Production Perspectives on Audience Engagement: Community Building for Current Affairs Television

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This article studies the practices and motivations of media producers to engage their audience in an audience community. Many media producers experience difficulties in engaging audiences, and community building seems to be a fruitful way to deal with this. Most empirical studies focus on the commercial value of communities, but this contribution studies the Flemish public service media program Vranckx as a case in point, using in-depth interviews, observations, and content analysis to assess the value of audience communities for Public Service Media (PSM). Results show that producers encourage different types of audience engagement, including immersive, interactive, and para-active engagement, to build and maintain an audience community. To do this, they integrate journalistic roles as observer, developer, facilitator, and curator within the community. Even though production practices show many similarities with commercial brand communities, PSM goals constitute central motivations, namely to decrease polarization and include different perspectives through dialogue in the audience community.

Keywords: Audience Engagement, Audience Community, Television, Public Service Media, Production Studies

Introduction

Media producers increasingly adapt the production process to engage audiences. However, many producers experience difficulties in achieving this, as they have to adapt to and compete with a range of media platforms and changing audience behavior.[2] Some scholars emphasize the value of community building in engaging audiences, but empirical work on how this can be achieved is limited and tends to focus on its commercial value.[3] Complementing existing literature, this article analyzes the practices and motivations of TV producers who engage in community building to encourage audience engagement beyond a commercial aim. A case study of current affairs program Vranckx on VRT, the Public Service Media (PSM) of Flanders (the northern, Dutch-speaking part of Belgium), aims to understand how and why community development may prove a fruitful way to engage the audience with PSM values.

Vranckx is a current affairs program that deals with international topics, focusing primarily on conflicts in the Middle East. Despite the fact that audiences tend to be less interested in foreign than in domestic news,[4] the program manages to attract a relatively large and interested audience. Moreover, discussions regarding the conflicts that the program covers tend to be heated and polarized. The social media platforms of Vranckx allow for a variety of opinions to be expressed, leading to a lively and interactive dialogue. Therefore, Vranckx constitutes an interesting case to analyze the way producers use an audience community to stimulate audience engagement.

Theoretically, we conceptualize engagement broadly, including rational and emotional processes, both visible and invisible, which is broader than definitions used in earlier studies into media production.[5] In order to study the variety of ways to engage audiences through creating a community, we apply insights from marketing studies as they have operationalized the concept of audience communities most thoroughly. However, contrary to marketing research, our study concentrates on production within the PSM context. Together, this leads to our central research question: What are the practices and motivations of producers to engage their audience in a community, and what is the potential of audience communities in a PSM production context?

To answer these questions, first, we theoretically explore the notions of audience engagement and audience communities as developed in media and marketing studies. This leads to a number of sub-questions, formulated in the methods section which, furthermore, discusses the production studies perspective we use to gain an in-depth understanding of the production process of media content and the motivations of media producers. This perspective considers the media production process as a cultural, complex, and interpretive process, which plays an important role in how meaning is constructed.[6] Subsequently, we discuss our findings related to Vranckx. This section is structured into three parts: the different kinds of engagement that producers encourage, the ways producers build a community, and the motivations of producers in relation to the PSM context. Based on the analysis of a specific case, the conclusion reflects on the wider significance of our findings, aiming to come to a more in-depth understanding of audience engagement within communities in media and production studies.

From Audience Engagement to Community Building

Audiences have many ways to engage with media content, such as watching content on different platforms, downloading or recording media content, liking, commenting on, and sharing content on social media, producing fan videos, or visiting an event. Engaging the audience is of particular importance in the context of PSM because one of their core tasks is to involve the audience in public debates as citizens.[7] However, television producers experience difficulties when engaging the audience as they have to adapt to and compete with many media platforms and outlets, primarily social media.[8] For example, Jackson’s fieldwork shows how British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) producers are doing some experiments to find out how to engage their audience with non-linear media and suggests the need for more interactive possibilities.[9] However, Van Es explains how producers have decreased the amount of visible audience engagement via social media in interactive television formats because they found the risk of quality loss in live television too high.[10] In addition, van Dijck and Poell discuss how PSM producers tried to incorporate public values when engaging their audience through social media, both in the production process and visibly in the television program.[11] However, due to the commercial nature of social media, they ended up using social media mostly for promotional reasons. These difficulties made scholars question how PSM can engage their audience nowadays and whether they should use social media to achieve this.

The majority of studies into audience engagement conceptualize the concept politically,[12] viewing engagement as a way to participate in the public sphere and question how voices in democracy can be heard and empowered.[13] Within this approach, engagement relates to visible and editorial input from the audience, similar to a large amount of studies into audience participation.[14] However, a number of empirical studies show that audiences are often invisible or not involved in actual editorial choices made in legacy media production. Instead, audiences are engaged in other ways, which are also significant and important in the production process.[15] As a result, the political conceptualization of engagement hides many production approaches to engage audiences. Therefore, this article applies a much broader definition.

We conceptualize audience engagement in a non-political way, including a broader range of audience involvement, based on the conceptualization of engagement by Evans[16] in the field of audience studies. First, Evans distinguishes between different forms of engagement which, next to rational and physical, includes emotional forms. The latter concerns feeling engaged and having an affective connection with media content, so it regards the different interests, feelings, and involvements of audiences as very important forms of engagement to take into account.[17] Next, Evans[18] distinguishes three types of engagement: immersive, interactive, and para-active engagement. Immersive engagement means focusing intensely on content, which implies that watching a television program and reading audience comments on Facebook constitute ways to engage, even though these are invisible. Importantly in this way, immersive engagement includes the “silent majority,”[19] that is, the large audience group which feels engaged but does not add visible contributions. Interactive engagement is a direct response to content and includes interaction with content, such as playing a game, liking a photo related to a TV program on Instagram, or discussing media content on Facebook with audience members or producers. Para-active engagement, finally, relates to “activities that happen around the content rather than in direct relation to it.”[20] This can imply the production of content independently from original content, such as creating program-related content on fan webpages or personal social media platforms. Some interactive and para-active forms of engagement can be classified under the political concept of engagement, because they give the audience some editorial power. Since all these activities suggest a clear division between producers and audience members, in this text, we use the term “audience” instead of user, prosumer, or active audience, acknowledging the broad range of engagements that the audience can have.[21]

We approach the broad notion of engagement from a production studies perspective, studying how and why producers create opportunities for different forms and types of engagement. Producers can motivate audience members to engage individually, by watching or searching extra content online, but much engagement is social,[22] including discussing content with someone, searching for extra fan-produced content online, or visiting an event and meeting up with other audience members. Approaching engagement as part of a group makes it a social act, which is further explored in this article through the concept of audience communities.

Scholars increasingly stress the value of audience communities as a way to engage audiences within television production processes.[23] They define an audience community as a network of engaged audience members who feel connected and interact with each other.[24] Audience communities can create community and alternative media, which concerns the participation of people from a community as essential to produce media.[25] However, the focus in this article is on the value of audience communities in the production process of mainstream public service television. Such communities can be a strategic resource to understand audience behavior and can strengthen audience engagement through a sense of ownership.[26] In addition, audience communities can help curate and share content on platforms such as social media, where social connections are central.[27]

Janssen[28] compared three television production processes that aimed to create audience communities. Even though the approaches and success of the three programs differed, the producers involved in each case think it is crucial that audiences can interact via online platforms so they obtain some editorial control, which can create a sense of ownership. At the same time, producers maintain editorial control over the television content. In this way, the audience community fits within existing routine structures in the production process, and the role of media producers as professionals remains very clear.[29]

Audience activities are of central importance to build and sustain such communities, but producers play a substantial role as well. Malmelin and Villi[30] argue that successful communities require four new practices from producers. The first is observing audience behavior and discussions across platforms, in order to sense who the people in the community are and what their needs are. Second, producers need to develop content for the audience to engage with, like providing interesting content and introducing new subject areas. Third, they must facilitate communication within the community by providing platforms that are easy to reach or ways for the audience to contact the producers. Fourth, producers should curate the dialogues and content to provide some direction, for instance, by selecting and recommending interesting content, posing a question, and taking part in conversations. These roles as observer, developer, facilitator, and curator can create the conditions for audiences to gain a sense of ownership which, in turn, contributes to a sense of engagement with a community.[31] Across a wide range of media companies, such activities are part of the job description of so-called “community editors,” “engagement editors,” or “social media editors.”[32]

These studies into building audience communities help to understand how production practices within legacy media are changing. In addition, to be able to understand in more detail successful production practices to build audience communities, empirical research in the field of marketing studies offers interesting insights. Audience communities and brand communities are quite similar in the sense that they both concern a group of people engaged with a certain product or content.[33] Therefore, in what follows, we explore what we can learn from the field of marketing studies to better understand audience communities in media production.

