A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement and Its Times

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

27 | European New Lefts, Global Connections, and the Problem of Difference

The milestone anniversaries of the 1960s have occasioned a flurry of scholarship on the protest movements that have long been synonymous with that decade. For historians, approaching the fifty-year mark has placed the events of the 1960s squarely in the past and made them legitimate objects of study. It should come as no surprise, then, that a wave of scholars has recently begun to scrutinize this period from a number of critical perspectives, seeking to understand the roles of multiple actors (famous and otherwise) and the highly complex causes and consequences of their actions. This new work moves well beyond the myriad personal accounts offered by veterans of the student movements that have dominated the histories of the New Left, the 1960s, and 1968.[1]

The fiftieth anniversary of the Port Huron Statement offers an opportunity not only for activists and participants to revisit one of their signature achievements but also for scholars to take stock of the latest historical work on the New Left that has expanded our understanding of the movement both temporally and spatially. Many people familiar with the early history of the New Left in the United States know that members of Students for a Democratic Society (SDS) gathered in late spring 1962 at a United Auto Workers retreat in Port Huron, Michigan, to draft a manifesto. The Port Huron Statement, as it was later called, sought to identify the “complicated and disturbing paradoxes in our surrounding America” and proposed “truly democratic alternatives to the present.”[2] It laid out a “youth agenda for the 1960s”—including active participation in policy debates, grassroots mobilization, and public protest—that served as the political road map for the US student movement.[3] Less well known is the fact that Michael Vester, a leader of West Germany’s Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (German Socialist Student League), attended the conference at Port Huron, participated in drafting the statement, and served as an important conduit between German and American activists. The conversations and collaborations between Vester and Tom Hayden, universally recognized as the chief author of the Statement, bespeak the crucial role of transatlantic networks and exchanges in shaping the politics and strategies of 1960s New Left–inspired student radicalism.

This chapter assesses the recent push to take seriously the global aspects of the New Left, a body of work that has extended our geographical perspective not only from the US to Europe but also across the world. Focusing specifically on European contexts, I examine how attention to the global has altered scholarly approaches to 1968 and fundamentally transformed our understanding of the larger movement. I ultimately suggest that global networks must be pursued even further because at least two major postwar developments—the process of decolonization and the economic demand for foreign labor migrants—brought the world to Europe in unprecedented ways. By following the exchanges among activists engendered by these twin developments, an understudied and largely unacknowledged strand of New Left engagement becomes visible. Questions of “difference,” in short, emerge as a constitutive element of the European New Left’s formation and legacy.

Although contemporaries widely acknowledged the eruption of student protest in the late 1960s as a worldwide phenomenon, the story of New Left political radicalism has traditionally been told through a national lens. For instance, the volume 1968: The World Transformed, whose publication coincided with the thirtieth anniversary of the events in 1968, devoted an entire section to “challenges to the domestic order”—with separate chapters on the United States, Poland, France, and Germany—as well as a final chapter on the Third World.[4] This insistently national framework—albeit one in which many national stories appeared side by side—made it difficult to see connecting threads across the Atlantic, across the Iron Curtain, and across the globe. My point here is not to suggest that international connections have been entirely absent in previous scholarship. Some early histories, of course, noted that the events of 1968 spanned the globe: the Tet Offensive began in late January, just as the Prague Spring was gaining momentum; the West Berlin Vietnam Congress took place in February, followed by the twenty-five-thousand-strong antiwar march in London; and the May student uprisings and worker strikes in France followed quickly on the heels of the student takeover of Columbia University.[5] Other histories have pointed to the key role of someone like Michael Vester.[6] But until the last few years, scholarly narratives have often presented such connections as self-evident chains of reaction requiring little explanation or as exceptional exchanges, facilitated by exceptional individuals.

In many ways, this predominantly national frame has been reinforced by the best-known images of the New Left. For the European scene, there is perhaps no more iconic event than the student demonstrations in Paris during May 1968 and no more iconic figure than Daniel Cohn-Bendit, or “Danny the Red” (figure 1).

