The University of Michigan School of Dentistry - Victors for Dentistry (1962–2017): Decades of Innovation and Discovery

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chapter 5. The Machen Years (1989–1995)

About nine months before J. Bernard Machen arrived at the School of Dentistry to begin his term as dean, Dr. John Drach said he was asked by Interim Provost Robert Holbrook to chair the Search Committee and recommend three candidates to the provost. The committee, Drach said, was looking for several attributes in a new dean—a dentist with academic credentials beyond the DDS plus organizational, managerial, and financial experience. From a list of over 50 candidates, the Search Committee ultimately recommended three names, including Machen’s, to the new provost, Charles Vest, and James Duderstadt, who was now president of the University of Michigan.

Machen started his tenure as dean on October 1, 1989. “It was no secret that the School of Dentistry was going through some very difficult times when I came to Michigan in 1989. Alumni and others knew it. The school was downsizing, there were budget issues and other concerns,” Machen said reflecting on the realities of the academic climate in the late 1980s.

Maintaining the Momentum

As he started his deanship, Machen said it was “absolutely essential we continue the activities started during the past two years.”[1] In addition to the many initiatives advanced by the school during the transition period, he spoke of the necessity of continually improving the school’s educational and clinical programs. He stressed the need to develop new interdisciplinary research activities that cut across departmental and school boundaries as well as the importance of developing graduate education programs that contributed to the needs of society in the twenty-first century.

In his first address to faculty on October 23, 1989, Machen referred to the goals and principles that were identified by the Transition Committee in 1987. But he went a step further saying,

I am formally endorsing this thoughtfully drawn list of goals and taking it as my own. . . . By endorsing these goals, I hope to make it clear that I want to continue in the direction that has been identified during the transition process.”[2]

To sustain the momentum established by the Transition Committee, Machen also announced that he was appointing Kotowicz as senior associate dean. “In my mind, this is the most important appointment I will make at the school,” he said, adding Kotowicz “will be an integral part of the administrative team. This appointment has enthusiastic support from within the dental school and from the general university.”[3]

New Organizational Structure

After some tweaking, the new department structure was finally set in place on July 1, 1990, when the school’s Executive Committee voted to approve the major realignment of the school’s six departments.

During this time, the Office of Patient Services was created to support the delivery of quality dental care and ensure that clinic operations ran smoothly and efficiently. Dennis Turner, who directed the preclinical dentistry program was named director of the new office in 1991 and a year later was named assistant dean for patient services. In these capacities he implemented the integrated preclinical science program, the patient/student monitoring system, and the new D-3 clinical program. He also directed the implementation of the vertical integrated clinical program in the predoctoral education program and was instrumental in the redesign and implementation of a new central sterilization system and a centralized record program.[4]

A Patient Records office was also established to track each patient’s dental record and to efficiently process the services completed at each appointment. Managing patient records in this way introduced a new level of accountability, linking each record to a specific provider thus significantly reducing the likelihood of a “kept, lost or missing” chart.[5]

Administrative restructuring also included the formation of a new unit in 1990, the Office of Alumni Relations and Continuing Dental Education. The new unit combined the areas of continuing education, an initiative that began in 1933 [6] with alumni relations, development, and publications. Dr. Arnold Morawa was named the assistant dean of the new office and was tasked with coordinating the activities of the unit with the goal to enhance connections and communications with the school’s alumni.[7]

Phasing in the New Curriculum

An emphasis on comprehensive care changed the focus of clinical care provided by dental students. Service to the patient became the priority, so that a patient was no longer viewed as a means to fulfilling a set of requirements for graduation, but as an individual whose specific dental needs would be addressed through a comprehensive treatment plan.

In 1990, a pilot program was initiated in one of the D4 clinics that offered fourth-year dental students the opportunity to apply comprehensive care practices to patients they were treating. The program was a success and the following year, the pilot program was expanded to include all three clinics where fourth-year dental students provided care.[8]

