Coming of Age: Teaching and Learning Popular Music in Academia

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Teaching Popular Music in the Music Theory Core: Focus on Harmony and Musical Form

Introduction

Where, when, and how to incorporate popular music in the undergraduate music theory curriculum has been the subject of intense discussion in recent years, especially as research regarding popular music theory and analysis has become increasingly prolific and prominent in the music theory profession. Though there have been recent calls from outside music theory circles to completely revise the undergraduate music theory curriculum foregrounding popular and world music,[1] the most likely place for popular music analysis to find a foothold in the near future is as a part of the current music theory core.

This chapter identifies ways that popular music is currently incorporated in some music theory textbooks for the music theory core curriculum and considers two case studies that illustrate how teaching harmony and musical form as employed in popular music is at odds with the overall content of a standard music theory undergraduate curriculum, especially if the popular music is viewed as a part of an extended Common Practice.[2] The chapter concludes with consideration of why it is essential to include popular music in the undergraduate core, preparation of teachers to engage this material, and where to go from here.

Current Treatment of Popular Music in the Context of Traditional Core Theory Courses

For at least the last half century, the traditional objective of core music theory courses for undergraduate music majors has been to prepare students to analyze music from established eighteenth- through early twentieth-century canonic Western concert music repertoires: recognizing typical and atypical harmonic, melodic, and formal practices; labeling and interpreting rhythmic and metrical features; and identifying style and genre. Common Practice harmony (as currently taught) balances harmonic progression and functional aspects with voice-leading—smooth, conjunct, parsimonious connections in each voice or part between chords. In this scenario, harmonic progressions and successions can be explained either with reference to functional categories (such as root progressions, or tonic, predominant, and dominant in the T-PD-D-T phrase model) or as “linear progressions” (such as sequences, functional area expansions, and voice-leading chords), where the smooth connection through voice-leading obviates the necessity for strong root motion.[3] There is an assumption that all parts of the texture coordinate with the harmonic progression (with the exception of pedal points and other well-understood contexts), that embellishing tones outside the harmony can be identified and labeled, and that all parts of the texture are in the same key or mode until a key change.

When basic theory curricula include repertoire composed after 1900, the most common repertoires studied are early twentieth-century nontonal music (Bartók, Stravinsky, Schoenberg, Webern, and their contemporaries), perhaps with some works by Debussy, Ravel, and other composers. The repertoire selected for both Common Practice and post-1900 music focus on male European composers and works within concert music traditions, with a smattering of American composers such as John Cage and minimalists in the twentieth-century materials, though several recent prominent post-1900 textbooks have actively engaged some works by non-Europeans and women.[4] With few exceptions, popular music repertoire was completely excluded from these courses until around the turn of the twenty-first century, and even now, many traditional university core music theory textbooks and courses do not include popular music examples.

When popular music has been incorporated in textbooks and course teaching materials for the music theory core, the most common approach is to find musical examples that seem to be “doing the same thing” as examples from the Common Practice repertoire and to sprinkle them in among the Common Practice examples. For music fundamentals topics, such as reading pitches; identifying intervals, chords, and scales; and understanding rhythmic and metrical elements, popular music examples can easily be included if they are chosen carefully to legitimately fit the criteria of the topic they are being used to illustrate and if they are employed as “positive” examples (what to do, instead of what not to do), like other music literature engaged in such a course. It does not take much effort to include popular music terminology and concepts where they fit into the study of fundamentals, such as introducing popular music chord symbols alongside the Roman numerals when triads and seventh chords are introduced. Indeed, excerpts can be included later in the curriculum as well, particularly from older popular music, such as Broadway show tunes and jazz standards, where the harmonic practices conform to Common Practice progressions and voice-leading for the most part, with only additions of chord extensions and harmonic elements—like the added sixth—that can be easily illustrated and explained.

Integrating popular music theory and analysis into topics in the music theory undergraduate core beyond the fundamentals presents notable challenges, especially if the teacher would like to present a popular music example along with each core content topic. Popular music examples are readily available for some topics, such as harmonic sequences, but for others—such as Neapolitan sixth chords or augmented sixth chords, which are not typical of popular music—convincing examples are difficult to find. Though the viewpoint persists among music theorists that popular music is a continuation of the tonal Common Practice, problems arise if one attempts to treat all post-1950 popular music with the same approaches as older tonal music, because many of these late twentieth- and early twenty-first-century pieces simply do not conform to eighteenth- and nineteenth-century standards. This is particularly obvious in the area of harmony, as the two case studies that follow will illustrate. Music theorists have taken two approaches to this issue: adapting older analytical methods for the new repertoire—which works well enough for some repertoire and not as well for others—and exploring new means of describing and theorizing the new harmonic patterns of popular music. This process of theorizing new approaches to harmony in popular music is an ongoing pursuit in the field of popular music theory and analysis—one where students and teachers can be a part of the exploration.

