Life Writing in the Long Run: A Smith & Watson Autobiography Studies Reader

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

2. The Rumpled Bed of Autobiography: Extravagant Lives, Extravagant Questions (2001)

Preface

Our edited collection, Interfaces: Women, Autobiography, Image, Performance, responded to the remarkable outpouring of self-portraiture in contemporary painting, photography, artists’ books, and mixed visual forms such as installations, collage, and quilting that marked autobiographical inquiry in the United States, Canada, Great Britain, Ireland, France, Germany, and elsewhere in the later twentieth century. In autobiography courses each of us began using slides of visual self-portraits to enliven discussion and dramatize difficult conceptual issues of self-representation in women’s autobiographical narratives that were linked to the explosion of innovative work in visual and performance fields. Indeed, some aspects of gendered self-presentation, such as embodiment, are explored and resolved in strikingly different terms in visual and performance media than in written narratives.

The installation of a British performance artist, Tracey Emin, at the Tate Gallery in London caught our eyes because it both flaunted and troubled the question of autobiographical acts by probing the boundaries of “life” and art. Emin’s work exemplifies several controversies about autobiography and raises provocative questions for both visual and verbal autobiographical narratives. But those questions are not restricted to the space of the museum, gallery, or video screen, as our subsequent discussion of a recent American memoir, Dave Eggers’s A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, will suggest. Through reading an installation and a memoir side by side as examples of experiments in autobiography at this cultural moment, we want to foreground the gendered politics and ethics of life writing at the edge of life writing studies.

Although works such as Emin’s and Eggers’s, which dramatize and flaunt autobiographical conventions, may well be at the outer limits of the practice of memoir in the year 2000, they are important for autobiography scholars who wish to interrogate the limits of autobiography at a time when “the rule” is breaking the rule. Hence the suggestion in this essay’s title that the procrustean bed of autobiography is now inescapably a rumpled one—much slept in; still warm, if soiled; and haunted by conspicuously absent bodies.

While Emin’s performance piece evoked the metaphorics of the rumpled bed for us, the “bed” of autobiography has also been explored by Alison Donnell in an essay on women’s contemporary autobiographical practices:

The explosion of criticism surrounding autobiography, and particularly women’s autobiography, over the last twenty years, has demonstrated that as a genre autobiography can be likened to a restless and unmade bed; a site on which discursive, intellectual and political practices can be remade; a ruffled surface on which the traces of previous occupants can be uncovered and/or smoothed over; a place for secrets to be whispered and to be buried; a place for fun, desire and deep worry to be expressed. Many of the most influential women writers of the twentieth century have chosen to make this bed and some to lie in it too. (124)

Rumpled, unmade, at this contemporary moment the bed is a generative metaphor for approaching contemporary experiments in self-presentation that mix a grab-bag of autobiographical modes, tropes, and histories. Paradoxically, the autobiographical is a conspicuous staging arena for the public world, if one with a foot lingering in the intimate bed of the personal.

