Crafting a World-Class Brand: Shaw Brothers’ Appropriation of Foreign Models

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

In the 1960s, Hong Kong–headquartered film studio Shaw Brothers was intent on boosting its profile on the international stage by carefully crafting a “world-class” image. It also hoped to boost productivity and creativity with a new wave of films, for which it hired Japanese directors, cinematographers, and others above the line talent. Japan’s Nikkatsu Studio, the home of “borderless action” pictures, supplied a ready-made source of stories, styles, and marketing templates. Directors from Japan were asked to change their names, and titles of remakes tweaked to appeal to local audiences and regional Southeast Asian markets. Shaw Brothers’ desire for international recognition, box office success, and film festival prizes also drove the studio to look abroad at the model of successful Anglo-American productions such as the James Bond series. Were Shaw Brothers rewarded with market dominance, festival rewards, and a “world-class” status? This article will survey the output and financial growth of the studio from 1964 to 1971 to determine whether this strategy paid off.

Keywords: Hong Kong Cinema, Japanese Cinema, Shaw Brothers, the James Bond Series, Transnational Film Remakes

Shaw Brothers, one of the major film studios in Hong Kong, attempted to brand itself as being on a par with world-class film industries like Hollywood in the mid-1960s to the early 1970s. One of the founders, Run Run Shaw, had already in his mind the vision of expanding his entertainment empire globally when Shaw Brothers was set up in Hong Kong in 1958.[2] This would occur by going global by establishing new markets beyond the Chinese diaspora in Southeast Asia and making Shaw Brothers an equal member of the international film industry like Hollywood. The plan had not yet been fully implemented or publicized at that time, as the studio restructured to compete with its major rival Cathay Organization.[3] However, after the sudden death of Cathay Organization founder Loke Wan Tho in 1964, the studio’s production began to decline and led to a decision to scale back on film production in Hong Kong in 1970. As a result, Shaw Brothers faced no serious competition in its local and Southeast Asian markets until 1971, when independent production company Golden Harvest emerged.

During this period without rivalry, Shaw Brothers endeavored to pave a path toward becoming a world-class cinema. It was not until the mid-1960s when the competition had turned mild that Shaw Brothers’ in-house magazine Southern Screen publicized the plan. It boasted in consecutive years that the studio’s annual achievement was having produced films of “world-class”[4] quality. However, this assertion of the so-called “world-class” status did not quite hold up in comparison with the world’s oldest film industry, Hollywood. An empirical comparison of production costs, for example, gives the impression that Hong Kong cinema was still far behind Hollywood’s fiscal resources and dominance. In the mid-1960s, the average production cost of a Mandarin-language film in Hong Kong was about HKD500,000 (US$84,000),[5] whereas the cost of an average film in Hollywood was US$2,500,000.[6] Then what did Shaw Brothers imply by “world-class”? This article considers “world-class” as a branding strategy which Shaw Brothers leveraged as part of its strategy to grow its operations and its own brand on the global stage and investigates how it crafted this brand. Looking abroad at the model of successful Anglo-American productions such as the James Bond series, Shaw Brothers decided to produce its own Bond-style action films for which it hired Japanese directors. These films adapted Japanese studio Nikkatsu’s style, which was itself a by-product of Hollywood. This article examines the films, financial growth, and international reputation to determine whether Shaw Brothers’ Bond productions facilitated the studio’s branding attempts to be of the “world-class.”

A brand works as a guarantee of quality or to give a mass-produced commodity an identity by linking it to an identifiable producer.[7] In this case, Shaw Brothers wanted audiences to associate its films with established world-class productions like Hollywood films. Shaw Brothers’ “world-class” brand was not backed by any tangible empirical evidence such as high production values on par with Hollywood’s finest films; instead, the studio sought to use its “world-class” brand to create a connection in the minds of audiences between Shaw Brothers and Hollywood. Despite such intangible values, the material aspects of the brand should not be overlooked. To emphasize a brand’s materiality, Celia Lury argues that a brand is an object, albeit an intangible one.[8] A brand is an object because it is a dynamic platform for the various components and practices that function together to exert tangible effects, such as on the financial outcomes of production. When Lury argues for the materiality of a brand, she does not simply point out the institutional practices that build a brand as constituting its material aspects. Rather, she argues that it is this dynamic platform of a brand that makes it material. In other words, it is important to note that institutional practices and a brand provide a foundation for each other: While a brand is a basis on which institution practices function, anything that the institutional practices have generated supports a brand’s intangible values. And hence, our focus should not be limited to marketing strategies that directly build a brand but to incorporate other practices. Regarding the film industry, in particular, the set of institutional practices that relate to a studio’s brand include talent pools, narrative traditions, methods of production, management structures, and marketing strategies.[9] As a studio’s brand is a total sum of all the above practices, it is too large a scope to discuss them all. This article focuses on talent pools and narrative traditions while only briefly touching upon management and marketing strategies because it explores how the decision of Shaw Brothers to employ Japanese filmmakers in the late 1960s enabled it to diversify its genre output in the goal of advancing its “world-class” brand of filmmaking.

The first section of this article discusses how drawing Japanese talent into the studio’s pool of directors followed the principles of media capitals that aligned with Shaw Brothers’ goal to transcend its local status. This industrial practice not only moved Shaw Brothers a step forward in becoming a world-class film industry but also facilitated the process of establishing a perception of a world-class brand. Brand names of studios can be established through product features such as genres, stars, plots, and spectacles.[10] However, cinematic images and sound can also be considered as a locus of brand activities.[11] The next section moves on to examine how Shaw Brothers’ world-class brand was also established through cinematic images and sound in the genre films directed by these Japanese directors, who brought with them a ready-made source of stories and style to Shaw Brothers’ productions. All the Japanese directors who were hired by Shaw Brothers were experienced in directing Nikkatsu Action films, which was the label applied to the “borderless action” pictures produced by Japanese studio Nikkatsu in the mid-1950s to the early 1960s. This article examines subsequent Shaw Brothers’ action films helmed by the Japanese directors, many of which imitated the genre tropes, narratives, and iconography of the James Bond series. These British spy films became a pop-cultural phenomenon and were a huge global box office success, including in Hong Kong, where they were among the highest grossing films in the mid-1960s.[12] Capitalizing on the global popularity of the James Bond series, Shaw Brothers decided to produce its own Bond-style action films. It made at least eleven such action films from 1966 to 1971, seven of which were produced by Japanese directors. This section analyzes Asia-Pol (Matsuo Akinori, 1996) and Interpol 009 (Nakahira Ko, 1967). These two films are chosen for their obvious connection with Nikkatsu. The former one was a Shaw Brothers–Nikkatsu coproduction, whereas the latter was a remake of Nakahira Ko’s Nikkatsu production, The Black Challenger (1965). This article argues that Shaw Brothers’ appropriation of foreign models gave its Bond-style action films façade of a world-class, international brand, and a cosmopolitan dimension that served the fantasy of being world citizens for Asian audiences, who were themselves consuming and appropriating an ever-increasing diet of international ideas, attitudes, and styles during this time. Shaw Brothers’ films adapted popular elements from global hits in its bid to guarantee the popularity of its films, as well as to engineer its products for a more diverse audience. It is fair to say, however, that these genre films produced by the Japanese directors were derivative at best. International recognition for a world-class brand needed something greater and more finessed than imitations. The conclusion of this article surveys the outcomes of these strategies of crafting a world-class brand in terms of market expansion and international film festival prizes. The Japanese factor in Shaw Brothers’ strategies succeeded in increasing the studio’s productivity but failed to lift its reputation to the worldly heights.