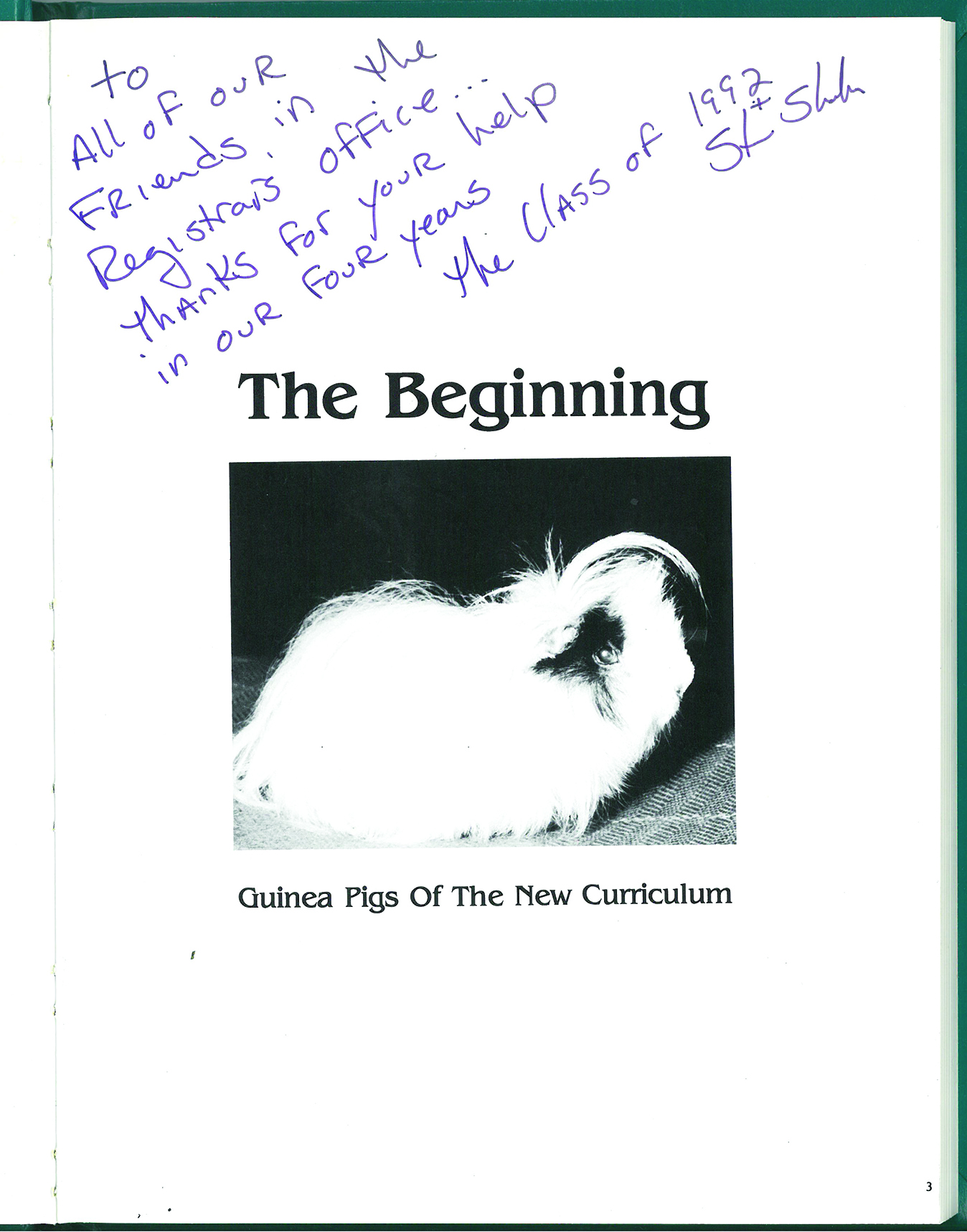

This page from the 1992 dental school yearbook captures the sentiment of the students who were introduced to the new curriculum.

In each of the three clinics, a generalist/master clinician was named clinic director to oversee the team approach to diagnosis, treatment planning, patient care, and maintenance. The clinic directors were assisted by specialists in prosthodontics, endodontics, and periodontics on a continual basis with oral surgeons, orthodontists, and oral pathologists available as needed. This interface among the generalist, specialist, and student created a supportive environment conducive to cooperation, planning, and education.

One of the major goals of the third-year curriculum was to increase the D3s clinic time in preparation for comprehensive care in the D4 year. By increasing the length of the school year and by eliminating the duplication of didactic material, an additional 122 hours of clinical experience were incorporated into the D3 year.

To manage this increase in clinical services, a computerized system was developed to track patients from recall and preventive services through planned restorative services. The system was designed to maintain a patient pool for the school and assure continuous comprehensive care service for patients.

Building a Strong Faculty

With the new department structure in place, Machen named the chairs who would lead those departments. John Drach was named chair of the Department of Biologic and Materials Sciences. He was interim chair of the Department of Oral Biology since 1985 before it became a part of the Department of Biologic and Materials Sciences. Joseph Dennison was named chair of the Department of Cariology and General Dentistry, and Brien Lang was name chair of the Department of Prosthodontics.

