The University of Michigan School of Dentistry - Victors for Dentistry (1962–2017): Decades of Innovation and Discovery

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chapter 1. The Mann Years (1962–1981)

Dr. William Mann became dean on July 1, 1962. He brought to the position extensive experience as an administrator, teacher, and writer. Prior to his deanship, he held a half-time appointment with the American Council on Education as director of the Dental Education section and authored a 183-page report on dental education that was included in the final report—The Survey of Dentistry: The Final Report.[1] This national survey focused on dental health, dental practice, dental education, and dental research and had important implications for dental education and the profession of dentistry.[2]

A Building for the Future

Perhaps the most visual symbol of the dramatic changes that occurred at the School of Dentistry during the five-and-a-half decades from 1962 to 2017 involved the construction of the new dental school building still in use today.

The need for a new facility was critical to the future of dental education at Michigan. The prospectus for the new building, dated February 12, 1964, was blunt in its assessment of the 1908 building. It stated:

The report on accreditation, made by the Council on Dental Education of the American Dental Association in 1961, noted that teaching facilities of the school fail to meet recommended standards for improved clinical and preclinical instruction. . . . Because of limited space the school has been unable to keep pace with the remarkable advances in dental education and research that have been made over the past 20 years. . . . The wholly inadequate research facilities now being used have been improvised from basement storage rooms. . . . Faculty must utilize locker space in the student locker room.[3]

In September 1962, Mann made an administrative appointment that, in hindsight, was crucial to the future of the School of Dentistry when he asked Dr. Robert Doerr to become associate dean. Doerr and Mann spent hundreds of hours with architects discussing in detail what facilities would be needed. Doerr also was instrumental in conducting a survey designed to project the future dental workforce needs of Michigan. Population forecasts and dental workforce data gathered from the survey further guided the planning and design process. Based on the results, it was determined that the new dental building should have enough space to accommodate 150 dental students and 80 dental hygiene students in each class across the respective curricula.[4]

Designing a state-of-the-art facility to educate the leaders and best in dentistry was one thing, but funding this incredible undertaking was quite another. Funding commitments of $13 million from the State of Michigan, $5.6 million from the federal government, and $1.8 million from the Kellogg Foundation were obtained to cover construction costs.[5]

In “A Short History of the University of Michigan School of Dentistry” compiled by Charles Kelsey in 1971, Kelsey notes that the total cost of the dental school project was $17,294,855. At the time this was the largest building contract ever made in the history of the University of Michigan. By comparison, the cost to build the 1908 dental school building was $115,000. An addition to the facility in 1922–1923 totaled $128,000. The adjacent W.K. Kellogg Foundation Institute building was built in 1939–1940 for $450,000.[6]

Additional space was imperative if the School of Dentistry was going to be able to respond to the mandate to increase class size and advance the ever-growing research enterprise. The new dental complex offered significantly more space for all School of Dentistry activities. The 1908 building, including the later addition, was approximately 65,000 gross square feet. The W.K. Kellogg Foundation Institute building provided approximately 50,000 gross square feet. The new dental complex, when completed, would provide more than 293,300 gross square feet and when linked to the adjacent W.K. Kellogg Foundation Institute building would yield a total of 343,000 square feet to accommodate the growing teaching, research, patient care, and support services needs of the school.[6]

The dental school complex: (A) Kellogg wing (west), (B) clinical wing (north), (C) research wing (east), and (D) dental library (south).

The design of the new dental complex consisted of four interconnected structures: the clinical wing (north), the research wing (east), the Kellogg wing (west), and the library (south). To minimize the impact on classroom instruction and clinical operations, the building project was staged in two phases: Phase I included the new clinical and research wings and Phase II included the Kellogg wing and the library.

With design completed and funding secured, construction officially commenced with the groundbreaking on February 2, 1966.

Dean William Mann turns the first shovel at the groundbreaking ceremony celebrating the start of construction of the new dental complex.

Dr. Frank Comstock (DDS 1950), professor and director of clinics (1969–1984), kept a handwritten log of some of the issues that occurred during the construction process. His log provides insight, from a faculty member’s perspective, of what it was like to try to conduct business as usual with the seemingly endless thump of pile drivers as they worked to compress 60-foot tubes of steel into the ground for footings to support this enormous structure.[7]

Construction Delays

In his log, Comstock noted that construction slowed in the spring of 1966 when excavation for the clinical wing and parking structure produced a massive hole that put the Health Services building in jeopardy. Comstock wrote, “Troubles occurred in back of the H.S. where interlocking steel piling [sic] was driven and a retaining wall set up so the H.S would not slide into the excavation.” A tradesmen’s strike in early May stopped all work except for the emergency work needed to complete the retaining wall to stabilize the Health Services building.[8]

Comstock reported that by May 27, 1968, the skeleton of the new building was up with most work being completed inside. The parking structure was essentially finished, but the Fletcher Street entrance was not yet open. Comstock also commented on the Kellogg Foundation Institute’s second summer of remodeling with floors being cut to install control boxes for new Ritter units scheduled to be installed sometime after June 1, 1968. He concluded this entry with the comment that they “continue to be plagued by labor unrest.” Labor issues and strikes were responsible for numerous delays throughout the final year and a half of construction.

Phase I Finished

Everyone was thrilled when Phase I was completed in August 1969, and classes and clinic operations moved into the new structure for the beginning of the fall semester.

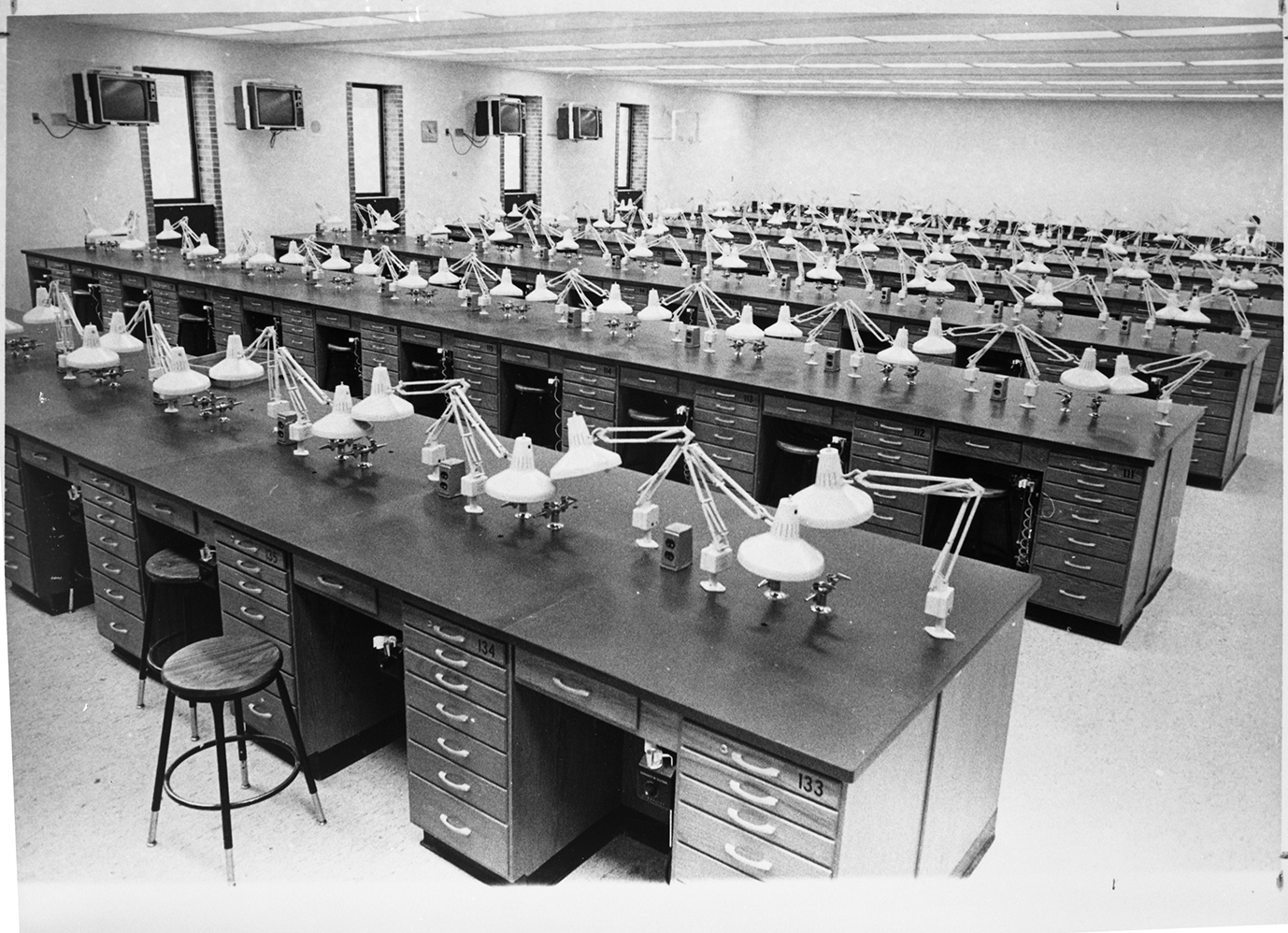

The new clinical wing served as the main instructional facility. This five-story structure featured the very latest in clinical equipment and instructional technology. The basement housed the building’s services. Three 156-seat lecture halls, a seminar room, preclinical laboratories, student locker room, and student lobby occupied the ground floor. Preclinical laboratories, where first- and second-year dental students learned the foundations of clinical procedures and techniques, occupied approximately 7,700 square feet.

