The University of Michigan in China

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

9. The University of Michigan and China

As of the winter semester of 2016, more than 40% of all international students at the University of Michigan (U-M) come from China, four times the enrollment of the next highest country. Clearly, the partnerships forged at the end of the 19th century and rekindled in the 1970s have roared to even greater heights in the 21st century. The work done by the individuals in the previous chapters to reach across cultural divides, to carve out new niches of authority and autonomy for underrepresented populations, to build new institutions, to jump-start whole disciplines—that work continues today at U-M.

Education Expands

More than a century after James Angell put his presidential duties on hold to serve as a diplomat in China, another University of Michigan president made the trip overseas. In 2005, President Mary Sue Coleman made a week-long trip to Beijing, Shanghai, and Hong Kong to strengthen the relationship between U-M and China. As Coleman put it, “Scholarship knows no borders . . . By our very nature, universities are at the forefront of globalization and cooperation” (Coleman).

China, meanwhile, was in the throes of a massive surge in demand for higher education. Just as the early 20th century saw the creation of some of China’s most prestigious academic institutions, the 21st century arrived with a desire to make good on that intellectual legacy. In 2005, the year of Coleman’s visit, the number of Chinese students enrolled in colleges and universities crossed the 15 million mark; just 10 years prior, that number had been only 3 million (Li and Yang 16). Coleman and the Chinese institutions she visited seized this historic moment to create a whole wave of new collaborations between the University of Michigan and China.

One such collaboration came at the request of China’s Ministry of Education and National Academy of Education Administration, which worked with U-M to compose a Michigan–China University Leadership Forum. The forum, held in 2006, convened in Ann Arbor. Led by U-M faculty and staff and organized by U-M’s Center for Research on Learning and Teaching (CRLT), the forum gave attendees a chance to share pedagogical and administrative strategies and to discuss “several major topics that the Chinese Ministry of Education . . . deemed helpful to the Chinese educational reform” (CRLT). Representatives from the highest levels of China’s most elite academic institutions attended, and just a year later, a study conducted by members of the CRLT found that the forum had led to a “remarkably long and varied list of new initiatives.” A primary takeaway from the first forum, it seemed, was an emphasis on “improving the student experience”; after more than a decade of explosive growth, the University leaders interviewed for the report indicated a desire to focus “on student services and student learning and . . . trying to instill new quality standards” (Cook and Zhu).

