“I live both lives”

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This research incorporates theories of intersectional identities, place identity, and critical geography to synthesize a conceptual framework for “double consciousness” in students from a racialized city attending an engaged college in that city. Through 21 phenomenological interviews with resident-students, two themes about the city related to stereotypes and civic engagement emerge. In the interviews, students tell personal narratives of transcending these stereotypes and express responsibility for success among future generations from their city. The study identifies the critical need for service-learning practitioners in higher education to be aware of and sensitive to portrayals of the community, particularly related to issues of racialization, civic engagement, and student development. We propose additional lines of inquiry that will improve our understanding of place identity and service-learning.

I think it has strengthened my relationship with the city, especially the way I used to feel in high school about it. How I just kinda wanted to get out and be above, or do things differently than what most people expected me as a Camden resident to do. I think coming [to college] here really made me realize that there’s nothing to run from here. Everything that I love and want to be around I can find it right here in my city so it’s really made me realize that it is a great place regardless of what people think. –Anna

I feel like it’s really good to give back to your community because if you won’t, who else will? Like right now I’m in Jumpstart, and I’m a leader and the kids, I teach the kids, and there’s this program at Jumpstart … that help us give … a minority to get a head start in life, teaching them literacy, and reading sessions and things like that, and I feel that’s really good, it’s helping us help the generation that is coming up to be more well equipped. –Marta

The students that made these statements grew up and live in a segregated city that is stigmatized for its poverty, violence, and minority composition relative to its surrounding suburbs (Massey & Denton, 1993). They attend a college in that city (as resident-students), and this college is deeply engaged with their communities. This research incorporates three theoretical frameworks (intersectional identities, place identities, and the racialization of place) to synthesize a conceptual framework of “double consciousness” (Du Bois, 1903; Hickmon, 2015) related to resident-students’ need to transcend stereotypes of their city while simultaneously feeling a burden to ensure future generations of residents have better opportunities than those afforded to them. Resident-students who come from a majority-minority city and that are attending an institution that is deeply engaged with their home community inhabit this dualism.

Much of the current research on service-learning and community engagement focuses on students’ identity development (Bringle, 2017). However, Bringle (2017) also acknowledges that identity development and multiple identities “might be further complicated when students come from communities in which they are doing their service” (p. 83). Siemers, Harrison, Clayton, and Stanley (2015) remark that research on and practice of service-learning is place-neutral, “diminishing the complexity of identity issues for students who might already be in and of communities with whom they partner” (p. 101). The present study examines these claims to better understand how engaged universities influence resident-students’ multiple identities and perspectives relative to their sense of place (Proshansky, Fabian, & Kaminoff, 1983; Relph, 1976). We approach this work from a critical geography lens given the socially constructed reality of the racialization of the place at play in this work (Bonam, Taylor, & Yantis, 2017; Bonnett, 1996; Inwood & Yarbrough, 2010; Whitehead, 2000). We define resident-students as university students who spent significant time growing up in the host city of the university in this study. In connecting the words “resident” and “student” via a hyphen, we are borrowing a dyad from Bringle, Clayton, and Price’s (2009) SOFAR framework for research on service-learning. For the purposes of this research, we employ broader definitions of service-learning and civic engagement consistent with Jacoby’s (2009, 2014) definitions that encompass both curricular and co-curricular experiences, including student-led experiences.

This research contributes to our understanding of the role of place in service-learning. It also critically examines the intersectional identities of students of color from racialized cities that attend engaged universities and offers perspective on the role of place identity to describe a double consciousness shaped by stereotypes and engagement with their city. The implications for this work are to better prepare service-learning educators for engaging diverse communities with respect and sensitivity to how the community is portrayed while drawing community engagement practice into a broader discourse related to the roles of race and place in shaping identity.

Theoretical Framework

Multiple Identities

The reconceptualized model of multiple identity development (Abes, Jones, & McEwen, 2007; Jones & Abes, 2013) is a powerful conception of socially constructed identities and how these identities shape the college student experience. This perspective draws heavily from feminist, queer, and critical race theories (Andersen & Collins, 2016). This theoretical base suggests that identities are socially constructed. Weber (2009) writes that “[identities’] meaning can and does change over time and in different social contexts” (p. 91). Jones and Abes (2013) locate the development of self as an outgrowth of the society developing around an individual. They assume that individuals are capable of reflecting on their self (or on multiple selves) and that this reflection influences an individual’s roles within society and therefore the salience of a particular identity in shaping these roles. The theory suggests that as new information from a person’s context is filtered through a process of meaning-making (Magolda, 1999, 2001), the information shapes how the context influences a person. This article investigates multiple identities of resident-students and introduces place identity as an additional facet of college student identity to develop deep understanding of double consciousness.

Place Identity

Place identity refers to how attributes of places contribute to self-identification (Proshansky et al., 1983). Place identity is seen as the manifestation of parts of identity that are based not on the individual, interpersonal, or social processes that shape our identity but instead on the ways that the physical environment shapes a person’s sense of self. The theory posits that a person’s identity is tied to “cognitions about the physical world in which the individual lives” (p. 59). These cognitions are then either challenged or reinforced when individuals encounter new places and shape “how individuals engage in and participate in the present” (Lim, 2010, p. 902).

