Life Writing in the Long Run: A Smith & Watson Autobiography Studies Reader

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

10. Introduction: Mapping Women’s Self-Representation at Visual/Textual Interfaces

From Interfaces: Women, Autobiography, Image, Performance (2002)

Preface

The first section of this Introduction, which discusses Tracey Emin’s installation My Bed (1998) at the Tate Gallery, London, appears separately in this volume as “The Rumpled Bed of Autobiography.”[1] An assemblage of autobiographical memorabilia, Emin’s installation enacted multiple autobiographical performances in both visual and verbal modes that, to us, “suggest that the procrustean bed of autobiographical self-reference is now being performed at an extreme of the avant-garde. [Emin’s] “bed” is simultaneously a site of rumpled, disorderly, stubbornly literal artifacts that insist on their artifactual status as ‘art’” (see Figure 1, p. 92 this volume).[2]

The twentieth century was an exciting moment for the increasingly “rumpled bed” of autobiography studies. In what follows we offer an overview of, and theorize, women’s self-representation as a performative act, never transparent, that constitutes subjectivity in the interplay of memory, experience, identity, embodiment, and agency. We will address two suspicions that have informed traditional histories of art: on the one hand, that women’s autobiographical representation in self-portrait, diary, and performance is “merely personal”; and that, on the other hand, it is “merely narcissistic.” We will consider what is at stake when women remake practices of self-presentation to claim their authority as artists and to contest the history of artistic representations of woman. We will propose a grammar describing four modes of the visual/textual interface: as relational, contextual, spatial, and temporal. Finally, we will gesture toward the larger question of how women artists as makers of their own display are related to the history of woman as an object of speculation and specialization, and the kinds of intervention women artists have deployed to disrupt that specularity. The rumpled bed of autobiographical representation remains a site for productive investigation.

The Ubiquity of the Autobiographical

In visual/textual self-portraiture, the sign of the autobiographical is the identity of the name of the artist (on the painting, on the poster announcing an installation or performance) and the subject of the work. As Lucy Lippard aptly comments, “naming is the active tense of identity, the outward aspect of the self-representation process, acknowledging all the circumstances through which it must elbow its way” (19). During the twentieth- and twenty-first centuries women have named themselves by making art and performance from their own bodies, experiential histories, memories, and personal landscapes in myriad textual and visual modes and in multiple media. These autobiographical acts situate the body in some kind of material surround that functions as a theater of embodied self-representation. At times these materializations of autobiographical subjectivity function as self-portraiture in a traditional mode, such as painted or photographic representations of head and torso. Often, however, the likeness of the artist may be nowhere visible although the imprint of autobiographical subjectivity is registered in matter or light. Sometimes in performance art, voice and body register a heterogeneous or dispersed autobiographical subjectivity. In contemporary self-presentations women have expanded the concept of the self-portrait, once considered the definitive mode of visual autobiography. Modes of self-reference now include visual, textual, voiced, and material imprints of subjectivity, extending the possibilities for women to engage both “woman” and “artist” as “a social and cultural formation in the process of construction” (Nochlin 15) and reconstruction.

If we look beyond the conventions of painted self-portraiture that encode the likeness of the artist, we become aware of the proliferating sites of the autobiographical. In addition to the textual modes of autobiography, memoir, diaries, and journals, there are many visual modes—sculpture, quilting, painting, photography, collage, murals, installations, as well as films, artists’ books, song lyrics, performance art, and websites in cyber-space—that have not yet been recognized as autobiographical acts. Consider the scope of autobiographical presentation in the following media and the artists associated with them (a list by no means exhaustive):

- The painted, drawn, photographic, or sculpted self-portraits of Käthe Kollwitz, Paula Modersohn-Becker, Suzanne Valadon, Claude Cahun, Frida Kahlo, Remedios Varo, Leonora Carrington, Alice Neel, Joan Semmel, Audrey Flack, Jenny Saville, Kiki Smith, Addela Khan, and Elvira Bach

- The artists’ books of Joan Lyons, Susan King, May Stevens, and Kara Walker

- The photographic series of Tina Modotti, Cindy Sherman, Nan Goldin, Jo Spence, Eleanor Antin, Lorna Simpson, Carrie Mae Weems, Renee Cox, and Francesca Woodman

- The painted or collage memorials to family and childhood of Carmen Lomas Garza, Joanne Leonard, Rita Duffy, Aminah Robinson, and Jaune Quick-to See Smith

- The installations of Adrian Piper, Helen Chadwick, Annette Messager, Kiki Smith, Sophie Calle, Mariko Mori, Yong Soon Min, Ann Hamilton, and Nancy Spero

- The billboard interventions of Barbara Kruger, Jenny Holzer, and the Guerrilla Girls

- The performance pieces of Baroness Elsa von Freytag-Loringhoven, Carolee Schneemann, Orlan, Carmelita Tropicana, Laurie Anderson, Diamanda Galas, Annie Sprinkle, Karen Finley, Rachel Rosenthal, Bobby Baker, Blondell Cummings, Joanna Frueh, Coco Fusco, Anna Deavere Smith, and Hannah Wilke

- The sculptural formations of Betye Saar, Alison Saar, Janine Antoni, and Louise Bourgeois and the earthbound projections of Ana Mendieta

- The diaries and daybooks of Unica Zürn, Anne Truitt, and Frida Kahlo

- The feminist cartoons of Lynda Barry, Nicole Hollander, Mónica Palacios, and Erika Lopez

- The material femmages (fabric collage and acrylic painting) of Miriam Schapiro and Judy Chicago

- The murals of Judy Baca and of artists’ collectives in New York, Los Angeles, Chicago, Vancouver, and San Francisco

- The cybersites of Lorie Novak

- The artist autobiographies of Charlotte Salomon, Beatrice Wood, Leonora Carrington, Howardena Pindell, Judy Chicago, and Faith Ringgold

This list—to which readers will assuredly add other names—suggests how intimately women’s artistic production during the twentieth century has engaged the cultural politics of self-representation. And it indicates how frequently women’s artistic production of the autobiographical occurs at the interface of the domains of visuality (image) and textuality (the aural and written word, the extended narrative, the dramatic script).[3] In these heterogeneous self-displays, textuality implicates visuality as, in different ways, the visual image engages components of textuality at material, voiced, and/or virtual sites.[4] Thus, it is essential to expand the concept of autobiography as self-portraiture to include visual, textual, voiced, and material modes of embodied self-representation. These self-referential displays at the visual/textual interface in hybrid or pastiche modes materialize self-inquiry and self-knowledge, not through a mirror for seeing and reproducing the artist’s face and torso but as the artists’ engagement with the history of seeing women’s bodies.

We should point out that women artists have not only mined the visual/textual interface in many media for its autobiographical possibilities but also frequently used repetitive series of self-images to tell a story through sequencing and juxtaposition, as in Kahlo’s, Varo’s, or Kollwitz’s self-portraits, or to perform successive versions of their lives, as in Wilke’s and Orlan’s performances. The fascination of many women artists with serial self-representation, intensified throughout the last century, is abetted by technologies of mechanical reproduction and dispersal and by the opportunity to repeatedly stage performance art on video and film. Thus, what began in the early twentieth century as an experimental engagement with serial self-presentation has become, by now, a frequent and multifaceted exploration of seriality itself, of self-representation in time.

Self-representational acts in all these media—singular, dual, serial, or hybrid—exceed the conventions of painting a head or torso to represent the artist, the traditional conception of self-portraiture. In their diversity and complexity, such acts call for a nuanced theorizing of the autobiographical and of the interface of textual and visual modes that enables self-imaging, auto-inquiry, and cultural critique

Theorizing the Autobiographical

In order to understand the ways in which modernist and contemporary women artists mine the innovative self-representational possibilities of visual and textual interfaces, we engage more systematically with the nature of “the autobiographical.” First, two widely held suspicions about women’s recourse to the autobiographical in visual and performance media need to be addressed—that it is a transparent mirroring and that it is narcissistic self-absorption.

Too often “the autobiographical” in visual and performance media is seen unproblematically as a transparent rendering of the “real” life. In visual self-representation, the autobiographical is assumed to be a mirror, a self-evident content to be “read,” not a cultural practice whose limits, interests, and modes of presentation differ with the historical moment, the conventions invoked, and the medium or media employed. Thus art critics and feminist art historians have often used biographical material to elucidate the autobiographical contexts and practices of women’s visual and performative self-representation in analyzing specific works (paintings, photographs, etc.). That is, they place the emphasis on bios, the biographical life, to “explain” the artist’s history; conversely, the artist’s life history is invoked to elucidate the work. In order to refute this assumption that self-referential works are transparent, we need to engage more systematically with the nature of the autobiographical.

The autobiographical is not a transparent practice. As we have argued elsewhere, “autobiography” is a term with a complex history (Reading Autobiography 1–4). While it has signified multiple practices of self-representation, it has come to be narrowly identified by many critics since the twentieth century with a particular mode of life storytelling, the retrospective narration of “great” public lives. This latter understanding of the term has often obscured the ways in which women, and other people not included in the category of “great men,” have inscribed themselves textually, visually, or performatively. For us, the term “life narrative” better captures the diverse kinds of life stories and practices of telling one’s life that occur in literary genres as different as diary, slave narrative, and collaborative life story, and that inform self-referential practice in much visual and performance art since the twentieth century. While we often use the adjective “autobiographical” to describe women’s self-representation in various visual and performance modes, we prefer to think of the works not as “autobiography” but as enacted life narrative.

