Coming of Age: Teaching and Learning Popular Music in Academia

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 4.0 International License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

“Home I’ll Never Be”: Location, Meaning, Persona, and Realism in the Music of Tom Waits and Bruce Springsteen

Drawing on the field of music geography and traditional musical analysis, this chapter examines the physical locations that Bruce Springsteen and Tom Waits use in their lyrics and why they chose these places. I also examine how they set these places musically to heighten the realism and themes in their respective works. This is done by conducting close readings of the artists’ lyrics and interviews, mapping the lyric locations using Geographic Information System (GIS) software to ensure greater accuracy, researching the historical and social significance of these locations, and performing music analytic techniques to explore connections between the location and themes brought about in the lyrics and the musical performance. In doing so, this chapter reaches across several disciplinary lines to gain a better understanding of the music.

The opening paragraph of Tim Cresswell’s book Place: An Introduction states that “place” is a “concept that travels quite freely between disciplines and the study of place benefits from an interdisciplinary approach.”[1] Cresswell goes on to quote philosopher Jeff Malpas, who argues that “place is perhaps the key term for interdisciplinary research in the arts, humanities and social sciences in the twenty-first century.”[2] This chapter exemplifies how place easily allows for an interdisciplinary approach, as it incorporates elements of geography, music theory, and musicology to gain insight into how place is used in music.

In the 2015 article “‘Miami, New Orleans, London, Belfast, and Berlin’: An Analysis of Geographic References in U2’s Recordings,” geographer Joel Deichmann examines and maps the lyrics of the band U2. From there, Deichmann categorizes the spatial and nonspatial elements of their work, allowing him to demonstrate how the band uses place to highlight certain themes. In doing so, he divides the spatial and nonspatial songs further by subcategorizing the nonspatial themes as “Romantic Love,” “Brotherly Love,” “Spiritual Love,” and “Love of Mother.”[3] The spatial elements are categorized as “US & UK Foreign Policy,” “Conflict,” “Biblical Events,” “Perserverance,” “Addiction,” and “Discovery.”[4] One area where Deichmann’s study falls short, however, is in the connection to the lyrics and their context in a piece of music. In the sections that follow, I hope to build onto Deichmann’s work, demonstrating the value of examining locations in lyrics while also providing examples of how places are illustrated musically through case studies of Tom Waits’s “I Wish I Was in New Orleans (in the Ninth Ward)” and Bruce Springsteen’s “Born in the U.S.A.”[5] I also explore Springsteen’s cover of Tom Waits’s song “Jersey Girl” to examine how Springsteen alters a song to make it better fit his persona.

The notion of physical places carrying associated meaning has a long history in the stories and music of oral traditions. Philosopher David Abram’s Spell of Sensuous (1996) outlines the importance of physical place in cultures ranging from the Australian aboriginals to the American Indians of the southwestern United States. In all these cultures, locations not only represent the physical realm but also host a myriad of spiritual, emotional, and moral connections. Recognizing these connections, American songwriter Lyle Lovett has stated that he does not “insert [locations] into a song as an academic exercise”; instead, he chooses to incorporate a place only when it “evokes the spirit of what it is that [he is] trying to say.”[6] Perhaps in a similar vein, Tom Waits stated in a 1999 interview that “every song needs to be anatomically correct: you need weather, the name of a town, [and] something to eat.”[7] These interviews indicate that places in songs are chosen deliberately and with care. These places are significant to the meaning of the song, the realism of the song, and how the artist is choosing to portray themselves. In addition to Waits, Springsteen, and U2, artists such as Randy Newman, Bob Dylan, Ray Charles, Louis Armstrong, and Neil Young have all incorporated specific locations into their music as a means of heightening realism or highlighting themes.[8] Despite the significance of location in music, there is very little music scholarship addressing the role that place has in shaping an artist’s public persona or its role in adding elements of realism to songs.

Music geographer George Carney echoes David Abram’s sentiment, writing that “place refers to a location, but specifically to the values and meanings associated with that location. A place is a location that demonstrates a particular identity.”[9] In relation to the young field of music geography, scholar Blake Gumprecht states that the field “focuses on origins, diffusion, and distribution of musical styles” while advocating for Susan Smith’s declaration that the field should instead examine “the extent to which sound generally, and music in particular, structures space and characterizes place.”[10] Despite this assertion, much of music geography still focuses on “origins, diffusion, and distribution” with little explanation of why an artist chooses to set songs in certain locations or how these places are illustrated musically.[11]

One of the most recent and comprehensive large-scale studies of popular music and geography is the 2003 book Sound Tracks: Popular Music, Identity, and Place by geographers John Connell and Chris Gibson. Over the course of the book, Connell and Gibson outline the relationship between location and musical style, starting with early American folk and bluegrass. One area where this book falls short, however, is in its study of song lyrics. The authors assert that “the sounds and rhymes of names, rather than the ‘reality’ of place, have often exerted a major role in the choice of location.”[12] In other words, the locations in lyrics are dismissed as insignificant choices made purely for the sonic quality of the place names and not for the extramusical associations that these places might possess.[13]

I chose to examine Tom Waits and Bruce Springsteen for several reasons: they are contemporaries (both released their debut albums in 1973), they have genre crossover with “rock” and “folk rock,” and they are celebrated as American songwriters. Thematically, both musicians’ lyrical output focuses on some aspect of American life. Because they are hailed as songwriters, the lyrics of their music are primarily composed by the artists themselves.[14] Lastly, Waits and Springsteen have cultivated specific personas that exist in their music as well as their public appearance: Tom Waits has spent years cultivating his image as a drunken, bohemian, vagrant poet. Bruce Springsteen, on the other hand, has imagined himself as a patriot and a champion of working-class Middle America.[15] Given the importance Springsteen and Waits place on their lyrics, a close reading of these artists’ use of location gives us a better understanding of how they choose to represent themselves and add realism to their narratives.

