The Culture of Poverty and Adoption: Adoptive Parent Views of Birth Families

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information)

: This work is protected by copyright and may be linked to without seeking permission. Permission must be received for subsequent distribution in print or electronically. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu for more information.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Abstract

This study used data from 15 in-depth interviews to better understand how perceptions of birth families by White adoptive parents rely on and challenge cultural perspectives of poverty. Findings show the complexity of their views: even when adoptive parents recognize structural causes of poverty, they tend to rely on the idea that birth parent poverty results from inadequate choices made by individuals. Findings have implications for agency practice, relationships with birth families and adoptee identity.

Keywords: Adoption, adoptive parents, birth parents, poverty, colorblind racial ideology, culture of poverty.

Adoption and economic disparity are intertwined by who typically places their children for adoption and those who have the economic resources to adopt them (Quiroz, 2007a). The number of children placed for adoption is linked to factors such as political circumstances, government regulations, stigma attached to “illegitimacy” and economic inequities where those with fewer financial resources and those who live in unstable countries and countries with high poverty rates are more likely to place (Gailey, 2010). Thus, family formation through adoption (i.e., domestic public, domestic private, and international) is entangled with class factors. Little is known about how adoptive parents view the biological parents of their children and how those views are influenced by perceptions of class and poverty. This study used data from 15 in-depth interviews to better understand how adoptive parent perceptions of birth families reinforces and challenges cultural perspectives of poverty.[1] Findings have implications for how children view adoption and their biological families, child identity, relationships between birth and adoptive families for those with open adoptions, and agency practices.

Literature Review

The Culture of Poverty

Culture of poverty arguments focus on group differences in culture, values, and genetics causing the circumstances and outcomes of poverty such as crime, low education levels, and high unemployment (Lewis, 1959; Moynihan, 1969). These ideas stem from the notion that the U.S. is a meritocracy, meaning it has “a social system where individual talent and effort, rather than ascriptive traits, determine individuals’ placements in a social hierarchy” (Alon & Tienda, 2007: 489). Believing in a meritocracy allows people to rationalize away inequality, blaming individuals for poverty rather than larger systems of privilege and disadvantages. The ideas of meritocracy are part of the dominant way people understand race in the U.S. It is often labeled “colorblind racial ideology,” where racism is seen as an issue of the past and the world if viewed through a supposed race-neutral or colorblind lens. This ideology allows people to explain racial inequality as the result of individual lack of effort, choosing not to invest in human capital, making poor choices, and having “bad” values (Bonilla-Silva, 2003; Gallagher, 2003).

Studies find that the general public relies on these cultural explanations to explain poverty (McDonald, 2001; Shaw and Shapiro, 2002). Shaw and Shapiro (2002) found that 40% of people of any race in their sample blamed individuals for their financial position and thought that those experiencing poverty could/should work harder or “do something” to bring themselves out of poverty. Many believe that those living in or near poverty are doing so because they have chosen not to invest in their education or skills, do not work hard enough or take advantage of the opportunities in society, or do not value education or hard work (Iverson & Armstrong, 2006).

Opinions about poverty are also racialized with 40% of people thinking that Black and Hispanic people are lazy (Shaw and Shapiro, 2002). McDonald (2001) had similar findings where 46.4% of White people in their sample explained Black inequality as the result of “lack of motivation,” and 31.2% used the same explanation for Hispanic inequality. These opinions illustrate how cultural arguments are tied to colorblind racial ideology and used to explain away racial inequality as natural; the idea being that racial/ethnic minority groups do not achieve higher status as a group because of negative or misplaced group values and behaviors (Bonilla-Silva, 2003).

The Case of Adoption

Adoption choices are made within particular constraints of adoptive parent characteristics—such as socioeconomic status, marital status, and sexual orientation—which effects the characteristics of the children available to potential parents to adopt (e.g. their gender, race, and nationality, and if they have special needs; Stolley, 1993; Feigelman and Silverman, 1997). For example, international adoption is expensive, while domestic public adoption through the foster care system is free regardless of child age or other characteristics (Maldonado, 2006). Each country also has its own regulations, limiting adoption options for older parents, single people, and gay and lesbian couples in particular (Maldonado, 2006). In recent years, the top source countries for adoptions in the U.S. were China (5,453 in 2007), Guatemala (4,728 in 2007; legislation in December 2007 discontinued new applications), Ethiopia (1,255 in 2007), and Russia (970 in 2011; Bureau of Consular Affairs, & U.S. Department of State, 2011; Selman & Heitfield, 2009).