The preclinical laboratory on the east side of the ground floor of the new dental building. A second preclinical laboratory was located on the west side.

Clinics were located on the first, second, and third floors. First floor clinics included oral diagnosis, radiology, pediatric dentistry, periodontics and periodontal surgery, crown and bridge, and dental auxiliary utilization. The main dental laboratory was also housed on this level. The senior clinic was located on the second floor. This clinic was divided into four quadrants, each with 36 individually partitioned operatories for patient privacy. Each of the four clinic quadrants had slightly more than 4,000 square feet of space. The junior clinics, general clinics, and the central records room were located on the third floor. The central records room housed both the school’s computing unit and an automatic patient record retrieval system.

The Research Tower

The adjacent nine-story research wing, which over the years became known as the “Research Tower,” also was ready for occupancy in 1969.[10] Administrative offices were located on the ground and first floors with the second through sixth floors dedicated to much needed research space as well as offices for the faculty scientist. Laboratory space in the Research Tower added 21,000 square feet, a crucial addition to the school’s growing research enterprise. The seventh floor housed the Faculty Alumni Lounge that provided space for meetings, conferences, and events. Generous contributions from alumni donors were designated to purchase the furnishings for the Faculty Alumni Lounge.

Architect’s model of the seven-story Research Tower on the east side of the new dental building complex.

With the successful move into the new clinical wing, demolition of the 1908 dental school structure commenced along with site preparation and construction of the Kellogg wing and the library—Phase II of the construction plan.

Phase II Finished

Phase II projects of the new dental complex were completed in 1971. The dental library, a divisional library of the U-M Library, was built on the site of the 1908 dental building and opened for general use in June 1971.[11][12] For the two years the library was under construction, all of its holdings were located in temporary facilities in the basement of the new clinical wing. Faculty and students were thrilled when they could, once again, easily access more than 46,000 items available for circulation and 28,000 copies of reserve materials in the spacious, two-story building.[11][12]The library became increasingly recognized as one of the finest and most complete dentistry libraries in the world.

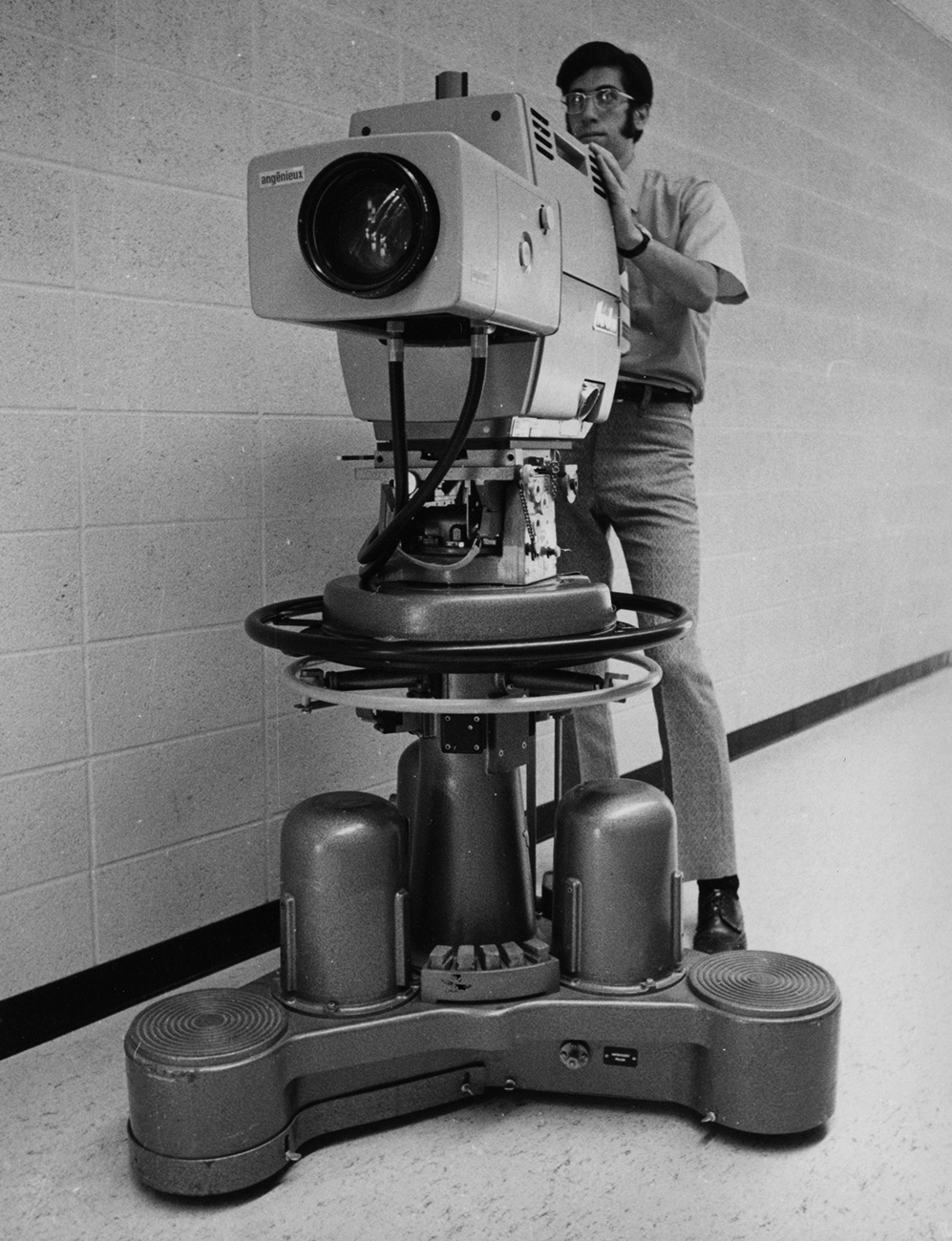

A special enhancement to the teaching program was an instructional television center, located on the third floor of the Kellogg wing. This facility became operational in the fall of 1971 with the help of alumni donors who stepped up and provided funds to assist with the purchase of video equipment for the center, creating a state-of-the-art television studio.

Howard Mevis with one of the TV cameras. Portable cameras could be easily moved about the building to film in many different locations.

The 1,800-square-foot studio was the site where thousands of videotapes on oral health topics and dental procedures were produced and used extensively to educate U-M School of Dentistry students. The videotapes also were distributed to other dental schools and health organizations around the world. As new technology evolved, so did the capability of this facility. Many of these historic videos still are available for viewing today on the U-M Dentistry YouTube channel.[13]

Open House

Before unveiling the new building to the public, dental school administrators held an open house on Sunday, October 3, 1971. In his September newsletter to the school’s faculty and staff, Mann wrote:

Essentially we will be showing off the new facilities; but since they are designed as a setting for modern dental education, we will also be putting the nature of modern dentistry and dental research on display, a thing which is in our interest to do well and to the best advantage. [He expressed his desire] to have all activities staffed and open to view in such a way as to give an impression of the school as it is on a normal class day.[14]

Dedication

The official dedication of the new dental complex was held on October 18, 1971, marking the most significant milestone in the School of Dentistry’s history. As Mann cut the symbolic ribbon opening the new dental complex, he said that the new facility would allow the school to admit more students to study dentistry and dental hygiene and that changes and improvements in the curriculum would now be possible. Those words launched amazing transformations in dental education at U-M that for decades to come would be recognized as a gold standard for curriculum design and educational innovation.

