Life Writing in the Long Run: A Smith & Watson Autobiography Studies Reader

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

21. Parsua Bashi’s Nylon Road: The Visual Dialogics of Witnessing in Iranian Women’s Graphic Memoir (Watson 2016)

Many memoirs by diasporic women in the generations after the 1979 Iranian Revolution and the founding of the Islamic Republic attracted international attention for their accounts of navigating the contradictions of Iran’s strict fundamentalist regime. These transnational narratives of upheaval and its aftermath, usually narrated by subjects now living in the West, are often situated by feminist critics within a liberal-humanist framework. Through this framework memoirs such as Azar Nafisi’s Reading Lolita in Tehran are read as “written for the West,” observes Madhi Tourage, because they are taken up by a global readership seeking validation of Enlightenment values.[1] Gillian Whitlock, expanding on this notion of readership, argues that Nafisi’s performance of literary authority in her memoir was undoubtedly an ethical act of defying Islamic fundamentalism in Iran at a key moment, but one vulnerable to becoming a “soft weapon.” That is, Nafisi’s account of reading Western literature and her story of emigration could be wielded, after the events of 9/11, in a marketing campaign for Western intervention in the Middle East when her “ideas [found] a brand” and she became a kind of “commodity” (21–2).

Responding to the global framing of diasporic memoirs, Nima Naghibi calls for a more nuanced reading practice with “a critical diasporic cultural politics [that] focuses on a creative tension between the home and the host country, interrogating the concept of the nation-state, and celebrating a border space that facilitates fluid cultural identities.” And she calls for rethinking the narration of the Islamic Revolution in numerous memoirs as a space of “both rupture and possibility, positioning diasporic Iranian women writers as key witnesses to testimonial narratives of loss and suffering” (154). Naghibi’s call raises many interesting questions, two of which I will take up: What kinds of representational strategies might make life narratives more resistant to exploitation by campaigns announcing a message of “freedom” and “liberation,” and thereby enable a comparative critical cultural politics? And, which autobiographical media offer the affordances to effectively link the personal and the political in ways that promote the telling of stories of crisis and trauma, on the one hand, and of innovative possibility, on the other, as they summon readers to map the “creative tensions” that they set up?

Telling a coming-of-age story set in revolutionary-era Iran, Marjane Satrapi’s graphic memoirs, which exploit the multimodal potential of comics to represent tensions between rupture and possibility, have been resoundingly successful. In Persepolis, Satrapi innovatively links the protagonist’s and her family’s experiences of suffering, trauma, and catastrophe to the secret pleasures and riotous good times they experienced, despite all, in revolutionary-era Iran, as well as the trials of becoming an artist in the era of the Islamic Republic. A landmark of graphic inscription and visual storytelling, Persepolis was originally published in French in four short volumes, rapidly translated into two English volumes, and made into a feature film that Satrapi drew, wrote, and co-directed, all widely distributed in the Global North. Her appearances on the lecture circuit and TV talk shows in the US and Europe made her a recognized and engaging spokesperson for democracy and women’s rights, even as her comics’ criticism of the fundamentalist regime made them unavailable in Iran. And Satrapi’s elegant stylizations, in black-and-white squared-off figures that capture the contradictions of personal experience in single frames, evoking both German Expressionist woodcuts and the carved iconography of Persepolis, the capital of ancient Persia, are both revelatory and moving. As Hillary L. Chute observes, Persepolis’ “exploration of extremity” takes place predominantly in the private sphere, but it represents memory and testimony in ways that make Iran’s traumatic history legible and politically charged (Graphic, 135). Marji’s “acts of verbal-visual witnessing” retrace events of the Revolution and its aftermath in order to recover what has been effaced by war (163), making Persepolis exemplary of how graphic narratives “reconstruct and repeat in order to counteract” (173). Further, the linkage of young Marji’s struggles with sexuality to the traumatic histories of family members and neighbors related in the two volumes of Persepolis link its graphic exploration of the personal to a critique of norms of “morality.”

Nima Naghibi and Andrew O’Malley similarly observe that Persepolis “upsets the easy categories and distinctions that it appears to endorse: between the secular West and the threateningly religious East; between the oppressed and liberated woman (i.e., veiled and unveiled); between domestic and political/public” (245). In so doing, it becomes “a forceful and interventionary response to the current anti-Iranian and anti-Muslim sentiment in the West” (245). They further contend that the ability of Persepolis to render young Marji’s volatile and changing responses, while simultaneously conveying conflicting perspectives on an issue, hinders viewers from jumping to quick judgments, even as its striking visual imagery elicits empathic responses that overcome Western stereotypes about Muslim women. And yet, Naghibi and O’Malley observe that even Persepolis has often been read through a Western humanist filter focused on engaging personal details, such as teenaged Marji’s touching costume of jeans jacket, Michael Jackson button, and hijab in Persepolis I (131), while ignoring its sharp critique of British and American oil-driven foreign policy and anti-Muslim propaganda.

Assuredly the combination of anguish about the revolution’s undermining of a distinguished Persian history and grief at the loss of family members and friends to the regime’s persecution makes Persepolis a moving and important intervention. It is notable, however, that Satrapi migrated to France in 1993 (and spent the mid-eighties in Vienna during her high-school education), although she affirms her identity as Iranian.[2] In my view these details do not threaten Satrapi’s credibility as a compellingly acute narrator. Nonetheless, it is important to note that she has remade herself as a cosmopolitan diasporic subject. Naghibi acknowledges that disputes around “authenticity” abound in discussions of memoirs by Iranian writers who left in the early post-Revolution years and express nostalgia for the pre-revolutionary past. Those who left have been called “the Iranians of the imagination,” as distinguished from “those who stayed behind and suffered through the war and the policies of the Islamic Republic” and want to claim that they are “the ‘real’ Iranians” (152). While Naghibi does not subscribe to this binary distinction, she observes that “the question of authenticity continues to haunt debates and discussions in the diasporic Iranian community,” a tension that Sidonie Smith and I have also explored for other kinds of witness narratives (Note 11, 188–9).[3]

But Satrapi’s is not the only graphic memoir to have tracked how the experience of the Revolution and the Islamic Republic affected both micro- and macro-Iranian histories. Parsua Bashi published her graphic memoir, Nylon Road, in a European language, German, in 2006, while she was living as a migrant (her preferred term) in Zürich; it was subsequently translated into English a year later, as well as into Spanish. As I will discuss, its innovative style of visual and verbal dialogics accomplishes two things: it is a tough yet engaging antidote to narratives of nostalgia and victimage, and its dialogical style actively resists appropriation to a liberal humanist point of view. Like Satrapi, Bashi as a girl and young woman identified with socialist-leftist ideological positions and criticized the excesses and abuses of the Revolution and its repressive aftermath. But because Bashi, born three years before Satrapi, did not leave Iran until 2004 (at age 37), her account of living there for decades offers an extended window on the upheaval of revolution and the fundamentalist regime that suggests how ideological shifts threaten, and texture the processes of, memory itself. Both artists generate imaginatively diverse images of their protagonists’ growing up as the flux of events plunges them into near-constant change and generates shifting self-definitions. But while Satrapi’s story, in both its images and discursive locations, is an evolutionary narrative of becoming a politically aware artist, Bashi’s comic is an open-ended dialogic. In Nylon Road’s plot the narrator engages serially, and non-chronologically, with eleven sharply contrasted younger “ghost” selves that were shed and “forgotten” after her migration and by whom she is “awakened” to the diversity of her former beliefs and positions, although she is by no means reconverted to any of their stances.[4]

Interestingly, Bashi’s innovative use of these avatars places them on the scene of past events in a way similar to how eyewitnesses are positioned, although they are not of course genuine eyewitnesses but visual fictions called up from memory. The eyewitness holds a special status in narrative accounts. The attestation “I was there” makes a unique bid for readers’ attention and empathy. In Gillian Whitlock’s phrase, the eyewitness serves as a “conduit and a receptor,” as “the reporter cultivates moral empathy by a subjective eyewitness account that responds to trauma performatively” (156). As Hillary L. Chute compellingly demonstrates, the affordances of comics enable them to play a particular kind of role in witnessing: the act of “being a witness to oneself” in Chute’s term (Disaster, 29) can, as it does in testimony, “visually incarnate[e]” the witness to trauma and “express the simultaneity of traumatic temporality and the doubled view of the witness as inhabiting the present and the past” (206).

Of course, a diasporic witness to her former experience of a repressive regime is incapable of literally being an “eyewitness” because migration is the necessary precondition for narrating a story of vulnerability, flight, and presumed relief. Only an on-the-scene journalist or observer can claim eyewitness status for on-site narrating in war or crisis. But some diasporic memoirists are in a stronger position than others to profess as surrogate eyewitnesses to the experience of national upheaval and oppression. In comics Joe Sacco has intriguingly explored this status, as Chute notes, by marshaling an exhaustive repertoire of documentary evidence to supplement what the memory of others or his own absence from the scene cannot reliably supply, as he does in Footnotes in Gaza. Bashi’s embodied former selves similarly exert pressure, variously expressed, to compel Nylon Road’s narrator to constantly negotiate with her memories as embodied subjects who are in “creative tension” with her migrant self and not resolvable into a coherent post-migration identity.

Bashi’s strategy of positioning her eleven embodied past selves on site, rather than having her memories recalled by a continuous child narrated I (although she does not reference official archives), dramatizes the narrating “I”’s personal past in the context of shifting events and ideological alignments that her past selves responded to quite differently over the decades in the flux of experience. Her rhetorical tactics and visual tropes for situating self-presentation, while not the “objective” approach of documentary testimony, provide a prismatically multi-sited account of her pre-migration past that contextualizes her post-migration experience differently than that of other diasporic women writers’ memoirs, conferring an experiential authority closer to that accorded the eyewitness.

The rhetorical strategy of imagined eyewitnessing also lets Bashi powerfully assert her position. She documents the significant abuses that, as a young woman, she underwent during the early days of the Republic that exemplify its repressiveness (a severe whipping by the Islamic Court, loss of most of her family and friends through emigration, and loss of custody of her child in a divorce trial); this catalog of humiliations and losses, however, is not defined as all that it meant to stay in Iran and work for change after the Revolution. Simultaneously, Bashi can extend her critique to the excesses of neoliberal capitalism, as embodied in her experience in Zürich but visible globally in both practices toward, and media representations of, women. This aspect of her dialogical representation has two effects: it undermines the West’s claim to ethical superiority, and it underscores the tendency to represent Islamic women as abject others without distinguishing among the histories and practices of various nations and periods. Bashi’s dialogical structure in Nylon Road’s sustained montage of past selves ultimately becomes a means of foregrounding the limits placed on women globally by conservative politics, be they “democratic,” “socialist,” or “religious-fundamentalist.”

In sum, Bashi’s graphic memoir, with its exponential multiplying of the figure of the drawn and narrated past self, is a challengingly dialogical “read,” and one explicitly resistant to being framed in liberal-humanist terms. Yet it has not enjoyed much success in English and is not well-known in either Anglophone nations or Iran, where copies are prohibited from circulating officially.[5] Despite Nylon Road’s neglect by English-language readers of comics and life narrative, in my view it merits attention as a case study in how a feminist diasporic graphic memoirist can improvise an innovative visual and verbal strategy for navigating both national politics and global cultural relations.[6]

I. The Search for “Me” in Nylon Road

Parsua Bashi is well-positioned to narrate her story. Born into a middle-class family with three children in 1966, over a decade before the Revolution, she refused her parents’ urging that she migrate—unlike most of her family and friends—after the establishment of the Islamic Republic. Instead, she studied art at the University of Tehran when it reopened in 1983 and became a successful, award-winning graphic designer. Bashi encountered difficulties in her personal life, however, after marrying at 23 to escape the pressures the Republic exerted on unmarried women fraternizing with men in public, for which she was sentenced to a severe whipping. She and her husband had a daughter, but she soon found him oppressively dominating and sought a divorce. When the punitive divorce court assigned custody of her daughter to the father, she grieved but eventually was “struck by Cupid’s arrow” in 2002 and left Iran in April 2004 for German-speaking Switzerland, although she did not know German, to live in Zürich with Nathanael Su, a well-known jazz musician of Swiss and Cameroonian parentage, whom she married (6, top right).[7] Nylon Road originated as a comic whose struggling protagonist has discovered the difficulty of remaking herself abroad, in her thirties, and resuming her artistic career. There she began work on a book of comic drawings.

