Sparking a Commitment to Social Justice in Asian American Studies

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

ASAM 230—Civic Engagement Through Asian American & Pacific Islander (AAPI) Studies is a critical service learning course that effects social change by fostering students’ leadership, activism, and professional aspirations. Our team (a professor and six alumni, some of whom became community partners) conducted a longitudinal, autoethnographic self-study centering social justice in the scholarship of community engagement. Making scholarly choices aligned with Asian American studies’ goals to transform higher education and society, we centralize AAPI counter-narratives as people of color whose voices are neglected in educational research, challenge assumptions of what “community” means in community-engaged scholarship, and employ intersectionality and critical race theory as analytical lenses to expand what knowledge is valued. We found that the course’s curricular elements and focus on community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful power sparked the alumni’s reflective consciousness, leading to their intentional commitment to effect social change through their personal and professional lives.

How does a critical service learning course in Asian American studies[1] (AAS) effect social change? Our team (a professor and six alumni, including three who became community partners) conducted a four-year autoethnographic self-study to examine the relationship between the students’ taking Asian American Studies (ASAM) 230—Civic Engagement Through Asian American & Pacific Islander (AAPI[2]) Studies at California State University, Fullerton (CSUF) and their leadership, activism, and professional aspirations. We found that the course’s purposeful focus on expressing the values of community and community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful use of power sparked the students’ consciousness, contributing to their intentional commitment to effect social change through their personal and professional lives.

Noting the course’s positive outcomes, the professor, community partners, students, and colleagues have collaborated to examine ASAM 230’s partnerships, pedagogical approach, and impact (Tran, Treviño, Tran et al., 2012; Yee, 2020; Yee & Cheri, 2018–2019). Emerging from our research is a picture of a “social justice ecosystem” composed of interrelated university faculty, departments and centers, community activists and community-based organizations (CBOs), students, and alumni. Our service learning partnerships have become a “multi-generational pathway for leadership and community-organizing development” (Yee, 2020, p. 46). As a hub of this ecosystem, ASAM 230 acts as a curricular medium through which we are building capacity to teach, learn, and address social justice issues in our university and communities. Our article details a component of this ecosystem by specifically examining how the course impacted our alumni’s development as leaders and activists committed to social change. Our research adds to previous studies of ASAM 230 community-university partnership sustainability (Yee & Cheri, 2018–2019) and ASAM 230 as a manifestation of the social justice project of Asian American studies and an exemplar of critical service learning (Mitchell, 2008; Yee, 2020).

ASAM 230 is the first designed (not adapted) service learning class to be approved for general education status in CSUF’s history (Yee & Cheri, 2018–2019). This 15-week semester course was co-created in partnership between Dr. Jennifer A. Yee and partners at the Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance (OCAPICA) from 2008 to 2010 (Yee & Cheri, 2018–2019). The class “calls for students to reflect on their life purpose relative to the mission of Asian American Studies while serving with an affiliated community-based organization” (Yee, 2020, p. 41).[3] Designed to immerse students in enacting the field of Asian American studies’ vision of community-university partnerships to serve community, ASAM 230 required students to serve four hours per week for 10 weeks (Weeks 5–14) of the semester in OCAPICA’s after-school mentoring program at a local high school. Our partnership focused on creating a seamless opportunity for college and high school students to interact. We aimed to demystify “college” and teach students how to form social bonds essential to building social networks and community strength (Tran, Treviño, Tran et al., 2012).

OCAPICA partners established a service/field curriculum that invited ASAM 230 students to learn how the program was created and managed by participating in OCAPICA’s administrative activities while also contributing to the program’s impact by directly engaging with the high school students. CSUF and high school students developed reciprocal relationships through tutoring; engaging in creative/fun fitness activities; chatting about high school, college, and family life; mentoring (e.g., supporting the high school students as they completed college and FAFSA/California Dream Act applications, responding to the high school students’ journal reflections, and designing and facilitating formal lesson plans on health). With service fully incorporated into the curriculum, ASAM 230 students’ reflections analyzed the purposeful integration of their course content and service experiences. Through this study, our alumni authors learned that articulating their purpose and values—coupled with learning how to enact values in practice through service—sparked their conscious personal and professional choices to kindle social change.

In this article, we centralize social justice in the scholarship of community engagement by offering our definition of social justice and our study’s contextual and conceptual frames. We describe ASAM 230’s context and creation. Then we share who we are, how we studied ourselves to understand the course’s impact on our development, what we found, and how we found it. We situate our relationships through ASAM 230 and explain our methodology: a collaborative autoethnography leading to theory generation. To present our findings concisely, we introduce an evolving visual model capturing our theory for how ASAM 230 contributes to social change through student and alumni growth. We explain the model with narratives asserting how ASAM 230 helped us to shape our identities and embrace values of community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful power. Throughout, we center social justice in the scholarship of community engagement by inserting our AAPI counter-narratives as people of color whose voices are underrepresented in educational research, making scholarly choices aligned with Asian American studies’ social justice goals to transform higher education and society, challenging assumptions of what “community” means in community-engaged scholarship, and employing intersectionality and critical race theory as analytical lenses to expand what knowledge is valued. We discuss our study’s contributions and implications and conclude with specific recommendations for centralizing social justice in future community-engaged scholarship.

Context/Conceptual Frameworks

Centralizing Our Voices to Enact Social Justice

Social justice is embedded in our nation’s foundational fabric; we must name and resist tyranny and oppression, especially in governance, that compromises our society’s members’ safety, freedom, and equitable access to participate and make decisions democratically, to learn and grow, to share the power and work of the society, and to fairly benefit from its rewards. To us, social justice is the value that both (a) names society’s inequities that contradict these principles and (b) seeks to rectify these injustices through the process of social change.

Foregrounding our voices centralizes social justice in the pedagogy and scholarship of community engagement through the value of equity. As Mitchell and Rost-Banik (2017) note:

Knowing that the assumed service learner is White (Butin, 2010; Green, 2003), and that the majority of service learning research (and most higher education research) takes place at predominantly White institutions (Seider, Huguley, & Novick, 2013), it is important to acknowledge the unequal power relations inherent in service learning (Peterson, 2009). (p. 189)

Educational research has a long history of excluding AAPIs’ experiences (Chan & Wang, 1991; Hune & Chan, 1997; Museus et al., 2013; Nakanishi & Nishida, 1995; Osajima, 1995; Poon & Hune, 2009; Teranishi et al., 2010; Yee, 2001). Because our intersectional perspectives as students, community partners, and members of AAPI communities are usually not assumed nor represented in traditional service learning and engaged scholarship, the presence of our voices and narratives challenges this scholarly erasure. As hooks (2015) asserts, “Oppressed people resist by identifying themselves as subjects, by defining their reality, by shaping their identity, naming their history, telling their story” (p. 43). As faculty, students, and community partners who originate from and identify with the racialized and historically marginalized communities with whom we serve, we offer unique standpoints on the impact of service learning designed intentionally within Asian American studies, an academic field created to achieve social justice through social change (Hune, 1989; Yee, 2020) and offered at CSUF, a Hispanic-Serving Institution (HSI) that also meets Asian American and Native American Pacific Islander–Serving Institution (AANAPISI) criteria. We exercise power to write about ourselves in ways that people who do not share our experiences or social positions might “other” us through their own privileged lenses (hooks, 2015). To counter this scholarly inequity, we view our insiders’ perspectives, roles, and community membership as assets of “community cultural wealth” (Yosso, 2005, p. 75).

Likewise, we intervene in community-engaged scholarship through the social justice value of access by creating knowledge written clearly for students, community partners, university practitioners, and scholars. We are frustrated by research written by and for academics using language and theory “to establish a select intellectual elite and to reinforce and perpetuate systems of domination, most obviously white, Western cultural imperialism” (hooks, 2015, p. 40). We seek to generate understandable ideas and knowledge in a scholarly article made accessible with visuals and words that unpack conventional academic jargon.

