A New Insurgency: The Port Huron Statement and Its Times

Skip other details (including permanent urls, DOI, citation information): This work is licensed under a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-NoDerivatives 3.0 License. Please contact [email protected] to use this work in a way not covered by the license.

For more information, read Michigan Publishing's access and usage policy.

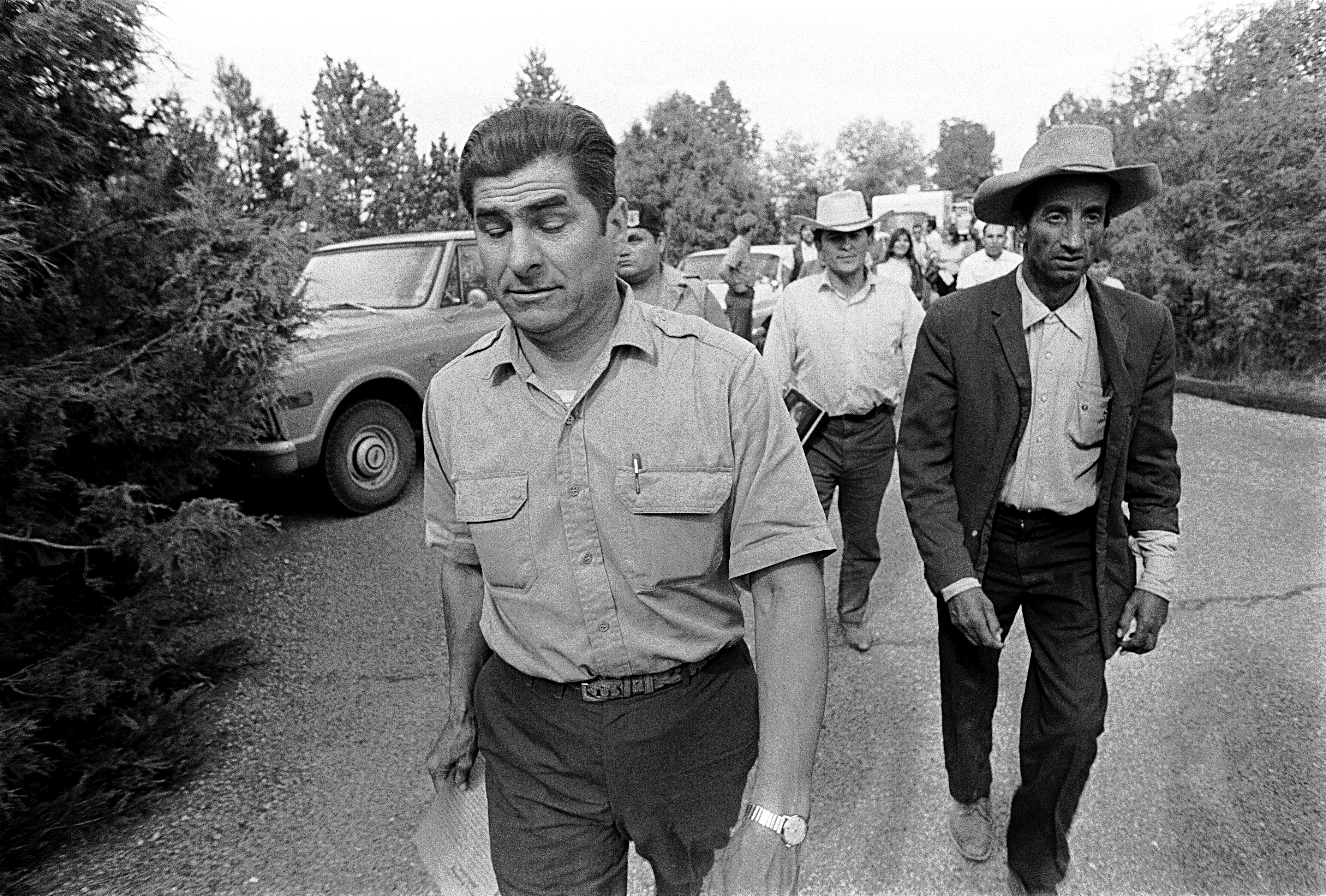

22 | The Religious Origins of Reies López Tijerina’s Land Grant Activism in the Southwest

