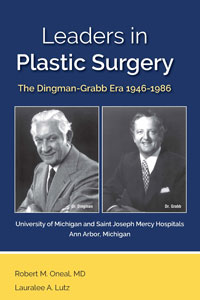

Leaders in Plastic Surgery

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

CHAPTER NINE: Reflections and Commentary about Their Ann Arbor Plastic Surgery Experience by the Authors, Residents, and Fellows

All the alumni, residents, and fellows were asked to comment on their memories of the residency training program during the Dingman-Grabb era. Their comments follow, both quoted and, with permission, edited.

Ernie Manders wrote,

Harken back with me to a golden era in the history of plastic and reconstructive surgery. It was a time of schooling up for the intellectual land rush that was to become modern plastic surgery. Drs. Reed O. Dingman and William C. Grabb had established a Division of Plastic Surgery at the University of Michigan. At last, our specialty had a place at the academic table. Despite the vision of these two leaders, were they standing here today, I have no doubt that both would be immensely surprised—and gratified, at the view of plastic and reconstructive surgery today.

Were our founders here, they would be most happy to see the enduring friendships and loyalties that they and their staff inspired. They would be amazed at the development and everyday use of muscle flaps, free flaps, tissue expansion, breast reconstruction as a full time job, liposuction and lipoaugmentation, hand surgery including wrist and distal radius, vascularized composite allograft transplantation, and craniofacial surgery. They would be amused to learn that after all the high tech introductions of lasers, mechanical peels, and alternative chemical peels, nothing works better for skin resurfacing than the old phenol peel with the classic Baker formula. They would smile at the ups and downs of the facelift literature, and feel some pride, I am sure, in learning that it is largely still best as they taught it to us with a SMAS and skin tightening, I was so lucky to fall under the spell of plastic surgery.[1]

Paul Izenberg discussed the changes he witnessed:

Reflecting back on the late 1970s and early 1980s, it was a time when plastic surgery was changing from a limited array of operative procedures to numerous new approaches to difficult problems allowing innovation—from the fairly standard facelift, rhinoplasty, pressure sore care, random pattern flaps to open rhinoplasty, multiple plane facelifts, musculocutaneous flaps, microvascular surgery, bone plating, subpectoral augmentation, and the beginnings of breast reconstruction. These are just a few of the innovations that began then and progressed to the present amazing field of which we’re all now involved.[2]

Ernie Manders added,

To this day, I am stunned to recall how young the rest our staff was! In retrospect, they were not much older than us. They knew a lot, though, and taught with a pleasure that I remember today. Drs. Bob Oneal, Hack Newman, John Markley, Dennis Bucko, and Paul Izenberg were simply excellent. They were then joined by Eric Austad and Lou Argenta. Each had a special interest to share. I still think of Dennis Bucko and his lessons on oculoplastic surgery. Building on what he taught us, I have done quite a bit of this work with great satisfaction. And I have taught it to keep the flame alive within plastic surgery.[3]

Bruce Novark in 2010 wrote,

This brings back a lot of memories. We worked hard, learned a lot, and there are many cherished memories.[4]

Bruce sent some additional thoughts in 2015:

What a great experience it was: surrounded by a wealth of fine faculty and a challenging patient population. We worked hard but never felt mistreated or demeaned; a sense of real collegiality prevailed between the residents and faculty.[5]

Larry Berkowitz commented on his impression of plastic surgery in Ann Arbor:

I will say that Ann Arbor provided some of the most productive individuals in both the academic and private realm. The number of lives that were improved and touched by that endeavor must be immeasurable. There will always be those who contribute more than others. Despite tens of thousands of operative procedures, I always wished that I could have left behind a legacy of well-trained, ethically endowed individuals as you (the professors) have done. It is better than a textbook or an instrument with your name on it.[6]

Tom Hudak reflected on the importance of his training:

I will always be grateful for the time that I spent at the University of Michigan. It was very special. We always had plenty of input from the staff and the residents. All of the people in the program at that time were well-trained surgeons and that provided a stimulating atmosphere for learning. On the whole, I thought the program prepared us well for applying our skills in the outside world. I am not sure that everyone enjoyed taping splints or taking out the mail. We were weak in our cleft-lip training and strong in the maxillofacial area. Bob, you were always available for consultation and Lauralee was a good sounding board for the residents’ complaints.[7]