As a moving target, a set of shifting self-referential practices, autobiographical narration offers occasions for negotiating the past, reflecting on identity, and critiquing cultural norms and narratives. The life narrator selectively engages aspects of her lived experience through modes of personal “storytelling”—narratively, imagistically, in performance. That is, situated in a specific time and place, the autobiographical subject is in dialogue with her own processes and archives of memory. The past is not a static repository of experience but always engaged from a present moment, itself ever changing. Moreover, the autobiographical subject is also inescapably in dialogue with the culturally marked differences that inflect models of identity and underwrite the formation of autobiographical subjectivity. And she is in dialogue with multiple and disparate addressees or audiences. In effect, autobiographical telling is performative; it enacts the “self” that it claims has given rise to an “I.” And that “I” is neither unified nor stable—it is fragmented, provisional, multiple, in process (Smith and Watson 74).[5]

To theorize the autobiographical we need an adequate critical vocabulary for describing how the components of subjectivity are implicated in self-presentational acts. In earlier explorations of autobiographical narratives, we have defined five constitutive processes of autobiographical subjectivity: memory, experience, identity, embodiment, and agency.[6] These five terms are foundational for an engagement with women’s acts of self-representation in modern and postmodern narratives. In brief, we understand them as follows.

Memory. In the act of remembering, the autobiographical subject actively creates the meaning of the past. Thus, narrated memory is an interpretation of a past that can never be fully recovered. As psychologist Daniel Schachter has suggested, “Memories are records of how we have experienced events, not replicas of the events themselves” (6). He goes on to explore how “we construct our autobiographies from fragments of experience that change over time” (9). That is, we inevitably organize or form fragments of memory into complex constructions that become the stories of our lives. Memory, moreover, has a history: we learn how to remember, what to remember, and the uses of remembering, all of which are specific to our cultural and historical location. And that history is material. We locate memory and specific practices of remembering in our own bodies and in specific objects of our experiential histories.

Experience. “Experience” is the process through which a person becomes a certain kind of subject with certain kinds of identities in the social realm, identities constituted through material, cultural, economic, and interpsychic relations. “It is not individuals who have experience,” Joan W. Scott claims, “but subjects who are constituted through experience” (60). Autobiographical subjects do not predate their experience. In effect, autobiographical subjects know themselves as subjects of particular kinds of experience attached to social statuses and identities.

Identity. Identities materialize within collectivities and out of the culturally marked differences that constitute symbolic interactions within and between collectivities. But social organizations and symbolic interactions are always in flux. Identities, therefore, are discursive, provisional, intersectional, and unfixed.

Embodiment. As a textual surface upon which a person’s life is inscribed, the body is a site of autobiographical knowledge because memory itself is embodied. And life narrative is a site of embodied knowledge because autobiographical narrators are embodied subjects. Subjects narrating their lives, then, are multiply embodied. There is the body as a neurochemical system. There is the anatomical body. There is, as Elisabeth Grosz notes, the “imaginary anatomy,” which “reflects social and familial beliefs about the body more than it does the body’s organic nature” (86). And there is the sociopolitical body, a set of cultural attitudes and codes attached to the public meanings of bodies that underwrites relationships of power.

Agency. If selves and self-knowledge are constituted through discursive practices, then the process through which autobiographical subjects assume agency—that is, control over the representations they produce about themselves—becomes particularly complex. We need to consider how, within such constraints, people are able to change existing narratives and to write back to the cultural stories that have scripted them as particular kinds of subjects. Moreover, we need to consider how narrators negotiate cultural strictures about telling certain kinds of stories, visualizing kinds of embodiment. Recent theorizing on agency is extensive, locating the possibility of change in the autobiographical subject’s oppositional consciousness as it emerges at cultural locations of marginality or in the contradictions of heterogeneous discourses of identity swirling around the autobiographical subject. In one rethinking of agency, political theorist Elizabeth Wingrove conjoins the agency of the subject and the system, arguing, in rereading Althusser, that “agents change, and change their world, by virtue of the systemic operation of multiple ideologies” that “expose both the subject and the system to perpetual reconfiguration” (871).

Given the processes that constitute autobiographical subjectivity, “the autobiographical” as a referent in narrative cannot be taken for granted. Rather, autobiographical acts of narration, situated in historical time and cultural place, deploy discourses of identity to organize acts of remembering that are directed to multiple addressees or readers. Therefore, it is possible for narrators to produce multiple, widely divergent stories from one experiential history, as many literary autobiographers writing “serial lives” have done—Maya Angelou, Lillian Hellman, bell hooks, and Buchi Emecheta, to name a few. Autobiographical narratives, then, do not affirm a “true self” or a coherent and stable identity. They are performative, situated addresses that invite their readers’ collaboration in producing specific meanings for the “life.”

Understanding the components of autobiographical acts enables us to think critically about the practice of reading the life of the artist in—and as—the work, in effect assuming a transparent or “mirror” relationship between the life and the visual and/or verbal text. In Differencing the Canon, feminist art historian Griselda Pollock mounts a critique similar to what we have sketched here for textual life narrative. Pollock contests the tendency of art historians to “index” works of art “directly to experience” and to offer “no problems for interpretation” (97). In the “popular” or “traditional” model of art history, which takes as its subject great artists and their works, she argues, “the artwork is a transparent screen through which you have only to look to see the artist as a psychologically coherent subject originating the meanings the work so perfectly reflects” (98). In effect, traditional models of art history read the work through a constructed biography of the artist as evidence for the biographical life. That is, the artwork becomes a body of mimetic evidence out of which the historian or critic forms a narrative for the artist. In so doing, the historian/critic assumes knowledge of and access to the artist’s “true self.” Pollock criticizes this traditional model for approaching the artwork as a transparent canvas upon which the autobiographical life of the artist is encoded, there to be read unproblematically by the viewer.

Both Pollock’s and our own critiques suggest that in textual and visual regimes autobiographical acts are inescapably material and embodied. They cannot be understood as individualist acts of a sovereign subject, whole and entire unto itself. And the representation produced cannot be taken as a guarantee of a “true self,” authentic, coherent, and fixed. The autobiographical is a performative site of self-referentiality where the psychic formations of subjectivity and culturally coded identities intersect and “interface” one another.

Self-Portraiture and the Question of Narcissism

Understanding autobiographical acts as performative interfaces enables us to address the second suspicion, that the autobiographical is excessively self-absorbed, particularly when women artists take themselves as their own subject. Women artists’ self-portraiture and their repeated acts of self-representation have been alleged to be “narcissistic,” evidence of a merely personal desire to keep looking in the mirror. This charge is rarely made about the serial self-portraiture or the practice of repeated self-portrayal of such male masters of painting as Dürer, Rembrandt, and Van Gogh. Why has the relation of women to the autobiographical been so vexed?

The identification of “woman” with “the autobiographical” calls up a history of reading practices that encode that relationship in specific ways in both literary and art-historical studies. As Domna C. Stanton eloquently argued three decades ago, invoking the descriptor “autobiographical” in literary histories “constituted a positive term when applied to Augustine and Montaigne, Rousseau and Goethe, Henry Adams and Henry Miller, but . . . had negative connotations when imposed on women’s texts” (6). In their gendered reading practices, literary historians ascribed to male autobiographical writers the intellectual and aesthetic command to make their lives richly self-reflexive, to assess the problematic nature of self-knowing and self-telling. In contrast, the “autobiographical,” when applied to women, was “used . . . to affirm that women could not transcend, but only record, the concerns of the private self; thus, it has effectively served to devalue their writing.” “The autobiographical,” Stanton concludes, was “wielded as a weapon to denigrate female texts and exclude them from the canon” (132). If “great” literature achieves canonical status because it “rises” to the level of the “universal,” then the inability of the woman writer—and by extension the woman artist—to rise above “the personal” and achieve a “universal” vision condemns her to an inevitable second-rate status. Effectively, the descriptor “autobiographical” has functioned to exclude women from the cultural category of “writer” and to constitute literature as a masculine domain. From this masculinist perspective, women are considered unable to see beyond their own narrowly self-interested lives; they can only write the personal, the domestic, the private life; and that production cannot speak profound universal truths.[7]

Limiting the woman artist to the domain of the autobiographical—that is, seeing women’s art as “merely” personal—is one way in which “the autobiographical” has signaled that women can only be self-interested, implying their diminished artistic capacities and vision. But since the 1970s, theoretical work within feminist art historical studies has taken this identification of “woman” with “the autobiographical” in productive directions and in different terms than in literary studies. A key concept has been narcissism, which traditional art histories have tended to understand as the self-absorbed identification of the female subject with her own alterity. In the spectatorial gaze of the male artist and constitutively male viewer, woman is defined as there-to-be-seen, all too visible; and yet she remains inscrutable, passive yet threateningly quiescent and untouchable. In this scopic regime, her passivity and remoteness signify her “inability to cathect with an external object” (Silverman 154). But if male representations of woman project her as the self-contented, arrested, and arresting Other, what might it mean for the woman artist to take herself narcissistically as subject?