Finally, our primary purpose is to document our shared experiences in ASAM 230, a course focused on AAS’s long-term social justice project of social change. In contrast to the now standard goals of accountability and achieving measurable student learning outcomes in higher education,[5] the historical purpose of Asian American studies is, according to Hune (1989):

the documentation and interpretation of the history, identity, social formation, contributions, and contemporary concerns of Asian and Pacific Americans and their communities. . . . While thoroughly academic in its approaches, Asian American studies is also strongly committed to a focus on community issues and social problems. . . . [AAS] is part of an effort to change education in all its facets, with an emphasis on making it more equitable, inclusive and open to alternative perspectives. . . . Asian American scholars envision that their teaching and research will play a role in countering the cultural domination of the existing Euro-American knowledge base taught in American colleges; they hope to produce the kind of scholarship and students capable of resolving injustices and creating a more equitable society. (pp. 56–58)

Creating an environment for consciousness raising among students, to reimagine the power that comes from seeing one’s position in a social and political system that upholds white supremacy, calls for embracing marginality as “a site of radical possibility, a space of resistance. . . . It offers to one the possibility of radical perspective from which to see and create, to imagine alternatives, new worlds” (hooks, 1989, p. 20). In a social, economic, and political system created to maintain people of color as subordinate, AAS offers students opportunities to build upon previous generations’ knowledge and accomplishments by learning who they are, what positions they occupy in America’s racialized society, and how to exercise power mindfully. In this way, social change occurs when next-generation leaders and activists interpret the field’s mission for themselves and embrace community-centered values to work collectively to address current issues and improve our communities for their own and future generations. Our article provides insight into this process of individual awakening and transformation as a way to effect social change to achieve social justice.

Scholarly Frameworks

Two additional theories provide lenses to signify and interpret our research: critical race theory (CRT) and intersectionality. According to Solórzano and Yosso (2001), CRT in education strives to “develop a theoretical, conceptual, methodological, and pedagogical strategy that accounts for the role of race and racism in . . . education and works toward the elimination of racism as part of a larger goal of eliminating other forms of subordination, such as gender, class, and sexual orientation” (p. 472). Five themes characterize CRT:

- the centrality of race and racism and their intersectionality with other forms of subordination

- the challenge to dominant ideology

- the commitment to social justice

- the centrality of experiential knowledge

- the transdisciplinary perspective (Solórzano & Yosso, 2001, pp. 472–473)

Employing CRT, we choose to share our personal narratives as experiential knowledge to expand definitions of community-engaged scholarship and offer insights into the impact of service learning pedagogy intentionally created to address power and social change (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002). Our purposeful presentation of counter-stories challenges dominant assumptions about approaching service learning consciously, particularly regarding how we view “community” and exercise power.

Collins and Bilge (2016) describe the second analytic approach, intersectionality, as the following:

a way of understanding and analyzing the complexity in the world, in people, and in human experiences. The events and conditions of social and political life and the self can seldom be understood as shaped by one factor. They are generally shaped by many factors in diverse and mutually influencing ways. When it comes to social inequality, peoples’ lives and the organization of power in a given society are better understood as being shaped not by a single axis of social division, be it race or gender or class, but by many axes that work together and influence each other. Intersectionality as an analytic tool gives people better access to the complexity of the world and of themselves. (p. 2)

They identify six core themes that often accompany intersectional analyses in various forms: (a) social inequality, (b) power, (c) relationality, (d) social context, (e) complexity, and (f) social justice (Collins & Bilge, 2016, pp. 25–30). We found intersectionality a useful theory with which to express our struggle to describe and explain our data’s nuance and fluidity. Intersectionality accounts for the complexity of our individual lives and our communities’ stories. Inherent in our positionality as people of AAPI heritage and people of color in American society is social inequality. Because we as faculty and now alumni are privileged with university resources and education that come with real yet unspoken power, we address the significance of our research contributions by purposefully employing CRT and intersectionality to present our findings.

ASAM 230’s Context and Creation

Understanding the regional and disciplinary contexts for ASAM 230’s creation illuminates our study’s contribution to the field of community-engaged scholarship. CSUF, a public comprehensive university committed to educating its regional students with a global perspective (CSUF, 2020a), is situated in Orange County, home to the third highest population of AAPI residents in the nation (Campbell & Bharath, 2011) and the largest number of people of Vietnamese descent outside of Vietnam. Among the 23 California State University campuses, CSUF is one of the largest, with 41,408 students enrolled in fall 2020 (CSUF, 2020b). More than 75% identify as students of color. Mostly a “commuter” campus, CSUF houses approximately 5% of its students in residence life. As of fall 2020, CSUF’s students consist of 20.7% self-identified Asian students and 0.2% Native Hawaiian or Other Pacific Islander students. Of these, only 47% have parents who graduated from college (CSUF, 2020b). With these demographics, CSUF and ASAM have prioritized offering students educational opportunities not only to earn degrees and gain employment but also to become engaged citizens and leaders who effect culturally responsive, community-minded policies and practices in our region, state, and nation.

As indicated in the introduction, our research team originally came together as professor and undergraduate students through ASAM 230. When alumni co-authors took ASAM 230 from 2011 to 2016, they served primarily with OCAPICA’s after-school youth programs mentoring high school students of mostly Southeast Asian, Pacific Islander, Latinx, and African American heritage in our local communities. More than half of the high school youth served through OCAPICA’s youth programs have parents who had neither attended nor completed college. At that time, OCAPICA’s goals included improving health and increasing access to higher education among its surrounding communities.

Through this CSUF-OCAPICA partnership, ASAM 230 provides students the opportunity to enact a vision originating in the Asian American Movement of the 1960s and 1970s (Yee, 2020). ASAM 230 students learn that the movement gave rise to both the academic discipline of Asian American studies and direct-service, advocacy-oriented CBOs (Wei, 1993). Both were intended to collaborate to serve the community (Wei, 1993) in order to achieve the Asian American Movement’s goal of “revolutionary structural change for liberation and social justice in education and society” (Yee, 2020, p. 43). ASAM 230’s purposeful design embeds students in the process of serving with our communities via mutually beneficial community-university partnerships (Yee & Cheri, 2018–2019), as intended by AAS founders (Hune, 1989; Ishizuka, 2016; Liu et al., 2008; Louie & Omatsu, 2014; Wei, 1993; Zhou & Ocampo, 2016). OCAPICA partners affirmed this vision as they taught our college students how to mentor high school students with a respectful, reciprocal asset-based approach. ASAM 230 students learned to conceive of their service-learner roles as both university partners and community members—rather than as “college outsiders/experts” coming “into” and “fixing” community. The high school mentees benefited from the mentors’ experience as college students, and the ASAM 230 mentors gained insight and practical knowledge by supporting the high schoolers’ college application process and socialization. As a result, ASAM 230 students learned AAS’s definition of “community” firsthand by simultaneously uplifting all community members and viewing themselves as part of an intergenerational cycle of community building.

Who Are We?

Situating ourselves is a qualitative research practice that explains how our unique lenses influence our scholarly approach, analysis, and findings (Creswell, 2007). We write in first and third person and singular and plural voices to try to balance our team’s perspectives. Additionally, we articulate our names’ preferred phonetic pronunciations, as the anglicizing, changing, or indifferent mis-pronunciation of AAPI community members’ names is often a seemingly innocent yet disrespectful form of domination and diminishment.

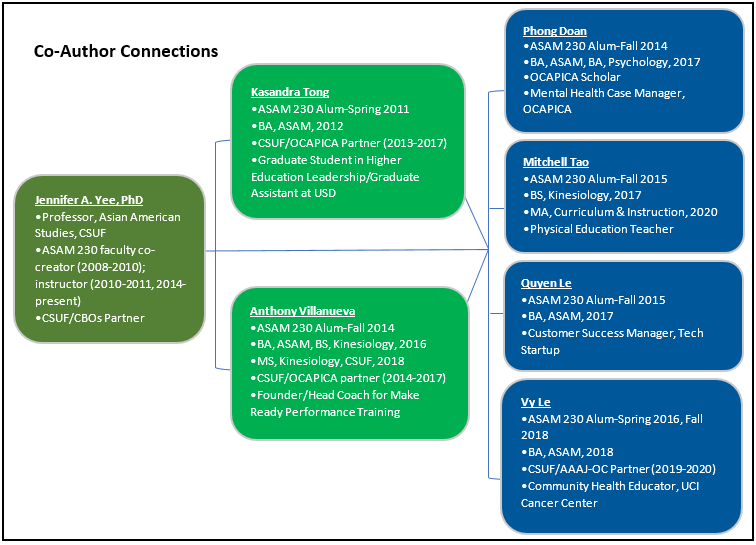

Figure 1 explains our relationships, including when we met through ASAM 230, our collaborations, and current occupations. ASAM 230 professor Jennifer A. Yee (Jen) taught all undergraduates during the indicated terms. Alumni Kasandra Tong (Kassie) and Anthony Villanueva graduated and served as OCAPICA community partners, where they created ASAM 230’s first formal 10-week service curriculum and co-taught the other four alumni, Phong Doan, Mitchell Tao, Quyen Le, and Vy Le, from fall 2014 through spring 2016. After graduating, Vy also served as community partner at Asian Americans Advancing Justice—Orange County (AAAJ-OC), designed AAAJ-OC’s service curriculum, and co-taught ASAM 230 students from spring 2019 through spring 2020.

