Life Writing in the Long Run: A Smith & Watson Autobiography Studies Reader

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

11. Autographic Disclosures and Genealogies of Desire in Alison Bechdel’s Fun Home (Watson 2008)

Gillian Whitlock has observed the “potential of comics to open up new and troubled spaces” (“Autographics” 976). Alison Bechdel’s autographic memoir Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic (2006) is such a text, a provocative exploration of sexuality, gendered relations in the American family, and Modernist versions of what she calls “erotic truth” (228). It both enacts and reflects on processes of autobiographical storytelling, and exploits the differences of autographic inscription in the art of cartooning. Bechdel is a well-known American feminist cartoonist who for over two decades has published the politically savvy lesbian-feminist syndicated comic strip “Dykes to Watch Out For.”[1] In taking up the graphic memoir form, she composes Fun Home in seven extended chapters that are beautifully drawn in black line art and gray-green ink wash. It is a dazzlingly and dauntingly complex set of interconnected life stories, modes of print text, and panoply of visual styles. A memoir about memoirs, memory, and acts of storytelling, Fun Home is at all times an ironic and self-conscious life narrative. It hovers between the genres of tragedy and comedy, as its subtitle “A Family Tragicomic” asserts and its project of affirming the family despite and because of her father’s history avows.

Fun Home’s title refers to the family’s mid-century funeral home in the small town of Beech Creek, Pennsylvania, near the Allegheny front, where Alison is the eldest child and only daughter in a family with three children. Their father Bruce is the funeral home’s director and mortician; additionally, both parents teach high-school English. “Fun Home” as a concept also evokes a fun-house of mirrors, which the family’s restored Gothic Revival home proves to be as a psychic incubator for Alison’s story. Fun Home reworks this experience in an autobiographical act of retrospective interpretation that is multiply embedded: in the familial network of other lives; in the psychic pull of deep identifications around gender and sexuality; in the commingling of literary and popular identity discourses that intersect in particular ways at a given historical moment; and in the interplay of views on and views of the artist-maker as a self-construction always in process, in the reflexive exchange of hand, eye, and thought. As Nancy K. Miller observes, “Autobiography’s story is about the web of entanglement in which we find ourselves, one that we sometimes choose” (“Entangled” 44, my emphasis). By working on and working through several aspects of the generational, personal, psychosexual, and political entanglements of family life, Fun Home maps new ground in life narrative.

Fun Home is, however, fundamentally different from verbal autobiography. By engaging with and drawing a range of visual forms, Bechdel emphasizes that cartoon representation, as a genuinely hybrid form or “out-law” genre of autobiography in Caren Kaplan’s term, is a multimodal form different from both written life narrative and visual or photographic self-portraiture.[2] At the same time it is intertextual, incorporating a wealth of Modernist literary references into comics that turns the form into a forum on the multi-textual pastiche of contemporary culture. As a result, Fun Home invites—and requires—readers to read differently, to attend to disjunctions between the cartoon panel and the verbal text, to disrupt the seeming forward motion of the cartoon sequence and adopt a reflexive and recursive reading practice. As Hillary Chute and Marianne DeKoven argue, “comics is constituted in verbal and visual narratives that do not merely synthesize. . . . The medium of comics is cross-discursive because it is composed of verbal and visual narratives that . . . remain distinct” (769).[3] Gillian Whitlock has coined the term “autographics” to call attention to the representational strategies of graphic memoirs and the vocabularies mobilized by the possibilities of cartooning. Whitlock observes, “I mean to draw attention to the specific conjunctions of visual and verbal text in this genre of autobiography, and also to the subject positions that narrators negotiate in and through comics” (“Autographics” 966). Fun Home’s improvisations upon the terms of autobiography in its graphic disclosures draw on the hybrid form of autographics to explore complex formations of gender and sexuality in the modern family.

The practice of composing autobiography implies doubling the self, as its practitioners, from Montaigne on, and critics, notably James Olney in Metaphors of Self, have long observed. That splitting of self into observer and observed is redoubled in autographics, where the dual media of words and drawing, and their segmentation into boxes, panels, and pages, offer multiple possibilities for interpreting experience, reworking memory, and staging self-reflection. Whitlock has proposed the provocative term “autobiographical avatars” to characterize the drawn personae of cartoonists in graphic memoirs, noting how their self-reflexive practices use cartoon drawing not only as a form of self-portraiture, but to “engage with the conventions of comics” (“Autographics” 971). The term “avatars” recalls the new popular media of unstructured virtual role-playing environments such as Second Life, where game players choose visual self-representatives (called avatars), often quite different from themselves, to play roles and interact in virtual space; as such, the avatar implies new possibilities for forging identity in autographics.[4]

The way we read cartoons, as a pleasurable alternative to high seriousness, also affords occasions for reader identification with characters and situations that solicit our autobiographical intimacy. In commenting on Scott McCloud’s argument about the cartoon as a “vacuum into which our identity and awareness are pulled,” so that instead of just observing the cartoon “we become it” (36), Whitlock suggests how differently autobiographical practices work in this verbal-visual medium (Soft 191). Representation of the artist’s face in particular, she observes, may serve as an icon that elicits identifications with our own image, thereby changing the reader-viewer experience. And this process of recognition in cartooning assuredly resonates for the artist-autobiographer as well. As Jared Gardner observes, “comics do open up (inevitably and necessarily) a space for the reader to pause, between the panels, and make meaning out of what she sees and reads” (“Archives” 791), thereby serving as “collaborative texts between the imagination of the author/artist and the imagination of the reader who must complete the narrative” (“Archives” 800). Fun Home calls upon readers to be literate in many kinds of texts—not only comics and Modernist literature but feminist history and lesbian coming-out stories, as well as many modes of the decorative arts—as a sophisticated and politically impassioned community.

Notes Toward a Reading—Graphing the Split Subject of Fun Home

As a self-reflexive autographic, Fun Home’s narrative world is bisected by “splits” of several sorts. Some are enabled by two structural principles: the resonance between the autobiographical avatar Alison and her father Bruce, as the telling of her life is shadowed by the mysteries of his; and the autographic play between the graphics of Alison’s and her family’s story inside the comics’ frame and the ironic detachment of the discursive narrator Bechdel’s voiceover comments in boxes above. But Bechdel’s elaborately constructed narrative framework goes beyond notions of what a “relational autographic” might imply. (Indeed, the notion of relational life narrative is both too capacious and too vague, as Nancy K. Miller has suggested—a fuzzy concept we might abandon in order to think more precisely and creatively about how the autobiographical plays out in family stories.[5]) The narrative set-up of Fun Home depends on both the perception that characters occupy opposed positions and the eventual dissolution or reversal of these apparent binaries in a process that Bechdel, drawing on Proust, calls a “network of [narrative] transversals” (102). To chart a way through the intriguing complexity of Fun Home, I want to briefly suggest several sites of “splitting,” before going on to discuss the autographic interplay between drawn photographs and cartoons that underwrites Bechdel’s mapping of sexual legacies over generations. The following series may offer prospects for further theorizing.

