Not Just Any Department of Family Medicine: Telling the Story of the First Forty Years of the University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

7. 2017 and Beyond

Summary and Lessons Learned along the Way

As with many things, retrospection offers one the opportunity to examine the past, providing greater clarity to the present. When looking over the past forty years of family medicine at the University of Michigan, it is easy to see how certain things that were true in 1978 have continued to be so in 1988, 1998, 2008, and 2017 and likely will continue for many decades to come. The planning priorities from the July 1978 document mentioned in chapter 2 are still applicable in October 2017. In a similar fashion, some of the comments made by Dr. Davies and others early in the history of the department have turned out to be accurate in forecasting the potential for doing work this important in a place as prestigious as the University of Michigan.

As a reminder, here are the July 1978 planning priorities:

- Stabilize and develop patient-care at the Family Practice Center for further equipping, renovating and extending of present facilities. Resolve those identified problems which are present within the Family Practice Center. Work on community relations and patient education concerning Family Practice.

- Complete an Affiliation Agreement with the Chelsea Community Hospital.

- Complete a curriculum proposal for the Family Practice Residency Program in collaboration with all major departments in the Medical College.

- Seek further funding (Kellogg Foundation, HEW, etc.) for special program development.

- Recruit needed faculty.

- Identify and develop teaching input into the undergraduate curriculum (including individual student needs, electives and “core” curricula).

- Further develop research goals and protocols and prioritize research ambitions.

- Continue and develop collaborative efforts for Continuing Medical Education for Family Physicians.

- Plan a sequence of faculty development exercises.[1]

While some of these specific items are not as important or relevant as others in 2017, most of the activities and mission areas included on the list are still highly important and relevant now and will continue to be so moving forward.

In looking back across the past thirty-nine years plus of accomplishments and contributors, many key moments and themes emerged. Many of the things that intrigued Dr. Davies about the possibilities of potential greatness associated with tackling the task of starting an academic family medicine department in a highly subspecialized environment have proven to be similar for Drs. Schwenk and Zazove in subsequent eras. Likewise, some of the challenges encountered by Dr. Davies did not suddenly disappear for the next two chairs and are not likely to disappear for future chairs.

The value of being perseverant and the ability to respond to opportunities as they arise have been common themes across the entire life span of the department. The importance of supportive leadership and peers is equally relevant. In more recent years, the key role of donors has emerged as a large component of the success of the department that was not conceivable in the earliest days, but the department’s focus on trust, respect, competence, and achievement laid the foundation for this key role from day one. People in higher levels of authority at the University of Michigan might not always fully understand what family physicians can do in their roles as academic clinicians, educators, and researchers, but it is hard to disregard the level of accomplishment illustrated by department rankings as determined by the NIH, USNWR, and student ratings of required clerkships.

The University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS) has proven to be both a challenging and a fertile environment for the Department of Family Medicine. Before there was a department, there were large numbers of UMMS graduates choosing to go into family practice residency programs around the state and nation. The fact that many of them were leaving the state for residency training and practice was part of the impetus for the state legislature and the Michigan Academy of Family Physicians (MAFP) to lobby for academic departments and residency programs to be established at the three allopathic medical schools at the University of Michigan, Michigan State University (MSU), and Wayne State University in the 1970s. Considering the leadership roles played by UMMS graduates after the department was established in 1978, it is clear why “leaders” is a key word in the school fight song.

Before there was a chance to do postgraduate work in family medicine at the University of Michigan, many future department chairs, residency directors, and leaders of health care systems and family medicine graduated from UMMS and went elsewhere to do rotating internships, general practice residency, or family practice residency training. Among the many future leaders who graduated from medical school in Ann Arbor, one key graduate returned to town and became chair for twenty-five years, then became dean of a medical school in another state. Two of the chairs of the Department of Family Medicine at the MSU College of Human Medicine have been UMMS grads, as was a longtime chair at the Medical College of Ohio (now University of Toledo). A recent chair at the University of Virginia was a classmate of Dr. Schwenk in medical school. Someone a year behind Dr. Schwenk served as chair at several medical schools and as an associate dean and now serves as the president of a college in Detroit. There is most definitely something in the air or water in Ann Arbor that attracts people to come here as students, residents, fellows, and faculty. Whether they stay or move on, many of them do great things as leaders in many kinds of settings.

