Developing Critical Consciousness: The Gains and Missed Opportunities for Latinx College Students in a Sport-Based Critical Service-Learning Course

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

Critical service-learning is a form of engaged pedagogy that supports development of students’ critical consciousness. However, critical service-learning continues to prioritize the development of white students, oftentimes at the expense of marginalized communities and minoritized college students. This study seeks to disrupt this approach by examining the attributes of Latinx critical consciousness present in 30 reflective writing entries written by six Latinx college students enrolled in a sport-based critical service-learning course for a semester. Findings demonstrate how the course aligned with students’ Latinx critical consciousness and how Latinx critical consciousness went beyond the focus of the course. Study findings have implications for service-learning practitioners and scholars who want to further consider how curriculum and practices in critical service-learning courses can center racially minoritized students’ critical consciousness.

Critical service-learning (CSL) is a form of engaged pedagogy connecting academic courses with community service experiences while having students examine and understand their social identities and positionalities, interrogate the systems that perpetuate inequality, and take actions toward addressing these inequalities (Mitchell, 2008; Rosenberger, 2000). Toward this goal, CSL instructors work to develop students’ critical consciousness as a learning outcome (Boyle-Baise, 2007) by having students “[c]ombine action and reflection in the classroom and community to examine both the historical precedents of the social problems addressed in their service placements and the impact of their personal action/inaction in maintaining and transforming those problems” (Mitchell, 2008, p. 54). Research on CSL has shown that students do deepen their understanding of structural problems (Barrera et al., 2017) and engage in actions for change (Johnson-Hunter & Risku, 2003; Kinefuchi, 2010; Rondini, 2015). Research, however, has also shown that like traditional service-learning, CSL can continue to reinforce structural injustices in both the classroom and community (Cahuas & Levkoe, 2017). Furthermore, when courses center racial justice, white students can use strategic discourses to reaffirm white privilege and reinforce domination over racially minoritized communities and people (Becker & Paul, 2015; Cann & McCloskey, 2017). Conversely, within the context of predominantly white service-learning courses, racially minoritized students can experience an overload in teaching their white peers about the people and communities they are serving (Mitchell & Donahue, 2009).

Related to our focus here, service-learning scholarship has generally ignored the experiences of Latinx students, instead focusing on Latinx communities as sites of service-learning that benefit white college students’ Spanish-speaking skills (e.g., Bollin, 2007; Caldwell, 2007) or general multicultural competence (Hale, 2008; Sperling, 2007; Vargas & Erba, 2017). Recent scholarship, however, has challenged this paradigm by highlighting transformative community-university projects that feature the wealth of knowledge embedded within Latinx communities (Castañeda & Krupczynski, 2017). Other research on the experiences of Latinx students in service-learning courses has shown that engaging them with Latinx communities increased their sense of belonging (Pak, 2018). When Latinx students compose a critical mass of service-learning course enrollees and the course content emphasizes Latinx consciousness development, students enhance their learning of their own identities, their knowledge of inequalities relevant to those identities, and their capacity to engage in social action relevant to their communities (Castillo-Montoya & Reyes, 2020; Delgado Bernal et al., 2009; Winans-Solis, 2014). Yet none of these studies are explicitly placed within the paradigm of CSL, despite the connections of equitable classroom practices, community empowerment, and social change.

It is here where we enter the conversation about CSL by focusing on the potential gains of CSL for Latinx students’ development of critical consciousness. We put forward that the ongoing emphasis of critical consciousness within CSL can be advanced by being more specific about the critical consciousness students are developing and how it may differ by students’ racial and ethnic identities. Other scholars have similarly noted the need for understanding this difference (e.g., Mitchell & Donahue, 2009), though the differences have been focused on a binary analysis: white racial consciousness and the racial consciousness of racially minoritized students. As such, in this study we aimed to address the following research questions: What aspects of Latinx critical consciousness do Latinx students reveal in their sport-based youth development course reflections? What aspects of Latinx students’ Latinx critical consciousness are aligned with the focus of the course? What aspects of Latinx students’ Latinx critical consciousness emerge that extend beyond the focus of course content? A focus on Latinx students can provide insight into how this student population might develop critical consciousness within predominantly white academic spaces serving minoritized communities.