Richard Anderson sent his very personal reflection:

You may recall that I had practiced otolaryngology for 10 years and had been thinking about taking a plastic surgery residency for several years. I did interview for a position with Jack Anderson, a then well-known facial plastic and rhinoplasty surgeon in New Orleans. Jack advised me to do a “real” Plastic Surgery residency like Jack Gunter did at Michigan. Later, I did interview for a plastic residency position at Michigan in 1982, as you may recall, and Dick Pollock was chosen that year. After that I was very fortunate to visit with Paul Izenberg and Dr. Dingman at a cosmetic surgery meeting in Birmingham, and they both advised me to put my name in again for a residency position in 1983. I did and the rest is history. Was I lucky or what![8]

Ron Wexler added his impressions:

Every day in my residency was a day of revelation. Everyday brought new problems and answers. Every day I felt that I am improving my skills as a surgeon under the guidance of my teachers . . . this was a stimulating experience.[9]

Issac Peled recalled why he chose Ann Arbor for his fellowship:

After completing my training as a plastic surgeon and in the military service and against the opinion of the chairman of the department where I trained in Tel Aviv, I decided to apply for a clinical fellowship [even though] my chief considered that I was well trained. Getting to know personally Dingman and Grabb was like being introduced to the “real ones” whom I knew only from reading. I was impressed by the level and the friendliness of the staff including the residents who were carefully chosen and reached key positions in our profession.[10]

Rounds and Conferences

Lenny Glass recollected,

Weekly bedside rounds were great, too bad it has, I guess, disappeared in most places [programs]. Trauma [teaching] great for its time, much of it today is obsolete, but then, it was state of the art.[11]

The Thursday teaching conference remains a positive factor for Richard Anderson:

The Thursday morning [conferences] sessions were always educational, often exciting, and memorable. I was impressed that you [Oneal], John, Paul, Hack, and sometimes Eric were there and contributed so much to the meetings, along with Lou, Tom, Dr. Dingman, Steve Mathes [one year] and other full time dept. staff. Actually, the entire teaching staff was outstanding and amazing.[12]

Paul Izenberg commented on the challenges for the junior residents:

These conferences were a little nerve wracking for the junior residents as the seniors presented difficult or up and coming patients for an operation and the juniors knew they would have to answer all the questions from the attendings. We all survived it but at times it was an uneasy feeling.[13]

The Saturday bedside rounds left positive memories for Grant Fairbanks:

One will never forget the Saturday walking rounds at the university hospital large open wards with many beds. One Saturday morning, Dr. Dingman was being asked many questions regarding one patient or another. It was the usual long entourage of residents, interns, and medical students but on this particular day, Dr. Dingman was in a hurry to be somewhere else. He finally stopped and made a simple but profound directive which covered all options. He turned and said, “Review the situation and do what needs to be done.” He then made his exit. In that simple directive, he demonstrated his confidence in his plastic surgery resident team and their ability (already trained general surgeons), to recognize problems for what they were and solve them. Although we valued his knowledge and advice, we didn’t need to be “spoon fed.” His advice served me and others well for what lay ahead.[14]

Resident Selection Experiences with Dr. Dingman (ROD)

Jim Stilwell (Saint Joseph Mercy Hospital [SJMH] plastic surgery resident, 1960–62) recalled the “procedure” for selecting residents circa 1960:

My favorite memory is how I got to be a resident in Dr. Dingman’s program. In the spring of 1960, I was a third-year resident in surgery at the Medical University of South Carolina in Charleston and was working with Dr. Robert Hagerty in the lab. Dr. Hagerty called me one day to get down to the auditorium to hear Dr. Dingman as visiting professor speak to a large group of doctors. I spent the next thirty minutes listening to the most fascinating program with slides that I had ever heard. Afterwards, I told Dr. Hagerty I wanted to be in Dr. Dingman’s program and he said, “I thought you would.” He then invited me to his home to meet Dr. Dingman. During the evening, Dr. Dingman made an appointment for me to meet him at the Ann Arbor VA Hospital two days later. I flew up to Ann Arbor the next day, met and scrubbed with him and answered his questions for about eight hours. He then took me to his home, made me a Scotch and soda, and introduced me to his wife and Bill Grabb. On the way back to my hotel, he stopped the car and looked at me for a very long time and then said, “Jim—I guess you have got the job. But you have got to learn to speak English!!” I flew back to Charleston, worked on my drawl, and started at SJMH in July, 1960.[15]

