Memoirs of a Black Psychiatrist, A Life of Advocacy for Social Change

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Chapter 3

Becoming a Psychiatrist My Way, 1946 – 1968

As the black population of Detroit became increasingly powerful financially and politically in the late 1940s, Wayne County General Hospital was forced to desegregate, and began admitting black post-graduate medical trainees and hiring black nurses and other health care professionals. Wayne County General was a 5,000-bed acute- and chronic-care hospital located just west of Detroit, one of the main teaching hospitals for Wayne State University, and a site where investigators from the University of Michigan also conducted clinical research. I was one of the first two black interns there when I began my year of general rotations in medical and surgical services after graduating from the University of Michigan Medical School in December 1946.

The other black intern had graduated from Meharry Medical College in Nashville, one of the country’s two black medical schools. His home town was Pontiac, Michigan, where his father practiced medicine; one of his uncles was an attorney who lived in Detroit and was treasurer of the Wayne County Democratic Party. Our year as interns passed without incident. All the staff members at all levels were white except for one newly hired black nurse on a medical ward. Blacks made up only two to three percent of the patient population, despite the large proportion of blacks in Detroit. There were no black physicians on staff, but there was one black internist on the visiting attending staff who came once a week, along with the prominent white physician who had arranged his appointment. It was through my developing friendship with that one visiting black physician that I was introduced to the large black physician community in Detroit.

I had become friends with several black medical students attending Wayne State when I was in college and medical school. One of them was Dr. Garnet Ice, who had been part of a group of Army doctors assigned to receive brief training in psychiatry before going overseas to serve the mental health care needs of the troops, much as the Army would have trained me in engineering. They did part of their training at Camp Upton in New York, where one of the instructors was Dr. Viola Bernard, the Columbia University faculty member who was working, along with several other American psychiatrists, to increase the number of blacks in the specialty. She thought Dr. Ice would be a good candidate, but he explained to her that his first interest was in surgery, not psychiatry. Dr. Bernard told him that if he encountered a young black physician who wanted to become a psychiatrist, she would like to meet him or her personally and help provide assistance in getting the necessary training.

So it was that Dr. Ice gave me Dr. Bernard’s name and address, and I met her in New York City in 1947, during my general internship at Wayne County General. She told me that Dr. Howard Potter, head of the psychiatry department at the Long Island College of Medicine (which was just about to become the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn), was recruiting blacks for his residency program there. That program was sponsored by the Veterans Administration; both Dr. Potter and Dr. William Menninger, the director of the Psychiatry Consultants Division in the U.S. Army’s Surgeon General’s office, were also members of that group of American psychiatrists eager to desegregate the field. Dr. Bernard also advised me that I should apply to the National Medical Fellowships, which was formed to bring more black physicians into academic medical careers, to finance the personal psychoanalysis required to enter that subspecialty. I applied to, and was accepted by both within weeks. Dr. Bernard also recommended that I apply to Columbia’s Psychoanalytic Clinic for Training and Research, so I could pursue some parts of my psychoanalytic training while completing my residency in general psychiatry. I had already completed the first few months of my psychiatry residency at Wayne County General and completed that year before transferring to the State University of New York residency training program.

The residency training program at Wayne County General was directed by Dr. Milton H. Erickson, one of the most creative American psychiatrists of the 20th century. He is known primarily for the application of hypnosis to the field of psychotherapy, and also made seminal contributions to the development of the short-term psychotherapy that has almost eclipsed the long-term treatment which was dominant in this country after World War II. Born into a farm family in Wisconsin, Erickson contracted polio at age 17. The disease almost killed him, and left him comatose for days, after which he was unable to talk or walk. However, through a remarkable feat of self-mastery, and what he later recognized as a self-induced hypnotic trance, he learned to walk again by going alone on a 1,000-mile canoe trip down the Mississippi River, with only $2.32 for food and other supplies. Despite his physical handicaps, his remarkable ability to negotiate with people along the way for food and physical help enabled him to complete the voyage successfully. He was able to walk with a cane by the time he returned, and went on to the University of Wisconsin, where he earned both a master’s degree in psychology and his MD in the same year. Only years later did I learn of these amazing experiences in his early years. He never spoke of them to me, nor did he ever ask me a single question about my own formative years. Against all prevailing dogma, he did not believe psychotherapy required any such information; even now his belief would almost seem heretical. Psychiatric training with him was very much like a psychotherapeutic experience.

The Wayne County residency in psychiatry was a three-year program that accepted only two applicants a year. The other first year resident in 1948 was one of my white U-M classmates. We barely knew each other, as he had been a member of the Navy V 12 group in medical school and those men lived in a fraternity house that had been turned over to them rather than in the medical school men’s dormitory. He had wanted to be a neurosurgeon but was not accepted into a training program and decided to go into psychiatry instead, much to the displeasure of his physician father, who was a surgeon in northern Michigan. We stayed on the same dormitory floor for psychiatry residents at Wayne County General and became close friends, partly due to a shared interest in classical music. One of his other hobbies was archery, and he tried to help me become proficient in that difficult sport. That never happened, but I was left with a lasting admiration of the intelligence and survival genius that enabled early mankind to survive by their hunting skills. I also enjoyed a friendship with the other black intern and we spent a lot of time learning to ride horseback at a nearby stable and riding school. This was another humbling learning experience. He often went to his parents’ home in Pontiac on weekends, and spent a lot of time alone in his room during the week as he was basically a shy person.

Dr. Erickson was pleased with my future plans for training in psychiatry and psychoanalysis and my interest in a career in academic medicine. While he was not a psychoanalyst, he had great respect for some of Freud’s contributions and had co-authored several papers with Dr. Lawrence Kubie, a leading psychoanalyst in New York City, who had referred several patients with intractable symptoms to work with Dr. Erickson. Erickson demonstrated how patients, while in a hypnotic trance, used all of the defense mechanisms described by Freud. Most of the attending psychiatrists at Wayne County General were either undergoing personal analysis or had completed it, but the Detroit Psychoanalytic Society, led by Dr. Richard Sterba, was known to be orthodox Freudian and unsympathetic to other views, which did not appeal to me.

Wayne County General’s psychiatric division, which was separate from the general medical and surgical acute and chronic services, was a good example of a large psychiatric hospital of its day. The acute care division of about a hundred beds took care of newly admitted psychotic patients; a much larger chronic care division provided custodial care to several thousand more. This psychiatric division was a self-sustaining therapeutic village in every way, with a large farm and grounds and numerous buildings, all maintained by patients who worked under the supervision of paid staff. These patients were not only employed without pay to work on the farm, but also in the power plant, laundry, kitchen, and post office. In addition, they worked in teams maintaining the grounds and roads, and constituted the housekeeping staff. Most psychiatric staff physicians and their families lived on the grounds in houses provided by hospital administration, and were provided with stabilized chronically ill patients to serve as maids, cooks, housekeepers and gardeners to meet their household needs.

Most of our residency training took place in the acute care units, where we were responsible for the initial medical and psychiatric workup of new patients and followed their treatment course thereafter. We learned the treatment modalities of the day: electro-convulsive therapy, insulin coma treatment, and malaria treatment for patients suffering from tertiary syphilis, of which there were many. Patients also received recreational and occupational therapy as well as music therapy, which was a special interest of one of the attending psychiatrists. Some of the patients were professionally trained musicians, who were joined by other musicians in the Detroit area for an annual symphonic performance attended by a large audience. Mrs. Mary Manly, the only black member of the psychiatric hospital’s professional staff, was chief of the music therapy program.

In the course of working up and following the patients’ general course, we residents interviewed family members and worked closely not only with nurses but also clinical psychologists and psychiatric social workers to arrive at our diagnosis and treatment plan. Dr. Erickson, who believed in bedside teaching, would accompany us on our daily rounds, along with the attending psychiatrist in charge of that unit. Outside lecturers came to the hospital once a week to teach the residents various developments in psychiatry, as well as psychology and sociology. Dr. Erickson also believed strongly in the interdisciplinary team. He chaired the weekly journal club, where staff members from these related fields presented articles from their own leading journals. Attendees at these meetings were all professionals: psychiatric staff physicians, residents in training, psychiatric nurses, psychologists, and social workers, as well as students doing field placements in all the supporting professional disciplines. It was at one of these meetings that I met my future wife, Vivian Rawls, who was one of the hospital’s first two black social work students, both from the University of Michigan School of Social Work, assigned to do their field work at Wayne County General.

