Lineages of the Literary Left: Essays in Honor of Alan M. Wald

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

10. The Crab Cannery Ship Boom, Amamiya Karin, and the Precariat: Dance Dance Revolution?

In 2008, a nearly eighty-year-old proletarian novella became an overnight best seller in Japan. The magnum opus of Kobayashi Takiji (1903–1933), The Crab Cannery Ship (Kani kōsen, 1929), is a story about workers aboard a ship organizing against dehumanizing labor conditions. It is a work that all well-educated people in Japan had heard of but few had actually read. In Japan, as in throughout what we used to call the First World, research on proletarian literature during the Cold War was often met with incredulity if not outright scorn, but dedicated scholars kept the field going, and Takiji’s oeuvre, and this work in particular, came metonymically to represent the entire movement.[1] In concert with the boom, a new English translation of The Crab Cannery Ship is now available after being out of print for a couple of decades.[2] That the boom happened was stunning, even to those of us working on proletarian literature, but even more remarkable was the way that the boom seemed to speak to and for a generation of youths known as “the lost generation.”[3]

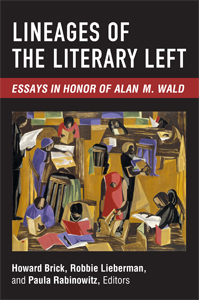

Annual sales of The Crab Cannery Ship are typically about five thousand copies per year. In 2008 that number jumped to over five hundred thousand, and that does not include sales of the four manga (graphic novel) versions that reached many more readers.[4] Media attention to the boom was characterized by surprise followed by interest in how this might affect youths. A segment from Super News Anchor, a morning news program that aired in 2008 when the The Crab Cannery Ship became an overnight best seller, illustrates these points.

In the Kinokuniya store in downtown Osaka highlighted in this news clip, sales in May 2008 reached nearly four thousand copies. By the autumn of 2008, the The Crab Cannery Ship boom was being discussed everywhere in Japan, including women’s fashion magazines, Playboy, television news, highbrow journals, and the blogosphere. New phrases were coined, including the verb “to do ‘crab cannery'” (kani kō’ suru, meaning to do degrading labor), and the lamentation “this is just like The Crab Cannery!”[5] In May and June 2009, one stage adaptation of this work and another play about its author were produced in Tokyo, and in the summer of 2009, blockbuster director SABU released a major motion picture with innovations for a new generation: the handsome Matsuda Ryūhei in the lead, the class-traitor superintendent of operations remade as a straight-from-anime villain complete with scar and cane, and a closing theme song by boy-band Nico Touches the Walls in an ending that rocks.[6]

In 2002, Douglas McGray famously declared that postindustrial Japan may not make anything anymore, but it does make cool, referring to the growing international interest in Japanese popular culture such as anime, manga, video games, television dramas, and pop music.[7] Calling this “gross national cool,” McGray wondered whether and how Japan would be able to cash in on this new form of soft power. It is perhaps premature to say that Japan is postindustrial, given, for example, the renewed focus on dire work conditions among those employed in manufacturing being highlighted in a much discussed NHK (national broadcast) documentary, Freeters Adrift.[8] But there has been a discernible shift from manufacturing to flexible, immaterial labor, so McGray’s formulation struck a nerve. In response, Kukhee Choo writes that “the Japanese government shifted its focus from a century-long practice of promoting traditional arts to supporting the popular culture industry under the banner ‘Cool Japan.'”[9] In 2004, the Content Industry Promotion Law was passed to further promote already profitable popular culture.

While it has not been as economically successful as hoped, Cool Japan has been much celebrated as a successful national rebranding. But Cool Japan embodies the central contradiction associated with youths. On the one hand, Cool Japan represents the rich entertainment industry of young people. On the other hand, young people are bearing the brunt of the now quarter-century-long recession that has badly injured the Japan Inc. brand of the high growth years and, along with it, its social hallmarks: family, school, and corporation. Early in the recession, the neologism “freeter” (made of the English “free” and German arbeiter, or “worker”) emerged to describe young educated people who opted out of corporate society, choosing instead part-time or contract work to allow them to live a supposedly freer life. Much criticism was directed at freeters for failing to grow up and assume the adult responsibilities that would supposedly have saved Japan from the ongoing recession. But the discussion has changed and it is now widely recognized that those former good jobs have disappeared.

In Anne Allison’s choice formulation, “So, when such a construct of youth sells commodities, it is claimed as ‘gross national cool.’ But when real youth fail to get steady jobs or reproduce, as did their parents, they are castigated for not assuring Japan’s future—what gets rendered as a crisis in reproduction.”[10] Allison contrasts the “enterprise society” of the economic bubble period held up by “the three pillars of school, family and corporation” with the neoliberal flexible economy based on service, asking with earnestness what new “pillars” might take their place.[11] As possibilities, Allison identifies emergent freeter unions (unions that can be joined by anyone, regardless of workplace), nonprofit organizations, and the kind of antipoverty activism practiced by participants in an emerging precariat movement. “Precariat,” a neologism combining “precarious” and “proletariat,” was first used in the 1980s by French sociologists, but with decades of intervening neoliberalization and the 2008 economic crisis, it has gained new traction. Guy Standing sees the precariat as a global phenomenon, consisting of people who lack labor-related security including labor-market security, employment security, job security (within one’s employment), work security (protection against harm at work), skill reproduction security, income security, and representation security.[12] While this is inflected differently in different cultures, there are several key features of the global precariat: “it consists of people who have minimal trust relationships with capital or the state, making it quite unlike the salariat. And it has none of the social contract relationships of the proletariat, whereby labour securities were provided in exchange for subordination and contingent loyalty.”[13] The securities sought by postwar social democrats, labor parties, and trades unions have been diminished by the transformations wrought by a flexible economy, a reliance on temporary workers, a turn to migrant labor, and the resultant loss of social support.