In the history books that chronicle the ethnic Mexican experience in the United States, two men are hailed as its most important civil rights leaders: César Chávez and Reies López Tijerina. César Chávez is often compared to the Reverend Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. as an activist who demanded better wages and working conditions for farmworkers through peaceful, time-tested unionization strategies. Chávez’s practice of nonviolence, his fasts, and his pilgrimages, along with his nationwide boycotts of different crops (table grapes, lettuce, strawberries), led to his sanctification as the Mexican American Gandhi, a legacy that is now more hotly contested.[1]

Reies López Tijerina is probably a name many have never heard before. In the historiography, he is depicted as the mecha, as the spark that unleashed the militant Chicano struggle for national liberation in the 1960s. He took up arms and seized federal lands, thus emboldening young Chicano men to advocate a militant nationalism throughout the Southwest, demanding jobs, educational reform, and an end to the exercise of arbitrary and unwarranted state force. Some Chicanos even harbored the utopic dream of building an independent nation-state called Aztlán and took their inspiration for regaining lost lands from the Alianza Federal de Mercedes (Federal Alliance of Land Grants), the organization Tijerina founded in 1963 to seek the return of communal lands taken by the US government after the Mexican War in 1848. In 1967 both Newsweek and the left-wing Militant called Tijerina the “New Malcolm X.” On April 20, 1968, the Saturday Evening Post went further, transforming Tijerina into a caricature by translating his name into English as “King Tiger.” The intent was clear: the magazine meant to link Tijerina to the frightening image of the Black Panthers.[2]

Reies López Tijerina was born into a sharecropping family near San Antonio, Texas, in 1926. As a boy, he regularly migrated with his family to Michigan, following the crop cycles of cotton and sugar beets. At the age of fifteen, he had a religious conversion and decided to become a preacher, and in 1946, he began his public life as a fundamentalist Pentecostal affiliated with the Assemblies of God. For several years, he crisscrossed the Southwest staging revivals and preaching a fiery end-time theology. How did this conservative religious restorationist get transformed into a violent revolutionary? How did this itinerant preacher railing against the corrupting influences of modernity, heralding the millennial return of Jesus Christ and offering salvation, healing, Holy Spirit baptism, and tongues speech, become a cultural nationalist seeking the creation of the Chicano nation of Aztlán? The short answer is that the historiography on Tijerina is simply wrong. In their fervor to write a useable history, a history that would inflame the popular imagination to national revolution through racial revolt, a whole generation of Old Left and New Left historians fundamentally distorted Tijerina’s ideology, secularized his religious message, and elevated a carefully planned citizen’s arrest gone wrong as a major act of Chicano warfare, as the mecha, the spark of the revolution.[3]

Histories of the 1960s, New Left studies of the opposition to the war in Vietnam, and Chicano and Chicana historiography of the last forty years myopically begin the narratives of the Mexican American civil rights movement with two moments. The first is the September 16, 1965, strike against growers in California’s Central Valley. Led by César Chávez, it was followed by a pilgrimage from Delano to Sacramento, California, in 1966 and a series of fasts by Chávez to bring attention to his unionization campaign. I want to focus on the second moment, a June 5, 1967, courthouse scuffle in Tierra Amarilla, New Mexico, led by members of the Alianza Federal de Mercedes, a group of land grant heirs and sympathizers, which Tijerina began and served as its president. This courthouse fracas is now seen as the catalytic event that birthed Chicano radicalism.