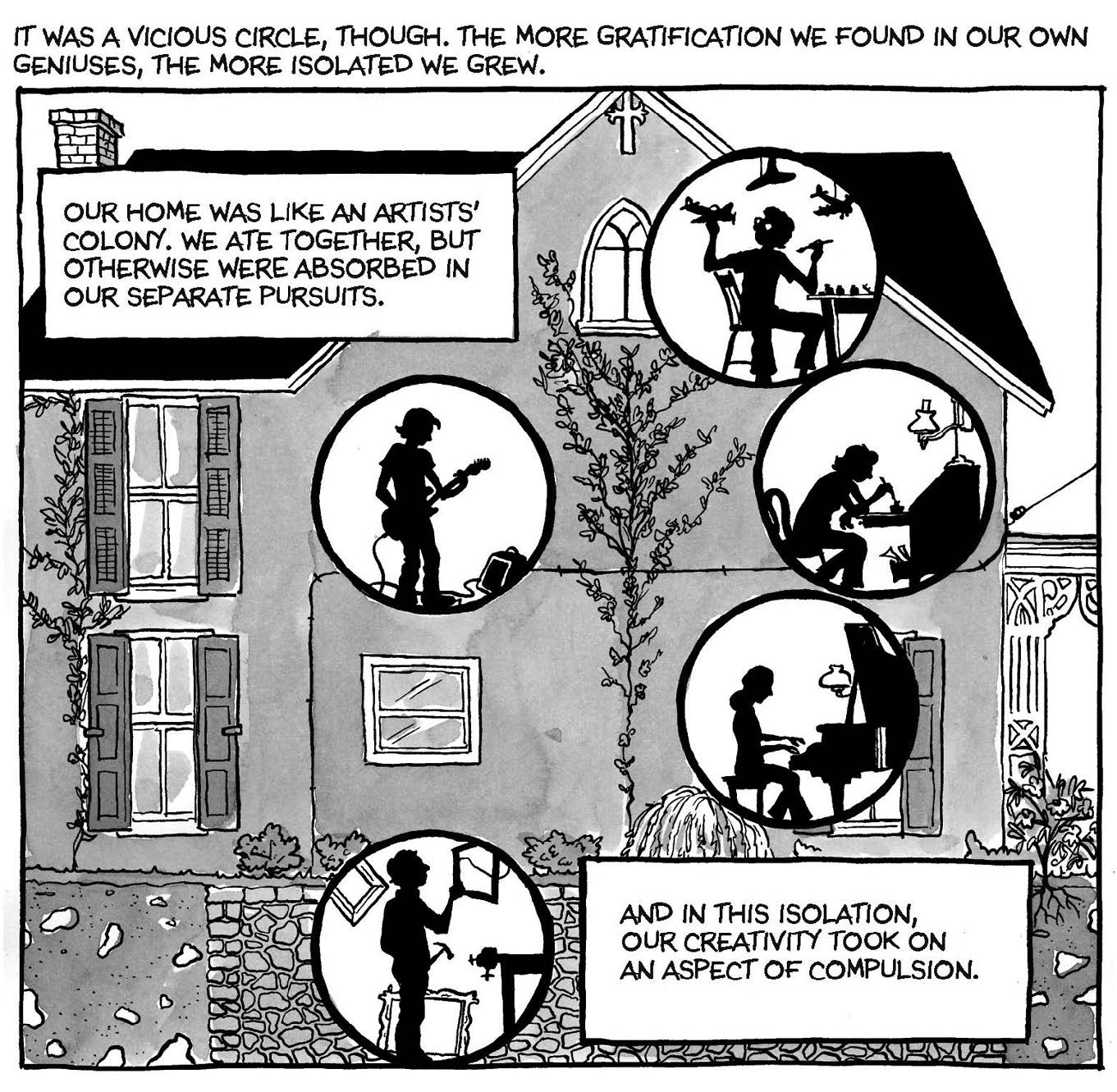

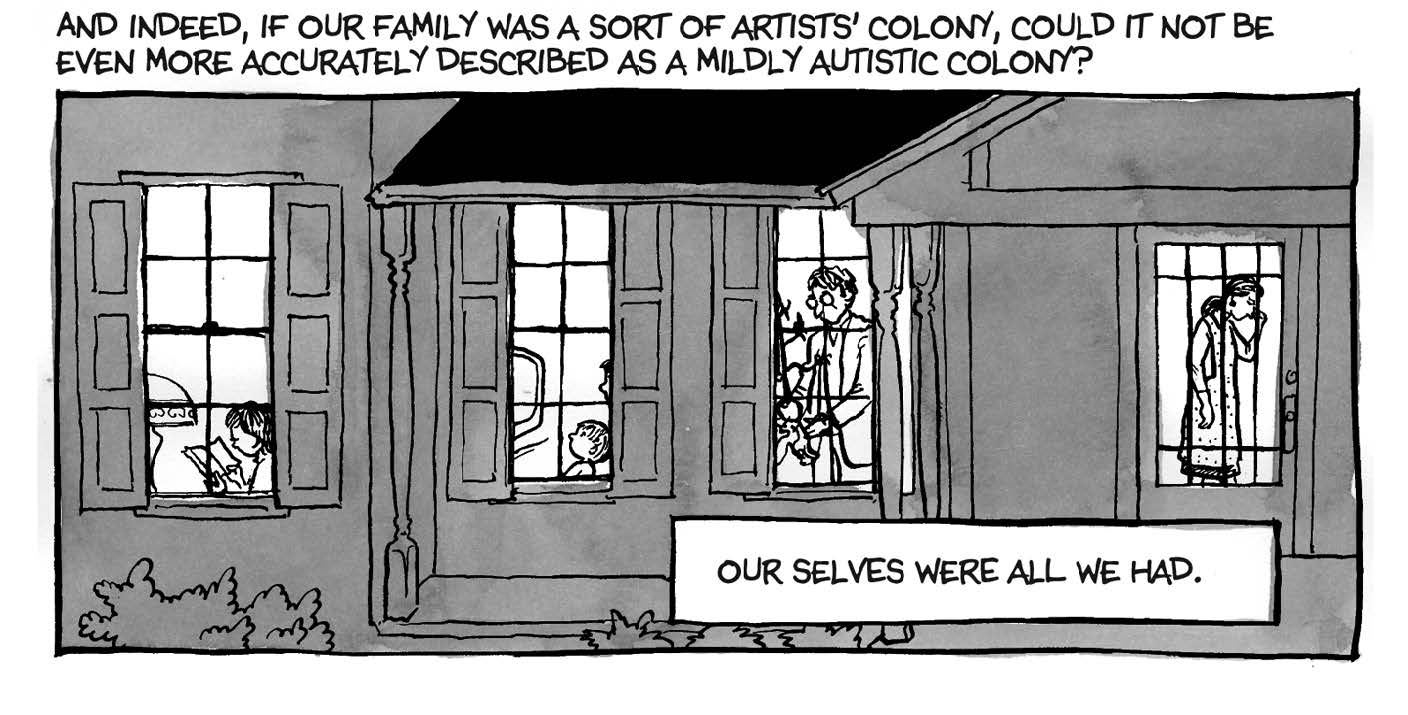

The narrative is split between a solo story, Bechdel’s child narrator Alison’s development of an “I,” and the domestic ethnography of the family, punningly presented as both artistic and autistic (Figure 1).[6] This “dysfunctional” unhappy family evokes a literary tradition of the modern novel, referenced in the copy of Anna Karenina lying on the floor on the first page of Chapter One. The family’s oddity is not only experienced by young Alison, who at ten develops obsessive-compulsive disorder (OCD); it is also diagnosed by her, in her dual role as patient and therapist, trying to parent her parents via Dr. Spock’s famed manual Baby and Child Care. In a further conflation of identities and intertexts, she situates her narrative as a reworking of the Icarus-Daedalus myth, telling a story of her relationship to her father in which the parental and child positions are complexly reversed, and the inheritor of the parental legacy—who, in an inversion of Icarus, survives—is a woman.

Excerpted from FUN HOME: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (top: p. 134 bottom; bottom: p. 139 bottom). Copyright © 2006 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

In a different sense the narrative acknowledges its origin as split between verbal and visual modes of diary-keeping, suggesting Bechdel’s dual aspiration to become a writer and an artist. After Alison’s father urges her to keep a journal when she is ten to help manage her OCD (initially on a wall calendar from a burial vault company, 140), she faithfully keeps a diary for years. It is initially a non-committal record of events, but with puberty, becomes a site to encode discoveries about her lesbian identity, aided by library books on coming out that open a new world to her. But the preteen notes she dutifully jots down are gradually engulfed by the emergence and persistence of a “curvy circumflex” (143), an upside-down “V” that marks moments of subjective doubt, as Jared Gardner discusses (Biography 3–5). As Alison’s diary drawings, like a palimpsest, come to engulf her tentative verbal narrative, Bechdel’s story of coming to artistic consciousness is visually mapped. Fun Home, as an autobiographical Künstlerroman, glosses Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist, with Stephen Dedalus as one alter ego for Alison; but it also remakes the genre’s emphasis on forging language in the smithy of the artist’s soul by emphasizing Alison’s fascination with the image, cartooning, and visual detail generally as a means of both perceiving and representing her world. We might ask how the current outpouring of comics about becoming an artist modifies our assumptions about the Künstlerroman as the story of the growth of artistic consciousness.[7] As a narrative form particularly widespread among women practitioners of the “New Comics,” the artist’s story can be reworked to tell ethnically specific stories, as Melinda Luisa de Jesús has observed.[8]

Furthermore, Fun Home, as an origin story, makes a genealogical connection between Alison’s efforts at parental management and pleasure in visual record-keeping and her father’s compulsive personality, shown in his archivist habits—his elaborately decorated personal library (drawn in exquisite detail with embossed wallpaper and busts of writers), his meticulous attention to personal records, his artistic bent expressed in fastidious house-decorating and gardening, and his precision as a mortician. The story of “blood” as the legacy of character and desire, linking the artistic and the psychosexual, is thematized as an explanatory myth that, when understood, enables Alison to incorporate a past she initially did not understand and could have feared or despised. And the genealogical narrative casts back speculatively through generations of her father’s family to link land, immigration, and childhood experience to the formation of subjectivity.

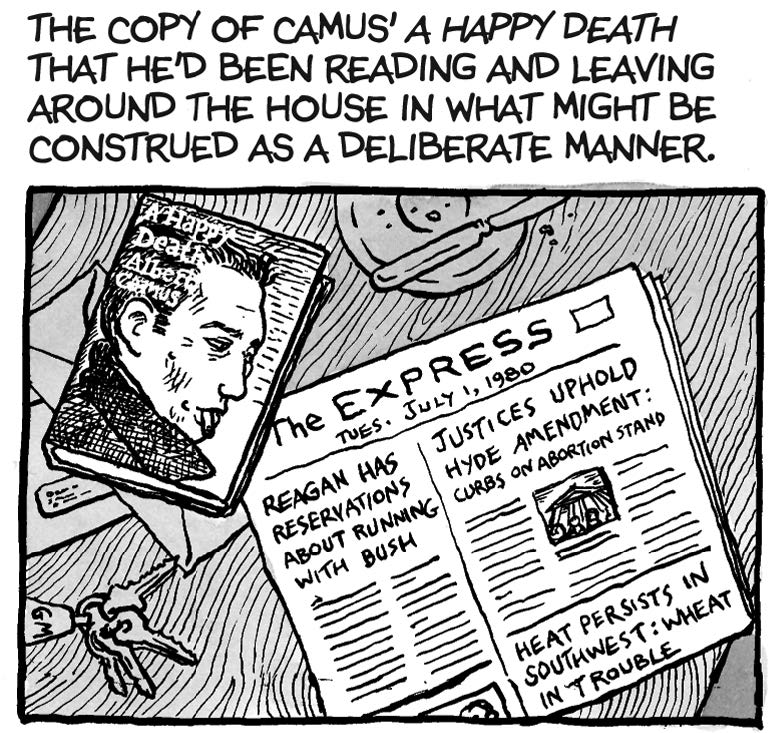

Located at the “split” or juncture of disparate media, Fun Home also exploits, through multilayered visual play, the flatness of the page by introducing three-dimensional depth into the frame. Its dazzling textual collages of drawn objects often interact to form a kind of meta-commentary on the comic page as a site of intertexuality. The panels, gutters, and page, as bounded and delimited visual space, allow texturing of the two-dimensional image through collage, counterpoint, the superimposition of multiple media, and self-referential gestures (such as the drawn hands holding pages that I discuss below). Bechdel’s rich exploitation of visual possibilities places Fun Home at an autobiographical interface where disparate modes of self-inscription intersect and comment upon one another.[9]

For example, at the start of Chapter Two (the bottom of page 27), a drawn cover of Camus’s A Happy Death, the book her father was reading when he died, overlaps The Express, the local newspaper referencing the month of her father’s death. Both lie on his desk with car keys and letters (Figure 2). A kind of still-life memento mori, it refers back to another copy of The Express at the top of the same page, dated two days later, whose headline proclaims her father’s death after being hit by a truck. This texturing situates the memory of the everyday in its lived density and poignancy and registers it as a visual archive.[10] Fun Home is an encyclopedic display of visual modes, from detailed topological maps and schematic charts to drawings of notebooks, notably Alison’s diary, incised within the frame on the page we are reading. Bechdel also adopts the tagging style of other cartoonists occasionally as a kind of intertextual riff. For example, a frame depicting the “fragrances” of Greenwich Village that the family encounters on a visit marks the odors with seven rectangular tags, referencing Julie Doucet’s irreverent style of cataloging the urban scene (103).

Excerpted from FUN HOME: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (p. 27 bottom). Copyright © 2006 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

Fun Home also provides a mirror for the reader’s own engagement and complicity in its acts of self-reflection. Twice, Bechdel uses near-life-sized drawings of a hand holding a sheaf of photographs to call readers’ attentions to our voyeuristic looking at her intimately personal acts of investigating her father’s hidden history and her own identification with it (100, 120). In the last part of this essay I discuss her graphing of spectatorial sites as a mode of metacritical autographics that Whitlock, referencing Scott McCloud, sees as offering readers a particular kind of autobiographical identification (Soft 191) (see Figure 6).