Parsua Bashi wrote me that her idea of making the comic arose when she experienced “a Vacuum space between my past in Iran and my new life in Zürich” that spurred her to begin “a kind of daily sessions to write about my past, and draw some little pictures only to show to some friends” (Personal Correspondence, 28 Nov. 2015, subsequently referred to as PC). Nylon Road thus originated as a form of self-therapy with sketches that Bashi developed into a graphic memoir in collaboration with a translator and editor from Kein & Aber Publishing Company in Zürich. It was awarded the “Cultural Worlds in Switzerland” prize by Pro Helvetica, the Arts Council of Switzerland. Bashi’s journey was, however, no one-way trajectory. In 2009, three years after the memoir’s publication, she left Zürich and returned to Tehran, where she continues to live, working as a successful graphic designer. She has written other books in Farsi that have been translated into German and published.[8] Her return and reintegration are remarkable in light of the focus of Nylon Road on the protagonist’s discontent with—and sharp criticism of—life in Iran after the Revolution, although speculation on this two-way transit is beyond my inquiry.

As noted above, Nylon Road conducts its coming-of-age story as a conversation among versions or avatars of Parsua at various ages that, she says, “came from a real emotional/psychological situation that I was in at the time of writing this book. I had not any model in my mind. In fact I did not even have a concrete plan to write and draw a comic book” (PC).[9] This dialogical set-up of conversations enables her to interrogate notions of identity coherence for subjects caught in conflicting concepts of home, history, and memory amid the ideological perspectives of fundamentalist post-revolutionary Iran, the capitalist Global North, and—less frequently mentioned in Iranian diasporic memoir—the socialism associated with the former Soviet Union. The memoir thus serves as an act of transnational witnessing to Bashi’s own experience of double displacement, and resists any final resolution other than the artistic satisfaction of visually and verbally representing her condition.

Both Bashi’s creation of an autographic, Nylon Road, and her return to Iran three years later, prompt us to read her comic through a doubly “binocular” lens, in Marianne Hirsch’s term. That is, its shifts across the gutters of the page suggest Parsua’s ambivalence at different historical moments about her location and position (1213). Nylon Road serves simultaneously as a dissident history of the Revolution and the Islamic Republic, and a critique of Western consumerism and commodity capitalism that the narrator finds definitive of Swiss and, more generally, Western values; and Parsua, its protagonist, finds no border space, other than on the page of her memoir of double loss. Yet Nylon Road’s weighing of the difficulties and costs of migration and resettlement against the experience of repression, violence, and misogyny it identifies as realities of post-revolutionary Iran finds no full resolution. In its treatment of the individual and collective trauma occasioned differently by the Republic and by migration, it belongs to the genre of life writing that Sidonie Smith has termed “crisis comics,”[10] although, unlike most such comics, Nylon Road does not include an appeal for readers to bear witness to suffering or contribute to an agency aiding the artist. Rather, its tough yet funny interrogation of the complicity of the world’s nations—including Iran and the Islamic Middle East, Europe and the Americas, and the former Soviet socialist bloc—critiques how all of them in different ways conform their citizens to repressive ideologies that discourage independent thinking.

II. The Varied Reception of Nylon Road

Nylon Road has had little success in gaining traction in North America, in contrast to its reception in the German-speaking world,[11] where it has attracted a substantial, appreciative readership. With translation into Spanish, it also won readers in Spain. But despite its rapid translation into English (2007), Nylon Road is a graphic memoir that, even in this age of comics’ popularity, remains almost unknown even among life-writing scholars. The varied reception of Nylon Road might be attributed to both the contrasting publishing strategies of its Swiss and American publishers and its differential reception by critics in Europe and North America. The original German edition of the comic was marketed as a kind of double-edged sword—a memoir simultaneously critical of the Islamic Republic and Western neoliberalism that was welcomed in European reviews as a witty and probing intervention into cultural politics. In the Süddeutsche Zeitung, a leading German newspaper, Simon Poelchau characterized Nylon Road as a thoughtful dialogue among several different embodiments of Parsua about the excesses of both Iran and the West, noting, for example, her sharp quip that in Zürich she enjoys gourmet dining while Iranians are starving under Western-imposed sanctions.[12] In the online journal Migrazine, Olivera Stajić observed Nylon Road’s substantive interrogation of Islamic fundamentalism and Western feminists’ easy rejection of its critique of the limits of their positions.[13] Clearly Nylon Road was heralded as a serious contribution to debates about both the place of post-Revolution Iran in global politics and a comic sharply aware of discrepancies between Western humanist ideology and its economic and cultural practices.[14]

In English-language journalism and scholarship, however, Nylon Road received little critical attention. An anonymous review in the Toronto Globe and Mail—one of the few newspapers to cover it—was, in my view, a cranky misreading: “There’s a lot of anger here, not only that of the mullahs and their minions, but that of Bashi, appalled at how more than 2,000 years of Persian history and culture had been lost in the dark backward abyss of religious fanaticism.” Online, Jonathan Liu’s review in Wired was less than informative: “What [Nylon Road] really reveals is how little the two cultures really know about each other, let alone being able to understand and sympathize with each other.” These reviews offer little insight into the complexity of Nylon Road; there are to date, no critical essays on it in English, to my knowledge.[15]

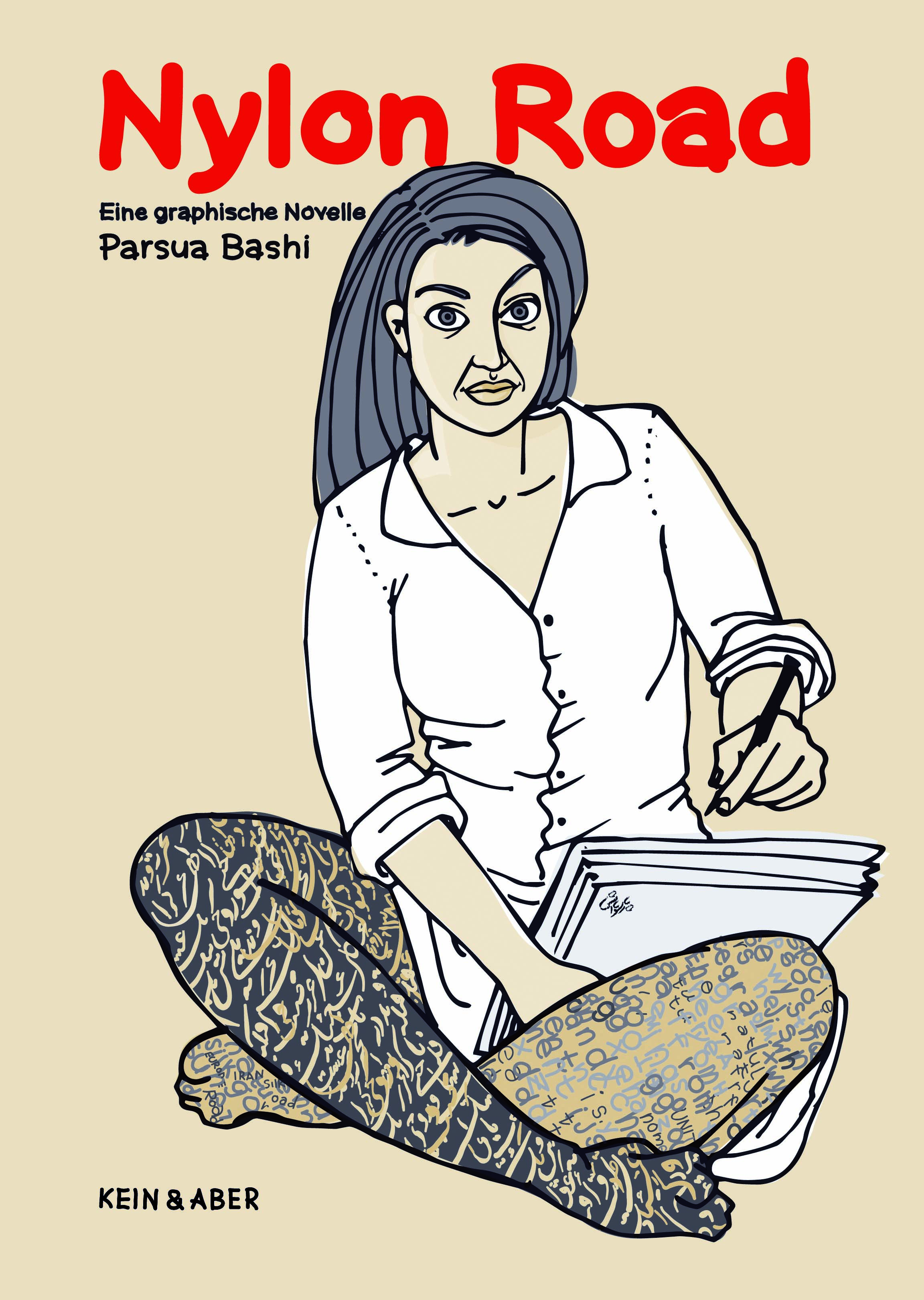

A comparison of the two versions of the cover of Nylon Road suggests a possible reason for its lack of impact in North America. The original illustration used for the German and Spanish covers, which does not appear elsewhere in the comic, captures Bashi’s dilemma as a diasporic subject caught between conflicting national and political identities (Figure 1). On it, Parsua, the narrating “I”, sits in a full-frontal, cross-legged position, gazing at the viewer as she draws on a sketchpad. Each of her stocking-clad legs is inscribed, one with Persian characters, the other with Roman-alphabet letters and numerals.[16] The nylon stockings serve as both a signifier of feminine fashion and a marker of Bashi’s uneasy location between opposed cultural and linguistic worlds along, not the silk road of ancient discovery, but the “nylon road” of women’s contemporary transnational transmission of image, fashion, and sexuality. As an adult migrant to Switzerland, Parsua is literally situated at a crossroads of conflicting ideological, religious, and social views between the two worlds, Iranian-Muslim and Western-secular, that she inhabits. The iconic image captures her dilemma—how to make this gendered, cultural, religious, and linguistic transition without losing all that she has been and known—and expresses it through the binocular optic of a fashion statement embodying that tension.

