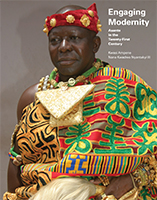

Engaging Modernity: Asante in the Twenty-First Century

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

Engaging Modernity

The rationale for choosing Engaging Modernity as the framing title for a book on the over three hundred years of the tangible and intangible heritage of the Asantehene’s regalia is informed by the vision, ideals, and values that have occupied His Majesty, Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II, for the past seventeen years. As the sixteenth occupant of the Gold Stool, Otumfoɔ began his reign on April 26, 1999, with a deep sense of commitment to engage the challenges of our times. The challenges, as identified by His Majesty, are education, health, poverty, conflict resolution and capacity building for traditional leaders. By focusing on and making these five critical needs the centerpiece of his reign, Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II converted the “weapons of war [of his forebears] into instruments of development” (SKB Asante, 2012: 1102). Otumfoɔ has been consistent in advising his chiefs and queen mothers that, “chiefs do not go to war these days” and that the wars they are required to fight and win convincingly are “wars against illiteracy, disease, and poverty.” In order to appreciate the larger historical context that lead to the above statements by His Majesty, it will be helpful to briefly examine the precarious position of chiefs and queen mothers in Ghana. Although the institution of chieftaincy is guaranteed in the 1992 constitution that ushered in democratic governance after a relatively long period of military dictatorships in Ghana, the executive and judicial powers of chiefs are fundamentally undermined by the educated elite. But the role of chiefs in post-colonial Ghana is multifaceted. Chiefs combine “executive, legislative, judicial, military, economic, and religious roles” with increasing expectations for the “transparent management of local resources for development and pre-occupation with the quality of life of the people over whom they exercise customary jurisdiction” (Odotei and Awedoba, 2006: 11). Despite the limited executive and judicial powers of chiefs in the current dispensation of democratic governance in Ghana, Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II used his “ingenuity, diplomacy, power of motivation, and his own personal resources to establish socio-economic programs” to complement the efforts of central government (Keynote Speech, Addis Ababa, 2004: 7). According to Otumfoɔ, chiefs and queen mothers are faced with the dualism of the radically divergent living standards of the relatively small number of urban dwellers versus the vast majority of populations living in rural and deprived communities. Since this dualism poses extraordinary challenges to integrated national development and the equitable and sustainable distribution of resources, it is the moral duty of chiefs and queen mothers to step up the task of bridging the two sides. According to Otumfoɔ, as chiefs, they have “a duty to partner the governments of our time to bring solace to those members of our society who suffer wretched conditions of life and who daily find it difficult to meet their barest basic needs” (2012 Royal Diary). In order to accomplish his vision, Otumfoɔ has created foundations within the Asante Kingdom that benefit communities and individuals throughout Ghana. The success of the Otumfuo Charitable Foundation has set a new benchmark for chiefs and the institution of chieftaincy in Ghana in particular, and Africa in general. Before presenting a brief overview of a selected list of development projects, I would like to make a brief comment on the concept of modernity and its application by the Asantehene.

In the multi-authored Readings in Modernity in Africa, Peter Geschiere et al. discuss at length the potential dilemmas, intellectual paradoxes, and pitfalls embedded in the linear social theory that propels the concept of modernity in Africa (2008). Modernity is defined by categories such as contemporary, the present, the now, or more broadly, a sense of living in a new time (Peter Geschiere et al. 2008: 2). Although the notion of modernity calls to mind innovation and advancement, in post-colonial Africa it presents a set of contradictions and is emblematic of a top-down or north-south approach where Europe and the West are placed at the apex of a socioeconomic ladder that transfers its “advanced” cosmopolitan modernity to “underdeveloped” societies mired in tradition. This top-down approach is lineal and unidirectional and negates considerations for a mutually beneficial two-way partnership. However, as will be evident in the following paragraphs, the modernity envisioned, planned and executed by Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II provides a second alternative, a center-out approach that is lateral and multidirectional in so far as it originates from within. As a king, he lives and interacts with his people on a daily basis and as a result, is in tune with the needs and challenges of the local environment, in addition to understanding the dynamics of different groups sharing a locality. Furthermore, he is better suited to understand the requisite expertise needed to satisfy those needs and in the process contribute significantly to poverty alleviation and reduction. The center-out, multidimensional approach takes us away from the mythic definition of tradition as ‘static’ and backward or normatively consistent, and consequently, antithetical to innovation. Rather, Otumfoɔ’s conception of modernity not only recognizes tradition as the foundation of development programs, but also balances the best of tradition with that of modernity for development administration. In his keynote address at the Norwegian-African Business Summit in Oslo, Norway (October 12, 2012), His Majesty cautioned participants not to abandon “our culture and traditions and surrender to everything foreign.” He went on to say that, “understanding our past and our culture which identifies us as a people is important for our self-confidence and that self-confidence is an indispensible prerequisite for our survival in the challenging new era” (ibid, 2013). For those familiar with the trajectory of over three hundred years of Asante history, tradition has never been static. Tradition has persistently been dynamic in all aspects of Asante life including the temporal dimension of modernity. For example, by uniting previously independent Akan states in the seventeenth century and defeating their overlord in 1701 (the powerful Denkyira Kingdom), Ɔpemsoɔ Osei Tutu accomplished a feat that was modern for his time. Similarly, the complex regalia items that form the basis of this book were either acquired in war or created over time by each succeeding Asante king to the extent that each addition was by and in itself a creative response to modern issues of the time. For the Asante, the only way to live in the twenty-first century and beyond is to constantly transform and adapt to the inevitability of change, that is, by making tradition relevant to modern-day realities.