Within marketing studies, the concept of brand community is interpreted as a group of consumers who interact with each other about a brand in a certain context. Often, this context is provided by the brand itself, creating opportunities for consumers to share their interest, information, and knowledge. This results most frequently in a group of users who share how much they like a certain brand.[34] Most researchers analyze brand communities on online (social media) platforms.[35]

A community can help brands to build a strong, long-lasting, and engaged relationship with consumers,[36] but a community can only function if consumers appreciate its value. In a successful brand community, consumers wish to identify themselves with the brand publicly.[37] In addition, a community allows consumers to share their experiences and knowledge regarding the usage and quality of products.[38]

Several scholars have elaborated on specific ways to build a successful community. Hanna, Rohm, and Crittenden[39] argue that companies need to think comprehensively about their goals and their story, instead of simply copying online examples. In addition, they argue it is important to value social media within a media ecosystem, which means that legacy and social media are related and both need to be part of the community building. Social media, in particular, need to create intimacy and trust to build and maintain a strong community.[40]

A central issue to ensure a successful community is the cultivation of conversation among consumers.[41] This creates a risk as brands cannot control the public conversation among consumers: Consumer-to-consumer interaction can be negative about the brand, which decreases brand trust. This makes the conversation about the brand even more important than the initial message, and brands can act upon this in several ways.[42] First, observations of the interaction between consumers need to distinguish the different behaviors among consumers and on different platforms. Second, companies need to become part of the conversation and try to cultivate consumer interaction.[43] Besides producing content about the brand, companies also need to produce ways to continue the conversation. This is very similar to the four new practices that Malmelin and Villi[44] set out in media studies, observing, developing content, facilitating, and curating. However, Pitta and Fowler[45] add that brands need to tread carefully, as consumers do not wish the community to be too biased and promoting the brand. Third, companies must consider providing platforms and tools for consumers to create content. This is a more controversial suggestion in marketing, but Muniz and Schau[46] add that consumers are savvy about advertising styles and wish to participate.

Brand communities have the primary economic goal to increase profit, so they can clearly set out a strategy to earn as much money as possible and value the people in the community as consumers. However, PSM primarily have cultural and political goals. People in the community are conceived as citizens, which highlights their potential to be part of a constructive dialogue and pluralistic debate.[47] Like most PSM, Flemish public broadcaster VRT’s remit is to inform, inspire, and connect everyone in Flanders across all ages. The current VRT management contract (2016–2020), which stipulates the objectives and duties between the Flemish government and the VRT, includes the aim to be part of a democratic society by stimulating a public and pluralistic debate.[48] The management contract further states that it has the responsibility to increase media literacy related to digital media, considered vital for people to use media in a critical and active way.[49] However, Assmann and Diakopoulos[50] argue that the implicit motivation of media producers to engage audiences often is the branding of content, which illustrates the very thin line between marketing and journalistic goals. This article applies insights from marketing studies in a journalistic context, yet we remain mindful of the different goals of PSM, analyzing the value of a more community-centered approach to engage audiences in a PSM program.

Methods

This article draws on a case study of a single program, Vranckx, allowing for an in-depth analysis of the particularities and unique characteristics of its production process.[51] Vranckx can be considered a unique case to the extent that the production practices are not typical or representative of other current affairs programs in Flanders.[52] A case study enables the combination of multiple, complementary data sources.[53] In our study, a combination of interviews, observations, and content used and produced by producers and audiences were collected to study audience engagement and community building in the production process of Vranckx.

The theoretical framework and the case study lead to the following central research question: What are the practices and motivations of producers to engage their audience in a community, and what is the potential of audience communities in a PSM production context? To answer this question, three sub-questions are formulated:

- RQ1: How and why do producers motivate audience engagement in the production Vranckx?

This question specifically analyses the broad notion of engagement, including emotional and rational forms of engagement, and immersive, interactive, and para-active types of engagement.[54]

- RQ2: How and why do the producers construct a community in the production of Vranckx?

This question studies how journalistic roles, as formulated by Malmelin and Villi,[55] are integrated to develop a community and how the approach of Vranckx relates to the building of brand communities.

- RQ3: What is the value of a more community-centered approach to engage the audience in a PSM program?

This question focuses on the goals that are at the heart of community building in the production of Vranckx, and situates these within PSM goals.

The first author collected the data between January and April 2017. First, six interviews were conducted with most members of the editorial office: the presenter,[56] the editor in chief,[57] two online editors,[58] and two television editors.[59] The respondents have different functions but, as all are part of the creative team that conducts research and decides on content production, we refer to them as “producers.” Interviews were semi-structured around a few topics: production practices, audiences, audience engagement, and identity as part of PSM institution VRT. We did not ask the same questions in each interview but took a flexible and iterative approach, with questions gradually focused more on community building, a theme emerging from the first interviews.

Second, a six-day observation of the editorial practices, spread over the course of the interviews, allowed for a better understanding and contextualization of the examples and arguments the producers gave in the interviews. While this period was too short to fully adopt the insider perspective that ethnographic studies aim for,[60] it enabled us to acquire a sense of the daily practices, routines, and interactions between colleagues.

Third, we collected the content that the producers and audiences produced, in order to relate the production practices very closely to their results. This included a qualitative content analysis of the documentaries, online content, and other content produced between February and April 2017. It also included “paratexts”,[61] understood here as material used for production purposes, such as e-mails, annual reports, and the VRT management contract (2016–2020).

The interviews, field notes, content analysis, and paratexts were combined in an analysis in which the data were structured into three categories: approach to media production, integration of audience engagement, and integration of community building and its reasons. A further selection of central arguments in the interviews allowed for a comparison of the producers’ approach with theories in media and marketing studies. The concept of audience engagement was explored before and initially directed data collection, while the concept of community building came up inductively during the data collection and was subsequently used in the data analysis.[62] This combination of deduction and induction gave direction when approaching the editorial office, and allowed for flexibility to refocus on what was regarded as important by the producers themselves, which is crucial as this study aims to better understand producer perspectives.

Our analysis starts with a brief introduction of the editorial office of Vranckx, which then allows us to analyze how the producers encourage a variety of audience engagement, divided into immersive, interactive, and para-active forms of engagement. Next, we discuss how the different forms of engagement help to construct an audience community, analyzing how the new journalistic roles formulated by Malmelin and Villi[63] are integrated and comparing our observations to different marketing studies. Finally, we focus on the producers’ motivations for their approach toward engagement and community building.