Recent scholarship argues that place identity is not simply the interaction of the individual and the physical world but that place identity may also be shaped by social interactions and can be represented by the social processes that shape social identity theory (Belanche, Casaló, & Flavián, 2017; Bernardo & Palma-Oliveira, 2016; Hernández, Hidalgo, Salazar-Laplace, & Hess, 2007). Bernardo and Palma-Oliveira (2016) tested urban place identity as a particular kind of social identity and found that geographical area of residence can be an important contributor to self-definition through a social process of comparing one’s own neighborhood to relevant out-groups: neighborhoods and places in other areas. Belanche et al. (2017) draw from social representations theory to define an urban identity “(1) as a feature of the city based on a collective attribution and (2) as the self-identification of the person with the city” (p. 139).

Racialization of Place

Barot and Bird (2001) trace the concept of racialization as the process used by sociologists and other disciplines to study racism and how it structures societies. When discussing the intersection of race and place identity, the concept of racialized landscapes emerges (Bonnett, 1996; Jackson, 1985). Bonam, et al. (2017) discuss how racial group identities are associated with a physical space, because they are often stereotypically confined to a specific place. Inwood and Yarbough (2010) find that “a multifaceted relationship exists between place and race wherein places are racialized while places also structure, construct, and re-produce racialized individual identities” (p. 300). These places are described as racialized urban ghettos and are often associated with deficit perspectives that blame victims of structural inequities for their social positions (Whitehead, 2000). The present study investigates the social identity aspects of place in a racialized city that bears a double burden of concentrated poverty and distress relative to its wealthier, white, suburban neighbors (Kneebone, Nadeau, & Berube, 2011; Sampson, Morenoff, & Gannon-Rowley, 2002). We believe that this burden manifests itself in resident-students’ place identities as a kind of double consciousness when students are confronted with the challenge of serving in their home community.

Double Consciousness

W. E. B. Du Bois in his 1903 book The Souls of Black Folk introduces a concept of a “double-consciousness.” He writes:

the Negro is a sort of seventh son, born with a veil, and gifted with second-sight in this American world,—a world which yields him no true self-consciousness, but only lets him see himself through the revelation of the other world. It is a peculiar sensation, this double-consciousness, this sense of always looking at one’s self through the eyes of others, of measuring one’s soul by the tape of a world that looks on in amused contempt and pity. (p. 3)

Bruce (1992) argues that double consciousness reflects both the power of white stereotypes of black life as well as the practical racism that excluded blacks from full participation in society. Rawls (2000) points to the veil as the operative concept in regard to the incomplete self. Self-consciousness behind the veil is constructed both by individuals taking roles in society but also from taking the roles assigned by society by virtue of race. Itzigsohn and Brown (2015) argue this theory of double consciousness is a relevant conception of black intersubjectivity that proves helpful for conducting cultural analyses of the racialized groups in society.

In the 2015 Future Directions for Service-Learning and Community Engagement issue of the Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, Hickmon explores this double consciousness in relation to service-learning, writing “I look at myself through two sets of eyes: those in my classroom and those in my community” (p. 87). She raises issues related to the traditional server role (of students) vs. the traditional served role (of community) (Chesler & Vasques Scalera, 2000). She argues for a service-learning practice that addresses its whiteness (Bocci, 2015; Butin, 2006; Green, 2003; Mitchell, Donahue, & Young-Law, 2012).

Following Mitchell and Rost-Banik’s (2017) call for more critical service-learning research, this research interrogates these questions and produces a conceptual framework for understanding double consciousness for resident-students. We examine how place identity interacts in these multiple, intersectional identities frameworks and is changed by the experience of attending college in a resident-student’s home community when that place is racialized. To that end, we pose the question: Do resident-students from racialized cities who attend civically engaged universities in their home community experience a change in their place identity consistent with a double consciousness?

To answer our research question, we choose a qualitative, phenomenological approach. Brown and Hale (2014) state that the qualitative research approach is used to answer questions that “have to do with context, environment, and holistic assessment of a situation or problem” (p. 137). According to Marshall and Rossman (2016), “phenomenology is the study of lived experiences and the way we understand those experiences to develop a worldview” (p. 153). Furthermore, van Manen (1984) describes the phenomenological approach as an attempt “to gain insightful descriptions of the way we experience the world” (p. 39). Because we seek to identify these resident-students’ experiences with place identity in a racialized city and society, a critical phenomenological approach is best suited for this study (Fanon, 1952; Henry, 2004; Salamon, 2018).

Methodology

To answer our research question, we choose a qualitative, phenomenological approach. Brown and Hale (2014) state that the qualitative research approach is used to answer questions that “have to do with context, environment, and holistic assessment of a situation or problem” (p. 137). According to Marshall and Rossman (2016), “phenomenology is the study of lived experiences and the way we understand those experiences to develop a worldview” (p. 153). Furthermore, van Manen (1984) describes the phenomenological approach as an attempt “to gain insightful descriptions of the way we experience the world” (p. 39). Because we seek to identify these resident-students’ experiences with place identity in a racialized city and society, a critical phenomenological approach is best suited for this study (Fanon, 1952; Henry, 2004; Salamon, 2018).