Institutional Practices: To Become a World-Class Film Industry

As a brand and institutional practices provide a foundation for each other, it is significant to first examine Shaw Brothers’ institution practices that provided a basis for the world-class brand. One such tactic was the hiring of Japanese talent into its pool of directors. At the time, Shaw Brothers had secured its Chinese diasporic markets through a series of successful costume dramas produced in the 1950s.[13] As a result, its stable of directors had come to specialize in the genre, which won over local and diasporic Chinese audiences. However, to ascend to the levels of a world-class film industry, Shaw Brothers had to reach audiences not limited to the Chinese. Given the global popularity of the James Bond series in the mid-1960s, pivoting to the production of action thrillers seemed to be a logical response to appeal to the desires of markets across Asia and beyond. The plan led to the large-scale employment of Japanese directors.[14]

Cinematographer Nishimoto Tadashi, who first worked for Shaw Brothers’ color-film productions under short-term contracts, was later asked for a recommendation of Nikkatsu Action directors. He suggested a few names: Inoue Umetsugu, Nakahira Ko, and Matsuo Akinori.[15] While Matsuo came to Hong Kong under a more formal coproduction between Shaw Brothers and Nikkatsu to direct Asia-Pol, other directors were employed by Shaw Brothers on short-term contracts. Following Nishimoto’s recommendation, Inoue went to Hong Kong to work for Shaw Brothers in 1966. He directed two Bond-like films for Shaw Brothers, Operation Lipstick (1967) and Brain Stealers (1968). Nakahira traveled to Hong Kong twice to make four films for Shaw Brothers, of which Interpol 009 and Diary of a Lady Killer (1968) were action thrillers. Soon after Inoue, Furukawa Takumi, also from Nikkatsu, came to work for Shaw Brothers through Inoue’s introduction and directed Black Falcon (1967) and Kiss and Kill (1967).

Shaw Brothers’ recruitment of Japanese filmmakers demonstrated “trajectories of creative migration,” one of the principles of media capitals. It refers to the concentration of creative talents in a particular place as film industries need replenishment of creative laborers for aesthetic innovation to respond to the markets.[16] By bringing Japanese talents to its studio to produce action films which were not its full-time directors’ specialties, Shaw Brothers was responding to the appetites of the global market that craved popular cinematic styles such as the Bond series. This institutional practice demonstrated Shaw Brothers’ attempt to establish its studio in Hong Kong as a media capital: a powerful geographic center that concentrates human, creative, and financial resources to fashion products that serve the needs of their targeted audiences.[17] The goal was to transcend the studio’s local status and to produce films for audiences in Asia and beyond. Also, hiring Japanese directors on short-term contracts as a means of flexible accumulation not only saved staff costs but also enhanced the studio’s capability to respond to competitors and respond quickly to market demand. While other studios in Asia might also attempt to produce Bond-like action films, the Nikkatsu directors Shaw Brothers hired brought with them a ready-made source of stories, stylistic traits, and popular action-cinema knowledge to produce Bond-like action films faster than their competitors. The recruitment was also a strategy to glean the industry expertise of the Japanese directors, all the while profiting from it, rather than competing directly with Japanese studios.[18]

These ready-made models included not only generic remakes, which will be discussed in the subsequent section, but also marketing templates for distribution and exhibition. Shaw Brothers modeled Nikkatsu’s marketing templates as it was faced with a demographic shift in its audience in the 1960s, similar to what Nikkatsu had faced in the decade prior. The postwar years in Japan had created a new cultural climate and an increase in younger audiences as “many Japanese began to develop a new sense of curiosity, fascination, and admiration for the U.S.”[19] Knowing the audiences’ interest in American culture, Nikkatsu began to appropriate Hollywood cinematic conventions such as film noir and crime films for screen narratives to obtain a share in the market and appeal to young audiences, further differentiating its films from those of other Japanese studios which targeted middle-aged cinemagoers.[20] In the mid-1960s, Shaw Brothers had to address the increasing number of young audiences in Hong Kong and across its Asian markets who craved Anglo-American popular culture. The demographics backed up the market case for such a strategy: In 1961, about 20 percent of the total population in Hong Kong were aged between 15 and 29 years. Within five years, that age group had increased by 132 percent.[21] The postwar baby-boomers did not share their parents’ nostalgia for their ancestral homeland and appetites for predominantly Chinese cultural touchstones. Instead, they desired what global popular culture offered, such as the freedom and individualism represented by rock ’n’ roll, as well as the adventurous and luxurious life glorified by the James Bond film franchise. To ensure its adaptations would appeal to these young audiences in Hong Kong, Southeast Asia, and beyond, Shaw Brothers replicated Nikkatsu’s marketing strategy. The distribution and exhibition of Hollywood movies had brought Nikkatsu revenue and familiarized Japanese audiences with Hollywood genres before it produced its own films imitating Hollywood genres. Similarly, Shaw Brothers made the canny strategic decision to buy two hundred Nikkatsu Action films for a discounted lump sum, for distribution and exhibition in Southeast Asia[22] to familiarize audiences with Nikkatsu Action and to pave the way for the box office success of its own adaptations of Nikkatsu Action films. This adaptation of Nikkatsu’s marketing strategy in the mid-1960s followed about a decade later than Nikkatsu’s own implementation of such tactics. Given the fact that the number of films produced by Shaw Brothers was less than 15 in the mid-1950s,[23] the studio was far from planning the expansion of its market at that time. Despite the time lag, Shaw Brothers’ replication of Nikkatsu’s strategy for consolidating the local market followed only after the studio had faced less vigorous external competition. Together with the concentration of international talent in its studio to produce films, such institutional practices represented a step forward in becoming a world-class film industry that could reach a wide audience not limited to its previous Chinese diasporic markets.