In the shadows of any consideration of modernity is what Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II refers to as the “galloping wheels of globalization (2012 Royal Diary). In order to comprehend the resistance to globalization among indigenous cultures worldwide, a quote from His Majesty’s address at the 2005 Millennium Excellence Awards in Accra, Ghana may prove instructive. According to Otumfoɔ, “almost imperceptibly, we are all being led to belong to a global village when we do not know which part of the village we will occupy.” There are several sides to globalization but generally, integration of economic, financial, trade, and communications across national frontiers is the source of great concern for traditional leaders as evidenced in the two statements above by Otumfoɔ. At best, globalization leads to power shifts and consolidates Euro-American hegemony by prioritizing homogeneity over heterogeneity. For post-colonial societies in Africa who are still grappling with tensions, the resultant violence and the catastrophic loss of human lives, the memory of shifting ethnic boundaries to create new nation states is a painful one. For the homogenous element in globalization displaces the ontology of the vast majority of indigenous societies around the world. Once they are morphed into the “global village,” they lose the right to name or control their existence. Such is the predicament of chiefs and queen mothers in Ghana. Without executive or judicial powers, they are made to depend on the central government to provide social services including education, health, and development projects that will lift the masses from poverty. However, the over burdened central government cannot fully accomodate the needs of the masses. Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II responded to the conditions in his kingdom by creating development programs to complement the work of the central government. Let us now turn our attention to the four areas that Otumfoɔ has actively supported for fifteen years: education, health, conflict resolution, and his work with the World Bank.

Education

On November 13, 1999, barely six months after ascending the Gold Stool, the Asantehene inaugurated the Otumfuo Education Fund to redress the downward spiral of educational standards in Asante in particular, and in Ghana as a whole. With the exponential growth and success of his intervention strategies, Otumfoɔ saw the need to consolidate ongoing projects under a single umbrella. Subsequently, on April 25th, 2009, he created The Otumfuo Osei Tutu II Charity Foundation at the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST). As executive director of the foundation, Dr. Thomas Agyarko-Poku is responsible for overseeing and coordinating various initiatives in line with Otumfoɔ’s vision. Addressing the Second Annual Career Counseling in Kumase on December 2, 2013, Nana Brefo-Boateng, executive secretary of the Otumfuo Education Fund, announced that over four thousand brilliant but needy students in the basic, senior high, and tertiary institutions throughout Ghana have benefitted from scholarships. Under current projections, it is estimated that nine thousand students will benefit from scholarships by the end of 2014. Additionally, the fund is supporting eight students to pursue undergraduate and graduate degrees in the United States of America. Over one hundred and fifty high schools have profited from new infrastructural programs including the renovation of dormitories and classrooms, delivery of new furniture, and the provision of water tanks. Further, the foundation has built bungalows that are fitted with solar powered devices for teachers in rural and deprived areas. They have donated computers, books, and school uniforms to schools in rural and suburban areas. Some of the beneficiary institutions include the Ada Secondary School, Wiawso Secondary School, Jachie Pramso Secondary School, Afua Kobi Secondary School, Nchiraa Cluster of Schools, and Kumase Wesley Girls High School, to name a few. The foundation also places emphasis on the education of girls. The Trabuom Secondary has been transformed into a model girls school and renamed Afua Kobi Senior High School in honor of the Asante queen mother. Career guidance and counseling is lacking in secondary and tertiary institutions and it is encouraging that the foundation has organized two schools in 2012 and 2013 for close to ten thousand high school students. In 2012, participating students were drawn from selected schools in the Asante, Brong Ahafo, and Eastern Region of Ghana.

