Lineages of the Literary Left: Essays in Honor of Alan M. Wald

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

7. Dancing for Stalin: Pauline Koner's "Russian Days" and the Question of Stalinism

Pauline Koner (1912–2001), an American dancer, choreographer, and student of former Ballet Russes choreographer Michel Fokine, arrived in Moscow on December 16, 1934, to begin a two-month tour of the Soviet Union at the invitation of the Soviet government. Koner, as she often told people, the “first American dancer officially invited to the Soviet Union since Isadora Duncan,” had moved to the “new Russia” in 1921 to start a dance school.[1] Koner’s stay in Russia, extended from two months to nearly two years, echoed the experience of that pioneering American dancer in significant ways.

Koner’s arrival in Bolshevik Russia coincided with the funeral of Sergei Kirov, the popular Leningrad party chief and Joseph Stalin’s potential successor. Koner watched the event from her hotel window.[2] As she peered through the glass at the “sad but beautiful spectacle,” she remarked to herself that Russia had lost a “great person.” Notwithstanding this quiet tribute in her diary, Koner was barely aware of the Kirov murder’s significance, nor could she have been.[3]

Thirty years earlier, Isadora Duncan’s initial visit to Russia was also framed through the lens of a funeral that portended revolutionary changes. Duncan claimed to have arrived in St. Petersburg in January of 1905 on the night of a funeral cortege for victims of the Bloody Sunday massacre, in which czarist troops attacked thousands of peaceful protestors. Duncan insisted that the sight of the funeral cortege convinced her to commit “[herself] and [her] forces to the service of the people and the down-trodden.” Indeed, she remarked, “if I had never seen it, all my life would have been different.”[4]

While the Bloody Sunday massacre launched the 1905 revolution (which failed but unleashed the energies that would culminate in 1917), Kirov’s assassination would launch a very different kind of revolution. The Kirov assassination became the pretext for Stalin’s launch of the Great Terror, in which more than a million people were accused of espionage, sabotage, and other anti-Soviet crimes, sent to prison camps, and murdered.[5] The coincidence of Kirov’s murder with Koner’s arrival in Moscow eerily foreshadowed the complicated dynamics of the Russian chapter in Koner’s career.

Koner was twenty-two when she arrived in Moscow, exactly half as old as Duncan had been when at forty-four she came at the invitation of the Soviet government to live in the “new Russia,” but close to Duncan’s age at the time of her initial trip to czarist Russia in 1904–5. That visit and tours in 1908 and 1913 had earned Duncan a major following among imperial Russia’s artistic avant-garde.[6] However, during the years Duncan actually made her home in Russia (from 1921 to 1924), her vision of liberating new Russia’s youths through Duncan-style dance was largely unrealized. Her Moscow school was never adequately supported by the Soviet government, her dance was no longer appreciated (Soviet critics called her overweight, past her prime, and out of touch with the new ethos) and her love life was a disaster. (She married and within two years divorced the prominent Russian poet Sergei Esenin, who drank too much, abused Duncan, and eventually committed suicide).[7]

In contrast, we might say that Koner’s Russian days were a great success, professionally and personally. She had more work than she could physically manage at a time when dancers in the United States were struggling under the impact of the Great Depression. Her dances were lauded by Russian critics and audiences. She taught at the Soviet Union’s most prominent and prestigious institute of “physical culture,” and her plans to establish her own dance group “to complete what Duncan began” appeared close to realization.[8] Finally, Koner discovered “physical love” with a man who respected her work and inspired her creatively.

But looked at in another way, Koner’s Soviet sojourn failed to live up to its promise. True, Koner found professional success and love in Russia, but only at a high cost. She fell for a married man who had no intention of leaving his wife. Far more troubling, Koner’s success was ultimately predicated on her accommodation to a Stalinist ethos. While in the Soviet Union, her dance and choreography gradually shifted from largely apolitical “ethnic” dances toward more political work as she, like Duncan before her, aimed to produce dances for Russia’s “new youth.”[9] In the final weeks of Koner’s Soviet sojourn, she choreographed and performed a militaristic dance, witnessed by Stalin himself, as part of a seventy thousand–person physical culture parade held in Leningrad.

While Duncan would not live to write about her “Russian days,” she did nothing during those days that she would later regret. Koner, in contrast, never fully acknowledged to American audiences what was clearly the culmination of her work in the Soviet Union. She was not well versed in “proletarian dance art” and only became (marginally) involved in the flourishing revolutionary dance movement in the United States after she returned from Russia.[10] It is Koner’s simultaneous “not knowing” and active involvement, her literal performance of Stalinism and not just her coincidental arrival at the moment of Kirov’s death, that make her a useful vehicle for thinking about the question of Stalinism for Americans who put their confidence in the Soviet project.

Duncan’s characterization of dance as a spiritual or religious practice makes it an apt expressive mode for exploring the relationship that many people had to the Soviet Union, one that was grounded more in instinctive faith than in rational logic. “I salute the birth of the future international community of love,” Duncan said of postrevolutionary Russia. “A new world, a newly created mankind; the destruction of the old world of class injustice, and the creation of a new world of equal opportunity.” She aimed to bring her dance, “a high religious art,” to this new mecca, where her “dancer of the future . . . whose body and soul have grown so harmoniously together that the natural language of the soul will have become the movement of the body” could help fulfill “the ideals of the new world.”[11]

After 1917, Duncan and Koner were among the legions of American “new women” who closely watched events in the “new Russia” and, increasingly, went to experience the “new life” themselves: from suffragists celebrating women’s franchise under the new regime following the revolution to reformers noting the Soviet provisions for maternal and child health to rebels against constricting sexual mores who marveled over the Soviet Union’s free abortion and easy divorce.[12] But by the time of Koner’s arrival in the mid-1930s, conservatives as well as a fair number of socialists and dissident Marxists associated Stalin’s regime with violence and oppression. Even so, for a large part of the Left as well as many liberals, the Soviet Union still resonated with a revolutionary sense of democratic possibility and particularly with new possibilities for women.[13] This attitude persisted despite the fact that unexplained disappearances, including disappearing Americans, were already a regular feature of Soviet life, and violent retribution was an accepted mode of dealing with so-called enemies of the revolution—and had been since 1917.[14]

By the 1930s, optimism about the “new Russia” required greater and greater leaps of faith or willed ignorance. As Milly Bennett, a writer for Soviet Russia’s first English-language newspaper, the Moscow News, flippantly wrote to a friend in 1932, “the thing you have to do about Russia is what you do about any other ‘faith.’ You set your heart to know they are right . . . and then, when you see things that shudder your bones, you close your eyes and say . . . ‘facts are not important.'”[15]

What are the implications of ignoring “the facts” of Stalin’s reign? Or of glorifying the man himself, even if that glorification was only a gesture, not something heartfelt? Alan Wald’s scholarship has grappled with the legacy of Stalinism for the American Left and has offered a model for nuanced usage of a term that is often uncritically employed. In the context of US politics, “Stalinist” is often used as a blanket term for followers of the Communist Party USA (CPUSA) and, more specifically, to allude to their dogmatic qualities. Wald’s work suggests that the term needs to be understood with greater precision to describe the way in which the CPUSA came to serve as “a bureaucratic instrument of the Thermidorean reaction in the Soviet Union” while recognizing that it was far from being entirely that for many committed activists in its ranks.[16] Wald argues that the CPUSA was both genuinely revolutionary in some respects—for example, in its efforts on behalf of workers and the unemployed and in its commitment to racial equality—but in other respects the Party bred ideological rigidity and undemocratic practices. Even more seriously, unquestioning loyalty to the Soviet Union among a large swath of the American Left led to widespread disavowal of and even justifications for state-sanctioned terror and repression. In this respect, Americans actually in Russia make for some of the most complicated case studies in Stalinism, for in this case the term is not simply an abstraction employed by opponents of the Popular Front milieu in the United States.

