Investigating the Overlapping Experiences and Impacts of Service-Learning: Juxtaposing Perspectives of Students, Faculty, and Community Partners

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

As service-learning and community-based learning proliferate in higher education, increased attention has been directed toward gathering evidence of their impacts. While the bulk of the literature has focused on student outcomes, little work has been done to examine how the perspectives of stakeholder groups overlap and intersect. This study uses an exploratory qualitative design to examine the experiences of service-learning students, faculty, and community partners at a four-year public university, which revealed five key themes: the time-intensive nature of service-learning, the added value provided by the service-learning faculty member, the additional benefits created by service-learning connections, the unintended opportunities for discovery of self and others, and the impacts of the liminal space of service-learning transcending traditional academic boundaries. Implications of the study reveal the importance of institutional support and coordination to maximize impacts on stakeholders, as well as the need for further study of overlapping stakeholder perspectives in multiple contexts.

Service-learning is a teaching and learning strategy that applies students’ classroom learning to meet a meaningful community need, building upon John Dewey’s (1938) call for a pedagogy grounded in experience that prepares students to be active members of a democratic society. Scholarship since the 1990s has recognized the rapid expansion of service-learning programs in higher education and the need for rigorous, structured assessment of the outcomes and impacts of such programs (Chupp & Joseph, 2010; Driscoll, Holland, Gelmon, & Kerrigan, 1996; Eyler, Giles, & Braxton, 1997). The past decade and a half in particular have seen the production of service-learning scholarship that answers this call with unprecedented breadth, including work by Abes, Jackson, and Jones (2002) to understand faculty motivations; Celio, Durlak, and Dymnicki’s (2011) meta-analysis of student impacts; Kilgo, Ezell Sheets, and Pascarella’s (2015) examination of longitudinal data on high-impact educational practices from the Wabash National Study of Liberal Arts Education; and Keen and Hall’s (2009) longitudinal study of students engaged in co-curricular service-learning through 23 liberal arts colleges’ Bonner Scholar Programs.

This study reports assessment findings from a four-year public university located in the southern United States, with a service-learning program that officially launched in 2013. The program assessment plan established program outcomes and measures for students, faculty, and community partners; this research provides results of focus groups conducted with all three stakeholder groups in February and March 2016. Although several service-learning faculty members at the institution have conducted research related to their own service-learning courses and pedagogy, a program-wide study was needed to report findings on outcomes and impacts on the students, faculty, and community. The primary purpose of this research, then, was to identify the outcomes of the university’s service-learning program by studying the impacts on students, faculty, and community partner organizations. The following research questions were addressed: (a) How has service-learning impacted student participants' academic performance and understanding of their discipline, cultural awareness, civic responsibility and community, and their skills in collaboration; (b) How has service-learning impacted faculty members' teaching practice, teaching philosophy, and commitment to civic engagement and community; and (c) How has service-learning impacted nonprofit community partner organizations' ability to fulfill their service missions?

Literature Review

The review of literature examines the impacts of service-learning on students, faculty, and community partners. Overall, research on student impacts far exceeds that on faculty and community partner impacts.

Student Impacts

With the implementation of service-learning widespread in higher education, evidence reveals a variety of impacts. As numerous researchers have observed (e.g., Driscoll, 2000; Vernon & Ward, 1999), the study of service-learning outcomes has focused predominantly, and perhaps appropriately, on students. Service-learning has been found to have a positive impact on academic achievement (Celio et al., 2011; Strange, 2000), critical thinking and writing skills (Vogelgesang & Astin, 2000), and attitudes toward school and learning (Celio et al., 2011). Students who participate in service-learning are better able to apply course concepts to new situations (Kendrick, 1996) and demonstrate a greater understanding of career decision-making (Coulter-Kern, Coulter-Kern, Schenkel, Walker, & Fogel, 2013), improved leadership skills (Groh, Stallwood, & Daniels, 2011), and a greater desire for their career to have a social impact (Seider, Rabinowicz, & Gillmor, 2011).

Eyler et al. (1997) suggested the learning in service-learning improves the quality of the service, and in so doing, contributes to the development of civic responsibility and commitment. Indeed, civic learning outcomes, such as civic consciousness (Lovat & Clement, 2016), community efficacy (Bernacki & Jaeger, 2008; Sanders, Van Oss, & McGeary, 2016), social responsibility (Kendrick, 1996), a social-justice orientation (Groh et al., 2011), and an expressed commitment to activism (Vogelgesang & Astin, 2000) are often positioned in the literature as equally important to academic outcomes. Personal and social outcomes include improved self-concept (Celio et al., 2011), self-awareness (Furze, Black, Peck, & Jensen, 2011), cultural awareness (Desmond, Stahl, & Graham, 2011), intercultural effectiveness (Kilgo et al., 2015), adaptability (Desmond et al., 2011; Furze et al., 2011), social skills (Celio et al., 2011), more positive attitudes toward people with disabilities (Wozencraft, Pate, & Griffiths, 2014), and a commitment to promoting racial understanding (Vogelgesang & Astin, 2000). Other scholars have identified trends toward a focus on public service in particular disciplines and how students’ future professions can impact society, including engineering (Carberry, Lee, & Swan, 2013), physical therapy (Furze et al., 2011), and health care (McMenamin, McGrath, Cantillon, & MacFarlane, 2014).