Latinx Critical Consciousness: The Study’s Conceptual Framework

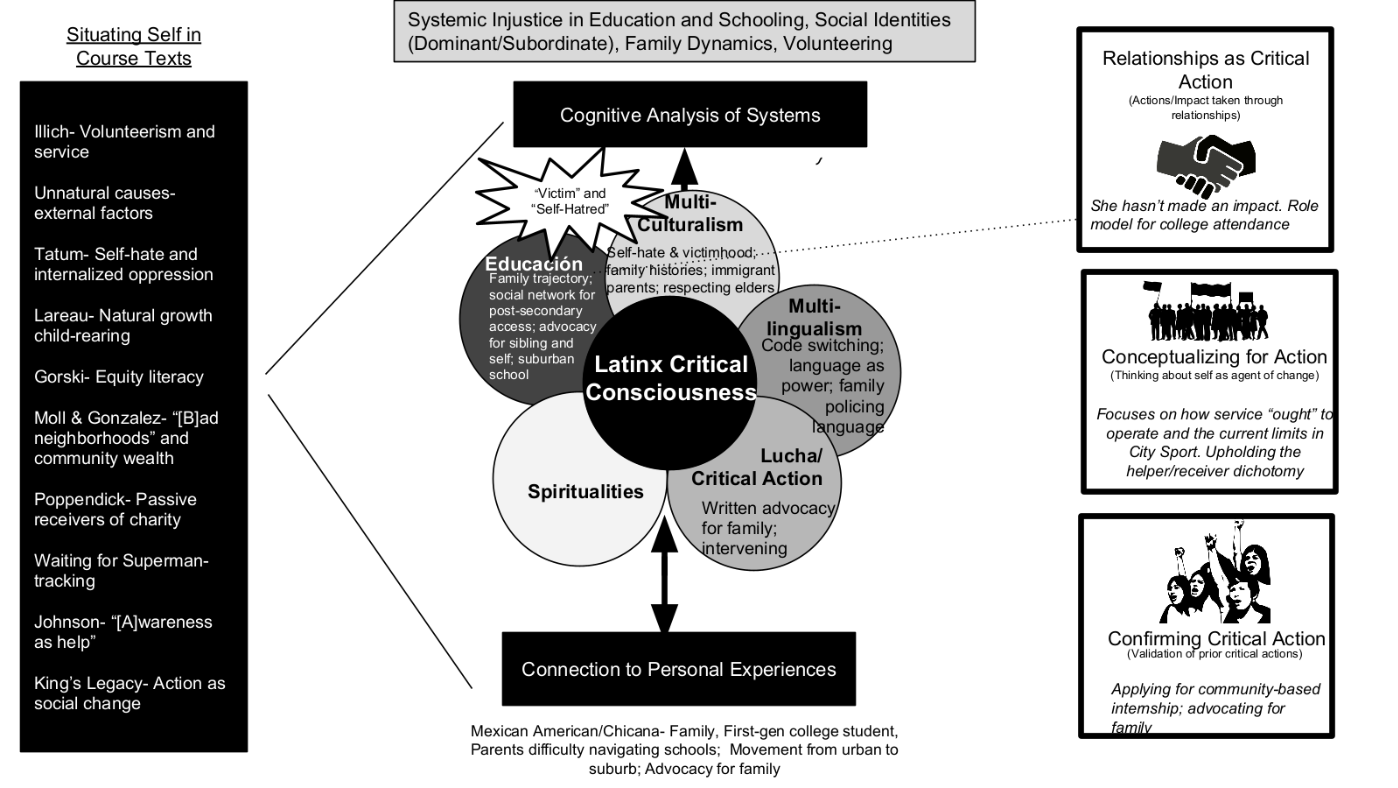

To inform our study, we drew on the literature focused on mestiza consciousnesses (Anzaldúa, 2007), pedagogies of the home (Delgado Bernal, 2001), Chicana feminist epistemology (Delgado Bernal, 1998), and Latina epistemology (Castillo-Montoya & Torres-Guzmán, 2012) to initially conceptualize Latinx students’ critical consciousness as composed of five central elements: multiculturalism, multilingualism, educación, spiritualities, and lucha/critical action (Figure 1). This literature is largely Chicana-based, which provides an entry, but limits this initial framing given the diversity by race and ethnicity of those who identify within the Latinx diaspora. “Latinx,” as an identity term, is contentious because there is a lack of consensus over its usefulness and because it does not account for the racial diversity among people in this diaspora (Dache et al., 2019; Haywood, 2017). We also recognize an increasing interest in using “Latine” instead of Latinx for ease of pronunciation in Spanish (Meraji et al., 2021). We use the term Latinx as a pan-ethnic construct for people who live in the U.S. and have raízes—roots—connected to Latin America and the Spanish-speaking Caribbean. Furthermore, we use the term Latinx to be gender inclusive (Noe-Bustamante et al., 2020) throughout this article, although we did not have participants who indicated that they identified outside of the gender binary. We use Latinx in our work for now but stay attentive to the reality that this is an incredibly diverse community and the term falls short of reflecting that diversity.

“Latinx critical consciousness” is a construct we are using toward the possibility of having some relatable, yet dynamic, aspects of consciousness among the people within this diaspora. We do not hold the view of there being only one Latinx critical consciousness; there may be many. Furthermore, this construct must remain fluid and situational (Beltrán, 2010; Oboler, 1995) as it may not reflect the full diversity of the millions of people who identify within this diaspora.

While this study differentiated each element, as the model in Figure 1 demonstrates, each facet interconnects. It is important to note that the existing literature largely focuses on bi- or tri-culturalism and lingualism, but we decided to refer to these as multiculturalism and multilingualism to acknowledge the diversity and expansiveness of people within the Latinx pan-ethnic label. We also wanted to account for how Latinx students participate in sustaining and evolving multiple cultures and languages (Irizarry, 2007; Paris & Alim, 2017).

Multiculturalism

By “multiculturalism” we mean having an awareness and/or understanding of how one’s multiple cultures, informed by one’s multiple identities, shape one’s beliefs, practices, skills, and knowledge. Delgado Bernal (2001) noted that the Chicanas she interviewed were proud of their Mexican culture and drew on it to affirm themselves and resist assimilation. We extend this point to consider the multiple cultures and identities Latinx students may have and sustain (Irizarry, 2007; Paris & Alim, 2017).

Multilingualism

Similarly, we view “multilingualism” as the many languages and ways of communicating that Latinx students may have that reflect their varied identities and cultures (Irizarry, 2007). Anzaldúa (2007) provides an elaborate explanation of multilingualism born in the context of necessity: “Chicano Spanish is a border tongue which developed naturally. . . . Chicano Spanish is not incorrect, it is a living language. . . . A language which they can connect their identity to, one capable of communicating the realities and values true to themselves” (p. 77). While she was specifically referencing Chicanx people, we recognize that each subpopulation under the pan-ethnic label “Latinx” has a multiplicity and hybridity of languages (Gutiérrez et al., 1999) as part of their Latinx critical consciousness.

Educación

In our conceptualization of Latinx critical consciousness we also include the concept of “educación” as both personal and academic education that informs how one shows up in the world, connects with others, and engages with knowledge (Auerbach, 2006; Espino, 2016; Reese et al., 1995). Research on educación showed that parents do not separate the moral development of a child from their academic learning and see moral development as the foundation for academic learning (Reese et al., 1995). In addition, being bien educado—well educated—is to be someone who shows respect, carries themselves with moral responsibility, values family (Reese et al., 1995), works and studies diligently and with a strong and dedicated effort, and helps others in need (Auerbach, 2006). This intertwining of moral, social, and intellectual learning and development (Gutiérrez, 2012) can be a strength for Latinx students, but it can also be a challenge as they navigate higher education and sometimes resist some of the elements of educación (Espino, 2016). Furthermore, Quiñones (2014) noted that for Puerto Rican teachers in her study, educación was the combination of home and school life, as well as an attitude of persistence and resistance toward socially just outcomes.

Spirituality

Another element of Latinx critical consciousness is “spirituality.” Delgado Bernal (2001) includes spirituality as part of mestiza consciousness, given the importance her participants gave it for navigating higher education. Spirituality supports development of one’s purpose for self and community and serves as a tool of resistance in pursuing educational goals (Castillo-Montoya & Torres-Guzmán, 2012; Dache et al., 2019; Delgado Bernal, 2001). Latinx students may have a broad range of spiritualities that reflect religious traditions from colonialist nations such as Spain but also hybrid practices such as Santeria that infuse African rituals as well as Indigenous spiritual beliefs and practices, among others.

Lucha/Critical Action

The fifth element of Latinx critical consciousness is “lucha/critical action.” We conceptualized lucha/critical action by bringing together the commitment to communities (Delgado Bernal, 2001) as well as the resistance and active effort to liberate oneself and one’s community (Castillo-Montoya & Torres-Guzmán, 2012; Dache, 2019; Yosso, 2005). Lucha/critical action is the individual and collective, visible and subtle actions one takes to resist oppression and work toward liberation. This type of lucha/critical action is also passed down culturally. Delgado Bernal (2001) noted, “It is through culturally specific ways of teaching and learning that ancestors and elders share the knowledge of conquest, segregation, labor market stratification, patriarchy, homophobia, assimilation, and resistance” (p. 624). She referred to this critical action as “transformational resistance,” defined as “a resistance for liberation in which students are aware of social inequities and are motivated by emancipatory interests” (p. 625). We view this aspect of Latinx critical consciousness as not only intergenerationally transmitted but also reimagined by each generation within its own socio-historical contexts.

Taken together, these five elements represent our initial framework of Latinx critical consciousness. It served to guide us as we analyzed the data to help us identify how Latinx critical consciousness might be developed through a sport-based youth development CSL course and the ways it might not be.

Method

To address our research questions, we engaged in a content analysis of six Latinx students’ written reflections in a sport-based youth development CSL course. These data were based on a larger research project focused on the learning and development of students who participated in this course over the span of a decade. The course is designed to support undergraduate students’ learning through a service-learning opportunity facilitated by City Sport—a sport-based youth development campus-community partnership program within a small urban neighborhood (Heartland) that has been in place for over 17 years (all names are pseudonyms).

Heartland is a small urban town with mainly Afro-Caribbean, African American, and Black and non-Black Latinx residents. University staff, faculty, and students collaborate with local schools and community-based organizations to deliver programming to elementary and middle school students focused on physical education, health and nutrition, life skill development, and academic enrichment. City Sport has also supported academic opportunities for Heartland community members who seek to attend the university. City Sport values relationship building and trust as foundational principles influencing their sustained relationship with Heartland.

Course Context

The course is offered within a sport-leadership program at a persistently white research university (PWI) in the northeast part of the United States (Heldke, 2004). The course is four credit hours and is also designated as writing intensive. The same instructor taught the course and oversaw the City Sport program during the time that student participants took the course. Course content focuses on racial inequalities in social systems, with a focus on positive youth development through sport participation. The course enrollment averages over 30 students. In addition to course readings and classroom discussion and activities, 20% of each student’s grade is based on completing 40 hours of service through City Sport. Students are required to write a series of five structured reflections throughout the semester. Our analysis focused on these five reflections.

