Creating Data Literate Students

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

10 Using data visualizations in the content areas

Why is delivering content through data visualizations important for motivating different learner types, developing literacy skills, delivering content, addressing standards, and improving performance on standardized tests?

“A picture is worth a thousand words” is a phrase that applies to any visualization. Sharing real-world data visualizations with students is informative and fun — it sparks interest and generates discussion. A graph, chart, table, or infographic packs a lot of data in a small space.

By analyzing graphs, charts, tables, and infographics students gain insight, identify patterns, and uncover new meanings while developing literacy skills. Student comprehension is enhanced through good data visualizations and students develop inquiry skills demanded by today’s standardized tests.

This chapter considers how incorporating different texts into instruction can motivate students in all content areas. Examples of data visualizations and lesson tips are provided across content areas. Sample data visualization questions from high school level standardized tests are discussed to help educators understand how important data literacy skills are to performance on these tests. How does this look in your classroom? Let’s find out.

Why is data visualization instruction important in the classroom?

Students learn best when motivated. My 15-year-old son can explain all aspects of a virtual world video game he’s been involved with for hours (if I let him). Yet, he insists on a 15-minute break for every 30 minutes of homework. Why can he focus with no brain break while gaming but cannot study U.S. history for more than 30 minutes? It’s simple: he’s not interested in U.S. history. He’s not motivated.

High school students can often recite endless facts about popular movies, a YouTube channel, or Kobe Bryant’s last game, but they don’t have a lot to say about Romeo and Juliet, earth science, world history, or personal finance. Elizabeth Moje (2006) hypothesizes that students’ motivation to obtain information shapes their ability to make sense of a text. If a student is not interested in a text, she argues, the student will not be interested in decoding, comprehending, or expressing information from that text. Moje asks whether the literacy skills obtained in a student’s out-of-school literacy pursuits can transfer to in-school contexts where academic literacy skills are required. Motivating texts can encourage struggling students to employ known reading strategies that they might not already employ while reading a traditional text.

Students may not have the inherent motivation to decode, comprehend, and express information. Yet, a text itself can motivate or demotivate. Students can regain interest in any content area by reading a motivating text. A student’s perceived value of a text determines its usefulness, which in turn engages the student’s interest. Moje explains that students’ preferred out-of-school texts “(a) represent aspects that feel real... in terms of age, geography, and ethnicity/race of the protagonists, (b) impart life lessons, (e.g.,resilience/survival, inspiration) (c) offer utility/practical knowledge, and (d) allow [students] to explore relationships” (p. 13). This is great news! By providing students with useful texts, i.e., data visualizations that offer practical knowledge, we are engaging (and sometimes re-engaging) content-area interest. We know students constantly engage themselves with visual information, so why not use data visualizations as a more intriguing entry point into content?

Many struggling students can benefit from using multiple texts to supplement a more traditional text (Moje 2006). Did you catch that? The intent of incorporating data visualization into content areas is not to replace traditional texts, but to supplement traditional texts. We do not want you to abandon the linguistic challenges of traditional texts. Data visualizations are tools to scaffold instruction and can be incorporated to differentiate instruction to meet the needs of varying types and levels of learners in our classrooms. Alternative texts such as tables, charts, graphs, and infographics can help struggling readers better understand traditional texts while piquing content-area interest.

Data literacy skills can be the same as literacy skills

Incorporating data visualizations into content areas is not all about statistics and probability (thank goodness). Considering the three key visualization types (chart, graph, or infographic) as new kinds of text, we can gather information the same way we gather information from a traditional text. Increasing a student’s data literacy increases a student’s literacy. Strategies that apply to decoding, comprehending, and expressing information in a traditional piece of text apply to any type of data visualization.

Minding the GAP

Student comprehension increases when using a strategy of the Reading Apprenticeship Framework, “Mind the GAP” (WestEd 2017). GAP is the acronym for genre, audience, and purpose. Students can “Mind the GAP” as a simple strategy to begin to understand any data visualization.

Consider using this strategy with an infographic:

- G (genre) – Students can determine why an infographic (the genre) was used to represent the information visually. Why is an infographic, with its combination of numerical, statistical, and text snippets, the best format?