Recent scholarship has frequently turned to addressing nuances such as which service-learning practices are most effective, including giving students choices (Celio et al., 2011) and structuring reflections to maximize students’ personal growth and self-efficacy (Sanders et al., 2016). Rockquemore and Harwell Schaffer (2000) have argued that, while ample evidence exists that students learn from service-learning experiences, a better understanding is needed of how they learn, and their tracking of students’ cognitive processes through stages of shock, normalization, and engagement in reflection journals represents one attempt to achieve such understanding. Knapp, Fisher, and Levesque-Bristol (2010) further examined how service-learning achieves civic learning outcomes, focusing on how service-learning builds both students’ self-efficacy and social empowerment, leading to stronger levels of civic engagement. Qualitative methods have proven particularly useful in these efforts to dig deeper into how learning occurs and attitudes change. As Paoletti, Segal, and Totino (2007) observed in their study of student portfolios to assess students’ growth over time, students may be disingenuous or inaccurate in assessing their own attitudes and skills before a community engagement experience but are able to recognize these inaccuracies and communicate changes after the experience.

Looking to the institution as a mechanism for achieving student outcomes, Billings and Terkla (2014) found that institutional culture influences both students’ values and their actions. Similarly, focusing on the interaction between the student and the higher education institution, Lockeman and Pelco (2013) reported that despite being more likely to belong to racial minority and low-income groups with historically lower graduation rates, service-learning students graduated at much higher rates than those not enrolled in service-learning courses.

Alongside the large body of research reflecting positive impacts of service-learning on students, numerous other studies have shown mixed or negative results, particularly related to moral and ethical development (Bernacki & Jaeger, 2008; Boyle, 2007; Chupp & Joseph, 2010; Hess, Lanig, & Vaughan, 2007). Desmond et al. (2011) found service-learning experiences have the potential to perpetuate negative stereotypes, reinforce privilege, and support institutionalized poverty by leading students to believe direct service to individuals can substitute for social action. Indeed, as Pompa (2002) has argued, traditional service-learning and community service often create a patronizing relationship between those doing the service and those receiving it. Mitchell’s work (2007, 2015) on critical service-learning has offered multiple approaches to mitigate these negative effects by facilitating deeper thinking related to social justice among students in relation to civic identity development. Overall, the research on student impacts reports more positive than negative effects with a need for further research on how to mitigate potentially negative impacts.

Faculty Impacts

Although research on service-learning faculty impacts has been underdeveloped relative to research on students, notable findings include Driscoll’s (2000) observation that “faculty are both influential with, and influenced by, service-learning” at institutions that follow a course-driven model of academic service-learning (p. 35). The impacts that teaching with service-learning had on faculty in Driscoll’s study included changing from a traditional “banking” model to more constructivist or learner-centered approaches and faculty being able to combine their academic roles with a desire to “make a difference” (p. 38). Also in the area of faculty impacts, Pribbenow (2005) investigated whether the use of service-learning as a pedagogical innovation affected the teaching and learning process, revealing outcomes such as more meaningful engagement in and commitment to teaching, deeper faculty-student connections and better understanding of students, changes in classroom pedagogical practices, improved communication of theoretical concepts, and greater connection to other faculty and to the institution. Overall, faculty are enriched in a number of ways by engaging in service-learning.

Community Impacts

Arguably, the area most in need of further investigation is that of community impacts. As Ferrari and Worrall (2000) observed, although community partners tend to report positively on students’ service and work skills, a disconnect exists between students’ perceptions of the difference they make and the assessment by community partners. Sandy and Holland’s (2006) study of community partner perspectives found community partners valued nurturing the partnership, communicating among partners, understanding partner perspectives, co-planning of service-learning projects, and establishing accountability for project outcomes. They also offered the key insight that community partners share a profound dedication to educating college students, challenging the assumption that university and community partners begin with drastically different goals and priorities. Even so, as Schmidt and Robby (2002) have noted, research on community partners has focused largely on evaluations by supervisors rather than effects of service. Just as research on student outcomes has revealed some mixed results, earnest interest in community impacts requires the willingness to investigate potential harm as well as benefits to community partners. To this end, Srinivas, Meenan, Drogin, and DePrince (2015) used community partners’ perceptions to measure the benefits and costs of community-university partnerships, creating an instrument for measuring community partner perceptions that will undoubtedly prove highly useful for assessing both positive and negative impact on the community partners that are meant to benefit from service-learning projects and partnerships.

Investigating Overlapping Experiences

Although students, faculty, and the community are purported to be equal partners in the service-learning enterprise, only rarely are the impacts of service-learning on students, faculty, and community partners considered together in a holistic analysis. Limited examples of such scholarship include Chupp and Joseph’s (2010) model for focusing on and measuring the impacts of service-learning on the student, university, and community, and McMenamin, McGrath, and D’Eath’s (2010) study of the impacts on nursing service-learning students, faculty, and communities). If instilling the values associated with active citizenship is indeed an essential role of higher education as Billings and Terkla have argued (2014), more study of the interactions and overlaps between how students, faculty, and community partners experience community engagement and view the institution’s responsibility to the community is needed.

Method

In the spring of 2013, our university’s administration approved a proposal to begin a university-wide service-learning program consistent with the university’s mission and core values. The program includes a professional staff position and university advisory committee chaired by a faculty liaison and offers an annual fellowship program for training service-learning faculty. The university adopted the National Service-Learning Clearinghouse’s definition of service-learning as a teaching and learning strategy that integrates meaningful community service with instruction and reflection to enrich the learning experience, teach civic responsibility, and strengthen communities. Therefore, a course may be designated as a service-learning course if it accomplishes all of the following: (a) involves collaboration between a faculty member and a community organization that meets a community need, (b) the service activity serves the course objectives by helping students to grasp the knowledge and skills essential to the course, and (c) students participate in structured reflection.

This study, approved by the university’s institutional review board (#15-227) in fall 2015 and implemented in spring 2016, utilized an exploratory qualitative design to discover the impact of the phenomenological experiences of constituents of the university’s service-learning program. We employed a qualitative approach to allow for the collection of information about the how and why of reported outcomes, and focus groups offered an opportunity to generate rich, complex, nuanced, and potentially contradictory accounts of how the three groups of participants applied meaning to their participation in service-learning. Due to the complexity of institutionalizing service-learning as a teaching and learning pedagogy, we conducted separate focus groups to gather qualitative data about the impacts of service-learning from each participant group (Kamberelis & Dimitriadis, 2011).