Within this matrix in 2008, a dusty communist novella became a best seller in Japan, inviting us to think about how the literature of the proletarian movement is being reconceived as culture of, by, and for the precariat. Although there is a precariat movement, as of yet it lacks the strength of the leftist proletarian movement of the 1920s and 1930s. Moreover, the blockbuster film based on The Crab Cannery Ship was hardly a product of the precariat movement but has much in common with it. Perhaps it represents a beginning culture of the movement: new catchphrases, manga, blockbuster film—disenfranchised youths embracing a proletarian novella in the vernacular of popular culture? In short, that the boom happened at all was breathtaking, but what really got people talking (which in turn fueled the boom) was the way it was reportedly being consumed and remade by youths. So, beyond the why was the tantalizing question: Did this portend a developing consciousness among a young generation known as the lost generation? And if so, what kind of consciousness and how different from the proletarian novella is it?

The Crab Cannery Ship, Russia, and the Making of the Boom

This 1929 novella describes a motley crew of seasonal workers who fish for crabs and then can them aboard ship. The ship’s superintendent charts a course to the treacherous waters between Russia and northern Japan, subjecting the contract workers to brutal treatment. As the ship sets sail ceremoniously, the fishing company’s manager descends down into the hold: “The fisherman’s shit-hole was lit by feeble electric lights. Its air was thick with tobacco smoke and the odor of crowded human bodies; the entire cabin stank like a toilet. People moving about in their bunks looked like squirming maggots.”[14] The superintendent spits on the littered floor and declares:

Needless to say, as some of you may know, this crab cannery ship’s business is not just to make lots of money for the corporation but is actually a matter of the greatest international importance. This is a one-on-one fight between us, citizens of a great empire, and the Russkies, a battle to find out which one of us is greater—them or us. Now just supposing you lose—this could never happen, but if it did—all Japanese men and boys who’ve got any balls [XX] at all would slit their bellies and jump into the sea off Kamchatka. You may be small in size but that doesn’t mean you’ll let those stupid Russkies beat you.[15]

![Figure 10.3. Excerpt from the original publication of The Crab Cannery Ship, in Senki [Battleflag], May 1929. Figure 10.3. Excerpt from the original publication of The Crab Cannery Ship, in Senki [Battleflag], May 1929.](/m/maize/images/13545968.0001.001-00000012.jpg)

The original publication, shown in figure 10.3, includes a double X (“XX”) six lines from the right near the bottom.[16] These are characters used by authors and/or editors to avoid words or phrases that would have provoked the censors and led to banning and fines. This is a minor example, and the XX—“balls”—would at a glance be comprehensible without violating obscenity rules. It was not uncommon in proletarian literature for entire sentences to be replaced with X’s or ellipses, but this was published in Senki (Battleflag), the organ of the largest proletarian arts organization Nippon Artista Proleta Federacio, which took greater chances, often provoking the censors.[17] In fact, the second installment, in which factory hands say they hope the emperor gets stomach cramps after eating the crab, caused the June 1929 issue to be banned. Writer Ibuse Masuji (1898–1993) recalled having heard from a female clerk at the Kinokuniya book store that in the late 1920s and early 1930s, Senki would be placed on the front counter and sell a hundred copies in the first day because savvy customers knew to buy it before it was banned the following day.[18] To summarize the rest of the story: Amid unbearable work conditions, a fishing trawler that embarked from the cannery ship accidentally washes up on shore in Russia. A kind Russian family takes the fishermen in, and they receive a rudimentary introduction to communism pantomimed by a Chinese interpreter speaking in broken Japanese:

“Boss do nothing, get rich. Proletariat always this.” (He showed a person being choked.) “This, no good! Proletariat, all you, one, two, three . . . hundred, thousand, fifty thousand, hundred thousand, all, all, this.” (He imitated children joining hands) “Get strong. All right!” (He slapped his arm.) “No lose, nobody. Understand?”[19]

If some in the proletarian movement could be accused of using theoretical language that was inaccessible to the general working class, here was the message made plain and simple. The interpreter pantomimes the “rich man boss” fleeing and Japan becoming a “good country” with “all working people.”[20] It is important to notice that the goal is a country of working people.

A couple of days later when the storm calms down, the shipwrecked men return and share their experience. Meanwhile, two major events leave those on board alternately hopeless and angry. First, the superintendent decides not to go to the aid of a nearby ship signaling SOS because it would have meant losing a week of work, so 425 men die. The men aboard the crab cannery ship realize that the other ship is insured for more than it is worth, so the ship’s demise is profitable. Then, the death of a coworker by the superintendent’s neglect and abuse makes the workers realize that none of their lives is valuable, despite the rhetoric often employed by the manager that they belong to the great empire of Japan.