Front cover, German edition. Reprinted by permission of Kein & Aber AG, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

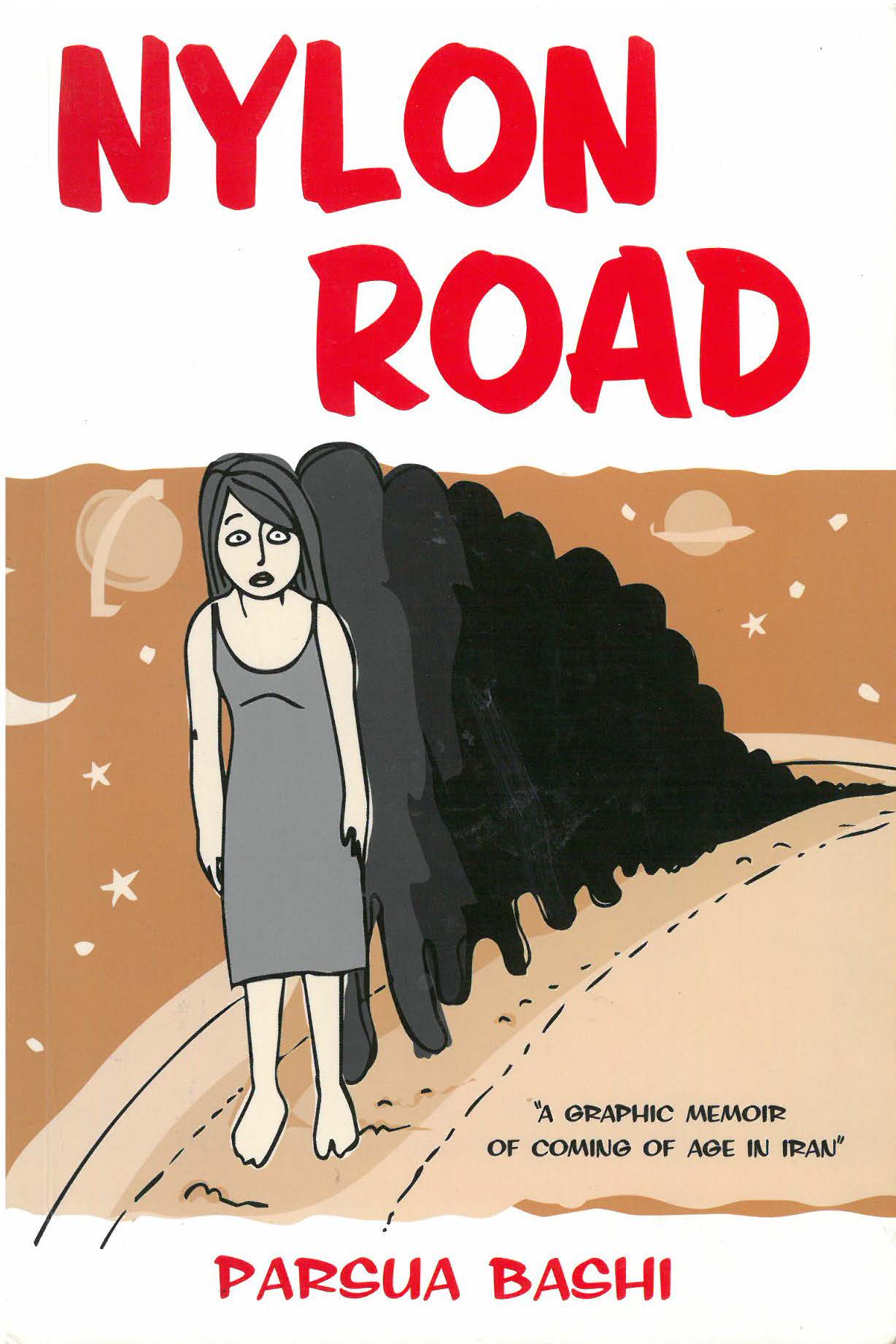

In contrast, the cover of the English-language edition chosen by the British-American publisher, St. Martin’s Press, reproduces a frame in the comic depicting a child-woman emerging from a line of shadowy, veiled female figures who are submerged in dark shrouds (Figure 2).

Front cover, English edition. Reprinted by permission of St. Martin’s Griffin, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

She is barefoot, slumped in dejection, and wears only a slip of a dress as she stands on the round surface of the globe against a vaguely Zoroastrian planetary background.[17] While this pose characterizes an initial moment of abjection after the narrating “I”’s migration to Zürich, her helpless appearance is untypical. And the difference in affect between the two covers is striking: The original Swiss cover suggests the ironic self-representation of an acknowledged transnational artist, while the English-language one depicts a dislocated refugee as global victim, which was not Bashi’s situation; rather, she left Iran voluntarily for a romantic interest.

Additionally, each version of Nylon Road has a different subtitle. For the original text in German it is simply eine graphische Novelle, “A Graphic Novel.” The English version, however, is subtitled A Graphic Memoir of Coming of Age in Iran, affixed next to Parsua’s feet on the “road of life.” This subtitle places Bashi’s comic within the Bildungsroman tradition of education as accommodation to Western norms and values, which counter the history of Parsua’s transits that complicates and even subverts that tradition. Paratextually, the cover of the English version makes a bid for readers’ sympathy with an apparently hapless victim, while the German original invites the viewer’s engagement with a savvy and elegant bicultural artist. The English cover thus stylizes the comic as a “soft weapon,” to use Whitlock’s phrase, in the American “war on terror,” a representation of Bashi’s position at odds with both the comic’s original cover and the narrative that unfolds in it.

Interestingly, Bashi expressed to me her concern about the different covers used to market her graphic memoir: “[T]he German version of my book is entirely my work from a to z. The cover design and the layout of the book is [sic] mine as well. My publisher Mr. Haag trusted me totally and . . . having worked as a graphic designer for a long time helped me to make the book have a proper look . . . [But] for the English version the publisher wanted to change the cover design with one of the panels of the book. Honestly talking, I do not like either their choice of the drawing nor the layout. . . . I did not have any authorization in the publisher’s visual or literal preference” (PC).[18] That is, Bashi’s artistic agency was undermined in the English-language publisher’s design and cover of the book. While these differences in cover choice may seem slight, they are linked to larger distinctions about the circulation of Bashi’s graphic memoir and the receptivity of Western and diasporic audiences to what I call its dialogical conversations.[19] What is going on between the covers of Nylon Road that its American publisher modified and that Western readers in North America missed?[20]

III. Reading and Viewing the Dialogics of Nylon Road

In working out a graphic mode to represent her psychic and political struggles, Bashi uses a fluid line reminiscent of contemporary magazine illustration and visual techniques drawn from portraiture to create a style of self-representation that I term a visual dialogic (and discuss in more detail in this essay’s last section). Her drawings represent encounters between her narrating and embodied past “I”s as confrontations, often by shifting the positions of the I’s within the frame to signal which of the opposed points of view is being defended. Bashi described her process of composing the comic as it moved from what Hillary L. Chute calls hand-drawn “marks” to final form, writing me: “First I draw quick pencil sketches on paper, then draw them again in a final form by ink on paper, scanned the in outlined versions, and colored them in computer by a drawing software. For each panel 3 versions. The bubbles with the text was the last layer” (PC). That is, the “I” who appears in each chapter as both narrator (in rectangular boxes above the frames) and speaker (in text bubbles of dialogue) is embodied in a kind of visual “language” that organizes multiple, fragmented moments of remembered experience. While Nylon Road’s graphics have a different, more cartoon-like “look” than the boldly beautiful images of Persepolis, they conduct innovative experimentations. Within the limits that Bashi set for herself of outlined figures and a two-color scheme (terracotta, gray, black, and white), the comic frames and pages explore a gamut of visual self-representation that also serves as a collage of witnessing to four decades of history.

It is challenging, but rewarding, to closely map the contrapuntal narrative shuttles that Nylon Road navigates between Parsua’s life in Tehran from the early 1970s till 2004 and her life thereafter as an Iranian migrant in Zürich. The comic consists of twelve unnumbered chapters, each separated by an untitled page with a small cartoon pulled from a detail in the text. Each chapter returns to the frame story, in which Parsua is situated in her present location, Zürich, and engages with a self from her past life in Tehran. Readers thus shift continuously between the dramatically different contexts of past upheavals and the apparent serenity and stability of Switzerland. Bashi’s narrative logic presents her selves, at different ages, as eyewitnesses to their historical moments. And each past self conducts an increasingly contentious dialogue with the narrating “I”, demanding an account of who she has become in her present life.

The eleven avatars confronting Parsua in various chapters are distinguished by their ages, clothing, and hairstyles, as well as the hijab or headscarf worn by adult Parsuas in Iran. This visible evidence strengthens our sense of Nylon Road’s “binocular” view of the Iranian Islamic Republic as the narrator’s dialogue with her increasingly adversarial former I’s—presented associatively rather than in chronological sequence—brings competing truth claims into view along with their divergent appearances. Teenaged Parsua is ideologically invested in Marxism: her young adult self is stunned by changes that are introduced with the Khomeini regime; a later one becomes an active resister, first against the post-Revolutionary fundamentalist government and then, in Europe, against the excesses of neoliberalism and the ubiquity of racial prejudice. Both a verbal and a visual dialogic, these conversations juxtapose various Parsuas’ earlier dissident views on the Iranian Revolution and the subsequent Islamic Republic to the narrating “I”s as a montage for the experience of historical flux. Although Nylon Road does not draw on intergenerational memory (unlike Satrapi’s memoir and many others), its assemblage of decades of remembered experience during and after the Revolution enables Parsua’s selves to perform a novel kind of “eyewitnessing” to events after many Iranians had emigrated. Thus Bashi’s strategy of giving voice to her distinct former selves, rather than simply recalling memories, situates her narrating “I” as engaging with the gap between her former embodied positions and her new migrant consciousness.

The way that Bashi strategically lays out her contending “I”s on the page confers an authority on her past selves that, because of the dominance of the image in graphic memoir, makes the effect of Nylon Road unlike the linear thrust of written autobiography, with its privileging of the authority of the present-tense narrator and, thereby, the Bildungsroman’s teleological view of life. The past selves of Parsua, varied with the age and position of the avatar and responding to one another’s assertions and styles as they narrate moments of growing up in Iran, are contrapuntal figures rather than the evolutionary self characteristic of the Bildungsroman; as such, they position the narrating “I” as a fractured and provisional, rather than consolidated, identity. The comic’s reworking of the traditional Bildungsroman format allows Bashi to present a persona who is a mature and accomplished woman at home but an innocent abroad, insufficiently prepared for the cosmopolitan world of Zürich, even as she sees beyond its complacent materialism.

In sum, unlike the quest for integration of past and present selves that transforms a social outsider into an enfranchised citizen in the Bildungsroman, Bashi’s narrative undercuts that plot in two ways. Recollection is depicted as an involuntary, experiential process summoned by embodiments who are radically different from the present-time narrating “I” at the same time that they “know” her. And memory shifts from being a merely personal function as it focuses on public events that foreground the differing customs and values of the Islamic Republic from the secular West, represented in Zürich. Nylon Road thus wages an ideological debate through the power of images as much as the presentation of contending political positions, even as it deconstructs the binaristic stereotype of “Islam versus the West” as an inadequate framework for the complexity of women’s lives in the shifting gender politics of both post-Revolutionary Iran and Western Europe. In what follows, I deal with Nylon Road’s dense, rich chapters at length.

The frame story that begins Chapter One introduces the narrating “I” in a half-page panel depicting her in a blouse and pants, with uncovered long hair and folded arms, gazing calmly at the viewer as she presents herself as a 37-year-old woman who left Tehran in April 2004, two years earlier, after falling in love (a story she omits).