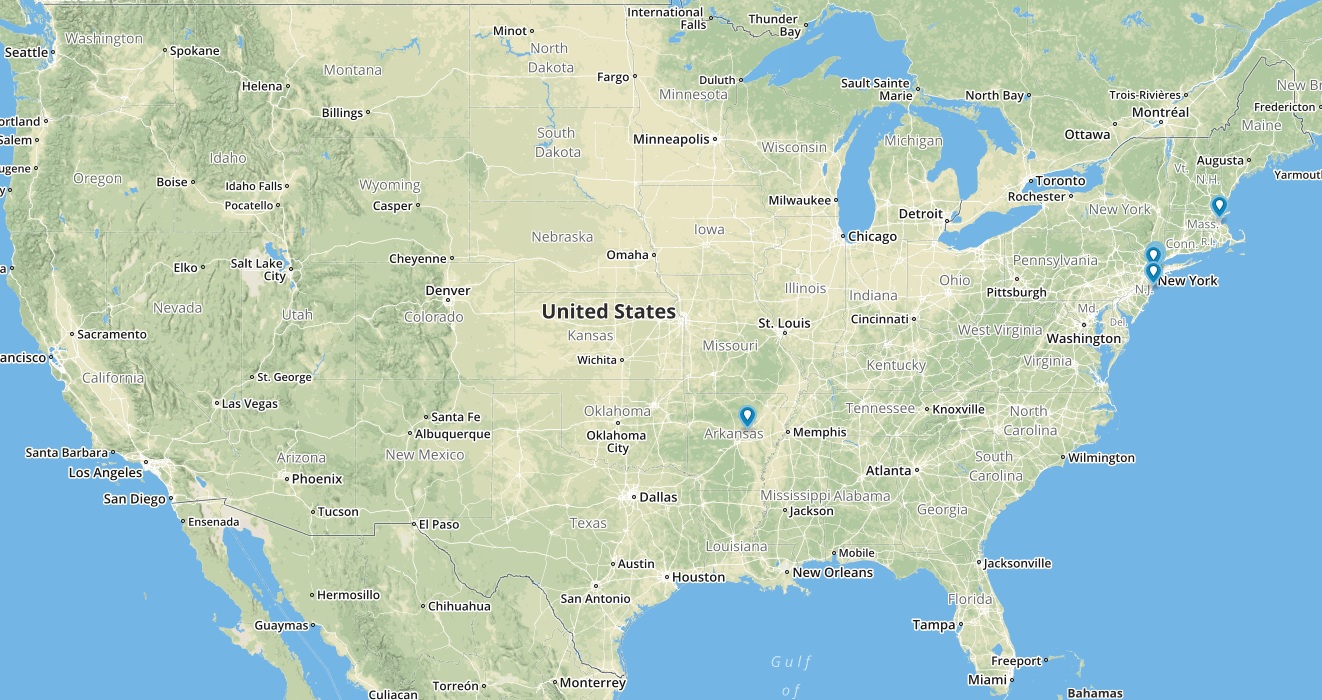

Combined Map

Before delving into each artist individually, examining a combined map of the two artists’ lyrics reveals several similarities and differences among the locations that Tom Waits and Bruce Springsteen choose. The combined map (Figure 1) shows that the densest areas are found on the coasts, primarily New York City on the East Coast and Southern California on the West Coast. This map also shows that Waits’s noncoastal locations tend to lie close to the Mississippi and Ohio Rivers, while Springsteen’s tend to be either in the “Rust Belt” or west of the Mississippi in areas such as Texas, Colorado, and Utah.

There are several reasons for these trends. The first, and perhaps primary, explanation is that both artists originate from coastal urban or suburban areas; Waits is from Pomona, California, and Springsteen from Belmar, New Jersey. A second explanation is that these areas are among the most densely populated areas in the United States.[17] It stands to reason that these areas would be prevalent in either artist’s mind, as these are large areas of commerce, culture, and tourism. Given the size of the cities in these areas, it is certain that both artists traveled through them often, and audiences across the nation are likely to be more familiar with those places and some of the associative characteristics that go with them. Similarly, there might be commercial reasons for focusing on these areas. When discussing U2’s use of location, geographer Joel Deichmann writes, “Given the strong representation of Europe and the United States in U2’s recorded material, it is likely that the band deliberately invokes images of place to appeal to its fans and increase music sales.”[18] Waits and Springsteen might be doing the same with their choices of location.

The differences in international location choices can best be explained by how the individual artists portray themselves in their music. As a politically charged and internationally conscious artist, Springsteen focuses on the areas of conflict that were present in the minds of Americans at the time that he was writing these songs; America was still feeling the reverberations of the conflict in Vietnam, with the Korean War not far behind it. It makes logical sense that, as an artist painting himself as a patriot and mouthpiece for working America, Springsteen chooses to focus his international songwriting efforts in these areas. It is for similar reasons that Springsteen also focuses more on Mexico, as he expresses his stance on immigration through his music. Waits, on the other hand, generally avoids politics in his music and persona in favor of an avant-garde bohemian identity, resulting in more locations in Europe.[19]

Tom Waits

In Tom Waits’s debut album, Closing Time, only two specific locations are named, appearing in a single line of “Midnight Lullaby” as places for the listener to dream of. While these places carry some meaning in the song (one of distant, far-off lands), it is not until his follow-up album that Waits makes use of location to put more meaning and character into his music.

The Heart of Saturday Night (1974) places Waits in his hometown region of San Diego. The setting is given early, as the second song is titled “San Diego Serenade,” priming the listener to hear the rest of the album in this geographical context, including retroactively hearing the opening track of the album, “New Coat of Paint,” as being about the Southern California area. Waits solidifies his and the album’s placement in this region in the song “Diamonds on My Windshield,” in which he mentions Oceanside, San Clemente, and Riverside, California, before closing the album with “The Ghosts of Saturday Night (after Hours at Napoleone’s Pizza House).”[20]

When placing all these points on a map, it is easy to see that the majority of California locations mentioned in this album fall in close proximity to California Route 15 and Route 5 (Figure 2). This is especially intriguing when looking at “Diamonds on My Windshield,” in which Waits describes driving between Oceanside and San Clemente (and briefly mentions Route 5). Mapping these points indicates that Waits has an intimate knowledge of the area and heightens the realism of the lyrical road trip.

After The Heart of Saturday Night, Waits slowly broadens the scope of his music beyond California, from Small Change (1976) onward until Rain Dogs (1985), which focuses primarily on New York City. This is unsurprising because the majority of the album was written and recorded in Manhattan, where Waits was living at the time. Much like how he used specific locations to show off his knowledge of Southern California and prove himself as a real figure there, Waits strives to achieve a similar goal in his new home. Demonstrating intricate knowledge of the area, Waits is precise when denoting place in “Union Square.” In the song, Waits describes patrons walking out of a Cinema 14 around the corner from Union Square. If one references a map of New York City, one will find that there is, in fact, a Cinema 14 movie theater there. This specificity confirms Waits as a believable character in the city and provides another layer of realism, transporting the listener to Union Square. The more specific Waits can be about a location, the more accurately he can portray it, thus creating a very real setting for his music.