The courthouse incident was the climax of an ongoing struggle between the Alianza and its archenemy, District Attorney Alfonso Sanchez, that dated back several years. On October 15, 1966, with great fanfare and glaring national television cameras recording, Tijerina and members of the Alianza seized portions of the Kit Carson National Forest, claiming that the land had been fraudulently stolen from their ancestors at the end of the nineteenth century. While personal familial plots, which constituted one part of the land grant Spain (and later Mexico) awarded colonists for the settlement of the realm, could indeed be bought and sold as personal property, the second part of these mercedes, the ancient commons (known as ejidos), were inalienable communal property vested in the town. At the end of the nineteenth century, however, the US federal government declared that these communal lands belonged to the sovereign, not to the towns, and as the area’s new sovereign was the United States, formally established by victory in war, the lands now belonged to the federal government.

That was precisely the reasoning challenged by the Alianza members whose communal lands had been appropriated by the federal government to form the Kit Carson National Forest. They invaded the space en masse, intending to restore the original land grant of 1706, given by Spain’s king to Francisco Salazar as the site of a new town, San Joaquin del Rio de Chama. Reclaiming that heritage by declaring the forest tract to be the Free City-State of San Joaquín del Rio de Chama, Tijerina and his followers elected a mayor and deputized several marshals to patrol the town. When National Park Service rangers eventually arrived, they were arrested, tried by the members of the town, found guilty of trespassing, and released with death threats. For two weeks, the Alianza maintained the occupation, arguing that they were the legal owners of the land, and if the federal government wanted to evict them, then the government would have to prove the validity of its claim.

The federal authorities were unwilling to do that. District Attorney Alfonso Sanchez repeatedly warned the Alianza and its president that the title to northern New Mexico’s lands had been adjudicated in the 1890s and that little could be done to address those dispossessions now. But when the national press moved on to their next news story, so too did the Aliancistas, ending the standoff.[4] Sanchez, in any case, was determined not to allow the Alianza to seize more land or to declare the formation of another independent city-state, fearing it would provoke further conflict in the area. Between 1965 and 1967, large tracts of land had been incinerated in northern New Mexico. Anglo farms, haystacks, and fences had been torched, livestock had been slaughtered, and farm equipment had been smashed. A US Department of Agriculture field station had been set ablaze. By attacking both symbols of Anglo and federal authority, the Hispanos of northern New Mexico were demonstrating their anger over the alienation of their ancestral lands and the severe shrinking of permits for the grazing of livestock on federal lands. Much as African Americans had burned down their ghettos in American cities those same summers, so Hispano passions over the historic loss of their communal lands in the 1890s had become particularly incendiary. Of course, the Alianza was not the only group capable of such vandalism, but no one could persuade Sanchez of that.

On June 2, 1967, he thus ordered the state police to block all the roads leading into the village of Coyote, where an Alianza meeting was scheduled. Eight Alianza members were arrested, were charged with inciting to riot, and spent the weekend in jail, awaiting their arraignment scheduled for Monday. Tijerina escaped arrest that day because he arrived at the event late, warned that a dragnet was in place.

On Monday, June 5, 1967, at about three o’clock in the afternoon, some fourteen to twenty Alianza members (accounts vary) entered the Rio Arriba County courthouse in Tierra Amarilla, a small village about thirty miles north of Santa Fe, hoping to post bail for jailed Alianza members. Alianza’s leaders, angry that the district attorney had violated their right to assembly, also intended to make a citizen’s arrest of Sanchez and have him face a jury of his peers in San Joaquín del Rio de Chama, the free city-state they had declared in 1966.[5]

When the Alianza members entered the courthouse, they scurried through the building trying to find Alfonso Sanchez. When they could not, some became particularly irate and violent. Several were trigger-happy from the start and needed little provocation. Business in Santa Fe had kept Sanchez from appearing at the scheduled arraignment, but the Aliancistas suspected that they were being lied to and that he was actually hiding somewhere in the building. They systematically surveyed the courthouse, bludgeoning several employees to learn where Sanchez was, seriously wounding two court workers as their bullets flew about. The blaring sirens of approaching state police cars led to a quick retreat. They fled with two hostages, whom they quickly released. Whether Reies López Tijerina was actually present during the melee was much disputed for a time and was never proven in a court of law. His presence was later confirmed by Tijerina’s daughter, Rose, who was a participant and eyewitness to the day’s events, but it was always denied by her father.[6]

