Values-Engaged Assessment:

Reimagining Assessment through the Lens of Democratic Engagement

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

What is one value that grounds you in your civic engagement work? How are you walking the talk of that value in your assessment work? Or, how might you? And, what both helps and gets in the way of your doing that? These questions were recently posed to service-learning and community engagement (SLCE) faculty and staff gathered for an assessment institute. Answering the first was easy. Collaboration. Reciprocity. Vulnerability. Intentionality. Humility. And on and on. But the second question was, at first, a dead weight in the room. Finally, one participant stood and spoke candidly:

I care about risk-taking. I am always encouraging my students to take risks and embrace the vulnerability that comes along with that. We have to be vulnerable in order to grow. But when I think about my assessment work, vulnerability is the last thing I want. I am not taking risks in that part of my work; I am looking for answers, usually in ways that keep everyone happy. That’s not what I want my students to do, and I really have to look at that.

We believe the SLCE movement as a whole also “really has to look at this”: at the role SLCE values play in SLCE assessment practices.

Zlotkowski’s 1995 essay on the future of SLCE called the movement to focus on achieving academic legitimacy. Since that time, academic legitimacy has become inextricably linked with academic assessment, which now, 20 years later, we need to critically examine and creatively reimagine. We are concerned that the ongoing quest for legitimacy, coupled with uncertainties about funding, often leads SLCE practitioner-scholars to a disempowered and inauthentic relationship with assessment – one in which we find ourselves conforming to the practices of the world around us rather than holding to the values that drew many of us to SLCE. We see this potential tension between our values and our assessment practices as a microcosm of the broader struggles SLCE as counter-normative work faces. It is challenging to live out commitments to democratic engagement in an academic culture and a society often characterized by technocratic tendencies to privilege academic expertise over broad community participation in knowledge creation (Saltmarsh, Hartley, & Clayton, 2009) and by neoliberal (market-driven) imperatives to frame SLCE merely in terms of charity, public relations, or revenue generation (Brackmann, 2015).

Assessment is always undergirded by values, but which values and who determines them? And do we default to them, let ourselves be pressured into alignment with them, or deliberately choose them? Our vision for SLCE is to “walk the talk” of democratic engagement (Clayton et al., 2014; Saltmarsh, Hartley, & Clayton, 2009). Democratic engagement focuses on relationships as much as results and on effectiveness as much as efficiency. It sees all participants in SLCE as co-inquirers and co-creators. It calls for transformative learning and change – in higher education, in communities, and in ourselves. How might we better walk the talk of the values of such engagement in our assessment work, navigating constraints while empowering all stakeholders through critical reflection on values? Realizing this vision, we believe, requires that we go beyond assessing community and campus outcomes by counting participants, hours, or dollars or by reporting levels of satisfaction; it invites us to inquire into qualities of relationships, the transformation of systems, and the empowerment of all partners over time. As we see it, democratic engagement invites us to reimagine assessment.

It is our conviction that the assessment work of SLCE practitioner-scholars can embody and nurture a set of relationships, practices, and modes of inquiry that is potentially transformative of technocratic and neoliberal tendencies in our institutions. To fulfill this potential, we call for what we have begun referring to as “values-engaged assessment” – by which we mean assessment that is explicitly grounded in, informed by, and in dialogue with the (contested) values of SLCE understood and enacted as democratic civic engagement.

We seek to build on promising thinking about assessment that invites focus on process as well as product, questions whose perspectives should be included and what metrics best give voice to them, and prioritizes relationships as much as – if not more than – outcomes. There have been many calls to broaden assessment beyond student learning (the focus of academic assessment) to arenas such as community impact, institutional change, faculty/staff/community learning, and partnership quality. Innovative approaches that attend to multiple stakeholder perspectives and ways of knowing are needed and, indeed, emerging. For example, Guijt (2007) advocates for reforming assessment so that it better supports efforts to build capacities and social movements, shift social norms, and strengthen citizenship and democracy. As another example, the Center for Whole Communities offers tools for impact assessment related to such values as equity, human rights, ecosystem health, and economic vitality.