In 2017, Jen invited alumni to design a pedagogical workshop to share ASAM 230 experiences at a national conference (Yee et al., 2017). We had so much fun that we embarked on a longitudinal collaborative autoethnography to understand ASAM 230’s impact. We presented preliminary findings at a 2019 conference (Yee et al., 2019) and culminate our study in this article.

With relationships built on trust, care, respect, honesty, and mutuality, we have sustained this project with weekend in-person and Zoom meetings as each student graduated and progressed to careers and graduate school. We proactively discussed shifting power dynamics from a hierarchy as former students, community partners, and service learning co-instructors to a collegial scholarly partnership as alumni, professionals, and mentors. We shared project responsibilities and openly decided co-authorship order by consensus.

Why Did We Teach/Take ASAM 230?

To understand our lenses as researchers, we convey our origins and reasons for teaching and taking ASAM 230. All of us originate from or identify with the immigrant and refugee communities of color served through ASAM 230. Of our seven team members, one is 1.5-generation (immigration status),[6] five are second-generation, and one is descended from multiple generations.

Jen, ASAM 230’s faculty creator, shared her family history:

As the youngest of seven children of immigrants born and raised in . . . southern China, I identify ethnically as Chinese American and politically as Asian American. I am second-generation, born and raised in a working-class family in Compton, a predominantly Black community, and Cerritos, California (Nicol & Yee, 2012). My dad grew up in Japanese-occupied China during World War II and was sent to the U.S. to earn money for his family. My mom, whose family had fled to the Philippines during World War II, came to Los Angeles on a college scholarship, where she met my dad when they both worked at a Chinese restaurant.

She described embracing social justice values through her K–12 Catholic education, solidified by her college education in the California State University system, where she affirmed her goal to serve “the public good with an explicit foundation of social justice values.”

ASAM alumna and community partner Kassie Tong shared a family history that embodies AAPI fluidity of migration and identity. After transferring to CSUF, she turned to Asian American studies because “it was the first time . . . [she] was able to make a personal connection” with the curriculum.

I am a Yonsei (fourth-generation) Japanese and second-generation Chinese American born and raised in Orange County, California, [older of two]. . . . My dad is the third oldest of eight [from] southern China. Because of the Communist Revolution he immigrated to the U.S. as a young child with his mother, my Nai Nai. . . . My mom is a Sansei (third-generation) Japanese American . . . raised in Los Angeles. Her paternal grandfather, my Hii-ojiisan (great-grandfather), came to the U.S. from Hiroshima to work. He returned to Hiroshima to marry and came back to start a family in California. My Ojiichan (grandpa) was born and raised in Los Angeles county. He was in high school when he and his family were forced into internment camps for three years during World War II. After the war he and his family went to Japan where he met and married my Obaachan (grandma) before moving back to Los Angeles. . . .

. . . I took ASAM 230 because the class description fascinated me. . . . I liked that this service-learning course would allow me to implement what I was being taught in class and would give me the opportunity to work with the community.

ASAM alumnus and community partner Anthony Villanueva (professionally pronounced VEE-ya-new-EH-va; family pronounced VIL-ya-new-EH-va) wrote of his childhood health challenges as motivation to pursue his career:

I am a second-generation Filipino American born and raised in Orange County, California. My father and mother immigrated to the United States in 1988 where they would later raise three children—I was the middle child. At five years old I underwent open-heart surgery which changed . . . my life, as I would . . . grow up with an unhealthy relationship with physical activity and food. Overcoming bullying and low self-esteem, I was determined to pursue a career in coaching.

. . . While at CSUF, I coordinated programs that encouraged healthy lifestyles for youth populations through the Healthy Asian Pacific Islander Youth Empowerment Program (HAPIYEP) at OCAPICA, Reflective Educational Approach to Character and Health (REACH) program, and Lunchtime Exercise Activity Program (LEAP).

Because of my involvement in HAPIYEP, I [took] ASAM 230 to learn more about service-learning and [mentor] the ASAM 230 students . . .

Alumnus Phong Doan (first name pronounced Fawmg; last name pronounced doh-AHN) has an incredible story of being mentored by ASAM 230 students as a high school student, then becoming an ASAM 230 student in college and mentoring others.

I am a second-generation Vietnamese American born in . . . New Hampshire but [raised] in Orange County . . . specifically . . . Little Saigon, a heavily dense Vietnamese community. I am an only child . . . from a single-parent household. My mom was a boat person who went on a week-long voyage to seek refuge from the Vietnam War at a camp in Malaysia [in the] 1980s and eventually was sponsored by a Catholic church to immigrate to . . . America after [two] years. She was 2 out of 10 siblings that escaped Vietnam. . . . My mother is the first person in our family to complete a college education in Accounting from CSUF. . . .

. . . I took ASAM 230 because I had never taken a service-learning class and an ASAM colleague highly recommended it to me. Also, I found out that the community [partner] that was collaborating with ASAM 230 was OCAPICA so I immediately was attracted to participating since I was once a former scholar/mentee of theirs in high school and decided this was an opportune moment to give back to the community that once fostered my own growth.

Alumnus Mitchell Tao (last name pronounced Tow, rhymes with now) examined his identity through ASAM courses.

I am a second-generation Asian American born and raised in Orange County . . . middle child of two sisters. My dad was the youngest . . . of 6 and immigrated [to the U.S.] from Cambodia as a teenager. My mom is the 6th out of ten and immigrated [to the U.S.] from Cambodia as a teenager. Both . . . completed high school and worked at a donut shop for 30+ years to support my siblings and me through college. My dad baked donuts in the evenings and worked another job during the day. My mom managed the store front and raised my family. . . . My grandparents were in all parts of China and they immigrated to Cambodia and stayed in a refugee camp. . . . although my parents feel a cultural tie to Cambodia they also acknowledge [their] Chinese roots. My grandparents made brave choices to give their family the best opportunity possible by moving to the United States.

. . . I took ASAM 230 . . . because I took a class with Professor Yee before and it was insightful learning about Asian American identity.

Alumna Quyen Le (pronounced Quinn and Leh) noted that while her previous ASAM classes had taught her conceptually about serving with community, ASAM 230 made this abstract ideal concrete and real.

I am a second-generation Vietnamese-American born and raised in Garden Grove [in] “Little Saigon,” and in Irvine, in Orange County, Southern California. Each city hosts large Asian-American populations, and I am extremely fortunate to have been raised in both. . . .

. . . Despite not knowing anything about the class, I chose to take ASAM 230 at the strong suggestion of some of my peers soon after declaring my major. The program exposed me to my privilege and sponsored my passion for community building. . . . Understanding my communities’ role in my identity has been the most rewarding experience of my life and has prepared me for a variety of experiences even outside of the academic field.

Alumna and former community partner Vy Le (pronounced Vee and Leh) described the relationship between taking ASAM 230 and developing her personal identity:

I was born in Saigon, Vietnam. My mother was a pre-school teacher and my father was a newspaper delivery man. When I was two . . . he left to the United States . . . to establish a better life for us. To pursue our own American Dream, my mother and I . . . immigrated to the United States in 2003 to be with my father. I was seven years old.

