Cartoon Wasteland: Remediating and Recommodifying Archival Media in Disney’s Epic Mickey

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Epic Mickey and Prosthetic Memory

It is also productive to consider how the game as a digitextual site of “interactive plenitude” and nostalgic return to an “analog dream” fits within the broader popular construction of the Wii platform itself. As Zach Whalen and Laurie N. Taylor note, when the Wii gaming system was first introduced in 2006, many game enthusiasts opted for the console over its competitor PlayStation 3 “not for its graphics or even its motion-based input, but rather for the ease with which it allows players to re-experience classic games like Super Mario Brothers (1985) and Donkey Kong (1985) through its Virtual Console” which offered “downloadable emulations” of classic Nintendo games.[31] Thus, the idea of offering the player a nostalgic return to an obsolete past is built directly into the console’s design. On a broader level, Whalen and Taylor argue that there is an inherent process of remembering and nostalgia built into the video game medium as it necessitates both a repetitive form of gameplay that “relies on players’ memory and a technology that is itself built using computer memory.”[32] Furthermore, if, as they argue, video games “offer experiences of remembering that may be personal or cultural,” how a game such as Epic Mickey activates these mnemonic processes through the player’s engagement with the text is central to understanding the game’s discursive relationship to memory, history, and nostalgia.[33]

Epic Mickey’s nostalgic repurposing of Disney history is explicitly built into the game’s central narrative conceit: the game frames Oswald as Mickey Mouse’s older half-brother, and Mickey’s trajectory through Wasteland is structured as a sort of family reunion. Indeed, from the outset of the acquisition, Disney framed Oswald’s return to the studio as a nostalgic homecoming and return to the Disney “family.” In a 2006 Disney press release announcing the Oswald acquisition, Bob Iger described the deal as bringing Oswald back to “the home of his creator” and references Walt Disney’s daughter, Diane Disney Miller’s approbation for the deal, thus adding a further extratextual layer to the discourses of family and homecoming.[34]