The play with mirroring and illusion is also taken up peritextually. There is a tension in Fun Home between its decorous cover and the graphic disclosures inside, much as a funeral home’s display galleries mask the work done in its back rooms—or how the placid surface of small-town, middle-class, mid-century America hid seething tensions around gender and sexuality in the family. The book is dedicated to Bechdel’s mother (who, she acknowledges, is troubled by its frank revelations) and two younger brothers, with the caption: “We did have a lot of fun in spite of everything.”[11] The hardback’s front cover, an elegant color scheme of teal and silver on black, frames themes of the memoir: a close-up drawing of a tabletop with an embossed silver tray for calling cards at a funeral home (with cut-outs on the tray’s edges revealing the contrasting orange book binding) holds the book’s title like a card, with an endorsement from autographic cartoonist Harvey Pekar (“She’s one of the best”) in small white letters at the top. On the back are other early review endorsements of the memoir, topped by a drawn photo inside an arch of the mother and three young children standing in a frame at the other edge of the table, a kind of funerary photo (which their father is shown taking on the bottom of page 16). The book’s end papers, featuring green-shaded white chrysanthemums on a silvery teal background, imitate the wallpaper in the funeral home.[12] By contrast, the book-binding, in a vivid light orange, is a blowup of the panel depicting each family member inside a black-edged bubble in different parts of the house, in their paradoxically artistic/autistic self-focus (134). Thus Fun Home’s elegant presentation as an artifact invites readers inside its decorous exterior for an encounter with its graphic—in both senses—disclosures about life between the covers.

Fun Home also maps the splits in cultural views and practices that characterized the post-World War II US, torn between the norm of compulsory heterosexuality that had long coded same-sex desire as “inversion,” a clinical term connoting perversion and moral decadence, and a repressed, smoldering consciousness of polymorphous sexuality that erupted in the “gay revolution” of the late sixties and early seventies, with the public protests of Stonewall (1969) and a flood of manifestoes and coming-out stories that comprise a counter-archive of modernist reading in the literary world of Fun Home.[13] This split between generations is marked in the contrast between her father’s closeted homosexuality, with its elaborate denials and displacements, and Alison’s coming-of-age story of discovering her own sexuality, awakened in early childhood by the sight of a “butch” woman and emerging through her experiments with a range of lesbian identity positions. The father’s and daughter’s contrasting stories anchor the narrative transversals through which Bechdel interprets the paradoxes of her family, which the form of an extended graphic memoir, unlike a weekly comic strip, enables her to track in multiple flashbacks and jagged temporalities. As readers, we are asked to trace the complex narrative arc of her coming of age and/as coming out, enacted in reverse by her father’s covert, furtive liaisons and official heterosexuality.[14] Finally, at the memoir’s end the balletic dance of their two narrated stories, in parallels and inversions of each other, sutures their sexual kinship—as a legacy both genealogical and chosen.

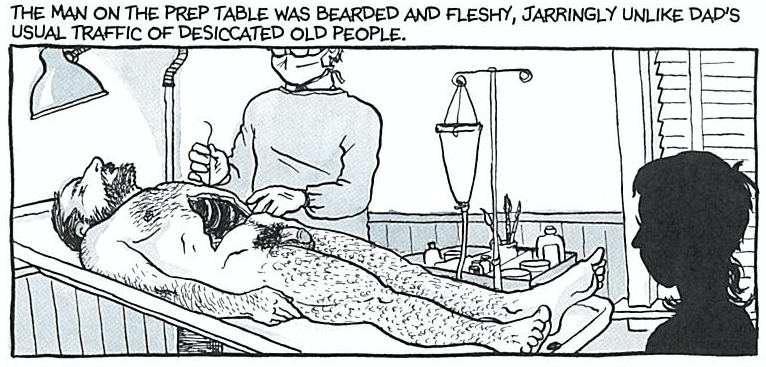

Perhaps the most dazzling visual display of Fun Home is its depiction of bodies, staged in the “theater” of the morgue. Bechdel’s drawings of newly dead bodies in the process of being embalmed or autopsied, in frontal and side views with cutaway sections, are a virtuoso Vesalian display (Figure 3). In counterpoint to the focus on bodies in rigor mortis are the drawings of erotic bodies in action, in scenes of her father’s and her own sexual encounters. This begins with the originary scene of sexuality in Chapter 1, drawn from vertiginous angles, of a young Alison playing “airplane” hoisted aloft on her father’s legs and hands—what she punningly refers to, in a circus term, as their acrobatic “Icarian games” (3). As their bodies mirror each other, the erotics of the father-daughter relationship are visually suggested, as well as the reverse of the Icarus-Daedalus myth, because it is Alison who will fly on the wings of homosexual desire that her father never trusted (3–4). The depiction of bodily erotics extends to graphic sexual depictions of herself—and, in drawn photographs, possibly her father—with lovers, as I will discuss. Fun Home’s interplay between the erotic and the necrotic generates meanings as incarnate—in bodies of desire, some positioned as “porn bodies” (viz. 214); bodies performing gender in costume or drag; bodies in the stillness of a photo or diagram, or the rigor mortis of death; and, not least, bodies connected to our own as we touch and turn the pages.

Excerpted from FUN HOME: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (p. 44 top). Copyright © 2006 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

In sum, Bechdel’s linkage of autographic modes and graphic disclosures creates a richly embodied subjectivity different, in its sustained semiotic cross-referencing, from the narrative consecutiveness of verbal autobiography. Like other autographic narrators (Spiegelman, Satrapi), Bechdel brilliantly deploys a wealth of autobiographical genres juxtaposed as alternative life possibilities. But the use of such templates also poses questions about life narrative in this autographic moment. How is the story of coming of age linked to or rewritten in the coming-out story (as a discovery of what was always already inherent)? How does the solitary story of the artist’s growth intersect with or disrupt the family’s domestic ethnography of reproducing itself? How is the melancholic process of dying and death reworked in its literary afterlife by acts of narrative reconstruction (in Bechdel, reworking the trauma of a tragic death as a literarily comic “happy ending”)? How does the autobiographical meta-story, reading the experience of a youthful self against the family’s official and unofficial or repressed stories, alter or improvise upon—as a chiasmic “network of transversals” or at times a kind of jazz riff—the novel-driven model of literary Modernism celebrated in the canon of Proust, Joyce, James, Wilde, Fitzgerald, Camus, and Colette’s memoirs, all intertexts in Fun Home? And how is each autobiographical template changed by its translation into the vocabulary of cartooning? While I don’t propose answers to these questions, they seem, to me, to signal the potential of this autographic moment in life narrative studies, and to invite new theorizing of subjectivity, genre, and readers’ engagement with the autobiographical.

Reading between the (Ink) Lines in Fun Home

In its histories, both personal and political, visual and narrative, Fun Home offers an archival mine for new kinds of autographical readings. Jared Gardner productively explores the relationship of Fun Home to “autography,” particularly in its relationship to the visual vocabulary of self-reference developed in cartooning practices since 1972 (Biography passim). Narrative theorists such as David Herman also consider Bechdel’s use of visual tags or labels in the frame to mark different temporalities of experience for the narrating “I.”[15] For feminist autobiography critics such as myself, Bechdel creates a richly complex storytelling world, grounded both in the everyday experience of mid-twentieth-century American small-town family life and in the feminist practice of making the personal political through hybrid forms of personal criticism.[16]

In the rest of this essay, I think about autographical practice as a visual and comparative act: by contrasting Bechdel’s drawings of photographs (no actual photos are reproduced) as archival documents with the cartooned story of a remembered—and fantasized—past, we can observe how Bechdel reinterprets the authority that photos as “official histories” seem to hold, and opens them to subjective reinterpretation. In her focus on varying visual versions of her father and her wildly changing impressions of him (recorded in her diary) at different moments, Bechdel composes a textured autobiographical reflection that moves by an ongoing process of her own recursive reading. In these examples we also see Bechdel’s contrast of Second-Wave feminist concepts of gendered subjectivity and sexuality (1970s) through which the teenaged Alison interprets her own experience (at times satirizing the movement’s tendency to jargon-laced, dogmatic pronouncements), to a view, both performative and genealogical, that she constructs as an alternative way of reading her own sexuality in relation to—and against—her father’s.

I focus on a few points in Fun Home—its middle, end, and beginning—to think about how its temporal sequence is punctuated by introspective acts that cast back into the past in spirals of reflection; thus the tendency of the page to impel us forward in reading the comic as a narrative sequence is repeatedly disrupted, spatialized. This itinerary for reading Fun Home may seem perverse, moving from the center of the book to its last page, which I take as an originary point that—in recursive fashion—returns us to a different reading of the drawn photograph with which the book’s first chapter begins.[17] But in this narrative so concerned with transversals, the movement toward reversing characters’ positions as a story develops, and inversions, the traditional term coding homosexuals as inverts of normative heterosexual identity, we are asked to read via this to-and-fro movement. Its arc traces the links Bechdel makes between Alison’s narrative present and the memories of childhood that intrude, and the family’s repressive past and her own liberatory future. We follow how her narrative sets up the possibility of both closure—on the traumatic past of her father’s death, probably a suicide—and opening to her own adult life.

Who’s Looking? Discursive Intersections at the Centerfold

In Fun Home drawings of photographs (no actual photo reproductions are used) play a central role. Photos from her family’s past (some hidden from the children) serve not only as evocations of memory but as evidence of the material reality of what Bechdel investigates as her father’s double life. But her work depends on photographs in a second, uniquely contemporary way. As she described to Hillary Chute, Bechdel created a reference photograph with her digital camera for each pose (there are nearly 1,000) in each panel of Fun Home, photographing herself as the actor for each subject (parent, child, etc.). Her acts of impersonation give a new resonance to the autographical, as she has in a sense literally “tried on” all of the subject positions she depicts—sometimes wryly, as when she notes on a promotional DVD that she had to pose for each parent when they had a fight (Chute, “Gothic” 3). We cannot know to what extent she also literally “inhabited,” as a model, the realistically drawn photographs that figure importantly in her chapter heads, or the photos I discuss that document “secret” intimacies. But her practice suggests ways in which she empathically—and quite literally—could imagine the positions of her characters. And while using drawn photos would seem to guarantee the separate existence of others, Bechdel’s technique unsettles that boundary. In a narrative interested in the permeability of categories of gender and sexuality, the potential for slipping into “all the poses” in acts of autographical identification is provocative.