First Case Study: Katy Perry, “Roar”

To consider a few ways that popular music harmonies diverge from the Common Practice, start by listening to a recent example that I hope will be familiar to you—and certainly will be to almost all your students: Katy Perry’s “Roar.”[5] Please find a recording of this piece online and listen as you read about each of the examples. While there are a number of interesting aspects of this song, for now, focus on the melody, bass line, and chord progression throughout, and also listen for the keyboard part, which enters first in the introduction. You might also want to read the text, which is significant in shaping of the song’s form. Listen first to the entire track while following along on the form chart in Example 1 to become oriented to the song (especially if it is unfamiliar); the measure counts were determined by conducting along in 4/4 meter.[6]

The first minute and a half of the track spans the first large A section (verses 1 and 2, prechorus, chorus, and postchorus) of a composite quaternary form (A A′ B A″) through the beginning of the third verse, which audibly marks the end of this large section. This excerpt is followed by a second A′ section (with only one verse), a relatively short bridge, or B section, and a final A″ that only includes the chorus and postchorus, which completes the song. As is typical of recent songs in this genre, the larger sections (e.g., A, A′) consist of multiple smaller sections. Repeated text plays a role in identifying the smaller sections: both the prechorus and the postchorus have the same text each time they return, which differentiates them from the verse; the verse has a different text each time it returns, revealing the protagonist’s changing thoughts about her situation. The prechorus text reflects the protagonist’s gradually increasing sense of self-advocacy and command of her situation, brought out through increasing intensity and energy in her voice and culminating in the dramatic anacrusis (“I’ve got the eye . . .”) into the high-energy chorus. After the chorus, the repeated “Oh oh oh” text of the postchorus distinguishes it from the chorus, while the decrease in energy level from its height in the chorus prepares for the return of the relatively low-intensity verse.

| A | Verse 1: | “I used to bite my tongue . . .” | (4 measures) |

| Verse 2: | “I guess that I forgot . . .” | (4 measures) | |

| Prechorus: | “You held me down . . .” | (4 + 4, for 8 measures*) | |

| Chorus: | “I got the eye . . . [refrain]” | (8 measures*) | |

| Postchorus: | “Oh oh oh . . . [refrain]” | (5 measures*) | |

| A′ | Verse 3: | “Now I’m floating . . .” | (4 measures) |

| Prechorus: | “You held me down . . .” | (4 + 4, for 8 measures*) | |

| Chorus: | “I got the eye . . . [refrain]” | (8 measures*) | |

| Postchorus: | “Oh oh oh . . . [refrain]” | (5 measures*) | |

| B | Bridge: | (instrumental, then) “Roar-oar . . .” | (3 + 4, for 7 measures) |

| A″ | Chorus: | “I got the eye . . . [refrain]” | (8 measures) |

| Postchorus: | “Oh oh oh . . . [refrain]” | (9 measures; extension!) |

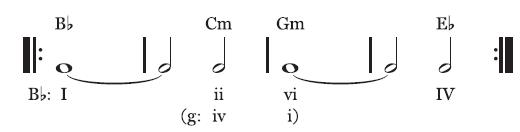

The chord progression throughout the entirety of each of the large A sections includes four chords (B♭, Cm, Gm, E♭), with the rhythm shown in Example 2. In popular music contexts, this type of repeated harmonic progression is called a harmonic loop.[7] The progression, which is repeated throughout the entirety of the song except the bridge, is harmonically ambiguous if considered in isolation, though it is certainly possible to identify a tonic and provide Roman numerals for the chords as I, ii, vi, and IV in the context of the other layers in this song. This progression notably lacks the dominant harmony in the key of B♭ (F). It has an added feature of including two nested plagal progressions—subdominant harmony to tonic (IV-I), if the Cm-Gm is considered iv-i in G minor—and in any case, those chords give a minor presence in the middle of this loop. When the full harmonies are most audible in the chorus (as opposed to primarily hearing the bass line under the verses), the chords are all root position triads connected by parallel motion.

We now return to the keyboard part. It is a two-measure-long loop that features parsimonious voice-leading, though it is essentially a B♭ chord “pedal,” F5-B♭5-D6, repeated twelve times in eighth notes, with B♭5 replaced by an upper neighbor tone (C6) for the last four eighth notes to finish out the two-measure-long unit. Like the four-measure-long bass and chord pattern, this two-measure unit is looped throughout the song, with the exception of the bridge, forming an ostinato. The keyboard part’s insistence on the B♭ triad prevents the Cm and Gm chords from presenting G minor as a contender for tonic.

The song’s melody also influences how the harmonies are perceived: in this song, the entire melody is based on a B♭ major pentatonic scale (B♭, C, D, F, and G), except for the bridge. The melodic line is structured around arpeggiations of the B♭ major triad (B♭3-D4-F4), with C4 primarily as a passing tone between D4 and B♭3, and G4 as an upper neighbor to F4, until the vocal range expands upward in the chorus. There the melody moves from F4 to G4 to B♭4 and on up to B♭4-C5-D5 in the upper register, bringing out the “gapped” nature of the pentatonic. The melodic line itself is quite repetitive, with one measure or shorter melodic segments separated by rests, except in the chorus, where the short melodic segments are connected together and sung more continuously. The metrical placement of the melodic segments provides insight into the character’s progress from “zero” to “my own hero”: in the verse, the text reveals her uncertainty, represented rhythmically by entries of the melodic segments after the downbeat of the measure; as she gains confidence in the prechorus, some of the segments have an anacrusis to the downbeat of the measure, making the rhythmic placement somewhat more assertive; and in the triumphant chorus, the melodic segments either anticipate the downbeat of the measure or have an anacrusis to the downbeat, beginning with the long anacrusis that elides with the end of the prechorus (shown by the asterisk in Example 1), expanding the chorus to nine measures if the elided anacrusis measure is included. The postchorus reestablishes the placement of melodic entries after the downbeat, preparing for the next verse. As many of the melodic ideas are contained within a measure, the vocal line adds a one-measure layer to the two-measure keyboard ostinato and the four-measure harmonic loop. At this point, I encourage you listen again to “Roar” from the beginning to hear the elements described in previous paragraphs and to listen specifically for the change in the harmonies and melody in the bridge, to which we turn next.