So they organize and strike. And just when they might be successful, the navy destroyer that has accompanied them all along—to protect them from the Russians, they were told—sends soldiers aboard to arrest the leaders of the strike. Crestfallen, the men realize that they have lost. But as they are packing the crab meant for the emperor and making the objectionable comment about how they hope it gives him cramps that is not replaced with X’s or ellipses, they suddenly understand that they could win if they all stood together rather than letting the leaders be arrested—the lesson learned from the trip to Russia. The threats to their lives and well-being occur on the ship, but the insight into how to combat them is gained from that accidental trip. The novella ends famously: “‘Well, let’s do it again, one more time!’ And so they rose. One more time!”[21] The story is followed by a postscript about how the second strike was successful even though they all end up getting arrested. But after being released, the men spread out to various sectors of labor to continue organizing. The key points: the lesson about worker solidarity is learned from Russians, and the emphasis is on creating more humane working conditions.

How and why does this become relevant in the neoliberal twenty-first century? On the one hand, there were material factors that laid the groundwork. First, Communist organizations have maintained Kobayashi Takiji’s legacy by keeping his works in print, promoting scholarship, and honoring him with a graveside ceremony on the anniversary of his death as well as evening remembrances that include scholarly talks and musical and theatrical performances celebrated throughout Japan, such as the 2009 graveside ceremony. With a special focus on remembrance and legacy, these events highlight Takiji’s commitment to fight against Japan’s nationalist-imperialist project as well as the tragic circumstances of his death: arrested on the street on February 20, 1933, Takiji was subjected to brutal torture and killed while under interrogation.

Second, the Takiji Library was established in 2003 and maintained until 2008 by Mr. Sano Chikara, retired president of Oracle in Japan, who channeled his considerable energy and wealth toward the promotion of new scholarship, hiring committed scholar and curator Satō Saburō to build the library, sponsoring four symposia, and sponsoring the publication of ten books, including a new manga version of The Crab Cannery Ship.[22] Sano’s extraordinary zeal for promoting Takiji took a hit with the economic crisis of 2008, but by then he had accomplished his goal: to bring Takiji’s works back to the public’s attention. Having graduated from Takiji’s alma mater, Sano was motivated by school and civic pride, as he explained, and he spoke with conviction about how important it was for young people to learn the lessons in Takiji’s literature—although I was left wondering how far he would be willing to take that.[23]

But there were also the strange workings of chance: a young, precariously employed paperback stocker at a bookstore read an article about the relevance of The Crab Cannery Ship to contemporary workers by a new breed of public intellectual-activist, Amamiya Karin; ordered 150 copies; and handwrote a note encouraging the working poor to read it. And the final whimsy, a news story about the boom in early May was written before the boom was real. But the story itself circulated, and as it did, it became real. Norma Field described these developments:

Two liberal newspaper articles, an initial book order of 150 copies, then a conservative newspaper article turned the trickle of interest into a flood. Finding a story that sells is of course a central preoccupation of the media, with the hoped-for outcome being a cascade of sales. The aura of newsworthiness prompted publishers to reprint more copies, bookstores to provide more space, provoking further media attention, then more copies reprinted.[24]

In a turn of phrase that invites us to keep thinking, Field calls the boom “a miraculous meeting of pure contingency and absolute necessity, of commercial appetite and human need.”[25]

Amamiya Karin and The Crab Cannery Ship

The match that lit the fire of the The Crab Cannery Ship boom was a transcribed discussion between author-activist Amamiya Karin and author Takahashi Gen’ichiro that appeared in the Mainichi Daily Newspaper on January 8, 2008.[26] Amamiya remarked that she had recently read the novella and was struck by how it seemed to be describing the current state of freeters. Takahashi responded that he had just recently taught the work in a university seminar and that while he had planned on teaching the students about the idea of the proletariat, he was surprised to have them tell him that they already got it and that it was just like their lives.

Amamiya Karin (b. 1975) has emerged as an author, activist, and advocate for the precariat. She debuted in a 1999 documentary The New God (Atarashii kamisama) by leftist filmmaker Tsuchiya Yutaka. Twenty-four-year-old Amamiya was lead vocalist of an ultranationalist punk rock band, The Revolutionary Truth, when she was invited by the Japanese Red Army (a controversial communist group) on a trip to Pyongyang, in the Democratic People’s Republic of Korea.[27] Tsuchiya gave her a camera and asked her to record a video diary, which she did with great emotional candor. The documentary progresses as a three-way conversation between Amamiya, her bandmate Itō Hidehito, and the filmmaker (who also appears onscreen) as the three discuss politics and Amamiya struggles to confront the source of recessionary Japanese suffering.