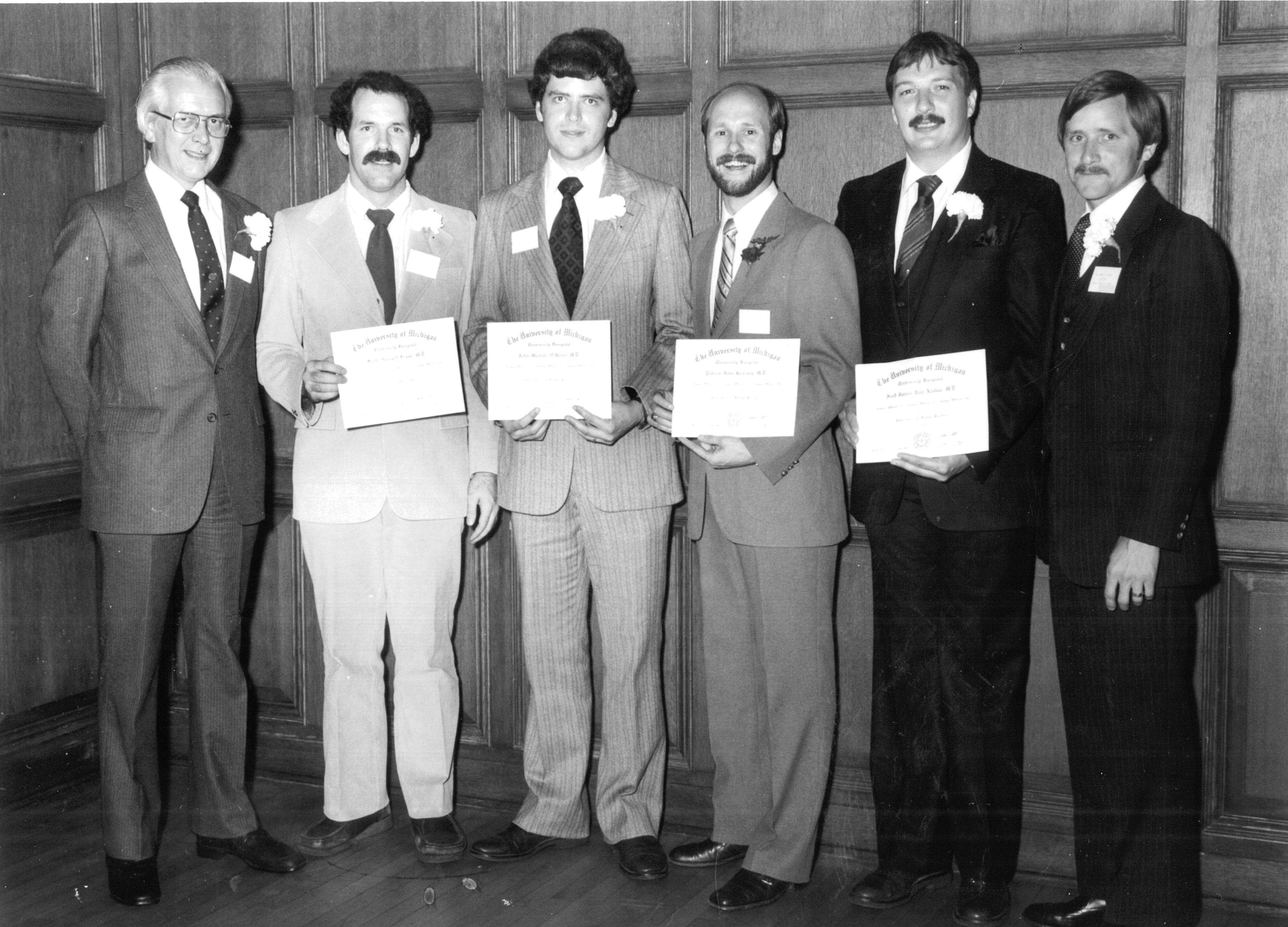

The careers of the first four graduates of the residency program foreshadow much of what was to come in terms of the outcomes of the graduates who would follow in their footsteps. Scott H. Frank, MD, MS, left the state in July 1982 and has not returned. He went to Case Western Reserve University in Cleveland to complete a Robert Wood Johnson Fellowship and complete his MS degree in family medicine. He has stayed at Case Western ever since in a variety of faculty roles, serving for eighteen years as the founding director of their MPH degree program. Recently, he shifted roles to become director of public health initiatives in the Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences. He also received fellowship training in addiction medicine along the way and served as a residency director and director of predoctoral education among his other faculty leadership roles.

Patrick J. Kearney, MD, also left the state in 1982 and has not returned, spending four years in the Indian Health Service in Shiprock, New Mexico, prior to taking a position in Durango, Colorado, where he continues to practice full-spectrum family medicine in the community setting. He is a past president of the medical staff at Mercy Regional Medical Center in Durango, and since 2011, he has been a member of the medical staff of Open Sky Wilderness Therapy.

John M. O’Brien, MD, never left the county, much less the state. He stayed on as faculty in the department and has been practicing in Chelsea since his first day as an intern in July 1979. He served as residency director for sixteen years and has worked in a range of other teaching and administrative capacities, including delivering hundreds of babies and caring for adolescent patients in middle schools and other settings in eastern Washtenaw County, along with his outpatient practice in Chelsea.