In the Soviet context, Stalinism meant something very specific, as David Hoffman, a historian of Russia, explains:

Stalinism can be defined as a set of tenets, policies, and practices instituted by the Soviet government during the years in which Stalin was in power, 1928–1953. It was characterized by extreme coercion employed for the purpose of economic and social transformation. Among the particular features of Stalinism were the abolition of private property and free trade; the collectivization of agriculture; a planned, state-run economy and rapid industrialization; the wholesale liquidation of so-called exploiting classes, involving massive deportation and incarcerations; large-scale political terror against alleged enemies, including those within the Communist Party itself; a cult of personality deifying Stalin; and Stalin’s virtually unlimited dictatorship over the country.[17]

In the Soviet context, an ethos of paranoia, fear, secrecy, and ideological rigidity defined the terms of daily life, particularly for Soviet citizens, to a large extent.

Even so, significant numbers of Americans of varying political persuasions (many of them not card-carrying members of the Communist Party) sought a kind of redemption in Soviet Russia.[18] “Dupe” seems both inadequate and inaccurate as a label for fellow travelers such as Koner. Echoing Duncan’s notion of dance as religious expression, Koner told herself that she wanted to create the “New Soviet Dance,” a “great new art” that would communicate “the triumphant joy the victory and hope of the new Russian Soviet life.” And indeed, she tried to choreograph and perform dances that would communicate the vital spirit she felt that she witnessed among young people in the Soviet Union, people raised to believe in a socialist future. But by reading her diary, one gets the sense that although she loved working with Russian young people, what she really wanted was to develop as an artist, and she had found in Russia the opportunity for that to happen beyond anything she’d ever experienced. As she wrote in her diary within weeks after her arrival, “Today brought a great event in my life. My dancing and theories are taken seriously.”[19]

The militarist performance with which Koner concluded her Russian days represented, above all, a desire to display her skills as a dancer and choreographer before a large audience filled with important people. But she also was deeply energized by her students, particularly the young women. As Roger Markwick notes of the generation who came of age in the 1930s, “this generation combined a sentimental, ‘feminine’ commitment to marriage, motherhood and Motherland with an inherent belief that they were ‘strong women’ and equal partners in the heroic Soviet project with men.'”[20] Even as the Stalinist regime emphasized motherhood and family life (outlawing abortion and divorce in 1936), rather than driving women out of the public sphere and into the home, both necessity and enthusiasm kept women in the workplace as well. Young women were widely celebrated in Stalinist culture as full partners in the Soviet projects of industrialization and mobilization for a war that seemed increasingly imminent. Koner, not much older than her students, was likely enthralled by the “cult of the heroine” that showcased the new Soviet woman “as an emancipated representative of progress and modernization.”[21]

Why dance as a medium for considering Americans’ relationship to Stalinism? Dance is written into the body; it is a language believed to be capable of communicating otherwise inexpressible inner feelings and truths. This notion, drawn from the ideas of French music theorist François Delsarte, who at the turn of the century developed a system of movements that he claimed corresponded to specific emotional states, informed Isadora Duncan’s movement and her claims for “the dance’s” power.[22] US dance critic John Martin’s theory of metakinesis updated Delsarte to suggest dance’s uniquely expressive properties: “Because of the inherent contagion of bodily movement, which makes the onlooker feel sympathetically in his own musculature the exertions he sees in somebody else’s musculature, the dancer is able to convey through movement the most intangible emotional experience.”[23]

Soviet theater director Vsevolod Meyerhold incorporated Delsartian thinking into his system of actor training, called biomechanics, that was based on the idea that “all psychological states are determined by specific physiological processes.”[24] Meyerhold was a proponent of physical culture—an umbrella term for an array of physical education in the Soviet Union but one that emphasized the cultural dimensions of movement—and especially favored gymnastics. According to David Hoffman, “Soviet authorities . . . sought to shape the body as well as the mind, and in fact believed that physical exercise was essential to mental health and the transformation of consciousness. . . . Gymnastics emerged as a favored form of physical culture precisely because it taught not only discipline and control but also synchronization through group exercises believed to be capable of integrating and uniting individuals.”[25]

Although Delsarte’s ideas were influential in the Soviet Union, their impact was felt more directly in theater and film than in dance proper, primarily because of ballet’s enduring place in Russian culture. What this meant was that American dancers, though cognizant of their debt to Russia’s great traditions in dance (from the Ballets Russes to the performances of Anna Pavlova), believed that when it came specifically to modern dance technique, Russians had more to learn than to teach. “Revolutionary dancers” in the United States, like revolutionary writers, actors, artists, and filmmakers, closely watched developments in Russia after the Bolshevik Revolution, but they considered modern dance—a form far more popular in the United States than in the Soviet Union—to be more in tune with the new Soviet society than ballet was. Consequently, American dancers believed that they could make a unique contribution to further revolutionary developments in the arts.

Duncan, whose expressive dance is generally seen as the basis for modern dance, had envisioned dancers whose movements proclaimed the “freedom of woman.” And she hoped to see her vision realized in a nation, Soviet Russia, that proclaimed “all humanity”—or at least all workers—as its constituency. However, Duncanism, seen as too ideologically amorphous, had lost its hold in Russia, arguably by the time Duncan settled there, but certainly by the late 1920s. As dance scholar Irina Sirotkina explains, by this time “The new aesthetic ideal was biomechanical exercises for healthy-looking workers and athletes, and not wave-like movements for girls in tunics.”[26]

“Physical culture” became in the Soviet Union one of the only arenas for movements that in the United States might be classed as modern dance. Thus, it was not coincidental that Koner could only develop as a choreographer in the Soviet Union (and not simply as a dancer) once she became involved with the Lesgaft Institute of Physical Culture, an association that put her squarely within the Stalinist project of militarizing Soviet youths.[27]

A number of prominent modern dancers involved with the revolutionary dance movement in the United States, among them Edith Segal, Anna Sokolow, Mignon Garland, and Dhimah Meidman (all Jewish), made pilgrimages to Soviet Russia in the 1930s. In that decade, the revolutionary dance movement represented a significant trend within modern dance more broadly. For almost all these women, Isadora’s influence was inescapable. Young Jewish women who studied “Duncan dance” at settlement houses in the 1910s became leading lights in the revolutionary dance movement in the 1930s; once in Russia, those who practiced “plastic dance” understood that they were being seen as inheritors of Duncan’s lineage.[28]

