The University of Michigan School of Dentistry - Victors for Dentistry (1962–2017): Decades of Innovation and Discovery

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chapter 3. The Christiansen Years (1982–1987)

Arriving from the National Institute of Dental Research (NIDR, the predecessor of the National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research) in Bethesda, Maryland, where he was associate director for Extramural Programs, Dr. Richard Christiansen began his term as dean and director of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation Institute of Graduate and Postgraduate Dental Education on July 1, 1982. After his appointment was approved by University of Michigan (U-M) Regents at their June 18–19, 1980, meeting, U-M Vice President for Academic Affairs B.E. Frye said, “Dr. Christiansen has had a distinguished career in dental administration and research. His experience and abilities will serve our distinguished School of Dentistry well.”[1]

Budget Cuts Hit Hard

Christiansen faced financial challenges from the moment he arrived. “I knew about them when I accepted the dean’s position in 1981,” he said. “I spent a lot of time conferring with Bob Doerr about finances and other matters.”

In the 1981–1982 annual report from the school to the university, Christiansen noted: As with other units in the University, budget and financial matters occupied much administrative time, due to deteriorating economic conditions in the state. The school significantly reduced its 1981–1982 budget by $510,000 following a university mandate to make a 6-percent reduction. Vacant and unfilled positions were a carefully reviewed and not filling those positions contributed significantly to help balance the budget. No faculty positions were lost; however, the $510,000 reduction in spending was especially painful because many staff positions were cut. University statistics showed the school with 122 faculty members: 51 professors, 29 associate professors, and 42 assistant professors.[2]

Managing the Budget Crisis

Christiansen appointed the school’s Executive Committee to serve as a new Budget Priorities Committee to address budget shortfalls and make recommendations as to how to reduce school expenditures.[3] In a July 2, 1984, memo, Christiansen and Budget Priorities Committee Chairman Dr. Fred Burgett noted, “The crisis of the general fund shortfall exists and has to be dealt with. The fear of the Committee is that if the school does not contend with the deficit, the University administration will.” He added that savings would include a headcount reduction of 16 percent of faculty and 23 percent in support staff. A July 19, 1984, follow-up memo noted: “The planned reduction is a viable one, the implementation of which will not detract from the educational, research and service missions of the school.”[4]

For the 1983–1984 academic year, the school projected a general fund salary deficit in excess of $500,000, including fringe benefits. The following academic year was even worse with a General Fund deficit of $730,000. As a result, approximately 20 support positions were removed from the budget. Full-time equivalent (FTE) positions fell from 176.65 in September 1982 to 149.90 in 1984, a decrease of 15 percent.[3][5]

The number of FTE positions also continued to decline. By the fall of 1986, the school reported its FTE count for faculty was 134 and 143 for staff. The FTE reductions were more than 14 percent for faculty and more than 15 percent for staff.[6][7]

