The University of Michigan School of Dentistry - Victors for Dentistry (1962–2017): Decades of Innovation and Discovery

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chapter 6. The Kotowicz Years (1995–2003)

With Dr. J. Bernard Machen’s temporary assignment and new responsibilities in the Fleming building, Bill Kotowicz, once tapped for special service, was this time appointed as interim dean. As senior associate dean, Kotowicz was closely connected to all of the programs and initiatives going on in the school. He was in an excellent position to advance the mission and goals of the school.

Competition for Spots

The school continued to experience growth in the size and quality of its first-year applicant pool. Competition among prospective first-year dental students became more intense. The number of applications submitted to the school by prospective dental students was on the rise and by 1997 totaled 1,621 (i.e., 16.2 applications for each of the 100 places in the class).

The New Model for Clinical Education

A key component of the new curriculum proposed by the Transition Committee and the Curriculum Task Force was the emphasis on clinical education for students and comprehensive, patient-centered oral health care for patients. The objectives of this holistic approach were to make dental education more effective and efficient as well as to improve patient care.[1]

Following the school’s accreditation review in 1995, a Futures Committee was established to develop a plan whose cornerstone remained comprehensive care. The committee emphasized the need to get dental students into clinics earlier than their third or fourth year of dental school. Other key recommendations of the Futures Committee included expanding the comprehensive care approach to all four years of a dental student’s clinical experience, having all dental hygiene students in the same clinics as dental students, and updating the curriculum so classroom instruction paralleled clinical experiences.[1]

This patient-centered approach to dental education was introduced as a pilot program and its success led to a major conference being held in Ann Arbor in November 1996. Representatives from dental schools, medical centers, insurance companies, organized dentistry, and the private sector met to discuss the challenges of implementing the new patient-centered curriculum. Favorable responses during the conference led to the decision to formally adopt this model and the launch of the Vertically Integrated Clinics (VICs) program the following June.[2]

Vertically Integrated Clinics

The introduction of the VICs, as they were often called, was one of the biggest changes that occurred in the curriculum and patient care during the late 1990s. The VICs represented a sharp departure from previous models of dental education.

The VICs were a composite of several dynamics. “Vertical” represented a student’s “moving up” through the dental program from the first through fourth years and from the second through fourth years for dental hygiene students. Each year introduced activities of greater complexity with the expectation of increased levels of competence and the ability to take on more responsibility. The change was significant for dental hygiene students. Previously, they saw patients in a clinic separate from dental students and were only in clinic three mornings a week—Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. The VIC model allowed the dental hygiene students to participate in clinical activities five days a week and dental hygiene patients were seen in both morning and afternoon sessions.

The word “integrated” involved a team approach that offered a special package of patient-centered comprehensive care to each and every patient seen at the dental school. Dental and dental hygiene students benefited from this approach, as the learning environment was designed to more closely resemble the private-practice setting. Patients benefited because under the new model, care was based on their individual needs and delivered through treatment plans developed jointly by students, patients, and faculty.

Another advantage of the VIC model was that first-year dental students now had early access to the clinics. They actually could see what was going on in clinic from the day they entered dental school. Although first-year dental students did not treat patients, they were able to assist upperclassmen and learn the ins and outs of working in a dental environment that included clinical care, patient interactions, infection control, and record-keeping. First-year dental hygiene students, who started their dental school experience as sophomores, followed a similar path. While they spent time developing their skills in preclinic, they also spent time in clinic where they observed junior and senior students providing care and were able to perform simple procedures such as polishing or topical fluoride applications.

These early experiences were valuable because by the time the students began to treat their own patients, both dental and dental hygiene students knew a lot about clinical procedures, patient communications, and the importance of teamwork.

First-year dental students (D1s) were assigned to one of four comprehensive care clinics located on the second and third floors of the dental building. The clinics, named for the color of the dental chairs in each clinic—2 Blue, 2 Green, 3 Blue, and 3 Green—became the “clinical home” for each student throughout all four years of dental school. Clinical faculty members were assigned to the same clinic each year and thus could better assess the clinical progress of the students in their clinic. Care provided in the VICs included restorative/operative, prosthodontic, and periodontal procedures. Students participated in scheduled rotations to get experience in orthodontics, pediatric, and oral surgery.[3]