Wherever possible, our training took place in the real world. Dr. Erickson arranged for residents to go to the Detroit Family Court one afternoon a week to do psychiatric evaluations of children coming before the Juvenile Court division for delinquent behavior, or who were being evaluated for removal from their homes because of parental abuse or neglect. And when he was called on for private evening consultations by psychiatrists in Detroit who wanted his help with patients showing little progress, he brought his residents with him to their offices to observe his work with patients directly. Discussions following these sessions became social events that nurtured warm feelings of friendship.

Dr. Erickson’s reading assignments for the residents were both unusual and mysterious. He asked us all to borrow the following books from the department’s library: The Golden Bough, by Sir James George Frazer, the classic comparative study of mythology and religion around the world; Barbary Coast, by Henry Asbury, a history of the breakdown of social and personal behavior norms during the California gold rush, and The Crowd, by Gustave Le Bon, a pioneering social psychological analysis of crowd and mob behavior. What made these reading assignments a mystery was that Erickson had absolutely nothing further to say about these books after assigning them to us. He never asked if we had read them, much less did we discuss what he or we thought about them. This was an example of Dr. Erickson’s therapeutic strategy; he was forcing us to make our own individual interpretation of how to handle the assignment. Each resident was left to deal with his private decision about how he chose to act. He had to decide for himself whether to read these assignments or not, or to wonder how he might discuss the subject matter at some future time. This taught us to accept personal responsibility for our choice to be an excellent, good, average, or below-average professional person without anybody checking up on us. In this way, we learned that in the privacy of our own thoughts we are not only tested but also grade ourselves.

After leaving Wayne County in 1968 to move to Phoenix, Dr. Erickson gained a worldwide reputation for his great and original genius, as both a teacher and therapist. He would often assign patients to climb a nearby mountain, and leave them to search on their own for the meaning of accomplishing that particular task, why he had given it to them, and its relevance to their illness. Hundreds, even thousands, of possible ideas would occur to patients, in the course of which their symptoms often would abate as mysteriously as they may have developed in the first place. This is teaching by metaphor.

Dr. Erickson resisted calls for him to develop a school of thought on human behavior, insisting that he be considered atheoretical. He believed that each person’s unconscious mind has individually created its own theory of why he behaves in his or her personal way and that his or her unconscious mind can find a better solution for the problem created than anyone else can, including the therapist, if presented with a therapeutic situational challenge. In his view, everyone goes in and out of various stages of trance throughout the day, and it isn’t necessary to induce a formal trance state for a patient to be a therapist for himself. Nor did he think it was necessary to explore a person’s life history, or to interpret his or her dreams or fantasies or memories of the past. The therapist’s task was to do whatever was necessary to create a situation in which the patient can find his own solution to his difficulty. Removal of symptoms was still the aim, but achieving it was not the therapist’s job. Erickson was also a great practical joker, who enjoyed using both metaphor and game playing as learning opportunities. He invited me to have dinner with him and his family on several occasions, and I vividly remember the first one, and my introduction to this tactic of his.

1. The Coin Toss Game

Erickson, one of his sons, and I were making small talk in his living room before dinner. He asked if I had any change in my pocket. I said yes, and held out my hand to show the coins. He asked me to hand the quarter to him, which I did, at which time he flipped it and covered it with his hand.

“Heads or tails?” he asked, to which I answered, “I would guess tails.”

“It’s heads,” he said, “I win.” He asked if I would hand him another coin and I gave him a nickel. As with the quarter, he flipped it, covered it, and asked if it were heads or tails.

“Let’s stop,” I said. “There’s something wrong with this game. You take a coin which is already mine, flip it, and then give me a chance to win it back?”

He grinned, as did his son.

I said, “It’s a peculiar game if you are the only one who can win.”

Then we all laughed, and he gave me back the nickel. “I wondered how many coins you would lose before you caught on,’’ he said. I sat there for a moment, pleased with myself, when he asked, “And would you also like to have your quarter back?” Embarrassed that I had not remembered to ask for it myself, I said I surely would.

This experience was both unsettling and funny, as I pondered how gullible I had been. One of his findings was that a slight sense of confusion would enhance trance induction, so my momentary bewilderment showed that I was probably in a light state of trance. I certainly didn’t feel hypnotized, but in retrospect I must have been. What did I learn from this prank? That it is one thing to trust a person in authority who is your teacher, but quite another to be gullible and easily exploited. This profound lesson was certainly a good one for a fledgling psychiatrist, or even an old psychiatrist, and it taught me a lot about how to appraise an appropriate doctor-patient relationship or, indeed, any relationship.

Another training director and I were talking a few years later, and he said he would like to share an important lesson with me: there are two kinds of people in life, those who are at least a little bit paranoid, and those who are damned fools. This is a useful aphorism, indeed valuable, but it comes to you like a sledgehammer, while Dr. Erickson’s way of teaching was more like a velvet glove. Moreover, he never said a single word to me about what the coin toss game was all about, and for some reason it never dawned on me to ask him directly the why or wherefore of it. All these years later, I’m still coming up with possible meanings and messages from it.

2. The Summer Camp Game

The Rorschach ink blot test presents the viewer with an ambiguous visual object, and his interpretation of what it looks like reveals some of his characteristic ways of finding meaning in the world around him. Dr. Erickson’s games were like action scenarios that required a person to act in a certain way, thereby revealing how he might act to manage the world around him and, further, how he might have handled the situation better if given another chance . . . and life itself is an ambiguous situation, a projective psychological test.

At the end of dinner on another evening at his home, he asked if the next day I would do a physical examination and fill out the form for one of his sons, a 10-year-old who was applying to go to summer camp. Of course I would do it, I said. At 11 a.m. the next day, having finished my morning ward duties, I phoned to ask that the boy come to meet me in one of the examining rooms. On examining his chest, I was surprised to hear a loud systolic murmur. I asked if anybody had ever told him he had a heart murmur, and he said yes. Then I asked if he had gone to summer camp the year before, and again he said yes. I decided I should talk about this with his dad and not involve the boy in further conversation. The rest of the exam went well, and the two of us then walked to his home, where his father was waiting. Speaking privately with Dr. Erickson, I told him of hearing the murmur, and wondered if he knew of it.

“Oh yes,” he said, smiling. “It’s nothing serious; last year the cardiologist said there was no reason the boy should not go to summer camp.” I breathed a sigh of relief, and then handed back to him the examination form he had asked me to fill out.

“You should have the same cardiologist fill it out again this year,” I said, as I did the smiling.

What did I learn from this trap he set for me? That you should trust your judgment, that you should have the courage to make a decision, that you should not assume that you will be given all the facts you should know before being asked to solve a problem, that you should be willing to help and do a favor up to a certain point only and no farther. I was certain Dr. Erickson had my best interests at heart, but I did not feel good about being tested that way; it seemed more like being tricked. Nonetheless, I felt I had earned a passing grade. Here again, he said nothing to me about what it was meant to teach, or how I did, but left me to deal with it in my own way. He never even said he was teaching anything or that I was learning anything; that was all in my own mind. Teaching of such a high order is truly liberating.

3. The Walking on Ice Game

Dr. Erickson and I were both leaving the building at the same time one winter afternoon.

Sly fox that he was, I am almost certain that he planned it that way. A mixture of freezing rain and sleet had made the walkway to the building for which we were headed, about 30 yards away, quite slippery. He walked with a cane, so I realized at once that we had a challenge. When Dr. Erickson asked me to give him a hand, I held his arm as firmly and steadily as I could as we began to edge along. He soon said, “Stop. You’re doing it the wrong way. All you need to do is hold your arm and hand steady. Let me do the holding, not you. I know when to hold tighter, and then more loosely, or not at all. You just need to be there with a steady arm.” We walked comfortably and easily the rest of the way.

The lesson here was that you alone cannot accurately anticipate or assess what your patient needs. The patient himself can do it better. Your task is to have the courage to believe that the patient will trust his judgment of what is best for him and can treat himself better than you.