Case Selection and Sample

In designing this study, we construct a case study of an engaged university in a racialized city (Stake, 2005). We select Rutgers University–Camden because it is a Carnegie-classified community engaged university in a distressed city that is 47% Latino and 44% African American (US Census Bureau, n.d.), making this an instrumental case for answering questions about college students’ urban place identity. For this study, we used a randomized purposeful sample (Miles & Huberman, 1994) of 21 Rutgers University–Camden students who lived in Camden before their matriculation at Rutgers. Descriptive information about the sample is presented in the Appendix.

Data Collection and Analysis

Each member of the 10-person research team was randomly assigned 22 resident-students from a list of 323 names and emails we obtained from the university registrar following an IRB-approved protocol, and all names included in this manuscript have been changed to protect the identities of the participants. Researchers were responsible for interviewing two resident-students from their list using a semi-structured interview protocol. According to Brown and Hale (2014), semi-structured interviews “strike a balance between the limitations of structured and unstructured interviews” (p. 147), allowing interviewers to go off-script and explore threads brought up by participants. As a team, we developed an interview guide to examine the role of place in the resident-students’ experiences both before college and during college, asking questions about growing up in Camden; civic participation; and race, gender, and other identities. The interview guide is available upon request.

As in O’Connor, Rice, Peters, and Veryzer (2003), our diverse research team was confronted by the challenges of developing shared meaning as we began analyses for this research project, but we were also enriched by the diversity of perspectives. One member of our research team grew up in Camden; her perspectives and positionality as a “native” researcher enriched our understanding of the lived experiences of our research participants (Kanuha, 2000). Another member of the team is a former coordinator of service-learning courses at the university in this study, enabling the team to better interpret the relevant discussion of the experiences with the college. In research team meetings, we reflexively evaluated the statements in our data from these perspectives to find the essence of the experiences present in our data in our attempt to develop a critical phenomenology (Fanon, 1952; Henry, 2004).

Each member of the research team transcribed their interviews, and we created a database. Once the interviews were transcribed, each team member read the transcriptions so the research team could discuss the emergent themes and adjust their interviewing (Tesch, 1987). We approached the analysis by reviewing each interview transcript and using an elaborative coding scheme, a technique often associated with grounded theory methods (Auerbach & Silverstein, 2003; Saldaña, 2009), based on the theoretical basis of our article to examine the double consciousness described in a previous work. As a team, we grouped codes based on meaning and collapsed groups into broad themes (Marshall & Rossman, 2016). Following Merriam and Tisdell (2015), we then engaged in an iterative process of identifying meaningful statements that responded to our question based on these themes, writing and reviewing our work until a conceptual framework emerged from the data that responded to our question: Do resident-students from racialized cities who attend civically engaged universities in their home community see a change in their place identity consistent with a double consciousness?

The main purpose of this study is to examine the experiences of resident-students attending an engaged university in their home community to understand if and how their place identity changed. We find that resident-students inhabited two, simultaneous identities of student and resident consistent with a double consciousness. Two major themes emerge from the data related to the experience of being from the city that explain this double consciousness: stereotypes of the city and engagement in the city.

Findings

The main purpose of this study is to examine the experiences of resident-students attending an engaged university in their home community to understand if and how their place identity changed. We find that resident-students inhabited two, simultaneous identities of student and resident consistent with a double consciousness. Two major themes emerge from the data related to the experience of being from the city that explain this double consciousness: stereotypes of the city and engagement in the city.

Stereotypes of Place

Each student had stories related to the experience of growing up in Camden rooted in how others perceive the city. These stories often serve as counternarratives to the perceptions of the city as uniformly violent or impoverished. The city of Camden experienced economic decline since its peak in the 1950s (Seligsohn & Mazelis, 2014), which has led to increases in crime, poverty, and distress. This decline has led to a nearly universal perception of the city being a “bad place.” Naomi discusses the reality for many residents who face struggles in day-to-day life but also in the negative stereotypes placed upon them and their city:

So much that they have to deal with or prepare themselves to deal with before they even walk out their front door… it’s not all peaches and cream and it’s not all beautiful at the same time but there’s still some good points and if we tend to focus on the negative, the negative, the negative, the negative and you’re constantly fed negativity and “you’re not going to be anything” … “you’re less than normal” … or just whatever then it’s kind of hard to face that reality.

Adriana sums up this perception: “Everybody’s made up their mind that Camden is bad. … It’s this bad place and nothing good can ever come from Camden.” She goes on to detail a harrowing experience when a person was murdered outside her home:

And my mom woke up and she was like “what just happened?” And I was like “someone just got shot outside.” And we were like freaking out but we were like “what do we do?” … And it was like the scariest thing in the world, they came and took him away and they closed the street for like two hours and it was crazy. It was just crazy. So we don’t … The kids can’t ride their bikes outside. My dad fenced in the backyard—it’s a pretty big backyard … it’s okay.

This shocking story demonstrates the ever-present threat of violence in the city. Furthermore, many resident-students described parents as “strict,” “tough love type,” not allowing resident-students to “be outside a lot,” suggesting that either real or perceived dangers of the city required families to protect their children. This pattern was also represented by comments suggesting that the house or home is many resident-students’ primary, or even only, symbol for the city, as their “bubble,” “cloud,” “safe space,” or as Alana commented, “not really my neighborhood because I could live anywhere, but my house is my house, like it’s my space.”