The ribbon cutting ceremony marking the completion of the new dental complex was held on October, 18, 1971.

That same day, a sculpture was unveiled on the plaza adjacent to North University Avenue entrance. A gift from the Class of 1944, the irregularly shaped aluminum sculpture was created by Bill Barrett, a well-known local artist who later moved to New York City. “The sculpture has no title, nor any abstract relation to dentistry or any other subject or object. It does not ‘represent.’ Instead it is an object designed for its place,” Mann wrote. Over the years, however, the sculpture has been often referred to as “The Tooth Fairy.”[15]

“The Tooth Fairy” sculpture off of North University Avenue at the main entrance to the School of Dentistry.

Although the sculptor said the piece was merely an object designed for its place, to the trained eye of many dental professional, it looks to have incorporated the many angles and cuts used in dentistry to create restorative preparations.

Mixed Reactions

The clean lines of the Modernist architecture prominent in structures built in the 1960s and reflected in the esthetics of the new dental complex were disconcerting to some.

Henry Kanar (MS Pediatric Dentistry 1971), a faculty member from 1971 to 1998, remembers overhearing faculty, who repeatedly emphasized the importance of precision in dentistry, jest that “not all the building’s bricks were in a straight line.”

Jack Gobetti (DDS 1968, MS Oral Diagnosis and Radiology 1971), a dental school faculty member for more than 40 years, spent most of his dental school years in the old building. Gobetti thought the new building was a little stark: “The old dental school building had personality and charm with its beautiful wood, brass railings and other features.”

Richard Johnson (DDS 1967, MS Orthodontics 1973), a faculty member for more than 30 years, shared similar feelings: “There was something about the old building that really made it stand out. . . . Foremost, in my mind, was the beautiful wood paneling. It conveyed sophistication and class.

Architectural issues aside, the new building offered students, faculty, and staff much needed space to teach, learn, and deliver state-of-the-art dental care. It also enabled the school to increase class size to address the expected shortages in the dental workforce.

Projecting Dental Workforce Needs

Foremost among the projections was a sharp rise in population. As a manufacturing state whose employers offered good wages and fringe benefits, Michigan was a magnet that attracted men and women from across the nation to work for auto companies and many of their suppliers. In 1970, the state’s population was approximately 8.9 million, an increase of more than 13 percent from 1960. That percentage growth rate matched the growth rate of the U.S. population when the nation’s headcount rose from 179.32 million in 1960 to 203.2 million by 1970.[17] By 1980, the state’s population increased nearly 4.5 percent to 9.26 million.[18]

During this time, the growth of auto manufacturing and membership in labor unions (where nearly 30 percent of wage and salary workers belonged to a union) resulted in a demand not just for higher wages, but also for fringe benefits, including a new one—dental care—which, in turn, led to increased demand for oral health-care professionals. “Union contract negotiations are now heading toward incorporation of dental service as a fringe benefit. Such a fringe benefit will increase the demand for dentists,” according to minutes of an April 13, 1973, meeting of the U-M’s Office of Capital Planning, whose members met with School of Dentistry administrators to discuss the school’s needs. Minutes from the same meeting noted, “there is a possibility of a tremendous increase in demand for dental care. In the neighborhood of only 40–50 percent of the population now sees a dentist each year.”[19]

The Need for More Dental Health Professionals

The American Dental Association (ADA) reported there were 4,734 dentists in Michigan in 1970. The U-M Long-Range Planning Subcommittee on School and College Planning met with the School of Dentistry leadership on December 1, 1972, to review population and workforce data in Michigan. The dentist-to-population numbers presented showed “the ratio in Michigan is 1 dentist for every 1,850 population compared to the national ratio of 1:1,683.”[20] A shortage of dentists in Michigan was looming.

The impetus to increase the number of dental students graduating from the U-M School of Dentistry also was driven by fears about the long-term viability of the state’s other dental school. According to minutes from that same December 1972 meeting,

The University of Detroit Dental School is in financial trouble . . . U of D administrators feel that their dental school can last approximately five years. . . . Legislators are worried about the impact of these trends, and are working with the dean and the Executive Committee to plan for the state’s dental needs in the next ten to fifteen years. [20]

Dental and Dental Hygiene Enrollments

From the mid-1940s through the opening of the new dental building in 1971, first-year dental class enrollment averaged 90 students per year. As had been planned, the additional space, both classroom and clinic, in the new building allowed the school to increase the doctor of dental surgery (DDS) and dental hygiene class sizes. By the mid-1970s, first-year enrollment in the dental program increased to more than 150 students with largest class of 154 students admitted in 1975.[21]

| Students entering the fall of: | Total Admitted* |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 132 |

| 1971 | 135 |

| 1972 | 150 |

| 1973 | 152 |

| 1974 | 151 |

| 1975 | 154 |

| 1976 | 152 |

| 1977 | 151 |

| 1978 | 151 |

| 1979 | 151 |

| 1980 | 151 |

Throughout the 1970s and into the early1980s, the number of graduating dental students ranged from a low of 83 in 1971 to a peak of 151 graduates in 1978.

Opening the new dental building in 1971 was a milestone for the dental hygiene program. The annual admissions cap of 39, necessitated by severe space limitations, was raised to 80. The program maintained that class size until 1980.[21][22]

| Year of Graduation | Total DDS Graduates* |

|---|---|

| 1970 | 92 |

| 1971 | 83 |

| 1972 | 100 |

| 1973 | 117 |

| 1974 | 122 |

| 1975 | 140 |

| 1976 | 136 |

| 1977 | 149 |

| 1978 | 151 |

| 1979 | 139 |

| 1980 | 140 |

Students entering the dental hygiene curriculum in the 1970s were enrolled in either a two-year program or a four-year program. The two-year curriculum was designed to train women to become dental hygienists. A limited number of students were admitted as freshmen directly from high school each fall. After successfully completing the program, they received a certificate in dental hygiene. The four-year curriculum consisted of two years of liberal arts education followed by two years of dental hygiene study at the School of Dentistry. The four-year program was designed for those who wanted to prepare themselves to become teachers or leaders in the dental hygiene profession. At graduation, students received a Bachelor of Science degree in dental hygiene.[21]

Under the leadership of Pauline Steele, director of the dental hygiene program 1968–1988, the number of dental hygiene students graduating with either a certificate or a bachelor’s degree increased from 38 graduates per year in 1970 to 79 per year in 1980.

The significant increases in the number of dental and dental hygiene students enrolled in a degree or certificate program at the School of Dentistry was expected. Both school and U-M leaders, who in the years leading up to the groundbreaking for the school’s new facilities, had carefully researched projections related to population growth and health-care workforce trends in Michigan and across the nation.

Total enrollment for all groups, including graduate programs, increased markedly from 1970 to 1979. The school enrolled 669 students at the start of the 1970 academic year. By the 1979 academic year, the total enrollment number had increased to 849 students across all programs. During this time period, the enrollment numbers peaked in 1976 when total enrollment for all programs reached 854 and the four DDS classes totaled 602. The master’s program experienced a dramatic rise in 1979.[22]

| Year | Total | DDS | DH | Master’s | PhD |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1970 | 669 | 441 | 134 | 89 | 5 |

| 1979 | 849 | 591 | 157 | 100 | 1 |

Health Professions Educational Assistance

To help meet the growing demand for dentists, physicians, and other health professionals, Congress enacted the Health Professions Educational Assistance Act in 1963. The act authorized two significant initiatives. The first was a construction grant assistance program to help build new facilities to increase capacity for schools of medicine, dentistry, osteopathy, optometry, pharmacy, podiatry, public health, and professional nursing. The second important initiative was a student loan program to help talented, but needy students afford the significant costs associated with pursuing a career in the health professions.

After the act was passed, the U.S. Public Health Service advised Congress that the nation faced a severe shortage of approximately 17,800 dentists during the 1970s. “While these figures are most astounding, the projected shortages for 1980 are even more frightening. Based on present policy trends, manpower shortages for the end of this decade are expected to number 56,600 dentists,” the U.S. Public Health Service noted in a report. Congress amended the act several times following passage in 1963 with some of the most extensive additions and modifications made in the passage of the Comprehensive Health Manpower Training Act of 1971.[23] This act raised incentives for increasing enrollments and graduates, and shifted emphasis from construction support to institutional support to schools.

Capitation Grants

Important to the School of Dentistry was a major new provision in the 1971 act, per capita assistance, more commonly referred to as “capitation grants.” These grants were awarded based on a headcount of students with the goal to help schools stabilize their finances. The grants also were designed to help dental, medical, and other health-care schools attract students who, after graduation, could meet the growing demand for dental and other health-care services in areas of need, especially rural communities and inner cities.