Engaging the Audience

The editorial office of Vranckx is situated in the newsroom of the VRT. While the institution prioritizes television documentaries, the producers produce content across a broad range of platforms: “Officially, television is most central because that is how we get our budget, but we are content producers who work on a topic and intend to tell our stories in as many ways as possible” (Rudi Vranckx, presenter). Vranckx includes documentaries and news reports on television (an average of 350,000 viewers, market share of 14 percent), social media content on Facebook (82,000 members), Twitter (55,000 followers), and Instagram (5,000 followers), educational material, websites, books, and live talks. Therefore, producers identify their editorial office as a “hybrid project” (Anneleen Ophoff, online editor). As to content, all their output covers international current affairs topics. While lately they focused mainly on conflicts in the Middle East, they also covered other international issues, always with a focus on personal stories. The production of content across different platforms allows the producers to encourage audience engagement in a broad and varied way, both immersive, interactive, and para-active.

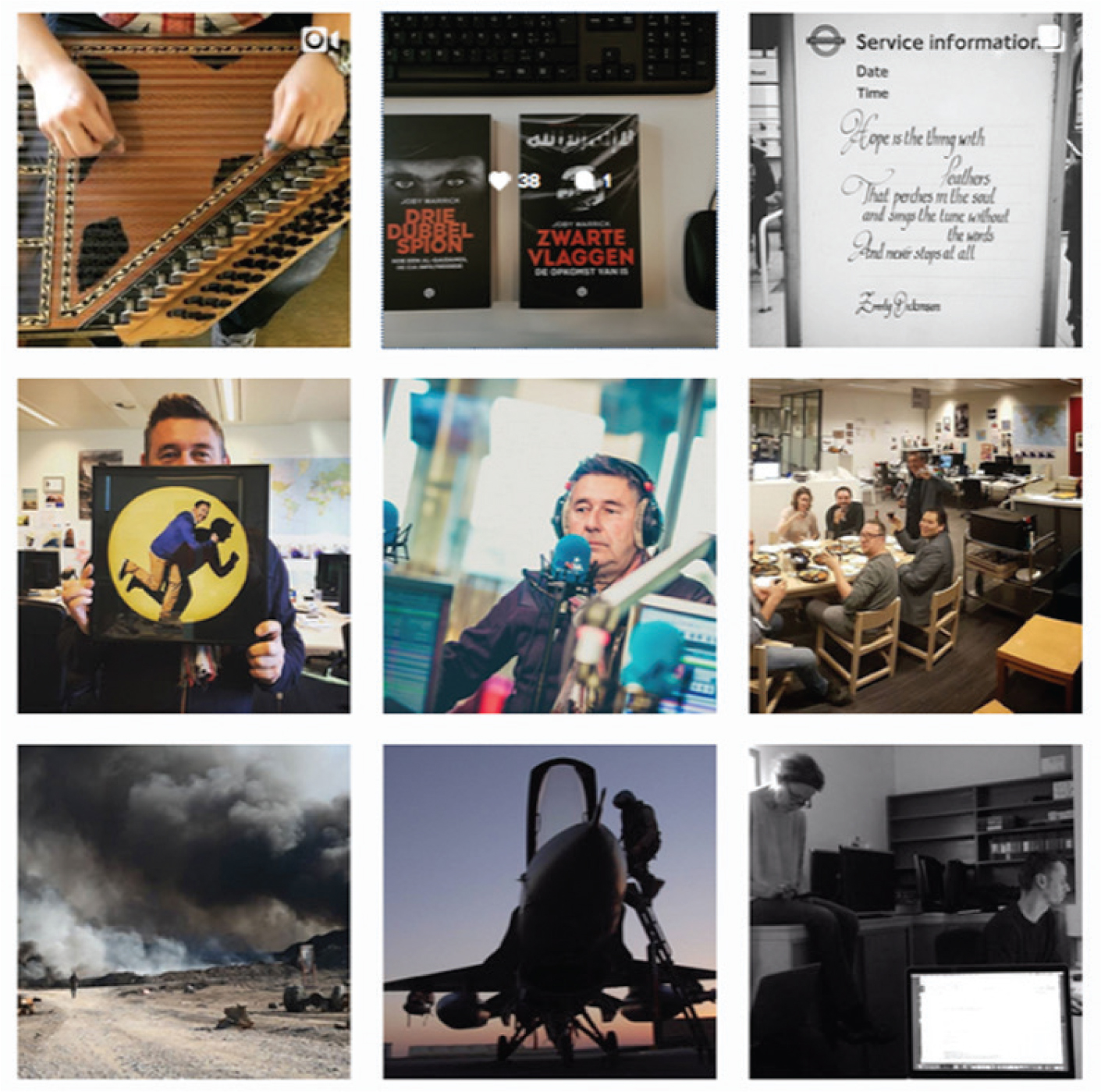

Immersive engagement is encouraged through all content, as it aims to generate interest in the topic. In this way, the producers try to engage the “silent majority”,[64] that feels engaged but does not add any visible input. They achieve this by visibly connecting all the platforms to the presenter, Rudi Vranckx, as a central figure and the program’s name sake. Rudi Vranckx is the presenter in the documentaries and a central figure in pictures on Instagram, asks questions in video clips on Facebook, and gives talks throughout Flanders (see Image 1).

Since he is always discussing international conflict topics, he is a specialist and is regarded as a trusted and recognizable guide. In this way, the producers aim to create a feeling of connection to the audience with the content that is produced, and even more so with the presenter (Image 2).

On some platforms, namely the documentaries, Twitter and Instagram, the producers focus exclusively on immersive engagement. They value the documentaries as a way to tell their own story, as a journalistic endeavor, allowing them to share their knowledge and insights. The audience is not addressed directly but people can feel engaged with the content. In that sense, the documentaries do not show or reflect explicitly upon the amount of audience engagement they create. On Twitter, the producers have observed that people who share or post content often do not aim for dialogue but simply wish to share their opinion. Therefore, the producers mainly spread news related to international conflicts on this platform. On Instagram, they use a different approach to engage the audience, showing their own production process by posting images of behind-the-screen practices.