Adoption is linked to both economic inequality and race as indicated by the children placed and their corresponding monetary values where White infants are in highest demand and the most expensive and Black children are disproportionally available through public adoption and the least expensive (Baccara, Collard-Wexler, Felli, & Yariv, 2010; Quiroz, 2007a). In the U.S., about 15 percent of children are Black, yet Black children account for 32% of those in foster care (Evan B. Donaldson Institute, 2008). While there are a variety of factors that influence options available to adoptive parents, “adopting children of color (or not adopting them) is seen as a matter of individual taste and lifestyle as color-blind individualists look to transracial, intercountry and minority adoption as partial solutions to poverty and family disruption” (Quiroz, 2007b: 58). This perpetuates culture of poverty arguments by assuming that removing children from families is a solution to poverty; removing children implies that the families they are born into are inadequate to raise them. Thus, even when structural factors, such as birth parent poverty, are recognized they tend to be attributed to the failures of “poor,” “underdeveloped,” countries. The focus on failures means that connections are lacking to larger economic systems that lead to placements by disempowered birth mothers and give more privileged adoptive parents access to children (see Briggs & Marre, 2009 for information the larger system; Dowling & Brown, 2009; Quiroz, 2007b).

Attitudes and opinions about birth parents

Research finds that birth parents are often viewed as irresponsible, particularly those in the U.S. (Gailey, 2010). Miall and March (2005) found that people framed fatherhood as a choice and thought that lack of economic security or ability to provide was a good reason to place a child for adoption. “Women characterized unwed birth fathers choosing adoption as irresponsible and un-caring. Men were less judgmental, characterizing these birth fathers as either too young to understand the full implications of fatherhood or not financially capable of fulfilling their paternal responsibility” (Miall and March, 2005; 543). Even though the connection is not explicitly made, past research has shown a reliance on cultural arguments to explain birth father decisions to place rather than structural barriers such as lack of access to education, steady employment, or assistance (Miall and March, 2005).

Opinions about those that place may influence the narratives that adoptive parents create and tell their child about their birth parents (Volkman, 2006). Adoptees “must decide what it means to be connected to both an adoptive and birth family and integrate their adoption experience into a coherent adoptive identity narrative. This process does not occur in a vacuum; it occurs in daily social interactions with important others, especially family members” (Von Korff & Grotevant, 2011: 393). Gailey (2010) found that parents who adopted internationally thought that their White or “closer to White” (i.e., racial identities that are not White or Black) children came from “better stock” with “greater moral fiber” than children placed in the US who are predominantly Black (p100). Those adopting oversees from Eastern European countries in particular created images of birth mothers from “good” families who accidently got pregnant, while those from Latin America were portrayed as having a lot of children that could not be provided for financially. Women who placed children for adoption in the U.S. “were characterized as less moral, less enterprising, and less deserving of compassion than poor mothers in other countries” (Gailey, 2010: 101).

While previous research has provided information on general attitudes towards adoption and opens the door to understanding adoptive parent choices, few studies have been done to specifically understand how adoptive parent perceptions of birth parents reinforce and challenge culture of poverty arguments. Understanding these perceptions has implications for adoptive parent and child relationships with birth families, adoptee perceptions of birth parents, and adoptee identity (Grotevant, Dunabar, Kohler, & Esau, 2000).

Methods

This study draws from 15 in-depth interviews and is designed to understand how White adoptive parents perceive and portray their child’s birth parents.