We viewed the course as CSL given its focus on having students reflect on power, privilege, authentic relationships, and injustice, elements noted by Mitchell (2008) as parts of a CSL practice. We recognize, however, that while we view this course as a CSL course, other elements that contribute to a CSL course were not necessarily reflected in the City Sport program, such as a social change orientation and building power for community members.

Data Sources

Students

After course completion, students were asked if they would be willing to have their course reflections included for data analysis in the larger study. Of those who consented, six identified as Latinx, three of whom included additional ethnic or racial identifications such as Mexican American or Afro-Latina. Of the six, three identified as men, and three identified as women. While the six students of this study all enrolled in the service-learning course, they did not enroll in the course during the same semester. The six students enrolled in the course between 2016 and 2018, during which the course was taught by the same instructor. All identified some portion or all of their K–12 schooling experience as urban within a low-income neighborhood. Three of the participants identified as moving from an urban type of schooling environment to a suburban schooling environment during their pre-collegiate education.

Reflections

For each participant, we analyzed five course-required reflections, for a total of 30 reflections. The five reflections were informed by prompts that remained the same throughout the semesters of enrollment reflected across the six students. For instance, the second reflection, due usually after the 12th class session, prompted students to write a letter to one of the authors from the course curriculum to discuss how one of their identities (either targeted or dominant) has impacted their life, schooling, or social, cultural, or financial assets. Other reflection prompts included a quote from either a reading or another source so that students could reflect on the quote and connect it to other course readings, their own experiences in sport, the service component of the course, and/or their post-course aspirations.

Analytical Strategy

We sought to identify the aspects of Latinx critical consciousness that Latinx students revealed in their course reflections and how those aligned with or went beyond the focus of the course. We framed our inquiry by viewing each participant as a “case” composed of their five reflections. To analyze the content of their reflections, two of us took the role of reading and analyzing three cases each. While reading through our cases’ reflections, we used “what I know now” memos (Maietta, 2006) for each reflection to track what was surfacing and created a cover memo for each participant that explained what we noted across that participant’s five reflections. A third research team member read through these memos, revisiting the initial reflections and inserting additional notes when needed. In addition, we developed several matrices to extract relevant information from the memos related to our research questions. Again, two of us extracted from our three cases with a third researcher reading through the content of the matrices and adding notes when needed. Throughout these stages, we met as a team to discuss our thoughts, questions, and relevant literature and kept track of our thinking in a variety of team memos. We also analyzed the course syllabus, specifically the authors of the assigned readings as well as the course objectives.

We then co-constructed a visual display based on the conceptual framework to create an analytic device for further analysis of the cases. Two of us pulled information from the matrices for each of the cases and entered the information into the display for each student. A third researcher went through the displays, memos, and matrices to provide feedback, when needed. These analytical tools help researchers systematically display a full data set relevant to a research question to understand each case, see relationships among cases, and draw conclusions about the larger phenomena (Miles et al., 2019).

We continued to refine each case display as we proceeded in analysis and writing. In the final display for each case (see Figure 2 for an example of the display we created for each case), we accounted for the content in that specific student’s reflections about the course texts/resources (left side), the systemic issues they addressed (middle top section), aspects of their Latinx critical consciousness displayed in their reflections (middle section), their personal characteristics (middle lower section), and the luchas/critical actions they wrote about (right side). We also noted choques, which we define and discuss below, with jagged images (middle section) and drew dotted lines between aspects of Latinx critical consciousness and critical action.

Research Positionalities

Our positionalities inevitably shaped the way we entered and engaged in this research. We each have a different relationship with City Sport, allowing for both insider and outsider knowledge. We also each have different social identities that informed our thinking, the questions we raised, the areas where we had more learning to do, and the collective knowledge we drew on to thoughtfully analyze students’ reflections.

Milagros, while not directly involved with City Sport or this course, brought her research background and interests in culturally relevant teaching in higher education. More specifically, she brought in knowledge based on her research on teaching that supports racially minoritized students’ learning and development of critical consciousness through academic courses. Milagros identifies as a cisgender heterosexual first-generation Puerto Rican scholar who is multi-racial with white-presenting privilege. In this project, Milagros drew on her own lived experiences to inform the conceptual framework and our discussions during analysis.

Garret’s research focuses on the intersections of higher education’s civic engagement practices and rural community organizing and development. He is specifically interested in how rural people organize to build more democratic economic and community institutions using service-learning and community-based research. He interned with City Sport in 2016 and taught a one-credit abridged version of the four-credit course during one semester. Garret identifies as a cisheterosexual white man and realized that the course and program deeply impacted his own learning because of his privileged position. Since his initial involvement, this attraction has been complicated as he has co-instructed other service-learning courses that emphasize radical approaches to analyzing injustice and seeking liberation.

Ajhanai researches topics related to leadership, gender, race, and inclusion in the realm of collegiate athletics. As a former student-athlete, Ajhanai uses her experiences within collegiate athletics to provide insight to her research studying and working with athletic departments. Ajhanai served as the teaching assistant for this course for one semester. This was the first service-learning course Ajhanai participated in and she gained most of her insight about City Sport during this time. While serving as a teaching assistant, Ajhanai, who identifies as a Black heterosexual woman, perceived the class to be more impactful for white students and questioned how some Black and other racially minoritized students experienced the course, given their silence during in-class discussions.

Limitations

We want to note two study limitations. First, the reflections we analyzed as data were written for a course grade and in response to prompts written by the course instructor. As such, we are unsure if students’ responses reflected the full complexity of their thoughts or experiences. Second, only one of us is professionally focused on sport as a field of study. As such, we recognize that our attention in this course was less on the subject matter (sport-based youth development) and more on how the course supported (or not) Latinx students’ development of Latinx critical consciousness. In this sense, we may have overlooked subject matter nuances that are important for understanding Latinx critical consciousness within the context of sport youth development.

Findings

In addressing our research questions about the aspects of Latinx critical consciousness revealed in Latinx students’ course reflections and how those aspects aligned with the course or went beyond the course’s focus, we identified two findings. First, we found alignment between the course and aspects of Latinx students’ critical consciousness, namely in the areas related to multiculturalism, educación, and lucha/critical action. We also, however, found that these very aspects of critical consciousness were limited, and other aspects of Latinx critical consciousness (multilingualism, transnational conocimiento) were fully overlooked in the course. In what follows, we discuss these two findings.

Latinx Consciousness Emerging Through a Sport-Based Critical Service-Learning Course

We found that multiculturalism, educación, and lucha/critical action did align with the course. In what follows, we discuss the aforementioned aspects of Latinx critical consciousness and illuminate them through excerpts from students’ reflections.

Multiculturalism: Situating Social Identities in Larger Sociopolitical Structures

The theme of multiculturalism is evident in how participants addressed their social identities in relation to course material, as they discussed how white privilege, structural injustice, power, social class, and wealth distribution informed their social experiences. For example, Alex shared in a reflection how his parents’ immigration journey impacted his social class:

Interconnected with so many other big systems in our society . . . I will show how my social class has affected or determined where I could live, my education experience, and how your social-class creates this perception about who you are as a person and many other false accusations and also analyze how social mobility is not so possible in our society.

We found this type of connection between various social identities (race and class; immigration experiences and class) across our participants’ reflections. We also found that all our participants reflected on their identities, particularly as Latinx students, within the context of a predominately and persistently white institution as they addressed navigating an educational institution hostile to their existence. This whiteness was evident also in the course as the curriculum focused on issues of inequality, including race, but did so primarily from the perspective of white authors. It is from within this curriculum that Latinx and other racially minoritized students in this course had to engage in learning. Only two articles/chapters were by Latinx scholars. Below, we offer additional examples of students navigating the persistently white institution.