A recollection from Dr. Jim Norris offers additional insight into Dr. Dingman’s character and judgment about selecting residents. In 1971, Jim, who was black, had applied to two other residency programs in addition to the University of Michigan (UM). He sent his application to one and they asked for a photograph, which he sent, and he never heard from them again. He applied to another one of the New York hospitals, and he was not even offered an interview. Jim continued,

Contrast that with the hospitality shown on my interview with Dr. Dingman in Ann Arbor. I was invited to go on rounds with him and in his office afterwards he sat down one on one with me and said, “I would like very much to have you join our program.” He was aware that I was going to Northwestern for an interview with Dr. B. Herold Griffith and he suggested I take a week or two to think things over. A week later he called me at Tuskegee to find out how things had gone at Northwestern. I told him it went well. He said, “I know you were concerned about experience in head and neck surgery, but I believe we can offer you adequate training in that. I just wanted to reassure you.”[16]

It is to be noted that the help Dr. Dingman was willing to provide when residents finished the training program was just as significant. Jim, who wanted to relocate to New York City (NYC), recalled Dr. Dingman’s willingness to speak to some of his colleagues on Jim’s behalf before Jim’s visit there. Jim recollected that during the visit several interviews resulted only in an offer for a rather minor position at Harlem Hospital with no other hospital affiliation. When Jim came back to Ann Arbor, Dr. Dingman wanted to know all about his visit to NYC. Jim described this meeting:

When I returned to Michigan I saw Dr. Dingman at Mott Hospital. He was preparing to operate on a child and he turned to me and said, “Jim, how did things go with you in New York City?” I related my experiences, particularly with the most egregious circumstance. Dr. Dingman turned beet red in the face, poked a finger in my chest and said, “Look, if you want to go up to New York City and work at Harlem Hospital that is your decision, but don’t let those New York fellows put you in a box and label you as a black plastic surgeon. You are as well trained as any plastic surgeon in New York.”[17]

This quote really says a lot about Dr. Dingman and his acceptance and promoting of his trainees based on their character and performance.

Dr. Dingman’s Outside Activities beyond His Plastic Surgery Practice

Dr. Dingman loved hunting of all varieties. He made many trips with friends including big game hunting. He loved duck hunting in Canada and fishing in Lake Michigan. Ernie Manders recalled,

Dr. Dingman had incredible stamina. On one day in the OR doing an all-day aesthetic case, we neared the end at about three in the afternoon. Dr. Dingman said, “Ernie, I have to go duck hunting on the Indian reservation in Canada. Can you finish up?” “Yes, Sir, I said.” The next day on coming down to the OR here was Dr. Dingman as usual sitting in a dictation cubbyhole and reviewing his charts for the patients that day. “Ernie” he chimed, “great hunting yesterday. Bunch of ducks for you in the freezer in the nursing station on Fourth Floor” [Photo 64].[18]

Lauralee remembered,

In the spring Dr. Dingman brought me peonies from his garden. He would fill our bathroom sink in the office with water and put the flowers in and then he would leave me a note “look in the bathroom sink.”

