Fostering Reasonableness: Supportive Environments for Bringing Out Our Best

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact mpub-help@umich.edu to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

9. The Reasonable Person Model and Prison Higher Education

Abstract

Advocates for North America’s earliest prisons believed that the experience of incarceration produced powerful changes in the hearts and souls of the men and women interred within the new late 18th-century institutions. Their theory of change was clear. Physical isolation plus hard work plus prayer equaled moral and spiritual regeneration (Rothman, 1990, pp. 79–108; Johnston, 2000, p. 69; Upton, 2008, pp. 251–266).

Within twenty-first-century America the sentiment remains strong that, to express it in the language of our own day, prisons have rehabilitative powers. However, prisons today are such brutal and oppressive places that prison professionals, academic theorists, and activists typically place their hopes less in the fact of incarceration—few seriously believe anymore that subjecting someone to a prison regime is in itself beneficial to the person’s development—and more in the programs that exist in a given institution. Departments of correction offer various activities to those incarcerated, including religious programs, sports, counseling, and self-help programs. Educational programming is popular, since research has shown that it’s highly effective at reducing recidivism (Gilligan & Lee, 2004, pp. 314–5; Steurer, Smith & Tracy, 2001).

Unfortunately, while there’s broad consensus that “education works,” there is no agreement on the mechanism by which prison education programs reduce prison violence, improve job prospects upon release, lower rates of rearrest and reincarceration, or accomplish any of the other social goods that they’re credited with (Gaes, 2008; Fine et al., 2001). Indeed, MacKenzie (2008) writes that discussion of theory is “conspicuously absent from the research literature” on education in prison (p. 3). We have a “black box problem” with respect to prison education similar to the one that Karen Hollett (Chapter 15) describes in relation to mediation.

As the director of the Education Justice Project (EJP), a prison education program based at the University of Illinois at Urbana-Champaign, I can attest that those of us engaged in this work seek to identify useful theories of change, organizational models, evaluation criteria, and other foundational elements that can help us to develop new programs, decide whether existing programs are doing a good job, and provide a language that allows us to speak about our work to ourselves and to others. There’s no specialized literature that addresses higher education for incarcerated students and no accepted best practices. There are several fields that help us to situate and guide our work, including critical pedagogy, critical criminology, higher education studies, correctional education, prison writing studies, restorative justice, and peace studies. This is a mixed and useful bag, but it is not complete. We need something in our tool kit that speaks more directly and usefully to human behavior and motivation in a spirit that complements the hopefulness that is inherent to the project of educating men and women who have been discarded by society, the respectfulness and dignity for each individual that most of us bring to this work, and the belief in the power of engaged citizenry, which we regularly see emerge in our prison classrooms.

Editors’ Comment: Sullivan (Chapter 4) and Basu (Chapter 6) address how environments can support individuals and communities.

The Reasonable Person Model (RPM) fits nicely. Among theories of human motivation or individual well-being, RPM stands out for several reasons. It addresses the connection between individual flourishing and social health and transformation and helps us understand the role that environments play in supporting or hindering individual and social well-being. RPM also focuses on the informational needs of individuals, something that resonates well with an educational program concerned with the contexts and conditions of knowledge acquisition and teaching. In addition, RPM is broad enough as a framework that it speaks to prison higher education work across several dimensions, including classroom pedagogy, program organization structure and communications, and public outreach. Indeed, RPM can help us make a persuasive case for the value of prison higher education, against the powerful forces that encourage a punitive orientation.

In the context of prison higher education, I focus in this chapter on the ways that exercising expertise involves (1) opportunities and conditions for gaining expertise (the model-building domain of RPM); (2) gaining competence and having the clearheadedness to utilize one’s knowledge (drawing on the being effective domain); and (3) using one’s knowledge and skills to be useful to others (the meaningful action domain). In the final section I address some of the drawbacks of the term “reasonableness” while lauding RPM’s emphasis on bringing out our best.