Implanting the Brand in Narratives: An Appropriation of Foreign Models in Shaw Brothers’ Bond Films

Attracting international talent could establish Shaw Brothers as a media capital and facilitated the creation of a world-class image. Hong Kong Movie News, another official magazine of Shaw Brothers, first published in 1966, in addition to Southern Screen, claimed that the studio pioneered the employment and invitation of Japanese directors in the history of Chinese motion pictures.[24] It honored Shaw Brothers’ contribution to Mandarin-language films because Inoue, whose films were internationally well-received, was employed and invited respectfully to join the production of Operation Lipstick.[25] Paradoxically, however, Shaw Brothers requested that the Japanese filmmakers used Chinese pseudonyms to conceal their Japanese identity, for example, on posters for distribution and opening credits for exhibition. However, Southern Screen and Hong Kong Movie News used their Chinese pseudonyms and Japanese names interchangeably without such a deliberate intention for camouflage. Whether the reason for hiding their identity was related to ethnic sentiments after World War II or simply legal concerns, it did hamstring Shaw Brothers’ efforts to fully leverage the publicity of attracting international talents as a way of enhancing its world-class brand. However, it does not necessarily mean it completely negated the benefits of employing Japanese talents in contributing to its branding exercise. This section directs attention to how the brand was established through the genre films produced by the Japanese directors. Given how cinematic images and sound are a locus of brand activities, the section analyzes iconography and locales of the genre films, as well as languages spoken by the characters.

Shaw Brothers exploited the ready-made source of stories of Nikkatsu Action films to produce its Bond-style action films for Asian audiences. In the case of Interpol 009, Shaw Brothers’ production was a direct remake of The Black Challenger, which was recognized as a wasei 007 film (a Japanese-made 007).[26] More importantly, Shaw Brothers appropriated the style of Nikkatsu Action directors: mukokuseki. Mukokuseki literally means nationality-less and is commonly used to describe the style of Nikkatsu Action that mixed generic elements from multiple cultural origins or erased cultural characteristics.[27] Shaw Brothers’ Bond films had a self-conscious eclecticism that showed obvious cross-cultural references for establishing a world-class brand. On the one hand, universally decodable elements from the James Bond series such as fast-paced action sequences and shrewd usage of gadgets gave Shaw Brothers’ own Bond-style films an international façade, comparable with the Anglo-American film industry. On the other hand, while the cultural features of Asia were downplayed, “Asia” was highlighted as a marker that signified tailor-made productions intended to serve the distinctive needs of audiences in the regional market.

To be comparable with Anglo-American productions, Shaw Brothers’ Bond films made explicit acknowledgment of their Anglo-American counterparts. In terms of the narrative formula, an invincible spy completes a mission assigned by an international organization to prevent a serious criminal plot concocted by ruthless villains, whereas identifiable icons include high-tech gadgets, seductive women and love interests, and glamorous settings such as casinos. The Bond formula in Shaw Brothers’ action films also extended beyond these narrative conventions and visual devices: The imitation started right from the beginning of the first reel with title sequences that were a direct homage to the Bond films, laying the foundations for audiences’ association of Shaw Brothers’ films with the established, and well-received, Bond narratives.

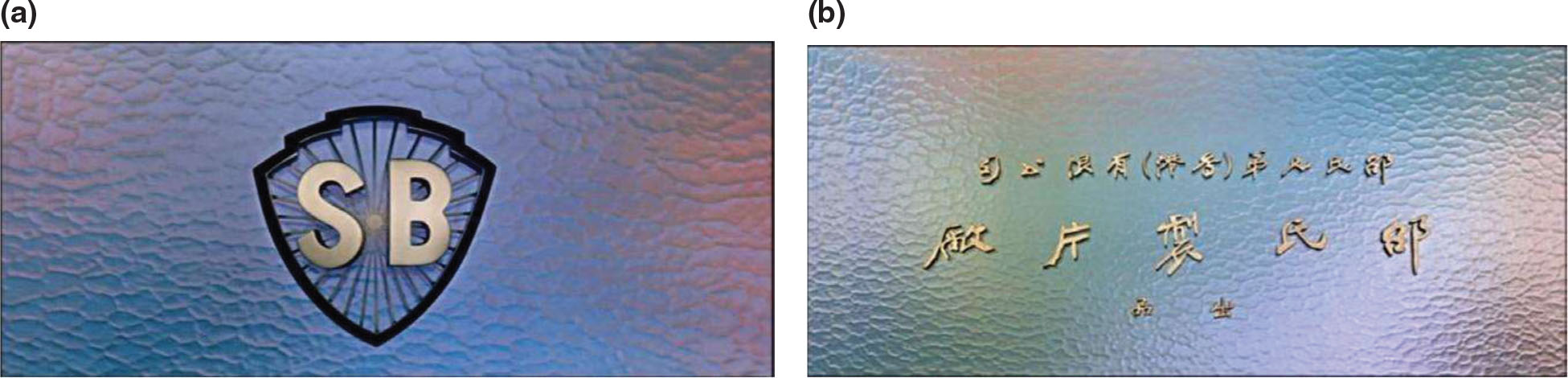

Title sequences serve multiple functions including legal, aesthetic, and spatial. First, they provide a legal function by listing the production credits, starting with a studio’s trademark logo, which itself acts as a kind of teaser for the title sequence proper.[28] In the case of Shaw Brothers, this was a shield stamped with initials S.B., a striking similarity to the logo of Warner Brothers, one of the venerable Hollywood studios held in such high regard by the Hong Kong studio, which was followed by the company’s name, which began every Shaw Brothers’ picture (Figure 1a and 1b). Like stamping the Shaw Brothers’ trademark on a film, it was an act of branding that clearly communicated to audiences an inseparable relationship between Shaw Brothers and the film that they were going to watch. Second, there is an aesthetic function of a title sequence that foreshadows for audiences the genre and the specific mood of what is to come, initiating them into the cinematic narrative.[29] Furthermore, another element that had become institutionalized within the title sequence of such films was “the James Bond theme,” to the extent that without such hallmarks, a Bond film would not feel like a Bond film at all.[30] The signature gun barrel motif, the recurring images of guns, and moving, silhouetted female figures characterized the title sequences, such as those designed by Maurice Binder from Dr. No (Terence Young, 1962) to License to Kill (John Glen, 1989).