Fun Home incorporates photographs in several ways: as the chapter head image for each chapter, and at key moments throughout the narrative, where the act of rereading them—some only discovered after her father’s death—is the impetus to her own acts of recognition and autobiographical identification with her father’s desire embedded in a complicated history of overt heterosexuality and closeted transgression with young boys. The chapter head photos are done in a meticulously drawn realistic style, with much shading and cross-hatching, that differs from her cartooning style. In using photos to frame its chapters, Fun Home is allied to the family album, but also marks a distance from its function as official history by reading photos for their transgressive content. At strategic moments, photos also offer Alison occasions for introspection, as she rereads her past to discover untold family stories. And our spectatorial complicity links us, as viewer-readers, with these acts of looking that raise questions about the nature of visual evidence and the possibility of viewers’ empathic recognition.

Chapter 4, “In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower,” the middle of Fun Home’s seven chapters, is a key one for thinking about this interplay of family histories.[18] It narrates moments that link Alison’s teenaged declaration of her lesbian sexuality with “secret”—at least to his family—moments from her father’s young adulthood that she discovers only after his death in a box of photographs. And it offers, via linking their stories of transgressive sexual desire to Proust’s novels, a framework for reading the narrative not as linear but as a recursively spiraling story along a “network of transversals.” Referencing Proust’s model of convergence as a structure for producing reader recognition of the desires that bond characters in seemingly oppositional social positions, Bechdel parallels their two lives as a gay father and daughter. Wittily she observes that they are linked not only as sexual “inverts,” in the derogatory psychoanalytic term of the early century that Proust used (97), but also as inverted versions of each other in the family. That is, she presents Alison’s rejection of femininity as a compensation for her father’s lack of manliness, and his insistence on her dressing and acting “feminine” as a projection of his own desire to perform femininity (98).

This and subsequent chapters depict Alison’s own adolescent coming of age as always a coming-out story, and provide a context for imagining the story her father did not, could not, tell his family, and that, she suggests, fueled his artistic obsession with order and design, as well as his authoritarian parenting. Recalling the several young men who floated through the family’s life, culled from her father’s high-school classes and cultivated “like orchids” (95) for future plucking, Alison recognizes an ideal of masculinity she herself aspires to. Called “Butch” by her cousins for her tomboy prowess (96), the young Alison—Al, she would prefer—is critical of her father as a “sissy,” a version of the identity he attempts to enforce on her (90). Bechdel thus rereads the surface memoir of her childhood as an analysis of how gender binaries are sustained within the family. Her father’s imposing of conventional feminine norms of dress and behavior in the effort to “make a girl of her” conceals his own story of discovering the feminine within himself and rejecting the masculine within her. The adult narrator thus frames the negotiations by which, within the constraints of the family, father and daughter displaced onto each other versions of conventional femininity and masculinity as a way of enacting their refusal of conventional heteronormative gender roles. In this version of the coming-out story, there is no simple narrative of rebellion against parental strictures by transgressive performance; rather, she and her father are linked in both a contest of wills and a deep affinity of desires.

The core of Bechdel’s coming-of-age/coming-out story occurs in her recognition that she and her father could meet only at a phantom middle, a “slender demilitarized zone,” in the appreciation of the pubescent male body as an epitome of androgynous beauty (99). At this evanescent point the family legacy of desire materializes across generations and genders. A double-page literal centerfold at the middle of the chapter, and the book, stages this insight (100–101). It shows a large drawing of a photo recovered from Bruce’s secret stash of photos, dated “AUG 69" (the year blotted out), of their babysitter Roy that her father took in a hotel room he had arranged for when the boy was traveling with them on vacation without their mother (Alison the eldest was 8).[19] The photo of Roy’s body as a vulnerable, yet cheesecake, spectacle is held in the twice-life-sized fingers of a left hand; it reminds us of our complicity as viewers in this intimate glimpse, as our hand holding the book overlaps hers. In the photo a single young male body lies asleep on a bed with two pillows, his tousled head held between his upthrown arms, his torso, clad only in briefs, inclined toward the viewer (Figure 4). The drawn photo is surrounded by elongated dialogue tags that chronicle Bechdel’s conflicted responses, acknowledging both her identification with her father’s erotic desire for the aesthetic perfection of the boy’s body, and her distanced critique as a sleuth of this evidence of his secret life.

Excerpted from FUN HOME: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (p. 100–101). Copyright © 2006 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

These multiple responses are filtered through several autobiographical discourses: the memory of the occasion and their motel rooms by the Jersey shore; aesthetic appreciation for the “ethereal, painterly” quality of light with which Roy is “gilded” in the photograph (100); self-recrimination that she’s not “properly outraged” at her father’s pederastic desire; acknowledgement of her complicity in his “illicit awe” of the near-naked boy’s beauty (101); detached assessment of her father’s characteristic attempt to censor his possible sexual transgression by masking when the shot was taken; and recognition that her father’s management of the contradictions of his public and private lives made him a magician in managing his double life (101). Thus she acts as a kind of detective, hunting the evidence of her father’s secret life that was hidden in their everyday interactions, and rereading family photographs for evidence of his covert homosexuality. The apparent contradictions of his and her mother’s apparently dutiful lives, like those of Swann and the Guermantes, begin to converge as Bechdel reimagines her father’s life as a separate subject, rather than a relative, before she was born, imputing to him an intriguing gay subjectivity that she does not extend to her mother (102).

Telling the story of his repressed desire and associating it with her own coming out in 1980 and early experiences as a lesbian subjected to social humiliations, she bridges their generational divide and different lifestyles by asking herself, “Would I have had the guts to be one of those Eisenhower-era bitches? Or would I have married and sought succor from my high school students?” (108). This act of cross-generational empathy contextualizes her own coming of age in “a precocious feat of Proustian transposition” (113). Like life in the shadows à la Proust, the confusion occasioned by Alison’s adolescent sexuality which impeded her desire to grow up as a boy, and her active disidentification as a child with the eroticized female body of “girlie” calendars (112), as well as the challenge of a big “phallic” snake the children encountered on a camping trip and were unable to kill (114–15), rewrite the conventional coming-out story. Not willing to appropriate either stereotypic position of normative gendered identity, Bechdel’s fable argues for undoing gender binaries, seeing the serpent as a “vexingly ambiguous archetype” (116).

In its place, the narrative proposes a more fluid understanding of identification and desire, in which seeming oppositions are revealed to have always been convergent. In refusing a conventional coming out narrative of rebellion against strict paternal authority that opts for a pre-Oedipal fusion with the maternal, Bechdel bonds with her father’s desire and revises her childhood yearning for erotic connection into a recognition of how she is like him.[20] That is, her story of coming to consciousness rewrites the feminist narrative of maternal bonding as a desire for fusion (for her the mother remains a shadowy figure), and ventures into the deep water of identification and desire across what become arbitrary boundaries of gender.

Bechdel’s story about the meaning of Alison’s childhood memories not only links her sense of her own sexuality to her father’s secret gay side, it also produces a recognition about how their lives are linked over generations: “You could say that my father’s end was my beginning. Or more precisely, that the end of his lie coincided with the beginning of my truth” (117). In depicting, through visual details of her father’s dress, hair, gestures, and notebooks—as well as the series of young men in the house—the coming-out story that he, historically and temperamentally, was unable to tell, Bechdel interweaves his narrative with her own search for a partner, linking their desires. The story thus retrospectively offers Bruce an identity alternative to the one he has lived, based in rigid repression and fear of being branded as perverse and criminal (he is arrested for buying beer for a 13-year-old boy [161]). And Bechdel supplements the post-mortem coming-out narrative she authors for her father with an endearing origin story of her own sexuality, which tellingly occurs in a moment with her father.

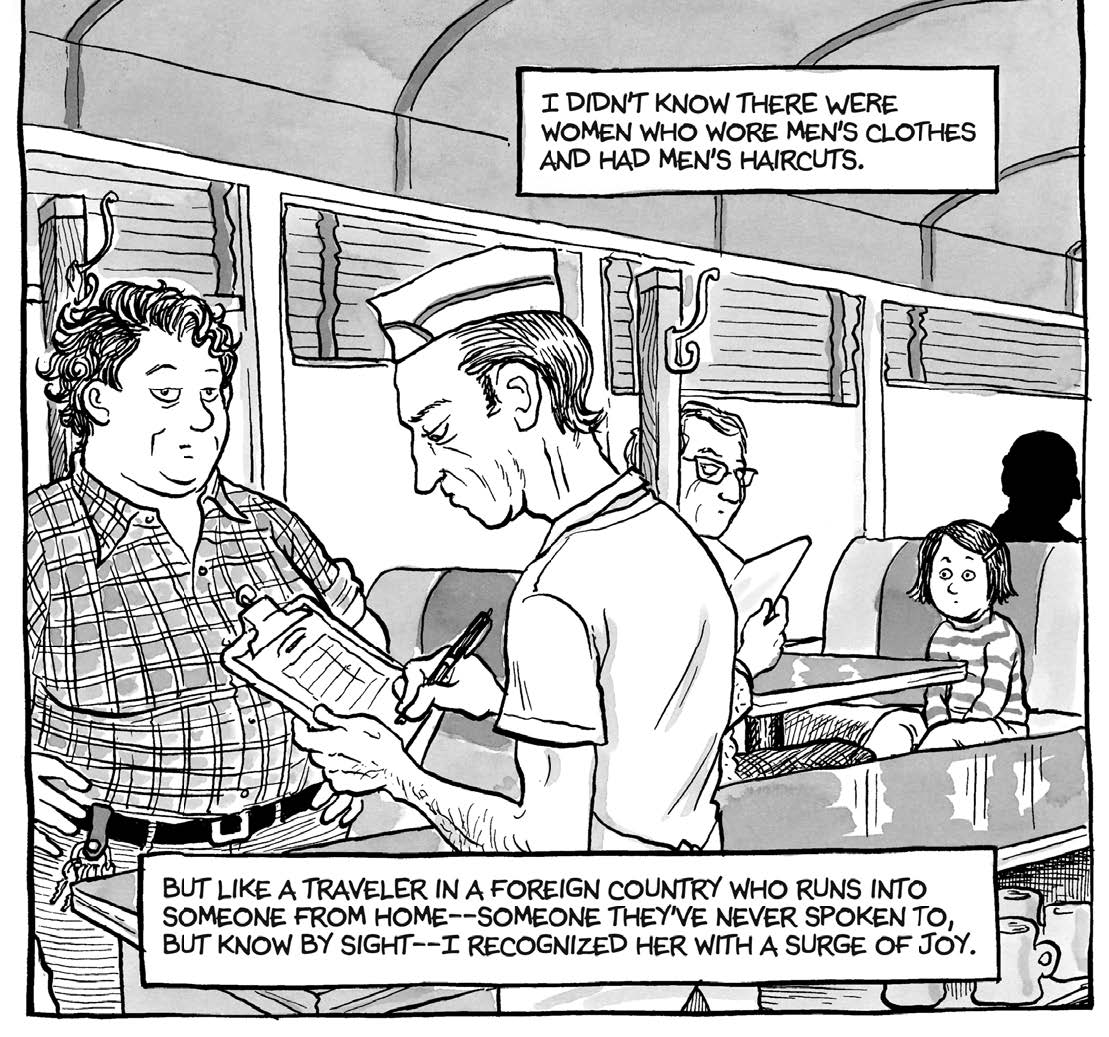

In retrospect, Bechdel recalls that Alison’s pivotal childhood moment of recognizing her lesbian identity occurred early, when she was about four or five. Lunching with her father at a truck-stop restaurant while he is on a business trip, she spots a “truck-driving bulldyke” with close-cropped hair in a checked flannel shirt (119, Figure 5). Recalling, “I recognized her with a surge of joy,” the young Alison contrasts her own identification, presented as innate and “hard-wired,” with her father’s ongoing disapproval of her rejection of femininity (118). Her desire to recast her gender assignment is balanced by his discomfiture with the public exhibit of what he perceives as transgressive sexuality, and repeated throughout the chapter in cartoons that contrast his fastidiously dressed and combed presence with her rakish tomboy looks.