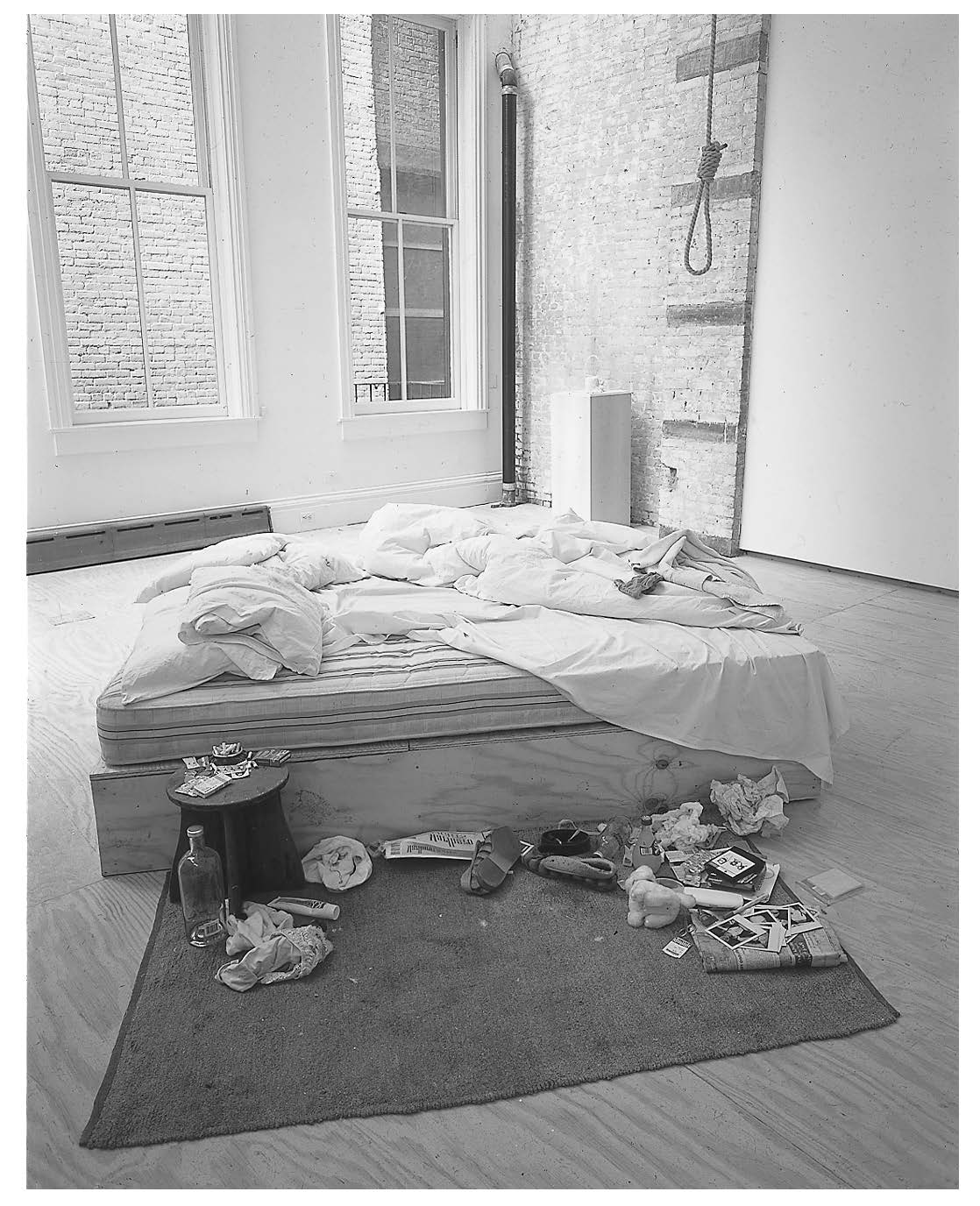

Tracey Emin’s “My Bed” and Autobiographical Performance

In 1999 Tracey Emin, a young working-class British artist, was one of four finalists for the prestigious Turner Prize awarded by the Tate Gallery in London.[1] Emin’s submission to the Tate Gallery was explicit autobiographical memorabilia. It consisted of eight home videos, four miniature watercolor portraits, a wall of captioned drawings made during her adolescence, a quilt collage, and two assemblages, one of them evoking the memory of an uncle killed in an automobile crash. At the center was the installation “My Bed” (1998), a rumpled bed with stained, tossed sheets surrounded by overflowing ashtrays, used tissues and condoms, unwashed underwear, and medicine bottles—all the detritus of her intimate life in Berlin in 1992–93, as the caption made clear.

The photograph of the installation prominently displays a coiled rope hung from a gibbet-like hook in the background, giving the scene a sadomasochistic, if not suicidal, nuance. In fact, the rope was not part of the Tate installation when we saw it. After two young men, apparently confusing art and life, jumped on the bed, it had to be roped off from the public. Subsequently, the rope, as part of the history of exhibiting “My Bed,” was included in the installation.

Emin’s assemblage enacts multiple autobiographical performances in both visual and verbal media, and suggests their permeable interface. The bed becomes a memory museum to a specific time and place in Emin’s past. Similarly, her labeled drawings comprise a kind of artist’s diary on adolescent sexuality, with comments such as “I don’t know what I want to do”; “What it looks like to be alone”; “I didn’t say I wasn’t scared. I said I’m not as scared as I used to be.” With their misspellings and awkward phrasing, the doodles and childlike images create the sense of unedited and unpolished immediacy. Such immediacy accords a sense of “authenticity” to her lived experience of those moments in her past.

My Bed, 1999. 2016 Tracey Emin. All rights reserved, DACS, London / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York.

Emin’s videos of summer vacations and high school days also catalog a young woman’s self-representational possibilities as experiments in modes of self-chronicling. “My C.V. . . . (to 1995),” for instance, offers a deadpan recitation of sets of facts and yearly events, among them that she tried to commit suicide in 1982, and that she had two successive abortions in two years in the early nineties. Her C.V. entry for 1995 includes her reminder to herself to “Plan the Tracey Emin Museum.” This voiceover recitation of a “curriculum vitae” is accompanied by a visual walkthrough of a “home” (with toilets, beds, a sitting room) that may be hers or her mother’s. Another video presents a narrative of childhood, chronicling her adolescent sexual encounters, predominantly of a violent character, with working-class boys on the streets of her hometown, and her eventual escape from small-town hypocrisies and brutality. In another video, a seeming home movie captures the daughter and her father playing in the waves of a Cyprus beach. Yet another video, its title invoking Edvard Munch’s painting “The Scream,” shows a young woman drawn up into a fetal position clinging to a boardwalk. The image, shot from overhead, has as its soundtrack only a sustained scream. A traumatic memory, perhaps one linked to abortion or sexual abuse, is here visualized outside language. The sound of the scream punctures the silent image but gives no interpretive narrative of it. We are left to make our own surmises about the experiential pain expressed.