Educación: Examining Educational Systems

Regarding educación, we analyzed how the students addressed formal educational systems, especially since the course focused on educational inequalities in the United States. We considered whether participants wrote about moral aspects of education or the informal learning from their families. All six participants connected the structural inequalities of the K–12 schooling system to their own, often negative, experiences. The Latinx students often compared their K–12 schooling to that of their white classmates to illuminate the inequalities presented in the course curriculum. As Alex shared, “Because I lived in a working-class town my educational experience and curriculum wasn’t equivalent to my fellow classmates here at [University]. I’ve always felt like I was always playing catch up with my peer’s [sic] in the university.”

Four participants reflected on course content examining school tracking as they wrote about their personal schooling experiences. Erica highlighted in her fourth reflection how she was placed into a college readiness track:

I actually never realized that I was a student that was set on an honors path since middle school. I was always on the track that put me ahead of my classmates, where I would take high school classes in middle school and college classes in high school, which literally was setting me up to go to college.

Erica realized how she benefited from tracking but still perceived the notion of tracking to be inequitable. The course, however, did not expand beyond formal education to address the more holistic concept of educación. We discuss this further in our second finding.

Lucha/Critical Action: Valuing Relationships and Conceptualizing for Action

Across all participants, we found they also wrote about lucha/critical action, though we identified a typology of three distinct critical actions: engaging in relationships as critical action, conceptualizing for critical action, and confirming critical action.

Two of the students (Erica and Ivette) reflected on engaging in relationships as critical action. For instance, Erica wrote in her reflection:

People may think that the [Heartland] students don’t notice when we are there or when we aren’t. I disagreed with this statement in class because that isn’t true for all the cases. I have been pretty consistent with going to the Elementary school on Friday mornings.

In this statement Erica is displaying lucha/critical action with a commitment to the community through consistency and relationship, which are key course themes.

Other students’ (Jonathan and Miguel) writings conceptualized what action meant within their service and how to take more risks against racism and injustice. For instance, Jonathan wrote the following:

Taking this class has given more social awareness. I feel like I am now obligated to speak up and make people feel uncomfortable about the reality in which we live. The decisions that we make have a chance to impact the community and everyone around us.

In this example, Jonathan showed how he individually must interject against racism due to his increased awareness of systemic injustices presented in the course.

The two remaining students (Alex and Carolina) were already involved in luchas/critical actions prior to this course. As these students learned new concepts and better understood the larger social system, their pre-course critical actions and future critical action aspirations were confirmed as necessary for community uplift. For instance, Alex intended to pursue a career as an educator, and this course reaffirmed the type of schooling environment in which he hoped to work:

[W]hen a student sees a teacher that is of the same skin color as them this gives them a vision of, “oh that person kind of looks like me, maybe I can be like them one day.” This is why I want to work with urban students. I want to give them a “ripple of hope” [Loeb, 2010] of seeing themselves at [sic] having a career of their choosing one-day.

Given that two of our participants had already thought about civic engagement or social action prior to the course, it seems the course served as a vehicle to affirm their critical action commitments but did not seem to further develop their critical actions.

Latinx Critical Consciousness Limited in a Sport-Based Critical Service-Learning Course

While Latinx critical consciousness aligned with the CSL course, we also identified how the course limited or did not advance it. These included aspects of multiculturalism, multilingualism, and educación. In addition, from our analysis we found aspects of what seemed like critical consciousness but were not part of our initial framing. These include (a) choques, or moments of cultural clashes, and (b) transnational conocimiento—awareness and understanding of lives, realities, relationships, and policies that cut across national borders. These two concepts were not the focus of the course but nonetheless surfaced in these students’ reflections. We do not include any further information on spirituality as none of the study participants wrote about spirituality in their reflections. We are not sure if this is because the writing prompts did not foster reflection on spirituality, if this is a changing aspect of Latinx critical consciousness, or if spirituality manifested in other ways for these students that was not evident in their reflections.

Multiculturalism: Going beyond Binaries

As noted earlier, under multiculturalism, students drew upon course content to make sense of their experiences as it related to their multiple social identities. One of the most cited course readings was an excerpt from Tatum (1997), a scholarly piece focused on the complexities of dominant and subordinate identities. However, the incorporation of these concepts in class discussions emphasized the juxtaposition of dominant and subordinate racial identities. Participants complicated this racial binary approach by reflecting intersectionality of systems that impinge on their identities (Crenshaw, 1991). In doing so, the Latinx students in this study used this reading to examine their own lives, often merging multiculturalism and educación as demonstrated by Jonathan:

I identify as Mexican American which makes me a part of a subordinate group within the United States. Although, I am very privileged to be born in the United States and not have to deal with immigration laws and/or the fear of getting deported. I still must worry about racism and stereotypes because of my ethnicity. . . . Because of this I’ve had to work harder than those of the dominant group in order to stand out and be held to the same standards of those in the dominant group.

Here Jonathan noted that despite possible privileges of being a U.S. citizen, he does not experience that full privilege because of racism and stereotypes held against him as a Mexican American. We noticed he incorporated the “work harder” value that is part of educación to counter this racism and the inequality that ensues.

Related to the notion of dominant and subordinate identities, we also noticed that Latinx students referenced how white privilege adversely impacted their educational experiences. Connected to his reading of McIntosh’s (1998) work, Miguel reflected upon his childhood growing up Latino in a suburb in the Northeast: “[B]eing surrounded by classmates like me would have stopped me from being forced into the role of the token Latino kid, who had to speak for all of the people in my racial group.” He experienced tokenization as part and parcel to his schooling, a hidden curriculum imposed on racially minoritized students in predominately white educational spaces.

While this theme drew out retrospection from students on their childhood experiences, other participants took issue with the presentation of course materials directed at white people. Ivette, for example, challenged the notion of how white privilege, as it is presented in the course, emphasized the benefits white people receive rather than the harm imposed on racially minoritized people, specifically on Latinx people. She wrote the following:

If you believe stopping oppression can be done by spreading the acknowledgement that white people have White Privilege, then also spread the stories of how minority or Hispanic lives have been affected by White Privilege or the systematic oppression. Maybe then can we address issues about how the system works and work to fix and diminish inequality.

We found this reflection to be an example of the multiculturalism Latinx students brought into their reflections and how they viewed the world from their racially minoritized position while naming oppression and centering liberation. What was less clear, however, was whether the students had an opportunity to examine how white privilege is extended to some degree to white-presenting racially minoritized people, including those within the Latinx diaspora.

Multilingualism: Reflecting and Using Languages

Five out of our six participants discussed issues or experiences related to multilingualism. These participants wrote about the role of language within their lives, as both a tool for power and advocacy through the use of code switching as well as a challenge in their formative experiences. Additionally, students brought their multilingualism into their CSL experience. Three participants noted using Spanish in City Sport with young people in Heartland. Erica examined the limited support for English-language learners within the school and used Spanish to connect with City Sport youth. Many of these participants connected their use of Spanish in Heartland to growing up with parents who were primarily Spanish speakers. For instance, Miguel wrote about his personal experiences having parents who “lacked confidence” in their English-speaking abilities. He reflected on how he often translated for his parents and how this unique stress informed his childhood experiences. Miguel wrote:

I had to translate a lot of the times for my father when it came to doctors’ appointments or meetings with teachers. When it came time to apply to college I struggled. As the first member of my family to go to college my family was not familiar with how the process worked.

In this reflection, we learned about the significance of language in Miguel’s experiences, as his bilingual ability is a skill that helps his family. Unfortunately, many colleges/universities do not offer bilingual information to prospective students and their families, creating issues of access and equity.

In addition, students wrote about their often-challenging personal experiences navigating English-dominated schooling environments. Carolina noted that she saw her white peers in the course police the language of youth in Heartland in ways that her own family scrutinized her and her siblings’ language to assimilate into the dominant culture. She also discussed using language and her educational status to advocate for her sister experiencing differential treatment in school. Carolina wrote the following:

Just a few months ago, my youngest sibling was asked inappropriate, leading questions regarding her legal status here in the U.S. So instead of going into the school and arguing with the principle [sic]or staff at the front desk out of fear of being “that loud, angry Latina girl,” I decided to write a letter because I would be able to fully articulate my thoughts and fully express the severity of the issue in a way they would understand.