Sample

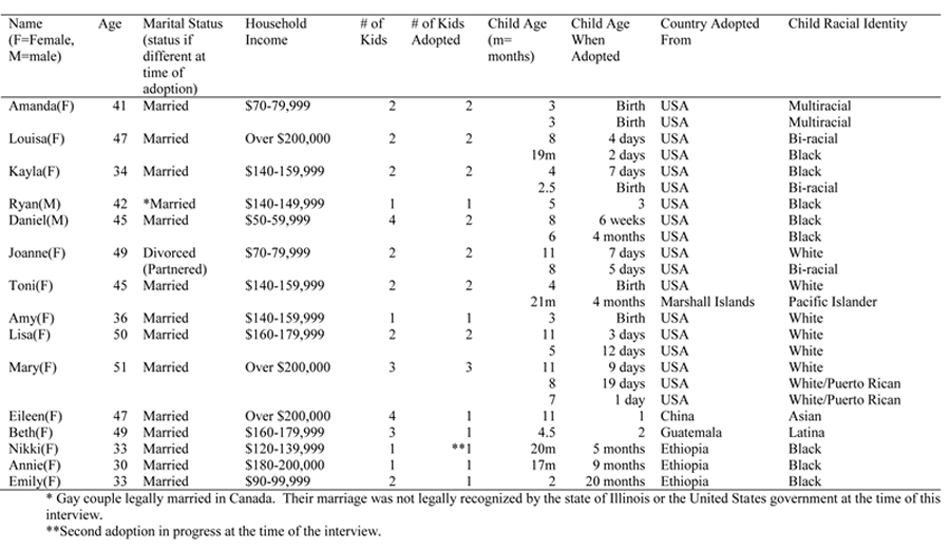

Fifteen semi-structured, in-depth interviews were conducted with White parents living in a large Midwestern city who had adopted a child in the past 10 years. Twelve women in the sample were in heterosexual marriages and one was a lesbian single woman who was partnered at the time of adopting. The sample included two men: a heterosexual married man and a gay married man.[2] The purposive sampling was designed to achieve variation in types of adoption, characteristics of adopted children (e.g., nationality, race, gender, and age at adoption), and participant/parent characteristics while keeping parent race constant and limiting time since adoption (Berg, 2009; Maxwell, 1996). All of the participants identified as White: one woman was Puerto Rican ethnicity and identified as White racially and one person was partnered with a man originally from Mexico. The remaining participants identified as non-Hispanic White with non-Hispanic White partners. Age of participants ranged from 30 to 51 years old, with an average age of 42 and the sample consisted mostly of college educated parents. All participants who self-identified as White were retained. The focus was intentionally on White parents because most adopters in the U.S. are White and to control some sample variation because of the varied structural limitations those choosing adoption face based on their marital status, sexual orientation, and socio-economic status (Bartholet, 1991). The current study draws on data from a larger project. Parents who had already adopted were interviewed because the adoption process is dynamic and parents may change their willingness to adopt children with certain characteristics before an adoption is finalized (see Table 1).

The 15 families included a total of 32 children, 24 of whom were adopted. Twelve of the parents adopted transracially and three adopted White children. Six of the families adopted internationally from China, Ethiopia, Guatemala, and the Marshall Islands. Eight of the families adopted through public domestic adoption (i.e., the Department of Child and Family Services, DCFS) and one used private domestic adoption. Fifteen of the 24 adopted children were identified by the participating parent as either Black/African American, Non-White Hispanic/Latino, or Asian/Pacific Islander and two of the remaining White children were ethnically Puerto Rican, but were racially identified by their parent as White.

Data Collection

Participants were recruited through flyers sent to adoption agencies and support groups, advertisements posted to a free public advertising venue (www.craigslist.com), neighborhood online groups for parents, and online support groups designated specifically for multiracial and adoptive families. The call for participants asked for White parents who had adopted a child in the past 10 years to spend 45 minutes to an hour discussing their experiences with the adoption process.[3] Five of the participants were the result of snow-ball sampling, meaning they were friends or acquaintances of someone who had already been interviewed. Four participants responded to calls posted to online neighborhood groups, three of the participants were recruited from online groups for multiracial families, two through personal extended networks (a friend of a friend or colleague), and one responded to the call for participants posted to Craig’s List. Two potential participants were unable to schedule a time to be interviewed and were not included in the sample.

All participants were interviewed at a public location of their choosing or their place of employment between June and August of 2010. Interviews were audio-recorded with the permission of participants. The semi-structured interview guide included questions about the decision to adopt, the adoption process, available options, choices made, geographic areas considered, demographic preferences and reasons for their preferences, and struggles and joys related to adopting (Berg, 2009). Participants also filled out a short questionnaire with demographic information (e.g., age, educational attainment, race, and nationality of origin) of each family member, relationship status (current and at the time of each adoption), household income, and religion. Beyond a cup of coffee, participants were not provided incentives or payment. Interviews lasted between 45 minutes and an hour and a half.