The Education Justice Project

The men in the classroom are divided into groups of four or five students each. Huddled in small circles, they discuss the lyrics of the well-known song “La Juala de Oro” (The Golden Prison) by the band Los Tigres del Norte. The song, written in Spanish, describes the despair of an undocumented Mexican migrant whose wife and children, after ten years in the United States, feel no connection to the land or language of their birth. They do not want to return to Mexico. Meanwhile, he has been unable to build a life for himself in the United States and, because he lacks paperwork, fears even to go outside except to travel between his job and his house. The small group discussions proceed in English. “In what way is the man’s life in the United States like living in a prison? Why does he call it a golden prison? What is it like to live in a prison?”

These students should know. They’re incarcerated in the Danville Correctional Center, a state medium security facility in east-central Illinois. The men who pose the questions to them are also dressed in state blues, and they also understand firsthand the separation, isolation, and powerlessness that are integral features of penal incarceration. They are peer instructors, themselves locked up at the prison. Together, they form Language Partners, one of several education programs offered at the prison under the auspices of EJP.

A small group of University of Illinois graduate students, faculty, and community members founded EJP in 2006. Today the program serves about 140 incarcerated men out of a prison population of more than 1,800 and relies on about 70 unpaid instructors, tutors, program evaluators, and other support from the campus and community. We offer upper-division (300- and 400-level) courses alongside a mix of extracurricular activities, including a theater program, a mindfulness course, and business workshops to students who range in age from their midtwenties to their sixties, though most are in their thirties and forties. The majority of them are serving long sentences for serious crimes, and the majority are African American and Latino. Almost all come from lower economic backgrounds. Most of our students spent considerable time in prison before joining EJP, which has no admission requirements other than sixty credit hours of lower-division academic course work. It is difficult for short-timers to enroll in our program, since most people in Illinois are incarcerated without a GED or high school diploma (Illinois Department of Corrections, 2012, p. 22). It takes many years of studying behind bars before a man can accumulate the credit hours that qualify him for EJP classes.

Our students, then, represent the profile of neither a typical incarcerated man nor a typical American undergraduate student. They have developed the seriousness, motivation, and discipline that people so often acquire when serving extended prison sentences. This probably helps somewhat to explain why the men enrolled in EJP have been so impressive with respect to both learning and leadership. However, self-selection doesn’t appear to tell the entire story. In this chapter I consider how providing a respectful environment that gives students an opportunity to exercise agency, collaborate with one another, and engage in meaningful work—all practices that resonate with the RPM framework—have created a climate in which students rise to the occasion. A good example of this is our Language Partners program. We did not design Language Partners or any other EJP programs with RPM in mind. However, the more I’ve learned about RPM, the better I find myself able to theorize our work at the prison and explain our successes and those of similar programs.

Language Partners

Language Partners was the brainchild of an EJP student, Jose “Ramon” Cabrales, who wrote a proposal for the program as part of an EJP business writing class (Cabrales, 2009). He noted that Spanish-speaking men incarcerated at the prison, many of them undocumented foreign nationals, had lacked access to English as a Second Language (ESL) instruction for about five years because of state budget cuts. This made them ineligible for most prison work assignments, which provide not only spending money but also a sense of productivity. It also meant that they were unable to participate in educational programs at the prison. Cabrales estimated that there were between two hundred and three hundred such men and described them as occupying a Spanish-speaking ghetto within the prison. Their lives at the Danville Correctional Center were constrained and their prospects upon release unpromising. Ramon proposed that bilingual EJP students provide ESL instruction to these men.