We conducted seven focus groups consisting of participants recruited from the population of students, faculty, and community partners who engaged in officially designated service-learning courses at the university in the semester prior to the focus group. The sample comprised six students, seven faculty members, and four community partners. Participants represented three undergraduate and one graduate program. Disciplines included health sciences, public relations, and occupational therapy. Five of the six student participants were earning an undergraduate degree. Students reported having enrolled in one to three service-learning courses while at the university, with a mean of 1.8 courses per student. Five students provided direct service, and one student provided indirect service for a nonprofit agency. Students reported completing between 12 and 100 hours of course-related service.

Faculty participants represented seven disciplines: community and economic development, health sciences, history, honors interdisciplinary studies, occupational therapy, political science, and public relations. Faculty reported between one and 10 years of experience in applying the pedagogy of service-learning in their courses, with a mean of 4.4 years of experience. Two faculty reported incorporating service-learning in more than one course each year, and two indicated teaching more than one service-learning course each semester. Four faculty utilized indirect service-learning, and five incorporated direct service-learning, with two faculty indicating that they used both direct and indirect service-learning.

Of the four community partner participants, three indicated experience with service-learning and one was new to service-learning. The number of years of experience by these three partners ranged from two to eight years, with a mean of 4.3 years. All three had experienced partnerships in which students provided direct services to nonprofit clients.

According to Kamberelis and Dimitriadis (2011), focus groups lead to pedagogical results through actively engaging participants to collectively build a higher level of understanding. Kamberelis and Dimitriadis proposed a prism to symbolically represent the way focus group research reflects “the intersection of pedagogy, activism, and interpretive inquiry [research]” (p. 545), with each of these angles refracting and reflecting the data in a unique way. Activism follows from pedagogy when the group addresses how conditions of existence are transformed by stakeholders. Finally, interpretive inquiry, or the research aspect of focus groups, leads to the thick description of participants’ understandings and experiences.

Although many qualitative analytical approaches can be used to discover the subjective experiences of participants and the meanings that they ascribe to their experiences, we incorporated best practices from a variety of sources (Denzin & Lincoln, 2011; Miles & Huberman, 1994; Miller & Salkind, 2002; and Patton, 2002). Suggestions for analysis outlined by Creswell and Maietta (2002) were incorporated into the procedures implemented, including the use of summary sheets for each group, coding, memoing, and illustrations. Specifically, memoing was used as a “rapid way of capturing thoughts that occur in data collection, data reduction, data display, conclusion drawing, conclusion testing, and final reporting” (Creswell & Maietta, 2002, p. 73). We utilized epoche and bracketing, or viewing data independently of literature or opinions of others, during the early analysis to conduct an emic analysis, that is, from participants’ perspectives (Patton, 2002). Later in the analysis, we analyzed the data from an etic, or researcher, perspective.

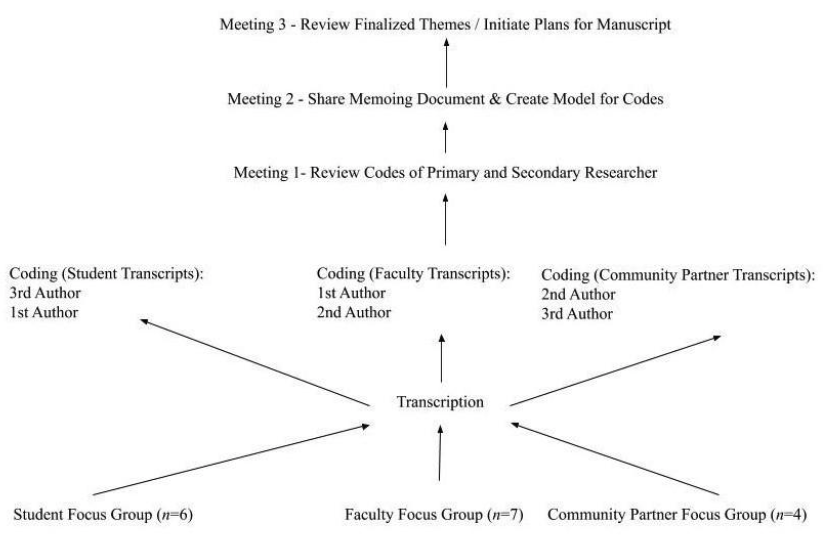

A modification of Braun and Clarke’s (2006) six-step process was employed in the analysis of data (Figure 1). We completed three steps independently: familiarizing ourselves with the data, producing initial codes, and merging similar codes into categories. One author served as the primary reader for each transcript, while a second author conducted a secondary review of the transcript to confirm codes and identify blind spots of the first reader (Creswell & Maietta, 2002). The remaining steps were completed through a series of meetings in which all authors discussed and finalized codes for each group and identified emergent themes overlapping groups. After the first meeting, we collaborated to create memos to elaborate on the emergent themes. Each author added relevant illustrations for each thematic memo. As the analysis proceeded, we generated propositions to connect sets of statements, reflect findings, and draw conclusions (Creswell & Maietta, 2002). In the final step, we collaborated to produce the research report.

Results

The themes generated during the data analysis appear in this section. The process of coding and memoing resulted in five themes across stakeholders: the time-intensive nature of service-learning, the added value provided by the service-learning faculty member, the additional benefits created by service-learning connections, the unintended opportunities for discovery of self and others, and the impacts of service-learning as a liminal space that transcends traditional academic boundaries.