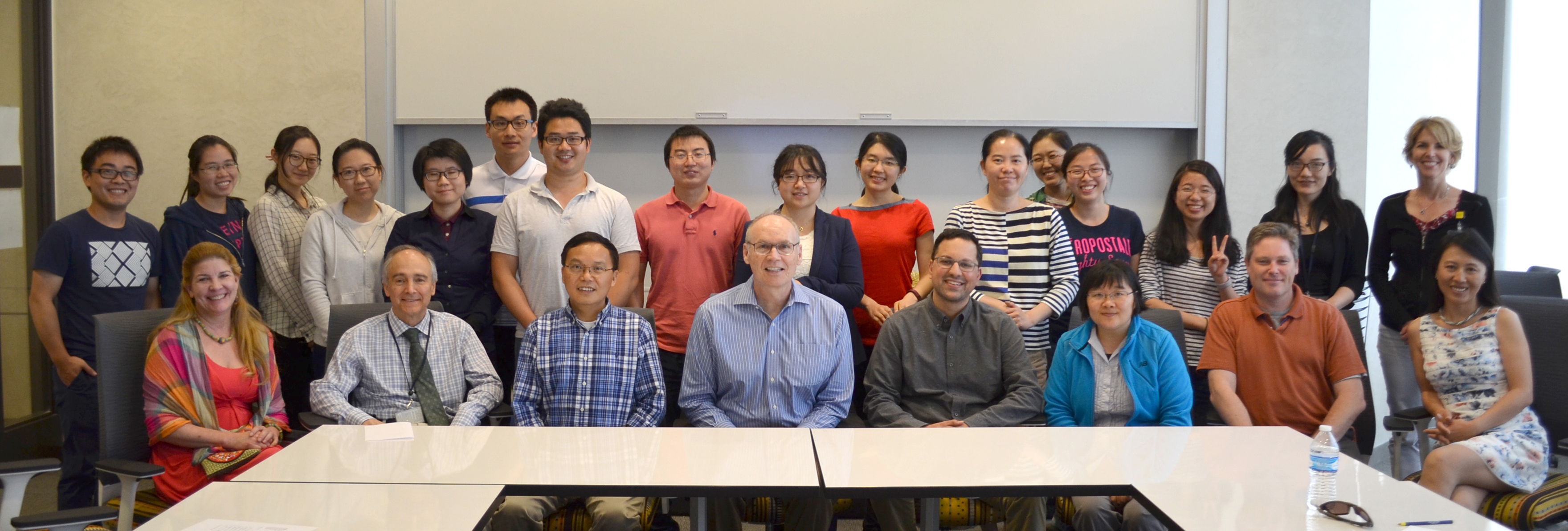

A group photo during the first Michigan–China University Leadership Forum in 2006. On the bottom row, left to right, are Edward Gramlich, then interim provost at U-M; Zhou Qifeng, then president of Jilin University and later president of Beijing University; University of Michigan President Mary Sue Coleman; and Wu Qidi, vice minister of the Ministry of Education, People‘s Republic of China (PRC). Photograph courtesy of Erping Zhu.

The first Michigan–China University Leadership Forum was enough of a success to continue biennially. The CRLT at U-M, America’s first teaching center, became an international role model: “An eight-day Faculty Development Institute for leaders from 10 Chinese research universities” facilitated by the CRLT “resulted in the creation of 30 new model teaching centers by the Chinese Ministry of Education” (CRLT). As China works to implement a decade-long reform of higher education, the University of Michigan has been an eager partner, exchanging ideas and expertise with the leaders of China’s academia.

A second major partnership began “as a simple research collaboration” almost 20 years ago (Redden). Dr. Jun Ni, a professor at U-M’s College of Engineering, arranged to collaborate with researchers at his alma mater, Shanghai Jiao Tong University (SJTU). “‘I thought maybe we could start some kind of partnership between the two universities to help them with curriculum development,’” Ni said in a 2014 interview, and soon his individual collaboration bloomed into an institutional exchange. In 2006, a year after Mary Sue Coleman’s visit and the inaugural year of the Michigan–China University Leadership Forum, Ni’s research collaboration became the UM-SJTU Joint Institute. “Guided by a board of directors made up of top leaders from both institutions,” the institute offers a variety of engineering degrees with a “curriculum adapted from Michigan’s” (Redden). The joint institute brings international education home to China, with classes in English, dual degrees, and study abroad experiences available.

The leadership of U-M and Shanghai Jiao Tong University at the signing ceremony to establish the joint institute in 2005. Photograph courtesy of Jun Ni.

The joint institute (JI) has flourished since its early days, winning several national awards for model education and excellence in reform. In 2014, the joint institute “was the first Chinese institution to win the Andrew Heiskell Award for International Education.” What’s more, “since the first class of JI graduated in 2010, more than 80% of its graduates have continued on to pursue graduate degrees” (“Joint Institute”). The University of Michigan has been the happy recipient of many of these graduates, who have followed in the footsteps of scholars like Wu Dayou, He Yizhen, and Zhu Guangya, all of whom pursued graduate degrees at U-M.

The joint-institute model for collaboration between universities has been adopted by multiple other colleges within the University of Michigan. The social sciences division of the College of Literature, Science, and the Arts at U-M has developed a relationship with Fudan University, establishing a joint institute for gender studies at Fudan and funding collaborative research through U-M’s Center for Chinese Studies. Grants of up to $10,000 a year for two years have been made available to encourage scholars from both universities to propose joint research projects. The institute has sponsored multiple international conferences, translated gender studies publications, and run several PhD credential programs and dissertation workshops.

An even more substantial partnership developed in 2010 between the University of Michigan Medical School (UMMS) and the Peking University Health Science Center (PUHSC). With a commitment of $7 million from each institution, they came together with the goal of enabling “scientists to translate basic research more quickly and efficiently into medical practice,” ultimately improving patient health across the United States and China (“About Us,” Joint Institute). And in the last seven years, the Joint Institute for Translational and Clinical Research formed by UMMS and PUHSC has already made significant strides. Since 2010, “the JI has funded 25 joint research projects involving more than 100,000 patients in both the US and China” (“May 2016”). In 2015, both institutions renewed their $7 million commitment, and there is every indication that the joint institute will continue its work for many years. It speaks to the urgency of the institute’s mission that the challenges of joint leadership; of organizing research, symposia, and publications across the divides of culture, language, and distance; and of mobilizing two enormous institutions have all been overcome with such aplomb.