My family rented a small garage in Baldwin Park, California . . . our home for the first five years. We . . . moved to El Monte, a neighboring city that shaped most of my identity. Just like Baldwin Park, the communities at El Monte were mostly Latinx and Asian Americans, particularly Chinese and Vietnamese. Folks . . . were mostly low-income first-generation immigrants who owned donut shops, worked in sweatshops, and waited tables at restaurants. Similarly, my parents supported our family by waking up at the crack of dawn to deliver newspapers and bend their backs sewing garments. . . .

. . . I took ASAM 230 because I wanted to give back to my community. . . . I’d never heard of a class like ASAM 230 before and was really interested to know what [service learning] would be like. At that time I was also starting to come to terms with my identity as an Asian American and wanted to connect with my community.

Intentionally situating who we are in both service learning spaces and community-engaged scholarship highlights the richness of our stories as our community wealth (Yosso, 2005). Delgado Bernal (2002) contends that all students of color are holders and creators of knowledge, as their family “histories, experiences, cultures, and languages” offer strengths to respond to oppression (pp. 120–121). In this spirit, our team reflected on the relationship between their origins, the consciousness that emerged during and subsequent to taking ASAM 230, their present lives, and their future goals (see “Findings”).

Methodology

Collaborative Autoethnography

We conducted a collaborative autoethnography (CAE), a “qualitative research method in which researchers work in community to collect their autobiographical materials and to analyze and interpret their data collectively to gain a meaningful understanding of sociocultural phenomena reflected in their autobiographical data” (Chang et al., 2013, pp. 23–24). Our project followed the “iterative process of collaborative autoethnography”: (a) preliminary data collection, (b) subsequent data collection, (c) data analysis and interpretation, and (d) report writing (Chang et al., 2013, p. 24; Holman Jones et al., 2013).

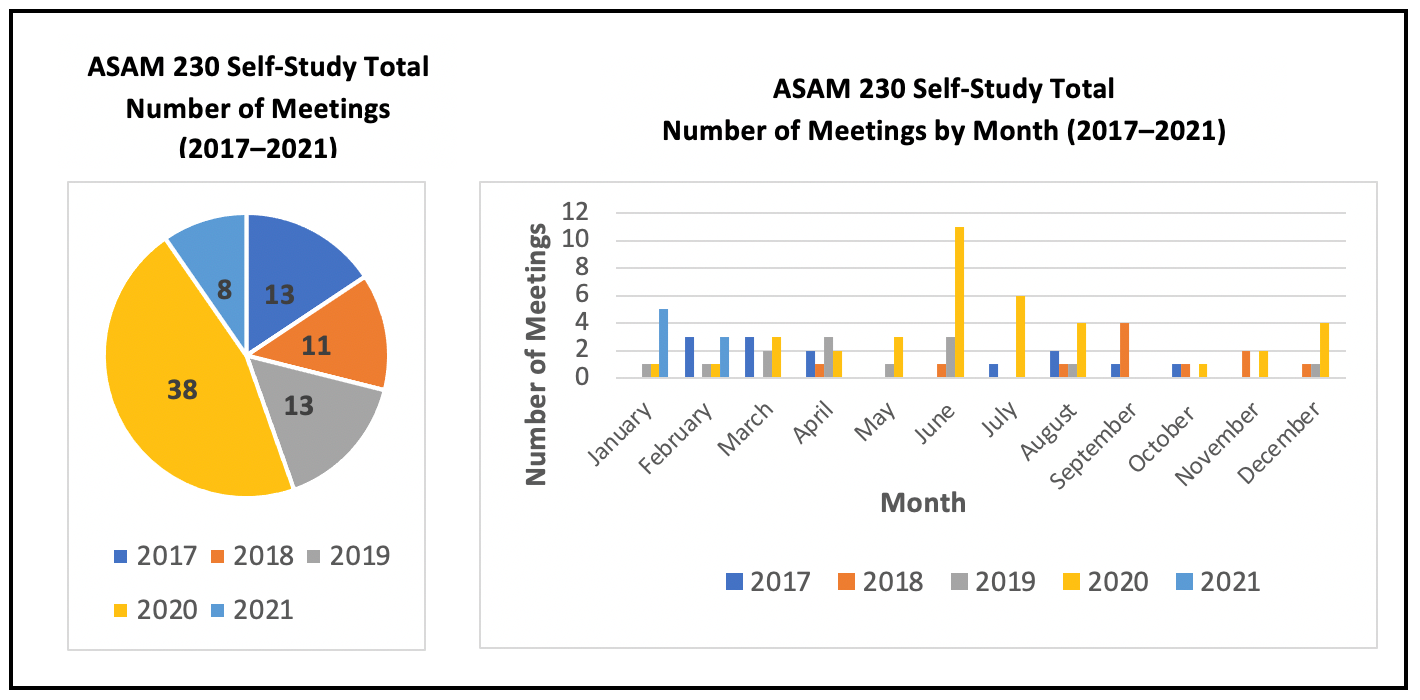

From 2017 to 2021, we shared team responsibilities, met at least 80 times in person and via Zoom, collected and analyzed data, and generated theory together (see Appendix for methodological details, timeline, and protocols). Our data set includes reflections from 2017 to 2020, the 2017 Association for Asian American Studies (AAAS) presentation, the 2019 Western Association of Schools and Colleges (WASC) Senior Colleges and Universities Commission (WSCUC) Academic Resource Conference (ARC) presentation transcript, and our 2017 to 2020 meeting notes.

After reviewing 2017 and 2018 data in summer 2018, alumni articulated and defined preliminary themes; then each alumnus individually coded all data by hand. Together we chunked data by organizing alumni quotes on posters into emergent themes (i.e., leadership, mentorship, activism, reflection, class and field curricular development, culture, service learning, radical care, and community). Then alumni organized the major themes and narratives into an Excel database in 2019. As alumni researchers analyzed our findings, Jen asked probing questions (e.g., What do you mean? How do you know this? Do these concepts and themes relate to your development, and if so, how?). Centering alumni interpretations about micro-level details led to our collective inductive reasoning. After discussing alumni analyses, Jen subsequently identified and named our emerging phenomena in qualitative methodology terms. She reflected her understanding back to the team in clearer language for verification. In turn, the team clarified and drew diagrams to ensure Jen grasped their analyses, which she translated into writing.

Our rich discussions moved alumni to challenge our initial research question; that is, how could alumni explain the course’s assumed, one-way impact on their development without understanding how Jen designed the class? Their insistent questioning led our team in two directions: (a) Jen answered their questions in an article on how ASAM 230 addresses social justice as a critical service learning course (Yee, 2020), and (b) we sketched a circular process depicting ASAM 230’s much broader impact on alumni’s lives, emerging as ASAM 230’s theory for social change (Figure 2). Integrating CAE and a grounded theory analytical approach of being open to what emerged from our data (Glaser & Strauss, 1967) helped us to represent our theory generation non-traditionally. Chang et al. (2013) “argue that CAE as an emerging research practice should not be limited to a particular approach or style of representation as long as it holds true to salient aspects of methodological rigor” (p. 25).

As alumni availability decreased due to post-college job searches, life changes, and graduate school, co-authoring shifted to Jen, whose methodological expertise and research experience enabled her to draft and finalize the article. During the writing phase, the team met biweekly to refine ongoing analyses, content, and language. Finalizing the article has followed the same process, with the team discussing reviewers’ and editorial feedback and clarifying analyses together. Jen rewrote with the team’s direction, consent, and final approval. Our article is truly a product of collective thinking and shared scholarly work.

Findings

Our team learned that ASAM 230 sparked a consciousness and commitment to social justice that had immediate and long-term reverberations in our alumni’s lives. To explain our findings’ significance, we generated theory explaining how ASAM 230 influences alumni’s professional pathways and contributes to social change (Figure 2). Our theoretical model provides a visual organizing framework for our narrative analyses.