From top to bottom—San Clemente, Oceanside, San Diego, Napoleone’s Pizza House. Route 15 traced in purple

Waits also places himself in New York City musically with the instrumental track “Midtown.” Because there are no lyrics, the title is the only textual indication of where the song is placed. Over drums, an ostinato bass, and a big-band theme, horns sound in free-form solos in swooping dynamics and dissonant harmonies. With the title in mind, the cacophony of horns sound as re-creations of the Midtown traffic Waits was hearing in New York. In other words, Waits creates a musical and sonic portrait of New York traffic. This interpretation would not be possible without Waits’s title placing the sounds. The title gives the song context and, by extension, extramusical value.

While Waits often provides a specific location in his songs, the themes of the songs themselves allow for Waits to still be perceived as an “everyman.” This is an important factor in his success, as he would potentially only gain regional popularity and notoriety if he was established as a real character in only one area. Instead of limiting himself to a single region, Waits places himself in specific locations from coast to coast—from the busy streets of San Diego and New York to the empty stretch of highway between East St. Louis and Kansas City. At the same time, Waits portrays common themes regardless of where he is situated. The most common of these themes are longing and isolation. In a 1976 interview, Waits states, “There’s a common loneliness that just sprawls from coast to coast . . . it’s like a common disjointed identity crisis.”[21] So while Waits is aiming to effectively place himself in a city as a real character, he is also portraying themes that listeners can relate to across the United States—or even the world.

Analogous to how he displays his knowledge of the Southern California coast on “Diamonds on My Windshield” from The Heart of Saturday Night, Waits shows similar knowledge of the Australian landscape in “Town with No Cheer” from 1983’s Swordfishtrombones. Confirming the song’s place, Waits includes Australian terminology, referring to both the “Overlander” and the “Vic Rail” in the song.[22] Waits also makes passing reference to the immigrant weed Echium plantagineum by its local colloquial name, “Paterson’s curse.”[23] As it turns out, this song was generated from a newspaper article. Waits states in an interview that this song is “about a miserable old town in Australia that made the news when they shut down the only watering hole. We found an article about it in a newspaper when we were over there and hung onto it for a year.”[24] Given that the song is based on a newspaper article, it makes sense that Waits would try to preserve the realism of the location. However, the storyline of the song itself remains clear regardless of setting, allowing the central story and theme to be understood by anyone around the world. The realism of the song, provided by the location and local terminology, contributes to the relatability of the themes. If it were not for this realism, the story itself could be passed over as fantasy, and thus, the themes would be lost on the listener.

There are several recurring locations in Waits’s catalog. Interestingly, many of these places are set or referenced in a similar fashion each time, implying that they have an assigned affect. One of the most prominent examples of this is the state of Illinois, as mention of both the state and the towns within it are given similar treatment.[25] All these “Illinois songs” either are treated as love ballads or feature Illinois as the object of one’s longing. These treatments appear in Swordfishtrombones in the song “Shore Leave” and later in “Johnsburg, Illinois” from the same album. Waits most likely uses Illinois as an object of affection and longing because his wife was born there before moving to the East Coast. He takes his personal treatment of Illinois further, however, in 2004’s “Day after Tomorrow,” where he describes a soldier longing for his home in Rockford, Illinois.[26] So as a result of his personal, familial connection to the state, Illinois comes to represent a home, a family, and a place to long for across his catalog—not just songs about his wife.

Another recurring location is the intersection of Vine Street and Hollywood Boulevard in Los Angeles. This first appears on Blue Valentine (1978) in “A Sweet Little Bullet from a Pretty Blue Gun.” The intersection even serves as the title of 1980’s Heartattack and Vine.[27] “Sweet Little Bullet” goes on to mention the Gilbert Hotel, which lies three blocks from the intersection. Again, when using this level of specificity, Waits demonstrates that his locations are not chosen arbitrarily and provide more depth to the setting and the musical work. Both songs set at this intersection describe a scene filled with drugs, prostitution, and violence. This imagery is consistent with how other Hollywood residents would characterize this area at the time the songs were released.[28] While the intersection once housed some of the largest movie production companies in the ’20s, many moved away in the ’60s, and the area quickly degenerated.[29] It is of little surprise that Waits would adopt this area as a setting in his music—especially earlier in his career, when he was making an effort to seem degenerate himself. Waits sets both songs in an eight-bar blues form in a minor key accompanied by his vocal growl. These songs could be categorized as aligning with the Chicago urban blues style, given their instrumentation.[30] The accompaniment in these songs is unsurprising, as they thematically fit with the expectations of Chicago blues. Waits’s repeated thematic imagery, as well as his recurring musical accompaniment associated with this Hollywood intersection, indicates that he attaches a specific affect to this location.

Tom Waits: “I Wish I Was in New Orleans (In The Ninth Ward)”

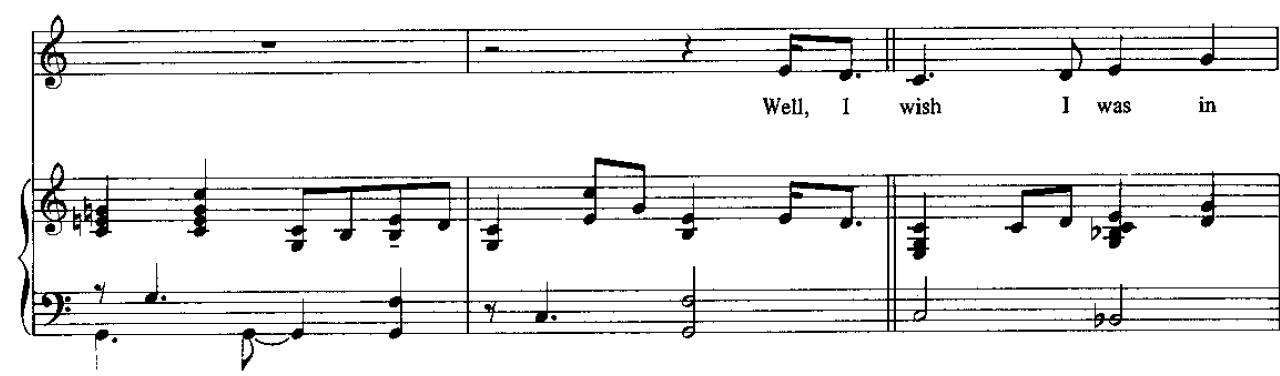

This song from 1976’s Small Change shows Waits dreaming of drunkenly stumbling through New Orleans’s Burgundy Street in the Ninth Ward. Drawing on New Orleans’s reputation as a hub for jazz, alcohol, and debauchery, Waits portrays his character as inebriated and, in doing so, illustrates the scene in New Orleans that he longs for.[31] This portrayal begins before the first note sounds; the recording begins with Waits counting in the band, but beats three and four are jumbled into unintelligible grunts rather than numbers (0:00–0:04). Mimicking physical stumbling, the vocal anacrusis in measure 8 seems to fall into the downbeat of the verse as it is juxtaposed against the equal quarter- and eighth-note rhythms of the introduction (Figure 3). This stumbling is portrayed throughout the song as the tempo slows at half cadences before “falling” back into the initial tempo with the arrival of the tonic.