Counting the Costs: Service-Learning Is Time Intensive

Faculty, students, and community partners identified time as a major factor associated with planning and implementing service-learning. Students expressed challenges in balancing the large out-of-class time commitment of service-learning with coursework and family responsibilities. Students described service-learning as more time intensive than a typical class, saying that it “definitely ... felt like more than one class”; referenced other resources, such as a functioning car and gas, required to complete the service-learning project; and recognized the opportunity cost of a service-learning project competing with a paid job or internship. As one nontraditional student noted, “I think the biggest negative could possibly be the time constraints. Because as a nontraditional student, my day doesn't end with my last class. I have kids I have to go home and take care of and groceries to buy and laundry to do, and sometimes there's just not enough time.”

Faculty members also expressed sensitivity to such experiences, with one faculty member sharing a story of a student “working 50 hours a week managing a restaurant and in school full-time.” Faculty also identified time as a challenge for them in designing and implementing service-learning projects. The time required to develop and implement a quality service-learning course was identified as an obstacle, and other course content must be eliminated to make time to include service-learning. Faculty members indicated service-learning is more time consuming than lecturing. Some faculty struggled to find balance in their courses and even their own lives, one participant describing service-learning as “a lot of planning” and another stating that community partnerships “take time” to set up.

Community partners recognized that time constraints on overloaded faculty and students can lead to possible limitations in the quality of the service-learning process and product. One community partner observed, “Students and the faculty members were stretched a little ... [and] that seems to be ... an impediment to a really strong deliverable project.” Another partner remarked that faculty “need to find a way to balance [course content and service-learning] and not overwhelm either students or faculty.” Comparing faculty, student, and community partner investment in partnerships, however, one community partner observed “a mismatch in emotional investment,” going on to explain, “sometimes it will get frustrating if you feel like you’re wasting your time and ... they’re not really buying into what they’re doing.” Although each stakeholder group clearly understood the investment of their own time that service-learning required, students and faculty demonstrated limited understanding of how engaging in service-learning affected community partners’ time. While one faculty participant noted that “[community partners] just can’t do it all; they just don’t have enough manpower and time to do everything they need to do without breaking their backs and their budget,” the faculty member did not acknowledge that this lack of time might constitute a challenge of service-learning for the community partner. Instead, the faculty member felt that students could alleviate the problem by providing “some safe, free labor” for the nonprofit community partner.

Despite significant time requirements for implementing service-learning, all participants saw the benefits of getting students out of the textbooks and engaging them in real-world experiences as worth the time and effort. Overall, teaching and learning outcomes resulting from the outlay of time by students, faculty, and community partners included real-world learning, fresh perspectives, opportunities to do good for others, more relevant teaching, application of theory to practice, expansion of students’ worldviews, opportunities for faculty members to leave the ivory tower and for community partners to enter it, and opportunities for students to be evaluated by authentic standards. In essence, while not all stakeholders were adept at understanding one another’s time constraints, all perceived the benefits of service-learning to merit the investment of time required.

The Service-Learning Faculty Member as Leader Adds Value

A second theme that emerged from the data focuses on the role of the faculty member in the impact of service-learning; both students and community partners relied on the faculty member to take the leadership role. As one community partner stated, “It is really beneficial when a service-learning group is directed by the professor.” Community partner participants conveyed they wanted more “formalized” ways to get information from faculty members and students, along with “some type of [introduction] to what this is all about and how it works, and then a communication strategy or plan.” Furthermore, community partner participants expressed confusion about what distinguishes service-learning from other types of experiential learning and community service. Partners raised several questions during the focus groups regarding how service-learning works at the university, asking, “What's the difference between this [service-learning] versus internships versus just normal day-to-day individual volunteer opportunities?” and “Is it any different than any type of credit for a regular class?” Community partner participants clearly looked to the faculty member as a source of guidance not just for students but also for themselves in understanding the service-learning project and their role in it.

Students similarly expressed a desire for the faculty member to establish the expectations of both students and community partners. One student participant shared, “I really wasn’t sure why we were doing this [service-learning]. And so I think a drawback or something that can be improved on would definitely be stopping and explaining. I know that sounds simple, but stopping and really explaining service-learning at the very beginning.” Another student participant recognized the value that the course planning done by faculty members adds, noting of a particular service-learning course, “Our course has just, I think, been perfected over the course of the years ... there’s reflection at each and every step of the way, there’s accountability ... every component of it just fits perfectly.”

Faculty members, however, viewed themselves as enabling rather than directing learning. One faculty member acknowledged this does not happen automatically, rather, “I help to facilitate that [learning] in some way through service-learning partnerships.” One faculty participant acknowledged that the faculty member must take responsibility for managing the service-learning workload, admitting, “For me, there was a learning curve, and I realized I had too many assignments ... to try to manage their scope of work as well as my own scope of work. And so I had to scale back.” Even while claiming a more facilitative role as instructors of service-learning courses, faculty expressed feeling responsible for the quality of student work, saying, “In terms of the quality, it makes me feel like, gosh, what should I have done better, you know? And the drawback for me is feeling kind of inadequate as a professor because I couldn’t get the students up to that level.”

Student and community partner participants both needed help understanding service-learning, either recalling questions that they had at the beginning of a project or, in the case of multiple community partners, asking clarifying questions over the course of the focus group. Ultimately, while both students and community partners looked to faculty for leadership of the service-learning experience, faculty demonstrated some ambivalence about their responsibility for fostering high-quality service-learning experiences for all involved.

Win-Win-Win: Service-Learning Creates Connections and Additional Benefits

Each group of stakeholders articulated specific benefits of participation in service-learning; students appreciated the opportunity to explore what lies ahead in their future careers, faculty members felt a renewed sense of purpose, and community partners appreciated the fresh ideas and skill sets available to them through service-learning. In addition to these direct benefits, service-learning partnerships also created connections between stakeholder groups through which additional benefits were made possible, including access to new networks and community relationships.