- A (audience) – Audience can be determined by reviewing the source of the data, the creator of the text, and the means in which it is published. Who is the creator envisioning the reader or viewer of this work to be?

- P (purpose) – Purpose is determined by extracting the text’s data and studying it. Is it meant to inform or persuade?

In addition, simple strategies such as “Think Alouds” (teachers and students verbally expressing their comprehension of the text as it is read aloud) and “Talk to the Text” (written or digital text annotation as it is read through) can be applied to any data visualization to find the claim and its supporting evidence to achieve comprehension (Greenleaf 2014). These lend themselves to an ongoing conversation about how and what students are thinking when they read. Later in this chapter we will provide some examples of how data visualizations as text can deliver (and/or enhance) traditional content in the core curriculum areas and provide some lesson tips for “reading” visualizations.

Students develop real-world skills of interpreting information when data visualizations are incorporated into any content area. As a society, we are bombarded with charts, tables, and graphs. If we are unprepared to evaluate and interpret the data used to create a visualization, we are unable to learn from (or question) it. Consider associated data visualizations help us to better understand and decode articles in magazines and newspapers because they provide us with a quick summary of the data contained within the article. All a reader needs then is a basic understanding of statistics to be able to evaluate the information presented in a graph, chart, or table “with a more critical eye” (Gilmartin and Rex 2016, 5). Understanding the “language” of data visualizations helps our students interpret, analyze, and question information presented in multiple formats.

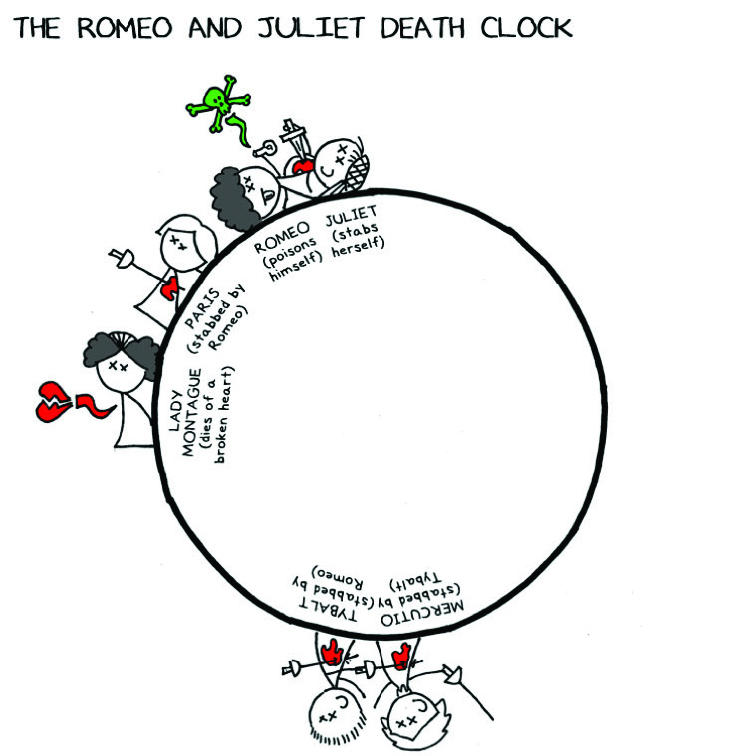

Example: Romeo and Juliet

There are many opportunities to mine data from traditional math and science textbooks. But what if we take text we do not traditionally think of as visual and make it so? Let’s consider William Shakespeare’s Romeo and Juliet. Quick — who dies in the play, how do they die, and in which order? Most of us read Shakespeare’s play at some point in high school, but remembering the sequence is as big a challenge today as it was back in our freshman year.