Excerpted from FUN HOME: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (p. 118). Copyright © 2006 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

And yet, the chapter concludes, for all their tensions over her childhood refusal to conform to the stereotypic femininity required by her father’s need to mask his own closeted homosexual desire and to preserve a public image of respectability, telling their story and juxtaposing cartoons of his feminized presence and her boyish recasting of it shows, in repeated near-mirror images, their genealogical and psychological bond. In Alison’s refusal of compulsory heterosexuality as both a coming-of-age and coming-out story, Bechdel daringly rewrites features of that narrative to insist on her cross-gender identification with the repressed desire that underlay her father’s overt heterosexual conformity.

Strikingly, late in Chapter 7, appropriately titled “The Antihero’s Journey,” there is a scene in which father and daughter attempt to reveal their coming-out stories to each other. The moment occurs after Alison has sent her parents her coming-out letter when she is back from college for the summer, and shortly before Bruce’s death. The two-page sequence is the only time that Bechdel uses the square box-style of the traditional comic book, and she employs it for a tightly framed sequence of headshots depicting the dialogue between Alison and Bruce as they drive to see a movie (which she ironically refers to in Joycean terms as their “Ithaca” moment of shared aesthetic sensitivity [222]). The tightly framed two-shots of their profiles dramatize a moment of intimate disclosure. When Alison attempts to broach the subject of sexuality by noting that it was her father who gave her Colette’s Earthly Paradise (a compilation of her autobiographical writings) to read at 14—with its passages of lesbian pleasure—he interrupts and begins to tell her his own story of adolescent homosexual experience and his childhood desire to dress up as a girl, which she remarks paralleled her desire to dress as a boy. While the exchange of disclosures is brief and hardly celebratory (Ulysses, not the Odyssey, she notes wryly), it is as close as they come to a moment of shared coming-out stories. Might we see the graphic mode of three-box panels, four per page, as a kind of visual match for two central aspects of the lesbian coming-out story?[21] The focus on tight-framed intimate exchange parallels what Biddy Martin has defined as its parameters: the specific and intimate disclosure of originary experience to a sympathetic listener; and the circulation and publication of coming-out stories in activist magazines and journals (88–90). With its alternation of their “then-time” dialogue bubbles on white, and Bechdel’s retrospective reflection in white type on a black background, the two pages on “our shared predilection” bracket a kind of breakthrough moment in sexual disclosure shared intergenerationally between father and daughter (rather than the more usual exchange with the same-sex parent) (222). In marking their homosexual bond, however tentative and brief it is, by creating a graphic analogue to the coming-out story, Bechdel enacts a complex homage that links Colette, Joyce, and lesbian coming-out stories while rewriting the analysis of how that desire is understood.

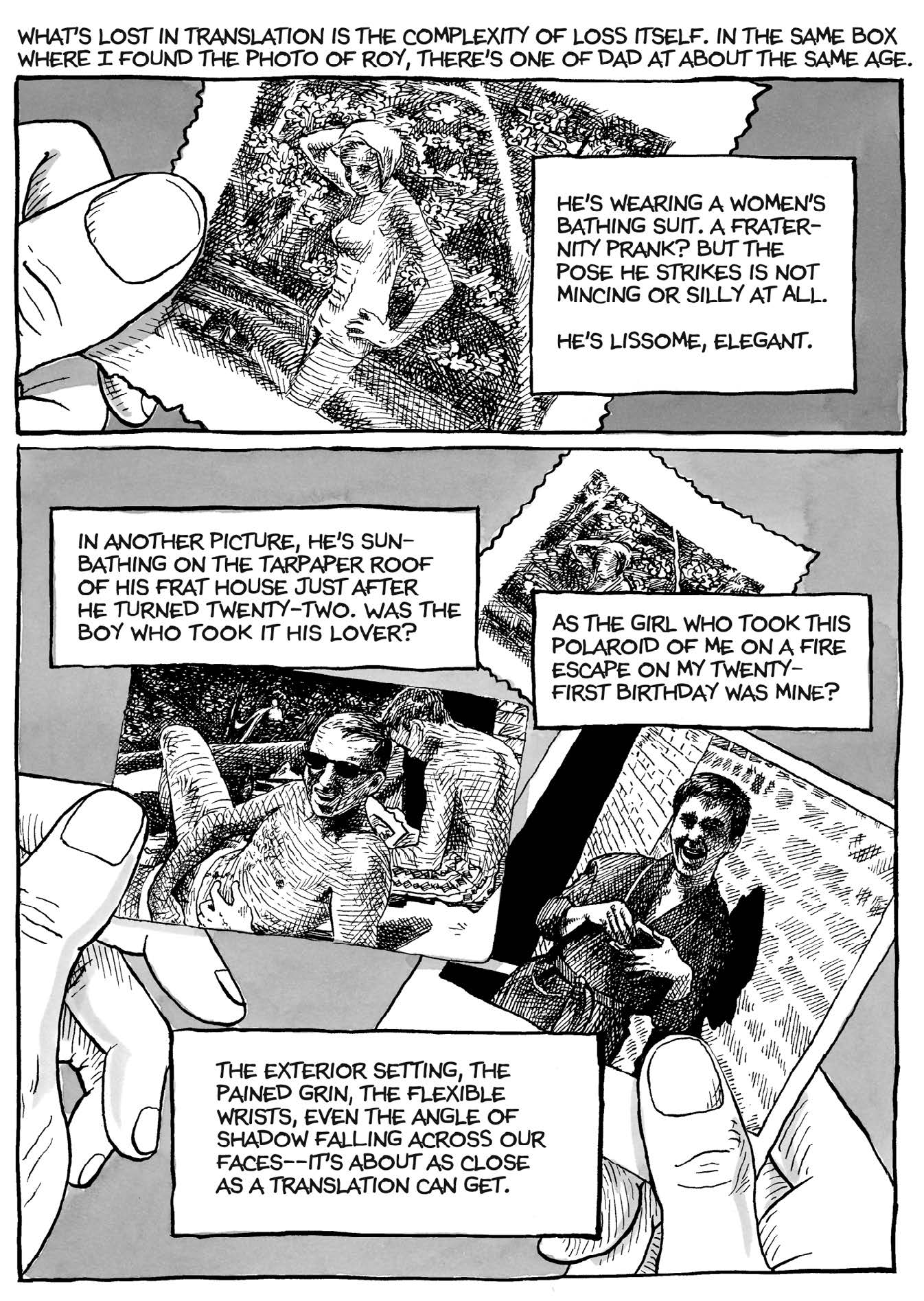

Photographic “Translation” and Graphic Intimacies

Bechdel’s autographic act of drawing—and reading—family photos, her father’s and her own, frames her autographic story as a quest to situate her own desire in a familial line that both “outs” and reclaims her father. Enacting a kind of Freudian “Nachträglichkeit”—recognition achieved in reflection after a traumatic event through reworking the story—Bechdel concludes Alison’s coming-of-age chapter, “In the Shadow of Young Girls in Flower,” with a meditation on photographic evidence that suggests how her autographic narration is rooted in acts of looking and seeing differently. On its last page (120), the story of coming of age as coming out is broken off as Alison reflects, in a meta-narrative, on “what’s lost in translation,” by constructing an autographic dialogic of recognition and melancholic loss focused on a set of photos (120). Here, as with the centerfold at the chapter’s middle, Bechdel presents a set of three drawn photos (one repeated) (Figure 6). The juxtaposed photos of her own and her father’s bodies, his recovered from a box retrieved after his death, show each of them posing before a sympathetic photographer who may be the subject’s lover. Each is cradled in one of Alison’s near life-sized drawn hands, again implicating us as viewer-voyeurs of her intimate disclosure. These photos expunged from the family album become an occasion for probing the complex meanings of genealogical attachment as both transmission across generations and melancholy loss of primary relationship.

Excerpted from FUN HOME: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (p. 120). Copyright © 2006 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

The drawn photo in the top frame, from her father’s college days, depicts him in a woman’s bathing suit as a convincing spectacle of femininity in drag. However much the occasion may have been a prank, his impersonation strikes Bechdel as “lissome, elegant,” a persuasive act of gender-crossing (120). In the bottom panel, that photograph is behind two others held in her hands. The left is another drawn photo from her father’s college days. Sunbathing in sunglasses, open-mouthed and limp-wristed in relaxation, he leans toward the camera, his bare chest and splayed legs a seeming gesture of invitation to the invisible photographer, whom the narrator speculates may have been his lover. The bottom drawn photo on the right shows Alison at the same age on a fire escape with a similar open-mouthed look and relaxed-wrist gesture, in a bathrobe that both “masculinizes” and covers the naked body beneath. She is also inclining toward the photographer, who was indeed her lover. The father-daughter affinity is reflected not only in their shared features, but in their parallel acts of cross-dressing against conventional norms of sexuality. Of these parallel “invitational” photos of father and daughter, the narrator observes: “It’s about as close as a translation can get” (120).