At the same time, perception of the city as a dangerous place is problematic for many resident-students; they express not seeing or feeling this characterization in their experience. Anna explains:

So I have personally never seen it as the most dangerous city. Then when I went to high school outside of the city and learned other people’s perceptions of it, I can see where, you know, this fear and this idea that it is [violent] … but just me, personally, being in the city my whole life, I just could never picture it as that.

Roughly half of the sample express this kind of counternarrative in explaining their upbringing, characterizing their neighborhoods as “quiet,” “calm,” “decent,” “comfortable,” “normal,” or “just like anywhere else.”

Despite this counternarrative, Andrew stated that “they look at me like I have eight heads” but feels he must express “Yes, I’m perfectly fine” to classmates and instructors. Sandy frames it as being “looked at as something else, other than humans” and describes it as “the media’s perception of Camden.” Susan describes the feeling as a form of discrimination and people “look at you like you’re crazy … because they say it on the media.”

A similar pattern emerged when discussing curricular service-learning. For several, experiences in these classes presented dilemmas of confronting the stereotypes of their city within the classroom. During her interview, Sandy relates her experience in a service-learning course, which she at times described as both “dumb” and “kind of powerful”:

- Interviewer: In those kinds of classes, you have [other students] from “not Camden,” and they go do [civic engagement] too?

- Sandy: They look very uncomfortable …

- Interviewer: Yea?

- Sandy: Most of the times … they’re not from Camden, they’re like, “How do I deal with these kids? What do I do?” I’m like, “You treat them just like you would treat kids if you were in your neighborhood. If you went to Cherry Hill, what would you do? You would sit down with them, talk to them, see how their day went, get a feel for how they’re feeling of the day,” because they might not want to read, that’s just the truth … but [suburban classmates] kind of just didn’t know what to do as if the kids weren’t normal kids … but it’s kinda hard for them to understand that no matter where these kids are from they all need to have the same kinds of basics, they all need to be treated the same, they all kind of need … how do I say it? They need the resources that they kind of may be lacking in a city like Camden, which is why we did that civic engagement …

Ramona similarly confronted this pattern, remarking:

Just the way [my classmate] was describing them, I took so much offense to that because I thought I was at one point … one of those kids. So don’t be so quick to judge them, you don’t understand why they are doing what they are doing or where they are coming from. So just instances like that it’s … I am defensive.

These comments suggest that students are faced with problematic perceptions of their city in courses that engage with their city. Other students discussed the similarly problematic engagement with both faculty and fellow students outside of the context of service-learning courses, signaling that these experiences occur with a disturbing frequency for students of color at this university. Although stereotypes shaped the experiences of many in our sample, many students express a sense of responsibility for improving the city to change these stereotypes.

Civic Engagement in the City

Within this theme, we find that resident-students have two dominant narratives: one of giving back and one of a changing identification with their city. Within these narratives, civic activity takes multiple forms, and the table in the Appendix summarizes the various ways resident-students participated in civic engagement. Several resident-students remark about the importance of serving Camden. Marta’s comment at the beginning of this article highlights a sense of civic responsibility that is shared frequently by other resident-students in our research. Marta believes her experiences at Rutgers and in the community will carry forward in how she understands others from a broader perspective, sharing that she used to see Camden as all “dead ends” but “that’s how Rutgers has maybe changed my perspective … [to] make us believe truly that we’re not a dead end.”

Sandy, who is quoted above problematizing her curricular service-learning experiences, uses a metaphor of passing the torch to describe other participation through a student-led program and states:

Then they’ll get knowledge, it’s kind of like an indescribable meaning. Because they [Camden youth] don’t know what they’re getting themselves into, until they’re there, but now they’re doing, and that’s kind of what Rutgers Future Scholars is all about, and the Hill Family Center [for College Access], like they had knowledge and they passed it on to us. They [our mentors] didn’t give us like all the knowledge because they didn’t know everything but then you go and you get knowledge, and you’re like, “I have to give this to someone, I need to somehow help someone,” and that’s all we’re really doing.

This comment highlights the role that supportive programs on campus play in structuring civic activities but also that many of these students play supportive roles for youth in their community. Ada remarks that college students from Camden serve as important role models for youth, stating “I do know that the kids look up to other people who are from here … because I looked up to people who were in the same area.” In terms of her civic engagement, Gabrielle described the feeling as living “both lives”:

- Interviewer: What do you mean you live both lives?

- Gabrielle: Like I live in Camden and like I go to the school too, so I can kind of understand better [that] if you want to influence the community, and help college rates and help high school rates, something that can help be extensive …

- Interviewer: Like that experience leverages your ability to help?

- Gabrielle: YES! And so I have a lot of great ideas, and I’m just working on putting some things together so I can just go ahead and try to create something new, because I do feel like, Rutgers is definitely on a good movement, and Rutgers is definitely a good school to go to, and it can set you up and expose you to a lot of things.

Through these experiences, resident-students form new understandings of their city. Adriana, whose traumatic experience shaped her view of the city, now serves as a Civic Scholar and says “I’m not scared of my community anymore” and sees “an upgrade” in her view of the city. Later in her interview, Gabrielle also describes her relationship with the city in this way:

Now I feel like I’m connected but I am still who I am so, yeah, I definitely appreciate my city more … I used to feel like we were lesser than because people saw us as lesser than, but I feel like now we are who we make ourselves. There are a lot of people in Camden who are great people, who are doing great things, who have aspirations, but it’s just that the violence and the criminal activity sometimes overpowers that and, you know, the people who are doing great things just become a shadow in a dark place.