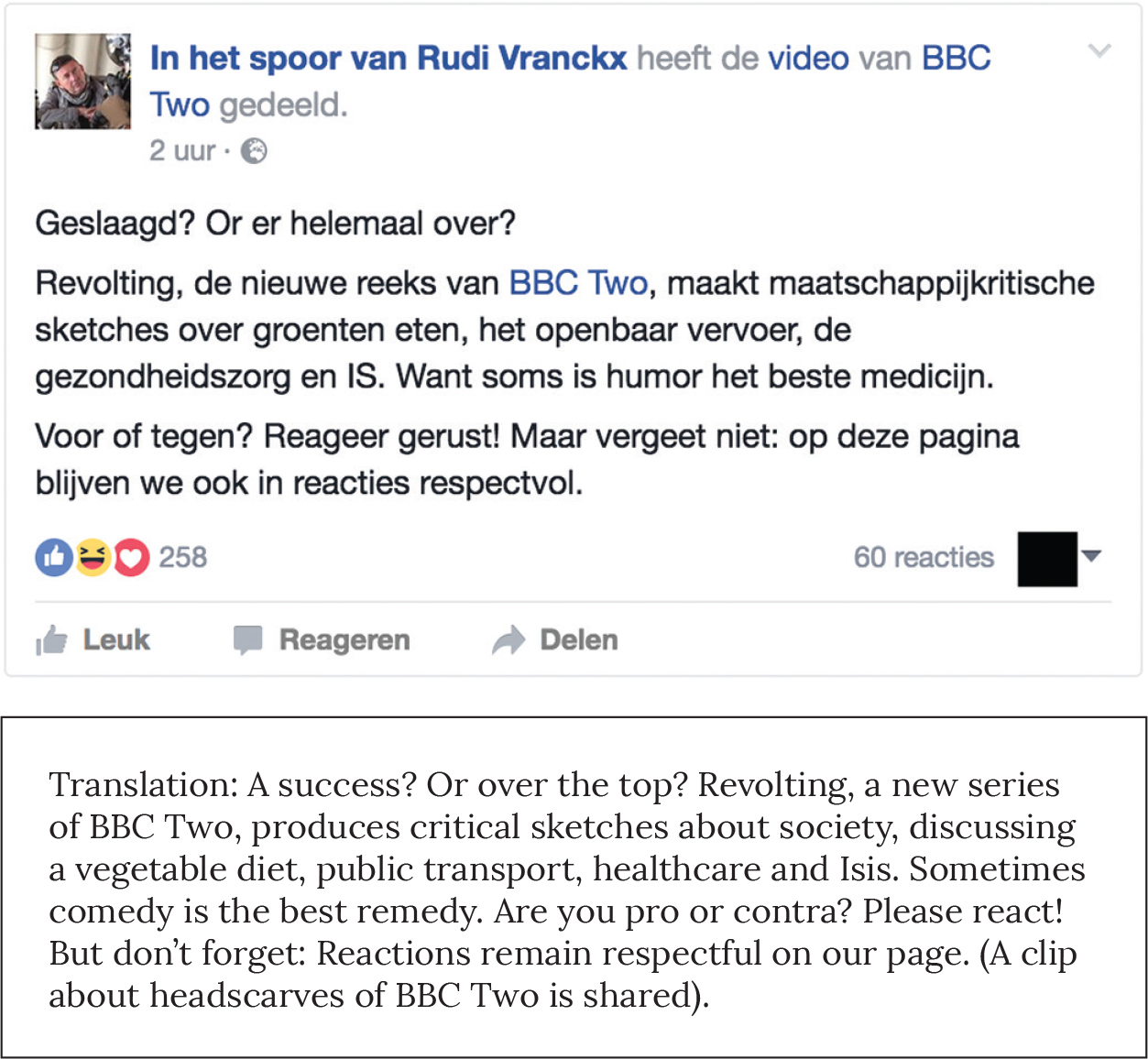

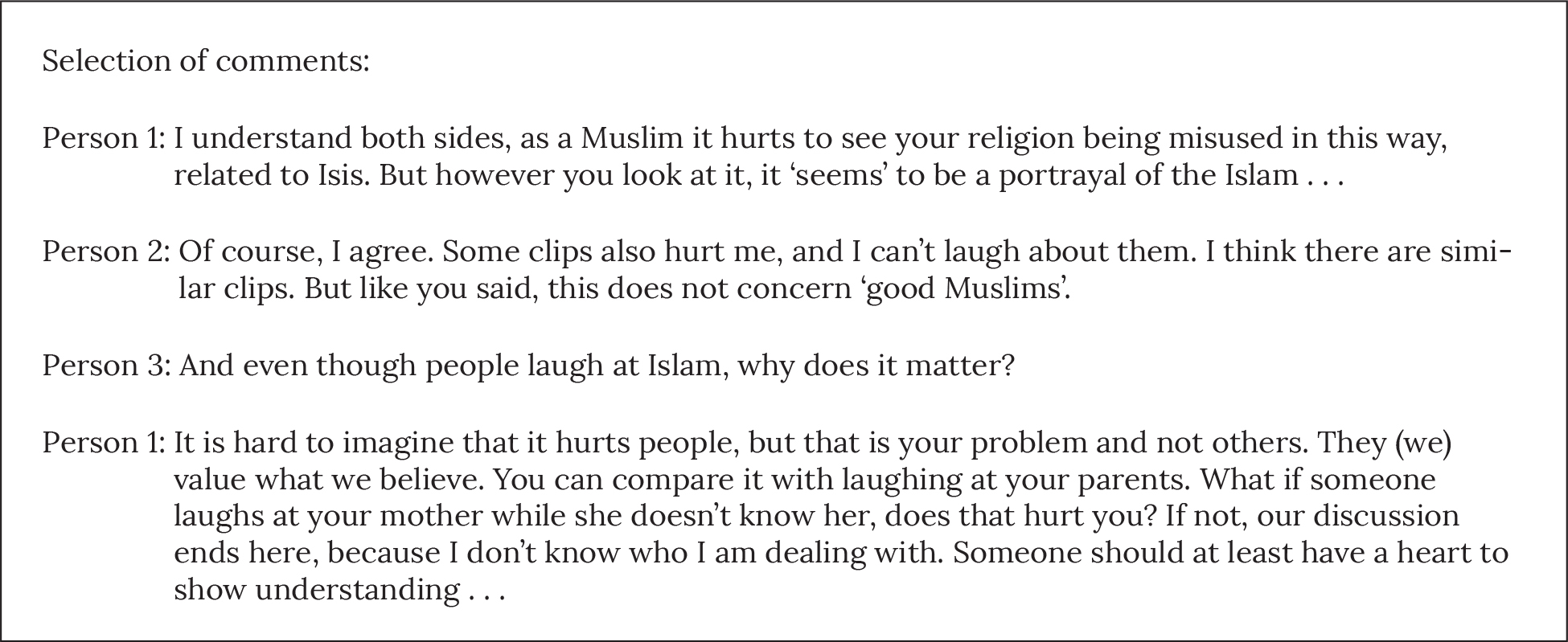

On other platforms, producers engage the audience in interactive and para-active ways. The producers encourage audience engagement most interactively through their Facebook-page called In het spoor van Rudi Vranckx (Following Rudi Vranckx), with different types of content, such as advertising their content, posing questions, encouraging a dialogue, and explicitly inviting different perspectives (see Image 3).

This question is an example where people started interacting, resulting in sixty comments. A short extract of these comments (Image 4) shows how people are listening to each others’ opinions.

To encourage a constructive dialogue and prevent polarization, the producers have set up rules of good behavior: “We apply stricter rules than most fora, simply because we aim to keep our page up to a good level. [ . . . ] We encourage well-argued opinions” (Vincent Merckx, online editor). Those rules are quite basic, explaining that no discrimination, swearing or spamming is allowed. The producers experience that the quality of the dialogue increases when the audience interacts. However, sometimes producers still remove comments or memberships of the Vranckx Facebook page when someone breaks the rules.

In other projects, producers encourage para-active engagement, in which audience engagement is not directly related to the content of Vranckx and takes on a life of its own, without a central role for the producers as content providers. However, producers keep their facilitating and curating journalistic role. For example, the producers have launched a website project called 100stemmen.be (100voices.be) to collect a hundred Muslim voices. Flemish Muslims were able to post a video with a story about their life. This was a reaction to the limited and problematic representation of the Muslim world in Flemish media, primarily focusing on conflicts in the Middle East. Another project that encourages para-active engagement is a Facebook group called “The nomads” consisting of a group of young travelers and filmmakers who blog about their journey. Most of them receive support of producers to produce a long documentary in the country they are visiting. While this group constitutes a big community in Facebook terms, with 11,000 members, it does not significantly increase audience revenue. In line with PSM’s goal of contributing to audience formation, but quite original for current affair productions, Vranckx also produces educational material for elementary and high schools, to discuss the topics they have covered in their program. More projects such as these have been built over the years to empower people and encourage a dialogue.

Across the different platforms, a major part consists of immersive and emotional engagement. Research into political engagement would not consider this as engagement because there is no shift in editorial power.[65] However, including the concept of immersive engagement illustrates how non-political forms of engagement can lead to creating an environment with which the audience wishes to feel connected and identifies with. This, in turn, creates an atmosphere in which the audience wishes to interact and produce content.

Building a Community

Such an environment, inciting audience engagement, can be considered as an audience community, since a community means that a number of audience members feel connected and can interact with each other in a network.[66] Two main aspects explain how the producers of Vranckx were able to create and maintain such an audience community. On the one hand, the interplay of different types of engagement allowed for the creation of a sense of belonging, intimacy, trust, and ownership. On the other hand, the producers were able to integrate different journalistic roles, such as observer, developer, facilitator, and curator within their production context. Much of their approach is similar to creating brand communities.