The bridge section features the only arrival of F major (dominant) harmony in the song, and the melody here (repeating the hook lyric, “roar”) moves G4 to F4, then G4 to A4, and finally B♭4 to C5, emphasizing the chord members of the F major harmony, which leads into the final return of the chorus and postchorus. From the viewpoint of harmony through the lens of harmonic function and prolongation, the song’s harmonies express T (for a very long time!)-D-T.

Considering this song from the perspective of Common Practice harmony, there are not a lot of similarities other than that it is diatonic overall (based on a B♭ major pentatonic collection—a diatonic subset), it has triadic harmonies in one of the layers, and it is possible to identify a tonic. The T-PD-D-T (tonic-predominant-dominant-tonic) phrase design is completely absent, as are any standard harmonic cadences. It exemplifies instead many features that, individually and collectively, are typical of a variety of popular music styles and that are not typical of Common Practice repertoire, including nonfunctional harmonic loops, parallel voice leading (or planing of chords), and semiautonomous layers (coordinated, but each working according to its own principles) in the voice, keyboard part, and the bass/harmonic loop (and drum parts). The chord succession features harmonies in a plagal relationship instead of a tonic/dominant axis. In addition, there is no final cadence in the Common Practice sense—the harmonic loop simply loops to the end, landing on a B♭ harmony.

In Common Practice repertoire, the melody and harmonies are constructed such that the melody coordinates in both pitch and rhythm with the harmonies. On the contrary, in many recent popular styles, there is no presumption of coordination: the melody does not have to fit the chords, and even if the melody and chords end up at the same harmony, they do not have to do so at the same time. This is the result of the construction of songs in layers, where any part of the texture could have been the starting point: a harmonic progression, an instrumental riff, lyrics, a groove, the melody, or something else altogether. The construction of songs based on harmonic loops (repeated 3–4 chord sequences), shuttles (alternation between two chords), and other repeated progressions as a part of a groove reflect a different role for harmony in the texture and in creating musical form than does the T-PD-D-T basic phrase. Often these loops by themselves are harmonically ambiguous; the melodic line might identify tonic unambiguously as here, or it might not resolve the question.

Another way that this song does not conform to the Common Practice norms is in regard to voice-leading. In teaching tonal music, we tend to emphasize parsimonious (stepwise) voice-leading, with conjunct and contrary motion as the contrapuntal ideals. The contrapuntal guidelines were drawn from sixteenth- and eighteenth-century music written for choirs with the goal of making smooth, easily singable vocal lines or for seventeenth- or eighteenth-century keyboards following the guidelines of counterpoint and with the goal of moving the hand the least distance. Working with the physical inclinations of the instruments of the “rock quartet”—two guitars, bass, and drums—and other post-1950 popular music ensembles did not lend itself to the traditional tonal voice-leading patterns. Parallel voice-leading is normative for performance on guitars, where commonly employed chords are easily connected using a shift of the hand position up or down the fingerboard. Its meaning in a context is style-dependent: it could represent a “doubling” of a given line with a triad, as is the case in planing, or it could be more timbral in origin, depending on the application of distortion and other performance-related features. Guitar-based voice-leading has become ubiquitous in popular music, including keyboard and synthesized parts where it would be quite easy to employ contrary-motion-based parsimonious voice-leading instead of parallel motion, as performers often follow the lead of the fretted string instruments to connect chords in a consistent way across the ensemble.

Second Case Study: Freddie Mercury, “Crazy Little Thing Called Love”

There are many indications in the scholarship on popular music that plagal harmonic motion might be much more common overall in popular music of the past half century than the dominant-tonic of the Common Practice. Recent corpus studies have documented the prevalence of subdominant progressions over dominant-based ones in specific repertoires.[8] This tendency to have motion involving the subdominant rather than dominant subverts the “dominant paradigm” of Common Practice tonal music.

To examine others of the typical popular music plagal progressions, we will consider another example—this time a much earlier one, from 1979: “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” by the rock band Queen.[9] Find a recording of this song online, and if you are unfamiliar with it, listen through the entire song following the form chart in Example 3. Though this song clearly has blues influences, including the length of the verse and chorus (each of which is twelve bars long consisting of three four-measure-long units) and a statement-elaborated restatement-conclusion organization for the lyrics, it does not follow a standard twelve-bar blues harmonic progression. Listen again, focusing on the four-measure-long chord progression shown in Example 4, which is repeated to accompany the first eight measures of each verse. After a measure of tonic harmony (D), the progression shown in Example 5 completes the verse, accompanying the refrain line “crazy little thing called love.”

Some common popular music progressions, such as the so-called double plagal ♭VII-IV-I (all major triads), on which this song’s repeated progression is based, defy pigeonholing into functional categories. The name “double plagal” comes from the IV-I plagal motion being preceded by the plagal motion IV-I in the key of IV—sort of like a V/V-V-I descending fifths root progression, except that the descending root motion in this case is by perfect fourths. The “Aeolian cadence” ♭VI-♭VII-I is employed here as well, providing closure on the refrain line “crazy little thing called love.”