Place Identity as a Double Consciousness

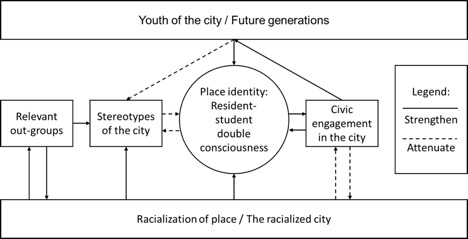

The two major themes, stereotypes of the city and civic engagement in the city, represent points of divergence for resident-students’ identities. A conceptual framework for place identity as a double consciousness is presented in Figure 1. This diagram purposefully forms the shape of a home, reflecting the importance of that symbol in many of our resident-students’ experiences. This home’s foundation is a racialized landscape, structuring the resident-students’ identity and interaction with others inside and outside of the university (Bonam et al., 2017; Inwood & Yarbrough, 2010).

In this formulation, the resident-student’s identity is represented as the circle in the center. The relationship between stereotypes of the city and the individual represent ways in which the individual’s identification with the place are attenuated, indicated by the dashed line going from stereotypes to the individual. However, these individual’s counternarratives are represented as a dashed line going back to the stereotypes, diminishing the effects of the stereotypes of the city on their place identity. Relevant out-groups are seen as a force that increases the stereotypes, indicated by the solid line in that direction (Belanche et al., 2017; Bernardo & Palma-Oliveira, 2016; Bonam et al., 2017). These out-groups’ interactions with the city mutually reinforce the racialization of place through a bidirectional relationship.

The bidirectional relationships between the individual and civic engagement in the city in Figure 1 represent the influences that service-learning and civic engagement have on the resident-student’s place identity but also that their place identity influences how they engage with their city. Passing the torch is seen through the arrows going from civic engagement to the future generations in a positive relationship (solid line) and from the future generations to the stereotypes in an attenuating relationship (as indicated by the dashed line); we see future generations also positively influence the resident-student’s identification with place. These actions represent a kind of counternarrative that restructures the experiences for youth in response to the racialization of the city.

Discussion and Implications

This research investigated the place identity of resident-students to uncover a conceptual framework of double consciousness because previous scholarship theorized that such a dualism may exist (Bringle, 2017; Hickmon, 2015; Siemers et al., 2015). This research adds to our understanding of that theoretical foundation by systematically describing and critically examining the patterns present in our phenomenological case study: one related to stereotypes and one related to civic engagement. We find intersections of the influences of relevant out-groups, future generations of Camden youth, and racialized cities that relate back to our themes and research question reflecting an intersubjective lived experience of being a Rutgers–Camden student from Camden. These findings have implications for the field of service-learning and draw the service-learning field into a broader discussion of the ways race, place, and identity interact to structure experiences in communities of color from a critical geography perspective.

Consistent with Hickmon’s (2015) double consciousness, we see resident-students embodying two distinct positions: student and community member. This pattern is in line with the concept of identity salience (Jones & McEwen, 2000). In the synthesis of double consciousness, we see that for many resident-students, changes in place identity and how they understand their self in the world shifts to accommodate these dual positions. To that end, we find that place identity forms and changes as an outgrowth of societal patterns around our resident-students but also resulting from the social interactions of students (Jones & Abes, 2013). We also find evidence of meaning-making and self-authorship in comments from students like Gabrielle, Marta, and Adrianna about their place identity and other constructs, consistent with the theoretical framework of the reconceptualized Model of Multiple Identity Development (Abes et al., 2007). Furthermore, by applying an intersectional lens, this research “places the experiences of people of color at the center as the core of any analysis” (Jones & Abes, 2013, p. 158), which is essential for critical interpretation of this double consciousness (Mitchell & Rost-Banik, 2017).

Du Bois described double consciousness as a veil that persons of color live behind, one that inhibits the process of self-identity development given conflicts arising between “the macrostructure of the racialized world and the lived experience of racialized subjects” (Itzigsohn & Brown, 2015, p. 231). We see that resident-students discussed their personal experience framed by how they perceive others see their lives. From the quotations in the introduction, Anna discusses “what other people think” or “expect … a Camden resident to do,” while other interviews discuss the “media” portrayal as dominating non-resident perceptions. This reflexive comparison to others echoes a pervasive, implicit bias felt by residents of the city, wherein overt racial stereotypes are replaced by coded references to Camden and its residents (Bonam et al., 2017). Resident-students also discuss stereotypes held by other service-learners and their professors that reinforce the racialization, so resident-students spoke of a strong desire to reconcile public perceptions with their own experiences and to prove stereotypes wrong—often taking this on as a personal goal or responsibility (Rawls, 2000). These counternarratives challenge the dominant narrative that negatively constructs the city as “bad” to reflect the lived reality of resident-students in their community and at their university (Solórzano & Yosso, 2002).