Technology’s Growing Importance in Education and Patient Care

Dental and dental hygiene education was being enhanced with more information being offered in a new way—on the Internet. Recognizing the importance of strong information management skills for future health-care professionals, coursework was designed to actively engage students in the use of MEDLINE and other Internet searches, and to teleconference to work with faculty members and peers at other sites. A computer server was set up to house content that allowed students to access course syllabi, notes, and selected readings from school or home, as well as retrieve photos, charts, and radiographs for use in treatment planning exercises.[5] In 1996, the school announced the launch of its website, making access to School of Dentistry information for anyone interested just a few keystrokes away. Initially, the website content focused on material for students, prospective students, and those interested in continuing education offerings. Later, content was expanded to include general information about the school, department news, and alumni and development events.[6]

The growth of the Internet was extraordinary, with tens of thousands of people visiting the School of Dentistry website each month. In 1996, the National Library of Medicine funded a three-year project, led by Paul Lang, to assess the use of the Internet as a method of providing distance learning to dentists. Study participants were solicited from Michigan and throughout the United States. The school also offered its first completely online course. Ten fourth-year dental students participated in Information Management Issues for Dentistry 815 as a pilot program to determine whether a dental school course could be taught successfully online rather than as a standard series of lectures.[7] The results from this course and others that followed paved the way for the launch of the dental hygiene program’s degree completion e-learning program in 2008. The program was the first online degree completion program offered by the University of Michigan (U-M) Ann Arbor campus.[8]

Renovations and Facilities Enhancement

Significant renovations and improvements to existing physical facilities began, with major renovations to the Kellogg Building in 1997. Renovations were completed in 2000 at a cost of nearly $13 million, just in time for the celebration of school’s the 125th anniversary.

Dean William Kotowicz (L) and Assistant Dean Arnold Morowa with Gary Owens (R) outside the Kellogg Building before the renovation project begins.

Dean William Kotowicz (L) and Assistant Dean Arnold Morowa (R) confer with Gary Owens on the construction plans.

Dean William Kotowicz (L) and Assistant Dean Arnold Morowa with Gary Owens (R) scan construction details during the Kellogg Building renovation project.

A ceremony held in the new Sindecuse Atrium on September 8, 2000, celebrated the end of the Kellogg renovations, the naming of three new clinic areas for three distinguished alumni, the dedication of the new Sindecuse Atrium, and the 125th anniversary of the school’s founding. Among those attending were U-M President Lee Bollinger and Provost Nancy Cantor.

Three Facilities for Three Distinguished Alumni

The three clinical facilities that were part of the Kellogg renovation were the Robert W. Browne Orthodontic Wing, the Kenneth A. Easlick Pediatric Dentistry Clinic, and the Samuel D. Harris Children’s Dental Unit.

Robert W. Browne (DDS 1952, MS Orthodontics 1959) gifted $1.5 million to the school for a new orthodontic clinic that, as he described, “probably has not been altered since I was a student.”[9] A similar sentiment was voiced by Dr. James McNamara who was put in charge of renovations to the orthodontic clinic by Dr. Lysle Johnston, department chair. “The facilities we had been using were antiquated, at best,” McNamara said. “The renovations were sorely needed.” New orthodontic facilities included a patient waiting room, 34 dental chairs in an open clinic setting, complete radiographic facilities, new offices, and conference rooms.

Kenneth A. Easlick (DDS 1928), considered by many to be the father of pediatric dentistry, developed the school’s first teaching program in childrens dentistry shortly after he earned his dental degree from Michigan in 1928. The pediatric dentistry clinic named for him included 22 chairs in a semi-open clinic setting for graduate student training, two quiet rooms for children with special needs, a graduate studies seminar room, and clinical outcomes research facilities.[10][11]

Samuel D. Harris (DDS 1924), known as the founder of the American Society of Dentistry for Children, dedicated his career to encouraging all segments of the dental profession—teachers, clinicians, general, pediatric, and public health dentists—to promote better dental health for all children. The children’s dental unit included 10 dental chairs for predoctoral student training, an updated instrument handling area, and a parent/patient consultation room.[12][13]

A surprising discovery was made during the Kellogg Building renovations. The “Babe the Blue Ox” mural painted by Mr. Francis Danovich in the 1930s was found after it had been covered by wallpaper during the 1960s and forgotten. The mural was discovered as demolition was about to begin to make room for the Robert W. Browne Orthodontics Wing.