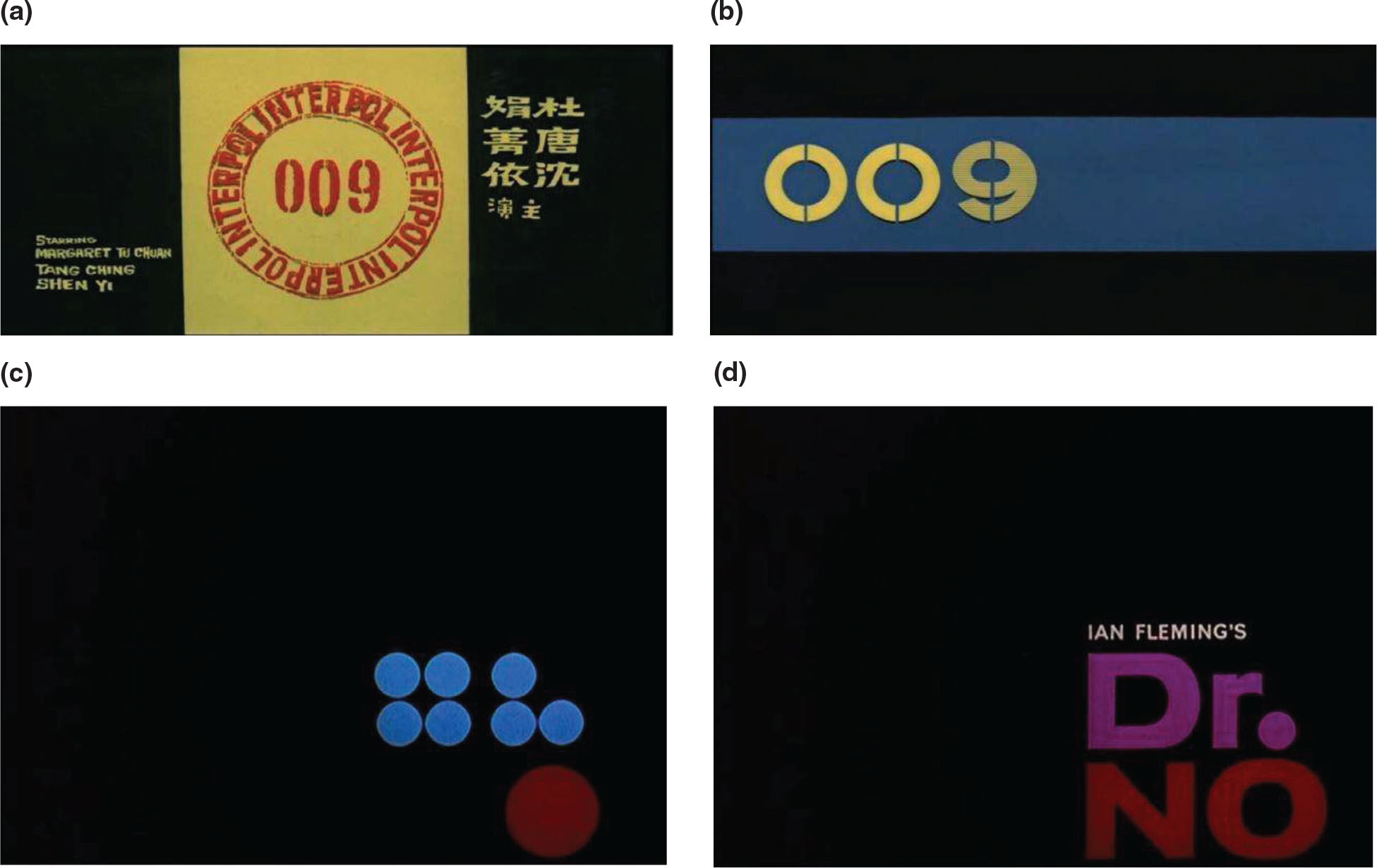

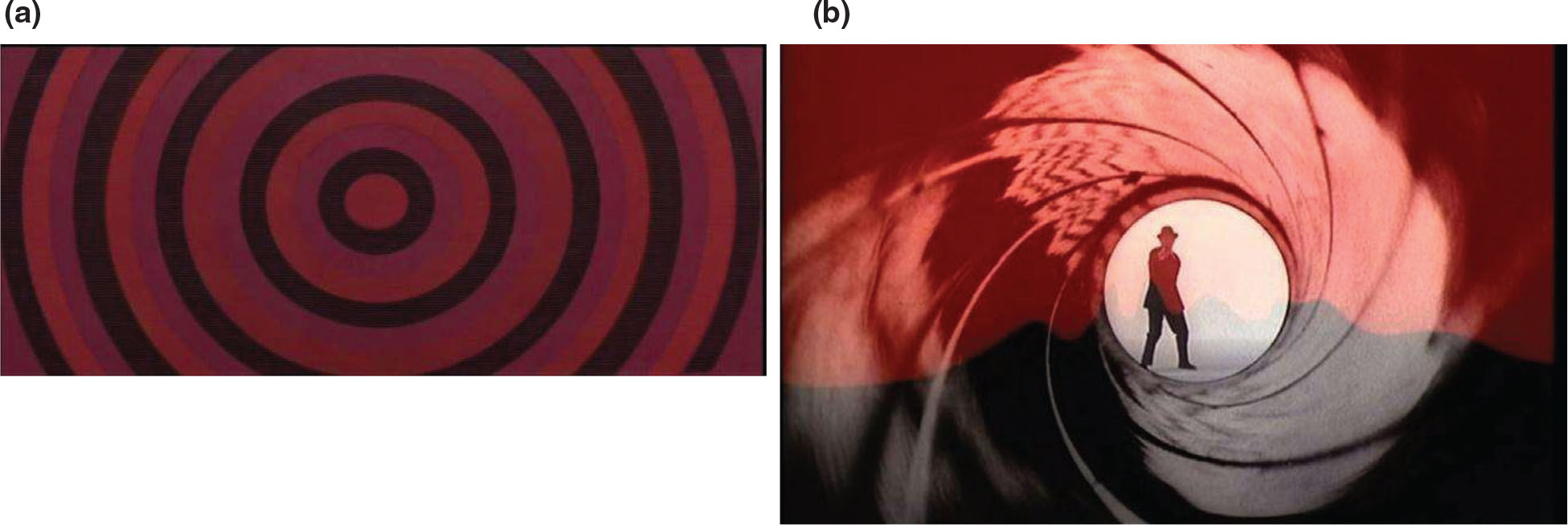

Shaw Brothers’ Bond films consciously fostered links with the Bond series through the mimicry of visual icons in the title sequences. The imitation of the aesthetic not only captured the mood of action thrillers but also signaled to its audiences that these were action films designed in the mold of the popular Bond series. Shaw Brothers also had a credit designer, Kamber Wong (Chi Pei Ling), responsible for designing its Bond-type films’ title sequences. These showed consistency of motifs that borrowed from the James Bond series. For example, the title sequence of Dr. No starts with a few white dots blinking across the screen, and the last dot enlarges into a gun barrel. Bond himself is seen through the barrel, and he shoots directly at the camera. Then, the flashing color dots fill the screen and one of the dots turns to the round-shape “O” of Dr. No. Because the gun barrel sequence was copyrighted by EON Productions, which produced the Bond films, Shaw Brothers only copied the geometric patterns, circular motifs, vivid color usage, and gun images, and rather than superimposed credits on live-action images, most Shaw Brothers’ Bond films used animation to mirror the eye-catching visual elements in the Bond title sequences. The title sequence of Interpol 009 repeats the circular motifs using round-shape objects such as a bomb, a countdown timer, and the emblem of International Police 009. The blinking circular emblem of International Police is followed by the round-shape “0” of the title “009,” a clear homage of the “O” of Dr. No (Figure 2a–2d). Then, the lines of a dartboard swirl and the pattern resembles the barrel of a gun, recalling the signature gun barrel motif (Figures 3a and 3b). Such explicit references in Shaw Brothers’ action title sequences prompted audiences to associate their viewing experience with the Bond series while they began their transition from their real-world with this intertextual reference to the diegesis of Shaw Brothers’ Bond films. Together with the logo in the beginning, the imitated title sequence functioned as a statement to audiences that Shaw Brothers was producing a film comparable to the internationally recognized and beloved James Bond series.

Figure 1. (a) The logo of Shaw Brothers in the title sequence. (b) “Shaw Brothers (HK) Ltd.” and “produced by Shaw Brothers Studio” follow the logo.

Figure 1. (a) The logo of Shaw Brothers in the title sequence. (b) “Shaw Brothers (HK) Ltd.” and “produced by Shaw Brothers Studio” follow the logo. Figure 2. (a and b) The circular emblem of Interpol 009 blinks and turns into the round-shape “0” of “009.” (c and d) The red dot turns into the “O” of Dr. No.

Figure 2. (a and b) The circular emblem of Interpol 009 blinks and turns into the round-shape “0” of “009.” (c and d) The red dot turns into the “O” of Dr. No. Figure 3. (a) The lines of a dartboard swirl in the title sequence of Interpol 009. (b) The gun barrel signature in the James Bond title sequences.

Figure 3. (a) The lines of a dartboard swirl in the title sequence of Interpol 009. (b) The gun barrel signature in the James Bond title sequences.In addition to this deliberate branding smokescreen created by the title sequences, Shaw Brothers’ Bond films were designed to convey their world-class ambitions and branding through a projection of cosmopolitan fantasy weaved into the narratives, tailor-made for upwardly mobile and increasingly aspirational and Western-facing Asian audiences. Projecting a sense of cosmopolitan fantasy was one of the strongest appeals to audiences across nations. “Feeling cosmopolitan” contains an affective dimension that transcends traditional forms of identification such as nationality.[31] To generate this feeling, a sense of belonging to a distinctly cosmopolitan class is established through cinematic experience.[32] Although Juan Llamas-Rodriguez discusses the cinematic experience in terms of movie-going, his discussion on how to let audiences “feel cosmopolitan” applies to film texts. A major difference that needs to be noted: For audiences watching Shaw Brothers’ Bond films, their identification came from fantasy rather than experience. The distinctly cosmopolitan class carries with it a sense of the elite with the means to rise above the trivial concerns of daily life.[33] In Shaw Brothers’ Bond films, this manifested in glamorous protagonists who traveled around the world with no financial concerns. However, audiences in the 1960s had limited border-crossing opportunities. A sense of belonging to the distinctly cosmopolitan class was a fantasy projected by the films. Despite the fantasy, Shaw Brothers’ Bond films adopted the ways of letting audiences feel cosmopolitan as discussed by Llamas-Rodriguez. By capitalizing on similarities across nations and effacing differences in favor of a global standard, a sense of affiliation with imagined populations across the world is fostered.[34] Such methods are congruent with mukokuseki: erasing cultural characteristics.