In a letter dated April 25, 1972 to U-M Vice President for Academic Affairs Allan Smith, Dean Mann outlined the school’s financial picture and concluded, “The School of Dentistry is deeply dependent upon the funds which will be provided by the 1972–73 capitation grant in order to carry on its programs.” The amount cited in the letter was $1 million.[24] On August 8, in another memo to Smith, Mann advised the school was awarded a capitation grant of $1,047,869 for the 1972–1973 academic year. He also noted a “bonus class” clause in the capitation grant language. “This means that for the next three years, or four, if similar legislation is continued, we will receive $150,000 more than we were entitled to on the basis of enrollment only.”[25]

An important provision of the 1971 act was awarding education grants to students enrolled in schools of dentistry, medicine, osteopathy, and other health professions. Per-student grants of $2,500 were awarded for full-time first-, second-, or third-year students. The amount increased to $4,000 for fourth-year students. The act also provided for partial loan forgiveness to students if they worked in areas, such as rural areas and inner cities, where there were health-care workforce shortages. Loan forgiveness totaled 30 percent each year for the first two years of service and 25 percent for the third year. It also allowed public and private nonprofit schools of dentistry, medicine, osteopathy, veterinary medicine, public health, pharmacy, podiatry, or a combination of those schools to apply for construction grant assistance.[26]

Dental School Funding

The School of Dentistry pursued a two-track strategy. The first was to take advantage of federal legislation. The second was to work with top U-M administrators and state legislators in Lansing to try to obtain additional state funding to run the dental school.

First-year dental student enrollment increased from 132 in 1970 to 152 in 1973. An additional increase to 165 was proposed for 1975. Concern was expressed among School of Dentistry administrators that the number of first-year dental students would continue to increase beyond 151 students. Just two years after the new dental school building opened, minutes from the April 13, 1973, budget meeting show Mann advising: “The school’s dental facilities were built for the present class size of 150. The (proposed) increase to 165 (first-year dental students) in 1975 will cause some overcrowding.”[27]

In a seven-page letter to U-M Vice President of Academic Affairs Frank Rhodes dated January 6, 1975, Mann reported:

When funds for its new building were approved, the School agreed to expand the size of its student body. Fortunately, during the past several years the School of Dentistry has been successful in persuading the State Legislature to appropriate annual increases for its operating budget which were large enough to permit the school to fund its programs reasonably well as its enrollment increased. In addition, for the past two years, the school has received a sizable amount of money from the federal government in the form of a “capitation grant” that could be used for operating purposes as related to the DDS program. [28]

On page 2 of that letter, Mann included this phrase: “the line item appropriation for the School of Dentistry.” Those nine words were revealing.

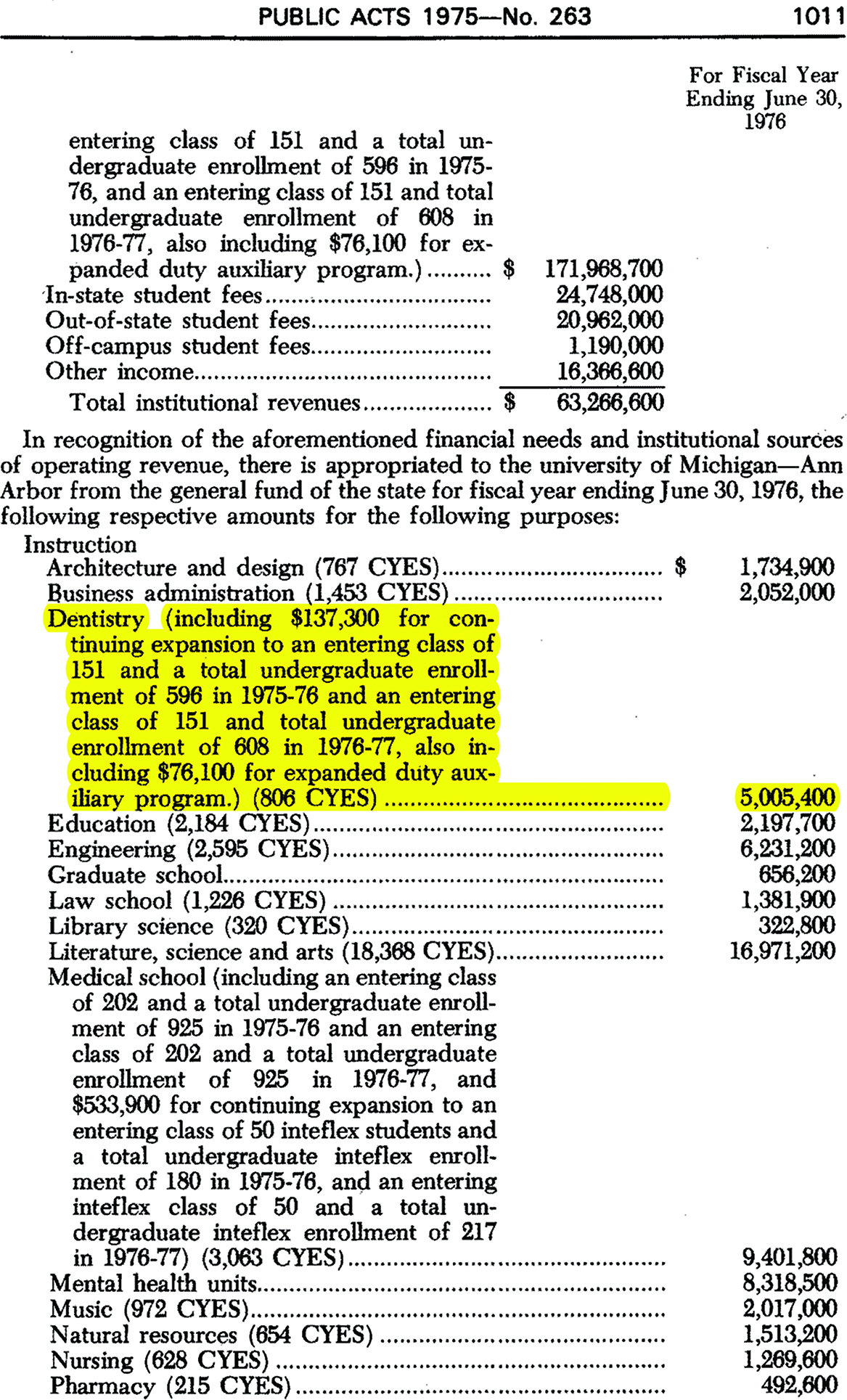

Typically, a single-dollar amount labeled “University of Michigan–Ann Arbor” was noted in the state budget. However, from 1970 through 1985, instead of being lumped into the university’s total budget, the state specifically set aside funds for the School of Dentistry as a separate line item for two of its crucial functions. One was for administration and operations and the other to help cope with increases in class size.

Jed Jacobson (DDS 1978), former faculty member who served as assistant dean for admissions as well as assistant dean for community and outreach programs, said: “We as faculty members knew about the line item in the state budget for the school.” The significance was lost on no one because the School of Dentistry having a separate line item appropriation in the state budget meant that vital funds were being given to the school to support the demands of DDS program.

Page 1011 from Public Acts 1975–No. 263 for fiscal year ending June 30, 1976, specifying special appropriations for the School of Dentistry.

In 1970, for example, the state specifically approved a $3.8-million appropriation “for administration and operation of the dental school.” An additional $497,400 was set aside “for expansion to 130 (entering) class level.” In 1971, $4.4 million was listed in the state budget for administration and operation of the dental school and another $320,000 appropriated to expand the size of the first-year dental class to 145 students. From 1970 to 1975, the school received nearly $1.8 million in additional appropriations to enable it to enroll more dental students. Between 1970 and 1985, the school received more than $97.6 million for administration and operations. Separately, between 1970 and 1975, nearly $1.8 million more was appropriated to allow the school to increase enrollment to accommodate 130, 145, 150, and ultimately 151 first-year dental students.[29]

Curriculum Review

Periodic curriculum review is essential in dental education. As research informs dental practice, then products, techniques, and technology must be taught to the students and the dental curriculum must adapt.