Cultural Exchange at the University of Michigan

Cross-cultural education has been valued at the University of Michigan since the early days, from Levi Barbour’s scholarship endowment in 1917 to the educational delegation to China led by Donald Munro in the 1970s. The year 2017 marks the centennial anniversary of the Barbour Scholarship, but it is not alone—today, U-M is full of avenues for cultural exchange.

A group photograph of the Joint Institute for Translational and Clinical Research’s Sixth Annual Symposium, held in the fall of 2016. Photograph courtesy of Amy Huang.

Several colleges at the University of Michigan have developed unique study abroad programs for both American and Chinese students. The Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, for example, has created a course on US-China policy that culminates in a two-week-long trip through some of China’s largest cities. The trip’s organizer, Ann Lin, hopes that the epiphanies of travel will “upend [students’] preconceived notions about China” and that the program will “prompt students to return to China throughout their careers.” In return, each fall, the Ford School invites “two professors from Renmin University in Beijing . . . to teach courses on Chinese economic and foreign policy” (“Renewing”).

A similar exchange happens at the College of Engineering, where Dr. Lumin Wang, a professor of the Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences (NERS) Department, began to organize trips abroad for University of Michigan students. “For a whole generation in the US, we weren’t building reactors,” Wang said in a 2016 interview. “Not only nuclear engineering students but also many faculty hadn’t ever seen how a reactor is built.” China, however, “has more than two dozen reactors . . . under construction.” For Wang and the College of Engineering, this presented a clear educational opportunity. In collaboration with Xiamen University, they created the Chinese Culture and Clean Energy Summer School, a six-week program at Xiamen University with an optional follow-up internship at the Shanghai Nuclear Energy Research and Design Institute. As with the Ford School, NERS offers a reciprocal exchange: “Shortly after the Clean Energy Summer School ended at Xiamen University, Professors Wang and Fleming hosted a group of 24 undergraduates from the university for two weeks in Ann Arbor,” a stay that included lectures at U-M, field trips to Detroit, and a bus trip along the East Coast of the United States (Roth).

But as important as the study abroad exchanges can be, they represent the tip of the iceberg of China’s presence at the University of Michigan. The Confucius Institute at U-M (CIUM), for example, is a bastion of Chinese arts and culture and “an integral component of former president Mary Sue Coleman’s ‘China Initiatives’” (“About CIUM”). Launched in 2009, the CIUM is just one of hundreds of similar Confucius Institutes scattered across the globe, each sponsored by Hanban, the Chinese National Office for Teaching Chinese as a Foreign Language, an affiliate of China’s Ministry of Education:

Unique within the network, however, CIUM’s focus is primarily on the promotion of Chinese arts and cultures, from the ancient to the modern, forming a strong arts component of former president Coleman’s China Initiative, and advancing the university’s global programs and initiatives overall. “The Confucius Institute at the University of Michigan will be singular among its peers, an extraordinary resource to all within the university community and far beyond,” said Lester Monts, former Senior Vice Provost of Academic Affairs. (“Background”)

Under the leadership of James Holloway, Joseph Lam, Lester Monts, and Louis Yen, the CIUM has lived up to its promise. It runs cultural workshops for U-M students, including workshops on calligraphy and cooking Chinese cuisine; the institute hosts screenings of Chinese films at local Ann Arbor theaters, organizes lectures and symposia, and sponsors music and theater performances at U-M; and CIUM runs two separate programs, a Chinese studies program for U-M students and a visiting scholars program for Chinese faculty. And more programs are in the works, including a new student workshop about Chinese opera and theater and an online archive of all the Chinese art museums in North America.