Our ASAM 230 theory for social change offers a simplified linear explanation for how ASAM 230 impacted alumni’s development as leaders and activists. It shows how ASAM 230 emerged from (1) a historical context of a racialized America and the Asian American Movement that (2) centers social justice and serving community as foundational values for empowerment and survival. This movement envisioned (3) CBOs and AAS university programs collaborating to educate and create knowledge and consciousness to serve community. Mentored by both academic and community activists, Jen (2001) conducted dissertation research on AAPI activists and (4) developed her own intersectional AAPI feminist identity and epistemology manifested through her teaching and scholarship. She co-created (5) ASAM 230 with OCAPICA partners, who intentionally designed (6) both the class and service curriculum so that students would viscerally and intellectually understand the meaning and values of AAS’s mission to “serve community.” ASAM 230 students (7) reflected on their life purpose through structured reflective writing and activities and integrated community service learning from the field. Upon graduating, (8) three ASAM 230 alumni returned to their CBOs as partners to teach and mentor additional ASAM 230 students. All alumni are currently pursuing (9) chosen professional pathways where they now exercise the community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful power that they experienced in ASAM 230 with (10) colleagues and clients/students. In so doing, they aspire to change (11) their organizational cultures and, combined, (12) lead to social change. Our team created this model to convey how ASAM 230 and its impact on our alumni’s development not only emerged from but also contribute to a larger social justice movement to achieve social change.

The next section highlights alumni standpoints and narratives from which we inferred ASAM 230’s theory for social change. The analytical frame of intersectionality supports our reporting of “both-and” interrelated findings rather than limiting ourselves to “either-or” binary thinking (Collins & Bilge, 2016, p. 27).

Professor’s Identity and Pedagogy

To understand ASAM 230’s impact on us, we alumni asked, How and why did Jen create the class? Through our probing, we found that Jen’s AAPI feminist pedagogy (i.e., her approach and practice of teaching) centered on expressing the value of “community” through radical care and mindful power. Jen reported manifesting her intersectional AAPI feminist identity, values, and epistemology when partnering with OCAPICA to design ASAM 230’s transformative curriculum (Nicol & Yee, 2012; Yee, 2009, 2020; Yee & Cheri, 2018–2019). She recalled that during her master’s and doctoral programs she engaged in research and community programs with university and community activists who inspired her intersectional understanding of “community.” She created ASAM 230 for the following reason:

because I want students to learn and understand viscerally how and why “community” is the heart of Asian American Studies, and to explore who they are and what matters to them through the lens of a field of study that was created and is continually re-created by people of color . . . the course is part of Asian American Studies’ social justice project to foster social change by transforming higher education from a system that upholds and replicates a racialized, gendered hierarchy to that which creates knowledge about and provides equitable access to communities of color to share power and engage fully in American society. (2019 Reflection)

Jen’s insight helped us to make sense of what we experienced in the ASAM 230 classroom and through our service. That is, instead of designing a space in higher education that maintains existing hierarchical structures and the status quo, she and OCAPICA partners intentionally sought to empower ASAM 230 students to learn about and experience personal and community transformation. The course’s reflective assignments fostered our articulation of who we are, how we see ourselves in relation to community, what matters to us and why, and our chosen life paths (Yee, 2020). Our team found that the combination of the course pedagogy, lessons, assignments, service, and explicit values raised our consciousness and influenced our alumni’s development as leaders and activists committed to social justice.

Emerging Consciousness and Sense of Self and Community

Our data reveal that several curricular elements stimulated our (alumni’s) evolving consciousness and clarified our sense of selves and potential to effect positive change in our communities. They are (a) clear social skill building on compassion, non-verbal communication, and kindness to prepare students to interact with community members; (b) reflective writing and the final “What Matters to Me and Why?” paper; and (c) the structured community service learning experience.

Social skill building for lifelong learning. Intentionally creating a humanistic environment that models respect, compassion, and support is critical to preparing students to engage with community. Through ASAM 230, Quyen learned what’s possible in education:

We study about what an interdisciplinary field looks like all the time in ASAM, but to see it in action [in ASAM 230] is very cool, and very reassuring. A lot of people—scholars, teachers—told me how lucky I was to be in CSUF’s Asian American studies program this weekend [at the AAAS conference], and I know I am now. We are so fortunate to be in such a supportive, thriving, enthusiastic program. . . .

. . . given the way the academic system is set up, I understand how rare it really is to have a space in school where I can be myself, where I can be human (instead of just another social capital creator). I didn’t even realize how little care I have received from the education system until I joined ASAM. I didn’t even realize that this is how education should be like, and how tragic it is to be a part of a system that cares so little about its students. (2017 Reflection)

Anthony highlighted the lifelong lesson on non-verbal communication and body language:

One of the biggest things that I still use today—it’s almost like breathing . . . Jen taught us an acronym, SOFTEN . . . Smile, Open posture, Forward lean, Touch, Eye contact and Nodding.

So, using SOFTEN, we were able to connect to our [high school students] way better. . . . Also I use that outside of working with kids. I was a bouncer at one point in my life. I’ve never been in a fight . . . as a bouncer for two years and I never threw a punch because I used to SOFTEN with all the patrons of the bar: like, let’s go talk outside. I’m an instructor now and a coach . . . I connect . . . better with all my clients . . . just because I learned that acronym. (2019 ARC)

Quyen appreciated hearing the distinction about the expected classroom norm to be kind by listening intently and asserting one’s perspectives honestly and sincerely:

Jen always told us that there is a huge difference between being kind and being nice, and that changed my life. I got to see firsthand how much more kindness means, and how underrated it is in the adult world. It is very easy to be nice; we do it automatically. Kindness requires effort: learned patience, sacrifice, vulnerability, but also a confidence and assertion that does not always come with being nice. Nice is polite. Kindness is necessary in order to achieve. I express my care through kindness above all else because it says that whatever I’m doing or whomever I’m talking to is worth the hard work it takes to be kind. (2017 Reflection)

As a result of learning ways to conduct themselves while serving with community, alumni felt empowered with consciousness and interpersonal skills that humanize their environments.

Reflective writing and “What Matters to Me and Why?” final paper. Research has found that reflection plays an integral role in community service learning (Astin et al., 2000). ASAM 230 students write service-related reflections and papers on who they are, their life timelines, their hopes and dreams, culminating in a final paper answering “What matters to me and why?” Our alumni recount how much the paper and its writing process impacted them.

Kassie shared that writing the paper stimulated her identity development:

We did a paper called What matters to me? and why? It was a very difficult paper to do because it was very self-reflective. Jen told us at the beginning, the paper was for us. . . . The deeper you go, the more you’re going to get out of it. And I have to say this was probably one of the most difficult papers I had to write as a college student.

It helped me to develop that a big part of my identity are my communities that I’m a part of, so it’s the communities that I was born into, the communities I’ve become a part of and ASAM 230 was one of those communities. I . . . developed my identity so much because I was able to develop not just individually, but also with other people. We kind of grew together because we were able to learn from each other. (2019 ARC)

Likewise, Phong mentioned how much the class and paper helped to discern his core values:

[T]he service learning class will always be a constant reminder that civic engagement and community service will be a necessity and embodiment of who I am. . . . Growing up, I already learned the virtues of compassion and community service but . . . this class showed me the . . . structure, . . . hard work and efforts . . . behind the scenes and on-site to create such a meaningful pipeline of mentorship and support for certain communities. ASAM 230 taught me more of myself profoundly (What Matters to Me & Why Paper—my hopes and dreams) in that class than all my years combined in my undergrad experience, to be honest. (2018 Reflection)

This class really sat me down and realigned what mattered to me . . . a really profound sense of cultural identity, desire of community, like what I can really do for my community as a person and what’s my capacity? . . . It really pushed me and solidified my desire to pursue a helping profession. (2019 ARC)

Anthony credited the final paper with integrating and crystallizing his purpose:

[The] What Matters to Me and Why [paper] was a bow and I was the arrow. This really sent me in such a quick direction because looking back on my path . . . I was at Cal State Fullerton for eight years. I went from this class to grad school and then here I am coaching [in] all these different positions. I would not have found this passion as fast if it wasn’t for that paper. Knowing who I am and what I want to do in giving back to the community and improving health out there. So it really was a bow and arrow, just straight shot. (2019 ARC)

Likewise, Vy reflected on ASAM 230’s role in solidifying her direction:

Reflecting back, ASAM 230 came at the right time in my life. The class molded my understanding of who I am, what is important to me, and how those aspects align with where I am now and who I am meant to be. The WMTMW paper gave me the space to reflect on the values, experiences, and people that were important to me. In a fast-paced academic environment, I was given a space to practice mindfulness and intentionality. For the first time since declaring ASAM as my major, I finally knew why.