In 1962, the school’s Committee on Curriculum conducted a comprehensive review and began designing a progressive new dental program to graduate practitioners possessing the skills, competencies, and intellectual adaptability to cope with both present and future requirements of oral health care and practice. The committee sought opinions from faculty, students, and alumni in 1964 and 1965. In August 1967, a faculty conference was conducted in Ann Arbor, at which time details of the new dental curriculum were presented to the dental faculty and to members of the basic science departments of the Medical School who taught dental students. The faculty adopted the new curriculum that was launched in the fall of 1969 and coincided with the opening of the clinical wing of the new dental complex.[30]

The new DDS curriculum was designed for flexibility to accommodate changing concepts in how dentistry was practiced and focused on the activities and initiatives of the 18 different departments within the school. Those departments (in alphabetical order) were as follows: Community Dentistry, Complete Denture Prosthodontics, Crown and Bridge Prosthesis, Dental Materials, Dentistry in the University Hospital, Educational Resources, Endodontics, Occlusion, Operative Dentistry, Oral Biology, Oral Diagnosis and Radiology, Oral Pathology, Oral Surgery, Orthodontics, Partial Denture Prosthodontics, Pedodontics, Periodontics, and Preclinical Dentistry.[30]

New Technology Enhances Curriculum

In an annual report to the president of U-M for the 1977–1978 academic year, Mann noted that nearly 350 television recording and editing sessions had been conducted and “playbacks of tapes to classrooms and duplications (of those videotapes) for local and international distribution reached their highest level (3,908) since the school’s inauguration of television use in 1970.”[31] Under the direction of Dr. David Starks, chair of the Department of Educational Resources, who assumed his duties in July 1972, original photography, film processing and printing, and television and video production were done in-house by the department’s staff.[32]

In 1975, the Department of Educational Resources won first prize from the Health Sciences Communications Association and the Network for Continuing Medical Education for the use of television for education in the health sciences. Holding the plaque are Dr. Robert Lowery (L) and Mr. Charles Eddlemon.

Building the Video Library

For more than 20 years, the staff in the Department of Educational Resources worked closely with the faculty to incorporate photography, videography, and dental and medical illustration into the curriculum to enhance learning. Many of the lectures and demonstrations transmitted to classrooms and laboratories via the school’s television studio were captured on videotape.

In a July 17, 1984 memo to the school’s Budget Priorities Committee Starks noted:

Since the early 1970s, the contributions of television to the quality of dental teaching have been widely recognized. . . . Faculty have adopted television into their teaching to such an extent that, on average, each student views one videotape per day throughout most semesters.

Noting that “more than 1,000 tapes in our current library” were produced between 1972 and 1984, Stark added that “faculty at schools throughout the country and around the world are looking to Michigan to supply tapes for teaching in a variety of fields.” He also noted sales of the videotapes provided income for the school that ranged from $14,000 to $60,000 annually. Ultimately, nearly 2,000 videotapes related to a host of dental topics covering clinical and laboratory procedures were produced in the television studios on the third floor.

In July 1972, the school received a $700,000 federal grant to establish a pilot program in dental education that allowed students to advance through the dental curriculum at their own individual rate of learning. Funds were used to construct an independent learning center, known as CAIDENT (Computer-Aided Instruction DENTistry). The library-like facility, located in the basement of the new dental building, occupied about 2,400 square feet of floor area and provided instructional materials to students and faculty that included videotapes of lectures captured in the television studio, 35-mm slides, audiocassettes, or printed handouts.[33] It also had an audio engineering studio where faculty often narrated scripts they wrote to accompany a lecture or technique they were teaching.

Behind the Camera

Per Kjeldsen, a photographer at the School of Dentistry for more than 32 years, said the school’s embracing of new technology “was one of the major reasons I came to Michigan from the Rochester (New York) Institute of Technology.” When he arrived at U-M in 1974, the school was developing self-instructional materials for education and research, and photography was an important part of those materials. “I wanted to be involved in those efforts,” he said.

As chief photographer from 1974 until 2006, Kjeldsen probably met, even if for only a few moments, every dental and dental hygiene student as he was taking their individual portraits for a composite class picture. It is also safe to say that he has met every dean, every administrator, every faculty member, and nearly every staff member as well. It is a claim few can make.[34]

Although he has photographed many school events, Kjeldsen says:

[Graduation] is one event that hasn’t changed over the years, and that’s a good thing! The pride and joy that is reflected in the faces of the students, their parents and instructors is wonderful. I feel privileged to have captured so many of these special moments. (Personal communication, August 21, 2015)

During the pre-digital age, producing the class composites was a laborious work of art. After taking photos of all the students, the individual portraits were manually attached to an oversized board that Kjeldsen then sent to Florida. There, a calligrapher inscribed the name of each dental class and each dental student. The finished board was then shipped back to Ann Arbor and a large negative was made of the board with all the photos and student names. Today, computer software makes producing both the class composites and the graduation composites much easier. The graduation composites of all of the dental and dental hygiene classes dating back to the very first DDS class are on display along the ground floor hallways near the lecture halls and in the Alpha Omega Student Forum.

Professionalism and Appearance

When he began his teaching career at the School of Dentistry in 1970, Dr. Richard Johnson said “there was an aura of professionalism that permeated the school because of the dress code.” Perhaps the most apparent feature of the dress code “was that men had to wear a sport coat and tie, and women had to wear dresses. “To many, appearance mattered since it conveyed the professionalism of the dental profession,” he added.

As the decade of the 1960s gave way to the decade of the 1970s, fashions transitioned to a blend of hippie chic and bohemian mod. The clothing worn by dental students became a significant concern for many administrators and faculty who felt the attire seen throughout the dental school was sliding.

The front page of the March 18, 1970, issue of a school newsletter, SSF Relater: A Publication by and for Students, Staff and Faculty, reported, “The issue of student dress and appearance was discussed at several faculty meetings and at meetings within each department.”

The article continued:

The matter of appearance is of great importance to the dental profession. The maintenance of respect of as much of the population as possible is vital to keep the confidence of the people and as a result continue the service on a high level. To a large segment of the population, the matter of appearance seems to play a major role in personal evaluation.[35]

By the mid-1970s, the dress code had been relaxed considerably. Jed Jacobson (DDS 1978) said “we were not wearing ties in 1974 when I began my dental education.”

The importance of personal appearance as well as posture had long been emphasized in the dental hygiene program as well. Former students still have vivid recollections of Dr. Dorothy Hard, dental hygiene director 1928–1968, and the emphasis she placed on neatness and appearance. Two women graduates of the first class of the school’s Master of Science in dental hygiene program, Karen Ross Peterson and Sandra Sonner Klinesteker, clearly remember Hard’s sage counsel.

Karen Ross Peterson (R) and Sandra Sonner Klinesteker were among the first graduates of the Master of Science in Dental Hygiene program. Peterson is holding her master’s thesis published in 1965.

Peterson recalled, “Dr. Hard presented herself very professionally and expected us to do the same.” Klinesteker agreed, adding, “Dr. Hard always emphasized the importance of appearance because it conveyed professionalism.” Klinesteker also remembered Hard’s emphasis on keeping one’s fingernails trimmed to reduce the risk of bacterial infection. Klinesteker said with a laugh:

She told us our nails had to be short enough so that when we held up our hands, palms facing us, we couldn’t see our nails. Of course, we didn’t wear gloves at that time. But we did wear a white uniform dress and nurse’s cap when in clinic treating patients.[36]

Community Outreach

The new curriculum created enhanced learning opportunities for students and allowed for additional oral health care to be provided in communities throughout Michigan. For more than 80 years, the school has been engaged in community outreach dentistry. In the late 1930s, help from the W.K. Kellogg Foundation enabled senior dental students to travel to county health departments in southwest Michigan to participate in one-week “field trips,” as they were called at the time, to gain a better understanding of local oral health-care needs. In the 1950s, dental and dental hygiene students treated inmates at the Michigan State Prison in Jackson. Beginning in the late 1950s, dental students traveled to the Bay Cliff Health Camp northwest of Marquette during the summer to address the oral health needs of developmentally disabled children and adolescents ages 3–17. During the 1960s, dental hygiene students participated in summer fluoride programs throughout Michigan, applying topical fluorides to school-age children.

Community Outreach Emerges

In the fall of 1971, the Department of Community Dentistry launched a pilot program for 3rd year dental students to visit various community health agencies to observe and verbally interact with members and patients at the agency. The pilot was so successful that the program was expanded to include 4th year students. No funds were allocated to support community outreach and all services were provided pro bono; yet the program grew and by 1974 participating agencies included Cassidy Lake Technical School, Milan Correctional Institution, Wayne County General Hospital, Washtenaw Community College, Model Cities, Sumpter Health Center, and Saint Louis Boys School for the Retarded. The summer migrant program also added sites throughout the state. From the start, the students loved the opportunity to serve the community as well as to gain clinical experiences beyond the walls of the school. [37]

Outreach became so popular with the students that a lottery system had to be initiated to manage all of the students wanting to participate. Graduates generously gave back to the school with donations to support the program.