Waits also vocally displays his character’s inebriation throughout the song. He slurs many of his words together, particularly at cadence points, and he often slides upward into the melody, beginning in measure 10 (Figure 4). Adding color to his slurs, Waits often substitutes the sound z into words that end with s, such as “Orleans,” “dreams,” and “beans.” He also uses improper grammar at points in the song, such as “What I wants is red beans and rice.”

Waits’s vocal line breaks the straight rhythm of the introduction as it stumbles into the verse. Transcription from Tom Waits: Anthology (1988).

Illustrating Waits as a wandering, drunk narrator, the final phrase of the A section needs to be extended by a measure of 2/4 as it approaches the cadence, highlighting the wandering and rambling nature of the narrator (Figure 5). Waits invokes the New Orleans jazz tradition at the close of the first iteration of the B section as he imagines hearing “that tenor saxophone callin’ [him] home,” accompanied by a prominent saxophone melody in the band.

Besides portraying drunkenness as a way of highlighting the scene that Waits is imagining in New Orleans, he also uses a harmonic technique that invokes the style of fellow songwriter Randy Newman and, by extension, Newman’s ties to New Orleans. Waits’s chromatic descent over a descending fifths progression mirrors the harmonic paradigm that Peter Winkler identifies in the 1988 article “Randy Newman’s Americana” (Figure 6a, b, c). While Winkler makes the connection between this harmonic paradigm and barbershop harmony, this progression can also be connected with the music of vaudeville (whose musical development happened concurrently with barbershop).[32]

Added measure of 2/4 at the cadence highlights Waits’s wandering. Transcription from Tom Waits: Anthology (1988).

Though often thought of a West Coast songwriter, Randy Newman spent many years of his childhood in New Orleans and has long celebrated the region and its music throughout his career.[33] In fact, his 1988 album Land of Dreams is composed of childhood vignettes from New Orleans.[34] It is perhaps not that much of a stretch to attribute this passing moment in “I Wish I Was in New Orleans” to Randy Newman’s style. While this song was composed in 1975, Waits began citing Randy Newman as an influence as early as 1974, describing him as “a craftsman when it comes to putting a song together.”[35] So while Waits draws on New Orleans’s reputation to musically portray his seedy character as a part of the city, he also borrows a brief but potent harmonic technique used by another songwriter who often celebrates New Orleans.

Bruce Springsteen

Much like Tom Waits’s early work, Bruce Springsteen’s early writing places him in his hometown. The title alone of Springsteen’s debut album, Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. (1973), labels him as a proud native and representative of the New York and New Jersey region. Of the twelve locations given over the course of the album, nine of them are in New York and New Jersey (Figure 7). Furthermore, the locations named outside of this area are not the focal points of the songs that contain them. Harvard and Zanzibar are mentioned in passing as part of the inner-rhyme, stream-of-consciousness writing that marks many of Springsteen’s earlier works, and Arkansas is used as a descriptor of the title character in “Mary Queen of Arkansas.”

In ways similar to Waits, Springsteen demonstrates knowledge of his location to establish himself as a real character from the region. In Greetings from Asbury Park, Springsteen is sure to mention streets and boroughs throughout New York City as well as more precise locations, such as Bellevue Hospital and the Hotel Chelsea. Both historic landmarks, these specific places are recognizable to residents of the city as well as others who know its neighborhoods. Naming these places in his songs effectively establishes Bruce Springsteen as a real character in this region.

Springsteen’s first five albums show him rarely leaving New York and New Jersey. In fact, his 1975 breakthrough album, Born to Run, never leaves this region. Instead, the album features the most instances of precise locations across his entire career. For example, “the Palace” that Springsteen mentions in the album’s title track is a reference to Palace Amusements, found on the Asbury Park Boardwalk. Mentions of precise places such as this put some frame of reference on more ambiguous locations included in the song; knowing that “the Palace” is on the boardwalk makes it easy to assume that “the beach” is along the Jersey Shore. While having knowledge of these locations might not have a significant effect on these songs’ meanings, they do effectively place Springsteen as a New Jersey native as well as add a layer of realism to the music, giving the narrative and themes a greater sense of relatability because they reflect reality.

It is not until Nebraska (1982) that Springsteen shows significant diversity in locations. Despite this diversity, New York and New Jersey still receive the most attention. This album also features the highest frequency of discrete locations at this point in Springsteen’s output. One reason for this increase might be the acoustic nature of the album, aligning it more closely to folk and country musical traditions, which are more likely to include place names than the rock tradition.[36] In other words, in order for Springsteen to convincingly write songs in the folk tradition, he needed to incorporate more discrete locations.

Even though the majority of locations that appear throughout Nebraska are found in the Northeast and the album itself was recorded in Springsteen’s New Jersey apartment, the title combined with the acoustic nature of the album primes listeners to hear and interpret the work through the lens of Middle America.[37] The emptiness of the lo-fi sonic landscape is brought out visually in the album cover, which shows the expanse of an open road presumably in Nebraska. Springsteen’s interpretation of Nebraska reflects his developing trend of focusing his songwriting efforts toward Middle, working-class America. Placing himself closer to this region and socioeconomic class will prove to be an important part of Springsteen’s music and persona throughout the rest of his career. Nebraska is also the last album in which Springsteen places his songs primarily in New York and New Jersey. After Nebraska, Springsteen instead focuses on the Rust Belt and the Southwest. This shift is easily seen when looking at the map of The Ghost of Tom Joad.

While Nebraska’s musical style and album art created the illusion of Middle America, The Ghost of Tom Joad signifies Springsteen’s actual shift to the American heartland as he further steeps himself in the American folk tradition.[38] Highlighting this shift, Springsteen incorporates forty discrete locations into The Ghost of Tom Joad, while his previous work averaged fourteen locations per album (Figure 8). Even more noticeable is that the majority of these locations are in California, showing a leap from the East Coast to the West. Once again, an explanation for the significant increase in places could be that Springsteen recognizes some of the lyric and musical characteristics of the folk style. The jump from one coast to another parallels Tom Waits’s move from the West Coast to the East, since both artists changed their location focus after moving across the country. More important, however, the primary theme that runs through the album is the plight of immigrants coming into the United States through Mexico. Highlighting this struggle, Springsteen looks toward border towns, such as those in Southern California. The second theme that runs through this album is that of America’s shrinking industrial cities. Highlighting this theme and Springsteen’s development as a working-class hero and a mouthpiece for factory workers, he frequently uses cities whose commerce and jobs have suffered as a direct result of factories shutting down Youngstown, Ohio, and Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania.

