The Counter-Normative Effects of Service-Learning: Fostering Attitudes toward Social Equality through Contact and Autonomy

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Power dynamics are implicated in intergroup prosocial behavior (Nadler & Halabi, 2015). This research investigated two factors that influence the effect of intergroup prosocial behavior on views of social equality: amount of direct intergroup contact and type of helping. Students in a social psychology course (N = 93) were randomly assigned to a service-learning group or to a control group. The service-learning group was further subdivided into an autonomy-oriented helping group or a dependency-oriented helping group. After participating in approximately 19 hours of community service over nine weeks, service-learners had more positive views of social equality compared to the control group. This effect was strongest in autonomy-oriented helpers who had high levels of direct intergroup contact. The implications and mechanisms of service-learning as a form of counter-normative intergroup prosocial behavior are discussed.

Prosocial behavior is an integral, adaptive component of human functioning. Prosocial behavior can take many forms, including spontaneous assistance offered in emergencies, sustained community service, and the billions of dollars given each year in philanthropy. Communities richly benefit from the time, resources, and talents of prosocial people. Prosocial behavior also benefits helpers. Prosocial people become happier, healthier, and experience a greater sense of purpose in life through their service to others (Piliavin, 2003; Smith & Davidson, 2014).

Prosocial behavior that is “intergroup” (i.e., that occurs across different social groups) has the added potential benefit of increasing people’s exposure to diverse group members and may result in an increased preference for social equality. Brown (2011a, 2011b) found that participating in service-learning, a form of intergroup prosocial behavior (IPB), reduced social dominance orientation (Pratto, Sidanius, Stallworth, & Malle, 1994). Social dominance orientation is an anti-egalitarian attitude that includes one’s preference for group-based social hierarchy and support for discrimination against lower status groups (Sidanius & Pratto, 1999). The conditions under which these benefits of intergroup prosocial behavior are most likely to accrue have not yet been explored. The present study examines two variables hypothesized to influence the relationship between IPB and attitudes toward social equality: the amount of direct, personal contact that groups have with one another and the type of assistance offered. We begin with a brief review of the literature to provide the theoretical context for this study’s design and hypotheses, focusing on the intimate relationship between IPB and power.

Power dynamics are frequently implicated in IPB. The group offering assistance (i.e., the “helpers”) may possess some resource that the other group (i.e., the “recipients”) lacks, and thus the transaction is founded on a status differential. The Intergroup Helping as Status Relations Model (IHSR; Nadler, 2002; Nadler & Halabi, 2006) is the most well-developed theory in social psychology to describe the connection between IPB and power dynamics. The model is based on the assumption that pervasive legitimation of social inequality (Costa‐Lopes, Dovidio, Pereira, & Jost, 2013) operates within IPB, such that rather than promote equality, prosocial behavior frequently serves the ironic function of keeping high status and low status groups in their respective places (Cunningham & Platow, 2007; Halabi, Dovidio, & Nadler, 2008; Jackson & Esses, 2000; Nadler & Chernyak-Hai, 2014).

The IHSR differentiates between two types of prosocial behavior: autonomy-oriented and dependency-oriented. Autonomy-oriented helping is aimed at assisting the recipient to help him or herself by providing a partial solution such as tools that can be used to resolve the issue or need. In contrast, dependency-oriented helping provides a full solution to the recipient’s need. Autonomy-oriented helping reflects the perspective that the recipient is autonomous and efficacious, whereas dependency-oriented helping reflects a more negative view of the recipient as dependent and incapable. The IHSR predicts that higher status groups will be most apt to provide dependency-oriented help to lower status groups. Dependency-oriented help keeps lower status group dependent and further entrenches existing social hierarchy. By extension, it legitimates and cements the prejudicial attitudes of high status group members toward low status group members as incompetent and weak (Nadler, 2002; Nadler & Chernyak-Hai, 2014; Nadler & Halabi, 2015).

While the IHSR model is useful for understanding typical instances of IPB, it does not apply to all forms of IPB. In a series of studies, Brown (2011a, 2011b) found that college students randomly assigned to participate in service-learning had a greater preference for social equality after the experience than a control group, as indexed by reduced social dominance orientation scores.