In this photograph taken by Jacques Haillot on May 3, 1968, near the Sorbonne, Cohn-Bendit confronts a member of the French riot control forces (Compagnies Républicaines de Sécurité), wild-eyed and laughing as if to provoke a reaction. The news photo was quickly transformed into a revolutionary poster—“Nous sommes tous ‘indésirables’”—by the Atelier populaire des Beaux-Arts (figure 2).[7] Plastered on the walls of Paris during the student demonstrations and worker strikes that paralyzed the country for six subsequent weeks, the ubiquitous face of Danny the Red became synonymous with May 1968. This image evocatively captures many of the defining elements of a broader history: the centrality of the “youth” generation’s perspective; the confrontation with state authority and its enforcers; and the commitment to taking democracy into the streets. But it is also a strikingly national image: a French student leader in the midst of French protesters confronting a French policeman on the streets of the French capital photographed by a French journalist. Of course, the actual circumstances were more complicated. For one thing, the French president Charles de Gaulle wanted to expel Cohn-Bendit as an “undesirable” and German citizen, even though the radical had spent his childhood in France and was attending university there. But the larger point still holds: this picture depicts a historically specific movement within a singular national frame.

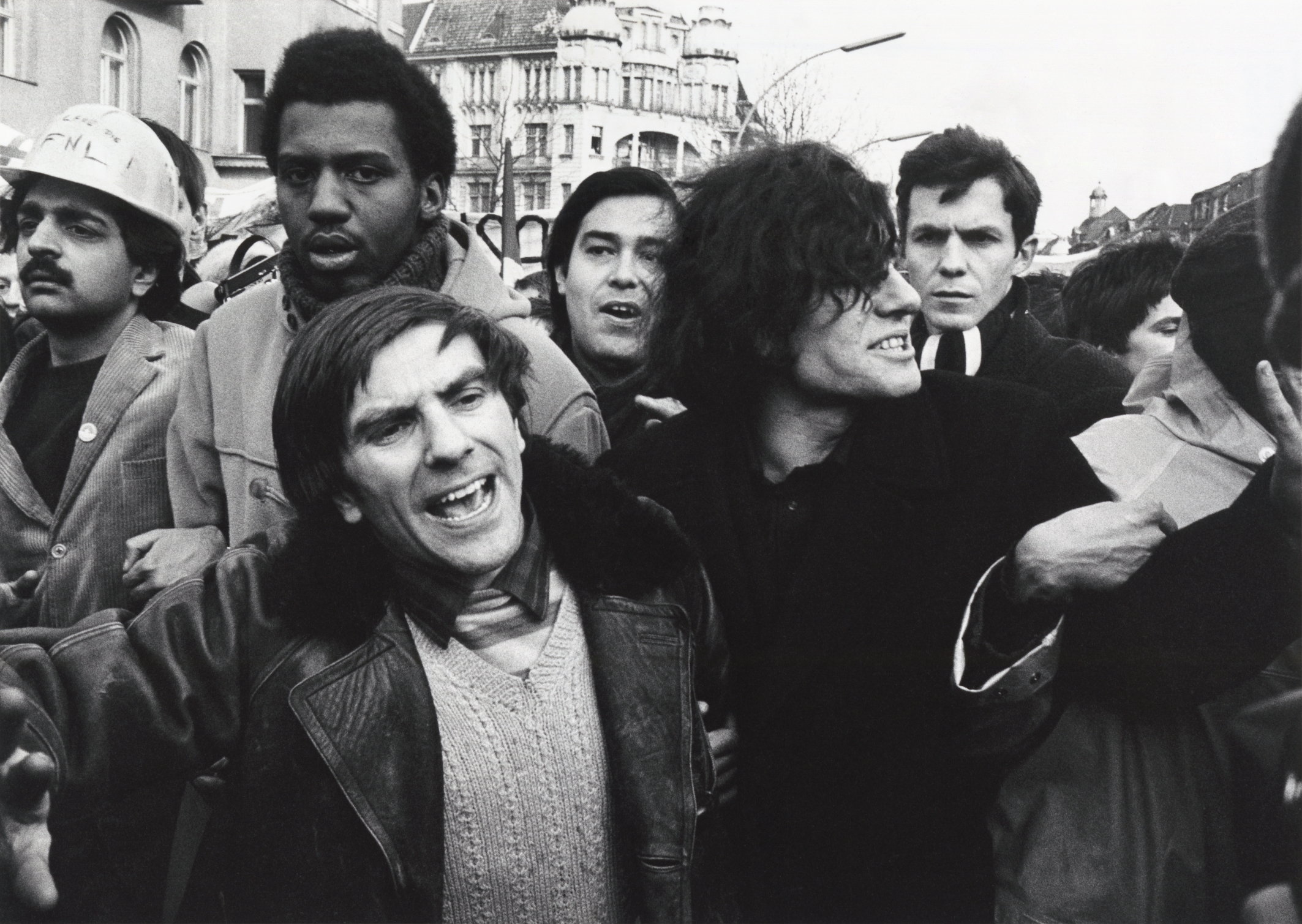

By way of contrast, consider a second image that is far less known, even though it portrays an event that is arguably just as important for understanding this history (figure 3). Here, Rudi Dutschke, a central figure in the Berlin chapter of the German Sozialistischer Deutscher Studentenbund (SDS), is flanked by the Pakistani Tariq Ali (at far left), the American Dale Smith, and the Chilean Gaston Salvatore. Arm in arm, they lead an antiwar demonstration through the streets of West Berlin in February 1968, marking the end of a two-day international conference on the Vietnam War. If we expand our geographical frame—not only from Paris to Berlin but across the globe—we might conclude that this photograph is more representative of the European New Left. But to appreciate the significance of this image, it is useful to begin by examining the new perspectives opened up by recent attention to the global.