The song “Youngstown,” named for the historic Ohio steel-mill city, celebrates the history of factory towns and laments their decline. Singing a haunting minor-mode melody, Springsteen outlines the rise of the city and its importance in war efforts beginning with the Civil War through the conflict in Vietnam. Springsteen goes on to say that the Monongahela Valley, Mesabi iron range, and the coal mines of Appalachia have all suffered similar fates. The poignancy is highlighted by the realism found in the song, as the story is told from the viewpoint of a Youngstown, Ohio, native. Instead of broadly addressing the Rust Belt, Springsteen draws attention to the struggles of a single town in the first three verses of the song before applying these themes to factory towns as a whole in the last verse.[39] Choosing Youngstown as the setting for this song is appropriate because it was once the center of “Steel Valley” and was the founding site of Republic Steel, among other national steel organizations.[40] Since the ’60s, however, Youngstown has gone through economic turmoil with the downturn of steel production. Currently, it is one of the fastest-shrinking cities in the United States.[41] Youngstown’s drastic situation makes it an ideal setting for exposing the difficulties that these steel towns and their residents now face.

Springsteen’s primary international locations lie in Southeast Asia, specifically Vietnam. The first instance of this occurs on the album Born in the U.S.A. (1984).[42] At the time of its release, much of American media related to the conflict in Vietnam was centered on disturbed and potentially violent Vietnam veterans.[43] Instead of adhering to this stereotype, Springsteen writes about the struggle those veterans faced adjusting to life after serving in Vietnam on the album’s title track. Making the experience all the more potent, Springsteen’s narrator describes a brother who fought in Khe San, the site of a major battle in the conflict, and “had a woman in Saigon.” While Springsteen does not provide any further detail, his naming of these specific regions rather than generalizing with a simple country label brings a level of specificity and depth that gives the song more meaning. In other words, it creates a more reliable narrator, thus strengthening the song’s message.

Springsteen continues to use Vietnam as focal point in several political songs in The Ghost of Tom Joad. Creating a deeper sense of realism, Springsteen uses specific areas of Vietnam, such as Saigon, Quang Tri, and Chu Lai. Instead of connecting with veterans using the United States as common ground, Springsteen uses Vietnam. While these locations might not be widely known to the average American, they would resonate with soldiers stationed in Vietnam and, if nothing else, give Springsteen’s songs more depth and confirm him as an advocate for Vietnam veterans.

The Ghost of Tom Joad marks the point where Springsteen is invested in immigration reform and the lives of migrant workers from Mexico. Springsteen tries to place himself closer to the issues by creating narrators whose “[families are] from Guanajuato” or who know that “men in from Sinaloa were looking for some hands.” By making use of specific locations instead of simply stating “Mexico,” Springsteen places himself closer to the people that he is addressing or trying to emulate in his characters. This specificity implies a level of knowledge and accuracy in relation to immigration issues, again heightening the realism of the work and giving way to the notion that Springsteen is an advocate for immigrants’ rights. By depicting the struggles of both factory workers and immigrants, Springsteen confirms his persona as a workingman and advocate for the “American Dream.”

The albums that follow Tom Joad show a significant decrease in specific and meaningful locations.[44] For example, the only four locations mentioned in Magic (2007) occur in succession in “Terry’s Song” as Springsteen lists “wonders of the world.” While these places are recognizable worldwide, no single location in the song carries deeper musical value. Similarly, Springsteen employs a succession of locations in the song “We Take Care of Our Own” from Wrecking Ball (2012) by using easily recognizable landmarks to emphasize that, as a country, “we take care of our own.” This theme is made clearer with the repeated lyric “Wherever this flag is flown.”[45] In other words, while Springsteen uses specific locations in this song, they do not carry weight in regards to the musical meaning of the song because the location could simply be “wherever this flag is flown.” This recent downturn in locations is indicative of how Springsteen has chosen to represent himself and broaden his scope. He has moved from a hometown hero, to a working-class hero, to an advocate for immigrants, to a national icon.

Bruce Springsteen: “Born In The U.S.A.”

Whereas Tom Waits gives similar musical treatment to specific locations, Bruce Springsteen tends to use particular treatments with different regions and themes. Songs from New Jersey or addressing the United States as a whole tend to be aligned in the rock and folk-rock tradition, often backed by the E Street Band. This trend is partly a result of the band’s beginnings on the Jersey Shore, leading them to arrange songs from that region more in line with their musical associations there. At the same time, when addressing the nation, the large electric style is still preferred, given the anthemic sound produced from a larger band. These songs tend to treat America as a prized nation. Songs that take a more political or critical stance or relate a more personal story are more likely to be set acoustically. This music tends to be more personal and intimate, and the message or story tends to be more involved; thus a subdued arrangement is more suitable.

Springsteen is cognizant of these settings and their effectiveness as evidenced by his changing treatment of 1984’s “Born in the U.S.A.” When first released, the full band arrangement with the anthem-rock repetition of the chorus led to many misinterpretations. Springsteen’s lyrics depict a shell-shocked veteran who feels abandoned by his country after returning home from Vietnam. Washington Post columnist George Will, however, believed that Springsteen was celebrating America because “closed factories and other problems always [seem] punctuated by a grand, cheerful affirmation: ‘Born in the U.S.A.!’”[46] Perhaps even more memorable was Ronald Reagan’s comments at a 1984 rally in New Jersey, where he stated that “[America’s future] rests in the message of hope in the songs of a man so many young Americans admire—New Jersey’s own Bruce Springsteen.”[47] Had Reagan been familiar with the lyrics of “Born in the U.S.A.” (or almost any of the songs from Nebraska onward), he would not have labeled Springsteen’s songs as “messages of hope.”