Koner was of the same generation as Segal, Sokolow, and other leading figures in the revolutionary dance movement that thrived in New York City beginning in the 1930s, but she was only tangentially connected to it. (Koner performed in a number of shows sponsored by groups associated with the Left after her Russian tour, but on the whole she claimed to be more interested in creating art than in creating or performing “socially conscious works.”) Though not specifically trained in Duncan-style dance, Koner recognized Duncan as an early influence and, as noted above, consciously imagined herself to be “complet[ing] what Duncan began” in the Soviet Union.[29] Koner was the daughter of secular Russian Jewish immigrants to the United States and grew up in the generally socialist milieu that encompassed a large proportion of immigrant Jews in New York City in the early twentieth century. Her father, a lawyer, developed a medical plan for the Workmen’s Circle, a Jewish socialist fraternal organization founded in 1900.[30] In addition to ballet training with the Russian émigré Michel Fokine, Koner studied Spanish dance with Angel Casino, a well-known teacher of what was then a popular style of dance. At age seventeen Koner had toured with Michio Ito, a dancer from Japan who had been influenced by Duncan and the Ballet Russes (both of whom he saw in Europe) and by eurhythmics, a system of rhythmic movement that, like Delsartism, emphasizes kinesthetic awareness. Koner’s New York solo concert debut (in 1930) was with another Japanese dancer, Yeichi Nimura, whose training in ballet and Spanish dance complemented his dance adaptations of traditional Japanese elements.[31]

Koner’s eclectic training, exotic looks (she had long dark hair, olive skin, and high cheekbones), and tremendous adaptability launched her reputation as an ethnographic or neoethnic dancer, performing dances based on a variety of traditions, including many with a Far Eastern flavor. In 1932 and 1933, she spent nine months studying and dancing in Egypt and Palestine. A long-running interest in the East and in ancient civilizations drew her to Egypt, but she took a special interest in Palestine because of her Jewishness. Tel Aviv in the early 1930s was a “city of pioneers”: there, alongside orthodox Jews praying, Koner saw “young settlers from the kibbutzim, energetic, sunburned, work-steeled bodies, and minds honed by the difficulties of survival—a look of life in their eyes and a warmth in their heart. . . . The atmosphere breathed enthusiasm, hope, and progress.” Koner “felt vibrantly free, as if [she] had shed an invisible layer of skin, and proud of [her] Jewishness.”[32]

Although Koner felt proudly Jewish while in Palestine, she performed “Jewish” dances—among the many styles in her repertoire—less as a Jew performing her own heritage and more as ethnographic interpretation. According to dance scholar Rebecca Rossen, “whether she was performing as an Indian priestess in Nilamani (1930), a Javanese temple dancer in Altar Piece (1930), or a Hasidic boy in Chassidic Song and Dance (1932), Koner separated herself from the ethnic material she used by presenting her work as creative interpretation and not authentic replication.” Like Ruth St. Denis (a contemporary of Duncan’s), Koner performed such dances in order to demonstrate her own universality, “or her ability to represent a variety of Others.”[33]

For many Jewish Americans with Russian roots, both Palestine and the Soviet Union were popular sites of “magic pilgrimage,” both homelands of a sort with utopian promise, both places where “new people” were being created along with new civilizations.[34] While Palestine called as a Jewish homeland, the Soviet Union offered Jews with roots in Russia a chance to reformulate, now in terms of “class and political solidarity,” their emotional connection to a land once known for its brutal oppression of Jews.[35] Indeed for Jews, as for African Americans, part of the Soviet Union’s attraction was the possibility of having distinctions such as race or ethnicity no longer matter.[36]

Koner would not consciously go to Russia as a Jew, nor was she even particularly committed to the Soviet project (of “changing man” and reorganizing social and economic relations)—at least at first.[37] On a visit to the Soviet Union in 1934 for their twenty-fifth wedding anniversary that year, Koner’s parents had presented her press book to the Soviet concert bureau. Possibly because of Koner’s training with Fokine, officials were enthusiastic and almost immediately invited Koner to dance in the Soviet Union, offering her a round-trip ticket and a two-month contract with excellent pay. In the midst of the Depression, the offer sounded too good to be true.[38] Moreover, both the ethnic variety encompassed by the Soviet Union and the ostensible universality of Communist internationalism promised to take Koner’s work in exciting new directions.

Over her two years in the Soviet Union, Koner had so many engagements she could barely keep up with her own schedule. Within the first few weeks she had performed a special concert for leading artists in Moscow with great success: “Now everyone is talking about me,” she wrote in her diary. She met many of the great figures of the Soviet arts—Sergei Eisenstein, Vsevolod Meyerhold, Vsevolod Pudovkin, and others—and all of them took her work seriously, offering pointed commentary and welcoming her into a community of artists. In Leningrad at the Marinsky Ballet School she gave lessons in “oriental style,” “Spanish style,” “Fokine style,” and her own style. “People were thrilled,” Koner remarked in her diary as she marveled at her own success. She saw non-Russian minorities dance in their native styles, finding dances such as “the hunter’s dance, the duck dance, and the shaman” to be “primitive but interesting.” In contrast, she saw Russian attempts at modern dance as “banal” and without “nuance.” Still, she had never experienced such “serious active interest in forwarding the dance art,” and she felt that she had something unique to offer. “Russia needs a new form in its dancing. It knows what it wants as far as theme is concerned but its form is outdated. It’s up to me to get those together and I shall.”[39] As her two months were nearing their end, she decided that she wanted to stay in Russia: “I am being convinced slowly but surely that Russia is the place for me,” she wrote in her diary. “The place where I can mold my future. It has the inspiration I need the possibilities I need. I am planning to start a group here, to start the new Russian dance. Perhaps my fate has all my life guided me to this point. . . . I am filled with new ideas and hopes.”[40]

While she found Soviet dance less than inspiring, Koner was deeply affected by other aspects of life in Russia. For instance, she was entranced by her visit to a factory: by the immensity of the machines and the workers’ pride, interest, and enthusiasm. And she was deeply moved by the spectacle of a May Day parade, by the “electric currents vibrat[ing] in the air” as Stalin passed and by the rhythmic movements of marchers through the square.[41]

As Koner came into her own professionally, she also discovered a new kind of love with the successful Soviet filmmaker Pudovkin, a married man twenty years her senior; their relationship was physical, intellectual, and creative: “He is a person whom I can admire, respect, and learn from,” she wrote in her diary. “I do not feel as though I am only body only something to give sensation. I am a person am respected as such and an artist. To talk! To lose oneself in a wild enthusiasm! In the hot surging flame of creation!”[42]