Decreasing Class Size

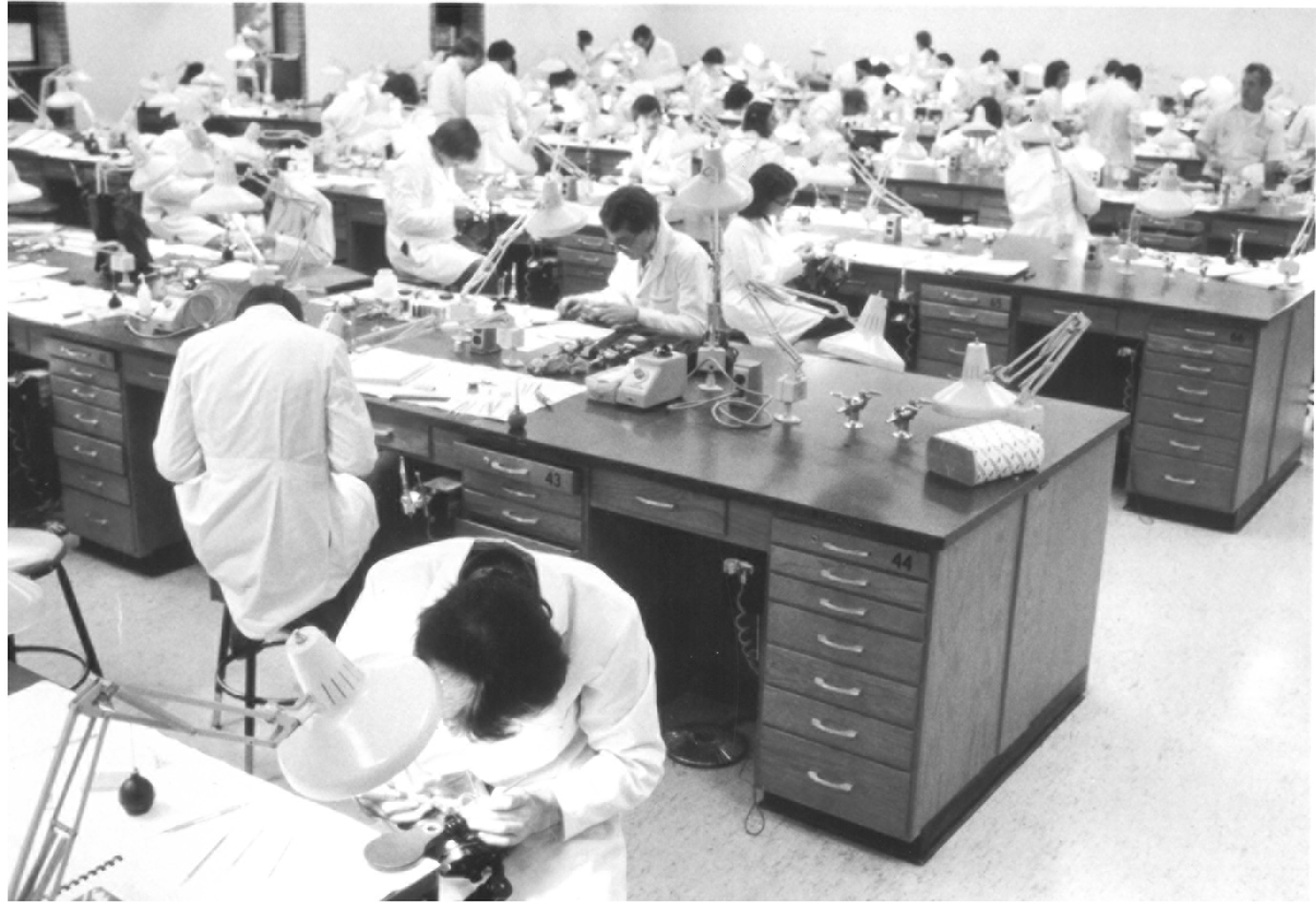

Given the bleak budget picture, school administrators knew that it was imperative to reduce class size. For fall term 1982, 135 first-year dental students were admitted, a decline of 10 percent from the previous year. Future reductions were expected and by the start of the 1987 academic year, first-year dental student enrollment had declined by a third, from a peak of 151 students to 90 students.[8]

First year DDS students working in the preclinical lab. The entering class size was 96 students in 1986.

| Year | Applicants | Accepted | Enrolled | GPA | W (%) | Minority (%) | Out-State (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1981 | 873 | 173 | 150 | 3.39 | 28 | 11 | 3 |

| 1982 | 755 | 178 | 135 | 3.33 | 29 | 9 | 4 |

| 1983 | 666 | 183 | 125 | 3.29 | 26 | 14 | 6 |

| 1984 | 594 | 175 | 121 | 3.24 | 33 | 16 | 8 |

| 1985 | 503 | 175 | 121 | 3.26 | 36 | 15 | 15 |

| 1986 | 496 | 198 | 96 | 3.08 | 31 | 22 | 11 |

| 1987 | 566 | 201 | 90 | 3.11 | 39 | 28 | 16 |

Engaging the Alumni

To help meet some of the budget shortfall, Christiansen also sought to establish endowed professorships that would also help the school recruit and retain highly qualified faculty. “There were clear signals that we wouldn’t be able to rely on the same levels of state or federal funding in the future as we had in the past,” he said.[9]

“I saw a need to get our alumni involved. I wanted the alums to be aware of the financial issues the school was facing and to enlist their help in supporting the school’s programs,” Christiansen said. “Dick Desmond in our Development and Alumni Relations Office worked closely with me to achieve those two important objectives.” He underscored that that approach “was a good way to engage the alumni as we planned for the future and the related financial uncertainties.”

Browne and Najjar Endowments

In 1985, the school announced two major gifts from grateful alumni. Dr. Robert Browne (DDS 1952, MS 1959), a Grand Rapids orthodontist and chairman of the board and chief executive officer of Care Corporation, pledged $1 million to create an endowed professorship in dentistry. In making this gift, Browne noted:

My contributions are a way of repaying the university for the opportunity it provided me. Alumni should want to see the high quality of the school maintained and even enhanced. . . . We all have a personal responsibility to help make that happen.”[10]

Dr. Lyle Johnston was named the first Robert W. Browne Professor of Dentistry. Over the years, the Browne endowment grew to an amount that would support the establishment of a second professorship. In 2002, the Robert W. Browne Professorship in Orthodontics was established. Dr. Sunil Kapila was the first faculty member to hold this professorship. See Appendix B for a complete list of the School of Dentistry endowed professors.