From Courtyard to Atrium

Also included in the Kellogg project were updates to the Gordon H. Sindecuse Museum of Dentistry and enclosing the adjacent open-air courtyard. Renovation of the Sindecuse Museum, which opened in 1992, featured more space for storage and exhibitions and climate controlled areas to help preserve dental equipment, photographs, and other memorabilia.[15] The new Sindecuse Atrium featured a glass roof covering the courtyard that now, protected from the elements, served as both exhibit space for the museum and event space for the school. The atrium can accommodate more than 200 people for luncheons and other special events, including those held during Homecoming Weekend.

Other renovations followed in 1998. Improvements were made to the student forum, officially named the Alpha Omega Fraternity Detroit Alumni Student Forum following a $50,000 gift to the school to support the project. Two new lecture rooms were built, one with 94 seats (G550) and the other with 36 seats (G580) were equipped with outlets that allowed students and faculty to connect their portable computers to the Internet. Elevated walkways offered access to the Kellogg Building from the first and second floors of the dental school building. Renovations also included clinics for endodontics, periodontics, and restorative dentistry, as well as restrooms that complied with the Americans with Disabilities Act, and enhancements to sterilization, dispensing, and records facilities. These costs, added to the $13 million spent on the Kellogg renovations, brought the construction costs for all projects to more than $20 million.[16]

Research Renaissance

Changes were underway in the school’s research activities. When he became dean, Kotowicz began to bolster the school-wide Oral Health Sciences (OHS)/PhD program. Citing the school’s strong reputation for its master’s and clinical programs, Kotowicz said the school did not have a well-defined, school-wide research and training program at the doctoral level, and he made that a priority. Dr. Charlotte Mistretta was asked to take on this challenge and her efforts helped to redefine the OHS/PhD program.

The OHS/PhD program was designed to strengthen basic, translational, clinical and health services research initiatives.