After a year of touring, Koner was invited to teach at the Lesgaft Institute of Physical Culture in Leningrad. This work, though exhausting, was energizing, “stimulating, and creative…. The pupils in Leningrad are young and fresh, a new type of youth, Soviet youth,” she wrote in her diary. “Full of enthusiasm, life, and energy, full of a desire to work and strength to accomplish. They are bubbling with ambition. I shall be able to create interesting compositions with them and hope to form a permanent group, a New Soviet Group.”[43]

The Lesgaft students inspired Koner to choreograph her first dance in Soviet Russia: “The theme is the triumphant joy the victory and hope of the new Russian Soviet life. My subject is the red flag. I do not dance one who sees carries or feels the flag, no, I dance the flag itself. All its movement and all for which it stands.” Noting this new composition, she began to seriously contemplate: “What will the new Soviet dance be?” Her notes here are choppy, confused: “find the definite themes such as the hope the health the youth the happiness of Soviet form…feeling of vigor delight of the new generation their desire to learn to grow to go ever higher and accomplish more. Yes that is the proper line to take.” Yet Koner’s certitude crumbled as she admitted almost in the same breath that her emotional state is “very bad,” that she has realized the “impossibility” of her love for Pudovkin.[44] Her work became a respite from these emotions, but she also found it hard to separate the two, especially given Pudovkin’s influence on her work.

After one of the first evenings Koner spent with Pudovkin (before their affair began) and his colleague, the scenarist Natan Zarchi, Koner had written of Pudovkin in her diary: “He is a strange, hysterical, but brilliant person and I may be able to get much inspiration from him.”[45] Ten days later, she noted the “tremendous impression” she made on Pudovkin during a concert that evening,[46] and she described the discussion she had later that evening with him, Zarchi, and her interpreter Valia:

We have discovered an interesting form of dance using contemporary dynamic music—legato move pause legato

dynamic pause

dynamic shorter—legato

legato—legato

pause

dynamic dynamic

final crescendo.

We also discussed thematic material and how to attack thematic material. I am inspired and thrilled with new impetus to work. I am beginning to orient myself to this mode and have a strong notion that I shall spend a much longer period in Russia than I originally planned perhaps I shall even make my headquarters here.[47]

Two days later, Koner spent much of the day reading Dalcroze’s book Eurythmics Art and Education, noting to herself, “I find that I have instinctively been doing what Dalcroze advocates,” and adding, “I am being convinced slowly but surely that Russia is the place for me.”[48]

Emile Jacques-Dalcroze and François Delsarte were tremendously important to Soviet filmmakers, including Pudovkin, who, like other film and theater directors, drew upon Dalcroze’s system of rhythmic gymnastics to understand ways in which sound and gestures could most effectively communicate human emotions.[49] Pudovkin likely recommended the book to Koner in order that she might think more systematically about the relationship between music, movement, and emotion (i.e., “thematic material”). Indeed, Pudovkin, who emerged as one of the leading filmmakers of the Stalin era (he was awarded the Stalin Prize in 1951) and whom scholars have since accused of “devot[ing] his great talent wholly to the service of the Party,” proved instrumental in convincing Koner that her work should forward the goals of the revolution (i.e., should “view the new victory as your victory”).[50]

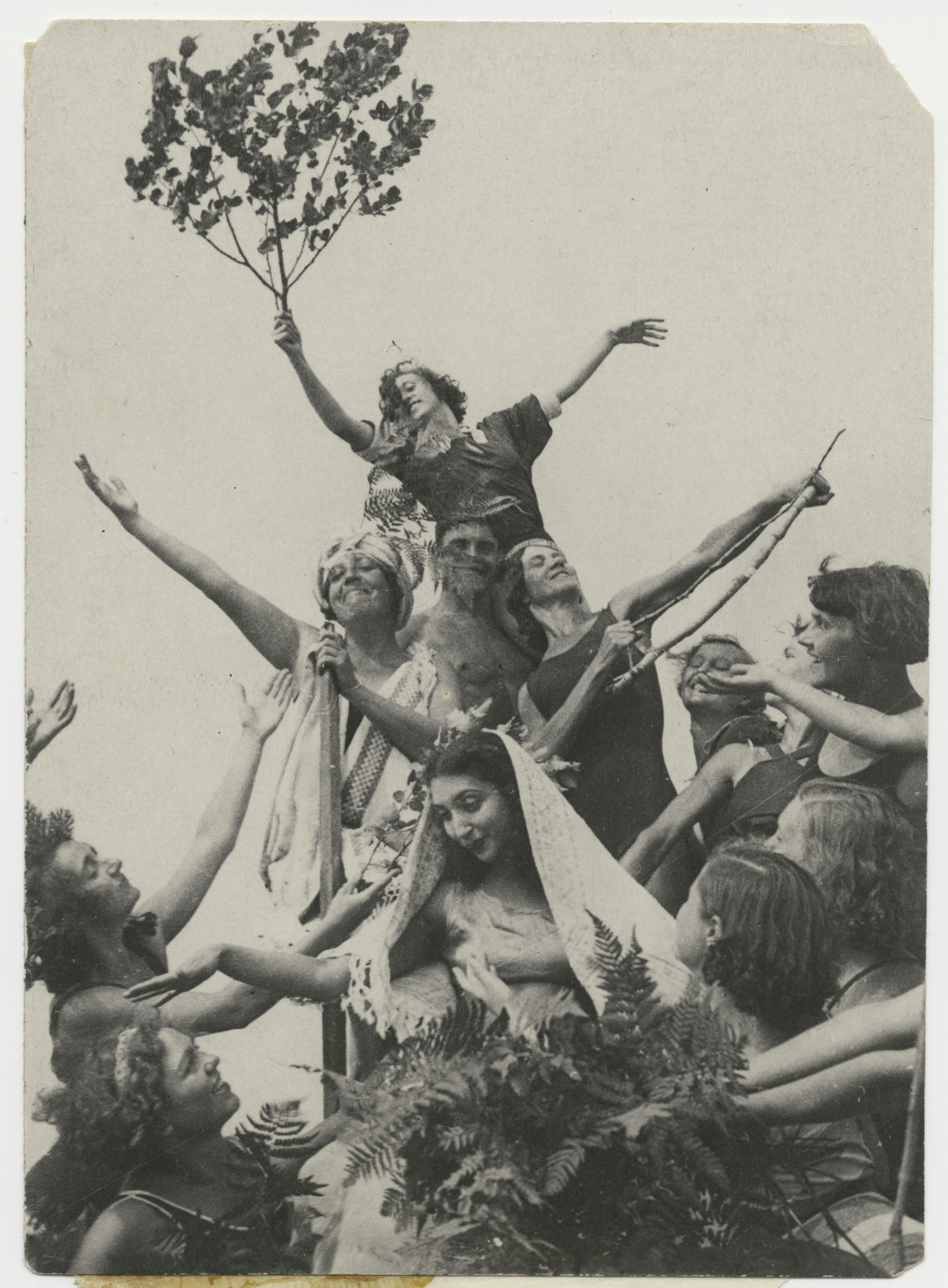

A Leningrad newspaper describes Koner teaching “machine dances” (a variety of the dances pioneered by the Soviet composer Nikolai Foregger in which bodies mimic the movement of machines), but extant photographs point to the fact that Koner also embraced a more organic vision for the “new Soviet dance.” Images from what appears to be a rehearsal on the Leningrad beach show young people in bathing suits moving in unison or posed in evocative tableaux vivants. Their collective gestures suggest freedom, joy, possibility, and dynamism, echoing the style cultivated by German ausdruckstanz (expressive dance) and also echoing Pudovkin’s shots of expansive spaces with grasses swaying in the wind. Formations incorporate a primitively fashioned bow and arrow, sheets, and a crown of flowers worn by Koner. Dancers reach toward the sky, their arms gesturally repeating the leafy branches that several students grasp. Koner also dances solo, improvising for her students or perhaps for the photographer: she stretches, reaches, lunges, twists, kicks, bends, leaps, and even spirals in midair. Here we see something like an accommodation between Duncan-style “plastic dance” and the new Soviet physical culture.