Since the 1970s, some feminist critics have pointed out how traditional art historians and critics project this script of women’s primary narcissism in reading women artists’ cultural productions and how they fail to interrogate the terms of their essentialist projection of woman as narcissistic. Others, however, have used psychoanalytic theory to argue, quite differently than in literary studies, that narcissism, defined as “the exploration of and fixation on the self” (Jones 46), needs to be revalued. The obvious link between the artist and her body in visual and performance art is material and demands that both internal and external self, and self and other, be connected (Jones 46). The viewer, then, must confront the immediacy of the body or its pieces and debris. Redefining narcissism as a political and performative psychic mechanism for intervening in patriarchal social arrangements, these theorists have recuperated it as an enabling force for feminist projects. Kaja Silverman has done this by arguing that “female narcissism may represent a form of resistance to the positive Oedipus complex, with its inheritance of self-contempt and loathing.” The very condition of femininity is a desire for and identification with the mother as the first love object, a love relocated as self-love, a self-love, according to Silverman, that “presupposes love of the object in whose image one ‘finds’ oneself” (154).

Jo Anna Isaak has also redefined narcissism as enabling. The strategic deployment of narcissism, for Isaak, offers a means of agency to the disenfranchised woman, an agency derived from laughter invading, at least temporarily, the paternal law of woman’s nonexistence. As Isaak suggests, women artists of the autobiographical can explore “the possibility of women’s strategic occupation of narcissism as a site of pleasure and a form of resistance to assigned sexual and social roles” (“In Praise” 54). Similarly, Amelia Jones recuperates narcissism as a strategy adapted by feminist artists in the 1970s to politicize their personal concerns by speaking them publicly, thus proclaiming their status as subjects of culture (Jones 47). Jones observes, “Narcissism, enacted through body art, turns the subject inexorably and paradoxically outward” (48). In late capitalism, she argues, the narcissistic projection of self becomes “a marker of the instability of both self and other” to be positively valued for its dislocation of a mythic transcendent Self (49).

Isaak’s, Silverman’s, and Jones’s invocations of women’s “strategic occupation of narcissism” illuminate one of the defining features of women’s self-representational art practices in the last century. Turning their attention to their own bodies and subjectivities in diverse ways, women artists working in multiple media have used the bits and pieces, the debris and excesses, the constraints and effusions of their own embodiment to materialize self-referential displays. In this strategic self-preoccupation, they have engaged the codes and genres of masculinist self-portraiture and a tradition of modes of representing “woman” as other in art’s histories.

The Stakes of the Autobiographical

Feminist art historians of the last three decades have extensively explored how the tradition of Western artistic practice often presents the female body, nude or clothed, at the center of a painting or sculpture, as situated through the specular gaze of the male artist and patron. It is through this gaze, and the regime of visuality encoded in and encoding that gaze, that “woman” has been figured in her difference.[8] What we would emphasize is that this figuration projects upon woman a subjectivity, an identity, and a life script—that is, a biography of a sort—of a different order from her intimate experience of herself. To paraphrase John Berger, women engaging this represented figure of woman become conscious of “watch[ing] themselves being looked at” (47).[9] Women become conscious of being biographically scripted in disabling ways, disciplined to a constraining script of femininity.

Thus, historically, women have encountered themselves as the objects of art and not as its makers. Those women who became artists before the late twentieth century, as well as many of those now making art, have had to confront the constitutive masculinity of the institutions of cultural production and their own cultural status as objects of the male gaze—that of the artist and that of the patron. To see themselves outside this history of representation requires coming to terms with the “woman” of art and art history as an idealized figure, an object of male desire, and an idealized or debased other to flesh-and-blood women with radically diverse experiential histories. In Peggy Phelan’s terms, they have had to both engage “the ideology of the visible” and expose the blind spot within theoretical framing of who and what is visible or “marked” (7). Doing so, women artists acknowledge their shared status as interlopers in a masculinist tradition, a status derived from “women’s subordination in difference” (Mouffe 382). Acknowledging and negotiating that status, they participate in a paradox—a tradition of persistent rupture.[10] “Positioned to collude in their objectification,” observes Whitney Chadwick, “unable to differentiate their own subjectivity from the condition of being seen, women artists have struggled toward ways of framing the otherness of woman that direct attention to moments of rupture with—or resistance to—cultural constructions of femininity” (9).

Considering the “art of reflection” in women’s self-portraiture, Marsha Meskimmon describes the dilemma for women artists linking self-portraiture and life narration: “There is, on the one hand, a need to show the ‘self,’ to rejoice in being able to come to representation in your own terms rather than as an object in another dominant schema which forces you into the margins. At the same time, there is a recognition that the models used most commonly cannot simply be appropriated without critical adaptation. The final products, therefore, express the multiplicity of identity and concepts of negotiating positions and voices” (95). Paradoxically located between appropriation and adaptation, women artists exercise what Susan Rubin Suleiman describes as a double allegiance to traditions of representation, affirming and critiquing the masculinist traditions they inherit (131).

This examination of the relationship of women artists to the traditions of art history, particularly self-portraiture, suggests that visual/textual interfaces are acute sites for engaging issues of gendered subjectivity and agency in self-representational acts. Contemporary histories of women’s artistic production in the twentieth century often understand the motive for narrating one’s life as politicizing the personal. And they read it as an originating point of, prime motive to, content of, and/or transformative site for women’s self-representation and the problematizing of woman as artist. Many critical tropes or themes inform discussions of the autobiographical in women’s visual/textual work and offer terms tor engaging their artistic production. They include:

- Woman’s objectification, seeing herself as seen in the gaze of the male artist, particularly in the legacy of the “female nude”

- The commodification and fetishization of female beauty and bodies in art and advertising

- Women’s visualized difference and the differencing of women (in ethnicity, race, sexuality, age, class)

- Women artists’ vexed relationship to the canons, conventions, and visual vocabulary of art history as an institution

- Women artists’ ambivalent relationship to the materials of production and their exploration of alternative materials, such as quilts, collages, and the earth

- The project of identifying genealogies and foremothers prior to an articulated tradition of women’s art and issues of essentializing “woman” in that process

- The appropriation, through parody and critique, of the canonical work of the “masters”

- Remappings of identity as fragmented, unstable, alternative, hybrid, and/or collective

- The embodiment of subjectivity and the subject of embodiment

- Censorship and self-censorship

Of course, these recurrent themes can be understood as invocations of feminist issues and debates taking place more generally across humanistic disciplines since the 1970s. But, of more interest to us, they can be approached as localized engagements with the potential, the politics, and the privileges of the “autobiographical” as a mode of self-presentation and self-knowledge in women’s visual and performance art.

Through these localized engagements, women artists have, according to Meskimmon, “challenged simple psychobiography in the form of serial self-portraiture, subverted easy ‘historical’ or ‘biographical’ accuracy, queried the significance of mimesis and revealed the ways in which their ‘selves’ were the products of shifting social constructs and definitions of ‘woman’” (73). They have also, as Helaine Posner observes, situated the quest for self-knowledge in visual terms “somewhere between exposure and disguise.” According to Posner, multiple self-representations both “reveal and conceal” the subject, enacting the tension between assertion and denial of self (158).

Consider an example of localized engagement in the painted self-portrait. In 1980, four years before her death, eighty-year-old Alice Neel completed Self-Portrait, one of her many wryly experimental self-portraits (Figure 1). Recollecting a career that spanned much of the twentieth century, this self-portrait alludes to her conversancy with its major art movements, suggested by the Matisse-like striped chair and the juxtaposition of bold green and orange diagonal planes of color on the lower half of the canvas. Although Neel has recently been commemorated, in a film and an exhibition, as a nurturer of the New York School of male poets and artists, this self-portrait suggests vigorous and audacious reflection on the emergence of women as artist-subjects in their own right.

Alice Neel: Self-Portrait, 1980, oil on canvas. Courtesy of National Portrait Gallery, Smithsonian Institution, and Estate of Alice Neel, 1980.

In her naked Self-Portrait, Neel in one sense paints herself into a corner, leaning forward in a blue-striped chair near the angle where two rear walls of a white room meet. The subject’s fleshy, naked body, framed by a penumbra of bluish shadow from an invisible source of light to her right, is the focus of the painting, her concealed vagina at its center. But in another sense Neel confronts the viewer as a woman artist who has found her way out of that marginalized space on her own terms. Her body, at a three-quarter angle, is neither idealized as a female nude nor made into the mythic crone of Western representations of aged women. Neel’s body, with its sloped shoulders, its pendulous breasts over full belly, and fleshy legs, sags in every muscle except those of her agile right and left hands, one grasping a paint brush, the other a rag; her nimble feet; and her still, alert head. But as she offers her body for inspection, its sag is as much one of ease as of age. This body is not an object for spectatorial consumption. The artist’s face, framed by long gray hair caught up in a knot, looks out at the viewer through top-rimmed glasses with calm, impassive scrutiny, like that of Käthe Kollwitz’s sculpted, drawn, and etched self-portraits of the 1930s. There is an intimacy in this inspection by a calm, intelligent, naked woman. In this compelling and moving self-portrait, Neel’s candid regard of the viewer invites our own self-assessment. As Frances Borzello suggests, “This is a manifesto self-portrait embodying Neel’s belief that nudity brings the viewer closer to the subject” (161). In Self-Portrait, Neel, without either vanity or false modesty, invites the spectator’s gaze as both an aged woman and an accomplished artist, with a body of work and a body at work.