One of the contributing factors that led to the decline in educational standards was the lack of qualified teachers in underserved and deprived rural areas in Ghana. In order to complement the efforts of the central government, His Majesty created the Otumfuo’s Teachers and Educational Workers Award in 2011 to provide incentive packages to derserving teachers. Now in its fourth year, four hundred and fifty teachers have benefitted from the award. According to the Asantehene, Ghana owes a great deal of honor to teachers and other professionals who sacrifice the pleasure of living in urban communities to serve in deprived rural communities. Information communication technologies is prominent in the undertakings of the foundation and there are various initiatives that will make ICT fairly accessible to local communities. Two examples are the Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II Institute for Advanced ICT Training located at Ahensan, Kumase and the Lady Julia Community Knowledge Center, which was established by the Otumfuo Charity Foundation in partnership with Vital Capital Fund, AppleSeeds Academy, TechAide, Google and Vodafone. The first of their kind in Ghana, they are located in Suame, in the Ashanti Region, and Kenyasi, in the Brong Ahafo Region. In an unprecedented move, the University of Professional Studies, Accra, has created an academic unit, the Otumfuo Osei Tutu II Center for Traditional Leadership and appointed His Majesty as the first chair of the center. As a mark of his commitment to education, the Asantehene has donated GHC100, 000 (one hundred thousand Ghana cedis) towards an endowed chair for the center.

Health

In 2001, His Majesty proposed the Asanteman Health Fund and later in 2003, he formally inaugurated the Otumfuo Health Fund with Dr. Thomas Agyarko-Poku as the executive director. The health committee worked closely with the regional and metropolitan medical teams to combat infant mortality, reduce the incidence of glaucoma and other eye diseases, and worked to eradicate buruli ulcer, guinea worm and other water-borne diseases. As indicated on the Otumfuo Charity Foundation’s website, the goals of the Asantehene are to enhance access to good quality and sustained healthcare services for vulnerable populations, reduce infant and maternal mortality rates, and to control the spread of HIV/AIDS, malaria and other diseases (www.otumfuo-charityfoundation.org). In line with his laudable vision, the charity foundation has set up several initiatives spearheaded by Lady Julia Osei Tutu, Otumfoɔ’s wife. One of the health initiatives include the Serwaa Ampem Aids Foundation for children who have become victims of the HIV/AIDS pandemic. The Otumfuo Mobile Dental Outreach Program, a partnership with the Smiles for Everyone Foundation, USA, is one of the success stories of the charity foundation. On October 17, 2013, more than two thousand school children at Pakyi No. 2 near Kumase were screened for tooth extractions, scaling, and polishing.

Conflict Resolution

Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II recognizes the importance of peace and stability for development and good governance. Consequently, he has taken his judicial role seriously and encouraged his people to seek the path of arbitration instead of litigation and lobbied the central government to relocate hundreds of unresolved land and succession disputes from the judicial courts to his court. The cases involve land disputes, property and succession claims, inheritance, destoolment of chiefs, as well as criminal and civil cases. Once the modern court system transferred the above-named cases to the Asantehene, he used the age-old tradition of arbitration to settle over five hundred cases in a record five years and to date, over one thousand cases have been resolved (see for example, Otumfoɔ’s speech delivered at the 2nd Bonn Conference on International Development Policy, August 12, 2009). In achieving unparalleled successes in conflict resolution, Otumfoɔ introduced two critical elements of modernity that have been his trademark, namely (1) video recording of arbitration proceedings and (2) instead of having heads of the various divisions in Asanteman speak on behalf of each division, Otumfoɔ has directed that any paramount chief in a division can express their views if they so desire (Kojo Yankah, 2009: 46). A video archive of the Asantehene’s traditional court proceedings as well as ceremonies have been created as part of His Majesty’s office complex at Manhyia Palace. In his keynote address at the Fourth African Development Forum in Addis Ababa, Ethiopia, he reported that, “peace has returned to communities whose development was halted” due to unresolved conflicts and that, “families have been re-united in several instances (Addis Ababa, 2004: 11). The people did not fail to see the vision and wisdom in his judgments and now refer to Otumfoɔ as King Solomon and Osei Tutu Ababio (Osei Tutu has come again/returned) respectively. It is worth noting that Otumfoɔ’s success in conflict resolution is not limited to the Asante Kingdom as he has lent his services to volatile disputes in Northern Ghana and Sierra Leone.