This misinterpretation of the lyrics is easy to come by, given the arrangement of the song as it appears on the album in 1984. Behind synthesizers, guitars, and booming drums, Springsteen shouts the lyrics behind the bombastic accompaniment. The only lyric that can be consistently heard clearly is the repeated lyric “Born in the U.S.A.,” which is further highlighted by the synthesizer doubling the vocal line (Figure 9). Furthermore, this synthesizer line opens the piece and repeats incessantly throughout both the verses and the chorus, making the melody (and its accompanying lyric) the most salient characteristic of the song. This, combined with the inaudibility of the verse lyrics behind the band and Springsteen’s characteristically poor enunciation, makes it difficult to put the focus of the song on anything but the declarations of being born in the U.S.A.

Moving away from the album recording and subsequently shifting the focus of the song away from the title lyric, Springsteen has played “Born in the U.S.A.” acoustically with an almost blues-like slide guitar accompaniment since the midnineties.[48] This new arrangement features only Springsteen and the twelve-string acoustic guitar down-tuned to D-A-D-A-A-D. The result of this tuning combined with the additional strings doubling each pitch an octave higher is an open and initially modally ambiguous sonic field.[49] The accompaniment primarily consists of a whole-note harmonic rhythm with the chord struck once at the downbeat of each measure, creating a much sparser texture compared to the 1984 album recording. This texture points back to the folklike styling that Springsteen uses throughout Nebraska. In fact, Springsteen originally wrote the song to be included on that album before rearranging it for the 1984 album.[50] Springsteen’s intentions to include “Born in the U.S.A.” on Nebraska further indicate that the song’s themes perhaps fit better with Springsteen’s acoustic stylings over his band accompaniments.

While the verses of the album version are sung using the fifth as a reciting tone that only resolves down to tonic in the final measure, the newly arranged verses traverse down an octave, splitting the lines of the verse into being recited on tonic in the first half and on subdominant in the second half. This variety and larger range combined with the sparse accompaniment gives the melodic line a clear direction and makes the lyrics both more coherent and poignant, as the larger descent mirrors the despair that the narrator feels as he returns from the Vietnam War (Figure 10a, b). This motion and clarity places an emphasis on the lyrics and, by extension, Vietnam that does not exist in the album recording.

While the first iteration of the choral lyric is based on the contour of the chorus on the album version, the second iteration is once again set with a descending line (Figure 11). Moreover, the second iteration of the lyric features Springsteen scooping up into b^3 with the phrase “U.S.A.,” giving it an added minor-blues emphasis and, again, contradicting the notion that this song is celebrating the United States. Perhaps the strongest contrast between the two versions is that this chorus is sung a tenth lower than the album version—a far cry from the shouting that is displayed in the album. Springsteen also cuts down the declarations of the chorus from four times to two, shifting the focus of the song further away from the United States.

By arranging this song acoustically and aligning it more closely with the folk songs of Nebraska, Springsteen better conveys the meaning of the song. Springsteen achieves this by creating a sparser texture and a more directional melodic line that places heavier emphasis on the verses and by cutting repetitions of the chorus lyric. This emphasis on the verses highlights the protagonist’s struggles in postwar America, contradicting the nationalistic interpretations of the 1984 album version.

“Jersey Girl”: Crossover Between Waits and Springsteen

Tom Waits’s 1980 song “Jersey Girl” and Bruce Springsteen’s cover of it exemplifies how Waits and Springsteen use place to highlight aspects of their created personae. While Waits originally wrote and recorded the song, Bruce Springsteen has performed it more frequently and has even altered and added lyrics.[51] Whereas Waits opens the song stating that he has no interest in the “whores on Eighth Avenue,” Springsteen states disinterest in the “girls on Eighth Avenue.” Although a minor change, the implication is significant; Waits intentionally portrays himself as a lowlife in the city with knowledge of the sex industry in the song’s setting, while Springsteen—someone who is known as a celebrant of the region—chooses to appear more innocent.

Bruce Springsteen also adds a new verse to the song. In it, he speaks to his tired lover and proposes an evening out along the Jersey Shore. This proposition shows a shift in the focus of the song. Unlike the previous verses that have focused on the woman, Springsteen’s added verse focuses on New Jersey and describes it as a place for entertainment and love. In adding this Jersey-centric verse, Springsteen glorifies the region, confirming the persona that he created for himself in his first albums. In other words, Waits may have written the original song, but the sentiment of it combined with the added verse causes it to align more closely with the persona of Springsteen.

Conclusion

Both Tom Waits and Bruce Springsteen use locations to illustrate their persona and bring across themes in their music. In each of their earlier works, they use specificity to place themselves in a region and add realism to the songs. As they tour more extensively and write more music, more variety in their choice of location appears. Waits highlights themes that exist across the United States by depicting them in detail in a single location. At the same time, he chooses places that reflect the vagrant persona that he has chosen for himself. This persona and use of specific locations remains consistent through Waits’s career. Springsteen takes a similar approach to Waits in his use of specificity to highlight particular themes, particularly in issues regarding factory workers and immigration. However, while Waits remains true to a single theme and persona, Springsteen’s theme changes over the course of his career, and as a result, the locations that he chooses and how he uses them also change. As Springsteen moves from hometown hero to national icon, he shifts his focus from New Jersey to the Rust Belt to the West Coast and, finally, the nation at large. As a result, Springsteen uses fewer specific locations in this most recent phase, while Waits’s use remains consistent. Springsteen’s place at any time is more ambiguous and one that allows him to survey the country from any location, placing him as a resident on “Main St., USA.”

In either case, both artists use location to build their identities as an “everyman.” Recognizing that locations can carry meaning, both Springsteen and Waits choose their places carefully to best reflect the narrative of a particular song. Moreover, the inclusion of these places adds an element of realism to the music, giving the narratives and themes more power and immediate relevancy. More broadly, mapping and analyzing these songwriters’ uses of location gives us a better understanding of how they choose to compose music. Certain places have particular affects (seen in Illinois and the intersection of Hollywood Boulevard and Vine Street), and some places are more appropriate for given themes (such as in the Southwest and old industrial towns). While it is not always a central issue, location is a crucial element in many popular songs and should be taken into greater consideration as we strive to gain a clearer understanding of popular music. I hope that future research in this area will incorporate my interdisciplinary approach, because drawing from the fields of both music theory and musicology allows for a more holistic view of music. For this reason, an interdisciplinary approach such as this could also prove useful in the growing field of popular music education.

Notes

4. Deichmann notes, however, that many of these categories overlap and these categories do not represent an exhaustive list.

5. While this current study does not explicitly categorize the places in the manner that Deichmann does in his study, political, social, and romantic themes do still emerge.

7. Valania, 1999 (2011) p. 271.

8. Hayes (2009) examines many of these artists and includes an extensive discography of recordings that feature US cities and states from 1924 to 2006.