Following extensive national searches, three other department chairs were named. Lysle E. Johnston, Jr., was selected to head the Department of Orthodontics and Pediatric Dentistry. He was also appointed the Robert W. Browne endowed professor, named for the Grand Rapids orthodontist who established one of the school’s first faculty endowments in 1985. His appointment as department chair and director of the Graduate Orthodontics Program in 1991 was tantamount to a homecoming since he earned his dental degree and master’s degree in orthodontics from the U-M in 1961 and 1964, respectively.[9] He was a renowned expert in the differential effects of various orthodontic treatments and mechanisms of facial growth and the nature of interactions between growth and treatment. He taught more than 300 orthodontic specialists during his career, lectured worldwide, and received some of the most prestigious awards in orthodontics before he retired in May 2005.[10]

Martha Somerman came to the School of Dentistry as chair of the Department of Periodontics, Prevention and Geriatrics. She was the first woman to chair one of the school’s academic departments. Internationally recognized for her work with mineralized tissue proteins, her research on tissue regeneration and repair would become the basis for innovative research and possible new clinical therapies involving bone implants and tissue repair.[11] She was also the first to hold a professorship, endowed in 1985, by one of the school’s alumni, Dr. William K. Najjar (DDS 1955) and his wife, Mary Anne.

On September 1, 1990, Dr. Stephen Feinberg began his tenure as chair of the Department of Oral Medicine, Pathology and Surgery. He came to U-M from the Ohio State University College of Dentistry, where he had taught since 1983. In making the appointment, Machen noted the high praise Feinberg received as an effective teacher. Feinberg’s basic laboratory research focused on tissue regeneration and his clinical work examined temporomandibular joint surgery.

New Technology Advances Dental Education

New technology, which included desktop computers, modems, and use of the Internet, were now being used with increasing frequency in education and patient care.

In 1991, Joseph Dennison, chair of the Department of Restorative Dentistry, and Machen discussed creating a one-year program for recently graduated dentists who planned to practice comprehensive general dentistry and who also wanted to expand their skills in areas of personal interest. An Advanced Education in General Dentistry (AEGD) program was established following those discussions. The program offered didactic instruction and clinical experiences in all specialty disciplines in dentistry. AEGD emphasized esthetic dentistry and use of esthetic dental materials and techniques, practice management, and geriatric dentistry and included internal rotations in oral surgery and pediatric dentistry.[12]

Drs. Joseph Dennison and Peter Yaman demonstrate the Veravision UltraCam II Intraoral Camera System.

Using technology to help patients was also the focus of a course in advanced esthetic dentistry techniques for fourth-year dental students. Developed by Restorative Dentistry faculty members Dennis Fasbinder and Donald Heys, the course provided didactic and laboratory instruction on the use of computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technology that students were then able to incorporate in treatment plans for appropriate cases in clinic.[13]

Dr. Dennis Fasbinder uses computer-aided design and computer-aided manufacturing (CAD/CAM) technology to describe treatment options to a patient.

Helping launch the AEGD program on July 1, 1992 was its new director Dennis Fasbinder, who was beginning his teaching career at the School of Dentistry.[14]

Three U-M dental graduates enrolled. Technology was an important part of the AEGD curriculum. “I was fortunate to get in on the ground floor of the technology initiative here and the launch of AEGD,” Fasbinder said. As technology continued to evolve during the 1990s, CAD/CAM became accepted and incorporated into the AEGD curriculum.

“AEGD gave recent dental graduates new insights into ways they could provide better oral health care to their patients using emerging CAD/CAM technology,” he said. The CEREC (Chairside Economical Restoration of Esthetic Ceramics, or CEramic REConstruction) system by Sirona enabled dentists to fabricate and insert ceramic restorations into a patient’s mouth at chairside during a single visit instead of requiring multiple visits.

Fasbinder was director of the AEGD program until 2013, when it was replaced by a new program, Computerized Dentistry. Computerized dental systems are an integral part of contemporary dental practice. The new program was designed to provide students a focused opportunity to apply dental technology as part of comprehensive patient care.

In 1993, an official from Nobel Biocare’s headquarters in Sweden visited the school to discuss a new high-tech approach to make titanium all-ceramic crowns—the Procera® System. Company representatives were interested in collaborating with the school to investigate clinical questions related to dental implants and all ceramic crowns—questions critical to patient care. The collaboration, led by Brien Lang, chair of the Department of Prosthodontics, resulted in a $625,000 gift from Nobel Biocare and the establishment of a Center for Excellence.