Psychiatrists are particularly vulnerable to this fallacy of omniscience, believing that patients who disagree with them are showing “resistance” to true insight, but patients will be directed by their own inner compass. This is why the best salesman is the one who believes “the customer (who, in this case, is the patient) is always right.” Dr. Erickson spent 60 seconds ostensibly talking about walking on ice; I spent a great deal of time over the next 60 years thinking of how that was a metaphor for the best way to be a therapist, a parent, a teacher, a friend. The fact that we found ourselves on a slippery walkway that day was a teachable moment for him and a great learning moment for me, staged by a masterful psychiatrist. Life is a slippery walk.

4. The Phenomenal Memory Game

Dr. Erickson would sometimes take all six psychiatry residents on special rounds to one of the large units where chronically ill patients had been receiving little more than custodial care for many years. Those who had recovered significantly almost always remained at the hospital and were given work assignments; relatively few returned to their home communities. Many patients we saw demonstrated unusual symptoms like waxy flexibility, in which they remained in odd positions or postures like a statue, and would sometimes allow an arm or leg to be moved into another position, where it would remain. Other patients had bizarre delusions and hallucinatory experiences or were totally disorganized and regressed. In giving the history of one such patient, Dr. Erickson displayed a remarkable memory of the minutest details of the family history, and various treatment modalities that had been tried with various degrees of success, followed by relapse. At the conclusion of rounds, as we were returning to our offices or our room, I stopped by the medical record room and requested that particular patient’s record in order to verify Dr. Erickson’s dazzling performance. I was told that the record had been checked out by another staff member, and I asked to be notified when it was returned, so I could come and pick it up. When I returned to my office minutes later, I saw the patient’s medical chart lying on my desk. On top of it was a note from Dr. Erickson: “I thought you would want to check out this record, so I brought it to you.” It took my breath away to think that he had read my mind like that.

By this time, I had become more intellectually wary and skeptical, particularly in dealings with Dr. Erickson. The lesson here was that he not only realized this, but apparently welcomed it as a sign that I was no longer easily conned. When extraordinary feats are performed and remarkable claims made, always question them, no matter who makes them, including prominent teachers and even your director of training. Moreover, if you do not raise a question, you can be sure one of your more alert colleagues will. Again, we said nothing to each other about the incident and, again, it remains as clear to me as the day it occurred.

5. The Game of Being Black

Dr. Erickson never discussed what he thought about race relations, but his actions demonstrated that he had warm feelings toward me as a person, which I reciprocated. He not only spent more personal time with me than he did with the other residents, but also showed his lack of prejudice in other ways. He was often invited to speak before groups in the Detroit area about hypnosis and to demonstrate hypnotic induction and the trance state. For several years, one of his special hypnotic subjects was a young black female secretary in Detroit who was able to go into profound depths of trance. On one occasion, he invited me to come with them for a presentation after a luncheon at a women’s club in a nearby town. He introduced me as one of his psychiatry residents, and made it clear that I would have no role in the actual demonstration, which went very well. Only later did it occur to me that Dr. Erickson may also have thought having me along that day would give him cover, preventing wagging tongues from spreading tales of his traveling alone with an attractive young black woman.

One afternoon near Christmas during my training year, I noticed that the whole hospital complex was uncommonly quiet. Going to my office, I found a note on my desk from Dr. Erickson that read something like this: “At 4 p.m. go to room 402 and look inside.” Somewhat puzzled, I did as suggested, and saw all the staff, including him, laughing and drinking and having a great time at a Christmas party to which I had not been invited. I felt deeply humiliated and betrayed, realizing that I had been treated this way because I was black.

On my way to my room in another building, I wondered why Dr. Erickson wanted to rub my nose in it but, as time passed, I understood his message: Yes, you do have white friends who care for you, but there are many more whites who consider you less than a person, and the ugly fact is that you can expect to be a victim of racial prejudice and discrimination throughout your life.

Nothing can protect you from that social evil, neither your white nor black friends, nor even your black parents and family. It will be up to you to decide how to deal with it. You can allow it to stunt your full growth and development, or you can have it spur you to a creative response of strength and mastery, rather than tearful surrender.

He did me a favor by confronting me with reality. I have known some black people, especially professionals, who have settled into a safe cocoon with a few white friends, turning a blind eye and deaf ear to other black people and the outside world. Other blacks I have known have slammed the door against all white people, shunning even those who would join them in a fight against a whole set of social evils.

Dr. Erickson challenged me to bring out the best within myself: and he was just the right role model for the job: a crippled, tone-deaf, color-blind specialist in a stigmatized field, who had become one of the most productive psychiatrists of his generation. Working with him was one of the great experiences of my life; he truly helped introduce me both to myself and to those around me. And, most especially, he helped me get ready for New York.

My mentor in New York was Dr. Viola W. Bernard, who had paved the way for my acceptance into both the residency program at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center and as a trainee in the Columbia University College of Physicians and Surgeons’ Psychoanalytic Clinic for Training and Research. Her own life was remarkable in many ways.

Born into a wealthy and prominent Jewish family in New York, she dropped out of several colleges before graduating from Cornell University Medical School, one of only four women in her class. She was a towering figure in the history of American psychiatry, not only for her leading role in desegregating post-graduate training in our discipline, but also as one of the founders of Columbia’s Psychoanalytic Clinic as well as almost singlehandedly creating the division of Community Psychiatry, a collaboration between the Columbia University Department of Psychiatry and its School of Public Health. She also was one of founders of the Group for the Advancement of Psychiatry, comprising leaders in the profession who wrote a series of monographs on a wide variety of social policy issues in the 1950s and 1960s, including poverty, child welfare reform, racially segregated schools, the end of war, and nuclear disarmament.

She conducted the personal psychoanalysis that was part of my training, which required five sessions a week for three years. I arrived in New York just a few weeks after my marriage, ready to start my residency and psychoanalytic training simultaneously. When I told her of my marriage, Dr. Bernard said this was a problem, because people should not make major life decisions while they’re undergoing psychoanalysis. We began work, nonetheless, but I felt stupid and uneasy about having broken one of the cardinal rules from the start.