The intersection of giving and receiving was evident among all stakeholder groups. For students, participating in their community “feels good” and provides opportunities for “embracing their profession” and “becoming better teammates.” Students particularly focused on how service-learning prepared them with both the skills and the attitudes to enter a profession; as one student recalled, “I really didn’t love, love, love [my major] until I did this service-learning project with the community, because I was completely immersed in it.”

Service-learning encouraged students to view themselves as members not only of a professional community but of a local community as well. One student recalled learning that “We [students] belong ... we are part of the community. It doesn’t matter that you’re a student and you’re from [out of state]. You’re here, and you’re providing something to this community.” As another student noted, “Definitely afterwards I was a lot more interested in connecting with the community.” One student argued for expanded implementation of service-learning at the university, musing, “Even if someone does it and hates it, then it’s just one course they had to take. But if there’s a possibility that that passion will catch fire within them and they’re serving the community for years and years after that ...” suggesting that an important function of service-learning for students was to instill a sense of commitment as a community member.

Faculty described service-learning as a useful strategy for teaching professional skills such as problem-solving and teamwork as well as a pedagogy that “keeps things fresh and new” in course design. Faculty were interested in instilling a sense of community commitment in students, but similarly to students, also enjoyed the feeling of making a meaningful contribution; as one faculty member explained, “I’m getting to help things and places that I care about, too.” Faculty perceived membership in new communities and, more specifically, the opportunity to work beyond the boundaries present within the academic community as a benefit as well. As one faculty member explained, “I’m still trying to figure out my place in the academy ... so it connects me to the community and the real world, gets me out of the academic bubble.” Another echoed this perspective, noting, “it does get me out of the sort of academic silo, and get me into the community and having to build those relationships.” The connections that faculty created in their service-learning partnerships in fact offered many of the same benefits that they touted for students, including the opportunity to apply one’s discipline in the “real world” and a sense of purpose.

Community partners identified students’ skill sets as “a tremendous advantage” to nonprofits, but they were also just as emphatic about the value of the new networks that service-learning created for them. Community partner participants recognized the potential of students to serve as ambassadors to a younger audience, arguing, “The biggest thing that they bring...[is] just the awareness that they spread about our organization and what we’re doing.” Furthermore, community partners identified service-learning partnerships as opening the door to more opportunities, explaining, “The community didn’t just welcome the students, but the university welcomed the community in.” All three stakeholder groups observed that networking opportunities and a sense of community were additional benefits of participation in service-learning.

Service-Learning Creates Opportunities for Discovery of Self and Others

Student participants believed service-learning helped them to discover new areas of interest within their chosen professions, revealed aspects of what their careers might entail, and provided much-needed preparation and confidence. As one student who had been working on a service-learning project related to obesity explained, “While we were in the class, [our state] was named the most obese state in America. I mean, that just really impacts the [class]—what I’m doing is validated, it’s a real issue, and I’m making a difference.” Speaking about how service-learning increased the students’ confidence in their own professional skills, another participant concluded, “I feel like I’m capable after graduation of achieving some of this stuff, because you gain skills that you don’t really think about in the classroom. So I think for sure I was a lot more confident afterwards.”

Student participants also described an evolving understanding of their communities and of people unlike themselves. As one student asserted the service-learning project was “just another example of inspiring you and convicting you ... just to do better for your community.” Although exposure to diversity was not always an explicit learning outcome, students identified growth in their understanding of others as one result of their service-learning experiences. One participant claimed service-learning helps “put our feet in the shoes of other people and understand what appeals to them, how to reach them, so it definitely encourages us to think more diverse[ly] about other people and other outlooks.” For students, service-learning provided far more opportunities for discovery within and without than they anticipated.

Faculty participants also noted the opportunities for students to engage in a process of discovery about themselves and their communities. One participant claimed that service-learning “teaches them a lot about themselves,” while another reflected, “It does raise their awareness of local issues, of things going on in the community they live in that they just never really knew about or understood.” Additionally, some faculty participants observed how they themselves had discovered something new about themselves while using service-learning pedagogy. As one faculty member shared, “I started off doing something more direct, I probably shifted the balance of what I was doing more to advocacy in the middle part, and I’ve shifted again more towards research as I clarify for myself what I want the last part of my career to be as a teacher.” Using service-learning pedagogy crystalized the professional goals of faculty as well as students.

Community partners articulated a different perspective on students’ self-discovery through service-learning, emphasizing the need for the university to graduate students with a certain mindset or commitment to the community as a whole. As one community partner explained, “It’s almost like service-learning represents not simply the imparting with the university classroom the facts, but it’s helping the learner feel the facts that they are learning,” continuing, “I think these folks need to be graduating with more heart than they often graduate with.” In more concrete terms, other community partners hoped that students who participated in service-learning would become more connected to the local community and have a greater desire to remain after graduation. Overall, community partners hoped that students’ self-discovery through service-learning would lead to a lasting passion for and dedication to their community.

Service-Learning as Liminal Space

A final theme that emerged from the data was that service-learning represents a space of possibility, potential, and transition that can be termed a “liminal space” outside of traditional academic boundaries (Turner, 1969; for another discussion of liminality and service-learning, see Henry, 2005). Participants identified service-learning as both a risk-taking endeavor and an area of great potential growth for individuals and the university.