One major effect of widening the geographical purview on 1968 has been a rethinking of chronology. Earlier narratives of the student protest movements generally took 1968 as their focal point. This approach had at least two historiographical effects. First, it tended to treat the first waves of New Left activism as a mere prelude to the spectacular upheavals of that annus mirabilis. Second, it placed undue emphasis on big events. Even in its broader application, “1968” has often served as useful shorthand or metonym for the major moments that took place over the course of the decade. This event-driven mode of analysis has frequently produced a lack of attention to questions of process: How did the student protest movements develop? Which ideas and actors were instrumental in shaping their evolution? What consequences did these movements produce? Yet, as Timothy Brown has pointed out, the term “1968” “operates not merely as a temporal designation but as a spatial one”: it suggests “a world-historical conjuncture, centered roughly around the year 1968, which took place over a sufficiently large expanse of the globe—from Paris to Mexico City, from Berkeley to Dhaka, from Prague to Tokyo—so as to figure as a ‘global’ event.”[8] The concept of 1968, in short, enfolds the temporal and spatial together.

Recent efforts to take seriously the global character of 1968 have necessarily shifted attention away from singular moments and toward longer patterns of cross-pollination. This approach, moreover, has resulted in an expansion of the temporal timeframe. Indeed, much of the latest work on the New Left’s transnational connections has adopted versions of Arthur Marwick’s “long sixties” periodization, extending backward as early as 1954 and forward as late as 1978.[9] The broadening of frames, in turn, has opened up new kinds of questions about the development and trajectories of the European New Left: How, for example, did the networks established in 1957 between the National Union of French Students and the Algerian National Liberation Front (FLN) influence French students’ efforts to gain the support of factory workers in May 1968? In what ways did the exchanges between American sociologist C. Wright Mills and the editors of the British journal New Left Review in 1960 shape the emergence of cultural Marxism within the British New Left?[10] How did interactions between the Black Panther Party and West German student activists help radicalize splinter groups in the Federal Republic? What kinds of influence did the Weather Underground and the Red Army Faction (RAF) have on each other in the early 1970s?[11] In what ways did the early 1970s French Tel Quel group absorb the principles of Mao’s Cultural Revolution?[12]