The key to student understanding is giving students the opportunity to gather information from supplemental texts as well, because many students cannot comprehend the action of Romeo and Juliet just by reading the unfamiliar prose. There are many ways to comprehend the tragedy inherent to Romeo and Juliet – including movies, audio recordings, and No Fear Shakespeare – but we can also use visualizations to help our students gain memory hooks upon which to map their knowledge of an extended text. We’ve actually been using visualizations for decades in our classes. Graphic organizers, drawing rising/falling action in plot lines, even diagramming sentences have all been part of the ELA toolkit. Modern visualizations just take this to the next step. Let’s look at how this information can be presented visually for better understanding. Consider this data visualization, “The Romeo and Juliet Death Clock” by Mya Gosling (2015):

c 2015 Mya Gosling; used with permission. Available from http://goodticklebrain.com/home/2015/8/26/the-romeo-and-juliet-death-clock .

Because the deaths are presented graphically, we can interpret this visualization and immediately determine:

- how many people die

- who dies

- at what point they die in the story

- how they die

- and even their countenance upon dying (those aren’t ears ... they’re smiles)

Looking at the graphic, how long did it take you to decipher those main plot points? How much time would it take to decipher the same main plot points from reading the text? This is a unique visualization. Gosling has created death clocks for just about every Shakespearean tragedy on her web site (goodticklebrain.com). Many students could quickly and easily interpret this visualization to add to their understanding of the text. This is not to suggest that data visualizations should replace traditional content — data visualizations should enhance traditional content.

At the end of this chapter, Appendix A provides a sample template for constructing data visualization conversations in your classroom. Appendix B brings another Romeo and Juliet infographic to ELA courses, while Appendices C-E preview other visualization activities across content areas that will help you think expansively about how to employ them in your curriculum.

Addressing national standards

When developing classroom curriculum, we must consider the applicable national standards. Let’s consider how the learning goals for college-and-career-ready students of the Common Core State Standards (CCSS) can be achieved through the integration of data visualizations into your content area. There is a link at the back of this book to a list of national standards that mention data and statistical literacy.

CCSS Learning Goals for English, Science, and Social Studies (College and Career Ready)

Using data visualizations as companion texts to traditional texts can help students discern key components they otherwise may have overlooked. A student’s level of comprehension can be misrepresented if the information is only presented in a wordier text. This is especially true for English language learners. Necessary skills are outlined for students who are college and career ready in the CCSS English Language Arts Introduction. While not part of the numbered standards, these capacities provide a description of students working toward meeting the standards while frequently displaying these skills. Incorporating data visualizations as companion texts can help develop the following CCSS capacities in our students (CCSSI 2017b).

Demonstrating independence

Think of the information students are exposed to through social media platforms like Twitter, Instagram, Pinterest, Tumblr, Facebook, Reddit, and dozens of others. A simple Internet search for the “top 10 social media platforms” will give you a better understanding of the most popular “news” sources on the Internet. How are these “news” sources different from pre-social media news sources? The answer is simple — most social media sources are not vetted.

The Internet is full of inaccurate and unauthoritative information. But it gets worse — every “fact” is passed on from one social media account to another with no regard for the source or the accuracy of the information it contains. Students should be armed with the ability to comprehend and evaluate “complex texts across a range of types and disciplines” so they’re able to “construct effective arguments and convey intricate or multifaceted information” (CCSSI 2017b). In short, our students need to be able to gather, evaluate, expand on, and articulate information to demonstrate comprehension.

Possessing a strong knowledge of content

Of course, we want our students to build strong subject content knowledge, but this content can come from varying texts, not just classroom textbooks. Students build strong knowledge by establishing “a base of knowledge across a wide range of subject matter by engaging with works of quality and substance” (CCSSI 2017b). Content knowledge can be gained through purposeful research and study of great data visualizations (as explained with the previous examples of content-area infographics). Students can then create their own data visualizations to share with others.

Responding to the varying demands of audience, purpose, task, and discipline

Our students are bombarded with information every minute of every day. A quick way to share information is through tables, charts, and graphs presented in authoritative daily news sources. In the analysis of these types of data visualizations, students must respond to the varying CCSS-aligned demands of audience, task, purpose, and discipline set forth by the creator of the visualization. Data visualizations give students a great opportunity to discern the target audience and whether the text is meant to inform or persuade.