Both of these progressions feature harmonies that in Common Practice parlance would be considered “mode mixture” or “borrowed” chords, but ♭VI and ♭VII do not appear in the same progressions in popular music as in Romantic-era contexts. The subtonic ♭VII is infrequent in Common Practice music except when employed in conjunction with the mediant ♭III—either in a dominant-tonic relationship in the relative major in a minor context within a Baroque- or Classical-style composition or in a mode mixture situation tonicizing a chromatic mediant during the Romantic era. Furthermore, and their inclusion does not necessarily carry the same implications for musical meaning as these chords would in a nineteenth-century art song, where the presence of mixture chords is often linked to text painting, or in instrumental music, where mixture may invoking Romantic-era images through tone painting.

| Verse 1: | “This thing called love . . .” | (12 measures, 4+4+4) |

| Verse 2: | “This thing called love . . .” | (12 measures, 4+4+4) |

| Chorus: | “There goes my baby . . .” | (12 measures, 4+4+4) |

| Verse 3: | “I gotta be cool . . .” | (12 measures, 4+4+4) |

| Chorus: | “There goes my baby . . .” | (12 measures, 4+4+4) |

| Verse 3: | “I gotta be cool . . .” | (12 measures, 4+4+4) |

| Verse 1: | “This thing called love . . .” | (12 measures, 4+4+4) |

| Outro (Repeat Refrain and Fade) |

Popular music scholar Allan Moore was early to point out the special use of the subtonic (♭VII), listing many songs including it in quite varied contexts.[10] Over subsequent years, this chord has engendered much discussion among scholars specializing in popular music regarding its role and function. The harmony ♭VII is quite commonly used as a dominant substitute in minor-key contexts in folk music,[11] yet it appears very typically in post-1950 popular songs in a major mode context. Mark Spicer indicated that the ♭VII-IV-I can substitute for the V-IV-I at the end of the archetypal blues progression.[12] Christopher Doll labels the use of ♭VII as a “rogue dominant”[13] capable of creating dominant function at a cadence. Drew Nobile controversially goes even further, labeling any harmony leading to tonic as a “dominant,” including IV (which leads back to I in the double plagal progression).[14] Nicole Biamonte theorizes that the progression ♭VII-IV-I should be considered within the context of modal and pentatonic patterns.[15] She takes issue with Walter Everett’s view of ♭VII in the double plagal progression as a neighbor chord of a neighbor chord. Everett would consider the G chord (IV) in “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” as prolonging D (I) as a kind of I-IV-I “neighbor progression”—following the treatment of IV as prolonging tonic as employed in contextual analysis of Common Practice tonal music—and the C chord (♭VII in D but IV of G) as prolonging G in a I-IV-I “neighbor progression” as well, making nested plagal neighbor progressions.[16] While the progressions including ♭VII employed by Queen are only two of many progressions featuring this chord that are commonplace in rock and other popular genres, the range of divergence in viewpoints of these progressions highlight the disagreement in the music theory scholarly community about how to interpret and theorize popular music harmonic progressions that do not have strong associations with Common Practice music. These differences might stem in part from the repertoire each music theorist is examining but also from their position as to the degree to which popular music is a continuation of the Common Practice (with some changes) or something new and different altogether—a new practice—requiring its own theories of harmonic progression and chord connection.

One of the reasons popular music harmony does not consistently follow Common Practice norms is that the harmonic practice in post-1950 popular music draws strongly from at least three musical streams: (1) Common Practice harmony as employed and expanded in Tin Pan Alley and Broadway show tunes—especially those songs performed as jazz standards; (2) the blues, which was an especially strong influence on the Beatles, the Rolling Stones, Led Zeppelin, Cream, and other prominent groups of the 1960s and 1970s; and (3) folk music, including both the types of traditional folk repertoire future musicians learn while children through community and school music programs and the songs that were “rediscovered” or newly composed during the folk music revivals of the 1940s through the 1960s. Many of the frequently encountered progressions from popular music that are not typical of older tonal music are based on harmonies from the blues or modal folk music traditions. Combining these styles has resulted in harmonic progressions that, on cursory inspection, appear to be tonal—in part because they are triadic and it is possible to identify a tonic—but actually incorporate chords in a modal or pentatonic context that might behave quite differently than the “standard” major or minor progressions.[17]

Divergence between the modality or tonality of the melody and of the harmonic progressions is another possibility brought into popular music practice from this combination of influences. For example, in blues and blues-based rock, the melody in blues might be minor-inflected, and in blues-based rock, it might be minor, Aeolian, or Dorian (minor-sounding modes), while the harmonic progression is firmly in a major key. Other combinations of modal and tonal pairings are possible as well. The presence of a melody and harmony that express two different keys or different modes is sometimes called a “melodic-harmonic divorce.”[18] This practice is in contrast to Common Practice repertoire, where even if mode mixture is employed, it is not typical for the melody and harmonies to express different modes.

The Queen song “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” provides an example of the ways major and minor elements can be combined in a blues-based rock song. Though the harmony in the introduction is D major, firmly establishing the primary key and mode of the song, Freddie Mercury’s melody is primarily D Aeolian with a prominent F♮, a minor inflection (e.g., on the syllable han of “handle it,” the word round of “round to it,” and most importantly, on crazy little of the refrain line “crazy little thing called love”). The Aeolian modal identification is confirmed not only by the F♮ (flat scale degree 3) but also by the avoidance in the melody of C♯, the leading tone in D major. The only C in the piece is a C♮ (on the word cool of “cool, cool sweat”), which is immediately answered in the bass part by a C♯. The melody does occasionally include an F♯ (e.g., at the words ready and like in the ninth measure of the verses), in each case accompanied by a strong tonic (D major) chord and text expressing a positive view of his predicament.