Somewhat paradoxically (though not, perhaps, surprisingly), these temporal and geographical expansions have also pushed scholars to concentrate their focus, to examine a more limited set of actors or activist groups in order to trace how the exchanges actually worked. First-wave efforts to consider the New Left’s global dimensions emphasized a wide-angle perspective, pointing to—among other things—the crucial impact of new kinds of communication technology. Satellites, for example, gave television and other news media the potential to spur action around the world through the instantaneous transmittal of a single searing image.[13] But beyond noting the synchronicity of protests in multiple countries, these early observations offered little explanation of how such parallel actions transpired. Several years ago, Martin Klimke bemoaned precisely this absence, arguing that the “exact processes through which activists from numerous countries established contact, shared ideas, and adopted each other’s social and cultural practices are still largely unexplored.”[14] His own recent study of the relationship between the American SDS and the West German SDS, however, has begun to fill the gap.

In The Other Alliance, Klimke tracks the unexpectedly close—even personal—connections between the American and German SDSs, shedding light on the specific ways these groups supported and influenced each other. German exchange student Michael Vester, for instance, was an active recruiter for the American SDS from his home base at Bowdoin College. Not only did he attend the Port Huron conference in 1962, but he offered a detailed response to a preliminary draft of the celebrated statement. He encouraged Tom Hayden to be more explicit about the “societal contradictions pointed out by socialist analysis,” highlighting in particular “the gaps between political democracy and economic concentration of power.”[15] Vester further provided an international perspective on the concerns that the two SDS groups shared. As Hayden later recalled, “We were very interested in what Michael Vester . . . had to say about the cold war and its effects on Europe. He helped internationalize our understanding of what we faced.”[16] At the same time, the American SDS took a keen interest in the struggles of its West German counterpart. When American SDS president Al Haber learned from Vester about the German Social Democratic Party’s decision to expel all members of the German SDS (its own youth wing) from its political organization, he wrote letters in defense of his West German colleagues. Klimke concludes that the American and West German SDSs “openly supported one another in the face of massive institutional pressure from their parent organizations as well as attacks by international socialist associations on a New Left ideology that both groups could identify with.”[17] What emerges here is a far more nuanced picture of transnational New Left connections, one in which the American and German SDSs not just were vaguely aware of each other but forged close personal bonds that facilitated the exchange of theoretical ideas as well as practical collaborations.

In tracing the global dimensions of the New Left, scholars have been forced to pay closer attention to the particular networks that traversed national borders. Here again, the recent work has been instructive. Maria Höhn has examined West German student radical K. D. Wolff’s efforts to establish Black Panther Solidarity Committees in late 1969. A major goal was to connect with politicized African American GIs stationed in the Federal Republic in order to forge a revolutionary alliance that would “unseat the centers of American empire in both Germany and the U.S.”[18] Höhn details the strategies used by student activists to garner the attention and interest of African American soldiers. These included protesting in front of US military barracks, adopting the Black Power salute, frequenting bars and discos that catered to African American GIs, and participating in Black history study groups on the bases. Such initiatives led to joint rallies across West Germany to criticize the Vietnam War and demand freedom for Black Panther leader Bobby Seale. They also led to collaboration on an underground newspaper, Voice of the Lumpen. The solidarity between American GIs and West German students culminated in a joint effort to gain the acquittal of the “Ramstein Two,” a pair of African American former GIs who were arrested in a shooting incident that injured a German security guard at Ramstein Airbase. Höhn’s work, moreover, provides a crucial backstory for Klimke’s argument about the US Black Power movement serving as role model for the radicalization of the West German New Left and specifically the RAF, which, he claims, applied Black Panther notions of “armed struggle” in the Federal Republic during the 1970s.[19]

This rich and fruitful exploration of New Left networks has largely focused on intra-European or transatlantic exchanges.[20] Less well understood are the connections between the European New Lefts and those in the so-called Third World. In the US context, by contrast, the Third World angle has received considerable attention. Historians have explored the early involvement of foreign students of color with the civil rights movement; the active engagement of African American activists and intellectuals with independence movements in Africa and Asia; the importance of anticolonialist networks between the United States and Africa; and the impact of the Cuban Revolution and the Bandung Conference on activism in the United States.[21] By and large, this body of scholarship takes the US context as its center of gravity, but it has also opened up new perspectives on the complex ways that global politics informed domestic American issues and concerns.[22]