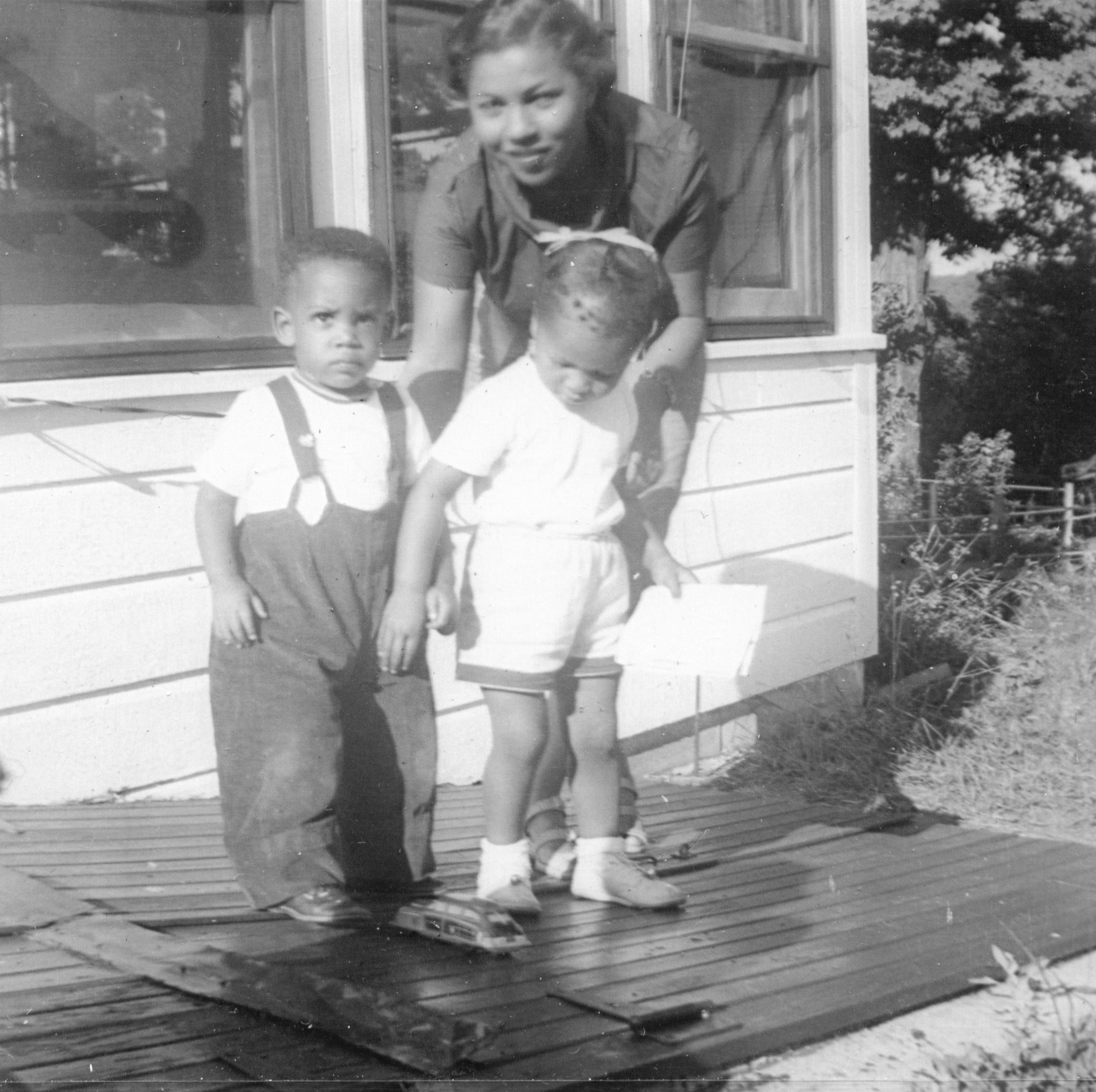

Vivian and I both believed it was our good fortune to have been thrown together by fate in the same place at the same time; both of us were among the first blacks to train in our respective fields at Wayne County General Hospital. We decided to marry about six months after we met. Vivian had taught music in the Detroit Public Schools for a year following her graduation from West Virginia State University, but she didn’t find the job satisfying and was quick to apply, and be accepted, when the University of Michigan School of Social Work began offering scholarships to attract black students into the field. Her earnings as a teacher had enabled her to get an apartment, which she shared with a friend, and to purchase a car, which helped our friendship rapidly develop into a full-time romance. She had grown up in Little Rock, Arkansas, a more completely racially segregated setting than mine, and had had no experience associating with whites, having attended segregated public schools and what was then an all-black college. The University of Michigan School of Social Work was her first experience in racially integrated education, while that was all I had known. Not only was I very close to several white friends, but Vivian and I spent our brief honeymoon at the summer cottage of the family of one of my Albion College friends. Our intellectual backgrounds did not match, either. She had always received high grades, including at the University of Michigan, but had no background in reading the same newspapers, journals and books that had turned me into something of a young radical. It seemed to me she had no opinion about, or even much interest in, most social issues. But the fact that she was very attractive outweighed all of those minor issues, and so I had gone ahead with marriage plans; not without some ambivalence on my part, which she soon put to rest with her good looks and take-charge manner.

My psychoanalysis was a different story. Lying on the couch five times a week, and saying everything that came into my mind, came close to unraveling my marriage, and I soon found myself, for the first time, feeling anxious and afraid, as I had been warned might be the case.

Dr. Potter had exempted me from spending Saturdays during my residency program in the Northport, Long Island, Veterans’ Administration Hospital, where the other residents worked with acutely ill patients in the psychiatry unit, because I had already had a year of inpatient psychiatry at Wayne County General. That exemption made it possible for me to begin work at the Columbia Psychoanalytic Clinic, which scheduled heavy course work for beginning students on Tuesdays and Saturdays. The director of the clinic was Dr. Sandor Rado, who had been education director of the New York Psychoanalytic Society from the time that he emigrated from Hungary to escape the Nazi regime. After he left the New York Psychoanalytic Society to protest its rigid dogmatism, he was one of the founders and the director of the Columbia clinic, the first psychoanalytic clinic under university auspices. He was a brilliant psychoanalytic teacher, but absolutely intolerant of any opinion other than his own, which made it painful to listen to him make statements in his lectures to provoke responses which he would then bitterly denounce.

The essence of his theory of human behavior was based on the evolutionary progression of behavior from simple one-cell animals, which are in a resting state of homeostasis until pushed toward a pleasurable stimulus or repelled by a painful one. Higher animals are similarly guided by pleasurable or painful states of emotion. Pleasurable, or what he called “welfare,” emotions, such as love, are controlled by the parasympathetic nervous system. In threatening situations, the emergency responses — such as flight, fight, rage and guilt — trigger into action the sympathetic pole of the autonomic nervous system. Those phylogenetically older layers of our central nervous system still function in human beings, but are supplemented by newer portions of the cerebral cortex which give us the ability not only to fight or flee but also to call for the group membership support available to all social animals, and also to use our higher levels of language and other symbolic instrumentalities. This leads to his thesis that neurosis is an expression of human adaptational failure in social, occupational, and sexual function. The core of schizophrenia, for example, is an innate failure of the central nervous system to register or to feel pain and pleasure appropriately, thus leaving the victim without a reliable behavioral compass.

It has been pointed out that while this theory demystifies Freudian psychodynamics, it borrows heavily from Alfred Adler, one of the earliest defectors from Freud, and even from ancient Greek philosophers like Plato and Aristotle, who saw similarities of behavior in all plants and animals.

Dr. Rado’s view of human behavioral motivation was an early version of what we now recognize as the field of evolutionary psychology. He believed that psychoanalysts should pay serious attention to scientific studies in animal behavior, along with developments in neurology, neurophysiology, neurochemistry, genetics, clinical psychology, anthropology, and child development. The Psychoanalytic Clinic was housed in the same building as the New York State Psychiatric Institute. As students at the Psychoanalytic Clinic, we took brief courses taught by scientists of the New York State Psychiatric Institute in all those areas, as well as learning the historical sequence of Freud’s theory of human behavior. In recent decades, it has become clear that Freudian psychoanalytic theory and practice did not rest on a firm scientific base. Dr. Rado was clear that human behavior and animal behavior were part of the same evolutionary spectrum, and he dogmatically rejected all Freudian terminology and theory. We know now that orthodox Freudian theory resembles a religious cult not supported by the scientific method since its basic tenets are non-falsifiable.

A personal analysis, required of all trainees, is a difficult experience, but it most definitely offers an unusual opportunity to promote one’s developmental potential. In the process of learning to free associate, you begin to lose some of your fear of thinking by saying your thoughts out loud. It certainly was liberating for me to have a more complete view of myself. It requires an act of faith to believe that you can have any conceivable thought and it doesn’t make you a bad person; that, in fact, being able to think evil can provide some protection against evil behavior. You learn to listen to your continuous inner dialogue during the day as well as understand the inner dramas during sleep that allusively comment on past, future and feared future experiences. Seeing the analyst five times a week in privacy furthers the development of deep transference reactions, some of which so disturbed me that I would shake uncontrollably while lying on the couch.

Among the first hurdles I had to overcome were my fear of and prejudice against whites, and my hostility toward them, which kept me from achieving the intimacy I often desired. For example, when one of my 15 classmates offered me a bite of the apple he was eating one day, I politely declined, with thanks. As my analyst pointed out, I was sending a loud negative message to his strongly positive offer of friendship. That classmate and I did eventually become friends and exchanged visits to each other’s homes, as was the case with four other classmates with whom I developed close personal relationships.

My wife was having even more difficulty in handling a new, less segregated world. In our first year, our Columbia classmates had a party which all of us attended. Vivian and I were having a good time singing and dancing together until she told me she wasn’t feeling well and asked if we could go home, which we did. When I asked what was wrong, she said she had to leave because her period was beginning. Dr. Bernard pointed out to me that the ladies room would have solved her problem, as my wife must have known, and that the friendly socializing with whites was most likely what disturbed her. This seemed even clearer when Vivian wanted us to decline an invitation given to me by Dr. Potter, my residency training director, that we spend the weekend on Long Island with him and his wife. Dr. Bernard pointed out that this failure to accept friendship could hurt us in many ways. Fortunately, my wife had been hired as a social worker at Kings County Hospital, where many of my residency training sessions were located, and she gradually became comfortably friendly with at least a dozen white social workers and other staff there. We soon had a large circle of friends, black and white, and we both became more comfortable New Yorkers. Later, my wife also entered personal analysis, which failed with her the first time, but was more successful the second.