The culmination of Koner’s work in the Soviet Union was choreographing a “mass dance” as part of a seventy thousand–person Physical Culture parade that took place in Leningrad in July 1936, with Stalin himself in the audience. Physical Culture parades were a typical feature of Soviet mass meetings and celebrations, visible manifestations of youthful fitness and discipline.[51] This was Koner’s first attempt at “group choreography.” She recognized that it could mean “the beginning of an important phase in my career.” But more important, she told herself, “it means interesting work for myself.”[52] This was to be her “Dance of the New Youth.”

As suggested above, the position at the Lesgaft Institute for Physical Culture had placed Koner squarely within the only accepted arena for what might be called “modern dance” in the Soviet Union. Named for the “father” of physical education in Russia, Pyotre Lesgaft, a biologist, social reformer, and education theorist who gave special attention to sport as a vehicle for “women’s social emancipation,” the institute’s program embodied the hybrid projects of physical culture and women’s empowerment under Stalin. In the Stalin era, a principal aim of Lesgaft’s institute was to determine ways to “utilize physical exercise rationally to improve productivity,” a project that evolved to encompass physical culture’s emphasis, by the mid-1930s, on military preparation.[53] Physical culture was simultaneously a tool for cultivating “an individual with the harmonious development of mental and bodily strengths,” an instrument of building workers’ labor capacity, and a means of inculcating discipline and fitness for battle.[54] These were projects that many young Soviet women of the 1930s internalized as their own.[55]

Dance taught under the rubric of “physical culture” was to be collective, vigorous, and easily intelligible to the masses; these ideas inspired elements of the revolutionary dance movement in the United States but also echoed totalitarian mass dances of Nazi Germany, which converted ausdruckstanz into National Socialist spectacles.[56] In the Soviet Union, mass spectacles became increasingly commonplace, as a “new outbreak of festivity” accompanied intensification of “the purges and political repression of the Soviet elite” and as “most of the Soviet population struggled with poverty and deprivation.”[57] But we would be wrong to assume that the massive demonstrations of collective unity under Stalin were entirely orchestrated by Soviet authorities without the consent of those performing. Recent scholarship on “Soviet subjectivities” emphasizes the ways in which Stalinism “gave common people [in the Soviet Union] an uncommon opportunity to reflect on themselves and constitute their identities and a sense of subjectivity.”[58] This had particular importance for women. As suggested earlier, Stalinism produced a hybrid identity for young women growing up in the mid-1930s—that is, for the young women who would have been Koner’s pupils and her inspiration. On the one hand, women at this time were encouraged to embrace motherhood and marriage; on the other hand, stories of women’s successes—in such varied fields as “aviation, defense, agriculture, industry, and sports”—served “as a gendered justification of the modernity of the regime” but also held meaning for many young women, whose displays of strength, agility, flexibility, and rhythm in Physical Culture parades can be seen as scripted but authentic performances of attempts to embody the new Soviet woman.[59]