The propensity for resident-students to give back to their community is in line with Du Bois’s belief that a duty to one’s community is the way to overcome the incompleteness in identity that double consciousness causes for people of color (Rawls, 2000). Du Bois believed that commitment to Black community would allow individuals to transcend these internal separations and assert themselves in oppressive contexts (Itzigsohn & Brown, 2015). This commitment, or duty, to community is frequently mentioned by resident-students as a desire to “influence the community,” to “equip” or “pass the torch” to a future generation.

Resident-students can find great value in their civic activities, and these activities give them a sense of purpose (Yeh, 2010). We observe that civic engagement opportunities occur in different venues (campus, local organizations, etc.; see Appendix). For at least half of the sample, students identified engagements that were not university related. The overwhelming majority shared one or more of the engagements they had with their city’s youth (early ages through high school). How resident-students chose to engage reflected a counternarrative to the prevailing stereotype of the city and its residents, attempting to restructure the experience for the next generation of youth.

However, for curricular service-learning in particular, we find evidence that resident-students feel a double burden of serving the community and representing the community, consistent with Hickmon’s (2015) account and discussions of race and gender issues raised by Chesler and Vasques Scalera (2000). They often confront fear, racism, or misunderstanding from their classmates in these environments (Mitchell et al., 2012). Service-learning practitioners should continue to work to ensure a culturally aware practice that forefronts how the community is portrayed when facilitating both the service and the reflection activities. Practitioners should identify and interrupt systems that replicate racialized constructions of place and the perceived deficits of those places.

Faculty may find value in collaborating with student supportive services on the campus as suggested by Engstrom (2003). Such partnerships may include tapping into units responsible for offering workshops that help all students explore their assumptions and their understanding of stereotypes about places and people they will engage with. Such partnerships can validate resident-student experiences: ensuring that the burden of the double consciousness does not push them away from participation (Green, 2003) and avoiding their experiences being either ignored or “spotlighted” in the classroom (Carter, 2008). Service-learning research should continue to examine its whiteness (Bocci, 2015; Butin, 2006). We also recommend that service-learning researchers continue to examine place identity as a construct that is influenced by and influences civic activity.

To conclude, we wish to share another observation from Gabrielle, whose comment about living both lives gave us the title to this article. Referencing the impact of this research, she says “that’s the importance of [your] study … hopefully when you guys put it together, you guys really express the points of the goods and negatives that everybody projected … it can help people change the perception on things.”

Notes

We wish to acknowledge our classmates in Dr. Stephen Danley’s Qualitative Methods class in the fall of 2017 and Michael D’Italia who aided us in collecting the data used in this article. Our adventure together in the class was challenging and memorable. We also are grateful to the anonymous reviewers at the Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning and attendees at the 2018 International Association for Research on Service-Learning and Community Engagement for their recommendations and critical feedback.

References

- Abes, E. S., Jones, S. R., & McEwen, M. K. (2007). Reconceptualizing the model of multiple dimensions of identity: The role of meaning-making capacity in the construction of multiple identities. Journal of College Student Development, 48(1), 1–22.

- Andersen, M. L., & Collins, P. H. (2016). Race, class, & gender: An anthology (9th ed.). Boston, MA: Cengage Learning.

- Auerbach, C. F., & Silverstein, L. B. (2003). Qualitative data: An introduction to coding and analysis. New York, NY: New York University Press.

- Barot, R., & Bird, J. (2001). Racialization: The genealogy and critique of a concept. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 24(4), 601–618. doi:10.1080/01419870120049806

- Belanche, D., Casaló, L. V., & Flavián, C. (2017). Understanding the cognitive, affective and evaluative components of social urban identity: Determinants, measurement, and practical consequences. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 50, 138–153. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2017.02.004

- Bernardo, F., & Palma-Oliveira, J.-M. (2016). Urban neighbourhoods and intergroup relations: The importance of place identity. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 45, 239–251. doi:10.1016/j.jenvp.2016.01.010

- Bocci, M. (2015). Service-learning and White normativity: Racial representation in service-learning’s historical narrative. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 22(1), 5–17.

- Bonam, C. M., Taylor, V. J., & Yantis, C. (2017). Racialized physical space as cultural product. Social and Personality Psychology Compass, 11(9). doi:https://doi.org/10.1111/spc3.12340

- Bonnett, A. (1996). Constructions of “race,” place and discipline: Geographies of “racial” identity and racism. Ethnic and Racial Studies, 19(4), 864–883. doi:10.1080/01419870.1996.9993939

- Bringle, R. G. (2017). Social psychology and student civic outcomes. In J. A. Hatcher, R. G. Bringle, & T. W. Hahn (Eds.), Research on student civic outcomes in service learning: Conceptual frameworks and methods (pp. 77–91). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- Bringle, R. G., Clayton, P., & Price, M. (2009). Partnerships in service learning and civic engagement. Partnerships: A Journal of Service-Learning & Civic Engagement, 1(1). Retrieved from http://libjournal.uncg.edu/prt/article/view/415

- Brown, M., & Hale, K. (2014). Applied Research Methods in Public and Nonprofit Organizations. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Bruce, D. D., Jr. (1992). W. E. B. Du Bois and the idea of double consciousness. American Literature, 64(2), 299–309. doi:10.2307/2927837

- Butin, D. W. (2006). The limits of service-learning in higher education. The Review of Higher Education, 29(4), 473–498. doi:10.1353/rhe.2006.0025

- Carter, D. (2008). On spotlighting and ignoring racial group members in the classroom. In M. Pollock (Ed.), Everyday antiracism: Getting real about race in school (pp. 230–234). New York, NY: The New Press.