We share here our experience trying to reimagine assessment in order to surface key possibilities, tensions, and questions. At the 2015 Imagining America (IA) conference, we raised the question of how the organization might think innovatively about assessment, specifically by examining assessment practices and dilemmas explicitly through the lens of values. IA’s research group on “Assessing the Practices of Public Scholarship” (APPS) had earlier identified five core values to which assessment in SLCE ought to attend – collaboration, reciprocity, generativity, rigor, and practicability – and had begun exploring examples that express them. We wanted to advance and nuance this thinking with the broader membership of IA by thinking together about the possibilities and challenges of walking the talk of the values of democratic engagement in assessment practices, especially in contexts that may actively frustrate or contradict them. We share here four conversations from the event that we think help to reimagine assessment.

First, we considered with participants during the conference plenary the question of why we might think assessment needs reimagining. The answers we heard, sampled here, point to the frustrations that may arise when assessment goals and methods are defined for us in narrow ways:

- I’m tired of accounting: counting hours, counting dollars, counting heads.

- I don’t believe in mandates from above – I believe in inclusive processes that mandate from within, that help us identify and live into our mandates.

- I am not in the game only to document and justify my own existence. I am in this because I care about contributing to change.

- I don’t need more boxes to check. I need more honest conversations that help us deepen the work itself.

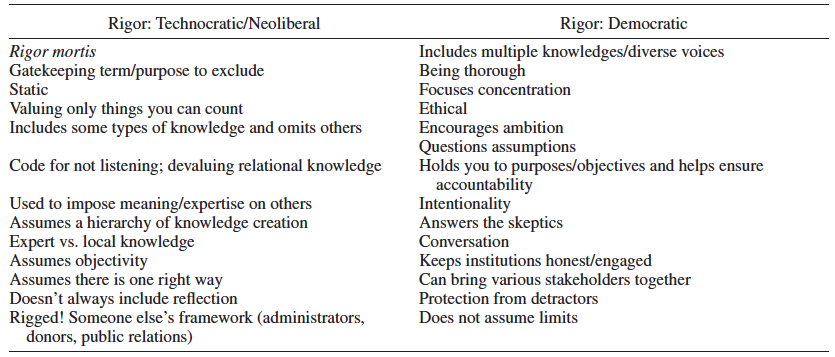

Second, building from these concerns, we explored how, concretely, we might reimagine assessment. We invited participants to articulate collaboratively the meanings of one of the five values that most readily come to mind in a technocratic or neoliberal paradigm and then to reimagine that same value through the lens of democratic engagement. Table 1 expresses the contrast generated around the value of “rigor.”

Thus, it seems that while rigor may be taken to imply the expression of technocratic values – that is, prioritizing the knowledge creation of “experts,” mandating quantitative analysis, assuming objectivity, and devaluing the messiness of dialogue with multiple knowledges – it can also enhance more democratic processes of questioning assumptions and seeking input from multiple perspectives in the pursuit of common goals. Since any one value may, it seems, invoke technocratic, neoliberal, and democratic paradigms, a necessary aspect of reimagining assessment is critically reflective examination of the potential meanings of the values themselves in all of their nuances.

Third, we brought to the discussion at the conference an insight we found very resonant with our experience of being torn between the democratic values we want to enact and often technocratic, neoliberal norms we feel pressured to accommodate in assessment. Parker Palmer’s latest book, Healing the Heart of Democracy (2011), explores how tensions between our values or aspirations and the realities of our everyday lives can become so frustrating that we can give up or shut down as a result. In this condition, we can fail to stand by our convictions and thus lose our voices. One of us shared a recent example of feeling disempowered in a conversation with an assessment specialist on campus. The specialist was resisting a proposal to involve faculty in examining artifacts from SLCE courses in order to begin identifying shared learning goals across disciplines. The specialist advised instead, “Don’t ask them what to measure; tell them!” – contradicting the values of collaborative inquiry that fueled the proposal and that grounded the pedagogy. Palmer suggests we need to develop capacities to hold such tensions in creative ways and stay open to insights thereby generated. We discussed with conference participants the ways that engaging in critical reflection on our assessment practices in light of our values allows for co-creative processes whereby we are more likely to navigate these tensions effectively, be open to new generative insights, and resist tendencies to “shut down.”