She also recollected another adventure. Dr. Dingman loved taking photographs and always had a camera ready for all occasions:

One morning I put on a tape from ROD and was very surprised. He announced he was dictating from the roof of his home on Chestnut Road so he could record leaks and flaws in his rubber roof. Just the idea that he was walking around on his roof scared me. My function was to faithfully transcribe this inspection so that he could talk to the roofing company, lawyer, or whoever came to check it out [Photo 65].[19]

ROD’s Personal Anecdotes/Adages

Bob Wilensky recollected Dr. Dingman’s adages such as “if you take a pig with loose skin and tighten the skin you have a pig with tight skin” and “you can’t turn a peach into a carrot.”[20] Ted Dodenhoff recalled ROD’s farewell advice as Ted set off to begin a practice: “He walked me out to the car, shook my hand, and with his usual modest demeanor said, ‘Ted, I’m sure you will be successful. You’ve had the finest training in Plastic Surgery that exists anywhere in the world.’ The perfect finish.”[21] Several of the residents who had come from other countries admired his style. Ron Wexler wrote,

Napoleon said, “every soldier carries in his backpack the Baton de Marechal” (a symbol of dignity) . . . this famous saying came to my mind once when I came to ROD’s office and saw him sitting with his two legs on the table and on the opposite side of the table, one of our medical students with his legs on the same table too . . . and these two people, the world famous professor on one side and the medical rookie on the other were discussing . . . something. This is a view you could see then only in America.[22]

Importance of Photography to Dr. Dingman

Jim Norris related,

Every annual meeting of the ASPS Dr. Dingman would prepare his exhibit on “Plastic Surgeons I have known.” I believe I helped him set up the exhibit almost every year from 1973 until Dr. Dingman no longer attended the meetings. Afterwards, we would set up the carousel and then put it on timed exposure, we would sit down and run through the carousel about twice. I thought this was a really neat part of his photography hobby, but now I think that Dr. Dingman had another motive for putting on that exhibit. In that way, he could refresh his memory about all the faces of plastic surgeons he had known. Maybe I am wrong, but I recall his colleagues were often amazed that he had total recall of their names.[23]

Lauralee recalled,

Dr. Dingman loved to take pictures and then to review the slides on his light board table he had in the basement of his office. He had thousands of before and after patient slides suitable for teaching residents but also for lecturing at meetings. His dictum was “you can never take too many slides.” Dr. Dingman felt that a certain shade of blue wool fabric was an ideal background for his photographs and only one store in Ann Arbor (Fabers Department Store) had this exact shade of blue. Every resident and staff had a large piece of this fabric folded in his camera case, as important as a roll of film [Photo 66].[24]

Dr. Louis Mes observed, shortly after he began his residency, that Dr. Dingman was quite a stickler about his photographs:

Shortly after I joined the residency program and began with the SJMH rotation, he called me into his office one day and quietly asked me if I had taken the pictures that he had spread over his desk in front of him. Proudly, I assured him that I had and waited for his praise. Instead, without saying a word he picked up the trash can next to the desk and swept the lot into it. He did not look up and I slid out of there with my ego in tatters. The matter was never raised again and my photography skills improved exponentially within 24 hours. That is why we respected him and worked so hard for him.[25]

Bob Wilensky, early on, learned another important requirement for photography:

Dr. Dingman insisted that a photograph should never be taken that was not suitable for presentation at a national meeting. Clean towels around the wound, no blood in the field, patients face not showing if it was not part of the operative field. He also insisted on patients not having makeup if that was possible or at least having the photographs match pre and post operatively with hairstyles, makeup and so forth.[26]

Graduations

Grant Fairbanks recalled the significance of an informal graduation ceremony:

Graduation from the Plastic Surgery program in 1971 was without great fanfare. Dr. Dingman invited Carl Berner and myself to a small restaurant on the west side of downtown Ann Arbor [most likely the Town Club] where the three of us had lunch together. He presented us with a certificate signed by himself and Director of University Hospital as well as Chairman of the Surgery Department. There were no speeches and no fanfare, but the strength and warmth of Dr. Dingman’s personality was pervasive. He gave us both a signed photograph of himself—his classic one—inscripted with “Best Wishes Reed O. Dingman, M.D.” We were now full-fledged Plastic Surgeons approved by our Chief. It was enough of a sendoff.[27]

Another Memorable Event

One of the most frightening operating room events for Lenny Glass turned out to be a result of his wartime Vietnam experience. Just prior to beginning the residency in Ann Arbor, Lenny was in the army as a surgeon and stationed in Vietnam for a year. While there in an outpost, his unit was shelled by the Viet Cong many times at night, and he learned to seek cover reflexively, usually under his cot. In his first year of residency, he and I were operating together on a cleft lip patient at SJMH. In those days, the surgical field suction apparatus was connected to a large glass bottle under the head of the table. Suddenly, the bottle imploded, and it sounded just like a bomb. I looked up, and Lenny, across the table from me, had completely vanished. In a few moments, he reappeared having reflexly dived under the operating table.[28]