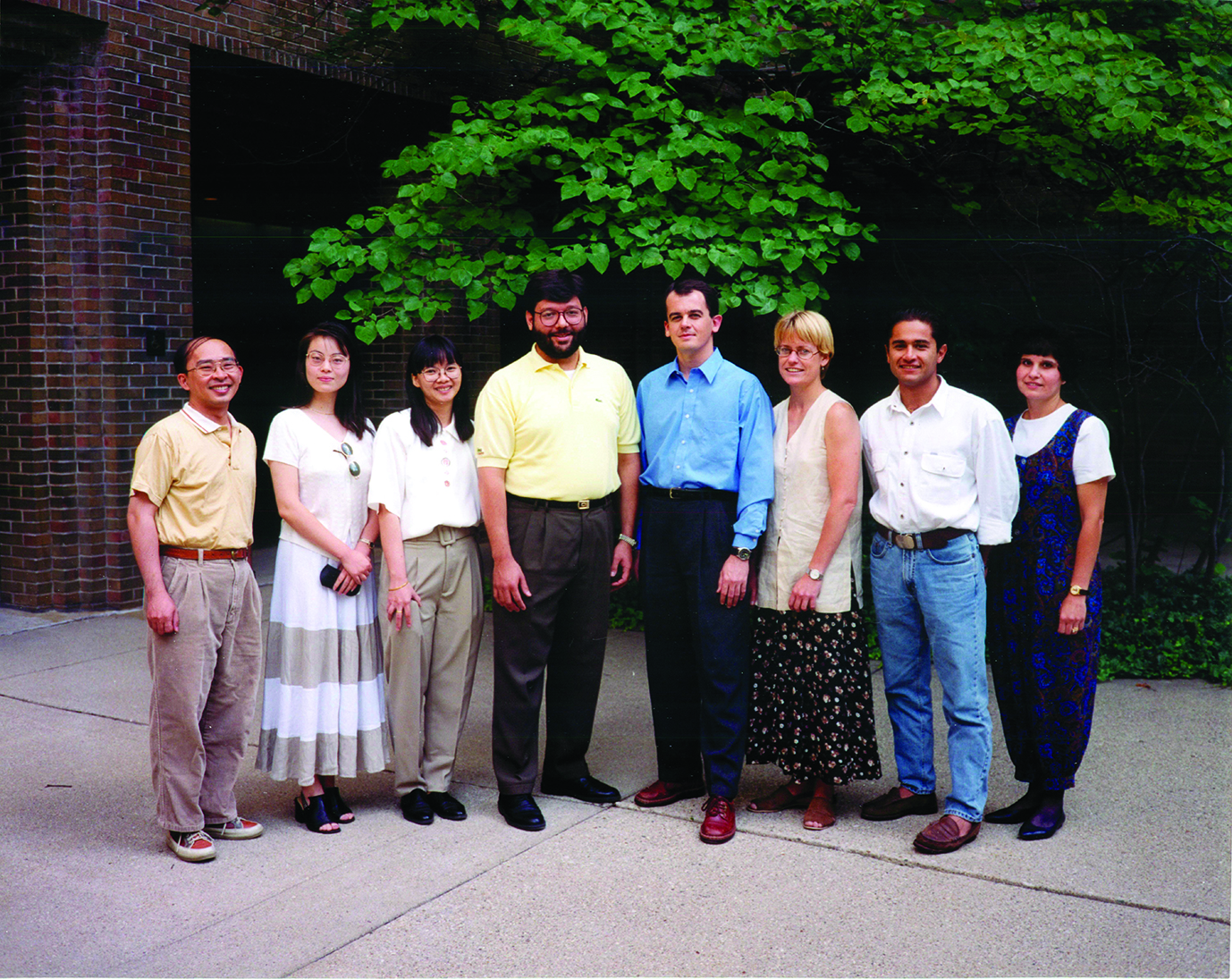

The fundamental goal of the program was to train exceptional students to become leaders in academic research, oral health maintenance, and disease prevention. Students were able to explore an array of biological, chemical, and physical aspects of oral health problems in six broad areas of study–craniofacial development and anomalies, tissue engineering and regeneration, microbial diseases and immunity, mineralized tissue and musculoskeletal disorders, oral neuroscience, and oral and pharyngeal cancer.[17] The first PhD degrees in OHS were conferred in 1999 to Jacques Nör and Esam Tashkandi.

Among the initial Oral Health Sciences/PhD cohort were (L–R) Hen-Li Chen (2002, dual degree MS and PhD student), Hongjiao Ouyang (2000), Somjin Ratanasathien (2000), Esam Tashkandi (1999), Jacques Nör (1999), Erika DeBoever (2001), Andre Haerian (2003), and Domenica Sweier (2004). Year of graduation is noted in parentheses.

OHS/PhD—Three Options

The OHS/PhD program offered students three program options to help them achieve their goals. The first option available to those aspiring to a career in dental research was the original OHS/PhD program. A second option combined a clinical master’s degree in a dental specialty while simultaneously pursuing the OHS/PhD. The third option was available to students whose goal it was to combine a DDS degree with a PhD in oral health research.

Mistretta said:

Students who have completed this program have progressed to careers in research and academic dentistry. . . . Their success, in turn, is attracting other exceptional and highly-motivated students who want to “push themselves” to achieve even more, both professionally and personally.[18]

Kotowicz said the program has succeeded “because of Charlotte’s ability to see the big picture and her ability to bring people together to achieve an objective.”[19]

Wanting to broaden the school’s research portfolio and secure more federal funding for research, Kotowicz named Dr. Christian Stohler as the school’s research director in 1995.[20] Building on the success of Dr. Sigurd Ramfjord’s research, faculty in the Department of Periodontics, Prevention and Geriatrics focused on reducing periodontal disease, regenerating and repairing oral hard and soft tissues, and applying discoveries in the basic sciences to help patients.[21]

Research in the Department of Oral Medicine, Pathology and Oncology focused on angiogenesis (the growth of blood vessels) and its relationship to cancer and other diseases. Faculty members in Cariology, Restorative Sciences and Endodontics began to put their efforts into clinical research studying dental materials and why restorations fail and participating in controlled clinical trials in private practice as well as health services research. These studies moved the department into another research arena with huge implications for dental practice and evidence-based dentistry.[22]

“Translating” discoveries in research laboratories that could be used in dental clinics was the focus of a one-year grant to establish the Center for the Biorestoration of Oral Health (CBOH) in 1996. CBOH director Dr. Laurie McCauley said it was the new frontier for the school’s research because it brought together dental, medical, biomedical, engineering, and other researchers to develop novel therapies that could improve the health and quality of life for patients with oral, dental, craniofacial, and other disorders. The center’s focus was on regeneration biology and work in this area helped as a catalyst to bring many scientists together to collaborate and foster stronger projects in regenerative medicine and tissue engineering.[23]

The focus on translational research was further promoted when Dr. Renny Franceschi was appointed director of research in 1998. He encouraged clinical research with the ultimate goal of moving basic findings into the clinic to promote health.

