Lineages of the Literary Left: Essays in Honor of Alan M. Wald

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

20. The Present of Future Things

Scholars make their own personae, but they do not make them just as they please.[1] Handcuffed to history, I address the field of the Literary Left in ways that cannot be detached from the succession of highly charged, contextualized experiences shaping and reshaping my life. Summing up the composite autobiographical figure emerging from these unceasing engagements is like taking aim at a moving target. A BuzzFeed version would read “Twenty-five Surprising Things You Didn’t Know about Alan Wald.” I have been tracking my great white whale of Literary Radicalism since high school. Then, during the events of the 1960s, a rendezvous with culture and the Left crystallized into a lifelong pursuit. That decade turned out to be the political Rorschach test of my generation; the passion of its victories and defeats formatted me forever. My scholarly writings will never be understood by reading backwards through my professional career at the University of Michigan; academe was not an end but a vehicle through which other needs and goals might be fulfilled.

As Derek Walcott wrote in Midsummer, “To curse your birthplace is the final evil.”[2] When history intruded in my existence as an undergraduate at Antioch College, my birthplace was conclusively established. I seized upon Marxism (via Jean-Paul Sartre and Richard Wright) as a compelling if partial and imperfect ethical criticism of the exploitative and imperialistic dynamics that coexisted with Western society’s remarkable achievements. In the worldwide eruptions of 1968, I thought I saw a new kind of society in the making through the international alliance of student rebels and working-class militants, the visionary grammar of a historical process suggested by class analysis combined with the imaginative liberties of a metaphor stemming from hope. An observation by Leon Trotsky, Marxism’s stern superego, might suggest why such yearnings, their birthplace still uncursed, are with me some forty-five years later: “Ideas that enter the mind under fire remain there securely and forever.”[3]

More puzzling is psychology, the life of subterranean passions coiling beneath the surface of the various roles that one serially inhabits. Perceiving the world on dual channels, we grapple with disparate temporal regimes generating the inner, elusive contradictions that define our characters. Mine oscillates between hotheaded emotions, sensing everything at once, and a calibrated intellect relentlessly deciphering how one thing follows another. This leaves me with an inability to resist any opportunity to interpret, rushing to hasty judgment too often, and with recurrent aspirations at odds with my temperament and talent. I am convinced that a lack of self-knowledge makes self-deception probable, but how does one differentiate between emotional and factual truth in the realm of hard-wired memories?

Matters that are private, the restless ghosts of my universe, are also the ones that obstinately resist the voicing that precedes comprehension. The traumatizing loss of my father prematurely in 1981 and then the loss of my mother in 2003 brought increased appreciation of their impact on my early life yet not much more. The death of my first wife, Celia, at age forty-five in 1992 after a decade of illness, remains a knotted emotional ache that I will carry to the grave. (Happily this has been offset by the bliss of my romantic partnership with Angela Dillard since 2001.) Curiously, most of my longtime friends, a number of them former students but usually political or scholarly associates, are either a decade or so younger or five to ten years older; almost none are exact contemporaries. As my enemies grow older, I am luckily free of lasting resentments against even those people who aimed to do me harm, yet petty humiliations and embarrassments (including tiny factual errors in my work and some poorly written sentences) are as vivid as ever. I can coolly explain my attraction to literary narratives of exile, unreliable memory, and uneasy citizenship, and all the whys and wherefores for my recoil from those who substitute ideological certainties for the messiness of experience. But I am flummoxed to account for my ironic/sardonic sense of humor that serves largely as an emotional defense as well as my lapses into complete silence in many conventional social situations.

The Making of a Literary Radical

Born in June 1946 in that narrow gap between the closing of World War II and the advent of the Cold War, I was understandably devoid of nostalgia for the preceding era of economic deprivation and the brutalities of the Holocaust. Both were obsessive topics of my tempestuous mother. As soon as I became conscious of the world I never made—one rendered stifling by the hearings of the red-hunters that crowded our tiny television screen, and the air-raid drills (to ward off nuclear bombs) that were a normal part of the school day—I responded with a kind of wary numbness. No matter where I lived—and we moved often, as my father’s career on the President’s Council of Economic Advisors with Leon Keyserling was interrupted by McCarthyism in 1953—I was keen to move on again.[4] It was my gentle, mild father who regularly read to me, first Treasure Island and then Moby Dick, which he had studied in an English class at Clark University with a young Charles Olson. After that I was hypnotized by volumes I saw in libraries, on drugstore racks, and in the family study. Emily Dickinson expressed the reason well: “There is no Frigate like a Book / To take us Lands away.”[5]

With a sister born three years before and a brother coming nine years after, I knew something of the middle child syndrome: a feeling of being left out and invisible, in contrast to the older child who benefits from all the firsts and the younger who profits from being the baby of the family. But perhaps I just didn’t want to put myself out there to be judged by others. I was not at all precocious as a child or young person, compared with my thriving siblings. As a public school student, I had little going for me academically (unlike my sister, gifted in science) or socially (unlike my brother, handsome and athletic). My mother and father, deeply bonded to the New Deal variety of Left liberalism and leading participants in various conservative Jewish synagogues as we moved about, had great expectations of a most conventional nature for all three of us. Nonetheless, I was mired in a fog of mediocrity triggered by a belief that I really had no worthy voice of my own. Still, as they say, you should always keep an eye on the quiet ones.

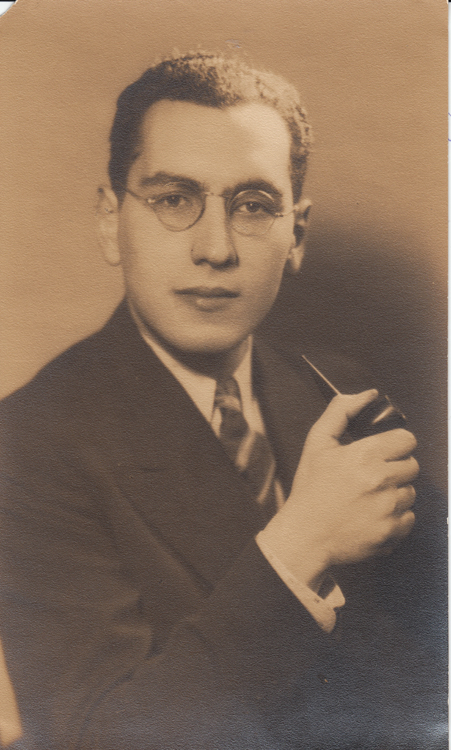

My parents were both born in 1916, Haskell Wolkowich (he changed his name to Wald in 1938) in Worcester, Massachusetts, and Ruth Jacobs, in Glens Falls, New York, although she soon moved to New Haven, Connecticut. They came from generically poor immigrant families of East European—Polish, Russian, Lithuanian—Jewish backgrounds. My grandfathers spoke with accents and held unskilled jobs, such as working behind a drugstore counter or collecting premiums for a Jewish burial society. Marrying in 1939, Haskell and Ruth were a tall, slim, attractive, and active young couple, returning to graduate school at one point to earn, respectively, a PhD in economics and an MA in educational psychology from Harvard University. In contrast, I felt ungainly, lethargic, ordinary, and alienated, haunted by a feeling that I was embarked on a cryptic quest. This was to be a lonely one, concerning only myself; there was no notion that I might acquire knowledge to guide or sustain others. I would always remain both fascinated by and at arm’s length from those who could present their opinions as authoritative.

At first I consumed the books that came my way through family and friends. This started with my father’s musty old set of the science-minded Tom Swift series, followed by my own collecting of Tom Swift, Jr. (I was already something of a completest). Next there was the Tom Corbett, Space Cadet series (1952–56), along with detective mysteries beginning with the Hardy Boys and growing into Brett Halliday’s Mike Shayne novels, with an intermittent Mickey Spillane read furtively under the covers. As I had some temporary fascination with the military, my father gave me a paperback of James Jones’s From Here to Eternity (1951) when I was twelve, suggesting that I might learn something about sex in its pages. The search for more sex led to Irwin Shaw, Leon Uris, Norman Mailer, and other World War II writers.

As I began to pick out literature for more philosophical reasons, I was pulled toward politically radical fiction. Perhaps I was born with a Kafka-like rebel Jewish disposition, but the affinity grew deeper as a consequence of the time in which I was coming of intellectual age—that of the beats blending into the civil rights movement. At first the allure was to writers I saw as antielitist literary intellectuals, certainly not professors or scholars. My inner Holden Caulfield, my adolescent loathing of respectability, led me toward characters and authors who were outsiders; my prime literary love was the strike organizer Mac in John Steinbeck’s In Dubious Battle, who looked like “a scholarly prizefighter, pecking slowly at a typewriter.”[6]

I soon understood that, in some baffling way, I would be a writer myself. My earliest experiments, with science fiction and then in composing the story line for Mad magazine–type comic strips that a talented Hebrew School friend drew, showed me how writing becomes a means of mastering surroundings, enabling one to gain an almost magical power over emotions, uncertainties, and desires. At the least, typed communications differed from less controlled interactions in that they could be edited and rewritten before going out into the world. A toy printing press enabled me to produce miniature newspapers and magazines for a few friends and myself. Some short stories gained praise from teachers and were published in the school magazine.