Analytic Approach

Digital audio recordings were transcribed word-for-word and saved as Word files resulting in almost 400 pages of single-spaced data that was imported into visual qualitative data management software (Atlas.ti). Each transcript was analyzed using a constant comparison analysis approach where portions of data were coded using deductive and inductive codes, then compared for similarities and emerging codes (Berg, 2009; Leech & Onwuegbuzie, 2007). For example, segments of data were coded for overarching codes such as specific child characteristics (e.g., age, gender, race, nationality, health, and disability) and for various parent characteristics. Other codes included any mention of desired characteristics, reason or decision to adopt, availability/options presented/ and limitations adoptive parents faced, concerns pre and post adoption, and connections between adopting and life choices. Close readings of transcripts and the identification of key phrases led to further revision of the code list (Berg, 2009; Ryan & Bernard, 2003). The findings for this paper draw on segments of transcripts coded for why the child was placed for adoption and any mention of the biological family of origin. Responses that fit the criteria were examined in the display stage in the network view tool in Atlas.ti, which allowed for axial coding by systematically going through each of the statements associated with these codes/categories and visually sorting them into sub-categories or themes to examine how adoptive parents perceive and portray birth parents (Attride-Stirling, 2001; LaRossa, 2005; Maxwell, 1996; Ryan & Bernard, 2003). The extracts used in the findings represent examples of each emerging sub-category or theme. All names have been changed along with any information that could compromise participant confidentiality.

Results

How parents perceive their child’s birth family is complex. When asked why their child was placed for adoption, adoptive parents in this sample discussed factors related to birth mothers including inability to care, abandonment, health issues such as drug and alcohol use, financial instability, age, relationship/marital status, and the circumstances of the birth mother’s pregnancy (e.g., non- consenting sex). Adoptive parent perspectives illustrate the complexity of adoption as they relied on (1) cultural arguments of birth parent irresponsibility and choice, while (2) also recognizing some systemic structural limitations beyond birth parent control, such as legal limitations and poverty.

The Role of Choice

Respondents often focused on biological parent choice in placing or relinquishing parental rights. Dina was a married mother of two adopted children: an eight year old biracial daughter and a Black daughter who was 19 months old at the time of the interview. Both of her children were adopted domestically as infants. When asked what, if any, concerns she had prior to adopting, Dina said:

I had this really difficult time accepting the fact that I was taking a baby away from her biological mother; the first time [I adopted, it was] devastating to me. And our adoption representative, counselor, was great with us. And you know she basically said you have to understand this is not your choice, this is the birth mother’s choice. This is what she wants for her child, so even though you’re feeling uncomfortable about [it], it’s not your place to let that get in the way of your decision [or] get in the way of what’s going on. You need to be really clear that she is doing this because she wants to do it.

Adoptive parents often focused on the role of choice, particularly the birth mother’s choice. This example shows how some parents perceived the focus on choice being used by the agency counselor to rationalize adoption and diminish any feelings of guilt the adoptive parent may experience. While adoptive parents were making a choice to adopt, they were told by agency counselors that the decision was first and foremost the birth parents to make. It is unclear if parents would have perceived birth parents as choosing to place had it not been for the influence of social workers and adoption counselors. Just as Quiroz (2007a) has found that the language used by agencies may affect the language used by adoptive parents, so too may the agency worker influence perceptions that adoptive parents have of birth parents.

Another example of this theme was from Lynn, a married mother of three daughters who were adopted domestically at birth; a White 11 year old, and 8 year old and 7 year old daughters who were identified by their mother as White racially and Puerto Rican ethnically. Lynn stressed the role of agencies in promoting choice, particularly in regards to shaping her opinions of the birth parents. She said:

[The agency] really teach[es] you to learn, to think that birth parents are a loving part of the adoption process. I think before [adopting] I would never have been able to articulate that. These are people who have made a very big choice, a loving choice. Saying, I can’t take care of this child, I’m going to find somebody who can. And that their devotion and connection to that child never ends even though they’ve placed the child.