Amamiya has since developed into an extremely prolific and topical speaker and writer. She tackles issues related to not only youths in poverty, including bullying, social withdrawal, and suicide, but also NATO, the G8, and the problems associated with nuclear power and weapons. Amamiya resists being called a leftist, not least because she is committed to thinking compassionately about those on the right, and she recalls with gratitude how it was the right wing that first gave her a sense of community and opportunities to think about the relation between individual suffering and social structure. She writes that “It is an opposition movement against the fact that people all over the world are forced into instability because of neo-liberalism, which is advancing globalization.”[28]

Articulate and self-aware, Amamiya speaks for and to a generation of youths who feel disenfranchised from economic power. Her fashion sense is deliberately youthy and provocative: from Lolita goth to faux schoolgirl to a frilly white baby-doll dress, she presents herself as a representative of youth. She is sensitive to the media mix of popular culture, producing music, film, blog, tweets, fiction, nonfiction, and demonstrations in a style that combines a well-rehearsed emotional vulnerability with a hard-core defiance. Part of the appeal of Amamiya as a spokesperson-mascot for the precariat is the way she appears to function independently not only of all the organizations—including family, school (she withdrew), and corporations—that have been contaminated by association with Japan Inc., but also, interestingly, of old-school organized politics. Working within the same culture generative of capital represented by Cool Japan, Amamiya’s affective labor insists on affirming nonproductivity.[29] Undoubtedly, she profits from her productivity; still, she parlays that into an appeal for those without the same benefits.

Even Amamiya was surprised to find out about the boom. She recalls that on May 2, 2008, at the Indies May Day in Gifu, she was with a bunch of twenty-something students, freeters, regular employees, and Internet café employees all talking about work conditions when someone said, “Isn’t it just like Kani kō?” “Unfortunately,” writes Amamiya, “I was drinking, so I don’t exactly remember what was just like Kani kō.“[30] She reflects:

Kani kōsen [The Crab Cannery Ship] turned into Kani kō [Crab Cannery], and it was appreciated as “my story” by the 21st century precariat—freeters and others forced to do precarious temp work, but also including those regular employees who are management in name only and the unemployed. That would surely surprise Kobayashi Takiji.[31]

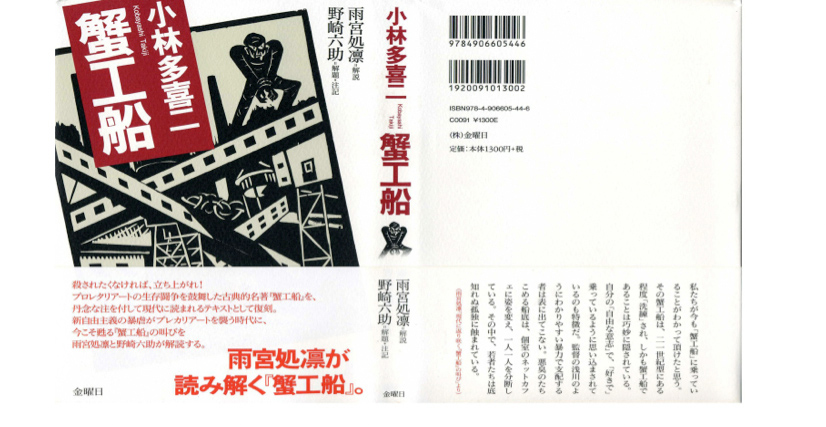

Most often, leftist literature is reissued by publishers sympathetic to the entreaties of scholars who insist that there is, or at least ought to be, a reading public. But in this case, the nearly eighty-year-old communist novella was already available in print by a mainstream publisher, when, anticipating increased market demand and the celebrity appeal of an afterword by Amamiya, the leftist press Kin’yōbi issued a new edition in response to the boom. In her essay, she meticulously details how The Crab Cannery Ship describes work conditions that are remarkably similar to the precarious work situations faced by irregular workers in Japan today. Amamiya insists that labor conditions in The Crab Cannery Ship are not remote at all, although they may seem remote to those with the wherewithal to purchase the book. She focuses on those doing manual labor (in contrast to contemporary scholars who focus on immaterial labor) and, moreover, focuses on those whose working conditions are as harsh and precarious as the fishermen and canners aboard Takiji’s ship. To give just one example, Amamiya explains that contemporary employers are hiring workers as “contract” (ukeoi) workers, but the laws regarding these contracts are even less regulated than the much-discussed “temp” or “dispatch” (haken) workers, enabling even greater exploitation just as the sailors and factory hands aboard Takiji’s factory ship face greater exploitation in the unsupervised waters of Kamchatka. Not subject to labor laws or even “temp” regulations, there is little supervision, and there is also unfair firing. All of the big companies that represent Japan—Hitachi, Tōshiba, Canon, Toyota, and so on—use this contract labor system, it was revealed in 2006.[32] The Crab Cannery Ship therefore is not remote: “In this tale overflowing with depictions of an exceedingly ‘cruel’ workplace, there are many uncanny similarities to the lives of young people living in the 21st century.”[33]

Moreover, Amamiya explains that like the workers on the ship, atomized workers in Japan are all floating along isolated from each other and she never imagined that they would be able to unite. But then, she writes, it happened: “Labor unions like Goodwill, Full Cast, M. Crew were formed one after another at companies with daily dispatch (temp) workers, breeding grounds for the working poor, and now, all over Japan independent labor unions are being formed in which anyone—whether a freeter or just an individual—can join.”[34] New labor unions—especially freeter unions—have arisen to try to bring together disparate individuals: “Young people who have been divided, made to compete with each other, yelled at and fired for demanding rights while living in such uncertain times, have begun to stand up for themselves like the workers in The Crab Cannery Ship.”[35] In conclusion, she refers to the Indies May Day March, which connected freeters and others, wondering whether The Crab Cannery Ship could possibly be a catalyst for youths in the way that Russians are within the novella; yet in so doing she removes the significance of Soviet Russia altogether.[36]

Dance Dance Revolution?