Yet I understood instantly, and permanently, that my destiny as a writer would be that of a very minor figure—which suited me fine. Moreover, to be a writer did not mean to become a literature student. This seemed unlikely, as I lacked the fantastic ear and verbal recall of my classmates. Rather, writing was about seeing my life as a long struggle against hidden constraints, leaving me no alternative but to write my way out to freedom. Looking back on my meager literary gifts, I realize that I was blessed mainly with an imaginative freedom that approached surrealism yet never quite crossed the border. I was fascinated with metaphoric poetry and prose that translated the world from one realm of perception into nearly its opposite, which I found instantly in Blake, Nietzsche, Rimbaud, and the like. At the same time, I was both drawn to and cautious about theory. To apply an interpretative concept from Freud (an early interest) to a work of art was exciting. But what if one were to impose it to the point of reordering the work’s priorities, excising from vision its subtleties? This caution, a paranoia about being guilty of misrepresentation, was of a piece with an understanding that whatever writing I would do would be generated by a minor ambition—or rather, a great ambition for what I knew would be only minor accomplishments.

I felt that I lacked grand ideas and thought that whatever I wrote would be a practitioner’s work (short fiction, journalism, reviewing), not a theorist’s, because I simply had no ability to create a system of ideas. My grasp of history and sociology were fuzzy, too. Usually at a loss for either a form or subject matter, I felt as if I were on an odyssey, by metro, in the depths of my self-absorbed psyche, with connecting stops in imaginary states gleaned from television and popular culture: I was an ordinary guy with a factory job, a hitchhiker on the road, a struggling literary critic in Greenwich Village (with a beatnik girlfriend who had long black hair), or even an anonymous crew member of a ship. Weirdly, I always assumed that I would spend time in jail, and to this day I still hoard an internal library of intellectual projects to draw on when I am taken prisoner.

Although most of my initial literary efforts from elementary school into my first year or two of college were in fiction and poetry, I should have known early on that imaginative literature was not where my talents lay. I lacked a naturalist’s eye for minute observation; visual descriptions were usually, I thought, the parts easiest to skip in any work. T. S. Eliot was a predictable attraction for me, yet this was due mainly to his plangent mood. My own efforts at verse, which to my later embarrassment were published in college literary magazines, were little more than clumsy efforts to turn adolescent angst into order. I never had, nor would have, any talent for parsing the aural character of language. In poetry I missed out entirely on the appreciation of calibrated rhythms and the witty use of rhyme or assonance. I may have felt the clash and cadence of meter, the ebb and flow of quatrains, yet could not describe these. I also had a distrust of eloquence and intoxicating verbal richness that kept many of the classics (especially romantic poetry) on the back burner. I preferred verse as well as fictional and nonfiction prose devoid of lush emotionalism, writing that spoke with bluntness, or bitter irony, anything to help one see clearly. In all genres I favored clean, unadorned diction, Camus-like spare, deceptively simple lines to inspect intricate facets of the riddles of humanity.

Throughout high school I spent time in limbo as a rebel with countless unknown causes. I simply dissented whenever I felt commanded—or even just pressured—to do something by external authority. At my parents’ insistence I went through the motions of taking Hebrew and music lessons, both of which went nowhere. In school, the actual words of the Lord’s Prayer and the Pledge of Allegiance never passed through my lips, precisely because one was “supposed” to recite them daily. Enviously I watched the television wanderers Tod and Buzz on Route 66 (1960–64), responded with empathy to the nonconformist antics of the beatnik sidekick Maynard G. Krebs on The Many Loves of Dobie Gillis (1959–63), thrilled to the naughty pages of Chester Himes’s Pink Toes (1961), and reeled in shock from the horrors of Dalton Trumbo’s Johnny Got His Gun. (Originally published in 1939, Johnny Got His Gun was reissued in 1959 and fell immediately into my hands.) My father gave me a paperback reprint of David Riesman’s The Lonely Crowd (1950) and told me I was “inner-directed,” or at least definitely not “other-directed,” and my mother had a copy of Paul Goodman’s Growing Up Absurd (1960) that I devoured.

Whatever story I concocted for the essay on my college admissions applications, I did not graduate from high school with any genuine professional ambition. My first impulse was to emulate Jack Kerouac’s On the Road (1957), and the work-study program of Antioch College afforded something of a safe simulacrum. I was still baffled as to what I wanted, so it was attractive to be able to extricate myself every three or six months for short-term adventures in various cities. I would return from a job to the campus in Yellow Springs, Ohio, to try once again to find a footing in some academic field that suited my still inchoate needs. For three years, 1964 through late 1967, I held a steady procession of relatively unskilled occupations (bookstore clerk, stock boy, child care worker, social worker, copy boy, planetarium guard, community organizer) in Manhattan, Pittsburgh, the District of Columbia, and Cleveland; embarked on hitchhiking trips around the East Coast and from Paris by way of the Balearic islands down to Tangiers and back up to London; and indulged in many frustrated dreams of sexual pleasure without commitment and experimentations with drug-induced altered states of consciousness that only briefly led to a desired sense of oneness. Details of these occasionally louche escapades will have to wait for another kind of essay. Any nihilism on my part was relatively short-lived; I quickly found that a little of “nothing is true, everything is permitted” could go a long way.

New Left and Old

By 1968, I embraced the term “Literary Radicalism” as my object of study. I associated it principally with Randolph Bourne, the World War I–era author of The History of a Literary Radical (issued posthumously in 1920). Bourne, who suffered facial as well as bodily deformities, opposed the identification of American culture with Anglo-Saxon culture and broke with his teacher John Dewey over Dewey’s view that the United States could spread democracy through military action. I had originally turned to writers on the Left, even before I knew what that term meant, because I just didn’t like the looks of the life that seemed to be programmed for me. So it made sense that the voice of such a relatively nonideological writer, whose transnational ideals were not tied to a specific socialist tradition, would reach me early. Lacking political sophistication for a long time, I only recognized that we in the United States were an island of plenty in a sea of world privation; eventually I saw that the dream of an American Century, very much in the air under Presidents John F. Kennedy and Lyndon B. Johnson—as it is today in new forms—depends on a teleology of empire. I had no wish to be implicated in this society’s crimes.

I don’t deny that guilt was one small part of that attitude. Actually, guilt is the gift that keeps on giving. But it is essential that guilt be channeled constructively into responsibility, solidarity, and commitment. The compelling ideas of socialism about class structure, racism, philosophy, and justice emerged for me during junior high school, first through imaginative literature by African Americans and European existentialists. Being white or having a prepared purpose in life didn’t express the way I felt. Although I have no memory of religious feelings and was bored silly by all synagogue activities, I emphasized my Jewish identity, with which I felt entirely comfortable. I always told people about the original family name, an opportunity to explain my ethnicity, and boasted that my father was the founding president of the Beth El Synagogue to which we belonged during our two residences in Maryland. This sense of being part of an outsider, minority group in a Christian country (naively, I was unaware that many Jews identified with the political and cultural establishment) was a stepping-stone to identification with the have-nots and outcasts in any situation. Totally entranced by the civil rights movement from the first news of boycotts and sit-ins, and revolted by small episodes of chauvinism toward Arabs that I witnessed during a 1958 visit to Israel, I was becoming an internationalist before I knew what it meant.

Later I began to formulate my literary-intellectual interests more responsibly. This came as I learned about the Dreyfusard tradition of intellectuals serving as moral guardians over the modern state, although the nonconformity of a John Reed was still more my style. I was an enthusiastic member of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) from 1965 through late 1967, much influenced by the two former SDS presidents with whom I worked. In the winter of 1965–66 I joined the idealistic Paul Potter on the Economic Research and Action Project (ERAP) in Cleveland, and then immediately after became a student and comrade of the eloquent Carl Oglesby, whom I helped to bring to Antioch in 1966–67 as “Activist Scholar in Residence.”[7] That fall, however, during my sojourn at Fircroft College in Birmingham, England, a school with a social justice ethos designed for workingmen (there was a sister college nearby), my socialist identity began to form, and with it commenced an uncomfortable drift away from the charismatic Oglesby. Returning to the United States a few months before the May 1968 events, I joined the Young Socialist Alliance (YSA), an organization that seemed to blend a moderate version of Trotskyism with the New Left icons of Malcolm X and Che Guevara. For six months starting in the spring of 1968, I edited a campus literary-political magazine called the Antioch Masses and also wrote (occasionally with coauthor Michael Schrieber) a political column in the Antioch Record called “Le Enragé” (“The Enraged One”); “Les Enragés” was the term for leftist Jacobins in the French Revolution, resurrected in the spring of 1968 by situationists and Trotskyists at the University of Paris at Nanterre.