Promoting Partnerships with Traditional Authorities Project

In no time, the resourcefulness of Otumfoɔ’s development programs in education, health, poverty alleviation, and conflict resolution caught the attention of local and international observers in Ghana, Africa, and abroad. In 2001, the World Bank, through its Africa Regional Office, declared its intention to begin a pilot project in selected communities in partnership with the Asantehene. In 2003, the World Bank was the first to extend a $4.5 million dollar grant, through the government of Ghana, to Otumfoɔ (see www.worldbank.org). The first of its kind in Africa, the World Bank program is known as Promoting Partnership with Traditional Authorities Project (PPTAP). As a three year pilot program, the PPTAP expanded existing programs in education, health, and capacity building for chiefs and greatly enhanced infrastructure upgrades in schools, built sanitation facilities in forty-one communities, developed health education modules for traditional authorities to lead in awareness of HIV/AIDS, built management capacity of chiefs, and assisted with transforming traditional values and culture. Ever mindful of involving traditional authorities in development administration, the Asantehene made sure that chiefs and heads of villages were critical in identifying projects in their locales as well as actively leading in the execution of projects.

Numerous private businesses and individuals have made financial contributions to the Otumfuo Education and Health Fund is fairly extensive to list here. Educational institutions, nations, and world bodies in Ghana, Africa, and abroad have recognized and conferred honors to Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu. Remarkably, His Majesty has been the Chancellor of the Kwame Nkrumah University of Science and Technology (KNUST) in Kumase since 2006. A partial list of his recognitions and awards include:

- University of Professional Studies Accra Honorary Doctorate Degree (Ghana, December, 2013)

- National Commission for Civic Education (NCCE), Annual Democracy Lecture (Ghana, May 17, 2013)

- Harvard University USA, Annual Distinguished Africans Lecture (November 3, 2005)

- London Metropolitan University–UK, Honorary Doctorate Degree (December 3, 2007)

- Association of Commonwealth Universities, Paul Symons Award for Excellence, (2000)

- Addressed the Conference on “The Challenges of Change-African German Resources,” organized by the President of the Federal Republic of Germany at the Eberbach Monastery Conference Center, Rheingam, Germany (November 3rd, 2007)

- University of Ghana, Honorary Doctorate Degree (March 12, 2004)

- Keynote Speaker for a Plenary Session of the Economic Commission for Africa, Addis Ababa, Ethiopia (October 2004)

- Nigeria – Guest Speaker at the Osiguwe-Anyiam Foundation Annual Lecture (November 2005)

From the foregoing discussion, it is fair to conclude that Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu has made Asante cultural values and traditional governance relevant to the challenges of the twenty-first century. His unwavering commitment to raising the standards of education, finding solutions to health problems, his strategies for poverty alleviation, his advocacy for arbitration instead of litigation, and capacity building for chiefs in Ghana are commendable. This is what led Dr. Sir Kwame Donkoh Fordwor to state that among others, “Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II has established a concept of kingship that is more suited to the spirit of the new and changed conditions of today” (Yankan 2009). By identifying areas of need in consultation with his chiefs and making sure that local chiefs are deeply involved with the delivery of services, Otumfoɔ espouses a center-out, multi-directional approach to modernity. In all these, unity of the different ethnic groups in Ghana is uppermost in his interactions with his fraternity of chiefs. He does not limit beneficiary communities and individual awards to his kingdom but also extends benefits to other regions in Ghana. Ultimately, Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II has established a solid foundation to position Asanteman in the twenty first century by strategically transforming traditional kingship in a rapidly changing world.

In June 2009, Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II commissioned the Manhyia Project with Professor Kwasi Ampene (University of Michigan, USA) as the director and Nana Kwadwo Nyantakyi III (Asantehene Sanaahene) as the presiding chief. For a project seeking access to the oral histories of centuries-old regalia so that these histories might be “frozen” in written form, the king made the conscious decision to extend his notion of modernity to the expressive cultures of Asanteman. He articulated his vision in his 2004 speech during the Asanteman Adaekɛseɛ. According to Otumfoɔ, “we live in an age where oral tradition is fast becoming problematic,” and even, “the written word has limitations if it is not well-stored” (Adaekɛseɛ speech, May 9, 2004). The problem that His Majesty alludes to is the unique situation courtiers and custodians find themselves in as they are exposed to a western formal education and come into contact with the technology and devices of the information age. The capacity to memorize over five hundred years of history becomes daunting in such circumstances. In addition, we have begun to observe gaps where acute generational disparity exists compounded the older generation passing on without adequately transmitting the oral history of regalia objects to the younger generation. The present project is in response to the above noted needs. Further, this project is an essential first step in establishing the content for a proposed twenty first century museum and exhibition program in Kumase in the near future. Undoubtedly, the proposed museum will not only advance scholarly engagement and introduce educational opportunities for local students, but will also provide an unparalleled destination for both Ghanaian and foreign visitors to Kumase.