Interestingly, the subject matter and treatment of melodic and harmonic elements in the Queen song shares some commonalities with the way mode mixture as employed for text painting in Common Practice repertoire. In this song, the harmonic choices and the melodic inflections are coordinated: the F♮s appear as an accented dissonance above the C major (♭VII) chord in the verse harmonic loop and above the B♭ major (♭VI) of the Aeolian cadence; the C natural is above an F major harmony (♭III) at the end of the chorus. All these would be traditionally considered “mixture chords” in the context of the song’s D major tonality.

While connections between the harmonies and musical meaning expressed in the text cannot be assumed to always be present in popular music contexts employing mixture chords such as ♭III, ♭VI, and ♭VII as would be typical in nineteenth-century art songs, there are certainly songs where that is the case, and text-musical links are worth investigating. For example, “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” is about how crazy and confusing it is to be in love, with emotional states alternating among not being ready to handle it, shaking like a jellyfish, feeling hot and cold, and knowing he must relax, get ready, and take it on. An apt comparison might be made to Mozart’s “Voi, che sapete” from the opera The Marriage of Figaro, where the character Cherubino expresses similarly confusing and contradictory sentiments regarding love, also expressed musically through harmonic and melodic mode mixture.

The I-ii-vi-IV harmonic loop of “Roar” and the progressions including ♭VII in “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” are both nonnormative for Common Practice music and fairly typical in recent popular music. For students who are in the process of being inculcated with traditional employment of tonal harmonic progressions, many popular music harmonic practices present challenges to the traditional harmonic guidelines that they have only recently learned and might seem to be “breaking the rules” because they fall outside of these constraints.

Some Guidelines For Teaching Popular Music Examples

In teaching a popular music example, it is essential to encourage students to evaluate harmony in the song on its own terms by asking questions such as the following:

- What key(s) are expressed in this song?

- What chords are used? What is their relationship to the key or mode?

- What is the relationship of the harmonies to the melody of the song?

- How are the harmonies connected?

- What progressions are present?

- Are there harmonic loops?

It is also essential to consider the relationship between scale, melody, and chords when considering progressions, including questions such as these:

- Is the song tonal or is it modal?

- Are the melody and harmonies expressing the same key or mode?

- What chords are used at the closes of phrases or sections?

Closes of phrases and sections might not be reflected in a harmonic resting point if a harmonic loop or shuttle is employed, and students should be warned to not be surprised if there are progressions treated as “cadential” that are not typical at all of older tonal repertoire.

Interactions Between Harmony And Form

The differences between the conventions of Common Practice music as taught in the music theory undergraduate core and typical practices in recent popular music are not limited to harmony. For example, consideration of musical form can also be problematic, in part because of the ambiguities swirling around interpretation of harmonic progression in recent popular music and because aspects that are considered “secondary parameters” in discussion of elements contributing to traditional tonal musical forms, such as texture, timbre, melodic shape, and rhythm and meter, become paramount features determining formal boundaries in some recent popular music pieces.

Musical form as taught in the undergraduate core curriculum focuses on the identification of cadences to locate and confirm the ends of phrases. Students are taught that there are a limited number of acceptable harmonic cadence types that create and shape musical form at both the phrase and the section level, all involving dominant harmony (V) and either tonic harmony (I, or vi as a tonic substitute) or an avoidance of it (in the half cadence). The “plagal cadence,” or IV-I, once taught as an additional category of tonal cadence along with the perfect authentic, imperfect authentic, deceptive, and half cadences, is discussed in recent textbooks as an expansion of tonic employing subdominant after a conclusive close employing V-I, rather than a means to end a phrase or formal section. Though the consideration of harmonic aspects is the primary determinant of form, the relationships between melodic design and harmonic progressions are also considered in determining whether phrases form period structures, phrase groups, or other phrase forms and in the labeling of formal sections from phrase level to large sections.

In considering musical form in recent popular music, the various means of creating cadences, forming phrases, shaping sections, and combining sections in the piece as a whole often do not conform to terminology and analytical frameworks borrowed from earlier eras and other styles. While the repetition or change in musical materials and in the song’s text continue to be essential considerations in identifying formal units within a popular song, change or continuity in timbre, texture, instrumentation, melodic range, musical layers, and other dimensions that are not the primary determinants in traditional tonal analysis must be considered when harmonic features that were so essential to section identification—such as harmonic cadences and phrase forms they delineate—are replaced by harmonic loops or other harmonic progressions that might continue unchanged from one section to another and do not lead to a cadence.

While the standard cadence types that students will have learned for Common Practice music do appear in some popular songs, particularly those of the 1950s and 1960s (and later songs making reference to those styles), they are not as common as one might expect in many styles of post-1970 popular music. When seemingly familiar cadential progressions do appear, their meaning in context might be different. For example, ending a phrase on V (dominant) occurs quite frequently, including V at the end of a harmonic loop, yet the term “half cadence” might not make sense, as there are many songs where there is no harmonic arrival of a later cadence on I (tonic), nor any assumption that a tonic arrival will happen. Plagal cadences, perhaps stemming from blues progressions, are much more ubiquitous in popular music than in Common Practice repertoire and typically take the place of an authentic (V-I) cadence instead of following one as a tonic expansion. Other types of progressions that would not be considered cadential at all in Common Practice repertoire—such as the Aeolian cadence ♭VI-♭VII-I, or simply ♭VII-I—frequently end musical units that sound and act like phrases, though no V harmony is present.