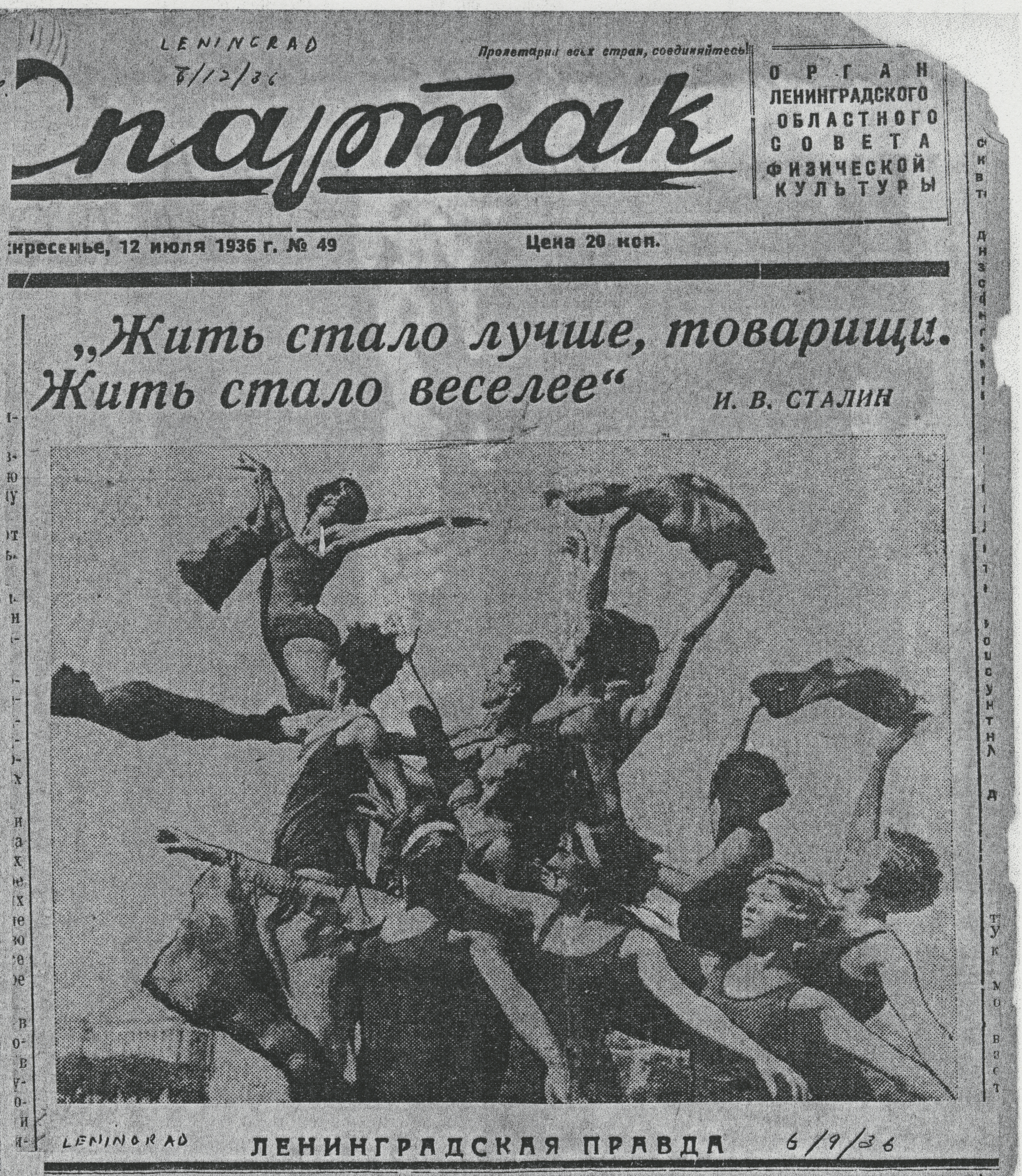

Koner’s memoir barely says anything about the actual performance of her “Dance of the New Youth,” and her Russian diary ends before the performance, stopping with the struggle she faced over the “ideological correctness” of having the dancers create a star formation. “I felt it symbolized the force [of] the new generation. . . . But everyone was extremely wary of chancing criticism,” she lamented in her memoir. She came up with an alternative that consisted, she said, of “just some brilliant movement that would catch the eye.”[60] There are a couple of news clippings in Koner’s scrapbook with photographs that made me wonder what, exactly, the performance entailed. One article in particular has a startling headline, recognizable even to someone whose Russian skills leave much to be desired. The Leningrad sports newspaper Spartak featured a photo of the Lesgaft students’ performance beneath Stalin’s famous words, now evoked only as an ironic reminder of his regime’s hypocrisy: “Life has become better comrades. Life has become joyful.”

Koner’s scrapbook also contains a clipping from Pravda. The date in the scrapbook is wrong, so at first I did not realize it described the 1936 Leningrad parade and her students’ performance, “Dance of the New Youth,” until I found the same clipping on microfilm as I was trying to find out more about the performance. Translating the article proved revealing. Pravda describes the dancers in their white, blue, yellow, orange, and red jerseys, whirling and then freezing in place on a giant Soviet emblem (the shape of the emblem is unspecified in the article). The performance is said to take on “new power” as Koner herself joined the Lesgaft students:

On the square rose a border pole. Suddenly there arrives a detachment of defenders of the Soviet borders. Unexpectedly, from an enclosure jumps a saboteur unit. With baited breath, all of the square expressed, through bayonets, the fervent courage of Soviet border guards. Here already gathered a handful of brave souls. The saboteurs rush the Soviet territory, but the new detachment of border guards turns out to cruelly resist them. The enemy is beaten. His pathetic remnants flee, etc. The victorious thunder “Oora!”[61]

Contrary to my own romantic impression of Koner and her students forming organic tableaux vivants on the Leningrad beach, I suddenly had to acknowledge and come to terms with the fact that Koner had choreographed and participated in a militaristic spectacle showing defenders of the Soviet borders crushing supposed saboteurs. “I had heard rumors that there were political trials going on, but knew very little about them,” Koner wrote in her memoir about her final months in Russia, in words that suggest her dissociation from Soviet political machinations. Later in her memoir, she mentions the “Stalin purge.” Nowhere does she describe the dance she choreographed for the parade, nor does her memoir mention that Stalin and other Bolshevik leaders were in the audience. All she says is that “the performance on the great Palace Square was quite a spectacle, and the newspaper reviews were excellent.”[62]

Koner left the Soviet Union immediately after the Physical Culture parade. She had been invited to continue her work at Lesgaft and had purchased a round-trip ticket with plans to return after a two-month visit with her family in the United States. But when it came time to go back, foreigners were no longer being admitted to the Soviet Union. Koner was disappointed, but she recognized that the real draw for her was Pudovkin, who could never fully give himself to her, for he still loved his wife.

As with many of the people Alan Wald has written about, Koner is not usually remembered as having any affiliation with the Left. The Federal Bureau of Investigation kept a file on her but noted only a handful of performances she gave in the late 1930s and early 1940s in the United States supporting the Soviet Union or Spain. But her “Russian days” clearly made their mark on her. She is open in her memoir about having had positive experiences in the Soviet Union and the cover of her popular dance technique textbook shows a picture of Koner dancing, seemingly hanging midair, against the backdrop of the Leningrad beach (see figure 7.3).[63] The implication would seem to be that this place and this moment represented the culmination of Koner’s technical development.

What, then, do we make of the massive performance for Stalin, Molotov, etc., that Koner choreographed or her desire to create the “New Soviet Dance”? Perhaps this entire project was, for her, another ethnographic act, an experiment performing another persona, undertaken not as an expression of faith but as a chance for “interesting work” that would advance an ambitious, talented young woman’s career. Or maybe, at least for a moment, she found something of the Stalinist project actually inspiring. As David Hoffman notes, while being “among the most repressive and violent [regimes] in all human history,” the Soviet Union “sought to cultivate educated, cultured citizens who would transcend petty-bourgeois instincts and contribute willingly to a harmonious social order.”[64] Couple this with the image of the Soviet “superwoman,” and for an outsider who was young and not fully cognizant of Stalinism’s terrible costs, dancing for Stalin could have been thrilling.[65]

Koner’s experiences point to the Soviet Union as a space of possibility for American women at a particular historical moment. But they also point to the limits of that possibility. Koner’s self-development as well as her professional development in the Soviet Union are ultimately inseparable from the fact that she made a conscious choice to choreograph and perform in ways that explicitly expressed support for an ethos that consolidated and rationalized repressive state power and unfathomable violence. In this context, Koner’s gravity-defying leaps on the Leningrad beach must be understood as likewise denying the weight of the history they embodied.

Notes

1. Pauline Koner, "Working with Doris Humphrey," Dance Chronicle 7, no. 3 (1984): 235.

2. Isadora Duncan, My Life (New York: Norton, 1995), 119; Pauline Koner, Russia diary, December 16, 1934, Pauline Koner Papers, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts (hereafter Koner Diary). Transcriptions from the diary retain their original punctuation.

3. Koner Diary, December 16, 1934.

4. Isadora Duncan, My Life (1927; reprint, New York: Norton, 1995), 119. In fact, Duncan arrived in St. Petersburg earlier (there are reviews in her papers of performances she gave in December 1904, and the massacre did not occur until January). See review in Novoya Vremya [New Times] (St. Peterburg), December 15, 1904, 13–14, translated by Natalia Roslaveva, Irma Duncan Collection of Isadora Duncan Materials, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts.