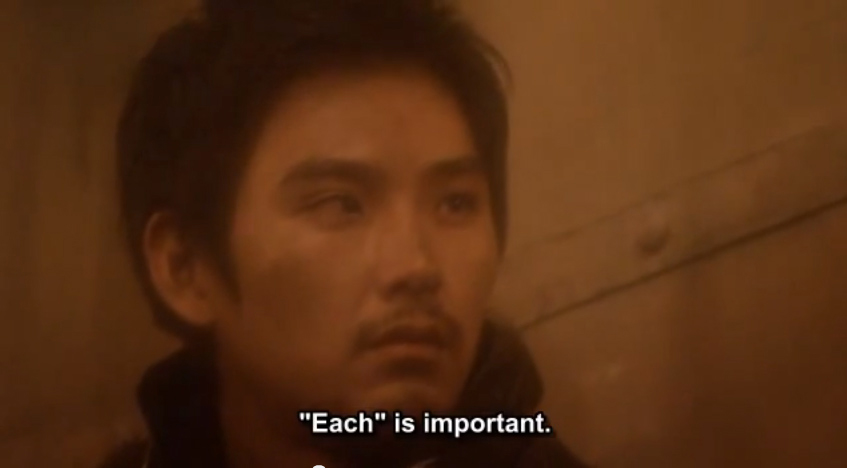

SABU’s blockbuster adaptation follows Takiji’s storyline more or less, with a twenty-first-century style makeover that is also a substance makeover. One of the most significant changes SABU made in adapting the film was the transformation of the Russia scene; instead of being stranded on shore in actual Russia, the fishermen are picked up by a Russian transport ship, and this entire scene is filmed with filters that suggest the fantastic.

With a carnivalesque dance party in the background, a Chinese interpreter dressed as a joker explains the truth of the ship to the men in enigmatic broken Japanese: it is their own fault that their labor conditions are so bad, he says—they just need to decide for themselves what they want and then act on it.

With no talk of the rich getting richer off of working people’s labor, this wisdom from the joker sounds less like a lesson in communism and more like the kind of neobourgeois advice routinely dispensed by adults in Japan to the “lost generation” as it has grown up in recessionary Japan. Although Japan famously has had a low unemployment rate, “one-third of all workers, but half of all young workers between the ages of 15 and 24, are irregularly employed. . . . Without steady employment, fewer youth are marrying, having children or leaving parental homes. Moving from job to job and getting stuck in time without the means to become ‘adults,’ youth are futureless—a state they also get blamed for.”[37]

SABU’s film quotes imagery from two film classics (Sergei Eisenstein’s 1925 Battleship Potemkin and Charlie Chaplin’s 1936 Modern Times), combining the two into a tragicomic indictment of industrial capitalism for a postindustrial youth audience. At the end of the film, the workers organize and present a list of their demands to the manager. The navy boards the ship and shoots Shinjo (idol Matsuda Ryūhei, one of the two fellows who went to the Russian ship); the men then become despondent and go back to work as usual, having failed, until they spontaneously come to the same realization (that they should have banded together), and they walk off the job together with blood-splattered flag flying and an energetic theme song appropriate for a video game.

In contrast to the novella, it is not entirely clear what comes next for the workers in the film. In one of the scenes showing their organizing, Shinjo—reflecting the neobourgeois ideology learned on the Russian ship—asks the group what they want to be. And they answer variously: a doctor, a teacher, an architect, a singer says the only man on this ship not attractive enough to be a pop star. But the point is that no one wants to be a factory worker, because in 2008 “‘kani kō’ suru” (to do “crab cannery”) briefly became a new verb, meaning to do degrading labor. The film leaves it unclear whether there is the possibility of factory labor with dignity or whether the only answer is to get a better job and move into the bourgeoisie, a solution that would have disgusted radicals in the 1920s and 1930s.

To return to the Russian boat scene, the two protagonists turn to each other, saying “we were wrong” to think they could not change things. Then Shinjo asks Shiota “What do you want to do?” and the answer is “I want to dance up a storm.” This is the coming-into-consciousness moment when Shinjo and Shiota realize that they must act in order to effect change, so why is this represented by a dance party? Doesn’t anyone on this Russian transport ship work? Like the popular arcade game Dance Dance Revolution (DDR), the revolution itself is effaced by its invocation. On this Russian transport ship, the superintendent is cool, joining in the dance party and affirming the superiority of the Russian way—but where is the revolutionary message? Russia no longer offers the specter of Communism but rather a phantasmic dance party. In the next scene, the two are returned to the ship, exhausted but also energized and inspired.