Fred J. Van Alstine, MD, MBA, also remained in the state for all of his clinical practice, leaving it temporarily to get additional specialized training beyond his family medicine residency experience. He started in community practice in Durand, Michigan, in 1982 and later moved to nearby Owosso. Dr. Van Alstine got his pilot’s license, enabling him to pursue educational programs out of state. He completed an MBA in Chicago and a hospice and palliative care fellowship in Atlanta. He also served as president of the Michigan Academy of Family Physicians in 2013–14. In July 2017, he moved to Gaylord, Michigan, and began to use his palliative care training for the Munson Healthcare System in Traverse City.

Graduation ceremony for the first class of residents in 1982. From left to right: Dr. Davies, Dr. Frank, Dr. O’Brien, Dr. Kearney, Dr. Van Alstine, and Dr. Peggs

Reunion of the first class of residents in 2014. From left to right: Dr. Davies, Dr. Frank, Dr. O’Brien, Dr. Kearney, Dr. Van Alstine, and Dr. Peggs

Across the diverse career paths of the four original graduates, one can see how the department and residency program have contributed to the care of patients in settings that span the scope of family medicine. Little did anyone know in June 1982 who or what was to become of this experiment in family medicine at the University of Michigan, but these four pioneers certainly used their education and training as medical students and family practice residents to go on paths that reflect the options that can be pursued by individuals who choose to enter family medicine at the University of Michigan.

In addition to the diverse career paths taken by the 289 residency graduates between 1982 and 2017, the diversity of the composition of the residents has changed dramatically, as has the diversity of the other components of the department community and the patient populations served by the department. The residents are more diverse than the faculty. The medical students are more diverse than the residents. And the patients are more diverse than the students.

Contrasting the four male UMMS-graduate interns who started residency in July 1979, the current thirty-three residents reflect diversity in ways that were inconceivable at the outset of the program. Male residents represent 36 percent of the current cohort of residents across classes, and only 15 percent of the current residents are UMMS graduates. There are graduates from twenty-three other medical schools in sixteen states and the District of Columbia among the cohort of thirty-three. There are current residents from two of the allopathic medical schools in the state of Michigan, and a graduate of the MSU College of Osteopathic Medicine was a member of the residency class of 2017, the most recent of many residents who had attended osteopathic medical schools.

Another theme that has become clear in reviewing the history of this department is that some things that happened were simply random or fortuitous. For example, in the interview conducted with Dr. Schwenk in Nevada in January 2016, he reflected upon how important the phone call he received from Dr. Reed indicating her decision to leave Utah and come to Ann Arbor was. At the time, however, it was not clear what direction her husband Dr. Zazove would take his career, such as whether he would pursue options in community practice or as a faculty member.[2] No one could have anticipated the important role he would play in the leadership of the Department of Family Medicine. During an interview in July 2017, Dr. Zazove gave this response when he was asked what he would tell his eventual successor:

- Four Suggestions/Lessons Learned

- 1. Never ever ever ever give up.

- 2. Focus on getting things done. Success begets success.

- 3. Rankings matter.

- 4. Be visible, be at the table.[3]

While the focus of written documents is on successes and accomplishments, major disappointments and setbacks linger in the memories of those who were present for them. The prolonged uncertainty during the time of the external review process of 1984–85 remains in the forefront of the memories of those who were in the department at that time. The loss of space negotiations and the lack of confidence in family medicine as a viable specialty or discipline are still burrs in the saddles of some longtime department members. Yet these struggles reinforce one of Dr. Zazove’s four pieces of advice: “Never ever ever ever give up.”

That principle was certainly established even before the department was created. The efforts of local family physicians, alumni, the MAFP, and other groups showed perseverance as they kept knocking on the door of the University of Michigan leadership to get the new specialty of family medicine established. And eventually, with pressure from the state legislature, the door was opened.

Symbolism has remained important in the history of this department. In the early phase, the department was almost entirely Chelsea-centric, for many understandable reasons, but eventually the department needed to move beyond that focus on Chelsea and become more integrated into the larger academic medical center for the department to survive.

The University of Michigan is often described as “a good place to be from.” In looking across the history of the University, this adage can be applied both before and after there was a formal Department of Family Medicine. While many future leaders of family practice or medicine went to UMMS long before the department was founded, the establishment of the department and the residency provided more leadership opportunities and brought in faculty, residents, and fellows who would develop into leaders during their time in Ann Arbor. Many of these leaders went on to spread their skills throughout the country. Dr. Davies was the first faculty member to go elsewhere to become chair. After several years on the faculty following completion of his term as chair in 1986, he moved to the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the Eastern Virginia School of Medicine, where he served as professor and chair from 1990 to 2002.

In addition to Dr. Schwenk, another faculty member hired by Dr. Davies went on to become a department chair elsewhere. Ricardo G. Hahn, MD, MS, was a resident at the Medical University of South Carolina (MUSC) when Dr. Davies was on faculty there, and he spent two years at the department in Ann Arbor before moving on to faculty appointments at other medical schools, the last of which was as professor and chair of the University of Southern California Department of Family Medicine. Dr. Hahn was in that position from 1995 to 2006.