5. Matthew E. Lenoe, The Kirov Murder and Soviet History, translations by Matthew E. Lenoe, documents compiled by Mikhael Prozumenschikov (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2010). There is great debate among scholars concerning the number of people affected by the Great Terror. On the high end, Robert Conquest estimated that 20 million people were arrested, imprisoned, or killed. See Robert Conquest, The Great Terror: A Reassessment, 40th anniversary ed. (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2008), 485–86. Recent work based on archival evidence suggests that numbers were considerably lower though still very high: about 2.5 million people were arrested or imprisoned during the Great Terror (for both political and nonpolitical reasons), and nearly 700,000 were executed. Combined, 1.5 million people were either shot or died in prison or exile. Wendy Z. Goldman, Terror and Democracy in the Age of Stalin: The Social Dynamics of Repression (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2007), 5. I am especially indebted to Lisa Kirschenbaum, "Making Sense of Stalinism: Coercion and Enthusiasm," in Russia's Long Twentieth Century: Contested Voices, Memories, and Perspectives, edited by Choi Chatterjee, Deborah Field and Lisa Kirschenbaum (New York: Routledge, forthcoming). Kirschenbaum referred me to the seminal article, J. Arch Getty, Gabor T. Rittersporn, and Victor N. Zemskov, "Victims of the Soviet Penal System in the Pre-War Years: A First Approach on the Basis of Archival Evidence," American Historical Review 98, no. 4 (October 1993): 1017–49.

6. On Duncan's years in postrevolutionary Russia, see Irma Duncan and Allan Ross Macdougall, Isadora Duncan's Russian Days and Her Last Years in France (New York: Covici Friede, 1929); Ilya Schneider, Isadora Duncan: The Russian Years, translated by David Magarshack (New York: Harcourt, Brace & World, 1968). On Duncan's reception in Russia, especially in the early years, see Elizabeth Souritz, "Isadora Duncan's Influence on Dance in Russia," Dance Chronicle 18, no. 2 (1995): 281–91; T.S Kasatkina, E.IA. Surits, Aisedora: Gastroli v Rossii (Moskva: Izd-vo Artist, Rezhisser, Teatr, 1992).

7. Duncan and Macdougall, Isadora Duncan's Russian Days. The most scathing reviews of Duncan's performances are from the prominent Soviet critic V. Iving. See, for example, "Revolutionary Dances" (1924?), (manuscript), RGALI, f. 2694, op. 1, d. 4, Moscow. Translation by Andrey Bredstein.

8. Koner Diary, May 1–31, 1935.

9. She choreographed her first dance in Russia in December 1935, thinking specifically about creating "the New Soviet dance." Koner Diary, December 24, 1935.

10. Koner Diary, May 1–31, 1935.

11. Isadora Duncan, "Moscow Impressions," in The Art of the Dance, edited by Sheldon Cheney (New York: Theatre Arts, 1928), 110, 109. See also in the same volume Isadora Duncan, "The Dance of the Future," 54–63, and Isadora Duncan, "Dancing in Relation to Religion and Love," 121–27.

12. Little has been written on American women's romance with revolutionary Russia. See Choi Chatterjee, "'Odds and Ends of the Russian Revolution,' 1917–1920: Gender and American Travel Narratives," Journal of Women's History 20, no. 4 (2008): 10–33. On suffragists, see Julia L. Mickenberg, "Suffragettes and Soviets: American Feminists and the Specter of Revolutionary Russia," Journal of American History 100, no. 4 (March 2014): 1021–51. For a more fleshed-out discussion, see Julia L. Mickenberg, The New Woman Tries on Red: Russia in the American Feminist Imagination, 1905–1945 (Chicago: University of Chicago Press, forthcoming).

13. Christine Stansell describes revolutionary Russia as "a momentous fact" for the bohemian avant-garde in downtown New York and notes of these "Moderns" that "many poured their considerable faculties into endowing the new Soviet Union with an imaginative democracy that stretched across the world to include them." Christine Stansell, American Moderns: Bohemian New York and the Creation of a New Century (New York: Metropolitan Books, 2000), 321.

14. Conquest, The Great Terror, 3–22; Tim Tzouliadis, The Forsaken: An American Tragedy in Stalin's Russia (New York: Penguin, 2008).

15. Milly Bennett, letter to "Florence," January 27, 1932, Milly Bennett Papers, box 2, folder 1 (unidentified correspondence, 1932–1933), Hoover Library, Palo Alto, California.

16. Alan M. Wald, The New York Intellectuals: The Rise and Decline of the Anti-Stalinist Left from the 1930s to the 1980s (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 1987), 147. The relevant scholarship on the anti-Stalinist debate with Popular Front leftists is too large to recount, but see, for example, William L. O'Neill, A Better World: The Great Schism; Stalinism and American Intellectuals (New York: Simon and Schuster, 1982); Judy Kutulas, The Long War: The Intellectual People's Front and Anti-Stalinism, 1930–1940 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1995). See also Eugene Lyons, The Red Decade: The Stalinist Penetration of America (New York: Bobbs-Merrill, 1941).

17. David L. Hoffman, "Introduction: Interpretations of Stalinism," in Stalinism: The Essential Readings, edited by David L. Hoffman (Malvern, MA, and Oxford, UK: Blackwell, 2003), 2.

18. Sheila Fitzpatrick, Everyday Stalinism: Ordinary Life in Extraordinary Times; Soviet Russia in the 1930s (New York: Oxford University Press, 1999). There are a number of sources discussing American travelers to the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s. See, for example, Sylvia Margulies, The Pilgrimage to Russia: The Soviet Union and the Treatment of Foreigners, 1924–1937 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1968); Lewis S. Feuer, "American Travelers to the Soviet Union, 1917–1932: The Formation of a Component of New Deal Ideology," American Quarterly 24 (Summer 1962), 119–49; Paul Hollander, Political Pilgrims: Western Intellectuals in Search of the Good Society (New Brunswick, NJ: Transaction Publishers, 1998); Ludmilla Stern, Western Intellectuals and the Soviet Union, 1920–1940: From Red Square to the Left Bank (New York: Routledge, 2007); Michael David-Fox, Showcasing the Great Experiment: Cultural Diplomacy and Western Visitors to the Soviet Union (New York: Oxford University Press, 2011).

19. Koner Diary, December 24, 1935, and January 30, 1935.

20. Roger D. Markwick and Euridice Charon Cardona, Soviet Women on the Frontlines during the Second World War (London: Palgrave Macmillan, 2012), 8.

22. Ted Shawn, Every Little Movement (Brooklyn, NY: Dance Horizons, 1963); Genevieve Stebbens, Delsarte System of Expression (New York: E. S. Werner, 1887). On Delsarte's influence, see Hillel Schwartz, "Torque: The New Kinesthetic of the Twentieth Century," in Incorporations, edited by Jonathan Crary and Sanford Kwinter, 71–126 (New York: Zone, 1992).

23. John Martin, "Dance as a Means of Communication" (1946), in What Is Dance: Readings in Theory and Criticism, edited by Roger Copeland (New York: Oxford University Press, 1983), 146.

24. David L. Hoffman, "Bodies of Knowledge: Physical Culture and the New Soviet Man," in Language and Revolution: Making Modern Political Identities, edited by Igal Halfin (New York: Routledge, 1992), 231.

26. Pauline Koner, Solitary Song (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1989), 145–46. Duncan's final dances in Russia were more in this style as well. See Ann Daly, "The Continuing Beauty of the Curve: Isadora Duncan and Her Last Compositions," Ballet International 13, no. 8 (August 1990): 10–15. Even so, Duncanism was by this time firmly understood as "wave-like movements for girls in tunics." Irina Sirotkina, "Dance-Plyaska in Russia of the Silver Age," Dance Research 28, no. 2 (2010): 146.