As Neel’s naked Self-Portrait suggests, a woman artist’s self-portrait is often, by the end of the twentieth century, a complex site of negotiation, appropriation, and adaptation. It alludes to both a history of representations of “woman” that are critiqued and a history of artistic self-portraits of assumed masters of painting. Using Matisse’s interiors, colors, and angles, Neel “ruptures” a modernist mode in which a nude woman, as an ideal of beauty, is an object to be viewed and presents herself instead as a creative agent. Her work is autobiographical in its engagement with the changing position of women artists in the twentieth century and with our habit of viewing naked women as nudes for spectatorial consumption and possession, rather than as actors whose work reflects on how art’s histories fixed and immobilized them. Precisely in fusing representation of the female nude and the artist’s self-portrait, Neel’s naked self-portrait, like those of several other twentieth-century women artists, situates autobiographical subjectivity in and as embodiment.[11]

The Visual/Textual and Performative Interface

Philippe Lejeune has written of the self-portrait: “I see the self-portrait as a particular situation, somewhat irregular, in which in the middle of the most coded genre (the portrait) a spark abruptly bursts forth (which is at times only in the mind of the spectator), allowing the essence of the art to be seen in a staggering way: the self-representation of humans (and not the representation of the world), the self-portrait becoming the allegory of art itself” (114). If, indeed, the self-portrait might be read as an allegory of art, then we as viewers can view the sparks of women’s acts of self-representation as they reread, and trope upon, their relationship to art’s histories and to their status as subjects of and in representation.

In the fields of art history and performance studies, many critics, including Griselda Pollock, Whitney Chadwick, Marsha Meskimmon, Peggy Phelan, and Susan Suleiman, as well as Amelia Jones, Jo Anna Isaak, and Linda S. Kautfman, have significantly influenced the ways in which we read and understand women’s visual and performance self-representations. In autobiography studies, Timothy Dow Adams, Linda Haverty Rugg, and Marianne Hirsch are among those who have directed attention to the ways in which the regime of visuality, particularly photography, has come to play an ever larger role in written autobiographical narratives, incorporated as another mode of telling within the text or described and thematized within the narrative. Interfaces seeks to complement this corpus of critical studies of women’s autobiographical practice in visual and performance media by foregrounding the sparks or encounters or interfacings of different media.

The possible relationships between visuality and textuality at the interface have been theorized by scholars exploring the cultural construction of scopic regimes and historical cultures of visual practices. Some have mapped the complex relationships between pictorial and narrative aspects of paintings, as do Svetlana Alpers and Michael Baxandall (Tiepolo and the Pictorial Intelligence), who tease out the “twisted tale” of how Tiepolo’s pictorial representations disrupt pictorial narrative. Other scholars look broadly at regimes of textuality and visuality. In Iconology: Image, Text, Ideology, W. J. T. Mitchell sets textuality up as a foil to visuality in order to explore how visual image and language or text have been defined as oppositional. Rather than accept that opposition as “real,” Mitchell suggests that the opposition is saturated with the history of regimes of representation. At particular historical moments the opposition of image and text (or word) inscribes ideological forces that make certain differences “readable” and significant. Thus, “the dialectic of word and image seems to be a constant in the fabric of signs that a culture weaves around itself” (43). And the usual suspicion of image, as opposed to text, suggests that “every theory of imagery is some form of the fear of imagery” (159). Yet Mitchell’s argument that visual images “are inevitably conventional and contaminated by language” (42) suggests that the relationship of the visual and the textual is intimate, inextricable, and multivalent. Visual modes encode histories of representation and invite viewers to read stories within them. Textual modes make their meanings through imagery and through such figures as ekphrasis. Mitchell helpfully calls not for a facile reconciliation between the imperatives of words and visual images but for historicizing that relationship and its cultural meanings.[12]

Other art critics and theorists have historicized the visual/textual matrix at particular historic conjunctures, as Hal Foster does in his two volumes on practices in the twentieth century. In The Return of the Real, for instance, Foster explores American art from the 1960s to the present, paying particular attention to the “textual turn” that gained ascendancy in the 1970s. In that turn artists experimented with postmodern interrogations of the sign, with proposing the evacuation of meaning of the sign, and with challenging the cultural coding of artistic institutions and settings. In many modes of the visual, the textual turn came to problematize referentiality itself, most centrally in the intimate mingling of the pictorial and the narrative in film, a medium not addressed in Interfaces.[13]

Critics of women’s art have theorized more explicitly the gendered dimension of the visual/textual matrix. Rosalind Krauss, in numerous works and, most recently, Bachelors, considers how the gendered histories of image and text are negotiated by artists who, though women, position themselves as artistic innovators, deconstructing modernist and postmodernist framings of the relation of image and text. French modernist photographer Claude Cahun, Krauss argues, situates herself simultaneously as subject and object of representation, not to make an autobiographical narrative of reclaiming agency for the female subject but to “suspend the fixity of gender” (37). Such art made by women, Krauss concludes, “needs no special pleading” (50) because their disruption of fixed spectatorial positions mobilizes boundaries to create a continuing instability of masculine and feminine identifications, like, but more effectively than, say, Duchamp.

Feminist theorists of performance art have characterized the interplay among embodiment, visuality, and textuality somewhat differently. Many of them have drawn upon Judith Butler’s theorizing of identity formation as performative, a concept that has profoundly influenced debates about performance art. For Butler, gendered identity is always already performative. “Within the inherited discourse of the metaphysics of substance,” she argues, “gender proves to be performative—that is, constituting the identity it is purported to be. . . . There is no gender identity behind the expressions of gender; that identity is performatively constituted by the very ‘expressions’ that are said to be its result” (Gender 24–25). Performance art thus offers occasions for artists to deploy self-imaging, voice, gesture, and text in exposing the gendered features of what Butler calls “the domain of socially instituted norms” (Bodies 182) and interjecting traces of the excluded and abject.

RoseLee Goldberg notes the confrontational aspect of performance work, in painting as in theatrical modes, and emphasizes the viewer’s active role in keeping it “live art.” The fluid status of live art across various divides, not only of word and image but also of high and popular culture, theatrical space and cyberspace, the alternative and the mainstream, suggests how boundaries of visual and performance art have been, and continue to be, redrawn. Itself an unstable term with different connotations in different nations, performance is characteristically provocative, critical, and often unnerving (Goldberg 12–13). Similarly, Peggy Phelan’s concept of the “unmarked” as “a configuration of subjectivity which exceeds, even while informing, both the gaze and language” makes of performance a disruptive mode of exposing difference and disappearance within regimes of cultural reproduction (27). As Amelia Jones argues for body art, the collapse of distinctions between subject and object, self and other, and public and private in performance makes corporeal display a means of “claiming the immanence and intersubjective contingency of all subjects,” an exposure of the subject as both destabilized and irreducibly embodied (51).

The visual/textual interface of feminist performance art since the 1970s, then, has often made public display of personal convictions, interrogating ethnic and racial identities, diverse sexualities, and national affiliations through edgy material that confronts spectators with formerly unspoken notions about “woman,” as discussions of performance artists make clear.

A Model for Reading the Gendered Interface

Given the multiple sites of the autobiographical not only in visual, aural, and textual media but at their intersections, no single-discipline model is sufficient to address the complex interweaving, explicitly or implicitly, of image, word, and voice in twentieth-century women artists’ self-representation. We propose here an interdisciplinary model for interpreting diverse autobiographical practices, projects, and effects generated at visual/textual interfaces. This model draws upon autobiographical theory to discern rhetorics of self-presentation and narrative scripts of identity in women’s visual and performance art. In our reading of particular works, the interface is a site at which visual and textual modes are interwoven but also confront and mutually interrogate each other. The textual component, either explicit or implicit, is configured differently as a “script” than is the visual mode; and these modes must be read against/through each other, in the varied ways detailed later, to elucidate the autobiographical presentation of a subject.

Directing attention to the interfaces of autobiographical acts illuminates how they affect or mobilize meanings: the textual can set in motion certain readings of the image; and the image can then revise, retard, or reactivate that text. In enumerating modes of the interface, we turn to many women artists and performers not elsewhere discussed in this collection of essays. Our brief explorations here may suggest how rich the work of innovative artists and performers is for further investigation by scholars working at the intersection of textual and visual studies.

There are four primary ways in which artists may texture the interface to mobilize visual and textual regimes: (A) relationally, through parallel or interrogatory juxtaposition of word and image; (B) contextually, through documentary or ethnographic juxtaposition of word and image; (C) spatially, through palimpsestic or paratextual juxtaposition of word and image; and (D) temporally, through telescoped or serial juxtaposition of word and image.

A. Relational Interfaces: Parallel, Interrogatory

In relational interfacing the visual and textual are set side by side, with neither subordinated to the other. They may, however, either complement (be parallel to) or interrogate each other. When visual and textual modes run parallel to each other, their different vocabularies overlay different versions of autobiographical subjectivity. As Mitchell suggests of the visual and textual composites in William Blake’s art, “their relationship is more like an energetic rivalry, a dialogue or dialectic between vigorously independent modes of expression” (Blake 4). That is, the visual and textual are not iterations of the same but versions gesturing toward a subjectivity neither can exhaustively articulate; they are in dialogue. In illustrated daybooks and diaries, especially, the visual and textual modes may run along parallel axes as they “record,” through the disparate means of words and images, responses to everyday occasions and fashion identity from the flux of dailiness.