More recently, three faculty members have left Ann Arbor to become chairs at other institutions. Lee A. Green, MD, MPH, was named as chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the University of Alberta in 2012. Mack T. Ruffin IV, MD, MPH, left to serve as chair of the Hershey Medical Center Department of Family and Community Medicine at Penn State University in 2016. Grant Greenberg, MD, MHSA, MA, was named chair of the Department of Family Medicine at the Lehigh Valley Health Network in Allentown, Pennsylvania, in 2016. Drs. Green and Greenberg were both graduates of UMMS and the residency program. All three of the faculty members who left had served as an assistant and/or associate chair of one of the key department mission areas.

Another tradition established early on that continues to this day is the celebration of successes. This began with the symposium the Family of Family Medicine, which was conducted in June 1982 in conjunction with the graduation of the first four residents. This tradition has continued with residency graduations and other milestones in the history of the department. More recently the student scholarships and award ceremony has grown in stature in a similar fashion. Starting in 2005 with a small ceremony during grand rounds, it has grown substantially as more scholarships and awards have been added. A luncheon for the scholarship and award honorees and their families was added in 2008. In 2011, a fellowship graduate luncheon was added to the lineup of celebrations.

The celebrations of the founding of the department began with a series of events marking the tenth anniversary in 1988, branded as a “Decade of Caring.” Subsequent celebrations have been held in 1998, 2004, 2008, and 2014. April 2018 will mark the fortieth year since the department’s founding in 1978 with another celebration.

While the University of Michigan is a “good place to be from” for students, residents, fellows, and faculty members, the department has imported many talented people from elsewhere to serve in key leadership positions. Throughout the history of the department, its continued growth and development have been fueled by recruiting, hiring, and retaining key faculty who had limited or no ties to Ann Arbor or the University prior to coming as residents or faculty. Later in the timeline, after the establishment of fellowships, fellows also became a new source of faculty and future leaders.

Two of the three chairs were trained exclusively elsewhere, and one left for nine years to complete his family medicine residency and initial community practice and faculty experience before returning in 1984 to become a part of the faculty. All three of the chairs came from places where family medicine was much more established as an academic specialty than it was in the state of Michigan, much less at the University of Michigan. While Dr. Davies came most immediately from the University of South Alabama, his initial academic time in the United States took place at the MUSC, a premier department that attracted residents from all over the country. Coincidentally, Joseph V. Fisher, MD—who had been in practice in Chelsea and was among the proposed directors for the Washtenaw County Family Practice Residency Program that failed to receive accreditation in the early 1970s—took a position as director of behavioral science at the MUSC program and knew Dr. Davies through that connection even before Dr. Davies came to Ann Arbor as the founding chair. Prior to his studies in the United States, Dr. Davies trained and worked in the United Kingdom and Jamaica within a socialized medicine system.

Dr. Schwenk and Dr. Zazove completed their residency training at the University of Utah. Both Dr. Zazove and his wife, Dr. Reed, matched at the University of Utah in the spring of 1978 as Dr. Schwenk was completing his residency at the same program and then starting in community practice in nearby Park City, Utah. While their times there did not overlap directly, they did become acquainted during the years they spent in Utah. When it came time for Dr. Schwenk to recruit Dr. Reed to Ann Arbor as part of his efforts to build up the department’s research program, their familiarity with each other and the similar training they had received in Salt Lake City worked to their mutual benefit. Much like MUSC, the Department of Family and Community Medicine at the University of Utah was among the top programs in family medicine at the time. It is interesting to consider what might have happened in March 1978 if Dr. Zazove and Dr. Reed had matched at their first option for residency training, Duke University in Durham, North Carolina, on the other side of the country from Salt Lake City! In this case, getting one’s second choice on the couple’s match list seems to have turned out well.

All three chairs came from situations and settings that had shown them the family medicine model would work. The challenge was getting the opportunity to try it in Ann Arbor. The foundation and concept of family medicine as an academic discipline was laid by Dr. Davies and then added to and further developed by Drs. Schwenk and Zazove. Those who were hired by Dr. Davies or were students, residents, or fellows during his term can sense that they are all part of a continuum. Similarly, those who entered the story of this department at later points in the timeline can feel their own connections to its development. During their tenures, these three chairs recruited people who advanced one or more department missions. Each recruited or mentored people who became leaders, scholars, innovators, or educators.

Another key moment in the maturation of the department was when then Dean Lichter suggested that it expand its development efforts. This fruitful suggestion ultimately led to an increase in scholarships and awards for medical students and residents, two endowed lectureships, and a named chair of family medicine. The incorporation of a development officer and associated activities into the department was another successful move. Compared to development officers at other medical schools, Amy C. St. Amour was fully integrated into the DFM. She had dedicated office space in the department and spent time learning about the specialty and the department’s people and programs. On average, in other departments, the length of tenure for someone in that role lasts less than two years, but here she has been the only person in that role since she began in 2003. Additionally, the timing of the hiring of a development officer coincided with a period of success, allowing her to promote the department among alumni—even ones who had been students before the DFM existed—who were now in a position to give back to their alma mater. Many of the people who were part of the initial lobbying to start the department were also able to donate. As is often the case, the department was able to capitalize on the fortunate timing of many factors. As identified in one of Dr. Zazove’s four key principles, “success begets success.” Over time, more donors have been identified and more scholarships, awards, and bequests have been secured, allowing this success to continue to snowball.