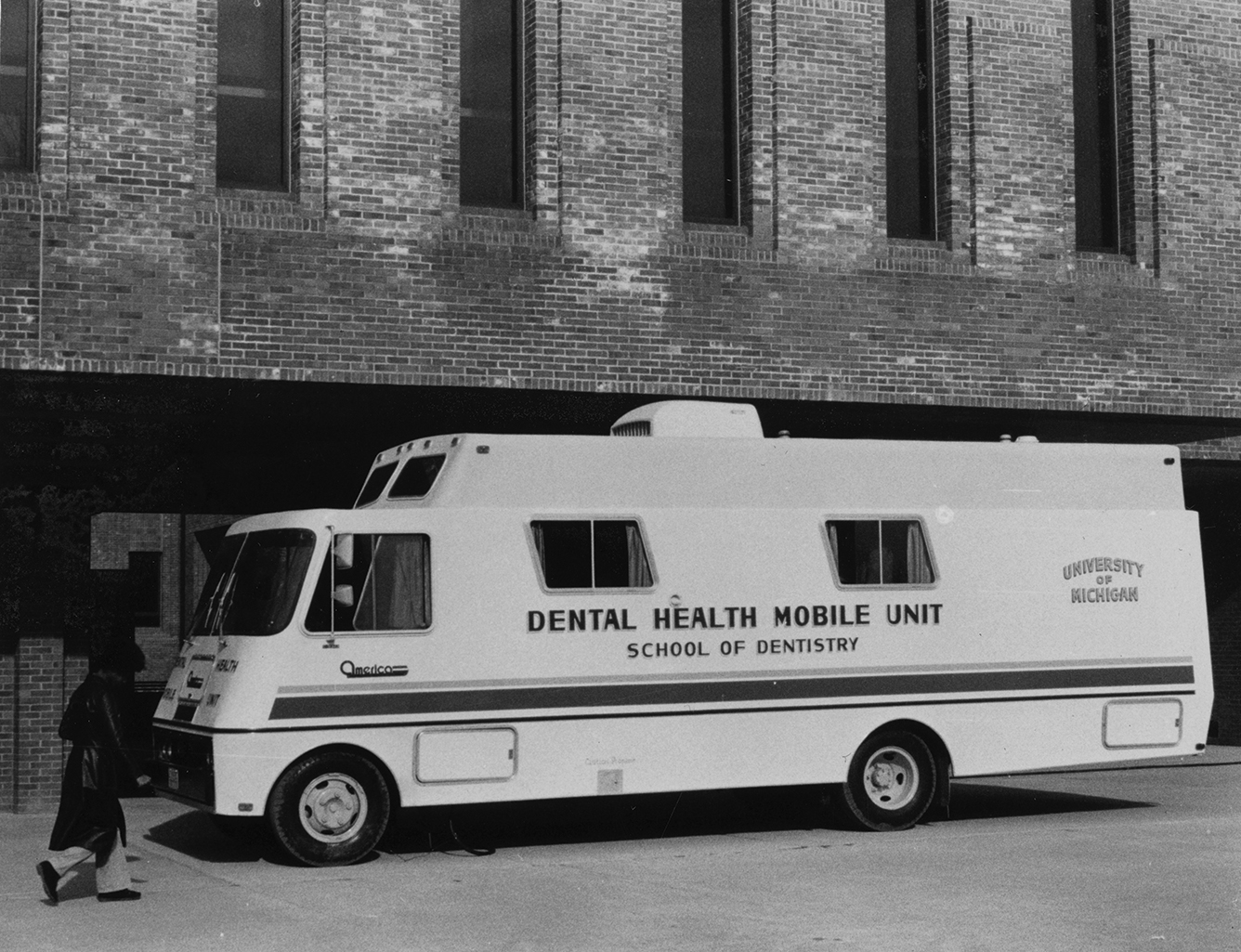

Mobile Dental Vans

A research grant awarded to Dr. Robert Bagramian, chair of the Department of Community Dentistry with a PhD in oral epidemiology, allowed the school to purchase two fully equipped dental vans to use as mobile dental offices. The vans traveled among a group of select Ypsilanti and Willow Run schools. The five-year study was designed to determine the benefits of dental care given to school-age children. Dental care services included fillings, sealants, and fluoride and ultimately showed an 85-percent reduction in dental disease in the study population. When the study ended, Bagramian contacted the National Institutes of Health (NIH) and requested that the dental school be allowed to retain the dental vans. The NIH approved this request. Mobile dental units were exactly what the Department of Community Dentistry faculty needed to launch new outreach initiatives. The Community Dentistry faculty ran this program until the vans were decommissioned in 1997.

One of the School of Dentistry’s mobile dental health unit vans sits in front of the building, ready for service.

“Initially, the concept of community outreach was not enthusiastically embraced by the clinical faculty. Since the outreach program was not a formal part of the curriculum, many faculty members were reluctant to give up control of clinical instruction in this way,” Bagramian recalled when reflecting on the early years of the outreach program. But Bagramian persisted and after many meetings with the school’s Executive Committee where he repeatedly made the case for community outreach experiences for students, he was given the green light to proceed. In the summer of 1972, the mobile dental units, each equipped with two dental chairs, dental instruments, and equipment that included an X-ray machine and sterilization facilities, traveled to a tomato-processing plant in Adrian, Michigan, and provided dental care for the migrant workers at that site.

Jeffrey Daulton (DDS 1991, MS PedDent 1997) delivers dental care to a patient in the school’s mobile dental unit. Anthony Bielke (DDS 1991) works at the dental chair in the rear.“

Of course it didn’t take long for the word to spread,” Bagramian said. “The managers of a migrant site in Stockbridge heard about the dental services we were providing in Adrian and said, ‘How soon can you come to us.’ ”

Bagramian continued to champion the outreach program and the favorable results of the efforts in Adrian and Stockbridge led to the launch of the Summer Migrant Dental Clinic Program in the Traverse City area. The Traverse City program allowed 32 fourth-year dental students to spend two weeks each during the six-week summer program treating children and adults. About 3,000 migrant workers and their children received care. During the day, children between the ages of 4 and 13 received screening examinations, fluoride treatments, and other needed dental care. An evening clinic was set up so that the parents, who worked in the fields during the day, could also receive dental care. Another opportunity was made available to dental students to gain experience providing care to patients with special needs at a summer camp near Ortonville, just southeast of Grand Blanc, where they treated children with hemophilia.[38]

The outreach experiences have been highly regarded by dental students. Students value the opportunity to care for patients they typically do not see in the School of Dentistry clinics. These experiences have also helped many dental students decide on a particular area of dentistry they enjoy or a specialty they wish to pursue. The success of the Summer Migrant Dental Clinic Program was a stepping-stone to a major expansion of the school’s community outreach program in the spring of 2000.

Community Dental Center

Community outreach took another step forward in January 1981 when the school, in cooperation with the city of Ann Arbor, established the Community Dental Center (CDC) at 406 N. Ashley Street in downtown Ann Arbor.[39] Once again, Bagramian saw an opportunity to provide special clinical experiences for the students, while at the same time providing much needed care to the underserved people of Ann Arbor.

The clinic, originally housed in the Summit Medical Center, was setup as a component of Ann Arbor’s Model Cities initiative that later was spliced into the federal Community Development Block Grants (CDBG) program. The Summit clinic was woefully inadequate and a new dental clinic building was built at the north Ashley Street location with a $200,000 grant from the CDBG program. However, the dental clinic did not open as anticipated. When Bagramian learned of a vacant dental clinic in the heart of Ann Arbor, he immediately arranged a meeting with Mayor Louis Belcher. After listening to the ideas as to how the school could use the space and also help the community, Belcher said, “Get me a proposal as soon as you can.”

The CDC was started by Bagramian (chair) and Paul Lang (faculty member) in the Department of Community Dentistry. It was, and still is, a joint cooperative venture between the City of Ann Arbor and the U-M. The city provided the building and limited financial support for the clinic, while the dental school provided equipment, staffing, and administration. The original goal for the CDC was that it be self-sustaining, providing a full range of oral health-care services for citizens of Ann Arbor and training for students in the area of dental public health, but subsequently it expanded its scope to include residents of Washtenaw County and clinical experiences for dental students.