ASAM 230 played a major role in helping me become the person I am today. I think as I am in different stages of my life, ASAM 230 will mean differently to me. For right now, as I experience confusion and stagnation in my academic/career path during post-grad transition, ASAM 230 reminds me of my core values. Whenever I feel like I need a sense of direction, the values, experiences, and people that I wrote about in the class keeps me grounded. At the end of the day, those things matter to me and as long as I keep them in heart, I always will have a direction. (2018 Reflection)

Our alumni narratives affirm the effectiveness of involving students in structured critical reflection throughout the term and particularly a culminating reflective paper that integrates the curricular content, service experience, and values exploration.

Intentional service/field curriculum. The long-term ASAM/CBO partnership afforded ASAM 230’s co-creators the privilege of continually improving the course (Yee, 2020; Yee & Cheri, 2018–2019). Each semester concluded with students, community partners, and faculty reflecting on what worked well and what could be better. Prior to 2015, students’ service experiences involved showing up on-site and assisting OCAPICA staff with their day’s activities. ASAM 230 students from fall 2014 recommended improving the class by providing a more structured community service learning curriculum. When Kassie and Anthony became ASAM 230’s OCAPICA community partners, they reflected on both their ASAM 230 student experience and OCAPICA’s Youth Program goals to envision a 10-week service curriculum engaging service-learners in a developmental service process. OCAPICA staff began to prepare and orient ASAM 230 students during Weeks 2 and 4 in the classroom. From Weeks 5 to 14, ASAM 230 students commenced on-site service as observers, increasing interactions with OCAPICA high school youth to become college student mentors. With OCAPICA staff guidance, ASAM 230 students became program leaders who planned and facilitated a full-day health-oriented curriculum—including a fun physical activity, a creative workshop, and a journal reflection prompt—for the high school students.

Mitchell and Vy benefited from the revamped developmentally progressive service curriculum. Mitchell described how the intentional service curriculum raised his awareness of community issues:

[It] opened my eyes to students’ needs to have a safe space where they can confide in their peers and learn from one another. Students come from different places. I learned how sleep—not only quality but quantity—is important. Seeing how students do not have food at home and that hunger affects the student’s stability in school. Students got to play, and have recess and learn to play with one another and learn that there is a different level of skill. I recall helping Anthony teaching students how to work out on strength, and learning squats and cleans. (2017 Reflection)

Vy also learned that attending to the details of building relationships makes a difference in the community:

Through ASAM 230, I became more involved with my community. I was able to build relationships with not only the organization but also with the students that I was serving. Through my participation with OCAPICA, I have learned how to make a difference in my community in small ways. Whether it was helping a student with their homework or chatting to a student about their day, I have learned that these small but meaningful actions make a huge difference. As a result, I continued building my relationship with the students at OCAPICA because I felt like my actions affect the community in a positive way. Additionally . . . I was able to be more intentional and aware of what I was learning through reflection. Through ASAM 230, I was able to utilize the act of reflection in the other aspects of my life. (2017 Reflection)

Pondering the impact of these elements on our growth and consciousness, we alumni realized that the process of engaging in the class sparked our consciousness about our identities, values, and sense of purpose.

Course Values

Jen modeled AAPI feminist values by teaching with community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful power (Yee, 2020; Yee & Cheri, 2018–2019). These values influenced (a) our understanding of how important a commitment to community is to our sense of selves, (b) how much the feeling and practice of radical care impacted us, and (c) how the transparency of having and using our power affects our leadership and activism.

Community and community-mindedness. The Asian American Movement’s concept of “community” refers to a value and belief instrumental to the overall AAPI community’s political empowerment and survival in the United States. In Asian American studies, we actualize this value as the practice of “community-mindedness,” which assumes that individuals are always in relationship with one another. Jen welcomes students warmly during the first week of class, as she establishes clear norms that convey the importance of communication, compassion, honesty, and mutual respect as foundations for building community. These norms translate into shared expectations for how faculty and students eventually engage with community partners and members. As Kassie observed:

[C]ommunity means relationships, that have to be built based on trust and mutual respect, not about coming in to save someone, you have the privilege of being accepted and part of this community—to trust you to collaborate to do work to benefit them. A lot of folks don’t know how to define community—you’re part of multiple communities—who you grew up with, you work with, you go to school with . . . at the end of the day, how do you show up for each of those spaces? (2020 Meeting)

Vy described “community-mindedness” as a way of thinking and being that balances individual needs with the collective good:

[Students] have to experience what it’s like to be in community in order to really understand and value what it means to be in community . . . that’s what ASAM 230 is about. We’re part of this community and we matter. We can make a difference. We’re in a space where our voices are amplified and encouraged, which allows us to bring that experience into other spaces too. . . . Feeling the care, feeling valued, those experiences lead us to really enjoy being in a space where you get to feel that again. . . . Community is putting yourself aside and thinking bigger, broader . . . about the whole, thinking about other people. (2020 Meeting)

Practicing community-mindedness has helped us alumni to embrace and manifest the value of community in our present lives. Community-mindedness is a way of connecting and supporting one another through shared histories, experiences, and oppressions and interacting through authentic, non-judgmental balanced relationships with one another. Distinct from how community-engaged learning and scholarship may define “community” as entities “outside” or beyond the university’s scope (i.e., not students), we perceive community as intersecting with the university (e.g., we are community members and students who move fluidly through the university and return home to live, socialize, and work). In other words, we write about ourselves as both “students” and “community” in this article.

Radical care. Jen consciously manifests the value of “radical care” to foster humanity, mutual respect, humor, safety, kindness, and compassion in the classroom. “Radical” reflects non-conforming, out-of-the-box thinking, and radical care is a way of being that extends beyond conventional ideas about classroom interaction. Mitchell conveyed our composite definition:

[Radical care is] being intentional with each other, how we act, how we behave. When we’re showing this care, it’s not just about “how are you doing?” But “how are you really doing?” And we’re putting a lot of effort into making each other physically and emotionally ready to learn in a classroom setting. (2019 ARC)

Kassie observed radical care practices included sitting in a circle, checking in to understand people’s mindset, and assuming that everyone in the class, including the professor, learns from one another (2017 Reflection). We alumni observed how much this acknowledgment of our humanity impacted our learning and now intentionally lead with radical care to value people as people rather than as workers, producers, and consumers.

Mindful power. Employing power consciously requires acknowledging one’s position in hierarchical relationships between and among people and organizations. This critical perspective acknowledges structural oppressions such as racism, sexism, classism, able-ism, and privilege. Because power shifts with each context, one who does not feel powerful in one setting may either be perceived to have or actually possess power in another. Using one’s power to humanize our spaces emerged in our data, as Vy asserted:

So, Jen’s class influenced me in a way where it taught me not only to empathize with others, but to humanize other people and experiences. I think that is so important and that’s what I do in the work that I’m in right now. And that’s how I treat my friends, my coworkers, my partner, my parents, my family is to look at their experiences . . . really humanize them—not put them on a pedestal and look at their power and then judge them—but just really look at them as just humans. . . . Jen just does that with all of us and everyone she’s involved with and I think it’s really powerful. (2019 ARC)

In this section we have articulated ASAM 230’s pedagogical approach and explained how social skill building, reflective writing, and service animated our awareness of self-purpose and community. Upon identifying the course’s underlying values of community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful power, we now understand more clearly how ASAM 230 has impacted our evolution as leaders and activists.

ASAM 230 Inspires Leadership, Activism, and Professional Aspirations

Our most compelling evidence of ASAM 230’s impact lies in connecting the spark of our consciousness to our post-graduation leadership and professional pathways. Three of us alumni have served as community partners, designed service learning curricula, and co-taught subsequent ASAM 230 service-learners. Now progressing in our careers, we alumni share examples of how we embraced and carry forward the values of community, radical care, and mindful power.