Fourth, we explored the possibility that values-engaged assessment might, in practice, begin to find its footing through the adaptation of existing rather than (only) the creation of new tools and instruments. We started with version II of the Transformational Relationship Scale (TRES; TRES I was published by Clayton, Bringle, Senor, Huq, & Morrison, 2010; TRES II is available upon request), which has several features that align with our five named values. With its purpose being to support inquiry into the transactional or transformational nature of relationships in SLCE partnerships and thus advance understanding and improving partnership dynamics, TRES is inherently focused on collaboration, generativity, and reciprocity. TRES demonstrates practicability through its structure as a short, 13-item scale as well as rigor (as conceived in the right-hand column of Table 1) in that it gathers desired partnership qualities along multiple dimensions and thereby supports focused, constructive dialogue among partners about changes they want to make moving forward. However, applying the values-engaged lens highlights the fact that this tool was developed by faculty drawing on the literature, not co-created with students and community members, and that to date it is not readily accessible by non-academics. The use of TRES, or any other practical approach to assessment, then, may well be complicated by a mix of “fit” and “mis-fit” with the values of democratic engagement; the extent of this is influenced by our choices in designing and undertaking it. Without reflecting intentionally and critically on the values it embodies – in its creation, its use, its products, its goals, and its adaptation – a democratic form of assessment is unlikely.

These conversations highlight a range of complexities in living out our values, and in the interest of transparency, we question whether “values-engaged assessment” is, in fact, the best term to express what we are after: Is it sufficiently explicit regarding democratic engagement as the focal point of our values? Is “justice-oriented,” with its many complex and sometimes conflicting relationships with democratic principles, a better characterization of the reimagining we intend? More fundamentally, might we think of a values-engaged approach as applying more appropriately to any set of values – calling for intentionality and criticality in enacting them in assessment, whatever they may be?

Indeed, foundational to democratic engagement is the notion of criticality, or attentiveness to what is easily taken for granted as given, and a corresponding commitment to shine light on missing, often suppressed, alternatives. Rather than proposing a singular interpretation of any specific set of SLCE values, therefore, we are exploring here a deeply self-reflective and intentional way of being in assessment in which we maintain a critical, questioning, and open orientation toward our values and toward our own enactment of them. Our use of the word “engaged” in “values-engaged assessment” is intended to express our own particular focus on democratic engagement: Assessment as we are conceptualizing it here exists in mutually-formative relationship with such democratic values as co-creation, shared power, inclusivity, asset-orientation, common good, and justice.

The self-reflection and criticality that characterize a values-engaged approach to assessment demand that we acknowledge that the practice of democratic and transformational forms of assessment is not without its limitations and tensions. As an aid to refining this approach, therefore, we pose here four questions for further exploration with the broader community of SLCE practitioner-scholars.

Question 1: A values-engaged approach necessarily involves a critique of the values driving assessment. As our discussion of “rigor” revealed, our values, no matter how sacred, are always at risk of invoking concepts and practices that are counter to the transformative goals of democratic engagement and thus must be subject to continual re-examination and perhaps negotiation. How might we best engage collaboratively in such ongoing critique?

Question 2: The many values held dear within the SLCE movement may seem to contradict each other in practice. Valuing (and documenting) impact can be at odds with valuing humility and with attending as much to process as to product, for example. How can we view these tensions as a generative mechanism by which new thinking and counter-normative approaches to assessment, or to SLCE, can be cultivated?

Question 3: A values-engaged approach can be time-consuming, resource-intensive, and personally risky. The amount and intensity of critical reflection and candid communication associated with democratic engagement can pose significant logistical, resource, and interpersonal challenges – making clear the appeal of more traditional and perhaps more efficient approaches to assessment. We do not advocate abandoning the value of efficiency, but we also do not want to uncritically sacrifice other values to achieve it. And, when confronted with the time and effort demands of democratic engagement, we do not want to simply fall back on approaches that are expedient but demand less in the way of vulnerability and dialogue across difference without taking into account what might be compromised. How might a values-engaged approach nurture generative collaborations among SLCE partners that are cost- and time-efficient and also help us learn to take interpersonal risks?

Question 4: Values-engaged assessment offers no one method, no one-size-fits-all model of assessment. A values-engaged approach favors processes that are intentionally purpose-driven, collaborative, empowering, dynamic, and context-dependent. As a result, each assessment method will take shape based on the specifics of each project and the values embraced and negotiated by all partners involved. Nonetheless, we as practitioners crave methodological guidance that goes beyond general principles such as co-creative reflection and intellectual integrity, however important they may be. What sorts of guidelines, structures for dialogue, models, and other forms of support might we fashion together in order to give clear aid in the challenging work of values-engaged assessment while not foreclosing generative processes for context-specific and inclusive engagement with values?