Scientific Frontiers in Clinical Dentistry

National Institute of Dental and Craniofacial Research (NIDCR) made history when, for the first time ever, it brought its Scientific Frontiers in Clinical Dentistry program to a college campus. On January 5 and 6, 2000, the U-M School of Dentistry hosted this prestigious program. Dr. Arnold Morawa, assistant dean for Alumni Relations and Continuing Dental Education, proposed the idea for the Michigan program in 1997 to Dr. Harold Slavkin, NIDCR director. “We planned to develop a program with a clinical focus,” Morawa said. “Our objective was to give those who attended an opportunity to hear about laboratory research and show how science could be applied to clinical practice.”[24]

More than 1,500 dental professionals from across the country came to Ann Arbor to listen to world-renowned clinicians and researchers discuss advances in dentistry and clinical research, and learn how this research benefits both practitioners and patients. U-M President Lee Bollinger delivered the opening remarks and outlined the university’s new $200 million Life Sciences Initiative that called for building a state-of-the-art facility that would foster greater interdisciplinary collaboration in the life sciences and reposition the university as a leader in health and life sciences research and education.[25] By all measures, the program was a tremendous success and underscored a long-standing commitment Michigan had made to dentistry and dental science decades earlier.

More than 1,500 people from across the country participated in the Scientific Frontiers in Clinical Dentistry program hosted by the School of Dentistry.

Dr. Martha Somerman, who became associate dean for research in January 2001, said that at Michigan, research was essential. “There was always a commitment to education among the faculty to graduate the best practitioners possible. Research and knowledge gained from research guided the development of our education programs which focused on evidence-based scientific approaches to inform practice decisions,” she said.

Funding the Research Enterprise

Funding for the research enterprise grew. Per the data provided by the school’s Office of Research and Research Training (Pat Schultz, personal communication, February 17, 2014) in 1997, the NIDCR awarded $4.9 million to the School of Dentistry. It increased to more than $8.5 million by the time Kotowicz’s term as dean ended in 2003.

With Success Comes Challenges

As the research enterprise grew, the need for additional space also grew. Research space in the dental school building was at capacity and beyond. The only option was to move some of its operations to off-campus sites. In 2002, several research activities were moved to the Eisenhower Commerce Center on the south side of Ann Arbor. Clinical billing and financial operations moved to the Arbor Lakes Commerce Center on Plymouth Road just outside Ann Arbor’s northeast side.

Outreach Expands

For many years, dental students provided oral health care to children during the Summer Migrant Dental Clinic program in the Traverse City area or at the Bay Cliff Health Camp northwest of Marquette. Pediatric residents also applied their knowledge and skills helping children in the Flint, Michigan, area. In July 1993, pediatric dental residents began providing oral health care as part of a relationship that involved the School of Dentistry’s Mott Children’s Health Center and Hurley Hospital.[26]

Dr. Jed Jacobson was named assistant dean for community and outreach programs in 1997. Not long after taking on this responsibility, Dean Kotowicz approached Jacobson and said, “I need you to take on a new responsibility.” Jacobson recalls:

Bill said he wanted to re-examine the school’s model of education so that it would include having students provide dental care in communities across Michigan for some part of the academic year. That was a tall order. Bob Bagramian and Marilyn Woolfolk did a wonderful job with outreach in the Traverse City area, but there was little, if any, funding for a larger effort that would include other communities across the state. (Personal Communication, July 23,2015)

Jacobson went straight to work to expand the program. The effort gained traction following meetings Jacobson had with Rick Bossard, government relations officer for the U-M Health System, and State Senator Joe Schwarz of Battle Creek. Public and private sector organizations collaborated to make the expanded outreach program a reality. They included the Michigan Department of Community Health, the Michigan Dental Association, the Delta Dental Fund (the philanthropic arm of Delta Dental), the Michigan Primary Care Association, the Michigan Campus Compact, the Josiah Macy Jr. Foundation, and the W.K. Kellogg Foundation’s Civic Engagement Program.[27]

Although the Summer Migrant Dental Clinic program was nearly two decades old when she arrived at the School of Dentistry in July 1992 to become associate dean for Academic Affairs, Dr. Lisa Tedesco said that the program helped both the school and the university. “It was important because it elevated the school’s visibility to Michigan citizens and was a model for other outreach efforts,” she said.