Both of these examples illustrate the focus on birth parent choice to place their child for adoption, as well as, the role of the agency in stressing this choice.

Courage and Altruism

Along with a focus on the role of birth mother choice to place, the theme of courage and altruism was prevalent in the perceptions that adoptive parents had of birth parents. The example from Lynn (above) also shows how birth parents were portrayed as courageous, devoted, and loving for making the “choice” to terminate parental rights and place their child for adoption.

Jackie was a married woman with two White children adopted domestically as infants; an 11 year old son and a 5 year old daughter. When asked about particular joys that she thought resulted from adopting, Jackie said:

They’re a gift. You know, I cannot imagine carrying a child and then placing it. Cannot imagine. I’m on a personal campaign to change the image, because our society has such a negative image of birth moms. Birth fathers don’t exist and birth moms are just, I tell people they’re courageous [for placing a child, because] it’s so easy to get an abortion today. To make that choice today when you don’t have to, I just think it’s a phenomenal gift.

While birth parents do have individual level agency to make choices, it is important to note how those choices are limited due in particular to poverty (Gailey, 2010). Focusing on placing a child as a “phenomenal gift,” takes the emphasis away from the realities or issues that influence if someone places a child or not, such as inadequate housing, lack of access to quality education, and job market instability. The fact that adoptive parents cannot imagine placing a child for adoption emphasizes that an altruistic sacrifice was made, while creating a distinction between those who place and those who adopt.

Bad Choices and the Pathology of Poverty

Respondents focused on birth mother choice to place a child for adoption as a positive choice or the “right” choice, but also on “bad” choices of birth mothers. Choices viewed as “bad” or negative included the perception that someone did not value education, was not motivated, or squandered opportunities. The focus on negative birth parent behavior is connected to cultural explanations of poverty. Placing a child was viewed as lacking values, drive, or ambition to adequately care for a child financially and/or emotionally. Jackie, introduced earlier, said:

It was a very different, when you adopt domestically, especially if you’re like my husband and I [who are] pretty much White [and] middle class. You are exposed to a completely different socio-economic class: people who live in subsidized housing, people who are on welfare, people who use abortion as birth control, people who visit food pantries, who are uneducated, [and] who make bad choices

Being poor, using government assistance, having an abortion, and not being educated, were viewed as “bad” choices that were lumped together as things related to low socio-economic status. Culture of poverty arguments were used by stressing a lack of values on the part of birth parents (i.e., making “bad” choices) with some respondents connecting those behaviors to genetic inheritance.

Lynn, introduced earlier, said that agencies do not prepare adoptive parents for challenges their child may experience. Lynn illustrates how some parents made assumptions about what genetic traits could/would be passed down from their child’s birth family. She said:

I think statistically that, I would say there’s almost like a selection bias. A woman who finds herself with an unplanned pregnancy –or finds herself with more than one unplanned pregnancy— who then recognizes at the point of unplanned pregnancy that she doesn’t have the wherewithal to take care of the child, that there’s nobody in the extended family that has the wherewithal to take care of this child already. [That] tells you something about that person. And so putting that in context, therefore most learning disabilities, most emotional disabilities are inherited. The child of those birth parents is going to their whole life, be in that situation as well. So, statistically, the probability of you having a child that has emotional difficulties, learning disabilities, just overall coping mechanism challenges is very high.

Unplanned pregnancies were linked to an inability to care for a child and that these issues related to poverty were also linked to genetic traits for emotional and behavioral problems. There was a connection between the idea of “bad choices” and the idea that traits associated with poverty were pathological in nature.

Another example that shows how adoptive parents used culture of poverty arguments in their portrayal of birth parents was from Amy, introduced earlier, who said:

Before Jenny came home, the agency called us and said there’s a birth sibling that’s about ready to be born. And I was torn for a while because you know, I thought what’s Jenny going to think when she finds out she has a sibling and we didn’t take him in too? But my girlfriend said something that helped me a lot because I was really feeling like I should [adopt the birth sibling] for Jenny. And the friend said, OK, she’s obviously not using birth control, how many of these children are you going to bring into your own home? So that was, that was the only temptation I had.