Interplay of Forms of Engagement

In the first part of this analysis, we discussed how producers engage their audience in different ways, including immersive, interactive, and para-active types of engagement. Immersive engagement allows to create a sense of belonging,[67] intimacy,[68] and trust,[69] which are mentioned as important aspects to create a community in marketing studies. Examples of this are positioning the presenter as a central figure and showing behind-the-screen practices, because the audience recognizes the presenter and it almost seems as if the audience could join him. Another example is the rules of behavior on Vranckx’ Facebook page. These allowed for a community feeling because with these rules producers encourage audience members to feel as if they were in a specific “place” belonging to Vranckx, which creates space that can be trusted. At the same time, interactive and para-active engagement allow for creating ownership,[70] by creating content[71] and sharing knowledge,[72] which are also mentioned as important aspects for brand communities. An example is the website 100stemmen.be (100voices.be), built by the producers to collect 100 videos from Flemish Muslims, because they felt that these voices are not heard enough in Flemish media. Importantly, the combination of and interplay between these different kinds of engagement enable to build a successful community.

Despite these different ways of trying to engage the audience within a community, the documentaries do not differ in presentation from documentaries without an engaged community. However, the community is an advantage to the producers because audience members sometimes raise interesting ideas or suggestions. In this sense, the producers do not structurally aim for specific ways of audience participation, but the community enables an engaged relationship between the producers and the audience who can listen to each other’s ideas. Compared to the risk to loose quality when visibly integrating audiences in the television program identified by other production studies,[73] this community approach toward audience engagement seems more suitable from a production perspective. In this way, engagement can add to pre-existing production practices instead of making them more complicated which would result in a high “failure” rate. Even though this may limit participatory options, only in addition to pre-existing production practices, the community allows to expand its use from branding goals to journalistic value.

Journalistic Roles

The journalistic roles formulated by Malmelin and Villi[74] are mostly integrated within the production practices of Vranckx by two online producers who work on its online platforms. Every day, the producers observe who is visiting their social media platforms and what input they provide, such as likes, shares, and interactions. Observer is one of the new journalistic roles that Malmelin and Villi[75] describe, in which a close observation of audiences helps to identify who the audience is and what their needs are. Moreover, in marketing studies, Hanna et al.,[76] among others, argue that observation helps to distinguish between different audience behaviors. The observation helps the Vranckx producers to decide how and what to produce for the online channels, using a different focus for each platform.

When they produce content, producers aim to profit from the affordances of each platform, which includes creating interesting content that the audience can engage with in different ways, such as reading, interacting, and/or producing content: “When you use a platform, you play with the rules of that platform” (Merckx). Producing content in this way is what Malmelin and Villi[77] mean with the new role of producers as developers.

Next, the producers provide different platforms and ways to engage, such as setting up rules on Facebook and building websites for audience content, facilitating an environment to engage. This is a third producer role identified by Malmelin and Villi,[78] facilitator. Finally, producers recommend content, ask questions to encourage audience response, and interact with the audience. This is the role of curator,[79] which is also considered important in building a brand community, to keep the brand “alive.”[80] Malmelin and Villi[81] explain that conversations among consumers are of central importance to a community.

The community of Vranckx does not only exist in an online environment, but offline as well, through the live talks of the presenter in schools, municipality centers, and cultural centers, even before the launch of social media. Speaking with the audience during a Q&A is a productive way to observe what people care about, which is one of the journalistic roles to build a community.[82] At the same time, the talks facilitate and curate a way for people to meet other audience members and discuss the content, which reflect the other journalistic roles to create a community.[83]

The educational material is another example of offline community building. The material offers a selection of content accompanied by explanations and potential topics to discuss in schools. This is an encouragement to really think about the topics and discuss them, illustrating the journalistic role of curation in which para-active engagement is supported as part of community building practices.[84]

By integrating observation, development, facilitation, and curation within their practices, the Vranckx producers created the conditions for the audience to engage both online and offline in a community. The processes are of central importance to the program and illustrate many similarities with marketing studies regarding the building of brand communities.

The producers describe the way they integrate these new practices to build a community as a relatively natural process of trial and error. Different from other newsroom productions at VRT, the producers explain that they do not organize their daily practices according to routines, which allows them to integrate new ideas more easily. They regard innovation as an important part of the production process, also allowing them to search for new, more, and better ways to tell their stories. The editorial office of Vranckx is positioned as an autonomous unit within the newsroom, physically positioned in a separate corner: “We compare it to a special forces unit who has been dropped somewhere and do their own thing” (Vranckx). Logistically, the producers with different functions sit next to each other, which creates easy communication within the editorial team. At a more macro-level, Vranckx profits from a relative small media market, which allows the producers to manage the amount of content within the community. In this way, they have provided a context which allows the community to grow quite organically, strongly based on intuitiveness, implementing strategies via both online and offline media, and adding expertise where and when it is necessary.

Motivations for Community Building

The motivations of the producers to construct a community are based on a central goal that was at the heart of the production process from the very start: to reduce polarization in society, to motivate people to listen to different perspectives, and to create understanding across people with different ideas and beliefs:

My biggest concern, which is always in the back of my mind, is an “us” versus “them” divide which only seems to increase. Social media sometimes play a devastating role, separating people instead of connecting them. I want to bridge and question that gap. That is my priority. (Vranckx)

They started to receive an increasing amount of audience questions and reactions via social media and talks across Flanders, due to the topics they discussed, specifically concerning conflicts in the Middle East and the so-called “European refugee crisis”. The producers wished to enable the audience to have a constructive dialogue, based on their underlying aim to listen to different perspectives: “We work with quite tense news topics, concerning terrorist attacks, radicalization etcetera. It is very easy to shape stereotypes, but it is much better for everyone in society to talk about it” (Ophoff). Therefore, the producers decided to structurally offer platforms for the audience to engage in different ways, which organically grew into a community. “For certain topics, a debate is very important, communities and a multimedia approach make that possible” (Vranckx). In this sense, the journalistic responsibility is strongly related to an educational role: “We teach people to think about certain topics and to formulate an opinion about it” (Ina Maes, editor-in-chief).

These goals clearly fit within the PSM ideal to engage the audience as citizens instead of consumers. Part of their task is to engage the audience in public debates.[85] The production process of Vranckx illustrates how an audience community is built to achieve these goals, as it can connect people with shared interests and stimulate them to listen to different perspectives and enter a dialogue. However, motivating a dialogue with different perspectives remains a challenge, because of the commercial nature of social media.

Poell and Van Dijck[86] explain how PSM producers experience this risk in using social media platforms, and the producers of Vranckx experience this as well. Their next challenge is how to deal with platform algorithms, which calculate who gets to see what content, based on their surfing history. These algorithms involve the risk of creating filter bubbles, which implies that audience members only receive specific content that confirms their norms and values. This contradicts the producers’—and wider PSM’s[87]—core goal, which increases the risk of polarization. So in order to reach their PSM objectives, they need to think about adding non-commercial platforms as well. In the case of Vranckx, they built their own websites, created educational material and presented talks across Flanders. These are examples of achieving their goals through non-commercial platforms.

Another reason to engage audiences in a community across different platforms is to increase the number of viewers which, in a PSM context, is not the same as increasing revenue—the key driver for commercial media. However, using social media is delicate as the commercial nature of many of the platforms used to form a community raises the question whether PSM should use these.[88] It appears, however, that to engage audiences in a community that revolves around PSM values, the solution is not to avoid social media altogether. As our case illustrates, there is a potential for PSM in using audiences communities for non-commercial goals. The approaches used in Vranckx do not differ very much from those used for advertising goals, showing a great number of similarities with the ways in which brand communities are built in a commercial environment, as discussed in marketing studies. However, the underlying goals are different, and they underpin the production choices leading to the building of an audience community.