Deploying medium upon medium in this chronicling of moments in her life, Emin insists on the autobiographical as her artistic origin, performative identity, and preferred mode. For some viewers, her work exceeds self-portraiture in what they see as its narcissistic self-absorption, referring line, color, form, and sound back to the emotions of her experiential history. For others, including the many young people who thronged her installation day after day, Emin’s work introduces, through the interweaving of images and written text, an autobiographical voice not previously heard or witnessed with such intensity. In that sense, her daring self-making as self-chronicling is an avant-garde gesture, expanding the modes of self-representation at a shifting matrix of publicly performed visuality and textuality. In this rumpled bed of autobiographical presentation, the material imprint seems to be at once monovocal, even solipsistic, and, at the same time, boldly inventive. Emin’s work, balanced at the interstices of everyday life and an artistic avant-garde, is a convergence of anti-art and extreme artistic self-reference. No wonder that her work provoked controversy.

Emin’s foregrounding and exploiting of the autobiographical suggests that it has been a foundational discourse for artistic production at the end of the twentieth century. But her insistence on palpable self-reference has annoyed many in the British art world, who for years have criticized her work as narcissistic, trivial, and unimaginative. “My Bed,” following as it did upon her 1997 exhibition, a tent called “Everyone I Have Ever Slept With, 1963–95" (sold recently for £40,000), particularly provoked debate about the aesthetic value of a bed with soiled sheets surrounded by crumpled tissue and used condoms. David Lee, former editor of Art Review, summarizes this critique: “She can’t paint, she can’t draw and she can’t sculpt. . . . ‘My Bed’ is stillborn artistically”; noted international collector Charles Saatchi, however, who paid £150,000 for “My Bed,” stated “I was very slow to get the loopiness of Tracey’s work, but I’m a helpless fan now” (both quoted in Brooks 7). Emin’s provocative use of the material of her life, rather than an interpretation of it, as autobiographical suggests that the procrustean bed of self-reference is now being performed at a site of rumpled, disorderly, stubbornly literal artifacts that refuse remaking as “art.” But it is simultaneously an extreme of the avant-garde.

In the practice of life narrative at this cultural moment, how much difference is there between the practice of citing one’s past utterances and including memorabilia of the past, and performing that past as an experiential history? That is, how do we describe the difference between selected quotation of one’s past moments in such memorabilia as objects and diaries, and the performance of that past as memory work? Does Emin’s “art” reside in her pastiche of multiple modes that artifactually document her life? In her evocation, simultaneously, of many different moments of her experiential history? Does her making of art reside in framing moments that, when they occurred, were without self-consciousness? The single frozen moment of “My Bed” asks spectators to pose the question of “art” differently, to inquire about an absent subjectivity whose traces surround us. Does Emin’s work require us to interrogate spectatorship, moving from consumption of the art object to uneasy speculation about subjectivity? If a rumpled bed asks to be read as an autobiographical signature, what could viewers do to make a pact between the covers with its author?

“Keeping It Real”: Rumpling the Memoir

In performance and much visual art, the autobiographical bed is certainly a rumpled one. Emin’s insistent, excessive self-referentiality troubles the “rules” of social decorum about the appropriate location of the materials, activities, and behaviors of a young woman’s quotidian life. It threatens the boundaries that normally distinguish everyday life from “art.” The rumpled bed of autobiography is not on display only in the visual arts, however. It is on display even when its narrators are resting—lying?—between the covers of a book. Like Emin, an inventive new group of Gen X writers schooled on zines and the Web frequently enmesh and deliberately confuse the boundaries of fiction and memoir, exploiting the terms of the “real.” Under siege in such literary memoirs are what an earlier generation of critics regarded as the normative rules of autobiography. In this moment of a paradigm shift between analog and digital cultures, between the book and fluid hyperspace, the autobiographical has become a moving target of experimentation. Think of the airing of family “dirty linen” in memoirs by Mary Karr (The Liars’ Club), Kathryn Harrison (The Kiss), Elizabeth Wurtzel (Prozac Nation), Michael Ryan (Secret Life), and Lauren Slater (Lying: A Metaphorical Memoir), and of the autobiographical discourse embedded in the novels of Kathy Acker and Don DeLillo. These writers both depend on and undermine expectations of sincerity, authenticity, intimacy, and completeness long hailed by critics and readers as essential to the autobiographical pact.