From the faculty perspective, service-learning requires surrendering some control over the learning experience; yet service-learning also fails without structure. On one side of this carefully balanced scale, a faculty member described the challenge of “figuring out what leaves class when you add service-learning in,” noting emphatically that “something has to go.” Whether letting go of some course content or relying on fewer assignments to scaffold the service-learning experience, faculty members noted the importance of entering the service-learning experience with a flexible course design. Faculty members articulated the importance of service-learning as a space in which students had the opportunity to confront and attempt to solve “real-world” problems, which are inherently messier than the problems students encounter in the classroom. Giving up control was not easy for faculty participants. As one faculty participant reflected, “I enjoy the moments of discovery, but I also have a lot more anxiety and sleepless nights and ulcers and worry, and I don’t have much control, and I love control. It’s probably good for me to let go of control, but it’s not something I enjoy particularly.”

Students similarly described initial anxiety about leaving their comfort zones, using words like “hectic” to describe their experiences and “intimidated” and “nervous” to describe their feelings. As one student explained her initial feeling of insecurity, “We had no idea what we were doing, we were kind of just going with the flow, and like, okay, I hope this is correct.” Yet this initial anxiety seems to be precisely what enables the service-learning experience to have a positive result for students. As another student recalled, “I mean, the constant setting up of meetings and trying to get information and putting it all together, and then at the very end actually going to this group and saying, ‘Okay, what do you think?’ was very hectic. But energizing as well.” Another student described the growth she experienced as a result of service-learning and further anticipated this growth would continue, noting, “I feel confident because of having past experience, but I know there's still more for me to learn.”

Having successfully navigated the service-learning experience, students were able to look back and recognize the value of experiencing that uncertainty and growth. Students used words like “practice,” “application,” and comparison with an “on-the-job training session” to describe their service-learning experiences. As one student put it, “[Service-learning] allowed us to hone in on what we're good at and try things out without any serious repercussions.” Another student referred to her service-learning experience as a “baby step of my career” where “[you can] start to practice what you're learning in class and with real-life people in front of you.” While comments like these reveal the value students placed on having a space in which to perform a professional identity for the first time, they are also troubling in that they reveal students’ failure to understand (or at the very least to articulate) the potential risks of the service-learning experience. Students may not enter this liminal space fully grasping their potential to cause harm.

Indeed, while community partners generally expressed less anxiety and uncertainty than faculty and student participants, they observed how students’ lack of knowledge of or incorrect assumptions about their organizations’ work presented a risk. As one community partner explained, a challenge of service-learning is “getting over the mindset of what [students] think something is.” Preconceptions prevent learning opportunities for students, so community partners were eager to transform preconceptions into unknowns. By definition, a liminal space offers both opportunities and risks for all involved.

Discussion

Like the original research questions that structured this study, implications for the practice of and research related to service-learning exist for all three stakeholder groups: students, faculty, and community partners.

Implications for Students

The research question related to students asked, “How has service-learning impacted student participants’ academic performance and understanding of their discipline, cultural awareness, civic responsibility and community, and their skills in collaboration?” Data from this study demonstrate students perceive benefits consistent with previous research findings, including growth in understanding of their disciplines and increased comfort level in entering their chosen professions (Strange, 2000); improved self-concept, social skills, and teamwork (Celio et al., 2011); and improvements in critical thinking (Desmond et al., 2011; Furze et al., 2011; Vogelgesang & Astin, 2000). Furthermore, students experienced increased awareness of self, others, and the community through service-learning projects, with participants reporting improved cultural awareness and civic responsibility. This study confirmed Seider et al.’s (2011) assertion that students have a desire to make a social impact through their careers. While non-traditional students acknowledged challenges in balancing their roles of student, employee, and family member, they did not resist participation in service-learning as Kelly (2013) described among adult learners. In fact, the time intensity all stakeholder groups identified in service-learning may be at the core of its pedagogical success for students; as Kilgo et al. (2015) observed more broadly, “High-impact practices are effective because they require dedication and a substantial time commitment from students” (p. 511), among other factors. Conclusively, students expressed two strong needs to navigate service-learning successfully: greater clarification of the expectations and time requirements involved in a service-learning project and help navigating the complexities of discovery of self and others. Thus, requirements should be expressed early and clarified regularly, and critical reflection should be used to help students process their experiences and mitigate potentially damaging conclusions.

Implications for Faculty

The research question related to faculty asked, “How has service-learning impacted faculty members’ teaching practice, teaching philosophy, and commitment to civic engagement and community?” The literature has consistently identified time as a significant factor related to faculty members’ incorporation of service-learning (Abes et al., 2002; Kilgo et al., 2015), which this study confirmed. Unlike previous research, this study’s faculty participants did not suggest time was a deterrent. This study echoed previous findings that faculty members invested their time in service-learning first and foremost to achieve optimal student outcomes but also to benefit the community (Abes et al., 2002; Driscoll, 2000). As Chupp and Joseph (2010) found, participants also expressed a desire for service-learning to be recognized in promotion and tenure criteria. Chupp and Joseph further reported a need for workload reductions and administrative support for the implementation of service-learning. Clearly, this study’s participants believe service-learning is transformative in their teaching philosophy and practice, indicating dedication to continue service-learning despite the time demands and risks involved. The data strongly support the need for faculty preparation and willingness to take on a leadership role in setting up the foundation for successful partnership. Faculty members need to scale projects to match the realities of all three stakeholder groups, as well as preparing and coaching students and community partners.

Implications for Community Partners

The research question related to community partners asked, “How has service-learning impacted nonprofit community partner organizations’ ability to fulfill their service missions?” Community partners valued the relationships with students, faculty members, and the university (Sandy & Holland, 2006), particularly the energy and current knowledge and skills college students contribute. This study’s data confirm Vernon and Ward’s (1999) finding that community partners found difficulty distinguishing between different types of service, suggesting the need for increased institutional effort to educate partners and faculty attention to establish clear expectations for partnerships. The lack of long-term commitment, short duration of most projects, and need to work around the semester schedule were also challenges. This study also confirms Ferrari and Worrall’s (2000) finding that community partners are sometimes dissatisfied with the quality of students’ work and confirms the need to explore the mismatch between students’ and community partners’ perceptions of students’ impact. Indeed, many of the benefits community partners in this study perceived were unrelated to the quality of students’ work, including factors such as increased awareness of their organizations among the student body and access to additional university resources.