Both the SDS and the YSA allowed me to combine classic and contemporary (often heterodox) political readings with sometimes round-the-clock activism and find out the degree to which the Marxist method really worked to explain or sustain history and social analysis. My conception of socialism as a way of life—not just programmatic points with an organization to achieve them—grew out of formative, free-floating years in the New Left and then was overlaid (but far from obliterated) by the disciplined collective work of the YSA. I adored both.

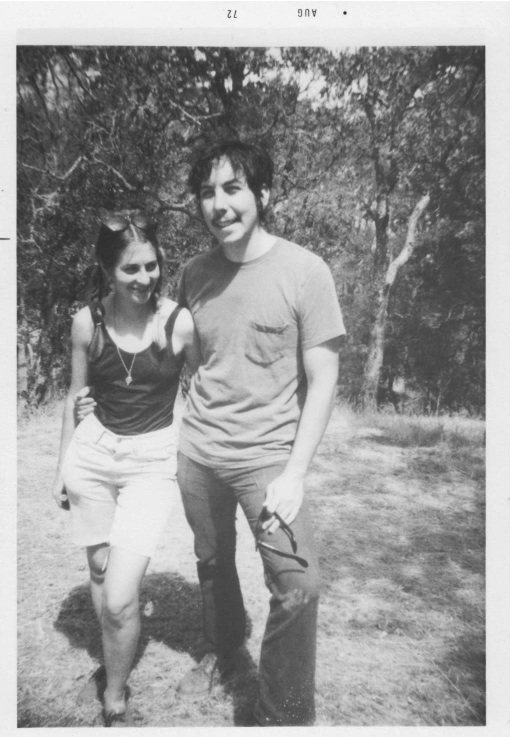

Moreover, such organizational connections combined with the freedom of Antioch and later UC Berkeley, where I was a graduate student, to enable a grand tour of 1960s radical protest. Some of it was pretty ugly. On September 5, 1966, President Johnson came to deliver an address to nearly 75,000 at the Montgomery Fairgrounds in Dayton, Ohio. About 150 protestors, mostly Antioch College students, formed a picket line by the front gate, where we were pushed, spit on, and variously threatened. Then a smaller group, of which I was part, dispersed and individually passed through security. This involved several women, including Celia Stodola, whom I would marry nine years later, hiding sections of a cut-up bed sheet under their skirts. On different portions of it the slogans “Please Stop the Killing” and “Thou Shalt Not Kill” had been painted.

Inside the fairgrounds, about thirty-five of us reassembled in the bleachers. The sheets were then extracted and reattached, and two people raised the ends of one aloft as a banner while the rest of us linked arms in nonviolent protest fashion in a circle around them. Within seconds there was a roar of rage from the crowd, which included people waving Confederate flags, and Johnson stopped speaking. Minutes later at least a dozen fully armed police and private security guards rushed our group, swinging clubs and stepping on our backs and shoulders to rip down the sheet. As soon as it was gone a second sheet was raised and the attack was repeated, to a round of applause from the crowd. We then sat on the ground, arms still linked, with backs facing outward toward a growing mob. As it surged forward, Chief of Police Harlan A. Andrew, according to a Dayton newspaper report, ordered his men to “just walk away,” while another officer loudly declared with a smile that “If anything happens to them now, I’m too far back to help.”[8] My vision was blocked, but I looked over my shoulder and saw members of what appeared to be a motorcycle gang striding toward us. Then we were kicked and pummeled from above. I instinctively tried to get up to defend myself, but the women and men on both sides grasped my arms even tighter, and I couldn’t move. That was it for my “pacifist moment”; I just didn’t have what it takes to tolerate that kind of abuse.

In London in 1967, through SDS contacts with the Stop-It Committee (formed by US students at the London School of Economics in 1966), I was present at the famous October demonstration of twenty thousand people in Grosvenor Square, called by the Vietnam Solidarity Campaign. Our group was assembled around a tiny mock tank that we pushed forward as part of a larger section of the crowd set on approaching the American embassy. Suddenly we were charged by baton-wielding police on horseback, a new experience for me that was terrifying. I promptly turned to run but was held back by a former girlfriend from Vassar College who defiantly stood her ground. I recollect no details after that, but someone in the crowd from the Committee of 100 (set up in 1960 by Bertrand Russell) got the idea that I was a US draft resister and piloted my friend and me safely through the chaos to an apartment, where we were fed and stayed the night.

Zelig-like, I seemed to be at every noteworthy event. Most were peaceful and legal mass actions in major cities. But only ten months after Grosvenor Square, club-swinging police chased me through the streets of Chicago. This was August 1968 during the Democratic National Convention. Earlier in the day I had been talking to Paul Potter in Grant Park when suddenly the police stormed into the center in search of a young man who had apparently lowered an American flag. Teargas was everywhere, and we quickly fled the park, running straight into national guardsmen with .30-caliber machine guns as we tried to cross the bridge at Balboa and Congress Streets. We then turned toward the Jackson Boulevard Bridge to head toward the Hilton Hotel by way of Michigan Avenue. There were thousands of us, and as we drew closer I heard the still-lingering sound of protestors (and perhaps bystanders) being beaten by clubs, choked by teargas, and even thrown through plate glass windows. Then a porcine-looking line in blue charged into our section of the crowd, and remembering Dayton and London, I took off into the darkness under an El.

Eight months after, I was off to California for graduate school on a Woodrow Wilson fellowship, songs of the 1967 Summer of Love echoing in my head. On July 4, 1969, I and Antioch roommate Peter Graumann arrived at our new place of residence in Berkeley, only to find it under National Guard occupation in the wake of People’s Park. Assemblies of more than four persons were immediately broken up. But in less than a year, following news of the US invasion of Cambodia, a massive uprising closed the entire Berkeley campus and then reopened it as an “anti-war university.”[9] A few months later, Ari Bober of Matzpen (the legendary Israeli socialist organization) launched his national tour that preceded the publication of The Other Israel: The Radical Case against Zionism (1972). I was delighted to be asked to serve on the Education Committee to prevent disruption of his talk in Berkeley by pro-Israel fanatics. (It was called an education committee because our purpose was to educate people to behave respectfully during the meeting.) I was far from a hero, let alone a bruiser, but I always felt safe when an activity was organized by the Socialist Workers Party (SWP) of those years, with which the youth group YSA was in political solidarity, steeped as the SWP was in the traditions of the trade union movement. Knowing that veteran militants such as Nat Weinstein, Jeff Mackler, Patrick Quinn, Bill Massey, and Mike Tormey were also on an education committee was reassuring as well.

Why was my Marxism a liberation and not a constraint? In response to their experiences in the Great Depression and World War II, my parents passionately adhered to the tenets of Reconstructionist Judaism. This movement held that religious laws (halacha) must be respected but also updated in light of modern advances in philosophy, science, and historical knowledge. While halacha was never the least bit a temptation, the events in France in 1968 induced me to organize the tropes of Reconstruction around a new intellectual engine: Jean-Paul Sartre’s claim that classical Marxism was the untranscended philosophy of our time. Perhaps remembering my father’s tender if reserved sincerity, I didn’t share the rage of others toward the older generation’s liberal politics, although I did more than my part in griping about efforts by my parents to mold me into conformist roles for which I was unsuited. While fully appreciating the profound contradictions of liberalism and its susceptibility for abuse by those with a sinister or self-serving agenda, as could also be the case with Marxism, my first and remaining impulse was to work through those contradictions rather than dismiss liberalism with a sneer. Updating Trotskyism was always going to be tough, and I joined the YSA with eyes wide open about the limitations of its dogmatic adherence to “dialectical materialism,” which for me was a starting point of any inquiry and not the endgame. Yet if philosophy and cultural theory were addressed on a low level, it was also through the YSA and the SWP that I was educated about gender, race, labor history, anticolonialism, and many more topics that were then sidestepped or misrepresented even in higher education.