As my own analysis proceeded, new insights came to me that only long-term treatment could have provided. For example, my father had died on February 2, Groundhog Day, but I had not sufficiently grieved his loss. Changes in my behavior that recurred annually at that time of the year made it clear from my dreams that I was having serious anniversary depressive and psychosomatic reactions, of which I was totally unaware. Also, I had an unusually strong sibling rivalry with my brother, Tom, whose birthday was October 27, the exact same as my father’s, and I realized that in my unconscious mind this proved my father favored him over me. Most of all, however, the major themes of my life revolved around my simultaneous desire for and fear of money, power, and any kind of sex.

I believe it is only possible to come to terms with issues of that magnitude through long-term analysis. However, because therapist and patient are alone and in private for extended periods of time, in a relationship in which the therapist has dominance and control, it is not a safe situation for the vulnerable patients unless practitioners are in comfortable control of their own behavior. As students in an analytic training situation, one has close working relationships with other psychoanalysts who may be supervising the cases of the patients you are treating. Those supervisory sessions are fertile sources for learning, but you can also be given a jolt now and then. One of these faculty members told me that one of my main problems was that I wasn’t angry enough, and more than one male faculty member remarked that I should have had a male psychoanalyst rather than a woman as my analyst and I should realize that, after finishing with Dr. Bernard, I would have to do it all over again with a man.

But the greatest blow to my ego came when Abram Kardiner and Lionel Ovesy, faculty members at the clinic, published The Mark of Oppression: A Psychosocial Study of the American Negro in 1951. Their basic thesis was that group characteristics are adaptive in nature, not inborn but acquired. Case histories of 25 Negroes, some of them patients at the associated Columbia clinics and others paid subjects, were selected as representative of lower, middle, and upper class Negroes. This small convenience sample provided interview and psychological test data that led the authors to conclude that a specific Negro personality profile exists. In contrast to whites (not even studied comparatively), “The Negro is a more unhappy person . . . he enjoys less, he suffers more . . . The final result is a wretched internal life. This does not mean he is a worse citizen. It merely means that he must be more careful and vigilant, and must exercise controls of which the white man is free. . . . Moreover, it diminishes the total social effectiveness of the personality.” Differences between the races, they wrote, reflect themselves primarily in “the self-esteem systems, in the development of affectivity, and in the disposition to aggression, which, in turn, create different patterns of family structure, the relation between the sexes, the social cohesion and the characteristics of Negro religion and folklore and artistic creativity. The major features of the Negro personality emerge from each with remarkable consistency. These include the fear of relatedness, suspicion, mistrust, the enormous problem of control of aggression, the denial mechanism, the tendency to dissipate the tension of a provocative situation by reducing it to something simpler, or to something entirely different. All these maneuvers are in the interest of not meeting reality head on.”

Of course, I was furious that this picture of an inferior stereotype was put forth as derived from scientific data. After discussing it at length with my analyst, I requested a personal visit with Dr. Kardiner to give him an idea of what it felt like to hear a black person openly confront him with a contrary opinion of what black people are like, and show how they can present a point of view head on. I asked him how he would react if a study of 25 Jews in New York claimed to have discovered a typical Jewish personality that confirmed a common stereotype. From the historical point of view, I pointed out that white slaveholders embraced a much different stereotype of blacks as happy-go-lucky, fun-loving, sexually uninhibited Uncle Toms and Aunt Jemimas, because that portrait suited their needs. Dr. Kardiner listened to me patiently and said he would think about what I had said. I felt a lot better having given a rebuttal to a teacher who, in effect, was telling me that I was in the wrong field and had no future.

It goes without saying that all blacks are not alike in their personalities and styles of behavior. This is true of any group, but there is also no doubt that sociodemographic opinion studies reveal sharp differences between groups in matters of political and economic market behavior, reflecting their various vested interests. In an article for The New Republic of June 10, 2002 entitled “Civilizational Imprisonments,” Amartya Sen makes the point that all persons belong to many groups — religious, national, social class, gender, ethnicity, professional, and occupational, among others — but that each person must be free to choose the extent to which such group membership will shape his or her identity, depending on the contextual and situational priorities. Even within groups, however, there are always varying degrees of conflict and harmony, of cooperation and competition with other groups, although there is one basic worldwide civilization which is shared by all humans.

I can think of an experiment which would shed light on the question of whether or not black people are able to be happy. The study could be run at multiple sites by leading research universities nationwide. In cities with large black and white population groups throughout the country, arrange a dinner dance party for 500 persons of each population group on the same Saturday night. An hour after the party is going full blast, have a photographer snap 1,000 pictures of the revelers. Let trained judges, using a happiness scale from 1 to 10, rate the subjects who were photographed. Even before going through the procedure, you know with certainty which group would rate highest for happiness. Similar rating scales could score the apparent amount and volume of conversation, as well as the level of spontaneity shown in dancing. Then follow those groups to church on Sunday morning and check out the range of emotional, verbal, and musical expression. Really, the notion that black people don’t have fun, or relate to, or communicate or compete or cooperate with each other, is preposterous!

As I neared the end of my residency and my major coursework at the Psychoanalytic Clinic, I made plans to open an office and go into private practice, treating adults and children. With financing from the William T. Grant Foundation, I completed a year of training in child psychiatry under the aegis of the Jewish Board of Guardians, whose clinics were located in Brooklyn and the Bronx. That agency did not accept black patients, but I was warmly welcomed as a trainee by the director, Herschel Alt, one of the great organizers of mental health services in New York. The previous year, I had worked half-time at the Northside Center for Child Development, a clinic founded in Harlem by the famous black psychologists Kenneth and Mamie Clark, all of whose clients were black children and their parents. These experiences broadened my clinical interest to working with all age and racial groups. A white psychologist on the part-time staff of the Board of Guardians, who had a private practice and was leaving New York, offered to sublet to me her office on Manhattan’s Upper East Side, an exclusive neighborhood.

I had furnished the office and was just beginning to accept new patients when the Korean War broke out in the summer of 1950. In 1952, I was notified that since I had served in the Army Specialist Training Program during World War II, and had received most of my medical schooling at Army expense, I would be required to spend two years of military service, as a captain in the Air Force at one of its base hospitals, as a payback. Before completing my psychoanalytic training, I would have to spend two years treating short-term and long-term patients under supervision. Fortunately, a close friend Dr. Elizabeth Davis, a black woman in the class just behind me at Columbia, was willing to accept my furnished office and my sublease obligation. A two-year hiatus in my analytic training was imminent.

In 1950, my wife and I had purchased a three-story brownstone house in Brooklyn, near Eastern Parkway, from a Jewish psychiatrist who was eager to move his family because the neighborhood was “going black.” By 1952, I had finished my psychiatry residency and was eligible for board certification. I could complete my analytic training by seeing my patients in the evenings at Columbia and attending Saturday morning seminars there. Faculty at Columbia arranged for me to go to Washington, D.C., and request that I be stationed at Mitchell Air Force Base Hospital in Hempstead, Long Island. The hospital needed a chief for its psychiatry service, and I successfully applied for that position. I could drive 45 minutes from my home to the Air Force base, then drive to Columbia in upper Manhattan after the workday for sessions with my two long-term patients, returning home at about 8:30 p.m. for a late dinner with my wife. One of the other psychiatrists on my staff at the base was also in training at the Psychoanalytic Clinic, and another was a researcher at the New York State Psychiatric Institute. My two years as chief of psychiatry at Mitchell Field were among the best of my training experiences.

President Harry Truman had partially desegregated the military services in 1948, a job completed by President Dwight Eisenhower, and the stigmas of racial caste and second-class citizenship were fading quickly. For example, I was not the only black chief of service at the base hospital. The chief of orthopedic surgery and the chief of pediatrics also were black, while all the other physicians on our staff were white or Asian. It was hard for me to believe this was accidental, rather than a decision by the top brass in the Air Force to send a strong message of racial equality. Black officers and their families had full use of the Officers Club, and all Air Force personnel and their families on the base lived in totally integrated housing. What a far cry from my World War II experience at the segregated Camp Wheeler Army Base near Macon, Georgia, or in the all-black Army Specialized Training Program unit to which I belonged. Eleanor Roosevelt and others had forged into being the Tuskegee Airmen, whose legendary achievements in air combat belied the myth that blacks were too ignorant to fly a plane. It was, of course, the 1954 Supreme Court decision, Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka that outlawed state-sanctioned racial segregation of schools, reversing more than half a century of a legalized racial caste system.