First, non-locale-specific modernity was enhanced by urban settings such as casinos in the narratives. The settings in Shaw Brothers’ Bond films were associated with Westernized modernity, taking their cues from the Bond series. Casinos were typical settings in the Bond series, but the British casino was very much shown to be one at the apex of society rather than mundane.[35] Casinos signified a highbrow social space where James Bond possessed enough social and cultural capital to successfully navigate his way through this space to bring down the villain’s organization.[36] Compared with the glamorous casinos in the Anglo-American productions, the low-cost sets in Shaw Brothers’ Bond films were more like gambling dens drawn from the milieu of gangster films. Limited production costs were the constraints of Shaw Brothers on producing first-rate films. Instead, Shaw Brothers’ Bond films modeled Westernized modernity more closely to Nikkatsu Action for the lifestyle and milieu. Within Nikkatsu Action, there is a rarely discussed “Gambler” series that ran to eight films in total. Akira Kobayashi was cast in all films as a James Bond-esque wandering gambler. Nakahira directed two films in the series: The Black Gambler (1965) and the sequel The Black Gambler: Devil’s Left Hand (1966). Although the character was not an officer in an international police force, frequenting casinos dressed in a well-tailored suit, driving a covetable, gadget-equipped car cast him in the mold of Bond. Gambling with ambassadors of Western countries at casinos where high-tech video surveillance was installed implied a Westernized, modern milieu and lifestyle. The male protagonist of Interpol 009 also wore tuxedos to go to a casino to gather information on criminal enterprises. The international participants and the surveillance cameras in the casinos that were copied from The Black Gambler served to give Interpol 009 a modern milieu. Bouncers of the casino in Interpol 009 even had gadgets, which were absent in The Black Gambler. This pervasiveness of technology and an explicit association with Bond’s gadgetry further sign-posted Westernized modernity for audiences.

Second, Shaw Brothers’ Bond films adapted mukokuseki to enhance the commonality among the locales in Asia by portraying them as generic modern cities. However, given the previewing views of oriental fantasy, certain Asian locales were depicted as modern and yet exotic, in which the geopolitical hierarchy was in play implicitly. On the one hand, locales around Asia such as Tokyo and Hong Kong were portrayed as cities by iconography of skyscrapers, highways, and traffic. In Asia-Pol, after the animated title sequence showing an arrow moving across a world map and stopping at the typography of Japan, blocks of high-rise buildings are seen from a tracking shot signifying a side-window view from a car (Figure 4). Then, the male protagonist in the car arrives at a department store. The typography, together with the Japanese signs in the store, as well as conversations of the characters, clearly tells the audiences that the narrative begins in Tokyo. When the story takes place in another locale, more straightforwardly, “Hong Kong” is superimposed on a cutaway shot of densely packed buildings also viewed from a moving car (Figure 5). Despite the skyscrapers and highways, locations in Hong Kong such as a Chinese temple, wet markets with hawkers, and sampan boats on the harbor rendered Hong Kong an exotic locale. Shaw Brothers’ Bond films attempted to create locales in Asia as cities with modernity comparable with the West. And yet, the constraints of stereotypical oriental settings weakened the effects. Tokyo remained a modern city, whereas other locales in Asia were fairly exotic.