The Confucius Institute at the University of Michigan has an academic counterpart in the University of Michigan’s Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies (CCS). Named for Richard Rogel, an investor and benefactor whose vision for U-M includes a close relationship with China, and Kenneth Lieberthal, a professor emeritus of U-M and one of the United States’ leading experts on Chinese policy, the CCS has a long history at the University of Michigan. While U-M formally inaugurated China Studies as early as 1930 with the Oriental Civilizations Program, the Center for Chinese Studies was formed several decades later, in 1961:

Rapidly it became a warm community in which the members’ professional colleagues were also their social friends. It was an era of trans-disciplinary cooperation. Early on, under the leadership of Alexander Eckstein, a long lasting course on “China’s Evolution Under Communism” was taught jointly by an economist (Alexander Eckstein), a political scientist (Alan Whiting, then Michael Oksenberg), and a philosopher (Donald Munro). In the same spirit, Professor of Modern Chinese Literature Yi-Tsi Feuerwerker designed “Arts and Letters of China,” team-taught by her and by Richard Edwards (Chinese History of Art), and Donald Munro (Chinese Philosophy). (Munro)

A concert with Song dynasty chime bells organized by the Confucius Institute at U-M. Photograph courtesy of Jiyoung Lee.

Just as in the 1960s, the CCS “serves as a major intellectual hub for understanding China”: for students at the University of Michigan, the CCS offers courses, interdisciplinary master’s degree programs, and postdoctoral fellowships; for faculty, the CCS provides everything from travel and research grants to support for outreach and course development; and for the larger community, “many faculty associates have engaged in public service . . . as consultants to the State of Michigan, US State Department, World Bank, and even the White House,” continuing the intellectual and diplomatic legacy of Alexander Eckstein (“About Us,” Lieberthal-Rogel Center). Together with the Center for Japanese Studies and Nam Center for Korean Studies, the CCS belongs to the East Asia National Resource Center at U-M. To be marked a National Resource Center is a prestigious designation granted by the US government to a select few universities.

A fashion show organized in 2013 by the Confucius Institute at the University of Michigan. Photograph courtesy of Jiyoung Lee.

Taken together, the exchange programs, Confucius Institute, and the Center for Chinese Studies all show how far the University of Michigan has come since its early days in the 19th century. Where U-M once extended a tentative hand to China through missionaries and naturalists, we have now brought China home to Michigan, embedded in the heart of the University.

Toward the Future

The pace of the University of Michigan’s collaborations with China is only accelerating, with more joint institutes, research partnerships, and student exchanges springing up every year.

The School of Natural Resources and Environment at U-M, for example, has created an accelerated master’s degree program with the School of Environment at Tsinghua University, in which undergraduates from Tsinghua gain credits toward an MS at the University of Michigan. The School of Public Health recently signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU) with the West China School of Medicine of Sichuan University. Just as with the Shanghai Jiao Tong University Joint Institute, the initiative of an individual collaborator led to an institutional partnership. The efforts of U-M’s Dr. Yi Li to help establish the West China Biostatics and Cost-Benefits Research Center snowballed into an MOU that “formalizes cooperation between the institutes through scholar exchanges, faculty training, collaboration in academic research and big data analyses, and establishing a joint institute” (“Cooperation”).