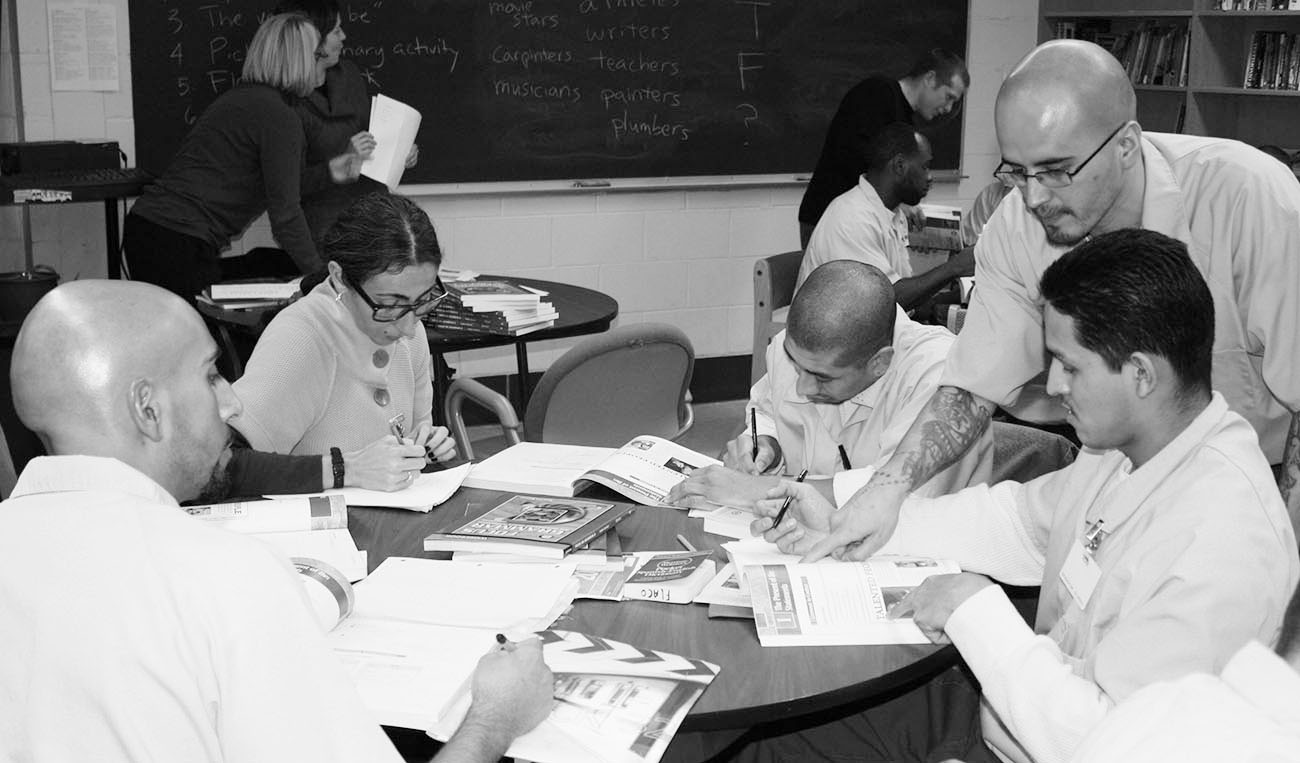

Language Partners has run for over two years now. Classes meet for three hours twice a week in the education wing of the same prison building where we hold all EJP programs. There are twelve English learners, eight peer instructors or teaching partners, and eight resource partners. The latter are university instructors who provide training and resources to the teaching partners and occasionally teach lessons in the Language Partners classroom. However, the peer teaching partners handle the bulk of instruction (Figure 9.1). There is also a group of about fifty waiting partners. These are men who applied but were not accepted into Language Partners. The waiting partners meet, under the leadership of the teaching partners, for occasional English workshops and for guest lectures on topics such as the Mexican Revolution and the bracero program.

We have measured significant improvement in English comprehension, reading, and writing among the groups of English learners who have to date participated in the yearlong program. My focus here, though, is on the teaching partners. EJP students refer to our project as creating “educated men,” by which we have come to mean people who demonstrate self-confidence, critical thinking skills, and effective self-expression and recognize within themselves the capacity to be agents of positive change in the world. The Language Partners peer instructors offer an outstanding example of educated men.

STUDENT EXPERTISE

“When their efforts to act responsibly are frustrated, when they find themselves unable to use their faculties, people suffer” (Freire 1970, 1987, p. 64).