Limitations and Future Directions

Although this study revealed numerous key findings related to the impacts of service-learning on students, faculty, and community partners, findings generated by qualitative methods have limited generalizability. Furthermore, the focus group methodology contains inherent limitations in the type of data generated. It is also possible participants may have been unwilling to articulate some perspectives or experiences, particularly negative ones, in a group setting. Future research employing a mixed methods design could mitigate this potential limitation. Student participants in particular were limited in the impacts that they could articulate and when discussing positive impacts, focused primarily on anticipated professional benefits. Future research directions to address these limitations include a longitudinal study with follow-up interviews and surveys in addition to continuing to hold focus groups for all three stakeholder groups. Although focus groups that include a mix of stakeholders are not typically recommended for data collection, we also believe providing opportunities for facilitated interactive discussion between members of different stakeholder groups could result in increased understanding of the impacts and shortcomings of service-learning pedagogy.

Conclusions

As Billings and Terkla (2014) asserted, “Instead of focusing on individual events in a vacuum, higher education institutions need to craft purposeful plans to integrate students’ experience toward the development of public citizens and leaders” (p. 52). We would add that a truly purposeful plan must include an understanding not only of the separate outcomes experienced by each group of service-learning stakeholders but also of how these outcomes confirm, reinforce, and perhaps even compete with one another. This study and a growing body of research indicate that the numerous benefits of service-learning outweigh the challenges. Although the benefits of service-learning for students, faculty, and community partners are clear, they are not guaranteed, nor are they necessarily equal. Higher education institutions and service-learning practitioners still stand to benefit from a deeper understanding of how and why service-learning produces the impacts it does. This study emphasizes that stakeholders must not only be actively involved in partnership building but also appreciate the ambiguity, uncertainty, and delicate balancing act at the heart of a successful partnership. As anchor institutions, colleges and universities whose missions espouse a commitment to community engagement and civic responsibility play a key role in supporting all stakeholders in this process. The structure and culture of most universities works against collaboration, and the proactive efforts of academic leaders are needed to address community needs collaboratively.

References

- Abes, E. S., Jackson, G., & Jones, S. R. (2002). Factors that motivate and deter faculty use of service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 9(1), 5–17.

- Bernacki, M. L., & Jaeger, E. (2008). Exploring the impact of service-learning on moral development and moral orientation. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 14(2), 5–15.

- Billings, M. S., & Terkla, D. G. (2014). The impact of the campus culture on students’ civic activities, values, and beliefs. New Directions for Institutional Research, 162, 43–53.

- Boyle, M.-E. (2007). Learning to neighbor? Service-learning in context. Journal of Academic Ethics, 5(1), 85–104.

- Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3(2), 77–101.

- Carberry, A., Lee, H.-S., & Swan, C. (2013). Student perceptions of engineering service experiences as a source of learning technical and professional skills. International Journal for Service Learning in Engineering, 8(1), 1–17.

- Celio, C. I., Durlak, J., & Dymnicki, A. (2011). A meta-analysis of the impact of service-learning on students. Journal of Experiential Education, 34(2), 164–181.

- Chupp, M. G., & Joseph, M. L. (2010). Getting the most out of service learning: Maximizing student, university and community impact. Journal of Community Practice, 18(2/3), 190–212.

- Coulter-Kern, R. G., Coulter-Kern, P. E., Schenkel, A. A., Walker, D. R., & Fogle, K. L. (2013). Improving student’s understanding of career decision-making through service learning. College Student Journal, 47(2), 306–311.

- Creswell, J. W., & Maietta, R. C. (2002). Qualitative research. In D. C. Miller & N. J. Salkind (Eds.), Handbook of research design and social measurement (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Denzin, N. K., & Lincoln, Y. S. (Eds.). (2011). The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Desmond, K. J., Stahl, S. A., & Graham, M. A. (2011). Combining service learning and diversity education. Making Connections: Interdisciplinary Approaches to Cultural Diversity, 13(1), 24–30.

- Dewey, J. (1938). Experience and education. New York: Collier Books.

- Driscoll, A. (2000). Studying faculty and service-learning: Directions for inquiry and development. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 1, 35–41.

- Driscoll, A., Holland, B., Gelmon, S., & Kerrigan, S. (1996). An assessment model for service-learning: Comprehensive case studies of impact on faculty, students, community, and institution. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 3(1), 66–71.

- Eyler, J., Giles, D. E., Jr., & Braxton, J. (1997). The impact of service-learning on college students. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 4(1), 5–15.

- Ferrari, J. R., & Worrall, L. (2000). Assessments by community agencies: How “the other side” sees service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 7(1), 35–40.

- Furze, J., Black, L., Peck, K., & Jensen, G. M. (2011). Student perceptions of a community engagement experience: Exploration of reflections on social responsibility and professional formation. Physiotherapy Theory and Practice, 27(6), 411–421.

- Groh, C. J., Stallwood, L. G., & Daniels, J. J. (2011). Service-learning in nursing education: Its impact on leadership and social justice. Nursing Education Perspectives, 32(6), 400–405.

- Henry, S. E. (2005). “I can never turn my back on that”: Liminality and the impact of class on service-learning experience. In D. W. Butin (Ed.), Service-learning in higher education: Critical issues and directions (pp. 45–66). New York, NY: Palgrave Macmillan.

- Hess, D. J., Lanig, H., & Vaughan, W. (2007). Educating for equity and social justice: A conceptual model for cultural engagement. Multicultural Perspectives, 9(1), 32–39.