Several things are striking here. First, to the casual viewer the resemblance of the two subjects may seem merely familial, but by “inhabiting” the photos through imagining her father’s cross-dressing (with his gestures as well as bathing suit) and recalling her own body, Alison insists on the meaning of genealogical connection as a transmission of sexuality and desire in a way that both exceeds and precedes gender-specific binaries of “masculine” and “feminine.” As visual evidence, the photos make the case for their shared same-sex orientation, and “prove” that he was fundamentally gay, despite his adult parental life, counteracting his official heterosexual identity and complicating his motives for committing suicide. But in this photo-documentation of the coming-out script that her father refused to tell, we also observe Bechdel’s “interested” act of looking at a resemblance that viewers may find less evident. Calling this genealogical mapping of bodies and desires a “translation,” a vocabulary of words for a visual act, also recalls Bechdel’s invocation of Proust as evidence in support of her father’s gay legacy. Her situating of him as a Modernist artist-intellectual with whom she can empathically identify, despite their troubled history, creates a narrative afterlife that reclaims and memorializes him, while embedding a position for herself in the family story as both its creator and artistic flowering.

Artificer Paradises

The photo on the chapter-head for the first chapter of Fun Home, “Old Father, Old Artificer,” is another drawing from a photo of a much younger Bruce Bechdel (Figure 7). Although there is no explanatory comment for the chapter-head photos, they invite our close looking. Here the title phrase is taken from Stephen Dedalus’s entry at the end of Joyce’s Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man, an autobiographical novel of coming to artistic consciousness that plays throughout the memoir.[22] Although the photo may not initially register on readers, after thinking about the stakes of photographic evidence in Chapter 4, we may return to look at Bruce with a new understanding of his vulnerable, bare-chested upper torso, heavy-lidded eyes, and tousled hair (all of which recall the photo of Roy) as he stands before the family house. This choice of an actual photo of her father, showing an erotic rather than conventionally dutiful parental image, has an almost androgynous uncanniness.[23] Although Bechdel would not have had to pose for this drawing, the thin body resembles drawings of Alison, so that it is possible for viewers to map her body onto his. We begin to see autographically how the daughter-narrator imaginatively inhabits her father by a cross-generational act of identification. Not only does she resemble him, but her drawing traces his photograph and merges his image with her own, in claiming his artistic and sexual legacy. If for Wordsworth the child is father to the man, here the daughter links her identity to performing an act of creative mourning for her dead father. By graphing and authoring the coming-out narrative he could not tell, Bechdel makes her father’s story of private shame, “perversion,” and early violent death into a happier story that enabled her own embrace of sexuality as their shared “erotic truth.” Finally, this photo tells a story not of artificiality but of artifactual making, a memorializing disclosure that moves us in Fun Home’s snake-like recursive tale back to its beginning.

“Spiritual Paternity” at the Graphic Fault Line

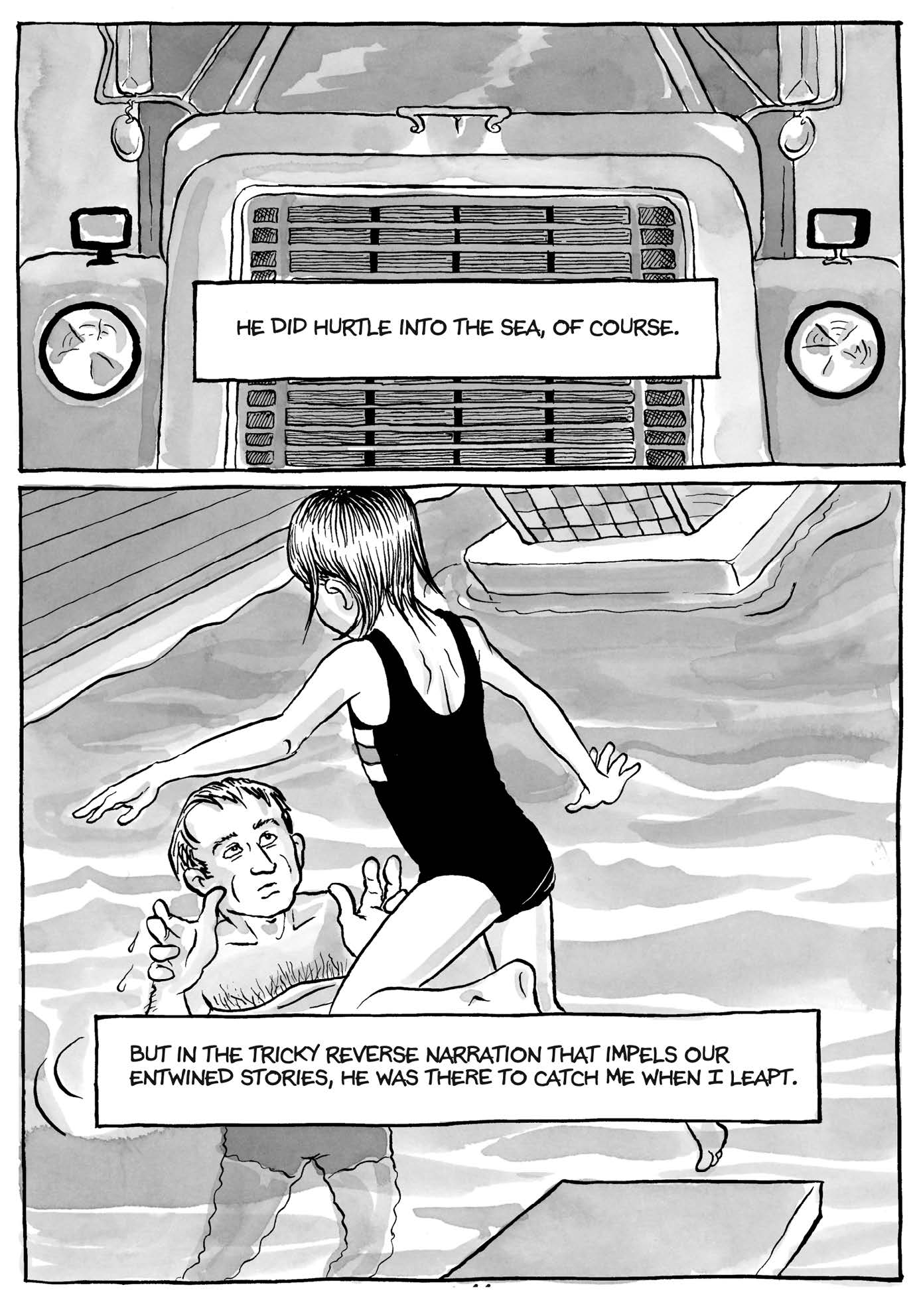

The last page of Fun Home juxtaposes two panels on the page that require readers to situate ourselves imaginatively as viewers and reflect on our spectatorial positions (Figure 8). The top third is a full frontal close-up of a truck (Sunbeam Bread) seen from a low angle. It can only be the point of view of a subject about to be struck, annihilated, a terrifying view of impending death that is anxiety-producing to confront. The dialogue box superimposed across the grill refers to Icarus’s fall, which Bechdel has just mused about, as a “what if” that conjoins her reflection on “spiritual paternity” (231) in Joyce (Ulysses had a better future than his children) and Icarus (if he’d had his father’s inventiveness, could he have survived?) as modes of the antihero whom both her father (in a letter [230]) and Stephen Dedalus proclaim themselves to be. Although I cannot take up the many strands of “erotic truth” that Bechdel here brings into convergence, clearly the frame of the truck inexorably close and head-on suggests a brutal finality to life’s creativity.

Excerpted from FUN HOME: A Family Tragicomic by Alison Bechdel (p. 232). Copyright © 2006 by Alison Bechdel. Reprinted by permission of Houghton Mifflin Harcourt Publishing Company. All rights reserved.

But that graphic is juxtaposed across a narrow gutter without words to the frame below it, double its size, in which the implacable finality of death is reinterpreted. It depicts a young Alison, drawn from behind, on the edge of a diving board, in mid-air over a pool, while her father, arms outstretched, waits to catch her when she jumps. It captures, as well, Alison’s quest to come of age, come out, and come to truth about the mysteries of her father’s life. And the graphic act of imagining the moment of her father’s death, with its question of why he went back into the road after crossing it, is linked for teenaged Alison to her guilt that a letter to her parents announcing her coming out as a lesbian may have motivated the act as a suicide, prodding her to seek closure. Finally, the frame also recalls—and reverses—the Icarus-Daedalus myth, because Bechdel’s retelling of the story of her father’s life, for all its duplicities and shame, as intertwined with her own, enables her to “fly” as an artist and woman.

The conjunction of these opposed “tragic” and “comic” (happy ending) images is startling, and demands that viewers seek some kind of closure to resolve the paradox. Why does Bechdel reserve this set of frames for the memoir’s final page, presented out of chronology from the story of her father’s death (the focus of Chapter 2, “A Happy Death”) and her own developmental narrative? Bechdel’s ending offers readers an autographic perplex in the sense Whitlock has described: “Comics are not a mere hybrid of graphic arts and prose fiction, but a unique interpretation that transcends both, and emerge through the imaginative work of closure that readers are required to make between the panels on the page” (“Autographics” 968–69, referencing McCloud [92]). In this context we may also consider to what extent the moment referenced in the bottom panel is memory or fantasy. Little in the narrative suggests that Bruce, a meticulous, critical father (whom Alison rarely touched and recalls kissing on the arm only once—see 19) was, in her experience, as supportive as the drawing depicts.

Reading autographically suggests a possible closure, and a way to link the “tragic” top frame, in which the viewer graphically confronts a moment of deathly violence, to the bottom frame, in which we are invited to “stand behind” Alison. This final cartoon is a reversal of the camera’s point of view on their positions in the drawn photograph that begins Chapter 7, “The Antihero’s Journey”—the title recalling both Portrait and Ulysses, as well as many other novels referenced in Fun Home. Unlike the photo, it is a close-up, drawn from an angle that places the spectator on the diving board with young Alison, as she hovers before jumping. The drawing thus revisions the chapter’s opening snapshot. In it, Bechdel’s reverse-shot focus emphasizes her father’s face and outstretched hands, perhaps conflating memory and fantasy, to make his paternal act one of tenderness and “spiritual” nurturance (just as the preceding pages, in which Bruce is leading Alison in the pool, depict him as a supportive teacher). And this final frame invites us to imaginatively accompany her leap—into life and sexuality, reversed and interpreted autographically. The frame’s dialogue box about “tricky reverse narration” references the switch of both angles of view and gestural affect from the beginning drawn photo to the final frame of the book. It also captures the larger reversal of positions in which Bechdel meshes Bruce’s history with Alison’s as a transmission of sexual stories that impels her comics and enables her to become the author of their stories. Thus Bechdel’s final cartoon of the family past is a deeply satisfying memorialization of her father’s parental legacy. It suggests that the process of working through her own history, by narratively scripting the coming out that her father could not enact, and refusing to reject him as either “perverted” or failed, rescues him by showing his arms-out gesture of willingness to rescue her.