27. David L. Hoffman, Cultivating the Masses: Modern State Practices and Soviet Socialism, 1914–1939 (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 2011), 110.

28. On the proletarian or revolutionary dance movement and Duncan's influence on young Jewish dancers, see Ellen Graff, Stepping Left: Dance and Politics in New York City, 1928–1932 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 1997), 18; Mark Franko, Dancing Modernism/Performing Politics (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 1995), 25–26, 109–44. Also on Duncan's influence, see Edith Segal Oral History, Edith Segal Papers, New York Public Library for the Performing Arts. For commentary about dance in the Soviet Union, see, for example, Leonard Dal Negro, "Return from Moscow: An Interview with Anna Sokolow," New Theatre (December 1934): 27.

29. Koner performed at a Lenin-Liebknecht-Luxemburg memorial sponsored by the Young Communist League on January 15, 1937 (Graff, Stepping Left, 48). Koner discusses her "socially conscious" dances in Solitary Song, where she recalls a costume her mother made for her as a child, "a little chiffon tunic trimmed with rosebuds, and a little wreath for my hair." Wearing that costume, Koner "would do these dances that now, I realize, were very close to the Duncan style. It was called 'interpretive dancing.' But I just did free movement that came out from the inside" (114). One of her great regrets, in fact, was that she never got to see Duncan actually dance: as child Koner saw a poster of Duncan, and her mother promised to take her to one of Duncan's concerts when she was next in the United States, but Duncan never came back. Pauline Koner Oral History with Peter Conway, 1975, Pauline Koner Papers. Koner's papers contain a file devoted to Isadora Duncan.

31. Ibid., 18, 23–55. On Ito, see the Michio Ito Foundation, http://www.michioito.org/. On Nimura, "Inventory of the Yeichi Nimura and Lisan Kay Nimura Papers, 1903–2006," New York Public Library, http://www.nypl.org/sites/default/files/archivalcollections/pdf/Nimura_1.pdf.

33. Rebecca Rossen, "Hasidic Drag: Jewishness and Transvestism in the Modern Dances of Pauline Koner and Hadassah," Feminist Studies 37, no. 2 (Summer 2011): 340. Koner did perform an anti-Hitler dance in 1933 and frequently performed at events sponsored by Jewish groups. See "Pauline Koner, Brilliant 21-Year-Old Dancer, Greatly Incensed at Adolf," Jewish Examiner, June 1933.

34. Claude McKay, A Long Way from Home, edited by Gene Andrew Jarrett (New Brunswick, NJ: Rutgers University Press, 2007), 118. The phrase "magic pilgrimage" comes from McKay's description of his 1922 trip to the Soviet Union, and the phrase "new people" is a rough translation of the popular Soviet ideal of a novy sovetsky chelovek, or new Soviet person. For further discussion, see Kate A. Baldwin, Beyond the Color Line and the Iron Curtain: Reading Encounters between Black and Red, 1922–1963 (Durham, NC: Duke University Press, 2002), 18.

35. Daniel Soyer, "Back to the Future: American Jews Visit the Soviet Union in the 1920s and 1930s," Jewish Social Studies 6, no. 3 (2000): 125.

36. Ibid.; Koner, Solitary Song, 94. She mentions seeing King Lear at the Jewish State Theater in her diary (and being impressed with it), Koner Diary, March 4, 1935. Photographs suggest that she may have also performed one of her "Jewish dances" in Russia, although she does not mention this in her diary or memoir.

37. Beatrice King, Changing Man: The Education System of the U.S.S.R (London: V. Gollancz, 1936).

39. Koner Diary, January 27, 1935.

49. Mikhail Yampolsky, "Kuleshov's Experiments and the New Anthropology of the Actor," in Inside the Film Factory, edited by Richard Taylor, 31–34 (New York: Taylor and Francis, 1994). For Pudovkin's writing on the role of gymnastics and movement in film, see Vsevolod Pudovkin, "The Internal and the External in an Actor's Training" (1938), in The Film Factory, edited by Richard Taylor, 393–97 (London: Routledge, 1988).

50. Paul Babitsky and John Rimberg, The Soviet Film Industry (New York: Praeger, 1955), 122, qtd. in Amy Sargeant, Vsevolod Pudovkin: Classic Films of the Soviet Avant Garde (London: Tauris, 2000), vii. An undated letter (1935 or 1936) from Pudovkin to Koner emphasizes the importance of dance ("dance is the most immediate the most inartificial art"), and urges Koner to "view the new victory as your own victory." Pudovkin to Koner, n.d. (folder labeled ca. 1935–1936), Koner Papers, box 3, folder 8.

51. Karen Petrone, Life Has Become More Joyous Comrades: Celebrations in the Time of Stalin (Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000), 1.

52. Koner Diary, April 9, 1936.

53. James Riordan, Sport in Soviet Society: Development of Sport and Physical Education in Russia and the USSR (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 20, 53, 146.

54. Hoffman, Cultivating the Masses, 115.

56. Mary Anne Santos Newhall, "Uniform Bodies: Mass Movement and Modern Totalitarianism," Dance Research Journal 34, no. 1 (Summer 2002): 27–50.

57. Petrone, Life Has Become More Joyous Comrades, 1. See also Jane Dudley, "The Mass Dance," New Theatre (December 1934): 17–18; Graff, Stepping Left; Erika Fischer-Lichte, Theatre, Sacrifice, Ritual: Exploring Forms of Political Theatre (New York: Routledge, 2005); Susan Manning, Ecstasy and the Demon: The Dances of Mary Wigman (Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2006); Hoffman, Cultivating the Masses.

58. Choi Chatterjee and Karen Petrone, "Models of Selfhood and Subjectivity: The Soviet Case in Historical Perspective," Slavic Review 67, no. 4 (2008): 978. Chatterjee and Petrone are here referring particularly to the work of Igor Halfin and Jochen Hellbeck, who draw on Foucault's concept of the self.

59. Choi Chatterjee, Celebrating Women: Gender, Festival Culture, and Bolshevik Ideology, 1910–1939, Pitt Series in Russian and East European Studies (Pittsburgh: University of Pittsburgh Press, 2002), 140.

60. Koner Diary, n.d. (but under the April 9, 1936, entry, final entry in diary); Koner, Solitary Song, 107.

61. "Fizikyltyriy Parad v Leningrade," Pravda, July 13, 1936, 1 (my translation).

62. Koner, Solitary Song, 108, 110.

63. Pauline Koner, Elements of Performance: A Guide for Performers in Dance, Theatre, and Opera, Choreography and Dance Studies (Chur, Switzerland, and Langhorne, PA: Harwood Academic, 1993).

64. Hoffman, Cultivating the Masses, 1.

65. On the Soviet "superwoman" see Markwick and Cardona, Soviet Women on the Frontlines during the Second World War, 33.