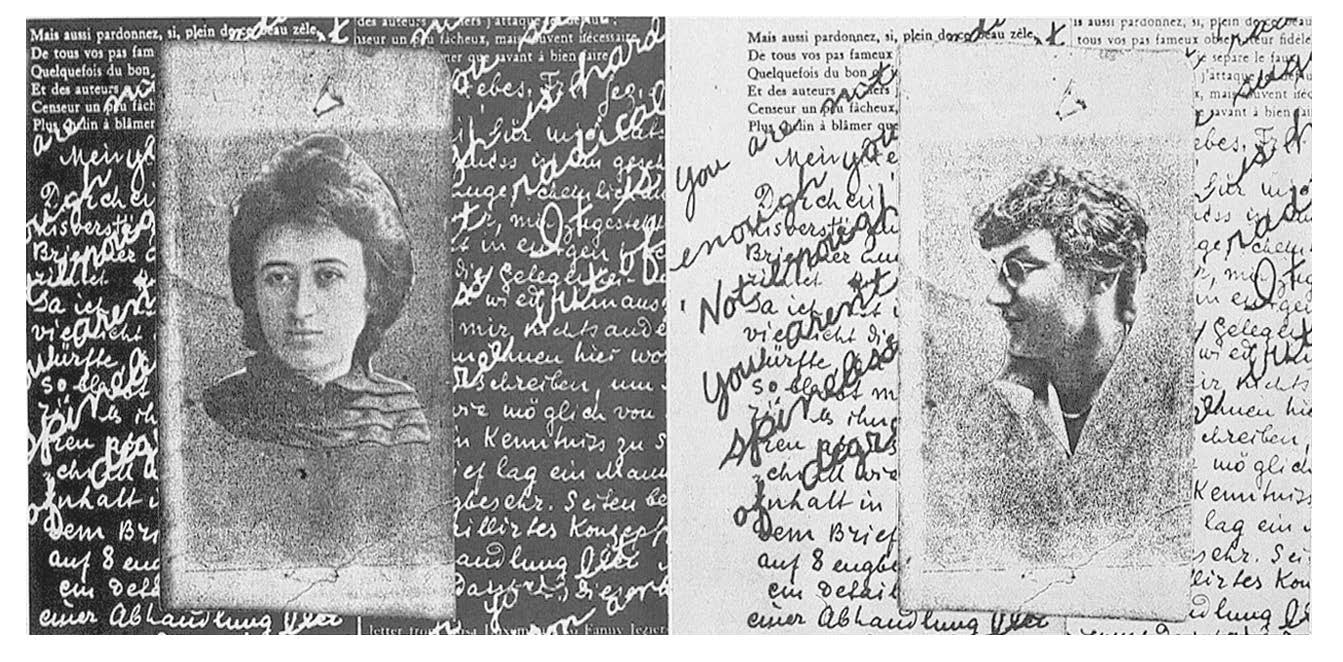

Consider an example of parallel relationality at the interface. In her artist’s book entitled Alice, Rosa: Ordinary Extraordinary, May Stevens juxtaposes photographs of her mother and of German socialist feminist Rosa Luxemburg (Figure 2). On the book’s page, the image of Alice on the left and the image of Rosa on the right are side by side. Placed on two pages, one in white ink on black paper, the other in black ink on white paper, the pages form a mirror opposition. Each has three layerings of citations from Luxemburg and Stevens’s mother, Alice, written in three languages (French, English, German). Here the words at once are commentary, referential signs, and visual image, a “sea of words.”[14] It is a feminist sea, a theoretical sea, as her painting Sea of Words explicitly suggests. Stevens states: “I love a page of text. Pages of text or writing are very, very beautiful” (lecture). The sea of words images how women’s words can become, for the woman artist, an originary point of self-knowledge and artistic practice.

May Stevens: Rosa Luxemburg and Alice Stevens. From Rosa, Alice: Ordinary/Extraordinary, artist’s book, 1988. Courtesy of the artist and RYAN LEE Gallery, New York, New York.

For Stevens, Luxemburg was a major intellectual figure and her mother a relatively uneducated housewife. Paralleling Luxemburg’s extreme of activism to her mother’s private domesticity, Stevens brackets the possibilities of women’s lives in the early twentieth century. For Stevens, both women were simultaneously ordinary and extraordinary. Joining their images and marking their differences with captions, Stevens brings the historical figure of Luxemburg closer and puts distance between herself and her mother. This series is autobiographical in showing Stevens’s relationships to women who have “made” her. By juxtaposing a personal and a historical figure, she uses the interface of their biographies to evoke versions of her own story, which is not explicitly told. As she has indicated, this Rosa is not objectively biographical but is the idea of “Rosa Luxemburg” in her imagination, a construct; her mother, in contrast, is “real,” known to her, but also a subjective presence, saturated by childhood memory. In the artist’s imagination, twining them inextricably together produces their meaning for her life. Even as the particular figures of Alice, her biological mother, and Rosa, an activist foremother, remain distinct, they are parallel. Relating and entwining their histories elicits the artist’s own history.

The visual and textual components of a work may also be interrogatory, standing in a relation of inversion, telling radically different, even contradictory, stories. This is the case in Mary Kelly’s Interim, Part 1: Corpus (1984–89), a visual diary (Figure 3).[15] In Corpus, Kelly presents texts incorporating her own and other middle-aged women’s subjective voices as they negotiate a postmaternal identity no longer representable as idealized “femininity.” This diaristic, confessional writing of women excluded, as woman, from cultural discourse, is juxtaposed to captioned photos of various women’s garments. The photos present the five articles of clothing (in a triptych) as fetishes, substitutes for the women whose bodies they are designed to both shield and reveal.

Mary Kelly: Detail of “Menace” from Interim, Part I: Corpus, 1984-1985. Laminated photo positive, silkscreen, acrylic on Plexiglas 30 panels: 36" H x 48" W x 2" D each. Courtesy of the artist, Susanne Vielmetter Los Angeles Projects, and Mitchell-Innes & Nash, New York.

In Corpus, the visual images of garments that syncopate with women’s voicings of the experience of middle age are labeled with such words as “Menace,” the caption attached to a black leather jacket. These labels mime the labeling of Charcot (the nineteenth-century French doctor and pioneer in the study of hysteria, which he gendered as female), who attached captions to his photographs of hysterical women taken at the Salpêtrière in Paris. Invoking Charcot’s visual catalog of hysterical symptoms and attaching labels to three photographic images of the articles of clothing rather than to an embodied woman, Kelly reorients the viewer to the female body by reinterpreting hysteria through the discursive domains of fashion, medicine, and fiction. Doing so, she appropriates the photographic practices used in the production of female hysteria for her own purpose of calling the diagnosis into question. Kelly disentangles the Charcotian significr from its signified and assigns psychological states to the commodities (the clothing) that “make” the “woman,” so that these conventional norms are interrogated by the voicings of women excluded from their discursive regimes.

Thus the images function as metonyms for the figure of objectified and commodified woman.[16] The textual voicings of the women and the visual images of the garments interrupt and contradict each other, making this self-presentation disjunctive and incoherent. Words and images are in irreducible tension. While such an inverse relationship may seem to foreclose autobiographical subjectivity, in fact it asks us, as viewers, to reexamine our assumptions about the knowability of any subject, unless we put the domains of language and image into sociohistorical context in order to “know” how they contradict each other and destabilize forms of identification.

In sum, at a relational interface, layerings of text and image interplay in ways that can seem either complementary or contradictory. Each elucidates the other, but is not reducible to it. The separateness of textual and visual media is maintained, not blurred. Working at this interface, women artists may conduct a dialogue that simultaneously sustains difference and distinction and enables connections across histories and cultures, as in Stevens’s Rosa Luxemburg and Alice Stevens. At this interface, women artists can also disrupt the viewer’s desire to resolve contradictions and tensions, as in Kelly’s Corpus. The use of relational tactics disrupts the seeming coherence of an autobiographical subject and foregrounds women’s disparate voices, discourses, identities, and desires.

B. Contextualized Interfaces: Documentary, Ethnographic

In a second mode of interfacing, the artist contextualizes her self-representation by explicitly citing sociohistorical sources that situate her individual “I” in a cultural surround. This may be done either through documentary or ethnographic means that embed the experiential history of the subject within texts and/or images of collectivized memory.

At a documentary interface, the textual is used to situate the visual—whether an image, installation, or performance—within a context of social and cultural meaning. That is, artists assemble and juxtapose such documents of everyday life as newspapers and official records to place the autobiographical subject in a sociocultural surround. These practices make visible the official, often stereotyped, histories through which women’s lives have conventionally been “framed” in order to interrogate them. In her essay in Interfaces, for example, Jennifer Drake explores Adrian Piper’s use of documents in her installation entitled Cornered (1988). In Cornered, two birth certificates hang on the wall near a monitor that plays a videotape of Piper addressing the visitors seated before it. Next to the monitor is a table turned on its side. The two historical documents provide evidence of the fluidity of the social category of “race” and thus racial identity: one registers her father’s identity as “octaroon”; the other registers his identity as “white.” This doubled documentation reveals cultural confusion about reading “color” visibly off the body. In her accompanying monologue, Piper explores this cultural confusion about the readability of her own identity, an indeterminate identity “inherited” from her father and played out in everyday life by her cultural position as an African American woman of white appearance. Piper’s situating of birth certificates against her videotaped address deconstructs historical discourses of American racial difference and recontextualizes the conventional meanings of “whiteness” and “blackness” as arbitrary. As a contemporary racialized subject, Piper acknowledges that she’s “cornered” by a normative interpretation of bodily difference. But her juxtaposition of textual and visual media offers a new “angle” or possibility for understanding the instability of seemingly fixed categories of identity, one that “corners” spectators in their assumptions of what constitutes “race.” Using “authentic” historical documents and the public history they invoke, Piper calls into question their truth status and our naive conviction that an autobiographical identity must stay in the corner to which racial politics have assigned it.