After becoming a program coordinator at OCAPICA, Kassie practiced the community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful power she learned in ASAM 230:

Creating a positive environment invites for connection building and sets the tone of everything that will happen moving forward. When working with my students I would check-in to take the pulse of how they’re feeling at that exact moment to get an understanding of how their mindset might be. This is important information as you move into discussions because you have a better understanding of where they’re coming from. I strive to create an environment of mutual respect and that encourages human connection . . . you need to actively engage with those in front of you, by showing that you’re genuinely interested and authentic because people will tend to reciprocate in kind . . . being present and willing to listen . . . can be a very powerful form of care. (2018 Reflection)

[S]omething we learned from Jen is that sharing your power doesn’t diminish the power that you have. We’ve learned that working as a collective we can do amazing impactful things probably bigger than what we thought we could do as an individual. Just being able to help empower our students to kind of take those steps by themselves and showing them how to start and letting them go. (2019 ARC)

Kassie has taken this knowledge into her current role:

[As] a graduate student in a Higher Education Leadership program at a predominantly white private Catholic institution where I am also a graduate assistant working with the Native American community . . . I aspire to . . . a career [to create] spaces for students to build on their foundation, create supportive networks in and out of college and explore who they are and want to be. (2020 Reflection)

When Anthony worked as a high school coach, he exercised his power as a leader mindfully to model community-mindedness:

I’m surrounded by a lot of high school boys. When I coach them . . . one thing . . . I do as a leader is I don’t accept misogynistic behavior in my gym, which is very common place to see that stuff. I have no problem calling them out and . . . using that as a teaching moment, “By the way, that’s not right. You shouldn’t be talking about that.” And they get caught off guard thinking . . . “oh, but coach, why don’t you do it with us? and like, be cool.” [I respond] “No, we don’t do that.” . . . hopefully that starts instilling better lessons for them to take forward because I have that proper lens coming from this [Asian American studies] background. (2019 ARC)

Anthony’s philosophy as a business owner continues to embrace community:

Since then, I have been privately coaching clients around the world. My passion for teaching people how to celebrate life through fitness and nutrition is fueled by wanting to be the coach I never had. Coaching is my way to give back to the community that raised me to be the person I am. (2020 Reflection)

Phong’s transformative experience conveys the full impact of the community-university partnership that created ASAM 230. As a high school student, he participated in OCAPICA’s after-school program in which he was mentored by ASAM 230 students. Upon enrolling at CSUF, he became an ASAM 230 service-learner and mentor.

Back . . . when I was taking ASAM 230, it had given me the unexpected opportunity to give back FULL CIRCLE to the community. . . . ASAM 230 [gave] me the safe and warm space to grow! My experience was a great & fundamental life lesson in mentorship. Because of ASAM 230, I was able to become a role model—a mentor. I was always the mentee in the receiving end. I never had the opportunity to coach someone and share my own wisdom and guidance. I felt extremely empowered as a leader. . . .

The class and experience gave me the confidence and courage to feel competent in my own abilities [so that I] could finally make a difference for others. I felt like my mentoring my students in low income & underprivileged communities was in itself a form of activism for change in bettering the lives of others. I was definitely closer to my community and felt I was finally making an impact. (2018 Reflection)

After graduating, Phong’s return to OCAPICA shows that ASAM 230 can build capacity for community leadership:

I am . . . a Mental Health Rehab Case Manager at [OCAPICA] where I provide intensive and wraparound rehab services to the AAPI community. . . . I aspire to provide aid and healing within my community and hopefully be a person of guidance and light for those that lack that support system in their lives. (2020 Reflection)

As a physical education teacher, Mitchell has purposefully translated his experience of social skill building, community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful power into similar curricular opportunities for his students:

ASAM 230 impacted my development as a leader by empowering me to become an educator. Short-term I see myself teaching physical education and using it as a platform to develop soft skills. Students in physical education have a great opportunity to learn how to be kind to one another. These skills can transfer outside of the classroom. I highlight cooperation activities, team building and less competition. I want students to know how to listen to one another. I think in this leadership role I’m giving students this vision and empowering them to empower one another. (2018 Reflection)

I have 90 students at a time, kindergarteners, first graders, second graders . . . I’ve developed . . . a check-in system with my students: a green smiling face if we’re good, a yellow is I’m okay . . . and red, I’m not feeling good, I’m sick or something happened to me outside, I’m hungry or tired. It gives me a chance to check in with those students who are red or okay and get to really know what’s going on and how to make their P.E. experience a lot better. . . .

My classes have activities that empower students’ choice. . . . For example, one activity inspired by Caine’s Arcade empowers 6th-grade students to create P.E.-based arcade games to serve their little buddies (kindergarten). It has shown the students they can create and make a positive impact in other people’s lives. (2019 ARC)

As a physical education teacher, Mitchell articulated his goals:

[I] aim to develop the next generation of students to love movement, and love to make deep connections with one another. I work at both a Title I school[7] and a school with affluent resources. I believe in giving back to the community around you. I want to instill these values in my students in meaningful and impactful ways. (2020 Reflection)

Quyen attested to ASAM 230’s combination of care and empowerment as inspiring her self-confidence as a leader:

Every time I think about leadership, I think about ASAM 230. And I never thought I’d ever be anyone who thinks or practices leadership regularly, but I do because of this class. This class taught me how to value myself as a leader and realize that I have a lot to offer. I am terrified of leading, so I never thought it was worthwhile to put myself in positions to do so. However, this class combined with the lens it gave the life events that followed helped me recognize that the challenge is worth conquering the fear. ASAM 230 is a sweet combination of self-worth + leadership development + love (of course). I needed it to realize how connected everything in my life was. (2018 Reflection)

Quyen’s development as a leader also involves activism. She continues to stretch herself professionally:

I think I’m an activist and a leader. . . . leadership/activism really means going against the status quo in micro and macro way[s], macro—joining organizations, elevating our voices, protesting. All of those things lead to dismantling all the things you described in instilling social justice. Activism is the practice of dismantling systemic oppression that undervalues people of color, especially Black and indigenous people, women, and LGBTQ/trans, and more. (2020 meeting)

Since graduating . . . I’ve been a healthcare administrator in both the pharmacy and dental fields before transitioning into a financial tech startup in San Francisco. I love how limitless my education makes me feel, and how many hats it’s allowed me to wear in my career path. Though I am excited to explore some more, I ultimately intend to return to ethnic studies education and eventually get my Master’s and PhD. (2020 Reflection)

Vy also connected the empowerment and care she experienced in ASAM 230 to her professional career:

[H]ow I experience care in ASAM 230 . . . Jen has this way of really telling us that it’s a two-way street in terms of learning and that she understands her power as a professor but she didn’t use it in a negative way. And she always made sure that . . . she’s learning from us too and we’re learning from her. Now I take that into my work . . . in immigration. Working with community in such a delicate way really taught me to realize that I’m not in the community to really tell them that I know this and that they need to do this. But I’m in the community in a position to learn from them as well and that’s something I will always take with me. (2019 ARC)

During my undergraduate years, I found Asian American studies and developed a deep passion for social justice. . . . I discovered and embraced my intersecting identities as a woman of color, low-income, and first-generation college student. It was then I knew I wanted to pursue a career in public service. Currently, I work in immigration law as a community advocate at AAAJ-Orange County, a legal and civil rights non-profit organization. (2020 Reflection)

Our findings reveal that the combination of ASAM 230’s pedagogical origins, curricular elements, and values have influenced our (alumni’s) identities and professional lives. While ASAM 230 was not the only class and Jen was not the only professor to impact us, we have learned that ASAM 230 sparked our commitment to enacting Asian American studies’ social justice values of community-mindedness, radical care, and mindful power and thus inspired our commitment to social change.

Discussion

Our study advances community-engaged scholarship by (a) generating a theory for social change rooted in evidence from an ethnic studies service learning course, (b) centering AAPI community and student voices who are historically marginalized in higher education research, and (c) challenging assumptions about the constructs of “community” and “students” in the scholarship of service learning and community engagement.

Theory for Social Change

We found that a direct link exists between an intentionally designed critical service learning course and long-term student and community commitments to effect social change for social justice. This causal assertion stems from the unique nature of our longitudinal collaborative autoethnography, through which we verified short- and long-term outcomes with our researchers. Our team illustrated the visual model (see Figure 2) to convey the alumni’s self-perceived impact of ASAM 230 on their growth and development. Finding that ASAM 230 served as a “spark” for their consciousness raising has tremendous implications for how university and community partners intentionally design civic education, service learning, and leadership development programs.