- Kamberelis, G., & Dimitriadis, G. (2011). Focus groups: Contingent articulations of pedagogy, politics, and inquiry. In N. K. Denzin, & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The SAGE handbook of qualitative research (4th ed., pp. 545–561). Thousand Oaks, CA.: Sage.

- Keen, C., & Hall, K. (2009). Engaging with difference matters: Longitudinal student outcomes of co-curricular service-learning programs. The Journal of Higher Education, 80(1), 59–79.

- Kelly, M. J. (2013). Beyond classroom borders: Incorporating collaborative service learning for the adult student. Adult Learning, 24(2), 82–84.

- Kendrick, J. R. (1996). Outcomes of service-learning in an introduction to sociology course. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 3(1), 72–81.

- Kilgo, C. A., Ezell Sheets, J. K., & Pascarella, E. T. (2015). The link between high-impact practices and student learning: Some longitudinal evidence. Higher Education, 69(4), 509–525.

- Knapp, T., Fisher, B., & Levesque-Bristol, C. (2010). Service-learning’s impact on college students’ commitment to future civic engagement, self-efficacy, and social empowerment. Journal of Community Practice, 18, 233–251.

- Lockeman, K. S., & Pelco, L. E. (2013). The relationship between service-learning and degree completion. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 20(1), 18–30.

- Lovat, T., & Clement, N. (2016). Service learning as holistic values pedagogy. Journal of Experiential Education, 39(2), 115–129.

- McMenamin, R., McGrath, M., Cantillon, P., & MacFarlane, A. (2014). Training socially responsive health care graduates: Is service learning an effective educational approach? Medical Teacher, 36(4), 291–307.

- McMenamin, R., McGrath, M., & D’Eath, M. (2010). Impacts of service learning on Irish healthcare students, educators, and communities. Nursing & Health Sciences, 12(4), 499–506.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. (2nd ed.) Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Miller, D. C., & Salkind, N. J. (Eds.). (2002). Handbook of research design and social measurement (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Mitchell, T. D. (2007). Critical service-learning as social justice education: A case study of the Citizen Scholars Program. Equity & Excellence in Education, 40(2), 101–112.

- Mitchell, T. D. (2015). Using a critical service-learning approach to facilitate civic identity development. Theory Into Practice, 54(1), 20–28.

- Paoletti, J. B., Segal, E., & Totino, C. (2007). Acts of diversity: Assessing the impact of service-learning. New Directions for Teaching and Learning, 111, 47–54.

- Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative research & evaluation methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

- Pompa, L. (2002). Service-learning as crucible: Reflections on immersion, context, power, and transformation. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 9(1), 67–76.

- Pribbenow, D. A. (2005). The impact of service-learning pedagogy on faculty teaching and learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 11(2), 25–38.

- Rockquemore, K. A., & Harwell Schaffer, R. (2000). Toward a theory of engagement: A cognitive mapping of service-learning experiences. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 7(1), 14–25.

- Sanders, M. J., Van Oss, T., McGeary, S. (2016). Analyzing reflections in service learning to promote personal growth and community self-efficacy. Journal of Experiential Education, 39(1), 73–88.

- Sandy, M., & Holland, B. A. (2006). Different worlds and common ground: Community partner perspectives on campus-community partnerships. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 13(1), 30–43.

- Schmidt, A., & Robby, M. A. (2002). What’s the value of service-learning to the community? Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 9(1), 27–33.

- Seider, S. C., Rabinowicz, S. A., & Gillmor, S. C. (2011). The impact of philosophy and theology service-learning experiences upon the public service motivation of participating college students. The Journal of Higher Education, 82(5), 597–628.

- Seifer, S. D., & Connors, K. (Eds.). (2007). Faculty toolkit for service-learning in higher education. Scotts Valley, CA: National Service-Learning Clearinghouse.

- Srinivas, T., Meenan, C. E., Drogin, E., & DePrince, A. P. (2015). Development of the community impact scale measuring community organization perceptions of partnership benefits and costs. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 21(2), 5–21.

- Strange, A. A. (2000). Service-learning: Enhancing student learning outcomes in a college-level lecture course. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 7(1), 5–13.

- Turner, V. (1969). The ritual process: Structure and anti-structure. Chicago, IL: Aldine Publishing.

- Vernon, A., & Ward, K. (1999). Campus and community partnerships: Assessing impacts and strengthening connections. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 6(1), 30–37.

- Vogelgesang, L. J., & Astin, A. W. (2000). Comparing the effects of community service and service-learning. Michigan Journal of Service Learning, 7(1), 25–34.

- Wozencraft, A., Pate, J. R., & Griffiths, H. K. (2014). Experiential learning and its impacts on students’ attitudes toward youth with disabilities. Journal of Experiential Education, 38(2), 129–143.

Authors

LORRIE GEORGE-PASCHAL is the Service-Learning Faculty Liaison and Professor of Occupational Therapy at the University of Central Arkansas. Dr. Paschal also serves as the Director for the American Occupational Therapy Scholarship of Teaching and Learning Institute and Mentoring Program. She holds a PhD in Occupational Therapy from the Texas Woman’s University.

AMY HAWKINS is the Director of the Center for Teaching Excellence at the University of Central Arkansas (UCA), leading faculty development initiatives to strengthen teaching and learning at UCA. She is also an Associate Professor of Public Relations in UCA’s School of Communication. She holds a PhD in Organizational Leadership from Regent University and is Accredited in Public Relations (APR) through the Public Relations Society of America (PRSA).

LESLEY GRAYBEAL is the Director of Service-Learning at the University of Central Arkansas (UCA) and teaches qualitative methods and community-based research in UCA’s PhD in Leadership Studies program. Her current research interests focus on community perspectives, community-based research, and critical service-learning. She holds a PhD in Social Foundations of Education from the University of Georgia.