When I invoke DDR, I am not just being frivolous: I want to think more about how the lost generation forms communities and projects aspirations for the future. SABU’s reformulation of the Russia scene as a phantasmic dance party speaks to the recession generation’s (lost generation’s) ambivalence about labor. DDR is a wildly popular arcade game introduced to Japan in 1998 in which players follow prompts on a video screen and step on motion-sensitive squares to score points. While the promotion of Cool Japan is intended to strengthen Japan’s economy and its gross national cool, popular culture is also blamed for the failures of youths, including outbreaks of violence. Since 1989—when it was discovered that the one responsible for kidnapping, sexually abusing, and killing young girls (Miyazaki Tsutomu) had a large collection of horror films and anime—there has been a moral panic regarding certain aspects of popular culture referred to as “otaku” culture. In Japan, the connoisseurs of video games, manga, anime, collectible figurines, and so forth are unflatteringly referred to as “otaku” (although a positive self-appropriation of the term is also apparent). Otaku are considered to be socially maladjusted and to prefer dwelling in virtual reality. Media attention to otaku habits in each new shocking instance of youth-initiated violence adds to the panic about pop culture as the problem. More recently, in 2013 in the United States, it was revealed that the shooter (Adam Lanza) responsible for the deaths of twenty-six people at the Sandy Hook Elementary School was an avid fan of DDR, prompting a similar panic about popular culture.

As in any cultural subgroup, there may be those with mental illness who need treatment or those with the wherewithal to be cruel, but it is hard to fathom why DDR could be considered the cause of a murderous frenzy. Practicing psychoanalyst Saitō Tamaki insists that although he identifies otaku as those [men] who use female anime characters as masturbation aids, he also insists that this perversion (in the psychoanalytic and thus not pejorative sense) in the imaginary realm does not interfere with their daily lives because sane people can tell the difference between the two. Tamaki adds that “This is another way in which Miyazaki Tsutomu was entirely exceptional.”[38]

Popular culture is glorified when it leads to economic growth but is blamed for the failures of youths and a contradiction emerges when the recession generation uses the vernacular of popular culture to remake images of revolutionary authority. For Miriam Hansen and others, “vernacular modernism” describes the ways Hollywood cinema grappled with modernity through popular culture, dignifying it as a means to diversify agency. What if we also read otaku culture, like DDR and manga, as part of the process by which the recession generation makes sense of precarity rather than as a cause of decline?[39] SABU’s creative introduction of the “happy dance party” scene is important, because this is where the two “lost” Japanese workers are ideologically reoriented in an atmosphere that is carnivalesque and notably lacking in labor. The revolutionary message to be learned from the Russians is to dance dance, with a revolution yet to be determined. DDR, as an example of Cool Japan, represents the successful promotion of commodity culture, but it also rhymes with the way youths are themselves rethinking and remaking political activism.

May Day, Mayday! M’aidez!

In 2012, I joined the Freedom and Life May Day March in Tokyo. The march was in its ninth year (the sixth since Amamiya joined), so it had started to acquire its own sense of historical mission, one that grows and changes from year to year. It is an independent May Day demonstration, organized in conjunction with the All-Japan Freeter Union (not affiliated with any political party or old-school labor unions). Throughout the world, May Day is commemorated as an international day of labor. May 1 is an official labor holiday in over eighty countries, and in many more, the day is marked with marches and demonstrations. In Japan, May Day is not an official holiday, but it falls during Golden Week, a string a four official holidays: April 29, Showa Day; May 3, Constitution Day; May 4, Greenery Day; and May 5, Children’s Day. As a result, many aspire to take the entire week off. During the period of high economic growth, Golden Week was associated with luxury, including overseas vacations for those who could afford them.

May Day has been celebrated in Japan since 1920 after the formation of the Socialist League and continues to be observed in Tokyo and elsewhere by organized labor. But the Indies’ Freedom and Life May Day is an attempt to redefine May Day by organizers at the All-Freeter Union—a union that allows anyone, regardless of employment, to join and therefore initiate new forms of community. The Freedom and Life May Day 2012 Planning Committee was responsible for a well-organized march and a two-page list of “slogans.” Corralled into a single lane by police, the 2012 march moved energetically in a circuit through the busy streets of Shinjuku (despite a downpour that began midway) as Amamiya Karin issued call-and-response slogans such as “Liberate Shinjuku!” and “Let’s make some noise in the streets!” with a danceable, syncopated rhythm. Headed by a sound car with a live DJ and a banner that read “Dance is not a Crime,” this was not your parents’ May Day march. It represents both the transformation in protest culture and the consciousness of the recession generation.

According to the Twitter buzz, police estimated 300 participants, while the organizers estimated 170.[40] Widely recognized as the busiest train station in Tokyo (and therefore Japan), Shinjuku teems with people, especially east of the station in the plaza in front of the landmark Alta Studio, where demonstrations like this are held precisely because of the many passersby. At any given point, there were at least as many spectators as marchers (many recording it with portable devices) and seemingly almost as many police. The numbers may have been relatively small, but the march more than made up for that in spectacle: dance beat, sound car, the photogenic Amamiya wearing a lacy white baby-doll dress and carrying a bullhorn, several participants in cosplay (costume play) giant animal costumes, and a general celebration of nonconformity hardly dampened by the rain.