It is widely acknowledged that the regalia of the Asantehene are arguably the largest, most complex, best preserved and historically anchored of all Akan paramount chiefs. Due to my teaching schedule at the University of Michigan, we were able to work only in the summer months. We have been working consistently for seven years (from 2009-2016), but the work is far from over. So far, we have documented about eighty percent of the royal regalia. Apart from tipre ne amoakwa ne nkrawoben, and the queen mother, Nana Afia Kobi Serwaa Ampem II, presiding over the Asantehene’s kete, we are yet to document regalia objects in the Asantehemaa’s court. All of the regalia items exist under the custodianship and protection of Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II. While the royal arts of many West African traditional states have been dispersed to museums and collectors around the world, the regalia of the Asantehene are among the very few that remain intact. We made the above statement with full knowledge of instances of major gaps. For example, the looting of Kumase in 1874 by British colonial forces was led by General Garnet Wolseley and more looting occured when Asantehene Agyemang Prempeh was taken to exile from 1896-1924. The present work seeks to expand the pioneering work of A. A. Y. Kyerematen in the 1960s and 1970s. With the full blessing of Otumfoɔ Sir Osei Agyemang Prempeh II, Kyerematen published Regalia for an Asante Durbar (1961), his Oxford University doctoral dissertation; Ashanti Royal Regalia: Their History and Functions (1966); and several valuable pamphlets. It is noteworthy that some of the outcomes of Kyerematen’s research include the creation of an enduring cultural institution, the Center for National Culture (CNC, formerly Kumase Cultural Center) in Kumase, and the establishment of the Prempeh II Jubilee Museum as part of the CNC.

In addition to publications by Kyerematen, there are publications that have attempted to extensively document the Asante royal arts, however, they are far from comprehensive and most contain a significant number of errors that have been replicated in several publications over the years. Our goal for this project is to correct recurring inaccuracies and errors in both the oral and written history of the Asantehene’s royal regalia. As it became clear during the seven years that we gathered information, several custodians credit Ɔpemsoɔ Osei Tutu with the creation of the vast majority of regalia. It seems the mere mention of Osei Tutu elevates particular regalia and gives the objects special status. Consequently, it has become crucial for us to produce the urtext; a definitive history of all regalia items. For our methodology, and in order to present the human agency behind the complex heritage of regalia, we include the pictures and names of custodians (many of whom are chiefs of identifiable regalia), their family members, and elders. Despite including pictures and names of custodians, we steered away from succession history as we narrowed our focus to specific questions of (1) how did this come about? and (2) what happened/what was the impetus or historical incident that caused the creation of a particular item? To establish dates, we framed our questions in the following ways: Who created your regalia? Do you recall the name of the king that it was designed for? Who was the reigning king? Having established the historical context, we shifted our conversations to a wide range of issues, including the materials used, the embodied metalanguage, the symbolic meaning, how particular regalia interface with other regalia, the position of regalia in processions, to name a few.

One of the most potent regalia, Sikadwa Kofi (the Gold Stool) also referred to by its praise name, Abɛnwa, embodies the soul, the identity, the strength, and power of the Asante Kingdom. According to A. A. Y Kyerematen, the Abɛnwa is a mass of solid gold (1966). Due to the ever presence of gold ornaments, Asante is commonly known as the Kingdom of Gold. Even the dominant color in the well-known Asante Kente cloth is gold. What is not well known is that apart from the Gold Stool, the extensive use of gold in Asante did not originate in Ɔpemsoɔ Osei Tutu’s reign. In the early days of the kingdom, most of the gold cast symbols on regalia were made of the body parts of animals, birds, creepers, leafs, twigs and other organic materials. Asantehene Opoku Ware’s asked his craftsmen to replace these materials with gold. Accordong to oral history, King Opoku Ware was obsessed with gold and wanted an entire cloth made of gold. Upon completion, the courtiers could not lift up the flattened gold “cloth” and it was virtually impossible to wrap the cloth around anything. As a result, King Opoku Ware instructed the courtiers to cut it into pieces and convert the pieces into gold leaf to cover the regalia or make replicas of animals and bird parts, leafs and twigs from the gold.