For Bechdel, as for another autographic self-maker, Charlotte Salomon, the last page of the narrative functions as a kind of signature.[24] This page’s two graphic images can be related only by inhabiting both imagined spectatorial positions, and observing how their reversals complete the recursive circuit that repeatedly disrupts our reading of Fun Home “forward” in historical time. The reader’s transversal of the network of the narrative becomes, if we attend to its autographic connections, an experience of how life is lived forwards but recognized backwards, as autobiographical consciousness.[25] That is, in some sense the autobiographical is inevitably a reworking of lived experience as filtered through memory, fantasy, and reflection across multiple sites of identity and processes of dis/identification. Thus narrative depends in a sense on the death of the past, even as the act of narrating revivifies it for the autobiographer. The narrating I may, in a familiar metaphor, come to voice, to instantiate a “newborn” subjectivity, as Bechdel does in the act of narrating a “dead” past. Such a narrative reminds us of the function of storytelling generally, as a process of retelling life experience of trauma and disappointment until the teller discovers some form of resolution that can both acknowledge pain and provide the closure of a happier ending. The page’s shocking conjunction of a moment of violent finality with one of creative birth situates their interlocked stories graphically across a narrow gutter that is both gap and suture: “His end was my beginning” (117).

Speaking Autographically

In a graphic memoir as densely intertextual as Fun Home, with its letters, diaries, maps, and citations from and readings of twentieth-century novels, how can the difference of the autographical be specified? As Sean Wilsey observed, Bechdel’s writing, unlike that of most cartoon memoirists, is lucid, articulate, and full of “big words,” addressing a new cosmopolitan readership able to move between “high” and “pop” forms. Does that make her text just an illustrated autobiography? If not, what can Fun Home tell us about the distinctiveness of autographics? My discussion suggests that Fun Home is narrated not through the linear chronology of a developmental story, but in a recursive pattern of returns and reversals punctuated by the rhythmic movement of self-questioning and self-commentary.[26] As we have seen, the story ends in its beginning through visual connections between photos and memory images; and it repeatedly casts back—to past events, to genealogical legacy, to classical myths of artistic and erotic creation—to interpret and rework the seeming “truth” of events. In finding an interpretive closure to the two apparently unrelated panels of the last page, Bechdel locates an autobiographical act of connecting experience and interpretation at the nexus of cartoons, pictures, and words. This act of self- and paternal creation through autographical narration is a story of relationship and legacy that depends on graphically embodying and enacting, not just telling, the family story.

How do we theorize this difference of autographics? Cartoonist Ariel Schrag remarked to Hillary Chute that the connection between autobiography and comics “has to do with visualizing memory. Every writer incorporates their past into their work, but that act becomes more specific when you’re drawing” (“Gothic,” my italics). As I have suggested, Bechdel, in the many drawn photos that punctuate Fun Home, probes the interplay between personal memory, a kind of subjectivity imaged in cartoons, and photography, an indexical form of documentary evidence (that is, referring to objects of sight, however misleadingly). And in her readings of photos—through both words and drawings—she undermines the claim of photographs to one kind of tacit authority, and opens them to interpretation that grants them a different kind of encoded subjectivity, a legacy of family history. If the autobiographical is a sustained act of reflecting on and shaping experience to discover and invent the patterned meanings in which subjectivity is inscribed, Bechdel’s drawings of images render the visual world—photographs, objects, places, others, and herself—as a set of memory mirrors that are continuously shaped and refracted by self-engagement. In Fun Home, the signature or autograph of the autobiographical becomes an autographic juxtaposition discoverable in acts of looking, drawing, embodying, and comparing, in an ongoing spiral of reflection.

Discussing the importance of recent graphic memoirs such as Satrapi’s Persepolis and Spiegelman’s In the Shadow of No Towers, Whitlock notes their use of cartoon drawing to interrogate particular images (such as the veil or the World Trade towers) that are discursively fraught and embedded in complex histories, producing dissonance as readers must reflect on the otherness they present as such (“Autographics”; especially 974–77). In thinking about the kinds of closure autographics ask readers to resist, and to make, Whitlock argues, “The unique vocabulary and grammar of comics and cartoon drawing might produce an imaginative and ethical engagement with the proximity of the other” (978). While Fun Home is not primarily engaged with the contemporary global moment, it implicates readers in discerning its possible closure, and in learning to practice a radical critique of sexual politics and aesthetics.

Although I have not discussed how Fun Home extensively parallels the context of Watergate-era Nixonian politics to the climate of repression and “covert operations” in the Bechdel family home (as Jared Gardner’s Biography essay explores), its politics of the personal, a foundational feminist perception, is writ large in two ways: its reframing of homosexuality across the generations and the sexes, and its situating of sexual desire as a struggle to assert bodies and pleasures in the face of an American history of pathologizing them. By interpreting her familial story as a narrative of middle-class American family life filtered through the social persecution of dissident artists in the later twentieth century, Bechdel graphs the personal as a site of struggle for liberation that has analogs in human rights battles being waged around the world, particularly for homosexuals and women. Bechdel uses her “autobiographical avatars” to induce readers to engage with “othering” practices that have habitually subjected homosexuals to dismissal and persecution as either perverse or diseased. Readers engaging with Fun Home’s “tricky” narrative sequence and multiple, disparate modes of self-inscription are brought, by its recursive autographic strategies, to question the social privileging of normative heterosexuality, as we take up its invitation to put ourselves empathically in its intimate picture. Holding Fun Home’s engaging pages in our hands, we may occupy unfamiliar reading positions and be brought to reinterpret initial assumptions, to weigh the apparent authority of archival evidence against the erotic truth of a repertoire of experiences. Its autographics stirs and persuades us to approach human histories and bodies in new and provocative ways, as through the pleasures of humor and cartoons we come to engage affectively and ethically with the complex, overlapping worlds Fun Home presents.

Notes

Author’s Note: for illuminating conversations about Fun Home I am indebted to the expertise and generosity of Jared Gardner, who steered me to this project and offered insights about the comics; Gillian Whitlock for her perceptive and illuminating suggestions; Robyn Warhol, feminist narratologist par excellance; members of the Queer Studies Reading Group at Ohio State University, particularly Anne Langendorfer, Mary Thomas, and Cynthia Burack, who let me join their discussion of Bechdel’s memoir; my Comparative Studies graduate seminar in Winter 2008 for fruitful discussions; and the Billy Ireland Cartoon Library & Museum at The Ohio State University for its resources and sponsorship of the academic conference on cartoons on October 25, 2007, at which I presented a draft of this essay.

1. The comic strips have been collected into several books, appearing every two years, with titles such as Hot, Throbbing Dykes to Watch Out For. The bi-weekly syndicated comic is now posted online at Bechdel’s website and archive.

2. Caren Kaplan characterizes a range of combinatory autobiographical forms as “outlaw genre” practices because they transgress the law of genre and enact hybridized possibilities of narration. Melinda Luisa de Jesús points out that many contemporary ethnic American women’s graphic narratives develop more specific versions of a “hybrid new identity” by using cartoons to emphasize the “striking visual contrast” between mother and daughter in the family, as in Lynda G. Barry’s One Hundred Demons (5).

3. Chute and DeKoven, editors of an important special issue of Modern Fiction Studies on graphic narrative, observe that as a form it does not yet possess a critical apparatus; rather, in its “fundamental syntactical operation [of] the representation of time as space on the page,” it is a hybrid form unlike the novel. They argue that graphic narrative is a multigeneric, mass culture art form in which verbal and visual narratives exist in tension. That is, the images do not simply illustrate the text, but move forward differently than the words with which they are interspersed (769).

4. Second Life is an example of “massively multiplayer online games” (MMORPGs). See the discussion by Tracy Wilson in the howstuffworks.com newsletter (2007) exploring the deep connection between the user and the avatar.

5. Miller trenchantly observes, “The challenge that faces autobiographers is to invent themselves despite the weight of their family history, and autobiographical singularity emerges in negotiations with this legacy” (“Entangled” 543). There is thus a relational aspect to nearly all life narratives. See Smith and Watson 8–13, 37–38.

6. See Michael Renov’s discussion of domestic ethnography as autobiographical practice; it “constructs self-knowledge through recourse to the familial other” by a kind of participant observation that situates subject and practitioner intersubjectively (141–42).

7. Rocio G. Davis notes that “graphic narratives are highly effective künstlerroman [sic]. . . because the subjects of the autobiographical comics are, most often, graphic artists themselves” (269). In Persepolis, the autographic discussed by Davis, however, Satrapi does not focus on Marji’s process of learning to draw as self-expression to the extent that Bechdel does.

8. De Jesús attends to cartoonist Lynda J. Barry’s narrative, “The Aswang,” in which a mythic Filipino vampire-monster becomes a figure for mother-daughter alienation and a way to think about her own choice of cartooning (12). I am indebted to de Jesús’s concise history of developments in women’s comics as part of what Bob Callahan, editor of The New Comics Anthology, called the “New Comics” (see 2–4).

9. Sidonie Smith and I have characterized the autobiographical interface as the space at which diverse media of visual and verbal self-construction intersect in registering the subjectivity of the maker, whether or not a traditional self-portrait is discernable (Watson and Smith 5–7).

10. Jared Gardner sees the “archival turn” (“Archive” 788) as distinctive of contemporary comics, noting that “archives are everywhere in the contemporary graphic novel . . . archives of the forgotten artifacts and ephemera of American popular culture” (“Archive” 787). Part of the pleasure for comic book readers and collectors, he argues, is this visual assemblage of drawn fragments of old comics and ephemera. Bechdel is an archiver of both family memorabilia and the larger history of Second Wave feminist texts, sayings, and styles.

11. In an interview with Hillary Chute, Bechdel acknowledged that her mother, after giving her letters and photos for Fun Home and initially finding the project amusing, changed her view of it: “She felt betrayed—quite justifiably so—that I was using things she’d told me in confidence about my father” (1006). But her mother, a “mixed-message person,” also gave her a further box of letters between the parents (1007). She reiterated her mother’s discomfort with the project at a lecture on October 29, 2007, at the Ninth Festival of Cartoon Art sponsored by the Cartoon Library, The Ohio State University, in Columbus, Ohio. In the Chute interview Bechdel acknowledged the ethical issue her project raised, stating “This memoir is in many ways a huge violation of my family” (1009). While that sense of betrayal may remain for the family, Fun Home also serves as a bequest (to borrow Nancy K. Miller’s term), specifically in memorializing her father after his death by contextualizing his covert pedophiliac acts, and identifying his desire with her own and with a long-repressed and persecuted history of homosexuality in the U.S.