In the months that followed the June 5 failed citizen’s arrest of Sanchez, Tijerina was quickly hailed by New and Old Left leaders as a revolutionary hero. Elizabeth Martinez and Beverley Axelrod, women who had long been leaders in SNCC, moved to northern New Mexico, convinced that the struggle by poor farmers to regain their lost lands held the potential for revolutionary change. Was this the new Sierra Madre? By July 1967, Elizabeth Martinez had started the newspaper El Grito del Norte with the explicit goal of publicizing the glories of the Cuban Revolution and the necessity to construct a “new Man” and to tie local New Mexican struggles over land to other Third World national revolutionary struggles, particularly the one in Vietnam. Old Left newspapers reported on the New Mexican land grant struggle in similar ways, as the beginnings of a class struggle that would surely spark a proletarian revolution.[7]

On October 21, 1967, slightly more than four months after the attempted citizen’s arrest at Tierra Amarilla, Tijerina, now out of jail on bail for federal charges stemming from the occupation of the Kit Carson National Forest, convened the annual convention of the Alianza in Albuquerque. Present on the stage with Tijerina were the Hopi Indian chief Tomas Ben Yacya; Ralph Featherstone, SNCC’s program director; Maulana Ron Karenga, the founder of US Organization (i.e., “Us Black People”); and a number of Black Panther Party and Congress of Racial Equality members. Ralph Featherstone entered the auditorium with a sign that read, “Che [Guevara] Is Alive and Is Hiding in Tierra Amarilla.” The audience broke out into enthusiastic applause and listened to his harangue about black-Hispano commonalities and the urgency of “tak[ing] back what is ours by any means necessary.” Karenga likewise ended his speech, titled “People of Color: We Shall Survive,” by shouting out in Spanish, “¡Viva Tijerina! ¡Vivan los indios! ¡Vivan los hombres de color!” (Long live Tijerina! Long live the Indians! Long live men of color!). The conference ended with the ratification of treaties of “PEACE, HARMONY, AND MUTUAL ASSISTANCE BETWEEN THE SPANISH-AMERICAN FEDERAL ALLIANCE OF FREE CITY STATES” and the organizations represented, vowing mutual assistance, respect, and understanding.[8]

By the end of 1967, a significant mythology had taken shape about what had transpired at Tierra Amarilla earlier that year, but most Americans remained woefully ignorant of what Reies López Tijerina believed, how he had risen to national visibility, and what his movement was about. In 1969, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales, the person most responsible for forging a host of Mexican American student groups into a unitary national Chicano identity, proclaimed Tijerina the leader of the Chicano nationalist revolution who would restore the homeland of Aztlán. Interestingly enough, I have found no printed document or archival manuscript in which Tijerina has said that his 1960s activism was on behalf of Chicanos, Mexicanos, or Mexican Americans. Nor did Tijerina ever mention this in any of my personal interviews with him. He consistently explained that his activities were to improve the lives of Indo-Hispanos, an invented panethnic political identity that would be forged by Indians and Hispanos working together to regain the lands they once had under Spanish and Mexican rule.

Who was Reies López Tijerina? What was his lifelong message? Why did he go to New Mexico in the first place, and what did he accomplish there?

Reies Lopez Tijerina spent his childhood living in poverty with his family on the outskirts of San Antonio. They routinely followed the crops between Texas and Michigan as agricultural laborers. In summer 1941, he met an itinerant Baptist preacher named Samuel Galindo, who gave him a copy of the Bible in Spanish.[9] “I read it all,” Tijerina explained. “Then I got my brothers around the table and read it to them a second time. I noticed the word ‘justice’ used as many times as words like ‘love.’ So I read about Abraham, David, Ishmael, and the prophets. I found many words in there to reach my heart.” Mercy and truth, justice and peace: these were the keywords that resonated most in his imagination, prompting what he described as a “yearning of my heart for justice.” At the age of eighteen, Tijerina enrolled in the Assemblies of God Latin American Bible Institute in Saspamco, Texas, from which he graduated in 1946.[10] Together with his classmate and later wife María Escobar Chávez, they committed themselves to the salvation of souls.[11]