- Chesler, M., & Vasques Scalera, C. (2000). Race and gender issues related to service-learning research. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 18–27.

- Du Bois, W. E. B. (1903). The souls of black folk. Chicago, IL: A. C. McClurg.

- Engstrom, C. (2003). Developing collaborative student affairs—Academic partnerships. In B. Jacoby (Ed.), Building partnerships for service-learning (p. 65). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Fanon, F. (1952). Black skin, white masks. New York, NY: Grove Press.

- Green, A. E. (2003). Difficult stories: Service-learning, race, class, and whiteness. College Composition and Communication, 55(2), 276–301.

- Henry, P. (2004). Whiteness and Africana phenomenology. In G. Yancy (Ed.), What White Looks Like: African-American Philosophers on the Whiteness Question. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Hernández, B., Hidalgo, M. C., Salazar-Laplace, M. E., & Hess, S. (2007). Place attachment and place identity in natives and non-natives. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 27(4), 310–319. doi:1https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jenvp.2007.06.003

- Hickmon, G. (2015). Double consciousness and the future of service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 22(1), 86–88.

- Inwood, J. F., & Yarbrough, R. A. (2010). Racialized places, racialized bodies: The impact of racialization on individual and place identities. GeoJournal, 75(3), 299–301.

- Itzigsohn, J., & Brown, K. (2015). Sociology and the theory of double consciousness: W. E. B. Du Bois’s phenomenology of racialized subjectivity. Du Bois Review: Social Science Research on Race, 12(2), 231–248. doi:10.1017/S1742058X15000107

- Jackson, P. (1985). Social geography: Race and racism. Progress in Geography, 9(1), 99–108. doi:https://doi.org/10.1177%2F030913258500900105

- Jacoby, B. (2009). Civic engagement in higher education: Concepts and practices. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

- Jacoby, B. (2014). Service-learning essentials: Questions, answers, and lessons learned. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

- Jones, S. R., & Abes, E. S. (2013). Identity development of college students: Advancing frameworks for multiple dimensions of identity. San Francisco, CA: Wiley.

- Jones, S. R., & McEwen, M. K. (2000). A conceptual model of multiple dimensions of identity. Journal of College Student Development, 41(4), 405–414.

- Kanuha, V. K. (2000). “Being” native versus “going native”: Conducting social work research as an insider. Social Work, 45(5), 439–447. doi:https://doi.org/10.1093/sw/45.5.439

- Kneebone, E., Nadeau, C., & Berube, A. (2011). The re-emergence of concentrated poverty: Metropolitan trends in the 2000s. Washington, DC: Brookings Institution.

- Lim, M. (2010). Historical consideration of place: inviting multiple histories and narratives in place-based education. Cultural Studies of Science Education, 5(4), 899–909.

- Magolda, M. B. B. (1999). Creating contexts for learning and self-authorship: Constructive-developmental pedagogy. Nashville, TN: Vanderbilt University Press.

- Magolda, M. B. B. (2001). Making their own way: Narratives for transforming higher education to promote self-development. Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2016). Designing qualitative research (6th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Massey, D. S., & Denton, N. A. (1993). American apartheid: Segregation and the making of the underclass. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Merriam, S. B., & Tisdell, E. J. (2015). Qualitative research: A guide to design and implementation. (4th ed.). San Francisco, CA: Jossey-Bass.

- Miles, M. B., & Huberman, A. M. (1994). Qualitative data analysis: An expanded sourcebook. Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Mitchell, T. D., Donahue, D. M., & Young-Law, C. (2012). Service learning as a pedagogy of whiteness. Equity & Excellence in Education, 45(4), 612–629.

- Mitchell, T. D., & Rost-Banik, C. (2017). Critical theories and student civic outcomes. In Research on student civic outcomes in service learning: Conceptual frameworks and Methods (pp. 169–189). Sterling, VA: Stylus Publishing.

- O’Connor, G. C., Rice, M. P., Peters, L., & Veryzer, R. W. (2003). Managing interdisciplinary, longitudinal research teams: Extending grounded theory-building methodologies. Organization Science, 14(4), 353–373.

- Proshansky, H. M., Fabian, A. K., & Kaminoff, R. (1983). Place-identity: Physical world socialization of the self. Journal of Environmental Psychology, 3(1), 57–83.

- Rawls, A. W. (2000). “Race” as an interaction order phenomenon: W. E. B. Du Bois’s “double consciousness” thesis revisited. Sociological Theory, 18(2), 241–274.

- Relph, E. (1976). Place and placelessness (Vol. 1). London, UK: Pion.

- Salamon, G. (2018). What’s critical about critical phenomenology? Journal of Critical Phenomenology, 1(1). doi:10.31608/PJCP.v1i1.2

- Saldaña, J. (2009). The coding manual for qualitative researchers. Los Angeles, CA: Sage.