My very first, and unpolished, essay in a national publication, written in 1969 and published in January 1970 in a magazine called Young Socialist, urged US radicals to turn to the writings of twentieth-century “Western Marxists” Georg Lukács and his student Lucien Goldmann.[10] Throughout the early and mid-1970s, I contributed prolifically to SWP publications, especially the International Socialist Review, edited by the highly competent Les Evans, and by the end of the decade I was under the spell of the dazzling Marxist scholarship of Brazilian-born Marxist-surrealist Michael Löwy. The SWP essays were not assignments but an effort on my part to expand the range of the organization’s cultural life by drawing attention to matters receiving notice in the broader Left through new studies or revivals. Topics addressed included radical history, political murals, politics and the novel, and recent scholarship on fellow travelers; specific authors were John Berger, George Lichtheim, Frantz Fanon, Edmund Wilson, Chinua Achebe, Mike Gold, John Wheelwright, James T. Farrell, and Harvey Swados. (Some submissions were not accepted, although the reasons may have been justifiable; Walter Benjamin, for example, was only just coming into the picture in the United States, and I was hardly an expert.) My ideas in these essays derived from what I took to be classical Marxism, but the way of looking at the subjects was my own.

In the SWP, which I joined in late in the summer 1969, it was soon evident that my status could be described as “resident alien.” I was drawn to the proletarian/bohemian legacy of the SWP’s past while being distrustful of the burgeoning group of younger and in some cases two-dimensional zealots on the make from elite colleges. The midwestern-born leader of this bland but hardworking undeclared faction initially struck me as serious and polite but turned out to be a control freak with a mysterious inner core. Still, he and his disciples were mostly in my peripheral vision, and the truth is that their political strategies of the late 1960s and early 1970s were often sound and professionally implemented. They were far superior to sections of the Left that relied on disruption and public display more than careful planning, and were thankfully remote from the sequence of sectarian Trotskyist split-off groups that started in 1956 (most of those going by the bizarre term “anti-Pabloite”).

Besides, if one wasn’t interested in fighting for “leadership,” which I wasn’t, there was something of a live-and-let-live attitude. I never voted in favor of the SWP majority’s resolutions but certainly had no intention of undermining the organization. I loyally recruited individuals who showed an interest, and I learned a great deal from the political meetings, forums, classes, and planning of demonstrations. (Sales and proselytizing, however, were circumvented by me as much as possible.) In April 1971, I was an SWP candidate for the Berkeley City Council, an office for which I was monumentally unqualified. More suitably, I had served as the organizer of two large YSA locals and as an alternate member of the YSA National Committee, before I was asked at age twenty-five to resign from the YSA in the fall of 1971. This demand was due to my known lack of confidence in the rising star from the Midwest, who consolidated his reign that year. From then on I was a contented rank-and-filer of the SWP who did simple tasks, wrote literary reviews, and sometimes gave some classes on Marxism and culture.

With my newfound freedom from organizational responsibilities, three Trotskyist veteran writers of the 1930s, all named George, all “Cannonites” (associated with SWP founder James P. Cannon), took an unexpected and extraordinarily generous interest in me. Whatever they thought of my personal politics (we didn’t discuss this much at first), they had seen enough of my work to feel confident that I would be competent to accurately research Marxist cultural history. The upshot was that over the next fifteen years they shared much “inside” information, opening many doors. The three Georges, apparently a popular first name for Jewish Americans of their generation—George Novack (1905–92), George Weissman (half Jewish, 1916–85), and George Breitman (1916–86)—meticulously reviewed my research without ever forcing any of their opinions on me and urged that I try to publish in places that I felt were beyond my reach. That may have been my real “graduate school.” They served as a wonderful complement to the brilliant scholars and teachers who guided my literary work at the University of California at Berkeley, Henry Nash Smith (1906–86), Larzer Ziff (b. 1927), and Frederick Crews (b. 1933). Developing a scholarly life that had high standards but was decidedly driven by concerns other than one’s professional career, I was getting the best of both worlds.

What I also gained in the SWP was an irreplaceable political schooling from the older working-class militants and veterans of 1930s–50s social movements: Asher Harer, Sylvia Weinstein, Berta Green Langston, Frank Lovell, and Ann Chester are a few of the names of individuals still vivid in my memory. At the same time, I didn’t share or repeat the legacy of factional tirades against “Shachtmanites,” “Cochranites,” and so forth, and I was emphatically disaffected from various younger apparatchiks with briefcases who were always on the phone to the national office. (One firebrand orator, Peter Camejo [1939–2008], was among the exceptions to this bureaucratic style.) What kept me a member for over a decade was agreement with a number of specific policies that still are guideposts. I was partly won to the organization by the writings of James P. Cannon on “defensive formulations and the organisation of action,” and I was an enthusiast of the SWP approach to building a mass antiwar movement formulated in the mid to late 1960s.[11] But I never found the organization’s “big picture” of what was going to happen in the 1970s and 1980s, including who was going to do the “leading” of any social transformation, to be very convincing.

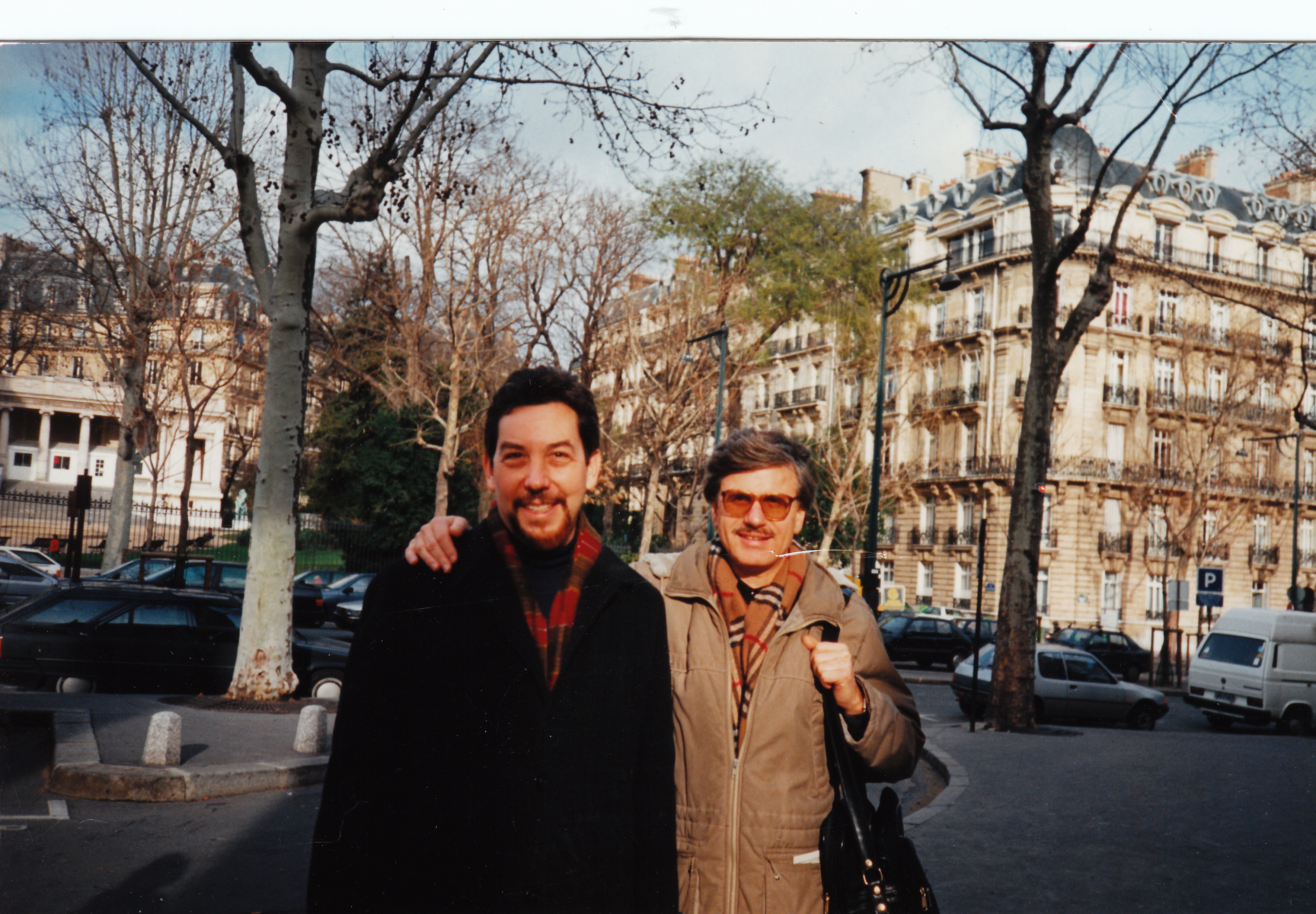

I learned best by being bombarded by a variety of strong opinions, listening with an open mind to individuals who were compelling in their arguments even if incapable of swaying me all the way. This had been the case with Carl Oglesby, and now I felt the same pull from articulate dissidents in the SWP such as Ralph Levitt, Larry Trainor, and others whose convictions about the near future of a resurgent working-class and union movement seemed unwavering. There was one person with whom I felt a stronger intellectual kinship who was entirely different. Robert Langston, a former PhD student of Jürgen Habermas who hailed from Oklahoma, held opinions that always seemed more deeply considered and generous in spirit as well as funnier than mine. Bob’s death in Paris at age forty-four in 1977 severed an important link to the SWP.