In figure 10.11, Amamiya has the bullhorn amid the lively crowd. The theme of the 2012 march was “The aspirations of a motley crew,” which focused on respecting diversity of background, nationality, sexuality, and schooling. First, the dance car led the march with a giant yellow sign on the back reading “DANCE IS NOT A CRIME.” Several dozen participants near the car danced rhythmically and sang along—sometimes to the DJ and sometimes to Amamiya’s calls. Chants included the danceable “Us Guys Don’t Just Do What We’re Told,” from the song by ECD.[41]

Amamiya called out “We oppose labor” within a string of phrases beginning with “We oppose” that also included “We oppose overtime,” “We oppose sexual harassment,” and, tellingly, “We oppose getting up early.” In fact, this resistance to labor is characteristic of the precariat. Guy Standing writes that “Besides labour insecurity and insecure social income, those in the precariat lack a work-based identity. When employed, they are in career-less jobs, without traditions of social memory, a feeling they belong to an occupational community steeped in stable practice, codes of ethics and norms of behaviors, reciprocity and fraternity.”[42] In a 2011 book on the rising freeter union movement in Japan, sociologist Hashiguchi Shōji (b. 1977) describes the movement in terms of the contradiction between “let us work” and “we won’t work.”[43]

Is it a coincidence that SABU’s remake of the Russia scene and the Indies’ May Day protests both suggest DDR? It may be. Street protests in Japan continue to transform in the vernacular of youth culture as documented by sociologist Mōri Yoshitaka (e.g., incorporating music and live DJs).[44] Takiji’s 1929 novella ends with considerable optimism despite the severe government crackdown and widespread arrest of leftists in March 1928 and April 1929. A 1953 film version ends with members of the imperial navy boarding the ship and gunning down everyone in an atrocious bloodbath, a critique of the tragic consequences of militarization still fresh in the early postwar period. Rereading—and rewriting and rescripting—The Crab Cannery Ship in twenty-first-century recessionary Japan allows for new endings, as the story is itself unfinished and requires the reader to imagine its continuation vis-à-vis the postscript. In 1929, Russia played a crucial role in the coming into consciousness of the workers in The Crab Cannery Ship. By contrast, in the way that the novella is reimagined for a twenty-first-century youth audience, Russia becomes phantasmic, if not entirely replaceable. In 1929, what was being affirmed was the possibility of a worker’s revolution. Now there is nostalgia for those jobs associated with preneoliberal security; at the same time, there are emerging forms of protest that oppose, among other things, labor itself. This 2009 film has an ambiguous ending. The men organize and learn the skills necessary to unionize and demand humane working conditions (we assume, for the viewers are not actually shown the demands). At the same time, the neobourgeois ideology of individual choice and individual action is also emphasized, suggesting a paternalistic intervention into the precariat’s apathy toward labor.

Notes

1. I follow the Japanese language practice of putting the family name, Kobayashi, before his personal name, Takiji. Also, following the literary practice in Japan, I call him Takiji.

2. The first partial translation appeared shortly after the author's death by torture while under interrogation in 1933 in The Cannery Boat by Kobayashi Takiji and Other Japanese Short Stories, translation anonymous [Max Bickerton] (New York: International Publishers, 1933). A second English translation was published in 1973: "The Factory Ship" and "The Absentee Landlord," translated by Frank Motofuji (Seattle: University of Washington Press, 1973). Both of these earlier translations are out of print, but a new 2013 translation has brought it back into print in English: The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle, translated by Željko Cipriš (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2013). In addition to Cipriš's translation, which includes two additional novellas by Takiji, there are six more of his pieces forthcoming in a volume coedited by Heather Bowen-Struyk and Norma Field, For Dignity, Justice, and Revolution: An Anthology of Japanese Proletarian Literature (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 2015).

3. For an excellent account of the boom, see Norma Field, "Commercial Appetite and Human Need: The Accidental and Fated Revival of Kobayashi Takiji's Cannery Ship," Asia-Pacific Journal, February 22, 2009, http://www.japanfocus.org/-norma-field/3058. The seeds of my essay can be found in my early reflections on The Crab Cannery Ship boom in Heather Bowen-Struyk, "Why a Boom in Proletarian Literature in Japan? The Kobayashi Takiji Memorial and the Factory Ship," Asia-Pacific Journal, June 29, 2009, http://japanfocus.org/-Heather-Bowen_Struyk/3180.

4. The four manga versions are all graphic novels: Yes Koike, Gekiga kani kōsen: Haō no fune [The Graphic Novel Crab Cannery Ship: A Ship Ruled by Force] (Tokyo: Takarajimasha, 2008); Variety Art Works, Kani kōsen: Manga de dokuha [The Crab Cannery Ship: Read It All in Manga] (Tokyo: East Press, 2007); Hara Keiichirō, Kani kōsen [The Crab Cannery Ship] (Tokyo: Shinchōsha, 2008); and Fujio Gō, Manga kani kōsen: 30 pun de yomeru . . . daigakusei no tame no [The Manga Crab Cannery Ship: For College Students to Read in 30 Minutes] (Tokyo: Shirakaba Bungakukan Takiji Raiburarī, 2006).

5. "Keikyō: 'Kani kōsuru' 'Maru de kani kō da na' . . . Hiseikikoyō no wakamono ga nageku kakushakai" [The Situation: "To Do Crab Cannery" and "This Is Just like The Crab Cannery!"—Irregularly Employed Youth Cry Out against the Divided Society], Okinawa Times, December 5, 2008, http://anchorage.2ch.net/test/read.cgi/bizplus/1228460670/.