Centering AAPI Student and Community Voices

A persistent critique of community-engaged scholarship points to the absence of research centering community, student, and Black, Indigenous, and People of Color (BIPOC) perspectives. Our study directly addresses this critique, especially the dearth of AAPI voices, which are often overlooked or made invisible in higher education research (Osajima, 1995; Poon & Hune, 2009). Conducting our study with both Asian American studies and critical race theory lenses, we proactively centralized our experiential knowledge as AAPIs to counter structural racism in higher education research and by implication call for more research conducted in solidarity by, on, and with BIPOC communities, particularly scholarship on Asian and Pacific Islander and Desi Americans. In addition, one of the challenges of conducting research with students and community members as co-authors is the time commitment and variance in scholarly training. Our study’s implications for future research attest to the significance of committing time and resources, sharing scholarly power, continually clarifying students’ and community partners’ meanings and analyses, and obtaining consent.

Challenging Assumptions about “Community” and “Student” Constructs

Our study’s contribution lies in challenging assumptions about what “community” means, and, by extension, questioning the foundational language upon which community-engaged scholarship is built. Our team’s fluid conceptualization and interchangeable use of the terms “community” and “students” spotlights the importance of centralizing historically marginalized standpoints and meanings. Upon receiving initial editorial feedback following peer review, we were asked to consider making clearer distinctions between the impact on students and community, with the assumption that the two are different. This question opened a very animated discussion among our alumni, who argued that they are students situated in community and therefore our use of “student” is synonymous with “community.” They could not understand why the use of the word “community” would cause confusion, as they hold the “both-and” intersectional meaning of “community” in Asian American studies, not the “either-or” meaning distinguishing between “university” and “community” in existing community-engaged scholarship. The alumni advocated for recentering and claiming Asian American studies’ definition and value of “community” in our article. While groundbreaking bodies of knowledge (i.e., research on service learning and community engagement) at their inception rely on commonly held operational terms in order to communicate and disseminate research, the implication for contemporary community-engaged scholars is to challenge current scholarly assumptions and include previously excluded standpoints, language, and meanings.

Limitations and Recommendations

This study documents ASAM 230’s impact among six self-selected alumni. Future studies should examine and verify impact among a larger, more diverse ASAM 230 student population and further refine the theory for social change.

Centering social justice in community-engaged scholarship calls for creating scholarly teams that establish a research culture of care, honesty, transparency, and open communication. Establishing non-judgmental team norms that prioritize compassion, trust, and flexible expectations actively counters hierarchical power relations. We recommend sharing decision-making and openly discussing power dynamics, workload, and co-authorship.

To optimize community service learning’s potential to be transformative, educators and community partners should consider intentionally designing courses to achieve shared purposes, including social justice. Clearly articulated values appear to connect the professor and department more closely with CBO partners and, consequently, improve the students’ relationships with community members. In contrast, simply incorporating service activities as curricular elements without shared values and purpose may not deeply impact students nor community members.

Likewise, community service learning courses should include transparent discussions about unseen hierarchies of power and privilege so that service-learners may become aware of how their positions as college students may inadvertently alienate and oppress the communities they serve. Faculty and community partners should model teaching practices that share power and actively engage students as co-learners and community organizers.

Conclusion

As our nation continues to grapple with America’s deeply embedded institutional racism and the COVID-19 pandemic’s disproportionate impact on BIPOC communities, centralizing social justice in community-engaged teaching and scholarship is imperative. Our research, particularly our counter-stories as members of communities of color, prioritizes equity and access by both filling and highlighting unwarranted gaps in community-engaged scholarship. Embarking on our project in 2017, we could not have foreseen publishing four years later during a social and political reckoning critically in need of leaders and activists. We hope that our study of how “Civic Engagement Through AAPI Studies” sparked our commitment to social justice will inspire crucial new possibilities for transformative education.

Author Note

Jennifer A. Yee https://orcid.org/0000-0002-5335-1977

This article is based on data presented by Yee, Tong, Le, Le, Doan, Tao, & Villanueva (2017, 2019). The authors appreciate and acknowledge professional and financial support from California State University, Fullerton (Department of Asian American Studies, Center for Internships and Community Engagement/CICE, College of Humanities & Social Sciences), community partners (Orange County Asian and Pacific Islander Community Alliance, Korean Resource Center, The Cambodian Family, Asian Americans Advancing Justice—Orange County, Ahri Center), and grantors (CSUF/CICE Call to Service–Move to Action grants, Southern California Edison, CSUF Faculty Enhancement and Instructional Development grants, CSUF Junior/Senior Intramural grant). We warmly thank our families, partners, and colleagues for their unwavering encouragement.

Correspondence concerning this article should be addressed to Jennifer A. Yee, Department of Asian American Studies, California State University, Fullerton, 800 N. State College Blvd., H-314, Fullerton, CA 92831. Email: [email protected].

References

- Astin, A. W., Vogelgesang, L. J., Ikeda, E. K., & Yee, J. A. (2000). How service learning affects students. Higher Education Research Institute, University of California, Los Angeles. https://heri.ucla.edu/PDFs/HSLAS/HSLAS.PDF.

- Butin, D. W. (2010). Service-learning in theory and practice: The future of community engagement in higher education. Palgrave Macmillan.

- California State University, Fullerton. (2020a). Campus catalog: Mission and goals. https://catalog.fullerton.edu/content.php?catoid=17&navoid=2043#mission-and-goals.

- California State University, Fullerton. (2020b). Student demographics. Division of Academic Affairs, Office of Assessment and Institutional Effectiveness. http://www.fullerton.edu/data/institutionalresearch/student/demographics/index.php.

- Campbell, R., & Bharath, D. (2011, May 12). O.C. has third highest Asian population in U.S. The Orange County Register. https://www.ocregister.com/2011/05/12/oc-has-third-highest-asian-population-in-us/.

- Chan, S., & Wang, L. (1991). Racism and the model minority: Asian-Americans in higher education. In P. G. Altbach & K. Lomotey (Eds.), The racial crisis in American higher education (pp. 43–68). State University of New York Press.

- Chang, H., Ngunjiri, F. W., & Hernandez, K.-A. C. (2013). Collaborative autoethnography. Left Coast Press.

- Collins, P. H., & Bilge, S. (2016). Intersectionality. Polity Press.

- Creswell, J. W. (2007). Qualitative inquiry & research design: Choosing among five approaches (2nd ed.). Sage Publications.

- Declaration of independence. (1776). National Archives. https://www.archives.gov/founding-docs/declaration-transcript.

- Delgado Bernal, D. (2002). Critical race theory, Latino critical theory, and critical raced-gendered epistemologies: Recognizing students of color as holders and creators of knowledge. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 105–126. https://doi.org/10.1177/107780040200800107.

- Glaser, B., & Strauss, A. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Sociology Press.

- Holman Jones, S., Adams, T. E., & Ellis, C. (Eds.). (2013). Handbook of autoethnography. Left Coast Press.

- hooks, b. (1989). Choosing the margin as a space of radical openness. Framework: The Journal of Cinema and Media, 36, 15–23. http://www.jstor.org/stable/44111660.

- hooks, b. (2015). Talking back: Thinking feminist, thinking black. Routledge.

- Hune, S. (1989). Opening the American mind and body: The role of Asian American studies. Change, 21(6), 56–63. http://www.jstor.org/stable/40164762.

- Hune, S., & Chan, K. S. (1997). Special focus: Asian Pacific American demographic and educational trends. In D. Carter & R. Wilson (Eds.), Minorities in higher education, 15th annual status report (pp. 39–67, 103–107). American Council on Education.

- Ishizuka, K. L. (2016). Serve the people: Making Asian America in the long sixties. Verso.

- Liu, M., Geron, K., & Lai, T. (2008). The snake dance of Asian American activism: Community, vision, and power. Lexington Books.

- Louie, S., & Omatsu, G. K. (Eds.). (2014). Asian Americans: The movement and the moment. UCLA Asian American Studies Center Press.

- Mitchell, T. D. (2008). Traditional vs. critical service-learning: Engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 14(2), 50–65. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0014.205.