All the internal SWP debates, it should be noted, were carried out within the framework of a “Leninism” about which no one seemed to agree. Vladimir Lenin had to be mobilized on one’s behalf, and our unspoken motto seemed to be “The only thing that stops a bad guy with a copy of Lenin is a good guy with a copy of Lenin.” I passively acceded to this, although I saw the traditions of Bolshevism as meaningful to the present only if they could clarify what had gone wrong with previous revolutionary movements and how to prevent a repeat. In the Middle Ages, the argument from authority was considered very strong; for me, in the modern era, it was very weak.

In any case, I’m a person who has multiple elective identities and feel falsely constrained if I have to answer to just one of them. I was comfortable with the broad politics of revolutionary socialism, but the SWP’s evolving notions of what was a “Leninist” political organization became increasingly more dubious, and nothing in the following decades has suggested that it was advancing to new ground rather than regressing to what had been known to fail. Whether writing for SWP publications or elsewhere, I simply chose not to describe my views as “Trotskyist” or even use the orthodox jargon of “degenerated workers state” when referring to the Soviet Union (or the standard description of Stalinism as simultaneously “reformist” and “counterrevolutionary”). The alternate terminology employed by those cothinkers abroad who were unbound by orthodoxy—“revolutionary Marxist” as one’s political self-identification, “transitional” or “postcapitalist” to indicate Soviet-type societies—seemed more apt, even if the latter appear inadequate today. Also, while I thought of myself as in some sense a “cadre” or at least a “militant,” the aspiration to lead an organization or hold some office was less attractive than ever. This is not to my credit. I lacked (and still lack) certain kinds of political smarts. I was terrible at hairsplitting policy, and although I was quick at making criticisms, I didn’t have well-defined alternatives. My views were mainly defined by my long-standing attraction to writings I saw in the New Left Review and by revolutionary socialists of several generations in Western Europe, Latin American, Africa, and the Middle East who were not embraced (or even discussed) by US Trotskyists.[12]

Nonetheless, while I lived up to no one’s expectations as a “party man,” it seemed some kind of principle with me to be candid about whatever kind of radical political affiliation I held. This was mostly because of my desire to put an end to the McCarthy era’s stigmatizing of Left “membership” and my belief that scholars should not be aloof from organizational commitment. As a result, red-baiters have had to do no research to “expose” my past organizational involvements, and the Federal Bureau of Investigation agents who thickened my file with confidential reports were hardly earning their pay. Throughout undergraduate and graduate years, more treasured than earning any academic degrees—BA, MA, and PhD—was my involvement in SDS, ERAP, REP (Radical Education Project), SNCC (Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee), CORE (Congress on Racial Equality), SMC (Student Mobilization Committee), YSA, and SWP, and my sympathy for IMG (International Marxist Group) in Britain, LCR (Revolutionary Communist League) in France—the acronyms go on and on. When finishing my doctorate, for which I did not bother to attend the graduation ceremony, the only “profession” I had in mind was that of “professional revolutionary.” I even had a self-help manual—The New Revolutionaries: A Handbook of the International Radical Left (1969), edited by Tariq Ali.

I came to the University of Michigan in 1975 as an assistant professor, at age twenty-eight, not to begin an ascent up the ladder of academia but as an independent-minded scholar willing to go wherever my research might take me. In the classroom I believed in exposure to every point of view and encouraged students to learn as I had learned—testing ideas out for themselves. As a committed member of the faculty community and proud to be at a public institution, I took inspiration from and did my best to emulate the devotion to literary excellence of Larry Goldstein and Lemuel Johnson, the historical reach of Geoff Eley and Ronald Grigor Suny, the extraordinary teaching of Marvin Felheim and Richard Meisler, and the humane administrative qualities of June Howard and Sidonie Smith. But in terms of the burning social issues of the day, I was a self-disciplined Marxist carrying out a US version of the “Red University Strategy.” This was developed by radicals in Western Europe and promoted in the United States through speaking tours of the Belgian Marxist economist Ernest Mandel (1923–95). Mandel was a comet of learning who was famous for Late Capitalism (1975) but first came to international attention with the two-volume Marxist Economic Theory (1962), which I immediately read upon its English translation in 1968, the year we met. (Dare I call an eight hundred–page book a page-turner?)

In contrast to that wing of the New Left that saw universities as mere accomplices of imperialism and demanded that student activists “shut it down,” the Red University idea was to open them up—to put resources in the hands of those who sought to end international war, abolish the ghettos, and make political democracy viable through participatory control of the economy. I confess that, if the ghost of J. Edgar Hoover is surveilling me even today, Mandel’s writings provided the gateway drug and I became one of the pushers. Younger Michigan faculty of the 1970s and 1980s (John Vandermeer, Ivette Perfecto, Tom Weisskopf, Cecilia Green, Buzz Alexander, Bunyan Bryant) stormed the barricades of a repressive elite Eurocentric culture believing that scholarship and social justice were compatible. In some cases, we (and our student and community allies) didn’t just raise the Jolly Roger of defiance but assaulted the curriculum, priorities in hiring and admissions, and concerns about campus climate with the forward energy of a barreling freight train. Sit-ins, picket lines, teach-ins, building takeovers, demands for divestment, marches on the regents’ meetings, petitions, fact-finding missions (for me, Nicaragua during the Contra War in 1986 and Haiti under martial law in 1993), debates, arrests for civil disobedience (I was convicted in February 1987 for sitting in at Congressman Carl Pursell’s office), and endless meetings were the alternative university we kept alive and is the one I will remember.

Into the New Millennium

Some of the models stemming from the 1960s about how things might unfold had a good run but then by the 1990s were going on life support. Ageing brings wonderful additions—two much-loved daughters, in my case—but then time is less available. It became increasingly difficult to maintain a balance of theory and practice in the absence of the political coordinates outside the university—the protests in the streets—that were supposed to sustain the equilibrium. Even as we aimed our fire at atrocities in Central America, South Africa, and the Middle East, we increasingly found ourselves speaking in the name of an imaginary internationalism that could never find satisfactory embodiment in any organized mass movement. And, of course, we had made mistakes. Contrary to C. Wright Mills’s warning to the New Left against a “labor metaphysic,” I was among those who allocated to the trade unions a highly privileged position in the social pantheon and promoted the 1930s Left too much as a normative radicalism.[13] I learned the hard way, in writing scholarly books, that it is just not possible to counterpose a set of totally “correct positions” to all the errors and misdirections of one’s subjects. History, I knew but sometimes forgot, is the activity of humanity pursuing its aims, and socialism is not an outcome but a process.

Witnessing unexpected situations, a generation’s confidence in the theory of historical trajectory was undermined—probably for the better. Categories that once seemed liberating came to be seen as straitjackets. Our dialectical critique began to feel as frustrating to use as a knife with no handle. In worst-case scenarios, onetime radical spokespersons precipitously suffered the onset of neoconservative derangement syndrome. Some of these offered political recantations that resembled a bad trailer for a Sacha Baron Cohen comedy. Fortunately, I had learned from existentialist inspirers that ceaseless inner conflict is the fate of the truly modern radical; sometimes one needs to boldly embrace the enigmatic to be liberated from the prison house of our own debates, to cast off the practico-inert—Sartre’s term for encrusted habits that induce people to reproduce the past in the present. Some of my former students—Howard Brick, Robbie Lieberman, Paula Rabinowitz, Zaragosa Vargas—had become my teachers.

I am not suggesting that I have now politically achieved some Olympian objectivity. For me, life continues as abnormally as ever. What remains permanent is the struggle between my emotional feeling that taking certain political positions is of the utmost urgency and my rational understanding that disciplined and informed reflection is required for praxis. Often it seems as if someone needs to put a sign over my desk: “Just don’t do something, sit there!” This need to accept contradictions and tensions applies to research on Literary Radicalism as well. Despite all my study and experience, I am hardly immune to simplistic romanticizations of labor, antiracist, and antifascist politics of the 1930s, 1940s, and 1950s. I still hyperventilate at the sight of a veteran of the Abraham Lincoln Brigade and thrill to the defiant stance taken by mathematician H. Chandler Davis when he faced the vile witch-hunters in the 1950s and went to jail. But one has to remember those old debates (the Russian Question, Spain, and so forth) in order to understand the legacy of the Old Left as it was and not as we would like it to be. Even the most heroic Communists were flawed giants; in their unshakable belief that the Soviet Union was the land of antifascism, requiring whatever aid could be obtained, they ultimately managed to seize defeat from the jaws of victory by discrediting communism as a movement that could improve people’s lives. The logic of their theoreticians who justified Moscow’s lies and deceptions sometimes rivaled the chief contortionist at Cirque du Soleil.