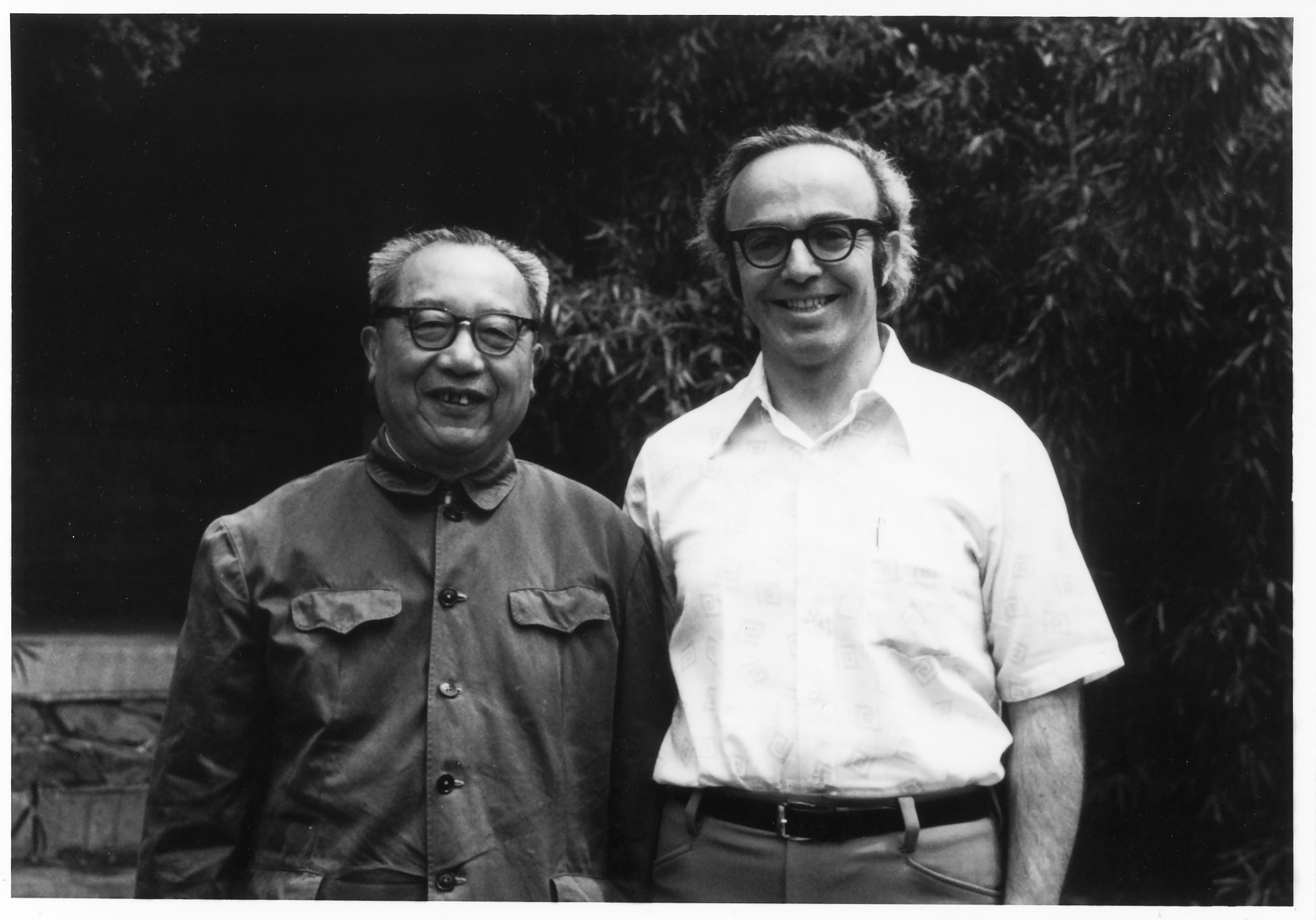

Albert Feuerwerker (right), history professor at U-M and founding director of the Center for Chinese Studies, with Fei Xiaotong, a sociologist, anthropologist, and social activist in China. Photograph courtesy of the Center for Chinese Studies.

The UMMS is at the center of two other recent partnerships. A joint program invites MD students from PUHSC to pursue a five-year PhD at UMMS before completing their medical degrees at PUHSC. “Five years is a long time,” said Huilun Wang, one of the program’s most recent students, “but I came for the PhD program because I wanted to explore medicine more broadly to find new treatments, new medicines for patients—something you cannot learn in just an MD program.” With scholarship funding from Richard Rogel and leadership from Drs. Joseph Kolars, Eugene Chen, and Amy Huang, the joint program has been operating successfully for five years now, helping “develop a growing community of physician scientists” at PUHSC (“Joint”).

Philanthropist Richard Rogel (right) with the recipients of his University of Michigan Health System-Peking University Health Science Center Joint Institute MD-PhD scholarship. Photograph courtesy of Wenying Liang.

A similar joint program under the leadership of Dr. Eugene Chen just graduated its first cohort of five students. Just “one part of a larger partnership, formalized in 2014, with Xiangya School of Medicine,” this joint program invites MD students from Xiangya to complete a two-year research program at UMMS. Pei Li, a student who has already published work done through the program, explained the exchange’s importance: “In China, most medical school graduates typically have two choices, to be a university professor or a practicing doctor,” she said. “After this, I have another plan. I want to apply for a Ph.D. program and continue doing research” (“Medical School”).