Erick Nava, one of the teaching partners, has not only become a great admirer of the work of Paolo Freire, the innovative Brazilian educator, but is also someone who exemplifies Freire’s insistence that people seek the means to act as engaged citizens of their communities. Through Language Partners he found a way to realize his long-submerged desire to engage in useful activity. Nava, like most of the teaching partners, was a thoughtful and mature man when he became involved in EJP. He had been incarcerated since the age of seventeen for gang-related activities and spent ten years in prison reflecting on his previous choices and earning a GED and then an associates degree in prison. He was a member of EJP’s first class, in 2008, and by that time knew that he wanted to be a force for positive change in a world that he had come to understand favored those with personal and social advantage. But he had little opportunity. Language Partners seemed to provide a way.

Editors’ Comment: Erick Nava’s quote echoes a central RPM theme—that people find meaning in helping others. This can also serve to motivate people who might never have been thought to be capable or interested in providing help.

In 2010 Nava became one of the founding members of Language Partners. He participated for months in planning meetings and also got involved in other ways with getting the program off the ground. Nava helped design flyers to advertise the new program and posted them around the prison, was part of the textbook selection committee, and gave welcoming talks to groups of men from the general population when they, as applicants to the program, arrived for their oral interviews, which he also participated in. He took the summer-long teacher training course that EJP offered and currently teaches weekly in the program. Last year the English learners voted him teaching partner of the year. About his upcoming release, he explains that “it’s cool that I’m going home. OK, great . . . but at the same time. . . . I’m going to miss prison because of this [program]. I’m going to miss prison when I go home. People depending on me.”[1][2]

Editors’ Comment: This is a great example of the cognitive state called “flow” that Ivancich describes in Chapter 5.