Our psychiatric service consisted of a 20-bed inpatient unit for the acutely ill, and a large outpatient clinic serving enlisted men, officers, and their families. Our staff consisted of three psychiatrists in addition to me, five nurses, three psychologists, and two social workers. Orders to go overseas sent shock waves through every member of the family, wives and children as well as servicemen. I learned the powerful effect that motivation could have on an individual’s clinical presentation. Young men with a history of serious psychiatric illness, who had undergone successful treatment and wanted to be trained as pilots, passed every hurdle presented by thorough interviews and batteries of psychological tests. On the other side of the coin, officers and enlisted men desperate to avoid going overseas managed to look like failures, along with their crumbling families. As chief of service, I also learned the significant role played by medical testimony in legal proceedings against enlisted men or officers, since it could be used to determine their competence to stand trial and cooperate in their defense, or whether they bore responsibility for their alleged misconduct. Skillful examination was also required when servicemen were discharged, since determinations of service-connected disability could affect their pension entitlement.

My first article in a medical journal was accepted while I served at Mitchell Field. It appeared in the United States Armed Forces Medical Journal for July 1955 and described a convenience sample of 55 expectant fathers who lived on the base with their families. Most striking was the finding that many of the men unconsciously identified with their pregnant spouses, while others showed signs of reawakened and angry sibling rivalry, most disruptively among those men who had received poor care from their own parents, whose behavior they were repeating. The men fell into three groups, according to the severity of their problems.

There were 17 men in Group A, four of whom were black. All of them had come to the psychiatry service, either voluntarily or on referral from sick call or the military authorities, for serious depression. In one case, this involved a suicide attempt that required hospitalization on our inpatient ward. Other causes for referral were anxiety and irritability that interfered with duty, physical symptoms causing psychological distress or, most troubling of all, acts of covert or overt rebelliousness that, in one instance, led to court martial.

The 14 men in Group B, including the only two commissioned officers in the whole sample as well as two blacks, showed milder symptoms than those in Group A. The 24 men in Group C, two of whom were black, had not been treated at the psychiatry service. They were randomly selected from a group of 240 airmen that I had asked to be screened so their incidence of behavioral problems would represent a normal community sample. A set of screening tools had been administered to them, including a brief family history, current parental status and parental expectancy, record of visits to Sick Call in the most recent six months, a check list of current physical and mental health, and three wishes. They were then asked to draw a picture of an imaginary animal and write a brief story in which the animal was doing something.

Requesting such a drawing was part of my mental status examination of all my patients at the time, and all the men in all three groups had been asked to do this because I had seen them all.

The article was well received professionally and earned inclusion in the Yearbook of Neurology, Psychiatry, and Neurosurgery, the annual collection of important articles in the field. But it was also featured in Time magazine (August 8, 1955), accompanied by a James Thurber cartoon in which one of two older gentlemen seated in lounge chairs at their club, looking dejected and worn, tells the other, “I never really recovered after the birth of my first baby.” Requests for reprints came both from this country and abroad, many friends congratulated me, and other friends pointed to possible problems in my methodology. My satisfaction was unbounded.

But professional success during my days at Mitchell Field was intermingled with several painful and tragic experiences, which reappeared with great force at crucial intervals. I believe that how I learned to cope with those personal experiences gave my life story a special depth.

The first occurred when Larry, our first-born, almost died when he was six months old. His temperature hovered near 106 degrees for six days, requiring us to cool his whole body continuously; most of the time he was limp as a rag. Pediatricians at the base hospital could not determine the cause, but suspected a viral infection. I myself had been hospitalized a week earlier with a case of viral pericarditis (the pericardium is the membrane surrounding the heart) that suddenly hit me with symptoms exactly like those of a heart attack (cardiac thrombosis); I thought I was near death. Several others on the base had been hospitalized with exactly the same illness, all of us recovering completely after several days.

There were other problems. Although Larry’s development had seemed normal at first, signs of pervasive developmental delay gradually became obvious. He was slow in learning to walk, in learning to play, in toilet training, and especially in learning to talk and smile and socialize with others. He became attached to objects, like a favorite cowboy gun belt, and had uncontrollable tantrums if they were out of his sight or reach.

Despite these signs of autism, we enrolled him in an excellent private school, which provided him with individual tutoring sessions for most of the school day. But by the time he was eight, we were advised to place him in a day school program for developmentally disabled children. A year later, he was accepted at the same facility for full-time care. One of the leading specialists in the study of autistic children followed his clinical course for 15 years and advised Vivian and me on the best way to meet his needs until he became an adult. Vivian took a leave from her social work position at Kings County Hospital, and spent most of the next five years tending to his needs and also to her own long-term analytic treatment. Fortunately, our professional experience had brought both of us into contact with other parents of children with special needs, and this painful experience drew us closer together rather than tearing us apart.

Our second son, Paul, a bright-eyed, outgoing, cheerful, and talented child, was born two years after Larry, in 1955. We could not have managed without the assistance of one of my cousins, a practical nurse who lived in Chicago at the time and worked in a hospital. She was single and accepted our offer for her to come live and work with us, which she did for some years. Her warm and loving care for both of our boys made it possible for Vivian to return to her professional career. Paul was nine years old when we decided to send him to a New England prep school for boys, on the advice of a psychiatrist friend whose son had gone there a few years earlier.

My wife secured a position in the child and adolescent psychiatry division on her return to work. After two years, she became that unit’s head social worker, and three years later she was named director of all medical and psychiatric social work for Kings County Hospital, the city’s largest municipal hospital. All the social work schools in the New York metropolitan area sent their students to Kings County for their second year of field placement, where they worked under the supervision of her staff, making her one of the most influential regional leaders in the profession.