Service-learning is defined as:

a course-based, credit-bearing educational experience in which students (a) participate in mutually identified and organized service activities that benefit the community, and (b) reflect on the service activity in such a way as to gain further understanding of course content and an enhanced sense of personal values and civic responsibility (adapted from Bringle & Hatcher, 1996, p. 222).

Service-learning is an atypical, “counter-normative” form of IPB for a variety of reasons (Clayton & Ash, 2004). Most salient to this research, it is collaborative and democratic (Bringle, Reeb, Brown, & Ruiz, 2016). Both groups participate in defining the need as well as the nature and parameters of the interaction. Further, service-learning is predicated on the assumption that prosocial interactions are reciprocal rather than unidirectional. Both groups learn from one another, and both groups benefit (i.e., are served) from the interaction.

Although Brown’s (2011a, 2011b) research shows that IPB in the form of service-learning can promote more favorable attitudes toward social equality amongst high status group members, the conditions under which this effect is most likely to occur have not yet been explored. The contact hypothesis (Allport, 1954; Pettigrew & Tropp, 2006) suggests that direct, personal contact facilitates more positive intergroup attitudes. Therefore, we predict that IPB with high levels of direct contact between groups is likely to produce the best effects (Koschate, Oethinger, Kuchenbrandt, & Van Dick, 2012). Further, research on the contact hypothesis finds that the benefits of contact are enhanced when the groups have common goals and are of equal status. Helping that is autonomy-oriented is much more likely to fit with these conditions than dependency-oriented helping. In autonomy-oriented helping, both groups share the goal of genuinely and more permanently improving the condition of the recipient group; in addition, autonomy-oriented helping relies on an agentic, positive view of the recipient, which deemphasizes status differentials between groups.

In the present study, college student participants were randomly assigned to a service-learning group or control group that did not take part in community service. Within the service-learning condition, participants were subdivided into either autonomy- or dependency-oriented helping groups, and the direct contact hours that service-learners spent with the clients at the community sites was measured. While it would have been ideal to randomly assign service-learners to high and low levels of direct contact, it was not possible to achieve this without compromising the specific needs of the various service sites, which often varied from week-to-week. The dependent measure was scores on the Equality and Social Responsibility Orientation scale (ESRO; Bowman & Brandenberger, 2012), selected because it assesses attitudes toward social equality and the importance of social responsibility, and has been validated in previous research examining the outcomes of college diversity experiences including service-learning (Bowman & Brandenberger; Bowman, Brandenberger, Mick, & Smedley, 2010).

Our first hypothesis was that the service-learning condition would affect participants’ attitudes. We predicted that those engaged in autonomy-oriented helping would develop more positive attitudes toward social equality than those engaged in dependency-oriented helping, and that both service-learning groups would have more positive attitudes toward social equality than the control group. Our second hypothesis was that helping type would interact with direct intergroup contact to predict attitudes toward social equality. Specifically, we expected that those in autonomy-oriented placements would be the most benefited by increased direct contact with clients at their service sites.

Method

Participants

Ninety-three students enrolled in a social psychology course at a small private university in an urban center of the Northwestern United States participated in exchange for extra course credit. Using random assignment to conditions, 47 of the participants (8 men, 39 women) were assigned to the service-learning condition, while 46 of the participants (6 men, 39 women, 1 not identified) were assigned to the control condition. The gender imbalance in the sample (83.9% women) was likely attributable to the high concentration of psychology majors in the course. At this university (and consistent with nationwide trends; Willyard, 2011), women comprise the preponderance of psychology majors. Seven other students enrolled in the course chose not to participate in the study. Three of the non-participating students were in the service-learning condition, and four were in the control condition. The mean age of participants was 20.68 (SD = 1.66), with the following racial/ethnic self-identification: White or European American, n = 66, Asian or Asian American, n = 8, Hispanic or Latino, n = 6, American Indian or Alaskan Native n = 4, Black or African American, n = 2, and Other, n = 5. The sample had similar numbers of non-Hispanic white/European Americans (71%) to the university population at the time of the study (68%), and to the surrounding metropolitan area during the most recent available census (year 2010; 72.7%).