Carolina and other participants were conscious of how language is used to both marginalize and empower people of the Latinx diaspora and wrote about it even if multilingualism was not a focus of the course.

Educación: Going beyond Schooling

As noted above, all six of our participants reflected on education as the course primarily focused on schooling; however, five participants also raised issues related to educación, which integrates moral, social, and intellectual learning and development. Two participants wrote about parenting styles related to formal schooling, and three wrote about the knowledge and skills they gain from their families. For instance, Carolina reflected upon her own educación and her family’s style of child-rearing:

I grew up in a traditional Mexican family where I was taught to respect my elders, which meant to do as I was told and never question their authority, a characteristic of natural growth child rearing (Lareau, 2003). If my mom told me I couldn’t go out to play with my friends, there was no way of negotiating and therefore would later affect how I interact with authority figures.

Participants also demonstrated educación in their reflections on their mutual commitment to academic success and to a racially and ethnically diverse community with which they related. Miguel shared the following in his reflection:

Admittedly, before this class and even entering my first sessions with City Sport I went about it the wrong way. I thought it would be great because I would look like a lot of the kids and can thus serve as a role model for them moving forward, but that simply [was] not the case. I have had privileges in my life that they may not, so telling them about my experiences would be useless.

What Miguel, and other students, surfaced in these reflections is the tension between being a racially minoritized person and the inequalities they have confronted or continue to confront, particularly within schools, and the privileged aspects of their identities, such as being a university student, having U.S. citizenship, or moving to suburban areas. We refer to this tension as choques.

Choques: Working through Ambiguity and Tensions

Choques are “both moments of contestation and creative production” (Torre & Ayala, 2009, p. 390) that emerge from “a cultural collision” (Anzaldúa, 2007, p. 100). They are “originally produced from the violence of colonization, the experience of cultural collision, or choque, is fundamental to a Mestiza consciousness” (Torre & Ayala, 2009, p. 390). Four of the six participants reflected on their experience as Latinx students at a PWI and the ways in which they have been subordinated by whiteness in the institution. Alex connected a course reading on social class and education to an experience of a collegiate peer devaluing his childhood neighborhood. Alex asserts, “This boy made the assumption that since my town isn’t known for being rich, no student would be able to afford or even get into a college known for great academics.” Other participants articulated similar experiences or tensions among their own educational trajectories, the comparison to wealthier white peers, and their marginalization and exclusion within the persistently white educational spaces. While the course content emphasized K–12 education, and reflections aimed for students to examine educational inequality in society as well as in Heartland, these students also connected the content to their immediate experience at the university.

We also saw choques emerge in students’ reflections as they experienced tensions with the course content and aspects that make up Latinx critical consciousness. Carolina expressed a choque in her final reflection of the semester as she was coming to see herself as simultaneously a marginalized person, but also strong because of her family’s history of resistance and persistence:

Maybe I didn’t realize how much I had been oppressed that it wasn’t until I took the class that I realized how much these systems have effected [sic] every aspect of my life. Maybe it has to do more with the fact that I know what my parents lived through and what my grandparents lived through that despite the oppressive systems that we live in it is still better than what they had, so instead I have felt grateful for the opportunities that I have been given.

Carolina seems aware of her family’s resistance against systems of oppression they confronted and how she is in a “better” position because of their persistence. This is a choque that merits further unpacking in a learning space as embedded within it are opportunities for examining intersectionality.

Transnational Conocimiento: Drawing on Knowledge from across National Boundaries

In addition to the various facets of Latinx critical consciousness we have discussed so far, we also found that the students drew upon their global awareness, understanding, perspectives, and relationships in their connections to course concepts, which we refer to as “transnational conocimiento.” Drawing on the work of Anzaldúa (2007), Gutiérrez (2012) explained that conocimiento is having knowledge of something as well as knowing something or someone because you have direct familiarity with it. In this sense, conocimiento accounts for embodied knowledge.

We specify the type of conocimiento the students displayed in their writings by focusing on the transnational (border crossing) nature of their reflections. Five of our participants had parents who emigrated from a Latin American or Caribbean country or U.S. territory (euphemism for U.S. colony), and all our participants addressed immediate or extended family in Latin America or the Caribbean. Nearly every participant addressed the sacrifices their parents or grandparents made to come to the mainland United States. With this, students come to grapple with their relationship of “home” as part of the diaspora and their positions as both privileged and marginalized. For example, Ivette used Illich’s (1968) “To Hell With Good Intentions” to think about her mother when they visit family in Central America:

I find my mom’s demeanor before we travel to [Central American country] similar to those volunteers in the readings. Although she wants to help out and give my poor family clothes, I can see that they look at us in a powerless or even humiliated way because we live in a healthier environment with better resources than them.

In this way, Ivette reflected beyond the course content and the service experience to draw on her own transnational life experience.

Furthermore, the Latinx students in this study were grappling with, reflecting on, and navigating multiple worlds, nations, and policies, giving rise to what we are referring to as their transnational conocimiento. For instance, one student (Carolina) wrote about using her university education to write a letter in support of her uncle so that he would not be deported. This transnational conocimiento extends beyond the focus of the course and exceeds the understanding of “service” considered in the course solely within the U.S. context.

Afro-Latinidad. For Erica, this course brought forward a different type of choque and transnational conocimiento. To be more exact, she noted the absence or even the distancing of Blackness within the Latinx experience. In her reflection, Erica wrote about the lack of educación around her Black identity as an Afro-Latina:

I feel that I was never taught what it was like to “be Black.” . . . Even today as a [age] I don’t know how to take care of my hair because no one necessarily showed me how. This lack of knowledge of an entire culture that I still identify as has shaped me to be the person that I am today.

Instead of educación around her Afro-Latina identity, her family emphasized their specific heritage connected to a Caribbean and a Central American country. This erasure of Blackness within the Latinx experience robbed Erica from living her full humanity. In Erica’s words, “One thing that I feel like I’ve been denied in my life is knowledge on my full identity.”

It is unclear if this course offered students the opportunity to consider Black identity as a transnational identity or supported an examination of Blackness within the Latinx diaspora. Given that five of the six Latinx students’ reflections did not interrogate race within the Latinx diaspora, we note that this seems like a learning opportunity about racial inequality (particularly within sport) for CSL courses to address.

In sum, transnational conocimiento was reflected in students’ reflections as they addressed a range of topics that require some personal experience that transcends nations and diasporas. This seems to be an important aspect of Latinx critical consciousness that we initially did not consider.

Discussion and Reflection

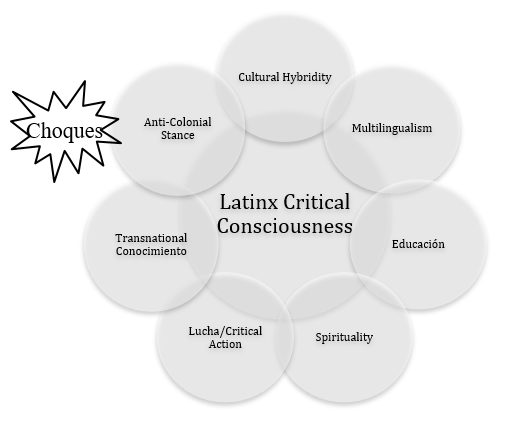

Our findings lead us to raise two main points of discussion. The first is the reality of dominant discourses in CSL practices perpetuate whiteness. Second, we found elements of Latinx critical consciousness that aligned with this course and aspects of this consciousness that went beyond the course. This calls us to consider the need for more specified understanding of critical consciousness relative to CSL. As a result of this study, we revisit the importance of collective action and add three elements to our framework on Latinx critical consciousness (choques, transnational conocimiento, and anti-colonial stance). We discuss each point in turn.