Because of the unique context of Vranckx, it is hard to predict how the production practices of Vranckx can be replicated. However, other editorial offices are not supposed to just copy practices, but to depart from their central goals and choose the best practices accordingly, critically taking into account those goals. Moreover, in combination with visible forms of engagement and providing ownership, we learn that invisible immersive engagement, feeling affection for and guidance through content are of major importance and should not be underestimated in production practices and production studies.

Conclusion

A media context in which audiences can engage in a wide range of ways poses challenges for television producers to adapt and to compete with other media in successfully engaging the audience.[89] Some scholars point out that creating a community can be a successful way to engage the audience.[90] Building on these insights, this article discussed how and why an audience can be engaged in a community, in order to find out its potential within a PSM context.

Our production analysis of current affairs program Vranckx in Flanders shows that the producers create a production context in which innovation is important and a limited amount of routines allow integration of journalistic roles in which producers can encourage audience engagement in a community. The producers observe the audience up close, develop content for the audience to engage with, facilitate communication platforms, and curate content by stimulating interaction and inspiring discussions, important to create engagement within a community.[91]

Moreover, an interplay between immersive, interactive, and para-active engagements is important for the community to exist. To achieve this variety of engagement, the producers use many platforms and do not focus exclusively on television and social media, but on talks and educational material as well. Their approach encourages a sense of belonging, intimacy, and trust, also for the “silent majority”[92] that does not add any visible input. To a large extent, this is realized by positioning the presenter as a central figure across all platforms. In addition, there are a variety of ways for the audience to interact and produce content, which creates a sense of ownership.

Audience communities and commercial brand communities present many similarities. Drawing on marketing studies proves to be a fruitful way to better understand how communities can be created. While the practices are similar, and the producers of Vranckx use the community to increase their audience (not unlike brand communities and commercial media), their production practices are more centrally rooted in the PSM aim to decrease polarization and to include different perspectives. They see dialogue with and among the audience as an important way to achieve this goal, accomplished by building an audience community. Even though the Vranckx producers are aware of risks such as the danger of filter bubbles and inappropriate behavior of some audience members, which can lead to an increase of polarization, these do not outweigh the potential gains.

Considering the broader contribution of this study to the field of production studies, our conceptualization of engagement is broader than that of other studies into audience engagement.[93] Adding emotional and non-visible engagement illustrates that these are of significant importance to how producers can constructively involve the audience in their production process because it creates the fundaments and an environment for visible engagement. Moreover, while former studies into audience communities mostly focused on social media, we included all platforms used by the producers. In these ways, our study provides a more inclusive image of engagement and audience communities from a production perspective.

Based on this, we suggest further research into other cases using our broad conceptualization of engagement, in order to include the forms and types of engagement that are not visible within the specificities of different contexts. Moreover, our analysis was limited to practices and perspectives of producers at a micro-level within the editorial office, which limited the analysis of more structural and organizational explanations. Therefore, another suggestion for further research is to include a macro-level organization perspective, in which production practices are contextualized within organizational and policy structures and aims. Overall, however, we believe that our study illustrates the value of in-depth, contextualized case studies of audience engagement from a production perspective, which help to understand why certain television programs manage to build an engaged audience community.

Marleen te Walvaart is a PhD student and teaching assistant at the University of Antwerp (Belgium) in the department of communication studies. Within the Media, Policy, and Culture research group her doctoral research studies television production processes and the integration of the audience from the perspective of producers. Alexander Dhoest is Professor in Communication Studies at the University of Antwerp (Belgium), and head of the research group Media, Policy, and Culture. His research focuses on the connection between media (in particular television) and national, ethno-cultural, and sexual identities. Hilde Van den Bulck is full professor of communication studies and head of the Department of Communication at Drexel University (PA). She combines complimentary expertise in media structures, processes, and policies, focusing on public service media, with expertise in media culture.

José van Dijck and Thomas Poell, “Making Public Television Social? Public Service Broadcasting and the Challenges of Social Media,” Television & New Media 16 (2, February 1, 2015): 148–64, https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476414527136; David Domingo, “Interactivity in the Daily Routines of Online Newsrooms: Dealing with an Uncomfortable Myth,” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13 (3, April 2008): 680–704, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00415.x; Henry Jenkins, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green, Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture (London: NYU Press, 2013); Authors, 2017.

Karin Assmann and Nicholas Diakopoulos, “Negotiating Change: Audience Engagement Editors as Newsroom Intermediaries—International Symposium on Online Journalism,” ISOJ Journal 7 (1, 2017): 25–44; Nando Malmelin and Mikko Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work: Emerging Practices,” Journalism Practice 10 (5, July 3, 2016): 589–607, https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1036903; Mikko Villi, “Social Curation in Audience Communities: UDC (User-Distributed Content) in the Networked Media Ecosystem,” Participations: The International Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, Special Section: Audience Involvement and New Production Paradigms 9 (2, 2012): 614–31.

Amy Mitchell et al., “2. Publics around the World Follow National and Local News More Closely than International,” January 11, 2018, http://www.pewglobal.org/2018/01/11/publics-around-the-world-follow-national-and-local-news-more-closely-than-international/.

Annette Hill and Jeanette Steemers, “Special Section: Media Industries and Engagement: Introduction,” Media Industries 4 (1, 2017): 1–5, http://dx.doi.org/ 10.3998/mij.15031809.0004.105.

Timothy Havens, Amanda D. Lotz, and Serra Tinic, “Critical Media Industry Studies: A Research Approach,” Communication, Culture & Critique 2 (2, June 2009): 234–53, https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-9137.2009.01037.x; Jennifer Holt and Alisa Perren, eds, Media Industries: History, Theory, and Method (Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009); Horace Newcomb and Amanda Lotz, “The Production of Media Fiction,” in A Handbook of Media and Communication Research, ed. Klaus Bruhn Jensen (Abingdon: Routledge, 2002), 62–77.

Jenkins, Ford, and Green, Spreadable Media; Harvard Moe, Thomas Poell, and José van Dijck, “Rearticulating Audience Engagement: Social Media and Television,” Television & New Media 17 (2, February 1, 2016): 99–107, https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476415616194.

Jackson, “Participatory Public Service Media: Presenters and Hosts in BBC New Media,” 2009; Jackson, “Participating Publics: Implications for Production Practices at the BBC,” 2013.

Karen van Es, “Social TV and the Participation Dilemma in NBC’s The Voice,” Television & New Media 17 (2, February 1, 2016): 108–23, https://doi.org/10.1177/ 1527476415616191.

Andrea Cornwall, Democratizing Engagement: What the UK Can Learn From International Experience (London: Demos, 2008); Peter Dahlgren, Media and Political Engagement: Citizens, Communication, and Democracy, Communication, Society and Politics (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009); Sonia M. Livingstone, Audiences and Publics: When Cultural Engagement Matters for the Public Sphere, Changing Media-Changing Europe Series, vol. 2 (Bristol: Intellect, 2005); Moe, Poell, and van Dijck, “Rearticulating Audience Engagement.”

Cornwall, Democratizing Engagement; Skylla. J. Janssen, “Publieksparticipatie Beteugeld: Boundary Work En Publieksparticipatie in de Professionele Praktijken van Nederlandse Televisiemakers” (Amsterdam: University of Amsterdam, 2017); Faltin Karlsen et al., “Non-Professional Activity on Television in a Time of Digitalisation More Fun for the Elite or New Opportunities for Ordinary People?,” Nordicom Review 30 (1, 2009): 19–36; Livingstone, Audiences and Publics.

David Domingo et al., “Participatory Journalism Practices in the Media and Beyond: An International Comparative Study of Initiatives in Online Newspapers,” Journalism Practice 2 (3, October 2008): 326–42, https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780802281065; Janssen, “Publieksparticipatie Beteugeld”; Authors, 2018.