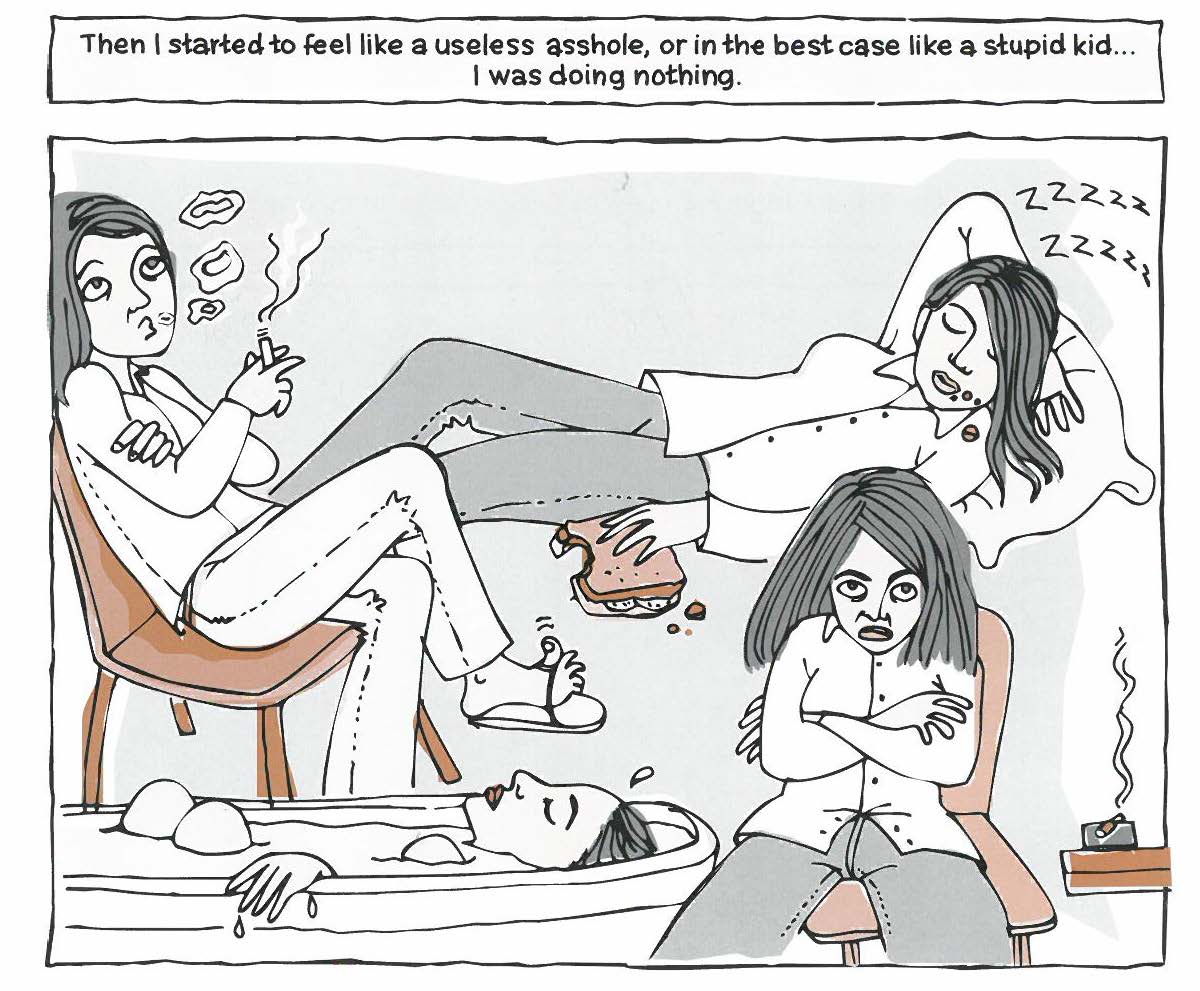

Parsua begins by disclosing her expectation that, after emigration, she would become not just another immigrant, but someone able to engage in “real life” in her “new society” (8). Subsequent frames detail her struggle to learn both German and Swiss-German dialect, find a job appropriate to her graphic-design skills, and develop a social circle. But the difficult process of cultural and linguistic assimilation leaves her feeling discouraged and displaced. Parsua sums up her dilemma: “I started to feel like a useless asshole” (Figure 3).

From Nylon Road (p. 12) by Parsua Bashi. Reprinted by permission of Kein & Aber AG, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

In the panel four images depicting her as idle and disgruntled occupy a single visual plane, a style that Bashi develops further in subsequent chapters. This moment of self-recognition in frustration becomes the spur to her self-reflection.

While the narrator stands brushing her teeth, “a happy-go-lucky little girl” of 6 appears in shorts and sandals holding flowers and toys. Recognizing this grinning apparition by her birthmark, the narrator, stunned, asks, “How could I have forgotten me?” (15). Parsua-6 responds, “The only reason I’m here is because you called.” She goes on to tell Parsua that the adult woman is out of touch with herself—“I was the one who had lost contact”—and informs her that there are “more of us waiting to see you,” establishing the narrative convention of visits by past selves that anchors Nylon Road’s plot. When Parsua responds, “I simply could not deny my past. I had to remember the days I had spent with them—with myself,” what might seem a Western cliché of getting in touch with “the child within” inaugurates an urgent autobiographical quest (18, bottom half). The encounters that ensue trace the narrator’s engagements with the eleven former selves who appear, in non-chronological order, at ages 6, 13, 16, 18, 19, 21, 23, 29, 33, 35, and 36. Disclosing her unhappiness as a dislocated migrant, Parsua identifies the moment as a turning point and awakening: “I was alone, hopeless, desperate, and apparently unable to deal with the situation. . . . They were here to remind me that what I am now is the result of their lives” (18). Parsua’s quest then moves toward increasingly tense encounters with the historical moments that her former selves experienced and the extreme ideological points of view, from the perspective of her newly Westernized persona, that they espoused.

Unlike the search for unequivocal rescue from the Islamic Republic that many Iranian diasporic memoirs recount, as Chapter One goes on, Parsua begins to regard her migration to Zürich as producing a traumatic gap in her life that becomes visible on reflection. The revelation—“I saw my entire life in a flash”—is drawn as “MY LIFE!”, a jagged-topped building of concrete blocks that have broken apart the edifice of a formerly coherent self (19, top left). But in a close-up portrait, the next frame reveals the other side of that moment, a simultaneous “ENLIGHTENMENT” or “Aha” awareness, with literal light bulbs in Parsua’s eyes. She is awakened to the kind of double consciousness that stirs a desire to examine her past—and inaugurate her story (19, top right).

Bashi wrote to me about this moment: “The Idea of having conversation with myself came from a real emotional/psychological situation that I was in at the time of writing this book . . . I really had these conversations with myself, since I was mainly alone and had time,” in the “Vacuum space” that she experienced between her Iranian past and new life in Switzerland (PC). The felt space, depicted as a gap between parts of the building, is echoed in the gutter between the two frames that juxtapose “The interruption” and “ENLIGHTENMENT,” which both occur as Parsua feels that her life became “absurd and meaningless” (19 top left). As Hillary L. Chute observes, “the gutter [is] . . . the figuration of a psychic order outside of the realm of symbolization, a space that refuses to resolve the interplay of elements of absence and presence” (Disaster, 35). This unresolved, traumatic space marks the narrator’s awakening to autobiographical consciousness as a difference that produces rupture rather than consolidating an edifice of the self.

In this crisis of self-reflection, while Parsua listens to the radio, the second avatar appears in her 16-year-old self from 1982, situated during the Iran-Iraq war and in the wake of the Cultural Revolutionary Council’s installation of a rigidly fundamentalist Islamic system. Parsua-16, steeped in that milieu, voices a critique of the “relaxed” European view of the world reflected in feel-good broadcasts, while in Iran “other people are dealing with shit” such as mandatory prayer in school and the conscription of all 18-year-old men for the war (24). In Bashi’s depiction this moment is a collision of two versions of herself, differently embodied in Parsua’s long hair and blouse and the veiled garment of the patriotic teenager sternly admonishing her. As they stroll together in Zürich, they glimpse a hippie Western woman who has appropriated a prayer shawl to wear as a skirt. She appalls Parsua-16 because she has no idea that the shawl is traditionally used as a head-covering by a range of Middle Eastern people, from Palestinians to militant fundamentalists, and would disregard her as a “foreigner” (25). In the ensuing argument between Parsua’s two selves, each makes points about perceptions of Islam, dramatized on the page by their shifting body language, gestures, and dominant or subordinate placement in the visual dialogic.

During Parsua’s reflection in Chapter Three on whether she is “homesick” for her “hometown” or has just forgotten the violence of Iran’s past in nostalgia, her 18-year-old self of 1984, the fourth year of the Iran-Iraq war, appears in pants and a ponytail to narrate the painful personal realities of those years (28). It is a litany of losses: the brother she felt close to was smuggled to Turkey to avoid the army, and many of her family and friends left for Europe or North America, trips that turned into a kind of permanent emigration that was “seriously tearing families apart, some forever” (30). Eventually “none of our family or friends were left,” except for her parents, yet Parsua-18 seeks to remain true to her ideal of what the nation, which once was Persia, could again be (33). As narrator, Parsua sums up the conflicted feelings expressed in debates with her friends and family, asking whether it was worse to abandon her native land—“I was young [but] strictly against emigration” (32, middle) and leave it to “a bunch of mediocre midgets” (32, bottom), or to feel “abandoned” in not leaving a place that, in the view of many, had betrayed its Persian history (33, top right). Despite the urging of even her parents, Parsua-18 remains staunch in her determination to study fine arts at Tehran University. Responding to her avatar’s question about the most difficult part of migration, Parsua acknowledges that she felt more in exile at home—“most homesick in my own hometown” (35). At the same time in her adopted new land she is virtually speechless without her mother tongue, as she confronts the difficulty of successfully integrating into the complexity of Swiss-German society (34, bottom). The experience of crisis in Iran has “vaccinated [her] against” homesickness; after a life of it in Tehran, she is without a “home” anywhere (35, bottom).

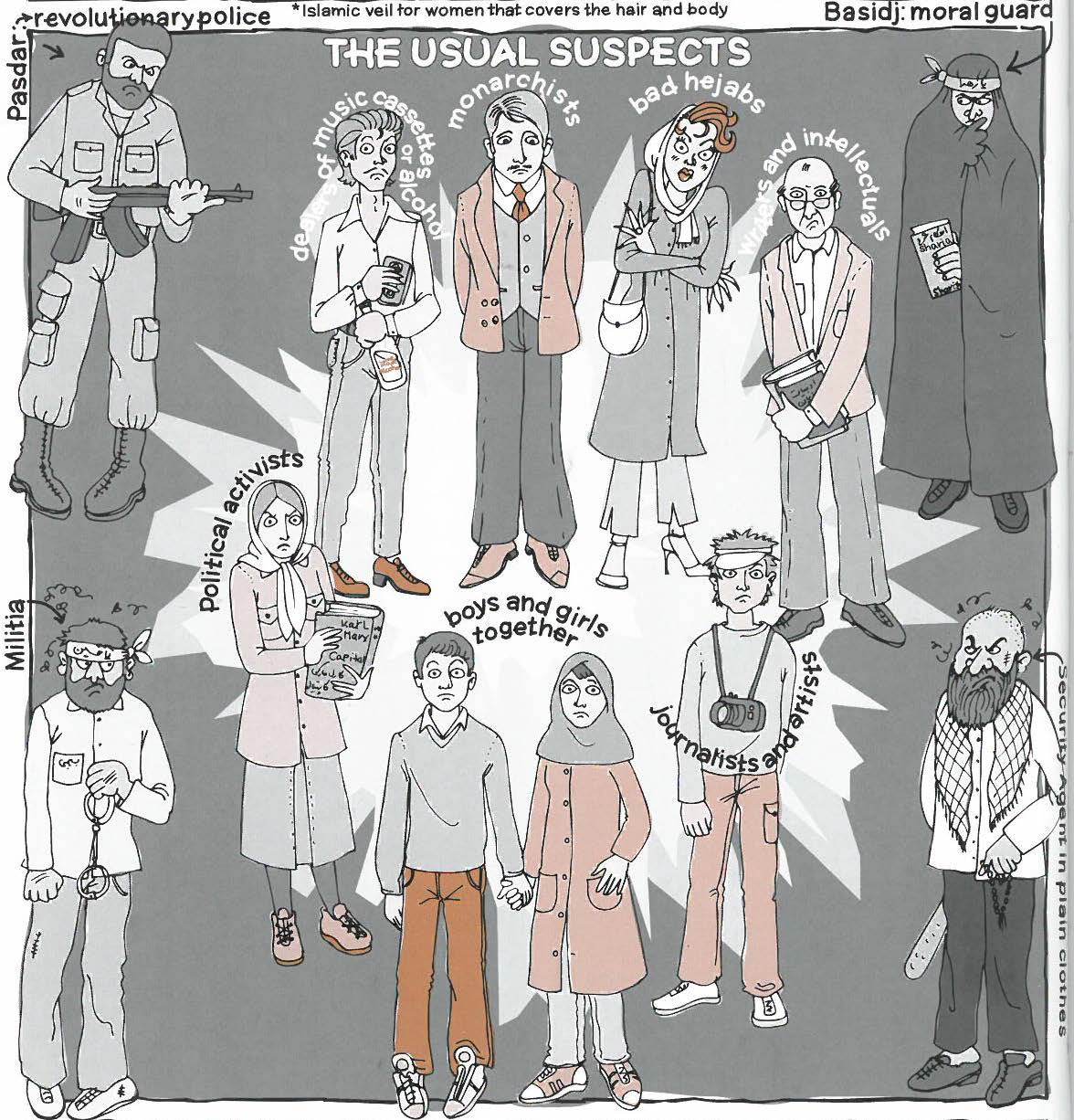

Parsua’s notion of her self-sufficiency is next challenged by her 23-year-old self (in 1989) who calls on her to recall a moment when the revolutionary guards were busily rounding up what she calls “THE USUAL SUSPECTS”—political activists, boys and girls together, journalists and artists, writers and intellectuals, monarchists, dealers of music cassettes and alcohol, “bad hejabs”—for alleged crimes in appearance, ideas, or expression (Figure 4).