Similarly, many life narratives juxtapose verbal stories and photographic histories that narrate multiple, culturally assigned, conflicting versions of racial or ethnic status. Through such juxtapositions, life narrators explore collective histories and the arbitrariness of fixed ethnic identities. For example, Norma Cantú’s Canícula, Sheila Ortiz-Taylor’s and Sandra Ortiz-Taylor’s Imaginary Parents, and Shirlee Taylor Haizlip’s The Sweeter the Juice in different ways interweave family stories with photographs from family albums and historical and familial documents or memorabilia to disrupt essentialist notions of identity. In such texts, photographs, rather than being stable visual markers of ethnic or racial identities, unsettle the fixedness of family history by depicting multiple, disparate, even contradictory versions of it.[17]

The ethnographic is another kind of social contextualization that draws primarily on remembered scenes of collective memory in creating an image or performance that commemorates or revalues a past moment and links the personal to a community, for instance a communal ethnic group. This collective history resituates an autobiographical “I” within a “we” that is indispensable for configuring an identity. That is, the “I”’s meaning is entwined with, read through, the “we” of collective memory and authorized by it. This interface is probed in a series of painted recuerdos by Carmen Lomas Garza. In paintings of what she calls “special events” and “unusual happenings,” Lomas Garza captures the precise details of her childhood and young adulthood in images of collective everyday life in a Chicano community of South Texas to both locate and authenticate her individual experience as transpersonal and exemplary. “I felt I had to start with my earliest recollections of my life,” she has stated, “and validate each event or incident by depicting it in a visual format” (13).

Tamalada (1987), for example, details a cultural milieu in which thirteen members from several generations of a family are shown in various stages of making tamales. Particulars of the room and the familial relationships autoethnographically frame the young artist as a participant in a process that is collective and ritualized. The pictures on the wall include one of the Catholic Last Supper as a folkloric event and a calendar with two silhouettes dancing a traditional Mexican dance. All members of the family, except the youngest girl and her caretaker, engage in tamale-making in the kitchen. Some mix the dough in a large pan; others in the seated assembly line cut out the triangular pieces, fill them with savory spices, tomato sauce, and meats, or wrap them in cornhusks and lay them in a baking pan. In this setting “home” is both a private and a social space, and the painting becomes a visual record of familial bonding. Lomas Garza’s use of bright, unmodulated colors and lack of vanishing point perspective incorporate Mexican folkloric traditions of representation; and yet the painting’s status as “art” also places it in the American art market. Enumerating details of a folk tradition, Lomas Garza understands her own life as implicated in communal life. By celebrating her roots in a collective “we” and telling a story of ethnic identification as foundational and enabling, she mobilizes art’s power to “heal the wounds inflicted by discrimination and racism” (13).[18]

In sum, at the contextual interface of documentary or ethnographic practice, a dynamic relay between personal and communal memory reconfigures the relationship of forms of communal memory and reworks the nation’s official memory of a group as devalued or invisible. Working at this interface enables women artists to foreground the experiential history of the identity statuses they bear, and bare. Their representations in various media embody and body forth in culturally specific settings their experiential histories. Particularly for postcolonial and multicultural women artists exploring the relationship of a colonized ethnic identity to a national identity that has, historically, dominated and effaced it, replacing that received history with collective histories of tradition and intimate bonds is a productive means of telling new autobiographical stories.

C. Spatial Interfaces: Palimpsestic, Paratextual

Third, the interface can be spatialized as a site that is permeable, infiltrated either from inside out as a palimpsest or outside in as a paratext. The apparent space of the surface is redefined by its surround; or, alternately, shown as masking a history of previous iterations that can be differently arranged. In either case, the act of putting a seemingly two-dimensional surface into the three-dimensionality of embodied space animates surfaces with cultural residue.

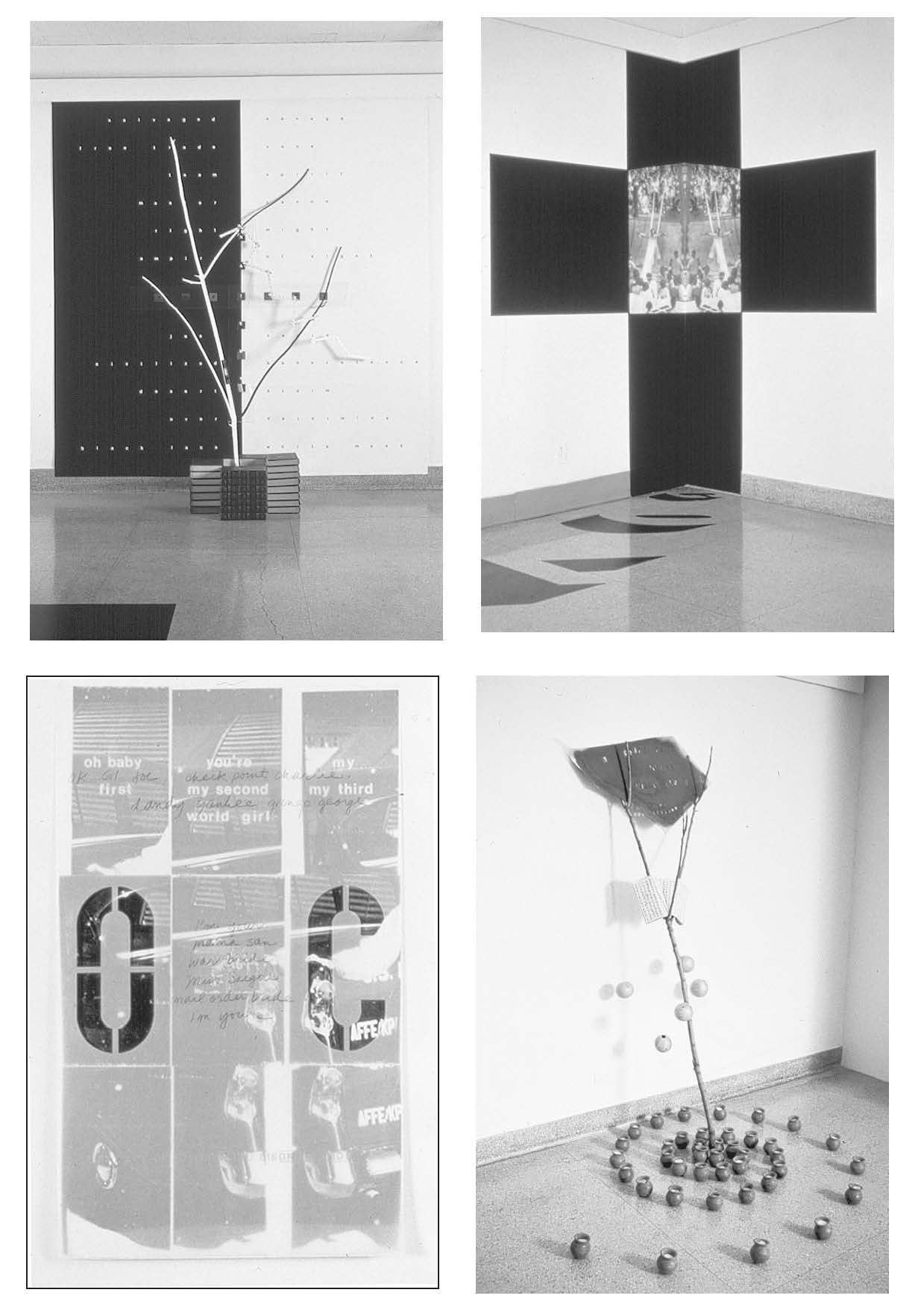

In a palimpsest, one image lies submerged, apparently erased or overwritten by a second image; but traces of what has been erased or overwritten leak through the overlaid surface. The layers underneath, as in an archeological site, house alternative narratives or images that compete with and contest the visible or apparent meaning. For example, the installation by Korean-American artist Yong Soon Min entitled deCOLONIZATION (1991) makes visible the multiple layers of a postcolonial, multicultural identity (Figures 4.1 & 4.2). The installation is punctuated with words, from the “COLONIZE” that adheres to the floor, to the black and white words on a vinyl sheet that capture the binary oppositions foundational to colonizing concepts and events, to the Plexiglas intersection of “NATURE” and “NURTURE,” to a poem written upon the front and back of a dress in English and Korean, to a poem by Martinician writer Aimé Césaire, to the “OCCUPIED” layered over with frosted Mylar. Amid the words that constitute a complex history of discourses of colonialism stands a tree branch of knowledge. A traditional Korean dress hangs suspended from the ceiling. The layerings multiplied in the diverse contexts of deCOLONIZATION suggest the multiplicity of colonizations of Korea by China, Japan, and the United States as a nationalist bricolage. The physical layerings—the dress that hangs layered above the words on the floor, the layers of Plexiglas—combine with the metaphorical layers of the pages of the table of contents of an Encyclopedia Americana and the mirrored images of letters. Taken together, they situate the viewer in the internalized cacophony of external forms of gendered identity. Displaying fragmented objects and letters to evoke in pieces a culture that has been splintered through colonization, Yong Soon Min uncovers the differential effects on female subjectivity of the processes of de/colonization often occluded in official discourses of nation.