An additional element of complexity arises in that terminology for components of musical form in popular music is employed in tonal music analysis with a different meaning. Terms such as refrain, chorus, and verse have been used for hundreds of years in reference to many types of music, with nuanced differences in what they refer to depending on the context and time period. For example, I previously referred to the text “crazy little thing called love” as a refrain line, which in popular music contexts of the 1950s through the 1980s is a repeated short lyric, always set to the same harmonic progression and melody, that appears as a sort of “catchphrase” at the beginning or end of the verse or chorus. As in the Queen song, this type of refrain is not an independent section but rather a short (but memorable) component of one. The same term, refrain, is also employed for the returning A section in a Classical- or Romantic-era rondo form (such as five-part rondo A B A′ C A″) or a part of a hymn or song that is repeated after each verse with the same words and music (also known as a chorus).

There have also been significant shifts in meaning within popular music’s own terminology. Refrain, chorus, and bridge are all examples of terms whose meaning changed significantly between the popular music of Tin Pan Alley and Broadway show tunes and the popular songs of the 1960s and 1970s. In early twentieth-century popular song in verse-refrain form, the refrain is the second large section of the song (not a short, repeated melodic fragment like “crazy little thing called love”), repeated with the same works and music, which is typically the most memorable part of the song. A familiar example of verse-refrain form is George and Ira Gershwin’s “I Got Rhythm,” in which the forgettable verse (“Days can be sunny . . .”) is followed by the refrain (which begins with the lyric “I got rhythm” but is an entire section, including several musical phrases). In that style, chorus referred to the repeated “a” phrases within the refrain’s quaternary song form (a a′ b a″), while the bridge is the “b.” Each of these phrases in the quaternary song form is typically eight measures long, making thirty-two-bar song form. This early twentieth-century terminology for verse, refrain, chorus, and bridge was in use by the Beatles and other musicians in the 1960s who knew and performed older popular songs, but the newer use of the term bridge—an independent contrasting section that appears after several repetitions of the verse and chorus to prepare for their return—came into use not long after that, as did the new meanings of chorus and refrain. In postmillennial songs, such as “Roar,” the quaternary formal plan (a a′ b a″) is applied to larger sections that contain at least a verse and chorus pair, possibly also a prechorus and postchorus for a composite A A′ B A″ form, as shown in Example 1.

For undergraduates only beginning to learn about musical form in their core music theory courses, it is clear how these terms and concepts can be confusing if not taught in regard to specific repertoires with the differences in terminology clearly acknowledged and explained. Even something so simple as considering potential connections between musical elements and text setting can be fraught with problems, as the text could have been the last part of the song that was completed, rather than a starting point. Considering the differences between what students will need to understand about popular music and the other topics they are being taught in their “tonal harmony” classes, it is not surprising that some teachers of undergraduate music theory courses choose not to engage these topics. If it is so problematic, why do it?

Why Should Students Study Popular Music Analysis?

Popular music is a significant repertoire of the twentieth and twenty-first centuries and is enjoyed by listeners worldwide as a part of their everyday lives. This repertoire is not “new”—though additional pieces are being composed every day—as this has been an active style since the 1950s. It is a significant oversight for undergraduate core courses that are intended to prepare students for lifelong careers in music to omit from consideration the very music that many of them spend the most time listening to and that surrounds them in their world every day.

As the percentage of music listeners who “consume” concert music shrinks and the number of those who enjoy various types of popular music worldwide grows, there is work available for those who are knowledgeable in this area—not only as performers but also as composers/songwriters, producers, and other roles. Even Classical music performers are often called on to perform popular music works, and some professional chamber ensembles have focused on inclusion of popular music examples to build audiences. To meet these professional requirements, all students—even and especially including those hoping for careers as orchestra members, choir directors, and chamber musicians—need to be exposed to terminology and concepts associated with popular music repertoires, at least to the extent they are introduced to counterpoint, form, twentieth-century techniques, and other core topics.

Incorporating popular music has distinct benefits for the multitude of students in undergraduate programs training as music educators and music therapists, as well as for those preparing for work in music-related professions such as arts administration, music business, and music-related legal services. State standards for music teachers require that they teach popular repertoire as a part of a balanced music program—those who are responsible for educating future educators should not put teachers we train in a position to have to teach materials they have never studied. Students who wish to work as music therapists will be primarily employing popular music in clinical settings, as they select music for therapeutic applications that is preferred by their clients. Our students who put their bachelor of arts in music degree to work in music-related professions will most likely need to be knowledgeable regarding popular music.

Though I have consistently used the term “Common Practice” as a shorthand to designate traditional tonal music of the years 1600–1900, the idea that there is one true “Common Practice” is as much a myth as the assumption that all popular music works the same way—there are vast differences in practice and style between earlier music from the Baroque and late Romantic practices; among choral, keyboard, large instrumental ensemble, and chamber music; and in musics from different cities, countries, and cultural centers. Study of popular music has an added benefit in that it enriches students’ understanding of older repertoire by highlighting the great diversity of musical practices—which should be done as well with Common Practice styles. Finally, studying very recent music builds analytical skills potentially useful for music of the future.