Dominant Discourses in Critical Service Teaching and Learning

As the service-learning literature has largely ignored historically marginalized students, and Latinx students in particular, our study illuminates several key considerations. First, while CSL course instructors may attempt to include one or more of the pillars of CSL, they can still overlook complexities relevant to racially minoritized students, in this case Latinx students. By centering the learning of white students to understand individual and societal oppression, instructors are inherently supporting only a fragment, if any, of Latinx students’ development of Latinx critical consciousness. Although the course we studied was not focused specifically on Latinx critical consciousness, it did prioritize consciousness raising. The complexity with which our participants analyzed their social world and demonstrated their Latinx critical consciousness extended course content in several different ways, most notably in their demonstration of choques and transnational conocimiento.

This finding aligns with what other scholars who critically examine service learning have found, which is that service-learning is largely rooted in “a pedagogy of whiteness—strategies of instruction that consciously or unconsciously reinforce norms and privileges developed by, and for the benefit of, white people in the United States” (Mitchell et al., 2012, p. 613). Such pedagogy can minimize the transformational impact of service-learning teaching particularly for racially minoritized students (Mitchell et al., 2012). Central to our finding here, scholars have also noted the following:

Students in service learning classes rarely have opportunities to learn about their own or other’s racial identity development, even though many of the affective responses to service learning, from guilt to anger, are rooted in various stages of such development. (Mitchell et al., 2012, p. 615)

As previous members of the course instructing team, Garret and Ajhanai had different reactions to this finding. Garret, when thinking about his time with City Sport, recollects feeling impressed by how City Sport focused course content on power, privilege, and oppression. Yet this study raised central questions about what student learning is lost in this process. He wonders what would happen if instead of emphasizing the broad notions of power, privilege, and oppression, this course focused on specific oppressive systems—racialized capitalism, patriarchy, settler colonialism—and centered grassroots resistance. This may be particularly necessary in courses offered by fields or disciplines with specific oppressive systems as their foundation. For instance, sport management—the context for this course—is grounded in racialized capitalism, patriarchy, and settler colonialism. Chen and Mason (2019) highlight:

The recognition of settler colonialism within sport management, then, calls for consideration of how settler colonialism, in conjunction with capitalism, imperialism, and heteropatriarchy, has impacted on the ways sport is understood, practiced, and managed and, accordingly, encourages new visions of what a more just sport world might look like for all peoples. (p. 385)

Along with their valuable explanation of how settler colonialism shapes sport, Chen and Mason offer critical questions to unveil and challenge settler colonialism within sport management programs. Some of these questions include:

How are colonial views embedded in collegiate sport programs, names, and logos, and what impact do they have on Indigenous groups? . . . Where are new sports facilities being built for events? What is the history of the land the facilities are built on? (Chen & Mason, 2019, p. 387)

Reflecting on this finding as well, Ajhanai saw the difficulties of constructing a course actively attuned to the racial identity development and critical consciousness of undergraduates of disparate racial backgrounds. She wonders what course materials can be included to encourage students to go beyond a binary perspective of privilege and not privileged so they can consider important nuances when examining identity and power in our social world through sport. For example, Ajhanai wonders how course material focused on sport can more clearly draw out how socio-economic privilege differs from racial privilege and the significance of these differences while also considering how privilege is assessed based upon a comparison group. Such complexity is illuminated by students in the sample, as several perceived themselves as more privileged in comparison to family members living outside the United States but also experienced being minoritized within the United States. She wonders how CSL learning materials can complicate perceptions of privilege to decenter the U.S. lens of whiteness or settler colonialism. Ajhanai’s reflection aligns as well with existing scholarship that points to racially minoritized students having lived experiences that can extend our notions of service and the necessity of conceptualizing those experiences as assets in their knowledge base (Mitchell et al., 2012).

How Latinx Critical Consciousness Can Inform Critical Service-Learning

As we imagine what justice could be like in CSL moving forward, we must also reconcile with how we as instructors have been complicit in limiting Latinx critical consciousness development. In what follows, we note the three additions we make to our initial framework of Latinx critical consciousness and note how CSL instructors can support development of each.

Unpacking Choques

One finding that intrigued the research team, and highlights the tensions of Latinx critical consciousness, was choques. We saw these choques in the writings of the study participants, and it calls us to consider how CSL courses can attend to these choques by helping students process them and further develop from these complexities. For instance, CSL instructors can integrate readings or other resources into the core aspects of the course to support how students think through and name choques, especially as students navigate the complexities of race (e.g., colorism, anti-Blackness) and complicate understandings of race within the Latinx diaspora in a manner that goes beyond a white U.S. settler colonialism lens. It is important for instructors to understand that what might be choques for Latinx students given their lived experiences (which vary within this pan-ethnic population) might not be choques for other students given their respective positionalities. When students experience choques, they may name them or remain silent given what is happening in their course context (Mitchell et al., 2012). For this reason, it is important for instructors to critically reflect and build skills to address choques. These choques may at times be with the curriculum, with the service experience, with the instruction, or interpersonal in nature (among peers) (Mitchell & Donahue, 2009). Instructors can foster learning from these choques or they risk upholding white pedagogy while underdelivering the potential transformation that is possible in CSL, particularly for racially minoritized students (Cahuas & Levkoe, 2017; Cann & McCloskey, 2017; Mitchell et al., 2012).

Incorporating Transnational Conocimiento

Second, we recognize students’ transnational conocimiento can be an asset for their critical consciousness. This insight both extends our initial framework of Latinx critical consciousness and calls for CSL courses to consider how such conocimiento could be drawn on and further developed through the course and service. Within this transnational conocimiento is the potential for understanding race, racism, and other systems of power and oppression (e.g., citizenship, social class) from a transnational lens as well. Afro-Latinx students may have a deep understanding of their connection to the African diaspora in a way that white-presenting Latinx students may not, but all Latinx people are responsible for knowledge of their African heritage and of the anti-Blackness that is pervasive within the Latinx community. Yet, in conversations about race, this type of nuanced complexity is often missing, leaving students like Erica to have to learn about their Afro-Latinx identity on their own. This not only harms Afro-Latinx students, but it perpetuates a centering of whiteness broadly and within the pan-ethnic Latinx diaspora. As Dache et al. (2019) noted, we must “(re)situate, (re)negotiate, and (re)present Blackness within Latinidad” (p. 139).

Thus, CSL courses, embracing transnational conocimiento, can expand the scope through which they examine injustice, in the trite expression “think globally, act locally.” CSL represents an opportunity to examine local issues of injustice and connect them to systemic issues that expand beyond the borders of a nation-state. Specific to Latinx students, Dache et al. (2019) call for “a historical grounding of Black transnationalism” that emphasizes the connection across Black struggles around the globe (p. 139). Given that City Sport in Heartland is home to a number of first- and second-generation Haitian Americans, Puerto Ricans, and other transnational communities, it is well positioned to create a community partnership with global linkages within the CSL course content and student reflections.

Related to this idea of transnationalism, we also revisit our use of “multiculturalism” as a term to capture the multiple cultural identities that shape one’s beliefs, practices, skills, and knowledge and the negotiations involved in navigating multiple worlds and cultures. These multiple cultural identities can be informed by familial cultural heritage (Delgado Bernal 2001), but also generate from cultural sharing that happens within communities where one lives, particularly among youth (Irizarry, 2007; Paris & Alim, 2017). Given what we learned here about the presence of transnationalism for Latinx students and conversations with colleagues about it, we think that the term “cultural hybridity” could be a better term to reflect the complexity we were aiming to illuminate with the term “multiculturalism.” Cultural hybridity is both the coming together of cultures that creates new cultures as well as the knowledge one develops in the negotiation of identities (Gutiérrez et al., 1999; Irizarry, 2007; Paris & Alim, 2017). Given the complexity and fluidity that “cultural hybridity” offers, we use it in the updated model below in hopes it can guide future work.