The problem in my field is that we radicals love our antifascist traditions as no other political entity, and this is what makes it so hard to write good history about the Popular Front, the Spanish Civil War, the Grand Alliance, and post–World War II competition among the Great Powers. Too many fine people were then willing—often by simply not asking questions—to sacrifice humanity to their own dubious vision of “progress.” This meant the substitution of slogans of solidarity for personal responsibility, and for the untidiness of experience, as can be seen in the response of many to the ambiguities of Popular Front practice. Like Isaac Asimov’s Hari Seldon in his The Foundation Trilogy, the Old Leftists—and here I mean not just Communists—thought they had figured out the laws governing history and society even as their lives became part of patterns and currents indiscernible to them. The Left of today has not transcended a basic challenge posed decades ago by George Orwell: the central problem of how to prevent power from being abused. One may hope that future writings in the vein of how to “Change the World without Taking Power” and in favor of a political strategy of “horizontalism” will eventually assist in producing some new thinking.

Yet I say all this from a position of complete sympathy with the Old Left’s humanitarian objectives of internationalism and an economy democratically controlled by the producers, and I am not at all certain that I would have behaved under comparable circumstances much differently than they did. In relation to the new movements such as Occupy Wall Street and Boycott, Divestment, Sanctions, I am a student, not an adviser, although I certainly feel an obligation to raise questions to debate. Righteous superiority has no place in passing judgment on the Old Left, the New Left, or this New Millennium Left. Self-important condescension is like peeing on oneself: everyone can see it, but only you get the warm feeling that it brings.

Search for a Method

I followed a curious route for a radical literary scholar of the baby boomer generation. Graduating from Antioch College as a literature major in 1969, with a reasonable background in the classical as well as modernist canon due to my extraordinary teacher Milton A. Goldberg (1919–70), my imagination was also shaped by courses with Oglesby on the literature of rebellion. I had acquired an unusual background in Marxist history and theory mainly from New Left and socialist study groups and carried out independent reading in Walter Benjamin, Georg Lukács, Jean-Paul Sartre, Simone de Beauvoir, Frantz Fanon, some of the Frankfurt School (obviously Herbert Marcuse), and British Communists such as Christopher Caudwell, Arnold Kettle, and Raymond Williams. When I started the PhD program that fall at UC Berkeley, where Marxism was simply not taught in the English Department, I simultaneously enrolled in an off-campus seminar with philosopher Richard Lichtman on the young Marx. The two literary specialties that attracted me were African American literature (Richard Wright, Lorraine Hansberry) and European modernism (Franz Kafka, Virginia Woolf), and my nebulous goal was to formulate a Marxist cultural theory that would advance their understanding.

Yet two years into graduate school, “theory” became a precipitous growth industry in English departments, taking off with the craze over structuralism, and I found myself quietly converting to a new agenda emphasizing history and primary research (including biography) about US writers intimately connected to Leftist social movements. I can’t fully explain this turnaround, one that kept me at a distance from the proliferating new generation of Marxist theory-heads who soon engaged poststructuralism, deconstruction, and postmodernism. Perhaps I overreacted by concluding that we held incompatible definitions of “literary theory”; I saw mine as empirically grounded in life and society, while their treatment of texts suggested the Platonic allegory of a soul sprouting wings and escaping the body.

This reaction against what I saw as overly academic Marxism may explain why as a graduate student I chose James T. Farrell, author of the Studs Lonigan trilogy, to guide me through the labyrinth of the cultural Left. Farrell was still alive but nearly forgotten as the Irish American novelist who blended tough-guy Marxism with a sensibility bouncing between Marcel Proust and Honoré de Balzac. In choosing him as the subject for a doctoral dissertation in a leading English Department still fixated on classics, where a previous proposal by a graduate student to write on Mike Gold had been turned down, I was well aware that Farrell was no paragon of stylistic or personal respectability. He was regarded as a crude naturalist, and the biographical information in circulation depicted an irascible womanizer who consumed enough booze to render the entire population of Studs Lonigan’s Chicago South Side neighborhood insensible.

From our first face-to-face meeting in New York, however, I saw things differently. Drinking and drugs (“uppers”) aside, the congenitally disputatious Farrell, whose sidekick I then became for the last five years of his life (1974–79), possessed a temperament that was rooted in an impetuosity stemming from a blend of his political and literary idealism. His passions for socialism and art were set at a pitch of heroic resolution early on, in the 1920s bohemias of Chicago, Paris, and Greenwich Village. After that he committed himself to a struggle that called on the utmost determination of his will and spirit. Farrell left a visible mark on US culture in the 1930s and 1940s on his own terms. He was difficult but worth it.

I just loved the forked consciousness of such restless minds in and around the Marxist tradition: the Richard Wright of The Outsider, the Simone de Beauvoir of The Mandarins, the Lorraine Hansberry of Les Blancs. My extensive personal interviewing of Farrell, and of the many other Old Left veterans to whom Jim introduced me, became decisive for my literary-historical method. William Blake wrote that “[t]he road of excess leads to the palace of wisdom,” and in the area of the oral history of leftist writers, no one seems to have followed that road more excessively than myself.[14] Since 1974, when I bought my first tape recorder, I have interviewed or otherwise communicated with writers and their friends, political comrades, and family members—some five hundred people in all. I also went personally to talk to the older generation of scholars who founded the academic field of Literary Radicalism—Daniel Aaron, Walter Rideout, and James Gilbert. Their books, collectively, had been the Rosetta Stone that helped me to translate a past rendered nearly indecipherable by McCarthyism.

I had learned much from moving back and forth between Rainer Maria Rilke’s view that art dwarfs criticism and Walter Benjamin’s conviction that criticism can sometimes surpass art in teasing out what had been sealed within its cultural forms. Now as a hands-on researcher, I learned all too well what the theorists tell us about memory—that it is a construction, not an imprint. In trying to dredge up the past, we grasp at the imperfect recollections fluttering inside our heads and piece together a story about what might have happened—or sometimes what we wish had occurred. Every oral history must be approached with a morsel of legitimate doubt. And in some cases, the well is just too deep for the truth to be recovered. In writing about myself, such acquired wisdom weighs heavily.

In the 1970s, a rising generation of radicals shaped by the 1960s inaugurated the Marxist Literary Group (MLG), of which I was quite aware but not an early member, and produced groundbreaking journals such as Social Text, to which I subscribed immediately but never submitted writing. My natural tendency in responding to competing scholarly approaches on the Left is to attempt to prove my case by producing superior work—not by attempting takedowns, excoriating others as anti-Marxist (which usually leads to a counterproductive debate), or by the cagey positioning of myself among the various schools. I self-identify as a classical Marxist but of a capacious variety who is happy to learn what I can from Western Marxism, postcolonialism, gender studies, and more.

Consequently, in the 1970s and 1980s, I just listened and read during the escalating theory boom and concentrated on my own research. When I wasn’t engrossed in socialist political activism, I was either sitting by myself in the Special Collections rooms of libraries or else traipsing from coast to coast in search of old reds to interview about their experiences. In 1979 as an assistant professor, I was most comfortable relating to radicals in the profession by writing short reviews for Radical Teacher, which presented itself as more activist and antielitist than MLG because it was linked to social movements. I didn’t attend an MLG institute until 1986, a few years after I had engaged in my own more cautious use of theory in The Revolutionary Imagination (1983). I felt welcomed for what I had to offer as a cultural historian, and I participated regularly for a decade and a half until the premature death of my formidable comrade Michael Sprinker, who had by then become a central figure in the MLG.

Part of this aberrant itinerary was due to a personal “outlaw” temperament of being “never so lonely as in a crowd”; the bandwagon aspect of the sudden rush toward theory-heavy journals such as Tel Quel was off-putting especially because it seemed as if many of my newly converted contemporaries were bypassing Marx and Engels (not to mention Lenin and Trotsky) and seeing Plekhanov only as a target. But maybe I just recognized that I would never be in the same league as the inspirers of my graduate school years, Fredric Jameson and Terry Eagleton. I read Jameson’s Marxism and Form (1971) almost the day it appeared, and I carefully followed Eagleton’s new work on ideology in the New Left Review. I recognized that both were the “real deal,” far above my own capacity in that discipline, and I didn’t want to be a camp follower or hanger-on—although I happily borrowed and adapted their ideas, especially in The Revolutionary Imagination and in the chapter on ideology and the novel in The New York Intellectuals (1987). Thus, I instinctively gravitated in a direction where I might make a complementary but signal contribution to Marxist scholarship on my own terms through original archival research.