Elisabeth Evans, “Negotiating ‘Engagement’ within Transmedia Culture” (paper presented at the Summer School in Clinical Studies, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, Finland, June 13–15, 2016).

Dahlgren, Media and Political Engagement; Evans, “Negotiating ‘Engagement’ within Transmedia Culture”; Hill and Steemers, “Special Section.”

Evans, “Negotiating ‘Engagement’ within Transmedia Culture.”

Renee Barnes, “The Ecology of Participation,” in SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, ed. Tamara Witschge et al. (Los Angeles: SAGE, 2016), 179–91.

Evans, “Negotiating ‘Engagement’ within Transmedia Culture,” 13.

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work”; Jose Manuel Noguera Vivo et al., “The Role of the Media Industry When Participation Is a Product,” in Audience Transformations: Shifting Audience Positions in Late Modernity, ed. Nico Carpentier, Kim Christian Schrøder, and Lawrie Hallett, Routledge Studies in European Communication 1 (NY: Routledge, 2014), 172–87; Villi, “Social Curation in Audience Communities.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Carpentier, “The On-Line Community Media Database RadioSwap as a Translocal Tool to Broaden the Communicative Rhizome,” 2007; Paulussen and D’Heer, “Using Citizens for Community Journalism: Findings from a Hyperlocal Media Project,” 2013; Reader and Hatcher, “Foundations of Community Journalism,” 2012.

Noguera Vivo et al., “The Role of the Media Industry When Participation Is a Product”; Villi, “Social Curation in Audience Communities.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Assmann and Diakopoulos, “Negotiating Change”; Steve Paulussen, “Innovation in the Newsroom,” in SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, ed. Tamara Witschge et al. (Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016), 192–206.

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Mohammad Reza Habibi, Michel Laroche, and Marie-Odile Richard, “The Roles of Brand Community and Community Engagement in Building Brand Trust on Social Media,” Computers in Human Behavior 37 (2014): 152–61, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.016; Dennis A. Pitta and Danielle Fowler, “Online Consumer Communities and Their Value to New Product Developers,” Journal of Product & Brand Management 14 (5, August 2005): 283–91, https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420510616313; Melanie E. Zaglia, “Brand Communities Embedded in Social Networks,” Journal of Business Research 66 (2, February 2013): 216–23, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.07.015.

René Algesheimer, Utpal M. Dholakia, and Andreas Herrmann, “The Social Influence of Brand Community: Evidence from European Car Clubs,” Journal of Marketing 69 (3, July 1, 2005): 19–34, https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.3.19.66363; Susan Fournier and Jill Avery, “The Uninvited Brand,” Business Horizons 54 (3, May 2011): 193–207, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.001; Habibi, Laroche, and Richard, “The Roles of Brand Community and Community Engagement in Building Brand Trust on Social Media”; Pitta and Fowler, “Online Consumer Communities and Their Value to New Product Developers”; Zaglia, “Brand Communities Embedded in Social Networks.”

Algesheimer, Dholakia, and Herrmann, “The Social Influence of Brand Community”; Fournier and Avery, “The Uninvited Brand”; Richard Hanna, Andrew Rohm, and Victoria L. Crittenden, “We’re All Connected: The Power of the Social Media Ecosystem,” Business Horizons 54 (3, May 2011): 265–73, https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.007; Zaglia, “Brand Communities Embedded in Social Networks.”

Algesheimer, Dholakia, and Herrmann, “The Social Influence of Brand Community”; Fournier and Avery, “The Uninvited Brand.”

Habibi, Laroche, and Richard, “The Roles of Brand Community and Community Engagement in Building Brand Trust on Social Media”; Pitta and Fowler, “Online Consumer Communities and Their Value to New Product Developers.”

Habibi, Laroche, and Richard, “The Roles of Brand Community and Community Engagement in Building Brand Trust on Social Media”; Hanna, Rohm, and Crittenden, “We’re All Connected.”

Habibi, Laroche, and Richard, “The Roles of Brand Community and Community Engagement in Building Brand Trust on Social Media”; Hanna, Rohm, and Crittenden, “We’re All Connected”; Albert M. Muñiz and Hope Jensen Schau, “Vigilante Marketing and Consumer-Created Communications,” Journal of Advertising 36 (3, October 2007): 35–50, https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367360303; Zaglia, “Brand Communities Embedded in Social Networks.”

Hanna, Rohm, and Crittenden; Zaglia, “Brand Communities Embedded in Social Networks.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Pitta and Fowler, “Online Consumer Communities and Their Value to New Product Developers.”

Muñiz and Schau, “Vigilante Marketing and Consumer-Created Communications.”

VRT management contract (2016) “Beheersovereenkomst 2016-2020 tussen de Vlaamse Gemeenschap en de VRT,” 6.

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Alan Bryman, Social Research Methods, 5th ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016); Winston Tellis, “Application of a Case Study Methodology,” The Qualitative Report 3 (3, September 1, 1997): 1–19.

Marleen te Walvaart, Alexander Dhoest and Hilde Van den Bulck, “Production Perspectives on Audience Participation in Television: On, beyond and behind the Screen,” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, online first (January, 2018), https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517750362.

Robert K. Yin, Case Study Research: Design and Methods, 4th ed., Applied Social Research Methods, vol. 5 (Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2009).

Evans, “Negotiating ‘Engagement’ within Transmedia Culture.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Interview conducted with Rudi Vranckx, March 28, 2017, Brussels.

Interview conducted with Ina Maes, 24 April, 2017, Brussels.

Interviews conducted with Vincent Merckx, March 8, 2017, Brussels and Anneleen Ophoff, February 1, 2017, Brussels.

Interviews conducted with Jan Vleugels, March 28, Brussels and 2017 Jeroen Vissenaekens, 25 April, 2017, Brussels.

David M. Fetterman, “Ethnography,” in The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, ed. Lisa Given (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2008), http://knowledge.sagepub.com/view/research/n150.xml.

Jonathan Gray, Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts (NY: NYU Press, 2010).

Michael Quinn Patton, Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods (Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2002).

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Cornwall, Democratizing Engagement; Janssen, “Publieksparticipatie Beteugeld”; Karlsen et al., “Non-Professional Activity on Television in a Time of Digitalisation More Fun for the Elite or New Opportunities for Ordinary People?”; Livingstone, Audiences and Publics; Moe, Poell, and van Dijck, “Rearticulating Audience Engagement.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Algesheimer, Dholakia, and Herrmann, “The Social Influence of Brand Community”; Fournier and Avery, “The Uninvited Brand.”

Habibi, Laroche, and Richard, “The Roles of Brand Community and Community Engagement in Building Brand Trust on Social Media.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Muñiz and Schau, “Vigilante Marketing and Consumer-Created Communications.”

Habibi, Laroche, and Richard, “The Roles of Brand Community and Community Engagement in Building Brand Trust on Social Media”; Pitta and Fowler, “Online Consumer Communities and Their Value to New Product Developers.”

Dijck and Poell, “Making Public Television Social?”; Janssen, “Publieksparticipatie Beteugeld”; van Es, “Social TV and the Participation Dilemma in NBCs the Voice.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Hanna, Rohm, and Crittenden, “We’re All Connected”; Zaglia, “Brand Communities Embedded in Social Networks.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Moe, Poell, and van Dijck, “Rearticulating Audience Engagement”; van Es, “Social TV and the Participation Dilemma in NBCs The Voice.”

Malmelin and Villi, “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work.”

Bibliography

- Algesheimer, René, Utpal M. Dholakia, and Andreas Herrmann. “The Social Influence of Brand Community: Evidence from European Car Clubs.” Journal of Marketing 69, no. 3 (July 1, 2005): 19–34. https://doi.org/10.1509/jmkg.69.3.19.66363.