From 1946 to 1956, María and Reies Tijerina crisscrossed the United States staging revivals. They preached in homes, in halls, in tents—virtually anywhere people congregated. Never did he tire of spreading the word of God. His services were never short events and often consumed an entire day. They were exuberant gatherings full of singing and clapping, sobbing and shouting, with fits of anger and punching motions into the air to banish evil and Satan from their midst and guttural, other-worldly, seemingly ghostly speaking in tongues. Tijerina constantly announced that the living God would soon arrive and that it was time to repent and be saved.

The sermons Tijerina preached between 1946 and 1956 had a burning urgency to them. He called to repentance a generation he believed was lost to the vulgar materialism of modernity. As a person who obeyed the laws of God and who had been sent as a prophetic clarion, Tijerina was certain that the world was in its latter days and that one could already see the dawn. That dawn was the day of the millennium when Jesus Christ would return to earth anew. On that day God would welcome into his kingdom the righteous and the moral. It would be a day of salvation and a day of great rejoicing.

Tijerina’s sermons were simple in form. They were lyrical and melodious with a thunderous cadence and often pure poetry to the ear. Their delivery was equally spellbinding. Eyewitnesses attest that Tijerina was an extraordinary orator who could expound for hours without pause. His classmates at the Latin American Bible Institute selected him as their graduation preacher in 1946 precisely because of this skill. He spoke extemporaneously with ease, moving audiences to enthusiastic laughter and cheers and, in a flash, flipping their emotions to dread and tears.[12] His call to action was hard to ignore. Indeed, his sermons were moving, and his auditors were equally moved.

Tijerina was a radical restorationist who wanted both the Assemblies of God and society to return to a purer and simpler time, to the apostolic time of Christ, to that moment before corruption. Between 1946 and 1950, he tried to lead his followers to holiness, offering them caustic sermons against sexual promiscuity, drinking, dancing, smoking, watching television, and listening to the radio, which were all products the media was selling. He condemned all of this as the wiles of the “sinful and wicked whore of Babylon.” This same whore was also ensnaring the leaders of the Assemblies of God, who had also become materialistic and increasingly bureaucratic and had forsaken their commitment to the poor, to orphans, and to widows.

By 1950 the leadership of the Assemblies of God had heard enough of Tijerina’s searing critiques of their behavior and expelled him from the church, withdrew his license to preach, and ordered him shunned. After his expulsion Tijerina continued to preach throughout the West and Midwest, mostly to Mexican and Mexican American migrant workers. His message was an end-time theology, urging those who would listen to follow the example of Christ and to seek their own holiness. In 1955, with a group of seventeen families, he started a short-lived utopian community in Arizona, near Phoenix, which they called the Valley of Peace. A year later, largely because of an apocalyptic dream he had, he traveled to northern New Mexico, to villages he had visited before in the late 1940s. There he learned how the area’s Hispano residents had lost the communal portions of the land grants given to them by the kings of Spain and the presidents of Mexico. On hearing these stories, Tijerina concluded that they had a holy, just, and sacred cause.[13]

Having spent his adult life pondering and preaching the laws of God, Tijerina now threw himself into the study of the laws of man, having concluded, “I learned that there’s no mercy in churches, no justice in religious people.”[14] At the end of 1957, he and a cadre of about thirty followers settled in Albuquerque and, on February 2, 1963, incorporated the Alianza Federal de Mercedes. He threw himself anew into another restorationist project: the recuperation of the mercedes, the lost land grants. His message was a simple one: the charters of incorporation that Spain’s kings had given the Hispanos to establish towns also bestowed upon them writs of nobility and aristocracy that modernity had eroded. Their honor, their culture, and their lands had been lost and now could be restored if they joined the Alianza. The government had stolen their lands and given them nothing in return except powdered milk, a reference to the commodities distributed as food aid at the time.