Memories of Visiting Professors

The UM residency training program benefited from a large number of very distinguished visiting professors. As Grant Fairbanks wrote,

Dr. Dingman was able to attract excellent visiting professors for our program. One such person was Mr. John C. Mustarde from Scotland, an MD trained in both plastic surgery and ophthalmology, who had written an authoritative textbook on ophthalmic plastic surgery. Dr. Dingman asked me to serve as a part-time chauffeur for Mr. Mustarde, and Carl Berner, my residency mate, was the other chauffeur. One of us picked him up at Detroit Metro Airport and the other delivered him back. Such personal contact with Mr. Mustarde was a highlight. He signed my copy of his book with reference to me as his chauffeur. He gave us some profound insights into ophthalmic plastic surgery, which would serve us well.[29]

Issac Peled recollected John Mustarde from another trip as visiting professor: “Dingman invited John Mustarde and he was operating at SJMH while I was his assistant in an eyelid reconstruction. One of the kibitzers kicked my ankle and when I looked at him, he whispered in my ear ‘call him Mr. not Dr,’ and this was also a lesson.”[30]

Don Greer shared his experience of having the visiting professor present on a Saturday: “The most impressive memory of those rounds is of the visiting professor offering a new and insightful and usually helpful comments on every single patient. It was an awesome display of clinical knowledge from a surgeon far out of his usual field of practice.”[31]

About Dr. William C. Grabb (WCG)

Bruce Novark remembered Bill Grabb as the “consummate organizer, thinker, administrator, and author—a whirlwind of academic activity”[32] Grabb’s leadership is recalled by Ernie Manders: “Dr. Grabb was very much involved in the leadership of organized and academic plastic surgery.” He also remembered his own first face-lift procedure as a senior resident undertaken with Grabb’s supervision.

I took my place on the right side of the table. Dr. Grabb was concentrating on doing paperwork, reading galleys, editing them, and even dictating notes in the corner. “Go ahead,” he said. I must confess that I did somewhat resent the fact that the master was not carefully watching my every move. Later I understood the message: “You can do it and we trained YOU to do it!” It has informed my teaching [philosophy] on our reconstructive service at Pittsburgh. Another important lesson he taught was to champion others with good ideas. It was he who stood up and wrote a supporting commentary for Dr. Chedomir Radovan’s first paper on tissue expansion. He helped get him on national programs. He invited him to Michigan. Due in part to Dr. Eric Austad’s brilliant innovation of tissue expansion with an osmotic expander, Dr. Grabb’s mind was open to the idea of tissue expansion long before any of his contemporaries.[33]

Lauralee recollected that Dr. Grabb enjoyed writing and editing books and articles concerned with plastic surgery education. He published several texts, was an excellent editor, and wrote many journal articles but always found time for outside activities. He was a devoted sailor and raced a Snipe almost every Sunday afternoon at Barton Pond; in winter, he occasionally sailed an ice boat, close to the icy edge. He also crewed for friends on much larger boats in the Detroit to Mackinaw race almost every year. Besides these activities, he was a hot-air balloonist, the first one with a license in Michigan. He received his inspiration at a party at the Oneal’s home where he admired Zibby’s collection of paintings of eighteenth-century hot-air balloon ascensions. “On one weekend, he went to South Dakota to learn how. His balloon was red, white, and blue and named ‘the Yankee Doodle’ (see Photo 67). It was a one-man balloon and had no basket. It had just a seat like a swing”[34] (see Photo 68). Someone, usually one of his family members, would have to track him, whichever way the wind was blowing and follow him until he landed, occasionally in a corn field, to pick him and the balloon up. Lauralee recalled, “He sponsored many balloon ascensions from a field near his home and frequently entertained all the members of the Section of Plastic Surgery and their friends and wives for very festive afternoons”[35] (see Photo 69). Ballooning became quite a passion for Bill who had a love of flying even before his tenure in the US Air Force. When Dr. Millard asked him whether he wrote his books while in the air, he admitted, “No, once up, I spend most of my time figuring how to get back down!”[36] He began to spend summer vacations with his family at the US National Hot Air Balloon Championships, and in 1971–73, he served as president of the Balloon Federation of America during which, in 1972, he flew over the Alps in Switzerland in a two-man balloon. In 1978, he flew over the US continental divide in a gas balloon with two other pilots, and in 1980, he participated in the XIII Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York, by flying over the stadium. He was inducted posthumously into the US Ballooning Hall of Fame in 2012.