In order for all music majors to benefit, the place to include popular music instruction is in the core music theory courses—even with restrictions on the time and scope of what can be covered. Every music student should have the opportunity to engage these materials. Ideally, a specialized popular music analysis semester-long class would be available for undergraduates seeking more in-depth exposure, and graduate students who aspire to teach music theory should be expected to have training in popular music analysis at a comparable level to their other analytical training.

Teacher (Re)Training As A Necessity

As popular music examples have begun to enter core music courses on music analysis, one of the great obstacles to inclusion of popular music repertoire in undergraduate theory classes is that teachers trained in traditional conservatory or university colleges, schools, or departments of music might not actually know that much popular music. I have spoken with many excellent music teachers who specialized their whole life in European concert music yet think popular music consists of Broadway show tunes that are now more than fifty years old and folk songs, or maybe the Beatles and some Disney songs that they learned by watching movies with their kids. When mentioning to colleagues (especially those who teach vocal, keyboard, or instrumental performance) that I am teaching popular music, a surprisingly common reaction is to inquire why one would do that—“Isn’t it all based on the same three chords?” This lack of knowledge is not limited to age; some of the graduate student teachers I supervise admit they know little popular music, in part because it was not included in their own undergraduate experience. Even those who frequently listen to popular music likely do not have the tools to analyze it with the same level of depth and specificity as other repertoire we teach if they have not been taught this content. If it is a goal to “mainstream” popular music into undergraduate theory classes, this is a serious problem. If university programs wish to incorporate popular music into the undergraduate curriculum, teachers must be knowledgeable about popular music and methods of analyzing it, be able to choose appropriate examples, and understand how to use them in a positive, accurate, and musical-context-sensitive fashion. The best way to make this happen is to teach future teachers how to analyze popular music.

Conclusions

As we have seen through these two brief case studies, incorporating popular music examples into teaching concepts and practices of harmony can be problematic for several reasons. First, the stylistic norms of the Common Practice era—especially as presented in a condensed fashion in most core music theory courses—and the harmonic practices of much post-1950 popular music are divergent, with significant differences in the types of chord progressions, voice-leading, treatment of tonality, and the role of harmony as a part of the texture. The divergence in treatment of harmony also requires a reconsideration of musical form, as the traditional tonic-dominant cadence is no longer present in much recent music. Second, as popular music is a relatively new area of interest for music theorists, there are also fundamental disagreements about how to interpret and analyze common types of harmonic progressions in popular music contexts. The quick pace of basic theory instruction does not allow much (if any) time for unpacking of these conflicts of viewpoint. Third, the chord progressions explored in the rock era (post-1950) are rich and varied. To study them in the same detail as we have the progressions of Baroque, Classical, and Romantic music would require more time than could be allotted without sacrificing other curricular elements or would require a rebalancing of content in the undergraduate core—which likely will happen gradually. For now, we can teach the popular music examples we choose to engage in a nuanced and detailed way. Fourth, teachers need to be trained to teach popular music. We cannot assume they can work with their knowledge of Common Practice music and make the transfer from there. Teaching harmonic practices specific to a broad range of popular music honestly and on its own terms means it cannot be easily subsumed under the Common Practice umbrella, as has been illustrated through examples considered in this chapter.

Acknowledging up front that there is a difference between the use of harmonic materials in post-1950 popular repertoires and their use in typical Common Practice contexts is an essential start; the next step is addressing the differences and encouraging students to listen and analyze recent popular music with an open mind—without expecting the progressions to necessarily follow earlier norms. Fortunately, students with a basic level of music literacy will not have substantial difficulties engaging in analytical investigations of pieces such as those we have heard if they are introduced to repertoire-specific terminology and expectations, use both their aural skills and available scores to engage the music, and are shown how to get started on an analysis.

If we feel that popular music analysis should be taught, the first step is for those who are knowledgeable about the repertoire and who care about this music to begin teaching it. We are more likely to raise a new generation of skilled teachers and researchers if they are trained in what we know already about analyzing popular music—even with our awareness that we don’t know enough about specific topics. To quote Chinese philosopher Lao Tzu (c. 604–531 BC), “A journey of a thousand miles begins with a single step,” which is also sometimes translated as “The longest journey begins from where you stand.” Change in the undergraduate music major curriculum will only come as those of us who teach music theory are willing to take the first step. The research under way toward understanding and analyzing specific repertoires is a starting point, and conferences where information is gathered and disseminated are steps in the right direction. It is incumbent on teachers to be aware of the pitfalls in incorporating popular music into the music theory core curriculum and to have a plan to avoid them. They should choose teaching examples carefully, treat the music fairly, and delve as deeply into this music as any other repertoire they teach. Popular music deserves to be taught on its own terms, as a significant content area of the core music theory courses. Paradigm shifts take time and effort, and repertoire that is new to a teacher takes time to master—but this problem will ease as rising generations routinely study recent popular music as a part of their degree coursework. We have to start somewhere, and it is time to do it!

Notes

1. The call for radical revision has come most notably from a task force organized in 2014 by ethnomusicologist and College Music Society (CMS) president Patricia Shehan Campbell. The task force report, “Transforming Music Study from Its Foundations: A Manifesto for Progressive Change in the Undergraduate Preparation of Music Majors,” was originally issued November 2014 and generated substantial discussion at the Society for Music Theory, American Musicological Society, and Society for Ethnomusicology Fall 2015 conferences, as well as at the College Music Society conference. A copyedited version dated January 2016 is available for viewing or download on the College Music Society website, http://bit.ly/2xWP8so, accessed September 10, 2016. Despite the CMS task force’s claims to the contrary, this is a “zero-sum” game—the number of class hours allotted to music theory instruction in the undergraduate core are limited, and we cannot put something in without removing or minimizing topics that are already included. We can gain a little by efficiencies—such as textbooks or lesson plans that use the time available for student learning as efficiently as possible by excellent organization of content and inclusion of all needed scores, recordings, worksheets, instructional videos, and other materials to maximize instructional time on task—but not enough to add new content without removing topics that were previously included.