Service-Learning and Control Group Procedures

On the first day of the academic quarter, students were informed of the service project component of the course. They were told that understanding the issues in one’s local community was critical to informed citizenship and that it would help them to more deeply understand several of the concepts presented in the course. They were also told that the instructor was investigating the effectiveness of different pedagogical techniques for having students learn about community issues and course concepts, and they were randomly assigned to one of two groups: “service-learning” or “service research” (control). Students were informed that both groups were designed to take an equivalent amount of time, approximately 18 hours across nine weeks. Both required equal amounts of coursework (i.e., weekly journal entries and a final paper discussing their service or research project).

Participants in the service-learning group were subsequently randomly assigned to receive one of two lists of community organizations with service placements. One of the lists had autonomy-oriented placements to choose from, and one of the lists had dependency-oriented placements. The lists contained several community organizations, including food banks, nursing homes, homeless shelters, and urban youth tutoring programs. The average total time that students reported being at their service sites was 19.17 hours (SD = 4.97), and the average amount of direct contact they reported with the organizations’ clients was 15.40 hours (SD = 4.83).

The research team classified the service-learning sites as autonomy- or dependency-oriented based on descriptions of the placements provided by the community organizations. An example of an autonomy-oriented placement was the Empowering Youth and Family Outreach organization, which provides tutoring and mentoring to at-risk youth. A dependency-oriented placement involved providing basic care to residents at a nursing facility (e.g., helping serve food to residents). There were 30 service-learners in autonomy-oriented placements and 17 service-learners in dependency-oriented placements. The unequal distribution of placements was due to the greater number of university partnerships with autonomy-oriented organizations, and therefore more placements were available at those sites. Nevertheless, assignment to helping type was randomized to reduce selection bias. At the end of the quarter, service-learners were asked to indicate whether they felt their service was more autonomy- or dependency-oriented (definitions were provided), and their judgments aligned with those of the research team. The number of service hours was not strictly controlled and direct contact was not randomly assigned, but a post-hoc analysis revealed no significant differences between service groups regarding the amount of total service time (p = .20) or hours in direct contact with clients (p = .51).

Even though service-learning activities may involve one-on-one interactions, service-learning experiences are considered to be an intergroup experience because the service-learning context makes group affiliations salient, and thus intergroup dynamics apply (Turner, Hogg, Oakes, Reicher, & Wetherell, 1987; van Dijk & van Engen, 2013). The clients at the service sites were different than the service-learners in a variety of salient demographic characteristics. Student service-learners were of traditional college age, in relatively good health, and most were white and of middle or upper middle socio-economic status. The clients of the service organizations included persons who were children, elderly, in poverty or working class, homeless, and ethnic minorities. Students chronicled their service experiences each week in a journal, using the structure of the DEAL model (Ash & Clayton, 2009).

The service research (control) group was given a list of weekly research topics from their instructor to investigate. For example:

This week your journal entry will be about food insecurity, poverty, and racism. Research this topic using the Internet, library, or other sources. Below are some examples of the types of things that you could report on, but ultimately it is up to you what you choose to include: What is the poverty rate in your city? In the United States? What income level qualifies a person to be considered living in poverty? What are the characteristics of those in poverty in this region (e.g., gender, race/ethnicity, age, etc.)? What is food insecurity? In your city, what forms of assistance are available to people who are facing food insecurity? Consider investigating specific organizations such as Solid Ground. What is their mission, what services do they provide, and how are they funded? How do racism and other forms of prejudice and oppression relate to poverty? Did you encounter anything particularly interesting or surprising in your research? What new perspectives or ideas did you encounter as a part of your research? What connections are you able to draw between classroom learning (e.g., theories on the sources of prejudice, stereotyping, and reducing prejudice) and your research?

Both the service-learning and the service research (control) groups wrote and submitted weekly journal entries, engaged in class discussion on service and its connection to course content, and wrote a final paper relating what they had learned about service to the course material. The two groups were as similar as possible except for the experiential aspect of serving in the community.