Setbacks and Challenges

Not everything has worked out as planned from day one. This fact seems very easy to appreciate at first glance, but documents, reports, and newsletters often leave out failures and disappointments. While the DFM has had few in comparison with its successes, some examples merit discussion at this time.

Several years ago, one of the chief residents was surprised to learn that years earlier in the department’s history, there had been a time when the residency had not filled all its spots through the Match. He was even more shocked when he was told there had been occasions when residents had been dismissed or encouraged to transfer to another program. Again, these are not the kinds of things that are highlighted in residency brochures or during the interview overview session when candidates are in the area for a day, but residents or faculty members who were present during those times would be able to quote examples without much prompting. In a similar fashion, there have been years when UMMS students who applied to family medicine did not match and had to be assisted in the “scramble” process.

The department, as an organization and community, had its share of times when it dealt with severe illnesses, surgeries, and deaths among faculty, residents, fellows, and staff members. These instances tested the resiliency of the collective department community, just as the physicians and others involved in clinical care must be sensitive to the losses among the patient populations served by the department. At the time of the 9/11 attacks, the department chose to hold its State of the Department Address (SODA) and faculty retreat the following day as originally scheduled, despite the fact that the University had canceled classes and other events. The gathering was very therapeutic on that critical day as everyone tried to process the events of the day before and what it would mean. This event was not a topic that showed up in an annual report or newsletter article, but nonetheless it was critical in the department history.

There were other losses or setbacks along the way where individual or community resilience was helpful in properly coping and moving on. Students failed the clerkship, residents failed rotations, and efforts to start new programs were not approved. Notable setbacks included the inability to establish an adolescent medicine fellowship and the failed effort to develop a joint family medicine residency with St. Joseph Mercy Hospital. Yet despite these momentary shortfalls, the department has continued to expand its involvement in the care of adolescent patients in the region. Even though the DFM was not able to expand the size of the residency by combining efforts with St. Joseph Mercy in the past, the entering class of interns will increase in number from eleven to thirteen as a result of other developments since that time. In both these cases, the initial efforts did not work out as planned, but in the long run, the ultimate goals were met through different channels. Just as small businesses must adjust to losses and setbacks, the department had to do likewise and keep moving forward.

Themes across Chairs

Two key areas that have not been specifically highlighted in previous chapters are faculty development and continuing medical education (CME). From the very beginning, both of these areas were high on the agenda dating back to the July 1978 planning priorities list created by Dr. Davies. Via a combination of resources, the three chairs were able to provide support for faculty to develop their baseline of knowledge and skills in areas related to patient care, teaching, administration, scholarly writing, and research. Over time, many of the people who participated in local or national faculty development programs were able to use those skills to teach other faculty or fellows through a “train the trainer” model. And because the department also had opportunities for faculty to both direct and teach in CME programs, there were other opportunities for them to apply the skills in ways beyond teaching students and residents.

The three chairs used some outstanding local, regional and national options for further education. The presence of an excellent School of Public Health (SPH) created opportunities for junior faculty with aspirations of academic careers to participate in what was then called the On-Job-On-Campus (OJOC) program, a series of intense educational coursework that could lead to a master’s degree in one of several departments within the SPH. Several of the first faculty to participate in OJOC went on to become leaders of the DFM’s research programs.

Along with OJOC, the department sponsored faculty to participate in the MSU Primary Care Faculty Development Fellowship Program. This program was less intense than OJOC and did not lead to a master’s degree, but it did require spending time in East Lansing, which took people away from patient care and teaching obligations for several weeks across the term of the fellowship. Another benefit of the MSU and OJOC programs was that participants came from around the country and from other medical specialties and health care professions. Both these programs exposed participants to faculty from other parts of the country and other disciplines, which often led to future research and educational collaborations.

As mentioned previously, the department was successful from early on in getting training grants funded by the Division of Medicine. An outcome of one of the funded training grants was the establishment of the University of Michigan Family Medicine Faculty Development Institute (FDI), which continues to this day in a condensed version of its original format. Dr. Sheets has served as the director of the FDI since it began in July 1994. The FDI requires less of a time commitment than the OJOC or the MSU programs but fills a niche in terms of providing at least thirty hours of teaching that is focused on core skills in classroom and clinical teaching, assessment of learners, curriculum development and management, and administrative skills.

Another program with a long tradition was established within the medical school with the advent of the Medical Education Scholars Program (MESP) in 1997. While the FDI was a series of whole-day sessions conducted off campus in a local hotel, the MESP was a series of thirty to thirty-six afternoon sessions conducted on campus, administered by another medical school department. A number of department faculty participated in the MESP, often after completing the FDI. Currently, the academic fellow also participates in the MESP. Similar to the MSU fellowship and OJOC program, MESP provides a chance for junior faculty and fellows to meet people from other departments in the medical school.