12. Bechdel’s fastidious attention to detail is evident not only in the careful drawing and coloring of the wallpaper, but in the concern she expressed to Hillary Chute that her drawing and coloring did not entirely capture the wallpaper, which she identified as William Morris’s “Chrysanthemums”: “I didn’t get enough contrast in [the wallpaper]. I’ve since learned that there are eleven shades of green in the original—and I was only using five different shades” (1008).

13. For an extensive and erudite discussion of the climate of twentieth-century repression of homosexuality, see Jennifer Terry’s An American Obsession, particularly the chapter on “The United States of Perversion.”

14. Ken Plummer defines the coming-out story as a “Modernist tale” that proliferates in the later twentieth century. Its hallmarks are “a frustrated, thwarted and stigmatized desire for someone of one’s own sex . . . it stumbles around childhood longings and youthful secrets; it interrogates itself, seeking ‘causes’ and ‘histories’ that might bring ‘motives’ and ‘memories’ into focus; it finds a crisis, a turning point, an epiphany; and then it enters a new world—a new identity, born again, metamorphosis, coming out” (52). For a brilliant discussion of genres and examples of American feminist coming-out stories, see Martin. For her, the coming-out story asserts a mimetic relationship between experience and writing, and centers its narrative on the declaration of sexuality as both discovered and always already there. Such narratives are also a quest for a language of feeling and desire that will “name their experience woman-identification” (88). Both Plummer and Martin, in emphasizing the narration of sexual identity, see it as a positional, rather than fully stable, identity.

15. At the “Graphic Narrative Conference” at The Ohio State University on October 25, 2007, narratologist David Herman gave an insightful talk on identity construction in graphic narratives that explored Bechdel’s use of graphic tags as a means of disrupting the Bildungsroman’s linear model of self-narration.

16. Sidonie Smith and I discuss “personal criticism” as an important autobiographical practice of writing the “I” that directs critical attention to the critic’s praxis as a form of feminist pedagogy (see Smith and Watson 32–33, 36–37).

17. Bechdel observed to Chute in the interview that the photographs at the beginning of each chapter “feel particularly mythic to me, [they] carry a lot of meaning” (1009).

18. Bechdel glosses this chapter title as À l’Ombre des Jeunes Filles en Fleurs, a translation of the second volume of Proust’s In Search of Lost Time. And the chapter offers an extended gloss upon Proust’s oeuvre, noting how the apparently opposed paths, literal and metaphoric, of Swann and the Guermantes are revealed to “have always converged” in the course of the novels as a model of how its “vast network of transversals” works to undermine apparent binaries (102). Although Bechdel told Chute “I never actually read all of Proust; I just skimmed and took bits that I needed,” using the novel as a metatext gives her a grid within which to map the apparent opposition and deep connection that she experienced with her father while growing up, and that forms the basis of their homosexual affinity (“Interview” 1005).

19. In the Chute interview, Bechdel asserts that “photographs really generated the book,” discussing in particular this snapshot (1005) and calling it literally “the core of the book, the centerfold” (1006). She further states, “I felt this sort of posthumous bond with my father, like I shared this thing with him, like we were comrades” (1006).

20. On theorizing the matrilineal bond, see especially the work of Carol Gilligan and Nancy Chodorow, and the useful discussion of their studies by Susan Stanford Friedman.

21. My thanks to Sarah Carnahan in a graduate seminar at OSU, Winter 2008, for inquiring about the rationale for Bechdel’s use of this highly conventional style of cartooning for this two-page sequence.

22. “[26 April] Welcome O life! I go to encounter for the millionth time the reality of experience and to forge in the smithy of my soul the uncreated conscience of my race. [27 April] Old father, old artificer, stand me now and ever in good stead” (253). Notably, although the words of the Joycean phrase are the first chapter title in Fun Home, only at the comic’s end do we understand their full implications. Commenting on Bechdel’s extensive use of Joyce’s Ulysses, a book she was required to read in college but remembers resenting, Hillary Chute observes that Alison and her father “figure various Joycean characters,” each occupying the position of Bloom and Stephen at various times; and Bechdel’s observations on Ulysses come just before Fun Home’s final page, in which they also exchange the positions of Icarus and Daedalus in the myth (“Gothic” 4).

23. Bechdel showed this photo of her father Bruce during her talk on the book at the Ninth Festival of Cartoon Art at the Cartoon Library, The Ohio State University, on October 27, 2007.

24. See my discussion of the final painting of Charlotte Salomon’s Life or Theater?, where the title of her work is inscribed across her back, which faces the viewer as the artist gazes out toward the Mediterranean, where she painted in exile. That visual inscription embodies her story in the artistic “I” she created as no verbal narrative could. I argue that “in merging her persona with the artist-autobiographer, making herself through the work, Salomon enacts the creation of [her] ‘name’” (417). Like Bechdel, Salomon narrates a story of becoming the person who could inhabit, tell, and depict the story viewers have just encountered—in 789 non-consecutive pages, in Salomon’s case.

25. Louis Menand’s remark about biography as a form is suggestive: “All biographies are retrospective in the same sense. Though they read chronologically forward, they are composed essentially backward” (66). That is, the events that the subject became renowned for determine what the biographer selects to interpret as formative. A difference of autobiography from biography lies in the nature of the interpreter’s recognition.

26. Hillary Chute also describes Fun Home as “recursive” (“Gothic” 2).

Works Cited

Barry, Lynda G. “The Aswant.” Barry, One Hundred Demons 86–97.———. One Hundred Demons. Seattle: Sasquatch, 2002.

Bechdel, Alison. Fun Home: A Family Tragicomic. Boston: Houghton Mifflin, 2006.

Callahan, Bob, ed. The New Comics Anthology. New York: Colliers, 1991.

Chodorow, Nancy. The Reproduction of Mothering: Psychoanalysis and the Sociology of Gender. Berkeley: University of California Press, 1978.

Chute, Hillary. “Gothic Revival: Old father, old artificer: Tracing the roots of Alison Bechdel’s exhilarating new ‘tragicomic,’ Fun Home.” Village Voice 11 July 2006. 17 Mar. 2008. Online ed. http://www.villagevoice.com/books/0628,chute,73800,10.htm.

———. “An Interview with Alison Bechdel.” Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (Winter 2006): 1004–13.

Chute, Hillary, and Marianne DeKoven. “Introduction: Graphic Narrative.” Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (Winter 2006): 767–82.

Davis, Rocío G. “A Graphic Self. Comics as Autobiography in Marjane Satrapi’s Persepolis.” Prose Studies 27.3 (2005): 264–79.

De Jesús, Melinda Luisa. “Of Monsters and Mothers: Filipina American Identity and Maternal Legacies in Lynda J. Barry’s One Hundred Demons.” Meridians: feminism, race, transnationalism 5.1 (2004): 1–26.

Doucet, Julie. My Most Secret Desire. 1995. Montreal: Drawn and Quarterly, 2004.

Friedman, Susan Stanford. “Women’s Autobiographical Selves: Theory and Practice.” The Private Self. Ed. Shari Benstock. Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1988. 34–62.

Gardner, Jared. “Archives, Collectors, and the New Media Work of Comics.” Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (Winter 2006): 787–806.

———. “Autography’s Biography, 1972–2007.” Biography 31:1 (Winter 2008): 1–26.

Gilligan, Carol. In a Different Voice: Psychological Theory and Women’s Development. Cambridge: Harvard University Press, 1982.

Herman, David. “Multimodal Storytelling: Identity Construction in Graphic Narratives.” Conference paper. Academic conference on “Graphic Narrative.” Blackwell Conference Center. The Ohio State University. Columbus, OH. 25 Oct. 2007.

Joyce, James. A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. 1916. New York: 1964.

Kaplan, Caren. “Resisting Autobiography: Out-Law Genres and Transnational Feminist Subjects.” De/Colonizing the Subject. Ed. Sidonie Smith and Julia Watson. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1992. 115–38.

Martin, Biddy. “Lesbian Identity and Autobiographical Differences.” Life/Lines. Ed. Bella Brodzki and Celeste Schenck. Ithaca: Cornell University Press, 1988. 77–103.

McCloud, Scott. Understanding Comics: The Invisible Art. New York: Harper Perennial, 1994.

Menand, Louis. “Lives of Others.” The New Yorker, 6 Aug. 2007: 64–66.

Miller, Nancy K. Bequest and Betrayal: Memoir of a Parent’s Death. Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2000.

———. “The Entangled Self: Genre Bondage in the Age of the Memoir.” PMLA 122.2 (Mar. 2007): 537–48.

Olney, James. Metaphors of Self: The Meaning of Autobiography. Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1972.

Plummer, Ken. Telling Sexual Stories. London: Routledge, 1995.

Renov, Michael. “Domestic Ethnography and the Construction of the ‘Other’ Self.” Collecting Visible Evidence. Ed. Jane M. Gaines and Renov. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 1999. 140–55.

Satrapi, Marjane. Persepolis. New York: Pantheon, 2003.

Smith, Sidonie, and Julia Watson. “Introduction: Situating Subjectivity in Women’s Autobiographical Practices.” Women, Autobiography, Theory: A Reader. Ed. Smith and Watson. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1998. 3–52.

Terry, Jennifer. An American Obsession: Science, Medicine, and Homosexuality in Modern American Society. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1999.

Watson, Julia. “Charlotte Salomon’s Memory Work in the ‘Postscript’ to Life or Theater?” Signs. Spec. issue on Gender and Memory. 28.1 (Autumn 2002): 409–420.

Watson, Julia, and Sidonie Smith. “Introduction: Mapping Women’s Self-Representation at Visual/Narrative Interfaces.” Interfaces: Women, Autobiography, Image, Performance. Ed. Smith and Watson. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, 2002. 1–46.

Whitlock, “Autographics: The Seeing ‘I’ of the Comics.” Modern Fiction Studies 52.4 (Winter 2006): 965–79.

———. Soft Weapons: Autobiography in Transit. Chicago: University of Chicago, 2007.

Wilsey, Sean. “The Things They Buried.” Review of Fun Home, by Alison Bechdel. The New York Times Book Review, 18 June 2006. 17 Mar. 2008. Online ed. http://www.nytimes.com/2006.06/18/books/reviews/18wilsey.

Wilson, Tracy V. “How MMORPGs Works.” How Stuff Works. 18 Mar. 2008. http://electronics.howstuffworks.com/mmorpg.htm.