Study Procedure and Materials

The study measures were given to students during the final week of the quarter, after their service projects were completed. Students were asked some standard demographic questions, and a few questions about their service placement (for the service-learning group). Service-learners were asked to indicate the name of their service-learning site, how much total time they spent during the quarter at the service site, and how much time they spent in direct contact with clients at the site. Additionally, they were asked to classify their service as dependency-oriented (i.e., whether their service was geared to provide a full solution to the clients’ needs, without much input from the client), autonomy-oriented (i.e., providing clients with tools to help address their own needs), neither, or both.

All participants received the primary assessment of Equality and Social Responsibility Orientation scale (ESRO; Bowman & Brandenberger, 2012). Bowman and Brandenberger define ESRO as “a set of attitudes and values pertaining to the recognition and denunciation of societal inequality and the importance placed on helping others” (p. 185). Their research finds that positive diversity experiences predict ESRO scores. The ESRO is comprised of seven subscales, which were presented in counterbalanced order: Responsibility for Improving Society (Nelson Laird, Engberg, & Hurtado, 2005), Openness to Diversity (Pascarella, Edison, Nora, Hagedorn, & Terenzini, 1996), Empowerment View of Helping (Michlitsch & Frankel, 1989), Situational Attributions for Poverty (Feagin, 1971), Self-Generating View of Helping (Michlitsch & Frankel, 1989), Belief in a Just World (Dalbert, Montada, & Schmitt, 1987), and Social Dominance Orientation (Pratto et al., 1994). The latter three subscales were reverse-coded, such that higher scores indicated greater equality and social responsibility orientation. All subscales were z-scored and averaged into a single, overall index of ESRO. The measure demonstrated acceptable internal reliability (α = .73).

Participants were told that this study was investigating how experiences in social psychology courses relate to students’ attitudes toward other people and social groups. Participation was voluntary and extra credit was awarded for participation. An alternative extra credit assignment was provided to avoid coercion. The survey was administered during the tenth week of the quarter. Students received a full debriefing on the last day of the course.

Results

The first hypothesis that service condition [Autonomy-Oriented Service-learning (AOSL), Dependency-Oriented Service-learning (DOSL), and Control] would influence ESRO was tested with a 3-group, one way ANOVA. There was a significant main effect, F(2, 90) = 20.33, p < .001, ηp2 = .31, and follow-up analyses confirmed that the control condition had significantly lower ESRO scores (M = -.32, SD = .58) than the DOSL condition (M = .06, SD = .36; p = .01) and the AOSL condition (M = .45, SD = .50; p < .001). Additionally, ESRO scores were lower in the DOSL condition than in the AOSL condition (p = .02). Thus, as predicted, service-learners developed more positive attitudes toward social equality than the control group, with the autonomy-oriented helpers displaying the most positive attitudes of the three groups.

Post-hoc analyses examining the seven subscales of the ESRO individually as dependent variables revealed that all seven 3-group, one-way ANOVAs had significant overall F values (all p’s < .05), consistent with the composite ESRO results described above. The specific pattern of differences between the AOSL, DOSL, and Control groups was the same as described above (i.e., the three groups significantly differed from one another, with AOSL the most positive, DOSL in the middle, and Control the least positive) for all of the individual subscales with the exception of the Responsibility for Improving Society subscale. In this case, both DOSL and AOSL groups were superior to the Control condition (p’s < .01) but not different from one another (p = .89). In sum, use of the overall ESRO composite was a good representation of its constituent components.

To examine the second hypothesis that helping type would interact with direct contact to predict ESRO, we used a moderated regression analysis, with helping type (AOSL and DOSL) and direct contact hours as predictors. Direct contact hours was treated as a continuous predictor, and was mean-centered prior to the analysis. Helping type was coded as: AOSL = -1, DOSL = 1. An interaction term was modeled by creating a cross-product. There was a main effect of helping type, F(1, 43) = 6.12, p = .02, ηp2 = .13, accompanied by a main effect of direct contact, F(1, 43) = 6.06, p = .02, ηp2 = .12, and a helping type by direct contact interaction, F(1, 43) = 3.91, p = .048, ηp2 = .08.