Third, the aping of Bond-esque narratives within the settings of Shaw Brothers’ own Asia-set Bond films attempted to serve the cosmopolitan fantasy of placing these Asian locations on a par with their Western counterparts. Just as the Anglo-American film industry had James Bond, Shaw Brothers had its Asia-Pol, aka Asian Police Secret Service, in essence an Asian James Bond organization. Shaw Brothers’ publicity promoted the male star Paul Chang who acted in Operation Lipstick, Black Falcon, and Kiss and Kill as the “Eastern James Bond.”[37] Of course, it was not the marker “Asian James Bond” alone that appealed to Asian audiences. The globe-trotting characters embodied by a pan-Asian cast brought a cosmopolitan dimension to Shaw Brothers’ Bond films. Bond was characterized by his mobility and adaptability as he traveled seamlessly to various countries for his missions, without any problems of adapting to the environment. Similarly, the Bond-esque protagonist Yang Mingxuan (Wang Yu) in Asia-Pol travels from Tokyo to Hong Kong, then onto Macau to investigate a crime, and in the end, departs for Thailand. While languages used by characters of different ethnicities might be obstacles to his adaptability to the environment, the film was dubbed for distribution, and most characters spoke Mandarin after dubbing. The obstacles were eliminated and ethnic differences were downplayed. The ethnic differences among the pan-Asian cast were further downplayed by a deliberate use of Chinese pseudonyms. In Asia-Pol, extra-diegetic information such as her name appearing in the title credits revealed that Japanese actress Asaoka Ruriko participated in the film. However, the narrative used a Chinese pseudonym to downplay her ethnicity. Yang addresses her by her Chinese name, Xingzi, rather than her Japanese name, Sachiko, as shown in the English subtitles. What caused the discrepancy? Asia-Pol had a Japanese version with the same plot but Japanese actor Nitani Hideaki as the male protagonist. In that version, the female protagonist was addressed as Sachiko. Ethnic differences were even less discernible in other Shaw Brothers’ Bond films: In Interpol 009, Shaw Brothers cast a Chinese actor for a thug named Mike Casdero whose ethnicity was not specified, whereas the Japanese original cast an African American actor for the same role. Pan-Asian characters who led a modern lifestyle of globe-trotting and border-crossing like James Bond projected a cosmopolitan fantasy of being a citizen of the world. Shaw Brothers’ Bond films endeavored to reinforce the fantasy for Asian audiences despite their cultural differences: a sense of affiliation with imagined populations across Asia and the world, and in turn a sense of inclusion as members of the world.

Conclusion

It is fair to say that Shaw Brothers’ institutional practices of employing Japanese directors served to increase the studio’s creativity and output. This, in turn, helped to serve the studio’s goal of crafting a world-class brand, alongside its strategy of appropriating foreign models to bring a cosmopolitan dimension to its films. Furthermore, the adoption of Nikkatsu Action’s mukokuseki style, deliberately mixed with various narrative elements and iconography of the James Bond series into Shaw Brothers’ action films, helped to give a perception of these films as being on par with the Anglo-American productions. The non-locale-specific modern activities such as gambling and globe-trotting were embodied by pan-Asian actors with their ethnic differences being downplayed, in turn playing up the cosmopolitan fantasy of being world citizens for Asian audiences. However, Shaw Brothers’ efforts to present itself as a modern studio with a cosmopolitan outlook and aspiration were not without constraints. Production costs and prevailing views of oriental fantasy might hinder its branding attempts. This last section surveys box office success and film festival prizes to gauge the extent to which Shaw Brothers succeeded in achieving a world-class brand.

In examining Shaw Brothers’ efforts to establish a “world-class” brand, this article has emphasized the importance of the material aspects of a brand. In addition to institutional practices, another significant aspect is the tangible effects of a brand on outcomes, such as production and financial and critical success. As such, their strategies did exert influences on financial outcomes and market expansion. One-Armed Swordsman (Chang Cheh, 1967), which was a martial art film closer to Shaw Brothers’ traditional strength of costume dramas, broke Hong Kong box office records by over HKD1 million.[38] On the contrary, Shaw Brothers’ Bond films brought in about HKD500,000 on average.[39] Nevertheless, Shaw Brothers never intended for its action films to be high-budget productions. Instead, its aim was to copy the James Bond series’ template of intriguing action narratives and aspirational lifestyles for films which it could turn out faster and far cheaper than the bloated Anglo-American production budgets. As a result, by the late 1960s Shaw Brothers managed to increase its production by about twenty films a year compared to earlier in the decade. Given there were no official annual reports released to the public in the early days, the number of films produced was based upon Southern Screen’s articles on Shaw Brothers’ annual production plans or review. As there might be discrepancies, the actual number of films released annually is provided for cross-references (Table 1). Shaw Brothers’ institutional practice of hiring Japanese talent certainly raised the quantity of its production output, but whether it similarly raised the quality is debatable. The six Japanese directors recruited by Shaw Brothers produced thirty-two films from 1966 to 1971, contributing 17 percent of the total production and about 30 percent of the increase. For the proportion of the total number of Mandarin-language films released in Hong Kong, including those imported from Taiwan and China, Shaw Brothers had a market dominance of about 40 percent.[40] By 1969, Shaw Brothers’ films grossed an average HKD850,000 for each picture, 12 percent more than the previous year.[41] As demonstrated by these rough estimates, Shaw Brothers’ recruitment of creative talents and crafting a world-class brand worked hand-in-hand to expand its markets.