This example also shows how adoptive parents perceived their child’s birth mother as being irresponsible and making “bad” choices that lead to pregnancy. Parents in this sample often relied on ideas that stemmed from a culture of poverty framework, rather than considering individual circumstances or larger systemic factors that contribute to pregnancy (e.g., lack of access to birth control or norms regarding birth control usage) or ability to keep or care for a child (e.g., cultural norms regarding single motherhood or abortion).

Restrictions/Structure

When respondents recognized structural barriers that influenced why birth parents made the choice to place and why they were unable to parent their child, they typically focused on finances, laws and regulations. Lisa, the mother of four biological teenagers and one 11 year old daughter who was adopted from China as a toddler, said:

There’s enough families who are looking to adopt that there shouldn’t be any children that are homeless, you know. Because there’s just, I mean, they say there [are] a million children in China in orphanages. I’m like, a million is a lot of families but Chinese [people] would keep those kids if they didn’t have that policy that they have.

This example shows recognition of the role of finances and the economy in the number of children available for adoption. It also shows some recognition of laws and regulations that impact the ability of birth parents to choose to parent their child, such as the population control policy in China. Since the 1970s, China has used policies to push for one child per family with housing, health, and economic incentives for those who comply. Along with cultural preferences for male children, the one-child policy has led to large numbers of girl infants placed for adoption (see Dowling & Brown, 2009 and Greenhalgh, 2005 for discussion). It is important to note that wealth still shapes the choices available to parents in China since those with more monetary resources can pay fines and have larger families (Dowling & Brown, 2009). Thus, socio-economic status along with the population control policy effects if birth parents place a child for adoption or not.

Another example of recognizing structural limitations was from Amy, introduced earlier, who with her husband had a four year old daughter adopted from Guatemala as a toddler:

First of all, in Guatemala, you can’t list a dad on the birth certificate or culturally, legally, they’re not allowed to put the baby up for adoption because the husband, the man, is responsible for the upbringing of this child. [Our daughter was born] out of wedlock, but we have no idea— probably will have no idea— who the birth father was. We got several documents where the birth mother was a university [student], she was 21 and she was unable to support a child. [I] understand that she lived near Guatemala but it would take days to get down [from] Guatemala City. I think it’s a village that, you know, has no running water and those kinds of situations. . . . Poverty is what it sounds like.

The quote from Amy is an example of how adoptive parents in this study recognized factors that limit birth parent options. In this example Amy expresses her knowledge that lack of financial security was the main reason the birth mother placed her daughter for adoption.

Dina, introduced earlier, also conveys an understanding of the connection between poverty and adoption within the U.S. She said:

Well the adoption climate for whatever reason at that moment [that we were trying to adopt] was, there were not as many birth mothers placing. Now that [has] all changed. Our daughter was right on the cusp of the financial downturn. She actually came right after that, and the adoption climate changed after that, once again there were a lot more [children who were being placed].

Dina acknowledges the connection between economic opportunities, poverty, and the number of children available for adoption. While some parents in the sample noted structural factors of poverty and laws, some of the same respondents also relied on culture of poverty arguments by placing the onus of poverty on birth parents rather than larger systemic circumstances. This shows the complexity of adoptive parent views of birth parents and the pervasiveness of culture of poverty arguments.

Discussion & Conclusion

Data from fifteen in-depth interviews with white adoptive parent shows how they used multiple perspectives to discuss birth parents. Although some parents noted the link between socioeconomic status, global poverty, and laws and regulations that influenced birth mother choices to place, Quiroz (2007b) argues that there is still an assumption that their children are better off having been adopted than remaining with their birth family. This study found that adoptive parents recognized some structural boundaries that led birth parents to place, yet relied on culture of poverty arguments that blamed parents for making “bad” choices.

Adoptive parents portrayed birth parent relinquishment or placing of children as a choice. The focus on birth parent choice puts the onus on individual birth parents for their circumstances without taking into account larger structural factors that shape that decision (such as lack of financial stability due to lack of access to quality jobs) or cultural norms that limit birth control options or the ability of single women to raise children. Rothman (2005) argues that the focus on birth parent choice neglects the fact that everyone involved, except the adopter, does not have a lot of options to choose from. “Birth mothers need to place their babies; babies need families. Infertile women/couples may be said to “need” children, but it is a lot closer to a choice, a choosing, for them. It is when need meets choice that adoption can happen: the needs of the birth mother and the needs of the baby lead them to accept the choice of adopters” (Rothman, 2005: 58).