Over the next five years, the center conducted more than 50 research projects and became the research hub for answering laboratory questions and conducting clinical evaluations on implants and restorative devices. The technology involved was innovative and according to Lang had “the potential to revolutionize dentistry.” The center set a benchmark for excellence in teaching, research, product evaluation, and patient care.

National Conference on Workforce Diversity

Diversity was always emphasized as essential to the school, the university and the oral health profession. In June 1991, more than 170 health professionals from around the nation gathered at the University of Michigan for a conference, Black Dentistry in the 21st Century. Hosted by the School of Dentistry, and co-chaired by Drs. Michael Razzoog and Emerson Robinson, the meeting featured discussions about dental care in the Black community, the state of dental practice in the Black community, health behavior and research.

Conference participants voiced concern about a shortage of minorities in the health profession. One of them, guest speaker Dr. Audrey Manley, deputy assistant secretary for health in the Department of Health and Human Services, noted that Blacks accounted for 12% of the U.S. population, but only 4% of the nation’s dentists and 5% of the nation’s physicians. “Minority America is sorely in need of practicing dentists, physicians, researchers, academicians and scientists who are sensitive to cultural and ethnic distinctions, and who can serve as mentors and role models for our youth,” she said.[16]

Recommendations that emerged from the conference included:

- Recruitment initiatives to familiarize students about dentistry in the high schools and through counselors, dental school faculty, dental practitioners and professional organizations.

- Extend outreach programs into high schools and colleges to encourage early exposure to involvement in research.

- Remove barriers to preventive practice by insisting on inclusion of preventive procedures in all health plans that provide dental benefits.

- Establish a level of responsibility within the African-American community to oversee funding and research efforts.

- Create a data bank of African-Americans interested in faculty and administrative positions and a network to monitor institutional commitment. [16]

Proceedings from the conference were later published in a book, Black Dentistry in the 21st Century, co-edited by Drs. Razzoog and Robinson.

Machen Reappointed

In September 1993, Machen was reappointed as dean through 1999. Without a doubt, significant progress on all School of Dentistry fronts had been made. Speaking to the faculty and staff on September 23, 1993, Machen thanked everyone for their hard work. He said the school’s financial outlook had improved, research support continued to grow, the number of applications for admission to both the dental and dental hygiene programs was growing, and master’s programs and residencies had strong applicant pools. “I can state with confidence that today the University of Michigan School of Dentistry is among the leaders and best,” he said.[17]

“The direction of our school is now under our (his emphasis) control,” he said. “To be successful in the twenty-first century, it will be necessary to continue to make significant changes.” His priorities moving forward included developing a new program to educate dentists in the clinical specialty education programs, creating a high-quality PhD education program in the oral health sciences (OHS), and taking a new look at the academic dental hygiene program. “These four programs – dental, master’s, PhD and dental hygiene – are the academic core of our institution,” he said.[17]

Research in the 1990s

Collaboration was the operative word in research during the 1990s. In his October 1989 address to faculty, Machen said developing new interdisciplinary research activities that cut across departmental and school boundaries was among his highest priorities.

An OHS/PhD program began taking shape in the early 1990s. The school’s sole PhD program was in oral biology. Machen asked Dr. Charlotte Mistretta to launch a school-wide doctoral program, drawing on the talents of faculty members from all six departments.[18] The expanded OHS/PhD program, directed by Mistretta, was officially established in 1994.[19] The OHS/PhD program was needed because, as then senior associate dean, William Kotowicz said,

. . . dental education and dental research needed well-educated PhD-level researchers. Since the PhD is the ultimate academic degree, we knew that if we wanted to remain competitive and continue attracting both the best faculty and the best students, we would have to have a school-wide program and build it, literally, from the ground up.[20]

The Campaign for Michigan

Under the umbrella of the University’s billion dollar Campaign for Michigan, publicly launched in 1992, the School set a goal to raise $10 million for student support, faculty support and facility renovation projects. Because alumni and friends were so generous and the early response to the school’s effort was so positive, the initial $10 million goal was increased to $13 million. The grand total at the end of the campaign was nearly $29 million, boosted by a $10 million dollar gift commitment from Dr. Roy Roberts (DDS 1932) and his wife, Natalie. At the time, the gift from the Roberts was believed to be the largest single commitment ever made to a dental school.[21]