In early 2000, under Jacobson’s leadership and direction, the community outreach program emerged as a “year round” component of the dental education curriculum. Instead of taking place just in the summer, as it had for years, dental and dental hygiene students were now involved in community dentistry during the entire academic year (late summer to early spring of the following year) during their final year.

Dental students traveled to sites and worked alongside other oral health professionals in new locations—Grand Rapids, Battle Creek, Saginaw, Muskegon Heights, and Marquette. Dental students completed one-week rotations in three communities for a total of three weeks. Dental hygiene students participated in a single-week rotation. Residents in specialty oral health-care programs and those in the Advanced Education in General Dentistry program were also involved.[28]

The enhanced program benefited students, providers, and patients in the five communities. Students often treated patients with conditions not typically seen in the dental school’s on-campus clinics. The program allowed the students to live in communities throughout the state which improved the profile of U-M in those communities. Students also gained important insight into the communities they served. By working and living in the communities, students also gained a better understanding of problems in those areas. The arrangement also allowed local oral health-care providers to have more patients treated at their facilities. Patients, many who had not received oral health care in years, now received the care they needed.

Teaching with Technology

The school was being recognized for the innovative ways it was using new technology. In 2000, its Comprehensive Treating Planning website became a part of the Smithsonian’s Permanent Research Collection on Information Technology housed at the National Museum of American History. The site, created by Drs. Dennis Fasbinder and Jeffery Shotwell, was the first of its kind at the school to use a “virtual patient,” instead of 35-mm slides, to teach dental students about the benefits of various oral health-care treatments.[29]

Drs. Jeffery Shotwell (L) and Dennis Fasbinder at the Computerworld Awards presentation ceremony held October 5, 2000.

A year later, the school received the Computerworld Smithsonian Award that acknowledged developing novel uses of technology that benefit society. The school’s winning entry, in the Education and Academic category, was an interactive movie designed to teach head and neck anatomy to dental and medical students. The head and neck anatomy movie was developed by Dr. John Lillie.[30]

By 2000, the school began digitizing images of microscopic sections of oral lesions. The project was an effort to make the images available for teaching and learning on the school’s intranet, accessed by faculty, staff, and students by a special password. More than 10,000 slides were digitized and were available to help pathologists and clinicians in diagnosis, teaching, and collaboration. Digital technology continued to advance as orthodontics became the first department to move to an all-electronic, paperless clinical operation.

A New Tradition

The White Coat Ceremony initiated a “new tradition” for the school. The first ceremony was held in the fall of 2002 and each of 105 first-year dental students was welcomed to the school and the dental profession. Each student was called by name to formally receive the white coat that they would wear during their dental education.

Commitment to a Positive Workplace

The school’s administrators were committed to insuring that the School of Dentistry was a welcoming and safe place for faculty, staff, students and patients to interact, learn, work, and be treated in a supportive manner. During the 1995 academic year, the school conducted its first multicultural audit to assess the climate for diversity and inclusion in the dental school. One of the recommendations in the audit’s final report was to create a special committee, responsible for activities designed to promote change and monitor the progress made toward improving the multicultural climate in the school. The committee would be an advisory committee to the dean and provide annual progress reports.

To that end, Kotowicz formed the Multicultural Affairs Committee (MAC), made up of students, staff and faculty, charged with developing activities to advance excellence through diversity by exploring and celebrating differences and similarities among all groups. Led by Lisa Tedesco, associate dean for Academic Affairs, Cheryl Quiney, patient care coordinator, Patient Services, and Marita Inglehart, associate professor, Department of Periodontics and Oral Medicine, the MAC became the catalyst for change, cultivating a humanistic and collaborative environment that readily aligned with the school’s strategic initiatives.

Reflections

The Kotowicz years were years of change and transformation at the School of Dentistry. The “transition period” initiated a major reorganization effort reducing 18 academic departments to 6. Overall operations were decentralized; budget challenges were addressed; and cost centers were established for the programs. Academic and administrative collaborations were promoted and resource allocations were rethought. These strategies became a model for other schools and colleges at the U-M. Equally important was that the School of Dentistry no longer was isolated from the greater campus. It was now considered an integral part of the U-M. The success of these administrative and curricular changes were watched closely by dental schools around the country and became a standard to which others aspired.[31]