From Nylon Road (p. 42) by Parsua Bashi. Reprinted by permission of Kein & Aber AG, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

In Tehran, Parsua-23, lonely without her friends, develops an inexplicable crush on a male artist colleague who is drawn as portly and invasive, enveloping her in a sea of words (45, panel, second row). When she is caught walking on the street with a male classmate by a Pasdar (member of the Revolutionary Guard) who challenges them for associating in public, she defiantly responds that such acts are not prohibited by Sharia law. For this retort she is sent to the Islamic Court and sentenced to a whipping of seventy lashes (44). Summing up her response to this painful moment, the narrating “I” recognizes that her sense of citizenship was violated in Iran: “I felt enormously ashamed to be part of such a society” (44).

Depressed and humiliated, she turns to her boyfriend, despite their differences. When he asserts that he will “protect her”—“I’ll make a PERFECT woman out of you”—she agrees to be married and, three months later, discovers she is pregnant (45). Although Parsua now regrets her “stupid decision” to wed this tyrant and the impact it had on the daughter she gave birth to, she consoles her younger self for the bitter experience. As narrator, she goes on to observe how the limiting laws of religious fundamentalism lead young people into bad marriages in Iran; conversely, in Europe, people can get to know each other before marriage (47). Finally, both Parsuas resolve their quarrel by admitting that young people can make mistakes anywhere, as both Middle Eastern and Western European nations exert forms of domination over their citizens. And yet, the details that emerge of her sheltered life despite supportive parents, the brutal punishment she received in the Islamic court, and her subsequent coercion into marriage, stand as an indictment of how the Republic’s excesses caused damage to her personal life.

This critique of personal life is extended, in Chapter Five, to a critique of political conservatism in both the Middle East and Euro-American nations. In Zürich Parsua’s encounter with a passionately pro-Persian Iranian-migrant woman forms a pedagogical moment in the comic that is aimed as much at expatriates as Western readers. When this other woman speaks as “we PERSIANS” and denounces Arabs as “CAMEL RIDERS,” the four-page spread juxtaposes icons of Persian culture, displaying the splendors of the empire before the Arabs arrived that she enumerates, with an ever-closer focus on her screaming mouth. But Parsua’s response, as a cosmopolitan subject, is pained: “I was so embarrassed” (54), she confesses, as she denounces the woman as “a chauvinist racist” (55), uneasy with the nostalgia of the pro-Persia diasporic woman, reminiscent of the “Iranians of the imagination” to whom Naghibi refers.[21]

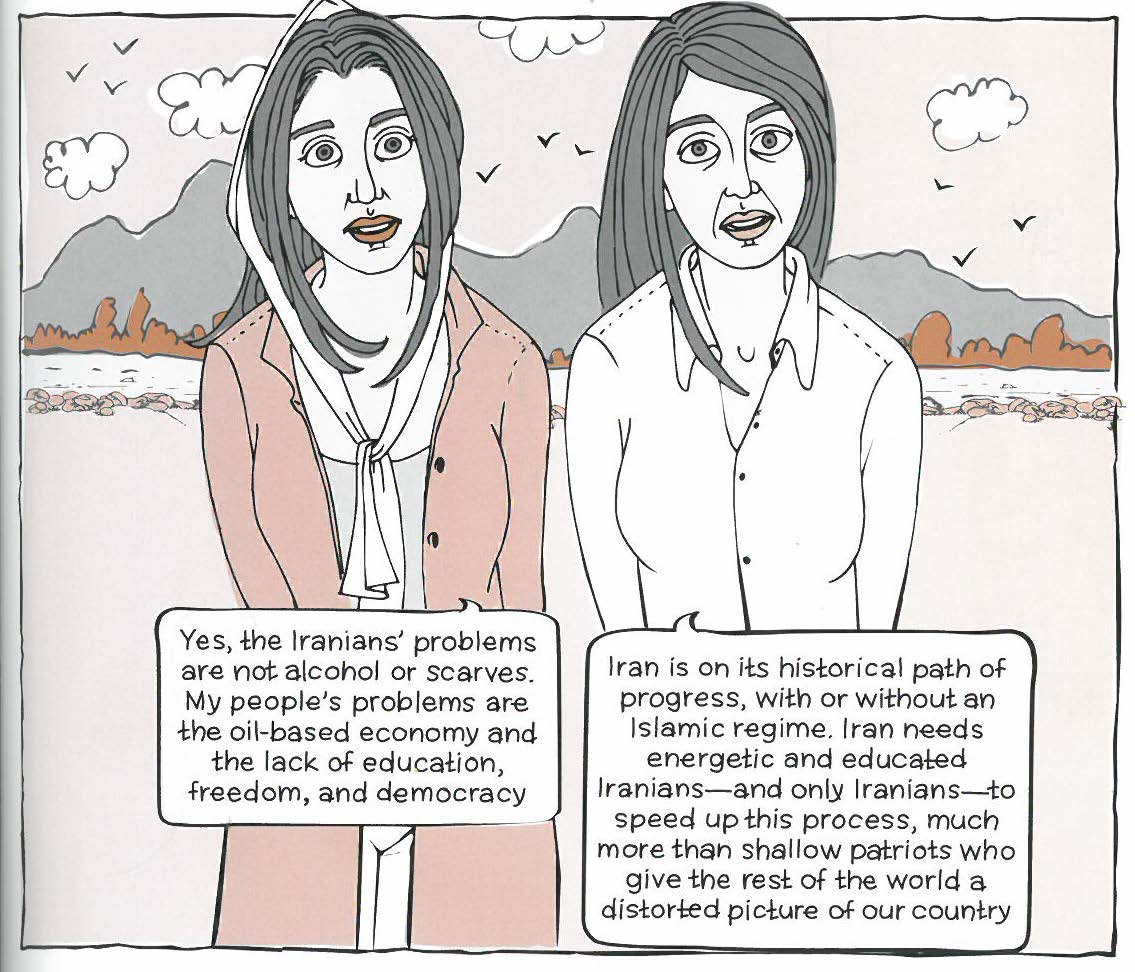

In response, “one of my most patriotic selves” appears, the 35-year-old woman of 2001, a few years before Bashi migrated. Initially the two Parsuas argue about their justifications of the Islamic Republic and the “West,” their upper and lower positions within the frame alternating as each makes her argument. “Patriotic” Parsua-35, committed to the relative freedom of pre-Revolutionary Iran, denounces Islamic fundamentalism and proclaims, in angry profiles, the excesses of Muslim leaders as “terrorists” who subject their own citizens to cruelty. In response Parsua challenges her former self’s view as “poisoned by rage” for claiming that the Islamic Republic’s imposition of religion is at fault for all Iran’s woes, not least because Islam has been merged with Iranian culture for 1,400 years (56–7). Their dispute, captured in a montage of close-up profiles of the two women sparring, induces Parsua to regard fundamentalisms as “simply for political purposes,” “propaganda . . . based on those false clichés” that use avowals of a “sacred mission” to hide their “dictatorial regime” (58). The narrating “I” acerbically retorts to her avatar, that, while the fundamentalist Islamic Republic makes laws mandating the veiling of women and prohibiting alcohol, the West deports Middle Easterners as terrorists and, in France, condemns head-scarf-wearing as a religious symbol at the same time that it condones right-wing Aryan-nation protests and starting wars in Iraq and Afghanistan. The so-called “holy war” of fundamentalism thus links right-wing conservatives in East and West like “a double-sided blade” in which they use mutual hatred to impose undemocratic limitations on their citizens’ rights, a point on which her two selves, despite their different dress and locations, ultimately concur in the chapter’s last frame, a moment of shared insight (Figure 5).

From Nylon Road (p. 61) by Parsua Bashi. Reprinted by permission of Kein & Aber AG, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

The chapter’s process, then, does not suggest that Parsua “reconverts” from her Westernized tastes to Iran-nostalgia; rather it produces a recognition of repressive practices that underlie the ideologies of both the Islamic Republic and Western neoliberalism. As the final frame concludes, conservative propaganda in Iran, by shoring up the theocentric Iranian regime’s claim of a “holy war,” masks real issues of poverty, hunger, unemployment, and censorship of speech, enabling the dictatorship to mystify its power as religion (57). In parallel fashion, the West resists acknowledging how its own media reports can fuel attacks by immigration police and right-wing groups directed at Muslims (59–61). Thus Parsua’s response, in her dialogue with “patriotic” Parsua-35, structurally links Islamic fundamentalism with its seeming opposite, the West’s claim of liberatory humanism.

Chapter Six takes up narrating Parsua’s encounter with her divorced 29-year-old “mother-self,” who lost custody of her daughter because she asked for a divorce from her jealous and possessive husband (65). Yet when weeping Parsua-29 recounts her sad story, Parsua rebukes her for refusing to recognize that she had a need to survive, despite her pain about the personal loss of her daughter and the political loss of her homeland (66). Parsua the narrator talks back to her newly divorced self about how the bitter loss of her child to her husband fueled not only her grief, but her critique of Iranian custody laws favoring the husband as a “religious” policy. And she draws a political conclusion that her younger self couldn’t see, namely how “religion” masks the Islamic Republic’s underlying “political purposes,” in frames of the prejudicial court process that caricature the judge and lawyer. The narrative rehearses Parsua-29’s testimony to the judge as a set of drawn memory-moments about her “paranoid” husband’s jealousy as he forbids her to see others, including her own mother, slaps her for “flirting,” and takes the television away from their child (70). While her testimony is useless because, as a housebound woman she had no witnesses, the drawings form a powerful indictment of a sexist and corrupt judicial process. A meta-drawing of objects incorporated in each frame for three pages represents Justice as a blindfolded woman in floor-length coat and veil holding a sword and balance scales in increasingly precarious fashion. When the judge assigns the child to her father, saying “True Muslim women live their lives with husbands even if they get beaten every day,” the scales topple (69).