Far from being relics of the past, the regalia items in this book have discernible historical significance as they continue to play a vital role in defining and sustaining Asante identity in our pluralistic society. That the Gold Stool is the quintessence of that history is evident from the numerous references to it in the proceeding chapters in this book. Long without written documents as historical records, the Asante have used these items of regalia, verbal art forms, and court music as records of their history. It is particularly significant that in what was a pre-literate society until the late nineteeth century, historical events were codified in various items of regalia. In addition to referencing over three hundred years of Asante history and culture, the collection is an expanding document of that history with successive kings adding new items to the regalia. Collectively, the regalia symbolize royal power. They are considered to be the collective property of the Asante state, not the sole property of the reigning king. In this sense, all items of regalia are considered stool property-the agyapadeɛ (heirloom). Further, all items of regalia at Manhyia Palace are artistic creations as well as spiritual and consecrated objects. While the visual ornaments delimit the ritual space that protects the person of the king during processions and when the king sits in state, the combined sound of ivory trumpets, poetry of the Kwadwomfoɔ and the Abrafoɔ, as well as musical ensembles create sonic umbrellas to maintain royal distance when the king sits in state or when he is part of a procession. Not all regalia items are deployed during routine ceremonies, Akwasidae ceremonies, or even Ɛsomkɛseɛ (Grand Service) at the Breman Mausoleum, but the full force of regalia are unleashed during the Adaekɛseɛ (Grand Adae) that is celebrated every five years. It is during the Adaekɛseɛ that the Asante take stock and assure themselves that the reigning king has kept intact the state treasury he has inherited on their behalf, in addition to assessing the additions that the king has made.

Collectively, the varieties of regalia are referred to as “processional arts,” or individually as “ceremonial swords,” or “ceremonial horns” and other labels. While these designations occupy center stage in our discourse, they should not be taken for granted, for the term, ceremonial, may not fully capture the complex manifestations of regalia items both in private and public spaces. Furthermore, the above labels may prove limiting in illuminating other considerations, such as the temporal and historical narratives the regalia objects render as they move through space during processions. The metalanguage embodied in the swords and the symbolic language they convey may be lost in such labels. Should the regalia items be regarded as micro-entities in airtight compartments, the implicit intertextual functionality of these items is missed. Intertextuality refers to situations where a regalia item is interfaced with another regalia during a ceremony. For example, what happens when the Asantehene dances fɔntɔmfrɔm atoprɛtia with the mpɔnpɔnsɔn sword and a gun? The entire costume of the bearer of the bosomuru sword encompasses everything that is worn by the custodian but the historical narrative of the bosomuru hat, gyemirekutu kyɛ, is linked to the doku agyepɔmaa gun resulting in the interface of these two regalia items at ceremonies. The asomfomfena (courier swords) are primarily part of the regalia of the Gold Stool and while they carry abosodeɛ (cast gold ornaments), they are intertextually linked with the Nsɛneɛfoɔ (court criers) when they are sent on courier duties. Like Daniel Reed, I do not limit the concept of intertextuality to passages of written or oral language but apply it to the communicative properties of any number of expressive forms (Reed, 2012: 92-93).

Conclusion

Nana Kwadwo Nyantakyi III and I have accomplished a great deal in the past seven years but our work is far from over. With His Majesty Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II’s support and guidance, we are positive that we will complete the remaining twenty percent of regalia items in his custody and that of the Asantehemaa (Asante queen). As we have stated previously, this project is part of Otumfoɔ’s grand vision of transforming and projecting traditional values and culture in the Asante Kingdom and making them relevant in the twenty-first century. Eventually, it is our cherished hope that our modest attempt to capture on paper the tangible and intangible heritage of Asanteman’s complex array of stool regalia in the Manhyia Palace has contributed to a definitive history (the urtext). We hope that the contents of this second edition will broadly enhance our appreciation of the full range and sophisticated variety of expressive arts that support traditional leadership among the Akan in Ghana. We applaud the vision and the courage of Otumfoɔ Osei Tutu II for making the artistic and cultural heritage of over three hundred years of Asante history accessible to the world. Herewith lies the crucial groundwork for a fully professional twenty-first century museum of Asante culture.