The school’s second $1 million pledge was also designated to create an endowed professorship named for its donors, Dr. William K. and Mrs. Mary Anne Najjar.[10] After earning his dental degree from U-M in 1955, Dr. Najjar practiced dentistry in Grand Rapids for 14 years and started a dental materials company, Janar Corporation, which he later sold to Johnson & Johnson. Najjar said his reason for making this gift was based on his belief “in the future of the dental profession” and a desire to “reinvest some of my lifetime earnings in dentistry as a measure of my appreciation for the important part the University of Michigan played in my life.” Dr. Martha Somerman was named the first William K. and Mary Anne Najjar Professor of Dentistry. As with the Browne endowment, the Najjar endowment also grew and was able to support a second professorship. In 2002, the William K. and Mary Anne Najjar Professorship in Periodontics was established and Dr. Laurie McCauley was the first faculty member named to this professorship.

Dental Hygiene Programs Advance

Fall semester 1984, marked a milestone for dental hygiene education at Michigan with the launch of two new programs. A new baccalaureate degree program was introduced that included a one-year program of prescribed liberal arts courses followed by three years of didactic and clinical studies that included oral anatomy, radiography, dental pharmacology, pain control, nutrition, and other subjects. The change meant that all dental hygiene students enrolled in the College of Literature, Science and the Arts for their first year of study and completed years two through four at the School of Dentistry. A significant change was that students would no longer be accepted into the dental hygiene program directly from high school. Since this program was launched, all U-M dental hygiene students have graduated with a Bachelor of Science degree.[11]

1984 dental hygiene faculty: (L–R) Jennifer Turnbull, Wendy Kerschbaum, Debra Zahn-Simmons, Sally Holden, Tamara Bloch, Bridget Clancy, Susan Pritzel, and Susan Johnstal. From 1984 School of Dentistry Student Yearbook.

The second program, a post-certificate program, was designed to provide dental hygienists who had graduated with an associate degree or certificate an opportunity to complete requirements toward a Bachelor of Science in dental hygiene. This program was offered for registered dental hygienists who either graduated from U-M or another accredited dental hygiene program.[5]

Clinic Hours Expand, Clinic Managers Hired

Historically, departments staffed clinics in half-day sessions, with clinic instructors available either in the morning or afternoon. This arrangement posed a great challenge to students trying to provide comprehensive care or complete oral health care to patients coming to the school’s clinics for treatment. A significant change to the clinical program began in May 1986 when the school’s clinical departments established all-day clinics. This meant that students could consult with faculty instructors in specific disciplines in every clinic session.

In the summer of 1985, four clinical managers were hired to supervise and instruct fourth-year dental students. The clinic manager’s job was to help students learn practice management skills and manage their patient’s treatment more effectively. The managers also assisted in assigning patients to students. Since this program was well received by students, faculty, and patients, Christiansen expressed a desire to add more managers for dental students in the second and third years of their education.[6][7]

Hospital Dentistry and Oral Surgery Move

Another important change in clinical care came on February 14, 1986, when the Department of Hospital Dentistry and the Department of Oral and Maxillofacial Surgery moved from facilities in the old University Hospital to the new U-M Hospital. The new space offered 10 examination/treatment rooms, 2 equipped for ambulatory oral surgery, and a fully equipped recovery room. With new administrative, patient care, and patient waiting areas, the space was two-and-a-half times larger than that in the old outpatient building.[12][13]

The Dental Research Institute

Christiansen had a keen sense of the research environment in dentistry. Having served as associate director for extramural programs at NIDR and director of the organization’s craniofacial anomalies program before coming to Michigan, he was aware of trends taking place nationally. He had a good idea of how these trends might affect dental education.

One important trend involved a decline in oral disease, primarily dental caries. That trend suggested the way oral care was provided to patients would have to change. Christiansen emphasized that dentists in the future would need to become more broadly educated in all facets of oral health in order to provide optimal care. “Future practitioners,” he said, “must have an education that emphasizes a thorough understanding of scientific principles, human biology and basic biologic sciences in addition to the rigorous clinical disciplines.”[14]

After his years at the National Institutes of Health (NIH), Christiansen also recognized the importance of the NIH-funded Dental Research Institute (DRI) on the U-M campus. He was well versed in how DRIs functioned at U-M and four other locations around the country.

“One of my goals was to foster and promote the advancement of the most promising areas of dental/oral-facial research, which was vital for leadership in the profession of dentistry,” he said. During the 1984–1985 academic year, it seemed that funding the DRIs was in jeopardy as Congress began to consider budget reductions for these institutes. Christiansen testified before the House Budget Committee to defend the NIH-funded DRIs. He spoke about their importance to oral health care nationwide. The funding cuts did not occur.

The Michigan Growth Study

Also in 1986, Dr. James McNamara, who began teaching in the Department of Orthodontics during 1983–1984 academic year, was asked by Dr. Fred More, associate dean of the School of Dentistry, to assume a new role as curator of the university’s Elementary and Secondary School Growth Study.