Parsua-29 summarizes the social and professional rejection she experienced in a “JUST DIVORCED” composite drawing that itemizes aspects of her pariah status in Iran, including the many men who offer help privately in exchange for sex. Parsua urges her former self to let go of her victimage as “a poisonous habit of begging for sympathy,” drawn as the coat of pain and sorrow that she can only flush down the toilet at the chapter’s end. She then reminds her 29-year-old self of the leap she took to become independent and considers her question about whether more progressive societies exist (72). Their conversation becomes an occasion for a feminist critique of the treatment of women, as Parsua notes that, on the one hand, Iranian women had the vote earlier than their Swiss counterparts (enfranchised in 1972); yet, on the other, in Iran women earn 30% less for the same jobs (72). Ultimately, “women all over the world are struggling for their rights. Some more, some less . . .” (72). Thus the narrating “I”s personal encounter with Parsua-29’s beliefs and position serves as an act of consciousness-raising that exposes socio-political contradictions globally. Her younger self’s dejected reaction, understandable and brave at one moment, is modified by the end of their dialogue to enable change and growth as she moves beyond it. That is, in this passionate dialogue one self’s point of view does not negate the other’s, but, in dialogical fashion, can lead to self-forgiveness and insight, if not the end of personal pain about loss (74). In confronting each other’s different values as they debate the cost of fidelity to one’s native land versus the experience of a more tolerant society at the cost of losing a homeland, the drawn narrated and narrating “I”s reconcile—though the memory of losing her child is drawn as a knife that still stabs Parsua to the heart (74).

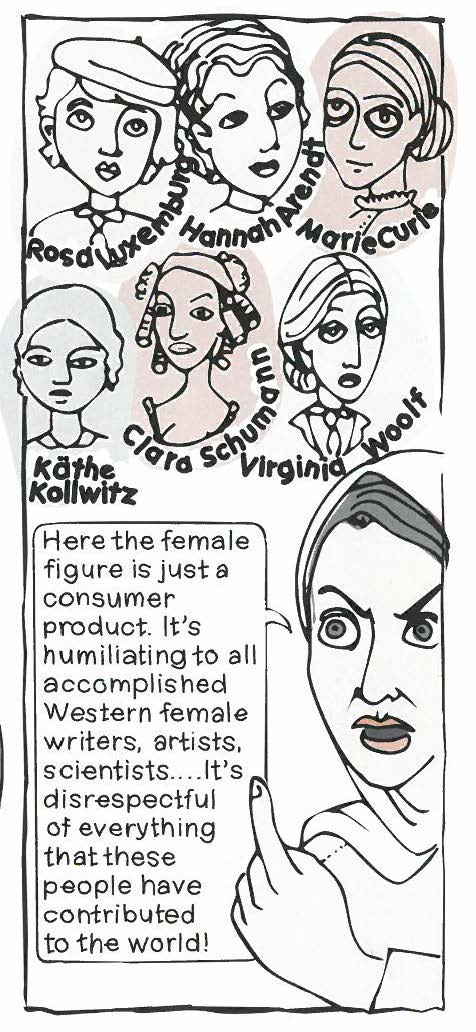

The next former self to confront Parsua is her most recent, the 36-year-old who owned a graphic design studio in Tehran. Europeanized Parsua introduces her as an embarrassing, “almost arrogant” and “loud” feminist (76). But Parsua-36 provocatively extends the comic’s critique of the West, pointing out how even the figures of accomplished Western writers and artists are used as a “consumer product” in advertising campaigns, “selling the female body in public” (Figures 6.1 and 6.2).

From Nylon Road (p. 77) by Parsua Bashi. Reprinted by permission of Kein & Aber AG, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

Her sweeping condemnation further asserts that, at the same time in Iran, brave women defending human rights were imprisoned and even killed, events that Western media sensationalized by representing them as victims in burqa (which are not worn in Iran), among the many ways in which the Western designers of book covers display gross ignorance of Middle Eastern cultures. Yet the narrator’s encounter with “loud” feminist Parsua-36 not only exposes excesses in both Western and Eastern worlds; it also reminds the narrator of the ignorance of citizens of both the global North and South about each other’s cultures: “I learned that not knowing is not a sin. Not knowing and yet being prejudiced is where the problem starts” (79). Although a didactic “lesson,” her point seems apropos, not least for the English version and reception of Nylon Road itself.

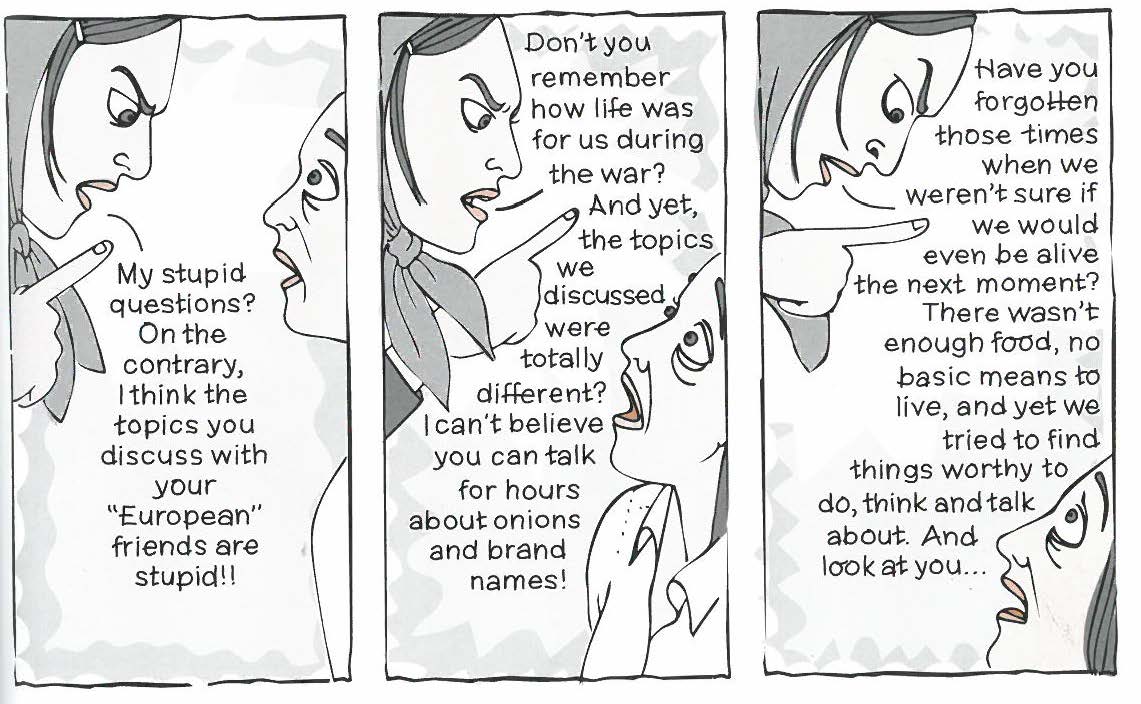

Parsua’s avatars can be harshly critical of the narrator’s seemingly “free” and comfortable status in Zürich, none more so than the 21-year-old Parsua of 1987 in Chapter Eight who appears on the scene to narrate her years of privation during the Iraq-Iran war. The urgent voice of Parsua’s younger self compels the narrating “I” to reflect on the greedy myopia of the Swiss gourmet dinners she now enjoys and her new friends’ preoccupation with vacations and consumer luxuries—like the truffle oil that she tries for the first time in Zürich (84, 88). Parsua reflects on the limits of her past self’s memory, which could not know that in the nineties some things got better in Iran under its fifth president, Khatami (1997–2005)—although repression and human rights abuses intensified thereafter. This lack of perspective, she implies, is shared by both emigrants and Westerners (Figure 7).[22]

From Nylon Road (p. 85) by Parsua Bashi. Reprinted by permission of Kein & Aber AG, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

At the same time Parsua-21 recalls contradictory aspects of wartime life in Iran. On the one hand, food was rationed and oil poured into plastic bags, while in Europe even chocolate is elaborately packaged; there were ration coupons and long waiting lines in markets; and the lack of cosmetics made hygiene a struggle. On the other hand, there was the solidarity of family life for the middle-class families like hers who sewed their own clothes modeled on pre-revolutionary catalogs; took photos to document both war and propaganda; held “exhibitions” of their paintings and photos, watched banned movies, and made live music inside the walls of their homes; and had endless private conversations about the harsh realities of life that generated a kind of everyday intimacy that Parsua finds rare in the commodity-obsessed Swiss world (86–92). To Parsua-21, Europeans are “sissies” (92), unlike the leftists who stayed in Iran and “dealt with the hardship” of everyday life (93). There are of course exceptions in both settings, people who crawl out of what Bashi depicts as European cocoon pods to help others struggling in the developing world (93). As the ongoing dialogue with her former selves makes clear, the claim that either the Islamic Republic or a Western nation is the superior one can be challenged by countervailing evidence. By the chapter’s end Swiss Parsua comes to acknowledge that she survives in her new social world, as in the old, by acts of forgetting and normalizing the burden of accumulated memories.

Reminded repeatedly by her former selves of repressive realities that marked post-revolutionary life in Iran, Parsua remains aware that nostalgia for the past is a form of false consciousness—in what is perhaps a textual barb directed at earlier emigrants. This is also borne out in Chapter Nine, which charts how young Parsua-19’s study of graphic design at Tehran University in 1985, after the universities reopened, was hindered by “conditions where nothing was allowed to be seen or heard” in the aftermath of the revolution’s “explosion of light” depicted on a propaganda poster to ironic effect next to a sign proclaiming “OUR UNIVERSITIES ARE MAN-MAKING FACTORIES,” both of which evoke scorn in Parsua-19 (98). She goes on to narrate the widespread censorship that fine-arts librarians exercised on viewing books about Western artists—such as Egon Schiele, with his provocative naked bodies—that are lined up in her office, and Western design journals. Equally obnoxious were the severe punishments that violating rules on fraternizing with male students or bringing in materials from other countries could occasion. But as Parsua-19 narrates this tale of the universities’ repressive stifling as the “new normal,” she also details the innovative kinds of resistance that it spurred. The chapter’s drawings of posters, books, magazines, and videos, as well as the caricature of the library’s monstrously “fat, spinsterly, old virgin” (97) and malevolent director, texture its narrated memories as both vivid and tough, driven by the students’ shared determination to learn about a wider world of arts and cultures in the West and subvert their supervisors, often at personal cost.