To the extent that scholars previously acknowledged the European New Left’s relationship with the Third World, they tended to interpret it as a kind of “screen” onto which European radicals projected their own national and generational psychic dramas.[23] This line of argument has been especially prominent in the scholarship on West Germany, due in no small part to the long shadow cast by the Holocaust. Here, activists’ interest in Third World revolutionaries or internationalism has been read as an attempt “to exonerate themselves as Germans and claim a position that transcended national sins” or as “a means of escaping from a despicable skin, the skin of being a German.”[24] Even Richard Wolin’s recent book on French Maoists asserts that China of the Cultural Revolution “became a Rorschach test” for the “innermost radical political hopes and fantasies” of these gauchistes. “By ‘becoming Chinese,’ by assuming new identities as French incarnations of China’s Red Guards,” he writes, “these dissident Althusserians sought to reinvent themselves wholesale. Thereby, they would rid themselves of their guilt both as the progeny of colonialists and, more generally, as bourgeois.”[25]

The most compelling recent work has sought to treat the European New Left’s links to the Third World more seriously, investigating institutions that fostered contacts between European leftists and people from around the world. One crucial nexus was the university. In Foreign Front, Quinn Slobodian focuses on the social milieu of West Berlin’s Free University (FU), noting that more than ten thousand foreigners from Asia, Africa, and Latin America were studying on West German campuses by the early 1960s.[26] Some, like the Nigerian student Adekunle Ajala, were funded by the German Academic Exchange (Deutscher Akademische Austauschdienst); others received support from the Fulbright Commission; still others relied on family money for their German education.[27] It was in such contexts that German SDS leaders Rudi Dutschke and Bernd Rabehl formed an “international working group” in 1964 to discuss Marxist and critical theory with fellow students from Latin America, Haiti, and Ethiopia.[28] They held their meetings in the “student village” near the FU in Dahlem, where some of the Latin American and Caribbean students lived. Through his regular visits to the student village, Dutschke also became friends with the Chilean activist Gaston Salvatore, the two ultimately collaborating on a German translation of Che Guevara’s final speech.[29] These concrete relationships impressed upon Dutschke the need for an “internationalization of strategy for the revolutionary forces” as well as pushed him toward a search for revolutionaries within West Germany who could serve as “domestic counterparts to Third World insurgents.”[30] By elucidating the personal connections and intellectual exchanges between Dutschke and foreign students such as Salvatore, Slobodian effectively counters the notion that the Third World was a mere projection—or fetish object—of German radicals as well as the paternalistic assumption that German students merely served as “mentors” for their international peers.[31]

Indeed, many foreign students were politically active in freedom movements, decolonization efforts, and national liberation struggles in their home countries. As genuine dialogue partners with German activists, they had a major impact on how members of the West German New Left came to understand revolutionary action. When Moïse Tshombe, Congolese prime minister and former Katanga secessionist, paid an uninvited state visit to West Germany in December 1964, the FU’s African Student Union led by the Nigerian Ajala spearheaded a public protest.[32] The action was supported by members of the SDS, the Latin American Student Association, and FU-based Argument Club.[33] Dutschke was among the eight hundred demonstrators in West Berlin, where the original plan of a silent march turned into “an assault on public order involving catcalls, thrown tomatoes, and scuffles with the police.”[34] Acknowledging the foreign students’ impact on how this protest played out, Dutschke noted in his diary, “Our friends from the Third World stepped into the breach and the Germans had to follow.”[35] With such collaborations in mind, scholars now view foreign students as a central catalyst for the internationalist consciousness that shaped the antiauthoritarian wing of the SDS and came to dominate the West German student movement after 1965.[36]

