Book Review

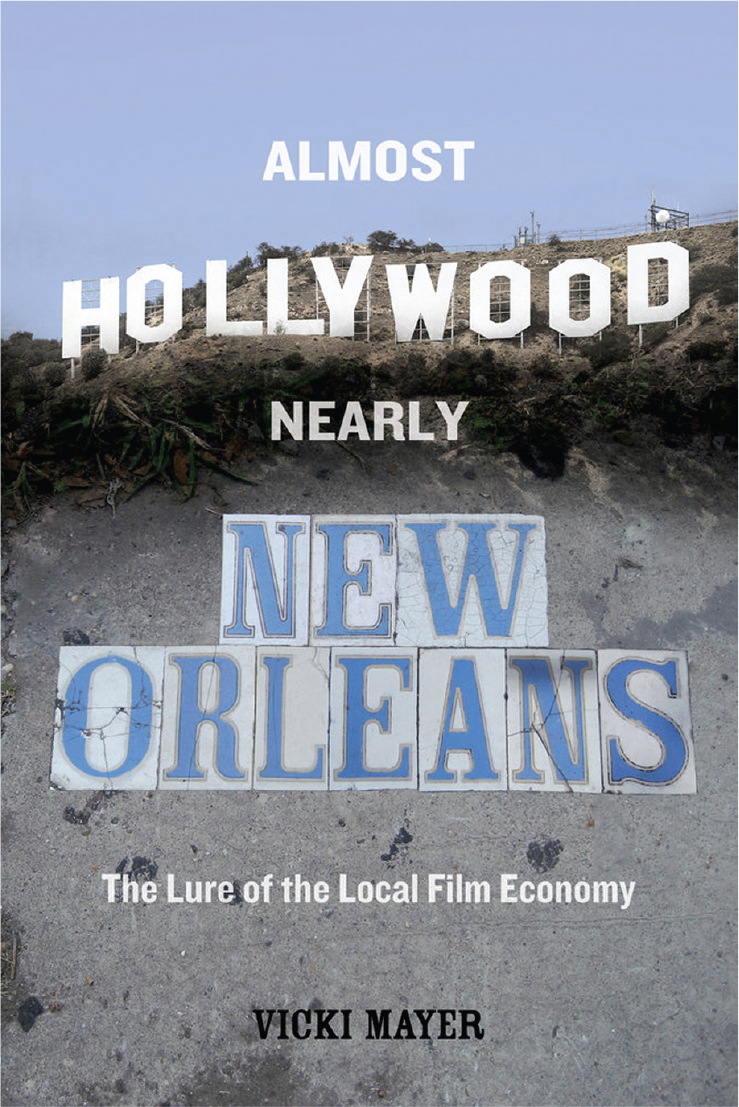

Mayer, Vicki. Almost Hollywood, Nearly New Orleans: The Lure of the Local Film Economy. (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017.)

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Vicki Mayer’s book-length study of the New Orleans film industry looks to unpack the “paradoxical tale of Hollywood South,” whose ties to screen production pre-date modern media industries’ government-subsidized attraction to “The City That Care Forgot.”[2] What may at first seem contradictory—in the case of Louisiana, the state is both impoverished and one of the nation’s largest economies for film production—is, in fact, symptomatic of the logic driving continued investment (financial, ideological, and discursive) in the promises of media industry, regardless of the outcomes.

At first blush, New Orleans’s predicament might seem eerily familiar—a consequence of the fashionable-yet-devastating imposition of neoliberal austerity and misplaced faith in corporate welfare’s capacity for broader economic stimulus. After all, as of July 2018, thirty-six states have some form of media production incentive program.[3] As the heart of the nation’s third-largest film production economy, New Orleans exemplifies the repercussions of this trend. By foregrounding the city’s long relationship with the film industry, however, Mayer adroitly historicizes the specificities of these dynamics while also gesturing to the broader instructiveness of this case study for the past and present.

Chapter 1, “The Making of Regional Film Economies,” explores the early but unrealized attempts to establish a pre-Hollywood film industry in New Orleans between 1909 and 1919. Situated in the Canal Street and Bayou St. John areas of the city, this fledgling sector was graced with visiting producers like Selig, Howe, Lubin, Lasky, and others. Mayer excavates the pre-history of what will recur a century later: local politicians, businesspeople, and boosters frame the film industry as a catalyst for local development and a magnet for prospective residents, businesses, and capital investment. Those dreams never materialized: producers left, the investment gambit fizzled, and Hollywood arose in Southern California. An implicit warning for modern civic and business leaders emerged from this failed venture, one that Mayer’s comparison with present-day New Orleans demonstrates has gone largely unheeded. As the next chapter illustrates, the promises of accelerated development for the broader community have so far rung as hollow in the first decades of the twenty-first century as they did at the outset of the twentieth.

Mayer’s historical framework in this first chapter also serves a vital purpose in puncturing the mythology of Hollywood’s origin story. “This history is both true and false,” the author says of the lore of America’s film industry, because while enterprising individuals and geographic location did figure into its eventual settlement in Southern California, these accounts of Hollywood’s founding “do not take into account the roles of government officials or other economic and cultural elites in cities.”[4] Such a narrative also effaces the many histories of film economies in other areas, as well as the critical insights those successes and failures may yield. New Orleans’ past flirtation with early film pioneers is one such account, and Mayer’s first act contextualizes the claims of boosters, developers, and politicians within a reconstituted history of promises unrealized (and worse). However, the force of her argument really comes through as a rallying cry for media industry scholars and offers a point of departure for excavating the pasts of other places and their uneven relations with film industries. In this case, the specter of film’s fantastic promises set the stage for New Orleans’s ambivalent present-day entanglements with production.