Comprehending and critiquing

Everyone has opinions and everyone is exposed to others’ opinions. Through the analysis of data visualizations, students comprehend new information to help “understand precisely what an author or speaker is saying” (CCSSI 2017b). Students must determine and question the audience, purpose, and intent set forth by the creator of the visualization as they evaluate its credibility, accuracy, and effectiveness. Understanding the claim of the text and how it is (or is not) supported is crucial to student comprehension. Students can also critique student-created data visualizations.

Valuing evidence

Many conversations start with, “I was listening to,” or “I saw on,” or “I read online,” but rarely is the specific source remembered. We also sometimes tweak or exaggerate our evidence to better support our argument. Students must learn to cite specific evidence from a text/data visualization. Relevant evidence must be clearly presented to support their argument. They must also be able to constructively evaluate and assess others’ use of textual evidence.

Using technology and media capably and strategically

Students must use technology and digital media “thoughtfully to enhance their reading, writing, speaking, listening, and language use” (CCSSI 2017b) as they integrate what they learn from traditional texts with what they learn online. They must understand the strengths and limitations of the technological tools and digital mediums they choose to use and interact with. Creating data visualizations using tech tools gives students a great opportunity to determine which tool best delivers their message.

Understanding other perspectives and cultures

As more and more school curriculums reflect a world focus, students can develop an understanding of other perspectives and cultures by appreciating “that the twenty-first century classroom and workplace are settings in which people from often widely divergent cultures and who represent diverse experiences and perspectives must learn and work together” (CCSSI 2017b). The health and safety of our world depends on students’ active knowledge-gathering about those next door and across the globe. Students must be able to effectively communicate with people of diverse backgrounds and critically and constructively evaluate others’ varied points of views. Considering data visualizations created in other countries (look, for example, at international newspapers) gives students insight into other perspectives.

CCSS Learning Goals for Mathematics (Standards for Mathematical Practice)

Incorporating data literacy content into the mathematics curriculum helps students better understand how statistics and probability shape the information we are presented with daily and how the intent of a visualization can shape our understanding of content. Students can show understanding by creating their own data visualizations to justify a claim and then comparing their work with others’ work. Incorporating data visualizations can help develop skills that address several CCSS math standards in our students.

CCSS.MATH.PRACTICE.MP1: Make sense of problems and persevere in solving them

Students need entry points to begin to develop understanding of mathematical concepts. Introducing current, content-related data visualizations help generate student interest in problem solving. Interested students are better able to make meaning of a problem in order to analyze it, make conjectures from it, plan solutions for it, and consider analogous problems, while asking themselves, Does this make sense?

CCSS.MATH.PRACTICE.MP2: Reason abstractly and quantitatively

Students need to understand quantities and their relationships in many different contexts. Numbers represented visually (e.g., data visualizations) help students to decode the numerical information. Asking questions about the meaning of symbols, such as, “What is involved?” and “How many are there?” are necessary to gain competency in computation. Data visualizations not only provide the decontextualized information (symbols), but can also be easily contextualized (subject/content) to develop a better understanding of the visualization’s purpose and meaning.

CCSS.MATH.PRACTICE.MP3: Construct viable arguments and critique the reasoning of others

Developing questions about content and analyzing that content leads to discovering and justifying answers. By using inductive reasoning to identify and predict a trend in a graph, table, or chart, students can learn how to question and critique arguments by identifying the information’s flaws and strengths.

CCSS.MATH.PRACTICE.MP4: Model with mathematics

Data is and can be collected for just about anything. Students can compare what they already know to what they see to make new conclusions. Creating new data visualizations with newly student-collected information can confirm or deny an existing argument. Students can interpret data already being collected in many schools (i.e., the number of disposable trays used in the cafeteria per day, the number of library patrons counted per day, the number of water bottles saved per day by using the filtered water fountain) to determine whether the data makes sense or not based on assumptions they already have about their school. Students should “routinely interpret their mathematical results in the context of the situation and reflect on whether the results make sense, possibly improving the model if it has not served its purpose” (CCSSI 2017a).

CCSS.MATH.PRACTICE.MP5: Use appropriate tools strategically

There are many data visualization tools available to students, from simple graph paper to online statistics portals for finding and generating data visualizations from collected data. Students must choose the appropriate tool for the appropriate purpose. They must “use technological tools to explore and deepen their understanding of concepts” (CCSSI 2017a).