Enter Dave Eggers with a memoir, A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, subtitled “based on a true story.”[2] Eggers’s (the writer’s) narrative chronicles the lives and fortunes of a pair of brothers after the deaths, several years earlier, of both parents, within thirty-two days of each other. A narrative of trauma, then? Or perhaps not. Dave (the narrating I), then twenty-one and unwilling to surrender the familial structure and make his seven-year-old brother, Toph, a ward of the state after the catastrophe, resolves to raise him himself, with the help of other grown siblings. In effect, Dave and Toph refuse to be defined as orphans, and recompose themselves instead as a new-model family with Dave, in his version, assuming the roles of both maternal nurturance and paternal authority.[3] They thereby implicitly dispute the conservative model of the two-parent family as necessary to prevent the breakdown of moral values. Eggers’s narrative reflects not only on the constraints of normative family life in contemporary America—drawn from experiences in Chicago and Berkeley—but on the complexity of roles that Dave must take up as brother and son, parent and child, lusty young male and moral arbiter, would-be artist and postmodern cynic.

Eggers is acutely aware that the contradictions of his multiple identities pose a dilemma for the tidy memoirist. In his hands the narrative becomes an occasion to both flaunt and test autobiographical conventions of the boy’s-coming-of-age story. Celebrated in the memoirs of Tobias Wolff (This Boy’s Life) and Geoffrey Wolff (The Dukes of Deception), this American tradition stretches back through Richard Rodriguez (Hunger of Memory), N. Scott Momaday (House Made of Dawn), Richard Wright (Black Boy/An American Hunger), and Thomas Wolfe (You Can’t Go Home Again) to Mark Twain (Days on the Mississippi), Frederick Douglass (Narrative of the Life of Frederick Douglass), and Benjamin Franklin (Autobiography). Like Emin’s installation of her intimate history, Eggers’s rumpling and remaking of autobiographical convention is a bold intervention in coming-of-age narratives, although their gendered histories, particularly as sexually licentious “boy” versus sexually victimized “girl,” are differently inflected. But whereas Emin’s memorabilia are presented without a present-tense critical narrative to frame them, Eggers calls attention to his “messing” with the memoir by prefacing his narrative of the new-model family with an elaborate apparatus of explanation and justification. We focus on that set of introductory texts.

Like a Cervantes novel, A Heartbreaking Work includes nearly forty pages of advice on how to read its narrative of loss and survival. Its introduction is divided into “Rules,” a Preface, Contents, extensive Acknowledgements, and an Incomplete Guide to Symbols and Metaphors; there are also “outtakes” printed on the book’s front end flap. In other words, the analytic conventions of the scholarly book are assembled to self-consciously frame a first-person narrative that announces itself as “a work of pure non-fiction” (ix), “a memoir-y kind of thing” (xx).[4] In these prefatory sections Eggers situates his narrative as autobiographical in ways more reminiscent of the metafiction of Sterne’s Tristram Shandy and the stories of Cortázar and Borges. This elaborate set of introductions both draws readers in and warns about the traps of sincerity and authenticity in personal narrative.

The book is complexly framed, beginning with its cover and end flaps. The cover, with its outrageously egotistical title, a calculated oxymoron of shattering trauma and arrogant genius, signals its staging of an exceptional “I,” as does the jacket illustration of a red theatrical curtain half-drawn back to reveal the last rays of the setting sun, a worn cliché of Romantic genius. The book, then, announces itself as a hyperbolic performance of egotism rather than the assumed modesty of the memoirist’s self-presentation. Similarly, in the hardback edition the front jacket flap defies readers’ expectations by offering not an overview of the book, but a section “removed” from chapter five, without beginning or ending. Although the back flap seems more conventional in its snapshot of the T-shirted Eggers with dog, a brief paragraph identifies “the author” as the editor of a zine now living in Brooklyn with his brother, but adds “And this is not their dog.” In this gaming with the self-referentiality of the memoir, Eggers reproduces and violates its conventions of sincerity.

In the book’s first pages, readers are advised that it is possible, and probably a good idea, to skip the lengthy sections of prose and the elaborate Table of Contents that preface the narrative. This warning not to read the book, familiar from Rabelais, Montaigne, and a host of other meta-autobiographers, both teases and provokes. The next section, “Rules and Suggestions for Enjoyment of This Book” (vi), couched in the royal “we,” contains six numbered items listing what readers may skip, ultimately most of the book. But the “rules” also make clear the dilemma of self-interested autobiographers whose readers don’t share their enthusiasm for their lives. Suggesting that readers skip a hundred pages on Dave and his twenty-something friends, the Preface notes, “those lives are very difficult to make interesting, even when they seemed interesting to those living them at the time” (vii).