The relation of visuality to textuality may also be paratextual. Paratexts are apparatuses that surround or accompany a text. In textual life narrative, paratexts include epigraphs, prefaces, acknowledgments, letters of authentication, et cetera. But there are paratexts in visual and performance art as well. In Marilyn (Vanitas) (1977), Audrey Flack incorporates a long epigraph from a biography of Marilyn Monroe into her meditation on female commodification and artistry (Figure 5). The passage from the biography describes a scene in which Marilyn Monroe spoke of her childhood experience of being made visually beautiful by the application of powder instead of being punished for running away. The biographer’s commentary suggests the importance of the scene in understanding that “one could paint oneself into an instrument of one’s will.” Flack places a childhood photo of herself and her brother between two images of “Marilyn,” one reproduced as if on the opposite page of the biography, the other a reflection of it in a mirror set obliquely at a right angle to the book. In front of the representations of Marilyn—in biography, photo, and reflected mirror image—Flack paints a still life mixing traditional art-historical and contemporary graphic symbols of the vanity of human time as an inevitable process of decay and death: a calendar, a (compact) mirror, overripe fruit, a blue Delft mug, a wineglass filled with pearls that reflects a viewer’s room outside the frame, a half-burnt candle, a timepiece, an hourglass, and an anamorphosic framed portrait to the left of the frontal image of Marilyn. Through her meditation on the fate of Marilyn as a popular icon of femininity, the artist alludes to her own struggle as a woman artist to forge the paintbrush into, in the painting’s phrase, “an instrument of one’s will.” Thus, Flack embeds an autobiographical meditation on gendered difference in a narrative about the distorting effects of cultural representations on what became “Marilyn.” Her portrait probes the production of “Marilyn” as a cultural icon of an impossible woman and the system of gender that celebrated yet destroyed her. This apparent focus on Marilyn also places her, via the “Vanitas” tradition, as a memento mori for Flack. The artist both forges the image and finds her own image as a culturally constructed subject through situating it in the spatial surround of the paratext.

In sum, the complex layerings of autobiographical subjectivity become visible when surfaces project through canny juxtapositions disparate histories, images, identities, all coexisting in the same space. As viewers move through three-dimensional space either literally, as in Yong Soon Min’s installation, or metaphorically, as in the semiotic space of Flack’s Marilyn (Vanitas), they interact with and create the layered spaces of an artistic representation that is both personal and “about” woman. In the process, they inescapably enter into dialogue with the verbal fragments and images they encounter compressed in one space, on one surface.

D. Temporal Interfaces: Telescoped, Serial

A fourth mode of interfacing concerns the temporal contraction or expansion of the stages of an embodied action through which the artist engages in autobiographical storytelling.

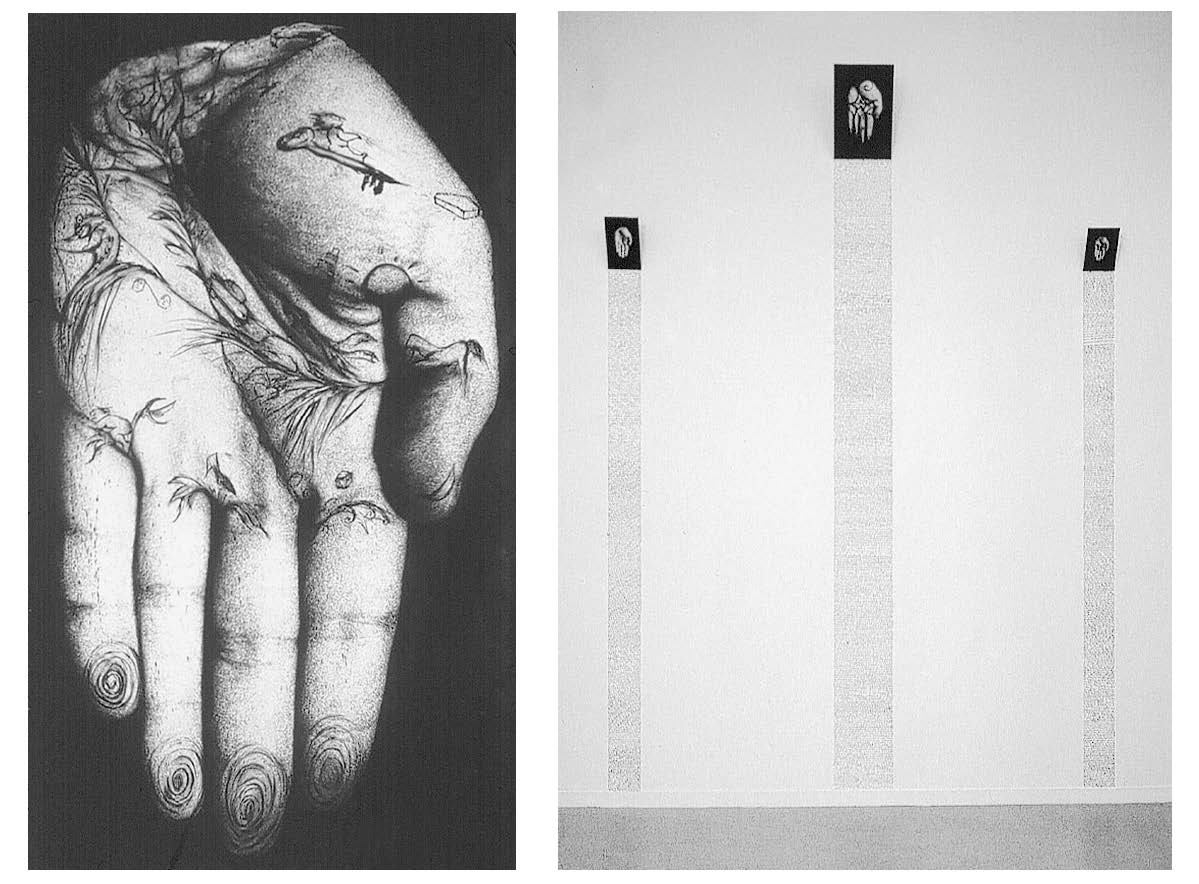

When telescoped, distinct modes, the visual and the verbal, collapse into one another, confusing the viewer’s expectation that their boundary or separation will be maintained. The textual, for instance, may be used as an image, even an architecture. In an installation she titled Les lignes de la main (Lines of the hand) (1987–88), French artist Annette Messager placed close-up photographs of hands on the gallery wall (Figure 6). The enlarged hands, overwritten by various lines and figurations, point downward. Underneath the hands, Messager has written single words directly onto the wall in colored pencil. The words, repeated again and again in narrow columns down the wall, signify particular emotional states, such as fear or confusion. The reiteration of a word, suggests Sheryl Conkelton, “drains meaning from it, reducing the words to mere form; they become instead elements of ritual architecture, visually supporting the images” (24). Yet the repeated words also function, we would argue, as the architectonic elements of autobiographical subjectivity. In their formal organization on the wall, they link the materiality of the body (the images of the body parts to which they are attached) to the unrepresentable somatic markers of internal, psychical states. In another of Messager’s installations, entitled Mes Ouvrages (My Works) (1987), strings of words written on the walls in colored pencil become so many threads used to weave images together into what Conkelton describes as a “diagram” of emotion (24), with multiple emotions/words attached to the imaged objects. In this sense, words do what they seem unable to do—they visualize the autobiographical subject’s private memory museum.[19] Collapsing the word-image distinction evokes a primal experiential core that could not be represented separately by either verbal narrative or single image.

Annette Messager: Les Lignes de la main, 1987–8. Overpainted black-and-white photograph with handwriting on the wall. Courtesy of the artist and Marian Goodman Gallery.

The artistic medium may also become embodied as the subjectivity of the artist, so that performance and body are telescoped. The artist Mona Hatoum, in her two-hour video performance entitled Pull (1995), placed herself in an area hidden from the visitor; only her long ponytail, hanging in a niche in the wall, was visible. Visitors confronted the “real” ponytail and above it a video of the artist, who seemed to be hanging upside down. Invited to “pull” the ponytail by the very title of the piece, they could watch the effect of their pulling on the artist. Assuming the video to be recorded, they saw no connection between pulling the hair and the facial expression on the monitor. In fact, they were pulling the hair of the artist present behind the wall. In other words, the artist was there in person, connected to her hair, not merely represented on the video. Her hair, as Desa Philippi suggests, is here materialized as fetish (369). Body and image, usually separated, were conjoined, compressed in this telescoping of medium and material body. As Guy Brett says of the piece, “at a certain moment the spectacle suddenly ceases to be a spectacle” (74) as visitors are confronted with their own role in causing pain to the artist whose art and body are telescoped.[20]

Hatoum’s installations attach the processes of represented subjectivity to the very materiality of her body, forcing viewers to confront the conundrum of her presence in apparent absence. This absent presence is a central paradox of autobiographical acts and practices. In addition, her installations link “presence” to notions of female excess and women’s embodied subjectivity. If Hatoum’s installations are, in a sense, like Emin’s rumpled bed, synecdoches of subjectivity, Messager’s compressions of word and image are closer to metaphor. Telescoping body and artistic medium, word and image, past and present moments, these artists insist on the coextensiveness of body, language, and art.