Over the years, third- and fourth-year dental students have gained valuable clinical experience providing restorative, surgical, periodontal treatments, and emergency care. In recent years, second-year dental students are there as well observing how a dental office runs, assisting the dentists, participating in infection control procedures, reviewing patients’ health histories, and taking radiographs.

Research

Since 1903, when Dr. Marcus L. Ward began to study the properties of dental amalgams used as a filling material, the School of Dentistry has been, and still is, recognized as a leader in dental research, both in basic sciences and clinical fields.[40] A lack of space in the 1908 dental building significantly limited research. With the addition of 21,000 square feet of laboratory space in the new Research Tower, there finally was room to accommodate the school’s growing research enterprise.[41]

The School of Dentistry, in cooperation with the Medical School and the School of Public Health, requested the National Institute of Dental Research (NIDR) support the development of a university-based Dental Research Institute (DRI) on the Ann Arbor campus. In 1967, it was established. The purpose of the DRI was to formalize, expand, and better organize research training relevant to oral health. It was supported primarily by a grant from the NIDR of the U.S. Public Health Service.[42]

Michigan’s DRI attracted leading scientists in microbiology, biochemistry, immunology pharmacology, physiology, and the emerging field of genetics. Clinical scientists in periodontology, pathology, and occlusion also joined this group. As a result, the DRI encouraged the development of multidisciplinary programs where basic and clinical scientists collaborated to address problems such as dental caries (cavities), periodontal disease, and others. Dr. Dominic Dziewiatkowski, recruited from The Rockefeller University, was named chair of the Department of Oral Biology and DRI director in July 1967. He served until 1972 and was succeeded by Dr. Harold Löe (1972–1975) and Dr. James Avery (1976–1989).[43]

The DRI was funded largely with federal grants. During the 1977–1978 academic year, sponsored research expenditures for the institute and the school totaled $2.42 million, with federal funds making up nearly $2.2 of that amount.[44]

The Michigan Longitudinal Studies

The results of much of the research became known worldwide. A pioneer whose work advanced the treatment of periodontal disease was Dr. Sigurd Ramfjord, chair of the Department of Periodontics from 1963 to 1980. Ramfjord and his team conducted the first longitudinal study of its kind in periodontics. For 10 years, they examined the effectiveness of four techniques used to treat periodontal defects: scaling and root planning (nonsurgical), gingivectomy (removing diseased tissue by surgery), flap surgery including osseous contouring, and the “Modified Widman Flap” which was not as invasive. Dr. Gloria Kerry (DDS 1956, MS Periodontics 1966) who worked in the Ramfjord lab said the results were extremely positive: “All the procedures were successful treatments when they were combined with visits for periodontal maintenance. . . . This meant that people could keep their teeth for many years and that old age didn’t mean getting dentures.”

The Michigan Concept

Ramfjord organized the first world workshop on periodontics in 1966 where scientific goals for the field of periodontics were established. The results of his work led to the development of a dental education program that became known as “The Michigan Concept,” a program that has been emulated worldwide.[45][46]

“This research made a lasting impact on future dental care,” Kerry said. “Dr. Ramfjord should be remembered as a distinguished faculty member and as an inspirational mentor and teacher.”

One dental student Ramfjord persuaded to return to Michigan to earn a master’s degree was Dr. Gloria Kerry (DDS 1956).

“He urged me not to put off my studies and to come back to school and work for a master’s degree in periodontics,” she said. “But I had three small children; the youngest was three months old. I had to promise that I would complete my studies in three years and also complete my thesis.” Kerry began working for her master’s degree in periodontics in September 1963 and earned her degree in 1966.

Eight years later, Kerry said Ramfjord called her and asked if she would be interested in teaching periodontics at the School of Dentistry. Reluctant to do so because she was now raising five children, Kerry agreed to accept his invitation to start as an assistant professor.

Kerry said she enjoyed clinical dentistry in general and working with patients in particular. Ramfjord asked her to be a clinical investigator in a longitudinal study that was evaluating different methods of periodontal treatment. This revolutionary approach was Ramfjord’s landmark study, the Michigan Longitudinal Studies, which began in the early 1960s. The statistically designed research included various periodontal treatments.

Kerry successfully juggled both family and academic demands and in 1979, she was promoted to full professor with tenure. “To Dr. Ramfjord, I don’t think having a woman in the program was unusual because women dentists were common in Europe. He treated me as an equal,” she said.