The “Preface to This Edition” (this edition being the first and only) confesses to several kinds of fictionalization within a “non-fictional” memoir, and points up the arbitrariness of the genre’s conventions. Although particular to Eggers’s narrative, these warnings about autobiography’s fictions suggest contradictions in the autobiographical pact itself. Dialogue, above all, is suspect. Eggers asserts that his dialogue has been almost entirely reconstructed so as to “manufacture” the true-to-life quality it has in the book (ix). He notes that characters’ names have been altered and their qualities changed because they, as living subjects, for the most part demanded some concealment. When, occasionally, no fabrication has been made, he calls attention to it directly, as in “You can ask her. She lives in Southern California” (x). The narrator, then, in emphasizing the text’s verisimilitude, also troubles it. Eggers notes that locations and dates or times have been switched; that no relationship to subsequently occurring “real” events, such as the Columbine shootings, was intended; and that what the narrator cut from the manuscript can be recouped in the section on the front jacket flap. By highlighting its rearrangements and masking of experiential history, the narrator asserts the “truth” of his tale. The apparent lack of contrivance in most memoirs, by contrast, is implied to be a deeper kind of contrivance.

Similarly, Eggers’s elaborate Table of Contents is a two-page Shandy-esque mixing of the substantive with the cryptic, irreverent, irrelevant, and inconsequential. The Acknowledgements, dedicated to NASA, the Marine Corps, the United States Armed Forces, and the United States Postal Service—large, anonymous groups—are also a send-up of the memoir genre. “The author, and those behind the making of this book,” the narrator announces,

wish to acknowledge that yes, there are perhaps too many memoir-sorts of books being written at this juncture, and that such books, about real things and real people, as opposed to kind-of made-up things and people, are inherently vile and corrupt and wrong and evil and bad, but would like to remind everyone that we could all do worse, as readers and as writers. (xix)

While Eggers here makes readers exhaustively aware of bothersome questions of the “real” in autobiography’s imperfect miming of it, his advice for readers with memoir trouble is equally ironic: “Pretend it’s fiction” (xxi).

If autobiography imperfectly stages experience between the covers of a book that embeds his narrator Dave, Eggers steps forth to address the reader outside the memoir’s illusion of a coherent past, inviting readers unhappy with the memoir to return it to the publisher in exchange for a floppy disk of same. In an ultimate send-up of autobiographical self-interest, readers are assured that the disk will function interactively, so they can search-and-replace the names in the book with their own and those of their friends: “This can be about you! You and your pals!” (xxii).[5]

Eggers also exploits self-advertisement as an aspect of autobiographical writing. He makes an immodest case for Dave’s appeal with an extensive list of his personal characteristics, assuring readers that he is someone “like” you. There follows a list, in twenty-two exhaustive descriptions, of the memoir’s themes, above all, “the painfully, endlessly self-conscious book aspect.” In this labyrinth of self-assertion he claims that he is “clearly, obviously aware of his knowingness about his self-consciousness of self-referentiality” (xxvi-xxvii). But lest the verbal fireworks seem celebratory, Eggers reminds us of the memoir’s theme of “weirdly terrible” deaths as a way of being “chosen” and its relation to “the search for support, a sense of community” (xxvii). The book’s themes are concisely summarized in a graph published on one page and available in large format for five dollars through the mail. Not only does Eggers elaborately gloss his narrative, but he generates, graphs, and meta-critiques the range of possible critical approaches to it.

But this elaborate critical apparatus for seemingly controlling the reading of his memoir and proving his encyclopedic awareness of autobiographical convention is, Eggers asserts, in fact “gimmickry.” It is in the service of obscuring “the black, blinding, murderous rage and sorrow at the core of the whole story,” a story whose center is the stricken heart of childhood loss and trauma (xxvii). Assuming the other privileges of the memoirist, Eggers confesses and therapeutically exorcises his pain by the practice of testimony: “Telling as many people as possible about it helps” (xxvii). In such an ironic set of prefaces, how are we to value this assertion of a central self shattered by trauma? Eggers acknowledges the paradox of telling the heartbreaking story of a childhood riven by illness and death in order to exploit it for fame and profit and to “receive . . . a thousand tidal waves of sympathy and support” (xxvii). Publishing a memoir, Eggers acknowledges, is finally an “act of self-destruction,” much like an emetic or the shedding of a skin (xxx). Yet self-revelation is also “endlessly renewable,” an act of feeding solipsism but justified by the desire, through writing, to create an enduring relationship with his brother Toph, who has been both “inspiration for and impediment to writing of memoir” (xxxi). Posing “self-aggrandizement” against “self-flagellation” as the motives of autobiographical writing and its search for “self-canonization,” Eggers’s performance of memoir-writing is profoundly ambivalent. It suggests, finally, that being suspicious about the ethics of autobiographical writing may be the one ethical act available to it.