Year | No. of films releaseda | No. of films producedb |

|---|---|---|

1964 | 15 | 23 |

1965 | 19 | 26 |

1966 | 18 | 41 |

1967 | 42 | 44 |

1968 | 28 | 45 |

1969 | 30 | 48c |

1970 | 34 | 40 |

1971 | 38 | 40 |

However, did these films help the studio enhance its international reputation and standing? In the early 1960s, costume dramas such as Magnificent Concubine (Li Han-hsiang, 1962) and Empress Wu (Li Han-hsiang, 1963) were entered into the Cannes Film Festival; the former won Best Color Photography. The Kingdom and the Beauty (Li Han-hsiang, 1959), also a costume drama, delivered Shaw Brothers its first Best Picture award, at the Sixth Asian Film Festival.[42] In the late 1960s, in addition to its international fame built on costume dramas, Shaw Brothers gained recognition through contemporary films like The Blue and the Black (Doe Ching, 1966, Best Picture of the Thirteenth Asian Film Festival) and Susanna (Ho Meng-hua, 1967, Best Picture of the Fourteenth Asian Film Festival). Shaw Brothers’ Bond films, however, did not win any international film festival prizes. Perhaps unsurprising, given that these films were derivative imitations, not only of the James Bond series but also of Japanese mukokuseki. Shaw Brothers’ shrewd development of international talent and narratives through these films did succeed in enhancing its prompt response to the markets’ demands for a greater share of the market, yet the international façade of Shaw Brothers’ Bond films hardly earned the artistic recognition in international film festivals that its other films enjoyed. To that end, it can be said that Shaw Brothers’ strategies only succeeded in growing its operations but had not quite lifted the studio’s reputation to the worldly heights it had aimed for.

Erica Ka-yan Poon is a postdoctoral research fellow in the Center for Cinema Studies at Lingnan University, Hong Kong. She completed her PhD at Hong Kong Baptist University. Her dissertation was titled “Co-producing a Cold War Cosmopolitan Fantasy: Collaboration and Competition between Hong Kong and Japanese Cinema in the 1950s and 1960s.” She holds a master’s degree in cinema and media studies from the University of California, Los Angeles. Her writings have appeared in Journal of Chinese Cinemas, Feminist Media Histories, and Journal of Japanese and Korean Cinema. Her research interests include East Asian cinemas, transnational cinema, and the media industries.

Originally established in Shanghai in 1925, by 1928 Shaw Brothers had established distribution and exhibition circuits in Southeast Asia when two of the brothers of the Shaw family, Runme and Run Run, moved to Singapore. In 1958, Shaw Brothers in Hong Kong was set up through a merger of Singapore’s Shaw Organization. See Kam Tan, “The Long Road to Global Hollywood: Shaw Brothers, Golden Harvest, and Dalian Wanda,” in The Palgrave Handbook of Asian Cinema (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018), 329–71; Poshek Fu, “Introduction: The Shaw Brothers Diasporic Cinema,” in China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema, ed. Poshek Fu (Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008), 1–25.

Cathay Organization had more than forty theaters in Southeast Asia. To ensure the supply of films to its theaters, Cathay Organization acquired a studio in Hong Kong for production and formed MP&GI (Motion Picture & General Investment Co. Ltd.) in 1956. The rivalry between the Shaw Organization and Cathay Organization extended from distribution in Southeast Asia to production in Hong Kong. Stephanie Po-Yin Chung, “A Southeast Asian Tycoon and His Movie Dream: Loke Wan Tho and MP&GI,” in Cathay Story, ed. Ain-Ling Wong (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 2009), 10–19.

Anonymous, “1964: Shaoshi fengshou di yinian” [1964: A Fruitful Year of Shaw Brothers], Southern Screen 83 (January 1965): 70–72; Anonymous “1965: Shaoshi di huihuang chengjiu” [1965: Brilliant Achievements of Shaw Brothers], Southern Screen 95 (January 1966): 11–14.

Government of Hong Kong, Hong Kong Annual Report 1968 (Hong Kong: Government of Hong Kong, 1969), 215.

Joel Waldo Finler, The Hollywood Story (London: Wallflower Press, 2003), 42.

Adam Arvidsson, “Brands: A Critical Perspective,” Journal of Consumer Culture 5 (2, 2005): 243–44.

Celia Lury, Brands: The Logos of The Global Economy (London: Routledge, 2004), 6.

Thomas Schatz, The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 73.

Janet Staiger, “Announcing Wares, Winning Patrons, Voicing Ideals: Thinking about the History and Theory of Film Advertising,” Cinema Journal 29 (3, 1990): 6.

Paul Grainge, Brand Hollywood: Selling Entertainment in a Global Media Age (London: Routledge, 2008), 14.

Anonymous, “Yinianlai zhi xianggang yule” [The Previous Year of Hong Kong Entertainment Industry], Xianggang nianjian 1967 [Hong Kong Yearbook 1967], 119.

Fu, “Introduction”; See Kam Tan, “Chinese Diasporic Imaginations in Hong Kong Films: Sinicist Belligerence and Melancholia,” Screen 42 (1, 2001): 1–20.

Tadashi Nishimoto, Kōichi Yamada, and Sadao Yamane, Honkon e no michi—nakagawa shinobu kara burūsu rī e [Toward Hong Kong: From Nakagawa Obuo to Bruce Lee] (Tokyo: Chikumashobō, 2004), 152.

Michael Curtin, Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV (Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007), 14–19.

Michael Curtin, “Chinese Media Capital in Global Context,” in A Companion to Chinese Cinema, ed. Yingjin Zhang (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012), 179–96.

Darrell William Davis, “Questioning Diaspora: Mobility, Mutation, and Historiography of the Shaw Brothers Film Studio,” Chinese Journal of Communication 4 (1, 2011): 53.

Hiroshi Kitamura, “Shoot-Out in Hokkaido: The ‘Wanderer’ (Wataridoi) Series and the Politics of Transnationality,” in Transnational Asian Identities in Pan-Pacific Cinemas: The Reel Asian Exchange, ed. Philippa Gates and Funnell Lisa (New York: Routledge, 2012), 33.

Hori Kyusaku, “Wakai sedai o taishō ni” [Targeting Young Generation], Kinema junpō 194 (January 1958): 52.

Richard Y. C. Wong and Ka-fu Wong, “The Importance of Migration Flow to Hong Kong’s Future,” in Hong Kong Mobile: Making Global Population, ed. Helen F. Siu and Agnes S. M. Ku (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008), 90.

Based on Ain-Ling Wong, “Filmography” in The Shaw Screen: A Preliminary Study, ed. Ain-Ling Wong (Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 2003), 346–415.

Anonymous, “Shaoshi pinqing riji daoyan” [Shaw Brothers Employed Japanese Directors], Hong Kong Movie News 4 (April 1966): 4–5.

Yoshio Shirai, “Yarō ni kokkyō ni wa nai” [The Black Challenger], Kinema junpō 1220 (December 1965): 77.

Mark Schilling, No Borders, No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema (Godalming: FAB Press, 2007); Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh, “Taipei as Shinjuku’s Other,” in Cinema at the City’s Edge: Film and Urban Networks in East Asia, ed. Yomi Braester and James Tweedie (Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010), 55–67; Watanabe Takenobu, Nikkatsu akushon no karei na sekai [The Glamorous World of Nikkatsu Action] (Tokyo: Miraisha, 1981).

Georg Stanitzek, “Reading the Title Sequence (Vorspann, Générique),” Cinema Journal 48 (4, 2009): 45.