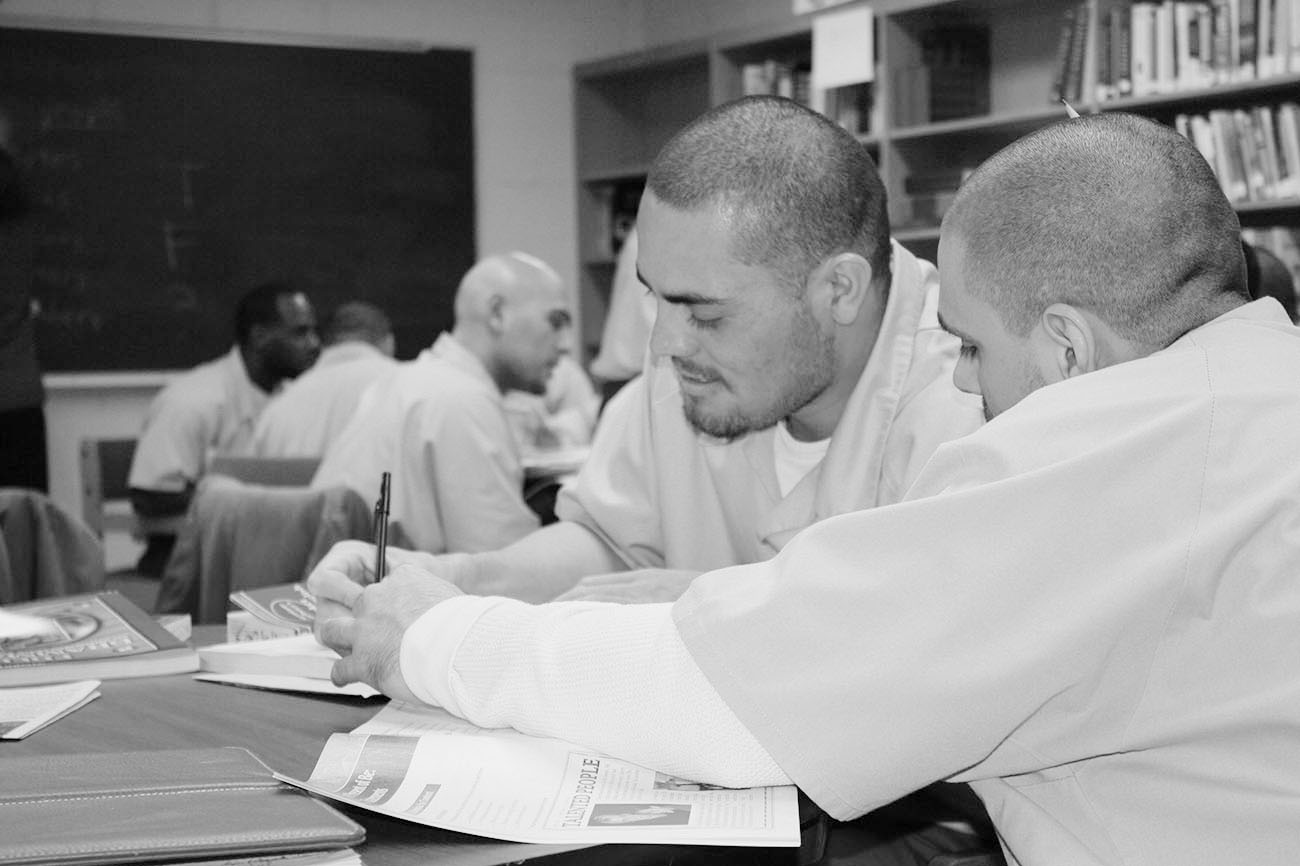

The teaching partners report that they count their participation in Language Partners among the most meaningful activities of their lives (Olinger et al., 2012). It is certainly one of the most time-consuming. In addition to the six hours they spend in class each week providing direct instruction to the English learners (Figure 9.2), they also spend time correcting student papers and designing classroom exercises. In many cases the teaching partners forgo gym, yard, and other activities in order to throw themselves into this work. Ramon Cabrales describes being in his cell at night preoccupied with upcoming classes. “I’m literally lying in bed thinking about how I can make the [upcoming] lesson better. And then it comes to me. ‘Yeah, they’re going to like that!’ It’s a very good feeling.”

The teaching partners also promote literacy and education within the cell blocks. One of them, Otilio Rosas, makes a point of studying in a public place on the wing. When men approach and ask what he’s doing, he speaks to them about the value of education and loans them books. When we started taking applications for the program, the teaching partners energetically encouraged Latino men to apply, stopping them in the chow line and approaching them in the yard and urging them to overcome their nervousness about learning a language. Then two teaching partners went cell by cell through the wings of the cell blocks where they respectively lived, asking neighbors to contribute notebooks to the program. EJP doesn’t provide writing materials, and the teaching partners knew that some of the learners would lack resources to buy their own from the prison commissary.

The teaching partners were obviously effective salespeople. “I expected [donations] from other Mexicans, but I [also] got [them] from white guys, black guys.” After the committee—a group of incarcerated peer instructors and University of Illinois instructors—made the final selection of ten men, several of the teaching partners began working on their own time with those who had not been admitted, applying the teaching techniques they’d learned through Language Partners.

The teaching partners encourage the English learners by distributing small rewards such as pens and erasers in recognition of work especially well done. They purchase these prizes with their personal funds from the prison commissary, which charges inflated prices. When I offered to purchase suitable items on the outside and bring them to prison for them to distribute as they wished, they politely declined. They explained that the prizes had more value to the students because the students knew that they, the teaching partners, were providing them. The learners interpreted the financial sacrifice as evidence of their teachers’ confidence in them, and the peer instructors were desirous of the learners receiving that message.

Other Initiatives

EJP students also shine outside of Language Partners. Since 2011, about fifteen self-selected men have met as the Chicago Violence Group to discuss readings in urban sociology, assessments of violence intervention programs, and other literature that addresses the problem of youth violence. This group originated during an EJP meeting after students shared that they were deeply concerned about the rise of violence on Chicago streets and fearful for their own family members. To their dismay, some of our students, who have long since turned from a gang lifestyle, continue to serve as role models for younger gang members on the outside. They feel a sense of responsibility, then, and an urgency to fight the violence. They also believe that they are uniquely placed to do something about it.