The Acknowledgments conclude with that most mystified, yet essential, aspect of autobiographical writing in our postmodern times, the material specifics of Eggers’s financial arrangements with his publisher. Provocatively he invites the reader to participate in profiting from the pain of his memoir. Listing his relatively low costs and high profits (over $60,000 in advance for the book, before sales), Eggers promises a five-dollar check to the first 200 readers who “write with proof that they have read and absorbed the many lessons herein,” and includes his editor’s name and address (xxxv). Instructions are included on how to provide credible photographic proof that one has read the book.

Bringing this elaborate foreplay of almost forty pages to an end, Eggers provides “an Incomplete Guide to Symbols and Metaphors” in the narrative “to save you some trouble” and get on with the reader’s desire for “uninterrupted, unself-conscious prose,” for the pleasure of reading (xxxvi-xxxvii). As he summarizes the range of autobiographical excesses that have haunted the genre’s practitioners—a propensity for exaggeration and lying, a lack of unique experience—we are reminded that he also has the good fortune to be under contract for what others must suffer silently.

In so elaborately sketching the rules of the memoir game, Eggers simultaneously underscores and undermines them. Claiming to tell a true story in a genre about whose maneuvers he is acutely, endlessly self-conscious, he invites readers to confront the undecidability of autobiographical acts. Is Eggers’s calculated miming of memoir merely a bid for readerly sympathy? Or is his conceptual apparatus intended to distance and defer the inconsolable pain of traumatic familial experience? Like Emin’s rumpled bed, Eggers’s rumpled memoir gestures toward the excesses of embodied experience, now past but still palpable, that refuse containment by the disciplining power of autobiographical conventions.

And the controversy continues, after the publication of A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius, in e-mail and zine wars about the status of the “real” and the sincerity of Eggers’s ethos. A recent Harper’s Magazine excerpted Eggers’s elaborate “Addendum” to one of these dialogues, in response to a question from The Harvard Advocate (Summer 2000), which, concerned about his success and willingness to write for major magazines, asked “Are you taking any steps . . . to keep shit real?” In a long rant about “selloutitude,” Eggers explains that the book’s success and the other writing work it has netted him, as well as the prospect of its becoming a major motion picture, are not sellouts but indications of his lack of calculation in response to his own success. “I really like saying yes. . . . The keeping real of shit . . . [i]t’s fashion, and . . . fashion doesn’t matter” (“Too Legit” 24). Again he attempts to expose the audience’s perceived demand for uncalculated sincerity as posturing, a false pose. He has gained media attention, he argues, because he is unself-consciously alive and in the moment, not because he works at being authentic. “Keeping it real” in an age of simulacra is, he suggests, at best an anachronistic naturalism. Eggers’s “real,” by contrast, is interested in play and engagement, inhabiting what’s happening now. Like Emin, Eggers keeps moving into a new “now” in which past memories are cited, staged, as the material for present ways of making visible an evanescent subject.

Extravagant Lives, Urgent Questions

Placing Emin’s and Eggers’s extravagant performances of the conventions, limits, and apparatus of autobiographical acts side by side suggests several questions about the uses of autobiography at this cultural moment. First, there are issues about experimental life writing. How may the autobiographical be a style of avant-garde experimentation? And how is autobiographical avant-gardism differently enacted in alphabetic, visual, and performance modes? What are the particular terms of avant-garde experimentation in autobiographical writing at this juncture? To what extent is the confounding of experiential history and its representation as the “real,” or a “life,” more compelling in this time of simulated realities—on television, in everyday life, and in cyberspace? How does the embodied materiality of visual and performance media reframe “art” as a site of lived experience, and turn daily life into material for performance?

A second issue concerns the gendered ethics of autobiographical acts. The autobiographical pact implies that writers seek to maintain a sincere and responsible relationship to their audiences and to the ethical imperatives of that relationship. But these artists probe the limits of sincerity through extravagant performances that flaunt the norms of modesty about self-disclosure, self-presentation, and experiential history. In Emin’s work, the seemingly excessive disclosure of her personal past presented through installations, diaries, and videos could be read as both exploiting and flaunting gendered norms of female decorum. Nice girls, well-brought-up-girls, simply do not rehearse their intimate lives in public, let alone display the sordid leavings of them. Emin’s public presentation of intimacy seems to mimic the stereotype that those of working-class origin are less concerned about decorum than the middle class. Similarly, Eggers’s narrative seems to violate norms of masculinity by remaking the post-traumatic family as an all-male world of nurturance and bonding, resituated in the private domain of home and family, yet exploiting conventional norms of gendered roles to retain male authority. But if Eggers’s narrative marks out a public-private boundary, his flamboyant framing and publication clearly transgress it.

