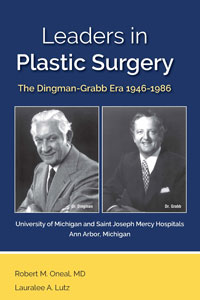

Leaders in Plastic Surgery

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

About Dr. William C. Grabb (WCG)

Bruce Novark remembered Bill Grabb as the “consummate organizer, thinker, administrator, and author—a whirlwind of academic activity”[32] Grabb’s leadership is recalled by Ernie Manders: “Dr. Grabb was very much involved in the leadership of organized and academic plastic surgery.” He also remembered his own first face-lift procedure as a senior resident undertaken with Grabb’s supervision.

I took my place on the right side of the table. Dr. Grabb was concentrating on doing paperwork, reading galleys, editing them, and even dictating notes in the corner. “Go ahead,” he said. I must confess that I did somewhat resent the fact that the master was not carefully watching my every move. Later I understood the message: “You can do it and we trained YOU to do it!” It has informed my teaching [philosophy] on our reconstructive service at Pittsburgh. Another important lesson he taught was to champion others with good ideas. It was he who stood up and wrote a supporting commentary for Dr. Chedomir Radovan’s first paper on tissue expansion. He helped get him on national programs. He invited him to Michigan. Due in part to Dr. Eric Austad’s brilliant innovation of tissue expansion with an osmotic expander, Dr. Grabb’s mind was open to the idea of tissue expansion long before any of his contemporaries.[33]

Lauralee recollected that Dr. Grabb enjoyed writing and editing books and articles concerned with plastic surgery education. He published several texts, was an excellent editor, and wrote many journal articles but always found time for outside activities. He was a devoted sailor and raced a Snipe almost every Sunday afternoon at Barton Pond; in winter, he occasionally sailed an ice boat, close to the icy edge. He also crewed for friends on much larger boats in the Detroit to Mackinaw race almost every year. Besides these activities, he was a hot-air balloonist, the first one with a license in Michigan. He received his inspiration at a party at the Oneal’s home where he admired Zibby’s collection of paintings of eighteenth-century hot-air balloon ascensions. “On one weekend, he went to South Dakota to learn how. His balloon was red, white, and blue and named ‘the Yankee Doodle’ (see Photo 67). It was a one-man balloon and had no basket. It had just a seat like a swing”[34] (see Photo 68). Someone, usually one of his family members, would have to track him, whichever way the wind was blowing and follow him until he landed, occasionally in a corn field, to pick him and the balloon up. Lauralee recalled, “He sponsored many balloon ascensions from a field near his home and frequently entertained all the members of the Section of Plastic Surgery and their friends and wives for very festive afternoons”[35] (see Photo 69). Ballooning became quite a passion for Bill who had a love of flying even before his tenure in the US Air Force. When Dr. Millard asked him whether he wrote his books while in the air, he admitted, “No, once up, I spend most of my time figuring how to get back down!”[36] He began to spend summer vacations with his family at the US National Hot Air Balloon Championships, and in 1971–73, he served as president of the Balloon Federation of America during which, in 1972, he flew over the Alps in Switzerland in a two-man balloon. In 1978, he flew over the US continental divide in a gas balloon with two other pilots, and in 1980, he participated in the XIII Winter Olympics in Lake Placid, New York, by flying over the stadium. He was inducted posthumously into the US Ballooning Hall of Fame in 2012.

The comments that follow were selected from Malcolm Marks’s Grabb Lecture at the ROD Society meeting in 2007 in Ann Arbor.

He first spoke about his admiration for Bill Grabb as well as Bill’s many talents: “Bill Grabb created for us a unique atmosphere for academic pursuits that was stimulating, challenging, and pleasurable. His great talent for teaching set an example in humility and honesty, which will always remain dear to us. We are extremely honored to have had the privilege of studying with such a kind and knowledgeable man.”[37]

He then spoke honoring the recent retirements of Drs. Newman, Markley, and Oneal:

I have deep respect and admiration for those I talk about today as well as the respect and admiration for this program. Those I talk about have helped shape the way I think, teach, and live and I am forever grateful.

There is a group of us who have been educated by all of those we honor today: doctors Dingman, Grabb, Oneal, Markley, and Newman and that group is the bridge from the past to the present for several teaching programs in the United States. With the retirement of Drs. Oneal, Markley, and Newman, an era is coming to an end. These are the guys who helped build the foundation of what is undoubtedly one of the most prominent programs in America. They are the people who helped guide this program through difficult and tumultuous stages. They are the people who were here when others were leaving and others were coming and every resident who has trained here for over thirty years owes them a debt of gratitude.