- Sampson, R. J., Morenoff, J. D., & Gannon-Rowley, T. (2002). Assessing “neighborhood effects”: Social processes and new directions in research. Annual Review of Sociology, 28(1), 443–478. doi:10.1146/annurev.soc.28.110601.141114

- Seligsohn, A., & Mazelis, J. M. (2014). The view from Camden. In S. Haymes, M. V. de Haymes, & R. Miller (Eds.), Routledge handbook of poverty in the United States. New York, NY: Routledge.

- Siemers, C. K., Harrison, B., Clayton, P. H., & Stanley, T. A. (2015). Engaging place as partner. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 22(1), 101–104.

- Solórzano, D. G., & Yosso, T. J. (2002). Critical race methodology: Counter-storytelling as an analytical framework for education research. Qualitative Inquiry, 8(1), 23–44.

- Stake, R. E. (2005). Qualitative case studies. In N. K. Denzin & Y. S. Lincoln (Eds.), The Sage handbook of qualitative research (3rd ed., pp. 443–466). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

- Tesch, R. (1987). Emerging themes: The researcher’s experience. Phenomenology + Pedagogy, 5(3), 230–241.

- US Census Bureau. (n.d.). Decennial Census by Decades. Retrieved March 31, 2018, from https://www.census.gov/programs-surveys/decennial-census/decade.html

- van Manen, M. (1984). Practicing phenomenological writing. Phenomenology + Pedagogy, 2(1), 36–69.

- Weber, L. (2009). Understanding race, class, gender, and sexuality: A conceptual framework (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Oxford University Press.

- Whitehead, T. L. (2000). The formation of the US racialized urban ghetto. Unpublished manuscript, CuSAG Working Papers in Applied Urban Anthropology, University of Maryland.

- Yeh, T. L. (2010). Service-learning and persistence of low-income, first-generation college students: An exploratory study. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 16(2). Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0016.204

Authors

THOMAS A. DAHAN ([email protected]) earned his PhD from the Public Affairs/Community Development program at Rutgers University–Camden in May of 2019. His dissertation examines the community impact of service-learning using nationally representative data from the 1990s through the present. He holds a Master’s in Teaching, Learning and Curriculum from Drexel University and a Bachelor of Political Science from the University of Florida.

KATHRYN CRUZ is a PhD student in Public Affairs, Rutgers University–Camden. She studies critical environmental justice, land tenure, and race and resistance. She is currently working on her dissertation exploring trauma and restoration in urban agriculture in the Philadelphia region. In addition, she is an Adjunct Professor at Eastern University in the Sociology Department teaching courses related to social stratification, inequality, and social justice.

SIS. ANETHA PERRY is a PhD student in Public Affairs, Rutgers University–Camden. Sis. Perry was raised in Camden, New Jersey, with research interests including community development and empowerment. She was recognized as the Department of Public Policy and Administration “Ph.D. Student of the Year” in 2016.

BRIAN HAMMELL is a PhD candidate in Public Affairs, Rutgers University–Camden and a US Air Force intelligence analyst whose research interests include the influence of drug policy on community outcomes of health and well-being. He is currently working on his dissertation, which is looking at community and economic development effects of marijuana legalization in Colorado.

STEPHEN DANLEY is Associate Professor of Public Policy and Administration, Rutgers University–Camden. Dr. Danley is an urban ethnographer who focuses on the intersection of participation, protest, and power. A Marshall Scholar and Oxford DPhil, his work focuses on the experience and strategy of protest, community responses to policy experiments, and the structures or systems necessary to facilitate participation. He is a BrandeisENACT Fellow, a scholar-activist, and an advocate for local knowledge and civic engagement as foundational to both urban policy and urban universities.

Appendix

| Civic activities discussed by participant | |||||||||

| Pseudonym | Ethnicity | Age | Gender | Jumpstart | Access programs | Curricular | Co-curricular | Non-Rutgers | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Anna | Puerto Rican | 21 | F | x | 1 | ||||

| Marta | Mexican & Salvadorian | 19 | F | x | x | 2 | |||

| Adrianna | Mexican | 19 | F | x | 1 | ||||

| Andrew | Black | U | M | x | 1 | ||||

| Sandy | Dominican | 20 | F | x | x | 2 | |||

| Diana | Puerto Rican & Black | 56 | F | x | 1 | ||||

| Gabrielle | Black | U | F | x | 2 | ||||

| Manny | Mexican & Puerto Rican | U | M | x | 2 | ||||

| Manuel | Puerto Rican | 21 | M | x | x | x | x | 4 | |

| Jackie | Black | 22 | F | x | 1 | ||||

| Ramona | Puerto Rican | 33 | F | x | x | 2 | |||

| Alana | Dominican | 19 | F | x | 1 | ||||

| Ada | Mexican | U | F | x | x | x | x | 4 | |

| Naomi | Black | 43 | F | x | x | 2 | |||

| Kristina | Mexican | 20 | F | x | x | 2 | |||

| Amber | Black | 46 | F | x | 1 | ||||

| Terence | Black | 19 | M | x1 | x | 2 | |||

| Inez | Puerto Rican | 35 | F | x | 1 | ||||

| Susan | Black | U | F | x | x | x | 3 | ||

| Junior | Puerto Rican & Nicaraguan | 26 | M | x | 1 | ||||

| Shayna | Black | 19 | F | x | 1 | ||||

| Total | 5 | 10 | 6 | 5 | 11 | 37 | |||

1Terence mentions Jumpstart in his interview but is not a participant.