There was also a tradition established early on to support faculty who needed to go elsewhere to gain skills in procedural training or specific research training. Three prime examples involved sending faculty to get training in colposcopy, obstetrical ultrasonography, and evidence-based medicine.

There is some overlap between faculty development and CME. The major difference is that before the department existed, there were some CME courses run by the UMMS that were geared at general practitioners and family physicians. Eventually, the department took over leadership of these courses from a medical school department that had administered all CME courses. In addition to the traditional review course held in Ann Arbor, there were summer and winter CME programs, both held in northern Michigan at ski or golf resorts. Later, for a number of years, there was a procedures course held on campus and a women’s health course run in conjunction with the Department of Obstetrics and Gynecology and a Sports Medicine course. Over the years, some of the economics of conducting CME courses changed, and the department cut back on the number of course offerings. The DFM has gone through several models for administering these courses. Regardless of the model of administration or the focus of topics for these CME courses, they have continued to be favorably evaluated by participants and continue to be a core component of the department’s educational programs.

The department has had a unique experience working with members of the local Deaf and hard-of-hearing community thanks to Dr. Zazove. He has developed a strong following in the local area, particularly at his practice site in Dexter. He has published extensively in this area and given numerous grand rounds and medical student presentations, often while including patients and sign language interpreters.

Over time, each clinical site has developed ways in which it has been able to serve unique segments of the communities in which it is located. Early on in the development of the Chelsea practice, sports physicals for middle and high school students were offered as a service and a way to market the practice to the community. The practice sponsored fun runs and a booth at the Chelsea Community Fair. As additional practices were added, each found relevant ways to get incorporated into the communities it served.

The DFM has responded to opportunities to expand into different areas of clinical service over the years. One clinical service area that cut across sites and settings was sports medicine. For a period of several years, members of the department served as team doctors to high school football teams across Washtenaw County. Later, as the sports medicine fellowship developed ties at Eastern Michigan and the University of Michigan, faculty and fellows began serving in key roles in the care of women’s and men’s athletes at both institutions, a tradition that continues to date.

The DFM had an early connection to the Corner Health Center in Ypsilanti, which continues to serve adolescent patients in the area. In more recent years, the department has provided physician coverage within a collaborative effort across multiple middle schools and high schools in the region. While the adolescent fellowship was never established as hoped, the department’s role in caring for adolescent populations has been a strong interest that has endured.

Care of the medically underserved has been another recurrent focus of those in the department. Involvement in migrant clinics and other free clinics has been linked with student and resident education whenever possible.

Individual faculty members have pursued international experiences, sometimes on their own and sometimes through department-sponsored initiatives, most notably in Japan and Ghana. Faculty and learners of all levels have also come from these two countries in particular to spend time in the department.

Legends, Lore, and Legacy

Comments made by those involved in the story of this department are helpful for providing context to certain issues. One question that sometimes arises at national meetings is why the department was named the Department of Family Practice rather than Department of Family Medicine prior to 1997. Department lore provides the answer. Though unsubstantiated, it is claimed that someone with great influence in the school and health system said at the time of the establishment of the department: “As long as I am here, the only department of medicine at the University of Michigan will be the Department of Internal Medicine.” By the time of the second department review in 1996, when external consultants recommended that the department be renamed the Department of Family Medicine, it just so happened that the person who was reported to have made the comment in 1978 was no longer in Ann Arbor.

The previous anecdote regarding the name change of the department has a corollary. Others outside the department would sometimes shorten the name of the specialty to “family.” This quirk was first noticed when medical students were overheard talking about what rotation they were on or what specialty they were considering pursuing and they would say “family” instead of “family medicine.” And thus it became part of the nomenclature of the environment, just as “pediatrics” has long been shortened to “peds,” “orthopedic surgery” to “ortho,” and so on. The adoption of an abbreviated term of reference was another sign of the gradual acceptance and incorporation of family medicine into the culture of the University.

Another critical decision made by Dr. Davies in 1978 was to hire a PhD educator as the first faculty member rather than someone with a medical degree. Certainly this was out-of-the-box thinking at the time in Ann Arbor, and there was push back from others in the medical school administration at the thought of a clinical department hiring a faculty member with a PhD in higher education administration, but Dr. Davies persevered and hired the first of many faculty members without medical degrees who were to play major roles in the evolution in the department across all missions and functions. At the outset, student education, residency education, continuing medical education, faculty development, and department administration were the primary activities for Dr. Lefever and others with degrees outside medicine. Over time, the role of faculty and staff with other graduate degrees has become equally critical to the success of research and clinical programs. This practice eventually has come to be more prevalent in other areas of the medical center and clinical departments.