The group is currently designing an intervention program in which incarcerated EJP students will work with young men at the prison who are serving short sentences. Like Ramon Cabrales and the other early teaching partners, the Chicago Violence students have identified an area in which they have special expertise. They have taken proud ownership of their efforts to work together to apply their experience and insights to make their communities safer.

EJP students also recognize and address environmental problems. The Productive Prison Landscapes program is conducting a pilot composting study at the Danville prison and writing a composting guide for other Illinois prisons that seek ways to make good use of kitchen and office waste. A group of student authors are putting the finishing touches on a collection of fiction and nonfiction pieces for high school readers. Their intention is to speak to them in the way that they now wish they had been addressed when they were themselves younger in hopes of turning them from the streets and inspiring them to aim high in their lives. After we inaugurated our theater program, again at the initiative of EJP students—this was a group of men who enjoyed their in-class performances in a Shakespeare course so much that they sought a permanent venue for such activities—several of them declared their intention to bring Shakespeare back to their old neighborhoods. They anticipate that this engagement with the classics will empower youths.

A recent evaluation of the EJP found that 67% of students believe that participating in EJP has helped them increase their sense of responsibility for their actions, for their learning, and to their family and community. Many of those students reportedly held the desire to be change agents before they joined EJP (Tillman, Gannon-Slater, & Greene, 2013, pp. 16–18). Participation in EJP deepened that desire, perhaps because it provided the means. For others, it’s possible that participation in EJP did not increase what was already a strong sense of responsibility but instead merely provided a way to act upon it. Prisons offer little opportunity for those locked up to become civic leaders. To the contrary, the message conveyed to people subject to penal incarceration is this: society no longer wants or needs you. The location of prisons in thinly populated areas reinforces the sense of banishment that is part of the carceral experience. Indeed, it has become commonplace to refer to the state of incarceration as “warehousing,” a term that reinforces the dehumanization of those behind bars. Yet as RPM suggests, a key element of being human is being useful to others.

More Than Courses

The twenty-first-century economy will make it difficult for people burdened with a felony record to find employment if they do not hold a high school degree or higher. However, our experiences with EJP suggest that we are aiming too low if prison educators seek only to provide academic qualifications to their students. Clearly, education programs that allow students to apply what they have learned can provide valuable services, such as English as a Second Language instruction and violence prevention work. But they can accomplish much more than that.

Education programs can be the means by which incarcerated men and women overcome the injuries of separation occasioned by incarceration. In gathering incarcerated people together, pushing them away, and locking them up, our penal system communicates clearly their exclusion from society. But no person is superfluous; cultivating one another’s gifts is one responsibility of a healthy society. For those of us committed to repairing the breaches created through our penal system, programs that allow incarcerated men and women to feel what all of us crave—a sense of usefulness and value (RPM’s meaningful action)—can help mitigate the essential violence of our system of incarceration while also allowing the larger society to benefit from their talents and insights.

Editors’ Comment: EJP fosters competence and creates opportunities to lead and make a difference—the program is an excellent example of a supportive environment.

There is much that EJP is working to get right, but what we have already done very well is provide opportunity and encouragement for our students to work together on projects that they care about, to develop their own programs, to have their voices heard at meetings and in their student-produced newsletters and other publications, and to exercise the oral communication, writing, and critical thinking skills that they are building through their coursework. Without drawing directly on RPM in our design of EJP, it has emerged as a prison education program responsive to its precepts. RPM holds that people seek to decipher the informational dimensions of the settings we inhabit not solely for the sake of our personal comfort within those spaces. We also seek information because it allows us to act with others to make a difference within such contexts. We desire the competence to collaborate effectively and with dignity.

EJP meets the needs of information-hungry actors who seek to navigate their world with confidence and to engage their world with the knowledge that they are having an important impact within it. For our students, this aspect of the program is all the more pronounced by virtue of the contrast between EJP classrooms and the larger prison setting, which does not encourage personal initiative and discourages group action. For instance, Illinois prison administration allows men and women to donate money to causes on the outside and even to conduct fund-raising within prison grounds. Given the small amounts of money that most incarcerated people earn, that sort of activity can make only a small impact. Nor does it provide a hearty platform for exercising leadership. Much of the success we’ve had in doing that lies in our unwittingly applying RPM values to prison education.