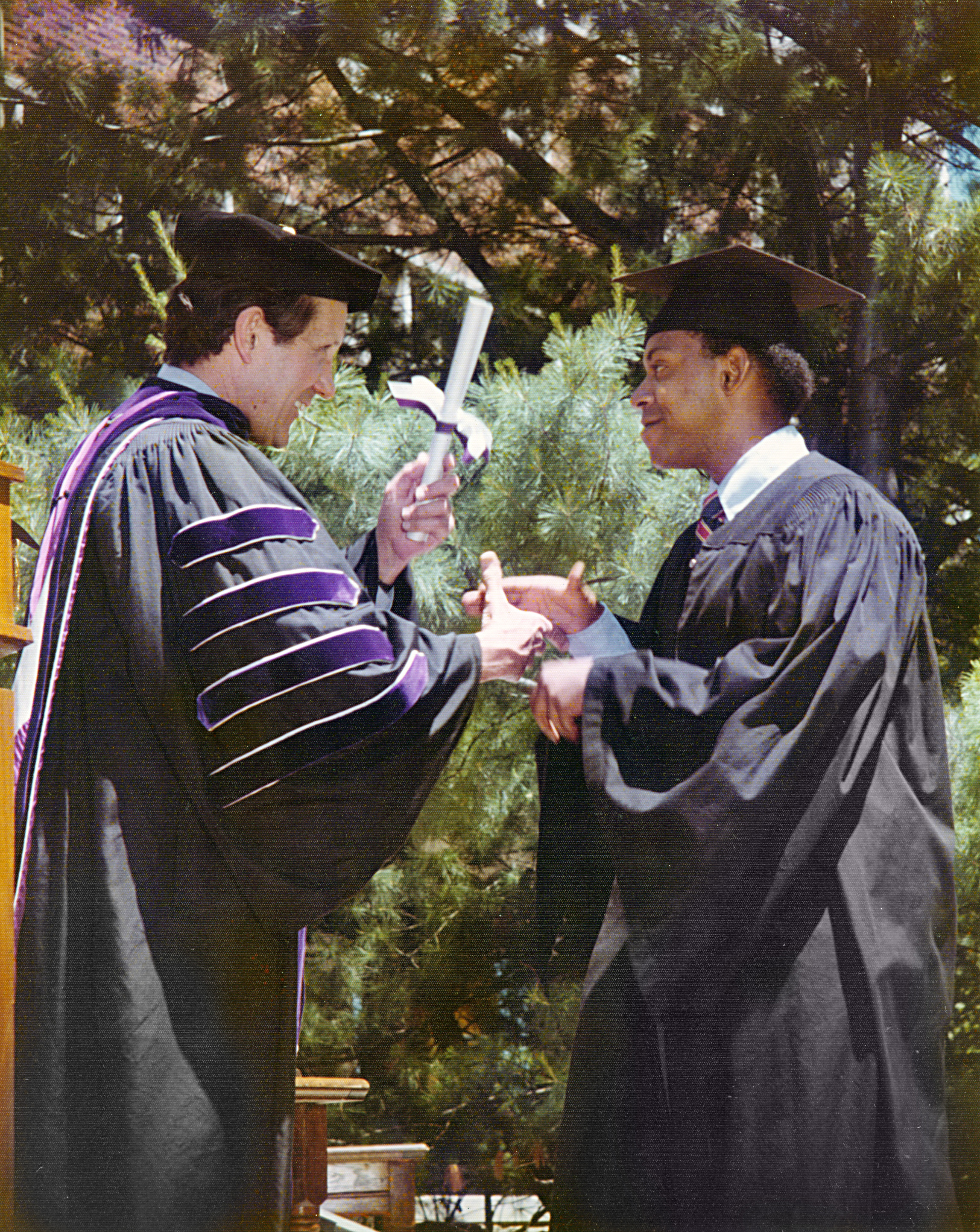

Meanwhile, Paul continued to excel in his studies and showed promise of becoming a writer. He graduated with double honors in English and philosophy from Amherst College and was accepted for graduate study at Harvard. After two months of work on the philosophy of religions, he had a psychotic break, suffering from bipolar disorder so acute that he required hospitalization. On his recovery a year later, he was accepted into Harvard Law School, but suffered a relapse requiring another hospital stay toward the end of his first year because he had become non-compliant with medication and treatment. He recovered slowly, and never sufficiently for him to be self-supportive. Vivian and I purchased a condominium for him, and he was eventually able to become a broker, buying and selling antiques, which he did until he died of a heart attack at age 52 in 2007.

My wife had been Kings County Hospital’s director of social work for more than 20 years when she retired in 1995. Two years later, she began to show signs of Alzheimer’s disease. The illness gradually took its ghastly toll, and she spent the last five years of her life in a nursing home before passing away in August 2007. Four months later, our son Paul died. Both of these deaths brought me to depths of grief and sadness that almost destroyed my soul. Our oldest son, Larry, and I are the sole remaining shreds of our immediate family. He has lived for more than 20 years in a small group home in New York with seven other mentally disabled adults, where he has been well cared for and involved in a sheltered work program during the day.

I have chosen to introduce these painful experiences at this point in my narrative, because they deeply affected my private life for the whole period of my professional life. From the early 1950s onward, I suffered great mental anguish, but I also realized my good fortune in being financially able to provide the best care that money could buy. Providing that same opportunity to others became a guiding mission for me, as I came to realize that a selfish preoccupation with my personal misfortunes paled in comparison with the compassion I should feel for the multitude of sufferers in the world who are hopelessly unable to preserve and enjoy their human potential.

At the end of my tour of duty in the Air Force in 1954, I accepted a half-time faculty appointment as assistant professor of psychiatry at the State University of New York Downstate Medical Center in Brooklyn. The position was offered to me by Dr. Howard Potter, who had accepted me into the residency training program there and who was not only head of the department of psychiatry but was also dean of the medical school. As I had by that time become board certified and completed my training at the Columbia Psychoanalytic Clinic, he actually offered me a full-time faculty position with tenure, but at a salary I could not accept because my family responsibilities required that I develop a larger private practice. We agreed I could accept only a half-time appointment. I was to work in a new building, which was being built to house a research program of studies in psychosomatic medicine, headed by Dr. Robert Dickes, an internist who had also been trained in psychiatry and psychoanalysis. I spent mornings there and afternoons and early evenings in my office, which occupied the ground floor of our Brooklyn brownstone.

My plan was to develop an interracial private practice, since I had become an active member of the black medical society in Brooklyn and was a close friend of several black psychiatrists in various stages of training with me, and both my wife and I had an increasing number of white friends who were our colleagues. Slowly but surely, the practice was growing. Another Columbia psychoanalytic graduate was on the Downstate psychiatry faculty, and his office was located in Manhattan. When an internist in Manhattan referred a young woman who lived in Brooklyn and needed psychotherapy to him for treatment, he explained that his hours were filled, but asked her if she would accept a referral to a black psychiatrist who lived not far from her in Brooklyn, that we had trained together and that he knew I was very good. She accepted and saw me for two sessions. When she next saw her internist, she told him that she was seeing me, and that even though my office was in a black neighborhood, it was all right with her. It was not all right with him. He flew into a rage, said she should stop seeing me at once, and angrily assured the young Jewish psychiatrist who had sent her to me that never again would he receive another referral.

My colleague and I discussed the whole episode, and he said that a segregated neighborhood was a serious liability for me. He suggested I move my office to downtown Brooklyn, preferably Brooklyn Heights, where the leading psychiatrists were located. I agreed with him, and also apologized for costing him future referrals. It could be very costly for a white person to be known to other whites as a friend of blacks. Another white colleague who lived in a suburb confided to me that if he and his wife invited me to their home, a committee of their neighbors would descend on them with vitriol, as had happened to one of their friends who had ignored the color barrier.

Getting an office in downtown Brooklyn or the Heights proved to be a daunting task. After showing me several offices, one rental agent told me that the property owner did not feel comfortable renting space to a psychiatrist. He must have had a lapse of memory on seeing me, because there were already psychiatrists in his buildings. Another agent claimed that another physician who had wavered on the matter suddenly changed his mind and wanted it, immediately after he showed it to me. One of my black friends, a psychiatrist who looked white, and I decided to put the matter to a test, which turned out exactly as we expected. That same real estate agent urged her to rent that same office a week later. It didn’t matter that racial discrimination was against the law in New York at that time. Indeed, you recall that I had had an office in a superior location in Manhattan that I had to give up when I was called into the Air Force, and my friend who posed as a potential tenant was still subletting it from me! I was finally able to rent an office in a good location in Brooklyn Heights, with views of the Statue of Liberty and Governor’s Island, because I found, quite by accident, a rental agent who also managed the real estate properties of one of Brooklyn’s huge and prosperous black Baptist churches, including sites in downtown Brooklyn. With a good location and referrals from black as well as white friends, my practice grew and flourished.

Nonetheless, I began to grow increasingly uncomfortable with the thought of spending my career treating a small number of middle- and upper-class private patients, white or black, but they were the only ones who were able to pay or had the verbal and cognitive skills to be suitable patients. This discomfort led to the major decision to become a psychiatric consultant to child and family social agencies in which social workers were the primary therapists. I was the one with whom they and their supervisors would meet for input on psychiatric and psychodynamic factors that might be hindering the child and family functions. Dr. Bernard, my former analyst, was among the psychoanalysts who had spearheaded this collaboration between social work and psychoanalysis. So was Dr. Nathan Ackerman, who was also on the Columbia analytic clinic faculty. They were moving our field toward family therapy and community psychiatry consultation and away from treating only private patients.

My first consultant role was with the Salvation Army Family Service Agency, which had offices in all the boroughs of the city and served a large part of the impoverished black community. Later, I also became psychiatric consultant to the Salvation Army Foster Home Service, the major social service agency for black children requiring foster home placement and for families applying to adopt children. A large network of child and family service agencies had evolved in New York City beginning in the 19th century, when successive waves of immigrant families came to live there. These agencies, like hospitals, were founded and operated along strictly sectarian grounds: Jewish, Catholic, and Protestant. The Jewish and Catholic agencies had continued to strengthen, especially after huge amounts of government funding began to surpass and supplant the contributions of wealthy philanthropists of those faiths.