In different ways, then, both of these works are extravagant performances of experiential history that interrogate gendered norms and redefine the spaces and roles normally assigned to men and women. And they adduce confusion on the part of audiences about how to respond. In Emin’s case public outrage at the scandal of her extravagant performance was perhaps intensified by her working-class frankness in the bourgeois public sphere of the Tate gallery. Eggers’s extravagant claim to remake the form of the memoir as a work of “genius” in the service of the family memoir is a similarly hyperbolic bid for readership.

A third issue concerns the autobiographical pact, that “contract of identity . . . [between writer and reader] sealed by the proper name” (Lejeune 19). What effect do such extravagant performances of the asserted “real” have upon our conception of an autobiographical pact in which, in Lejeune’s terms, the “essence of [a] being is registered” (21)? The pact implies a kind of decorum in the writer’s limiting of self-exposure before readers, as a guarantee of the narrator’s reliability. In different ways, Emin and Eggers both maintain and breach these terms in order to renegotiate what is permissible in the name of public presentation of one’s past. As a result, both autobiographical actors are seen by some as shameless self-advertisers, excessively and flagrantly exposing themselves, selling out and betraying the presumed desire of their works to capture the “real.” Precisely because the work of both Emin and Eggers has been widely acclaimed and they have become causes célèbres, they may be mobilizing something in audiences that more discreet autobiographers have not tapped. People flocked to Emin’s spectacle. Readers acclaim Eggers’s memoir. Both artists have become financially successful. Autobiographical exploiters and sell-outs? Or avant-garde experimenters pushing the limits of disclosure in the form, and tweaking the cultural establishment all the way to the bank? The popularity, in the last few years, of these works reminds us that the autobiographical has historically consisted of popular forms consumed by reading publics hungry for intimacy and vicarious adventure. If academic critics want to say “no” to excessive and repeated self-display, the enthusiastic public response to these extravagant presentations of “lives” has been “yes.”

Finally, consider the stakes of these autobiographical acts. What is Emin’s extravagant multimedia autobiographical performance interested in achieving with such public exposure? Is it clearing a space in the bourgeois public sphere for an unattractive, working-class female bad-girl artist? Is this visual excess the equivalent of obsessive confession in the talk show, or of disclosure on the psychiatrist’s couch? Is it, as her critics allege, the calculated act of a woman poor in imagination ransacking her private life for titillating details to be packaged and marketed as a new avant-garde, solely because of their anti-art rawness? Is Emin, then, the kind of performance autobiographer Linda S. Kauffman has termed a “bad girl” for the unflinching exploration of her own archive (56)? For Kauffman, such artists “stage their own bodies as sites of contestation through parody, defamiliarization, and incongruous juxtaposition” (60). Emin, however, is staging—if indeed she is staging, not just citing—something other than her adult take on public uses of and responses to women’s bodies in the fantasies of contemporary culture. Rather, she presents the idiosyncratic particularity of her own past, one often at odds with both decorum and parody. In including her bed, her childhood diaries, her vacation videos, family news clippings, and other artifacts of her experience as art, Emin seems to undermine the notion that the autobiographical selects, edits, chooses, and rearranges the stuff of life into meaningful narrative, reworked by memory’s intervention, for public scrutiny. And yet, in presenting these fragments of the past as art, Emin invites us to remake her in the present, to compose interpretive narratives, to collaborate in constructing the indisputable authenticity and flagrant excess of her autobiographical acts.

By contrast, what is Eggers’s autobiographical narrative, with its elaborately self-conscious glosses and extravagant literary parodies, interested in making of autobiographical disclosure? If his elaborate apparatus encloses the pathos of a “heartbreaking” narrative that makes a bid for high literary seriousness, is it simultaneously the practice and the send-up of the genre? Is his narrative a call for a new version of white middle-class masculinity that undermines the masculine/feminine binary within heterosexuality? How does that reorganizing of the nurturing role in a “nuclear family” reconcile its displacement of woman from the center of the family? If Eggers’s narrative both revises gender stereotypes and, in its assault on readers, revives a Maileresque stance of autobiographical machismo, it also invites readers to collaborate in reconstructing the authority of life writing as a site of “keeping it real” precisely by exposing its contrivances.

In discussing these two works, we have raised several questions about autobiographical acts in this cultural moment. In brief: What is the relationship of avant-garde practice to issues of gender and the ethics of narration? What is the impact of differences of class, gender, ethnicity, and national identity? What modes of self-representation extend across a visual/textual interface? We close not with a definitive statement, but with an observation about the fluidity of contemporary acts of self-representation. As distinct boundaries between and among all of the above categories are fading, to what extent are literary, or narratively based, theories of the autobiographical useful for inquiring into self-reflexive narratives that interweave presentations of self across multiple media, including virtual reality? To what extent does our theorizing itself need to be remade by contemporary practice at these “rumpled” sites of the experimental, so that we may take account of changing autobiographer-audience relations, shifting limits of personal disclosure, and changing technologies of self that revise how we understand the autobiographical? As, in different ways, self-representational acts such as those of Emin and Eggers test the limits of the autobiographical as act, discourse, and visual/verbal interface, their extravagant “lives” may remake the critical locus of our own theories.