Chapter 2, “Hollywood South,” sets about clarifying the terms and conditions of the complex modern relationship between Hollywood and Hollywood South. Mayer maintains that the film industry’s footprint is far more concrete and expansive than the “myth of [production’s] rootlessness and weightlessness” suggests.[5] This materiality and breadth form the crux of the author’s assertion that drawing together questions of industrial movement and tangible effects allows for a critical perspective on the “differentiated mobility” utilized by the industry to reorganize people and spaces.[6] Here, tourism and production align in their pursuit of publicly subsidized exceptionalist mythologizing of New Orleans to draw tourists and producers. They also both rely on the city’s colonial power relations—manifest in its racial and socioeconomic stratifications—for such pursuits.[7]

To this end, Mayer observes, film incentives have failed to establish a permanent hub for production and have instead created a para-industry predicated on the city’s malleability as a canvas. The efforts of politicians, business leaders, and other boosters to promote unique features (e.g., the French Quarter) and generic locales suggest that, in theory, the entire city is open for business and ready to accommodate productions set in New Orleans or anywhere else. In practice, privatization brought about by years of neoliberal governance enables industrial mobility while shaping a geography of racial and socioeconomic stratification. Affluent areas such as the Garden District wield far more power to restrict and profit from location shoots than poor sections of town, and industry investment has repeatedly favored already resource-rich neighborhoods.

The myth of mobility surrounding production in New Orleans, Mayer therefore asserts, does not account for the rigidness with which film-related development plays out in “The City That Care Forgot.” It disproportionately imposes on New Orleans’s poor and people of color by reconfiguring movement through public spaces (e.g., shutting down streets and neighborhoods for location shoots) with little to no input from residents or compensation for them (a stark contrast to producers’ relations with wealthier parts of town). It perpetuates gentrification and displaces vulnerable communities. Altogether, Mayer contends, the logic of Hollywood South is one of development packaging labor and capital as far-reaching stimuli across the city’s economy. In reality, she argues, its implementation sees upward redistributions of wealth and reorganizations of space that reinforce colonial power relations.

These ambivalences are detailed in Almost Hollywood’s exploration of the television series Treme (Eric Overmyer and David Simon, 2010–2013). Chapter 3 (“The Place of Treme in the Film Economy”) charts the ways in which residents interact with the show to negotiate feelings of home “even as its production became an alibi for the film economy’s roles in historical and spatial displacement.”[8] The show’s fidelity to New Orleans as place is often at the center of Mayer’s reception-focused methodology in this chapter. Through conversations with residents and Treme extras, responses to her reception study with local viewers of the show, and reactions during public screenings of the series, Mayer outlines the complex relationships surrounding Treme that coalesce into a shared archive of New Orleans as both home and history.

Mayer’s methods here expand upon the ethnographic dimensions of the previous chapter, particularly her exploration of residents’ engagement with reorganizations of space. In this chapter, her interviews and observations are especially fruitful in connecting broader policy considerations to nuanced modes of engagement with arguably the most sustained New Orleans–specific fictional media production of the twenty-first century. They reveal that Treme engages in a therapeutic archiving that intertwines the show’s evocations of post-traumatic emotional realism, viewer experiences of post-Katrina perpetual crisis, and the moral economy of defending a recovering New Orleans. Together this fuses modes of healing with forms of local boosterism—abetted by philanthrocapitalism and the further privatization of public resources—that (despite producers’ rhetoric to the contrary) are tinged with the same extractive and exploitative features of other runaway productions.[9]

Almost Hollywood, Nearly New Orleans adroitly probes The Crescent City’s ambivalent relation to its status as Hollywood South. For Mayer, the city occupies a liminal place vis-à-vis the industry. In one sense, it hangs in the balance between the promises of as-yet-unrealized production- related economic stimulus. In another, New Orleans is defined by an indeterminant status that swings between its desirability as a distinctive backdrop and its willingness to be a blank canvas for producers. The touted benefits of Hollywood South and production incentives across the country are legion, but their costs are often more elusive. Mayer’s book constitutes a timely contribution to the study of media industries for its thorough accounting of the debts incurred by a state like Louisiana and a city like New Orleans—and the unequal ways in which those burdens are distributed across racially and socioeconomically divided landscapes.

Justin Owen Rawlins is Assistant Professor of Media Studies and Film Studies at The University of Tulsa. His research explores, among other things, the development of Alaska’s unique media culture amidst its transition from territorial status to statehood and its ongoing negotiations of geographic isolation and environmental sovereignty.

Vicki Mayer, Almost Hollywood, Nearly New Orleans: The Lure of the Local Film Economy (Oakland: University of California Press, 2017), 5.

Jonathan Handel, “Film and TV Tax Credit Battle Heats Up across U.S.,” The Hollywood Reporter, July 19, 2018, https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/film-tv-tax-credit-battle-heats-up-us-1128027.

Mayer, Almost Hollywood, Nearly New Orleans, 17. Mayer adds that

at least on the surface, New Orleans and Los Angeles, as well as other cities in the South and West, offered the same economic potential for a new film economy. . . . When the Los Angeles boosters won out over competing cities, they succeeded in dominating the subsequent narrative of how film economies form. (23)

Bibliography

- Handel, Jonathan. “Film and TV Tax Credit Battle Heats Up across U.S.” The Hollywood Reporter, July 19, 2018. https://www.hollywoodreporter.com/news/film-tv-tax-credit-battle-heats-up-us-1128027.

- Mayer, Vicki. Almost Hollywood, Nearly New Orleans: The Lure of the Local Film Economy. Oakland: University of California Press, 2017.