Meanwhile, the Protestant agencies grew weaker; their middle and upper classes had earlier abandoned the city for the suburbs, leaving behind a working and impoverished Protestant community that became increasingly black and politically powerless. Even when blacks became a strong presence in New York City, black social service agencies were non-existent. The reason, it seemed to me, was that black churches are of many different Protestant denominations with no tradition of united action and relatively little wealth. This was why the Salvation Army, a Protestant organization with excellent professional leadership but no congregation in the usual sense, had become the principal voluntary social service agency for black people in New York. In another effort to make up for the lack of a strong Protestant social service presence, the New York City Department of Welfare had developed its own public social service divisions to provide services for children requiring foster home placement and troubled families, who were soon to become predominantly black . It was for these reasons that I began to do an increasing amount of psychiatric consultation for the Salvation Army, an agency that never has received the recognition and support it deserves.

The New York City Youth Board, in charge of clinical services to combat juvenile delinquency, developed a special project under which child and family agencies would work with a few hundred of the city’s most difficult multiproblem families. The Salvation Army Family Service Agency was awarded a contract to work with 30 of these families, and set up a special team of two social workers, one black and one white, and a supervisor named Melly Simon, widely known for her competence and experience, to do it. I was to be the psychiatric consultant who met with the team in my office for three hours, an entire morning, once a week for five years.

Mayor Robert Wagner had a personal interest in the project’s success, as did leaders in the social work field, because an improved pattern of service delivery was needed: it was known that only about 6 percent of the city’s families were utilizing two-thirds of its social service resources. The mayor himself met each month with social work supervisors from the agencies with contracts. Also present at those meetings were heads of the city human service departments, such as welfare, courts and corrections, public schools, health, and housing. It was believed that only this high-level political leadership could bring about collaboration among those departments to meet these families’ needs.

As a part of this plan, an unprecedented amount of data was provided on each multi-problem family: for example, the entire school record for each child in the family, all of the criminal records of the parents and children, and the histories of social services provided in the past to all family members. It must be recalled that, in the 1950s, every individual social worker’s entire work history was available for review by the agencies where they applied for work, including supervisor evaluations, rebuttals by the social worker, and the results of corrective action. This level of sharing information about clients and therapists had probably never been experienced before, and not until later years was there greater privacy protection. Moreover, as I noted earlier, every psychoanalytic candidate underwent a personal training analysis, involving scrutiny of the details of his or her personal life five times a week for several years, prior to becoming certified. Living in a goldfish bowl was an everyday experience in the therapeutic world of that day. Any candidate in psychoanalytic training who self-reported as being homosexual was immediately dismissed from further training, and any reported criminal conduct led to the same end. Only after becoming a certified specialist or a director of a social service did one become immune to this kind of potentially fatal scrutiny. Of course misconduct by those of high authority was almost the order of the day. For example, candidates for psychoanalytic training were immediately dismissed for what was then regarded as misconduct, but certified psychoanalysts who were supervisors led private lives full of scandal, for which they were rarely sanctioned. The same is true of all professionals even now, including priests and heads of corporations.

What our Salvation Army team learned was reported at an annual meeting of the American Orthopsychiatric Association and published in their journal. During our weekly meetings, we heard of the progress being made by these families, all of whom had a complicated network of problems, including physical disability, psychiatric issues, difficulties in school, and how they handled their welfare allowances, their housing, and their encounters with the criminal justice system.

These families could be grouped into four categories. In one were those who cleverly avoided all but the most minimal contact with the authorities. They were unable to avoid it entirely since they were receiving entitlements, and records of their behavior were available to us anyway. Surprisingly, that group tightened up their behavior on their own initiative, as if to justify their position that we should go home and leave them alone. Another group also vigorously resisted our outreach efforts, but they continued to be just as “multiproblem” as before, despite our best efforts. Still another group entered into what seemed to be a good, sustained working relationship, but their insatiable need and willingness to seek help made little or no real difference in reducing their problematic behavior. The last group formed a good working relationship and significantly improved in some areas of family behavior, but they were definitely in the minority and showed few solid gains. It usually took no more than six months for us to determine the category in which a family belonged, and they rarely moved. For example, these 29 families included 67 children ages 6 to 12 years, 28 children ages 13 to 18, and 9 who were 19 or older. In the five years we worked with them, not one of these children received a regular high school diploma. There were 20 school dropouts in the families when we began the project, and another 19 by the time it ended. One-third of the families remained the same overall or were worse off, while the other two-thirds made sporadic temporary improvement, but only in a few areas.

We were criticized mercilessly by one member of the audience at the annual meeting where we reported our findings. A radical who subscribed to the school of thought of the day that all rebellious behavior against authority was praiseworthy, rather than a problem, described our intervention as “soft police work,” trying to compel a group of healthy but rebellious families to adhere to middle-class morality. In his view, we were the multiproblem culprits and should be ashamed.

I was grateful for the lessons I learned from years of close work with those families. They were, indeed, in rebellion, but it was an unhealthy and self-defeating form of rebellion and completely outside their conscious control. What I was coming to see was that they needed a healthier and more life-enhancing form of rebellion, and that it would require a whole new set of human service institutions providing help throughout the entire life span. One other lesson, which I learned many years later, is that a therapeutic or other human institution is made more efficient by maximum information transparency, as we had back in the 1950s. This cleansing sunshine, however, was only required of foot soldiers and service recipients, not of the leaders in the social hierarchy. Better law enforcement or policing or privacy protection is no substitute for social institutions that allow parents to care for their families or children to want to learn or accept social behavior norms. Families cannot have responsible and loving parents, able to raise happy and productive children who become successful parents themselves, unless they have good jobs which pay a living wage, a voice in the political rules of the game governing their livelihood and safety, and freedom from exploitation by a privileged elite engaged in perpetual warfare and competitive greed. You cannot oppress the common people by hiring policemen, schoolteachers, social workers, psychiatrists and other therapists to make them happy or send them to prison if they refuse to submit.

When Vivian and I learned that Larry, our first child, had special needs, it prompted us to return to the church, which we had abandoned during our college years. She had been reared in the Methodist church and I was from a family of the Baptist faith. I attended meetings of the Unitarian Church several times while I was at the University of Michigan, and had enjoyed the lack of formality and ritual. I was also drawn to their belief that each person should feel comfortable in creating, based on their own life experience and current understanding, a belief system which helps them accept responsibility to create whatever good or evil exists in our world.

As we were considering which church to join, I became close friends with the Rev. Milton Galamison, pastor of the Siloam Presbyterian Church, one of the oldest, largest and most influential churches in the Bedford-Stuyvesant section of Brooklyn. He received his bachelor’s degree from Lincoln University; founded in Pennsylvania in 1854 to educate black men, it was the first degree-granting historically black university in the United States and produced many of the great leaders in the nation’s black community. Rev. Galamison went on to earn a master’s degree from Princeton Theological Seminary, and was called at age 26 to be the senior pastor at Siloam. The Presbyterian Church had gone beyond its devotional focus of preaching against playing cards, drinking, and dancing, and touting sexual propriety as a gateway to heaven. The denomination’s leadership was a more progressive wing, clearly devoted to the Social Gospel of eliminating poverty, capitalist greed, war, and racism. Rev. Galamison was of that more modern persuasion, so we hit it off from the start. He and his wife became among our closest friends and we became enthusiastic members of Siloam.

It greatly disappointed us and the Galamisons that despite Brown v. Board of Education, the historic 1954 Supreme Court decision that outlawed racial segregation in public schools, the public school system in New York City, a bastion of liberal thought, remained racially segregated and offered inferior schooling for blacks as well as Puerto Ricans, a growing minority. Even the NAACP was satisfied with incremental progress in changing this situation, leading Galamison to break away and form a new alliance with the Congress for Racial Equality and leftist groups that were demanding more immediate action. Specifically, the city’s Board of Education had offered no plan or timetable for change. Reverend Galamison and his supporters staged several massive boycotts of the public schools, in one of which 500,000 children stayed away from classes. But the movement ran into difficulty when a faction began to demand that local school districts should form community school boards, which would completely govern the hiring and firing of teachers and administrators and also control the curriculum. This idea was bitterly opposed by the Teachers’ Union and the controversy soon took on an anti-labor and anti-Semitic tone, which Rev. Galamison opposed but could not control. He became a member of the Board of Education (a position which I helped him obtain; as a staff member of the community Mental Health Board I had recommended that Mayor John Lindsey appoint him). After his term expired he essentially retreated from active involvement in what he concluded was a futile mission, leaving him despondent and publicly inactive. The public school situation, as well as neighborhood segregation, remains until this day one of New York City’s greatest failures.