Notes

1. Although Emin was not awarded the Turner Prize, her controversial entry provoked a raging discussion among British art critics about the autobiographical as art. In June 2000, “My Bed” was purchased by Charles Saatchi for £150,000 (Brooks 7). We are indebted to Suzanne Bunkers for bringing notice of the sale of “My Bed” to our attention at the “Autobiography and Changing Identities” conference.

2. Our thanks to William Chaloupka, cultural critic and co-editor of the online journal Theory and Event, for suggesting Eggers’s memoir as a provocative case of contemporary Gen X memoir that includes a metacritique of its own practice of memorialization.

3. The August 2000 Harper’s Magazine includes an “Apologia,” first run in The Harvard Advocate (Summer 2000) as an e-mail interview with Dave Eggers, in which he responds extensively to the charge that he has sold out to big-time publishing. Eggers responds to the charge: “We just don’t care. We care about doing what we want to do creatively” (“Too Legit” 23). A sidebar, “Corrections,” from Beth Eggers, Dave’s older sister, however, tells a different story. It reprints selections from a correspondence between Beth and Gary Baum in the April 17, 2000, column of his webzine, My Manifesto (www.aphrodigitaliac.com), on the Dave Eggers phenomenon. Beth questions Dave’s characterization in the memoir that she “helped out,” describing how substantial her own contribution was to raising Chris(toph)er, her care of their dying parents, her oversight of housing and financial arrangements, her status as Chris’s legal guardian, and, most damningly for Dave, her assertion that “Dave used my journal to refresh his recollection about many things—that’s why he thanked me in the acknowledgments and probably also because he felt guilty for misrepresenting things” (23). The questions she raises about misappropriation of both life and writing are unresolved as this essay goes to press.

4. We do not take up distinctions between autobiography and memoir here, but refer readers to Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narrative. Eggers uses “nonfiction” and “memoir” interchangeably, and does not use the term “autobiography.” As his text focuses on one part of his past during his parents’ dying, and after their deaths, it does not encompass the whole of his or his brother’s lives, though it draws on a range of autobiographical strategies.

5. This interchangeability of pronouns characterizes the mirror relationship of writer and reader, as well as that of memoir and fiction, often solicited by contemporary autobiographers, as Susanna Egan has pointed out in Mirror Talk. Egan discusses the “crisis-driven autobiography,” especially of “autothanatographers,” a genre to which Eggers’s memoir, originating in his parents’ deaths, is linked (225–26). Egan observes that such writers “create the life of the moment over and over, preferring to mark time as present, liminal space rather than in terms of past or future” (225). By being “multifaceted, mirror talk reflects the very indeterminacy of life in crisis,” and calls on readers to engage in collaborative acts of interpretation (226). Egan’s emphasis on narrative co-construction in an ongoing present moment is suggestive for the innovative autobiographical mode engaged by both Eggers and Emin.

Works Cited

Brooks, Richard. “Saatchi pays 150,000 for Emin’s soiled bed.” The Sunday Times [Vancouver, British Columbia]: 16 July 2000: 7.Donnell, Alison. “When Writing the Other Is Being True to the Self: Jamaica Kincaid’s The Autobiography of My Mother.” Women’s Lives into Print: The Theory, Practice and Writing of Feminist Auto/Biography. Ed. Pauline Polkey. London: MacMillan/New York: St. Martin’s, 1999. 123–36.

Egan, Susanna. Mirror Talk: Genres of Crisis in Contemporary Autobiography. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1999.

Eggers, Dave. A Heartbreaking Work of Staggering Genius: Based on a True Story. New York: Simon & Schuster, 2000.

Gilmore, Leigh. “Limit Cases: Trauma, Self-Representation, and the Jurisdictions of Identity.” Biography: An Interdisciplinary Quarterly 24.1 (Winter 2001): 128–39.

Kauffman, Linda S. Bad Girls and Sick Boys: Fantasies in Contemporary Art and Culture. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1998.

Lejeune, Philippe. “The Autobiographical Pact.” On Autobiography. Ed. Paul John Eakin. Trans. Katherine M. Leary. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1989. 3–30.

Poster, Mark. What’s the Matter with the Internet? Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2000.

Smith, Sidonie, and Julia Watson. Reading Autobiography: A Guide for Interpreting Life Narratives. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2001, expanded 2nd edition 2010.

———, eds. Interfaces: Women’s Visual and Performance Autobiography. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002.

“Too Legit to Quit.” Harper’s Magazine Aug. 2000: 19–24.