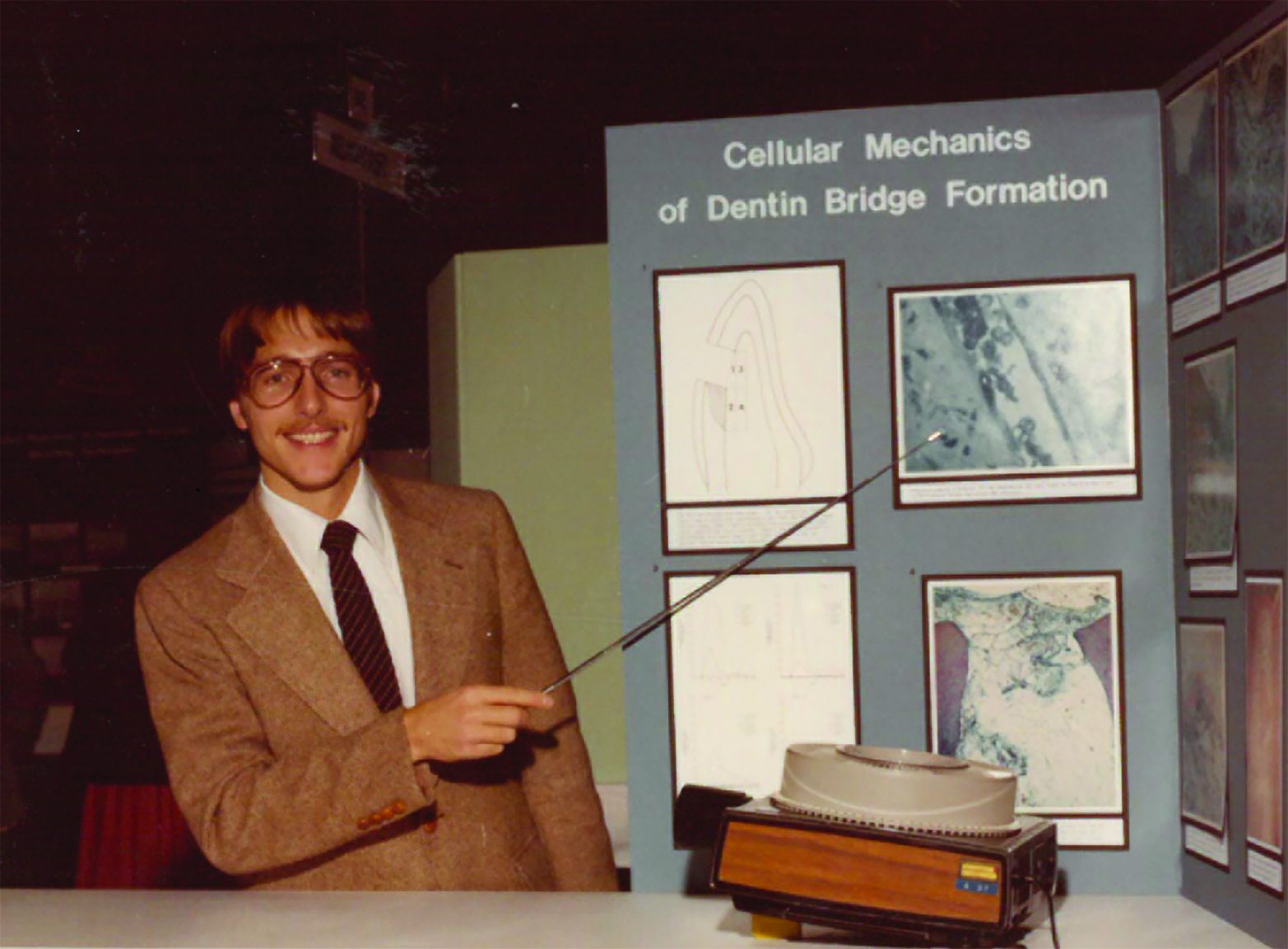

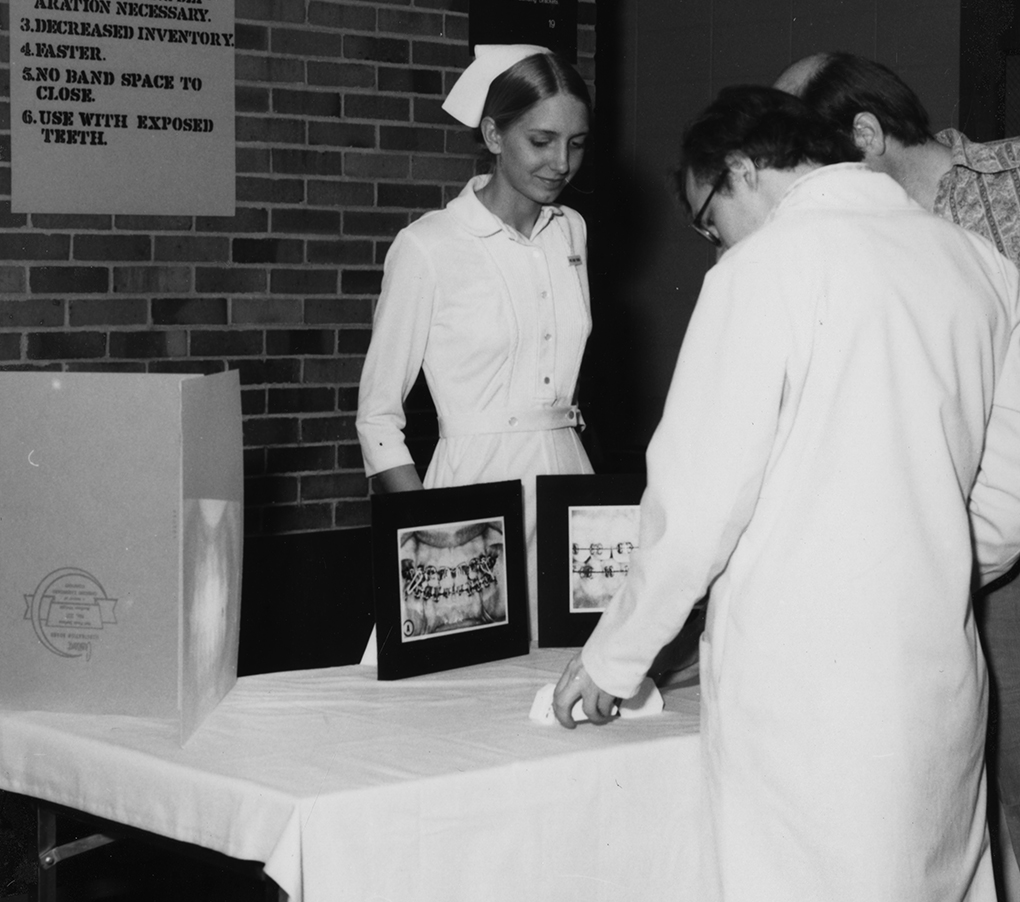

Student Table Clinics

In addition to research by faculty, dental and dental hygiene students and dental assistants were urged in the 1960s to participate in the school’s “Table Clinics.” These were tabletop demonstrations of techniques or procedures that focused on some phase of dental research, diagnosis, or treatment. Each student presented a 15-minute summary of their project which was often supplemented with visual aids, models, and casts.[47]

This was a competitive event and showcased student research. Some Table Clinic winners represented the School of Dentistry at the ADA annual session and competed with winners from other dental schools across the country.[48]

After the new School of Dentistry building opened in 1971, the table clinics were held on the ground floor in the Student Forum. As participation grew in later years, the program was moved to the Michigan League Ballroom, where more space was available.

Mark Fitzgerald presented his table clinic at the 1979 ADA national student table clinic competition. His table clinic won first place in the ADA competition.

In 1979, Table Clinic Grand Prize winner Mark Fitzgerald represented the School of Dentistry during the ADA’s annual session and won two major awards. One was as First Place winner in the ADA’s national table clinic program and the Academy of Operative Dentistry’s Outstanding Achievement Award. He was also invited to present his research at the annual meeting of the International Association for Dental Research and won second place in the Edward H. Hatton Awards competition for junior investigators. After earning his dental degree from U-M in 1980, he joined the School of Dentistry faculty as a part-time clinical instructor. He has been a full-time faculty member since 1990, holding the rank of associate professor and serving as associate chair in the Department of Cariology, Restorative Sciences and Endodontics. In 2017, Fitzgerald was named Associate Dean for Community-Based Collaborative Care and Education.[49]

Student participants in the Table Clinic program present a summary of their projects to faculty, staff, and students.

The annual program, now known as Research Day, continues and is a forum that provides students a mechanism to showcase research projects they are involved in, share scientific interests with the dental school community, and develop professional communications as they present their research.

We Write the Books

The school’s reputation was continually enhanced as faculty members gained recognition for the textbooks they either published or edited. These texts were the ones commonly used in classroom and clinical education at dental schools nationally and internationally. This rich heritage is a source of pride for many U-M dentists and dental hygienists. One of the dental students and later a dental instructor was Dr. Jack Gobetti. “I had the privilege and honor of being educated by and teaching with some of the greats in dental education. Many of them, literally, wrote the books that we used in dental education. My professors were giants of our profession,” he said.

Drs. Sigurd Ramfjord and Major Ash published Occlusion in 1966. According to the school’s Alumni Bulletin 1970,[50] “the book is widely being used by dental schools throughout the world.” The fourth edition was published in 1995. A prolific writer, Ash authored or coauthored other books that were published in French, German, Italian, Spanish, Portuguese, and Japanese.[51]

Other textbooks published by School of Dentistry faculty members that were widely used in dentistry included Oral Diagnosis by Drs. Donald A. Kerr, Major M. Ash, and H. Dean Millard (first published in 1959); Differential Diagnosis by Dr. Major Ash (1960); Dental Materials: Properties and Manipulation by Dr. Robert Craig (1975); Oral Surgery by Dr. James R. Hayward (1976); Dental Materials and Their Selection by Dr. William J. O’Brien (1978); and Handbook of Orthodontics by Dr. Robert E. Moyers (1958, 1973).

In subsequent years, other School of Dentistry faculty members authored or coauthored important textbooks in dentistry and oral health. Some of those include Basic Oral Physiology by Robert M. Bradley (1981); Oral Development and Histology by Dr. James K. Avery (1994); Essentials of Oral Physiology by Robert M. Bradley (1995); Essentials of Oral Histology and Embryology: A Clinical Approach by Dr. James K. Avery and Professor Pauline Steele (2000); Orthodontics and Dentofacial Orthopedics by Dr. James McNamara (2001); Treatment Planning in Dentistry by Dr. Stephen Stefanac (2006); Clinical Research in Oral Health by Drs. William Giannobile and Brian Burt (2010); Oral Health-Related Quality of Life by Drs. Marita Rohr Inglehart and Robert Bagramian (2011); Mineralized Tissues in Oral and Craniofacial Science: Biological Principles and Clinical Correlates by Drs. Laurie McCauley and Martha Somerman (2012); Osteology Guidelines for Oral & Maxillofacial Regeneration Clinical Research by Drs. William Giannobile, Niklaus Lang, and Maurizio Tonetti (2014); and Cone Beam Computed Tomography in Orthodontics: Indications, Insights and Innovations by Dr. Sunil Kapila (2015).

Reflections

A former faculty member who remembers Mann well was Dr. John Drach. Drach was interviewing for a faculty position in the Medical Chemistry program at the College of Pharmacy and at the School of Dentistry around the time the building was being constructed. Drach said he was not sure if he would get a teaching job at the School of Dentistry because he didn’t have a dental degree. “I was a pharmacist and from my experiences working in drug stores, I realized dentists needed more education in pharmacology and therapeutics. Teaching those subjects to dental students seemed like a good idea,” he said. Mann hired Drach to teach pharmacology, and U-M dental students benefited from his expertise from 1970 to 2007. During his tenure at the school, he chaired the Department of Oral Biology from 1985 to 1987 and chaired the Department of Biologic and Materials Sciences from 1987 to 2005.

“Dean Mann always had the interests of the dental school in mind. He was strict, but fair and true to his word. The school did well under his leadership,” Drach said.

Mann retired on July 1, 1981, as dean of the School of Dentistry and director of the W.K. Kellogg Foundation Institute: Graduate and Postgraduate Dentistry. He served on the school’s faculty for 41 years and as its dean for 19 years. The school’s Alumni News noted in its fall edition, “His vision and administrative skills made possible far-reaching changes which resulted in the school being named first among dental schools in the country for its outstanding faculty, facilities and education.”