6. SABU (aka Tanaka Hiroyuki), dir. Kani kōsen [The Crab Cannery Ship] (Tōei Video, 2009), DVD. The Japanese trailer is available at YouTube, http://www.youtube.com/watch?v=qmJ6DCXIM40.

7. Douglas McGray, "Japan's Gross National Cool," Foreign Policy, May 1, 2002, http://www.foreignpolicy.com/articles/2002/05/01/japans_gross_national_cool

8. Furiita hyōrū: Monotsukuri no genba de [Freeters Adrift: Where Things Are Made], NHK documentary, first broadcast February 5, 2005.

9. Kukhee Choo, "Nationalizing 'Cool': Japan's Global Promotion of the Content Industry," in Popular Culture and the State in East and Southeast Asia, edited by Nissin Otmazgin and Eyal Ben-Ari (London: Routledge, 2012), 85.

10. Anne Allison, "The Cool Brand, Affective Activism and Japanese Youth," Theory Culture & Society 26, nos. 2–3 (March–May 2009): 91.

12. Guy Standing, The Precariat: The New Dangerous Class (London: Bloomsbury Academic, 2011), 10.

14. Translations from Takiji Kobayashi, The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle, translated by Željko Cipriš (Honolulu: University of Hawai'i Press, 2013), 25–26.

16. "Kani kōsen" [The Crab Cannery Ship], Senki (May 1929): 141–88 and (June 1929): 128–57.

17. For more on censorship and redaction, see Jonathon Abel, Redacted: The Archives of Censorship in Transwar Japan (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2012).

18. "Since 1927: Kinokuniya shoten no ayumi" [Kinokuniya company history from 1927], Kinokuniya Web Store, http://www.kinokuniya.co.jp/company/history.html.

19. Kobayashi, The Crab Cannery Ship and Other Novels of Struggle, 46.

22. Takiji Library, http://www.takiji-library.jp.

23. Sano Chikara, "Go-aisatsu" [Greetings], in 2008 Okkusufodo Kobayashi Takiji kinen shinpojiumu ronbunshu: Takiji no shiten kara mita shintai chiiki kyoiku [Report of the 2008 Kobayashi Takiji Memorial Symposium at Oxford: Body, Region, and Education], 3–4 (Otaru: Otaru University of Commerce and Kinokuniya, 2009).

24. Norma Field, "Commercial Appetite and Human Need: The Accidental and Fated Revival of Kobayashi Takiji's Cannery Ship," Asia-Pacific Journal, February 22, 2009, http://www.japanfocus.org/-norma-field/3058.

26. Amamiya Karin and Takahashi Gen'ichirō, "Kakusa shakai: 08nen no kibō o tou; Takahashi Gen'ichirō-san—Amamiya Karin-san taidan" [Income Disparity Society: Exploring the Aspirations of '08; A Dialogue between Takahashi Gen'ichirō and Amamiya Karin], Mainichi Shimbun [News], Tokyo asakan [morning edition] (January 8, 2008).

27. Atarashii kamisama [The New God], directed by Tsuchiya Yutaka, DVD, 1999.

28. Amamiya Karin, "Suffering Forces Us to Think beyond the Right-Left Barrier," translated by Jodie Beck, in Mechademia 5: Fanthropologies (Minneapolis and London: University of Minnesota Press, 2010), 254. Original publication: Amamiya Karin, "Ikitzurasa ga koesaseru 'sayū' no kakine: Baburu no hōkaigo no 'yakenohara' nite," Migi to hidari wa te o musuberu ka [Can the Left and Right Join Hands?], special issue of Rosujene/Lost Generation (May 2008): 44–53.

29. See Allison, "The Cool Brand"; Michael Hardt, "Affective Labour," Generation Online, 2008, http://www.generation-online.org/p/fp_affectivelabour.htm.

30. Amamiya Karin, "Kaisetsu: Gendai ni kaerisaku Kani kōsen no sakebi" [Essay: The Cry of The Crab Cannery Ship's Revival], in Kobayashi Takiji, Kani kōsen (Tokyo: Kin'yōbi, 2008), 146. Translations are mine.

37. Allison, "The Cool Brand," 90.

38. Saitō Tamaki, Beautiful Fighting Girl, translated by J. Keith Vincent and Dawn Lawson (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2011), 30.

39. Miriam Bratu Hansen, "The Mass Production of the Senses: Classical Cinema as Vernacular Modernism," Modernism/Modernity 6 (April 1999): 59–77.

40. Tweet by @radiomikan, May 3, 2012.

41. For more on this song and rave demo culture in Tokyo, see Sharon Hayashi and Anne McKnight, "Good-bye Kitty, Hello War: The Tactics of Spectacle and New Youth Movements in Urban Japan," positions: east asia cultures critique 13, no. 1 (Spring 2005): 87–113.

42. Standing, The Precariat, 12.

43. Hashiguchi Shōji, Wakamono no rōdō undō: "Hatarakaserō" to "Hataranakai" no shakaigaku [Labor Movements of the Youth: Sociology of "Let Us Work" and "We Do Not Work"] (Tokyo: Seikatsu Shoin, 2011).

44. Mōri Yoshitaka, Sutoriito no shisō: tenkanki to shite no 1990 nendai [Theory of the Streets: The 1990s as an Age of Transformation] (Tokyo: NHK Books: 2009).