The comments that follow were selected from Malcolm Marks’s Grabb Lecture at the ROD Society meeting in 2007 in Ann Arbor.

He first spoke about his admiration for Bill Grabb as well as Bill’s many talents: “Bill Grabb created for us a unique atmosphere for academic pursuits that was stimulating, challenging, and pleasurable. His great talent for teaching set an example in humility and honesty, which will always remain dear to us. We are extremely honored to have had the privilege of studying with such a kind and knowledgeable man.”[37]

He then spoke honoring the recent retirements of Drs. Newman, Markley, and Oneal:

I have deep respect and admiration for those I talk about today as well as the respect and admiration for this program. Those I talk about have helped shape the way I think, teach, and live and I am forever grateful.

There is a group of us who have been educated by all of those we honor today: doctors Dingman, Grabb, Oneal, Markley, and Newman and that group is the bridge from the past to the present for several teaching programs in the United States. With the retirement of Drs. Oneal, Markley, and Newman, an era is coming to an end. These are the guys who helped build the foundation of what is undoubtedly one of the most prominent programs in America. They are the people who helped guide this program through difficult and tumultuous stages. They are the people who were here when others were leaving and others were coming and every resident who has trained here for over thirty years owes them a debt of gratitude.

Hack Newman, with all his knowledge and talent, always made you understand that he felt privileged to be able to teach. He brought to the plastic surgery department the knowledge and approach of a veteran otolaryngologist. He has been recognized nationally and internationally for his expertise in rhinoplasty and has been an invited speaker for a multitude of courses and panels. He was honored by his fellow plastic surgeons in Michigan serving as their society’s president for two years. Dr. Newman has the unique ability to make everyone feel like his friend. I fondly remember being invited to their home shortly before graduation along with Bob Gilman and Glen Harder for dinner and samples of wine that I either didn’t know about or couldn’t afford at the time. I never saw him angry, upset, or frustrated no matter what we did or didn’t do. He shared his skill in pediatric, craniofacial, cosmetic, and head and neck surgery and taught a lot more than just medicine. His joy and love of life is contagious.

John Markley has proven that in the right environment, an environment that as I said makes this program so special, you could have a successful private practice and as well as pursue a career-long involvement in teaching and research. We all know that John initiated the research with Dr. Faulkner that is going on today, was the lone microsurgeon in the early days of microsurgery here, and continued to develop technical and intellectual skills that few of us can achieve.

He was writing articles related to skeletal muscle adaptation and facial nerve paralysis thirty years ago and was one of the first to write about neurovascular tissue transfer. What amazed me about Dr. Markley when I was a young resident was how someone could be so smart and still be in such good shape. I was used to meeting the occasional person who was one or the other, but not both. He is as knowledgeable a hand surgeon as one can be and has shared his knowledge with countless young surgeons over a very long career. He taught the importance of anatomy and attention to detail while moving forward efficiently. He did this at the same time he ran his practice and maintained a level of physical condition that enables him to pursue and enjoy athletic skills at an age that most people are beginning to take things easy. Despite what he might say, I have no doubt that his kayaking is already at a high level.