Implications

The focus on birth parent choice is problematic because it encourages culture of poverty perspectives, which may restrict the ability of adoptive parents to recognize important structural factors. As indicated by the findings of this paper, the focus on choice may stem in part from how agencies portray birth parents. Quiroz (2007a) provides some insight into the language used on agency websites, but additional research is needed to understand how agencies influence the ways in which adoptive parents view the process, their options, and birth families. Adoptive agencies should consciously evaluate how they portray birth parents since their portrayal may influence adoptive parent perspectives and ultimately the well-being of adoptive children who are the recipients of the stories their adoptive parent tell about their birth families. Findings have implications for the language adoption agencies use to discuss birth parents and the training agencies provide to adoptive parents pre and post adoption and ultimately adoptee well-being. The views of adoptive parents are passed on to adoptees have implications for the type of contact with birth families, the narrative that adoptees develop about their birth parents, and adoptee identity (Grotevant, Dunbar, Kohler & Esau, 2000; Von Korff & Grotevant, 2011).

Limitations

This study was limited by a few factors. The first was that many of the respondents were recruited online, which may skew the data particularly in terms of socio-economic status. Recruitment partially through online multiracial communities may also skew data towards people who have greater awareness of racial issues. Second, this study is limited by sample size and variation restricting comparison of findings across different groups such as age, marital status, sexuality, and type of adoption used. Third, data stem from interviews with adoptive parents, thus the perspective of adoptees, birth families, and agency workers is not included.

Gailey’s (2010) focus on how adoptive families define and create kinship includes a brief discussion on the risks that adoptive parents think they are taking adopting different children. She finds that White working class parents in her sample were not concerned about any problems that might be innate or genetic. The focus in this sample on genetic traits may stem from the difference in class status since the sample for this study consists mainly of adopters with high levels of income and educational attainment. Future research should look at how adoptive parent views differ based on their own socio-economic status.

Conclusions

This research provides information on how adoptive parents perceive birth parents and the use of culture of poverty arguments. Findings can help adoption agencies evaluate and revise how they prepare adoptive parents, portray birth parents, and counsel adoptive families. This is particularly important for families with open adoptions to maintain good relationships with birth families as well as those without that connection since they must rely less on facts and more on adoptive parent narratives about birth parents.

Future research should compare adoptive parent perceptions across different groups such as marital status, sexuality, socio-economic status, adopter race, and type of adoption. Existing research also lacks information on the role of biological parents and the relationships between birth and adoptive families. Additional research is also needed to better understand how adoptive parent perspective affects adopted children.

References

Alon, S. and Tienda, M. (2007). Diversity, opportunity, and the shifting meritocracy in higher education, American Sociological Review, 72, 4: 487-511.

Attride-Stirling, J. (2001). Thematic networks: An analytic tool for qualitative research, Qualitative Research, 1, 385-405.

Baccara, M., Collard-Wexler, A., Felli, L. and Yariv, L. (2010). Gender and racial biases: Evidence from child adoption, CESIFO Working Paper No. 2921. http://www.ifo.de/portal/pls/portal/docs/1/1185776.PDF

Bartholet, E. (1991) Where do black children belong? The politics of race matching in adoption, University of Pennsylvania Law Review, 139, 1163-1256.

Berg, B.L. (2009). Qualitative Research Methods for the Social Sciences, 7th edition, Boston, Allyn & Bacon.

Bonilla-Silva, E. (2003). Racism without racists: Color-blind racism and the persistence of racial inequality in the United States. New York: Rowman B. Littlefield Publishers, Inc.

Briggs, L. and Marre, D. (2009). “Introduction: The circulation of children,” In Diana Marre & Laura Briggs (Eds.) International Adoption: Global Inequalities and the Circulation of Children (pp. 1-28), New York: New York University Press.

Bureau of Consular Affairs, & U.S. Department of State (2011). Intercountry adoption: FY 2011 annual report on intercountry adoption. Retrieved from: http://adoption.state.gov/about_us/statistics.php.