Bringing Out Our Best

RPM is not the only theoretical model that helps to break open the “black box” of prison higher education, but it may be one of the most useful. In addition to helping us explain what we’ve observed among students of EJP, RPM can usefully guide us in other areas, including public outreach and organizational communication, as other chapters in this volume suggest (e.g., Bardwell, Chapter 7; Kearney, Chapter 16; Monroe, Chapter 14; and Ryan & Buxton, Chapter 11).

While RPM has been a useful framework, it has one drawback. It would be useful if the model’s name didn’t include the tricky word “reasonable.” Among marginalized groups, the word “reasonable” can have uncomfortable resonances. Asking a person or a community to “be reasonable” is a long-established way of denying perceived injustices and shifting the conversation instead to the accusers’ supposed inadequacies as people. A call for reasonableness can sound like a defense of the status quo.

What is exciting about RPM is that it suggests a path for changing the status quo. A name that emphasized the role of supportive environments in bringing out the best in ourselves and others would better illuminate that. In emphasizing our inherently curious nature, our longing to connect with others over meaningful work, and the desire to exercise and develop competence, RPM draws a positive and hopeful picture of humanity. It counters, especially, common depictions of members of marginalized classes as lazy, socially disengaged, and willfully dependent. Against programs that seek to fix the poor, RPM speaks to the value of putting the agenda into their hands, allowing them to identify their problems and work together on common solutions.

Notes

1. All interviews by Rebecca Ginsburg at the Danville Correctional Center on Monday May 23, 2011, 6–8 p.m.

2. Since his release, Erick Nava has returned to Mexico and now has a full-time job as a schoolteacher, a position he would never have received but for his experience teaching in Language Partners.

References

- Cabrales, J. R. (2009). Institution of bilingual tutorship program. Unpublished proposal.

- Fine, M., Torre, M. E., Boudin, K., Bowen, I., Clark, J., Hylton, D., . . . Upegui, D. (2001). Changing minds: The impact of college in a maximum-security prison. New York: Ronald Ridgeway Inc.

- Gaes, G. G. (2008). The impact of prison education programs on post-release outcomes. Unpublished conference paper.

- Freire, P. (1970, 1987). Pedagogy of the oppressed. New York: Continuum.

- Gilligan, J., & Lee, B. (2004). Beyond the prison paradigm: From provoking violence to preventing it by creating ‘anti-prisons’ (Residential Colleges and Therapeutic Communities). Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences, 1036, 300–324.

- Illinois Department of Corrections. (2012). Annual Report FY2011. Springfield: Illinois Department of Corrections Office of Constituent Services.

- Johnston, N. (2000). Forms of constraint: A history of prison architecture. Urbana: University of Illinois Press.

- MacKenzie, D. L. (2008, March). Structure and components of successful educational programs. Paper presented at the Reentry Roundtable on Education, John Jay College of Criminal Justice, New York.

- Olinger, A., Bishop, H., Cabrales, J. R., Ginsburg, R., Map, J. L., Maryoga, O., . . . Torres, A. (2012). Prisoners teaching ESL: A learning community among “language partners.” Teaching English in the Two-Year College 40(1), 68–83.

- Rothman, D. J. (1970, 1990). The discovery of the asylum: Social order and disorder in the new republic. New Brunswick, NJ: AldineTransaction.

- Steurer, S. J., Smith, L., & Tracy, A. (2001). OCE/CEA three state recidivism study. Lanham: MD: Correctional Education Association. http://www.ceanational.org/PDFs/3StateFinal.pdf.

- Tillman, A., Gannon-Slater, N., & Greene, J. (2013). Becoming an educated man: An evaluation of the Education Justice Project. Urbana, IL: Education Justice Project.

- Upton, D. (2008). Another city: Urban life and urban spaces in the new American republic. New Haven, CT: Yale University Press.