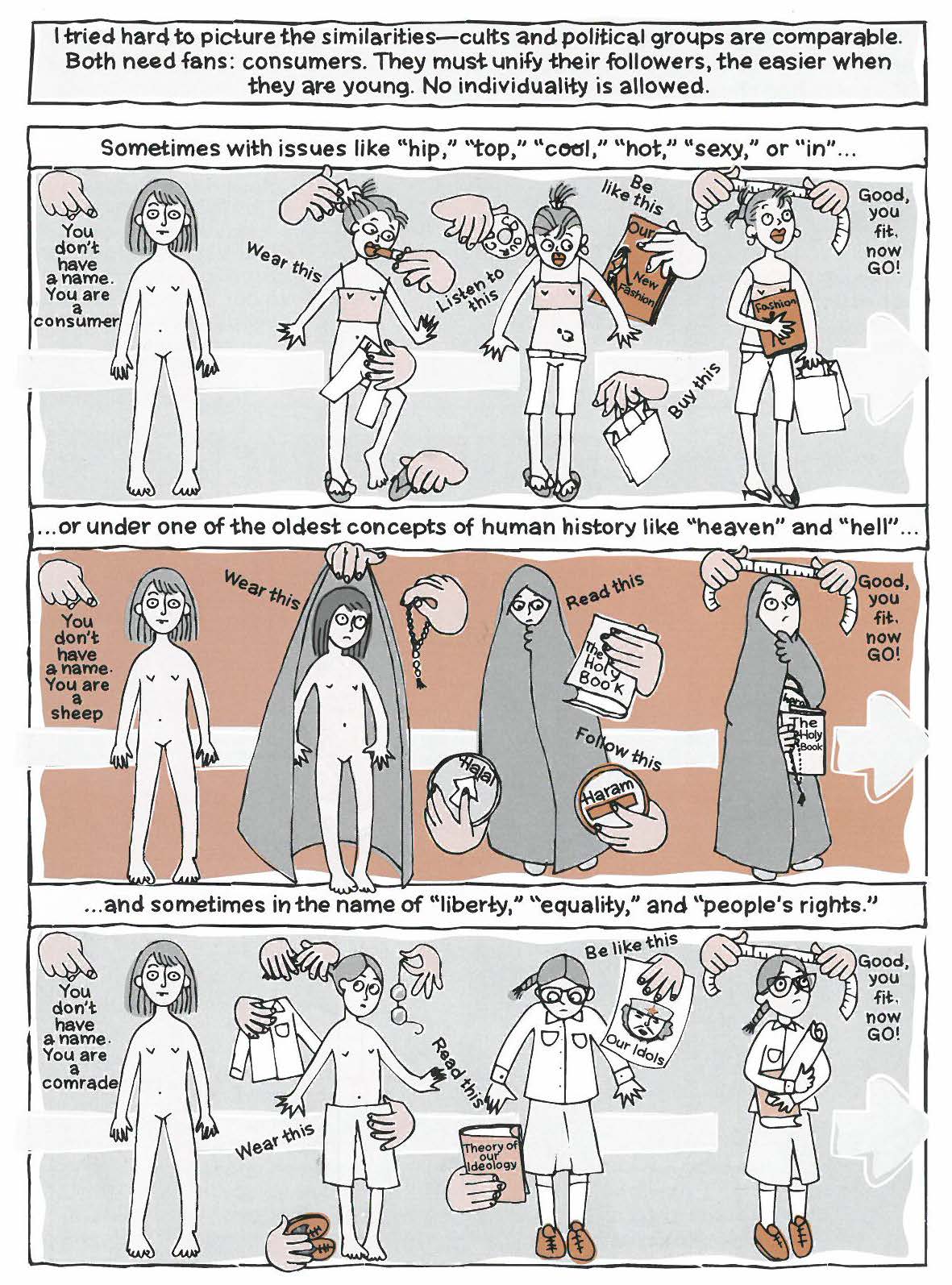

As Nylon Road expands its critique toward broader political and ideological targets, the narrating “I”’s harshest critic emerges in the pigtailed teenaged self of Chapter Ten. Parsua-13 speaks from the position of the heady moment in 1979, just after the Iranian Revolution began, when she chose, among the available versions of leftist theory, to identify as a Marxist-Leninist and immersed herself in its prescribed reading of Marxist classics (103–05). But Parsua, as narrator, ironically mocks the teenager’s study of party tenets, texts, and mandated practices of group “self-criticizing” (106) and body-building as “A teenage fashion just like any other,” comparable to the fad—and pain—of getting a tattoo (109). From Parsua-13’s perspective, however, Europeans are superficial. They can be split into the bourgeoisie and the proletariat, the latter with no access to agency, their personal styles reflecting gendered and classed forms of oppression. As a rejoinder Bashi’s full-page drawing suggests that the teenager’s study of “dialectical materialism” was useful in getting her own way in the family—in the name of “rights,” in a family scene where competing viewpoints were tolerated as her father listens to the BBC World Service on the radio (108). But while Parsua-13 rejects seeing the martyred youth of Iran in 1981 as following a “fad,” Parsua the narrator defends her view in a startling way: she compares the fate of the youth in Iran to the ways that capitalism conforms young women to styles of dress and behavior that also repress individual expression, a form of what Marcuse termed “repressive tolerance.”[23] In the narrator’s view political positions are inevitably compromised because they are embedded in the ideologies of specific regimes and political moments.

Parsua-13 also offers a novel defense of her point of view in this debate, visualizing a fantasy of young women costumed in different garb to display capitalist, religious-fundamentalist, and socialist modes of conforming girls to three kinds of ideological “cults” (Figure 8). Each kind of costuming produces consumers who suffer the disciplinary effects of their interpellation in the unquestioning adherence that governments demand. Parsua sums up this critique of “the power of wealth” to shape political belief in her contrast of three kinds of regimes, as embodied in their leaders: “fashionista” capitalism crowns designer Karl Lagerfeld; the Islamic Republic honors the Ayatollah; and Soviet-style socialism heralds Stalin—all with wads of money in their hands (112). While Parsua-13’s Marxist self cannot be reconciled to the narrator’s critique by an offer of ice cream, Parsua concludes the chapter with a powerful insight: despite her selves’ bickering about positions, a “lost childhood” was the price of her early fervor during the Revolution (112). Interestingly, Chapter Ten suggests how deeply Bashi, as a teenager, was steeped in dialectical materialism, training that surely contributed to Nylon Road’s dialogical structuring and use of visual counterpoint.

From Nylon Road (p. 110) by Parsua Bashi. Reprinted by permission of Kein & Aber AG, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

The most provocative avatar of all steps up in Chapter Eleven: Parsua’s 33-year-old self, now a graphic designer who has been awarded her first prize (117). She is interested in Western fashion but becomes angry when the narrating “I” shows her a spread in Vogue entitled “Colonial Girl,” featuring “Calcutta Cat” and “Delhi Doll,” derived from women’s garb in colonial India (116). While contemporary Parsua defends free expression, tolerance, and the celebration of difference as practices enshrined in the West, Parsua-33, a tough and self-assured urbanite, searingly critiques the cynicism of the global fashion industry sustained by colonial and racist practices that emerged with the Enlightenment and the modern nation-state. Fashion magazines, Parsua-33 alleges, “make a profit from their own crimes of history by pretending that colonialism was just an aesthetic phenomenon” (116). Disgusted at the fascination the narrating “I” exhibits for Western consumerist fashion, however, this younger self alleges that the narrating “I” is blind to how cynically the West levels and commodifies history as a fashion statement.

When the narrating “I” contrasts the freedom of artists to criticize politicians in Europe with the fundamentalism that constrains artists in Iran, Parsua-33 begins to taunt her about the manipulative tactics of Western advertising. À la layouts in the fashion pages of Vogue or Elle, this younger self visualizes a fantasy depicting fashion lines of “Sweet Slaves,” complete with manacles and chains (121); “Hot 9/11" with models wearing Twin-Towers-explosion T-shirts; and models with shaved heads and Holocaust-camp shirts. As the two Parsuas’ heated debate about the conundrum of “free” speech continues, Parsua-33 argues that the Eurocentric West ignores taboos on trivializing genocidal acts that are Indian-, African-, or Asian-related even as it valorizes Eurocentric events (123).

Their debate, located at what Spiegelman called the “intersection of personal and world-historical events,” focuses the narrator on the blind spots of belief systems, all of which construct an “other” and set limits to the critique of their own histories (Spiegelman, In the Shadow, unpaged). But at the end of their dialogue Parsua remains stymied, like the narrating “I” at the crossroads depicted on Nylon Road’s original cover, between the clashing systems of different cultures and traditions. Finally, reconciliation with her last self is impossible. When Parsua as narrator poses the irresolvable conundrum of freedom and censorship that—for her—constrains the exercise of democratic freedom in societies in various ways, Parsua-33 responds, “Why bother writing a book? Why not just shut up? . . . your theories are BULLSHIT!” (124). In a witty graphic metalepsis, Bashi captures the chapter’s lack of closure with the narrating “I” jumping out of the comic page on which she is drawn jumping out of the page, chided by finger-pointing Parsua-33 (124). Completing the spectrum of attitudes of her former selves, some of them echoed more widely in their social milieu, Bashi represents Parsua as at an impasse—and yet, her narrative of the challenges that both post-revolutionary Iran and the “civilized” West pose has unfolded in specific and compelling detail.

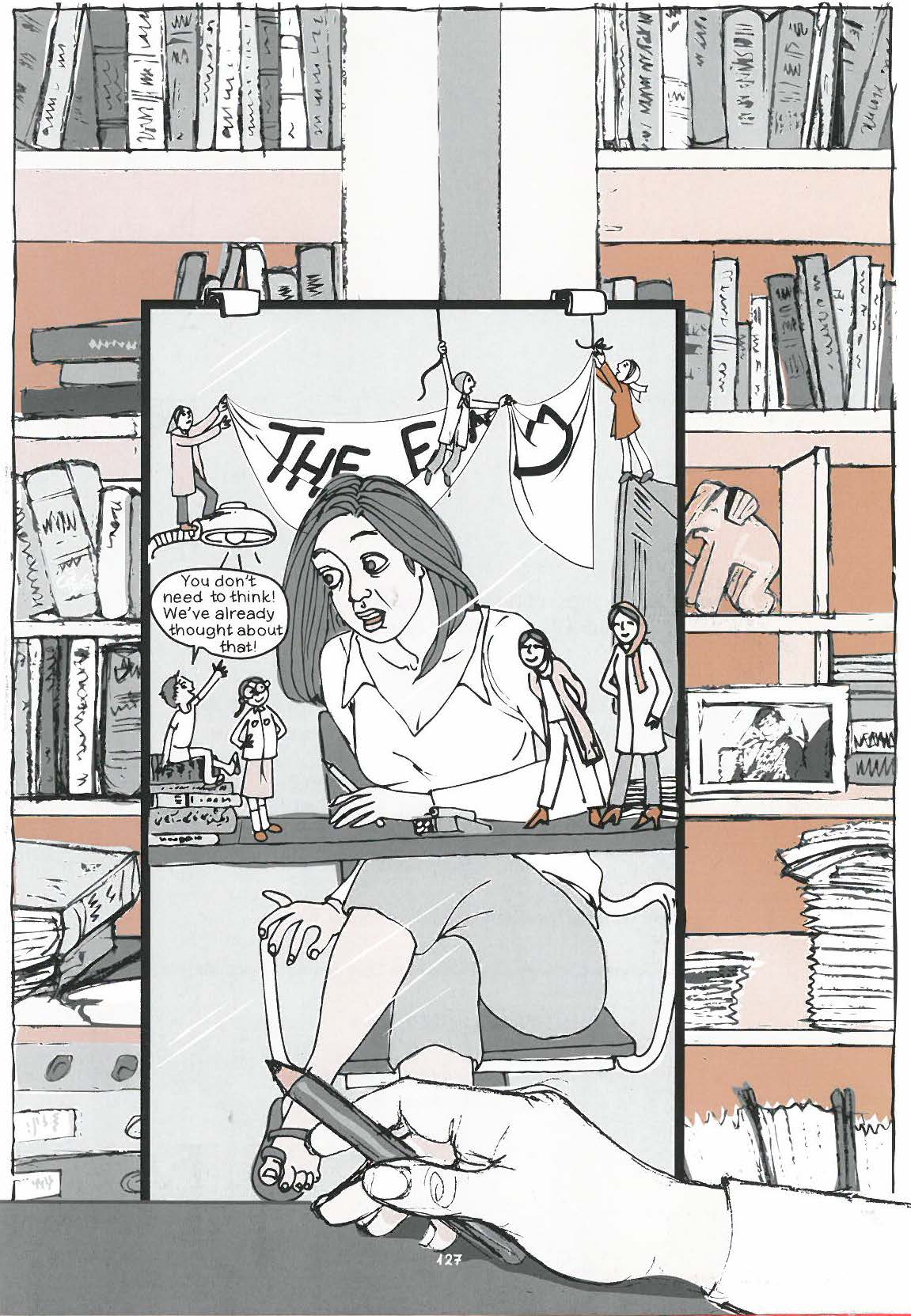

Nylon Road’s brief final Chapter Twelve consists of facing pages that juxtapose alternate views of Parsua the narrator. On the left side, in nine close-up portraits, Parsua is visualized full-face, smoking and pondering how to conclude her story in a way that is funny and provides closure but is not “paranoid,” “two-faced,” or “simply crazy” (126). The rejoinder on the witty right page is a self-portrait in which seven of her collective younger selves, led by the six-year-old, orchestrate an end to her process of self-reflection by holding aloft a banner reading “The End.” A picture within the picture, this group of little figures surrounds a self-portrait of Parsua the narrator that is clipped onto the bookshelf in her study. Below it her drawing hand appears in profile, at rest and holding the pencil for Bashi’s comics drawings (Figure 9).

From Nylon Road (p. 127) by Parsua Bashi. Reprinted by permission of Kein & Aber AG, and Parsua Bashi. All rights reserved.