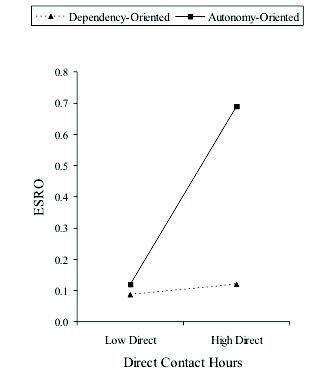

Simple effects tests to examine the nature of the interaction revealed that direct contact had no effect on ESRO scores among those in the DOSL condition (t < 1), but there was a significant effect of direct contact among those in the AOSL condition, t(43) = 3.74, p = .001. Additionally, helping type had no effect when direct contact hours were low (one standard deviation below the mean; t < 1), but a significant effect when direct contact hours were high (one standard deviation above the mean; t(43) = 3.05, p = .005). The nature of the effects can be seen in Figure 1.

A post-hoc moderated regression analysis that examined the effect of non-contact service hours (i.e., hours spent doing administrative/clerical work that did not involve direct contact with clients) found that the only significant predictor of ESRO scores was helping type, F(1, 43) = 5.47, p = .02, ηp2 = .11. Independent of how many non-contact service hours service-learners spent at their organizations, those in AO service sites (M = .42) had higher ESRO scores than those in DO service sites (M = .09). In short, non-contact service hours did not predict attitudes toward social equality.

Discussion

Our findings supported both hypotheses. Participants who engaged in service-learning had more positive attitudes toward social equality than did a control condition (replicating previous research by Brown, 2011a, 2011b), and this effect was strongest amongst service-learners in autonomy-oriented placements. Further, direct contact hours interacted with helping type, such that higher levels of direct contact with the clients of community organizations increased positive attitudes toward social equality, but only amongst service-learners engaged in autonomy-oriented helping.

These findings extend our knowledge of how IPB and views on power are related in counter-normative IPB situations such as service-learning. Nadler and colleagues’ IHSR model (Nadler, 2002; Nadler & Halabi, 2006, 2015) delineates what higher status groups do in typical IPB situations, when they are free to choose what type of help to offer lower status groups. In these instances, they are most likely to provide dependency-oriented helping, which has the consequence of maintaining status hierarchies and reinforcing the prejudicial attitudes that endorse such hierarchies. However, what happens when a higher-status group is assigned to participate in autonomy-oriented helping? We found that participation in autonomy-oriented helping created greater endorsement of social equality, and that this effect was most pronounced when service-learners had higher levels of direct intergroup contact.

While the mechanisms and benefits of contact in improving prejudicial attitudes are well-documented, less is known about the benefits of participation in autonomy-oriented helping. Research by Nadler and Chernyak-Hai (2014; Study 4) found that low status persons who requested autonomy-oriented help were viewed as more efficacious and motivated than those who sought dependency-oriented help, and their needs were perceived as transient rather than chronic. Perhaps in our study, assigning service-learners to provide autonomy-oriented help created a more favorable impression of the clients at the community organizations, thus reducing some of the initial status differential. Also, it is possible that engaging in autonomy-oriented helping triggers a self-perception process (Bem, 1967) wherein participants come to believe that what they are doing (i.e., IPB that reduces status hierarchies) is appropriate and desirable, thus leading to the development of more positive attitudes toward social equality.

There were some limitations in our study that warrant consideration. The participants in this study were primarily young white women from a private college. The homogenous demographic of the sample limits its external validity. However, this sample represents a relatively privileged demographic, and privileged populations might be especially benefited by having their views on social equality challenged. Second, experimental control and uniformity were reduced because the experimental manipulation of service-learning took place in a naturalistic, field setting rather than in a lab. Participants in the service-learning condition served at a variety of placements with a variety of groups doing a variety of tasks. Despite this variability, serving still had significant effects on views of social equality, and autonomy-oriented placements still proved superior to dependency-oriented placements. Presumably, the variability or “noise” would weaken the power of this investigation to detect effects. A third limitation is that the amount of direct contact was not experimentally manipulated, but rather was measured, making it difficult to draw causal conclusions about its effect on attitudes toward social equality. However, participants were generally not in control of this variable. They did not choose how much time they spent with clients; rather, the service site supervisors were responsible for assigning tasks. This mitigates the possibility that participants who already had favorable views toward social equality would choose to spend more time in direct contact with clients of the organization.