Hack Newman, with all his knowledge and talent, always made you understand that he felt privileged to be able to teach. He brought to the plastic surgery department the knowledge and approach of a veteran otolaryngologist. He has been recognized nationally and internationally for his expertise in rhinoplasty and has been an invited speaker for a multitude of courses and panels. He was honored by his fellow plastic surgeons in Michigan serving as their society’s president for two years. Dr. Newman has the unique ability to make everyone feel like his friend. I fondly remember being invited to their home shortly before graduation along with Bob Gilman and Glen Harder for dinner and samples of wine that I either didn’t know about or couldn’t afford at the time. I never saw him angry, upset, or frustrated no matter what we did or didn’t do. He shared his skill in pediatric, craniofacial, cosmetic, and head and neck surgery and taught a lot more than just medicine. His joy and love of life is contagious.

John Markley has proven that in the right environment, an environment that as I said makes this program so special, you could have a successful private practice and as well as pursue a career-long involvement in teaching and research. We all know that John initiated the research with Dr. Faulkner that is going on today, was the lone microsurgeon in the early days of microsurgery here, and continued to develop technical and intellectual skills that few of us can achieve.

He was writing articles related to skeletal muscle adaptation and facial nerve paralysis thirty years ago and was one of the first to write about neurovascular tissue transfer. What amazed me about Dr. Markley when I was a young resident was how someone could be so smart and still be in such good shape. I was used to meeting the occasional person who was one or the other, but not both. He is as knowledgeable a hand surgeon as one can be and has shared his knowledge with countless young surgeons over a very long career. He taught the importance of anatomy and attention to detail while moving forward efficiently. He did this at the same time he ran his practice and maintained a level of physical condition that enables him to pursue and enjoy athletic skills at an age that most people are beginning to take things easy. Despite what he might say, I have no doubt that his kayaking is already at a high level.

Bob Oneal is a man who has had as great an impact on me as any man I have had the privilege to work with. He too has spent a huge part of his professional life teaching because of his love of our profession and his love for teaching. I still remember the hours that he and Paul Izenberg spent dissecting cadavers, learning every possible detail about the anatomy of the face and later the nose in preparation for the Dallas Rhinoplasty course. Over the course of his career, he has at different times become an expert in cleft lip and palate, breast surgery, facial aesthetic surgery, anatomy of the face, and rhinoplasty. As a resident, it was Dr. Oneal as much as anyone who made me want to learn more about something than I really needed to know. His general knowledge about everything related to plastic surgery made me want to read more. He taught me not to be satisfied with less than the absolute best you can achieve and to be savagely critical of your work and results. He taught me the importance of humility, and along with Drs. Grabb and Argenta, it was his influence that made me want to stay in the university environment.[38]

Lauralee observed (and she insisted the following remarks about me be included),

Bob Oneal is humble by nature and a worrier by experience. While we were working on this book, he often worried about praise directed to himself. He felt that favorable remarks for him shouldn’t be included as it was immodest. I told him the combo was always Dingman/Grabb/Oneal and he couldn’t be left out. Residents often mentioned that Bob was a favorite (or THE favorite) and I think I know why. Bob never forgot how he felt during his residency. It was natural for him to be sympathetic and fraternal, especially during times of overwork and stress. I believe he chose the necessary but difficult role as Resident Advocate and friend as his major contribution to the success of the program—and no one did it better.[39]

Bruce Novark called Oneal his favorite teacher: “He always inspired me to analyze and think about the surgical problem at hand, to consider the various possibilities and approaches to solution. He would discuss the advantages and disadvantages—his experience and that of others with each prospective procedure. Others would say or imply: ‘this is how I do it.’ Certainly I learned from those experiences, but not as much or as productively as when Bob was the teacher. He then always demonstrated great and kind patience in guiding the neophyte surgeon through the exercise. His influence ‘stuck.’”[40] Issac Peled wrote, “Working and socializing with Bob was a great pleasure, although he thought that I couldn’t stand his surgical rhythm, it took longer than others but I heard and learned from him besides the meticulous performance that ‘in six months’ time nobody will ask how long did the surgery take.’”[41]

Grant Fairbanks added, “Bob Oneal was always there for the residents. Bob’s constancy and his unwavering loyalty to the program, to ROD and WCG and to the residents in training, left an indelible impression on me.”[42]