Temporal succession may also create a serial relationship in which multiple instances of self-referencing unfold as process. Here wordless visual images are organized in a series that may be linear, geometric, or disjunctive, to tell a story through their sequence and juxtaposition. Many women have represented themselves in a series of related self-images, no one of which would be sufficient to tell the story. Hannah Wilke’s self-images in S.O.S.-Starification Object Series are a series of thirty-five photographs in which she poses as cultural icons whose bodies are scarred/starred with wads of chewing gum shaped to suggest female genitalia. Similarly, Ann Hamilton presents herself, in photographs conceived as studies for her installation work, as a series of “body objects” (1988): sixteen disparate objects, such as a chair, a bush, a paddle, a stove, are shown intersecting her body. In one, for example, a shoe disappears into her face at the site of her mouth and nose (70–72).

Eleanor Antin’s series on weight loss entitled Carving: A Traditional Sculpture presents another set of photographed poses that reiterate, with variation, the artist’s playful shedding of weight as a gradual displacement of female embodiment by negative space on the photograph’s surface. Sequential self-presentation enables women artists to propose subjectivity as processual rather than static and to insist that identity is performative, not essentialized. No single pose or frame of the sequence is the “definitive” or “truthful” self-portrait. In sequential self-portraiture, women artists may engage stages of the life cycle: for instance, performing the childhood past, enacting daughterhood, maternity, professional roles, bodily illness and disability, and aging. In serial self-representation, viewers witness the artist’s body in parts, at angles, inside out, upside down, three-dimensionally, perspectivally. At once discrete and multiple, the embodied subject of serial self-representation stages life narrative as sequence with unpredictable variation. The serialized personal narrative thus enacts a larger story about women’s relation to historical representations of woman and gendered sexuality.

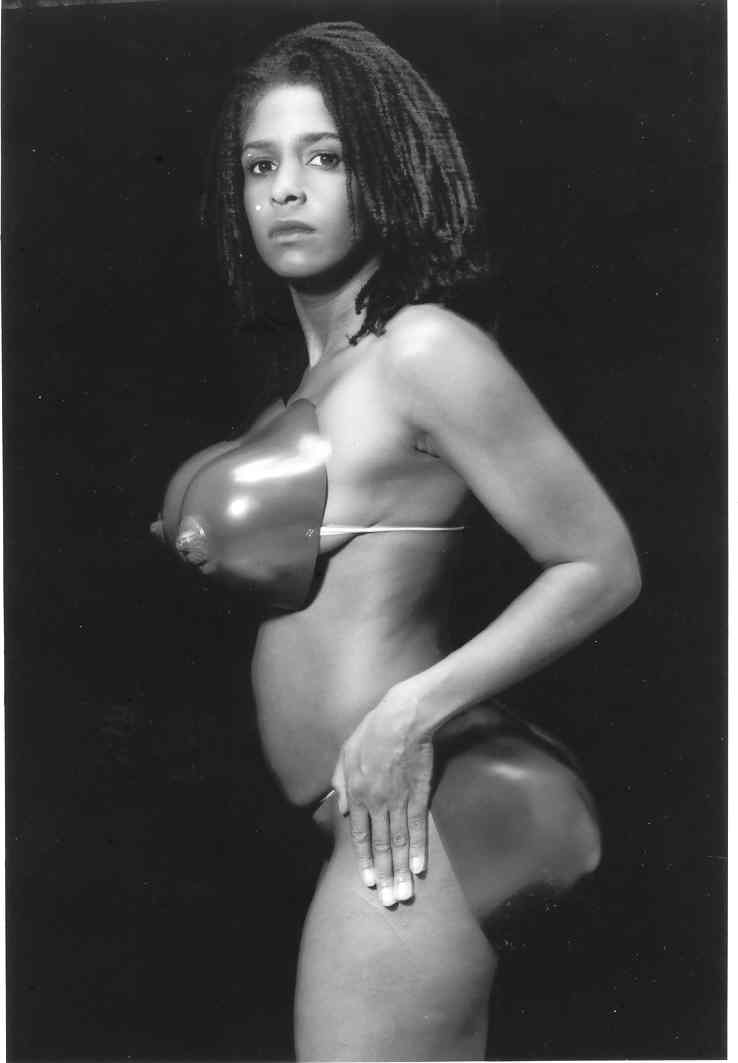

Consider Renee Cox’s Yo Mama series of photographic self-portraits. Through this narrative series Cox, performing the Yo Mama figure of Black street talk, places her own body in various cultural locations and in art-historical and ethnographic cultural intertexts. For instance, in Yo Mama’s Last Supper (1996), Cox assumes the central space of the da Vinci painting, displacing the Christ figure with her own nude self-portrait to intervene in its white, masculine tableau. In Venus Hottentot 2000 (1995), she assumes the place of that fetishized African woman of nineteenth-century ethnography, the “Hottentot Venus” (Figure 7). Through this time-traveling play on place, space, and identity, Cox as an African American woman artist, critiques the history of cultural representations, and absences, of the Black female body. As she “looks” out from those sites of representation not created for her, she asserts autobiographical agency for the gendered and racially marked body (Myers 27).

In sum, women artists and performers, as they mine the possibilities of the temporal contraction or expansion of embodied feelings, actions, and statuses, ask to have their embodied subjectivity reseen in time through telescoped or serialized modes of self-presentation. Doing so, they explore and expose the dynamic processes through which women experience the materiality of a female subjectivity constituted through gendered and raced codes of cultural intelligibility. Often alluding to other cultural texts in a range of verbal and visual media, these artists renovate iconic stereotypes to create a composite subject of difference and resistance. At other times, they expose the disappearance of the subject into the gaps and absences of codes of cultural intelligibility; or they expose the tenuous differentiation of embodied materiality and imaged representation.

Conclusion

We do not claim that these four modes of the interface are the only possibilities for producing meaning at a visual/textual matrix. But we do see them as suggestive of the heterogeneity, ambiguity, and complex intersectionality of the visual/textual interface in autobiographical acts. While we have focused on the importance of gendered representations specific to women’s art practices and tactics for subverting normative femininity, we suggest that these modes of visual/textual interfacing have been particularly productive for women artists and performers engaging the gendered politics of artistic production in the last century and the legacies of their own inheritance as embodied subjects. Ultimately, these autobiographical acts at the interface work intersubjectively. That is, they force us as viewers, who are addressed in and by the works, to participate actively, and oftentimes uncomfortably, in negotiating the politics of subjectivity. They invite us to confront our own participation in “othering” the text, the image, and the “woman” embodied before us. They prompt us to re-vision the spectacle of femininity and to remake women as cultural agents of the autobiographical interface.

Our model for reading the interface suggests one way of approaching women’s visual and performance art through the lens of autobiography studies. It cannot, however, account for the complexity of diverse practices of self-representation staged by visual and performance artists that are the subject of the essays in Interfaces, which expand the repertoire of modes of women’s self-portraiture and theorize more extensively the nature of autobiographical subjectivity at a visual/textual interface that has often been underread, overread, misread, or read exclusively as mimetic self-referentiality. These essays seek to capture the heterogeneity, complexity, and hybridity of women’s self-representational practices at the visual/verbal interface. Such modernist artists as Baroness Elsa and Claude Cahun perform kinds of gender-bending transgression now commonly attributed to postmodern performance artists. And work such as Faith Ringgold’s quilts is more productively read through an autoethnographic model attentive to new histories of racialized subjects than through an exclusively postmodernist frame.

We decided against organizing Interfaces by medium—photographs, painted self-portraits, installation, performances—because so many of the artists discussed work across media in a dynamic interplay among visual, textual, and aural media as sites of the autobiographical. The four sections of Interfaces, which map sites of visual/textual interfacing around, loosely, the body, space, diaristic lives, and visual storytelling. “Acting Out the Body” explores how the embodiment of subjectivity composes both material and metaphoric critiques. “Performing Spaces” gathers essays in which subjectivity is situated in a range of gendered spatio-temporal surrounds that are both visualized and interrogated. “Serial Lives/Imaged Diaries” takes up the juxtaposition of visual and performance diaries as distinct practices. “Visual Narratives” pursues multi-medial constellations that are simultaneously material, image, and text. The essays in Interfaces thus offer new readings that engage with the stakes of autobiographical self-portraiture and performance at the interface of regimes of visuality and textuality. Attentive to the materiality of self-presentation, they examine ways in which specific women artists engage a history of artistic or performance modes of representing “woman” and the woman artist’s relationship to disciplines and institutions of subjectivity. The essays ask how the personal, as experienced and remembered, may be linked to the politics of gender and visibility and the norms of visual and discursive regimes through particular theoretical lenses—psychoanalytic, feminist, materialist, postcolonial, multicultural, rhetorical, or postmodern. As such, they illuminate issues of subjectivity, agency, embodiment, and identity that mark the self-presentation of autobiographical artists in the modern and postmodern world.

Notes