While research on the IHSR has provided valuable insights into key variables (e.g., legitimacy and stability of status relations, threats to social dominance and social identity, type of helping) involved in the power dynamics of typical IPB, much is left to learn about the process and outcomes of IPB that is counter-normative. Extant research is encouraging. Help is more welcome by recipients when it is autonomy-oriented, and autonomy-oriented helping is more likely to foster reconciliation between groups (Fisher, Nadler, Little, & Saguy, 2008; Stürmer & Snyder, 2010). Service-learning is one type of counter-normative helping experience that appears to have beneficial effects on intergroup attitudes and relations (O’ Grady, 2000; Rosner-Salazar, 2003). Although service-learning has received a fair amount of study, most of this research has used qualitative or non-experimental quantitative methods, rendering causal conclusions elusive (Bringle, Phillips, & Hudson, 2004; but see Brown 2011a, 2011b for exceptions).

In addition to service-learning, other forms of counter-normative IPB should be examined, particularly instances where higher status groups spontaneously choose to offer autonomy-oriented help to lower status groups. Research on motives for intergroup helping (van Leeuwen & Täuber, 2012) is a fruitful starting point. Although IPB by high status groups is at times guided by a sense of shared community and civic engagement (Omoto, Snyder, & Hackett, 2010) or core personal values such as generosity or social justice, more egoistic concerns such as impression-management can also be motivating (van Leeuwen, & Täuber, 2010). Different motivations for IPB may well have different implications for intergroup power dynamics.

Another related model that future research on the outcomes of IPB might consider is Morton’s (1995) work on community service paradigms and subsequent researchers’ analyses of his approach (Bringle, Hatcher, & McIntosh, 2006; Moely, Furco, & Reed, 2008). The description of charity, project, and social change types of service has some overlap with the IHSR’s types of helping (i.e., roughly, the charity paradigm has some overlap with a dependency orientation and the social change paradigm has some overlap with an autonomy orientation); however, Morton’s model emphasizes a more macro-level view of the service rather than perceptions of the population or person being served.

The present study found that being assigned to engage in autonomy-oriented helping, combined with higher levels of direct intergroup contact, was the best recipe for improving service-learners’ endorsement of social equality and social responsibility. Given that higher status groups are inclined to give dependency-oriented help to lower status groups, and given that people are inclined to affiliate with similar others rather than with outgroups, compiling the full list of ingredients for this recipe will require effort, intentionality, and a clearer understanding of the antecedents and mechanisms of counter-normative IPB.

References

- Allport, G. W. (1954). The nature of prejudice. Cambridge, MA: Addison-Wesley.

- Clayton, P. H., & Ash, S. L. (2009). Generating, deepening, and documenting learning: The power of critical reflection in applied learning. Journal of Applied Learning in Higher Education, 1(1), 25–48. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/1805/4579

- Bem, D. J. (1967). Self-perception: An alternative interpretation of cognitive dissonance phenomena. Psychological review, 74(3), 183–200. Doi: 10.1037/h0024835

- Bowman N. A. & Brandenberger, J. W. (2012). Experiencing the unexpected: Toward a model of college diversity experiences and attitude change. The Review of Higher Education,35, 179–205. Doi: 10.1353/rhe.2012.0016

- Bowman N. A., Brandenberger, J. W., Mick, C. S., & Smedley, C. T. (2010). Sustained immersion courses and student orientations to equality, justice, and social responsibility: The role of short-term service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 17(1), 20–31.

- Bringle, R. G., & Hatcher, J. A. (1996). Implementing service learning in higher education. Journal of Higher Education, 67, 221–239. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/2943981.

- Bringle, R. G., Hatcher, J.A., & McIntosh, R. E. (2006). Analyzing Morton’s typology of service paradigms and integrity. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 13(1), 5–15.