Advancing an Anti-colonial Stance

Thinking specifically about people who make up the Latinx diaspora, it seems necessary that critical consciousness include an anti-colonial stance. This relates to transnational conocimiento as well, since colonialism negatively impacted (and continues to impact) people all over the world. We did not begin with transnational conocimiento as part of Latinx critical consciousness, but we think it is important to add after recognizing how centering Westernized knowledge in a course curriculum perpetuates a colonial logic in learning. Without an anti-colonial stance in CSL courses, the knowledge of everyday people inclusive of transnational knowledge can be absent from the curriculum, and specifically within sport-based courses. Even this project we engaged in perpetuated a colonial logic as we did not have data, nor did we previously consider the critical consciousness Heartland community members and how this course draws on and advances their consciousness. This is an opportunity for reciprocal learning as we recognize that community members have a wealth of knowledge they can bring to community-academic partnerships (Castañeda & Krupczynski, 2017).

An anti-colonial stance in CSL would entail “(a) acknowledgment of settler colonialism . . . , (b) incorporating anticolonial and decolonizing methodologies that counter and resist dominant narratives in CCSL as well as (c) a relational shift in the way that community–university partnerships are envisioned” (Santiago-Ortiz, 2019, p. 48). In addition, we believe an anti-colonial stance also acknowledges the wisdom of transnational lives and communities, including a Black transnational understanding within the Latinx diaspora. Below we include our updated model for Latinx critical consciousness as a result of this study that includes anti-colonial stance, transnational conocimiento, and cultural hybridity. We invite other scholars to expand on and modify this framework, as needed. For instance, future research can consider whether race should be a part of transnational conocimiento or a separate element.

Conclusion

In this study, we sought to identify the aspects of Latinx critical consciousness that Latinx students revealed in their sport-based youth development course reflections and determine how those aspects aligned with the focus of the course or extended beyond the focus of the course. What we learned is that certain aspects of Latinx critical consciousness emerged and aligned with the course, while other aspects were limited or altogether beyond the scope of the course. The findings from this study have implications for how we conceptualize and develop minoritized students’ critical consciousness and how we can advance CSL to more directly advance such consciousness. Furthermore, the findings highlight the importance of incorporating an anti-colonial stance within critical service-learning. CSL instructors can work toward this end by highlighting that varied knowledge and lived experiences are valuable for CSL, decentering the United States as the primary location of knowledge production, even if the service site is in the United States, and emphasizing reciprocal learning in community-university partnerships.

As two previous co-instructors of the course, Garret and Ajhanai are left wondering how the universality of sport can be more fully leveraged through structured activities and reflection to illuminate the transnational conocimiento across the CSL experience, specifically since many of the community members are part of the Caribbean diaspora. Relatedly, we are revisiting how we can more fully incorporate sport as sites where Latinx critical consciousness can be developed, given that youth, amateur, and professional sport all reflect broader inequalities and are sites where we can illuminate and address social issues. We specifically wonder how intersectionality (Crenshaw, 1991) and a system approach to examining and collaborating in Heartland could bring forward anti-colonial practice that challenges settler colonialism. We also wonder how an anti-colonial stance can be advanced if we work to more fully center community wisdom and the nurturing of a relationship to the land in how we approach our classroom and community experiences.

Acknowledgment

We are grateful for the participants who were willing to share their reflections for this project. We also appreciate the feedback provided by our Association for the Study of Higher Education (ASHE) discussant when we presented this paper during the ASHE conference in fall 2020. We also appreciate the intellectual work of Delmy Lendof within the NASPA Latinx/a/o knowledge community which advanced our thinking relative to the use of Latinx as well as Luz Burgos-Lopez for advancing our thinking in terms of anti-Blackness within Latinidad.

Author Note

Milagros Castillo-Montoya is an Assistant Professor of Higher Education and Student Affairs in the Department of Educational Leadership at the University of Connecticut. Garret Zastoupil is a doctoral candidate at the University of Wisconsin–Madison. Ajhanai Newton is a doctoral candidate at the University of Connecticut.

References

- Anzaldúa, G. (2007). Borderlands/la frontera: The new mestiza (3rd edition). Aunt Lute Books. (Original work published 1987).

- Auerbach, S. (2006). “If the student is good, let him fly”: Moral support for college among Latino immigrant parents. Journal of Latinos and Education, 5(4), 275–292. https://doi.org/10.1207/s1532771xjle0504_4.

- Barrera, D., Willner, L. N., & Kukahiko, K. I. (2017). Assessing the development of an emerging critical consciousness through service learning. Journal of Critical Thought and Praxis, 6(3), 2. https://doi.org/10.31274/jctp-180810-82.

- Becker, S., & Paul, C. (2015). “It didn’t seem like race mattered”: Exploring the implications of service-learning pedagogy for reproducing or challenging color-blind racism. Teaching Sociology, 43(3), 184–200. https://doi.org/10.1177/0092055X15587987.

- Beltrán, C. (2010). The trouble with unity: Latino politics and the creation of identity. Oxford University Press.

- Bollin, G. G. (2007). Preparing teachers for Hispanic immigrant children: A service learning approach. Journal of Latinos and Education, 6(2), 177–189. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348430701305028.

- Boyle-Baise, M. (2007). Learning service: Reading service as text. Reflections, 6(1), 67–85.

- Cahuas, M. C., & Levkoe, C. Z. (2017). Towards a critical service learning in geography education: Exploring challenges and possibilities through testimonio. Journal of Geography in Higher Education, 41(2), 246–263. https://doi.org/10.1080/03098265.2017.1293626.

- Caldwell, W. (2007). Taking Spanish outside the box: A model for integrating service learning into foreign language study. Foreign Language Annals, 40(3), 463–471. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb02870.x.

- Cann, C. N., & McCloskey, E. (2017). The poverty pimpin’ project: How whiteness profits from black and brown bodies in community service programs. Race Ethnicity and Education, 20(1), 72–86. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/13613324.2015.1096769.

- Castañeda, M., & Krupczynski, J. (Eds). (2017). Civic engagement in diverse Latinx communities: Learning from social justice partnerships in action. Peter Lang.

- Castillo-Montoya, M., & Reyes, D. V. (2020). Learning Latinidad: The role of a Latino cultural center service-learning course in Latino identity inquiry and sociopolitical capacity. Journal of Latinos and Education, 19(2), 132–147. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2018.1480374.

- Castillo-Montoya, M., & Torres-Guzmán, M. (2012). Thriving in our identity and in the academy: Latina epistemology as a core resource. Harvard Educational Review, 82(4), 540–558. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.82.4.k483005r768821n5.

- Chen, C., & Mason, D. S. (2019). Making settler colonialism visible in sport management. Journal of Sport Management, 33(5), 379–392. https://doi.org/10.1123/jsm.2018-0243.

- Crenshaw, K. (1991). Mapping the margins: Intersectionality, identity politics, and violence against women of color. Stanford Law Review, 1241–1299.

- Dache, A. (2019). Teaching a transnational ethic of Black Lives Matter: An AfroCubana Americana’s theory of Calle. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 32(9), 1094–1107. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2019.1645906.

- Dache, A., Haywood, J. M., & Mislán, C. (2019). A badge of honor not shame: An AfroLatina theory of Black-imiento for U.S higher education research. The Journal of Negro Education, 88(2), 130–145. https://doi.org/10.7709/jnegroeducation.88.2.0130.

- Delgado Bernal, D. (1998). Using a Chicana feminist epistemology in educational research. Harvard Educational Review, 68(4), 555–583. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.68.4.5wv1034973g22q48.