A metaleptic gesture familiar in autographics and other forms of self-portraiture, from Dürer and Parmigianino through Van Gogh and Kollwitz, this last panel emphasizes the recursive nature of graphic storytelling. (See further discussion of the graphic in the “Toolbox” below.) That is, Bashi represents herself as an artist-maker performatively. In this binocular structure, the narrating “I” of the comic is revealed as a projection of the agent who has drawn, written, organized, and edited her memoir, as the hand drawn by her invisible hand signifies. Further, as the drawing suggests, Parsua is as much an effect of her former selves as she is a speaking subject—and thus still a subject in transit. In true dialogical fashion this visual and narrative self-examination cannot be resolved into the coherent, consolidated self as public citizen of the Western Bildungsroman. Rather she remains an open possibility at the nexus of memory and narration. Far from serving as an authoritative visual and textual life story about either belonging in, or migrancy from, Iran, Nylon Road presents an “I” who both asserts her role in directing the narrative and is unmasked as a constructed fiction by her past. Assembled at the expense of acknowledging and incorporating—but struggling in creative tension with—past “forgotten” versions of herself, she remains a locus of competing claims about the “truth” of her experience.

In sum, throughout Nylon Road, Bashi uses conversations with her former selves to set up and intensify a dialogical structure of interrogation that is both personal and political. Neither her present-time “I”, nor any of her past selves, emerges as “right,” the victor in this clash of views. But through the lens of graphic memoir the succession of encounters serves to problematize questions of identity and belonging for the narrating “I” as a migrant subject in Zürich. Both the roles of leftist Iranian resister in the Islamic Republic and liberated Euro-migrant trouble her. In that sense Nylon Road is a story of the narrator’s inadequacy to construct a coherent identity either at home or in Europe; both versions are inadequate, inauthentic from the other’s point of view. Yet, as in many transnational narratives, Nylon Road’s confession of unease with residing in either past or present social identities bares an in-between space that is generative of its graphic dialogism. Parsua’s determination to be neither nostalgic nor in denial about her past experience in Iran sets up a colloquy of selves in a debate about whether to invest in any prevailing political ideology—even as one is inescapably interpellated by those informing the location one inhabits.

Thus Nylon Road poses issues for both readers of the Iranian diaspora and those in the West. At the same time that Nylon Road acknowledges—in often funny and sometimes harrowing detail—the post-revolutionary excesses and blind spots of the Islamic Republic, it also suggests that neither Western market capitalism nor Soviet-style socialism can adequately redress forms of prejudice toward outsiders and violence toward women. And it resists, through its dialogical structure, the binary logic of much testimonial memoir in which the West serves as the locus of rescue for Middle Eastern emigrants. In Bashi’s dynamic and ever-incomplete project of self-invention, Parsua’s multiple, unresolved selves signal that the consolidation of a transnational identification occurs at the cost of letting go of memory in order to belong. Particularly in light of Bashi’s 2009 return to Iran, her ironic rendering of violent repression in the Islamic Republic of Iran, compulsory conformity under Soviet socialism, and materialist excess in the name of tolerance in the West, leaves readers with provocative questions about whether any “elsewhere” can serve as a locus of adequate rescue for democratic values. Forming a moving target of self-representation, the dialogical narrative organization of Nylon Road offers a view of self-construction that, in the act of reconstructing memory through situated witnesses embodying particular standpoints, links the personal inextricably to the shifting global currents and contexts that texture it.

IV: A Toolbox for Reading the Drawn Autographic Witness

Autographics offers unique resources for representing the contradictions of multiply inflected subjectivity as a mosaic of self-reflection in ways that verbal narration cannot fully capture. Because Bashi was primarily a graphic designer rather than a comics artist, she had to devise a set of visual codes for representing the psychological complexity of her process of engaging memory as an unhappy diasporic subject caught between dramatically different worlds. In my view she sought visual means that would both stylize the appearances and attitudes of her past selves at significant ages and correspond to key moments in pre-and post-revolutionary Iranian history. These embodied former selves, necessarily repressed in her post-migration life, cumulatively pressure Parsua’s recognition of contradictions of her experience. Bashi’s efforts to visually encode autobiographical reflection about her conflicted position as a remarried Iranian woman artist in Zürich are worth further consideration. What is her vocabulary of visual tactics and tropes, and is this repertoire shared with other autobiographical comics?

By asking this, I am implying that the question of how comics represent the autobiographical is a complex one. Drawing pictures that resemble the artist making the comic is not a display of self-reflexivity, nor is simply including fragments from memory archives such as letters, diaries, or photographs. Rather, depicting an autobiographical act of self-reflexivity requires an artist-author to devise a narrative “mirror” that she can turn back on herself. After Parsua’s initial question, “How could I have forgotten me?” (15), the eleven selves that appear enable her to stage encounters in which neither the narrating “I” nor her many past selves can claim to be the authoritative version of her own, or Iran’s, past. Instead, the encounters staged between present and past versions of herself as they discuss, and often dispute, the meaning of experience, produce a dialogical narrative that proceeds by recursive twists and turns.[24] The dialogue that Nylon Road conducts among Parsuas is both interior—about the shifting meaning of the past depending on one’s location—and public, linked to Iran’s history. It presents the narrating “I”, a Europeanized cosmopolite in Zürich but also a migrant, as both insider and outsider making a critique of women’s experience that is ideologically charged in ways not adequately reflected by global media.

The set of terms I propose parses the autographic strategies Bashi employs in drawing Parsua in relation to her embodied past selves in Nylon Road. This vocabulary of visual distinctions can be seen as a kind of “toolbox” for autographic representation, and may offer rubrics for thinking about visual tropes in graphic memoir more generally.

The processual “I” shows the narrating “I” as a developmental aggregate, the culmination of a series of past selves at different moments that are lined up behind her, for example, on the bottom of page 18, which is also used as the cover of the English edition of Nylon Road (see Figure 2). This stylization depicts identity as a chronological process that proceeds in a linear, organically developmental fashion toward consolidating a present I.

The conflictual “I”, by contrast, represents the narrating “I” as a product of disparate and competing identifications—as on the cover of the original German edition and its Spanish translation (see Figure 1). There, each of Parsua’s crossed legs is clad in a nylon stocking covered with characters and word fragments in a different alphabet, and the contrast of Persian and Roman scripts locates her at a crossroads between her Iranian legacy and the Greco-Roman heritage of democracy and capitalism. So clad, she embodies the conflict of ideologies and cultures that she has experienced—in the humorous form of pantyhose.

The indexical “I” signals meta-level reflexivity in embedding one or more visual replications of the narrated "I" in a particular box or panel. Thus, a photograph or drawing of a past “I” can serve as a mirror-avatar for the narrating “I”, but also heighten the contrast between past and present I’s. For example, Bashi incorporates a portrait of her younger self from a photo album, “Tehran Autumn, 1989,” as a sweet-faced girl in a hijab who was not allowed to show affection to her boyfriend in public under the laws of the Islamic Republic, in contrast to the free expression of couples the narrating “I” observes in Zürich (38). Satrapi similarly uses many portraits of her younger self as visual icons in photographs, paintings, or mirrors within the frame, particularly in Persepolis I.

The dialogical “I” can be visualized in various ways. Within a frame Bashi often creates a multifaceted self-portrait by juxtaposing several heads or bodies of the narrator to depict different-aged selves as in conversation with one another. For example, when Parsua, reflecting on her migrant status, describes herself as a “useless asshole,” Bashi places four free-floating drawings of herself at loose ends within a single box (12, bottom; see Figure 3). The drawing externalizes her self-critical interior monologue as a set of faces that are set alongside, but not literally “speaking” to, one another on the same visual plane. Rather than being developmental, these self-portraits of the unsettled, unresolved narrator represent her as a set of discontinuous, dissonant personae.

But dialogism can also be signaled in a succession of boxes that juxtapose past and present "I"’s in conversation, sometimes using filmic techniques of positioning one disputant at the top of the frame and switching her location to a bottom corner as the other responds. In some text-rich panels Bashi focuses on talking heads in profile or three-quarter view as they trade views on an issue such as artistic freedom.

The interpellated “I” is presented through a multi-panel box or page that embodies different belief systems in the appearances and attitudes of young women. For example, Bashi draws a girl wearing differing costumes to depict a contrast of global ideologies—Western neoliberalism, Islamic fundamentalism, and socialist utilitarianism (110; see Figure 8). Her costuming literally fashions the personae inhabiting them as a kind of interpellation conforming young woman to identities as, variously, “consumer,” “sheep,” and “comrade” whose performances are mandated by powerful interests that enforce membership in a national “cult” (she acknowledges Islamic fundamentalism as a particularly repressive one). For each figure, the instructions are the same: “Wear this . . . Read this . . . Be like this . . . Good, you fit”(110). Bashi turns this criticism on herself as well, stylizing Parsua-13 as trying on seven styles of radical resistance circulating in Iran in the seventies before she opts to become a “Marxist-Leninist” (103).

The recursive “I” can be presented by visual self-reference, and is a frequently-used convention of self-portraiture in both painting and cartooning. In it a portrait of the narrating “I” includes the maker’s hand, either in the act of drawing or in repose, as a reference to the artist’s body drawing the comic outside the frame. In suggesting that a self-image must be drawn by another invisible hand, a drawing of the artist’s hand is an example of what narrative theory terms “metalepsis”; such images create a mise-en-abîme or recursive circuit of self-representation. (Recall the famous M. C. Escher graphic of “Drawing Hands.”) Such cartoonists as Alison Bechdel and Art Spiegelman employ this trope as a visual signature. For example, a famous full-page box depicts Art, the artist drawing Maus, as he sits atop a heap of corpses in the shadow of a Holocaust watchtower (Maus II, 41). Bashi’s final full-page box similarly depicts the drawn narrating “I” in a picture surrounded by little drawings of seven earlier selves who, as an ensemble, surround the present-time narrator as if she is their creation. (127; see Figure 9 and related discussion in III). They present Bashi’s narrating “I” as recursive, a performative construct produced at the nexus of the disparate histories of her past selves. Yet the drawn hand of the artist, visible below this group self-portrait around Parsua, also unmasks Bashi as the maker of Nylon Road’s visual dialogics.

In sum, Bashi productively exploits the affordances of graphic memoir for self-presentation by employing visual tropes that represent self-relationship in encounters among her various selves across disparate times and places. As Chimamanda Ngozi Adichie has asserted for written narrative, the depictions of a self in migration across locations, histories, and ideologies, cannot be “just a single story.”[25] Bashi’s multiple apparitions in the selves of memory require a repertoire of visual tropes, on dazzling display in Nylon Road.

V. Conclusion

Narratives structured as debates about the position of the autobiographical subject vis-à-vis her own and national history, whether written or in the visual-verbal form of graphic memoir, can be challenging to follow. Publishing in 2006, Bashi used an open-ended dialogical structure to depict her relationship to her homeland, Iran, and her post-migration life in Switzerland, ensuring that, while Nylon Road was written in the West, it is decidedly not “written for the West.” The comic provocatively suggests that, for transnational subjects, questions of audience and allegiance may be so fraught with ambivalence that the authority of any single version of an experiential history is troubled.

As a kind of feminist counter-comic, Nylon Road thus critiques not only the severe strictures that its narrating “I”, Parsua, experienced and that were imposed on women under the Islamic Republic, but also those implicit within the “repressive tolerance” of Western consumer capitalism that she encountered as an expatriate in Zürich. As a collective trope for the variation and embeddedness of memory, Bashi’s eleven avatars, in dialogue with her rather than static portraits frozen in memory, both innovatively juxtapose diverse ideological perspectives on the past and trouble nostalgic versions of it. Its intricate charting of how reawakening memory activates the narrating “I”’s questions about identity is a bracing tonic to a rose-colored glasses view of either home or adopted nation.