- Bringle, R. G., Phillips, M. A., & Hudson, M. (2004). The measure of service learning. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Bringle, R. G., Reeb, R. Brown, M. A., & Ruiz, A. (2016). Service learning in psychology: Enhancing undergraduate education for the public good. Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Brown, M. A. (2011a). The power of generosity to change views on social power. Journal of Experimental Social Psychology, 47, 1285–1290. Doi:10.1016/j.jesp.2011.05.021

- Brown, M. A. (2011b). Learning from service: The effect of helping on helpers’ social dominance orientation. Journal of Applied Social Psychology, 41, 850–871. Doi: 10.1111/j.1559–1816.2011.00738.x

- Clayton, P. H., & Ash, S. L. (2004). Shifts in perspective: Capitalizing on the counter-normative nature of service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 11(1), 59–70. Retrieved from http://hdl.handle.net/2027/spo.3239521.0011.106

- Costa‐Lopes, R., Dovidio, J. F., Pereira, C. R., & Jost, J. T. (2013). Social psychological perspectives on the legitimation of social inequality: Past, present and future. European Journal of Social Psychology, 43(4), 229–237. Doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1966

- Cunningham, E., & Platow, M. J. (2007). On helping lower status out‐groups: The nature of the help and the stability of the intergroup status hierarchy. Asian Journal of Social Psychology, 10(4), 258–264. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467–839X.2007.00234.x

- Dalbert, C., Montada, L., & Schmitt, M. (1987). Glaube an die gerechte Welt als Motiv: Validnering Zweier Skalen. Psychologische Beitrage, 29, 596–615.

- Feagin, J. R. (1971). Poverty: We still believe that God helps those who help themselves. Psychology Today, 6(6), 101–110, 129.

- Fisher, J. D., Nadler, A., Little, J. S., & Saguy, T. (2008). Help as a vehicle to reconciliation, with particular reference to help for extreme health needs. In A. Nadler, T. E. Malloy, & J. D. Fisher (Eds.), The social psychology of intergroup reconciliation (pp. 447–468). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Halabi, S., Dovidio, J. F., & Nadler, A. (2008). When and how do high status group members offer help: Effects of social dominance orientation and status threat. Political Psychology, 29(6), 841–858. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467–9221.2008.00669.x

- Jackson, L. M., & Esses, V. M. (2000). Effects of perceived economic competition on people’s willingness to help empower immigrants. Group Processes and Intergroup Relations, 3, 419–435. Doi: 10.1177/1368430200003004006

- Koschate, M., Oethinger, S., Kuchenbrandt, D., & Dick, R. (2012). Is an outgroup member in need a friend indeed? Personal and task‐oriented contact as predictors of intergroup prosocial behavior. European Journal of Social Psychology, 42(6), 717–728. Doi: 10.1002/ejsp.1879

- Michlitsch, J. F., & Frankel, S. (1989). Helping orientations: Four dimensions. Perceptual and Motor Skills, 69, 1371–1378.

- Moely, B. E., Furco, A., & Reed, J. (2008). Charity and social change: The impact of individual preferences on service-learning outcomes. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 15(1), 37–48.

- Morton, K. (1995). The irony of service: Charity, project and social change in service-learning. Michigan Journal of Community Service Learning, 2(1), 19–32.

- Nadler, A. (2002). Inter-group helping relations as power relations: Maintaining or challenging social dominance between groups through helping. Journal of Social Issues, 58, 487–502.

- Nadler, A., & Chernyak-Hai, L. (2014). Helping them stay where they are: Status effects on dependency/autonomy-oriented helping. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 106, 58. Doi: 10.1037/a0034152

- Nadler, A., & Halabi, S. (2006). Intergroup helping as status relations: Effects of status stability, identification, and type of help on receptivity to high-status group’s help. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 91, 97–110. Doi: 10.1037/0022–3514.91.1.97

- Nadler, A., & Halabi, S. (2015). Helping relations and inequality between individuals and groups. In M. Mikulincer, P. R. Shaver, J. F. Dovidio, & J. A. Simpson (Eds.), APA handbook of personality and social psychology, Volume 2: Group processes (pp. 371–393). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Nelson Laird, T. F., Engberg, M. E., & Hurtado, S. (2005). Modeling accentuation effects: Enrolling in a diversity course and the importance of social action engagement. The Journal of Higher Education, 76(4), 448–476. Doi: 10.1353/jhe.2005.0028