Bob Oneal is a man who has had as great an impact on me as any man I have had the privilege to work with. He too has spent a huge part of his professional life teaching because of his love of our profession and his love for teaching. I still remember the hours that he and Paul Izenberg spent dissecting cadavers, learning every possible detail about the anatomy of the face and later the nose in preparation for the Dallas Rhinoplasty course. Over the course of his career, he has at different times become an expert in cleft lip and palate, breast surgery, facial aesthetic surgery, anatomy of the face, and rhinoplasty. As a resident, it was Dr. Oneal as much as anyone who made me want to learn more about something than I really needed to know. His general knowledge about everything related to plastic surgery made me want to read more. He taught me not to be satisfied with less than the absolute best you can achieve and to be savagely critical of your work and results. He taught me the importance of humility, and along with Drs. Grabb and Argenta, it was his influence that made me want to stay in the university environment.[38]

Lauralee observed (and she insisted the following remarks about me be included),

Bob Oneal is humble by nature and a worrier by experience. While we were working on this book, he often worried about praise directed to himself. He felt that favorable remarks for him shouldn’t be included as it was immodest. I told him the combo was always Dingman/Grabb/Oneal and he couldn’t be left out. Residents often mentioned that Bob was a favorite (or THE favorite) and I think I know why. Bob never forgot how he felt during his residency. It was natural for him to be sympathetic and fraternal, especially during times of overwork and stress. I believe he chose the necessary but difficult role as Resident Advocate and friend as his major contribution to the success of the program—and no one did it better.[39]

Bruce Novark called Oneal his favorite teacher: “He always inspired me to analyze and think about the surgical problem at hand, to consider the various possibilities and approaches to solution. He would discuss the advantages and disadvantages—his experience and that of others with each prospective procedure. Others would say or imply: ‘this is how I do it.’ Certainly I learned from those experiences, but not as much or as productively as when Bob was the teacher. He then always demonstrated great and kind patience in guiding the neophyte surgeon through the exercise. His influence ‘stuck.’”[40] Issac Peled wrote, “Working and socializing with Bob was a great pleasure, although he thought that I couldn’t stand his surgical rhythm, it took longer than others but I heard and learned from him besides the meticulous performance that ‘in six months’ time nobody will ask how long did the surgery take.’”[41]

Grant Fairbanks added, “Bob Oneal was always there for the residents. Bob’s constancy and his unwavering loyalty to the program, to ROD and WCG and to the residents in training, left an indelible impression on me.”[42]

About Lauralee Lutz

In her own words, Lauralee described more memories and experiences:

ROD thought I was in charge of everything. He would announce “there are no hand towels in the men’s room” and I had to figure out how to get them or “can you arrange to have these windows washed.” My answer was always “Yes” and I would figure out later how to do it. One of ROD’s favorite lunches in the hospital cafeteria was a hardboiled egg and a dish of cottage cheese. When residents joined the service, he reminded them not to discuss patients while in the food line or in the elevators as you never know when the relatives were going to be there. Good advice. Dr. Dingman always had a great day when Mr. Kilgore from Coldwater, Michigan, would show up. He sold human skulls (we think he dug them up in Mexico). Lou Argenta and ROD always chose the most abnormal skulls for their personal collection. For several years, ROD gave each graduating resident a real human skull in a black box. The residents considered this the best possible gift. I think this might be illegal now, so plastic skulls are on the market.[43]

Bruce Novark observed, “Lauralee was our angel in the office next door, our literary leprechaun. She was always the faculty’s right hand and resident’s knowledgeable buddy, helper, and encyclopedia on U of M Plastic Surgery—and Shakespeare.”[44] According to Issac Peled, “It didn’t take me much time to realize that the Section was directed by Bill but organized by L3. She had the answers to almost everything and would take care of any single detail. I am pretty sure that all of us would have taken L3 as ‘charge d’affaires’ of our practice and managing our department.”[45] In 1984, Lauralee published “Shakespeare on Plastic Surgery” in the Plastic and Reconstructive Surgery journal, where she recorded fifteen quotes related to various aspects and procedures in plastic surgery: “Allow not more than nature needs” (King Lear, act 2, sc. 4) as applied to reduction mammoplasty is an example of her familiarity with the Bard but also her understanding the many aspects of our specialty.[46] Ernie Manders recollected Lauralee quoting the Bard, “How poor is he who hath not patience. What wound didst ever heal but by degrees?” and then ends by saying: “I have searched for 35 years for another Lauralee and I have learned THERE IS ONLY ONE!”[47]