Between 1963 and 1966, Tijerina traveled throughout New Mexico and much of the Southwest using the ritual formulas he had mastered as a revival preacher: reading law, bearing witness, healing. He told old women and men about their lost dignity and lost lands and promised to restore them. Where previously he would have begun his revival by reading from the Bible, now he read from the Laws of the Indies and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. Much as congregants would have given personal testimony about their sinfulness at a revival, at Alianza meetings, men and women would explain how their families had lost their lands and describe their lives of utter poverty and unemployment. They would then sing and pray, party and commune, and contribute the $2 monthly membership dues to advance the cause, exactly as they would have at a revival. By the end of 1963, the Alianza was said to have registered five thousand members; by the end of 1964, it had fifty thousand members. By Tijerina’s own count, he had some eighty thousand dues-paying members by 1966, and they were ready for some dramatic action, the type District Attorney Sanchez feared and undoubtedly the type emboldened by the radical nationalism of other American ethnic groups in those years.[15]

It was then, on October 15, 1966, that 350 members of the Alianza took their bold step of occupying a portion of the Kit Carson National Forest. Eight months later, they would attempt their citizen’s arrest of Sanchez.

Tijerina and the activist members of the Alianza spent several years embroiled in litigation. Tijerina and several others faced federal charges stemming from the arrest of the US agents at the Kit Carson National Forest on October 15, 1966. The charges against those arrested for illegal assembly at Coyote on June 2, 1967, were dropped. But the courthouse scuffle of June 5 resulted in 584 collective counts against twenty participants. Charges were dropped against eight for insufficient evidence, with twelve, including Tijerina, being tried by the state of New Mexico. The big break in this case occurred when presiding judge Paul Larrazolo issued his jury instructions: “Anyone, including a state police officer, who intentionally interferes with a lawful attempt to make a citizen’s arrest does so at his own peril, since the arresting citizens are entitled under the law to use whatever force is reasonably necessary to effect said citizen’s arrest and to use whatever force is reasonably necessary to defend themselves in the process of making said citizen’s arrest.”[16] On December 13, 1968, Tijerina and his codefendants won complete acquittal, though the state retried the case against him and eventually won convictions on two lesser charges.

Tijerina took his newly found sanction for citizen’s arrest to Washington, DC, in April 1969. By the authority of the citizens of San Joaquin del Rio de Chama, he tried to arrest Warren Burger, then chief justice of the Supreme Court, for refusing to intervene in their land grant claim. Before a gaggle of television cameras and newspaper reporters, Tijerina theatrically put a lasso around the court building; Burger didn’t even see the commotion and was shuttled out by guards through a side door. Tijerina next tried to arrest Sid Hacker, then the director of the Los Alamos National Laboratory, for building atomic bombs. Hacker was out of the country and Tijerina ultimately left a printed arrest warrant in Hacker’s mailbox.[17]

The event that finally landed Tijerina back in jail occurred on June 8, 1969. Tijerina, his second wife Patsy, and a number of Alianza members entered the Kit Carson National Forest that day, burned the US Forest Service sign marking the park’s entrance, and constructed a makeshift sign announcing that one was entering San Joaquin del Rio de Chama. They were immediately arrested, found guilty of the destruction of federal property, and sentenced on January 5, 1970, to two to five years in the federal prison in Springfield, Missouri.

While Tijerina sat in jail, from June 1969 to December 1973, most of what mushroomed into the Chicano student movement had its genesis. On March 28, 1969, Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzalez hosted the National Chicano Liberation Youth Conference in Denver. Tijerina did not hear about the conference nor did he see a copy of El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, the conference manifesto, until several months later, while awaiting trial for the sign burning. But on hearing that he and the Alianza’s land grant struggle was being announced by Gonzalez as the beginning of the armed revolution to create the Chicano homeland of Aztlán, Tijerina wrote his “Letter from the Santa Fe Jail,” explaining to his followers that the cause of the Alianza had been to recuperate lost lands through litigation, not violent revolution.[18] The Mexican American political activism into which Tijerina tapped in the late 1940s—as did César Chávez in the early 1960s—was rural, class based, and committed to the poor and to farmworkers who worked for a pittance under brutal conditions. They both invested their movements with the language of religion, largely to escape the accusation that they were Communists; they were indeed both devout Christians. They criticized racial discrimination obliquely by focusing on its class iterations.