Never anticipating that I would find, like, or be able to keep a university position, I wanted to be a sophisticated but lucid writer on literature and politics who was primarily part of an insurgent social movement; one nonacademic fantasy was to be a staff member of a socialist publication, crafting book reviews, essays on politics and culture, and occasionally coverage of labor, antiracist, and community struggles. Harvey Swados was a kind of model I had in mind after I wrote a piece on him in 1971. I read everything by Edmund Wilson and the early Partisan Review editors, who were originally outside the academy, but I was mainly looking at sentences and paragraphs of Isaac Deutscher (blacklisted from academe), Perry Anderson (who didn’t become a professor until his early forties), Hannah Arendt (who was nearly fifty before she began teaching), and Ernest Mandel (who started teaching around the same age). Noam Chomsky, I suppose, was the main exception among my extrauniversity models: a professor who pushed his right of academic freedom to the limit, speaking out courageously on the burning issues of the moment.

The Trilogy

American Night was envisioned initially as part of a single-volume project inaugurated in the late 1990s with an expectation that it would appear at the start of the new millennium. But the material was disobedient. The upshot is three volumes totaling about thirteen hundred pages and issued at five-year intervals: Exiles from a Future Time (2002), Trinity of Passion (2007), and American Night (2012). The publisher is the University of North Carolina Press, with which I began an association in the early 1980s through the nurturing of Iris Tillman Hill. Each volume accentuates a chronological stage: the early 1930s, the antifascist era, and the Cold War. Thus, the big narrative of three decades is crosshatched with self-contained mininarratives, allowing them to be read independently or even out of sequence.

My aim was to reopen the dossier and recount with fresh eyes the story of the (pro-Soviet) Communist presence that was hegemonic within the wider US Literary Radicalism of mid-twentieth-century fiction, poetry, and criticism. In the early 1930s, with the domestic breakdown of the economy and the international rise of fascism, Communism had emerged as the chief radical force in most of the arts. Two decades later it was beaten out of American letters during the “culture wars” of the early 1950s. How was its contradictory presence expressed? How did it evolve? What is its legacy?

Such a book project wasn’t dictated by any dearth of outstanding monographs about major elements of this subject, especially concerning Great Depression social realism and McCarthy-era political witch hunts. I’ve accomplished much grueling original research with which I am pleased, but I make no claims to be the “first” and “only.” Nor do I sensationalize my research; the disclosures presented about political affiliations and personal lives of writers are modestly made and heavily contextualized. Since there exists a genuine community of activist-scholars in the field of Literary Radicalism, the three volumes are filled with the names of scores of older specialists, contemporaries, and younger individuals to whom I am variously indebted, not to mention nonacademics from whom I have learned. But I felt that no one else, including the astonishing Michael Denning in his excellent and nearly comprehensive The Cultural Front (1998), had really addressed many of the subtleties of the subject in a synthetic manner.

One impediment to everyone’s work was widespread secrecy among cultural workers about their Communist Party affiliation, manifest through obscured and sometimes byzantine forms of commitment that I treat as a mode of “converso culture” in connection with “memory loss” and “institutionalized forgetting.” For those who lived through McCarthyism, onetime Communist convictions and affiliations became the love that dared not speak its name. Such a trauma causes the rearrangement of mental furniture, and the Old Left veterans and their families themselves became unreliable sources of information. In a disconcerting way, US culture of the late 1940s and 1950s became “de-Communized” in literary history in a manner that recalls the Warsaw Ghetto Uprising becoming “de-Judaized” in Soviet political history.

Moreover, it didn’t seem as if the elusive definition of a “Communist writer” had been effectively explored by researchers apropos those who refrained from wearing membership on their sleeve. Previous scholarship depicted writers such as Arthur Miller as just “a liberal” and Lorraine Hansberry as a “civil rights” activist rather than as long-term pro-Communists (whatever the murky details of their organizational affiliations). Then there was the puzzle of “Stalinism,” too often evaded or simplified. Whereas conservative scholars demonized Communists, a number on the Left found that if one merely labeled a writer a “progressive,” one really didn’t have to talk that much about the terrible price of illusions in the Soviet Union.

Presentism cannot be entirely avoided, but well-meaning attempts by radical scholars to create an idealized usable past for the Left can distort the effort to understand real strengths and weaknesses. What one sees in literary history as in political history so often depends on one’s priorities, which is not necessarily harmful. But some scholars regard the candid disclosure of very serious political errors or human failings as “red-baiting” or personal attacks. For my part, I’m a devotee of Jane Austen, who said of her own heroines that “pictures of perfection . . . make me sick.”[15]

To be sure, I was no novice in the political field and carried my own baggage, which made me uncertain of my suitability to serve as a relatively dispassionate appraiser. Between 1978 and 1994, I published three monographs and two volumes of my collected essays, mainly on the noncommunist Far Left. While I criticized “anti-Stalinism” when it became a mask for antiradicalism, and looked distrustfully at orthodox Trotskyism, the politics of these books was squarely in the camp of revolutionary Marxism and socialist internationalism. This meant that I had a profound critical distance from the politics of Soviet Communism, already expressed frequently, and had no desire to devote years of my life to writing a book merely to take literary Communists down another peg.

Still, I was unquestionably sympathetic to the ideals of the Party rank and file. Moreover, I had accrued plenty of experience as a stalker of literary ghosts, following many traces across the pages of forgotten Left publications to eventually disclose the political and personal truths of writers who lived and worked in the shadow of the rise of fascism, World War II, and the early years of what some now call “the short American century.” So, in the mid-1990s I possessed a divided mind about this particular undertaking. For a while I tried on some alternative hats, none of which really fit.

Then near the end of the decade, I was impelled toward a new assessment of Communism’s literary presence while editing a University of Illinois Press series called “The Radical Novel Reconsidered.” This consisted of paperback reprints of lesser-known left-wing fiction from the middle of the twentieth century. I started to read in unknown territory, departing from the standard lists and bibliographies to seek out what might be seen as heterodox novels, especially by women, writers of color, and gays and lesbians. It turned out to be an exhilarating experiment in literary spelunking, exploring unknown caves and virgin territory. The marginality of a work of art has always been a source of interest for me, and my fascination with uncovering neglected fiction induced me to follow suit in poetry, drama, and Marxist literary criticism when the University of Illinois Press series was terminated for financial reasons. Suddenly I had become a left-wing Isaiah Berlin, picking up the crumbling collected works of half-forgotten novelists or ones considered beyond the pale and sometimes finding high philosophical and political drama in them. (And like Berlin, I expected to be accused of exaggerating the importance of a work in the interest of vivifying a knotty political-intellectual problem.) This unorthodox reading list became the literary basis for the trilogy, which is less about the “radical canon” than largely unfamiliar works, and involves an effort to devise critical methods appropriate to their interpretation.

Communism and Modernism

In terms of writers negotiating the tripwires of Stalinist dogmatism and literary modernism, American Night tells lots of different stories in some detail. From the 1970s to the 1990s, I was attempting something like intellectual portraiture, but in this volume I created a full-blown “humanscape,” a neologism I borrowed from a personal letter about the 1930s from critic Alfred Kazin to novelist Josephine Herbst.[16] This requires an engagement with far messier questions that flow from the uneasy relationship of one’s life to aesthetic categories: What did complex left-wing humans, with their unique biographies of trauma and pain as well as Marxist commitment, and memberships in multiple communities of gender and ethnicity, in addition to class, actually produce over a lifetime? To fully explore the impact of radicalism on art as mediated by the artist, the critic must address not only political and aesthetic challenges and trajectories but ethical and emotional ones as well.

As the book’s title suggests, the majority of the stories I narrate in American Night are typically marked by personal pain and artistic neglect, by the Communist Party as well as the cultural establishment. My work has often concerned the study of failures, no doubt because I identify so strongly with outcasts. But for my scholarly purpose of re-creating an oppositional tradition, studying frustration is as fruitful as studying success. This is because every ordeal of struggle comes with a lesson for Literary Radicalism, and every lesson lives on in the historical memory I have tried to create as a bulwark against oblivion. And in American Night, I tell of writers increasingly at odds with Stalinism (even if they did not think in such terms) while remaining anticapitalist. Ann Petry’s first two novels were not treated well by the Communist press, but she had friends in the Communist movement. She and Jo Sinclair (Ruth Seid), a slightly younger parallel writer, are examples of anticapitalist radicals who eventually went their individual ways after intense engagements with Communism, even as political nostalgia profoundly informed their art, The Narrows (1953) and Anna Teller (1960), respectively. Thomas McGrath, in contrast, was loyal to Stalinist-type politics, but as a brilliant modernist poet he was always embroiled in artistic controversy with his comrades. And so on.