The Sindecuse Museum

In 1990, Dr. Gordon Sindecuse (DDS 1921) suggested to Dean Machen that the school create a dental museum that would collect, preserve, and exhibit memorabilia showcasing dentistry’s growth and evolution. To make that happen, Sindecuse gifted $1 million to establish what would become the Gordon H. Sindecuse Museum of Dentistry.[22] The museum officially opened on September 18, 1992, under the direction of curator Jane Becker.[23]

Becker’s first tasks were to acquire a basic collection, create storage for the artifacts, and coordinate the installation of exhibits. The initial exhibits were crafted from the collections of three dentist collectors. Charles C. Kelsey (DDS 1964), a prime keeper of the school’s history, had assembled a chronological exhibit of dental articulators. Ronald D. Berris (DDS 1974) lent items from his personal collection including a “Swan” dental chair (ca. 1870), an X-ray unit (ca. 1930), early Ritter electrical dental unit (ca. 1920), and an array of dentifrice containers with advertising images underglazed on the porcelain lids. Ohio dentist Jack Gottschalk, knowing that items would be well cared for and kept together, allowed the museum to purchase artifacts from his private collection. The first exhibits recreated two operatories from two distinct historical periods—an operatory setup from the late nineteenth century before electricity was common and an early electric operatory when electricity was used primarily for lighting and running water.

Sindecuse’s gift made it possible to purchase collections, renovate the W.K. Kellogg lobbies, and establish an endowment to ensure perpetual support.[23] His gift to establish the museum, however, would not be his last. By 1995, outright gifts from Sindecuse, coupled with his estate gift to the school, exceeded $4 million.[24]

Another Endowed Professorship

A new endowed professorship was established in April 1995. World-renowned orthodontics researcher and clinician Dr. Thomas Graber formalized a $1.2-million commitment to the School of Dentistry to fund the Thomas M. Graber Professorship in Orthodontics.[25]

Graber, an orthodontist and anatomist, had a major impact on the treatment of craniofacial anomalies in dentistry and medicine. He had served as a visiting faculty member in the Department of Orthodontics since 1958 and said, when making this gift, that “despite the fact that I’m affiliated with the University of Illinois, I consider Michigan’s Department of Orthodontics to be the best in the country.” Dr. James McNamara was appointed as the first Thomas M. and Doris Graber Endowed Professor.

Machen Appointed Provost

After successfully leading the school through major changes and two years into Machen’s second five-year term as dean, U-M President James Duderstadt asked Machen to serve as the university’s interim provost and executive vice president for Academic Affairs. On June 20, 1995, Machen announced that he would move from the School of Dentistry to the Fleming Building to become interim provost.

I want to emphasize that this is a temporary position. I am not a candidate for Provost, and I expect to resume my deanship of the School of Dentistry as soon as a replacement has been named. . . . Senior Associate Dean Bill Kotowicz, an immensely competent administrator, will be serving as acting dean in my absence – as he did before my appointment.[26]

Machen served as interim provost for a year, then, with the resignation of U-M President James Duderstadt, the Board of Regents asked Machen to extend his term for two years (1996 and 1997) and assume the role Provost and Vice President for Academic Affairs. Machen agreed to take on the provost’s responsibilities under one condition: that he be allowed to name his successor at the dental school. William Kotowicz, who was senior associate dean at the time, then was named interim dean in the fall of 1995.

Reflections

The transition and subsequent department reorganization along with the implementation of the new curriculum were among the hallmarks of the Machen years. Drs. Jed Jacobson and Lisa Tedesco offered poignant insight into Machen’s tenure as dean,

Dr. Jed Jacobson said:

Looking back at that period of time, I believe Bill Kotowicz and the work of the Transition Committee he led played a major role in the success Bernie had as dean at the School of Dentistry. . . . The transition or reorganization of the dental school worked. The school went from being a very independent unit on campus to one that was woven into the fabric of the university. The University of Michigan brand with prospective dental students became a powerful one. As a result of the school’s achievements since then, we have been one of the pre-eminent dental schools in the world. (Personal communication, July 23, 2015)

Dr. Lisa Tedesco, who joined the School of Dentistry in July 1992 as associate dean for Academic Affairs and as a professor in the Department of Periodontics, Prevention and Geriatrics, lauded Machen’s and Kotowicz’s leadership:

Both played major roles in making change materialize at the school. They were change agents and what they did was absolutely essential. Bernie and Bill understood higher education and its valuable role in society. They understood Michigan’s responsibilities, the resources that were needed to create and maintain faculty support, and the importance of diversity in society. (Personal communication, June 8, 2015)

Machen left the U-M to become the president of the University of Utah from 1998 until 2004, when he was named president of the University of Florida—a position he held through December 2014.