In actual practice, though, the university served as an important setting for contact and exchange between leftist activists and foreign students well before the 1960s moment. In Britain, for example, foreigners from the various colonies began to matriculate at Oxford and Cambridge in significant numbers in the 1870s.[37] By 1960, there were nearly fifty thousand overseas students in the United Kingdom.[38] As Jordanna Bailkin has argued, postwar Britain became a “crucial hub of international education,” and the British government actively encouraged foreign students to study in the United Kingdom because it viewed their education in Britain as a way to “monitor” and “manage” the process of decolonization.[39] Of course, the British state could not fully control the political orientation and activities of its New Commonwealth charges. Among the early waves of postwar exchange students was Stuart Hall, who came from Jamaica in 1951 to study at Oxford as a Rhodes scholar. At first, his social circles predominantly consisted of the small number of Oxford Third World students who shared an interest in “colonial” questions. But he quickly came into contact with members of the “Oxford left” and began to weigh in on a range of contemporary issues—the future of the Labour Party and the left, the nature of the welfare state and postwar capitalism, the impact of cultural change during the age of British affluence—through his collaborative work on the journal Universities and Left Review in the late 1950s.[40] From there, Hall went on to become the first editor of New Left Review and the father of British cultural studies.[41] In both roles, he was uniquely positioned to initiate questions on race and ethnicity, racism, and decolonization as part of the broader effort to renew the British left through a “radically new analysis of the social relations, dynamics and culture of postwar capitalism.”[42]

Tariq Ali played an equally important role in the trajectory of British New Left radicalism during the late 1960s. Ali arrived at Oxford from Pakistan in 1963 and quickly began meeting with the Socialist Group inside the Oxford Labour Club. In 1965, he was elected president of the Oxford Union, the university’s debating society, and began to concentrate his political activism on the Vietnam War, establishing a Vietnam Committee on campus and organizing a teach-in on the conflict.[43] A founding member of Britain’s Vietnam Solidarity Committee (VSC) as well as its most prominent spokesman, Ali initially sought to challenge the Labour Party’s support of US intervention in Southeast Asia but eventually articulated a much broader critique that fused strenuous anticolonialism (abroad) with a desire for radical social transformation (at home).[44] Throughout 1967, he orchestrated several demonstrations against the Vietnam War in London, culminating in a massive VSC-sponsored protest in March 1968. Assessing Ali’s central part in this event, a reporter for India Abroad noted in 2008, “The 1967 [sic] student revolt that nearly toppled the Charles De Gaulle government in France was led by home-grown radicals. Across the Channel, around the same time, 25,000 students were marching on the American embassy in London, protesting the Vietnam War—and they were led not by an Englishman, but by someone who was not even born in that country.”[45]

This reporter’s characterization brings us back to the contrasting images of the European New Left with which I began—and especially the photo from Berlin (figure 3). This picture was taken at an antiwar demonstration that was part of the West Berlin International Vietnam Congress in February 1968. As noted earlier, flanking Dutschke are the Pakistani-born Oxford student Ali, representing the London-based Vietnam Solidarity Committee; the African American Vietnam veteran Dale Smith, representing the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee; and the Chilean-born FU student Gaston Salvatore, a nephew of the future Chilean president Salvador Allende. Each of these figures, we might say, represented a connecting thread between the New Left in Europe and the wider world. Their very presence—and collaborative efforts—force us to recognize the ways in which an event that has previously been read as West German was, in fact, the product of multiple lines of influence—from the United States to Asia by way of the United Kingdom and Latin America. As Ali explains in his memoir, this event was “an important turning point for the Vietnam movement in Europe. It was the first real gathering of the clans and it reinforced our internationalism as well as the desire for a world without frontiers.”[46] More effectively than the iconic image of the May events in Paris, this photograph of the Vietnam Congress in Berlin captures the global exchanges that were crucial to the development and evolution of the New Left in Europe.