10. Gumprecht, 1998 p. 62; Susan Smith, 1994 p. 232.

11. As a result, many of these studies are regional, as they tend to focus on how a style is associated with a place purely because of the music’s or the artist’s origin. See Carney (1999) and Gumprecht (1998).

12. Connell and Gibson, 2003 p. 72.

13. As it turns out, several of the locations that Connell and Gibson state that artists would not write about are found in the catalogs of both songwriters used in this study.

14. While a case can be made that the lyricist’s opinions should matter less than those of the interpreter, I chose to restrict this study to songs performed by the original lyricist, as I believe it allows for stronger connections to be made between the location and the musical setting.

15. Everett (1975), Cullen (1997), Harde (2013), and Carroll (2011) all address these personas.

16. Nordström (2014) served as the jumping-off point for the Tom Waits map. It was thoroughly reviewed and inaccuracies were corrected.

17. See United States Census Bureau (2015) for visual representations of these population densities.

20. Perhaps not incidentally, Napoleone’s Pizza House is where Waits worked nights as a teenager (Wiseman, 1975).

21. Carter and Greenberg, 1976 p. 60.

22. The Overlander is an Australian railway, and VicRail is the organization that operates trains in that region.

23. Parsons and Cuthbertson, 1992 pp. 325–30.

25. Exceptions to this are Chicago and East St. Louis, which both have different affects.

26. Establishing his familiarity with the area, Waits mentions Rockford’s relative location to the Wisconsin border.

27. In the promotional materials for this album, Waits explains that he renamed Hollywood Boulevard as Heartattack Boulevard.

31. The book Louisiana: A Guide to the State claims that “New Orleans became noted both for its bawdiness as a river town and for its gaiety as cultural center” as early as the 1750s (American Guide Series, 1941 p. 320).

36. Connell and Gibson, 2003 p. 35.

37. Sufjan Stevens later achieved a similar effect with his abandoned Fifty States project, in which he set out to write an album for each state. After writing an album for Illinois and Michigan, Stevens abandoned the project and has since called it a promotional gimmick.

38. In fact, Ghost of Tom Joad won a Grammy Award in 1997 for Best Contemporary Folk Album.

39. This is perhaps comparable with Waits’s notion of finding common themes across the country that can be brought out in any one location.

42. Interestingly, the only mention of any domestic location on this album is the “U.S.A.” in the title track.

43. Chapter 4 of Masciotra (2010) outlines movies, music, and literature from 1977 to 1989 that conform to this stereotype.

44. The exception to this is 2005’s Devils and Dust, which marks a return to the acoustic nature of both Nebraska and Tom Joad and, unsurprisingly, features the highest number of specific locations among the albums that followed Tom Joad. In fact, several of the songs found on this album are from the Tom Joad era (Springsteen, 2005).

46. Cowie and Boehm, 2006; Will, 1984.

49. “Bruce Springsteen-Born In The USA (acoustic),” YouTube video, 3:05, from a performance televised on Música Sí on December 14, 1998, posted by “bruchee,” December 14, 2006, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=d8TwMqpBeL4.

51. Setlist.fm, 2015.

References

- Abram, David. 1997. The Spell of the Sensuous: Perception and Language in a More-than-Human World. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Alterman, Eric. 1999. It Ain’t No Sin to Be Glad You’re Alive: The Promise of Bruce Springsteen. Boston: Little, Brown.

- American Guide Series. 1941. Louisiana: A Guide to the State. New York: Hastings House.

- Brackett, David. 2000. Interpreting Popular Music. Berkeley: University of California Press.

- Brackett, Donald. 2008. Dark Mirror: The Pathology of the Singer-Songwriter. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Carney, George. 1999. “Cowabunga! Surfer Rock and the Five Themes of Geography.” Popular Music and Society 23 (4): 3–29.

- Carroll, Cath. 2000. Tom Waits. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press.

- Carter, Betsy, and Peter Greenberg. (1976) 2011. “Waits on Being the Voice of Everyman.” Reprinted in Tom Waits on Tom Waits: Interviews and Encounters, edited by Paul Maher, 60. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Cavicchi, Daniel. 1998. Tramps like Us: Music and Meaning among Springsteen Fans. New York: Oxford University Press.

- Coles, Robert. 2003. Bruce Springsteen’s America: The People Listening, a Poet Singing. New York: Random House.

- Connell, John, and Chris Gibson. 2003. Sound Tracks: Popular Music, Identity, and Place. New York: Routledge.

- Cowie, Jefferson, and Lauren Boehm. 2006. “Dead Man’s Town: ‘Born in the U.S.S.,’ Social History, and Working-Class Identity.” American Quarterly 58 (2): 353–78.

- Cresswell, Tim. 2015. Introduction to Place: An Introduction. Hoboken: Wiley-Blackwell.

- Cullen, Jim. 1997. Born in the U.S.A.: Bruce Springsteen and the American Tradition. New York: Harper Collins.

- Deichmann, Joel. 2015. “‘Miami, New Orleans, London, Belfast, and Berlin’: An Analysis of Geographic References in U2’s Recordings.” Rock Music Studies 2 (2): 103–24.

- Dolan, Marc. 2012. Bruce Springsteen and the Promise of Rock ‘N’ Roll. New York: W. W. Norton.

- ———. 2014 “How Ronald Reagan Changed Bruce Springsteen’s Politics.” Politico. Accessed December 29, 2016. http://www.politico.com/magazine/story/2014/06/bruce-springsteen-ronald-reagan-107448.

- Everett, Todd. 1975. “Tom Waits: In Close Touch with the Streets.” Los Angeles Free Press, October 17–23. Also Printed in New Musical Express, November 29, 1975.

- Everett, Walter. 2007. “Beyond the Palace: Casing the Promised Land.” Interdisciplinary Literary Studies 9 (1): 81–94.

- Griffiths, Dai. 2003. “From Lyrics to Anti-lyric: Analyzing the Words in Pop Song.” In Analyzing Popular Music, edited by Allan F. Moore, 39–59. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

- Gumprecht, Blake. 1998. “Lubbock on Everything: The Evocation of Place in Popular Music (a West Texas Example).” Journal of Cultural Geography 18: 61–81.

- Guterman, Jimmy. 2005. Runaway American Dream: Listening to Bruce Springsteen. Cambridge, MA: Da Capo Press.

- Harde, Roxanne. 2013. “‘Living in Your American Skin’: Bruce Springsteen and the Possibility of Politics.” Canadian Review of American Studies 43 (1): 125–44.

- Harde, Roxanne, and Irwin Streight. 2010. Reading the Boss: Interdisciplinary Approaches to the Works of Bruce Springsteen. Lanham, MD: Lexington Books.