Another generalization that animates the book concerns a growing autonomy in radical writing that might seem counterintuitive in the context of Cold War repression from all sides. Even if a writer genuflected to the Communist Party publicly, at least by making no political criticisms of it, he or she might continue truly dissident work in the private world of art—through poetry in little magazines, popular fiction, and even somewhat commercialized genres as detective and science fiction. (Sometimes pseudonyms and fronts were required.) Even if a writer was not producing work that I mischievously call “Communist literary modernism,” he or she might be experiencing a new kind of freedom in no longer being held captive by the kind of “positivist rationalism” and “moral certainty” that prevailed before World War II. Furthermore, as a consequence of the new postwar situation, even the most organizationally connected Communist writers could be more on their own. Instead of the big and dynamic League of American Writers, there were only smaller and weaker formations where the Communist Party was present—the National Council of the Arts, Sciences and Professions; the Committee for the Negro in the Arts; Contemporary Writers; the Harlem Writers Guild; and the New Writing Foundation. Attacks on artistic “formalism” in the Soviet Union were reproduced in the United States, and “people’s art” was the Communist aesthetic of choice, but the New Masses was dying in the late 1940s and was much less authoritative than it had been in the 1930s. The 1946 Albert Maltz controversy, when the Communist novelist was pressured by the Party to recant his objections to the notion of “art as a weapon,” put a damper on critical statements and the kind of writing one might submit to Party venues, but most pro-Communist creative writers had merged into the mainstream during the war and did pretty much as they pleased in their professional and personal lives so long as no political deviancy was suspected. The US version of Zhdanovism was ugly but could be circumvented. And when a literary controversy erupted several years after the Khrushchev revelations and the end of McCarthyism, a group of talented writers (led by Charles Humboldt) simply walked out of the Communist Party and merged with the early New Left.

In writing my trilogy, I operated with the belief that in the coming debate among activists of the Left on what will be the physiognomy of twenty-first-century socialism, the heritage of the self-conscious and self-critical strain of the leftist literary sensibility that I have sought to re-create will be one of the moral and political reference points. But nothing is certain, and the downfall of the Marxist movements we built in the 1960s ought to be profoundly humbling. What remains of the tradition of the Literary Left today looks like a disrupted system, fractured yet conveying information nonetheless if taken up by a new generation trained in the streets as well as the classroom. Where it goes next, however, is out of my control. At the moment, a kind of populist anarchism has displaced socialism as the vocabulary with which radicals discuss politics. If that remains the case, then my trilogy may ultimately be judged something of an archaeological treatise.

The Future of Present Things

Looking back over forty years of scholarly writing, I recognize that I have always thought of Literary Radicalism as having a history of its own, distinctive due to a conspicuous degree of historical self-consciousness. Its practitioners as well as the scholars who study it are frequently joined together with political militants and social movements in common projects marked by shared moments of fun, fury, pleasure, and pain. Moreover, Literary Radicalism has always been about changing the world; its most farsighted proponents have been acutely aware that each “present” faced by the sequence of generations in its lineages affords a multiplicity of possible lines of development. To adapt St. Augustine, Literary Radicalism is about “the present of future things.”[17]

Very much like the Mississippi River, the course of the era of Literary Radicalism on which I concentrate—from World War I to World War II, from the New Deal to the Cold War, from proletarian literature to the New Left, from the Popular Front to radical feminism and black nationalism—is shifting, muddy, treacherous, and filled with snags. By 2014, research on left-wing writers has expanded decisively beyond its onetime fixation on the Great Depression, and into the 1950s and 1960s. In culture after World War II, one finds traces of the Marxist experience in a variety of locations from high modernism to middlebrow to pulp, which includes of course gay and lesbian, multiethnic, and women’s literature. Even the core language of Marxist-inflected Literary Radicalism can be seen as riven with false friends due to the presence of semantic ambiguity, incommensurable words for concepts, and cryptic coinages.

These problems and much more have produced a sequence of “paradigm dramas” in a series of books that promote methodologies for the study of Literary Radicalism. This study started with Daniel Aaron and Walter Rideout but went on to include Paula Rabinowitz, Barbara Foley, Michael Denning, and many more. Again and again we ask: What are the sets of assumptions, concepts, values, and practices that constitute a way of viewing Literary Radicalism for the community that studies it through several intellectual disciplines? The more one researches the subject—from the intricacies of the domestic Left to its transnational connections—the more it seems that that there is no coherent, comprehensive perspective for the critical imagining of Literary Radicalism. Thus, the trilogy I completed in 2012 is not just a literary history but also a record of my own struggle to understand that history, a journey where each point of arrival has turned out to be a stepping-stone rather than a destination. By the time I reached the era of the Cold War, I found myself composing the history of an absent presence and the writers who abjured or obscured association with it. I am close to concluding that the untranslatability of the movement—due to its plurality and contingency—may have to be the fundamental assumption by which to approach Literary Radicalism.

At present I am at work on a book-length balance sheet of what was learned from this effort, “Literary Radicalism: A Counter-History.” Residues and slippages of memory surround Literary Radicalism to a greater extent than any other politico-artistic trend in modern times. The place of 1920s expatriatism is indelible, and postmodernism is the subject of endless dissection. Curiously, the cultural Left is closer to a “forgotten” moment, even though there is a considerable amount of scholarship about it. Perhaps we should call it largely an “unknown” moment or a “never-known” or supposedly too well-known moment insofar as the extant overall literary histories and public discourse are concerned. But practitioners understand that historically based scholarship about the class struggle is significantly a struggle against a closed past and also means a struggle for the reactivation of the unexpected, the untapped potential of an eclipsed and buried past.

The essays at the core of Lineages of the Literary Left were presented in March 2013 against a background of events shaping a new generation of activists: massive convulsions in the world economy from the financial crash of 2008; the great uprisings in the Arab world, with their remarkable mass-based struggles for democracy; and the emergence in the West of spontaneous forms of resistance to austerity politics and its fierce attacks on the lives of millions of people both in and out of employment. As this book appears, I end my profession as a classroom teacher, enabling a new vocation of wielding the “weapons of criticism” as a full-time writer on behalf of many literary and political loves. I see the organizers of and participants in the 2013 conference and this 2015 volume as setting a new intellectual agenda for myself as well as others. I hope I will be worthy of it.

Notes

1. This essay is based on material reworked from several public lectures at the University of Michigan in April 2013 and also from Grant Mandarino, "Outlaws, Rebels and the Revolutionary Imagination: A Two-Part Interview with Alan Wald," Red Wedge, June 2013, Part 1 (even though it says "Part 2"), http://redwedgemagazine.com/articles/outlaws-rebels-and-the-revolutionary-imagination-pt-2, and Part 2, http://redwedgemagazine.com/articles/outlaws-two.

2. Derek Walcott, Midsummer (New York: Farrar, Strauss and Giroux, 1984), xxix.

3. Leon Trotsky, My Life (1930; reprint, New York: Dover, 2007), 432.

4. I was born in Washington, D.C., in 1946, eight years after my father began government service with the Federal Reserve System, the Treasury and Commerce Departments, and the National Security Resources Board. We moved to Chevy Chase, Maryland, in 1951, when my father began his term on the President's Council of Economic Advisors under President Harry S. Truman. But with the switch to the Dwight D. Eisenhower administration, a behind-the-scenes red-baiting attack was launched against Council Chairman Keyserling, resulting in the withdrawal of funding that temporarily disbanded the body. My father then spent part of 1953 as an economic adviser in Korea with the United Nations, after which we moved to Arlington and Belmont, Massachusetts, where he taught in a program at the Harvard Law School and wrote the book Taxation of Agricultural Land in Underdeveloped Economies: A Survey and Guide to Policy (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1959). In 1955 we moved to West Orange, New Jersey, when he began a job on the Board of Governors of the Federal Reserve Bank in New York, teaching classes at the New School for Social Research. In 1958–59 the family moved to Greece while my father worked as economic adviser to the Bank of Greece under sponsorship of the United Nations. After returning for another three years to New Jersey and the Federal Reserve Bank, in 1962 he finally took us to Bethesda, Maryland, where he served in the Treasury Department, as chief economist of the Federal Power Commission, and then as senior economist and director of the Office of Regulatory Analysis of the Federal Energy Regulatory Commission before his death from brain cancer in 1981.

5. "There is no Frigate like a Book," now a famous poem, was initially a passage from a letter written in 1873, first published in volume 1 of Dickinson's Letters (1894).

6. John Steinbeck, In Dubious Battle (New York: Penguin Classics, 2006), 14.

7. I have written about some of these experiences in "A Theater for the Poor: Cleveland and SDS/ERAP in the Mid-1960s," Against the Current, no. 155 (November–December 2011): 13–18.

8. "Peaceniks Silenced," Dayton Journal Herald, September 6, 1966, 2.