James Chapman, “A Licence to Thrill,” in The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader, ed. Christoph Lindner (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009), 109–16.

Juan Llamas-Rodriguez, “A Global Cinematic Experience: Cinépolis, Film Exhibition, and Luxury Branding,” JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 58 (3, 2019): 64.

Jeremy Black, “Political Background,” in The World of James Bond: The Lives and Times of 007, ed. Jeremy Black (London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017), 1–26.

Lisa Funnell and Klaus Dodds, Geographies, Genders and Geopolitics of James Bond (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017), 195.

Anonymous, “Heiying” [Black Falcon], Southern Screen 104 (October 1966): 2–5.

Anonymous, “Dubidao shouru chao baiwan chuangxia guopian jilu” [One-Armed Swordsman Broke the Box Office Record of Mandarin Films], Overseas Chinese Daily News, September 2, 1967, p. 13.

Anonymous, “Yinianlai zhi xianggang yule” [The Previous Year of Hong Kong Entertainment Industry], Xianggang nianjian 1968 [Hong Kong Yearbook 1968], 118.

Anonymous, “Yinianlai zhi xianggang yule” [Hong Kong Yearbook 1967], 120; and [Hong Kong Yearbook 1970], 98.

Anonymous, “A Banner Year at Shaw’s Movie Town,” Southern Screen 143 (January 1970): 58.

Asian Film Festival, originally named Southeast Asian Film Festival, commenced in 1954. It was an annual event co-organized by Japanese and Southeast Asian film industries, including Hong Kong, the Philippines, Indonesia, Singapore, Thailand, and Taiwan during the Cold War.

Bibliography

- Arvidsson, Adam. “Brands: A Critical Perspective.” Journal of Consumer Culture 5, no. 2 (2005): 235–58.

- Black, Jeremy. “Political Background.” In The World of James Bond: The Lives and Times of 007, edited by Jeremy Black, 1–26. London: Rowman & Littlefield, 2017.

- Chapman, James. “A Licence to Thrill.” In The James Bond Phenomenon: A Critical Reader, edited by Christoph Lindner. Manchester: Manchester University Press, 2009.

- Chung, Stephanie Po-Yin. “A Southeast Asian Tycoon and His Movie Dream: Loke Wan Tho and MP&GI.” In Cathay Story, edited by Ain-Ling Wong, 10–19. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 2009.

- Curtin, Michael. “Chinese Media Capital in Global Context.” In A Companion to Chinese Cinema, edited by Yingjin Zhang, 179–96. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2012.

- Curtin, Michael. Playing to the World’s Biggest Audience: The Globalization of Chinese Film and TV. Los Angeles: University of California Press, 2007.

- Davis, Darrell William. “Questioning Diaspora: Mobility, Mutation, and Historiography of the Shaw Brothers Film Studio.” Chinese Journal of Communication 4, no. 1 (2011): 40–59.

- Davis, Darrell William, and Emilie Yueh-Yu Yeh. “Inoue at Shaws: The Wellspring of Youth.” In The Shaw Screen: A Preliminary Study, edited by Ain-Ling Wong, 255–71. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 2003.

- Finler, Joel Waldo. The Hollywood Story. London: Wallflower Press, 2003.

- Fu, Poshek. “Introduction: The Shaw Brothers Diasporic Cinema.” In China Forever: The Shaw Brothers and Diasporic Cinema, edited by Poshek Fu, 1–25. Urbana: University of Illinois Press, 2008.

- Funnell, Lisa, and Klaus Dodds. Geographies, Genders and Geopolitics of James Bond. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2017.

- Grainge, Paul. Brand Hollywood: Selling Entertainment in a Global Media Age. London: Routledge, 2008.

- Iwabuchi, Koichi. Recentering Globalization: Popular Culture and Japanese Transnationalism. Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002.

- Kitamura, Hiroshi. “Shoot-Out in Hokkaido: The ‘Wanderer’ (Wataridoi) Series and the Politics of Transnationality.” In Transnational Asian Identities in Pan-Pacific Cinemas: The Reel Asian Exchange, edited by Philippa Gates and Funnell Lisa, 31–45. New York: Routledge, 2012.

- Llamas-Rodriguez, Juan. “A Global Cinematic Experience: Cinépolis, Film Exhibition, and Luxury Branding.” JCMS: Journal of Cinema and Media Studies 58, no. 3 (2019): 49–71.

- Lury, Celia. Brands: The Logos of The Global Economy. London: Routledge, 2004.

- Nishimoto, Tadashi, Kōichi Yamada, and Sadao Yamane, Honkon e no michi—nakagawa shinobu kara burūsu rī e [Toward Hong Kong: From Nakagawa Obuo to Bruce Lee]. Tokyo: Chikumashobō, 2004.

- Schatz, Thomas. The Genius of the System: Hollywood Filmmaking in the Studio Era. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2010.

- Schilling, Mark. No Borders, No Limits: Nikkatsu Action Cinema. Godalming: FAB Press, 2007.

- Staiger, Janet. “Announcing Wares, Winning Patrons, Voicing Ideals: Thinking about the History and Theory of Film Advertising.” Cinema Journal 29, no. 3 (1990): 3–31.

- Stanitzek, Georg. “Reading the Title Sequence (Vorspann, Générique).” Cinema Journal 48, no. 4 (2009): 44–58.

- Tan, See Kam. “Chinese Diasporic Imaginations in Hong Kong Films: Sinicist Belligerence and Melancholia.” Screen 42, no. 1 (2001): 1–20.

- Tan, See Kam. “The Long Road to Global Hollywood: Shaw Brothers, Golden Harvest, and Dalian Wanda.” In The Palgrave Handbook of Asian Cinema, edited by Aaron Han Joon Magnan-Park, Gina Marchetti, and See Kam Tan, 329–71. London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2018.

- Watanabe, Takenobu, Nikkatsu akushon no karei na sekai [The Glamorous World of Nikkatsu Action]. Tokyo: Miraisha, 1981.

- Wong, Ain-Ling. “Filmography.” In The Shaw Screen: A Preliminary Study, edited by Ain-Ling Wong, 346–415. Hong Kong: Hong Kong Film Archive, 2003.

- Wong, Richard Y. C. and Wong, Ka-fu. “The Importance of Migration Flow to Hong Kong’s Future.” In Hong Kong Mobile: Making Global Population, edited by Helen F. Siu and Agnes S. M. Ku. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2008.

- Yeh, Emilie Yueh-Yu. “Taipei as Shinjuku’s Other.” In Cinema at the City’s Edge: Film and Urban Networks in East Asia, edited by Yomi Braester and James Tweedie, 55–67. Hong Kong: Hong Kong University Press, 2010.