- Hayes, David. 2009. “‘From New York to L.A.’: US Geography in Popular Music.” Popular Music and Society 32 (1): 87–106.

- “Jersey Girl by Tom Waits Song Statistics.” Setlist.fm. Accessed February 2015. http://www.setlist.fm/stats/songs/tom-waits-3bd6c0ac.html?song=Jersey+Girl.

- Kirkpatrick, Rob. 2009. Magic in the Night: The Words and Music of Bruce Springsteen. New York: St. Martin’s Griffin.

- Larman, Howard. (1974) 2011. “Interview with Tom Waits.” Reprinted in Tom Waits on Tom Waits: Interviews and Encounters, edited by Paul Maher, 20–26. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Lovett, Lyle. 2015. Interview by Jacob Arthur, October 17.

- Malpas, Jeff. 2010. “Place Research Network.” Progressive Geographies, November 4. Accessed June 7, 2015. https://progressivegeographies.com/2010/11/04/place-research-network/.

- Marsh, Dave. 1996. The Bruce Springsteen Story. New York: Thunder’s Mouth Press.

- Masciotra, David. 2010. Working on a Dream: The Progressive Political Vision of Bruce Springsteen. New York: Continuum.

- Montandon, Mac. 2005. Innocent When You Dream: The Tom Waits Reader. New York: Thunder Mouth’s Press.

- Moore, Allan F. 2012. Song Means: Analysing and Interpreting Recorded Popular Song. Burlington: Ashgate.

- Nordström, Jonas. 2014. “Tom Waits Map.” http://tomwaitsmap.com/.

- Oliver, Paul. “Blues.” Oxford Music Online. Accessed October 9, 2015. http://www.oxfordmusiconline.com.ezp1.lib.umn.edu/subscriber/article/grove/music/03311.

- Parsons, W., and E. Cuthbertson. 1992. Noxious Weeds of Australia. Melbourne, Australia: Inkata Press.

- Poole, Bob. 2008. “Turning the Corner at Hollywood and Vine.” LA Times, May 4.

- Posey, Sean. 2013. “America’s Fastest Shrinking City.” The Hampton Institution. Accessed May 28, 2015. http://www.hamptoninstitution.org/youngstown.html.

- Smith, Larry. 2002. Bob Dylan, Bruce Springsteen, and American Song. Westport, CT: Praeger.

- Smith, Susan J. 1994. “Soundscape.” Area 26: 232–40.

- United States Census Bureau. 2015. “Thematic Maps.” Accessed February 2015. https://www.census.gov/geo/maps-data/maps/thematic.html.

- Valania, Jonathan. (1999) 2011. “The Man Who Howled Wolf.” Reprinted in Tom Waits on Tom Waits: Interviews and Encounters, edited by Paul Maher, 263–77. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Waits, Tom. 1988. Anthology 1973–1982. New York: Amsco.

- ———. 2007. The Early Years: The Lyrics of Tom Waits (1971–1982). New York: Ecco.

- ———. (1983) 2011. “A Conversation with Tom Waits.” Reprinted in Tom Waits on Tom Waits: Interviews and Encounters, edited by Paul Maher, 130–36. Chicago: Chicago Review Press.

- Werner, Craig. 1998. A Change Is Gonna Come: Music, Race & the Soul of America. New York: Plume.

- Will, George. 1984. “Bruce Springsteen, U.S.A.” Washington Post, September 13, A19.

- Winkler, Peter. 1988. “Randy Newman’s Americana.” Popular Music 7 (1): 1–26.

- Wiseman, Rich. 1975. “Tom Waits, All-Night Rambler.” Rolling Stone, January 30. http://www.rollingstone.com/music/news/tom-waits-all-night-rambler-19750130.

Albums

- Springsteen, Bruce. 1973. Greetings from Asbury Park, N.J. Columbia Records. PC 31903, compact disc.

- ———. 1973. The Wild, the Innocent & the E Street Shuffle. Columbia Records. PC 32432, compact disc.

- ———. 1975. Born to Run. Columbia Records. PC 33795, compact disc.

- ———. 1978. Darkness on the Edge of Town. Columbia Records. OC 509876, compact disc.

- ———. 1980. The River. Columbia Records. PC 38654, compact disc.

- ———. 1982. Nebraska. Columbia Records. QC 38358, compact disc.

- ———. 1984. Born in the U.S.A. Columbia Records. QC 38653, compact disc.

- ———. 1987. Tunnel of Love. Columbia Records. OC 40999, compact disc.

- ———. 1992. Human Touch. Columbia Records. COL 657872 7, compact disc.

- ———. 1992. Lucky Town. Columbia Records. CK 53001, compact disc.

- ———. 1995. The Ghost of Tom Joad. Columbia Records. COL 481650 2, compact disc.

- ———. 2002. The Rising. Columbia Records. COL 504190, compact disc.

- ———. 2005. Devils and Dust. Columbia Records. CN 93900, compact disc.

- ———. 2007. Magic. Columbia Records. COL 88697 17060, compact disc.

- ———. 2009. Working on a Dream. Columbia Records. COL 741355, compact disc.

- ———. 2012. Wrecking Ball. Columbia Records. COL 88691942541, compact disc.

- ———. 2014. High Hopes. Columbia Records, compact disc.

- Stevens, Sufjan. 2003. Michigan. Asthmatic Kitty Records. AKR 007, compact disc.

- Waits, Tom. 1973. Closing Time. Asylum Records. AS 53 030, compact disc.

- ———. 1974. The Heart of Saturday Night. Asylum Records. AS 53 035, compact disc.

- ———. 1976. Small Change. Asylum Records. AS 53 050, compact disc.

- ———. 1977. Foreign Affairs. Asylum Records. AS 53 068, compact disc.

- ———. 1978. Blue Valentine. Asylum Records. AS 53 088, compact disc.

- ———. 1980. Heartattack and Vine. Asylum Records. AS 52 252, compact disc.

- ———. 1983. Swordfishtrombones. Island Records. IS 90095, compact disc.

- ———. 1985. Rain Dogs. Island Records. IS 90299, compact disc.

- ———. 1987. Franks Wild Years. Island Records. IS 90572, compact disc.

- ———. 1992. Bone Machine. Island Records. IS 512 580, compact disc.

- ———. 1999. Mule Variations. ANTI-Records. AN 86547, compact disc.

- ———. 2004. Real Gone. ANTI-Records. AN 86678, compact disc.

- ———. 2011. Bad as Me. ANTI-Records. AN 87151, compact disc.