A number of stories contribute to the legends, lore, and legacy over the years. As described previously, the external review of 1984 lingered on for an inordinately long time, causing unsubstantiated rumors in the community about the department shutting down or being made into a division of the Department of Internal Medicine. One of the little known moments of that time occurred when the interim dean Peter A. Ward, MD, independently called two faculty members in to meet with him in his office. Dean Ward met with both Dr. O’Brien and Dr. Peggs independently and without their knowledge of his meeting with the other. During these meetings, both were assured that if the department was dissolved or made into a division of another department, their faculty positions and clinical practice would be maintained. At some point over the years, after the department had been maintained as a full department, the legend grew that one of the issues that came up in those independent meetings was that the University wanted to maintain a presence in Chelsea in order to help protect the western edge of the clinical enterprise from any excursions from the north and west by MSU. As the story was retold over the years, it became a myth that the medical center was worried about an incursion by “green and white hordes” of Spartans swooping down from the north and west. While this was clearly not the specific content of the conversation between the interim dean and two family physician faculty members, it is an example of how sometimes a kernel of truth can be expanded over time.

Inside the department, there has been a long tradition of referring to the “family of family medicine,” dating back to that first major symposium in June 1982. When there was a coed softball team started by the residents and continued by the faculty for several years in the mid to late 1980s, the team was officially listed in the softball league schedule as “Chelsea Family.” This led one coach of another team to ask one of the players if the rumor was true that the majority of the players were from a large family in Chelsea. Another time, when a player on a nearby softball diamond was injured sliding into a base in the era before omnipresent cell phones, someone came over to where Chelsea Family was playing and asked if it was true that some of the team members were doctors, and if so, could someone come look at the injured player before they called 911?

From the very beginning, the DFM was also a family in the sense that S. Margaret Davies, MD, was one of the first faculty members and developed her own role and visibility within the department and medical school beyond being married to the first chair. One way she got involved was by joining the Medical School Admissions Committee. In that role, she also became involved with the Galens Medical Society and subsequently served as an unofficial adviser to many students regardless of specialty interest. Being based off-site in Chelsea likely facilitated the chance that students would seek her out for guidance without working through official medical school channels.

This contact eventually led Dr. M. Davies to be portrayed by a medical student as the lead of the 1985 Galens Smoker, an annual student-run comedy performance. That year’s production of “Merry Poopins” included a scene where the character of Maggie Poopins descended from the ceiling of the Michigan Theater stage on a commode with an umbrella. Several members of the cast and crew not only followed Dr. M. Davies into the specialty of family medicine, but several have gone on into leadership roles of great importance in other specialties throughout the medical center.

Space and Setting Challenges

Another challenge shared by all the chairs has been securing and retaining appropriate space for clinical, administrative, educational, and research purposes. That challenge has played out time and time again since 1978 and will continue to be a critical issue as the department moves to new space yet again in the coming months. Along with space, a corresponding issue has been finding a way to make the department much less Chelsea-centric. Primary among the reasons for this has been the logistics of getting people together in person for grand rounds and other conferences and faculty meetings and resident conferences. As the department spread to the east from Chelsea into Ann Arbor and Ypsilanti, there was a need for more centralized space, especially as the department outgrew the available space in Chelsea. Space was rented off campus for a while at the Environmental Research Institute of Michigan (ERIM) before moving to the new East Ann Arbor Health Center when it opened on Plymouth Road in 1996. Following the move of the administrative offices to Women’s Hospital in 1999, the department shifted large group presentations and faculty meetings to Ford Auditorium in the University Hospital and resident conferences and other meetings to conference room space at Women’s. With the upcoming move to the 300 North Ingalls building, which will distance the administrative offices even more from the center of the medical center, new logistical challenges associated with convening for educational programs and meetings will need to be addressed.

In looking over various sources in compiling this department history, it becomes clear from a somewhat subjective perspective that this is a unique department in a special setting. While it would be presumptuous to conclude that it is one of a kind, that assessment might be not too far off the mark! One of the candidates for the most recent chair search made comments to the effect that he had been a faculty member in two settings at that point in his career in 2012. He had been a faculty member in a top-ten family medicine department at a less prestigious medical school and university, where the family medicine department was much higher rated than either the school or the institution. Then he moved to a very prestigious medical school where he was the founding chair in the same fashion as Dr. Davies in 1978. One reason for his interest in interviewing for the chair position in Ann Arbor was to explore what it was like in a top-ten family medicine department at a top-ten school and institution, in essence combining the characteristics of his previous and current positions. The sentiment that the University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine is unique in its success in such a competitive and challenging environment is shared throughout the community of academic family medicine. The challenge moving forward will be to keep the DFM in this lofty position among its peers.