2. Though I will use the term “Common Practice” throughout this chapter to represent the traditional core repertoire encompassing music composed with tonal music practices written between about 1600 and 1900, please do not assume that I consider this repertoire to employ tonal practices in a consistent and uniform manner. There are vast differences in harmonic practices between early and later repertoires, among various genres of pieces, and in the particular uses of composers in specific locations and time periods. These are reflected quite clearly in my teaching, as represented in my textbooks. It is simply much easier to say Common Practice than to repeatedly state “Baroque, Classical, and Romantic music” or other terminology.

3. For more information regarding any of these aspects of commonly taught concepts of the basic music theory core curriculum and to gain a sense of the scope of an up-to-date university basic theory sequence, see widely used textbooks such as my own—Jane Piper Clendinning and Elizabeth Marvin, The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis, 3rd ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2016)—or Steven Laitz, The Complete Musician, 4th ed. (London: Oxford University Press, 2015). The Clendinning/Marvin textbook incorporates popular music examples as described in this chapter, as do some other textbooks; it is also the only widely used core music theory book that includes a complete chapter on popular music. The Laitz textbook is more typical in that it focuses on Common Practice repertoire.

4. In addition to the coverage of music after 1900 in the Laitz and Clendinning/Marvin textbooks cited above, representative current textbooks engaging music post-1900 used in undergraduate core courses for music majors include Miguel Roig-Francoli, Understanding Post-tonal Music (New York: McGraw-Hill, 2007), and Joseph Straus, Introduction to Post-tonal Theory, 4th ed. (New York: W. W. Norton, 2016). All these books engage a more diverse selection of music than the serialism and sets of earlier textbooks on twentieth-century music and also include some works by American composers and by women.

5. Composition credits include Katy Perry, Lukasz Gottwald, Max Martin, Bonnie McKee, and Henry Walter for “Roar,” which is performed by Katy Perry on her studio album Prism (2013).

6. This example and others provided in this chapter regarding this song appear in chapter 29 of the third edition of The Musician’s Guide to Theory and Analysis (New York: W. W. Norton, 2016), 610–11, 615; they were developed by this author in conjunction with this chapter prior to inclusion in the textbook.

7. Philip Tagg, Everyday Tonality II (New York: The Mass Media Music Scholars’ Press, 2014), e-book; chord loops and shuttles are introduced and discussed on pp. 371–450.

8. Trevor De Clercq and David Temperley, “A Corpus Analysis of Rock Harmony,” Popular Music 30, no. 1 (2011): 47–70; Christopher White and Ian Quinn, “Harmonic Function in Popular Music” (paper presented at the Society for Music Theory National Conference in St. Louis, MO, October 30, 2015).

9. “Crazy Little Thing Called Love” was composed by Freddie Mercury in 1979 and performed by the rock band Queen on their album The Game (1980); it also appears on their Greatest Hits compilation album (first released in 1981).

10. Allan Moore, “The So-Called ‘Flattened Seventh’ in Rock,” Popular Music 14 (1995): 185–201; see also Allan Moore, “Patterns of Harmony,” Popular Music 11 (1992): 73–106.

11. I am personally familiar with its employment in accompaniments for Cape Breton–style minor-mode (Aeolian or Dorian) fiddle tunes from performing and studying repertoire in this style.

12. Mark Spicer, “Large-Scale Strategy and Compositional Design in the Early Music of Genesis,” Expressions in Pop-Rock Music: A Collection of Critical and Analytical Essays, ed. Walter Everett (New York: Garland, 2000), 106n19.

13. Christopher Doll, “Listening to Rock Harmony,” PhD diss., Columbia University, 2007. This topic is introduced on pp. 68–76 and engaged throughout the remainder of this dissertation.

14. Drew Nobile, “A Structural Approach to the Analysis of Rock Music,” PhD diss., City University of New York, 2014. He introduces this topic on p. 5 and discusses it in detail on pp. 35–88 passim. See also his article “Harmonic Function in Rock Music: A Syntactical Approach,” in the Journal of Music Theory 60, no. 2 (Fall 2016).

15. Nicole Biamonte, “Triadic Modal and Pentatonic Patterns in Rock Music,” Music Theory Spectrum 32, no. 2 (2010): 95–110, reprinted in Rock Music (Ashgate Library of Essays on Popular Music), ed. Mark Spicer (New York: Routledge, 2011).

16. Walter Everett, “Pitch down the Middle,” in Expression in Pop-Rock Music: Critical and Analytical Essays, 2nd ed., ed. Walter Everett (New York: Routledge, 2008). See pp. 154–55 for Everett’s discussion of this point and p. 95 of Biamonte (2010) for her discussion of Everett’s viewpoint.

17. See, for example, Nicole Biamonte, “Triadic Modal and Pentatonic Patterns in Rock Music,” Music Theory Spectrum 32, no. 2 (2010).

18. David Temperley, “The Melodic-Harmonic ‘Divorce’ in Rock,” Popular Music 26, no. 2 (2007): 323–42.