’s essay is concerned particularly with violence as mediated in late modernity, his insights into the cultural perceptions of violence are applicable here as well (Allen Feldman, "From Desert Storm to Rodney King Via Ex-Yugoslavia: On Cultural Anesthesia," in The Senses Still: Perception and Memory as Material Culture in Modernity, ed. C. Nadia Serematakis [Boulder: Westview Press, 1994]).

Nancy K. Bristow, Making Men Moral: Social Engineering During the Great War (New York: New York University Press, 1996), 7.

Bederman writes on the middle-class ideology of manhood: “. . . in 1917, . . middle-class Americans were equally likely to praise a man for his upright ‘manliness’ as for his virile ‘masculinity’” (Gail Bederman, Manliness and Civilization: A Cultural History of Gender and Race in the United States, 1880-1917 [Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1995], 18).

Originally called Seminary Music, the publishing trio of Waterson, Snyder and Berlin (founded in 1909) included publisher Henry Waterson, song composer Ted Snyder and Irving Berlin, who was originally hired as lyricist. See Phillip Furia, Irving Berlin: A Life in Song (New York: Schirmer Books, 1998), 27, 30.

As historian John Higham informs us, the “urge to be young, masculine, and adventurous” in the 1890s was a direct response to the “routine” and “dullness” of “urban-industrial culture” (John Higham, "The Reorientation of American Culture in the 1890s," Writing American History [Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1970], 79-80).

The singer Charles King introduced the song in New York in 1917, and then the singer Nora Bayes made a recording of “Over There” for disc for the Victor Talking Machine Company in New York in July 1917, and along with Feist’s sheet music publication, these performances spurred national distribution. Enrico Caruso purportedly also performed the song in front of a large audience in Central Park in September 1918. See David Ewen, American Popular Songs from the Revolutionary War to the Present (New York: Random House, 1966), 234.

Julia Kristeva, Revolution in Poetic Language, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1984), 27.

The fact that Cohan borrowed these words from a popular song from 1886 connects the war lyrics to the late 19th century era, giving it an “authentic” American identity (notably, in a country now more diverse with distinct immigrant communities). However, the sheet music also often incorporated French lyrics under the English, presumably to promote a direct and personal association with the cause.

Extensive notation of bugle calls for army drills from the time can be found in the Complete United States Infantry Guide (Philadelphia: J.B. Lippincott Company, 1917).

Julia Kristeva, "Stabat Mater," in Tales of Love, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1987), 243.

Maurice Rickards, Posters of the First World War (New York: Walker and Company, 1968), 21. For more on the Creel Commission, see Larry Wayne Ward, The Motion Picture Goes to War: The U.S. Government Film Effort During World War I, Studies in Cinema, ed. Diane Kirkpatrick, vol. No. 37 (Ann Arbor: UMI Research Press, 1985).

The “Gibson Girl” was a youthful icon of femininity popular before the war, who embodied feminine Victorian ideals, but also expressed a certain spark of energy and personality. See a collection of Charles Dana Gibson’s drawings in Edmund Vincent Gillion, The Gibson Girl and Her America (New York: Dover Publications, Inc., 1969). By the time America entered the war, several songs were written directly for suffering mothers on the home front: e.g., “My Baby Boy.”

Julia Kristeva, Powers of Horror: An Essay on Abjection, trans. Leon S. Roudiez (New York: Columbia University Press, 1982), 5.

Theodor Adorno, “Kitsch,” in Essays on Music, trans. Susan H. Gillespie, ed. Richard Leppert (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2002), 502. The essay was originally published in 1932.

Excerpted from a letter to Wilson that reveals the public’s fear that the training camps would lead to the moral degradation of soldiers. See Bristow, Making Men Moral, 12. Also, on the discourse around venereal disease at this time see Allan M. Brandt, No Magic Bullet: A Social History of Venereal Disease in the United States since 1880 (New York: Oxford University Press, 1987).

Brandt describes here the “new male sex role” in the social hygiene campaign called “Fit to Fight” (Brandt, No Magic Bullet, 69).

Draft of a pamphlet, “The Girl you leave behind you,” RG 165, Box 85, doc. 34991, entry 393 at the National Archives.

The Y.M.C.A. collaborated closely with the CTCA in the war training effort.

In the folder “Music in the Camps,” July 6, 1918. National Archives, RG 165, Box 56, Entry 399.

See Adorno’s essay “On the Situation of Music” (1932). He writes on commercialized popular music that “such music is constructed upon the foundation of a romantic concept of primitive musical immediacy which gives rise to the opinion that the empirical consciousness of present-day society—consciousness promoted in unenlightened narrow-mindedness and, indeed, promoted even to the point of neurotic stupidity in the face of class domination for the purpose of the preservation of this consciousness—might be taken as the positive measure of a music no longer alienated, but rather the property of free men” (Adorno, Essays on Music, 394).

All quotes from “Music in the Camps” in RG165, Box 56, Entry 399 in the National Archives.

Craig H. Roell, The Piano in America, 1890-1940 (Chapel Hill: The University of North Carolina Press, 1989), 18-19.

Simon Frith, "Why Do Songs Have Words?" Contemporary music review, Music and text (1989): 80.

R. Jackson III Marshall, Memories of World War I: North Carolina Doughboys on the Western Front (Raleigh: Division of Archives and History North Carolina Department of Cultural Resources, 1998), 29.

See The Great War: An Evocation in Music and Drama through Recordings Made at the Time, Pavillion Records, Sussex, 1989.