- O’Grady, C. R. (Ed.). (2000). Integrating service learning and multicultural education in colleges and universities. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

- Omoto, A. M., Snyder, M., & Hackett, J. D. (2010). Personality and motivational antecedents of activism and civic engagement. Journal of Personality, 78(6), 1703–1734. Doi: 10.1111/j.1467–6494.2010.00667.x

- Pascarella, E., Edison, M., Nora, A., Hagedorn, L., & Terenzini, P. (1996). Influences on students’ openness to diversity and challenge in the first year of college. Journal of Higher Education, 67, 174–195.

- Pettigrew, T., & Tropp, L. (2006). A meta-analytic test of intergroup contact theory. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 90, 751–783. Doi: 10.1037/0022–3514.90.5.751

- Piliavin, J. A. (2003). Doing well by doing good: Benefits for the benefactor. In C. L. M. Keyes & J. Haidt (Eds.), Flourishing: Positive psychology and the life well-lived (pp. 227–248). Washington, DC: American Psychological Association.

- Pratto, F., Sidanius, J., Stallworth, L., & Malle, B. (1994). Social dominance orientation: A personality variable predicting social and political attitudes. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 67, 741–763. Doi: 10.1037/0022–3514.67.4.741

- Rosner-Salazar, T. A. (2003). Multicultural service-learning and community-based research as a model approach to promote social justice. Social Justice, 30(4), 64–76. Retrieved from http://www.jstor.org/stable/29768224

- Sidanius, J., & Pratto, F. (1999). Social dominance: An intergroup theory of social hierarchy and oppression. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

- Smith, C., & Davidson, H. (2014). The paradox of generosity: Giving we receive, grasping we lose. Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

- Stürmer, S., & Snyder, M. (Eds.). (2010). The psychology of prosocial behavior: Group processes, intergroup relations, and helping. Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Turner, J. C., Hogg, M. A., Oakes, P. J., Reicher, S. D., & Wetherell, M. S. (Eds.). (1987). Rediscovering the social group: A self-categorization theory. Oxford, UK: Blackwell.

- Van Dijk, H., & van Engen, M. L. (2013). A status perspective on the consequences of work group diversity. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 86(2), 223–241. Doi: 10.1111/joop.12014

- van Leeuwen, E., & Täuber, S. (2010). The strategic side of outgroup helping. In S. Stürmer & M. Snyder (Eds.), The psychology of prosocial behavior: Group processes, intergroup relations, and helping (pp. 81–99). Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Van Leeuwen, E., & Täuber, S. (2012). Outgroup helping as a tool to communicate ingroup warmth. Personality and Social Psychology Bulletin, 38(6), 772–783. Doi:10.1177/0146167211436253

- Willyard, C. (2011). Men: A growing minority? gradPSYCH Magazine, 9(1), 40. Retrieved from http://www.apa.org/gradpsych/2011/01/cover-men.aspx

Authors

MARGARET A. BROWN (mb[email protected]) is a professor of Psychology, director of the Center for Scholarship and Faculty Development, and assistant provost at Seattle Pacific University. She is an experienced service-learning practitioner and has won multiple awards for excellence in teaching. Dr. Brown also conducts rigorous, theory-based, experimental research on service-learning. Her recent co-authored book, entitled Service Learning in Psychology: Enhancing Undergraduate Education for the Public Good, examines the importance of civic education within the undergraduate psychology curriculum, and provides a wealth of practical advice to faculty members and department chairs for successful implementation.

JARED D. WYMER ([email protected]) is a doctoral student in the Department of Industrial and Organizational Psychology at Seattle Pacific University. His research interests include prosocial behavior in organizations, the extent to which various factors influence future self-continuity, short- and long-term time horizons, and associated individual and organizational outcomes. He looks forward to candidacy and a career in industry.

CIERRA S. COOPER ([email protected]) double-majored in psychology and political science at Seattle Pacific University. She was an Ames Scholar, recipient of the Barnabas Service Award, and president of the Black Student Union. Her research interests are in psychological aspects of institutionalized racism, and she intends to pursue doctoral studies in human development and public policy.