Dowling, M. and Brown, G. (2009). Globalization and international adoption from China, Child and Family Social Work, 14, 352-361.

Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute (2008). Finding families for African American children: The role of race & law in adoption from foster care, Evan B. Donaldson Adoption Institute, retrieved 1/17/2012 from http://www.adoptioninstitute.org/publications/MEPApaper20080527.pdf

Feigelman, W. and Silverman, A.R. (1997). “Single parent adoption.” In Chevy Chase (Ed.) The Handbook for Single Adoptive Parents, National Council for Single Adoptive Parents, 123-129.

Gailey, C.W. (2010). Blue ribbon babies: Race class and gender in U.S. adoption practice. Austin, TX: University of Texas Press.

Gallagher, C. (2003b). Color-blind privilege: The social and political functions of erasing the color line in post race America, Race, Gender & Class, 10, 1-17.

Greenhalgh, S. (2005). Missile science, population science: The origins of China’s one-child policy, The China Quarterly, 182, 253-276.

Grotevant, H.D., Dunbar, N. Kohler, J.K., Esau, A.M.L. (2000). Adoptive identity: How contexts within and beyond the family shape developmental pathways, Family Relations, 49, 379-387.

Iversen, R.R. & Armstrong, A.L. (2006). Jobs aren't enough: Toward a new economic mobility for low-income families. Philadelphia: Temple University Press.

Johnson, K. (2006). Chaobao: The plight of Chinese adoptive parents in the era of the one-child policy, In Toby Volkman (Ed.) Cultures of transnational adoption 2nd edition (pp. 117-141), Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

LaRossa, R. (2005). Grounded theory methods and qualitative family research, Journal of Marriage and Family, 67, 837-857.

Leech, N. L., & Onwuegbuzie, A. J. (2007). An array of qualitative analysis tools: A call for data analysis triangulation. School Psychology Quarterly, 22, 557–584.

Lewis, O. (1959). Five families: Mexican cases studies in the culture of poverty. New York: Basic Books.

Maldonado, S. (2006) Discouraging racial preferences in adoptions, UC Davis Law Review, 39, 1415 – 1480.

Maxwell, J.A. (1996). Qualitative research design: An interactive approach, Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage Publications.

McDonald, S.J. (2001). How Whites explain Black and Hispanic inequality, The Public Opinion Quarterly, 65, 562-573.

Miall, C.E., and March, K. (2005). Community attitudes toward birth fathers' motives for adoption placement and single parenting, Family Relations, 54, 535-546.

Moynihan, D.P. (1969). On understanding poverty: Perspectives from the social sciences. New York: Basic Books.

Quiroz, P.A. (2007a). Adoption in a color-blind society, Latham, MA: Rowan and Littlefield.

Quiroz, P. A. (2007b). Color-blind individualism, intercountry adoption and public policy. Journal of Sociology and Social Welfare, 34, 57-68.

Rothman, B. K. (2005). Weaving a family: Untangling race and adoption. Boston, MA: Beacon Press Books.

Ryan, G.W., and Bernard, H.R. (2003). Techniques to identify themes, Field Methods, 15, 85-109.

Shaw, G.M. and Shapiro, R.Y. (2002), Trends: Poverty and public assistance, The Public Opinion Quarterly, 66, 105-128.

Selman, P. (2009). The rise and fall of intercountry adoption in the 21st century. International Social Work, 52, 575-594.

Stolley, K.S. (1993). Statistics on adoption in the United States, The Future of Children: Adoption, 3, 26-42.

Volkman, T.A. (2006). Embodying Chinese culture: Transnational adoption in North America, In Toby Volkman (Ed.) Cultures of transnational adoption 2nd edition (pp. 81-116), Durham, NC: Duke University Press.

Von Korff, L. and Grotevant, H.D. (2011). Contact in adoption and adoptive identity formation: The mediating role of family conversation, Journal of Family Psychology, 26, 393-401

Notes

Note that adoption in this study does not include family adoptions rather it refers to adoption of children through foster care, public and private domestic adoption, and international adoption.

This couple defined themselves as married and they were legally married in Canada. However, their marriage was not legally recognized by the state of Illinois or the United States government at the time of this interview.

This study was approved by Purdue University’s IRB prior to recruitment.