CCSS.MATH.PRACTICE.MP6: Attend to precision

Communication is successful only if it is precise enough to understand. Communicating through the presentation and creation of data visualizations (with appropriate and consistent labeling) can help students examine and present claims with accuracy and efficiency.

Data visualizations can do all that?

Many national standards can be addressed with content delivery through data visualizations. Don’t be overwhelmed. As with any new idea for curriculum delivery, applicable standards can be easily identified through a simple comparison of lesson goals and the content material that supports them. The “hard work” of identifying applicable standards has been done for you, so now it is your job (as a curriculum expert in your content area) to match the standards with your content and determine how you will deliver it to students. It isn’t hard – just think of data visualizations as variations of any traditional text that you are already using to deliver your content.

Though incorporating data visualizations is not only applicable to the mathematics curriculum, many of the statistics and probability concepts in math relate directly to how students decode, comprehend, and express information drawn from data visualizations. It is important that students have an understanding of the basic mathematical concepts presented in a data visualization. So many different types of data visualizations exist (and can be created) to express information from any content area. It may seem surprising that there are just as many English standards that can be addressed by content delivery through data visualizations as there are for math (if not more).

We know that standards are simply guidelines for excellent teaching, and to be excellent teachers we must continually reflect on and revise our content and its delivery. It is not necessary to include data visualizations in every lesson (as it is not necessary to address every standard in every lesson), but it is important to provide varied modes of content to ensure access to knowledge for different types of learners.

A 2015 study of secondary school students found that the preferred learning style was visual (45.7%), followed by auditory (21%), tactile (18.3%), and kinesthetic (15%) (Laxman, Govil, and Rani 2015). These findings support the incorporation of more visual learning experiences into the curriculum. Knowing our students’ preferred learning style best determines how we deliver content. Incorporating data visualizations such as charts, graphs, histograms, and infographics into any content area will lead to a better understanding of concepts and subjects that our visually-oriented high schoolers have previously found very difficult to understand (Laxman, Govil, and Rani 2015).

How does developing data literacy skills help students with standardized testing?

Today’s standardized tests require students to gather information from many different types of sources. Even within a single question there can be multiple modes in which information is presented. It is important for students to not skip over a data visualization because it is “just a picture.” Visualizations need to be “read” and understood. As we know, data visualizations can present information more quickly and more clearly than blocks of texts. Understanding how to read these “texts” can increase comprehension speed. As students better understand how to read, interpret, and comprehend data visualizations they will perform better on standardized tests that integrate graphs, charts, and tables into questions.

ELA testing

For the purposes of ELA testing, students do not need to understand how the data was collected or to determine the reliability of the data. Therefore, students do not need to apply the “Mind the GAP” strategy to data visualizations on these tests.

Students do need to be able to

- extract information from multiple forms of text

- make sense of that information, including synthesizing information found in text with that found in graphics

- determine how this information best answers the question. In fact, some questions require the student to “interpret graphics and to edit a part of the accompanying passage so that it clearly and accurately communicates the information in the graphics” (College Board 2017a).

What does that look like? Take a look at https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sample-questions/reading/6. This sample, which includes sample questions 6-8, is deemed appropriate for both SAT and PSAT practice. Students must interpret the bar chart and read the 526-word companion passage to answer the questions.

According to the College Board’s preparatory materials (College Board 2017b),

- The objective of the questions in this sample is to “reasonably infer an assumption that is implied in the passage.” This is a common objective for many questions on the SAT. Students need to find evidence in multiple forms of text (in a short amount of time) to answer the questions.

- Students have 65 minutes to complete the Reading test.

- There are 52 questions in the test.

This gives students an average of 1 minute and 15 seconds in which to process and answer each question. Therefore, building up students’ comprehension speed and ability to shift quickly between data and text is critical to their success.