The Michigan Growth Study, as it was later known, began in 1935 in the University School, a laboratory within the School of Education. Over time, the study became world famous with data collected and used in hundreds of research studies. Launched by Dr. Willard Olsen, dean of the School of Education, dental records, radiographs (X-rays), and dental casts of young children and teenagers were updated annually from 1935 to 1970. The data gave oral health-care professionals a wealth of information about how and to what degree the growth and development of a child’s craniofacial structure occurred. Information also included medical, physiological, and anthropologic data. Only 9 or 10 schools in North America collected such longitudinal data.

The collection was brought to the School of Dentistry in 1952 when Dr. Robert Moyers became chair of the Department of Orthodontics. “The information is a valuable resource and continues to be used in clinical studies to this day because it serves as a benchmark or reference point to help us know how children without treatment grow and develop,” said McNamara. Moyers also was the founding director of another initiative that McNamara became extensively involved with, the Center for Human Growth and Development. Established by U-M Regents in 1964, the center recruited senior scholars (fellows) from many disciplines who developed interdisciplinary and collaborative research programs integrating craniofacial biology, developmental psychology, developmental biology, nutrition and public health, morphometrics, anthropology, and pediatrics.[15]

Technology and Learning

The school’s 1986–1987 annual report to the university noted the academic year had been an exceptionally busy period for the television unit. The basic activities of the videotape production team, which included a total of 92 productions that year, along with videotape duplication, audio/visual services, and maintenance, continued to absorb a major portion of the staff’s time. The school underscored its commitment to the growth of computers in the academic environment. A completely renovated computer center, CAIDENT (Computer-Aided Instruction DENTistry), opened on October 17, 1986, included 34 Macintosh computers, 13 dot matrix printers, a laser printer, and a generous assortment of software. The school recognized that the computer would continue to play an important role in student learning and the production of educational materials.[7]

Nurturing International Collaborations

The School of Dentistry was recognized as a leader in dental education and research around the world. The school’s faculty understood the value of international collaborations and began to work on several international exchanges with dental schools and dental organizations.

When he was at NIDR, Christiansen traveled to Jerusalem in 1979 to help the Hadassah School of Dental Medicine celebrate its 25th anniversary. That experience had an impact on him that remained with him during his years as dean. “I thought that if we could get professionals from around the world together to discuss oral health needs on a global scale it might lead to tackling issues and solving problems more efficiently and effectively,” he said.

In May 1984, Christiansen, joined by Edith Morrison (assistant professor in Periodontics) and U-M alums Joseph Cabot (DDS 1945) and Hugh Cooper Jr. (DDS 1951), participated in a visit to the Peoples Republic of China. The trip was sponsored by the American Dental Association at the special request of the Chinese Medical Association (CMA). The CMA asked members of the 17-person delegation to consult with its professionals on programs that included dental education, public health, research, and organized dentistry. The visit paved the way for future connections between U-M and a number of schools throughout China.[16]

Student exchanges with Nippon Dental University in Japan were established in 1986. That same year, the school and the University of Berne School of Dental Medicine in Switzerland signed a sistership agreement. A signing ceremony took place in the Washington, DC, at the home of the Swiss ambassador.[17]

Reflections

In a memo to the dental school faculty, Christiansen announced on March 18, 1987, that he would not seek a second five-year term as dean. Reflecting on his five years as dean, Christiansen said:

It was an exciting time, not just here at the school, but in the profession too. I have no doubt I made the right decision to come to Michigan. The dental profession was changing, and I wanted to be a part of that change and help shape the new direction dentistry was taking, both academically and clinically.[18]

During his tenure as dean, Christiansen initiated relationships with nine foreign schools of oral health. He was involved in the establishment of the International Union of Schools of Oral Health in 1985. In the late 1980’s he served as a Project Hope consultant in Krakow, Poland. He reviewed the Krakow dental school and helped design, plan and complete the Project Hope Hospital. This was done before Poland became liberated from the Soviet Union. In June 2000, he was awarded an honorary doctorate degree from Nippon Dental University, Tokyo, Japan.

Christiansen’s commitment to global outreach didn’t end when he stepped down as dean. In 2015, a generous gift from Christiansen and his wife, Nancy, established the Richard Christiansen Collegiate Professorship in Oral and Craniofacial Global Initiatives. Dr. Carlos González-Cabezas, director of the school’s Global Initiatives in Oral and Craniofacial Health program was named the first Christiansen Collegiate Professor. The Global Initiatives Program extends the Christiansen legacy as it strives to improve global oral health and promote health equity through education, research and patient care. Dr. Richard Christiansen retired from U-M in January 2001. He holds the titles of Dean Emeritus and Professor Emeritus.