Today, the University of Michigan’s partnerships in China extend even outside academia: “On January 19, 2017, S. Jack Hu, University of Michigan (U-M) Vice President for Research, signed an agreement with DiDi Chuxing, China’s largest rider-hailing company, to develop scholarships and innovations related to the ride-share economy.” A number of researchers from the Civil and Environmental Engineering Department at U-M will join the almost $1 million collaboration, a “joint research program” that will focus on “transportation optimization, big data, artificial language learning, and artificial intelligence” in the hopes of “better understanding transportation-behavior norms, reducing congestion on the global transportation infrastructure, and providing solutions to mobility” (“CEE Faculty”).

A cohort of physician scientists from the Xiangya-UM joint degree program. Seated third and fourth from left are Drs. Eugene Chen and Joseph Kolars. Photograph courtesy of Craig McCool.

The leadership of U-M together with the Beijing Institute for Collaborative Innovation. Photograph courtesy of Chuanwu Xi.

And a new partnership with the Beijing Institute of Collaborative Innovation (BICI) will unlock the potential of University of Michigan researchers. A “system for collaborative innovation” founded by 14 of China’s top universities, BICI provides technical support and funding for researchers trying to bring their projects to market (“BICI Fact Sheet”). Jack Hu helped bring U-M and BICI together, and now the partnership is under the guidance of Drs. Chuanwu Xi and Tiefei Dong at U-M. BICI “has agreed to fund U-M research and translational research in a broad range of areas, including engineering, health, science and environmental technologies from sponsored research” (“UM-BICI”). And in fact, BICI has already done so. In its first round of funding in 2016, BICI funded three projects in chemistry, biomedical engineering, and applied physics.

For every step of China’s growth and transformation in the last century and a half—from the end of the Qing dynasty, to the turmoil of the era of warlordism through the war years, to the birth of the People’s Republic, and finally to the rapprochement of the 1970s—the University of Michigan has walked right alongside China. The leaders and scholars who found the knowledge and expertise at Michigan to transform China set a high bar for those who have come after. The University has done its best to live up to the promise of individuals like Ding Maoying, John C. H. Wu, Zhu Guangya, and Wu Dayou. In the last several decades, U-M has thrown open its doors to the best Chinese universities, researchers, and students as if to old friends—Welcome, says the University. Our best years are still ahead of us.

Works Cited

- “About CIUM.” Confucius Institute at the U of Michigan, n.d. Web. 12 March 2017. <http://www.confucius.umich.edu/about-us/>.

- “About Us.” Joint Institute for Translational and Clinical Research. U of Michigan Health System and Peking U Health Science Center, n.d. Web. March 2017. <http://www.puuma.org/about-us>.

- “About Us.” Lieberthal-Rogel Center for Chinese Studies, n.d. Web. 15 March 2017. <https://www.ii.umich.edu/lrccs/about-us.html>.

- “Background.” Confucius Institute at the U of Michigan, n.d. Web. 15 March 2017. <http://www.confucius.umich.edu/about-us/background/>.

- “BICI Fact Sheet.” Beijing Institute of Collaborative Innovation, n.d. Web. 20 March 2017. <http://innovator.co/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/BICI-Fact-Sheet_EN_XZ_Final.pdf>.

- “CEE Faculty Partner with Didi Chuxing for Transportation Research.” Civil and Environmental Engineering 26 Jan. 2017. Web. <http://www.cee.umich.edu/cee-faculty-partner-didi-chuxing-transportation-research>.

- Coleman, William. “Key Initiatives: International Education.” University Record, 10 March 2014. Web. <https://www.record.umich.edu/articles/key-initiatives-international-education>.

- Cook, Constance, and Erping Zhu. “2006 Michigan-China University Leadership Forum: Evaluation One Year Later.” Ministry of Education of the People’s Republic of China, May 2007. Web. <http://www.moe.gov.cn/publicfiles/business/htmlfiles/moe/s2994/201001/75811.html>.

- “Cooperation between UM-SPH and WCSM/WCH.” Ann Arbor: School of Public Health, U of Michigan, n.d. Web. 18 March 2017. <https://www.sph.umich.edu/>.

- “CRLT’s Work with the Chinese Ministry of Education (MOE) and Chinese Universities.” Ann Arbor: Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, n.d. Web. <http://www.crlt.umich.edu/>.