By way of conclusion, I want to suggest a few of the ways in which a global line of questioning might be pursued even further. For the most part, the new work stressing transnational and global connections has focused on well-known figures, collaborations, and networks, clustered between about 1964 and 1970. But this line of inquiry needs to be taken further, extended to less obvious actors and organizations but also to less established moments in the larger history. We would do well, for example, to consider the years when the political category of the Third World was gaining discursive traction.[47] Starting in the second half of the 1950s, left activists in both France and West Germany served as couriers (of money and information) for the Algerian FLN. The underground network organized by Francis Jeanson in 1957 is already familiar to scholars, in large part because of his coauthored book denouncing French policy in Algeria and because of his highly publicized arrest and trial in 1960.[48] Historians of postwar France make passing reference to Jeanson, Alain Krivine, Henri Curiel, Félix Guattari, and the cartoonist Siné as supporters of the Algerian cause.[49] But we know very little about how the courier network itself functioned in practice. And we know even less about transnational connections established elsewhere in France, in cities like Marseille, Lille, and Lyon. The Lyon organization is of particular interest because it facilitated contact between the FLN and West German leftists such as Reimar Lenz and Hans Jürgen Wischnewski, who also acted as couriers for the Algerians.[50] Recently, Christoph Kalter has written a remarkable book on the French left’s engagement with decolonization, focusing in particular on François Maspero’s leftist publishing network. Maspero owned a Latin Quarter bookstore that sheltered Algerians during the October 1961 massacre, and his Maspero publishing house brought out the first edition of Frantz Fanon’s The Wretched of the Earth as well as other landmark books critical of the Algerian war.[51] Filling out this history of postwar anticolonialism—not just in France but also in West Germany and Britain—would help answer some crucial questions: How did engagements with the Algerian and other independence movements transform young European leftists’ understanding of politics? Of leftism? What influence might their experiences have had on their conceptualizations of former colonies that would eventually come to be known as the “Third World”? And how did these ideas shape an emerging “new” Left?

On the other side of the conventional periodization, we would do well to look more closely at the early 1970s, a moment of expanding encounters between left activists and foreign workers located squarely within European borders. Even amid the New Left’s search for an alternative revolutionary subject, there were numerous activists who continued to identify the working class as the key to radical social transformation and directed their organizational energies into the factories. These included students who occupied factories with workers throughout the Paris region in May and June 1968; members of the Maoist Gauche prolétarienne, who helped mobilize protests at the Renault-Billancourt factory in 1970 and 1972; and Marxist-Leninist oriented communist cadres or “K-groups” and informal spontaneity groups (later known as Spontis), which participated in the 1973 wildcat strike at the Ford factory in Cologne.[52] Through such actions, French and West German radicals encountered—many for the first time—large numbers of laborers from former colonies and guest workers. In many respects, these encounters suggest another dimension to the European New Left’s internationalist turn, one that has had major implications for postwar European society. And yet we know virtually nothing about how the early lines of collaboration developed between French and West German activists and immigrant workers or how these alliances may have transformed the thinking and priorities of a fragmenting New Left.

Accounting for the global in our narratives of the European New Left significantly alters the contours of the story of postwar leftism—not just in terms of key actors, groups, or events but also in terms of the larger story. What the global frame insistently underscores is the central place of “difference” in shaping the concerns, engagements, and actions of the New Left in Europe. This engagement can no longer be relegated to a handful of distant issues such as the US civil rights movement and the Vietnam War or downplayed as a peripheral set of concerns. In assessing the European New Left in view of its global connections, what becomes clear is that engagement with various forms of cultural, racial, and ethnic difference began as early as the transnational courier networks for the FLN, continued with exchanges between the American and West German SDSs, and was deepened through dialogues with foreign students. These dialogues, in turn, facilitated collaborations around the Berlin Vietnam Congress, produced new forms of solidarity with the Black Panthers and African American GIs, and included cooperation with a wide range of immigrant workers in factory actions. Acknowledging that questions of difference constituted an ongoing and evolving concern within New Left politics pushes against our conventional narratives of a neat and easy shift from class to race or from material conditions to questions of culture, ethnicity, or religion. More accurately, it seems to me, these issues have always been overlapping and mutually constitutive within New Left politics. Thus far, we have yet to consider how the New Left’s engagement with questions of difference changed over time—a crucial issue if we are to make sense of our current political climate, a moment when public pronouncements on the “failure” of multiculturalism have become increasingly commonplace across the wider region.