For a sample ELA lesson you can use with your students with sample test questions and data visualization, please see Appendix F. For additional preparatory materials, the College Board (developer of the PSAT/SAT) provides free access to sample questions in all tested content areas at https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sample-questions/. Additional free online SAT practice is available through Khan Academy at https://www.khanacademy.org/sat. Many state tests provide access to online portals for students to practice sample questions. Consider accessing these resources to provide quick, daily classroom practice.

Science and standardized testing

Science standards still vary widely by state, but knowing how to draw meaning from graphed data is likely to appear on high school standardized tests. Appendix G provides sample teaching ideas related a released test question from the California Standards Test in Biology. In the sample, students must interpret the chart, a combination histograph/bar chart/scatter plot, to answer the question. This question requires students to find information from within an unfamiliar type of graph. Students must consider not only the length of each “bar,” but also the shape of the bar (in regard to its width at a specific point).

Additional subjects and standardized testing

A lesson to help high school students approach sample test questions for the California Standards Test in U.S. History is available in Appendix H. Appendix I provides ideas for approaching visualizations in math.

Differentiation in testing

Before we move to the next section of this chapter, a quick word about how to approach data visualization test questions with your students with disabilities. Be aware that students with disabilities and/or English language learners may qualify for standardized test accommodations. To be compliant with the Every Student Succeeds Act (ESSA), all states must provide alternative assessments to students if deemed necessary by an individual student’s individualized education plan (IEP) requirements (Advocacy Institute & Center for Law and Education n.d.). Check with your State Board of Education to determine the availability of alternative assessments and to determine how data visualizations are incorporated into those assessments.

So, now are you ready to incorporate data literacy instruction into your content area?

This chapter demonstrates how data literacy integration motivates different learner types, develops literacy skills, delivers content, addresses standards, and improves standardized test performance. All information needs to be questioned and reflected on before we can make an informed decision. Incorporating data visualizations into these conversations about “real world” issues sparks interest about and enthusiasm for classroom content.

To develop literacy skills among our diverse learners, we need to be flexible in how we deliver content. We can do this by utilizing a variety of teaching modalities, providing information that will overlap with information our students already have, and by reiterating and reinforcing information throughout a unit or during the course of a year (Friedman 2012, 11-15).

Integration of data visualizations into existing classroom lessons can help students to read, analyze, comprehend, and create information while addressing national standards. This type of integration better prepares our students to be able to extract information from multiple forms of text, in order to evaluate it and determine how the information best answers questions posed on standardized tests. These test questions contain claims (with supporting evidence) presented in charts, images, graphs, diagrams, tables, and text blocks. This data, in all forms, must be interpreted and understood in a prescribed amount of time to ensure success on all standardized tests.

Integrating data literacy into classroom learning is NOT about replacing your content, changing your teaching style, or dumbing things down. Integrating data literacy into your classroom is about supplementing your content, amplifying your teaching style, and developing inquiry learners. Because having the power to gain knowledge and make informed decisions means students understand data and where it comes from, are able to extract data from charts, graphs, tables, and other types of visualizations, and can present data as evidence to make a claim. Numbers representing any type of statistic can be used in any content area — from the breakdown of a college student’s budget, to water pollution, to the Olympic medals won over time, and even to theatrical deaths. Data representation can take place in many forms from traditional texts to data visualizations. Data is information and information helps our students to better understand content.

Resources

- Advocacy Institute and Center for Law and Education. n.d. “Our Kids Count: ESSA & Students With Disabilities.” The Advocacy Institute. Accessed March 26, 2017.http://www.advocacyinstitute.org/ESSA/SWDanalysis.shtml.

- California Department of Education. 2009. “Released Test Questions: Introduction – Biology.” California Standards Test. Accessed March 26, 2017. http://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/tg/sr/documents/cstrtqbiology.pdf.

- College Board, The. 2014. “Founding Documents and the Great Global Conversation.” The College Board. Accessed March 26, 2017. https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/pdf/founding-documents-great-global-conversation.pdf.