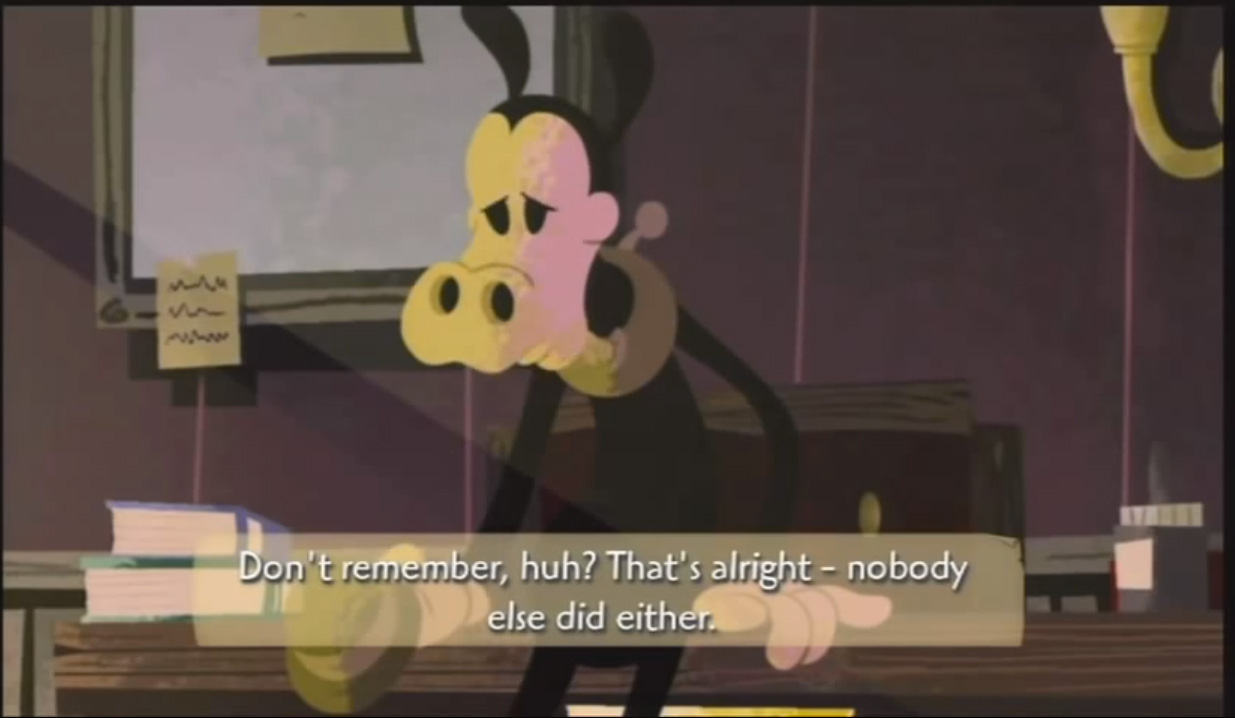

Furthermore, mirroring what we might call the game’s commercial objective of putting archival properties back into commercial circulation, the player-as-Mickey’s goal in the game is, quite explicitly, to remember and recuperate archival Disney media that the average player is likely to have forgotten or perhaps never heard of at all (figs. 5–6). The game’s lead designer, Chase Jones, neatly illustrates this point in one of the game’s special features segments: “The story around Epic Mickey is about remembering these forgotten characters. Not only is Mickey doing that, but the player is doing that as well . . . as you, the player, go through you’re learning about characters you may have never seen before from the Disney Archives and now you’re remembering them as well as allowing Mickey to remember them.” This idea of “remembering” that which one never knew speaks to the ways in which the game not only plays on Disney fans’ knowledge of and nostalgia for obsolete Disney media (such as retired characters and defunct theme-park attractions), but also invokes a type of what Alison Landsberg terms “prosthetic memory” work. For Landsberg, prosthetic memories are facilitated by the technologies of mass culture and thus are “memories which do not come from a person’s lived experience in any strict sense. These are implanted memories [that] unsettle the boundaries between real and simulated.”[35] Landsberg asserts that prosthetic memories are reflective of “the power of the mass media to create experiences and to implant memories, the experience of which we have never lived,”[36] and she emphasizes the utopian potential of such mass cultural texts to facilitate collective memory projects. Indeed, she argues that “capitalist commodification and mass culture have created the potential for a progressive, even a radical, politics of memory.”[37]

In Epic Mickey’s case, however, it is difficult to separate the game’s evocations of the past from its commodification, its privatization of memory in the service of the corporate objectives of remediation. The game engages the player in memory work that cultivates affective ties to Disney archival media via the player-as-Mickey’s prosthetic memories of forgotten characters, linking the process of consumption to emotional engagement. The game does not simply tell the player about these forgotten characters: it kinesthetically and emotionally involves her in remembering them from Mickey’s subject position as a friend and family member. As an interactive, participatory medium, the video game also offers the potential for creating more deeply affective connections and emotional identification with Epic Mickey’s archival media than a DVD collection or other media text that operates through, to use Linda Hutcheon’s terms, “showing” or “telling” modes of narrative engagement.[38] The game thus arguably performs a pedagogical function, engaging the player in interactively learning about the game’s cultural objects through an affective process of remembering with, and as, Mickey.

Simultaneously, however the game’s operative principle of choice and consequence troubles such a mnemonic trajectory. Spector emphasizes that the game does not “tell you [the player] that family and friends are important, but ask[s] you the question and then let[s] you interact with them [the characters].” While, in order to win the game, the player must defeat the Shadow Blot and facilitate Mickey and Oswald’s reconciliation, throughout the game she can choose to complete or ignore numerous other missions that involve responding to characters’ requests for help. Similarly, because she can choose to paint and restore Wasteland or use thinner to hasten its disintegration, the player’s interactions with Disney history, and the degree to which she participates in remembering and restoring it, are not strictly circumscribed. Thus, while the game constructs affective relationships to Disney media by suturing the player to Mickey’s subject position, it also interpellates the player as archivist, granting her the choice of determining which elements of the game to remember and restore and which to “forget” or discard to “the dustbin of history.”[39]

Yet the seemingly ambivalent or transgressive politics of this archival and memory work are arguably recuperated at the game’s conclusion, when the player is directly confronted with the material consequences of her aggregate of choices. Following the restoration of order to the narrative world, players are presented a series of cut scenes that reflect the results of their decisions throughout the game. These scenes, tailored to the player’s playstyle, show how choices to accept or ignore missions to help secondary characters have positively or negatively impacted these characters’ lives. Although Spector emphasizes that there is no “good” or “bad” way to play the game, these scenes cement the game’s linkage of consumption, archiving, and memory by building in emotionally cathartic reinforcements for restorative players and suggesting how those that have chosen to discard missions—and, by extension, Disney archival properties—have punished others. As a result, on an ideological level, Epic Mickey facilitates the generation of polyvalent prosthetic memories, while implicitly rewarding players invested in rehabilitating Wasteland’s commercially and aesthetically remediated properties. Thus, if according to Landsberg, prosthetic memory’s cultural work involves “chang[ing] a person’s consciousness” in a way that might “enable ethical thinking and the formation of previously unimagined political alliances,” Epic Mickey channels this prosthetic memory work toward generating previously unexploited affective and consumer relationships with old Disney media in a new commercial context.[40]