El Plan Espiritual de Aztlán, in contrast, had committed itself to the formation of a national identity-based movement that addressed the plight of urban youth: police harassment, unequal treatment by the courts, residential segregation, educational neglect, poverty, and vulnerability to the draft.[19] Far removed from the land, young city-based Chicanos and Chicanas depicted their segregated barrios as exploited colonies and articulated a theory of internal colonialism that called for a revolutionary nationalism to overthrow their oppressors. To challenge the racism they experienced daily at the hands of the police, the courts, and schools, they fashioned notions of racial pride rooted in the brown color of their skin at the same time denouncing racism, white skin privilege, and racial supremacy. Drawing on Tijerina’s failed attempts to regain communal lands, students radicalized his vision, proclaiming the need for an independent Chicano nation of Aztlán—something Tijerina deplored because he wanted Indo-Hispano incorporation into the American body politic, not separatism or independence.[20] Eventually, feminist demands for sexual liberation, reproductive rights, and gender equity made their way into the Chicana/Chicano student agenda. These rankled Tijerina to the point of a breach. He wanted no part of sexual liberation or gender equity. His was a gospel of family order, the sanctification of the body, and the holiness that abstinence from the blandishments of “the evil whore of Babylon” guaranteed. He wanted to restore patriarchal authority and familial honor, not destroy it, which quickly put him at odds with Chicana feminists and queer nationalists who accordingly found him too old and too out of touch when he was released from prison in 1973.

Reies López Tijerina’s Pentacostal origins in the Assemblies of God gave the Mexican American civil rights movement a number of ideas that have advanced the cause of social justice. First and foremost, Tijerina preached a social gospel that focused on the poor and dispossessed in the society. He never wavered from this commitment. As an Assemblies of God preacher, he taught his followers to appropriate their individual and direct access to God. Anyone could read the Bible and interpret it for himself or herself without the assistance of trained intermediaries. Tijerina left the Latin American Bible Institute in 1946 with a stack of Bibles written in Spanish that he would give to anyone willing to take one, encouraging them to read the word of God for themselves and hopefully to be as moved by the words justice and love as he had been. When Tijerina took up the cause of the land grants he cultivated the same reading practice among the members of the Alianza, urging them to pore over the Laws of the Indies and the Treaty of Guadalupe Hidalgo. If they were to regain their lands, they had to understand the laws of man and to act, militantly, to ensure the words were honored at least in letter if not in spirit. The laws and the treaty said ejidos could not be alienated; they had been. Now the Aliancistas’ sacred duty was to contest this fact in the courts of law, as they did.

The Assemblies of God inspired the organizational form that the Alliance of Free City States took under Tijerina’s leadership. Since the founding of the Assemblies of God in 1914, they consciously avoided the word “church” in their name precisely to allow individual religious communities the freedom to define themselves and their uniqueness, free of the hierarchy and bureaucratic structures of organized Protestant churches. Tijerina imagined city-states in much the same way. They were free to do as they pleased, without interference from other cities, acting as an alliance when needed but governed by themselves.

Reies López Tijerina died on January 19, 2015, at the age of eighty-eight. The final days of his life were spent in Ciudad Júarez, Mexico, just across the border from El Paso, where his modest Social Security benefits went much further. He lived there with his third wife Esperanza, to whom the US Department of Homeland Security refused (until recently) to issue a green card so they could live together in the states. Reies López Tijerina never got a single acre of land returned to anyone, but he did politicize the history of land tenure in New Mexico, which is still very much alive and contested there to this day.