Democratic engagement involves both co-creative processes among all partners – which underlie these questions – and public purposes, for example social justice. Values speak to and can be brought to life in both. We are eager to have a dialogue within the SLCE community about the ways our assessment approaches can critically and creatively examine and enact the values of democratic engagement. In issuing this invitation, we are reminded of a folklore story that periodically makes its way through the SLCE community (shared often, for example, by Russ Edgerton and Bob Bringle):

Two medieval stonemasons are working at a construction site. One of them, upon being asked what he is doing, replies, “I am squaring a stone.” The other answers “I am building a cathedral.” Same task – two very different relationships with the work and perspectives on its purpose.

It is our hope and intention that the ongoing development of values-engaged assessment will proceed in the spirit of – and contribute to the flourishing of – “cathedral building.”

It is essential for the future of the movement – indeed, possibly for high-impact educational practices, publicly engaged scholarship, and social change initiatives more generally – that the work of assessment self-consciously have a sense of purpose that is equally as significant and high stakes as that of the SLCE movement. Claiming and holding tightly to such a sense of purpose as part of deeply co-creative processes undertaken by the full range of participants in SLCE can, we believe, empower and embolden us – helping us to move beyond frustration with and alienation from assessment, to live out the values of democratic engagement in assessment, and to expand opportunities for democratic knowledge creation and inclusive dialogue. In this way, assessment can better support forms of SLCE that build a more democratic and just society.

Notes

The authors are grateful to the participants in the preconference workshop and plenary session we facilitated at the 2015 Imagining America conference. Their ideas, questions, and concerns significantly shape our work. We are also especially thankful for the contributions of Imagining America’s Assessing the Practices of Public Scholarship (APPS) team who have grounded much of our thinking and who contribute to ongoing efforts to reimagine assessment. We also are indebted to Susan Schoonmaker, APPS research assistant, for support of our collaborations.

References

- Brackmann, S. (2015). Community engagement in a neoliberal paradigm. Journal of Higher Education Outreach and Engagement, 19(4), 115-146. Retrieved from http://openjournals.libs.uga.edu/index.php/jheoe/article/viewFile/1533/892

- Center for Whole Communities. Whole measures. Retrieved from http://wholecommunities.org/practice/whole-measures/.

- Clayton, P. H., Bringle, R. G., Senor, B., Huq, J., & Morrison, M. (2010). Differentiating and assessing relationship in service-learning and civic engagement: Exploitative, transactional, or transformational. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 16(2), 5-22. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0016.201{~?~J: I couldn’t move the word “from” to the prior line.}

- Clayton, P. H., Hess, G., Hartman, E., Edwards, K. E., Shackford-Bradley, J., Harrison, B., McLaughlin, K. (2014). Educating for democracy by walking the talk in experiential learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 6, 3-36. Retrieved from https://www.missouriwestern.edu/appliedlearning/wp-content/uploads/sites/206/2015/02/JALHE14.pdf

- Guijt, I. (2007). Assessing and learning for social change: A discussion paper. Brighton: Institute of Development Studies. Retrieved from http://www.ids.ac.uk/files/dmfile/ASClowresfinalversion.pdf

- Saltmarsh, J., Hartley, M., & Clayton, P. H. (2009). Democratic engagement white paper. Boston: New England Resource Center for Higher Education. Retrieved from http://futureofengagement.files.wordpress.com/2009/02/democratic-engagement-white-paper-2_13_09.pdf

- Zlotkowski, E. (1995). Does service-learning have a future? Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 2, 123-133. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0002.112

Authors

JOE BANDY ([email protected]) is assistant director of the Center for Teaching and affiliated faculty in Sociology at Vanderbilt University, where he has worked since 2010. In his administrative roles, he supports instructional and professional development of faculty in Vanderbilt’s many social science colleges, departments, and programs. He also supports pedagogical innovation and organizational development across the university in his specialty areas of SLCE, critical pedagogy, diversity and equity, and environmental education. As a sociologist, he has researched widely and taught on issues related to social movements, environmental justice, class relations, economic development, and community building.