- Assmann, Karin, and Nicholas Diakopoulos. “Negotiating Change: Audience Engagement Editors as Newsroom Intermediaries—International Symposium on Online Journalism.” ISOJ Journal 7, no. 1 (2017): 25–44.

- Barnes, Renee. “The Ecology of Participation.” In SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by Tamara Witschge, Chris. W. Anderson, David Domingo, and Alfred Hermida, 179–91. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016.

- Bryman, Alan. Social Research Methods. 5th ed. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2016.

- Cornwall, Andrea. Democratising Engagement: What the UK Can Learn From International Experience. London: Demos, 2008.

- Dahlgren, Peter. Media and Political Engagement: Citizens, Communication, and Democracy. Communication, Society and Politics. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009.

- Dijck, José van, and Thomas Poell. “Making Public Television Social? Public Service Broadcasting and the Challenges of Social Media.” Television & New Media 16, no. 2 (February 1, 2015): 148–64. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476414527136.

- Domingo, David. “Interactivity in the Daily Routines of Online Newsrooms: Dealing with an Uncomfortable Myth.” Journal of Computer-Mediated Communication 13, no. 3 (April 2008): 680–704. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1083-6101.2008.00415.x.

- Domingo, David, Thorsten Quandt, Ari Heinonen, Steve Paulussen, Jane B. Singer, and Marina Vujnovic. “Participatory Journalism Practices in the Media and Beyond: An International Comparative Study of Initiatives in Online Newspapers.” Journalism Practice 2, no. 3 (October 2008): 326–42. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512780802281065.

- Es, Karen van. “Social TV and the Participation Dilemma in NBCs the Voice.” Television & New Media 17, no. 2 (February 1, 2016): 108–23. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476415616191.

- Evans, Elisabeth. “Negotiating ‘Engagement’ within Transmedia Culture.” Paper presented at the Summer School in Clinical Studies, University of Jyvaskyla, Jyvaskyla, Finland, June 13–15, 2016.

- Fetterman, David M. “Ethnography.” In The SAGE Encyclopedia of Qualitative Research Methods, edited by Lisa Given. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2008. http://knowledge.sagepub.com/view/research/n150.xml.

- Fournier, Susan, and Jill Avery. “The Uninvited Brand.” Business Horizons 54, no. 3 (May 2011): 193–207. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.001.

- Gray, Jonathan. Show Sold Separately: Promos, Spoilers, and Other Media Paratexts. New York: NYU Press, 2010.

- Habibi, Mohammad Reza, Michel Laroche, and Marie-Odile Richard. “The Roles of Brand Community and Community Engagement in Building Brand Trust on Social Media.” Computers in Human Behavior 37 (2014): 152–61. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.chb.2014.04.016.

- Hanna, Richard, Andrew Rohm, and Victoria L. Crittenden. “We’re All Connected: The Power of the Social Media Ecosystem.” Business Horizons 54, no. 3 (May 2011): 265–73. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.bushor.2011.01.007.

- Havens, Timothy, Amanda D. Lotz, and Serra Tinic. “Critical Media Industry Studies: A Research Approach.” Communication, Culture & Critique 2, no. 2 (June 2009): 234–53. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1753-9137.2009.01037.x.

- Hill, Annette, and Jeanette Steemers. “Special Section: Media Industries and Engagement: Introduction.” Media Industries 4, no. 1 (2017): 1–5. http://dx.doi.org/10.3998/mij.15031809.0004.105.

- Holt, Jennifer, and Alisa Perren, eds. Media Industries: History, Theory, and Method. Chichester: Wiley-Blackwell, 2009.

- Janssen, Skylla J. “Publieksparticipatie Beteugeld: Boundary Work En Publieksparticipatie in de Professionele Praktijken van Nederlandse Televisiemakers.” University of Amsterdam, 2017. https://dare.uva.nl/search?identifier=48d2120d-c3db-4249-889f-b38ff5ddb51c.

- Jenkins, Henry, Sam Ford, and Joshua Green. Spreadable Media: Creating Value and Meaning in a Networked Culture. London: NYU Press, 2013.

- Karlsen, Faltin, Vilde Schanke Sundet, Trine Syvertsen, and Espen Ytreberg. “Non-Professional Activity on Television in a Time of Digitalisation More Fun for the Elite or New Opportunities for Ordinary People?” Nordicom Review 30, no. 1 (2009): 19–36.

- Livingstone, Sonia M. Audiences and Publics: When Cultural Engagement Matters for the Public Sphere. Changing Media-Changing Europe Series, vol. 2. Bristol: Intellect, 2005.

- Malmelin, Nando, and Mikko Villi. “Audience Community as a Strategic Resource in Media Work: Emerging Practices.” Journalism Practice 10, no. 5 (July 3, 2016): 589–607. https://doi.org/10.1080/17512786.2015.1036903.

- Mitchell, Amy, Katie Simmons, Katerina Eva Matsa, and Laura Silver. “2. Publics around the World Follow National and Local News More Closely than International,” January 11, 2018. http://www.pewglobal.org/2018/01/11/publics-around-the-world-follow-national-and-local-news-more-closely-than-international/.

- Moe, Harvard, Thomas Poell, and José van Dijck. “Rearticulating Audience Engagement: Social Media and Television.” Television & New Media 17, no. 2 (February 1, 2016): 99–107. https://doi.org/10.1177/1527476415616194.

- Muñiz, Albert M., and Hope Jensen Schau. “Vigilante Marketing and Consumer-Created Communications.” Journal of Advertising 36, no. 3 (October 2007): 35–50. https://doi.org/10.2753/JOA0091-3367360303.

- Newcomb, Horace, and Amanda Lotz. “The Production of Media Fiction.” In A Handbook of Media and Communication Research, edited by Klaus Bruhn Jensen, 62–77. Abingdon: Routledge, 2002.

- Noguera Vivo, Jose Manuel, Mikko Villi, Nora Nyiro, Emiliana De Blasio, and Melanie Bourdaa. “The Role of the Media Industry When Participation Is a Product.” In Audience Transformations: Shifting Audience Positions in Late Modernity, edited by Nico Carpentier, Kim Christian Schrøder, and Lawrie Hallett, 172–87. Routledge Studies in European Communication 1. New York: Routledge, 2014.

- Patton, Michael Quinn. Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods. Thousand Oaks, CA: SAGE, 2002.

- Paulussen, Steve. “Innovation in the Newsroom.” In SAGE Handbook of Digital Journalism, edited by Tamara Witschge, C. W. Anderson, David Domingo, and Alfred Hermida, 192–206. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2016.

- Pitta, Dennis A., and Danielle Fowler. “Online Consumer Communities and Their Value to New Product Developers.” Journal of Product & Brand Management 14, no. 5 (August 2005): 283–91. https://doi.org/10.1108/10610420510616313.

- Tellis, Winston. “Application of a Case Study Methodology.” The Qualitative Report 3, no. 3 (September 1, 1997): 1–19.

- Villi, Mikko. “Social Curation in Audience Communities: UDC (User-Distributed Content) in the Networked Media Ecosystem.” Participations: The International Journal of Audience and Reception Studies, Special Section: Audience Involvement and New Production Paradigms 9, no. 2 (2012): 614–31.

- Walvaart, Marleen te, Alexander Dhoest, and Hilde Van den Bulck. “Production Perspectives on Audience Participation in Television: On, beyond and behind the Screen.” Convergence: The International Journal of Research into New Media Technologies, online first, Online first (January 2018). https://doi.org/10.1177/1354856517750362.

- Yin, Robert K. Case Study Research: Design and Methods. 4th ed. Applied Social Research Methods, vol. 5. Los Angeles, CA: SAGE, 2009.

- Zaglia, Melanie E. “Brand Communities Embedded in Social Networks.” Journal of Business Research 66, no. 2 (February 2013): 216–23. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.jbusres.2012.07.015.