It is important to try to identify what makes a department like this one special, or “Not Just Any Department of Family Medicine” functioning inside “Not Just Any Medical School.” As with any organization, success starts with the leadership, and the DFM has been blessed with visionary leaders from the outset. The initial support from local family physicians and state and national academies and the pressure from the Michigan State Legislature all led to the beginning of this adventure in March 1978. Along the way, the establishment of family medicine in such a research-oriented tertiary care setting has had its highs and lows, but when there were opportunities to succeed and supportive leadership, the department was able to “step up to the plate” and be successful. None of this would have been possible without the involvement of talented and committed people. In considering the traits of the people, programs, and services provided by this department since 1978, here are the characteristics that came to mind:

- Loyalty

- Productivity

- Competence

- Continuity

- Creativity

- Vision

- Compassion

- Planning

- Preparedness

- Adaptability

- Perseverance

The department has cared for tens of thousands of patients over the years. One patient wrote a letter dated September 8, 2017, which was read at the 2017 SODA by Elizabeth K. Jones, MD, the medical director at the Livonia Health Center where the patient received care. The sentiments are likely shared by patients from all of the department’s sites in reference to multiple faculty, fellows, residents, and staff since 1978.

I am writing to tell you how impressed I am, as a patient, with the level of care I have received at the Livonia Health Center.

I feel like the Livonia Health Center exemplifies the best not only in family medicine, but the best in Michigan health care. First, the support staff, the people who answer the phones, greet patients, and keep the office humming are the most professional I have met in my multiple visits to clinics within the U of M system. They are always polite to me, and to others, and seem to take care of each person who walks in as if that person were a member of their family. More so, they speak in quiet tones, maintain confidentiality, and really seem to do their best to make patients feel comfortable. The fact that these individuals are able to maintain a stable and professional demeanor is commendable.

Thank you for all the hard work at this clinic. I realize family medicine may not be the most glamorous of specialties, but I wanted you to know how much an exemplary family medicine clinic, with good staff and providers, can mean to one patient. So, thank you.[5]

In addition to the words of that patient, students have summed up why the department has been successful in its various mission areas for forty years. Vikas K. Jayadeva, recipient of the 2017 Paddy and Donald N. Fitch, MD, Scholarship and the 2016–17 Harold Kessler, MD, Family Medicine Scholarship, stated, “My decision to become a family physician comes from an understanding of the mechanisms of disease but even more so from dealing with the personal and social aspects of the ailment. To me, this means working across medical specialties to prevent illness, rather than reacting to it. It also means holistically addressing the health care inequalities that ignited my passion for medicine. But the most compelling aspects of family medicine for me are the longitudinal patient relationships that are developed, nurtured and maintained, forming the cornerstone of excellent patient management.”[6] Elizabeth M. Irish, recipient of the 2016 Michael Papo, MD, Scholarship, shared, “As someone who enjoys intellectual challenges, understanding people in their unique context, and working hard for those who place their trust in you, a career in family medicine is wholly encompassing for me. These principles, along with those that I will learn as I continue training, are not just valuable lessons learned from my medical education, but are the guiding principles that I will use in the care of my future patients and their loved ones as a family physician.”[7]

With testimonials from patients and students like these, the future continues to be bright for the University of Michigan Department of Family Medicine. Dr. Zazove summarized the 2016 Scholarship and Awards Event in this fashion: “It was so stimulating to see these scholarships being presented to the fourth-year students headed to family medicine residencies across the country. Hearing stories of the incredible accomplishments of these students as well as the background of the donors was inspiring. It is clear that family medicine will be in good hands with the next generation.”[8]

In reviewing documents and reports written across the last forty years, reading emails and letters, and listening to interviews with key historical figures, it was readily evident how important the “family of family medicine” has been in establishing this department from day one. This legacy has continued across the terms of three chairs, all of whom came from different places and backgrounds but found common themes, challenges, and successes in an environment that was not always fully supportive or appreciative of what they were trying to accomplish.

In his final column in a spring 2011 newsletter, Dr. Schwenk summarized the department’s accomplishments: “I believe we have created something truly special in Family Medicine at U-M. And I am not using the royal ‘we’ (as I sometimes do). I really mean ‘we.’ The Department’s growth and development has been more of a crusade than a job, a crusade that was fueled by the commitment and energy of every single member of the Department. We have established Family Medicine as a major contributor to and source of pride by the University of Michigan Health System, something many people said could not be done in our early years.”[9]

In the six years since Dr. Schwenk wrote that closing column after his twenty-five years of serving as chair, the department has continued to pursue that crusade under the leadership of Dr. Zazove. He has built upon the foundation established by Drs. Davies and Schwenk with the assistance of countless faculty colleagues, fellows, residents, students, staff members, and friends who have supported the department and its commitment to excellence across its mission areas of patient care, education, research, and service.

A cumulative timeline of key events and individuals in department history follows this closing chapter along with notes and sources used in documenting the accomplishments, stories, and anecdotes shared throughout this book. The appendices provide lists of key members of the “family of family medicine” at the University of Michigan dating back to March 1, 1978, as well as recognizing those individuals who have received awards or scholarships based on their academic, teaching, clinical, research, service, and scholarly accomplishments. Lastly, the friends and supporters of the department who have provided gifts and donations in support of programs, scholarships, and awards are acknowledged in grateful appreciation for their past, present, and future support.