ANNA SIMS BARTEL ([email protected]) serves as Cornell University’s associate director for Community-Engaged Curricula and Practice in the Office of Engagement Initiatives (part of Engaged Cornell). Once described as “part activist, part administrator, and part academic,” Anna earned her Ph.D. in Comparative Literature at Cornell. Anna’s background includes faculty work, consulting, and public humanities initiatives as well the development of community-engagement centers at several higher education institutions in cold, white places (upstate New York, Maine, and Iowa). Her current research interests are broad and include civic poetry; the U.S. agrarian novel; and of course civic engagement. Her favorite publication (“Why Public Policy Needs the Humanities, and How”) appeared in 2015 in the Maine Policy Review.

PATTI H. CLAYTON ([email protected]) is an independent consultant and SLCE practitioner-scholar (PHC Ventures) as well as a senior scholar with IUPUI and UNCG. Her current interests include civic learning; the integration of SLCE and relationships within the more-than-human world; walking the talk of democratic engagement as co-inquiry among all partners; and the power of such “little words” as in, for, with, and of to shape identities and ways of being with one another in SLCE. Related to assessment per se, she supports integrated design of SLCE that aligns goals, strategies, and assessment (focused on learning, community impact, partnership quality, etc.); and she works with individuals, programs, and institutions to build capacity for authentic assessment.

SYLVIA GALE ([email protected]) directs the Bonner Center for Civic Engagement (CCE) at the University of Richmond. She was the founding director of Imagining America’s Publicly Active Graduate Education Initiative (PAGE) and since 2009 has co-chaired IA’s initiative on “Assessing the Practices of Public Scholarship,” (APPS) which explores and advances assessment practices aligned with the values that drive community-engaged work. She is committed to co-creating opportunities for transformative liberal arts learning far beyond traditional institutional boundaries and has published on innovative assessment, engaged graduate education, and the power of institutional intermediaries to effect change.

HEATHER MACK ([email protected]) is a planning, tracking, and assessment consultant to higher education institutions, international and domestic NGOs, and philanthropic foundations. She can often be found facilitating the adaptation of highly effective practices to the unique contexts and values of SLCE and social change programs at work on the ground. Her current interests include promoting an SLCE assessment culture that uplifts and enhances SLCE endeavors rather than drains or diminishes them, and fostering SLCE practitioners-scholars’ autonomy and agency to ensure the assessments of their work embody the fundamental standards of utility, propriety, accuracy, feasibility, and accountability.

JULIA METZKER ([email protected]) joined Stetson University as executive director for the Brown Center for Faculty Innovation and Excellence in June, 2016 after serving as director of Community-based Engaged Learning and professor of Chemistry at Georgia College. She received a B. S. from The Evergreen State College (where she learned first-hand the value of a transformative liberal arts education) and a doctoral degree from the University of Arizona. She co-founded the Innovative Course-building Group (IC-bG), an inclusive collaboration of higher educators that provide professional development around issues of learning. Her interests include using civic issues to design learning experiences, developing of high-impact pedagogies, and advancing equity in higher education.

GEORGIA NIGRO ([email protected]) is professor of psychology at Bates College where she teaches courses in community-based research methods and works closely with the college’s Harward Center for Community Partnerships and regional Campus Compact offices. She joined the Bates faculty after receiving her Ph.D. at Cornell, where she worked with the Consortium for Longitudinal Studies to carry out some of the early evaluations of preschool programs that led to widespread support for Head Start. These early lessons in bridging the domains of research, practice, and policy serve her well today.

MARY F. PRICE ([email protected]) is an anthropologist and director of Faculty Development at the IUPUI Center for Service and Learning. Mary works with faculty, graduate students, and community members as a thought partner and critical friend to strengthen curricula through authentic partnership, facilitate the creation of actionable knowledge, and enact institutional change grounded in the principles of democratic engagement. Her scholarly interests include community-campus partnerships as craft, community-engaged learning environments, and the social relations of production in higher education.

SARAH E. STANLICK ([email protected]) is the founding director of Lehigh University’s Center for Community Engagement and a professor of practice in Sociology and Anthropology. She previously taught at Centenary College of New Jersey and was a researcher at Harvard’s Kennedy School, assisting the U.S. Ambassador to the United Nations, Samantha Power. She has published in journals such as The Social Studies and the Journal of Global Citizenship and Equity Education. Her current interests include inquiry-based teaching and learning, global citizenship, transformative learning, and cultivating learner agency.