- Delgado Bernal, D. (2001). Learning and living pedagogies of the home: The mestiza consciousness of Chicana students. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 14(5), 623–639. https://doi.org/10.1080/09518390110059838.

- Delgado Bernal, D., Alemán, E., Jr., & Garavito, A. (2009). Latina/o undergraduate students mentoring Latina/o elementary students: A borderlands analysis of shifting identities and first-year experiences. Harvard Educational Review, 79(4), 560–586. https://doi.org/10.17763/haer.79.4.01107jp4uv648517.

- Espino, M. M. (2016). The value of education and educación: Nurturing Mexican American children’s educational aspirations to the doctorate. Journal of Latinos and Education, 15(2), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2015.1066250.

- Gutiérrez, R. (2012). Embracing Nepantla: Rethinking “knowledge” and its use in mathematics teaching. REDIMAT—Journal of Research in Mathematics Education, 1(1), 29–56.

- Gutiérrez, K. D., Baquedano-López, P., & Tejada, C. (1999). Rethinking diversity: Hybridity and hybrid language practices in the third space. Mind, Culture, and Activity, 6(4), 286–303. https://doi.org/10.1080/10749039909524733.

- Hale, A. (2008). Service learning with Latino communities: Effects on preservice teachers. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 7(1), 54–69. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1538192707310511.

- Haywood, J. M. (2017). ‘Latino spaces have always been the most violent’: Afro-Latino collegians’ perceptions of colorism and Latino intragroup marginalization. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 30(8), 759–782.

- Heldke, L. M. (2004). A Du Boisian proposal for persistently white colleges. The Journal of Speculative Philosophy, 18(3), 224–238. https://doi.org/10.1353/jsp.2004.0022.

- Illich, I. (1968, April 20). To hell with good intentions. [Address]. InterAmerican Student Projects (CIASP), Cuernavaca, Mexico. https://www.uvm.edu/~jashman/CDAE195_ESCI375/To%20Hell%20with%20Good%20Intentions.pdf.

- Irizarry, J. G. (2007). Ethnic and urban intersections in the classroom: Latino students, hybrid identities, and culturally responsive pedagogy. Multicultural Perspectives, 9(3), 21–28. https://doi.org/10.1080/15210960701443599.

- Johnson-Hunter, P., & Risku, M. T. (2003). Paulo Freire’s liberatory education and the problem of service learning. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 2(1), 98–105. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192702238729.

- Kinefuchi, E. (2010). Critical consciousness and critical service-learning at the intersection of the personal and the structural. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 2, 77–93.

- Lareau, A. (2003). Unequal childhoods: Class, race, and family life. University of California Press.

- Loeb, P. R. (2010). Soul of a citizen: Living with conviction in challenging times (Rev. ed.). St. Martin’s Press.

- Maietta, R. C. (2006). State of the art: Integrating software with qualitative analysis. In L. Curry, R. Shield, & T. Wetle (Eds.), Improving aging and public health research: Qualitative and mixed methods (pp. 117–139). Washington, DC: American Public Health Association and the Gerontological Society of America.

- Meraji, S. M., Devarajan, K., Thomad, S., & Donnela, L. (2021, May 12). The Kid Mero talks ‘what it means to be Latino.’ Code Switch. National Public Radio. https://www.npr.org/2021/04/28/991629761/the-kid-mero-talks-what-it-means-to-be-latino.

- McIntosh, P. (1998). White privilege: Unpacking the invisible knapsack. In M. McGoldrick (Ed.), Re-visioning family therapy: Race, culture, and gender in clinical practice (p. 147–152). Guilford Press. (Reprinted from Peace and Freedom, July/August 1989, pp. 10–12; also reprinted in modified form from White privilege and male privilege: A personal account of coming to see correspondences through work in women’s studies, Center Working Paper 189, 1989).

- Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2019). Qualitative data analysis: A methods sourcebook (4th ed.). Sage.

- Mitchell, T. D. (2008). Traditional vs. critical service-learning: Engaging the literature to differentiate two models. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 14(2), 50–65. http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0014.205.

- Mitchell, T. D., & Donahue, D. M. (2009). “I do more service in this class than I ever do at my site”: Paying attention to the reflections of students of color in service-learning: New solutions for sustaining and improving practice. In J. R. Strait & M. Lima (Eds.), The future of service-learning: New solutions for sustaining and improving practice (pp. 172–190). Stylus Publishing.

- Mitchell, T. D., Donahue, D. M., & Young-Law, C. (2012). Service learning as a pedagogy of whiteness. Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(4), 612–629. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2012.715534.

- Noe-Bustamente, L., Mora, L., & Hugo Lopez, M. (2020). About one-in-four U.S. Hispanics have heard of Latinx, but just 3% use it. Hispanic Trends. Pew Research Center. https://www.pewresearch.org/hispanic/2020/08/11/about-one-in-four-u-s-hispanics-have-heard-of-latinx-but-just-3-use-it/.

- Oboler, S. (1995). Ethnic labels, Latino lives: Identity and the politics of (Re)presentation in the United States. Minneapolis, MN: University of Minnesota Press.

- Pak, C.-S. (2018). Linking service-learning with sense of belonging: A culturally relevant pedagogy for heritage students of Spanish. Journal of Hispanic Higher Education, 17(1), 76–95. https://doi.org/10.1177/1538192716630028.

- Paris, D., & Alim, H. S. (2017). Culturally sustaining pedagogies: Teaching and learning for justice in a changing world. Teachers College Press.

- Quiñones, S. (2014). Educated entremundos (between worlds): Exploring the role of diaspora in the lives of Puerto Rican teachers. In R. Rolón-Dow and J. G. Irizarry (Eds.), Diaspora Studies in Education: Toward a Framework for Understanding the Experiences of Transnational Communities. New York: Peter Lang.

- Reese, L., Balzano, S., Gallimore, R., & Goldenberg, C. (1995). The concept of educación: Latino family values and American schooling. International Journal of Educational Research, 23(1), 57–81. https://doi.org/10.1016/0883-0355(95)93535-4.

- Rondini, A. C. (2015). Observations of critical consciousness development in the context of service learning. Teaching Sociology, 43(2), 137–145. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0092055X15573028.

- Rosenberger, C. (2000). Beyond empathy: Developing critical consciousness through service learning. In C. R. O’Grady (Ed.), Integrating service learning and multicultural education in colleges and universities (pp. 23–43). Erlbaum.

- Santiago-Ortiz, A. (2019). From critical to decolonizing service-learning: Limits and possibilities of social justice–based approaches to community service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 25(1), 43–54. https://doi.org/10.3998/mjcsloa.3239521.0025.104.

- Sperling, R. (2007). Service-learning as a method of teaching multiculturalism to white college students. Journal of Latinos and Education, 6(4), 309–322. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348430701473454.

- Tatum, B. D. (1997). “Why are all the Black kids sitting together in the cafeteria?” and other conversations about race. Basic Books.

- Torre, M. E., & Ayala, J. (2009). Envisioning participatory action research entremundos. Feminism & Psychology, 19(3), 387–393. https://doi.org/10.1177/0959353509105630.

- Vargas, L. C., & Erba, J. (2017). Cultural competence development, critical service learning, and Latino/a youth empowerment: A qualitative case study. Journal of Latinos and Education, 16(3), 203–216. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348431.2016.1229614.

- Winans-Solis, J. (2014). Reclaiming power and identity: Marginalized students’ experiences of service-learning. Equity & Excellence in Education, 47(4), 604–621. https://doi.org/10.1080/10665684.2014.959267.

- Yosso, T. J. (2005). Whose culture has capital? A critical race theory discussion of community cultural wealth. Race Ethnicity and Education, 8(1), 69–91. https://doi.org/10.1080/1361332052000341006.