- College Board, The. 2017a. “Key Content Features.” The College Board. Accessed March 26, 2017. https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sat/inside-the-test/key-features

- College Board, The. 2017b. “Sample Reading Test Questions.” Official SAT Study Guide. College Board. Accessed March 26, 2017. https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/pdf/official-sat-study-guide-ch-12-sample-reading-test-questions.pdf

- College Board, The. n.d. “Sample Questions: Introduction.” The College Board. Accessed March 26, 2017. https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sample-questions.

- Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI). 2017a. “Standards for Mathematical Practice,” Common Core State Standards Initiative. Accessed March 26, 2017. http://www.corestandards.org/Math/Practice/.

- Common Core State Standards Initiative (CCSSI). 2017b. “Students Who are College and Career Ready in Reading, Writing, Speaking, Listening, & Language.” Common Core State Standards Initiative. Accessed March 26, 2017. http://www.corestandards.org/ELA-Literacy/introduction/students-who-are-college-and-career-ready-in-reading-writing-speaking-listening-language/ .

- Dee, Johnny. 2013. “Romeo And Juliet: Everything You Need To Know - Infographic”. The Guardian. Accessed March 26, 2017. http://web.archive.org/web/20140513090230/http://www.theguardian.com/culture/picture/2013/oct/11/romeo-and-juliet-infomania .

- Greenleaf, Cynthia. WestEd. 2014. “Apprenticing Adolescents to Academic Literacy in the Subject Areas: The Reading Apprenticeship Instructional Framework.” Reading Apprenticeship/WestEd, Mar. 20. Accessed March 26, 2017. https://readingapprenticeship.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/04/Apprenticing-Adolescents-to-Academic-Literacy-in-the-Subject-Areas-The-Reading-Apprenticeship-Instructional-Framework.pdf .

- Friedman, Bruce D. 2012. How to Teach Effectively: A Brief Guide, 2nd ed. Chicago: Lyceum Books.

- Gilmartin, Kathleen, and Karen Rex. 1999. “Student Toolkit 3: Working with Charts, graphs, and Tables.” The Open University. Accessed March 27, 2017. http://www2.open.ac.uk/students/skillsforstudy/doc/working-with-charts-graphs-and-tables-toolkit.pdf.

- Gosling, Mya. 2015.“The Romeo and Juliet Death Clock,” Peace, Good Tickle Brain (blog). August 26. Accessed March 27, 2017. http://goodticklebrain.com/home/2015/8/26/the-romeo-and-juliet-death-clock .

- Laxman, Singh, Punita Govil, and Rekha Rani. 2015. “Learning style preferences among secondary school students.” International Journal of Recent Scientific Research 6 (5), 3924-3928. 3924-3928. http://www.recentscientific.com/sites/default/files/2411.pdf.

- Moje, Elizabeth Birr. 2006. “Motivating texts, motivating contexts, motivating adolescents: An examination of the role of motivation in adolescent literacy practices and development.” Perspectives 32 (3), 10-14). Accessed March 26, 2017. http://305089.edicypages. com/files/MotivatingTextsMotivatingContextsMotivatingAdolescents.pdf.

- Nester, Hannah. n.d. “Infographic: 10 Things You Should Know About Water.” Circle of Blue. Accessed March 26, 2017. http://www.circleofblue.org/2009/world/infographic-ten-things-you-should-know-about-water/.

- Sweetser, Shannon. 2010. “22 Mind-Blowing Infographics on Education,” Socrato! Learning Analytics Blog. November 4, Accessed March 26, 2017. http://blog.socrato.com/2-mind-blowing-infographics-on-education/.

- Rost, Lisa Charlotte, and Alyson Hurt. 2016. “How The Olympic Medal Tables Explain The World.” The Torch blog/NPR.org, August 6. Accessed March 26, 2017. http://www.npr.org/sections/thetorch/2016/08/05/488507996/how-the-olympic-medal-tables-explains-the-world.

- WestEd. 2017. “Reading Apprenticeship.” WestEd. Accessed March 26, 2017. https://www.wested.org/project/reading-apprenticeship/.

Appendix B: Integrating an infographic about Romeo and Juliet into the ELA classroom

Visit “Infomania Fact-checking the famous: Romeo and Juliet.” While originally published in December 2016 by The Guardian online, this is now archived at http://web.archive.org/web/20140513090230/http://www.theguardian.com/culture/picture/2013/oct/11/romeo-and-juliet-infomania .