- “Joint Institute.” Shanghai Jiao Tong U, n.d. Web. 28 March 2017. <http://en.sjtu.edu.cn/admission/joint-institute>.

- “Joint PhD Program for Chinese Students Growing.” Global Reach. U of Michigan Medical School, n.d. Web. 18 March 2017. <http://globalreach.med.umich.edu/articles/joint-phd-program-chinese-students-growing>.

- Li, Mei, and Yang Rui. “Governance Reforms in Higher Education: A Study of China.” International Institute for Education Planning (2014): n.p. Web. <http://unesdoc.unesco.org/images/0023/002318/231858e.pdf>.

- “May 2016.” News and Events. Joint Institute for Translational and Clinical Research, n.d. Web. 29 March 2017. <http://www.puuma.org/ji-news-events>.

- “Medical School Helping to Train China’s Next Generation of Physician-Scientists.” Featured News. U of Michigan Medical School, 13 June 2016. Web. <https://medicine.umich.edu/medschool/news/medical-school-helping-train-china%E2%80%99s-next-generation-physician-scientists>.

- Redden, Elizabeth. “A Look at U. of Michigan’s Partnership with Shanghai Jiao Tong U.” Inside Higher Ed, March 2014. Web. <https://www.insidehighered.com/news/2014/03/12/look-u-michigans-partnership-shanghai-jiao-tong-u>.

- “Renewing and Strengthening the Ford School’s Long-Term Ties to China.” Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy, 3 Dec. 2015. Web. <http://fordschool.umich.edu/news/2015/renewing-and-strengthening-long-term-ties-china>.

- Roth, Kim. “Chinese Culture and Clean Energy Summer School: Student Exchanges Cross Borders and Expand Horizons.” Michigan Engineering, 5 Oct. 2015. Web. <http://www.engin.umich.edu/college/about/news/stories/2016/october/coe-and-ners-students-visit-and-collaborate-in-china>.

- “UM-BICI Partnership Program.” International Partnerships. Research at U of Michigan, n.d. Web. 20 March 2017. <http://research.umich.edu/research-u-m/international-partnerships/u-m-bici-partnership-program>.

Links and Resources

- Center for Chinese Studies at the University of Michigan

<https://www.ii.umich.edu/lrccs/about-us.html> - Center for Research on Learning and Teaching, Leadership Forum

<http://umich.edu/~crlteach/seminar/index.html> - Confucius Institute at the University of Michigan

<http://www.confucius.umich.edu> - Department of Nuclear Engineering and Radiological Sciences, Student Exchange

<http://www.engin.umich.edu/college/about/news/stories/2016/october/coe-and-ners-students-visit-and-collaborate-in-china> - Gerald R. Ford School of Public Policy

<http://fordschool.umich.edu/news/2015/renewing-and-strengthening-long-term-ties-china> - Joint Institute for Translational and Clinical Research

<http://www.puuma.org> - Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Joint Institute

<http://en.sjtu.edu.cn/admission/joint-institute> - University of Michigan, Beijing Institute for Collaborative Innovation

<http://research.umich.edu/research-u-m/international-partnerships/u-m-bici-partnership-program> - University of Michigan issue of Chinese Chemical Letters

<http://www.sciencedirect.com/science/journal/10018417/26/4>

Design Image Attributions

- Source: Jiao Bingzhen (焦秉貞), “New Visions at the Ch’ing Court,” 1689–1726.

- Source: Fan Kuan, “Travelers Among Mountains and Streams,” c. 1000.

- Source: Anonymous, “Suanpan in Ming Dynasty Novel,” Ming dynasty.

- Source: Zhi Chen, “Delight in the Winter,” 13 November 2014.

- Source: Zhi Chen, “Delight with the Red,” 16 January 2015.

- Source: Owen Jones, Examples of Chinese Ornament Selected from Objects in the South Kensington Museum and Other Collections, 1867, p. 179.

- Source: Owen Jones, Examples of Chinese Ornament Selected from Objects in the South Kensington Museum and Other Collections, 1867, p. 49.

- Source: Owen Jones, Examples of Chinese Ornament Selected from Objects in the South Kensington Museum and Other Collections, 1867, p. 141.