To Conclude . . . a Potpurii of Memories and Reflections of Dr. Dingman

From the early 1960s to 1976, the first-year resident at Ford rotated for six months at SJMH in Ann Arbor to gain more pediatric and cosmetic surgery experience. These residents shared call and day-to-day patient responsibilities with the UM resident rotating through St. Joe and were considered integral participants in the training program. Don Ditmars (Henry Ford Hospital [HFH] rotator, 1970) reflected on his impressions and recollection of his training experience in Ann Arbor:

In the middle of the 1960s, Henry Ford Hospital plastic surgery residents began rotating with Dr. Dingman at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor for six months. During this time, they were responsible for every patient in the operating room and also were in Dr. Dingman’s office for pre- and postoperative evaluations and care. These were primarily cosmetic patients. However, the Henry Ford residents also were involved with Dr. William Grabb’s patients, which were mostly reconstructive cases. Dr. Robert Oneal joined this group at the latter part of the decade. As one of those residents, I realize that I got more from that rotation than just observing the masters at work. We learned how to interact with cosmetic patients. The concept of backing up our work with free revisions as necessary was part and parcel of this very effective interaction. We were involved with the preoperative planning, which was sometimes innovative and always involved medical photography. The use and composition of standard photography for rhinoplasty was invaluable. Almost of equal importance, this was our first interaction with medical students who were eager to learn. Becoming effective teachers was part of our experience at the time, which stayed with us when we returned home to Henry Ford Hospital to complete our residency and then as we went into practice. In summary, it was a real privilege to be able to be with a true early Master in Plastic Surgery.[48]

Don Greer observed, “On the very last day of my residency, as a going away present, I was given permission to assist Dr. Dingman on one of his cases, which happened to be a rhinoplasty, on a lady physician. Halfway through the case, things started going badly. The room became very quiet. And then even quieter. Time really dragged. Several options were tried, and finally an acceptable result appeared. We were all glad to flee the room. On the way out, Dr. Dingman draped an arm on my shoulder, and commented ‘Always remember that problems can occur to anyone!’”[49]

Bruce Novark recollected “that Lauralee called Dr. Dingman ‘our gentle giant.’ I remember him as a true gentleman, a giant in the world of plastic surgery and like a father. My father (a tool and die maker) was killed in an auto accident when I was 4 years old. Boys growing up without a dad spend years searching for a ‘father’ a role model, a great mentor. I finally found mine in Dr. Dingman.”[50] Several of the residents saw Dr. Dingman this way. Jim Norris wrote, “Dr. Dingman is the one man that I felt was more like my father than any man I worked with.”[51] Grant Fairbanks agreed, “Without question, Dr. Dingman was a second father to all his residents. He was admired and revered by all.” Fairbanks went on to say, “To receive the private verbal approval of our professor, Reed O Dingman, meant more than any medal, certificate, public honor, or applause. It just made one to want to work harder and strive for greater perfection. In the operating room, Dr. Dingman demonstrated consummate skill. He would give his residents responsibility to the extent he felt they were capable, and frequently more, to allow for their growth. We never wanted to disappoint him. He seemed to inherently know each resident’s limits.”[52]

The following are selected passages from recollections of Harvey Weiss (HFH rotator, 1966):

During my first year of plastic surgery residency, I rotated through Dr. Dingman’s private service at St. Joseph Mercy Hospital in Ann Arbor. We operated with him almost every weekday. The operating room was always filled with visiting professors and other interested plastic surgeons who wanted to see the latest techniques. Dr. Dingman never, to my knowledge, refused any qualified surgeon an audience. The conversations were continuous, spirited, philosophical, practical, and ranged from medicine to sports. He always included the students and nurses. In the operating room, he rarely backtracked and even though he seemed to be moving slowly, there were no wasted motions—a valuable lesson in the O.R. and in life! I wish recent and current residents could have had the privilege of working with this truly remarkable mentor.[53]

As demonstrated by these comments, we all, myself and Lauralee and all the contributors, feel fortunate to have had such a fruitful and meaningful relationship as student, resident, associate, and friend with someone of Dr. Dingman’s energy, vision, and genius. Like so many others who trained and worked with Dr. Dingman, we felt that he was bigger than life and absolutely the most important influence in our professional lives (Photo 70).