This infographic does not document the deaths in Romeo and Juliet but instead pulls data from the text to compare the author, themes, main characters, and references to current events and movies. It’s not just a poster about the tragic story of two star-crossed lovers: it’s the research process in visual form.

Before you ask your students to create their own infographics, a useful activity is to unpack an existing infographic to help students understand its intent, what claims it makes, and its success in doing so.

Appendix C: Integrating an infographic about water into the science classroom

Visit “Ten Things You Should Know About Water” at http://www.circleofblue.org/2009/world/infographic-ten-things-you-should-know-about-water/ .

If you have 30 minutes,

Use the “Mind the GAP” strategy outlined in Appendix A.

If you have one class period,

Ask students to:

- Determine the claim of the text. This text highlights the value of water, how it is used, and how easily it can become polluted.

- Determine how it is presented. Is it meant to inform or persuade? This text is meant to convince the reader that water is a valuable and scarce resource.

Identify supporting evidence and engage students in “Mind the GAP” conversations:

- Genre – This text is visually representative of an infographic as defined in Appendix B.

- Audience – By looking at the sources of information at the bottom of the text, students can determine if the information is from a reliable and authoritative source. This helps determine if the intended audience is a scholarly or casual. Students can also go to the Circle of Blue website (http://www.circleofblue.org) and look at the organization’s “About” page. This will help students understand if this organization has a political agenda, constituency, or point of view. A visual scan of this infographic helps determine the intended audience. The look and language is formal, yet it is still approachable and understandable for most high school readers. The intended audience is anyone who can understand the science behind the claims being made.

- Purpose – The purpose of this text is to provide information in such a way that the reader becomes persuaded that water should be conserved. The title of the infographic is a discussion starter to determine if the text is meant to inform or persuade. Why should the reader know these facts about water? What’s the purpose for sharing these ten pieces of evidence? Should water be conserved? If so, why?

If you have multiple class periods,

Compare the information found in a more traditional text to information in the data visualization by:

- Providing students with textbook information or a pertinent article for use as comparison. Or, in the case of this specific infographic, students can compare the text on the Circle of Blue website to the visualization.

- Asking students to find the visualized information within the traditional text to determine if the facts are represented accurately in the infographic. Students could also search online to find other reliable sources that confirm or disprove the infographic’s information. This can be accomplished through talking to the text, close reading, and/or using the search tool COMMAND+F (on a Mac) or CTRL+F (on a PC) to search for words and phrases in a digital document. For example, how much of Earth’s water is used for agriculture? What percentage of Earth’s water is salt versus fresh? How much water is used to produce different products? etc.

- Asking students to compare how claims are made and supported by each type of text. For example, students could study the water cycle within a traditional text to make inferences and connections as to why the infographic claims may or may not be accurate and supportable in reference to what they already know (or are learning) about the natural processes of Earth.

If you have an entire unit,

Refer to the unit-length strategies in Appendix A.

Appendix D: Integrating an infographic about the Olympics into the social studies classroom

Visit “How The Olympic Medal Tables Explains The World” at http://www.npr.org/sections/thetorch/2016/08/05/488507996/how-the-olympic-medal-tables-explains-the-world .

Appendix E: Integrating an infographic about budgeting into a math classroom

Visit “Breakdown of Average Student Budget” (#5 at http://blog.socrato.com/2-mind-blowing-infographics-on-education/).

Appendix F: Using a sample assessment question for an ELA classroom

Please access https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sample-questions/reading/8 for this activity.

Appendix G: Using a sample assessment question for a science classroom

Please access http://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/tg/sr/documents/cstrtqbiology.pdf and find question 73 (p. 25) for this activity.

Appendix H: Using a sample assessment question for a social studies classroom

Please access http://www.cde.ca.gov/ta/tg/sr/documents/cstrtqhssmar18.pdf for this activity.

Appendix I: Using a sample assessment question for a math classroom

Please access https://collegereadiness.collegeboard.org/sample-questions/math/calculator-permitted/20 for this activity.